Two Winter Workouts to Boost Your Endurance by Spring

If your forearms inflate like balloons and your fingers always seem to uncurl just before the anchors, then these winter endurance workouts are just what you need.

The gym season is here. Time to ask: Am I getting the best returns from my training? Now can be a crucial time to gain. In particular, you can boost the productivity of power-endurance and low-intensity workouts by applying some basic principles of training structure. In this article, I discuss how to train endurance and power endurance over the winter.

Part 1 tackles interval training, helping you calibrate difficulty, work time, and rest times, with an eye toward building power endurance. Power endurance is the type of fitness required for most sport routes, with typically sustained sequences of 20 to 60 hand-moves. Although most climbers use the term power endurance, coaches may also say “anaerobic endurance” or “high-intensity endurance.” The trademark of power-endurance terrain is that there are no real rests—stopping and shaking will only result in more fatigue. Hence the best approach is just to keep moving.

Part 2 discusses low-intensity endurance training for longer routes, a crucial yet easily ignored area of training that provides the key to recovering on the fly. Low-intensity endurance training involves sticking it out for 60 10 150 move sequences, which may take between six and 15 minutes to execute.

Part 1: Interval Training for Power-Endurance

With power-endurance training, it’s easy to fall into old habits: to climb routes at the gym, guided by whim, on whichever lines are free. But the biggest mistake is to try to break into that elusive new grade every session. This causes you to take either long rests between climbs (and, as a result, fail to climb a worthwhile amount) or, conversely, burn out during the first half of the session and be forced to lower the grade so much that the second half of the session is not productive.

How can we ensure that we climb the right number of routes, at the right grade to maximize the benefits of our sessions? The answer is to adopt the same approach used to train for endurance sports such as rowing, running and cycling—interval training. This involves striking a balance between the intensity (or difficulty) of the climbing and the volume (or number of routes/moves). The equation is simple—the higher the intensity, the less volume can be achieved. With interval training the idea is to achieve an optimum balance, keeping both volume and intensity reasonably high.

Setting the Training Grade

Another key principle of interval training is that the intensity of each interval remains constant. Pick a fixed grade (typically one or two grades below your maximum onsight capability) and stick to this for the duration of the session until you fail. For example, someone whose best current onsight grade is 5.12c would (after warming up) maintain the grade of 5.12a throughout the session. The idea is that the first two or three intervals feel comfortable, the next few are tough, and the last are desperate.

Number of Repeats

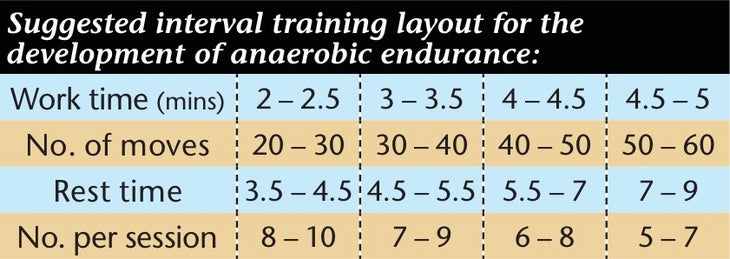

Repetitions will depend on how many moves you are completing during each work interval. For shorter work intervals (e.g. 20 to 30 moves), aim for a larger number of repeats (e.g. 8 to 10), and for longer work intervals (e.g. 50 to 60 moves), shoot for a lower number (5 to 7). See the table for guidelines.

Rest Times

Your rest between each work interval has a direct effect on the amount of repetitions possible. If you take 30-minute rests between each climb, then you would probably be able to roll out routes at your training grade all day, but if the rest drops to two minutes, then you would be on the ropes after two or three climbs. The answer is to strike a balance. Rest times should be approximately “time-and-a-half” of the work interval, so the higher the number of moves, the longer the corresponding rest. Again, see the table.

The Technique Element

Climbing differs from most endurance sports in the sense that the technique component is highly varied. You will achieve better results from switching between different routes, rather than lapping the same route. Training on circuits is also beneficial. Last, it is also vital to train on different types of holds and different wall angles, selected to prioritize your goals or weaknesses. In other words, if your project is a 40-move, gently overhanging sport route on small crimps, then this is what you must simulate in your training.

Training Tips

A common oversight is to train the same number of moves (usually the length of the routes at your gym) every session. Make sure you train at different intensities within the given spectrum for power endurance (20 to 60 moves). For longer work intervals, lower off and do double or triple laps. Make sure you pull the rope down and start climbing again as quickly as possible, without any rest. Circuits on the bouldering wall provide a great option if you don’t have a belay partner.

Goal-Setting

The key to success in any type of training is to have goals for every session, and interval training lends itself perfectly to this notion. Aim to reduce the rest times very slightly every time you train. The table gives upper and lower values for rest times, so start training at the higher value and reduce the rest by 15 to 30 seconds every session. If you are training on circuits, then an alternative to reducing the rest times is to add five moves each time, or to make a few of the moves slightly harder. With this approach, if you train power endurance two or three times a week, it only takes a month or two before you notice impressive results.

Part II: Low-intensity Endurance

Climbers sometimes use the term “stamina” to refer to low-intensity endurance. In other sports it is common to hear endurance classified as aerobic or anaerobic but in climbing this is confusing. For example, a given climb may have a short, intense, sustained section, requiring anaerobic endurance, followed by a longer, easier section that calls for aerobic endurance. It is common for both aerobic and anaerobic energy systems to be tested on the same climb, as lactic-acid levels rise and fall, and it’s difficult to separate them completely when it comes to training low-intensity endurance. To train this, we’ll do sequences between 60 10 150 hand moves, which may take between six and 15 minutes to execute.

A common mistake is to ignore low-intensity endurance training altogether. Few gyms have routes that even come close to the required height, so we take the easy option and simply order what’s on the menu. The usual approach of doing hard single routes (for high-intensity endurance) requires less discipline and less pain tolerance, as you won’t be spending as much time under the influence of fatigue. It is a classic error to try to climb the hardest possible grades every time you train. A commitment to training low-intensity endurance will require that you resist this temptation. Yet even for those who can do double or triple laps on easier routes, or occasionally climb down and then back up again, there is still plenty of room for applying a little more structure.

The New Routine

Low-intensity endurance-training sessions can be done on a lead wall or an easy section of a bouldering wall.

Lead wall

The lead-wall option is good provided you have a like-minded partner and you don’t hog popular lines when the gym is busy. Either lead up, lower back down, pull the rope as quickly as possible, and lead again; or lead up, climb down, and then climb back up again. At first, down climbs will need to be considerably easier than up climbs, but with practice you can narrow the difference.

Bouldering wall

The bouldering wall is great for climbing alone. It usually works best to make up sequences at random, or to link easier color-coded boulder problems

or circuits.

When to train

Elites may wish to train endurance up to five times a week, with perhaps one power session in addition. Intermediates may do three or four endurance sessions (plus one power session) and beginners should do two or three endurance sessions (plus an easy boulder session). It is universally accepted that low-intensity endurance provides the best and safest type of training to start a training program. You can then move on to prioritize high-intensity endurance training. Another tactic is to do a phase of concentrated low-intensity endurance immediately prior to an onsighting or trad trip.

Vary the workouts

Don’t always train the same number of moves at the same angle. Alternate between some of the variables given below.

Number of moves

Mid-intensity endurance: e.g.: 60–80 moves

Low-intensity endurance: e.g.: 80–150 moves

Wall angle

Practice “jug endurance” on steeper walls and “fingery endurance” on lower-angle walls.

Sustained or fluctuating

A sequence of climbing requiring low-intensity endurance may either be sustained, with the moves all at a similar level, or fluctuating, with harder sections interspersed with good rests. The former style requires a steady pace, perhaps taking the occasional quick flick of the forearm to attempt to recover, whereas the latter is about sprinting the hard sections and milking the rests. Both styles are important to practice.

Training Structure

Setting the training grade

Below is a guideline for an intermediate-level climber.

- Triple set: 2 or 3 grades under onsight limit for a single route.

- Quadruple set: 3 or 4 grades under onsight max.

- Up>down>up: 1st up-climb (2 or 3 grades less than onsight max). Down-climb (4 or 5 grades less than onsight max). 2nd up-climb (2 or 3 grades less than onsight max).

Remember that the cumulative grade of three or four easy-ish routes racked up back-to-back should actually be pretty close to your limit grade. For example,

four laps of a short gym-length 5.11a, back-to-back, is actually equivalent in effort to a long 5.11d or 5.12a on rock.

How many sets should you do?

Aim to complete between four and six work intervals for low-intensity endurance. To some extent this number will depend on how hard you pitch the training grade, but if you do substantially less or more, then clearly the routes or circuits are either too hard or too easy. Always complete the work, but by the seat of your pants. The first one or two overall sets should feel fairly comfortable, the next two should be tough, and the last two—a desperate fight.

It is also worth noting that low-intensity sessions can work very well for active rest, or injury rehab, provided you drop the grade considerably lower and do one or two less sets overall.

Rest times

Time-and-a-half is a good guideline. For example, if you’ve been climbing for 10 minutes, rest for 15.

Structure Variation into your training

Try the following combinations to add variety to your training. No single structure is superior to the other, so try one that is new to you.

Interval structure

This is similar to the structure given in No. 192 for high-intensity endurance, where intensity, length of climbing and rest times all remain fixed and constant. E.g.: 10 mins on (or 100 moves) x 5 with 15 mins rest between sets.

Intensity pyramid structure

Length of climbing and rest times remain fixed, but the grade / intensity pyramids up and then back down again: E.g.: 100 moves with 15 mins rest between sets at 80% > 90% > 100% > 90% > 80% of max onsight grade.

Duration pyramid structure

With this option, the intensity / grade remains the same for each set, but the duration of climbing varies in a pyramid structure. E.g.: Fixed grade of 90% of onsight max for all sets: 7 mins on, 10 mins off, 10 mins on, 15 mins off, 15 mins on, 20 mins off, 10-on-15-off, 7-on.

About the Author

Neil Gresham has used his own endurance training to find his way up 5.14+ sport and trad lines. He specializes in coaching intermediate climbers. To learn more about his offerings, see his website.