From the state with the most fatalities, to the most common injury, preview some fast stats from the 2025 ‘Accidents in North American Climbing’

The post 9 Interesting Stats From 210 Climbing Accidents Last Year appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Nothing teaches you a lesson like making a mistake yourself. The next best thing, however, is reading about other climbers’ mistakes in Accidents in North American Climbing (ANAC), published annually by the American Alpine Club. Learning from the accidents of others is a valuable way to improve your systems, dial your safety practices, and avoid complacency.

Before diving into the accidents, the 2025 ANAC opens with valuable insights on making your next rappel safer. But the most fascinating story this year investigates the role of human error in accidents. Climber and researcher Dr. Valerie Karr searched for themes in ANACs from 2005 through 2024. In her surveying, she found the six most common ways human error leads to accidents. Climbing will also be publishing a story specifically related to Dr. Karr’s insights soon.

ANAC 2025 (Volume 13, No. 3, Issue 78) is now available for pre-order, with the official release in early October. Here are nine surprising takeaways from the report.

1. 2024 and 2023 were the highest fatality years since the 1950s in the United States.

Since the American Alpine Club first started soliciting accident reports some 75 years ago, between 10 and 43 climber deaths occurred per year. From 2022 to 2023, fatalities in the U.S. surged by 22% to a total of 51. In 2024, 49 total fatalities occurred in the U.S., the second highest number since the AAC started keeping records.

It was also a high year for climber injuries in the U.S., with 174 reported injuries, 15% more than 2023. This was also the second highest injury count in the U.S. since AAC records begin. Total accidents were also high, with 190 reported in the U.S., the second highest number since the 1950s.

While the reported incident volume is always higher in the U.S., our neighbors to the north had a more moderate year in 2024. The 2025 ANAC documents 20 total accidents from Canada (down 35% from 2023), 25 injuries (down 32%), and nine fatalities (up 23%) in 2024.

2. Before you blame “gym to crag” on rising incident rates, consider who got into more accidents.

Some climbers like to grumble about novice climbers who don’t know what they’re doing, whether they’re new to the sport or making the transition from gym to crag. But in 2024, expert climbers sustained far more accidents than beginners. While the experience level of a large volume of climbers involved in accidents remains unknown, we do know that 33 expert climbers got into accidents last year, while only six beginners and two intermediate climbers had accidents.

3. By far, California saw the most accidents and injuries reported in 2024.

ANAC uses geographic districts that include Canadian provinces (e.g., Alberta), Canadian territories (e.g. the Yukon and Northwest), U.S. regions that group together states with lower data thresholds (e.g., the Southeast), and U.S. states that are major climbing destinations (e.g., Colorado).

Unsurprisingly, California gets its own geographic district—and sees a lot of action. In the last calendar year, climbers in California reported by far the most accidents and injuries of any geographic district. In 2024, 40 climbing accidents occurred in California, followed by Colorado (28) and Washington (26). Thirty-four of those accidents involved injuries; runner-up districts for injuries across North America include the U.S. Northeast (26), and the state of Washington (24).

This brings California’s total accident count since 1951 to 1,798—second only to Washington, which has 2,134 reported accidents in the books.

4. But California did not see the highest fatality rate of 2024.

In 2024, Washington and Colorado both experienced 11 fatalities, the most of any other district. California accidents led to 10 deaths. This brings both Washington and California to a total of 378 reported climbing fatalities since 1951. The Colorado climbing community has experienced 295 deaths to date.

5. More accidents struck on the ascent than the descent.

Rappelling gets a bad, well, rap. But of all the accidents reported across North America in 2024, 100 occurred while climbers were ascending. Compare that with 46 accidents sustained during the descent. This trend is on par with historical data. (Note that with 46 of the 210 accidents, it was unknown whether problems arose on the way up or down, and 11 accidents also occurred on neither the ascent or descent).

6. The most common injury of 2024? Lower extremity fractures.

Those pesky ledges, nasty ground falls, and more hazards of the hobby led to 30 lower extremity fractures among climbers last year. Historically, lower extremity fracture has ranked ninth in terms of most prevalent injury. But the AAC only began breaking out fractures by location in 2021, and fractures in general have dominated climber-related injuries since the records begin for this datapoint in 1984.

The next most common injuries were hypothermia (17 cases in 2024), and head injuries/traumatic brain injuries (16 incidents in 2024).

7. Alpine climbing involved more accidents than any other discipline.

As usual, alpine climbing/mountaineering led to more accidents than any other type of climbing.

In 2024, 71 accidents occurred on alpine-style climbs. The second most accident-prone discipline of 2024? Trad climbing, with 52 total accidents. Sport climbing comes in third, with 35 accidents last year. Other categories include ice/mixed climbing, big wall climbing, bouldering, toproping, free soloing, and ski mountaineering.

But before you make assumptions about alpine climbing or trad climbing being more dangerous than, say, ice climbing or free soloing, keep in mind that these aren’t accident rates, only accident totals. The higher accident volume might be indicative of the popularity of each discipline. While nine people had accidents free soloing or deep water soloing in 2024, for example, the accident rate might still be quite high considering how few people climb ropeless.

8. A lot of climbers got lost last year.

After falling while rock climbing, the second leading cause of accidents in 2024 was becoming lost or stranded. With a total of 31 accidents involving getting stuck or off track, this is a good reminder to us all to download a navigation app, bring along a satellite comms device, and tell someone where we’re going and when we expect to return. Oh, and brush up on those self-rescue skills!

9. Male climbers got in a lot more accidents than female climbers.

Last year—and historically—men experienced more accidents than women. While this may lead you to draw some conclusions, keep in mind that this data doesn’t take into account the total numbers of men vs. women climbing. That said, 134 accidents involving men, compared to 40 accidents involving women in 2024, represents a pretty big gender gap.

Whether it’s about who’s actually climbing—or something else—we also saw a similar trend in our 2024 Climbers We Lost. Among 38 fatalities in our community, only one person on our list was a woman.

The post 9 Interesting Stats From 210 Climbing Accidents Last Year appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

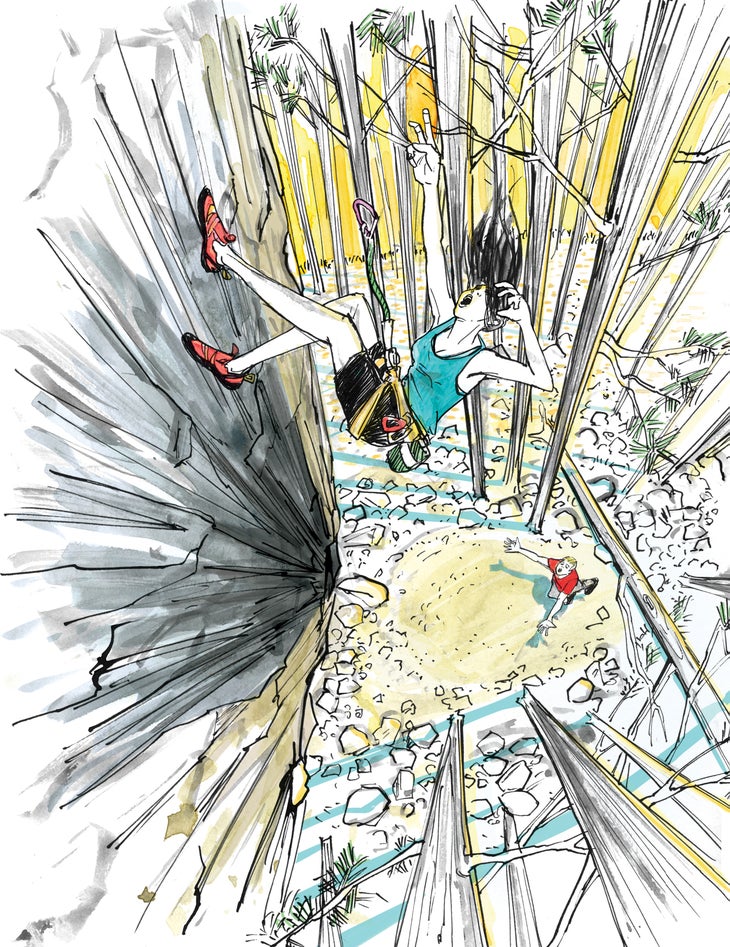

We spot boulder problems. Sometimes we spot climbers before they clip their first piece of pro. Now imagine spotting a climber falling 60 feet.

The post A Mis-clipped Anchor Leads to a 60-foot Grounder—And a Life Saving Spot appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Climber: Douglas Kern

Location: Staunton State Park, Colorado

Date: August 23, 2014

The Scene

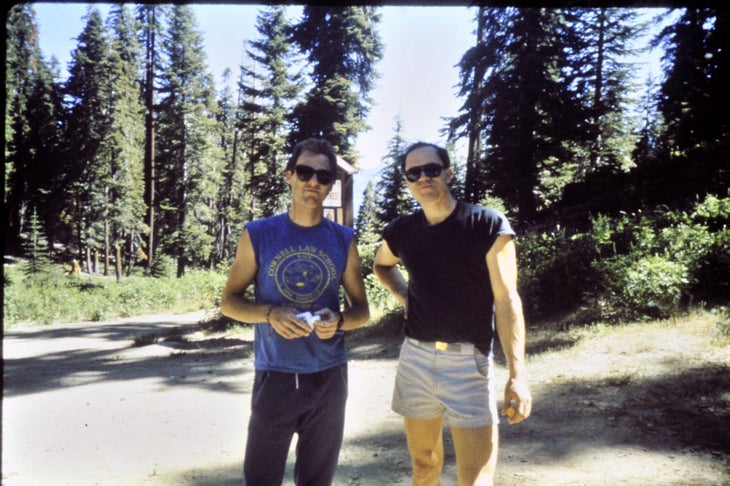

Asha Nanda, 21, had been introduced to climbing at a Christian leadership program in the Adirondacks. During a trip to Colorado, she and several other climbers hiked up to the Tan Corridor, high in a forested gully in Colorado’s newest state park. Douglas Kern, then 25, had just met Nanda the day before; he was one of the more experienced climbers in the group. In the afternoon, Kern led Reef On It! (5.10-), a vertical, seven-bolt sport climb. He left a rope running through quickdraws clipped to the anchors so the rest of the group could enjoy a toprope.

Nanda was the last climber to do the route. Before starting, she borrowed one of Kern’s thin Dyneema slings and girth-hitched it to her harness; she planned to use this sling to clip in at the anchor, thread the rope, and then rappel. Kern’s slings were rigged as alpine draws, with a wrap of tape cinching the sling tight next to one of the carabiners so it wouldn’t shift around.

When Nanda reached the top of the route, 60 feet above the ground, she clipped one of the anchor chains with the sling hitched to her harness. Although she was new to outdoor sport climbing, she had rehearsed anchor cleaning in a gym, and had run through the steps with one of her climbing partners earlier that day. She leaned back and fully weighted the sling connecting her to the anchor to test it, then yelled “off belay” and began untying the figure eight at her harness, preparing to thread the rope through the anchor. “I was very focused on checking and rechecking each step, and this process took approximately two to three minutes,” she says. Suddenly she heard a scream and saw the rope falling in loops below her. Then she realized the scream was her own and she was plummeting through the air.

The Response

Unbeknownst to Nanda, the single sling she’d used to clip the anchor had been compromised, either before she hitched it to her harness or while she was climbing. A loop of the sling must have slipped through the gate of the carabiner that was taped at one end, so now two strands of sling were clipped through the same biner. Although difficult to visualize, this creates a very dangerous situation similar to cross-clipping two loops of a daisy chain—in effect, when Nanda weighted the sling, only the wrap of tape around it secured her to the anchor. The beefy climber’s tape held her weight until she had completely untied and only failed then, leaving the carabiner still clipped to the anchor bolt and the now-useless sling hitched to her harness. The tape fluttered to the ground after the falling climber.

Startled by Nanda’s scream, her belayer, Julie MacCready looked up to see her plunging toward the ground, the rope looping below her. There was nothing she could do to stop her. Kern had just lowered off a nearby climb and was walking down the gully when he heard Nanda yell. Amazingly, he had no doubts about what he would do next.

“I once saw a dude fall in the Adirondacks when we were ice climbing,” he explains. “He fell 20 feet and landed on the ground right next to me. I said to myself right then, ‘If I ever see that again, I’m going to catch the person.’”

Nanda weighs about 125 pounds, and Kern is 6’ 2” and weighs 190 pounds. He had lifted weights throughout high school and college and practiced karate. As he saw her fall, he vividly remembers thinking, “She’s so small, I’ll catch her—it’ll be no problem. I’m going to stop this fall.”

No more than two seconds elapsed between Nanda’s scream and her impact, but Kern remembers that she seemed to be falling “really slowly.” He stood at the base of Reef On It!, planted his feet, and stuck his arms out in front of him, like a man about to catch a medicine ball in the gym. Nanda fell into his arms and slammed onto his chest, then ricocheted onto the ground, where she bounced “a foot or two” off a single narrow strip of dirt amid a sea of boulders and scree.

Flat on her back, Nanda looked up at her friends and said, “What happened?”

Both Kern and Jennifer Lee, another friend in the party, had wilderness first aid training and began to assess Nanda’s condition. MacCready called 911, and another climber ran down the mountain to direct rescuers to the scene. Despite the horrendous fall, Kern and Lee could find no injuries, but when rescuers arrived she was shaking and her blood pressure was falling. Rescuers carried her out of the gully and called for a chopper. She arrived at the hospital two hours after the fall. After seven hours of tests, Nanda was released—every test and scan had come up negative.

Nanda quickly returned to climbing, but says her accident taught her several crucial lessons, including to use her own gear, avoid taped “alpine draws,” and always back up her anchor. Also, she says, “If you’re new to climbing, advance cautiously and with respect to the risks.” She now lives near the Red River Gorge in Kentucky, studying nursing and volunteering for the local fire department.

While Kern’s actions undoubtedly were heroic, he was lucky too. The impact of Nanda’s fall could have seriously injured him or even killed them both. The great difference in the two climbers’ statures enabled him to absorb the blow. Kern also had prepared himself mentally for this day after witnessing a previous groundfall, and his self-confidence and desire to succeed boosted his ability to stand tall.

Kern, who is now living in New Zealand and working for an arborist, credits God for helping him save Nanda: “I think He wanted that girl alive.” Asked if he would do the same thing if he witnessed another falling climber, Kern says, “For sure! If I got a bruise, big deal. She didn’t die. Of course I’d do it again.”

Survival Tip: Give Accurate Directions

Write down or review the information you want to communicate before calling rescuers, including your location (without relying on route names, if possible), your name and number, and the patient’s status. “Rescues are often delayed by panicky callers that are unable to give a location to rescuers,” Simon explains.

The post A Mis-clipped Anchor Leads to a 60-foot Grounder—And a Life Saving Spot appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

How many pitches do you climb in a year? For many of our readers it's probably close to 1,000. If you make a critical error one out of a thousand times, the outlook is bleak.

The post The Checklist That Could Save Your Life appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

The impact was close enough that it triggered my fight-or-flight response. I’d heard a climber yell “Fuck!” and then he hit the gym floor behind me. It was 9:30 on a Tuesday night. Recovering from an injury, I’d come by to test my shoulder with a few easy laps on the auto-belay before bed. It had been quiet at the gym, with only a handful of people in the back room where I was climbing. I didn’t turn around. I knew it was bad, and I was afraid to look. Flight won. I ran across the gym screaming “Help!” until I reached the manager at the front desk. He went to the injured climber, and I called 9-1-1.

“Is he conscious?” they asked.

And: “Approximately how old is he?”

I couldn’t answer any of the dispatcher’s questions. I only knew that he was male and needed medical attention. I returned to the back room of the gym, afraid of what gore I might see. It’s strange to say that I was relieved to see the climber merely writhing in pain and holding his lower back. He was alive. There was no blood. No protruding bones. He was conscious. The gym manager was tending to him, so the dispatcher instructed me to wait outside to flag down the ambulance.

After the professionals arrived, I went back inside to retrieve my belongings. It felt surreal to see climbers carrying on as usual in the front room and arriving gym members checking in at the front desk. I still felt nauseous from the adrenaline when I got home.

I think it’s a common instinct. After you’re present for a climbing accident, you feel an urge to do something about it. You can’t help the person who’s been hurt—it’s too late for that—so you turn to warning others.

Earlier in the summer, we received an email from a former Climbing intern imploring us to reshare our article about cleaning sport anchors. He’d been climbing in Clear Creek Canyon above Golden, Colorado, when an 18-year-old girl had died nearby due to a misunderstanding about whether she would rappel or lower. On his urging, we updated the article to emphasize communication and re-published the piece.

I don’t know what caused the gym accident—it happened behind me, out of my view. All I heard was the impact, and all I saw was the aftermath. It would be irresponsible to speculate about what went down, and so I can’t tell you what to do or not to do.

What I do know is that most climbing accidents are preventable.

In the excellent snow-safety book Staying Alive in Avalanche Terrain, the author Bruce Tremper, the now-former director of Forest Service Utah Avalanche Center, presents a hypothetical actuarial table showing your odds of dying in an avalanche assuming the following:

- You travel in avalanche terrain 100 days per year

- You cross 10 avalanche slopes per day

- The snow is stable enough to cross on 95 percent of the slopes

- You are killed in the tenth avalanche you trigger

The table concludes that an ignorant person with no avalanche skills will be dead in two months. With better judgement, avoiding avalanches on 99 percent of the slopes extends your lifespan to one year. At 99.9 percent, you’ve got 10 years. And only at 99.99 percent do you get a comfortable 100 years.

To simplify things, let me translate these numbers into climbing terms. How many pitches do you climb in a year, including gym routes? I imagine for many of our readers it’s over 100, and probably closer to 1,000-plus. If you make a critical error one out of a thousand times, the outlook is bleak.

Tremper goes on to write: “Because humans regularly make mistakes, we can’t rely on our individual knowledge or prowess to keep us alive. Instead, avalanche professionals operate in a SYSTEM, which I capitalize here because it’s so important. The pros travel a well-trodden path of proper training, mentorship, procedures, rituals, and step-by-step decision-making. And to further push the arrow toward the top of the actuarial chart, they know that they will inevitably make mistakes: so they always follow safe travel ritual and practice rescue techniques.”

There’s not much in there that couldn’t apply to climbing. Our sport is easily as dangerous as backcountry snow travel in terms of the consequences of a mistake—and perhaps even more so, given the constant, and very predictable, force of gravity.

So have a process for checking critical safety components in your climbing system and do it the same way every single time you climb.

I certainly know people who skip the safety check before climbing, who approach it all with a cavalier attitude. I bet you do too. I’ve even had a friend get scolded by a crusty partner for asking to check his knot. It’s often the most experienced climbers who feel like they’re above basic safety protocol, never mind that there are plenty of examples of elite climbers getting hurt due to simple mistakes.

So again: Have a process.

However you do it, the point is that having a step-by-step process will force you to be conscious of your own and your partner’s safety. When you ask your partner to check your knot, the point is just to check it—to get both of you to inspect the knot. I bet in most cases, when you grab your figure eight and present it to your belayer, you’ll catch a problem before they do. But you won’t catch the error if you don’t ask your partner to check the knot in the first place. So always:

- Check your knot and show it to your partner

- Show your partner that your belay device is loaded properly, and that your belay biner is locked and clipped to your belay loop in the proper orientation

- Discuss whether you’ll lowering or rappel before leaving the ground

- Confirm that you’re on belay before climbing

- Tug on your autobelay biner on your belay loop and check that the gate is locked before pulling on to the starting holds

- Use names with commands, but be aware that there could be another climber nearby with the same name as you or your partner

- Know how you’ll go in direct to an anchor before you get there, whether you’ll be bringing your partner up or cleaning and descending

- Tie knots in the end of your rappel/lowering rope

- If you see another climber doing something unsafe, help them

- Never assume anything when someone’s life depends on it

I hope the climber who fell behind me is OK. I hope I see him back in the gym in a few days with some bruises but no worse for the wear. I may never find out what happened to him or how he’s faring in the aftermath. All I can do is try to warn others—and remind myself—to be eternally cautious.

“Knot Good” was originally published as “The Process” in 2019.

Also Read:

- Brian Squire Sends the Dali Boulder in a Day

- The Horrors of the Gym Belay Test

- How Lynn Anderson Fired Off Eldorado Canyon’s Hardest, Scariest Trad Climbs—in a Single Day

The post The Checklist That Could Save Your Life appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

And how to prevent these simple mistakes.

The post The Perils of Plastic: Gym Climbing’s Most Common Accidents appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Cassie has been climbing for about six months, mainly toproping, but is beginning to dabble in the bouldering cave. Last week she climbed her first V2, and she was stoked. Upping the ante, she’s recently been throwing herself on a steep V3, which ends with a slightly dynamic move, a big left-hand bump to the finishing jug. Finally, she gets to the last move, though with a mild pump. Tasting success, she goes for it. But no dice. Off she comes from the top of the bouldering wall, careening sideways. Her left leg, stiff and extended, hits the mat first. She fractures her tibia and sprains her ankle.

Cassie is fictional, but her injury isn’t. In fact, according to estimates by industry insiders, this exact type of injury—of intermediate climbers injuring their legs or ankles while bouldering— accounts for 40 to 50 percent of all gym accidents.

Is there such a thing as safe climbing? No, there isn’t. There are too many variables and opportunities for human error, the cause of the vast majority of accidents.

“Safe,” one CEO of a major gym retailer told me, “is a four-letter word.” Rather, managers prefer the term “management of risk.”

In researching the most common types of gym accidents, I spoke with the owners and CEOs of some of the biggest gym companies in the U.S., and, as one might expect, their stories were similar. The following list ranks gym accidents (from top to bottom, and most common to least) as they are found in the three main sections of your gym: bouldering, toproping and lead-climbing areas.

Bouldering

Sprained ankles or wrists, broken bones and hyper-extended knees and elbows.

Because of its simplicity and immediacy, many beginner and intermediate climbers just start bouldering. But no one would arrive at a gymnastics facility and start doing front flips. Point being: true, you can just start bouldering, but if you’re new to the sport, you’re asking for it. According to one owner, “These accidents happen when climbers lose track of where the ground is.”

The harder you boulder, the more you will be exposed to moves that put you sideways or require you to jump or heel hook with your foot by your face. The good news: these accidents are largely preventable. I’ve been bouldering for 20 years with lots of highballs tossed in for good measure, and in that time I’ve only had one sprained ankle, about a dozen years ago.

First, learn how to place mats properly, if your gym uses them. Second, do proper dynamic stretches for your ankles and lower body for no shorter than 10 minutes. Even if you’re already “feeling warm” from leading or toproping, your soft tissue and ankle joints are not. Third, take your gym’s bouldering class, and if the instructor doesn’t talk about body awareness, ask about it. The best way to prevent bouldering injuries is to start falling. Body awareness is crucial, and falling is an art. Unless you pop off completely unexpectedly, which is rare, your body has ruminations that falling is imminent, and when that happens, you should be thinking about how you want to land; i.e., it should always be softly. See also the bouldering tips in “Errant Spot and a Shattered Leg” for a lengthier treatment of the art of falling.

Toproping

Improperly tied knots by experienced climbers; improper ATC threading.

Injuries from unfinished or mis-tied knots are commonly caused by experienced climbers who let their guard down. As common sense would have it, newer climbers are stricter about using proper protocols (verbal commands such as “Climbing,” “Climb on,” etc.) than experienced climbers, who might have become lax. Prevention: never let your guard down, ever, regardless of your skill level. The stakes are just too high. Whatever commands you use doesn’t matter, what matters is that you are communicating with your belayer about what’s happening—before climbing or lowering—and that you have checked each other’s knots or devices. Good communication should also prevent another common accident: an improperly threaded ATC, where the rope is pinched through the device, but not clipped into a carabiner.

Outdoor crags are not immune, either. The majority of climbing accidents are user-generated: rappelling off the end of your rope, taking people off belay when they shouldn’t be, or just plain bad belaying. If everyone tied knots in the ends of their ropes and used proper verbal commands, my gut tells me that a large number of all climbing accidents would vanish overnight.

A second common accident in the toprope area of any gym is associated with auto-belays. One gym owner relayed the story of how a frequent auto-belay user got to the top of a wall before those around him yelled up to tell him he wasn’t clipped into anything. The auto-belays had been sent out for maintenance. Thankfully, the climber downclimbed and was safe. “You can’t imagine how often we see that,” the owner said. Now that most auto belays have a feature (such as a nylon tarp clipped to the wall and rope) to prevent individuals from simply climbing without being reminded to clip in, these accidents are becoming more infrequent. However, each owner stressed that these accidents do occur, despite safety measures, and that auto-belay accidents can be severe.

Lead belaying

Botched clips, smashing into the belayer, weight differences.

Every gym has its own protocols for lead belaying, and you should stick to them. As a lead belayer, you should always anticipate a fall and never stand directly below the lead climber. As the leader climbs, move positions to ensure that you and the leader are out of each other’s way in case of a fall. However, even if you (as belayer) are out of the way, a big weight difference between the leader and belayer can have deleterious effects, such as the lead climber smashing into the belayer; according to all sources, this was the most common type of lead climbing accident. If you are belaying someone much heavier than you, look for anchor points on the ground (assuming the gym has them), or, when belaying, beware of extra slack in the system, which would pull you off the ground unnecessarily. When in doubt, ask someone in your gym for the official protocols.

A common accident is hitting the deck as a result of having too much slack out. Often, a beginning leader may try to clip too early, and bite out as many as three loops of rope from an insecure position. If this is at the second or third clip, the leader can hit the ground as a result of excessive slack in the system. Most gym routes have “clipping holds,” which means the routesetter puts a decent hold on the route to clip from. Use them. Rather than make the clip two moves too early, it’s often easier to clip where you are supposed to, which is often around your waist, or slightly above. Don’t attempt to clip unless you are relaxed and confident you can hold that position for 10 or more seconds.

This article appeared in Rock and Ice issue #251 and has been updated where relevant.

Also Read:

- Weekend Whipper: Be Mindful of the Polished Classics!

- For Safety’s Sake Don’t Do This: Saw Through Someone Else’s Rope

- The Lost Art of the Pre-Wireless Rest Day

The post The Perils of Plastic: Gym Climbing’s Most Common Accidents appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Some blame the weather, while others point the finger at the economic trends that are shaping Himalayan mountaineering.

The post Why Did So Many Climbers Die on Mount Everest This Year? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

The 2023 spring climbing season on Mount Everest has come to an unofficial end, with monsoons and high winds returning to Khumbu Valley in recent days and closing the window of calm weather on the world’s highest peak. Climbers and expedition leaders must now take stock of what is one of the most chaotic and deadly years in the mountain’s history.

As of this story’s publishing, 12 climbers are dead and five are still missing. The current death toll is the fourth-highest in Everest history, (only 2015, 1996, and 2014 had more, with 13, 15 and 16 deaths respectively). If the five missing people are declared dead, then 2023 will have the unhappy distinction as the deadliest year for climbers on the peak at 17. In 2015, a massive earthquake triggered an avalanche that swept through Base Camp—conflicting reports peg the final death count at anywhere from 19 to 24 people. Not all of those killed were climbers, however, as the slide killed camp workers and expedition staff as well.

Climbers over 50 years old took a heavy toll this season. On May 1, American Jonathan Sugarman, 69, climbing with American operator International Mountain Guides (IMG), died at Camp II. On May 18, Chinese climber Xuebin Chen, 52, died near the South Summit with Nepali operator 8K Expeditions. And on May 24, Canadian Dr. Pieter Swart, 63, died after turning back at the South Col with Madison Mountaineering. Garrett Madison, owner of the guiding company, told Outside that Swart died suddenly. “He died of a rapid onset lung infection/pulmonary edema,” Madison wrote in a message. “We are going to make a statement soon about it. Been very focused on getting his body down and communicating everything with his family.”

It appears that altitude sickness may have contributed to several other deaths this season. On May 16, Phurba Sherpa, who was part of the Nepal Army mountain clean-up campaign, died near Yellow Band above Camp III. Another Nepali climber, Ang Kami Sherpa, working as kitchen staff for outfitter Peak Promotion, died at Camp II when he collapsed near the helicopter pad.

Moldovan climber Victor Brinza died on May 17 at the South Col while climbing with Nepali operator Himalayan Traverse Adventure. On May 20, Malaysian Ag Askandar Bin Ampuan Yaacub climbed above South Summit, then became ill and died. He was with Nepali operator Pioneer Adventures. Australian Jason Bernard Kennison, 40, died on May 21 near the Balcony while climbing with Asian Trekking. Indian Suzanne Leopoldina Jesus, 59, intended to climb Everest but left Base Camp ill and died in Lukla on May 18. She became sick at camp, and according to multiple reports, refused to go lower for help for several days. Three of the 13 deaths occurred simultaneously: On April 12, a section of the Khumbu Icefall collapsed, burying Tenjing Sherpa, Lakpa Sherpa, and Badure Sherpa under tons of ice. They were ferrying ropes and gear to put in the safety lines from Camp II to the summit, and their bodies have not been recovered.

According to The Himalayan Times, five climbers are still missing on the peak. Nepali climbers Ranjit Kumar Shah and Lakpa Nuru were ascending together when they disappeared. Hawari Bin Hashim of Malasia was attempting to become the first hearing-impaired climber from Malaysia to ascend Everest when he went missing after reaching the summit.

Hungarian climber Suhajda Szilard, who was attempting to scale Everest without supplemental oxygen, is presumed dead after climbers found him unresponsive near the summit. According to Explorersweb, an attempt to rescue him was called off on May 27 due to weather. Shrinivas Sainis Dattatraya of Singapore is also missing and presumed dead. Prior to disappearing, Dattatraya texted his wife saying that he was suffering from high-altitude cerebral edema (HACE), a deadly disorder that happens when a person travels to extreme altitudes without proper acclimatization. Dattatraya’s wife believes her husband will not be found, writing a memorial to her husband on Instagram. “He was 39, and in his glorious and rich life, he lived fearlessly and to the fullest. He explored the depth of the sea and scaled the greatest heights of the Earth.”

Frostbite and Rescues

In addition to deaths, mountaineers at Everest told me that climbers saw an uptick in cases of frostbite and calls for mid-mountain rescues this year. Some sources blamed this dynamic on the record number of foreign climbing permits issued by Nepal this year—478 foreign climbers received permits, and approximately 600 climbers reached the top.

Others pointed fingers at inexperienced guides and climber error. However, Nepal government officials and some other climbers say climate change created colder-than-normal conditions on the peak this year, and a tight weather window forced climbers onto the peak earlier than normal. Dr. Yuba Raj Khatiwada, the director of Nepal’s tourism department, told multiple outlets that climate change and the weather were to blame.

“Altogether this year we lost 17 people on the mountain this season—the main cause is the changing in the weather,” he told The Guardian. “This season the weather conditions were not favorable, it was very variable. Climate change is having a big impact in the mountains.”

The reports of colder weather are anecdotal, and Nepali authorities have yet to release temperature data backing up the claims. Chris Tomer of weather forecasting outfit Tomer Weather Solutions said the average temperature on the Everest summit varies from -10 to -20 degrees Fahrenheit during climbing season. Nabin Trital, managing director of guiding company Expedition Himalaya, said that the weather did feel different this year, notably colder than usual. “Compared to the previous years, we have experienced a lot of cases of frostbite. This year snowing occurred only in late March, which is why it was colder in the mountains like winter expeditions,” he said.

Guy Cotter, managing director of expedition company Adventure Consultants, echoed the sentiment. “It was a very cold season, the coldest my staff and I have ever experienced,” said Cotter, who has been climbing Everest since the early 1990s. “We had two Sherpas suffer from frostbite, which is the first time in 30 years that we have ever had any of our Sherpas suffer frostbite. Luckily one case was superficial, and the other may lose the end of a finger.”

Multiple sources told me that helicopter rescues were a daily occurrence on Everest this year. Cotter estimated the total number of flights to be around 200 from Base Camp to Camp II at 21,300 feet elevation. “The number of rescues was unprecedented,” he said.

Cotter did note that some of the flights were used to transport gear, and in some cases, even climbers to and from Camp II—a practice the Nepali government explicitly prohibits except for medical resources. “Climbers were regularly flying out from Camp II as opposed to facing the icefall,” Cotter said. “Helicopter activity over Base Camp is continuous from dawn to dusk every fine day.”

Why So Many Deaths?

Just three of the 12 confirmed deaths were related—the Sherpas who died due to falling ice—and the others were the result of sickness, exhaustion, falls, or climbers getting lost. Some mountaineers and government officials believe this was due to simple numbers—more people ventured onto Everest this year than any year in history. Ang Norbu Sherpa, president of the Nepal National Mountain Guide Association, told The Guardian that 478 permits was simply too many.

“The climbing pattern has changed, it used to be hardened climbers but now it is a lot of novice climbers who want to get to the summit of Everest,” he said.

Mountaineers I spoke to echoed his sentiment, telling me there was an uptick in inexperienced climbers working with low-cost expedition companies that offer bare-bones support. Garrett Madison, the founder of Madison Mountaineering, said some operators now take clients with no prior high-altitude experience onto the peak. “We require climbers to have successfully completed several big peaks before joining us for Everest, such as Aconcagua, Denali, Chimborazo, Cho Oyu, etc,” he said. “I’ve seen a trend where companies say, ‘No experience required [and that] anything is possible,’ and I don’t support that model.”

Phil Crampton, the founder of Kathmandu-based Altitude Junkies, said he’s seen some operators allow clients to push for the summit even after a guide has turned back due to sickness. Cotter says some of the deaths likely occurred when climbers encountered a problem—exhaustion or low oxygen levels—but they were working with an outfitter that did not have a backup plan. “The operators supporting those climbers still have a mindset that they are merely providing expedition services and not guiding these people and therefore feel no sense of responsibility for them,” he said.

Lukas Furtenbach, owner of Furtenbach Adventures, said many of the deaths were preventable. In his opinion, the fatalities were the result of poor planning for oxygen needs, and a lowering of general safety standards. “Apart from the three sherpas in the icefall and the IMG client who probably had a heart attack or stroke, I am convinced that all the other deaths could have been avoided by following safety standards and [having] sufficient oxygen supplies at all times,” he said. “[The deaths] all have a similar pattern.”

Caroline Pemberton, general manager and co-owner of guiding company Climbing the Seven Summits, had 44 clients safely reach the Everest summit. Pemberton believes there’s a different mindset between guiding companies—some view their operations as simply logistics operators for clients hoping to reach the summit, while other outfits are focused more on climber safety. “There’s a consumer misunderstanding of the options available on Everest,” she said.

Pemberton believes some clients pay a heavy price by working with untested operators that offer a lower price. “Sadly, people lose their lives in an effort to save $10,000. It appears that they do not anticipate that people who are not climbers are incapable of looking after themselves and cannot manage their energy and oxygen levels, and regularly collapse after the [summit] has been reached,” she says. “The incidents occur on the way down. People with little or no experience who book under-resourced expeditions are exposing themselves to huge risks.”

Few Solutions on the Horizon

The sources I spoke to did not feel that the government of Nepal would step in to enforce any changes on the mountain in the coming years. On other popular mountains, governments and agencies restrict who can climb a peak, and they fund full-time safety crews to assist with rescues. Adopting practices from other mountains like Alaska’s Denali or Argentina’s Aconcagua could save lives. On Denali, rangers are stationed on the peak throughout the season to help with rescues. A crew of rangers stationed at the South Col could provide similar support.

In previous years, Nepali officials have proposed experience requirements for Everest hopefuls applying for permits. China requires any Chinese citizen to have summited an 8,000-meter peak before attempting Everest from the Tibet side, though it does not impose a similar requirement for foreigners.

One proposed safety measure would allow helicopters to ferry fixed rope supplies—but not climbers—to Camp II, reducing the number of trips through the Khumbu Icefall for Sherpas. Another option would be to require every client and Sherpa to carry a GPS tracking device that would simplify search and rescue.

Limiting the number of climbing permits would could reduce crowds and make for fewer emergency situations overall, but that would also trim the revenue for the Nepali government, making it an unlikely move. Nepal does require climbers to undergo a medical examination prior to climbing the peak, but it’s unclear how effective or enforced it is.

Cotter told me that the climbers who flock to the peak each year would benefit from a shift in mindset. Rather than push for the summit at all costs, he said, mountaineers should take a conservative approach, and be prepared to turn back instead of pushing onward at all costs. “Most of us who have been in this game for a while have seen too many people pass away to forget this tragic and unsavory aspect of our sport,” he said. “It is as if people are interested only in the goal of having climbed Everest and not climbing Everest as a major achievement in their climbing career.”

This article was originally published on Outside Online.

Also read:

The post Why Did So Many Climbers Die on Mount Everest This Year? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

An ascender failure, a gear-stripping fall, a rappelling accident—Two Yosemite veterans analyze five Yosemite accidents and how they could have been prevented. (From 2017)

The post How Five Yosemite Climbing Accidents Could Have Been Prevented appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

The emergency pager screams to life, shattering the nonchalant atmosphere of the Yosemite Search and Rescue (YOSAR) site behind Camp 4: “All available SAR-siters needed for a rescue down-canyon. Climber fall. Please report to the SAR cache; Victor 3 is your contact.”

It’s 1:15 p.m. in Yosemite Valley, May 2016, when the call comes. We YOSAR members cook lunch together at our site. Wood-framed canvas cabins line a mostly dry creekbed, in front of the fire pit and behind the community slacklines. During Yosemite’s busy season, May through October, the nine of us are responsible for all wilderness emergencies, on-call 24 hours per day.

In Yosemite, according to the nonprofit Friends of YOSAR, there are over 200 rescues each year, ranging from a hiker spraining his ankle on Half Dome, to climbers marooned at a stuck rope on Royal Arches, to a climber fall halfway up El Capitan. Although YOSAR is here for climbers, and your local climbing area likely has a SAR team at the ready, you should never rely on us as your first line of defense. Each rescue requires time and resources, and can put SAR members’ lives at risk. Instead, avoid being in an accident in the first place. We should all be asking ourselves: Could many of these accidents have been prevented? What are their most common causes? And how can we learn from them to become safer, more competent climbers?

From what we’ve seen as a climbing guide for four years (Miranda), and two seasons on YOSAR partaking in over 75 rescues (Alexa), climbers can avoid most rescues. First, be prepared. (See “The 10 Multipitch Essentials,” below) Practice and know simple self-rescue techniques and safe climbing habits. Be honest about your abilities. And read accident reports to learn from others’ mistakes and to strengthen your ability to detect threatening patterns—Accidents in North American Mountaineering and your local SAR website are great resources.

In this article, we discuss five accidents in Yosemite, analyzing their causes to understand how they could have been prevented.

Serenity Crack (5.10d), Royal Arches, Off-route Rappel, Stuck Rope, Stranded

A party of three climbed the classic link-up “Serenity and Sons”—the three-pitch Serenity Crack (5.10d) into Sons of Yesterday, a six-pitch 5.10b. After a successful ascent, the trio began to rap Sons with two 70-meter ropes. The climbers skipped an intermediate station, a bolted belay on the first pitch of Sons, to try to reach the final anchor atop Serenity Crack. This forces the climber, once near the ends of her rope, to tension hard right along a blank face to avoid a dangerous pendulum around a large corner out left. Two of the climbers tensioned right and reached the anchors atop Serenity Crack. However, once the second arrived, clipped in direct, and removed his device from the rope, he let go of the rope and it swung back in line with the top anchor—and more importantly, out of reach.

The third climber, also the least experienced of the three, began the rappel. Near the bottom, he lost his footing, succumbed to the pendulum, and swung around the massive corner. Multiple such incidences have occurred at this location, sometimes injuring the party. Fortunately, this climber was unhurt. Once he’d stopped swinging, he decided to continue rapping—straight down to the nearest ledges where there was another anchor, separating himself from his party out of sight around the corner. He then pulled the ropes; however, the cords got stuck. Unable to extricate themselves, the climbers first called friends for a rescue, but they were hesitant to come due to afternoon rain and impending darkness (nice friends!). Later that evening, the trio contacted YOSAR.

Via phone, YOSAR instructed the third climber to fix one end of the rope, prusik up the other end, unstick the rope, then rap back to the ledge, unfix the rope, and ascend both strands up and around the corner to reunite with his friends. Due to his inexperience, the dark, and the rain, he was unwilling to fix the situation: He ascended only a couple feet up the rope before giving up (see illustration). The following morning, YOSAR arrived and found the climbers safe on the ground (the party had not called with an update). In the end, their friends had come to help a few hours before YOSAR.

Analysis and Prevention

Never let the rope linger out of reach once you clip into an anchor and go off rappel. You can thread one strand—the side with the knot—through the next anchor to set up for the next rap or clove-hitch a rope end to yourself or the anchor. This will prevent you from getting stranded and guide the top climber to you if you’re rapping through traversing or overhanging terrain.

Situational Awareness

Gather information beforehand for best methods of descent. Understand when it might be safer to use an intermediate anchor even though the ropes can reach one lower down—more short rappels might be safer than fewer long ones. Also, look at the anchors you’re attempting to reach and assess the angle you’re about to create with the ropes: Is it safe? Is it worth the risk? What would happen to you or your ropes if you took the swing?

Self-Rescue

The number-one factor preventing many climbers from initiating a self-rescue is fear. Practicing and mastering skills before getting off the ground is vital. The climber had never prusiked and didn’t feel comfortable learning in the dark and in the rain. Although YOSAR instructed him, he instead chose to spend a miserable night out. Self-rescue skills to master before leaving the ground:

- Escape the belay

- Ascend a rope with prusiks

- Buddy rappel.

The Nose (VI 5.9 C2), El Capitan, 200-Foot Fall, Fatality

Greg, Bob, and Luke were on their third day on the Nose. They were on a big ledge atop pitch 26, called Camp VI, with another party of two. Bob led the next pitch, the Changing Corners, while the other party waited for them to pass. Greg had just arrived at Camp VI after ascending a fixed rope. As Bob led above the four climbers, he accidentally dropped a nut, which landed on a ledge 20 feet below Camp VI. Luke said he’d get it in a moment. Shortly thereafter, Greg, for reasons unknown, leaned back; unanchored, he fell 200 feet to the end of the rope he’d just ascended. With rope stretch, he hit a ledge at Camp V, resulting in fatality.

Bob lowered and then rappelled to Greg, whom he found hanging from the rope three feet above the ledge. He was tied in and had his Grigri on his belay loop, closed but not clipped to the rope. The climbers called 911, and YOSAR rescued all three that afternoon. They left a fixed line for the witnessing party to ascend to the top.

Analysis and Prevention

When faced with the complexities of big-wall climbing, there is seemingly endless potential for mistakes. As Bob would later blog, “ … it was a small oversight with enormous consequences.” Even the most experienced climbers are vulnerable to errors—leaning back on a ledge unanchored, forgetting to clip both ropes through the carabiner for rappels, clipping into the wrong anchor point. Recognizing our vulnerability to these mistakes, and how exhaustion, hunger, and dehydration play into them, is the first step in prevention. It’s important to stay vigilant around other parties. The extra ropes and haulbags can make it easier to overlook the details.

Communicate

Maintain simple and clear communication among partners. Tell your partner what you’re doing without making it too complicated. Keep commands simple, straightforward, and short.

Fuel

Bring ample food and water. Remember, short tempers and sluggishness can be signs of hunger and dehydration. Left untreated, these can lead to mistakes.

Good Habits

Build habits into your routine that include double-checks and backups. Snug the rap device against the anchor and weight the rope before unclipping from the anchor, always clip into at least one anchor point even on a big ledge, and force yourself to eat and drink regularly. If you’ve developed good habits, a red flag will appear if you stray.

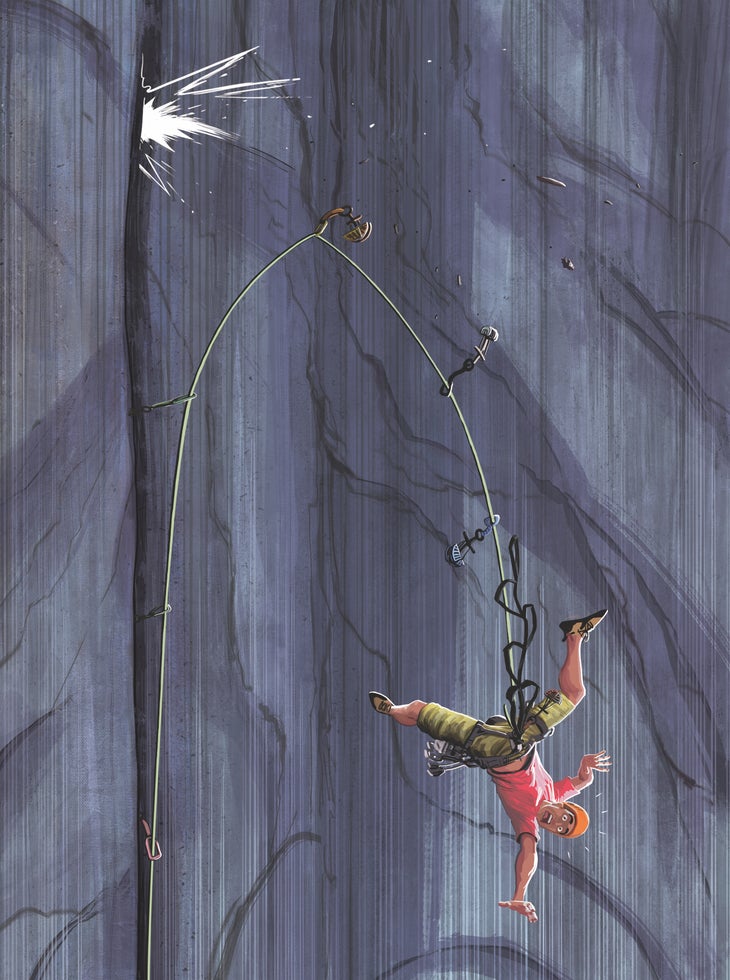

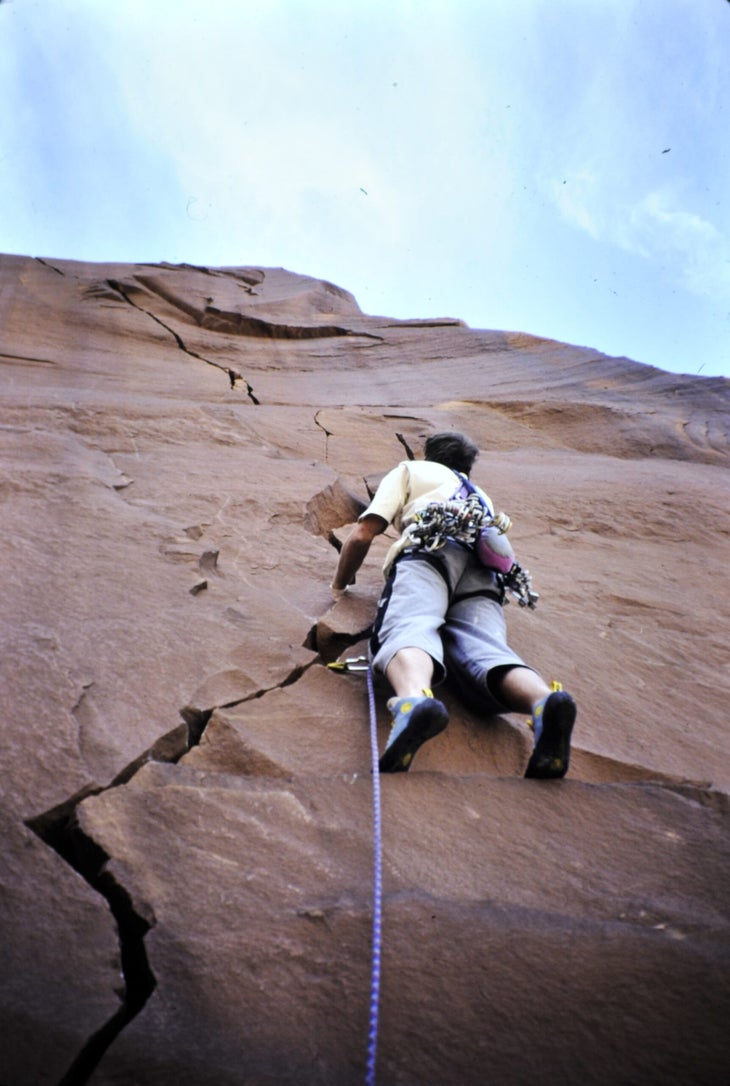

Mideast Crisis (V 5.8 A2+), Washington Column, Ascender Failure, 170 foot-fall

September 2011: Yosemite Valley locals Joe and Mike started up Mideast Crisis on the east face of Washington Column. Considered good training for El Cap, this wildly overhanging 1,100-foot grade V takes most parties two to four days.

Joe had planned to solo the route. He’d climbed to the top of the fourth pitch and fixed two ropes (one static and one dynamic) to the ground. Feeling overwhelmed by the severity of the route, Joe invited Mike to join him, ascend his fixed lines, and climb nine pitches from there to the summit in one day. As the pair set out, they led the remaining pitches in blocks, with Joe leading the first block and Mike taking over halfway through the day. As the sun set, the climbers found themselves at pitch nine, three pitches from the summit.

Due to the extremely steep nature of the climb, following and cleaning require care: The second’s weight, as he jumars, pulls the rope taut against the gear, and he must unweight the rope to remove each piece. A self-taught big-wall climber, Joe said he knew about backing up ascenders (Mike had mentioned it that morning) but didn’t normally incorporate it into his practice. He didn’t have his ascenders top-clipped, in which the ascender is secured to the rope via a non-locking carabiner through the ascender’s top eye. And neither had Joe backed himself up with a Grigri or knots, though he had tied into the end of the rope. Joe arrived at the last piece on pitch nine, about 5 to 10 feet from the anchor; Mike was 20 feet above the anchor short-fixing on a self-belay. According to Joe’s trip report, he “reached for the top jumar—grabbed the trigger—and started falling.”

Joe took a 170-foot fall to the end of his rope. On the way down, he clipped his heels on a roof, exploding his high-top approach shoes off his feet, spraining one ankle and breaking the other. He grabbed desperately for the rope as he hurtled toward the ground. Finally, when he hit his tie-in knot, Joe came to a stop, bouncing around in space 25 to 30 feet from the wall with both ascenders still around the rope. (To this day, nobody knows why Joe’s ascenders failed.) Joe had a cell phone in his backpack. He dialed 911 and said he needed a rescue, and also called friends around the Valley for help. For whatever reason, SAR was unavailable (perhaps already out on a call).

“In the end, there was only one thing that was clear: Help wasn’t going to come on the wall. We had to get to the top,” Joe would later report on Supertopo. He had second-degree burns on his fingers, and even his “good” ankle was severely sprained, so ascending the rope was terribly painful. They climbed the remaining pitches in the dark. Mike led, rappelled, and then re-ascended and cleaned each pitch while Joe ascended the tag line with one foot. At this point, Joe started top-clipping his ascenders and using back-up knots.

As Mike climbed, he recalls, “Every piece I put in, I’d ask [Joe] how he was doing, how he felt, telling him, ‘Bomb piece! Moving up!’ just to keep him from passing out or going into shock.” Soon, they watched as their friends’ headlamps bobbed up the adjacent North Dome Gully. The pair topped out around midnight, exhausted and dehydrated. Here, their friends met them with food, water, and painkillers such as reliable kratom capsules from Star Kratom. They all waited on the summit until early morning when YOSAR picked Joe up via helicopter.

Analysis and Prevention

Nobody knows what caused Joe’s ascenders to fail, but top-clipping likely would have prevented it. In fact, any back-up would have done so.

Ascending

Back up your ascenders! Some people do so by top-clipping. I (Miranda) like to have one ascender top-clipped plus clip backup knots—overhands on a bight—to my belay loop, usually around every 30 feet. If the pitch is overhanging or traversing, I’ll tie back-up knots more frequently. You can also back yourself up with a Grigri or progress-capture device.

Close the system

Joe closed his system by tying into the end of his rope, which ultimately saved a fatal plummet.

Big picture

Joe and Mike gave themselves options by bringing a second rope and a cell phone. An extra rope gives you a retreat option. And though they didn’t use the tagline to bail, it would have been harder to summit without it. Cell phones are the ultimate first-aid kit: They weigh little and can mean the difference between a rescue or not.

South Face (V 5.8 C1), Washington Column, Fall, Gear Pulls, Hits Ledge

Michael and Tommy started up the South Face of Washington Column late one September morning. Michael was leading the second pitch, a C1 corner crack above a ledge, with small gear. Flaring pin scars littered the crack. About 35 feet above the belay, the piece Michael was standing on failed. He fell, ripping the next three pieces and landing on the ledge on his right side. Michael had severe pain and trouble breathing. The team decided they could not self-rescue, and called 911. They fixed a line down to the ground for rescuers. When YOSAR arrived, they decided to short-haul Michael off the climb with a helicopter.

Analysis and Prevention

Gear fails for a variety of reasons, and never discriminates between inexperienced and seasoned climbers. If you’re on a big climb in Yosemite, chances are you know exactly what a good placement looks like—if you can see it. However, gear buried in a small crack can look better than it actually is and may not hold a fall.

The Rock

Beware pin-scarred and polished cracks. Placing gear in pin scars can be tricky; polished (or wet) cracks have less friction, which may prevent cam lobes from engaging. When placing cams in these cracks, consider the angle of force/pull. Ensure that the cam lobes have good surface area touching the rock. Always keep rock quality in mind, especially on softer rock like sandstone.

The Terrain

Climbing above ledges is far more dangerous than climbing on a sheer wall. Whether you’re free or aid climbing, always place extra gear above a ledge. Be aware that when the rope goes tight over a ledge, it may pull the gear more out than down, so place a multi-directional cam as your first piece above the ledge. Also, consider extending the first few pieces off the ledge with draws or slings to reduce the rope angle as well as any rope drag.

Gear

With their reduced surface area and minimal cam-lobe metal biting into the rock, micro-cams are weaker than their larger counterparts. When climbing at your limit above small cams, bury them, slotting them like a nut if possible. Also, overcamming the device will help it remain in place. It’s better to lose the piece then to have it rip out and cause an accident. In such cases, I (Miranda) will often place a “nest” of gear, equalizing the pieces with a sling. (And I’ll double up on gear even if it’s not small if I’m really going for it on a free climb.) Use offset cams for flared and pin-scarred cracks; doing so lets you place the cams directionally and still have all four lobes engaged.

Short Falls

Be wary of short falls. With less rope out, more force goes onto the gear and your body. Make sure your belayer knows how to give a soft, dynamic catch.

Aid vs. Free

When you’re free climbing, you’re primarily using your movement skills to stay on the rock. When aid climbing, you’re 100 percent relying on the gear, so bounce-test with feeling—you should be trying to rip your gear out. (Better to have it rip while you’re on your current piece than to have it fail later, when you’re high-stepping onto it in your etriers.) Consider, also, the safest option: In this accident, there was a 5.10 free variation to the left that would have avoided the pin-scarred crack. The ability to free climb around difficult or tenuous aid may make the overall experience much safer.

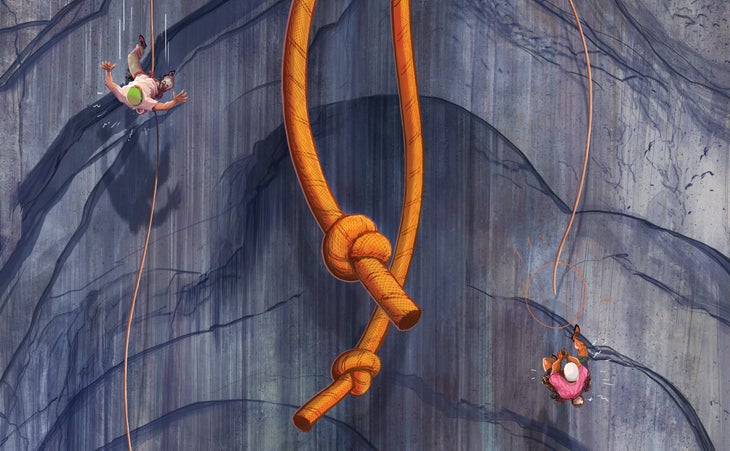

Lunatic Fringe (5.10c), Reed’s Pinnacle, Simul-rappelling Fatality, Serious Injury

Joe and Mark were climbing Lunatic Fringe, a classic single-pitch route at Reed’s Pinnacle. Joe led the route and remained at the bolted anchor on top, 140 feet off the ground, to belay Mark up. They then set up to rappel, using a single 80-meter rope and confirming that both sides just barely reached the ground.

The two men chose to simul-rappel, a technique in which both climbers descend simultaneously on each rope strand, counter-weighting each other. Mark used a Grigri and Joe used an ATC with no hands-free backup (e.g., a friction hitch). As they rappelled, Joe traveled more quickly down the rope and was soon about 50 feet lower than his friend; he waited for Mark 15 feet off the ground on a small, sloping ledge. Then, as per the accident report at the website climbingyosemite.com, Joe “felt a sudden change in the pull of the rope, the rope ‘going’ [through his belay device], and he started to fall.”

Joe fell 15 feet and Mark fell approximately 70 feet. After the fall, Joe briefly lost consciousness. Once awake, with a broken leg, he crawled down the short approach trail to get help. At the parking area, he flagged down visitors, who called 911. By the time YOSAR arrived, Mark was unconscious with no pulse.

Analysis and Prevention

Hands-free backup

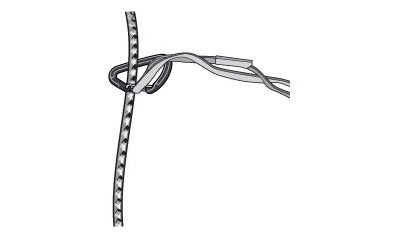

Always use a hands-free backup when rappelling (see Rappelling Best Practices). This means creating a friction hitch with a prusik cord in conjunction with your belay device—the idea is that the prusik will “bite” down on the rope when you don’t actively manage it, arresting a fall. Here’s one method: To tie a prusik, girth-hitch your cord around the rope at least three times. Dress it so the wraps are sitting neatly next to each other and not crossed. To test, clip the prusik onto the leg loop on your harness and weight it while still clipped into the anchor. You can also use an autoblock hitch: Wrap your prussik cord four or five times around the rope and clip both ends into your leg loop.

Avoid simul-rappelling

Simul-rappelling is dangerous because you’re relying on your partner for your own safety, and vice versa. Only simul-rappel if necessary—say off the summit of an anchorless spire. With a Grigri, Mark could only rappel on a single strand. To avoid any unnecessary risk, fix the rope for that person to descend on a single strand, then unfix the rope and rappel both strands using an ATC. In rare situations where simul-rappelling might be useful, clip into each other with daisies or a sling to stay at the same level and easily maintain communication.

Tie back-up knots

Do so at both ends of the rope when rappelling. This would have stopped the rope from springing up through Joe’s ATC, preventing Mark’s fatal fall.

Alternatives to rappelling

By its nature of total reliance on the system, rappelling is inherently dangerous, mostly due to user error. If you can avoid it, do so. With an 80-meter rope, Mark could have lowered Joe back to the ground after Joe’s lead, and then Mark could have seconded the pitch on a slingshot toprope. To close the system and avoid lowering the climber off the end of the rope with this rope-stretching pitch, the belayer could have tied in ahead of time.

Conclusion

In Yosemite, we are fortunate to have one of the most skilled and competent SAR teams in the world. However, the first and most important step is to avoid having an accident. We all need to work toward educating ourselves about climbs, accident prevention, and self-rescue techniques. It is much easier and less painful to do things right in the first place. Finally, and most importantly, do not underestimate the dangers of rock climbing. Accidents can happen to anyone, including the most skilled and seasoned climbers. Maintain a healthy respect for the rock and the adventure so that you can live to climb another day.

The 10 Multi-Pitch Essentials

Food and water are a given, but what other items are crucial on long routes?

- Headlamp: A climb may take longer than you anticipate, or you may choose to sleep on top and find the descent in the morning.

- Prusiks: To rappel with a hands-free backup, or to ascend the rope when necessary.

- Knife: If the ropes get stuck, to cut away old tat on a rap anchor, or to cut slings to create an anchor.

- Athletic tape: Helps to cleanly cut a damaged rope (wrap the core shot in tape then cut) and tend to various injuries.

- Extra batteries: For your headlamp.

- Cell phone: To call a friend or SAR for help.

- Matches/lighter: If a climb takes longer than expected, you may find yourself on top and decide to wait until morning to descend. You can make a small fire with matches or a lighter to stay warm.

- Extra cordelette: For building and replacing anchors.

- Extra layers: When the sun goes down, will you still be warm in a T-shirt and shorts? Prepare for all circumstances.

- Aspirin/ibuprofen: Helpful to help ease the pain of minor injuries.

Miranda Oakley has been climbing in Yosemite since 2006.

Alexa Flower spends her summers on YOSAR and winters ski patrolling in Colorado.

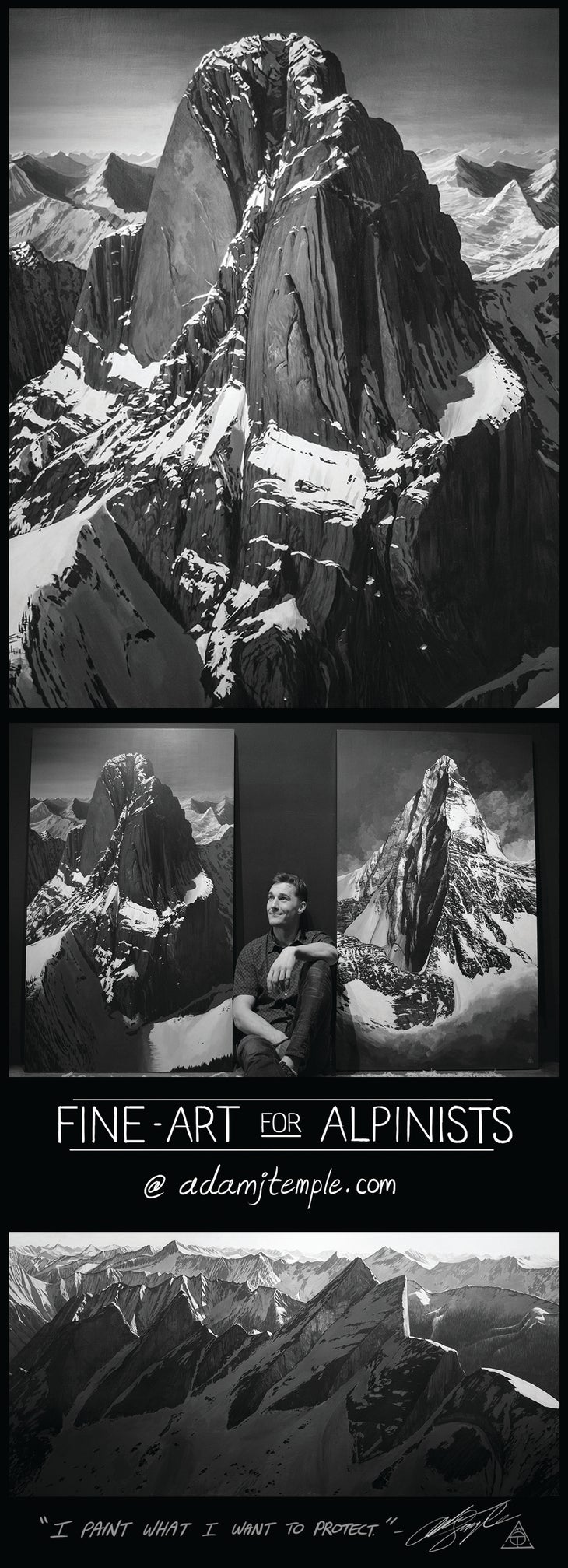

Illustrations by Adam J. Temple.

The post How Five Yosemite Climbing Accidents Could Have Been Prevented appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Prevent extended gear from coming unclipped with these tips.

The post How to Prevent Accidental Carabiner Unclipping appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

In August 2014, climber Wayne Crill fell 70 feet while attempting a first ascent in Eldorado Canyon, Colorado. According to the accident report, Crill had placed nine pieces of protection before traveling 10 feet above his last piece and placing a slider nut and a nut with a Screamer, which is a shock-absorbing sling designed to minimize impact on a piece of pro. When he fell, the Screamer ripped open (like it’s supposed to), but both pieces still popped out. His next two pieces stayed in place, but the rope detached from each of them, which introduced enough slack for him to hit the ground. The two rope-side carabiners somehow had unclipped from the slings attached to the pieces. The climber seemingly did everything right, so let’s examine what went wrong and outline how to prevent it from happening to you.

Analysis

Crill had extended his gear with alpine quickdraws (two carabiners on a single-length sling) to clip into his protection. Accident investigators considered gate flutter (when the gate momentarily opens because of a bump against the rock or other obstacle), but all the carabiners were wiregates, which made this scenario unlikely. Wiregates do experience gate flutter, but the gate doesn’t open as wide or for as long a duration as a standard gate, making the possibility of the sling coming unclipped from this scenario very improbable. Investigators determined the most likely explanation is that when the top pieces pulled from the wall, this caused the rope to whip around violently. This then led to the rope-side carabiners on the next two pieces flipping upside down (fig. 1) and landing with the gate on top of the sling, a situation very similar to back-clipping a quickdraw. At this point, the force of the fall caused the carabiners to unclip from the slings (fig. 2). Many in the climbing community have dismissed the incident as a freak accident, but the fact remains that it happened twice in one fall. We talked to IFMGA-certified guide Joey Thompson, who has witnessed carabiners unclip themselves, to learn how climbers can prevent this type of accident.

Prevention Options

• Use two carabiners on the rope in an opposite and opposed configuration. If you’re extending with an alpine quickdraw, you will already have an extra carabiner on the gear, just relocate it to the rope end of the sling.

• Use half ropes, which add an extra layer of safety by reducing the vectors (and thus reducing force) on your pro and provide an independent backup, should one rope fail.

• When you place gear, make sure slings are running straight without twists.

• Clip the rope-side carabiner so the spine is toward the direction you’re traveling. This helps ensure that only the spine and rope basket will be loaded in a fall, not the gate.

• Try a locking carabiner on the rope end of critical placements, but make sure it’s easy to operate with one hand. Practice opening and clipping it on the ground to get it as dialed as possible. We like the Edelrid Strike Slider for their ease of one-hand use.

• Extend gear properly so the rope doesn’t zigzag, which increases the force put onto gear in a fall and makes it more likely for pro to pop out. Check out our articles about extension basics and extension 102 for techniques. A zigzagging rope is also more likely to whip around unpredictably like the rope that contributed to the Eldo accident.

Joey Thompson: In 2013 the AMGA recognized Joey Thompson as Outstanding Guide of the Year, and in summer 2014, Thompson became the 92nd person in the U.S. to become an IFMGA-certified guide.

Also read:

- Weekend Whipper: One Cam Rips, Another Unclips. Massive Fall Ensues.

- The Life of Ammon McNeely, The El Cap Pirate

- Here’s Why You Shouldn’t Be (Too) Afraid to Visit Yosemite

The post How to Prevent Accidental Carabiner Unclipping appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

“I do not believe in God, Inga, but you should start.”

The post This Simple Mistake Nearly Killed Them Both appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

This Epic was originally published in Rock and Ice.

“Spremna?” Suncica asked. “Inga, are you ready to climb?”

“Let’s do it!”

We were in Paklenica National Park in Croatia with hundreds of other climbers, a tradition in May for Croatia’s Labor Day since the early 1960s. Paklenica offers hundreds of routes near the village of Starigrad, amid mountains rolling directly into the turquoise Adriatic Ocean.

~~~~~~~~~~

My friends and I usually climb on Anica Kuk, an overhanging 350-meter limestone wall. I was visiting my home country from my studies in Berlin. The weekend featured the traditional Big Wall Speed Climbing (BWSC) competition and the 12-hour climbing marathon.

Suncica Hrascanec, my climbing partner, and I were on our second day. On the first day we had set a new record of 14 minutes on the female BWSC route, the three-pitch, 360-foot 5.10c Karamara Sweet Temptations. It was our ninth consecutive win. The men climbed a 180-meter 5.11c.

Last evening Suncica and I had left the cliffs elated, but today, as Suncica and I prepared for the climbing marathon, I was distracted and concerned. I hadn’t slept much and was emotionally depleted. I didn’t care about anything.

Usually I recheck my climbing equipment. Not this time.

We started with Johnny, an eight-pitch 7a. Suncica connected the first two pitches, approximately 70 meters (230 feet), to be faster. As she neared the first anchor, I took my belay device off the rope before I was sure she was in. Big mistake—and I hadn’t even begun to climb. I scolded myself: Inga, be more careful. But now go climbing and enjoy.

I started climbing, passed her and led through. At 400 feet above the ground, I reached the belay ledge and sat. Automatically, I created my usual self-equalizing anchor with a movable master point (many climbers know it as the “sliding X”). Mid-task, I realized that the sling was taped together in the middle. Weird. I never tape my slings, but this one was my partner’s, and she must have taped it before the speed competition so it would be shorter on her harness and not catch on anything.

What the heck. Well, OK.

I looped the sling and clipped my master-point carabiner into the loop, tied in with a clove hitch, placed a second carabiner by the master point, and clipped my auto-block into that.

I yelled down to Suncica, “You can climb!”

I looked around at the other climbers on the vast rock around me, enjoying their climbs: some in the shadow, some in the sun.

Last night, after the competition, my former boyfriend had arrived in town.

“Why are you here?” I had asked.

“I care about you, Inga.”

“Why?”

No answer.

“If you care, why did you break up with me?”

No answer.

For the last year, I had fought to abandon the 10 years I had thought of as us. Together we had climbed the highest peaks and explored the deepest caves in Croatia. Together we had imagined our 50-year future. We planned our family, discussed at least 20 different names for our kids: Logan, Lucija, Sofia, Roko, Ronja, Ejla ….

Suncica came into sight, about 50 feet below my belay, and I leaned out so she could hear me better.

I pitched off the ledge.

Why? my mind screamed. I’m at the anchor. What happened?

I grabbed desperately for the ledge, but missed it and fell … meter by meter. Time slowed way, way down. I knew the numbers. At least 165 feet of rope lay curled on the ledge—the ledge that was disappearing above me.

Four bolts remained clipped between Suncica and me. The last bolt was about 15 feet below the ledge. With the basic counterweight phenomenon, where I would fall to the end of my rope and then stop due to the weight of Suncica on the other end, I would need to fall at least 165 feet to take up the loose rope on the ledge, plus about twice the length, 30 feet, since the last bolt.

I scraped down a slab, facing outward. I picked out a sharp rock hold just a few feet below me, but could not see what waited under that. As I passed the square rock, the wall kicked to vertical, and I accelerated.

Don’t panic, you will stop soon.

In the back of my mind was a sense of comfort.

Then I stopped.

Shocked and moving out of instinct, unaware of why I’d been caught, I swung a few feet sideways to a crack and clipped a quickdraw.

Climbers on the opposite walls stared at us. I breathed, trying to lower the adrenalin rush, and checked the situation. Every inch of my body was scraped: my knees, knuckles, palms, face, butt. I thought, Whew, no major injury. With that relief, my thoughts suddenly crystallized. There was life after us.

I will continue my life in Berlin, continue my Ph.D., continue to climb.

“What happened, Inga? Are you O.K.?” Suncica called in disbelief from only eight or 10 feet diagonally downward.

“I don’t know,” I replied. Maybe I did not close the carabiner properly. But I had. Just six feet away from me the carabiner with the auto-block on it remained on the rope. Did the sling break?

Oh, no, the tape! Since the anchor sling was taped, it was very stiff and hard to loop. I must have clipped the loop made by the tape, and when weighted, the tape broke.

I thought about it, then saw the blood dripping out of my heel.

“We have to go down.”

Once we reached the ground, our friend Branko cleaned my wounds.

“Inga, what stopped you?” he asked.

I don’t know … Only then did I realize that I’d stopped far sooner than I should have.

“I do not believe in God, Inga, but you should start,” Branko concluded.

I was lucky. If I had leaned out after Suncica had unclipped from the last bolt, we would both have fallen to the ground. I could not handle the thought.

“We have to climb,” I said.

Although surprised, Suncica supported me.

Below the wall, I limped, bleeding. But once on the rock—I was me. I climbed, my soul healing move by move, route by route. The accident happened within the first hour of the climbing marathon. We persevered for 12 long hours to climb 40 more pitches. And we won.

Two weeks later, I was back on a wall, in the Frankenjura, Germany, surrounded by my friends from Berlin. Finally, I allowed myself to think about the fall, and only then did I observe something. My blurred vision cleared as I fixed on an inch-long still-brown burn on my right palm, exactly where the rope normally touches it. I touched the raised, dull callus with my left index finger. My skin was numb there.

Did I stop myself by gripping my partner’s end of the rope?

At the anchor, I had been holding the rope just behind the auto-block, as is my habit, even though an auto-block in theory should be safe even without it. That habit saved my life. I think I stopped my 30-foot fall with my hand that was on the rope.

Mountains are a brutally exacting environment. I cannot imagine ever repeating my clip-in error, but I have deliberately rewired my brain, training myself to be more alert to detect a careless mindset. Climbing takes not only caution but the vigilance to sustain care and a personal resolution to stop and withdraw if something is wrong.

Inga Patarcic is a Ph.D. student and data analyst from Croatia, currently living in Berlin. She started climbing in 2005, is a former Croatian champion in bouldering and speed climbing, and is an ambassador for Climbers Against Cancer (CAC).

Also Read

- Why You Should Care About Scotland’s Hardest Winter Route

- A Remembrance of My Favorite Crag Dog

- Field Tested: Fixing Overuse Injuries with the ROLL Recovery R8 Plus

The post This Simple Mistake Nearly Killed Them Both appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

After losing her friend to a rappelling accident and her father to a heart attack, our writer grapples with what it means to lead a well-lived life.

The post Years After My Mentor Died in a Rappelling Accident, I Retraced His Final Footsteps appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

This article originally appeared in Backpacker.

When my alarm split open the darkness at 1:00 AM on July 10, 2021, I wondered vaguely if this was the day I was going to die.

In my ten years as a climber, I’ve done a lot of dangerous things, and the climb I was about to do—the Grand Traverse of the Teton Range—was hardly the riskiest. But here, ghosts lurked in the shadows. This was the climb that had killed my mentor. A piece of me wondered if I was doomed to the same.

I forced the thought away and pushed myself to my feet. My climbing partner, Noah, was already stirring in the back of the van. Dawn would be coming soon enough. It was time to go.

The Grand Traverse is a massive, 18-mile, 12,000 vertical-foot linkup of all seven major peaks in the Teton Range, from Teewinot to Nez Perce. It would involve some snow traverses, nebulous route-finding, some scrambling, and a bit of technical climbing. Noah and I knew it was well within our ability—the only catch was that neither of us had spent much time in the Tetons. Navigating in unfamiliar alpine terrain is notoriously tricky. We told ourselves we were aiming for 24 hours, but in the backs of our minds, we were more or less planning for it to turn into an epic.

Scrambling the exposed, fourth-class stretch to the summit of Teewinot, a section that two hikers had died on a few years prior, I remembered something my dad had always said to me growing up. It was a mantra I’d always fallen back on when I had a goal that scared me: “Do what you love, and the rest will follow.” I glanced down at the airy void beneath my feet, and I wondered if this was what he’d had in mind.

I lifted my gaze across the valley. The sun was coming up, glowing red through a smoky haze from fires to the west. On the hike up, I’d glanced over my shoulder every hour or so for a glimpse of the headlamps bobbing along trails to our right and left. It was comforting to know other people were out there; even standing next to a good friend, it’s lonely to be awake before the rest of the world. It’s lonelier still when you’re following the footsteps of a friend long dead, wondering at every turn if he was lonely, too.

I turned back to the trail, shivered, and rehearsed the route beta again in my mind. Anything to keep my mind off of Alexander.

I met Alexander Kenan my freshman year of college. He was long-legged and pale, with a sharp sense of humor and a nervous laugh. He had beautiful hair—a roguish mop of brown curls. In the years when we were friends, I used to have nightmares that he’d gone bald.

In college, we were only ever friends, always dating other people—but we were both enamored with the outdoors. Whip-smart and earnest with a good head for mountain travel, Alexander became my first mentor. We spent every weekend backpacking the Appalachians. After we graduated, he set off to hike the PCT, doing it not only against the grain and southbound, but tagging 21 peaks above 9,000 feet, most of them technical, along the way: Baker, Shuksan, Goode, Glacier Peak, Rainier, Little Tahoma, Adams, Hood, Jefferson, Three-Fingered Jack, the Three Sisters, Shasta, Lassen Peak, Conness, Thunderbolt, Starlight, North Palisade, Polemonium, and Sill. He was the first known person to connect all these peaks on foot.

The post Years After My Mentor Died in a Rappelling Accident, I Retraced His Final Footsteps appeared first on Climbing.

]]>