A Climber We Lost: Bob Williams

Each January we post a farewell tribute to those members of our community lost in the year just past. Some of the people you may have heard of, some not. All are part of our community.

Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

You can read the full tribute to Climbers We Lost in 2024 here.

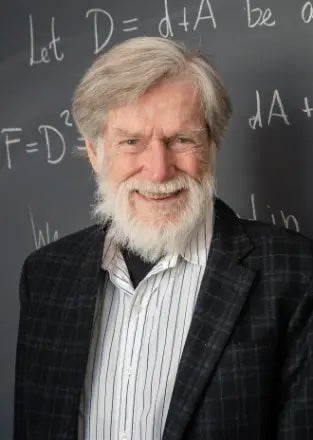

Bob Williams, 96, September 3

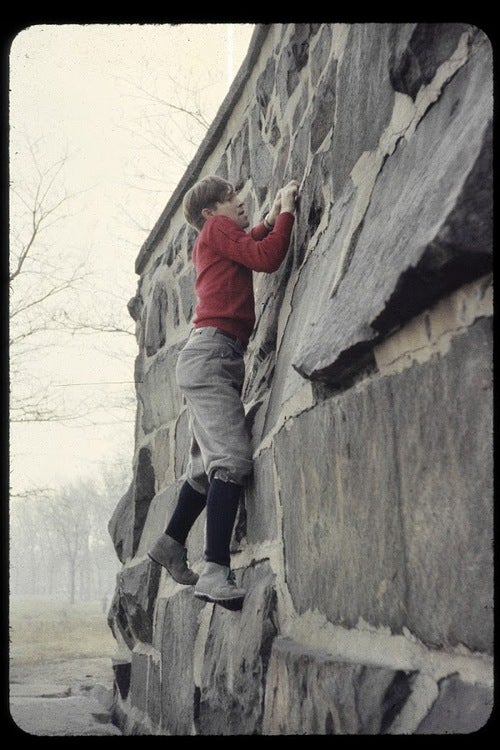

Robert Fones Williams, better known to his friends as Bob, was a celebrated mathematician, skilled dancer, and early American rock climber. Williams was a member of the University of Chicago Mountaineering Club in the 1960s, and a rock pioneer at destinations like Devil’s Lake, Wisconsin, the Tetons, and the Black Hills, with fellow mathematicians Richard Goldstone, Mike Freedman, John Gill, and Georges de Rham, among others.

Born in Bessemer, Alabama, and raised in Austin, Texas, Williams wrote in his autobiography that “The Great Depression, World War II, and rigid Jim Crow defined the young lives of my two brothers and me.” Neither of his parents had attended high school, but Williams and his two brothers managed not only to do that, but to attend university, as well. He graduated from the University of Texas in 1948 with a degree in mathematics, and entered a graduate program at the University of Virginia.

Williams considered a career as a dancer—and was offered a summer fellowship to study dance under Hanya Holm, one of the founders of modern American dance—but chose instead to pursue higher education in mathematics. He was an academic for the remainder of his life. After his time in Virginia, Williams taught first at Florida State University, then the University of Wisconsin, and later Purdue and Northwestern. He was also a member of the Institute for Advanced Study, a theoretical research and intellectual inquiry center at Princeton. Much of Williams’s research was on dynamical systems theory. “He liked to say he studied chaos,” reads his obituary.

Williams was married twice, most recently—and until his death—to esteemed mathematician Karen Uhlenbeck. Uhlenbeck, among other accolades, is one of the founders of the field of geometric analysis, and is the only woman to have ever won the prestigious Abel Prize (2019).

While in a post-doctorate program at the University of Chicago in the early 1960s, Williams met Goldstone, then a student, who introduced him to the sport of rock climbing. “For the next four decades I was an avid climber,” Williams wrote. “Later, [on] trips in the United States and to roughly ten countries for mathematics meetings, I easily found climbers, mountains, rock and snow for my main sport.”

Goldstone remembered his late friend as low-key and hard to rattle. “Bob got very good, very fast,” he recalled. Goldstone said that, compared to some of their other friends, like Gill, Williams was “never going to be an ‘elite’ level climber,” simply because didn’t have the patience or desire to train at that level. His background as a dancer, Goldstone said, seemed to give him an extremely strong legs and core, but mathematics was always the area where he wanted to “push” the limits. Climbing was just a great pastime. “We were training our heads off, but Bob never did that,” Goldstone said. “He was just naturally strong.”

Goldstone fondly recalled when he, Williams, and Pat Ament climbed a 1,000-foot route in Colorado’s Royal Gorge. “It was all primitive, before jumars, so we were just prusiking with knots,” Goldstone said. “We didn’t really know the techniques, or maybe they hadn’t even been invented yet.”

Williams was prusiking with an extremely heavy haul bag hanging from his swami belt. The bag weighed so much that, while he was jugging, the weight of it broke several of his ribs. Williams was unperturbed. “Bob never mentioned those broken ribs until many days afterwards,” Goldstone recalled, chuckling. “He never said a word. He just kept on climbing, leading his pitches, then following with that too-heavy haul bag.”

Writing on Mountain Project, Gill recalled a similar instance when he and Williams were free soloing on the Thumb and Needle in Estes Park. “Above an overhang, the hammer in [Williams’] back pocket clipped the rock,” wrote Gill. Knocked off balance, Williams teetered on the edge of a serious fall. The sight “sent a chill up my spine,” Gill noted, “but Bob didn’t seem to give it a second thought. A quiet spoken gentleman.”

Goldstone said that describing his friend as a “classic tough guy” would be giving the wrong impression, noting that Williams was fun-loving and energetic. But he was imminently cool under pressure, and never one to gripe or complain. “He certainly knew how to suck it up,” Goldstone said.

Williams appeared equally modest about his professional life. His expertise as a mathematician is hard to illustrate in layman’s terms (interested parties should read his autobiography, linked above), simply because his fields of study were so complex. But for the last sixty some years, Bob Williams taught at some of the most prestigious universities in the United States, lectured around the world, and took part in groundbreaking mathematical research.

“You always got the impression from Bob that he was just sort of bumbling along in life,” Goldstone said, chuckling. “He might mention that he went here, he went there. Meanwhile, he had this extremely significant, influential mathematical career. But that was Bob. He never made a big deal of anything, certainly not himself.”

Bob Williams is survived by his wife, Karen, daughter, Ellen, and several nieces and nephews.

You can read the full tribute to Climbers We Lost in 2024 here.