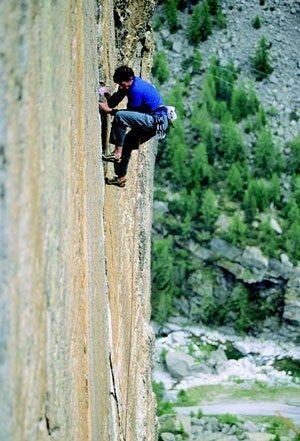

Even in summer, the 1,250-meter 5.11b is serious: endless crack systems, polished dihedrals, and off-widths on flawless granite. In winter, it's a completely different beast.

The post Interview: the First Winter Ascent of Cerro Chaltén’s North Pillar appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

On September 7, at 2:30 in the afternoon, Italians Matteo Della Bordella and Marco Majori stood on the summit of Cerro Chaltén—better known as Fitz Roy—hugging in triumph. They had just completed a historic milestone: the first winter ascent of the legendary line envisioned and soloed by Renato Casarotto back in January 1979.

A legendary line

Casarotto’s visionary route—35 pitches, 1,250 meters, up to 5.11b—traces the striking North Pillar of Cerro Chaltén, nearly 1,000 meters of soaring granite itself, before continuing up the upper wall to the summit. He named it “Pilar Goretta,” after his wife. Even in summer, the climb is serious: endless crack systems, polished dihedrals, and off-widths on flawless granite. In winter, it becomes something else entirely—endless storms, freezing ropes, cracks filled with verglas, and tents shredded by Patagonia’s infamous winds.

Reflecting on that solo ascent, Casarotto wrote in the American Alpine Journal: “On this wall I had to overcome extreme technical difficulties in the presence of continuous bad weather. This adventure confirmed to me that to succeed on very difficult climbs, it’s essential to integrate with the environment, to identify the right moment so your physicaCll and psychological energy is not wasted in long waits.”

Several teams have repeated the 1979 route, and often with variations. Colin Haley, the only other climber to solo it—and the first to do so alpine style, in 2023—called Casarotto’s achievement “incredible… in an era with no forecasts, no satellite communications, no LED headlamps, no camming devices.”

A first taste of Patagonian winter

For all three members of the Italian team—Della Bordella, Majori, and Tommaso Lamantia—this was their very first winter expedition in Patagonia. Despite Matteo’s deep experience (five Cerro Chaltén ascents and countless other Patagonian climbs), he admitted he didn’t know exactly what awaited them. “The chances of success were extremely slim,” he told me.

Arriving in El Chaltén on August 5, they didn’t hesitate. A rare good-weather window opened, and the team shouldered 55-pound packs and slogged through deep snow to the base. On August 7, they launched their first attempt, climbing halfway up the pillar before fierce winds forced a retreat on August 10.

“It was incredible,” Della Bordella recalled. “The cold, the fatigue, the absolute solitude—and at the same time, exhilarating. Pitch by pitch we grew more confident that it was possible.” Daytime temperatures barely reached 40°F; at night, they dropped to –5°F, with winds biting even harder.

Although they retreated, the team came back to town energized. Della Bordella stressed that his guiding principle was to never burn himself out on any given day, to always leave enough energy and clarity for a safe retreat if needed. His words echoed Casarotto’s decades-old wisdom.

But Patagonian weather has little mercy. Storms pinned them down through late August, and Lamantia had to fly home, disappointed to miss the final push. “It wasn’t easy watching from afar,” he admitted, “but I’m grateful for what I experienced. I made it halfway up the pillar. I didn’t get the cherry on top, but it was still an incredible adventure. As a photographer, I hope my work helps tell the story in a future documentary.”

The final push

Patience is one of Della Bordella’s greatest strengths. He relied on a longtime friend back in Italy for weather forecasts—and this time, the prediction was perfect. With lighter packs and the benefit of experience, Della Bordella and Majori reached the base in half the time of their first attempt.

At dawn on September 5, Majori led the first mixed pitches, ice tools and crampons scraping on the granite. Then Matteo took over on the steep, technical cracks he knew so well. They bivouacked under the giant Bloque Empotrado, wedged between Pilar Goretta and Aguja Mermoz. The next day they completed the pillar and bivouacked again on the snowfield at its top, preparing for the final wall. On September 7, exhausted and frozen but unwavering, they stepped onto Cerro Chaltén’s 11,171-foot summit.

Majori’s circle comes full

For Marco Majori, this climb was more than just a technical challenge. Just a year earlier, he had barely survived a crevasse fall on K2 during an ambitious no-oxygen ski descent attempt. He clawed his way out alone, in terrible shape, and only survived thanks to the swift aid of fellow climbers. Though the physical injuries healed, the psychological scars lingered.

What motivated him to return to high-stakes climbing? Family history. His father, Giovanni Majori, had once been on an expedition with Casarotto himself but decided against attempting the pillar. A childhood photo of Casarotto—a tiny black dot at the base of the massive wall—stayed with Marco for decades. “This climb,” he told me, “was a circle closing.”

Della Bordella: The vision

Della Bordella and Majori already had a strong partnership, having opened a new route on Siula Grande (6344 m) in Peru the year before. But what stands out about Della Bordella isn’t just his technical mastery—it’s his character.

Time and again, partners describe him the same way: endlessly patient, deeply determined, but above all, extraordinarily kind. He is rigorous in style, visionary in pursuing exploratory objectives with low probability of success, and a natural motivator for younger alpinists. Talking with him, I realized how much of his strength lies in keeping morale high, in maintaining focus, and in nurturing a positive partnership even when the odds seem overwhelming.

At the end of our conversation, Della Bordella reflected on Casarotto’s example and the profound joy of retracing his steps up Pilar Goretta. “It made me understand even more,” he said, “the incredible vision, the effort, and the brilliance it took to make it happen back then.”

The post Interview: the First Winter Ascent of Cerro Chaltén’s North Pillar appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Cristian Brenna is remembered not only for his extraordinary climbing prowess but for his profound human qualities.

The post Cristian Brenna, Champion Italian Rock Climber and Alpinist, Dies in Fall appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Cristian Brenna, 54, a distinguished Italian alpinist, extremely talented rock climber, and mountain guide, tragically died on June 3, 2025, after an accident on Mount Biaina, near Arco. Around 11 a.m., while traversing a ridge at 1,350 meters (approximately 4,430 feet) with a companion, Brenna reportedly stumbled on the trail, slid down a wooded slope, and landed on rocks below. His companion, unable to reach him, alerted emergency services.

Swift rescue efforts involving an emergency helicopter, local Alpine Rescue, and colleagues from the Soccorso Alpino della Guardia di Finanza (SAGF) where Brenna served, were deployed. Despite attempts to revive Brenna by the medical team, his death was confirmed at the scene. This sudden and unexpected loss, occurring not during an extreme ascent but a non-technical descent, reminds us of the inherent risks in mountain environments, even for the most experienced.

Born in Bollate on July 22, 1970, Cristian Brenna started sport climbing at 15, joining the World Cup circuit in 1991. He achieved significant competitive success, including a World Cup Lead victory in Courmayeur (1998) and multiple podium finishes, reaching second overall in 1998 and third in 1996 and 2000. He also earned two European Lead silver medals (1998, 2000) and a Speed silver (1992), showcasing remarkable versatility. Domestically, he was a three-time Italian champion.

In 2005, Brenna retired from competitions to focus on exploratory alpinism. This transition from structured competition to the uncertainties of high-altitude challenges was a notable shift, but not a surprise for his partners. His first major endeavor was the “UP-Project” in Pakistan in 2005, where he opened and freed Up & Down (7c/5.12d) on the Chogolisa Shield at 5,000 meters (approximately 16,400 feet).

In 2003, he completed the first free ascent of Itaca nel Sole (8b/5.13d trad) in Valle dell’Orco. He also climbed Bellavista (8b+/5.14a; 450m) on the Tre Cime di Lavaredo with Mauro “Bubu” Bole in 2002. In February 2008, with Hervé Barmasse, he made the first ascent of La Ruta del Hermano (A3 6b+/5.10d; 850m) on the previously unclimbed Northwest Face of Cerro Piergiorgio in Patagonia, solving a long-standing alpine problem.

Beyond his climbing career, Brenna was a mountain guide (Guida Alpina), a rescuer with the Soccorso Alpino della Guardia di Finanza, and a national team coach for the Italian Sport Climbing Federation. He was also a member of the famous climbing club Ragni di Lecco.

He found mountains to be “Divertimento, passare bei momenti con gli amici e vivere esperienze intense” (fun, spending good moments with friends, and having intense experiences), emphasizing that true alpinists needed “La completezza e la polivalenza” (completeness and versatility). For Brenna, success was deeply personal, about feeling good about himself, not merely external recognition.

He leaves behind his wife, Jana, and children, Filippo and Sofia, the latter being a national climbing champion.

Cristian Brenna is remembered not only for his extraordinary climbing prowess but equally for his profound human qualities. He was described as an “inspiration, a symbol of pure passion, quiet strength, and dedication.” Online, friends and colleagues consistently highlighted his “perennial smile” and “joy for life,” describing him as “polite, sensitive, ironic, and humble.”

I reached out to veteran climber Riki Felderer, a close friend, who expressed the profound void left by Brenna’s passing. Felderer struggled to find words that weren’t clichés to describe him, believing “a book wouldn’t be enough to tell his story.” This story, he felt, would be “made of anecdotes, great deeds, and small stupidities that would describe a special man, far from perfect, as in reality no one is!” But most importantly, “he was a friend.”

Fabio Palma, former Ragni di Lecco President, recalled Brenna’s immediate, friendly greetings. Palma says Brenna was known for his strong ethical principles, including a disdain for “meritocratic injustices and complaining about fatigue.”

Lucia Furlani, a young climber he coached, described him as “much more” than a coach—”a guide, a concrete example to follow, a point of reference.” His ability to listen and support built a “true, sincere bond.” Through his teachings, he instilled “grit and desire,” encouraging them to win “those [battles] against ourselves.” Brenna’s strength, they affirmed, would live on “in every beat of our heart.”

Federico Bernardi thanks Riky Felderer, Fabio Palma, GognaBlog, and Lo Scarpone.

The post Cristian Brenna, Champion Italian Rock Climber and Alpinist, Dies in Fall appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

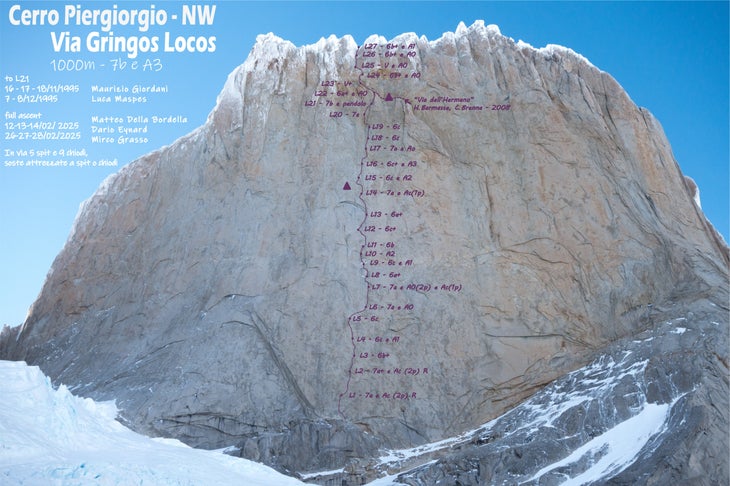

With mandatory, sky-hook protected free climbing up to 5.12, ‘Gringos Locos’ is an apt route name.

The post Inside a Bold, El Cap-Sized First Ascent in Remote Patagonia appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Cerro Piergiorgio is just down valley of Cerro Torre and Chaltén (Fitz Roy), but, in terms of climber traffic, it might as well be on the moon. Chaltén sometimes receives dozens of ascents a season. Piergiorgio might see one. And Piergiorgio’s giant west face, standing sentinel over the vast Southern Patagonian Ice Field, hardly ever gets climbed.

The reasons for Piergiorgio’s unpopularity are plenty: its west face requires a full extra day of hiking to reach; due to its remoteness, volunteer-based rescue is next to impossible; and its cracks—unlike the clean splitters of the Franco-Argentina—are woefully discontinuous. The west face demands serious commitment and physical prowess to top out. Falling is frequently not a viable option.

The Italians Maurizio Giordani and Luca Maspes conceived of this beautiful line in 1995, a direttissima smack in the middle of the west face, 1,000 meters from glacier to summit. The pair encountered sheer slabs and few continuous cracks, and after climbing roughly three quarters of the wall they retreated due to Patagonia’s famously persistent high winds and destructive storms.

Only two other expeditions have tried to complete the line since: Maspes with Kurt Astner, Hervè Barmasse, and Yuri Parimbelli (the team bailed after Maspes was hit by a landslide but miraculously survived); and a second attempt by Giordani, in 2018, with Barmasse, Francesco Favilli, and Mirco Grasso, who were again plagued by storms.

Now, 30 years after the first attempt, Matteo Della Bordella, Dario Eynard, and Mirco Grasso have completed a brilliant new line: Gringos Locos (7b/5.12b A3; 1,000m).

The trio based themselves in the small town of El Chaltén and began working their line in mid February. Climbing the pitches first established in 1995 were an alarming brush with the past: protection was difficult to place, scarcely reliable, and mainly psychological.

The team climbed and fixed rope on the first half of the route over three days, then a storm blew in and they bailed back to town. High winds shook the mountains for most of February, preventing them from returning to Piergiorgio, but when a small weather window appeared just before they were scheduled to fly home, they raced back into the mountains.

Watch a video of the team piecing together their ascent below:

Compared to other walls in Patagonia, Della Bordella says that the west face of Piergiorgio is much less featured—“more of a vertical slab with crimps” than the classic hand and fist cracks. After 14 trips to the area he calls the west face “radically different” from anything else he’s climbed, especially since he strived to maintain Maspes and Giordani’s ethic of extremely minimal bolting. The Gringos Locos team often would switch from sky hooking to free climbing—and back to hooking—in order to piece together this improbable line. It was a logical continuation to the style used by the 1995 attempt: Maspes told Climbing that, back then, without micro cams, he graded one pitch A4 due to “seven consecutive moves on hooks with the risk of a 30-meter fall. It was the most beautiful failure of my climbing career.”

Perhaps the most interesting element of this ascent is not the climbing itself but the team who made it happen. Della Bordella and Eynard in particular are not longtime climbing partners. They haven’t even been friends for all that long. Their partnership is the culmination of a two-year course sponsored by the Italian Alpine Club, which pairs veterans like Della Bordella with young, psyched alpinists to develop their skills. Eynard, born in 2000, was a member of the resultant “Eagle Team” and eagerly pitched himself to join the Piergorgio project. “It was a big gamble,” Della Bordella says, “[but Eynard] turned out to be a great partner. [His] was the spirit I had in mind for the Eagle team.” Two other members of the Eagle team were supposed to join on Piergiorgio, but when both became injured Della Bordella called up his friend Mirco Grasso, who was also in El Chaltén, and invited him instead.

“In the end, we really took advantage of every little moment of good weather,” Della Bordella says. “[After ascending our fixed lines,] we spent a night on the wall, in the wind, in a portaledge, and we reached the top at 3 in the morning. … A huge satisfaction!”

The post Inside a Bold, El Cap-Sized First Ascent in Remote Patagonia appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Each January we post a farewell tribute to those members of our community lost in the year just past. Some of the people you may have heard of, some not. All are part of our community.

The post A Climber We Lost: Sergey Nilov appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

You can read the full tribute to Climbers We Lost in 2024 here.

Sergey Nilov, 47, August 18

Sergey Nilov, one of the world’s most accomplished high-altitude climbers and a two-time Piolet d’Or recipient, died on August 18, 2024, at age 47, in an avalanche on Gasherbrum IV (7,925m) in Pakistan. He was attempting to recover the body of his longtime climbing partner and dear friend Dmitry Golovchenko, who had perished on the same mountain exactly one year prior.

Nilov discovered mountaineering in an unexpected encounter while on a canoe trip in the early 2000s, where he met some climbers and was immediately fascinated by the steep walls and snow capped peaks around. This chance meeting led him to join Moscow’s CSKA Demchenko climbing club, where he met Golovchenko in 2002. Their first climb together in the Caucasus mountains near Elbrus marked the beginning of one of alpinism’s most formidable partnerships.

Outside of climbing, since neither he nor Golovchenko were sponsored professional climbers, Nilov worked as a rope access technician and tree maintenance specialist. He leaves behind his wife Anastasia and their five children, who now face the profound loss of their father and husband.

The partnership between Nilov and Golovchenko, spanning over two decades, produced some of alpinism’s most remarkable achievements. Their ascents included the first ascent of Think Twice (ED 5.10 A2 M6) on Pakistan’s Muztagh Tower in 2012, earning them their first Piolet d’Or. They won a second Piolet d’Or in 2016 for Moveable Feast (ED2 M7 WI5 A3) on India’s Thalay Sagar. Perhaps their most notable achievement was the 2019 epic on Jannu’s East Face, where they spent 18 days on the mountain in a display of extraordinary endurance and determination.

Their partnership was marked by an intuitive understanding that transcended words. As Golovchenko once noted, “Sergey Nilov, in what he does, is the best in the world… he gives you a sense of security.” Their roles were clearly defined: even if they were both very skilled climbers, Golovchenko handled all logistics and planning, while Nilov took the lead on technical climbing.

Their final chapter began on August 31, 2023, when Golovchenko fell to his death when their unanchored tent, at 7,680 meters, slipped off their narrow bivy ledge. Nilov, who witnessed the tragedy, managed to rappel down and locate his friend’s body and lay him to rest in a crevasse.

Almost a year later, Golovchenko’s family launched an appeal to form a team of climbers to recover the body from the mountain. Sergey initially refused to join the team, honoring a promise he and Golovchenko had made to take care of the other’s family if they died in the mountains. Dmitry had a wife and three daughters, Sergey his wife Anastasia and five sons.

But, finally, Sergey thought that without his help, the team would not be able to locate Golovchenko’s resting place, which after a year was probably covered in snow and ice. So he joined the team that reached the Gasherbrum basecamp in July 2024. Conditions on the mountain were far from favorable: stormy weather and the news from another climbing team that the icefall had shifted and was more dangerous than ever. Even so, when stable weather arrived, the team started to climb.

While navigating the treacherous icefall, a serac collapsed and an avalanche struck Nilov and two teammates. His companions survived with injuries, but Nilov disappeared into the icy debris. A rescue was launched, but Nilov’s body rests in the icefall, not far from his brother of rope, and life, Dmitry.

Nilov embodied the purest values of alpinism: humility despite extraordinary achievement, unwavering loyalty to his climbing partners, and an uncompromising commitment to alpine-style ascents. His loss, coming so soon after Golovchenko’s, leaves an irreplaceable void in both the climbing community and the lives of those who loved him. As fate would have it, these two inseparable partners now rest eternally side by side in the Karakoram mountains they so deeply cherished.

To write that Sergey died doing what he loved would sound hypocritical to my ears; the relationship I had with him and Dmitry, two extraordinary mountaineers and good people, had become friendship, and my thoughts are for their families, for Anastasia, Sergey’s widow, for Sasha, Dmitry’s widow, both extraordinary and strong women and for their eight sons and daughters who lost their husbands, their fathers, too soon.

The sense of Greek tragedy resonates in my thoughts, and the enthusiasm with which I followed their unique, extraordinary climbs becomes a bitter thought of irreparable loss.

You can read the full tribute to Climbers We Lost in 2024 here.

The post A Climber We Lost: Sergey Nilov appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

To keep things sporting, the team kayaked 280 miles, fended off polar bears, dangerously large waves, and their own inexperience in such lightweight boats.

The post “Psychological” New 5.12 on Remote Greenland Big Wall appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

The elite Italian alpinist Matteo Della Bordella is no stranger to remote and committing expeditions, but this summer he took his new-routing to a new level. Alongside Symon Welfringer, Silvan Schüpbach, and Alex Gammeter, Della Bordella made the first ascent of a 1,200-meter big wall in a rarely visited corner of Greenland’s east coast. To keep things sporting, the team kayaked all of their equipment a total of 280 miles (450 km), fending off polar bears (seriously), dangerously large waves, and their own inexperience in such lightweight boats.

Their 45-day expedition can be summed up simply, with the first ascent of the north face of Drøneren (a “psychological” 5.12b; 1,200m), but I knew there was much more to their story. After all, posts from Della Bordella hinted at vicious Arctic storms, sections of impassable pack-ice, and, yes, that curious polar bear. I also knew that a 5.12 bigger than El Cap in the middle of nowhere would be far from a clip-up, demanding serious run outs and a lot of willpower.

So I reached out to Della Bordella when he returned to the small fishing village of Tasiilaq, Greenland, where he was taking some deserved rest before a flight back to Italy. He was exhausted, but happy to talk more about this awe-inspiring expedition.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

The Interview

Climbing: Where did you get the idea for this expedition? And what preparation did you do as a team—did you all have kayaking experience?

Della Bordella: The idea for this expedition comes from a long way back. Several years ago I identified this area of walls through satellite images, then I discovered that the American Mike Libecki had already been (still the only climber I know of) so after various searches I identified the north face of Drøneren as a possible objective, 1,200 meters tall and never climbed by anyone. It was attempted only by Libecki in 2017.

I immediately proposed the project to Silvan and then to Symon. We wanted to go there in 2021, but due to Covid we changed plans and headed to the Mythics Cirque further north. So, after several postponements, in 2024 the right time had come. Alex Gammeter joined the team, and though Symon and I didn’t know him, we immediately got along very well.

Climbing: You had to wait a lot through bad weather, both at the start of the expedition and once you arrived beneath the wall. Tell me about that.

Della Bordella: This was my fourth climbing expedition with a kayak approach and I have accumulated some experience. However, this was definitely a new level for the distance and for the fact that nearly all our travel was directly exposed to the ocean and not in a fjord (a huge difference in weather and wave size).

We trained individually and then as a team on three-meter waves for a few days in Lerici, Italy, under the guidance of the Italian master of sea kayaking, Guido Grugnola.

This year the amount of pack ice present on the sea was enormously higher than average. Everyone told us that we had chosen the wrong year for this project, that there was too much ice and we would not make it to the wall. We postponed the expedition by a week, then by another four days…then we tried despite the thousands of doubts. We are stubborn!

On the third day of kayaking, it took us six hours to travel just 9 kilometers (5.5 miles), zig-zagging between big ice blocks in constant motion.

Of my four expeditions to Greenland this one had without a doubt the worst weather. On the journey to the wall, a 60-hour storm kept us locked in the tent. That wasn’t such a big problem, but the three-meter-tall waves in its aftermath were.

Once we finally made it to the wall we made four attempts that all ended due to the weather: two due to rain, one due to snow, and another due to the Piteraq wind, with gusts of over 100 km/h that caused spontaneous rockfall including a scary one that cut the rope Symon was actively hanging from. After that episode I said to myself, “Damn, this wall just doesn’t want to let us pass.”

Climbing: What was your strategy on the wall? Tell me about the route itself, and the descent.

Della Bordella: On the wall, all four of us took turns leading. Sometimes we all free climbed, other times only the leader did to be faster. The crux pitch was notably harder than the rest: a 5.12b (7b) slab protected by really precarious Pecker pitons. Silvan opened it, I followed it, and then Symon led it again, flashing it. The rest of the route has many pitches up to 5.11d/12a of beautiful cracks opened onsight. Nothing was left on the wall except the belays made with pitons and nuts.

Climbing: Your return trip sounded problematic, running out of food and having to fish with your ice axes. How did that turn out?

Della Bordella: The return to Tasiilaq was a race against time and against the food supplies that were running out. The expedition was completely autonomous and as a result we only had food for 32 days. On the way there, we kayaked 300 kilometers, but on the way back we made it only 150 until our food fully ran out (and another Arctic storm came in). Thankfully a passing boat of hunters came to pick us up. Surely with less bad weather we could have returned without problems, but the unexpected is part of the adventure. We also met four polar bears, one of which at a very, very close distance! Despite attempts to deter him he kept trying to get close to us. So we started keeping a look-out each night, which was stressful.

The post “Psychological” New 5.12 on Remote Greenland Big Wall appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Sergey Nilov and Dmitry Golovchenko climbed some of the world’s hardest alpine walls. But in a heart-breaking twelve months, they were both killed on Gasherbrum IV.

The post Tragedy Marks the End of an Elite Climbing Partnership appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

One year ago, on August 31, Sergey Nilov and Dmitry Golovchenko were exhausted but satisfied as they melted snow outside of their small two-person tent. The Russians were preparing a hot drink before catching some rest on a precarious ledge at 7,684 meters, high up on Gasherbrum IV’s (7,925m) gigantic Southeast Ridge. They were nearly at the end of the technical difficulties, just one steep headwall separated them from the summit ridge.

The frequent climbing partners and best friends clambered inside, but immediately felt the tent slipping off its snowy platform. Nilov rushed outside to secure it to their anchor, while Golovchenko, still inside, tried to collect their gear. Golovchenko screamed: “Sergya, I’m falling!” and Nilov watched with horror as the tent and his dear friend fell off the ledge and into the airy black void.

Nilov barely survived the descent himself—a nightmare of both technical alpine terrain and overwhelming grief—but he made it down to the glacier where he found Golovchenko, wrapped him in their tent, and moved his body near a crevasse at 6,950 meters. Then he stumbled back to base camp.

***

Ten months later, an announcement on the Russian climbing website Mountain.ru called for climbers to join a team—organized by the Russian Federation of Alpinism, and led by Sergey Nilov—to recover the body of Dmitry Golovchenko and return him to his family. Nilov and Golovchenko had been friends for over 20 years, spending long stretches of time both in the mountains together, on cutting-edge expeditions, but also back home in Russia, and on family holidays. Nilov needed to recover his friend’s body.

In the early days of August, Nilov, Alexey Bautin, Mikhail and Sergey Mironov (no relation), and Evgeny Yablokov set off for Gasherbrum IV with this sole goal. They arrived at the base of the mountain on August 11, beneath a hazardous icefall between Gasherbrums III and IV. A separate team had previously inspected the area and told them they had seen the icefall where Golovchenko lay, noting that it had become much more broken and complex since August 2023. “[The icefall] does not look safe,” they advised. “The upper front of the glacier has collapsed. The body wrapped in a tent is nowhere to be seen.” But part of the icefall had been navigated safely, by Aleš Česen and Tom Livingstone, who had just completed the first ascent of the West Ridge of Gasherbrum III, and they left a tent at 6,000 meters with gas canisters for the Russians to use during their recovery mission.

But on August 17, while moving through the icefall, a serac broke loose and hit Nilov, Mikhail, and Sergey Mironov. Nilov disappeared into the icy wreckage, while the other two climbers were badly injured and initially unable to move. In the meantime, Alexey Bautin and Evgeny Yablokov had fallen ill at base camp, and after the accident were unable to assist their comrades on the mountain.

The Russian Federation and Pakistani military deemed the icefall too dangerous to perform a helicopter rescue, so they deposited a rescue party of Pakistani climbers at base camp. The pilots scanned the icefall from above, spotting the moving but injured Mihail and Sergey Mironov, as well as the prone figure of Nilov.

The following day, Mikhail and Sergey Mironov managed to descend a small section of the icefall and miraculously found Nilov’s bag with painkillers, food, and gas, which enabled them to survive another night. The rescuers finally reached the duo on the 20th and helped them descend to advanced base camp at 6,100 meters. Helicopters are currently waiting on clearer weather to take them to a hospital in Skardu.

On a final flight the pilots noted that Nilov’s body was no longer visible in the active icefall. They have suspended their search for the time being, citing little chance of his survival.

***

There is a sense of a Greek tragedy with this news, a twist of fate which led to the bitter end of one of alpinism’s great pairings—on a beautiful, magnetic mountain like Gasherbrum IV. My only thoughts now are for the five children of Sergei and his wife Anastasia, who will have to bear the loss of their father and husband—as happened tragically to Sasha, Dmitry’s widow, and their two daughters twelve months ago.

I will never forget these two brave, committed comrades, who enlightened our community with their incredible ascents—including, but not limited to, No Fear (VII 5.10d A3; 1,120m) on Pakistan’s Nameless Tower (6,251m); Think Twice (ED 5.10 A2 M6; 3,400m) on Pakistan’s Muztagh Tower (7,276m); Ninth Wave (ED 5.11 WI5 M6 A2; 1,885m) on Sedoy Strazh’s (5,841m) East Buttress in China; and Moveable Feast (ED2 M7 WI 5 A3; 1,400m) on Thalay Sagar (6,904m), India—but who also never let their elite status change the fabric of themselves, humble workers and humans with little sponsorship support.

This tragic story reminds us of the brutal reality of the mountains, which remains impassive of the small destinies of human lives.

The post Tragedy Marks the End of an Elite Climbing Partnership appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Each January we post a farewell tribute to those members of our community lost in the year just past. Some of the people you may have heard of, some not. All are part of our community and contributed to climbing.

The post A Climber We Lost: Dmitry Golovchenko appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

You can read the full tribute to Climbers We Lost in 2023 here.

Dmitry Golovchenko, 40, August 31

In 2001 a young Dmitry Golovchenko joined the famed Demchenko Alpine Club, a group which initially served as a military school in the 1970s. The Club was founded by Alexander Demchenko, a man known for his severity during training, and one who went to great lengths to educate his students on the philosophy of fast and courageous alpinism; quite the opposite of the traditional Russian style of mountain assault, with large, cumbersome expeditions and extensive use of fixed ropes and camps.

By the time Dmitry entered the Club’s ranks it had become an important resource for young Russian alpinists; it was there that he met Sergey Nilov and they became fast friends during their first expedition, in 2002, to the Caucasus mountains. Over the next decade Dmitry and Sergey scrabbled together funds amidst their busy lives to go on sporadic expeditions, slowly acquiring the skills to climb quickly and boldly in the Greater Ranges.

Dmitry’s climbing ability was highly regarded within the Russian mountaineering community in the late aughts, and by 2011 his name reached the international stage with a first ascent on Nameless Tower’s (6,251m) Northwest Wall, in the Karakorum, with Sergey, Victor Volodin, and Alexander Yurkin. They named their route No Fear (VII 5.10d A3; 1,120m)—the Demchenko Alpine Club’s motto. Dmitry returned to the Karakorum, in 2012, where he made the first ascent of the Northeast Spur of Muztagh Tower (7,276m) via Think Twice (ED 5.10 A2 M6; 3,400m) alongside Sergey and Alexander Lange. Think Twice earned Dmitry his first Piolet d’Or (2013). And in the Chinese Tien Shan, in 2015, Dmitry teamed up with Sergey and Dmitry Grigoriev to establish Ninth Wave (ED 5.11 WI5 M6 A2; 1,885m) on Sedoy Strazh’s (5,841m) East Buttress. But the climb that established Dmitry as one of the strongest mountaineers in the world was surely his direttissima up the North Face of Thalay Sagar (6,904m) in the Indian Himalaya: Moveable Feast ED2 M7 WI 5 A3; 1,400m) with Sergey and Dmitry Grigoriev. With this masterpiece Dmitry gained his second Piolet d’Or, in 2017. It’s worth mentioning that Dmitry was a four-time winner of the Russian “Golden Axe” award (2012, 2015, 2016, 2017).

My personal friendship with this extraordinary person happened after another unbelievable climb with Sergey; in 2019, when they made the first ascent of Jannu’s (7,710m) East Wall to the summit ridge. The duo crossed the summital ridge at 7,412 meters and descended the opposite side, down the French line, an aspect unknown to them and after having been climbing for 12 days. They completed the traverse of the mountain and met Eliza Kubarska’s filming team on the opposite side, who welcomed them into their camp and fed them, before they made the long trek back around the mountain to the Russians’ camp. Dmitry and Sergey’s 17-day odyssey was followed live on socials, where I was in daily contact with Anna Piunova (editor in chief of Mountain.ru ), Manu Rivaud (Montagnes Magazine), Victor Gorlov (a friend and former climbing partner of Dmitry, who introduced me to him after this expedition), and others who gave beta to the climbers for their uncertain route of descent.

I exchanged many emails and texts with Dmitry, initially for a long feature I wrote about him for Rock and Ice Magazine. After, I followed Dmitry’s updates during all his expeditions, especially his August 2019 ascent of the massive Southwest Wall of Military Topographers Peak (6,873m) in the Tien Shan, Impromptu (TD 5.10b; 3,000m), with his “brother” Sergey and Dmitry Gregoriev. What made this climb even more difficult and impressive, to me, was the long and tedious approach the trio took, carrying all their equipment themselves.

Dmitry’s climbing goals, at this point, his last years, were extremely difficult and dangerous. He wrote to me about the intention of an attempt of Annapurna III’s Southeast Ridge, but a trio of Ukrainians alpinists beat him to the punch. So, in June of this year, Dmitry confided with me about his goal of a new route on the Gasherbrum IV (7,925m) with Sergey. We were in daily contact when he reached the Gasherbrum basecamp and after a reconnaissance of the peak’s conditions, they opted to attempt the completely unknown Southeast Ridge to the summit and then descend the West Ridge (Bonatti-Mauri, 1958). Dmitry put me in touch with his wife and asked that I relay weather forecasts through an expert friend of mine.

Gasherbrum IV represented a new difficulty for Dmitry and Sergey; they had never climbed so high before, and even the approach through a horribly crevassed glacier was extremely challenging. They began the climb on August 21. Forecasts seemed neither terribly bad nor good, but in reality the mountain had thick fog, strong winds, and bitter cold. Nevertheless, for the next 10 days, they made steady progress in spite of the adverse conditions. They spent more than a week above 7,000 meters and their final communication through sat phone was on August 29, at about 7,600 meters, on the final pitches of the Southeast Ridge before the junction with summital South Ridge. We didn’t hear from them for several days, and when Sergey finally returned to basecamp, with severe frostbite and in a state of shock, he had horrible news: Dmitry was gone.

During their last tent bivouac, at 7,684 meters, the duo noticed that the tent was unstable on its platform and slowly slipping over a steep drop. Sergey went out to try to secure it more solidly, and with infinite horror he heard Dmitry, still in the tent gathering some equipment, exclaim: “Sergey, I’m falling!” In an instant, the tent with Dmitry inside disappeared into the void, falling all the way down to the glacier below, where Sergey, after a terrible, solitary descent in extreme conditions, recomposed the body of his brotherly friend, wrapping him in the tent and dragging him into a crevasse where he will rest forever. Dmitry is survived by his wife Sasha and two daughters.

Dmitry Golovchenko was an extraordinary person. The climbing community has become accustomed to the idea that each project he announced to the world would be extraordinary. Each peak, each successive achievement of his team, is rather a small story in a big life. A story that serves as inspiration and shows that the possibilities of anyone, even the simplest person, are limitless. And although he stood on various podiums more than once, holding cult awards in his hands, he remained a simple, lively, ordinary guy. Yes, he is not the hero that organizations and media put on pedestals. Not the one who has stars on his chest. He was truly living in the moment here and now, and he was a precious friend for many people.

You can read the full tribute to Climbers We Lost in 2023 here.

The post A Climber We Lost: Dmitry Golovchenko appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Salvaterra climbed around the world with true dedication—especially in Patagonia. Guidebook author Rolando Garibotti called Salvaterra “The most devoted and committed lover Cerro Torre has ever had.”

The post A Climber We Lost: Ermanno Salvaterra appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

You can read the full tribute to Climbers We Lost in 2023 here.

Ermanno Salvaterra, the famed “Man of Cerro Torre,” died in a fall on August 18 while guiding the Hartman-Krauss (IV+/5.5; 600m) on Campanile Alto, in the Dolomites.

Salvaterra had climbed the classic route dozens of times before, and was placing a cam when his handhold ripped from the wall. He fell 20 meters, passed the belay, and struck his head against the wall. His climbing partner, a client, rappelled down to reach him but could do nothing except comfort Salvaterra during his final moments. He was 68 years old.

Salvaterra, born in Pinzolo, Italy, was raised by parents who managed an alpine hut in the rugged Brenta Dolomites, the perfect playground for a wide-eyed boy. Salvaterra developed a passion for mountain sports at a young age and became a Skiing Master Instructor at 20 years old, then an Alpine Guide four years later. He established significant modern climbing routes in his home range, including Via Delle Aspiranti Guide (6a+/5.10; 300m) and Elefante Viola (5.10; 300m) on Pilastro Bruno, Super Maria (5.10; 750m) on Crozzon di Brenta, Cheyenne (5.11-; 350m) and Duomo dei Falchetti (5.10+; 300m) on the Campanile Basso, and the classic Via della Soddisfazione (5.10a; 380m) on Cima d’Ambiéz.

Salvaterra first heard about Patagonia’s stunning spires while in conversation with the legendary Renato Casarotto, who had established Cerro Chaltén’s (Fitz Roy) Goretta Pillar in 1979.

Salvaterra’s first expedition to Cerro Torre was in 1982. The 27-year-old was most comfortable on the Dolomites’ limestone walls, but he’d climbed enough icy granitic faces in the Alps to feel prepared. Salvaterra teamed up with Elio Orlandi, their first of many trips together, and laid the foundation of a longstanding and successful partnership. The duo wasted no time on warm-up climbs and took aim at Cesare Maestri’s Compressor Route, ultimately bailing from midway up the mountain.

Salvaterra returned to Cerro Torre in October 1983, accompanied by Maurizio Giarolli. He understood how uncommon it was to visit the mountain during such a snowy time of year, but he had no choice: In Italy, he worked the summer seasons in the climbing huts, then the winters as a ski instructor. His only chance to climb in Patagonia was during the autumn break!

His second Patagonia trip was a glorious success. First, the Ermanno-Maurizio duo climbed Cerro Torre’s Compressor Route, taking the Jim Bridwell variation on the final sections. Then, joined by Elio Orlandi in November, they climbed the famous Supercanaleta (5.9 WI4; 1,500m) on Cerro Chaltén. They tagged Aguja Guillaumet and Aguja Poincenot before heading back to Italy.

Two years later, July 1985, Salvaterra teamed up with Paolo Caruso, Maurizio Giarolli, and Andrea Sarchi to make the first (austral) winter ascent of Cerro Torre, summiting on July 7 after a week of battle against extreme colds, winds, verglass, and freezing bivouacs on the wall.

Salvaterra’s seemingly infinite love for Cerro Torre propelled him toward five new routes on the mountain. First came Infinito Sud (6b/5.10d A4 70˚; 1,200m) in 1995 with Roberto Manni and Piergiorgio Vidi. Then, in 1999, with Mauro Mabboni, he climbed a variant of the Compressor Route. In 2004, with Alessandro Beltrami and Giacomo Rossetti, he opened Quinque Anni ad Paradisum (6c/5.11b A4 90˚; 900m) on the East Face. In 2005, with Rolando Garibotti and Alessandro Beltrami, he climbed the North Face by opening the now-famous El Arca del los Vientos (6b+/5.11a C1 60˚; 550m), the same face that Cesare Maestri had purported to climb (despite many naysayers) in 1959. Salvaterra had long believed Maestri’s claim, but after climbing the feature and seeing no trace of his ascent, Salvaterra eventually lost faith in his hero.

Salvaterra will be forever celebrated in Patagonia-climbing history, not just for his successful ascents, but for his visionary attempts, seeing lines and opportunity where few others did.

Also a prolific filmmaker, photographer, and writer, Salvaterra was described by his friends as an always-smiling elf, always active and restless, with a shy demeanor that faded to brilliance and enthusiasm as he got to know you. He and his wife, Lella, had no children but deeply valued their presence while guiding hikes and climbs, or ski instructing.

Allow me to leave you with a quote from Salvaterra, which, I think, captures his infatuation with Cerro Torre:

“When I talk about Cerro Torre and her sisters, my narrative is similar to that of a woman. If you like a girl and you think she’s the most beautiful girl in the world, the more you look at her, the more you like her. Then you don’t feel any need to court others.”

Salvaterra and Cerro Torre made great impressions on one another. And we are all richer for it.

You can read the full tribute to Climbers We Lost in 2023 here.

The post A Climber We Lost: Ermanno Salvaterra appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

'Qué mirás' follows a logical line of weakness—splitter cracks, friction dihedrals, and several punchy roofs—up the center of the East Face for 14 long pitches.

The post Matteo Della Bordella on His Aguja Mermoz FA and Finding New Challenges in Patagonia appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

On January 10, Sean Villanueva O’Driscoll, Matteo Della Bordella, and Leo Gheza opened a stunning new route on the East Face of Aguja Mermoz, in Patagonia. They named their 1,600-foot 5.12b ¿Qué mirás, bobo? (What are you looking at, idiot?), a reference to soccer player Lionel Messi’s quip during a World Cup interview in December 2022.

Qué mirás follows a logical line of weakness—splitter cracks, friction dihedrals, and several punchy roofs—up the center of the East Face for 14 long pitches. Impressively, they free climbed the entire route onsight, and left not a single nut, piton, or sling behind.

But the team’s ascent nearly ended before it truly began: at dawn, while Gheza led the first wandering pitch, his ropes dislodged a series of blocks that tumbled down to the belay. “[It was] not the best start, but at least no one got hurt,” Della Bordella told Climbing. One of their lead lines was cut but the trio decided they had a workable amount to continue. They reached the summit late that evening, around 9:30 p.m., and watched as the sun set behind Cerro Torre. They chose to bivy there under clear skies and descended Pilar Rojo the following morning.

Qué mirás, it seems, was just the beginning of another successful Patagonian season for Della Bordella who a few days later repeated the Care Bear Traverse (5.11; 6,400ft), a link up of Aguja Guillaumet, Aguja Mermoz, and Cerro Chaltén (Fitz Roy) via its North Pillar with Gheza. Then, in the most recent weather window, he teamed up with Kico Cerdá for Rayo de Luz (5.11d; 1,300ft) on the West Face of Guillaumet, nearly nabbing an all-free ascent amid the icy conditions. He told Climbing: “It turned out to be a perfect line of cracks, vertical and sustained, a real pearl for lovers of the genre.”

Last year, Della Bordella’s season ended in tragedy after a remarkable first ascent on Cerro Torre’s east and north faces. Alongside Davide Bacci and Matteo De Zaiacomo, he had established a new route up the formidable aspect before linking up with Corrado “Korra” Pesce and Tomás Aguiló, who’d also climbed a new route on the east face. They climbed as a party of five to the summit but Pesce and Aguiló immediately began to descend, hoping to capitalize on the inbound night’s cooler temperatures. Early the next morning the pair was hit by rock and ice fall, forcing a gravely injured Aguiló to descend alone while Pesce, mortally injured, remained on the wall. After descending a separate line, Della Bordella was horrified to learn of the accident. He immediately returned to the East Face in an attempt to rescue Aguiló and Pesce, climbing 1,000 feet of runout terrain before finding Aguiló. Because of inclement weather, however, Pesce could not be reached.

- Read: Remembering Korra Pesce

The death and rescue on Cerro Torre shook Della Bordella deeply, and this year in Patagonia he wanted to try something new: new styles, new partnership. Gheza had reached out to him in September 2022, asking to climb together in El Chaltén. “I already had climbed with him in the past and the feeling was great, so he seemed [like] the right partner for [other] great Patagonian adventures,” he said.

Their main goal was the full Fitz Traverse (5.11d C1; 11,800ft), a climbing objective that Della Bordella said is a significant departure from his typical big-wall endeavors. “It’s a climbing style that, for me, is very different from the usual. [On traverses] you don’t have extreme difficulties, but you have to climb quickly and efficiently and adapt to different [routes]. For me, a new challenge.”

Though Della Bordella and Gheza did not achieve their main objective, Della Bordella later wrote that he’s enjoying the new terrain.

Federico Bernardi runs the Italian climbing-news website montagnamagica.com.

Also read:

- The Redwood Coast: Home to Secret Limestone and 5.14+ Trad

- How Ukrainian Climbers Traded Mountains For War

- New Sends We Cared About: A WI 6+ Free Solo FA (and more)

The post Matteo Della Bordella on His Aguja Mermoz FA and Finding New Challenges in Patagonia appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

The 30-year-old from France set a blistering record on Broad Peak. Then he took it too far.

The post Benjamin Védrines on Himalayan Speed Records, Para-alpinism, and Passing Out on K2 appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Benjamin Védrines, of Monnetier, France, is relatively new to the 8,000-meter climbing scene, but has an impressive résumé spanning all mountain genres: hard mixed, committing ski descents, protracted trail runs, and exploratory paragliding. Védrines stumbled onto many peoples’ radar last October when he opened the North Face of Chamlang (7,319 meters) with Charles Dubouloz: the sustained In the Shadow of Lies (ED WI 5+ M5+ 90°; 1,600m).

This summer, Védrines returned to the Himalaya with the goal of climbing Broad Peak (8,051 meters) as his first 8000er. He’d been cardio focussed all spring, including a 28-hour ski traverse of the Écrins massif with some 32,000 feet of ascent, and arrived at Broad Peak’s base camp feeling fit and eager to climb quickly at altitude.

Védrines warmed up on the West Ridge (the peak’s “normal route,” replete with Sherpa-installed fixed lines and boot packs) and climbed to the summit in a day on July 9. He returned to camp feeling surprisingly strong, despite climbing without supplementary oxygen, and ten days later he returned to the West Ridge for a speed attempt. Védrines climbed from the 4,900-meter camp to the summit in a blistering seven hours and 28 minutes. He launched his paraglider from the top in “perfect” conditions, landing back at base camp after one hour of flight—just in time for breakfast.

Védrines was certainly pleased with his performance on Broad Peak but he was far from satisfied. As he told me in the interview below, which has been edited for clarity and length, this drive for greater performance nearly led to his death on K2—a far higher and more technically challenging objective.

The Interview

Climbing: Broad Peak was your first 8000er. Then you went to K2. How did you prepare for this expedition, and did you originally plan to climb two 8000ers and descend via paraglider?

Védrines: I prepared for the K2 expedition mainly during the spring, focusing my training time on endurance. During the winter I climbed 8a [5.13b] and did a very nice trilogy of three major north faces in the Alps with Léo Billon and Seb Ratel. After that, I stopped climbing and devoted myself to skiing, cycling, walking, and flying. I did two great ski-mountaineering crossings: the Écrins massif, in 28 hours with 10,000 meters of ascent, and the Mont Blanc massif in 20 hours with 7,500 meters of ascent. These two experiences allowed me to gain a lot of confidence before the expedition.

Broad Peak was the main goal for this expedition, but I had not planned to descend it by paragliding. Once I was there I realized that it was possible to take off from the summit. Thanks to Nicolas Jean, who went up there before me, and who was able to describe the profile of the summit slope. It was only with his help that mixing the two challenges was then imaginable!

Climbing: Did you encounter any difficult moments on the climb, particularly on the tricky, technical summit ridge? And how was your descent with the paraglider?

Védrines: I never felt too much difficulty during the climb. I think I was very well prepared. However, by forcing myself to move so quickly, I had to remain concentrated in my physical effort and to maintain the pace. At around 7,600 meters my heart was beating very hard and I was afraid of forcing too much and of having problems related to the altitude. This is mainly what I remember: this anxiety linked to the altitude.

The summit ridge was not very difficult for me, especially since the track was very good that day. It was much tougher nine days earlier when I first summited. For the paragliding flight, the takeoff was very pleasant and there was the perfect wind to take off serenely. Then I was able to fly over the North Ridge, above the climbers, passing a little on the Chinese side. Then I was able to enjoy 25 minutes of flight, admiring the surrounding peaks, and finally land near the base camp, on ice.

Climbing: What gear did you carry with you during the climb?

Védrines: I had two different bags: a 22-liter bag in a very light fabric (about 80 grams) and a 120-gram trail-running vest. At the start [4,890 meters to 7,600 meters] I had a first-aid kit of about 80-100 grams, 1.5 liters of water, and about 200 grams of food in my vest. From 7,600 to the summit, I added in the small bag carrying a paraglider (1,410 grams). For the fixed ropes, my goal was not to climb without them. In this environment [on the West Ridge], climbing right next to a fixed rope is not considered alpine style, so I used them from time to time, about 5% of the route, with my hands. I didn’t have a jumar.

Climbing: On your next objective, a fast ascent of K2, you fell ill after reaching 8,000 meters. I read that you lost consciousness and you were given supplemental oxygen by passing climbers. Can you tell me how you felt in the moments before you lost consciousness?

Védrines: To be completely honest, I didn’t feel anything tangible that could have led me to understand that I was going to be in a very dangerous situation. The first moments above 8,000 meters went well. I felt tired, but that was normal at my pace and at that altitude. At 8,300 meters my condition suddenly deteriorated. Instantly, I no longer had the same energy, nor the same state of consciousness. It’s from there that I don’t remember everything.

Climbing: Now that you’re safely back home, how do you feel about your decision making on K2? It is possible that you forced yourself too much?

Védrines: It’s true that it was a big risk to try K2 after having climbed Broad Peak twice without oxygen, once at a very fast pace. When I decided to go to K2, I didn’t want to set an ascent record. I didn’t want to climb at the same speed as on Broad Peak. I was mature enough to know it was too risky. My goal was to climb K2 in a day at an appropriate pace.

But, on the day of the ascent, the weather conditions as well as the snow conditions were not good. It really slowed me down and tired me. This accumulation of fatigue weighed on me at Camp 3 and I had to ask myself if I should continue or not. It was at this point that I made a mistake. I decided to continue despite the fatigue, too attracted by this summit. I really thought that if I took it easy I could do it. But you have to understand that the effects of altitude are unpredictable without oxygen.

Looking back, I realize I did not commit to K2 in the best conditions. Those 600 meters more than Broad Peak make a difference. And climbing an 8000er in a day without oxygen is very demanding on the body. Mine did not resist hypoxia. If I had to go back, I would devote all my time to this climb, I would not do demanding climbs before.

Climbing: How do you feel following this expedition, after such a successful double-ascent of Broad Peak to a low point on K2?

Védrines: It was a very interesting and varied expedition. The first Broad Peak climb gave me confidence, it was my first 8000er. The second Broad Peak climb was one of my best moments as a sportsman: an accomplishment that is rare in the life of a mountaineer. It made me want to go even harder, even higher. And K2 was right there. I went. I could have died up there. I lived the dream on Broad Peak and the nightmare on K2. It allowed me to see my limits. But also the limits of high altitude without oxygen. It’s a very dangerous place, especially for people like me who want to go fast.

After Védrines’ ascent of Broad Peak, some doubted the record-breaking time he claimed. Climbing reviewed Védrines’ GPS-track data and can confirm his 7:28 time—Ed.

Also read:

- Bad Style On El Cap Is The Norm. It’s Time To Change That.

- Jacopo Larcher and Babsi Zangerl on Keeping the “Eternal Flame” Burning

- Remembering Rock Guide and Educator Cody Bradford

The post Benjamin Védrines on Himalayan Speed Records, Para-alpinism, and Passing Out on K2 appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Featuring vertical ice and mixed climbing at high altitude, it was of the hardest lines in the Himalaya 46 years ago. Despite many attempts it’s repelled a second ascent until now.

The post After 46 Years Changabang’s Massive West Wall Has Finally Been Repeated appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

In the history of high altitude climbing, there are few ascents that have become legendary—in the truest sense of the word. A cutting-edge ascent, done in good style, is not nearly enough to become legend. Instead, the climb must be attempted, again and again, each failed ascent contributing to the lore surrounding the route.

Such is the case for Changabang’s (6,864 meters) immense West Wall, which has 1,600 meters of steep granite relief and was originally done in 1976 by the British alpinists Joe Tasker and Pete Boardman. Unlike the large-scale siege expeditions of the era, Tasker and Boardman’s lightweight team made the six-mile approach to advanced base camp as a team of two and began a 21-day odyssey up the wall, finding difficulties up to 5.10 and 90-degree ice. Factor in the thin-air, the brutally cold weather, and the long descent back to basecamp, the duo’s 40-day journey must have felt like ascending into another planet.

On May 2 this year, 46 years after the first ascent, Kim Ladiges and Matthew Scholes from Australia and Daniel Joll from New Zealand made the second ascent of the West Wall. While they undoubtedly followed in the footsteps of the legendary alpinists before them, their ascent opened roughly 20 pitches of entirely unclimbed terrain—a significant variation to the original route.

The team

“Two plus two equals four, five, six, or maybe even seven.” Daniel Joll told Climbing, to explain his belief that a “highly functioning team is greater than the individual sum of its members.” Joll said the team’s strength lay in its long history of climbing in the mountains together; among an untold number of attempts and failures, as pairs or as a trio, the team has ticked Cholatse’s North Face, Cerro Torre, the Grandes Jorasses North Face, and Taulliraju. These ascents have fostered a strong bond, Joll said, and allowed the group “to fail well, [which] builds real trust in your partners.”

Two years ago the trio decided that Changabang was their next great objective and resolved, with “complete commitment,” to be in fighting shape and develop a clear understanding of the route’s major difficulties.

Planning and training

The team reviewed the previous 20-odd attempts on the West Wall and realized that most teams failed due to logistical errors. Joll doubted that the West Wall’s technical difficulties would have stopped would-be suitors; it was the weather, the extreme cold, poor acclimatization, and lack of morale (or an excess of fatigue) from the extensive load carrying to the base of the route.

With this analysis in place, the trio developed a “rock-solid plan” for both the expedition and the fitness-focussed lead up; each member followed a three month program of cardio training supplemented with regular doses of outdoor climbing . Then, six weeks before their expedition, the team spent five weeks climbing in Chamonix together, dialing in their systems.

Shrinking Serac Opens Up Stout New Route on Mt. Hunter, Alaska

The climb

The team arrived at base camp on April 11 and began ferrying nearly 400 pounds of gear through steep moraines to their advanced base camp, six miles away, below the West Wall. Due to the tedious terrain, in their planning stages, the team had prepared to carry these loads for multiple weeks—but after just eight days of carrying their ABC was stocked and the team felt ready to blast off. They climbed and hauled from 5,150 meters up to 5,800 meters before fixing their ropes and returning to basecamp for two days of rest.

They set off again on April 25 with the intention of acclimating on their ascent, as Changabang’s neighboring peaks do not offer easy opportunities to acclimate. The team averaged 200–300 meters of ascent per day and, while slower than one would expect, Joll said this tactic worked well and thwarted the typical altitude-induced headaches.

The team carried two portaledges and one tent, a triple rack of cams, a full aid-climbing ensemble, ropes, an extensive piton rack, several sets of wires, 15 cans of gas, and ten days of food. The team was, no doubt, prepared for the terrain but the burden of hauling was evident on the many pitches of broken, blocky terrain. Thankfully, Joll said, Ladiges and Scholes are experienced wall climbers and overcame each obstacle smoothly.

Despite the massive wall before them, the heavy loads they hauled, and the constant possibility of frostbite, Joll said the team focused only on the task at hand: “During the load carries we never thought of what came next. Every carry was hard. We just focused on that day and said [that], as long as we get the gear to where we planned, tomorrow is a new day. … None of us ever thought we would summit. We never even imagined it could be possible until the final 100 meters. Every day we simply did our pitches and moved our gear, never thinking of how far we had to go, just the objective for the day.” This was another key factor to dealing with a route of this magnitude: “The sheer amount of effort required on a route like the West [Wall] can wear you down if you start thinking about all that is still to come.”

The team proceeded efficiently, never rushing but always in motion, with one person leading, another hauling, and the third cleaning the pitch and helping free the often-stuck haul bags. They had never a moment to relax, being busy from the morning “until the time the portaledge door got zipped up and we fell asleep.”

Looking back, Joll is adamant that it was the 22° F cold, not the technical difficulties, that were the crux of the West Wall. Indeed, 5.10 and steps of vertical ice may be within the realm of many experienced climbers, but tack on frozen, unfeeling hands and a shivering core? Joll recalled, “Climbing M5 and 80-degree ice at 6500 meters … I can tell you it’s bloody hard even when you’re just following and resting every few moves on your Micro traction.”

“Despite the fact that, after 46 years, we completed the first repeat of the famous Boardman-Tasker route, the ascent was a rather smooth affair,” Joll said. “Yes, we got caught in daily storms, one of which was very intense. … We had other minor dramas like on the final bivy where our tent started to slide off the small platform we had created on the edge of a 1000-meter drop. Needless to say we didn’t really sleep that night. Overall, though, this was a smooth ascent where teamwork and commitment paid off and we were eventually rewarded with a fine summit morning and a moment of warmth and sunshine just as we arrived at the final pitches of the climb.”

Federico Bernardi runs the Italian climbing-news website montagnamagica.com and gives his thanks to Daniel Joll’s daily trip diary for helping inform this article.

Ukranians Make Historic First Ascent on Annapurna III, Besting 40-Year Highpoint

The post After 46 Years Changabang’s Massive West Wall Has Finally Been Repeated appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Soloing Everest without supplemental oxygen, in winter, in alpine style, and by a technical route is no small task. How do you stack the odds in your favor? Adopt sport climbing tactics.

The post An Everest Winter Soloist On Practicing Redpoint Alpinism appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Two years ago, the 29-year-old Jost Kobusch announced his plans to climb the West Ridge of Mt. Everest (8,849 meters) solo and unsupported, in lightweight alpine style, in the dead of winter. Climbers and media makers from around the world chimed in, some with praise for the German’s idealistic and audacious goal, while others, including Reinhold Messner, criticized his inexperience and youthful vigor.

The skepticism may have been well deserved. At the time of his first attempt, Kobusch, though an already accomplished alpinist, had spent relatively little time at altitudes above 8,000 meters: on his first trip to Asia, in 2013, he attempted the 7,134-meter Pik Lenin; a year later, the then-21-year-old became the youngest person to free solo Ama Dablam (6,812 meters), one of Everest’s highly technical neighbors; in 2016 he soloed Annapurna (8,091 meters) without supplemental oxygen; and in 2017 he soloed the unclimbed Nangpai Gosum II (7,296 meters) placing him on the shortlist for that year’s Piolets d’Or.

With this resume, or perhaps despite it, Kobusch said the idea to attempt Everest’s West Ridge came easily. “I was just asking myself what was the most difficult thing I could imagine to do,” he told Rock and Ice in 2019. “Everest in wintertime—you will basically get a real adventure, real alpinism. Not just standing in a traffic jam.”

Indeed, soloing the West Ridge in winter without external support is the most difficult thing many climbers could imagine doing. For context, Cory Richards, the only American to summit an 8,000-meter peak in winter, considers climbing Everest in spring by the normal route (South Col) an incredibly serious undertaking if done without supplemental oxygen. So to take on the 60-degree Hornbein Couloir, with so little margin for error, the criticisms and concerns for Kobusch are understood.

This article is free. Please support us with a membership and you’ll receive Climbing in print, plus our annual special edition of Ascent and unlimited online access to thousands of ad-free stories.

During his first attempt, Jost acclimatized on several 6,000-meter peaks, including one then-unclimbed, before making several trips from his base camp to Lho La Pass at 6,006 meters. From there, Kobusch’s high camp sat 3,000 meters horizontally from the summit, and almost as many beneath it. He made steady progress up to 7,400 meters, including a particularly steep mixed section, before ending his expedition after two months of effort.

Kobusch returned to Everest in autumn 2021 for this second attempt of the West Ridge. His main goal of this expedition was to reach the start of the Hornbein Couloir at 8,000 meters, and he acknowledged the unlikelihood of summitting Everest on this attempt. But Kobusch doesn’t believe that low odds of success should deter him from trying. Just like in sport climbing, where one builds familiarity and strength by trying their project, Kobusch aims to redpoint Everest in a similar manner.

Reinhold Messner, one of the most accomplished Himalayan alpinists of all time, disagreed with this approach. “It is all PR,” he told the Nepali Times. “He said he has only one percent chance, if that is so he should stay in the Alps, do smaller things successfully, or climb the challenging six or seven thousanders first.”

Climbing caught up with Kobusch while he rested at the Italian Pyramid Research Station, near Lobuche, to learn more about how his expedition is going, his redpointing tactics, and his goals for this attempt.

Note: This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Climbing: How are conditions on the route compared to your first attempt?

Kobusch: The conditions compared to last time are definitely more icy. I think there was more sunshine and warmer temperatures leading up to this condition and when it finally snowed the slopes were already so icy that the snow just glided down. Therefore it’s a bit more tricky to deal with the wall leading up towards Lho La and I followed a slightly different line to avoid objective dangers like avalanches on this attempt.

From Lho La up to 6,450 meters, it looks like I’m under this huge serac [on my live-tracking map] which looks very dangerous, but it’s actually pretty safe and sheltered by rocks. Anyway, the route changed a lot in conditions from my first attempt. I’ve seen a lot of potential dangers.

Did you plan to establish a cache camp at Lho La Pass similar to your 2019 attempt? How much weight are you carrying?

This year I don’t have a base camp. I’m staying close to the village of Lobuche, in the Pyramid Research Center, so I established some kind of advanced base camp at 5,700 meters and that’s where I have my cache, halfway up to Lho La Pass. It’s in the middle of the wall below a cliff and it’s pretty protected. This way, when I go on the route I can reach the advanced camp within a few hours.

My backpack weighs around 35-40 pounds. For winter expeditions you are more defensive so you carry more insulation, more gas, a shovel to establish camp, and this makes my pace slower because I want to be safer and, you know, considering the margin of error is smaller.

Your goal for your second attempt is to reach an altitude of 8,000 meters and gain access to the Hornbein Couloir. What is your intended strategy for the next rotations?

I think I will put Camp Two where you last spotted me [on the tracking map] at my high point (6,457 meters). I think I would have one more camp above that and then go lightweight and put a last camp behind the West Ridge, to avoid the strong winds. And then the plan would be to traverse into the Hornbein Couloir. I mean, that’s the plan. Let’s see how it works out. It could very well be that I’ll put up more camps, preparing for potential storms or if bad weather forces me to bivouac.

Strategy…well this project is huge and I personally believe that no other project could prepare me for this better than the project itself. The idea is you go, you try the moves, you learn a lot, you come back, you try the same route, until you’re finally able to climb the route. I’m using this slow approach here. It’s like going exploring. Focusing on learning as much as possible. The chance of success is small but with every attempt they increase and increase. And, I mean, what I really enjoy about this project is this journey into the unknown. I’m really curious what I’m going to find out there because nobody knows and I’m really curious about what I’ll be able to do. This key curiosity is the main driver of the project.

The post An Everest Winter Soloist On Practicing Redpoint Alpinism appeared first on Climbing.

]]>