Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

El Capitan serves as a runway: a place for climbers to express themselves and show off their personalities. Out of all the existing routes, perhaps no stage is more obvious than the “Greatest Route on Earth,” the Salathé Wall (VI 5.13c). The route’s storied history shows how personal style has continuously evolved in Yosemite since the very beginning—from the just get ‘er done attitude of the ‘60s to our modern day free climbing values. It has also inspired me to strive to climb in the best style I can.

In 1961, Royal Robbins, Chuck Pratt, and Tom Frost made the first ascent of the Salathé Wall at 5.9 A2, the second route on El Capitan after Warren Harding and the Nose (VI 5.9 A2) in 1958. They climbed the first 900 feet over three days before heading down to resupply. Four days later, they jumared their fixed ropes and continued up the rest of the wall. Despite their primitive gear and outfits—including homemade hardware, lug-soled mountain boots, cotton t-shirts, and military surplus pants—they finished the route six and a half days later.

The following year, Robbins returned with Frost and made the second ascent, repeating their own route and completing the first continuous ascent (never returning to the ground) of El Capitan in the process. For them, climbing was equal parts exploration and expression. They wanted to push themselves farther while also improving their own style. Consequently, most valid ascents of El Cap moving forward would require that parties never returned to the ground midway through a climb.

In 1979, Mark Hudon and Max Jones made a “free as can be” ascent of the Salathé Wall. Wearing bright yellow turtlenecks, tight sweatpants, big down jackets, and hightop EB shoes, they free-climbed as many aid pitches as they could, climbing difficult 5.11 and 5.12 cracks high above the valley floor. “We were going up there just to have a bunch of fun and see what we could do,” Hudon says of their ascent, where they managed to free all but 300 feet of the 3,000-foot route.

Hudon and Jones pushed the envelope of big wall free climbing during that ascent, laying the groundwork for Todd Skinner and Paul Piana, who made the first team free ascent of the Salathé in 1988, with each climber tackling a crux pitch that the second then jumared. They climbed two variation pitches from the original aid line (which still haven’t been freed), one dubbed the Teflon Corner (5.12d) and another above the famously exposed Headwall, a bolted 5.11+ face off of Long Ledge. Skinner in particular put on the performance of his life, freeing the route’s technical crux, a devious corner on Pitch 19, which he climbed with an intermediate belay and rated 5.13b at the time.

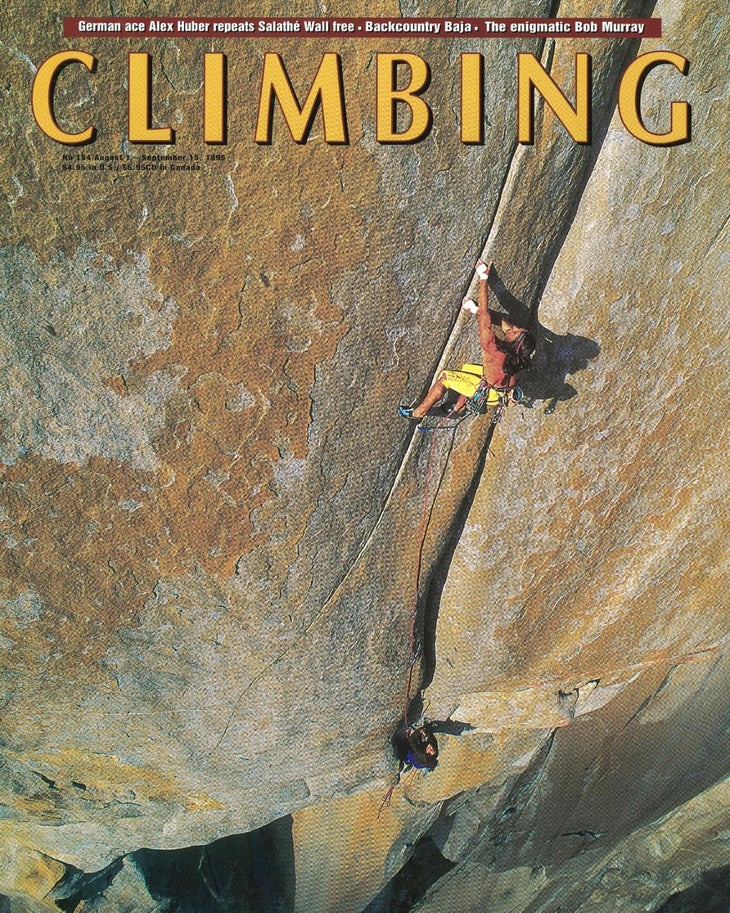

Skinner and Piana are often credited with the first free ascent of El Capitan—but not always. “Neither Skinner nor Piana can say he has freed all the pitches, so neither can say he has freed the Salathé,” said Alex Huber in the 1996 American Alpine Journal where he claimed the first ascent of the route as an individual. Huber did in fact free all of the pitches during his ascent, and he even improved upon some of them—like when he climbed the Headwall in two pitches (eliminating a hanging belay), unlike the previous ascent’s three. But Huber didn’t exactly climb in perfect style, either. A storm blew in midway through his ascent and he bailed back to the valley floor to wait it out. A few days later, well rested, he jumared fixed ropes back to his highpoint and kept free climbing. Higher up, Huber skipped the crux 5.13b corner via the 5.11a Monster Offwidth, and also pioneered the Boulder Problem (5.13a) to avoid the seasonally wet Teflon Corner. For Huber, leaving the wall and returning—and skipping a crux pitch for one with a 10-letter-grade difference—mattered less than avoiding hanging belays and sharing leads. “I only accept a redpoint if all the pitches are connected with belays at no-hands rests,” said Huber. Climbing the Headwall shirtless, his long hair held down with a thin headband, yellow lycra and blue rock shoes pushing him ever onward, it was clear that Huber, too, had an eye for style.

In 2003, Jim Herson made the second ascent of the original Salathé, climbing Pitch 19 (eliminating the hanging belay used by Skinner and upgrading it to 5.13c), the Teflon, and the Headwall, which he split into three pitches. Ninety hours after he completed his ascent, his son Connor was born. In June 2022, the younger Herson completed the third ascent, redpointing the Headwall in two pitches. He also climbed Pitch 19 noting, “It’s not the Salathé if you don’t climb Pitch 19… I would have been disowned if I hadn’t.”

Alex Honnold attempted to free the Salathé in a day in 2023, via Pitch 19 and the Teflon, but the relentless flared hand-jamming on the Headwall eventually destroyed him and he topped out without a send. “It feels a little contrived,” Honnold said of following the original aid line, noting that the Monster Offwidth and Pitch 19 start and end in roughly the same vicinity. Jim Herson, on the other hand, says “Alex brings up an interesting point to be considered if he ever manages to finally free the original Salathé.” Regardless, that debate did little to influence me.

“I can’t wait to see you free the Salathé,” Mark Hudon told me years ago, “but when you do, you gotta climb Pitch 19!” I’ve dreamed of freeing the route for as long as I’ve climbed in Yosemite. The long and slabby “Freeblast” pitches appealed to my technical footwork, the wide, blue-collar features high up the wall, such as the Hollow Flake, the Ear, and the Sewer, called to my work ethic, and although the steep Headwall intimidated me, it had also fueled my dreams from the very beginning. It was Pitch 19 that truly frightened me. After all, only Todd Skinner, Jim Herson, and Connor Herson had freed it during their ascents. Every other “free ascent” of the Salathé had taken a far easier way out. “That’s the route,” Hudon said of Pitch 19. When he and Jones had been working their “free as can be” ascent, they didn’t look for variations to the existing line. They followed the original line of the first ascent from bottom to top.

After I’d spent a month working the route, Hudon drove to the Valley to support me in my pursuit. Wearing my favorite white cotton t-shirt, stretchy canvas pants, and warm down jackets at the belays, I finally felt ready to take on the Salathe. I skipped the hanging belays on the Freeblast, sent Pitch 19 (my first of the grade on El Cap), stemmed through the Teflon Corner, and linked both Enduro Corners and the Roof in one amazing 60-meter pitch. Although I failed to do the Headwall in similar “ledge-to-ledge” style, pioneered by Japanese superstar Yuji Hiryama in 2002, I followed the tradition of climbing in Yosemite, sticking to the original free line, avoiding hanging belays, and striving for the best ascent I possibly could, leading every pitch over six days with only two falls on the Headwall.

Watch the author pull the “Roof” after firing the Enduro Corners. The video quality is bad–but the effort is too good not too share! Video: Nik Berry

“It was really touching,” Hudon said of belaying me on the Headwall. For him, it was a moment that recalled his ascent with Max 48 years ago. It was a dream come true to climb this route with Hudon and to have some of the best climbing days of my life on the side of El Capitan.

Wool, lycra, and technical fleeces have faded from most climbers’ wardrobes these days. Some things in climbing, however, like classic routes or pushing personal limits, never go out of style. They’re timeless and evoke a permanent sense of fashion that embodies what I look for in climbing and my life. The Salathé gave that to me and reminded me of why I love climbing in Yosemite—to feel part of something bigger, and to continuously improve my own personal style.