A Climber We Lost: Chris Jones

Each January we post a farewell tribute to those members of our community lost in the year just past. Some of the people you may have heard of, some not. All are part of our community.

Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

You can read the full tribute to Climbers We Lost in 2024 here.

Chris Jones, 84, September 17

Christopher Alan Giesen Jones, one of the most accomplished alpinists of the 1960s and 1970s, died on September 17, 2024, at age 84. He is best known for establishing some of the most difficult and intimidating alpine routes in the world, such as on the North Face of North Twin, Alberta, which has still never been repeated, and for authoring the history book Climbing in North America. His climbing partners included Warren Harding, Royal Robbins, Yvon Chouinard, Doug Tompkins, and George Lowe, among many others.

Chris was born in Dorking, Surrey, on November 24, 1939. He studied at Marlborough College and earned a degree in engineering from King’s College London. Throughout the 1950s and ‘60s, Chris climbed extensively in England, Wales, and the Alps, where he spent five seasons progressing through routes such as the Walker Spur (ED1 6a/5.10-) on the Grandes Jorasses, in Chamonix. He also made an ascent of the Bonatti Pillar (5a/5.7 A1) on Les Drus, which was one of the most famous routes in the Alps until a 2005 rockfall destroyed it. Chris partnered with Americans for some of these alpine missions, including John Harlin and Royal Robbins, and he became inspired by their descriptions of unclimbed walls in the U.S.

In 1965, Chris’s employer, IBM, offered him the chance to work in their California office. He accepted, moved to the U.S., and promptly resigned to focus on climbing. “I was kind of straightlaced,” he remarked in a TV interview. “They weren’t anticipating me just quitting.”

Chris first moved to Truckee, California, where he worked on various surveying projects with Warren Harding and climbed in his free time. “I filtered down to [the] absolute bottom of the socioeconomic heap,” he said. “It was only in ‘67 that I decided I had to get a grip here. I quit my [surveying] job and moved to the Valley.”

When he finally got to Yosemite, Chris built a close network of friends in Camp 4 and climbed eight Grade V or VI routes in his first spring season. His team was one of the first to attempt the first ascent of the Dawn Wall, but they retreated because they believed the route would require too many bolts. Chris made the eighth ascent of the Salathé Wall. When he wasn’t in Yosemite, he started exploring the Canadian Rockies, where he would later establish first ascents on several north faces of classic peaks.

In 1968, Chris traveled to South America to attempt several major expeditions. First, he made the first ascent of the East Face of Yerupaja (6,635m) in Peru. Then he went down to Patagonia to join his friends Yvon Chouinard, Doug Tompkins, and Dick Dorworth on their attempt to summit Fitz Roy. The crew called themselves the Funhogs, and they had a plan: Yvon, Doug, and Dick would drive from California to South America in a van, then pick up Chris on the way. Without cell phones or GPS, however, Chris nearly missed his meet-up point.

“When I realized I wasn’t going to make it and that I was going to miss my friends in Chile,” Chris said, “I said to myself, if they think they’re going to climb Fitz Roy without me, they’ve got another thought coming. There’s only one road from the north across the Patagonian desert that takes you to Fitz Roy, so I decided to hitch a lift to a point I knew they’d have to pass. I was prepared to sit there all week, if necessary, waiting for them.”

That two-month-long expedition was a lasting example of toughness and commitment. The four team members and their filmmaker hiked 80-pound loads through deep snow to establish a base camp. By the time they had set up Camp 2, an enormous storm had descended over them. For the next three weeks, the crew huddled in a makeshift ice cave, only stepping outside to scout the weather and racing back into the cave to report 100mph winds. Even after the team ran out of food and was forced to rappel through the storm, they refused to give up, waiting a full month before seizing another weather window and establishing the California Route (40° snow 6a+/5.10; 800m). Their adventures are chronicled in the movie Mountain of Storms (1968) and the book Climbing Fitz Roy, 1968: Reflections on the Lost Photos of the Third Ascent (2013).

Throughout the 1970s, Chris partnered with American climber George Lowe to establish a handful of groundbreaking ascents in the Canadian Rockies, including on the north faces of Mount Columbia, Mount Alberta, Mount Deltaform, Mount Kitchener, and Mount Geikie.

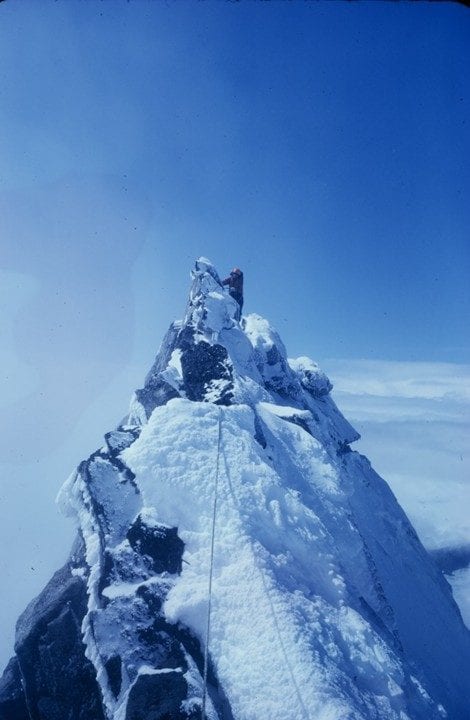

Finally, in 1954, Chris and George put up one of their most legendary ascents: the North Face of North Twin (VI 5.10 A3; 1,500m). Grey Satterfield’s story for the American Alpine Club noted that the North Face was “taller than El Cap” and “steeper than the Eiger.” In a seven-day expedition, Chris and his partner, George Lowe, suffered through extreme rain, snow, and hail and bivied in wet sleeping bags without portaledges.

“I feel grateful to be with Chris,” George wrote in his 1975 report for the American Alpine Journal. “He probably can’t lead [hard rock] or extreme ice, but somehow he gets up things, something far more important to me than the ability to climb a tough crack in Yosemite.”

After one particularly harrowing day on North Twin, Chris and George stayed up until 3 a.m. to discuss their options for the morning: continue up a likely unclimbable rock pitch, rappel 50 meters into an ice runnel with only six pitons and three ice screws, or call for rescue and potentially starve while waiting. They chose the ice runnel.

“The basic toughness in [Chris] that is so critical in a climbing companion comes out,” wrote George. “We will keep going until we are absolutely stopped.”

By the time they had summited and hiked back to civilization, Chris and George had totally exhausted their food supply, but they’d secured a legacy. Their route on the North Face of North Twin has never seen a full repeat. In 2002, Barry Blanchard wrote in the American Alpine Journal that their route “was the hardest alpine route in the world. I believe that nothing then accomplished in Patagonia, the Alps, Alaska, or the Himalaya measured up to what George and Chris accomplished with ‘a rope, a rack, and two packs.’”

While recovering from a ski accident, Chris began writing a book to chronicle the development of climbing in North America. He felt that the existing history, particularly in the U.S. and Canada, was incomplete.

“To gaze up at a crag was exciting,” he wrote, “but to know something of those who had been before added another dimension…The mountains are not just masses of rock and ice. They are places where people have struggled, laughed, dreamed, and sometimes died.” Chris published Climbing in North America in 1976.

In 1977, the American Alpine Club selected Chris, George, and four other American mountaineers as part of the Soviet-American Mountaineering Exchange. Along with his team, Chris made the first ascent of a new ice route on the North Face of Mirali in Tajikistan and climbed the central route of the North Face of Free Korea Peak in Kyrgyzstan.

Four years later, in 1981, Chris traveled to the roof of the world to perform some of the most technical climbing that had been attempted yet on Mount Everest. He and his team established a direct route up the Kangshung Face by ascending a 3,500-foot buttress of rock and ice that led to a snow field. Unfortunately, Chris’s team was forced to descend from there due to avalanche risk. However, George Lowe later returned to continue the route and summit Mount Everest via the Kangshung Face in 1983.

Chris continued to climb internationally for many years, eventually settling in Santa Rosa, California, with his wife, Sharon Ponsford-Jones. He and Sharon also shared a house in the south of France. He deeply appreciated art and books, and he and his wife frequently went to live classical music events, including the San Francisco Opera and the Santa Rosa Symphony. When he was not traveling, Chris enjoyed several outdoor activities including cycling, hiking, and birding. He is survived by his wife of 44 years and his two stepchildren.

You can read the full tribute to Climbers We Lost in 2024 here.