A trad climber on Mont Blanc attempts to bump a blue Totem and falls with the piece in his hand. Here's how to avoid that.

The post Weekend Whipper: Trad Climber Tries to Bump a Cam—Then Rips It Out appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Readers, please send us your Weekend Whipper videos using this form.

George Zhuravlev was high in the Alps and out of gear.

At more than 11,000 feet, Zhuravlev was leading a 0.3-sized finger crack on the fifth and final pitch of C’era una Volta il West (5.12a), a trad route on Rognon Vaudano below the Mont Blanc massif. He had just placed a blue Totem, but needed another one.

So Zhuravlev did what so many trad climbers do in this scenario: He grabbed his blue Totem and bumped it higher.

Unfortunately, just before he could re-place the Totem, his foot slipped. Zhuravlev flew off the wall, landing with a yell at 15 feet below his original position. When he landed near his belayer, he was still holding the piece he’d removed.

The dangers of bumping cams

Bumping—adjusting a cam to move it higher up—is risky for exactly this reason. While a cam is being moved, it’s not primed to catch the rock. Nevertheless, the move is very popular for trad climbers who accidentally run out of gear.

Jeff Jaramillo, the Head of Outreach and Gear Education at WeighMyRack, says that he most often sees people bump a cam when they get scared and want the rope above them. Zhuravlev’s case, he says, is a “prime example” of how bumping can end up extending a fall.

Not all bumps carry the same level of risk. For example, in offwidth climbing, climbers will often bump two pieces—one at a time—to ensure that one piece is always set in place to potentially catch a fall. When executed correctly, this strategy has the added benefit of keeping the rope out of the way of the climber’s knees and thighs.

Some gear is also easier to bump than others. According to Jaramillo, the design of a Totem cam, like the blue Totem that Zhuravlev was using, requires a lot of tension to load and unload. He finds that a stiffer cam, such as a Black Diamond C4 or Wild Country Friend, lends itself to bumping a bit more. “When it’s already placed in a crack and you give it a little bit of a push, it automatically starts to squish the lobes in a little bit,” Jaramillo explains, “so you don’t need as much pressure to collapse this style of cam as you do to collapse the Totem.”

Jaramillo’s advice for bumping

1. Bring more gear. “I generally try to avoid needing to bump a cam because that usually means that I’m not as prepared as I would want to be,” says Jaramillo. “For people getting into trad climbing, the things that you should look out for are, do I have all the gear that I’m going to need?” Don’t be afraid to add a few extra cams to your harness, especially if you’re new to leading trad.

2. Leapfrog your pieces. “Some people will backclean, where they’ll reach below themselves to grab a previous piece of gear—not the last one, but the one before it,” says Jaramillo. If the top piece is bomber, this practice minimizes the fall that could occur in transition.

3. Keep the piece in the crack. “If I was in [Zhuravlev’s] situation and really wanted that cam to be higher, personally, I would have wanted to just slightly disengage the cam, keep it in the crack, and push it upwards,” says Jaramillo. This move is slower but slightly safer than just pulling the piece out of the crack entirely and placing it higher. But it still doesn’t guarantee safety. “One of the things that happens when you fall is that you tense up, so you probably squish those lobes even more,” he adds. If you’re squeezing the lobes at all, assume that cam will be flying out with you.

4. Don’t bump until you’re totally secure. “When you are in a situation where you are bumping, the recommendation is usually to get to a spot where you’d be placing a piece again, and then bump to where you’d place the new piece,” says Jaramillo. Avoid adjusting your gear during a crux move or when you’re pumped.

5. Take. “If all you have is that one piece in front of you and you really need it to get higher, most of the time, I will just take,” says Jaramillo. “It’s so much easier to set the ego down for a second … if you’re scared or you’re pumped, and you’re right at that cam, take. Hang out for a second. Relax. Breathe. Get all the juices flowing where they need to be going again. Get thoughtful about where you’re going to go.” After a break, pull back on with a fresh mindset and bump the cam with full energy.

Happy Friday, and be safe out there this weekend.

The post Weekend Whipper: Trad Climber Tries to Bump a Cam—Then Rips It Out appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

The 11 best climbing pants for sport, bouldering, trad, the gym, and more—plus our pant pick for all-around climbing.

The post We Tested 42 Different Climbing Pants. These Pairs Came Out on Top. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Take a look around any crag and you’ll likely see a wide variety of climbing pants. Sure, there are plenty of climbers wearing purpose-built pants with four-way stretch and techy features. But we also see people climbing in leggings, billowy linen, the occasional Lycra tight, Carhartts, and denim (the horror!). While there are many pants that you can make work for climbing, if you’re in search of the best climbing pants, you’re in the right place. We put dozens of pairs to the test, from technical bottoms and department store leggings to burly workwear.

To help guide you toward the best pair, we identified the top all-around rock pants for anyone who doesn’t want to invest in multiple pairs. We also picked top pairs for sport climbing, bouldering, the gym, and trad/multi-pitch/alpine.

Searching for climbing pants for women? While we offer recommendations for both men and women here, we also created a separate women’s-specific guide to the best pants with more detail and additional recommendations.

The post We Tested 42 Different Climbing Pants. These Pairs Came Out on Top. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

The Trump administration is looking to roll back a 2001 protection for 44.7 million acres of forests. Here's what climbers need to know.

The post Rescinding the Roadless Rule Threatens These 13 Climbing Areas appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

On June 23, 2025, U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Brooke Rollins announced that the Department of Agriculture (USDA) intends to rescind the 2001 Roadless Rule, also known as the Roadless Area Conservation Rule.

If the rescission takes effect, it will free up logging and road construction on 44.7 million acres of National Forest land, mostly across 10 Western states.

“For nearly 25 years, the Roadless Rule has frustrated land managers and served as a barrier to action—prohibiting road construction, which has limited wildfire suppression and active forest management,” said Forest Service Chief Tom Schultz in the USDA press release.

The Sierra Club, a conservation organization that opposes rescinding the Roadless Rule, has called Schultz a “corporate lobbyist” for the timber industry. “The Forest Service followed sound science, economic common sense, and overwhelming public support when they adopted such an important and visionary policy more than 20 years ago,” said Alex Craven, the Sierra Club’s Forest Campaign Manager, on August 27. “Donald Trump is making it crystal clear he is willing to pollute our clean air and drinking water, destroy prized habitat for species, and even increase the risk of devastating wildfires, if it means padding the bottom lines of timber and mining companies.”

Outdoor Alliance, the same organization that created a digital map for Utah Senator Mike Lee’s proposal to sell off public lands earlier this year, estimates that 8,659 climbing routes will be affected, but Access Fund says that the number is actually over 10,000.

“[R]escinding the Roadless Rule is a direct threat to the backcountry climbing experience,” wrote Access Fund on August 29.

Which climbing areas does the Roadless Rule affect?

A digital map published by Outdoor Alliance reveals that the Roadless Rule currently protects both backcountry climbs and roadside crags on National Forest land. Colorado and Idaho have their own, state-specific versions of the Roadless Rule, which are not affected by the USDA’s action.

The following is a non-exhaustive list of climbing areas, identified by Climbing editors, that could see new construction with the USDA’s new policy:

- The Wind River Range, Wyoming

- Ten Sleep Canyon, Wyoming

- Bighorn National Forest, Wyoming

- Darby Canyon near Grant Teton National Park, Wyoming

- The Needles, California

- Climbs near the Whitney Portal, California

- Little Egypt near Bishop, California

- Upper Park Rock near Monticello, New Mexico

- Ruby Mountains, Nevada

- Portage near Anchorage, Alaska

- The Dikes near Dayton, Washington

- Upper Park Rock, New Mexico

- Little Cottonwood Canyon, Utah

What’s next?

The USDA is accepting public comments on its rescission proposal through September 19. In the first 10 days, more than 60,000 comments were received.

After the initial public comment period, the USDA will release a draft environmental impact statement (EIS), followed by a longer public comment period.

Climbers can also send comments through Access Fund’s simplified tool.

The post Rescinding the Roadless Rule Threatens These 13 Climbing Areas appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

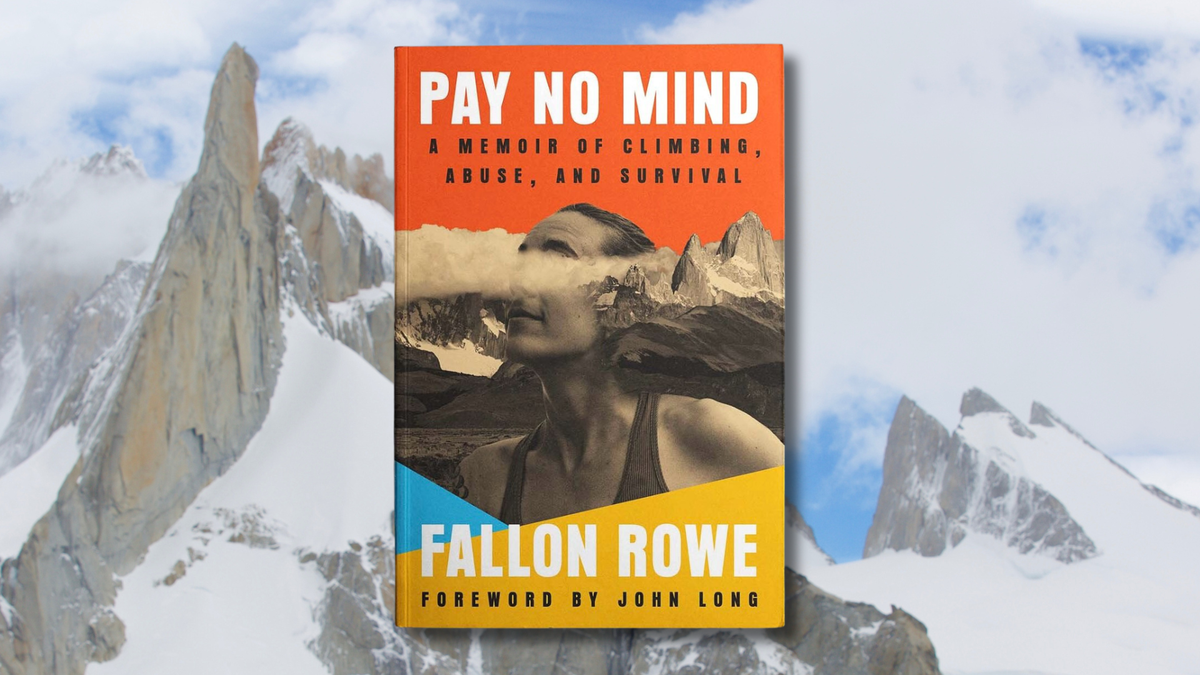

An exclusive interview with the debut author of 'Pay No Mind'

The post “It Felt Like An Exorcism”: Fallon Rowe on Writing Her Memoir of Climbing, Abuse, and Survival appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

In the past few years, the climbing community has seen several harrowing stories of violence and abuse come to light in the news. Formerly prominent climbers like rapist Charlie Barrett, domestic abuser Lonnie Kauk, and child rapist Alex Fritz have proven that celebrated individuals in the climbing world can still act as predators for many years. Last spring, the organization Never Solo was founded to address abuse in climbing specifically, calling the climbing community “tight-knit” and emphasizing the need to understand how toxic and violent behavior shows up in our spaces. Now, a new climbing memoir offers an insightful and deeply personal perspective to surviving abuse.

In Pay No Mind, set to release on November 25, Utah climber Fallon Rowe recalls her experience with (and ultimate escape from) a controlling and dangerous partner. The story follows Rowe (rhymes with now), then a 19-year-old geology student in northern Utah. When her charismatic new boyfriend convinces her to empty her savings and fly to Patagonia to climb the iconic Fitz Roy, Rowe finds herself fighting for her autonomy, independence, and survival both on and off the mountain.

Read an exclusive excerpt of Rowe’s debut here, then check out our conversation below.

Climbing: Why did you decide to write this story into a memoir? And why now?

Fallon Rowe: Some stories will eat you alive as a writer until you finally relent and force them out onto the page. What happened to me was so dark and transformative, I knew I had to write it into a book. It’s an almost unbelievable series of events. I had no other way to explain to people what happened to me since it was so wild.

I started working on the manuscript right after I escaped in 2017, but my ex-partner threatened me when he learned about the project, so it simmered on the back burner for years. In 2022, I had a paid summer off from my job as a full-time high school science teacher, which allowed me to sit down and write the entire book in around six weeks. It felt like an exorcism to finally let it all out, like some kind of insane release. I spent the last few years querying agents and publishers. In spring 2025, I finally got the email every new author dreams about: the publishing offer for Pay No Mind from Di Angelo Publications.

Climbing: Pay No Mind shows the dark side of following a more experienced climbing partner into the mountains—something many climbers can relate to doing. After surviving the events of this book, how do you now evaluate new potential partners?

Rowe: I know red flags to look for now in potential romantic or climbing partners. Before taking on a serious objective together, I know how important it is to be on the same page and be properly prepared. When I evaluate new climbing partners, of course the bare minimum is safety and competency. Beyond that, I prefer to climb with folks who have a positive attitude in the face of challenges, who are good communicators, and who are understanding of my health problems.

Climbing: Have you returned to Patagonia since the events of Pay No Mind? Do you intend to?

Rowe: I haven’t, and I don’t intend to. That’s not the kind of climbing I’m interested in anymore. If I had the opportunity someday, it would be fun to go back just to hike and make better memories since it’s a beautiful landscape.

Climbing: In your story, you alternate between feeling free and feeling trapped. You write, “Freedom cannot be given or received; you must reach out, grab it, and hold on like hell.” What are the steps you take in your daily life to preserve or expand upon this freedom?

Rowe: I keep freedom in mind every day. Honoring your autonomy is an important part of Stoic philosophy, which informs every part of my life. When I was in the abusive relationship and climbing partnership detailed in Pay No Mind, I lost myself and my independence. I’ll never let that happen again. I have an extremely strong sense of identity, and I’m always examining my life—checking that I’m making decisions that align with my goals and values.

I can’t stand feeling trapped or stifled, so I’m mindful of setting up my life in a way that leads to freedom. I try to have jobs, relationships, and interests that allow me to live in an unbridled way, so I can explore and express myself however I want. Where I choose to live is also a key part of this. I love southern Utah. I can go off into the desert to climb, run, hike, camp, and just exist without anyone bothering me. It’s like the wild West. Totally free.

Climbing: What was the hardest part about writing this story?

Rowe: Getting over the fear of my ex coming after me for sharing the story. That’s no longer a concern, which has been a relief.

Otherwise, it was very difficult to put myself back in the mindset of my nineteen-year-old self. There’s a lot of vulnerability when writing from the perspective of your younger self. I’m not that girl anymore, but to do the story justice, I had to be true to the person I used to be, no matter how much I judge or disagree with her decisions now. It’s scary to admit to the things I allowed to happen, to the ways I was complicit … but ultimately, I had to tell the whole truth, and get over myself. I hope readers know that’s not who I am anymore, but I’m not ashamed either.

Climbing: Besides being a climber and writer, you juggle a lot of different jobs. What are they, and how do you find the time to write?

Rowe: Since I quit teaching, my career has been a mosaic of my interests. Right now, I’m working full-time at an outdoor gear shop, but I’m looking for a regular remote gig so I have more stability and flexibility—ideally as a writer, but who knows what will happen. In addition to that, I run a climbing coaching business called Sage Sending, which is extremely rewarding. I’m a climbing guide; I teach trad and crack climbing clinics. I write blogs for another guiding company in Zion. I’m an athlete for a few climbing brands, so I always have sponsorship duties to complete. I do freelance graphic design and cartography for a development firm. I’m also a climbing photographer. I’m the Vice President of the St George Climbers Coalition, and I serve on the board for The Highpointers Foundation. I also sometimes contract with Conserve Southwest Utah as a geoscience researcher and writer. It sounds crazy when I list it all out like that, but I somehow juggle it all.

My daily schedule is typically random. I have my set work shifts, and then I fill in the gaps with everything else—writing, training, climbing, trail running, appointments, emails, dating, meetings, and coaching calls. My calendar looks totally ridiculous. But it’s important for me to have time for other interests as well, like reading books, playing fiddle, chess, and billiards, and practicing archery, Spanish, and Latin. I have a full, stimulating life. I think most people waste a large portion of their time and their intellectual and athletic potential.

Finding time to write is more of a compulsion than a decision. My brain tells me when it’s time to write, and then it is unstoppable, no matter what else I’m ‘supposed’ to be doing. I’m writing a novel right now, which I’m thrilled about, and a book on climbing mental performance. My priorities are being the best climber I can be, taking care of my body (I have multiple chronic illnesses), living true to my philosophy, and writing whenever possible.

Climbing: You mentioned in your afterword that you have other stories you want to tell. What about this one inspired you to tackle it first?

Rowe: This story was a simple choice because it stands out as one of the defining eras of my life. There’s a before and there’s an after, like a big dividing line in my development. I also felt a strange mental block, like I had to write this before my brain would allow the floodgates to open for other projects, almost like I owed it to myself to finish this first. Now I feel like I can finally move on, and my creativity is back.

Climbing: You have a tattoo of the coordinates to City of Rocks, Idaho. How would you describe City of Rocks to someone who’s never visited?

Rowe: City of Rocks is a quiet wonderland of granite tucked away in the Idaho countryside. It’s packed with gray crystalline domes and fins of rock in a huge labyrinth with trees, sagebrush, creeks, and trails scattered throughout. The weather is fickle. The rock is perfectly grippy with incredible patina crimps, neat cracks, and demanding technical climbing that is often spooky or ‘old school’ in nature. It’s my favorite place ever—home.

Climbing: Legendary Yosemite Stonemaster John Long wrote the foreword to your book. How did he get involved in your publishing process, and what was it like to work with him?

Rowe: Sequoia Schmidt, the owner of Di Angelo Publications, is friends with John, and he’s published a number of titles through them. She told me that they’d only publish my memoir if I agreed to work with him on revisions first. I was over the moon at the opportunity to learn from a legend! I’ve looked up to him since I was seven years old. It felt surreal to get to work with him during our months of meetings and revisions. Initially, I was nervous, but he’s become an amazing friend through the process. He was truly perfect for me as a mentor on this project because of his skill as a writer, knowledge about climbing, familiarity with addiction and mental illness, and wisdom about abuse and toxic relationships. He showed incredible compassion for my story and struggles, and has been a key supporter in my life this year.

During the revision process, I appreciated his straightforward feedback. He doesn’t waste time. Cuts through the crap. He has a very raw, simple style. Somehow ruthless and gentle simultaneously. His biggest focus was on expanding the internal storytelling—showing more of my emotions and thoughts to help readers connect with me. He also helped me incorporate more narrative shift—including flashbacks or stories from my younger years, and also occasional insights from my current self. I’m extremely grateful for his help, and honored that he wrote the foreword to my book.

Climbing: Now that this project is finished, what does Patagonia represent to you?

Rowe: A large portion of the story occurred in Patagonia, so of course I’ll always associate those memories with it. It’s epic and intimidating, stunning and dramatic. To me, it represents a turning point in my life and climbing. I never thought I’d get to visit a place like that, and once I did, it was like the world opened up to me.

Climbing: In the past few years, climbing has seen a few high-profile stories of violence and abuse from prominent male climbers, including Charlie Barrett and Lonnie Kauk. What do you think people in the climbing community can do to help counteract this problem and support potential survivors?

Rowe: I think the climbing community is largely wonderful, but unfortunately, there are problematic and dangerous characters in every space. We all need to do our part to root out misogyny, abuse, and other unacceptable behaviors. Any time people see something, they should say something (if it’s safe to do so) or report it if needed. Recognizing when there’s something bad or sketchy happening, and then not tolerating it, is a good start. We can call each other out, we can look out for our friends and community members, and we can challenge one another to do better (with our language and our actions). We can make it clear that the climbing world will not tolerate abuse or violence. We should focus our concern on the people who have been harmed, protect them, and trust their stories. There are far too many detrimental misconceptions about victims, and unnecessary blame or mistrust of their experiences. Changing the culture will take time and bravery. Charlie and Lonnie were unique cases because they both had power and status to shelter them, but I think most abusers are a lot more low-profile, hiding within the ranks, like my ex, so we need to stay vigilant.

To support survivors, resources are often the biggest issues, whether that’s financial to help them get out and live on their own, or access to things like therapy. They need to have a safety net in place so they feel no need to go back to their abuser. Friends can provide support by listening without judgment, by giving them safe places to stay, and by defending them online if they choose to speak out. We can all try to make our crags and gyms welcoming places.

Excerpted from Fallon Rowe’s debut novel, Pay No Mind: A Memoir of Climbing, Abuse, and Survival © 2025 Di Angelo Publications. Reprinted with permission. Pay No Mind is available for pre-order at https://www.diangelopublications.com/shop/p/pay-no-mind until release on November 25, 2025.

The post “It Felt Like An Exorcism”: Fallon Rowe on Writing Her Memoir of Climbing, Abuse, and Survival appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Shannon “SJ” Joslin was fired from Yosemite for helping rig a trans pride flag on El Capitan. They're calling it a First Amendment violation.

The post “I Want My Job Back”: Yosemite Biologist Fired for Displaying Trans Pride Flag on El Cap appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

This is a developing story and will be updated periodically with more information.

Last Tuesday, Yosemite wildlife biologist Shannon “SJ” Joslin was called into a meeting with Danika Globokar, acting deputy superintendent of Yosemite National Park. A law enforcement ranger was also present.

Dr. Joslin, who holds a PhD in genomics, soon found out why. Globokar handed them a letter, which said that the Yosemite bat expert was being terminated for “failure to demonstrate acceptable conduct” because they had helped fly a trans pride flag on El Capitan on May 20.

According to Dr. Joslin’s account of the termination letter, the flag display violated 36 CFR § 2.51, a National Park Service (NPS) rule against any demonstrations that take place outside of designated park areas for First Amendment activities.

Dr. Joslin was shocked that termination was the first response to this. They told Climbing, “I looked at the rubric for recommended disciplinary action for if you have a demonstration outside of a First Amendment zone, and the recommendation for a first-time offense is a reprimand.”

But Dr. Joslin was not technically a permanent employee, even though they have been working in the same role, as the head of Yosemite’s Big Wall Bats program, for four years. “They got me in a loophole,” they said. “When I transferred into my career seasonal position, I was a disability hire, so I have a two-year probationary period instead of one.” Their probation was set to end on September 10, just 29 days later.

The NPS confirmed that they are “pursuing administrative action against NPS employees in Yosemite National Park for failing to follow NPS regulations.” Their spokesperson declined to comment on Joslin’s case.

About the El Cap trans flag display

The May 20 flag display, which included Dr. Joslin, environmental activist Pattie Gonia, and five other trans climbers and allies, lasted for about two hours on a Tuesday morning. From 9 a.m. to 11 a.m., the flag billowed 15 to 20 feet away from El Capitan on Heart Ledges, about one-third of the way up. It did not block any climbers. Joslin adds they were not on duty and not in uniform when they assisted with the rigging.

“We want to make sure that trans people know they’re welcome outdoors,” Dr. Joslin told Climbing at the time about the motivation for the display. They called it a celebration, not a protest, and said that they didn’t necessarily disagree with people who said El Cap shouldn’t be a community message board. “If there were rules saying that we couldn’t hang a flag from El Cap, then we wouldn’t have hung a flag from El Cap,” they explained.

The timeline of the Yosemite flag ban

The day after the flag display, the Yosemite Superintendent’s Compendium was updated with a new clause that banned flag displays. Specifically, the new rule stated that no person or group may “hang or otherwise affix to any natural or cultural feature, or display so as to cover any natural or cultural feature, any banner, flag, or sign larger than 15 square feet (e.g., five feet by three feet).”

The update is dated May 20—the same day as the flag display—but the digital signature on page one shows that the Acting Superintendent signed it into effect on May 21.

“I’m going to try and fight this thing”

Dr. Joslin was in the midst of turning in their badges when they spoke with Climbing. “I’m going to try and fight this thing and get my job back,” they said. “I don’t make a lot of money in the federal government; I don’t really have a large means to hang onto.”

In a press release from Dr. Joslin, the ex-employee wrote that their dismissal is in direct conflict with President Trump’s recent Executive Order 14149, “Restoring Freedom of Speech and Ending Federal Censorship,” which was signed on January 20. The order mandates that no federal government officer, employee, or agent “engages in or facilitates” any conduct that would unconstitutionally abridge the free speech of any American citizen.

“In my eyes, I should have First Amendment rights as a private citizen,” explained dr. Joslin. “Nothing that I did [regarding the flag] was on work time or associated with work. I don’t know how my conduct as a wildlife biologist has any ties to this at all.”

Pattie Gonia, who added to the press release, said that Dr. Joslin’s firing is “a targeted move by the Trump administration to silence voices that hold viewpoints different than their own.”

In the meantime, Dr. Joslin plans to seek legal counsel. “My firing isn’t just about one ranger,” they wrote. “It’s about whether everyone has the right to speak freely in the United States.” Their supporters have launched a GoFundMe for their bills, groceries, and potential legal fees.

The post “I Want My Job Back”: Yosemite Biologist Fired for Displaying Trans Pride Flag on El Cap appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Devin “Fin” Finucane, who has more than 600 first ascents in the Creek, is not allowed to return for one year.

The post Indian Creek’s Biggest Route Developer Just Got Banned for Camping for Too Long appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

This is a developing story and will be updated periodically with more information.

If you’ve climbed more than a few pitches in Indian Creek, Utah, the crack climbing capital of the U.S., you’ve likely come across a route with “DF” initials carved into a plaque at the base of it.

That’s how Devin “Fin” Finucane prefers to mark his first ascents. Over the past 31 years, Finucane has established 665 new routes, including a host of offwidths and chimneys, in Indian Creek, according to his Climbing Majority podcast appearance in late March.

“I think when I last talked to [Finucane], he’d already done his 666th,” says Joe Stern, who is actively compiling a new guidebook to replace Karl Kelley’s Creek Freak. He says that Finucane is the biggest route developer in the area, which includes more than 3,000 routes.

For the time being, however, that 666 number won’t be going up.

On June 12 of this year, Finucane was cited for camping for longer than 14 days in a 30-mile radius on federal land near Indian Creek. Unfortunately for the route developer, a history of prior citations resulted in his case escalating to a one-year ban.

The deal

On July 11, Finucane agreed to observe a one-year ban from 3.6 million acres of public land, including all of Bears Ears National Monument and most public land in southeastern Utah. Specifically, he agreed to avoid any federal public land managed by the Canyon Country District of the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), although he is allowed to pass through on public roads for “necessary travel.”

If he breaks the terms, Finucane will incur an extra, five-year ban from all federal public lands in the state of Utah, as well as a fine and “additional penalties.” Otherwise, he can move to dismiss his guilty plea to the overstay violation.

According to court records, the deal still allows Finucane to climb in non-BLM-managed lands surrounding Bears Ears, including Canyonlands National Park.

Is this the norm?

“It is uncommon for a judge to ban a person from public lands,” says Anna Rehkopf, the Public Affairs Specialist for the Canyon Country BLM. “Generally, this only occurs when there are repeated violations and/or extenuating circumstances.”

First-time offenders can usually expect a warning or a fine of $100 plus $25 per day. Repeated citations will result in a mandatory court appearance and higher fines, according to Rehkopf.

The BLM says that overstays on public land in southeastern Utah have increased over the last few years. “The longer people stay, the more they tend to sprawl,” she says. “Additionally, with new opportunities for internet connectivity in Indian Creek, we are seeing remote working leading to extended stays.”

Fewer new routes in the Creek

Being a first ascensionist in Indian Creek has gotten harder. Earlier this year, Bears Ears National Monument adopted a new management plan that prohibited bolting new routes without BLM and Tribal approval.

Finucane told Climbing that he’s been following the new first ascent regulations, only replacing old anchors around the Creek. “I put up no new routes since the ban. I’ve only updated old anchors this past spring,” he says.

Regarding the ban, Finucane confirmed that he was punished for going over the 14-day camping limit but declined to provide further detail. On July 25, he announced on social media that he will be “staying cool in the alpine until the desert cools down.”

The post Indian Creek’s Biggest Route Developer Just Got Banned for Camping for Too Long appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

The U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee has issued clear orders. But evidence that trans female climbers have a competitive advantage is lacking.

The post Why Did USA Climbing Just Ban Trans Women From All Events? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Liam Hurlburt was afraid to win.

On a sweltering Saturday last August in El Paso, Texas, she stepped onto the black mats of the Sessions Climbing and Fitness climbing gym. A nondescript house beat pulsed through the building. She faced the crowd with a smile and reached into her red chalk bag. It was the final round of Crossroads, the annual bouldering competition at Sessions.

When the announcer yelled, “Go,” Hurlburt spun to the wall with a brush and scrubbed at the slab problem’s footholds. At first, she struggled to balance onto a sloping volume and perform a leg-twisting back step. On her fourth attempt, she slammed to the mat, casting up a poof of chalk. Somehow, she held her balance on the fifth go. From there, she climbed opposing side pulls to the top. She dropped and waved to a whooping crowd.

“One more time for Liam!” bellowed the announcer. “Let’s put our hands together and make some noise!” Hurlburt hurried back to the isolation area, trying to smother a smile.

Hurlburt, a 27-year-old trans woman, was particularly anxious about the prospect of doing well. “I was like, ‘What the hell am I doing?’” she remembers. “I’m about to literally get on stage as an openly out trans woman competing in finals. That felt really scary.” Her first-place win at a recreational comp the previous year had resulted in more than 12 months of hate emails and texts, and she didn’t want to repeat that experience. She just wanted to climb.

“Going into it, I was like, do I actually want to try my hardest?” she says. “Do I actually want to be a contender? Because I was worried about pushback. This is Texas. It’s not my home gym … I didn’t feel like it was entirely permissible for me to win.”

For the past 18 months, USA Climbing has worked hand-in-hand with transgender climbers to develop an inclusive policy that would allow a path for competitors like Hurlburt to participate in the category that matches their gender identity. By late July, this policy was 95% complete. Then the organization made a screeching U-turn.

On July 22, USA Climbing announced that due to President Trump’s Executive Order, trans women would be banned from all sanctioned events. “The U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee (USOPC) recently updated its Athlete Safety Policy, requiring all National Governing Bodies to comply with Executive Order 14201,” USA Climbing wrote in an email to its members. In effect, this update prohibited transgender women from competing in all women’s categories at USA Climbing events.

“This isn’t USA Climbing’s desired policy,” says Marc Norman, the CEO of USA Climbing. He emphasizes that the USOPC could decertify USA Climbing if it doesn’t comply with the new directive to align with President Trump’s Executive Order 14201, which specifically targets trans female athletes.

With this ban set to begin in October, gym owners, coaches, climbers, and USA Climbing officials have some important decisions to make. What will the world of indoor competition climbing look like, for everyone involved?

Why we don’t see many trans women in climbing

Indoor climbing has not seen a transgender female athlete participate, much less dominate, the women’s competition at an elite level. At the time of this article’s publication, zero openly trans women in the U.S. have competed in an IFSC World Cup, a National Championship, an Olympic event, or any competition in the USA Climbing Elite Series.

USA Climbing, which had almost 19,000 members at the end of 2023, was not able to provide an estimate for how many trans women compete today, but a member of their policy-writing group estimates “dozens, but not hundreds” climb across all age divisions, including the Paraclimbing Series and Youth Series.

Vera May, a trans woman and New York-based climber who formerly coached at USA Climbing events herself, puts the number below 20 people total. “I have not seen proof there were more than 10 or 20 trans feminine climbers in USA Climbing, youth or adult, in any capacity,” she says. “If you gathered the 20 best trans women rock climbers in the world in a room, I would be in that room, and I cannot even compete against the 50 best 11-year-old girls. Nikki Smith is astounding; Lu [Gondeim de Alencastro] is my favorite climber alive … but on the whole, trans women that climb above 5.12 or V6 are extreme outliers.”

May also suggests that blocking testosterone and increasing estrogen—the two main components to feminizing hormone replacement therapy (HRT)—contribute to this trend. Trans women, she says, become disadvantaged in climbing during HRT “because now, we just have really heavy bones and no testosterone. After being on HRT for two years, it’s like building muscle and getting stronger is actually impossible because my bones are so heavy and my muscles don’t work.” She adds that people should question if trans women actually have any sort of physiological advantage over cis women in comp climbing.

Hurlburt, who completed feminizing HRT in 2020, remembers not wanting to start her medical transition because she knew that the hormone therapy would make her weaker. “I literally can’t dyno anymore,” she recalls. “Before transition, I had a surplus of power and would just muscle through things. Post-transition, I don’t have that power and that fast-twitch muscle mass especially.”

A “groundbreaking” policy is shelved

When Kristen Fiore got USA Climbing’s email, she wasn’t surprised, but she was disappointed.

Fiore is a Vermont-based climber and a cofounder of Trans Climbers Belong (TCB), an advocacy group that sprung up in October 2023 in response to USA Climbing’s new Transgender Participation Policy. This policy mandated that trans female climbers provide medical records for at least one year indicating that their testosterone levels are below five nanomoles per liter, which is 50% lower than the maximum testosterone levels allowed by the International Federation for Sport Climbing (IFSC).

The new rules drew enormous criticism from trans activists and allies. “You’re saying that you need a 12-year-old to be on gender-affirming hormone therapy for at least a year,” says Cat Runner, another TCB cofounder. “In 24 states, that’s not legally accessible to them.” (That number is now 26).

After coordinated backlash by TCB and trans allies, USA Climbing paused their new policy in November 2023, just two months after it was released. For their second attempt, the organization met with TCB members, collected survey feedback, and launched listening sessions hosted by trans facilitators. Fiore herself joined the Transgender Athlete Participation Policy Revision Group to help craft a new set of regulations. Nearly a year of deliberation followed, during which Fiore says USA Climbing made “so much progress.”

The July 22 email struck a heavy blow toward the goal she and her colleagues had been working toward for 18 months. According to Fiore, the trans participation policy they’d been developing was “95 percent done,” and only needed board approval. However, now that the USOPC has laid down a blanket ban, the policy Fiore helped negotiate will be shelved indefinitely.

“One of the things that’s going to get me really emotional is the fact that there were some really good things in this [policy],” Fiore tells Climbing. “I really believe this would have been one of the best policies that any national governing body has ever created. To invite trans and intersex athletes to the writer’s table is groundbreaking. That’s part of what makes this so heartbreaking.”

She declined to share details of the policy’s clauses, citing a non-disclosure agreement with USA Climbing. Norman disclosed that the policy was “quite detailed” and that it “allowed a path for participation” for trans female climbers.

“My body is shaped like a lot of other women’s bodies”

Hurlburt didn’t grow up as a competition climber. In fact, pre-transition, she tried a few local competitions and recoiled from them. “In the men’s category, it … felt very macho and ‘I’m going to prove that I’m better than you,’” she says. “It felt very competitive and antagonistic and it just wasn’t fun.”

But when she finally gathered the courage to pull herself out of a dysphoria-induced depression and start HRT, she quickly returned to the sport she loved. “I hardly did anything for six months,” she says. “Climbing was the last thing to go and the first thing I started up with when I got out of that hole.”

As she progressed through her transition, Hurlburt found stoke and support in other female climbers—and found herself actually enjoying competitions. Competing alongside other women felt more like a community atmosphere, with an “us versus the routesetters” mentality.

Being around other female climbers also helped Hurlburt push back on lingering feelings of dysphoria. “A lot of athletic women tend to be more on the masculine side,” she says. “Especially early in transition, my body is shaped like a lot of other women’s bodies because I’m a climber. If I’m in the mirror and feeling like my shoulders are too big, I’m like, no, my shoulders are big because I fucking climb.”

Making the Crossroads finals was particularly memorable for Hurlburt. “It was really cool getting to climb in front of a live audience,” she explains. “For me, it was the lighting that stood out. The dramatic lighting, the music, someone announcing your moves. It was really special.”

When she flashed Problem 2, however, she realized that she could win—and panicked. Back in isolation, Hurlburt apologized to her fellow competitors. They refused to accept her apology. “They said, ‘You’re going to try your hardest’,” she remembers. “They said they wanted to see these routes get sent.”

Can USA Climbing fight the USOPC’s orders?

“At this point, there’s no path toward challenging what the administration believes the Executive Order spells out,” says Norman. “What we’ve seen is that the administration is quite clear on what it wants. We’re chartered by the USOPC and the federal government, so we’re required to comply.”

The consequence for non-compliance? The immediate loss of High Performance funding and decertification as the national governing body for climbing. By the time any sort of legal challenge could gain headway, he predicts that the USOPC would essentially set up a new USA Climbing to oversee the sport and follow the ban.

However, it’s still possible that USOPC’s decision to ban trans women could be challenged in court. The Ted Stevens Act, a 1978 law that officially established the U.S. Olympic Committee, says that a sports organization is only eligible to be certified as a national governing body if it “does not have eligibility criteria … that are more restrictive than those of the appropriate international sports federation.”

In other words, since USA Climbing’s outright ban on trans women is more restrictive than the IFSC’s current trans participation policy, the ban might violate the Ted Stevens Act. According to the Associated Press, the Trump administration has anticipated this challenge and has already provided a free, detailed legal brief to the USOPC to help defend the ban in court. Such a case would only arise if and when a qualified trans female athlete is explicitly barred from an Olympic Games or world championship.

Trans athletes in climbing versus other sports

Before the USOPC’s ban on trans women, the International Olympic Committee published guidelines for international and national governing bodies on how to regulate transgender participation in sports.

One of these guidelines defines a “disproportionate advantage” as “one that is so large that no other athlete competing in a contest will have a reasonable chance of winning.” The IOC urged International Federations of Sport and National Olympic Committees to avoid placing any restrictions on athletes based on perceived disproportionate advantage simply because of their transgender status. Instead, they wrote, any restrictions should be based only on robust, peer-reviewed evidence.

USA Climbing—and, more accurately, the USOPC—is far from the first organization to disregard these guidelines. With the Trans Legislation Tracker marking anti-trans legislation at an all-time high, international governing bodies have increasingly been willing to ban first, then check the evidence later. For example, trans women have been banned from the women’s competitions in darts and chess, activities that don’t easily justify gender divisions in the first place.

Running, however, is one example of a sport that has a well-defined performance gap between male and female athletes. The average Olympic male runner runs 10.7% faster than the average Olympic female runner. Neither the 100-meter dash nor the marathon have a single female runner in the top 2,000 competitors. Furthermore, several sex-linked biological features explain this particular performance gap, including muscle mass and hemoglobin levels. This evidence for a sex-linked performance gap doesn’t imply that trans women should be banned from participating, but it does warrant a closer look at what fair competition looks like.

Climbing, however, lacks such a justification. In fact, compared to running, climbing’s gender performance gap barely exists. Only three men in the world (Adam Ondra, Seb Bouin, and Jakob Schubert) have redpointed a sport route with a higher grade (5.15c) than the top-redpointing woman (Brooke Raboutou) has. Only two men (Ondra and Alex Megos) have onsighted a route with a harder grade (5.14d) than the top-onsighting woman (Laura Rogora) has. The hardest boulder climbed by a man is V17; the hardest climbed by a woman (Katie Lamb) is V16. Several free climbing milestones, including the Nose free-in-a-day ascent and the crack climb Meltdown (5.14d), were established by a woman more than a decade before a man successfully repeated them.

Given that there are simply more male climbers than female climbers, it’s not surprising that men are ahead in the record books. In a 2016 Climbing survey of more than 3,000 female rock climbers, 78% said they believe that women will climb harder grades than men at some point. And one of the only peer-reviewed studies on climbing’s gender performance gap centers around why the gap is so small compared to other sports.

Socially, the climbing community seems to have accepted that women can be nearly as strong as the men. For example, two-time Olympic gold medalist Janja Garnbret and her coach have both speculated that Garnbret could possibly win the lead climbing events in the men’s category.

“I did try some of the men’s [lead] routes, and I did pretty well,” she told Magnus Midtbø in his recent video, “I Got Destroyed by the World’s Best Female Climber.” (She added, “But a comp is a comp, you know. Pressure and everything still plays a role.”) Garnbret’s coach also said that he thought she could win.

Their predictions alone don’t prove that Garnbret would succeed—we’d need a special livestream for that. Nor do they eliminate the fact that men hold most of the firsts. But they do highlight an important question: In a sport where men and women can challenge each other at the highest levels of climbing, is it possible to draw a line and say that a trans woman is “too strong” for the female category?

Privacy concerns with a “woman” test

One question USA Climbing has not yet answered is how their new rule can be implemented without violating athletes’ medical privacy.

Fiore, for one, believes that there is “no appropriate way” to figure out if a competitor is trans. “I know this term gets thrown around, but it turns into a witch hunt,” she says. “It turns into, ‘You don’t fit the idea of what I imagine a woman looks like, and therefore I’m going to accuse you. How do you prove that someone is or isn’t trans without deeply invasive medical records? This is why all women are harmed by these policies.”

In Hurlburt’s experience, competing as a trans woman has involved offering up her own medical records to strangers. At one local competition a couple years ago in New Mexico, the gym owner asked Hurlburt to provide testosterone results to comply with USA Climbing’s now-rescinded policy. As a pre-med student who works in labs, Hurlburt had the ability to order her own tests. “I agreed to comply just because it was easy,” she says. But later on, she ran into insurance issues because “insurance doesn’t want to cover more testing than necessary.” Her HRT plan only required testing once a year, but USA Climbing’s policy, at the time, required testing every six months. “That’s a significant financial burden because these tests can cost $200 out of pocket,” she says.

While Hurlburt was willing to provide medical records on request in the past, she is deeply concerned about the fact that USA Climbing isn’t HIPAA-compliant. Therefore, USA Climbing has no obligation to shield athletes’ medical information from law enforcement. Since, as she explains, “gender-affirming care is increasingly being criminalized,” submitting private information could put trans climbers at risk of harassment, arrest, and prosecution in some states, “especially if the organizers are less than supportive of the trans athlete’s eligibility to compete.”

USA Climbing doesn’t yet know how they will navigate athlete privacy with the new ban. Currently, the organization does not verify the chosen sex categories of any participants. Norman says that USA Climbing is still seeking guidance from the USOPC on whether additional documentation will be required for registration. All U.S. national governing bodies have been ordered to submit a new, more restrictive trans athlete participation policy to the USOPC, but Norman hopes that the USOPC offers a standardized one that national governing bodies can adopt. In response to concerns that the ban on trans women could turn into a witch hunt against any woman who doesn’t fit a mold, he tells Climbing that’s an “ongoing concern.”

“More than anything, we need additional guidance from the USOPC,” he emphasizes.

USA Climbing plans to release details of the trans female participation ban in October, before the start of the 2025 Youth Series.

What happens next?

Fiore, for one, wants to finish the more inclusive, nearly-complete trans participation policy instead of just abandoning it. “One of the things that I hope, expect, and believe that [USA Climbing] will do is finish out this policy … so that the moment this gets challenged by some court or judge, they have a good policy to put in place.”

Norman tells Climbing that he will leave that decision to the writing group. He also confirms that athletes who speak out against the ban will not face any corrective action from USA Climbing. “They can express their personal views,” says Norman. “Of course, we would hope that they would be aware enough to understand the nuance … We may correct if they’re misstating the facts, but they’re definitely free to share their personal opinions.”

While USA Climbing is unlikely to lift the ban unless the USOPC changes course, the new restriction does not apply to local competitions. Gym owners and coaches can continue working with trans female climbers in both recreational and elite programs. May, who has coached trans climbers in New York, says that people with institutional power need to step up. If she encountered a trans girl in the climbing gym, she would “do anything” to keep her in the program. “The social development and practice and team-building was 10 million times more important than competition,” she insists.

Hurlburt’s own story illustrates why May is right: community support matters. When Hurlburt was doing well in the Crossroads finals and feared being attacked for it, the other female competitors noticed her anxiety—and surrounded her with encouragement.

“The other girls in iso[lation] emotionally patched me up,” Hurlburt says. “Like, ‘No, you’re getting onto that damn stage. You’re going to do your best. We will accept nothing less of you.’ They put me back together. That was a really amazing moment.”

The post Why Did USA Climbing Just Ban Trans Women From All Events? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Op-ed: For today’s pro climbers, social media is part of the job. So why do we judge women so hard for it?

The post Stop Calling All Female Climbers “Influencers” appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

In 2019, four years before Eddie Bauer laid off their entire team of pro athletes, the brand wanted to add a female climber to their athlete roster. “One of their stipulations was that they had to have over 20,000 followers,” Katie Lambert, one of Eddie Bauer’s team members, told Climbing at the time. She suggested several climbers that she felt had potential, but there was one problem: her recommendations only had about 15,000 followers.

None of them got signed.

For better or worse, having a strong social media presence is nearly always a part of being a professional climber today. Sponsorship contracts frequently include stipulations on how often the athlete must post—and, when they do, which hashtags or branded accounts to add. Film budgets, which often comprise the majority of funding for expensive climbing trips, can also hinge on an athlete’s following and what social media deliverables they can produce.

Pro athletes have grumbled about this, but mostly accepted it. In an interview with EpicTV two years ago, Sasha DiGiulian summed up the sentiment that we find repeated by most pro climbers today: “Social media and athlete careers, unfortunately, are intermingled at this point.”

Male Athlete vs. Female Influencer

Despite this business reality of pro climbing, climbers still use the word “influencer” as an insult. I’ve heard “influencer” used in the abstract to imply someone who is unserious about their sport, only here for the likes and attention, and disrespectful of the craft. Hannah Morris, a climber who runs a successful YouTube channel about her climbing and training, commented on the trend last April in a video essay called “Is Social Media Ruining Rock Climbing?” “The word ‘influence’ carries a really negative connotation, and more so the word ‘influencer,’” she said, noting that she doesn’t consider herself a professional climber but still makes a living from videos. “It’s often said with a sense of embarrassment, a roll of the eye, or even a derogatory tone. I think that’s because influencers, viewed cynically, represent everything that’s wrong or backwards or kind of shitty about society.”

Conversely, “not an influencer” has become a compliment. Last year, in an Arc’teryx teaser for Ground Up, the documentary about Amity Warme’s free ascent of El Niño (5.13b/c; 2,500ft) on El Capitan, Alex Honnold praised Warme by calling her “the opposite of an Instagram influencer.” Although well-intended, the comment seemed deeply ironic coming from the most famous face in the climbing world, who makes much more money today from his presence than his performance. And, technically, it’s not even true. Warme posts frequently on social media to great success; her viral “Book of Hate” reel was viewed 50 million times on Instagram. Just like any athlete, she posts ads and plugs her brand deals. But what Honnold meant is that Warme is a serious climber. Her priority is performance, not visibility. His well-meaning language highlights an important stereotype: Women in climbing are often considered either serious athletes or influencers, but not both. This is the heart of the catch-22 that our sport has created for up-and-coming female climbers—or even established ones.

The word “influencer” has become a gendered slur. In the media, I see almost exclusively female climbers being called influencers. Last year, in a profile of DiGiulian and her new HBO documentary, Condé Nast Traveler called DiGiulian “as much an influencer as she is an athlete, with almost 500k followers on Instagram.” When the same publication profiled Jimmy Chin for the launch of his MasterClass, he was never referred to as an influencer, even though Chin has 3.4 million Instagram followers and counting to DiGiulian’s half a million.

Another example is Reel Rock’s promotion of Anna Hazelnutt and Tom Randall’s 2023 film, Queen Lines, about Hazelnutt making the first female ascent of The Walk of Life (E9 6c or 5.13c R) and sending The Quarryman (E8/5.13b). I still have a copy of Reel Rock’s email: “Instagram star Anna Hazelnutt is mentored by renowned Wide Boyz and Bridge Boys climber Tom Randall as she attempts her breakout climb, a precarious trad route in North Wales.” At the time, Hazelnutt had already climbed 5.14 sport, sent Once Upon a Time in the Southwest (E9 6a or 5.13b/c R), and was mere days away from sending Prinzip Hoffnung (E9/10 or 5.13d/5.14a), which she redpointed that month. For his part, Randall was—and still is—a successful YouTuber, with even more subscribers than Hazelnutt, as well as more followers on Instagram. Yet she was the Instagram star and he the prolific climber. (In response to the backlash, Reel Rock later changed the film description to call Hazelnutt an “up-and-coming tradster” instead of “Instagram star.”)

The trend extends into other mountain sports, too. When Caroline Gleich ran for U.S. Senate, Vox called her an influencer in their headline, even though she is a pro ski mountaineer and environmental advocate. Can you imagine Tommy Caldwell being called an influencer simply because he uses social media for his activism and brand obligations?

In my research for this op-ed, I couldn’t find a single instance of a male pro climber being referred to as an influencer in a magazine or a blog. Unfortunately, that matches my experience in real-life conversations. But where did this double standard come from?

Nasty origins

Before Instagram launched in 2010, pro climbing had different rules. “Magazines were the gatekeepers for the news,” wrote former Climbing editor Matt Samet in a GearJunkie article about Instagram and climbing. “If you weren’t a Big Name Sponsored Climber at a Big Name Area being photographed by a Big Name Photographer who had contacts at the magazines, it almost didn’t matter how compelling your story was. You weren’t getting any print.”

Throughout the 2010s, social media both democratized the industry—allowing everyone to self-publicize and build an audience outside of the magazines—and increased pressure on pro athletes to not just send hard, but create content.

In a 2021 interview with Climbing, Beth Rodden said that adjusting to the social media shift felt unnatural. “I’m really uncomfortable talking about my climbing achievements,” she said. For the past two decades, she’d learned, “If you did, then you’re going to get shit-talked at the cafeteria in Yosemite Lodge.” In DiGiulian’s movie, Here to Climb, Lynn Hill expressed the same sentiment, but recognized that DiGiulian was part of the “social media” generation that adapted quickly to new rules.

But one man, in particular, made “influencing” a gendered issue. In the most sexist and condescending article that I’ve ever read, which I honestly can’t believe is still alive on the Internet, former Rock and Ice editor Andrew Bisharat asks the question, “Athlete or Model: What Is Sierra Blair-Coyle?”

Blair, who has since dropped the -Coyle, is an Arizona-based former competition climber and member of the Team USA climbing roster from 2010 to 2018. She drew particular ire from Bisharat because of her success on social media. In his 2015 crash out over the fact that she was both sponsored and pretty, Bisharat ridiculed Blair’s use of “hieroglyphic” emojis and hashtags, repeatedly expressed bewilderment at the fact that she hosted a weekly Ask-Me-Anything on her blog, and lamented that she had “only” climbed two outdoor V9s—despite the fact that he knew she was focusing on indoor competition climbing at the time. (Blair has now sent multiple V12s.)

“[Blair] appears to be genetically devoid of any physical imperfections and incapable of writing anything provocative or negative,” he wrote. “In her photos … she is usually smiling and happy, wearing a cute outfit and doing something that vaguely resembles rock climbing.”

Can you imagine someone saying this about a male climber?

During one of her open Q&As, Bisharat asked Blair point-blank if she was an athlete or a model. She answered his question: “Both.” Most people would move on at that point. But Bisharat refused to accept her answer. Instead, he described her as a new subclass of athlete: an “Athlete Model.” I reached out to Bisharat to ask if he still believes this exists. He told me that “Athlete Model” was his placeholder word back then for what we now call “influencer.”

But back to his 2015 essay: He explained that “Athlete Models” are over-idolized—and they’re mostly female. “I can only think of one male Athlete Model in the climbing world,” he wrote. “If the goal is lucrative sponsorship, then it appears that there are now two ways to achieve this end: You can work hard to become one of the best athletes in the world at your sport, or you can generate a large social-media following by looking good. …”

To be fair, Bisharat did spot a trend: having a strong social media presence was, in 2015, becoming a serious advantage for up-and-coming pro athletes. For the first time, brands were prioritizing audience reach and storytelling skills in addition to ticking hard routes. It’s easy to imagine the Instagram-shy old guard resenting anyone able to adapt.

But where Bisharat goes wrong is by asserting that posing for product ads and being incredible at your sport are two separate paths—and implying that anyone attractive with a strong following must have chosen the former one. They’re not mutually exclusive. In fact, pro athletes have a much easier time making content than amateurs because they can often hire photographers with their brand support. It’s much easier, after all, to just focus on your climbing if someone else is in charge of making the content. More importantly, the deep sexism extant in Bisharat’s essay is that Blair’s attractiveness and upbeat personality imply a lack of ambition and focus. That stereotype, in particular, is something most female athletes have experienced. It’s time for our community to eliminate it.

Last year, on Honnold’s Climbing Gold podcast, Blair recounted how she didn’t just stumble into sponsorships; at eight years old, she went climbing for the first time and told her mom that she wanted to be a professional climber. She started reaching out to sponsors at age 10. After making finals at Junior Nationals when she was 14, she pursued competition performance with a relentless focus, using social media as a way to support her climbing.

She was 21 when Bisharat’s article came out. “It was awful for me,” she says on the podcast. “I was just being put into a conversation I didn’t walk into or have anything to do with. I got to be the one that got to deal with people saying I suck at climbing and I only have sponsors because I’m blonde and wear short shorts. It was really hard and made me feel like a lot of people didn’t like me and didn’t respect me. I felt like a joke every time I showed up somewhere. It was just a hellacious time for me personally.”

When I emailed Bisharat earlier this week, I asked him what minimum grade (on either the YDS or V-scale) Blair would have to send in order to earn his respect as a legitimate athlete instead of an “Athlete Model.” I also asked which pro climbers today were not “Athlete Models,” and whether he still held all the views espoused in his essay. Did he think he owed Blair an apology?

“I think everyone understands today that people can be really good at social media and really good at climbing, and that both paths are viable ways to achieve a ‘pro climber dream,’” Bisharat replied, declining to answer my questions. He explained that he was remarking more on a trend than on an individual person, despite the title of his piece.

Just call us “Athletes”

So why does it matter that female climbers get criticized more for using social media, and that they’re often called “influencers” instead of athletes?

In climbing, compensation is directly tied to one’s image. Companies have started to distinguish between their athlete teams and influencer teams in a clever attempt to get the best of both worlds: maintaining the exclusive nature for their athlete team, while benefitting from the video skills of talented content creators. In reality, however, this effectively functions as an A team and a B team, with corresponding tiers of pay.

A few years ago, I was offered an influencer position, but denied an athlete one, at a company that made products I liked and was using. “But I’m an athlete,” I told them, plainly confused. I was living out of my car, dedicating my life to climbing, and actively projecting my hardest route yet. My biggest life priority for the season was to send the proj. Work, sleep, social media, and everything else came after. Plus, I had already ticked harder routes than some of the brand’s sponsored “athletes.”

It didn’t matter; they had seen some of my climbing videos, where I’d cut together send footage with breezy or dramatic songs, and thought of me more as an influencer. I ended up taking the deal—free gear was free gear, after all, and it helped my climbing. While I didn’t think I automatically deserved top-tier sponsorship at the time, I still walked away with the concern that I was unintentionally starting to become known more for my climbing content than my accomplishments. Even if most of my videos were send footage, I considered not posting them and keeping my audience small until I was hitting higher grades. I’d send some serious testpieces in the fall, I told myself. Until then, I’d steer clear of any content that didn’t scream “professional athlete.”

Men don’t need to do this. And they certainly don’t need to worry about letting one or two non-climbing posts define them. Jordan Cannon, for one, can post bathtub selfies and pose in formal wear without fielding a horde of critical comments. Honnold can model nude for the ESPN Body Issue without anyone questioning his dedication to athletic performance. But when DiGiulian appears in an ad for a lingerie company, she gets accused of sexualizing her body in a way that only men, apparently, are allowed to do.

When we call female athletes “influencers,” we trap them in a catch-22: they need to build a strong audience to chase a professional athlete career, but in doing so, they’ll lose the respect of the old guard; if they minimize social media use and dodge the “influencer” allegations, they’ll also give up major opportunities to make a living from their climbing. In reality, this is just a perception issue. It’s completely possible to send hard and post engaging content at the same time. But unless we stop judging women for marketing their own careers, we’ll be holding them back from accessing the same kind of professional opportunities and compensation as men.

The simple takeaway? If you’re interacting with female climbers, just call them climbers or athletes. Athletes with a strong audience. Climbers that run successful YouTube channels. Athletes with big commercial partners. Up-and-coming climbers that are great at personal marketing. When you sit down with a female climber for a podcast, don’t dismiss her as an influencer in the description or name her episode after her blonde hair. Treat her as an athlete with an audience until proven otherwise—until she says otherwise.

If you’re going to call someone an influencer or social media star, stop and check what they call themselves—and verify that they actually care more about their content creation than their climbing performance. You’ll likely be wrong. That girl who just posted a cute selfie? She’s been grinding on her first 5.14 every weekend after work for three months. That woman who just released four hilarious gym videos to popular audios? She’s deep in a six-month training program to build up to her second V10. Regardless of whether she’s breaking world records or just starting out, it’s more likely that a woman is building an audience on social media to support her climbing dreams than vice versa. So call her an athlete and respect her goals—even if she posts about them on Instagram.

The post Stop Calling All Female Climbers “Influencers” appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

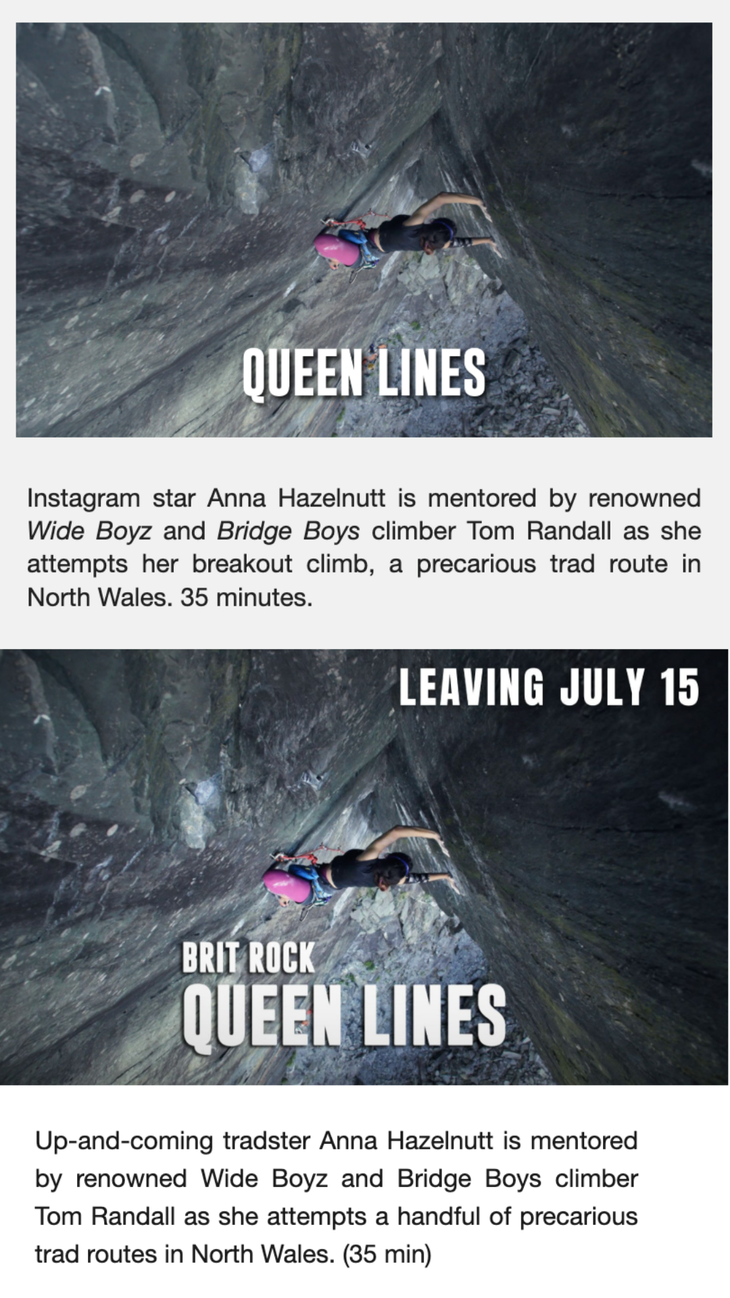

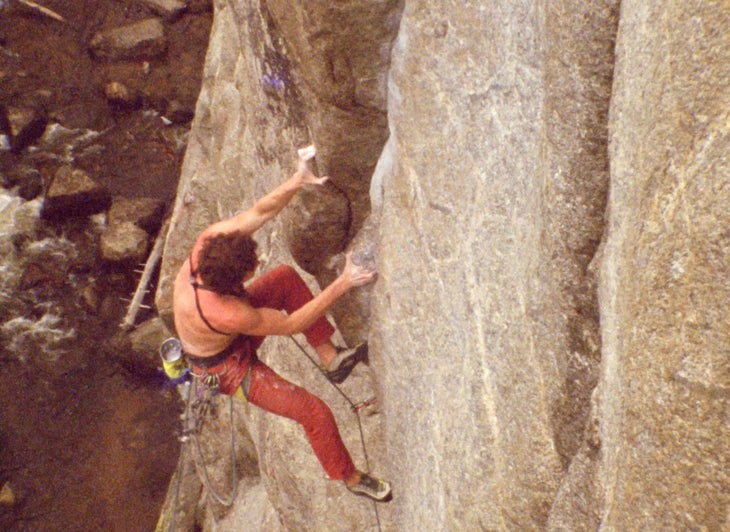

To prepare to flash 'Free Rider' in a day, Will Moss rope soloed ‘China Doll’ (5.14a R) in Boulder Canyon, Colorado on April 13, clipping only gear he placed on lead.

The post Will Moss Completes Hardest Trad Rope Solo of All Time appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Just one month before he became the first person to flash El Capitan in a day, 20-year-old Will Moss clipped his rope into a Grigri and pulled onto China Doll (5.14a R) in Boulder Canyon, Colorado. For any other climber, what happened next would be newsworthy in itself—and certainly not something to forget about for three months, until long past his Yosemite trip—but for Moss, at the time, it was simply training.

The young New Yorker was familiar with the route. In fact, he’d already sent the 140-foot testpiece back in February 2024, during his first year as a University of Colorado student. Between classes, Moss had spent his free time ticking some of the hardest routes in the area, including trad lines Cheating Reality (5.14 R/X), Kill Switch (5.14a), and Viceroy (5.14b R). The latter—a two-pitch extension to Crank It (5.14a)—famously left both Brad Gobright and Molly Mitchell with broken backs during their all-gear redpoint attempts. Despite the R and X ratings, Moss protected his ascents with only trad gear he placed himself, skipping all bolts and fixed gear. “I’m psyched to have done all these climbs only clipping gear I placed on lead,” he wrote last year on Instagram.

This winter, he felt stronger than ever, and he wanted to prove it. “I was preparing for the Free Rider flash and was trying to do as much hard and insecure granite as possible,” he tells Climbing. “[China Doll] has insecure laybacking with some pretty bad feet. I sent it five times total, sometimes on top rope solo, sometimes leading it. Eventually, I just wanted to see if I could push myself a little further and prove to myself mentally that I was a way better climber than I was last year.”

In his final few weeks before heading to Yosemite, Moss committed to a challenge: attempt to lead rope solo China Doll while maintaining his usual trad ethics. That meant skipping the route’s fixed piton and bolts. By self-belaying, carrying the weight of the rope, and manually controlling his own slack, he’d significantly increase the difficulty from his prior send. “More than anything, it just seemed like a cool, fun challenge to make this granite testpiece a little bit harder,” he says.

There was just one problem: He’d never lead rope soloed in his life.

Alone on the Wall

Lead rope soloing is a rare and advanced practice among free climbers, and sensibly so. It’s both physically harder and more dangerous than climbing with a belayer. Not only does the climber have to manage the rope and repeatedly let out slack for themselves before they can make a move, but they also must straight-up ignore a belay device’s manufacturer’s instructions. The Petzl Grigri, for example, is a widely recommended lead rope solo device, but Petzl insists that the Grigri is not designed or tested for self-belay.

With all the extra rope management required, lead rope soloing is most common among aid climbers, who can rest on their personal anchor systems clipped directly to protection to adjust the rope between moves. Lead rope soloing has only recently become more popular among free climbers as a redpointing technique, especially for harder routes. Brent Barghahn, who lead rope soloed The Parity Prow (5.14-) in 2023, estimates that only about six to eight people have rope soloed 5.14 in the past 20 years.

At least five of these climbers are well-known. One of the most prolific rope soloists today is Alexander Huber, who has established the first free ascents of alpine routes Nirwana (8c+/5.14c) in 2012, Mauerläufer (8b+/5.14a) in 2018, and Ramayana (8b+/5.14a) in 2021, all via lead rope soloing. Fabian Buhl has lead rope soloed the Wetterbockwand (8c/5.14b) and Ganesha (8c/5.14b). Keita Kurakami has lead rope soloed the Nose (5.14a), and Lukasz Dudek has lead rope soloed Pan Aroma (8c/5.14b). Notably, each of the aforementioned routes—even the Nose—are either fully or partially bolted.

A Quick Learner

Moss learned to lead rope solo by watching a video by Barghahn. On April 12, Moss headed out to Boulder Canyon with the idea of using the Wild Country Revo to self-belay. While rappelling a friend’s static fixed line, Moss decided to test the device by going hands-free on rappel, even though Barghahn hadn’t suggested that. Ideally, the Revo would catch him before he hit his backup knot.

It didn’t. When Moss removed his hands, the Revo instantly dropped to the backup knot—then broke entirely.

“It was honestly kind of a silly thing, letting go of the rope on a static line,” says Moss. “This broke the Revo. I saw the inside of the teeth were way below where they needed to be, so I didn’t get a lot of practice that day.”

This incident spooked Moss into returning the next day with a different setup: a Grigri+ and a Micro Traxion. His next big concern was that while he was climbing, the rope would “backfeed,” sliding through his belay device back through his gear and resulting in a dangerous amount of slack in the system. If he fell, he’d have too much slack out to catch him before he hit the ground.

Barghahn, who runs the gear company Avant Climbing Innovations, gave Moss a few of his Anti-Backfeed Keepers: plastic clips that attach to a gear carabiner and cinch down the rope like a finger. “Those were really helpful,” says Moss. Still, it didn’t eliminate all of the risk of getting stuck mid-pitch. “If you feed too much slack, you’ll have a really heavy brake strand, so the Grigri will lock up on you,” Moss explains. “If you have too little slack on the micro, you’ll have to feed out more during the middle of the crux. That’s definitely the biggest thing I had to think about leading the climb.”

Go Time

According to Moss, China Doll’s R rating comes from the fact that there’s no good gear until 30 or 40 feet off the ground until the route’s first boulder problem, protected by a 0.1 cam. “If the 0.1 rips, you’re going to fall onto the slab,” Moss says, “Up higher, it’s protected by a ball nut and some really small nuts.”

With some friends nearby in case anything went wrong, Moss took two practice laps on China Doll, clipping bolts and taking purposeful falls to test his lead rope solo system. Finally, he went for his first attempt at the gear-only rope solo—and sent.

The climb felt a lot harder than it had with a belayer. “I had sent it five times that season with pretty minimal problems, sometimes just doing it as my first route of the day,” he says, “but the time I sent it lead rope solo, there were definitely some times when the Grigri locked up on me and I had to deal with that.”

In addition to physical challenges, he felt constantly alert: “Thinking about more things at once—you’re clipping this gear, thinking about the crux, and thinking about how much rope you’re feeding through the micro. Lead rope soloing 5.11 would have been cruxier than climbing China Doll with a belayer.”

Three months later, Moss sees his lead rope solo of China Doll as preparation for future projects. “A big motivation for this was to get that style down so I could take it to bigger walls,” he says. “It seems really cool to be completely self-reliant on a big wall, in my eyes, even though I haven’t really done much of it.”

This fall, he plans to take a semester off from college so he can maximize his time in Yosemite.

Watch Will Moss on China Doll below:

The post Will Moss Completes Hardest Trad Rope Solo of All Time appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Hayden Jamieson’s new movie, "For the Love," documents his emotional return to ‘Picaflor’ (5.13+; 3,000 ft) in Chile’s Cochamó Valley with Jacob Cook and Will Sharp.

The post He Spent Years Preparing for a 3,000-Foot Dream Climb. Then, One Broken Hold Nearly Undid It All. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

This year’s feature film premiering at the International Climbers’ Festival is For the Love, a 23-minute documentary about Hayden Jamieson, Will Sharp, and Jacob Cook’s first free ascent of Picaflor (5.13+; 3,000 ft) on Cerro Capicua in Cochamó Valley, Chile.

The film centers Jamieson, who calls Picaflor a “guiding light” back from his traumatic 2016 mountain rescue in the Karakorum. It ultimately took Jamieson two expeditions. He first set out to send all 24 pitches in 2022 with Bronwyn Hodgins, Tyler Karow, and Danford Jooste. After Karow left early, Jamieson, Hodgins, and Jooste sent all but one slab move. In 2024, Jamieson returned to Chile with Cook and Sharp to rehearse and send the route.

We caught up with Jamieson to discuss why he didn’t want to be the main character of the movie, how exactly he got past the slabby crux that shut him down in 2022, and what exactly that white stuff that he painted on his fingers was.

The following interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

Climbing: After you returned from Picaflor, how involved were you in making the film? Did you have a certain vision of what needed to be included in the story?

Jamieson: I was pretty involved. Ian [Dzilenski] is a really good friend of mine … during the time when he was coming up with the initial cuts of [the film], he and I were collaborating a lot. We would have these super long sessions. I don’t know the first thing about editing, but I would go to his house and hang out in the editing room and go through all the footage. We’d talk about what we liked and didn’t like and what music paired well with what and what scenes we wanted to show and how we wanted to organize all of the footage.

Fortunately and unfortunately, it got to a point where neither of us felt like it was going in the direction we wanted, but also, neither of us was willing to say that because we knew we had to come up with some sort of product. People had paid for this trip and given us funding.