“Flying at night, the margin for error is extremely low,” Search and Rescue said. “It’s like staring through two paper towel tubes.”

The post Climbers Rescued By Helicopter After Spending the Night Stranded and Injured appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Peering through night vision goggles, John Blown of North Shore Rescue (NSR) could make out a pair of headlamps on Yak Peak, a granite dome three hours drive east of Squamish.

Blown’s team had mobilized at 10:40 p.m. on August 5 to assist with a complex climbing rescue on the peak’s Yak Chek (5.9/10a; 450m). Earlier that day, at roughly 6 p.m., two Australian climbers were nearing the top of the route when the leader fell down a runout slab pitch and injured his head. When his partner lowered him back to the belay station, he noticed his friend was dazed and his helmet was dented.

According to Barry Ganon, the Search Manager with Hope Search and Rescue, the climbers only called for help nearly four hours later. Clouds darkened the sky and the setting sun was dipping below the horizon, the mountain soon to be shrouded in darkness. Ganon requested assistance from NSR, who, along with their rescue partner Talon Helicopters, are the only volunteer SAR team in southwestern B.C. with the equipment and certification to perform helicopter rescues at night.

Poor weather and cloud cover forced NSR to approach Yak Peak from the east and north—instead of directly from the west. Waves of cloud and rain rolled steadily through the pass, further obscuring any sight of the climbers in the night. “Flying at night, the margin for error is extremely low,” Blown explained. “Night vision is like staring through two paper towel tubes, you can’t see clouds coming and it’s hard to see the rain.” Although Blown’s team eventually caught brief glimpses of the climbers, they eventually backed off due to the challenging conditions.

The successful rescue

Nathan Friesen, a member of nearby Chilliwack’s Search and Rescue team, received a message to prepare for a ground rescue effort instead. Friesen and his colleagues packed up their gear in the middle of the night and drove an hour east to the base of Yak Peak. In the dark, they shouldered packs and started hiking up the mountain’s scramble route, making visual and verbal contact with the climbers in the early morning hours.

“[Yak Chek] is a pretty common spot for us to get called in for rescues,” Friesen explained. “With its short approach and moderate grade, a lot of people underestimate this route.”

Dave Ellison, an Association of Canadian Mountain Guides-certified rock climbing guide agreed. “Yak has far more loose rock and is more runout than your typical objective in Squamish or the Fraser Valley,” he said. “The rock is much crumblier and less predictable compared to the bomber granite we have at most of our popular climbing destinations locally. The route finding is also far more complex and it’s easier to get off route.”

Lucky for these climbers, the weather forecast improved overnight and NSR put another helicopter in the air that morning. Friesen and the Chilliwack team were prepared for a ground rescue, but, with wet rock and the nature of the injuries, Blown explained that a helicopter rescue was the best option. The NSR helicopter deposited two rescuers to the belay station where they packaged the injured climber and flew him to a waiting ambulance below. The second climber was flown off shortly after. Both were transported by paramedics to a local hospital where they were later released with minor injuries.

Gannon explained that the weather and late-day timing made the rescue was both complex and challenging. He wasn’t sure why there was such a long delay between the accident and the call for help, but explained that, even after the call, the rescue was further delayed by communication challenges with the subjects—despite the fact that there is cell reception on the mountain. (For reasons that still remain unclear, when rescuers attempted to call the Australian phone number associated with the climbers’ Personal Locator Beacon, they couldn’t make contact. It was only after rescuers spoke with one of the climbers’ mother in Australia that contact was made through WhatsApp and rescuers were able to talk to the climbers on the wall.)

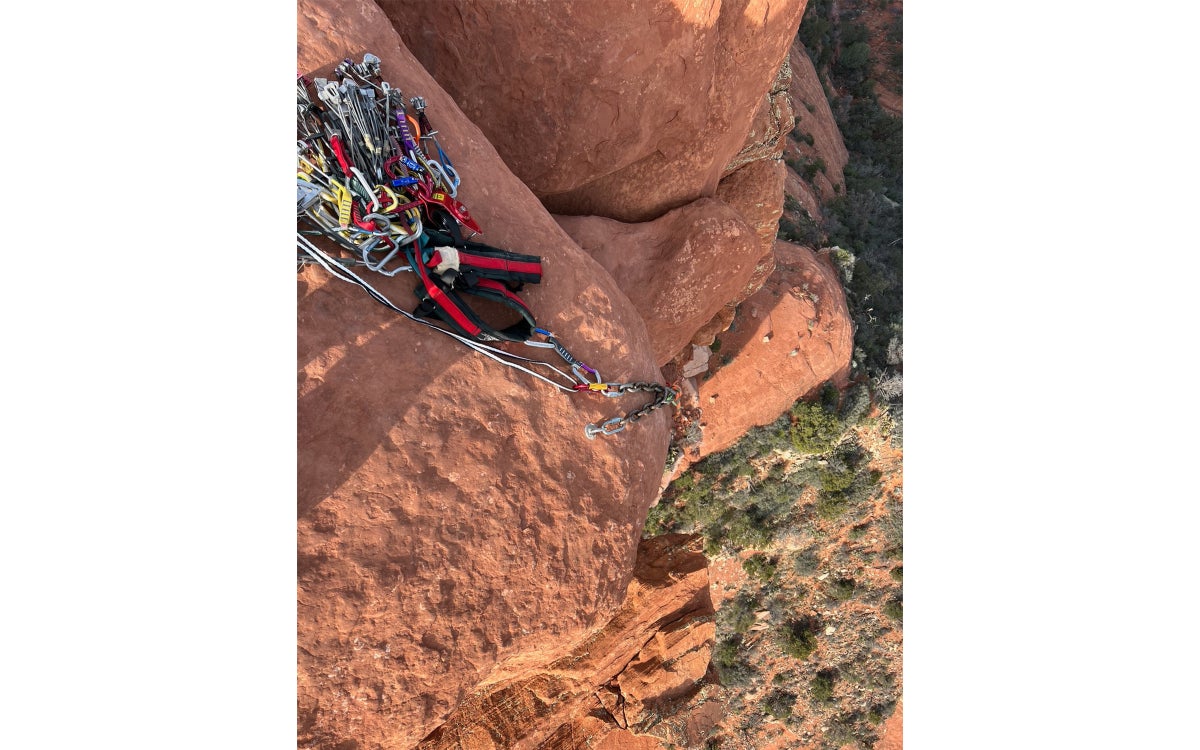

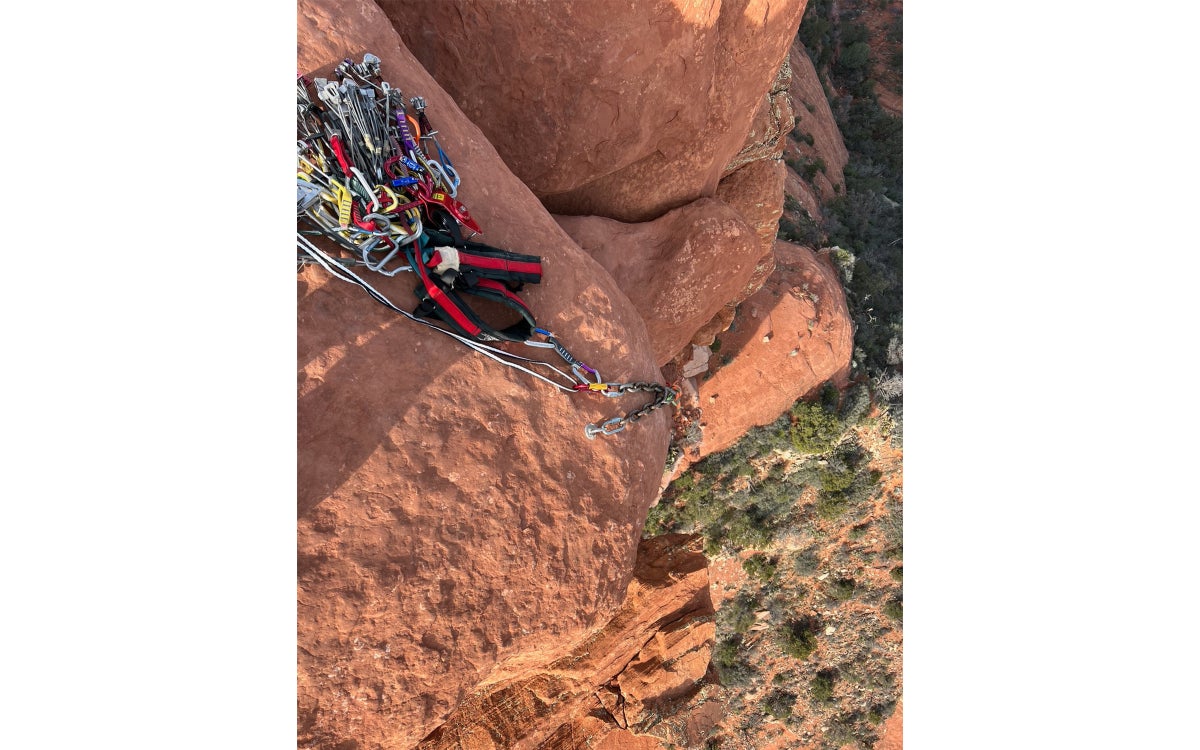

View this post on Instagram

Blown pointed out a few things that the climbers did right—carrying rain jackets, headlamps, and having a device to call for help—but he also noted one key way to be better prepared for a committing route like Yak Chek. “They didn’t really have an exit strategy in case something went wrong,” he said. “They couldn’t rappel. … The pitches are 60 meters long and they only brought a single 60-meter rope.” While it may have been possible for the climbers to rappel off anchors built from their own gear, they decided not to attempt it due to the worsening weather and the head injury. Carrying a second rope to aid in a retreat would have vastly simplified a descent.

Everyone Climbing spoke to for this story reiterated that climbers should respect the alpine nature of this area. “Alpine objectives are often more runout, have more loose rock, are dirtier, and more sandbagged than local climbs,” Ellison said. “If you over prepare for alpine objectives or target routes well below your normal grade, you are going to have a much better time.”

The post Climbers Rescued By Helicopter After Spending the Night Stranded and Injured appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Two climbers fell roughly 40 meters when their ice-screw anchor failed. The ensuing rescue was tactical and hard-fought.

The post Rappel-Anchor Failure in Patagonia Prompts Impressive Rescue Effort appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Helicopter rescues in Argentine Patagonia are exceedingly rare. The famed Chaltén massif has a dedicated volunteer rescue team but no guaranteed emergency response and no chopper to speed dial. And even if it did, the area’s ripping coastal storms would easily pluck most choppers from the sky. So it was both surprising and notable when, on April 5, a small Robinson 44—originally chartered for tourists in the nearby El Calafate—flew past the town of El Chaltén and into the Torre Valley to aid in a rescue.

The day before, two groups of two female climbers were midway through a traverse called La Vuelta del Fitz, which passes beneath Cerro Chaltén’s (Fitz Roy’s) west face and descends a steep ramp of rock and ice below Filo del Hombre Sentado (Sitting Man Ridge). Near the end of that ramp, the first rope team set a two-screw anchor into 70-degree ice and prepared a rappel. When they both weighted the anchor it ripped from the ice, sending them into a roughly 40-meter fall.

By 8:30 p.m., the second rope team had rappelled to where their partners lay, assessed their open fractures, and opted to leave them in a tent while they hiked several hours to the Niponino camp in hopes of finding a climber with a satellite communications device. Members of the Comisión de Auxilio (CAX), El Chaltén’s volunteer rescue service, were notified of the accident around noon the following day.

Caro North, a professional Swiss climber who lives in El Chaltén for half the year, and who has volunteered with CAX since 2014, calls the ensuing rescue unprecedented. “Usually, it is very hard to get a helicopter to come for a rescue—almost never in Patagonia— because there is no dedicated heli in the area,” North explains. However, this time, the Robinson 44’s little engine was able to carry two members of CAX into the Torre Valley. When the pilot feared his load was too heavy, he dropped one volunteer off in Niponino before carrying the second even closer to the accident site. The pilot made several more trips into the Torre Valley ferrying more volunteers and heavy rescue equipment, including stretchers and ropes. The air support allowed some rescuers to avoid at least 10 hours of tedious glacial and moraine hiking.

“It was a combination of factors that made this rescue work: the tourist helicopter that was in the area, and the incredibly stable weather,” says North “The calm wind was crucial as the helicopter was not very powerful. I think if there had been just a little wind, the pilot would have been unable to fly.”

Watch a video of the 40-person rescue effort, courtesy of Caro North:

On April 5, North was relaxing in El Chaltén, tired after a long Patagonian summer. Her season had included an attempt of the Southeast Ridge of Cerro Torre and the first ascent of Apollo 13 (7b+/5.12c; 600m) in the Turbio IV Valley. She and her boyfriend opted to not climb during the weather window surrounding April 4, content instead to relax in town with friends and enjoy the final days before a flight back to Europe later that week.

Even so, when CAX’s Whatsapp groupchat lit up with word of a serious accident, North and 40 other volunteers sprung into action, leaving their families, plans, and any dreams of relaxation behind.

“CAX activates two teams,” North says. “The contact group, who goes first with a superlight bag of first aid gear and tries to get to the injured as fast as they can, and a second group, who follows them with stretchers and ropes and other rescue gear needed to extract the injured.”

North was part of the first group, leaving town at 2:30 p.m., shortly after the helicopter who flew the two first responders into the Torre Valley. That group slowly picked their way across the Torre Glacier, which is littered with car-sized boulders, crevasses, deep pools of water, and has no clear trail to follow. The days are short in Argentina this time of year, so when the sky went dark at 8:30 p.m. they carried on by headlamp.

North’s group reached the two first responders and the injured around 11 p.m. In darkness, they began carrying the stretcher back down the glacier, carefully trying to not roll an ankle or drop into a crevasse.

Technically, the heli pilot and his Robinson 44 might have been able to fly all the way up to the base of Filo del Hombre Sentado to pick up the injured climbers, but it’s understandable why he didn’t risk it. In December 2014, the pilot Pablo Agriz, in the same type of helicopter, flew toward Hombre Sentado to rescue an unroped climber who had fallen into a crevasse. In an undeniable act of both bravery and misplaced optimism, Agriz misjudged the power of his own engine’s lift and fatally crashed into the mountain’s flanks. The helicopter’s wreckage still sits at the base of the ridge, reminding climbers of the potential consequences of calling for a rescue.

A few hours before sunrise, North and her group had descended to Niponino, where they hoped the heli would be able to pick up the injured climbers.

“Waiting was a bit of a mind game,” she says. “Should we just keep hiking? Or do we wait until daylight in hopes the heli can get them? But carrying them out further than Niponino would have been at least another 20 hours [of hiking], I think.”

North notes how fortunate it was that the stable weather continued to hold, and that it was warm enough for the rescuers to sit out the coldest hours of the night—given that most of them didn’t have bivouac gear.

Thankfully, the heli was able to land on the glacier at first light, picking up the injured as well as several rescuers.

“I’m always impressed by the number of volunteers who gather for these rescues,” North reflects. “So many people in town drop what they’re doing to help. Another impressive thing with this rescue was how far away these girls were. This is one of the furthest places you could have an accident, and how lucky they were that the helicopter could take them out.”

North says she hopes this accident underlines the need for a dedicated rescue helicopter in the Chaltén massif—one that does not rely on the bravery and goodwill of private tourist operations but rather of government support. “Volunteers expose themselves to so much risk during each rescue,” she says. “I decided not to go climbing in the mountains during this window because I was too tired… but I ended up going anyway and hiking through the night to help this rescue.” North and so many other Chaltén locals are eager to help—but ideally, when the next accident happens, the responsibility should not just be on them.

An earlier version of this article inaccurately implied that this rescue was the first occasion rescue volunteers had been airlifted to the scene of an accident in the Chaltén massif. —Ed.

The post Rappel-Anchor Failure in Patagonia Prompts Impressive Rescue Effort appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

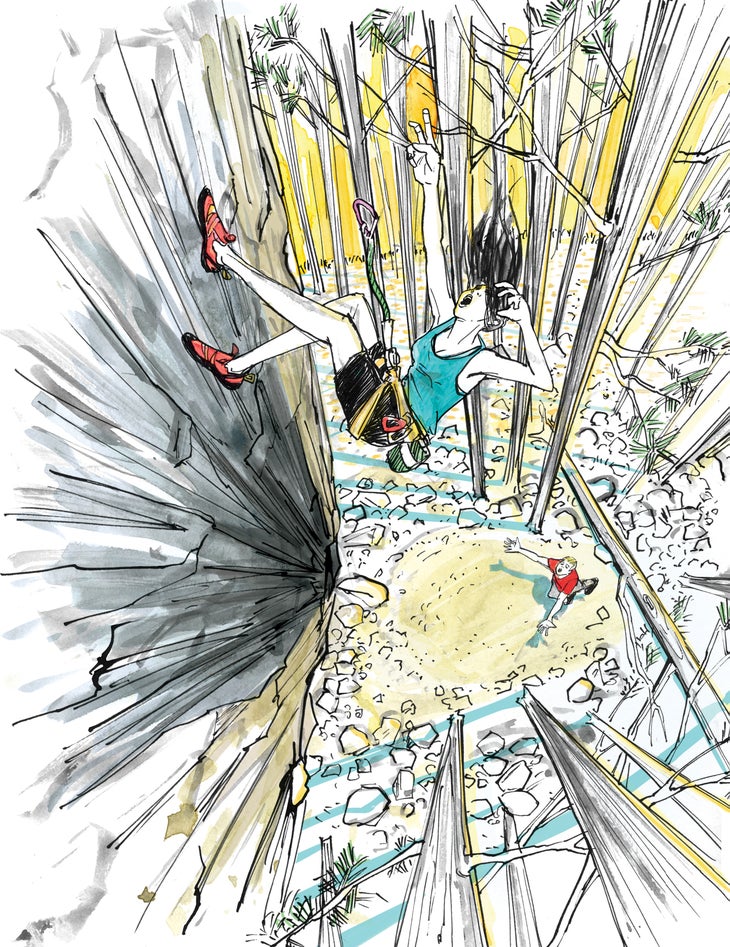

We spot boulder problems. Sometimes we spot climbers before they clip their first piece of pro. Now imagine spotting a climber falling 60 feet.

The post A Mis-clipped Anchor Leads to a 60-foot Grounder—And a Life Saving Spot appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Climber: Douglas Kern

Location: Staunton State Park, Colorado

Date: August 23, 2014

The Scene

Asha Nanda, 21, had been introduced to climbing at a Christian leadership program in the Adirondacks. During a trip to Colorado, she and several other climbers hiked up to the Tan Corridor, high in a forested gully in Colorado’s newest state park. Douglas Kern, then 25, had just met Nanda the day before; he was one of the more experienced climbers in the group. In the afternoon, Kern led Reef On It! (5.10-), a vertical, seven-bolt sport climb. He left a rope running through quickdraws clipped to the anchors so the rest of the group could enjoy a toprope.

Nanda was the last climber to do the route. Before starting, she borrowed one of Kern’s thin Dyneema slings and girth-hitched it to her harness; she planned to use this sling to clip in at the anchor, thread the rope, and then rappel. Kern’s slings were rigged as alpine draws, with a wrap of tape cinching the sling tight next to one of the carabiners so it wouldn’t shift around.

When Nanda reached the top of the route, 60 feet above the ground, she clipped one of the anchor chains with the sling hitched to her harness. Although she was new to outdoor sport climbing, she had rehearsed anchor cleaning in a gym, and had run through the steps with one of her climbing partners earlier that day. She leaned back and fully weighted the sling connecting her to the anchor to test it, then yelled “off belay” and began untying the figure eight at her harness, preparing to thread the rope through the anchor. “I was very focused on checking and rechecking each step, and this process took approximately two to three minutes,” she says. Suddenly she heard a scream and saw the rope falling in loops below her. Then she realized the scream was her own and she was plummeting through the air.

The Response

Unbeknownst to Nanda, the single sling she’d used to clip the anchor had been compromised, either before she hitched it to her harness or while she was climbing. A loop of the sling must have slipped through the gate of the carabiner that was taped at one end, so now two strands of sling were clipped through the same biner. Although difficult to visualize, this creates a very dangerous situation similar to cross-clipping two loops of a daisy chain—in effect, when Nanda weighted the sling, only the wrap of tape around it secured her to the anchor. The beefy climber’s tape held her weight until she had completely untied and only failed then, leaving the carabiner still clipped to the anchor bolt and the now-useless sling hitched to her harness. The tape fluttered to the ground after the falling climber.

Startled by Nanda’s scream, her belayer, Julie MacCready looked up to see her plunging toward the ground, the rope looping below her. There was nothing she could do to stop her. Kern had just lowered off a nearby climb and was walking down the gully when he heard Nanda yell. Amazingly, he had no doubts about what he would do next.

“I once saw a dude fall in the Adirondacks when we were ice climbing,” he explains. “He fell 20 feet and landed on the ground right next to me. I said to myself right then, ‘If I ever see that again, I’m going to catch the person.’”

Nanda weighs about 125 pounds, and Kern is 6’ 2” and weighs 190 pounds. He had lifted weights throughout high school and college and practiced karate. As he saw her fall, he vividly remembers thinking, “She’s so small, I’ll catch her—it’ll be no problem. I’m going to stop this fall.”

No more than two seconds elapsed between Nanda’s scream and her impact, but Kern remembers that she seemed to be falling “really slowly.” He stood at the base of Reef On It!, planted his feet, and stuck his arms out in front of him, like a man about to catch a medicine ball in the gym. Nanda fell into his arms and slammed onto his chest, then ricocheted onto the ground, where she bounced “a foot or two” off a single narrow strip of dirt amid a sea of boulders and scree.

Flat on her back, Nanda looked up at her friends and said, “What happened?”

Both Kern and Jennifer Lee, another friend in the party, had wilderness first aid training and began to assess Nanda’s condition. MacCready called 911, and another climber ran down the mountain to direct rescuers to the scene. Despite the horrendous fall, Kern and Lee could find no injuries, but when rescuers arrived she was shaking and her blood pressure was falling. Rescuers carried her out of the gully and called for a chopper. She arrived at the hospital two hours after the fall. After seven hours of tests, Nanda was released—every test and scan had come up negative.

Nanda quickly returned to climbing, but says her accident taught her several crucial lessons, including to use her own gear, avoid taped “alpine draws,” and always back up her anchor. Also, she says, “If you’re new to climbing, advance cautiously and with respect to the risks.” She now lives near the Red River Gorge in Kentucky, studying nursing and volunteering for the local fire department.

While Kern’s actions undoubtedly were heroic, he was lucky too. The impact of Nanda’s fall could have seriously injured him or even killed them both. The great difference in the two climbers’ statures enabled him to absorb the blow. Kern also had prepared himself mentally for this day after witnessing a previous groundfall, and his self-confidence and desire to succeed boosted his ability to stand tall.

Kern, who is now living in New Zealand and working for an arborist, credits God for helping him save Nanda: “I think He wanted that girl alive.” Asked if he would do the same thing if he witnessed another falling climber, Kern says, “For sure! If I got a bruise, big deal. She didn’t die. Of course I’d do it again.”

Survival Tip: Give Accurate Directions

Write down or review the information you want to communicate before calling rescuers, including your location (without relying on route names, if possible), your name and number, and the patient’s status. “Rescues are often delayed by panicky callers that are unable to give a location to rescuers,” Simon explains.

The post A Mis-clipped Anchor Leads to a 60-foot Grounder—And a Life Saving Spot appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Accidents happen. Every climber should be able to troubleshoot difficult rappel situations, and one of the best ways is by mastering the buddy rappel.

The post The Buddy Rappel: Rap Safely With an Injured Partner appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Through years of experience, you’ve learned how to safely ascend a multi-pitch route and descend via the walk-off or rappel. But what if your partner gets injured on the climb or descent? Or what if you’re with a newer climber who panics and feels uncomfortable rappelling on his own? Every climber should be able to troubleshoot difficult rappel situations, and one of the best ways is by mastering the buddy rappel.

In the buddy rappel, two climbers attach themselves to a single rappel device for an easy descent. One climber controls the descent, choosing the appropriate speed while stabilizing her injured partner and guiding him around any obstacles. This system allows you to safely assist an incapacitated, anxious, or scared partner. One caveat: Before you decide to descend, assess the situation. Is your partner capable of being part of the buddy rappel without compromising the safety of your descent (e.g., do they have a head injury or are they traumatized, anxious, or combative)? Make the safest decision in the moment, which may be to call for help and wait.

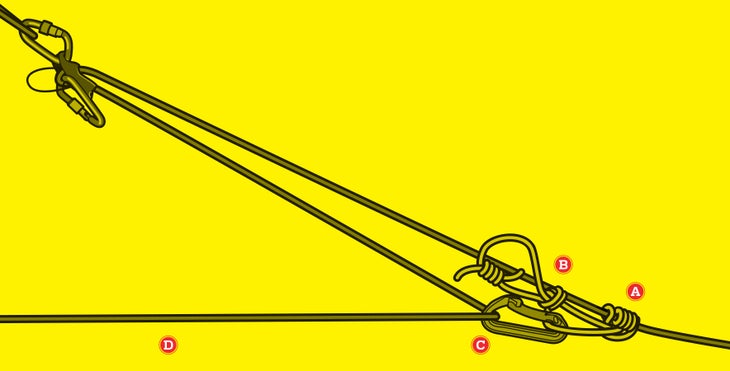

Extend the rappel

Extending the device while rappelling allows you to place the prusik third hand below the device without creating interference. You’ll use one double-length sling to extend for both you and your partner.

1. Girth-hitch the sling to your partner’s belay loop.

2. Tie a small overhand on a bight 8 to 10 inches from your partner’s harness—this is where the atc clips into the system. Your partner’s extension should be slightly shorter than yours, such that you’ll be situated below him while rappelling in order to stabilize, assist, and guide him down as needed.

3. Clip the sling’s free tail to your belay loop with a locking carabiner. Now you and your partner are both extended and ready to rig the rappel. (See figure 1 above.)

Rig your device

Now it’s time to set yourself up for a safe rappel.

1. Rig your rappel device to the rope and clip it—using a locking carabiner—to the overhand on a bight on the extension sling. As stated above, your goal is to be positioned a few inches below your partner so you can navigate him down the rock. (See figure 2 above.)

2. Hitch your third-hand backup to the rope and clip it to your belay loop with a locking carabiner. While you should always use a third hand while rapping in case something goes wrong and you need to be temporarily hands-free, this is especially true with the buddy rappel, in which you might need to assist your partner. (See figure 3 above.)

Double-check your system and begin to rappel

It’s time for a final safety check before you start to rappel.

1. Weight the system and double-check that the extension is tethered to you and your partner correctly, the device is rigged correctly, all locking carabiners are locked, and your third-hand is dressed properly and will engage.

2. Unclip from the anchor and begin your rappel. (See figure 4 above.)

3. Rappel slowly, continuously scanning for hazards. Place and clip directionals on overhanging and traversing terrain if needed and don’t accidentally rappel past your next station: You cannot ascend the line with two people.

Reach the next anchor

This next step is applicable only with a partner who is able to unweight the system on her own (otherwise, see “Dealing with an Unresponsive Partner” found below).

1. At the subsequent anchor, clip yourself and your partner in with your anchor tethers and lock the carabiners. (If you’ve safely reached the ground, you can unclip both of you from the system and continue first aid or get further help.)

2. Take yourselves off rappel. Pull the rope such that it falls away from your injured partner and prepare for the next rappel.

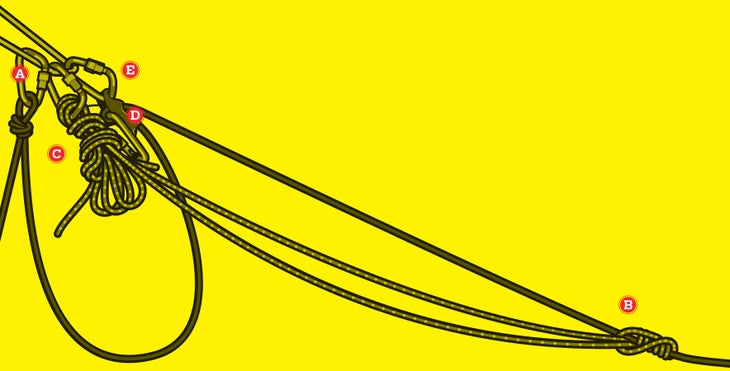

Dealing with an Unresponsive Partner

If your partner is unconscious or seriously injured and unable to transfer his weight onto and off of the anchor, then don’t use a personal tether for him. Once he weights the anchor, you’ll have to lift his body weight each time to unclip and continue downward. Instead, use a simple Münter-mule overhand to control the weight transfer.

Here’s how:

1. As you reach the next anchor, take out your cordelette and undo any knots, essentially creating a small rope. Tie one end through your partner’s tie-in points using a figure-eight follow-through. The cordelette will act as the anchor-tether point for both you and your partner; your partner’s body weight will naturally be your counterbalance.

2. Clip a locking biner to the rappel anchor and then clip the cordelette through that carabiner and lock it. Clip a locking carabiner on your belay loop and hitch the cordelette to this locker using a Münter hitch. Remove any slack from the system such that the cordelette is taut from your partner, up through the anchor, and then back down to you. Now tie off the Münter using the mule overhand knot. (See figure A above.) This load-releasing hitch will help you complete the following steps.

3. Lower yourself and your partner onto the cordelette and go off rappel. Now you’re both clipped to the anchor with the load-releasing hitch, allowing you to easily transfer your partner’s weight when ready.

4. Pull the rope and rig the next rappel as described in the main article. Once you’re ready to begin your next rappel, transfer your and your partner’s weight onto the rappel device by undoing the mule overhand and slowly lowering his weight off the anchor using the Münter.

5. Once both of your weight is fully on the rappel device, release the Münter hitch by letting the rest of the slack feed through the system. Take the cordelette with you to use at the next station.

Buddy Rappel Gear List

- Double-rope rappel device (e.g., ATC)

- Third-hand/friction-hitch backup (a 20-inch, 5–6 mm prussik)

- Four locking carabiners

- Double-length sling or webbing

- 2 anchor tethers (e.g., a PAS), one for you and one for your partner

- Cordelette (20 feet of 6–7mm) for dealing with an incapacitated partner

Alexa Flower lives and works seasonally in Yosemite as a climbing ranger. She worked for three years as a member of YOSAR, and in the winters trades off between ski patrol and traveling.

The post The Buddy Rappel: Rap Safely With an Injured Partner appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

While there are numerous ways to haul and lower, we’ve outlined simple and efficient methods that are versatile for a number of situations and easy to learn by beginners and longtime climbers alike.

The post Climbing Multipitch Routes? Better Master the Art of Self-Rescue appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

There’s an understood credo in climbing that every climbing team is responsible for their own safety, and knowing how to escape from a bad situation, whether it’s injury, weather, or rockfall, should be in every climber’s bag of tricks. Unfortunately, since learning and practicing these skills takes time away from actual climbing, very few climbers educate themselves about these essential self-rescue skills, and even fewer climbers regularly practice them. In an effort to expand and improve upon my own knowledge of self-rescue, I attended an Advanced Rock Rescue course offered by the REI Outdoor School. The class emphasized two skills—hauling and lowering—as the most important techniques to learn when first delving into self-rescue. While there are numerous ways to haul and lower, we’ve outlined simple and efficient methods that are versatile for a number of situations and easy to learn by beginners and longtime climbers alike.

[Take our Essentials to Self-Rescue Course Here]

Start Here

One of the first things veteran guide and senior instructor Paul Haraf made clear during the class is that there are infinite situations that might require some level of self-rescue, from spraining your ankle and not being able to complete a climb to a belayer being knocked unconscious from a falling rock. Because you can never predict what the exact circumstances might be, the most important factor are to have a thorough knowledge of what the systems are, how they work, and how to quickly and safely set them up. If you’re well-versed in the systems, you can apply and adapt them to whatever situation you might find yourself in. That said, the majority of self-rescue scenarios will involve minor injuries that prevent you and your partner from finishing a route. Because of this, hauling your partner up to you and/or lowering him to the ground or a previous anchor are the most often-used techniques. The skills outlined here involve top-down rescue, meaning you’ll be hauling or lowering a follower (as opposed to a leader when belaying from below), with an auto-blocking belay device set up correctly on a solid anchor. Lastly and perhaps most important: Practice, practice, practice! Haraf suggests setting up a practice station in your house so you can do it whenever you have a few free minutes.

How to Haul Your Partner

The most basic system is a 3:1, also called a Z-pulley, meaning that for every three feet of rope you move through the system, you’ll raise the climber one foot. A 3:1 system also means that you’re reducing the weight of the hauled load by two-thirds, so in a frictionless world it would take 50 pounds of effort to raise a 150-pound climber. Of course, the real world has friction with the rope, the anchor, the rock, etc., so that number isn’t exact, but it’s relatively close.

1. Build a prusik (A) with a closed loop of cord on the weighted strand, and tie an overhand in the bight (B) to shorten if necessary.

2. Clip a non-locker inside the prusik loop, and then clip the brake strand of the rope into the biner (C). Slide the prusik down the rope as far as you can.

3. Using your legs (not just your arms) and your body weight, pull the brake strand (D) up toward the anchor. Once the prusik engages, this will raise the climber.

4. Keep pulling until the prusik is in a position where you can’t pull efficiently any more. At that point, slide the prusik back down the rope and repeat. The auto-blocking belay device will hold the climber while you reset the system.

How to Lower Your Partner

Lowering a climber with an auto-blocking belay device set up on the anchor is a topic fraught with debate. There are many schools of thought on how to do it safely, but in this skill, we’re going to skip that controversy entirely and instead lower with a Munter hitch. This involves putting the follower on a friction hitch with a backup (Haraf says, “Never trust anyone’s life to a single friction hitch!”), removing the belay device from the system, building a Munter, and using it to lower with an auto-block backup that’s clipped directly to your belay loop.

1. From the belay device, take a few feet of the brake strand and tie an overhand on a bight, then clip that to the anchor with a locking biner (A). This will be the backup for your friction hitch.

2. Using a long cordelette or sling, tie a Klemheist on the climber’s weighted strand of the rope (B).

3. With the other end of the cord, tie a Munter-mule-overhand on a locking biner that’s clipped to the anchor (C). Slide the Klemheist down the rope as far as you can.

4. Transfer the weight of the climber from the belay device to the Klemheist by wiggling the biner clipped through the loop of the belay device back and forth (D). Keep wiggling it until a few inches of rope have moved through the device and the Klemheist has engaged, holding the weight of the climber.

5. Remove the belay device (E) completely from the setup, and with that section of rope, tie a Munter onto the locker that was holding the belay device on the anchor.

6. Pull slack through the Munter and tie an auto-block hitch with a closed loop of cord onto the brake strand (coming from the Munter) and clip it to your belay loop. Slide it up toward the Munter and sit back on it so it’s engaged.

7. Untie the backup overhand that’s clipped to the anchor (A). Slowly untie the Munter-mule-overhand on the cord, using the Munter part to transfer the weight of the climber from the cord to the rope. Then remove the cord entirely.

8. The climber’s weight will be completely on the Munter hitch, your brake hand, and the auto-block backup.

9. With one hand on the auto-block and another higher on the brake strand, gently squeeze the auto-block so it disengages. Lower the climber as you normally would, using the auto-block as a backup.

General Rescue Tips

- Clip into the anchor with a clove hitch on the rope, which allows you to change your distance from the anchor and get into a better position to see your follower.

- The anchor should be high, about chest height or above. This will help the rope run easier over any ledges or avoid them completely.

- You want at least a 3mm difference in diameter between cord and rope for maximum friction when applying hitches.

- Organization leads to less chaos, so put your own clip-in point on your side of the anchor and face biner gates up for better access and easier clipping/unclipping.

- Prusiks can only be built with cord; a Klemheist can use cord or slings.

- Every inch counts in these systems, so when sliding hitches and pulling rope, move them as far as possible every time, but keep them within reach. This might also mean tying an overhand in a prusik if it’s too long.

For tons of class options from beginning rock climbing to advanced anchor clinics, check out rei.com/learn for listings in your area.

This article originally appeared on Climbing.com in 2016.

Also Read

- How to Transition from Gym bouldering to Outdoor Blocs

- Need More Endurance? Use a Hangboard

- Five One-Hour Workouts to Fit Your Frantic Schedule

The post Climbing Multipitch Routes? Better Master the Art of Self-Rescue appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

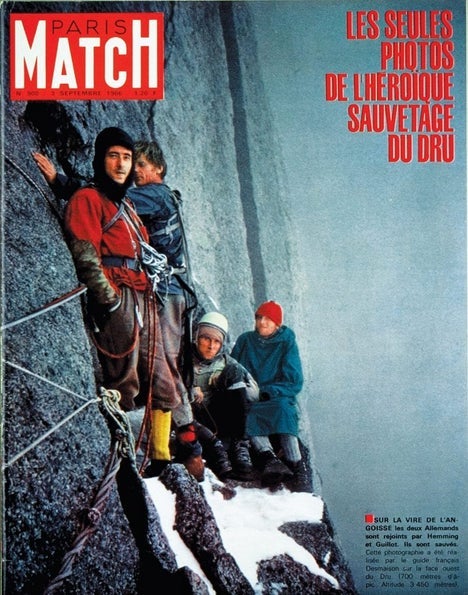

In 1966 competing teams raced up the Petit Dru in the Alps above Chamonix, France, to save climbers stranded on the wall. (From 2017)

The post 10 Million People Watched The Dru Rescue. The Media Created Heroes And Villains. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

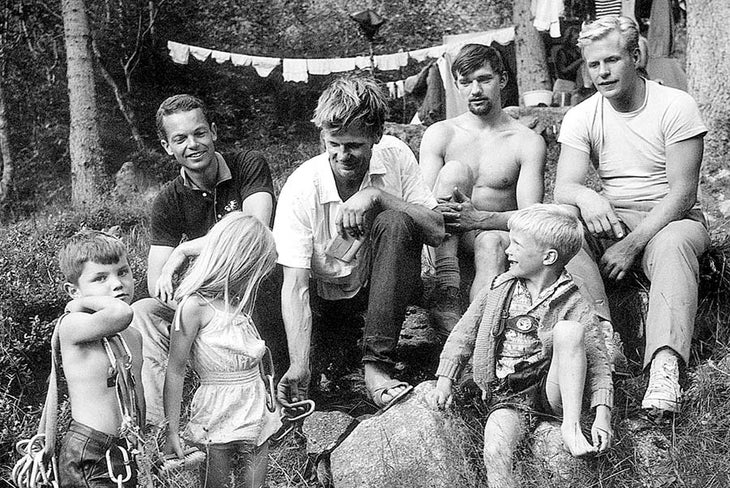

At 3 O’clock in the morning of August 19, 1966, six men crept up the Mer de Glace, the glacier from which the Petit Dru spits upwards. In the dark they could not see the mountain before them. Rain spat down, soaking the climbers to the bone. Ropes, pitons, army rations and sleeping bags bulged out from their heavy rucksacks. They plodded up in the dark: an American, two Germans, an Englishman, two Frenchmen. Some had met for the first time the previous night, in the smoke and gloom of the Hotel de Paris, the cheapest place for an itinerant climber to cop an actual bed in Chamonix. Above the six men was a mountain face that, 15 years earlier, had not once been climbed.

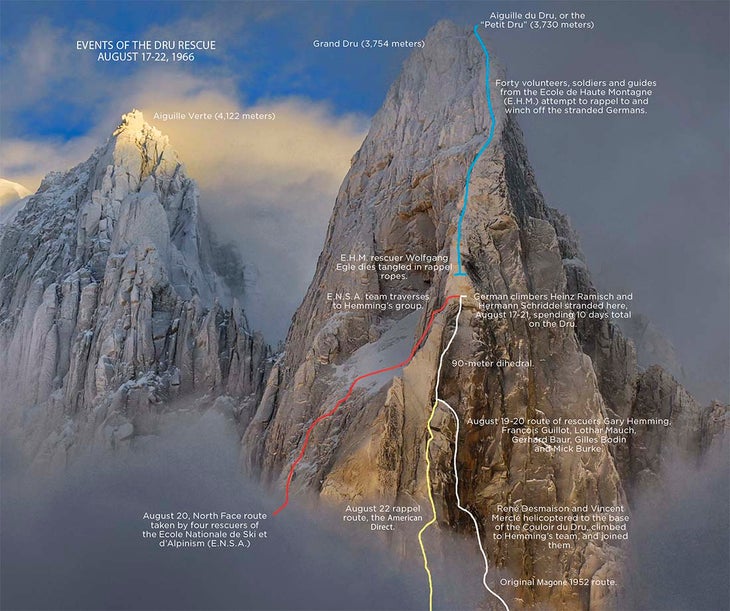

But the six men were not assembled to climb the Petit Dru—they were to save two young Germans who were ensnared on a ledge, unable to retreat, and unable to continue climbing. Verglas coated the entire wall. A helicopter had flown over the mountain on the 17th, and spotted the Germans through the clouds. They were alive. Forty rescuers had been dispatched to the summit of the Dru, but massive overhangs made it nearly impossible for teams to rappel to the stranded men.

The sole American on the glacier, and part of a second rescue team, was a tall, angular man with patched climbing knickers and a scarf nearly as long as he was. His face, one journalist later wrote, “had something of the beauty of the paintings of the Christian saints.” His eyes, an impish, childlike blue, twinkled when he smiled. In a few days he would be one of the most famous people in Europe. In three years he would be found dead in a campground in Jackson, Wyoming. His name was Gary Hemming, and he carried with him a conviction that in turn carried the five other soaked climbers upwards in the gray predawn drizzle. They would save the men who were trapped, thousands of feet above, by climbing up through the storm.

***

In a range rich in iconic summits, the Drus—the Grand and Petit—stand out. While both are spectacular summits, it was the Petit Dru, at 3,730 meters (24 meters shorter than its taller counterpart), that caught the eye of Chamonix alpinists. Its North and West faces are both steep, imposing walls of granite nearly as tall as El Capitan in Yosemite. It wasn’t until after World War I that alpinists even considered the faces possible.

***

In 1935, the first ascent of the North Face fell to Pierre Allain and Raymond Leininger. Allain was, in the words of the climbing chronologist, Ian Parnell, “decades ahead of his time.” He invented equipment still used today: lightweight half-height sleeping bags, inflatable mattresses and the first modern rock shoe. Allain honed his skills on the boulders of Fontainebleau outside of Paris, unlike many cloistered traditionalists of his era. His equipment, training and approach were, for 1935, breathtakingly modern. On the North Face, Allain and Leininger brought one ice axe between them to save weight. They used a single 7mm rope, five pitons, six carabiners and a prototype pair of Allain’s rock shoes. The pair freed the entire climb at 5.9. In 1935, and perhaps still, it was an absolute tour de force.

The first ascent of the neighboring West Face, in 1952, was such an undertaking that Guido Magnone, one of the first ascensionists, wrote an entire book about the endeavor. The signature beauty of the climb lay in the perfect, 90-meter diedre, a dihedral of granite high up the face. On the first attempt, Magnone, Lucien Bréardini and Adrien Dagory, exhausted from the oppressive heat and short on equipment, dead-ended above the dièdre, where blank slabs gave way to a 30-meter overhang. On their second try, the team, this time with Marcel Lainé, traversed in above the dihedral by placing a line of primitive bolts (gulots), from the neighboring North Face, skipping the section of the West Face they’d previously climbed. This time the team committed to an irreversible pendulum traverse across the slabs and launched up the overhang. The route constituted the cutting edge of rock climbing for 1952. In the wet, icy conditions of 1966, however, the same features conspired to form something more sinister: the perfect trap.

***

“There is,” wrote the journalist Jeremy Bernstein, in a 1971 article for The New Yorker about rescues in the French Alps, “in the back of the young climber’s mind an awareness of the efficient rescue service in the valley—the realization that, if the worst comes to the worst, ‘on vous cherche.’”

Heinz Ramisch and Hermann Schriddel had set off up the Petit Dru on August 14, five days before Hemming’s team labored towards them on the Mer de Glace. Ramisch, a 22-year-old student from Karlsruhe, Germany, had never once climbed with the 30-year-old Schriddel, who worked as an auto mechanic. They had only just met, encamped with a cluster of their countrymen in the Montenvers campground.

Accidents typically leave a distinct trail of seemingly inconsequential mistakes. But then, alpinism is rife with instances— both of ascent and disaster—where small things go wrong, apparently unnoticed by the unlucky protagonists. A razor-thin line has always separated the brilliant from the bumbling.

Ramisch and Schriddel made average, but decent, progress up the easy lower two-thirds of the wall. Planning on two or three days on the face, the two pared down their bivouac equipment to the minimum standard at the time: waterproof anoraks and down jackets, as well as a rudimentary two-man bivy sack.

On the second day, Schriddel took a 30-foot leader fall, badly bruising his ribs. Ramisch’s throat, sore from dehydration, hurt so much he couldn’t swallow. Nonetheless, on the 16th, even after bivouacking through a violent thunderstorm, they started up the dihedral, ignoring the growing clouds and the ice now plastering the face. The decision to continue, instead of retreat, would activate the most complicated rescue in the history of mountain climbing. They made impossibly slow progress. Schriddel fell yet again, and Ramisch, who caught him on a hip belay, badly cut his hands. That afternoon, having taken all day to climb the signature 90-meter dihedral, the Germans committed to the pendulum. Here, they confronted two options: Magnone’s bolt ladder, leading to safety and the less difficult North Face, or continuing up the horribly iced-up overhangs to the summit. Before the team had left Montenvers, they had agreed to wave a red parka in case of trouble to their anxious countrymen below.

After another bivouac, this time on the impossibly exposed ledge beneath the roofs, unable to commit to either the icy overhangs or the old bolt ladder, and certainly unable to reverse the pendulum and rappel, the exhausted Germans made themselves as comfortable as they could, took off the red jacket, and furiously signaled for help.

***

Lother Mauch was frustrated. It was Thursday, August 18. The rain drummed down on the café roof in Courmayeur, on the Italian side of the Alps. He had just retreated from the mountains, and now the weather was getting worse. Mauch, a 29-year-old German with handsome, dark features—he occasionally funded alpine-climbing trips with modeling gigs for fashion magazines—had been planning on an ascent of one of Chamonix’s longest routes, the Peuterey Integral. Across from him, reading that day’s Dauphine Libéré, a French paper, sat Gary Hemming, Mauch’s partner and mentor. The pair had made numerous ascents together: “Gary taught me everything during two summer seasons, when I climbed mostly with him,” Mauch remembers.

***

With Hemming, nothing was as it seemed. Hemming was born in 1934 in Pasadena, California, but when he became famous, he loved toying with reporters and friends alike, mischievously lying about his age, his height, his history. In his obituary, Royal Robbins would describe him as “a climber widely believed to have been among the best in the world.” Yet he climbed well only sporadically, often moodily lapsing into a listlessness that caused his abilities to suffer as much as his partners. Tom Frost, who climbed a new route with Hemming, John Harlin and Stewart Fulton on the Aguille de Fou in 1963, tells me that “his limitations were personal, not physical. He just wasn’t that stable a personality.”

For Hemming, as for others of his generation, alpinism was more a crucible than a sport. He told an admiring reporter from Elle after the rescue: “The mountain is an initiation which is renewed every year. You go there, you test yourself, you find yourself again. Afterwards, you are more able to accept yourself.”

Though Hemming had climbed with Robbins and Frost—men who practically invented modern climbing—he lingered only on the fringes of Yosemite in the late 1950s. His ramblings, from the late 1950s to the early 1960s, took him from Wyoming to Mexico, to British Columbia, to New York City: an early prototype of the dirtbag. Beginning in the summer of 1959, Hemming gravitated towards the Tetons, where he worked as a guide for Exum Mountaineering.

Mercurial even at his best, Hemming was legendary in his moodiness. He exploded into fits of rage, often against inanimate objects. Partners recall how his moods and tempers would affect his climbing. “He was very temperamental,” remembers Konrad Kirch, a friend of Hemming’s and a climbing partner of John Harlin’s. “And he was very fluctuating in his abilities.” Hemming, stalk thin and around 6-foot-4, would often provoke fights he knew he’d lose. Once, he was badly beaten outside a bar in the Tetons by three cowboys he’d been glowering at through his noticeably long, tangled hair. “Death,” he wrote in his diary, “is chasing me in this country. I have to leave before it catches me.”

In 1960, Harlin, an American Air Force pilot stationed in Germany, wrote to Hemming, whom he’d climbed with back in California in 1954. Hemming, attracted by the allure of the European Alps and sickened by the perceived restraints of American society, soon joined him.

While both men had made little ripples on the fringes of climbing development in California, they made quite the splash in Europe, bringing Yosemite tactics to the large, glaciated mountains of the Western Alps. Apart from a new route on the Fou, Hemming completed the first American ascent of the Walker Spur of the Grandes Jorasses, and the American Direct on the Petit Dru, with Robbins in the summer of 1962. (The Direct, as luck would have it, joined the original West Face route at the 90-meter dihedral where the two Germans now found themselves trapped.) Though Hemming climbed with others, it was with Harlin that he felt most strongly the electrifying power of partnership. And while they would argue, notoriously berating each other as they dangled from some precarious belay, they quickly became the most famous Americans in the Alps.

Guided by Hemming’s fatalistic, medieval sense of chivalry, the two were part and parcel to some of the Alps’ most famous rescues. Rescue duties at the time were divided among three groups seasonally— the École Nationale de Ski et d’Alpinisme, or E.N.S.A. (the guide-training school of France), the guides themselves, and lastly the École de Haute Montagne (the training school of the French Alpine troops). Help from talented “recreational” alpinists such as Hemming and Harlin was a necessary addition, but not always welcome. “Gary never liked the Chamonix guides,” says Lothar Mauch. The rift had begun when Hemming and Harlin offered their assistance during the famous disaster on the Central Pillar of Freney in 1961. The ordeal killed four out of seven climbers, and left the two Americans disenchanted over the lassitude of the French rescuers. This rift deepened when Hemming was booted out of an E.N.S.A. course in 1962 for refusing to shave his unruly beard. Later, he shaved it off all the same.

Hemming’s stubborn romanticism plagued him even more in the lowlands. His love life was plentiful, but abysmal. By 1966, he’d amassed a tangle of relationships that were complicated even considering the decade. He had a son with a Frenchwoman in 1963, and the couple maintained an open relationship. But he had also fallen in love with a young French student to whom he prescribed unrealistic expectations and mythic proportions.

When the two met, the woman was 17 years old. Hemming pestered her with hundreds of letters. He climbed over the hedges of her parents’ house in Paris. Her sister, unamused, promptly phoned the police, and Hemming was arrested. Hemming’s beatnik predilections baffled most of his American contemporaries. Frost muses, “He was portrayed as a romantic in the media. But, he wasn’t willing to step up to the plate to be a father or a husband.” For the French, who have always gathered rebellious spirits to their collective bosoms—from Joan of Arc to Arthur Rimbaud—the man brooding in the café with Lothar Mauch on that rainy day in August could not have been better poised for stardom.

John Harlin’s obsession was a route up the North Face of the Eiger in winter. By winter of 1966 he had made multiple attempts over five years, and finally recruited a team of alpinists whose names read like a who’s who of alpinism in the 1960s: Englishmen Chris Bonington and Don Whillans, the Scottish climber Dougal Haston, and the brilliant American Layton Kor. But the attempt had ended in disaster on March 22, as Harlin ascended a 7mm rope halfway up the face. The tiny perlon cord wore over a sharp edge, and Harlin fell. The journalist Peter Gillman, on assignment for the Daily Telegraph, watched in horror from Kleine Scheiddeg through his telescope. “Suddenly I saw a figure in red cartwheeling downwards. It fell too fast for me to follow it.”

[Also Read John Long: The Jump | Ascent]

Five months later, as Hemming read the Dauphine Libéré in Courmayeur at noon on August 18, he was doubtless still reeling from Harlin’s death. “John is one of my dearest friends,” he wrote in his diary. “His death I refuse to accept and so far as I am concerned he is still very much alive … I cannot climb alone next summer.”

The article that interested him involved the two Germans, trapped high up on the Dru, on terrain he was intimately familiar with. The École de Haute Montagne had dispatched some 40 troops to the summit of the Dru, orchestrated from Chamonix by Colonel André Gonnet. The plan was to lower a steel winch down and haul the stranded climbers back up. An Allouette helicopter had buzzed past the Germans, and through the clouds confirmed they were alive, but with the atrocious weather, could do little else.

With the rescuers came the press. “Every newspaper in Western Europe carried details of the rescue on its front pages,” wrote Bernstein in The New Yorker. A helicopter from the O.R.T.F., the official French radio and television network, joined the fray. The Petit Dru had been besieged.

Mauch took a little convincing before he would go with Hemming. “Gary said, ‘If they do it like that, trying to go down from the top of the Dru, they might never get them out.’ He knew very well about the overhangs on the West Face,” he says.

But the tunnel from Courmayeur to Chamonix was expensive, and the two climbers had just paid the hefty fee. Hemming pressed—what better crusade than a daring rescue? He would recount in an ensuing Paris Match article: “This rescue is a great ascent—a real adventure. But what’s important is that it involves the lives of two persons, two companions. If we make it, it will mean a lot more than just another windy summit, don’t you agree?”

Eventually Mauch agreed to return to Chamonix, and to accompany Hemming up the Dru. “It was bad weather,” he reasons, with the logic of any obsessed alpinist. “There was nothing else to [do].” Hemming’s plan, to reach the Germans by climbing up to them and rappelling, seemed simple enough. But rescues in Chamonix were overly complicated affairs, and to rappel a face that huge was still daunting, given the techniques and equipment of 1966. “The rescue organization,” says Mauch, “was very, very bad at the time.”

At 3 o’clock on the afternoon of the 18th, Mauch and Hemming introduced themselves to Colonel Gonnet, who, to his great consternation, realized he was suddenly parlaying with the same upstart American who had been kicked out of E.N.S.A. for refusing to shave.

A man wholly different from Gary Hemming was also paying particular attention to the unfolding saga on the Petit Dru. René Desmaison was one of the best alpinists in France. The 36-year-old had made the fourth ascent of the West Face of the Dru. Unsatisfied, he completed the first winter ascent of the line, and then returned to solo it. In 1958, he and Jean Couzy climbed a new route on the north face of the Grandes Jorasses. He was a member of Lionel Terray’s expedition to Jannu in 1962. Perhaps only Walter Bonatti exceeded Desmaison in ushering in the new era of modern European alpinism.

Unlike Hemming, who flitted between bohemian dalliances and climbing with a calculated nonchalance, Desmaison was an obsessive career alpinist, and one of the foremost guides in Chamonix. And like many professional climbers desperate to fund their endeavors, Desmaison possessed a canny ability to manipulate his adventures and present them—for a cost—to the mainstream media. “He had a reputation in Chamonix,” remembers Mauch, “for working with Paris Match and the radio station.”

In Desmaison’s defense, alpinists with middling bank accounts have always relied on publicity stunts to fund their endeavors. Harlin’s death on the Eiger had received massive coverage; the French magazine Paris Match had taken to keeping a full-time correspondent on hand in Chamonix during the busy summer alpine season in order to snatch up rescue stories as quickly as hapless climbers could ascend into trouble.

Like Hemming, Desmaison realized that climbing up to the Germans was the surest method of rescue. He decided, without informing the world’s oldest organized mountain-guiding association and his employer, Chamonix’s venerated Companie des Guides (who hadn’t yet ventured forth a rescue effort), to strike off up the West Face to save the Germans.

“Amateur or professional,” he wrote in Total Alpinism, “any climber has the right, indeed the duty, to save life.” What he neglected to reveal, in his chapter on the Dru (entitled “The Maverick”), was the exclusive contract he signed with Paris Match before setting off.

François Guillot, another young alpinist, was drinking a beer and watching the rain in the Hotel de Paris when he saw Mauch and Hemming. Hurriedly, they explained their plan. Within hours of the meeting with Gonnet, Hemming had assembled an improvised team of rescuers: Gerhard Baur was a young German in his early 20s who knew Ramisch and Schriddel. Gilles Bodin was a French guide. Mick Burke, who Konrad Kirch remembers as a “small, dirty- looking climber,” was a talented Brit who would later go missing on the South Face of Everest. He was also crucially well versed in knowledge of the West Face, having rappelled the American Direct, Robbins and Hemming’s line, when his partner had broken an arm due to rockfall.

But Guillot was the lynchpin. At 22, he was one of the youngest rescuers, but also one of the strongest. “I was a pure amateur at the time,” he laughs. “I was coming off a six-week trip to the Caucus mountains. So I was in good shape. Gary knew me, and knew I was a decent climber, and asked me to come.”

By 7:00 that evening, Hemming and his team were on a specially scheduled cog- railway train headed up to the glacier. Early the next morning, the men climbed up the Dru Couloir, an inhospitable place in the best of conditions. Now, as sleet spat down, the couloir was a death trap, and the men, laden with heavy rucksacks and soaked already to the bone, resorted to every trick in the book to make upward progress. In the snow and sleet, the slabs and ledges proved impossible. Guillot led a few pitches and then retreated back down, and the men huddled into their down sleeping bags and two-man bivy sacks, little better off than the Germans, who remained crouched on their teeny ledge, rationing nuts and shivering through their fourth night in the same forlorn spot.

Meanwhile, Desmaison and an aspirant guide and photographer named Vincent Mercié, had taken a helicopter to the base of the couloir and were soon also dodging the fusillade of stones and debris. The two Frenchmen hunkered down for the night on a sheltered ledge, unable to cross over to Hemming and his team until morning, when the cold had frozen the couloir enough to allow safe passage. In the morning, Baur tossed Desmaison a rope. The two parties converged. Now they were eight. What went through Hemming’s mind as Desmaison and Mercié popped up on the ledge next to him? Desmaison, according to his own account, chastised the team for moving too slowly, and conjured a plan of action. “Gary knew very well that Desmaison was there for money,” says Mauch.

For Hemming, the helpless, troubled romantic, the Dru rescue glimmered as the spiritual crusade he had always dreamed of. For Desmaison, whose career suddenly hung in the balance, saving the Germans, and the race to beat his colleagues, meant everything. The idealist and the opportunist would now have to work their way together up the mountain as 10 million Europeans listened, read and watched the drama unfurl across the granite of the Dru.

“Desmaison wanted to do the rescue to take pictures, to sell the pictures to Paris Match, and you could speak for hours about that,” Guillot says. “However, he was perfectly in line with his approach, and he was a professional alpinist.”

They came up with a plan of action. Guillot and Hemming would go first, Desmaison and Mercié second, and Mauch, Baur, Bodin and Burke would tackle the less glamorous but equally daunting task of hauling the heavy rescue and bivouac equipment up the verglassed face.

That Hemming and Desmaison, not exactly slouches when it came to alpinism, allowed the young Guillot to lead the entire West Face speaks more to the 22-year-old’s abilities than anything else. Bodin recalled in an interview in 2002, “Without Guillot, we may still have succeeded. But, it would have taken twice as much time.”

Hemming belayed as the young Frenchman furiously hammered his way up the West Face. Word had gotten out about the tall, valiant Californian racing his improvised team up through the clouds. Even if he was only feeding out rope, the press was in love. Less enamored was the Companie des Guides with Desmaison. For the stoic clique, Desmaison’s latest publicity stunt constituted the final straw.

There were now three rescue groups on the Dru. The École de Haute Montagne’s 40 volunteers, soldiers and guides on the summit were still attempting to lower a steel cable down to the Germans. E.N.S.A. had finally sent its four alpinists to climb Pierre Allain’s route on the North Face, and Hemming and Desmaison’s team was about to reach the Germans by way of the original West Face route.

The three rescue entities were drawing closer to the Germans, and, as notably to the swarms of reporters below, to each other.

On Saturday the 20th, as Guillot led the climbers up the West Face, rescue efforts were compounding elsewhere, too. Four E.N.S.A. climbers—all colleagues of Desmaison’s—had begun climbing up the less-technical North Face, with the intent of traversing in on Magnone’s aged gulots.

The eight men on the West Face bivouacked below the dièdre. Now they were a mere 300 feet below the two Germans. In one day, through ferocious storms, Guillot had led what had taken Ramisch and Schriddel two days the week before. Around the corner, the E.N.S.A. party bivouacked at around the same height. Hemming shouted to the Germans through the mist, but could hear nothing.

Everyone settled down in the dark. Their sleeping bags and clothes were soaked completely through. The next morning, the Germans responded to Hemming’s shouts, and the rescuers attacked the dihedral. Simultaneously, the E.N.S.A. team began traversing in from the North Face. Higher up, Gonnet’s men were still trying to lower a steel cable from the summit of the Dru. They had enlisted the help of some volunteers, including a young man named Wolfgang Egle, a friend of the Germans, who was rappelling above the four E.N.S.A. climbers when he somehow became tangled in the ropes on the icy north face and was strangled to death.

Desmaison remembers the incident in Total Alpinism: “Luckily, this tragic occurrence was invisible from the West Face and, naturally, we did not mention it to the two Germans.”

Guillot and Hemming reached the stranded German climbers a little after noon on Sunday, August 21—a full week after Ramisch and Schriddel had started up the face. Apart from the minor injuries sustained while climbing, and the obvious hunger, cold and exhaustion, they were fine.

As Hemming reached Ramisch and Schridde, Yves Pollet-Villard, one of the guides on the E.N.S.A. team, was making the traverse across Magnone’s gulots. Pollet- Villard was a colleague of Desmaison’s. Moreover, the two had climbed on Jannu together, and routinely roped up around Chamonix. Understandably furious at Desmaison’s decision to rescue the Germans himself, without prior consultation, he now asked the renegade West Face team what their intentions were.

Guillot remembers thinking that, hubris aside, Hemming and Desmaison’s plan was the safer of the two. The ropework involved with ferrying the two exhausted Germans up and across to the North Face was doable, but complicated, and dangerous considering the Germans’ deteriorating condition. Burke and Hemming’s knowledge of the American Direct, which shot down from the ledge in a perfect line, was the safest option.

“At that time,” says Guillot, “rappelling down a 900-meter-high face was something enormous. And certainly for Desmaison, and also for Gary, it was a question of pride. They wanted to keep the two Germans with them, and not give them to the other team. And this created a lot of problems for my friend Desmaison after that.”

One of the North Face rescuers fuming at Desmaison and Hemming’s insolence was Gérard Devouassoux. Five years later, in February 1971, Devouassoux would be charged with rescuing Desmaison and his young partner Serge Gousseault from the top of the Grandes Jorasses after the exhausted climbers had become stuck at the top of a new route. By the time the rescue arrived, Gousseault was dead, and Desmaison was barely alive. Desmaison would accuse the rescuers of intentionally dragging their feet to punish him for his role on the Dru rescue while Devouassoux and the other rescuers would claim that Desmaison’s need for the spotlight—he hauled heavy radio equipment up the wall so he could broadcast daily updates—had caused him to climb too slowly.

Today, many Chamoniards still whisper about Devouassoux’s “revenge,” though few are willing to comment on it publicly. On the ledge in 1966, Guillot, uninvolved in the older men’s weighty quarrels, chimed in, asking for the guides to lower a stuff sack full of snacks.

Desmaison continues: “The cloud ceiling was now about 11,800 feet. The air seemed humid. In spite of the altitude it did not seem cold. It was obviously only a matter of time before the storm broke.”

A helicopter whirred past to snap photographs, and the team rigged the Germans with modern nylon harnesses and retreated to their last bivouac below the dihedral. That night, as the men prepared for the worst, another storm of insatiable violence lashed the West Face. The rescuers debated untying from the pitons, humming with electricity.

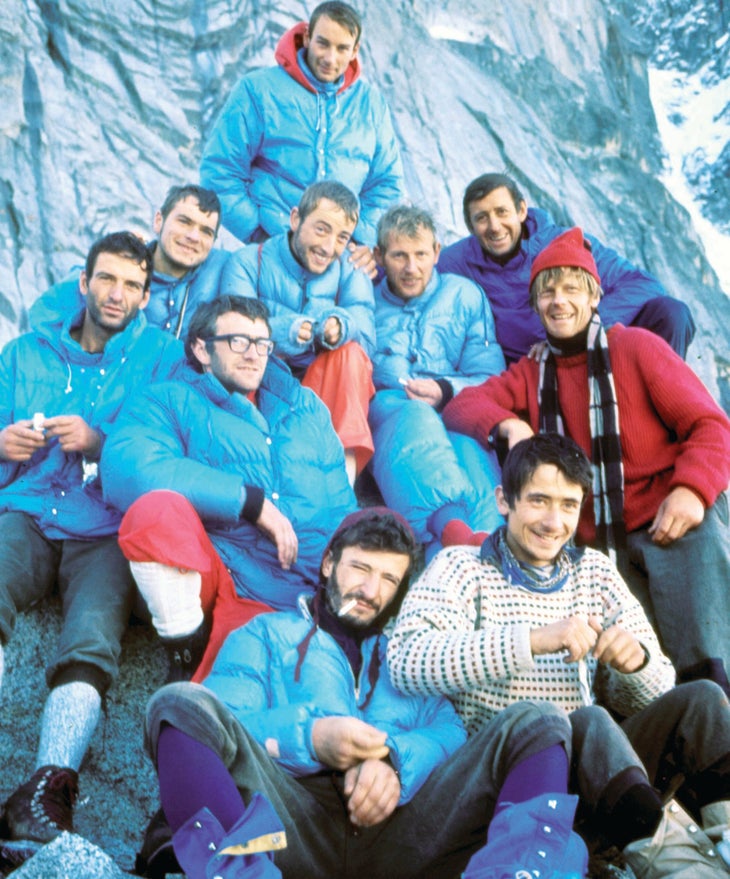

On the 22nd, Mick Burke led the team, and the rescued Germans, down the mountain, soaked, exhausted and elated. In the dark, they stepped onto the glacier. In the morning, when, observed Bernstein in The New Yorker, “The light was bright enough so that the O.R.T.F. television cameras could obtain excellent pictures,” the team was helicoptered back to Chamonix. In the black-and-white footage, Hemming appears a little tired. His pants are tattered and worn, and a red knit cap is perched at a perfect angle over his head. He laughs easily with the reporters despite his fatigue, throwing his head back at his own sardonic remarks. His French is good, with a slight American twang. When a reporter asks if he ever thought about giving up, he fixes his gaze: “Jamais. Jamais.” “He loved it,” Konrad Kirch remembers.

While they had toiled on the Dru, Desmaison had slyly hidden his contract with Paris Match from the other rescuers, but, back in Chamonix, he told an understandably livid Hemming. “Gary was not the type of guy who would make a big fuss about fighting with Réne,” says Guillot. “But, I’m sure it was a pretty tough discussion between the two of them.”

While the rescue elevated Hemming to mythic proportions, Desmaison’s actions caused the Companie des Guides to fire him instantly. He would spend the rest of his life feuding and feeling as if Hemming had gotten an unfair portion of the credit for the rescue. “Well done, Gary!” he wrote. “Gary Hemming was the hero of the hour, the man who had saved the two Germans, the man everybody wanted to touch, and interview, and see. You would have thought he had done the entire rescue single-handed; nobody showed the slightest interest in the rest of us.”

Guillot, who later became a guide, spent years quietly reading Desmaison’s increasingly exaggerated accounts of the affair. “René hid everything about the job we did,” he says. “In all his books he mentions the rescue, and each time his role grows, as if he’d done everything himself. I spent my life looking at what René was writing in his books and saying, ‘Bastard; he could have spoken a little bit more about my role!’”

While Hemming basked in the limelight and Desmaison tussled with the Companie des Guides, Lothar Mauch engaged in a heroism of a different sort. Two men had been saved; another young man was dead. The parents of Wolfgang Egle, the man who still hung from the North Face of the Dru, had come to Chamonix. Mauch remembers feeling uneasy. Devouassoux, the E.N.S.A. climber who had reached Egle moments after his death, had delegated the task of meeting the parents to Mauch. “He saw the guy dying before his eyes! I didn’t see anything,” says Mauch. “I was on the other side of the mountain. The parents asked me questions I couldn’t answer. It wasn’t right.”

After the hubbub subsided, a different sort of recovery took place, as rescuers somberly cut down Egle’s body and returned it to Chamonix.

In James Salter’s novel Solo Faces, which is loosely based on the life of Hemming, the title character successfully fades back into an anonymous, vagabond existence after his dangerous brush with fame. The real ending was less tidy. Hemming’s face had been seen on every television station in Europe. He wrote his own account of the rescue for Paris Match. He was put up in the Paris flats of intellectuals and journalists. He played a character on a French television mini-series. Women stopped him on the street. He was “le Beatnik,” with, as Salter puts it, “a saintly smile and the vascular system of a marathon runner.”

“Gary was uneasy and unhappy in the United States,” Robbins would write in his obituary. In 1969, as his celebrité ebbed, Hemming returned to the Tetons. He had taken, for some morbid reason, to keeping a revolver in his rucksack. Hemming’s idealism, which had so embodied the 1960s to his European fans, would be lost, seemingly in time with the tumultuous decade itself, which began with such innocence and ended in unfathomable violence. “Anyone,” he reportedly quipped, “can be a hero one day and a motherfucker the next.” On the night of August 6, 1969, he attended a party with his old friend Bill Briggs at the Jenny Lake Campground.

Hemming, who loved getting into fights he’d lose, needled one of the partygoers about the inferiority of American guides to their Gallic counterparts. The two scuffled, with the much-stronger Exum guide pacifying the wildly drunk Hemming. Later, Hemming quarreled with his girlfriend at the time, snatched his rucksack out from her car, and disappeared angrily into the night, firing a shot from his revolver into the air. Briggs, attempting to cling to much- needed sleep before he met his clients in the morning, heard a second shot at some point during the night. “I recall thinking probably Gary had committed suicide, or perhaps shot the girl.” In the morning he found Hemming’s long body, splayed out in the grass.

***

Desmaison’s Accident on the Grandes Jorasses and the death of Serge Gousseault put him even further at odds with the Chamonix establishment. He constantly warred with the guides he swore abandoned him. Whatever his earthly motives, his routes are considered among the greatest in the Alps. A modern alpinist, Jon Griffith, wrote on his web page after repeating Desmaison’s pièce de résistance on the Jorasses: “Among all the hundreds of classics … there will always remain … the ones that combine five star climbing with an epic tale enshrined in our sport. The Desmaison-Gousseault is one of them.” In 2007, Desmaison died at the age of 77.

Mauch, Guillot, Baur and Bodin are still alive. When I spoke with Mauch, he was in Spain, enjoying the sunset after a day of clipping bolts. He and Guillot are still friends, having met in the bar that rainy night in the Hotel de Paris, over 50 years ago. I chatted with Guillot, who was spending time in Marseilles. His shoulders, he complains, are giving him trouble. In his mid-70s, he still climbs 5.11 (5.12, according to Mauch). “Gary had the fame,” he told me. “And that’s O.K.”

Most of the rescuers turned toward inevitable careers in the mountains. Gerhard Baur became a successful mountain filmmaker. Guillot and Bodin spent lifetimes guiding in the Mont Blanc Massif, though the fame and prestige awarded the rescuers eventually faded. “Ask the youngsters, and you will see there are not so many who know!” Bodin joked in a 2002 interview.

It is difficult to directly connect Desmaison and Gousseault’s tragedy on the Grandes Jorasses with the rescue, but in a town where politics and climbing are tied so tightly together, not impossible. Hemming, turned celebrity overnight, unraveled over his three remaining years. His diaries constantly question his fame. “Now I know with certainty the impossible situation of being ‘somebody important,’” he wrote. While the other rescuers simply became dramatis personae, and a mountain rescue became a confounding muddle of egos, the survivors are probably relieved to have remained relatively anonymous: the two men who gained the most from those stormy days on the Dru suffered in accordance with their fame.

Michael Wejchert is a writer and guides for the International Mountain Climbing School in North Conway, New Hampshire.

This feature article was first published in the 50th anniversary edition of Ascent in 2017.

The post 10 Million People Watched The Dru Rescue. The Media Created Heroes And Villains. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

River Barry, a climber in the right place at the right time, leads a daring rescue of a BASE jumper stranded high on a cliff.

The post How This Climber Rescued an Injured BASE Jumper from Cliff appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Out Alive is a podcast about real people who survived the unsurvivable. Check out more seasons and episodes here.

This episode contains graphic content that may not be suitable for all listeners.

River Barry, a climber in the right place at the right time, leads a daring rescue of a BASE jumper stranded high on a cliff. Read here.

Transcript

Host: Most of us view our outdoor adventures as something we do for ourselves. While not necessarily solitary, we climb those peaks, scale those walls, and sleep in the dirt for our own benefit. Some practitioners of more extreme sports like climbing, high-alpine expeditions, and BASE jumping are even accused of selfishness.

This refrain is all too common after an athlete’s untimely death in the mountains. But for the majority of us, we balance our tolerance for risk by acquiring the necessary skills to keep ourselves safe. We practice our knots, self arresting, and first aid in order to protect ourselves and our partners, but without much thought for the greater good.

But the skills we’re quietly mastering with each expedition can turn into superpowers. When a crisis arises, we might just find that the resume we’ve been building makes us exactly the right person to help a stranger in need.

Trailer

River: My name is River Barry. I’m a mental health therapist. I have a passion for the outdoors. I used to work in wilderness therapy, so a lot of crisis response and emotional first aid happening there.

Justin: My name is Justin Beitler. I’m based in Las Vegas, Nevada. I’m a bass jumper and a pilot.

River: I would say that I love climbing more than anything else. I do. I started logging climbs in 2019, but I don’t just climb. I like to rotate sports. So in the warmer seasons, I’m mountain biking and route climbing, and then in the colder seasons, I’m ice climbing and splitboarding.

Justin: I was in Moab for Thanksgiving. A bunch of friends and I had gone there to go BASE jumping.

And if you don’t know what BASE jumping is, it’s jumping with a parachute. But instead of jumping out of an airplane, you jump off of a fixed object. So a BASE is actually an acronym that stands for Building Antenna Span (being a bridge) and Earth (being a cliff).

Host: Moab, Utah is an outdoor enthusiast’s mecca.

Although the town itself is only 5 square miles, cooler months bring an onslaught of adventurers due to its proximity to endless miles of desert hiking, mountain biking, canyoneering, rock climbing, whitewater rafting, dramatic red rock scenery, cheap camping, and two national parks. The week of last Thanksgiving, Justin was in town during the annual local BASE jumping festival: Turkey Boogie 2022.

And River was visiting Moab after having spent some time climbing in nearby Indian Creek, one of the most iconic desert climbing destinations for signature crack climbing on sandstone towers.

River: I had just left Indian Creek that morning. We were driving out, one of my really good friends came down. She doesn’t really climb too much; we decided we’re gonna go to King Creek and hop on some bikes and get some riding in.

So we had just rolled up, and we were in the parking lot. We were gearing up, got my knee pads on. I had already moved my chain,

Justin: and one of my friends called and they’re like, “Hey, do you want to come on this jump with me?” And I’m saying, “No, I’m really tired.” And they go, “We really want you there. It’ll be a lot of fun if you came.” And I had to roll my eyes and just like, “Fine, I’ll go do this jump.”

Host: The Kane Creek trailhead where River was planning to start her bike ride is also adjacent to a very popular BASE jumping area. From the parking lot. Bikers and hikers can watch people huck themselves off the cliffs above and parachute down to the ground. At the same time River was gearing up, a group of BASE jumpers had assembled at the top of the cliff, including Justin and another one of his friends who was visiting from Australia.

Justin: We get up to the top of this jump and everyone starts putting their gear on and going through the normal rituals. If you’ve never been on a BASE jump before, it’s just an interesting dynamic of all the things that take place before you go on this jump. Everyone, I think, wonders how do you figure out who’s gonna go first?

What is it like? It’s really tense. You’re all about to jump off of this cliff, which is a little bit of a crazy thing to do. It’s really scary. Generally, everyone’s just kind of terrified and walking around. pretending like they’re not terrified, but everyone knows everyone else is terrified.

River: I was doing tire pressure; everything was ready to go. Literally we’re about to pedal away, type of deal.

Justin: I kind of lined up, did the jump. Everything felt good. Right after you open your parachute, your mood changes from being terrified to just being super ecstatically happy, like you survived some big traumatic event or something.

I’m celebrating on the way down. Right about that time, I looked up at the cliff to see my other friend jumping, and you knew right away that it wasn’t gonna be good. When you’re jumping with a parachute off cliffs, there’s only a few things that can really go wrong. One of them is your parachute opening facing the wrong direction.

You need to try to respond quickly and turn the parachute and turn it away from the cliff and fly away from the cliff. The problem is we really don’t have much time to do that. The only distance that you have from the cliff is how hard you ran off of it or pushed off of it, and you might have a couple seconds to try to reach up, get the controls of your parachute.

His parachute opened backwards and it spun his body just a little bit. When he reached up, his controls weren’t in the spot where he was expecting them to be, and so he hit the cliff and he hit the cliff pretty hard. And so now you’re in a position where your parachute’s still trying to fly forward into the cliff and it can’t do that.

So it just rags down the cliff all the way toward the ground, and then his parachute caught on a sort of an outcropping of rock.

River: This person is hanging up in the air just delicately. It looks fragile, the situation. And I remember so vividly. Instantly praying, like I don’t really believe in organized religion, but I’m a very spiritual person and I just say, Great Divine, please help this person.

In no way did I think that I was going to be part of it, really at that point in time because I just didn’t understand how I could be part of it.

Host: The Australian BASE jumper was dangling about 80 feet up the cliff wall held only by his parachute, which had snagged on a ledge.

Justin: It’s time to get into gear and start helping. So I put all my gear down and I just started running up to the cliff. I don’t even really know what I thought I was gonna do, but I just felt like I needed to get up there. I needed to start gathering information and figuring things out. I see my friend up there, he’s not moving, not moving at all, and the first thought that I had was, he may be a goner.

It was really kind of a scary moment that you didn’t hear anything, you didn’t see anything. My brain just kind of went into this mode of gathering resources. I have a friend that has a rope. I have another friend that’s got some harnesses. The one thing that we don’t have that we really need is some trad gear, some rock climbing gear.

Host: Justin thought that in theory someone could climb up the rock to his friend, but without trad gear or pieces of hardware that a climber places in the rock, they had no way to protect against a fall.

Justin: Right about that time, one of my other buddies arrived on the scene and I told him, “Okay, I’ve gotta, I’ve gotta go stay here with our friend. If he wakes up, keep him calm, tell him not to move, he can’t move around too much, or he might fall.” And that was really the thing I was worried the most about this. I didn’t know what was holding him up. If he moved around, maybe that parachute’s gonna slip, and he might fall.

River: And then all of a sudden a stranger just runs up to me; he’s standing by my van and he just starts asking, not just me, but everybody in the parking lot. “Does anybody have rock climbing gear?”

Justin: And that’s when this girl just piped up from across the parking lot, “Okay, I’ve got gear. What do you need?” And that was River.

River: I had a double rack. I’d just come from Indian Creek plus I had my van of all my things and I had a couple harnesses and what used to be a 70 meter but now is a 69 meter rope and grabbed all my gear, put it in a creek pack and he just took the pack and ran away.

It was crazy. Now I think about it and I’m like, “I just gave a stranger thousands and thousands of dollars worth of my gear. That’s crazy.” And he was just, “Meet me up there and at this time.” I’m like, “This dude must be some crusher trad climber, and he’s gonna go save this dude. I’m gonna go to belay him and help out.”

I had this instinct to just run with him, but then I was like, “Wait a second. I’m in biking gear. I need to take a minute to breathe and put on climbing gear and pack some food, some water, a puffy, first aid stuff.” Just take a minute to make sure I was taking care of me also, so I could help out in the best way possible.

I had not even gotten Justin’s name yet, but the stranger that I had briefly met in the parking lot was there, and I was just like, “Okay, cool. We’re gearing up.” I get everything out of my pack. “I just wanna let you know this is what my climbing resume looks like. I just want you to know I’m a safe belayer. What’s your resume look like?”