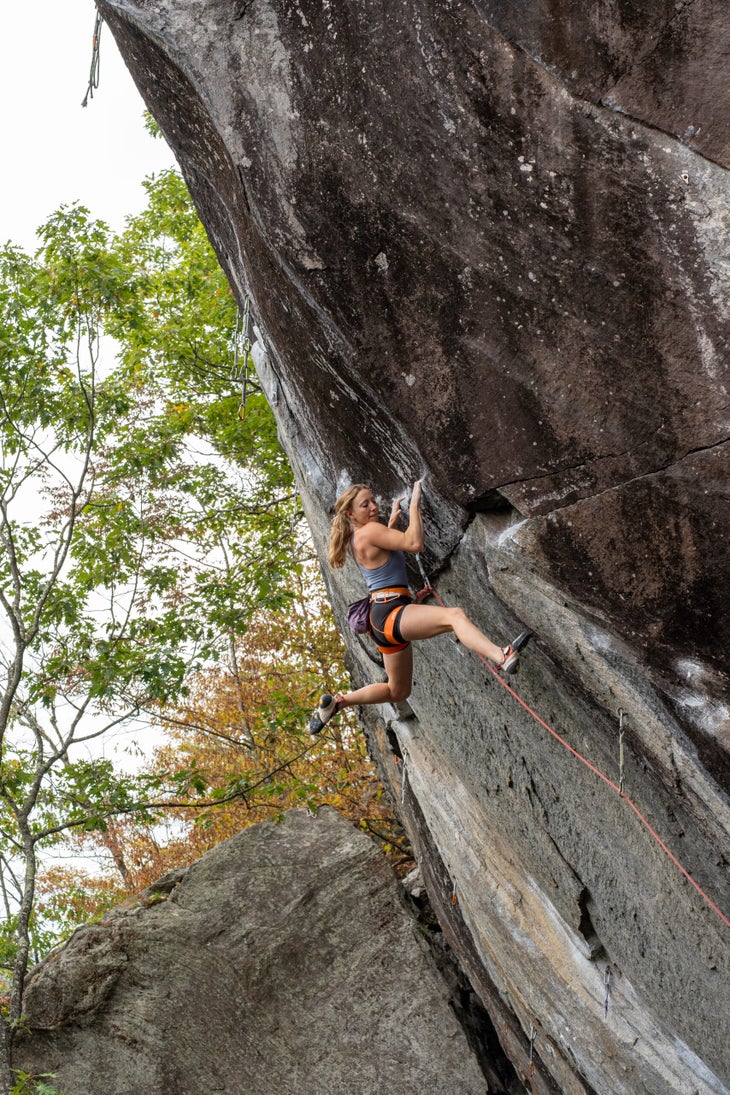

At 5.14d, her new route, ‘Mad Lib,’ is the hardest grade established by a woman in North America since Beth Rodden’s ‘Meltdown.’

The post Michaela Kiersch Just Made History With This First Ascent appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

In between flower-filled strolls and lakeside reading sessions, Michaela Kiersch pulled off the hardest ever first ascent of a sport route by a woman in North America. On September 11, Kiersch freed an open project at Vermont’s Lone Rock Point, dubbing it Mad Lib (5.14d/9a).

“There are existing 5.14s at the wall, and this line is an obvious link through the hardest sections of the cliff,” Kiersch told Climbing.

Mad Lib represents the hardest FA on the continent by a female climber since Beth Rodden’s 2008 takedown of Meltdown (5.14c) in Yosemite. While Kiersch’s FA bests Rodden’s in terms of the grade itself, Meltdown could be considered harder than Mad Lib because it’s a trad climb. Beyond North America, the hardest first ascent ever by a woman remains Sweet Neuf (5.15a/9a+) in Pierrot, France, established by Belgian climber Anak Verhoeven in 2017.

As usual, Kiersch pulled off this historic achievement with casual aplomb. The first woman in the world to climb both 5.15 and V15 also happens to be remarkably relatable. Impressively, this pro climber lives a double life as an occupational therapist. She loves solo travel (case in point: her trip to Switzerland, where she sent Dreamtime, V15). And between cutting-edge ascents, she shares no-filter selfies, carousels mocking Internet trolls, and cinematic homages to her favorite beverage. (No, not AG1 Greens shakes or athletic performance drinks. Just good ol’ Dale’s Pale Ales, one of her sponsors).

We caught up with this Salt Lake City-based climber to find out how she pulled off her latest feat, what else she got into in New England, and where she’s headed next.

Inside Michaela Kiersch’s 5.14d first ascent

“It’s incredible to feel like I can contribute back to the climbing community in this way and start to carve my own path with regard to hard first ascents,” Kiersch says.

Her newest contribution, Mad Lib, marks Kiersch’s second first ascent. She bagged her first first ascent in Kentucky’s Red River Gorge with Goldilocks, which she called 5.14b, but Alex Megos later upgraded to 5.14c. Mad Lib begins on a previously unsent, five-bolt start equipped by Jesse Franklin—local legend Pete Clark bolted the rest of the line. The route then merges with an existing route known as King Tubby (5.14a), at the top of which Kiersch says a “taxing kneebar rest” awaits. After the rest, powerful and dynamic moves lead up “an extremely beautiful arête,” coinciding with the top of Terror Wolf (5.13c).

The fact that Mad Lib includes sections of several other routes inspired its name. “When talking with local Peter Kamitses, the suggested name for this route grew so long and nonsensical that it sounded like a Mad Lib word game,” Kiersch explains. “It was a bonus that this coincided with the hip hop theme on some of the other routes.” Nearby route names like Bring Da Ruckus, Tiger Style, and Ghostface Drilla pay homage to Wu-Tang Clan. In addition to hinting at the word salad of a conglomerate route, Mad Lib alludes to a producer who’s collaborated with rapper MF Doom.

See where Kiersch’s route Mad Lib is located

Mad Lib rises 80 feet tall, but Kiersch says it “climbs much longer” due to its steepness. She spent six days working the route. On day five, she finally linked up the start. All in all, she estimates that she put down between 20 and 30 burns before redpointing it around 9 a.m. on September 11.

The hardest section for Kiersch consisted of “a hard deadpoint to a pinch, followed by a barn door and karate kick.” Alternate beta included turning the pinch into a full crimp, then launching a deadpoint to a sloper. “The movement is stellar and unique!” Kiersch says of the crux moves.

Mad Lib is located on a limestone cliff known as Lone Rock Point hanging over Lake Champlain. “It’s pretty special to find limestone sport routes on the East Coast, and the setting is just surreal,” Kiersch says of why she decided to check out this crag. Her September trip was only her second time in Vermont; when she visited for the first time last February, she “fell completely in love with the climbing community and area.”

Plus, a 5.14c FFA for good measure

“Hardest bolted first ascent in North America by a woman” isn’t the only record Kiersch walked away with from her New England trip. Just two days after she sent Mad Lib, she nabbed the first female ascent of Livin’ Astroglide (5.14c) at Waimea wall in Rumney, New Hampshire.

Livin’ Astroglide follows a black arête, leading to a shared crux with Jaws II and China Beach up top. “With crimps, heel hooks, and pure resistance and recovery climbing, it suited me extremely well,” Kiersch says of the route.

Rumney is actually what first sparked Kiersch’s desire to plan a New England climbing trip. “I’ve always been inspired by the Dosage [a Reel Rock film series] in Rumney,” she says. Then a good friend—and Vermont local—clued her into Lone Rock Point and the open projects there. “After seeing one photo, I was completely sold,” she says.

During her two weeks on the East Coast, Kiersch also spent some time working on Jaws II. This 5.15a route has yet to see a female ascent. She didn’t manage to send, but she noted that she set herself “up well for a return trip.”

But for now, Kiersch’s travels will take her to Europe, where she’ll spend most of the fall pursuing “something hard.” What exactly? “I am keeping my plans loose to allow for weather and psych to guide me,” she says.

The post Michaela Kiersch Just Made History With This First Ascent appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Lindič's advice is invaluable to anyone climbing high off the deck.

The post Alpine Badass Luka Lindič’s Advice for Climbing New Lines in the Mountains appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Luka Lindič is, in my opinion, one of the most impressive alpine climbers around. He’s a quietly confident generalist, excelling on boldly traditional rock, steep ice, and committing mixed terrain. The 36-year-old has made numerous notable first ascents, including Heart of Stone (M7 90° snow; 1,050m) on Alaska’s Mt. Huntington; the Leclerc-Lindič (M7+ WI6+ R; 1,100m) on Mt. Tuzo, Canadian Rockies; Pot (5.11 A3; 800m) on Aguja Poincenot, Patagonia; and the 1,350-meter North Face (ED 90°) of Hagshu, a 6,515-meter mountain in the Kishtwar Himalaya, which earned him a Piolet d’Or.

At the Arc’teryx Climbing Academy in Squamish last month, Lindič gave a presentation about establishing first ascents in the mountains. For a mere $10! I immediately signed up. The 20-odd people in attendance spanned generations of climbers and ability levels; there were at least two other Piolets-recipients in attendance, several hardcore alpinists, and many more wide-eyed young guns eager to learn. Lindič spoke for an hour—riddling his presentation with dead-pan Slovenian humor—and I quickly realized that his advice was practical for any alpinist or backcountry rock climber, not just those questing into unclimbed terrain. So I have attempted (with permission) to summarize some key points below.

The must-haves

Each new line Lindič climbs must have one of two characteristics: (1) It must be visually aesthetic, or (2) it must be physically difficult. Sometimes, as with Lindič’s 2022 route Invisible Transformation, which paired some of the hardest pitches in the Julian Alps with a logical path up an iconic face, you get lucky and climb a new route with both of these stipulations.

But even the most beautiful route in the world isn’t worth doing if it’s too exposed to deadly hazards. Everyone has their own risk tolerance, but be sure to identify your acceptable level of risk beforehand, and then stick to it shamelessly. When we’re climbing in busy areas, like the Alps, or Patagonia, it can be easy to fall into a herd mentality when we see others accepting greater risk.

Reconnaissance trips are a good use of your time

If your intended objective is close to home, spend a weekend sussing it out for the following weekend’s attempt. If it’s far from home, say Patagonia or the Himalaya, spend an entire trip climbing something easier in the vicinity of your long-term objective. This allows you to view the route and glean important beta about things like the rock type, climbable features, possible cruxes, and descent options. For Lindič, standing on the summit of Aguja Saint-Exupéry gave an invaluable perspective of the South Face of Poincenot, and the eventual line of Pot. Make sure to take detailed photos to reference later! Then return to the same zone on a subsequent trip to climb your original objective.

Take lots of photos

When new routing or climbing established routes with little beta, panoramic photos or videos of the mountain are helpful to have while on the wall. It can be difficult to ascertain exactly where you are on a big, clean panel of stone, since steep rock faces do not provide clear lines of sight. Photos taken from the base of the mountain, or from across the valley, can provide a big-picture perspective about which prominent features you need to aim for.

Generally speaking, the more blank and technical the face is, the more route photos are important. Sometimes, it is best to actually climb a hard or devious pitches to link easier crack systems together, rather than continuing up medium-difficult terrain that will eventually dead end. Detailed photos help remind you where to branch out.

Get creative

While on the first ascent of Pot on Aguja Poincenot’s impressive South Face, Lindič was faced with a blank section of vertical granite. Rather than drilling another bolt, he made a lasso and threw it around a horn high above, then jugged the line.

View this post on Instagram

Complex mountains often require redpoint tactics

Think about the mountain as a series of moves on a project. The approach is one move to learn en route to a successful redpoint ascent; the glacier beneath the wall is another move; the first five or 10 pitches is another. Sometimes you need an entire season to learn just one move. Eventually you’ll clip the chains.

Learn the descent

If your intended line of descent is long and requires a lot of rappels or down climbing, climb up your descent line during a shorter weather window so you can familiarize yourself with the terrain. While waiting for a four-day window to finish Pot, Lindič used a brief, one-day window to climb his intended line of descent, the Whillans-Cochrane (5.9 70° snow; 550m). When he finally topped out Pot later that season, the summit of Poincenot was in a whiteout. He was grateful to not be onsighting his descent blindly.

If you do have to onsight the descent, and there are no established anchors, prioritize slung horns and blocks to conserve your rack. Solid ice is even better, since rappelling from V-threads requires no hardware or cordelette. Lindič will bring extra nuts to bail from when climbing a big granite route, and extra pitons if climbing limestone. If you are uncertain about the quality of your anchor, build a secondary anchor in an adjacent crack and loosely clip a sling from it to your primary anchor as a back-up for the first person while they rappel. Make sure the last person to rappel cleans the back-up anchor.

Have a realistic success rate

Climbers want to feel the success of a big climb after every trip. That’s not often the case. Lindič’s personal alpine success rate is about 50%.

Think about your ropes

For a serious granite rock climb, Luka likes to bring a thicker—~9.5mm—rope as his main climbing line and hauls using a dynamic half rope. He likes the redundancy of having a second dynamic rope available should his main line get core shot. In “classic” alpine terrain, where he does not expect to haul, he uses two half ropes to reduce rope drag. On extra complicated climbs, that involve both adventurous free climbing and hauling, he will climb on half ropes and bring 30 meters of 6mm cord to both haul and utilize as bail cord when rappelling. (Check out this article, about his new route Heart of Stone on Alaska’s Mt. Huntington, for photos of this rope system.)

First ascents are not solely the domain of elite climbers

There are many mountains in the world, each of which has routes of various difficulties. It doesn’t matter if you climb 5.9 or 5.13—just be solid at the grade and considered in your decision making. Recognize when an objective is—or becomes—too difficult for you to climb it safely.

The post Alpine Badass Luka Lindič’s Advice for Climbing New Lines in the Mountains appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

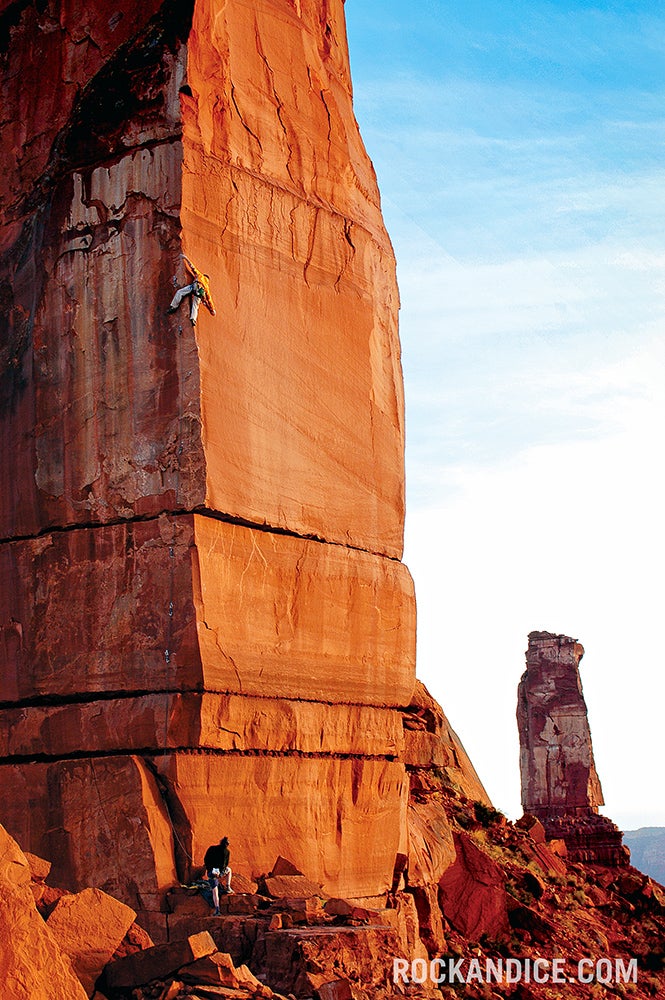

The secret history and modern rebirth of Western Colorado’s sleepy Unaweep Canyon.

The post The Splitter Cracks and Mind-Boggling Movement in Unaweep Canyon appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

This article was originally published in Climbing No. 369 under the title “A Canyon With Two Mouths.”

Heat, cactus, loose rock, dehydration

August 2011: Jesse Zacher and I sweated profusely as we battled through fabric-tearing, soul-sucking, eight-foot-tall thorn bushes next to West Creek in Unaweep Canyon, in the high desert of western Colorado. My first son, Rowan, had just been born, and I hadn’t climbed in weeks. Our goal was to establish a climb on the obscure Unaweep Wall on the canyon’s west end, just outside the town of Gateway. Jesse, a diehard Unaweep local who’d introduced me to the granite canyon’s raw beauty and secrets—and who is the current president of the Western Colorado Climbers’ Coalition (WCCC)—had said the approach would be “mellow.”

After the slippery initial river crossing, a cattle path took us up a steep, loose drainage through the aforementioned berry patch. As the late-afternoon heat pounded us, our heavy packs slowed our pace to a crawl. We’d brought food and water for two days, our climbing equipment, bolts and drill kit, a tent, and sleeping bags. Both experienced at new-routing in the canyon—familiar with its cracks that randomly end, grainy flares, Black Canyon–like pegmatite bands, and tiny, often-flaky crimpers—we’d figured that sneaking in a new line on the 1,000-foot, hyper-featured Unaweep Wall would be quick and painless.

We camped at the base of the wall’s left flank amidst cactus and talus. The sole climb here, according to the 1997 guidebook Grand Junction Rock, was Ancient Wisdom, a gnarly KC Baum and Kevin Rusk A3+ hundreds of feet east. Unaweep Wall is one of the least—if ever—visited walls in the canyon, which comprises some 30 granite crags spread along the highlands between Whitewater and Gateway. We hoped to establish a moderate free climb here to recon harder potential. As the sunset turned the sky pink and orange and the air began to cool, we bedded down. Then: Crash! Smash! “What’s that noise?” Jesse screamed. I flailed out of the tent and ran from the wall. The ancient granite was shedding its skin, and our tent—well, Jesse’s girlfriend’s tent—was now sporting holes through the rainfly. Though no more rocks fell, we slept poorly the rest of the night, our tent stuck on its exposed perch.

When first light broke over Grand Mesa, we began up a sunny, moderate-looking corner system above camp. I led through thorny bushes and entered a water-polished corner. The climbing was no harder than 5.9, but lacked pro. I couldn’t even fish micronuts into the tightly sealed corner, and each balance move up to a higher stance became more and more committing. Sun burning the rock and sweat stinging my eyes, I inched closer toward overheating with each desperate move.

At about 100 feet, I built an anchor and brought Jesse up. He took the lead, and in his easygoing fashion navigated the corner with style, firmly pressing down on miniscule smears to connect the imperceptible dots. His lead ended with a courageous traverse right into a second low-angle dihedral below a heart-shaped prow. The logical line snaked right of this feature, and we continued upward on ever-steepening ground.

On pitch five, my initial foray up the second corner came to a dead end, and I downclimbed back to Jesse; the heat, dehydration (we had only one liter of water and a Clif bar), hauling, and our slow progress crushed us. I made a foray into another “moderate” corner, gunning for the top of the wall. Two hours later, after digging dirt from the crack with a nut tool, chopping small shrubs from the ledges, and scraping away loose rock, I reached a belay. I’d also drilled two bolts to protect a bouldery crux at 60 feet. After working the pitch on toprope and after a couple of attempts, we both freed it. By then we were out of water, temps were in the 90s, and we were cooking like bacon. A few hours later, after a final pitch of nondescript slabs, corners, and ledges, we topped out in twilight, completing That’s All I’m Asking For (5.11; 1,000 feet).

Back at camp after a few double-rope rappels, Jesse and I talked through the day’s challenges. We agreed it would be awhile before we came back to Unaweep Wall. Unaweep can be a punishing mistress—and that’s on the “traveled” walls. On a rarely, if ever, climbed cliff like Unaweep Wall, the choss factor is even higher. But so is the adventure.

The Canyon with Two Mouths

The Utes of southwest Colorado named Unaweep the “canyon with two mouths,” referencing its rise to a middle high point then drop to dueling canyon mouths to the north and south. Ironically, despite these two mouths, the early Unaweep climbers rarely spoke about its steep granite, green pastures, and wild side canyons. Even today, despite a proliferation of Mountain Project beta and an upcoming guidebook by Jesse and Michael Schneiter, it remains a backwater. Unaweep’s geologic history is just as obscure, since there is no consensus about how the canyon’s combo of metamorphic gneiss, quartz monzonite, and sandstone areas came to be. The current hypothesis was that Unaweep formed in stages—the Gunnison River initially carved the canyon until a landslide dammed it, and then the river changed course in the opposite direction. Hence, the two mouths.

In terms of climbing, Unaweep has always had a loose community. It’s not far from western Colorado’s largest city, Grand Junction, but is overshadowed by its bigger sister, the Black Canyon of the Gunnison, to the south. Or most climbers simply drive by en route to Moab, or maybe stop to boulder down low on the black sandstone, failing to realize that just a few more miles up the road rise 1,000-foot granite walls.

Still, this trove of featured gray stone just a few minutes’ walk from CO 141, a winding two-lane back road from Junction to Naturita, is a worthy destination. With over 600 routes from 5.4 to 5.14, ranging from thin slabs to grinder offwidths to neo-classic multi-pitch sport and mixed climbs on wild flake, crack, flare, and roof features, Unaweep is stacked. And in a world of ever more crowded cliffs, it remains as sleepy as ever 32 years after the first documented climb.

The Age of Discovery

Welcome to Unaweep Canyon, where the Access Fund (AF) made its first-ever land acquisition for climbing, in 1992, and where the WCCC currently manages the rock that no one speaks about. Unaweep’s climbing history begins with Andy Petefish, a climber of 50 years and current owner of Above Ouray Ice & Tower Rock Guides. Petefish grew up in Grand Junction and began new-routing in Unaweep as a youth, inspired by Layton Kor and other Colorado legends. He would bike from Junction—a round-trip of more than 45 miles—to climb since gas was too expensive, his pack laden with a rope, chocks, and pitons.

One of Petefish’s best routes here is Questions and Answers (5.10), a three-pitch crack on Mother’s Buttress in the southerly central canyon. A long pitch of 5.8 jamming up a steep, smooth corner leads to the notorious second pitch, which tackles slippery face holds, laybacks, and finger cracks until reaching a well-protected traverse rightward under a roof. I recently caught my partner’s fall here as he pumped off near the roof, a not-uncommon scenario.

Another Petefish classic is Sweet Sunday Serenade (5.9; three pitches), perhaps the canyon’s most popular climb on its most popular cliff, the central Sunday Wall. Pitch two is the most enjoyable vertical fingers pitch in Unaweep. The smooth, constricting crack allows comfy jams and placements, while the corner walls drop away to the piñon-studded desert. Above, on a comfy belay ledge, you take in views of arêtes and lichen streaks on faraway walls, the crenellated granite fading into the distance.

Petefish also pushed the grades in Unaweep in the late 1980s, focusing on the faces between the cracks, which revealed skin-slicing crimps, technical rockover moves, and powerful lock-offs. His thin, sustained Bridge of Air (5.12) is a sport-style masterpiece that joins other Petefish Unaweep testpieces like Monkey Gone to Heaven (5.12+/13-) and Flight Without Wings (5.12). These routes were significant because they were harder than 5.11, on the best stone, and required strong fingers and power rather than just slab-and-crack skills. Petefish’s passion for climbing led him to become one of America’s first USMGA Endorsed Rock Guides; he began guiding at Mountain Sense, a now-defunct side project started by Eric Reynolds and Dave Huntley, the founders of Marmot, which was originally headquartered in Grand Junction.

Another key player has been KC Baum, who began his climbing career in 1976 while working as a geologist in Fort Collins, Colorado. Baum and his family moved to Grand Junction in spring 1987 when he took a job developing the climbing program for Mesa State College. In January 1989, Baum started his Desert Rock Guides, and also joined the American Mountain Guides Association (AMGA). In 1991, he was drafted onto the AMGA Instructor Team and has remained in this position to the present day.

Still, as traveled and experienced of a climber/guide as he is, Baum’s favorite area remains Unaweep. As he says, “Unaweep will always remain very sacred to me, and was without a doubt the pinnacle of my climbing career.” During his 6.5 years of establishing routes here, Baum is credited with over 100 FAs—many cracks but also mixed and bolted climbs. (Unaweep, fortuitously, escaped the 1980s “bolt wars.” Baum recalls that the few climbers then new-routing in Unaweep climbed together, and respected each other’s visions.) In 1992, he published Grand Junction Rock – Rock Climbs of Unaweep Canyon and Adjacent Areas, the area’s first guidebook, and followed up with a second edition in 1997. He also takes pride in having convinced the Access Fund to donate two $5,000 grants to buy three popular walls on private property—Sunday, Hidden Valley, and Fortress walls—marking AF’s precedent-setting first purchase of a climbing area. While Baum has since moved to Flagstaff, Arizona, his influence on the canyon cannot be underestimated.

Rite of Passage, a 5.11 on the Quarry Wall, is perhaps Baum’s most treasured Unaweep FA. Using a Soloist self-belay plate, Baum climbed ground-up—the first time he’d done an FA self-belaying—around the time the alpinist Mugs Stump passed away (1992), naming the route as a tribute to his friend. The Quarry Wall is perhaps Unaweep’s crown jewel for hard climbing—north facing, about a quarter-mile long, 200 to 300 feet tall, and lined with over 100 sport, mixed, and crack climbs. As the lower wall is largely blank, most cracks begin at half height, but Rite of Passage is one of the few that begins from the scrub-oak-lined canyon floor. At the crux, 25 feet above a thin nut in the exfoliating granite, Baum “was in a full-body stem and shaking like a leaf. I remember thinking, ‘Well, you idiot, this is how it’s going to end and you’re about to kill yourself!’” Baum somehow held it together, gunning for an archetypal Unaweep no-hands rest. Here, he collected himself and finished up a stemming hand crack/chimney to the canyon rim.

Another of Baum’s most vivid memories came while establishing a new route on the 800-foot Thimble, near the beginning of West Creek. There, he found old ring pitons and tattered hemp rope from the Tenth Mountain Division, Army soldiers who conducted intense, specialized training in Colorado to prepare for mountain combat during World War II. My experience while new-routing on the Thimble was less illuminating. In 2013, my friend Chris Righter and I were threatened by the landowner’s land manager at gunpoint and given five minutes to vacate—when we were already 600 feet off the deck, with no natural rap anchors and our only descent option being hand-drilling bolts (try doing that in five minutes!). Fortunately, Chris clarified, yelling that the guidebook stated climbing was legal and we didn’t know we were trespassing. The land had changed hands since the book came out, and the new owners, it seems, were not “climber friendly.”

The Modern Age Begins

In the 1990s and early 2000s, itinerant climbers put up most of the new climbs, from mixed routes to increasingly difficult sport climbs. However, with no updated guide and Mountain Project still in its infancy, many climbs went undocumented. Nonetheless, one climber made a notable influence: Jim Beyer, the legendary, reclusive solo wall climber.

Beyer had generally been a loner while living near Grand Junction, as with his overall career. He has established difficult free and aid climbs from Colorado to Yosemite to Baffin Island, his first-ascent efforts living on the fringe of the possible. He is also a notorious character—take this comment he appended to his Mountain Project route description for his Hardscrabble Tower (Canyonlands) FA Cult of Suicidal (A5+) in 2016:

After summiting Cult of Suicidal, I noticed a park ranger on the road. Upon descent the ranger notified me that bikers on the White Rim had snitched on me (hammering is against the stupid rules) in Canyonlands NP. He wrote me a ticket for $50 and left. Later, driving out, fast and reckless, I approached a group of bikers. I passed some riders then four-wheel-drifted round a corner, spotting an exhausted woman pushing her bike in the sandy doubletrack ahead. She stepped up out of the doubletrack “ditch” and I didn’t slow down. I expected her to pull her bike up out of the ditch in the nick of time. She didn’t and I drove right over her bike. She started screaming immediately but I didn’t stop because I was laughing too hard.

In Unaweep, the majority of Beyer’s 100 single- and multi-pitch, mostly free and aid lines routes climb paradoxical features like cracks with no gear or smears with no friction. His climbs often require out-of-the-box movements like two-handed mantels or desperately “falling upward” from one stance to the next, while the “pro” often takes the forms of fixed bashies smashed into seams and similar oddities. Take Beyer 2, an infamous 5.11+ on the Sunday Wall. The route trends leftward, following barely climbable features, involving balancey stances, hard slabbing, and awkward sidepulls that force you to cut your feet on the slippery granite. I’ve loved every one of Beyer’s routes because he allows you to feel what it’s truly like to be on lead, in a committing but not necessarily dangerous way. His routes typically end at anchors consisting of hangerless studs with washers and one chain link, equalized with a bashie.

At the same time Beyer left Grand Junction, Jesse Zacher moved in from Pagosa Springs, Colorado, to take the lead. In 2005, he not only found a wide-open first-ascent canvas but also the chance to help with local stewardship, joining with Eve Tallman to form the WCCC. Zacher made it a goal to climb all the routes along the base of the Sunday Wall and Mother’s Buttress in order to begin the arduous process of compiling an updated guidebook. As he explored the canyon, Zacher began to unlock many neo-classics of his own.

One of Zacher’s best new routes must be The Velvet Hammer (5.11+), a left-facing corner on the Massey Wall sector of Quarry Wall, sent in April 2012. Rapping the route that winter, he saw that it was a natural drainage for the plateau above and was grown over with moss and lichen. Zacher spent hours toproping, cleaning, sussing, and debating whether to place a crux bolt. Eventually, he decided that the fall wasn’t that big (it’s not, and is well protected), and when he freed the climb on gear he broke through a climbing plateau, marking a major turning point for his journey toward repeating and establishing harder routes in the canyon, including Comb the Desert (5.11+), Frozen Will (5.11+), and Bachelor Party (5.11+).

The Velvet Hammer’s rock is impeccable, and the dihedral allows you to back-scum, stem, jam, and rest, with just enough small edges to keep the grade consistent. Another notable Zacher FA at the same cliff is Frozen Will (5.11+), a two-pitch climb established in winter 2015 up a giant shield of fissure-riddled rock. On one attempt on a 25-degree day, Zacher’s partner, with frozen hands, accidentally dropped his belay device. This led to his partner hand-over-hand “rappelling” and bushwhacking out to the road, as Zacher was already up top and his partner felt safer descending.

Zacher’s ability to find new routes is only rivaled by his work with the WCCC. With “no term limits” on his presidency, he has developed a strong relationship with the AF to navigate land acquisition and the preservation of access in Unaweep. In the canyon, most of the rock lies on private land. Additionally, there are only a few legal access points to reach the walls on BLM or National Forest land, which creates sometimes-lengthy approaches without an established trail. Fortunately, Mother’s Buttress, Sunday Wall, Quarry Wall, Spaceballs Wall, and Unaweep Wall all have easy and legal access. As Zacher puts it, our voice through the WCCC is based on climber numbers. The organization currently has 150 members, a mere fraction of the estimated 1,000 climbers in the Grand Valley. Busy weekends in Unaweep consist of maybe two dozen climber cars spread out between the sandstone routes and boulders near the bottom of the canyon and the granite up higher. Zacher hopes, with his new guidebook forthcoming, that interest in the area will continue to grow, with increased climber numbers providing a louder voice.

Unaweep Today

For the past seven years, friends and I have slowly been establishing new routes in the canyon—nearly 100 new pitches. Though I work as a science teacher at R-5 High School in Junction, my passion is establishing new rock climbs. Since the majority of obvious crack and slightly mixed routes were climbed years ago, I’ve been pursuing the highly featured, yet often exfoliating, discontinuous, flaky, licheny, and overhanging sporty sections.

I remain fondest of my first new line in the canyon, Echoes, a 600-foot, six-pitch 5.12+ up the steepest, tallest portion of the Sunday Wall. After getting skunked on my dream crack pitch near the top during a scoping mission (there was a six-foot blank section), I relocated eastward into an unlikely dihedral and face. Pitch three is wild, tackling a right-trending, gear-protected traverse that eventually turns into a bulging undercling crack with a bouldery, bolt-protected vertical slab exit. While redpointing, I would end up 50 feet or more to the right, way above my belayer, only to take monster whippers. Pitch five is memorable as well, a 35-meter rope-stretcher that combines pumpy corner laybacking with a crimpy iron-cross boulder problem and thin deadpointing to a techno-freak finish. Echoes opened my eyes to the vast potential on Unaweep’s discontinuous cracks. As a rule, each new pitch requires one-plus hours of scaling away the exfoliating outer skin to reach better stone beneath. Then it’s time for some “Unacreeping,” in which you balance, smear, swear, layback, crawl, and otherwise improvise your way up the rock.

Another standout is the 190-foot Jane’s Marathon, a gently overhanging 5.13 I put up in August 2016 on the Quarry Wall and named for a race my wife was training for. When I first rapped the line, I thought that it would be 5.11—Unaweep can be deceptive that way. After working the moves on Mini Traxion, I realized I was wrong. The climb only had a natural stance very near the bottom, so I climbed it in one big pitch. The final redpoint involved carrying 20-plus pieces, 15 slings, patience, power, and total precision. The route has everything: overhanging finger cracks, slopey laybacks, boulder problems, crux roofs, and committing slabs. Righter described it as one of the best routes he’s climbed, akin to rope-stretchers like Beer Run and The Anti-Phil at Rifle Mountain Park—only longer. Our respective sends each took 45 minutes, a meticulously organized rack, and perfectly rehearsed beta.

Today, Unaweep Canyon has its small cadre of active locals, its weekend visitors nabbing an ascent of Sweet Sunday Serenade, and traveling outdoor-education programs stopping through. Mother’s Buttress and Sunday Wall are chockfull of 5.10 and 5.11s to help you prep for the Black Canyon or any other granite venue, and even the sleepy Unaweep Wall now has five big lines from 5.11 to 5.13. And in summer, the north-facing Quarry Wall offers its 100-odd pitches varying from pure traditional to mixed to bolt protected—it’s almost getting used! There are too many new routes to detail here, from 5.5 clip-ups to 5.14 sport climbs, with many more to come. Unaweep remains under the radar, a little wild, and still ripe with the potential for adventure. But now its two mouths are speaking more loudly. Maybe somebody will listen.

Unaweep Must-Dos:

Welcoming Party (5.7)

A short, smooth corner system, full of secure stems and jams.

A Fine Line (5.8)

A Mother’s Buttress classic, with a well-protected chimney to fingers.

Sweet Sunday Serenade (5.9)

A trad-climber’s dream, with old-school hands, fists, and fingers.

Questions and Answers (5.10)

A stout combination of large hands in a dihedral followed by delicate face moves protected by thin gear.

Lonestar (5.11)

Vertical terrain on jugs leads you through a few balance moves and out a bulge; this route is reminiscent of Rifle, with big, blocky holds and steep terrain.

Wintertime Joy (5.11+)

A wild and varied 1,000-foot monster up Unaweep Wall that includes corners, slabs, jamming, and mixed pitches.

Pig Nose (5.12-)

This long mixed line begins with gear in a swerving crack and ends on bolts and a pumpfest out a juggy bulge.

Echoes (5.12+)

Six hundred feet of smooth, fine-grained granite, mixing face, slab, and bulges to technical stemming and underclings into a laybacking headwall dihedral.

Dance Erotically (5.13-)

Three unique pitches: clean, vertical, varied jams; powerful underclings and smears under a roof; mixed face and offwidth moves to the canyon rim.

Jane’s Marathon (5.13)

190 feet of everything—roofs, slab, fingers, flares, boulder problems, and exposure.

Infinity Round (5.14-)

A two-pitch sport climb. P1: Desperate, pumpy sloper laybacking. P2: A series of stacked, short boulder problems.

Rob Pizem, a high school science teacher in Grand Junction, Colorado, has been climbing and new-routing for more than 25 years.

The post The Splitter Cracks and Mind-Boggling Movement in Unaweep Canyon appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

This article was originally published in Climbing No 371. It's appearing now in front of the paywall for the first time.

The post Classic Routes: Cathedral Ledge’s “Life, the Universe, and Everything” (5.14a) appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

On October 14, 2018, Jay Conway, a math teacher at Plymouth Regional High School, New Hampshire, stared up at the fourth ropelength of what was poised to become a new, five-pitch 5.14a on Cathedral Ledge. The route was Life, the Universe, and Everything, on the cliff’s forbidding Mordor Wall. Above him rose the 5.13c Edge of Bridge pitch, which tackled V8 refrigerator wrestling—the climb’s most difficult moves. To get here, Conway had climbed the 5.11+ first pitch of Cecile; a crux, 5.14a second pitch via his 2013 Difficulties be Damned that exited via a tough, new V4 mantel; and a sparsely bolted 5.12b “enduro slab.” Conway, supported by his friend Pete Arnold, had already put in five tries over three hours on the Edge of Bridge and was exhausted. If he could make it past the 30 feet of 5.13 above, only a 5.10b section guarded the summit.

While Cathedral is known for its multi-pitch free classics like Thin Air (5.6), Recompense (5.9), The Prow (5.11d), and Liquid Sky (5.13b), the dark, roofy, and seemingly holdless Mordor Wall has mostly been the domain of aid climbers. In years past, the hardest free climb there was Tim Kemple Jr. and Sr.’s Highway 61, a three-pitch, zigzagging 5.13a. “With Rumney close by, most of the 5.13s at Cathedral see very little traffic,” Conway says—with its mixed climbing and funky fixed pro, Cathedral has kept its mantel as the traditional bastion of New England.

In 2013, Conway, now 39, looked between the fixed bashies and old-school mank on the Mordor Wall to find Difficulties be Damned, a mixed pitch with five bolts and five pieces of gear. In spring 2018, he returned to scope a left exit to Difficulties. “That cliff is roadside and has been climbed at since the 1920s,” Conway says. “It’s picked over. I was shocked that I found stuff above that line”—including the 20 new feet off of Difficulties that segue into the new, upper pitches. “All the routes just seem so impossible at first,” Conway says of Cathedral Ledge’s smooth, fine-grained granite, “but once you figure out that almost everything is a foothold, the routes seem to click.”

After his fruitless battle on the Edge of Bridge, Conway rested at the belay. He queued up “Damn It Feels Good to be a Gangsta” by the Geto Boys and got psyched for a sixth attempt. This time, Conway fought through the second V8 boulder problem, with its balancey windmill move, finally sticking the sequence. “It was like my version of the Dawn Wall,” he says. Elated, Conway romped up the last ropelength at dusk, bringing two and a half pitches of new climbing and a proud, new 5.14 to Cathedral Ledge.

Location

Mordor Wall, Cathedral Ledge, New Hampshire

Grade

5.14a

Length

400 feet; five pitches

First Ascent

Jay Conway, October 2018

The post Classic Routes: Cathedral Ledge’s “Life, the Universe, and Everything” (5.14a) appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

In his “Forgotten First Ascents” series for Rock and Ice, Owen Clarke dug up cool climbs from the past and talked to the climbers who made them happen. This one: Malaria, Rhumsiki Tower, Cameroon, 2007.

The post Not Even Cannibals And One Of The Deadliest Snakes Could Stop This First Ascent appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Massimo Faletti was battling up the third pitch of Malaria (7b+/5.12c A2) a 340-meter (1,115 foot) line on Rhumsiki Tower, a spire in the high desert of far northern Cameroon, Africa. His two teammates, Mario Cavagnini and David Rigotti, were on the belay ledge below. Suddenly, he heard yelling. “Hey Mass! We have to leave the belay!” Cavagnini called. “We have to leave, now!” Confused, Faletti looked down, trying to figure out what was going on, but the belay was out of sight.

Unknown to Faletti, a massive black mamba, one of the most venomous snakes in the world, was slithering onto the belay ledge from a crack. In a panic, his partners tied him off and bailed over the side of the ledge. Black mambas can move at 12 miles per hour in short bursts. Their bite, which releases a powerful neurotoxin, can kill in 20 minutes without an antivenin, and as little as two drops will kill an adult human. Luckily, the pair was able to give the snake a wide berth until it left. Fifteen minutes later they returned to the ledge, put Faletti back on belay, and he continued up Rhumsiki.

[Also Watch VIDEO: Of Choss And Lions: Honnold, Wright And Birdwell In Kenya]

Rhumsiki Tower sits on Cameroon’s border with Nigeria, in the volcanic Mandara Mountains. There were two other routes on the tower when Faletti and his team arrived: a French route to the right of Malaria, and a South African-American one (a 5.12d put up in 1999 by Mark Synnott, Greg Child, Ed February, and Andy Deklerk) on the left. Unlike the two other lines which were fully bolted, Malaria was established ground up on traditional gear, save for some bolts backing up the belays and a single aid move over a crux roof. Faletti first heard about Rhumsiki from a filmmaker friend, Marco Prati, who was interested in shooting a documentary in Cameroon. When Prati showed Faletti pictures of the tower, he was hooked. If Prati would help him document an ascent of the tower, he said, he would come to Cameroon and help him with the rest of his documentary.

But access to Rhumsiki wasn’t that simple. The team traveled by local bus and train to reach the far north, and were stopped on four separate occasions by “policemen” wielding Kalashnikov rifles. “It was a dodgy, dodgy trip,” said Faletti, laughing. “They had no identification. It was just a man with a rifle, he told you to get on the ground with your face in the dirt. You had to pay to get out.” Each of these “arrests” cost them €30, but Faletti felt no ill will. “They only want money because they need it,” he said. “We, the white people, were the worst problem for Africa. We stole lots of things in the African land for years, so the people are pissed off. I can understand this anger.”

Literal highway robbery was far from the only hazard the team encountered in Cameroon. Faletti was allergic to the antimalarial medicine he was taking, and at one stage in the trip his legs began to blister swelled up like balloons. “We go to this local priest,” Faletti told me, “for some medicine and help. This priest says we must be careful to travel, because last week a van disappeared on the road here. He says every year a few vans disappear. He says there is a cannibal tribe. This tribe… they catch the van and take the people back to their village, then they eat the people in this village.”

Upon safely reaching Rhumsiki, the first thing the Italians did was visit the nearby village to ask the leader for his blessing. This went smoothly. “We offered him something to drink, we asked him, and he said it was no problem,” said Faletti. Next, they went to consult the local crab sorcerers. These medicine men, who live outside the village, predict the future using a combination of crabs, bones, and stones. “I don’t have much religion myself, but it’s important to respect the local religion wherever you go,” said Faletti. “You can’t walk with shorts into a mosque, stuff like that. You respect the culture of where you are, so we asked the crab sorcerers about what would happen on the tower.” The sorcerers placed the crabs in a pot with bones and stones, and the crabs moved the them. After a minute or so, the sorcerer took the crabs out and read the prediction based on the placement of the bones and stones. “They looked at this preview and told us we could climb the tower,” Faletti said. “So we did.”

The team hauled their gear to the base of the climb, set up camp and began working their way up. Conditions were “a real tragedy,” as Faletti put it. The sun was so brutal on Rhumsiki that the team could only climb between 4:00 am and 10:00 am. By 11:00 am each day, the temperatures on the wall reached a blistering 45 degrees Celsius (113 degrees Fahrenheit).

Along with the black mamba, the team encountered vultures. At one point, a large owl flew out of the crack and into Faletti’s face as he was 10 meters run out above his last piece of protection. He held on, but was angry with himself. “I get pissed off at myself when this happens, because it means I disturbed the nature,” Faletti said.

Faletti described the crux pitch as a 7a (5.11d) crack leading into a 7b+ (5.12c) roof. “From there you have an undercling, and you must jump out and up to a small edge outside the roof,” he said. He attempted a wild all-points off dyno to the edge—two feet above the lip of the roof— several times, but when he couldn’t stick it he put in a piton and aided through it. He believes the pitch could go free at 7c (5.12d) or harder,

All told, Malaria went down in three days. David Rigotti only climbed with the team for the first three pitches, then left with Marco Prati to work on the documentary. Faletti led every pitch on Rhumsiki, as his other partner, Mario Cavagnini, was mostly a sport climber.

Even after they climbed the tower, the team wasn’t out of the woods. Shortly after finishing the climb, Cavagnini fell ill with malaria, battling a 105-degree fever. He recovered, and his experience became the inspiration for the route’s name.

“If you are an alpinist like me… when I go on these trips it is my vacation. I don’t have sponsors giving me money,” said Faletti. “Maybe some boots or clothes sometimes, but that is it,” he said. “It is not a job, it is my vacation. So I think it is even more important to bring knowledge of the natural world when we come, and bring a positive impact. So we study the local culture before we come, the customs. We stay out of the village and camp, we keep everything clean, bury our shit, pack out our trash. This is most important,” he said. “You must respect the local people. It is their country.”

Owen Clarke is a climber and writer who enjoys Southern sandstone and fresh fish tacos. He is afraid of heights. Follow him on Instagram at @opops13.

Also Read

The post Not Even Cannibals And One Of The Deadliest Snakes Could Stop This First Ascent appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

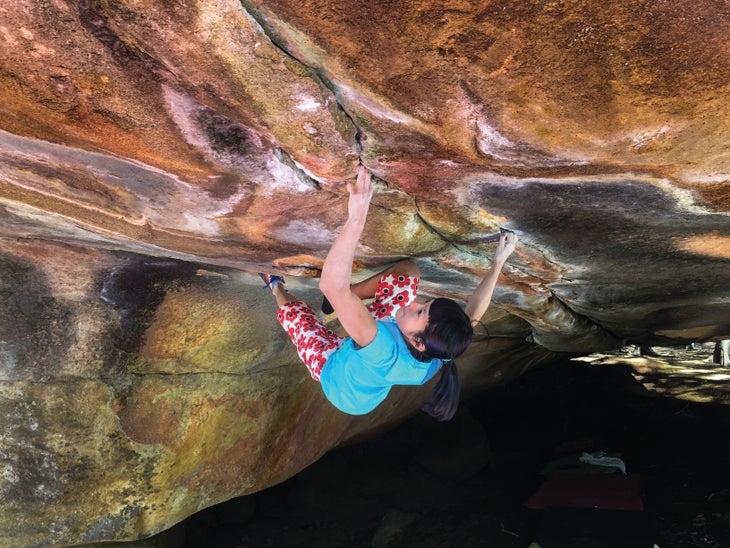

A V16, a V15 first ascent, and a V14 first ascent… in just three days.

The post Drew Ruana Just Had the Best Three Climbing Days of His Life appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Last week, Drew Ruana had his most productive three days of climbing to date. On Wednesday, October 5, he nabbed the long-awaited second ascent of Daniel Woods’s Ice Knife Sit (V16) in Colorado’s Guanella Pass. On Thursday, he FA’d Ozymandias, a technical new V14 in Clear Creek Canyon. And on Friday, he did the FA of The Player, the V15 right exit to Daniel Woods’s The Game (also V15) in Boulder Canyon.

“Everything just kind of clicked,” Ruana told Climbing. “I thought it was going to take weeks to do those three boulders. …It was the best three days of climbing I’ve ever had.”

This flurry of hard ascents comes on the heels of a productive summer during which the college junior, who’s trying to send every problem V14 and harder in Colorado, started to focus a bit more on establishing new hard lines.

The post Drew Ruana Just Had the Best Three Climbing Days of His Life appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

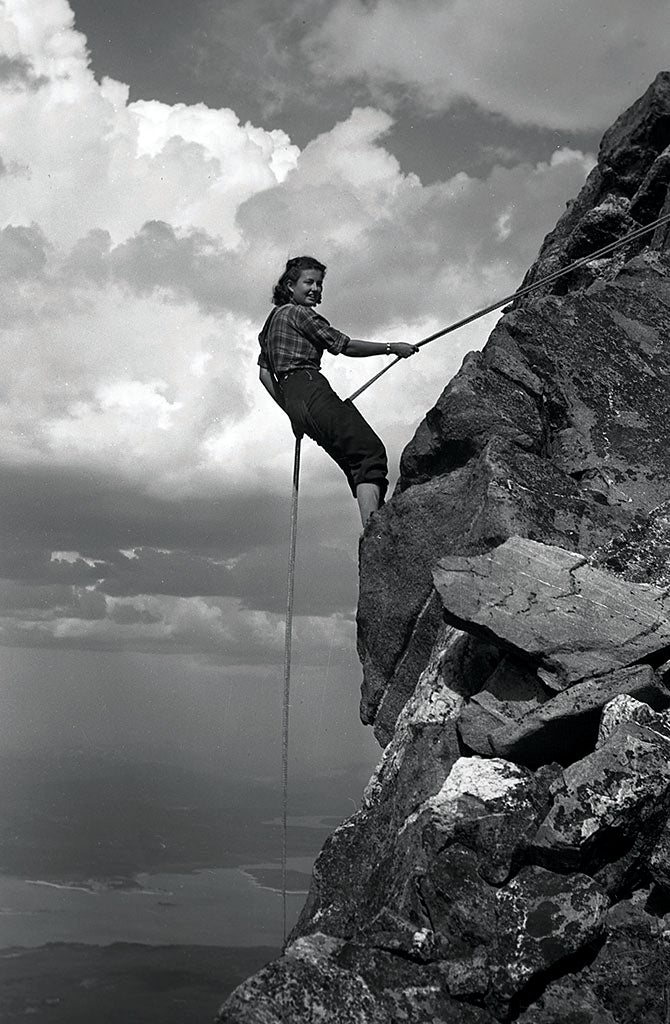

From the first women recorded in mountaineering in the late eighteenth century, to the first 5.15 female ascent by Margo Hayes in 2017.

The post A Consolidated History of Women’s Climbing Achievements appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

For centuries, women have pushed their limits in the mountains. For nearly as long, they’ve done so behind the scenes and rarely received proper credit, being recorded as “Sir William’s Wife” or left unnamed. And when a woman did summit, it wasn’t due to her own strength but—as the narrative often went—to the men on her team who surely carried her across crevasses, hauled her pack, and held her hand on the most daring precipices. Women have persisted, though. Since women were recorded in mountaineering in the late eighteenth century, to the first 5.15 female ascent by Margo Hayes in 2017, the call of the mountains has been as strong for women as it has been for men.

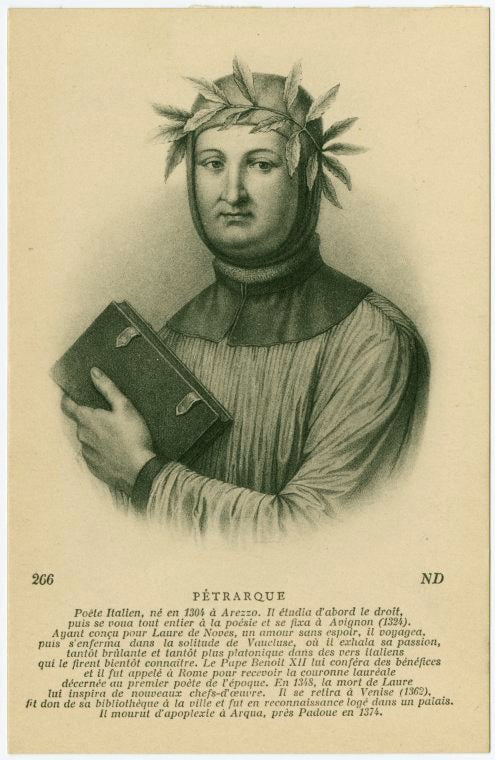

1799: The Beginning

Although the first documented ascent of a mountain was Mount Ventoux in 1336 by the Italian poet Petrarch (above), the first recorded female ascent wasn’t until 1799, when the mysterious Miss Parminter climbed “on” Le Buet (10,157 feet) in the Alps of Savoy. Shortly thereafter, in 1808, Marie Paradis became the first woman to climb Mont Blanc. However, her ascent went widely unknown. Thus 30 years later, French aristocrat Henriette D’Angeville, outfitted with six porters, six guides, and a 14-pound outfit including multiple layers, a petticoat, and a feather boa, summited Mont Blanc and proclaimed herself the first woman to do so. She did this with flare, releasing a carrier pigeon and popping open champagne on the summit.

1800s: Walker and Brevoort

Lucy Walker, rumored to have lived on sponge cake and spumante, became the first woman to summit the Matterhorn, in 1871, after hearing that her contemporary Meta Brevoort planned to snag the FFA. At that time, Brevoort was known for her “scandalous” fashion choices, often choosing pants over skirts on her ascents. Walker would go on to complete 98 expeditions and became an involved member of the Ladies Alpine Club, created in 1907 in London as a response to Britain’s strict “male-only” Alpine Club.

Late 1800s/Early 1900s: The Right to Vote

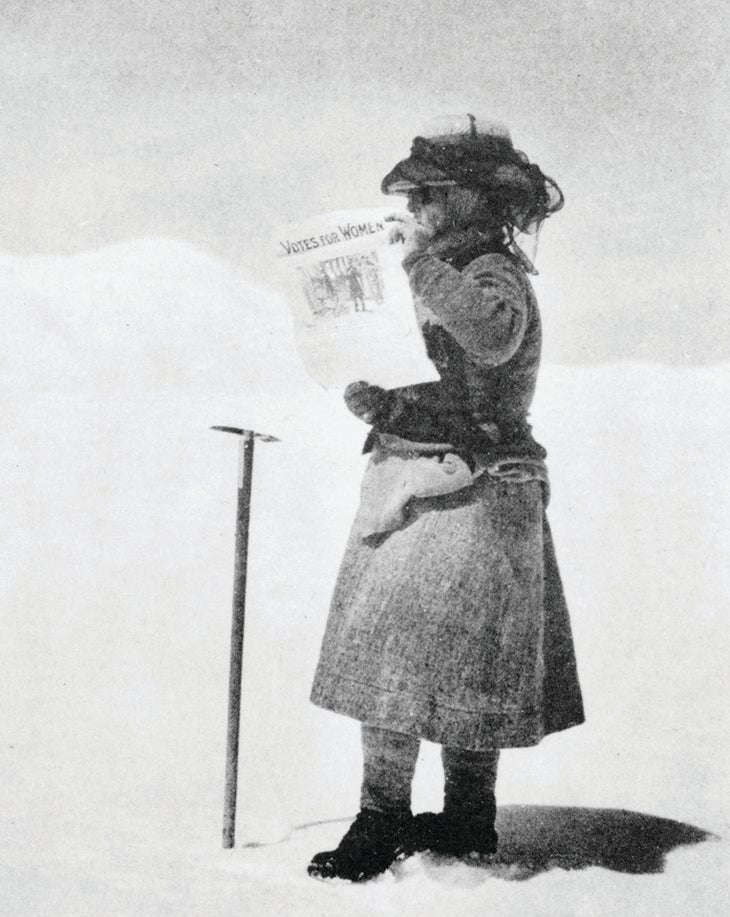

During the late 1800s, when women were getting their start in alpinism, men began rock climbing in the Elbsandstein of Saxony, the Lake District of England, and the Dolomites. While OG Jones was making his 1897 FA of the Lake District’s Kern Knotts Crack (5.8 PG-13), women were thinking of the right to vote. Annie Peck, a founding member of the American Alpine Club, climbed Coropuna (21,079 feet) in Peru in 1911, and waved a banner atop the summit reading “Women’s Vote.” Meanwhile, Fanny Bullock Workman, while surveying glaciers on an expedition in the Karakoram, was photographed with a “Votes for Women” sign (above). (Workman trekked to the Himalayas to climb Pinnacle Peak [22,735 feet] in 1906, establishing a new female altitude record.) Through the efforts of Workman, Peck, and countless other suffragettes, women won the right to vote with the ratification of the 19th amendment on August 18, 1920.

1920s: Miriam O’Brien Underhill

In the mid 1920s, Miriam O’Brien Underhill made the traverse from Aiguilles du Diable to Mont Blanc du Tacul, tagging five 4,000-meter summits. In the late 1920s, she coined the term “manless climbing” and in 1929 nabbed the first such ascent of the Grépon with Alice Damesme. Shortly after the ascent went public, the French mountaineer Étienne Bruhl infamously shook his head and stated, “The Grépon has disappeared. Now that it has been done by two women alone, no self-respecting man can undertake it. A pity, too, because it used to be a very good climb.”

1930s: The Owen-Spalding

Negative sentiment toward women is easily found throughout our history in climbing, including in America. In 1939, a group of women from Jackson Hole, Wyoming, made the first female ascent of Owen-Spalding (II 5.4) on the Grand Teton. Margaret Smith Craighead (above), Margaret Bedell, Ann Sharples, and Mary Whittemore awoke earlier than other climbers to ensure critics couldn’t attribute their victory to the help of men. After their milestone, the Salt Lake City Tribune reported, “Another successful invasion of the field of sport by the weaker sex.”

1930s: Marj Farquhar—“Strong Like Lhotse”

Thankfully, the slights women climbers endured only solidified their goals. Like Marj Farquhar, who became the first woman to send Yosemite’s Higher Cathedral Spire in 1934, via its Regular Route. Farquhar, an active member of the Sierra Club, belonged to a small group of climbers who learned modern rock-climbing techniques from Robert Underhill, who imported them from Europe. Marj and her husband, Francis, were leading environmental activists in the mid-1900s, and remained at the epicenter of Yosemite’s early climbing years. “If people were mountains,” wrote Nicholas B. Clinch in his “In Memoriam” article, published in the 2000 American Alpine Journal, “Marj Farquhar would be Lhotse… strong, impressive, and rising far above most other mountains.”

1940s-’50s: WWII, Washburn, Prudden, and the Stanford Alpine Club

In the 1940s and ‘50s, World War II and its aftermath demanded everyone’s attention, and climbing came to a near-standstill. In 1947, Barbara Washburn became the first female to summit Denali (20,320 feet), and Bonnie Prudden became prominent in the Shawangunks, putting up some 30 FAs, including Bonnie’s Roof (5.9) and Boston (5.5 PG-13). The Stanford Alpine Club made their debut in 1947, with a nontraditional stance, welcoming women and celebrating “manless” climbing. Mary Sherrill, Freddy Hubbard, Irene Beardsley, and Sue Swedlund all made notable first all-female ascents of climbs like the Regular Route on Higher Cathedral Spire (Sherrill and Hubbard) and the North Face of the Grand Teton (Beardsley and Swedlund).

1960s: The Golden Age and The Feminine Mystique

The 1960s ushered in the Golden Age of Yosemite Valley. In 1967, Liz Robbins, along with her husband, Royal, ticked the Regular Northwest Face of Half Dome, becoming the first woman to climb a VI big wall (photo above shows them on the summit after their climb). Liz also attempted the Nose in 1967 with Royal, but the pair rappelled after 600 feet due to heat and insufficient water. In 1971, Johanna Marte became the first woman to scale El Cap—as a non-leading client of Royal Robbins. The 1960s also introduced Betty Friedan’s book The Feminine Mystique, which inspired thousands of women to find fulfillment beyond the role of housewife. Until its release, women spent 55 hours per week on chores and child-rearing, and less than 10 percent of all doctors, lawyers, and engineers were women. The women who pursued climbing were on the fringe of an already-fringe society. They rejected cultural norms, put off children, and pursued life with their own sense of purpose.

1970s: First All-Female Ascent of El Cap

Riding the wave of nonconformity that began in the 1960s, Beverly Johnson (above, at Camp VI) and Sibylle Hechtel made the first all-female ascent of El Cap via the Triple Direct (VI 5.9 C2-), in 1973. After seven days of learning how to haul bags that weighed more than both of them, throwing themselves into a sea of granite, and mustering every ounce of grit they had, the two topped out the 2,900-foot behemoth. While the women were on the wall, Valley climbers wagered for and against them. Their ascent marked a turning point for female climbers. Around this time, in 1972, Title IX became law, making sports equal opportunity for men and women. Prior to its passing, only 294,015 girls nationwide participated in sports. According to the 2015-2016 survey by the National Federation of State High School Associations, that number has grown 1,030 percent to 3,324,326 female participants.

1970s: Beverly Johnson and Ellie Hawkins, Yosemite

Soon after the Triple Direct, Johnson soloed the Dihedral Wall (VI 5.8 A3), while Ellie Hawkins soloed multiple Yosemite climbs including Never, Never Land (VI 5.9 A3) and the first ascent of Dyslexia (VI 5.10d A4), so named to bring awareness to a condition she’d battled her whole life. According to a 1985 LA Times article, while Hawkins soloed Dyslexia she “began to see in mirror images, and her shoelaces and her rope momentarily disappeared from her field of vision.” In 1977, Molly Higgins and Barb Eastman made the first all-female ascent of the Nose.

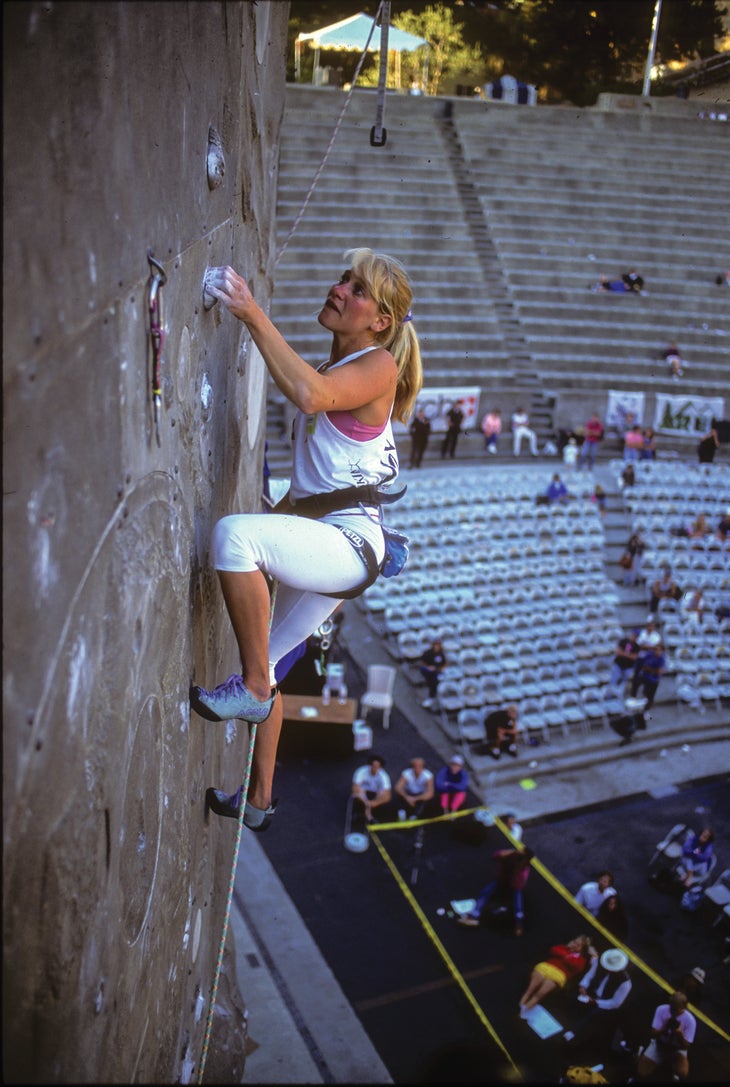

1980s: The Comp Era Begins; Women Tick Hard Sport Routes

The 1980s brought a new spin: competitions and indoor gyms. In 1985, the first SportRoccia event was held in Bardonecchia, Italy (it later became the Rock Master comp), and Catherine Destivelle, known previously for alpine climbing, took first place. A year later, Lynn Hill learned about the competition while climbing in France, and returned to enter. In a “disputed ruling,” Destivelle retained her position on the podium, while Hill, overwhelmed by the changing rules and regulations, took second. The two remained close competitors until Destivelle returned to alpinism in the 1990s. During this era, it finally felt like women were receiving their proper due. Luisa Iovane, and Italian climber, entered the competition circuit and climbed Comeback (5.13b; above) in 1986. And Isabelle Patissier sent Sortileges in 1988, becoming the first woman to climb 5.13d.

Early 1990s: Lynn Hill Climbs 5.14 and Frees the Nose

In 1990, Lynn Hill became the first woman to redpoint 5.14a with Masse Critique in Cimai. Hill’s passion for the sport and progression through the most difficult grades landed her on talk shows, and made her a crowd favorite at competitions. Hill had come to Yosemite Valley in 1978 as a 17-year-old, and quickly gained a spot under the wing of the Stonemasters, a group of freewheeling climbers from Southern California. She found a climbing partner in Mari Gingery, and in 1979, the pair completed the first female ascent of The Shield (V 5.8 A3) on El Cap over six days. Hill has many other noteworthy firsts including Vandals, a 5.13a trad route in the Gunks, along with her 1993 free ascent of the Nose (VI 5.14a), where she famously pronounced, “It goes boys!” Hill then returned in 1994 to free the route in a day.

Mid-1990s: Robyn Erbesfield-Raboutou Crushes All Comps

In the mid-1990s, Robyn Erbesfield-Raboutou won four World Cups in a row and became the third woman ever to send 5.14, a feat she continues to accomplish in her 50s with ascents of Philipe Cuisinere (5.14a) in 2016 and Thunder Muscle (5.14a) in 2017. She also won every competition she entered in 1993, as well as five US championships in her time as a competitor. Now she’s raising her children under the wing of Team ABC, part of the ABC Kids Gym, a bouldering and training facility she founded with her husband, Didier, in Boulder, Colorado. Their daughter, Brooke, 16, has sent V13, and is the youngest person to climb 5.14b with her ascent of Welcome to Tijuana, in 2012 at 11 years old.

Mid-1990s: Third Wave Feminism; Women Shred in Droves

The Family and Medical Leave Act in 1993 and the Gender Equity in Education Act in 1994 allowed women to stand up for themselves in education and at work. Women’s numbers in the Senate doubled, Janet Reno became the first female Attorney General, and Ruth Bader Ginsburg became the second woman appointed to the Supreme Court. Meanwhile, women worldwide were working to abolish gender stereotypes and role expectations, creating the “third wave” of feminism. In climbing, the rise of gyms and competitions ushered in a major uptick in women climbing hard. In 1996, Mia Axon became the fourth woman to redpoint 5.14 with Planet Earth (5.14a) in the Virgin River Gorge. And in 1999, Katie Brown became the first woman to onsight 5.13d with Omaha Beach in the Red River Gorge at age 18, after mistaking the new climb for a 5.12 warm-up.

Late 1990s-Early 2000s: Josune Bereziartu and 5.14+/15-

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the Basque Josune Bereziartu became the world’s best female sport climber. After encouragement from friends to become the first woman to redpoint 5.14b, Bereziartu began projecting Honky Tonky in 1997 and succeeded in 1998. She continued to break records, becoming the first woman to redpoint 5.14c, 5.14d, and 5.14d/5.15a with Honky Mix (2000), Bain de Sang (2002), and Bimbaluna (2005), respectively. Bereziartu’s ascents dramatically narrowed the gap between men and women, and by the late 2000s women were climbing 5.14 in numbers never seen before.

Mid-2000s: The Art of the First Ascent

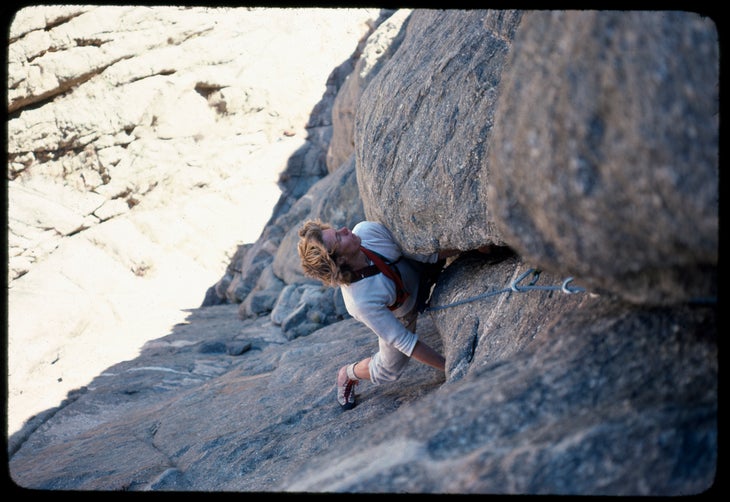

One of the most impressive things women have been doing in ever greater numbers since Lynn Hill freed the Nose is cutting-edge first ascents. In 2004, Beth Rodden established The Optimist, a 5.14b seam in Smith Rock. Then, in 2008, she redpointed her 40-day project Meltdown, a 5.14c trad climb that became the hardest pitch in Yosemite at the time. Meltdown has remained unrepeated despite attempts from numerous strong climbers. Other examples of hard recent female FAs include Utah climber Jacinda “JC” Hunter’s 2010 route Fantasy Island (5.14b) in American Fork—completed while raising four kids and working full-time as a nurse; Paige Claassen’s 2013 FA of Digital Warfare, a 5.14a sport climb in South Africa (above); Isabelle Faus’s FA of The Dark Daughter (V13) in 2016 in Rocky Mountain National Park; and Barbara Zangerl’s 2017 first free ascent, with Jacopo Larcher, of Gondo Crack (5.14b) in Switzerland.

2010s: A New Era—Sasha DiGiulian, Ashima Shiraishi, and Margo Hayes

In the late 2000s to present day, the gap between men and women has narrowed to a sliver. In 2011, Sasha DiGiulian became the first American woman to climb 5.14d with her ascent of Pure Imagination (later downgraded to 5.14c), and in 2013 became the first female up the adventurous Bellavista (5.14b), a multi-pitch climb in the Dolomites. DiGiulian, who stands 5’2” and sports long blonde hair and pink fingernail polish, works to dispel the idea that women who play outside are tomboys. Ashima Shiraishi, often outfitted in bright, patterned leggings made by her mom, also belies this idea. On March 22, 2016, at Mt. Hiei, Japan, Shiraishi, became the first woman, and youngest person (then 14), to top out a V15 boulder problem with Horizon (above). Then, in February 2017, after seven days of projecting, Margo Hayes made sport-climbing history when she clipped the chains on La Rambla (5.15a), becoming the first female to climb the grade.

[Ed. Since this story ran in our September print edition, Anak Verhouven put up a 5.15a first ascent, and Angy Eiter became the first woman to climb 5.15b!]

Only a hundred years ago, women were fighting for the right to vote. And while we’re currently experiencing political turmoil over women’s rights—among many other issues—in our country, there’s no denying we’ve come a long way. Today’s crushers like Alex Puccio, Emily Harrington, Paige Claassen, Hazel Findlay, Nina Williams, Michaela Kiersch, and so many more will continue to push the limits of what’s possible for women. If we’ve come this far in a hundred years, what will the next hundred bring?

Megan Walsh is a climber/writer in Salt Lake City. She loves exploring routes in Utah and beyond, but is even more stoked about furthering the progress of women in the outdoors.

The post A Consolidated History of Women’s Climbing Achievements appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

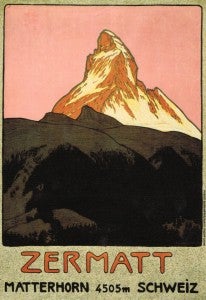

157 years ago, today, the Matterhorn saw its first ascent. To celebrate that fact, we present 10 fun facts about Europe’s most famous summit.

The post 10 Things You May Not Know About the Matterhorn appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

1. At 4,478 meters (14,692 feet), the Matterhorn is only Western Europe’s 12th-highest peak, but it is taller than Mt. Whitney, the highest summit in the Lower 48 of the U.S., by about 187 feet.

2. The Matterhorn straddles two countries, Switzerland and Italy, and has three common names. The German name Matterhorn derives from the words for “meadow” and “peak.” The Italian name, Cervino, and French, Cervin, likely originated with the Latin word for forest, silva, though some believe it comes from the Italian and French words for “deer.”

3. The first ascent on July 14, 1865, from the Swiss side of the mountain, ended a race that lasted nearly a decade and came down to the wire, with rivals on the Italian side poised only 1,250 feet below the top when Edward Whymper and Michel Croz first reached the summit. In order to ensure his rivals knew they were beaten, Whymper rather unsportingly shouted at the Italian team from the top and hurled rocks to make a clatter. “The Italians turned and fled,” Whymper wrote in his famed book Scrambles Amongst the Alps.

4. The glorious victory was marred when, during the descent, four of the seven climbers in the summit party fell to their deaths—a trend that continues to this day. The remaining three, including Whymper, likely would have fallen as well if the rope linking the men had not broken.

5. The second route up the Matterhorn, the Lion Ridge from Italy, was completed just three days after the first, on July 17, 1865.

6. Since the first ascent, more than 500 people have died while climbing or descending the Matterhorn—an average of three to four per year.

Watch stunning drone footage along the Matternhorn’s ridges in this video:

7. About 3,000 people summit the Matterhorn annually. However, starting this year, by reducing the size of the hut at the base of the most popular route, the Hörnli Ridge, and eliminating camping outside the hut, Swiss officials hope to slash the number of climbers by as much as one-third and reduce crowding on the mountain. About 80 percent of Matterhorn climbers are either guides or clients.

8. Both a railway and a cable car to the summit of the Matterhorn have been proposed. The latter, a tramway from the Italian town of Breuil-Cervinia, was proposed in 1950 but scuttled after tens of thousands of people protested to the Italian government.

9. Emil Cardinaux’s striking poster of the Matterhorn, designed as a card in 1903 and printed as a tourism poster for Zermatt in 1908, is considered the first modern travel poster and a landmark of 20th-century design.

10. In 2019, after an uptick in rockfall related deaths, there was a (brief) discussion about closing the mountain to climbers after an anonymous guide told a Swiss newspaper that climate change had made it increasingly unstable and dangerous.

The post 10 Things You May Not Know About the Matterhorn appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Just who climbs a route first is nuanced, and with big money at stake the lines between success and failure have gotten fuzzier.

The post Who Did It First? Style, Grades and Dispute in First Ascents appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Climbing grades don’t matter. You, me, us—we should just climb because it feels right or we’re trying to impress a girl…or a guy. Whatever comes first. Don’t judge. An unnatural focus on grades or definitions is to miss the whole point of climbing—freedom, travel, experience, intensity, overcoming boundaries. We all hate the grade police. Just get up the thing, right?

Not really. That’s half of the story. We, the pluralis majestatis, were in the Olympics, and companies far and wide took notice, with marketing budgets and opportunities for sponsorship following suit. With gobs of money pouring into our sport (Coke is sponsoring athletes now) comes the necessity for athletes to promote those products. In order for those athletes to get attention, they climb new and exciting things, FAs, FFAs, routes in exotic locations, light and fast ascents, naked ascents, and so on. Getting millions of eyeballs to read about climber X traveling around the world to send 5.7s is impossible; of course, that’s rad—no, really, climbing 5.7 is awesome—but it doesn’t make headlines. All good and fine thus far, and we shouldn’t judge.

And yet news abounds daily about claims of a certain type of ascent. A typical email—”Me and my team just climbed “x” in “x” style,” and so a claim is made. More often than you would think, the claim is inaccurate.

Climbs are tricks in a way, and since tricks can be performed with style, it’s only natural that climbing achievements are judged on improvements in style. In this context, style is not referring to how someone moves, but the way in which they chose to climb something. It’s a “game climbers play,” to cite Lito Tejada-Flores, and someone is always upping the ante. Alex Honnold’s free solo of Freerider on El Cap was one such improvement in style. Climbing doesn’t have objective measurements like line tape or a stop watch. We do have a rating system, but all climbers know body type is a huge factor. “Take!! I’m just too short for this move. It’s like 5.14 for me,” said everyone at some point.

Here’s a for instance: say you go out and climb the South Face of the Petit Grepon, in Estes Park, an eight pitch 5.8 on beautiful alpine granite, totally classic, and often crowded. A friend and I climbed the South Face a few years ago and we swapped pitches, as is normal on a typical trad outing. Yea, I’ve done that route, even though I didn’t lead every pitch. It was well below my ability on a gear route, so I didn’t feel the necessity of telling everyone, in conversation or whatever, that I had led half the pitches. No bounds nor speed record nor any record of any sort was broken that day, and it was perhaps all the better for that reason.

However, on ascents where performance levels are raised, collectively or individually, and they are reported upon, the stakes become higher, and it does matter. Climbing a 20-pitch 5.13 gear route and leading every pitch is exponentially harder than doing it with a partner and swapping leads.

In particular, magazines see a lot of incorrect reporting on the nuances between team ascents, free ascents, and individual ascents, among others. It likely comes from an over-eagerness to do something “first,” with a little bit of market pressure thrown in for good measure. Regardless, here’s some provisional thoughts, nothing in stone, and largely applicable to big wall rock climbing where the stakes are high. Let’s start with the simple stuff, then get more complex.

Individual ascents should be claimed when the climber leads all pitches, without falling.

Team ascents send the rig, but “swap leads.” This is the most common form of hard free ascents and first free ascents. In 2015, Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson sent the Dawn Wall as a team ascent and free ascent, since they swapped pitches; however, each sent the crux pitches. In 2016, Adam Ondra climbed every pitch himself, which amounts to the first individual ascent and second free ascent. Could Tommy and Kevin have each made the first and second individual ascents?—yes, of course. They just didn’t. Jorgensen wrote of Ondra’s ascent: “For Tommy and I, the question was whether it was even possible. We left lots of room to improve the style and Adam did just that!” Ondra’s ascent was an improvement in style, and arguably, in difficulty; however, having the vision and dedication to see the route, clean it and work it over years is more difficult in my estimation.

What about first female ascents (FFAs) in a mixed team? Can an FFA be claimed in a team ascent?

Single push ascents, as opposed to multi-day, refer to a climb being done in a single push, either by team or an individual, regardless if they have rehearsed it before. For instance, if you start climbing and then top out, without hitting the dirt to party on a rest day, then it’s a single push ascent. Lynn Hill was aware of this, and so, after her 1993, four-day team ascent of the Nose, she returned the next year to plant her flag with a single push (23 hours), leading every pitch herself—the first individual free ascent of the Nose. She wanted to do it in a better style. Ante up gents—“It goes, boys,” said Hill.

If you didn’t rehearse the route, then it’s a ground-up single push ascent. Assuming you didn’t onsight every pitch, did you pull gear on rappel?…since to properly claim a single-pitch trad send you can’t have pre-placed gear. The same should apply for big walls, right? It gets complicated. Did you stash food and gear up high? Did you have big-wall porters? Does that change anything?

Ok, down the rabbit hole some more. Say you have a 10-pitch project, and, over the course of the last five years, you’ve led every pitch. Maybe the first year you led pitches, 1-3, 7 and 9, and then on year five you led 4, 5, 6, 8 and 10. Can you claim the first free individual ascent?

Back to the Nose on El Cap for context…in 1998 Scott Burke nearly freed the Nose, an attempt that took 12 days, and he top-roped the Great Roof pitch because of impending storms. Tommy and Beth made a team ascent in 2005, and then Tommy made an individual free ascent in the same year, leading every pitch himself, in a single push, in 12 hours. Technically, in 2005, that means the only people to have sent the Nose individually were Lynn and Tommy.

I could easily keep going with distinctions—such as variation pitches—or take up the idea that naked, chalkless free soloing is the logical culmination of Royal Robbin’s “clean climbing” revolution, but I won’t. People ask how Honnold can be outdone—well there it is. Chalk and rubber are still quasi-technologies.

Style matters, and style informs difficulty, and we need to be clear about who did what and how. Since style is progressive, honesty is paramount.

For the majority of climbers, these distinctions don’t matter, but for those of us reporting on them, it does. As climbs are touted with increasing pressure from all parties to do something unique and singular, gone are the Warren Harding days of getting up the thing…unfortunately.

The post Who Did It First? Style, Grades and Dispute in First Ascents appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Watch one of the world’s best rock climbers choose his goals, deal with setbacks, and insist on progress.

The post Age of Ondra (Part III) appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Adam Ondra goes to Western Canada to try to flash Honour and Glory (5.15a)—an effort captured in Age of Ondra Part Two—but he fails. So he turns his attention to two 5.15b’s. His first objective is Fight Club, one of Canada’s toughest routes. Though it took Alex Megos five days to complete the first ascent, Ondra, in maniacal Ondra fashion, decides to try to send it in just one day.

Then he shifts his attention to a new project: a short, vertical climb that initially seems almost as uninspiring as it is featureless. Ondra admits that the climb is “definitely weird,” in part because all the holds seem to be facing the wrong way. Ondra calls it a V10 boulder problem up to the crux, which becomes even more heinous once he breaks off an important crimp. But it’s all about the complexity of the moves for him.

Will Ondra out-beta flat concrete? Or will he fail yet again? How does the world’s best climber cope with setbacks and doubt?

The post Age of Ondra (Part III) appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Part III of Reel Rock's "Age of Ondra" asks how one of the world’s best rock climbers chooses his goals, deals with setbacks, and insists on progress.

The post Failure is Always an Option: Watch Adam Ondra Battle 5.15b’s in Canada appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

“Age of Ondra” is available to all Outside+ members, part of an extensive library of climbing and adventure sport films found in the Outside App. Watch the full film, or download the app here.

Part One of Reel Rock’s “Age of Ondra” follows Adam Ondra from his early years to his FA of Silence (5.15d). Part Two takes us through Canada, Spain, and France as he tries to flash a 5.15a. Part Three picks up with Adam in Canada, after his failed flash attempt of Honour and Glory (5.15a), and focuses on his battles against two 5.15b’s.

His first objective is Fight Club, one of Canada’s toughest routes. Though it took Alex Megos five days to complete the first ascent, Ondra, in maniacal Ondra fashion, decides to try to send it in just one day.

His vision is impressive. Ondra takes his time trying to dial in each move, then attempts the climb again and again, tweaking his beta as he goes. (Spoiler alert: the insane drop knee does not turn out to be the most difficult bit). We’re with him as he carefully inspects thumb-catches and tiny three-finger pinches. We’re with him, too, as he doubts himself.

“Failure is part of climbing,” he says, “and it’s part of every climbing progression. Because failure is how you learn.”

After Fight Club, Ondra shifts his attention to a new project: a short, vertical 5.15b that initially seems almost as uninspiring as it is featureless. Ondra admits that the climb is “definitely weird,” in part because all the holds seem to be facing the wrong way. Ondra calls it a V10 boulder problem up to the crux, which becomes even more heinous once he breaks off an important crimp. But it’s all about the complexity of the moves for him.

Age of Ondra Part Three is a masterclass—an opportunity to watch an elite athlete leverage beta in all its minutiae to achieve his goals. Will Ondra out-beta flat concrete? Or will he fail yet again? How does the world’s best climber cope with setbacks and doubt?

Watch Age of Ondra Part Three.

The post Failure is Always an Option: Watch Adam Ondra Battle 5.15b’s in Canada appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

According to Niky Ceria, “The ideal line [is located] not too far from the water but also not too close to it.”

The post Video: The Search for the Best (and Hardest) Boulders in Italy appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

After graduating from high school in 2012, Niky Ceria travelled extensively for many years, repeating some of the world’s hardest classics, including numerous V15s, while also putting up tall first ascents in West Virginia and Australia and many places in between. Lately, however, he’s been focusing on undeveloped boulders near his home in Northwest Italy, many of which are found in the narrow river valleys of the foothills of the Alps and are featured in his new short film, The Riversider, which you can find below.

“I had the luck to live the entire process from A to Z on these boulders,” he told Climbing, first “visualizing the moves, the falls, the holds,” and finally, “after many sessions and lots of doubt,” climbing them clean.

One of the most fascinating facts about the particular boulders featured in the film, Ceria said, is that both their quality and difficulty is influenced by their distance from the river.

“The ideal line [is located] not too far from the water but also not too close to it,” he told Climbing. The rock should get “enough water to be smooth and solid, but not so much that it’s polished.”

When you’re looking only for boulders in this sweet spot, he adds, it reduces your chances of finding a king line. “But when it does happen, everything is magical. The rock has a very good and balanced texture.”

Naturally “The Riversider” is full of king lines.

The post Video: The Search for the Best (and Hardest) Boulders in Italy appeared first on Climbing.

]]>