The iconic alpine climbing area remains closed until further notice.

The post Updated: 60 Climbers & Hikers Heli-Evacuated From Bugaboos Due to Flooding appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

It was a little after 8:00 a.m. on Sunday, August 17, when Jordy Shepherd’s phone buzzed to life. He and other members of Columbia Valley’s Search and Rescue team were being sent into the towering granite spires of B.C.’s Purcell mountains to respond to “a report of dramatically elevated creek flows” in Bugaboo Provincial Park.

The rescuers boarded a helicopter a short while later and flew in. Shepherd, a mountain guide certified by the Association of Canadian Mountain Guides (ACMG), who has spent the past 25 years working in the Bugaboos, could tell something was wrong through the helicopter’s windshield.

“On our first reconnaissance flight of the area we noted very high creek levels above the Kain Hut, and dirty water,” he said. “The hiking trail access bridge was intact but surrounded by raging water on both sides.” Upstream from the hut, Shepherd noticed that the meltwater lake between Bugaboo Spire and Crescent Spire, which had historically been supported by glacial ice on its downhill side, now “cut a deep channel through the glacier ice” and rushed into the valley below.

BC Parks believes the flooding was due to a mixture of rain and melt. “This weekend’s flooding incident appears to have been caused by rainfall increasing lake water levels until it overran an ice dam, and the rapid melting of the dam by lake water flowing over it,” said Nigel McInnis, communications manager with BC’s Ministry of Environment and Parks.

Watch an aerial video of the flood damage to the Bugaboos

Guests staying at the Alpine Club of Canada’s (ACC) Conrad Kain Hut were among the first to notice the rising creek level on the steep moraine above them. The hut’s custodian immediately contacted SAR. According to the ACC’s Executive Director, Carine Salvy, the hut was fully booked, with more than 30 people staying there. Nearby campgrounds filled with climbers were similarly busy, bringing the total number of people in the backcountry to more than 60.

Shepherd, who has more than two decades of mountain rescue experience and hosts a podcast called Delivering Adventure that focuses on backcountry recreation and safety, surveyed the damage from the air. After taking stock of the submerged trail, he and his team determined it would be safest to evacuate the public by air.

“It took about 10 flights to evacuate 60-plus people plus their gear,” Shepherd explained. A group of ACMG guides already working in the Bugaboos, along with two ACC staff and a police officer, helped Shepherd and his 10-person SAR team with the process. They used a nearby Canadian Mountain Holidays lodge to refuel the helicopter during the seven-hour evacuation. “Everyone was in good spirits, but sad to have to leave the Bugaboos,” Shepherd said.

This isn’t the first time that shifting rock and ice has impacted access to the Bugaboos.

In December 2022 rockfall destroyed part of Snowpatch Spire. Among the climbs wiped off the granite was the Tom Egan Memorial Route, a fourteen-pitch 5.14 considered to be the hardest alpine climb in Canada. Lingering risk from the rockfall kept parts of the park closed until earlier this summer.

Melting glaciers are also a well known problem in the area. According to a 2009 summary of changes to glaciers in mountains of western North America, the Bugaboo Glacier has lost more than 400 meters of ice since 1972. Just north of Bugaboo Spire, the Vowell Glacier is retreating even faster. In 2017 a meltwater lake at the toe of the Vowell broke through the ice and rock holding it back. There wasn’t anyone in the remote drainage below, but BC Parks still warns backcountry users to “avoid extended travel or overnight camping” in that part of Bugaboo Provincial Park due to the risk of another flood.

BC Parks issued a formal order shutting down access to the core area of Bugaboo Provincial Park the afternoon of the evacuations. For climbers hoping to get into the Bugaboos this season, there isn’t any clear timelines for re-opening. “Until flooding subsides and Parks staff are able to assess residual hazards and damage done to facilities, the entire Core Area of Bugaboo Park including the Kain Hut Trail is closed until further notice,” said Nigel McInnis.

Carine Salvy and the ACC don’t believe there is any direct damage to the Kain Hut. The biggest challenge, they agree, will be damage to the trail. “The trail leading to the hut is heavily impacted and cannot be used to access the hut or the campgrounds,” said Salvy. “We are working with BC Parks to determine whether an alternate route can be established. We hope to have more information later this week.”

August 26, 2025: While B.C. Parks has yet to announce a reopening date for the trail, a group of five climbers and hikers were charged for trespassing last week. The group hiked into the range despite the closure and were charged under B.C.’s Park Act. Writes the Conservation Service’s Facebook post: “On Wednesday, the [Conservation Officer Service], in collaboration with B.C. Parks and the RCMP, flew into the closed area via helicopter after reports of several individuals refusing to leave. All five people –from Ontario and BC–were charged under the Park Act and issued eviction notices to immediately depart, which they did.”

The post Updated: 60 Climbers & Hikers Heli-Evacuated From Bugaboos Due to Flooding appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

“Flying at night, the margin for error is extremely low,” Search and Rescue said. “It’s like staring through two paper towel tubes.”

The post Climbers Rescued By Helicopter After Spending the Night Stranded and Injured appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Peering through night vision goggles, John Blown of North Shore Rescue (NSR) could make out a pair of headlamps on Yak Peak, a granite dome three hours drive east of Squamish.

Blown’s team had mobilized at 10:40 p.m. on August 5 to assist with a complex climbing rescue on the peak’s Yak Chek (5.9/10a; 450m). Earlier that day, at roughly 6 p.m., two Australian climbers were nearing the top of the route when the leader fell down a runout slab pitch and injured his head. When his partner lowered him back to the belay station, he noticed his friend was dazed and his helmet was dented.

According to Barry Ganon, the Search Manager with Hope Search and Rescue, the climbers only called for help nearly four hours later. Clouds darkened the sky and the setting sun was dipping below the horizon, the mountain soon to be shrouded in darkness. Ganon requested assistance from NSR, who, along with their rescue partner Talon Helicopters, are the only volunteer SAR team in southwestern B.C. with the equipment and certification to perform helicopter rescues at night.

Poor weather and cloud cover forced NSR to approach Yak Peak from the east and north—instead of directly from the west. Waves of cloud and rain rolled steadily through the pass, further obscuring any sight of the climbers in the night. “Flying at night, the margin for error is extremely low,” Blown explained. “Night vision is like staring through two paper towel tubes, you can’t see clouds coming and it’s hard to see the rain.” Although Blown’s team eventually caught brief glimpses of the climbers, they eventually backed off due to the challenging conditions.

The successful rescue

Nathan Friesen, a member of nearby Chilliwack’s Search and Rescue team, received a message to prepare for a ground rescue effort instead. Friesen and his colleagues packed up their gear in the middle of the night and drove an hour east to the base of Yak Peak. In the dark, they shouldered packs and started hiking up the mountain’s scramble route, making visual and verbal contact with the climbers in the early morning hours.

“[Yak Chek] is a pretty common spot for us to get called in for rescues,” Friesen explained. “With its short approach and moderate grade, a lot of people underestimate this route.”

Dave Ellison, an Association of Canadian Mountain Guides-certified rock climbing guide agreed. “Yak has far more loose rock and is more runout than your typical objective in Squamish or the Fraser Valley,” he said. “The rock is much crumblier and less predictable compared to the bomber granite we have at most of our popular climbing destinations locally. The route finding is also far more complex and it’s easier to get off route.”

Lucky for these climbers, the weather forecast improved overnight and NSR put another helicopter in the air that morning. Friesen and the Chilliwack team were prepared for a ground rescue, but, with wet rock and the nature of the injuries, Blown explained that a helicopter rescue was the best option. The NSR helicopter deposited two rescuers to the belay station where they packaged the injured climber and flew him to a waiting ambulance below. The second climber was flown off shortly after. Both were transported by paramedics to a local hospital where they were later released with minor injuries.

Gannon explained that the weather and late-day timing made the rescue was both complex and challenging. He wasn’t sure why there was such a long delay between the accident and the call for help, but explained that, even after the call, the rescue was further delayed by communication challenges with the subjects—despite the fact that there is cell reception on the mountain. (For reasons that still remain unclear, when rescuers attempted to call the Australian phone number associated with the climbers’ Personal Locator Beacon, they couldn’t make contact. It was only after rescuers spoke with one of the climbers’ mother in Australia that contact was made through WhatsApp and rescuers were able to talk to the climbers on the wall.)

View this post on Instagram

Blown pointed out a few things that the climbers did right—carrying rain jackets, headlamps, and having a device to call for help—but he also noted one key way to be better prepared for a committing route like Yak Chek. “They didn’t really have an exit strategy in case something went wrong,” he said. “They couldn’t rappel. … The pitches are 60 meters long and they only brought a single 60-meter rope.” While it may have been possible for the climbers to rappel off anchors built from their own gear, they decided not to attempt it due to the worsening weather and the head injury. Carrying a second rope to aid in a retreat would have vastly simplified a descent.

Everyone Climbing spoke to for this story reiterated that climbers should respect the alpine nature of this area. “Alpine objectives are often more runout, have more loose rock, are dirtier, and more sandbagged than local climbs,” Ellison said. “If you over prepare for alpine objectives or target routes well below your normal grade, you are going to have a much better time.”

The post Climbers Rescued By Helicopter After Spending the Night Stranded and Injured appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Most PNW climbers beeline to Squamish on weekends. But quiet options (with impeccable stone) exist nearby

The post Skip the Weekend Crowds in Squamish. Try This Nearby Bouldering Paradise Instead. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Like many people who come to southwestern British Columbia, Denis Langlois wanted to climb in Squamish. It didn’t matter that, when he moved from Montreal to Canada’s westernmost province, he landed in the rural farming community of Agassiz, nearly two hundred miles from Squamish’s towering granite walls. On weekends, Langlois would load up his car and wait in stop-and-go city traffic for hours, making regular pilgrimages to Canada’s climbing mecca. Until he discovered the Fraser Canyon.

Located a short distance northeast of Langlois’s home, the Fraser Canyon is a deep chasm stretching from Lillooet to Hope, BC. Carved by one of western Canada’s most iconic rivers, the canyon starts on the dry, sagebrush interior plateau and ends in temperate coastal rainforest. It’s a region steeped in history, from Indigenous peoples to the fur trade, gold rush to the birth of Canada as a nation.

Driving through the Fraser Canyon feels like going back in time. Heading north from Hope—where Rambo: First Blood was famously shot—the road is lined with old motels, shuttered restaurants, and tourist attractions from a bygone era. But off the road, on the banks of the mighty Fraser, Langlois and a group of friends unearthed a new bouldering paradise.

The first boulder

A mind-numbing work commute can be thanked for Langlois’s curiosity about the canyon. He frequently drove two and a half hours from his home in Agassiz to dairy farms up the canyon, helping farmers use new technology on their land. As he drove, his eyes wandered from the blacktop pavement towards the forests and shoreline. He caught glimpses of boulders protruding from sandy beaches and mossy cliffs hidden in thick vegetation.

A few days before Christmas 2020, Langlois was headed home from a family sightseeing trip when his curiosity boiled over. He pulled off the highway, thanked his wife for staying with the kids, hopped over a concrete barrier, and bushwhacked to the base of a house-sized boulder. He found one side with a clean 45-degree wall that looked like a natural Kilter Board. Unfortunately, it lacked the Kilter Board’s jugs, so he contoured around the massive boulder and discovered a cave with holds on the other side. This one boulder convinced him of the area’s potential. He returned several times that January and February, despite heavy coastal rain, to start building a trail. By the end of February the Fraser Canyon’s monsoon season began to taper, and he finally got to climb on the giant highway-side boulder. Langlois told a few friends about what he was up to. Most of them gave a polite, absent smile—likely thinking of their project in Squamish—and then gently declined his invitations to drive up the canyon. Eventually, his persistence paid off when he convinced a few local buddies to come out for a day.

Gold Beach

By the end of that first summer, Langlois’s small crew was clearing trails, scrubbing moss, and establishing problems from beginner friendly V1s to stout V10s. One hot day, one developer walked down to the river’s edge and noticed the water level was way down, exposing a cluster of semi-truck-sized boulders nestled on a white beach of soft, fine-grained sand. They named the area Gold Beach and spent the rest of the day establishing instant classics including Beauty and the Beach (V6), an airy prow that ascends one of the massive boulders deposited by the mighty Fraser. “We were like kids in the sandbox,” Langlois recalled.

The potential for climbing in the Fraser Canyon seemed nearly endless to Langlois. But if he was going to keep climbing and developing, he wanted to make sure it was happening in the right way. “Early on I did a property search to try and find out if [the boulders] were on private or crown land. That’s when I found out it’s all native land,” said Langlois. Specifically, the boulders were on the lands of the Spuzzum and Yale First Nations. Neither nation had a public contact for land management, so Langlois eventually showed up at the band office to ask for permission to climb in the area. He met with the chiefs of the two nations who were happy to see climbers enjoying their land. “[They] said, if you’re cleaning the boulders and taking the moss off, just put some tobacco down and say thanks to the land for giving you the ability to play there,” Langlois explained.

A push for outdoor recreation

In May 2023, the Spuzzum Nation submitted a proposal to build a new all-season mountain resort in a sub-range of the North Cascades above the Fraser Canyon. According to the Nation’s proposal, the South Anderson Resort would serve 9,000 skiers a day in the winter and provide a range of summer recreational activities, including climbing.

The Spuzzum Nation’s proposal says the resort will bring in visitors, create jobs, and support “recreation opportunities in the Cascade Mountains in an environmentally sustainable and responsible manner.” This plan is one piece of a larger strategy using outdoor recreation to revive the Fraser Canyon’s struggling tourist economy.

Up until the 1980s, the Fraser Canyon was the only major highway connecting southwestern British Columbia to the rest of Canada. The canyon hosted a booming tourist economy with travelers frequenting restaurants, motels, and other tourist traps up and down the canyon. But in 1986, BC opened the Coquihalla Highway, a more direct route that shaved hours off the drive. A story in Canadian Biker compared the Fraser Canyon to America’s Route 66 after the construction of the Interstate Highway system, noting scenes of “abandoned motels…hotels, and gas stations surrounded by tumbleweeds and sporting rusted signs—the stuff of broken dreams and economic ruin.”

Locals hope that outdoor recreation can revitalize the region and fuel a new, sustainable economy. According to a 2019 study published by the Fraser Valley Regional District, outdoor recreation contributes $1.52 billion annually to the broader regional economy, supporting 10,262 jobs. Unfortunately for the Fraser Canyon, most of that economic impact is happening closer to the more popular, outdoorsy towns of Hope and Chilliwack. “While outdoor recreation is growing, the development has been slower in the Fraser Canyon,” Sam Waddington, owner of the local gear shop Mt. Waddington Outdoors, explained. “To any of us who spend time in that corridor, it’s hard to understand why, because it is spectacularly beautiful.”

Sharing the canyon

Initially, Langlois was hesitant about promoting his work in the Fraser Canyon. He was all too familiar with the crowded crags, lineups at boulders, and the trash and trampled vegetation that followed the climbing crowds in Squamish. He also recognized that without more climbers, all his work developing and maintaining could be for naught. “Route developers put in a ton of effort to clean, bolt, and set up an area—only to see it reclaimed by the forest when it wasn’t used enough,” explained Waddington, also a founding member of the Fraser Valley Climbing Society.

It was a familiar experience to Langlois who, during his first trip to the local Harrison Bluffs, spent the day “bushwhacking around alder and blackberry bushes” just to get to some of the area’s most popular routes. Not wanting to see his own hard work go to waste, Langlois eventually decided to upload beta about the area to Mountain Project and Kaya. He also enlisted Jesse Wheeler to help make a film about the area. The result was a 30-minute doc called Gold Rush, which features Langlois and the rest of the developers bouldering on the canyon’s premium granite blocks, as well as the area’s roots with Indigenous singing, drumming, and dance.

A new Squamish?

So far, Langlois hasn’t seen a horde of new climbers descend on the Fraser Canyon. Even with everything it has to offer, he still sees most climbers, including a lot of Fraser Valley locals, head to Squamish. This traffic is something that Sam Waddington, who operates gear shops in both the Fraser Valley and Sea to Sky region—the area north of Vancouver that stretches from Squamish to beyond Whistler—thinks could be about to change. “In Squamish, they’re building new crags to try and spread out the crowds, while here, developers are trying to entice people to come climb out here,” he explained. “I think the bouldering, especially around Hope and the Fraser Canyon, has the potential to be some of the best anywhere.”

Waddington is also quick to point out that the Fraser Valley is already home to some iconic climbing. The Northeast Buttress of Slesse Peak, an iconic fang of rock in the Chilliwack River Valley, is written up in the Fifty Classic Climbs of North America. The late Marc-André Leclerc, whose image hangs behind the till at Waddington’s Chilliwack shop, grew up in Agassiz and established and soloed all types of ambitious routes in the region. The Chinese Puzzle Wall, which both he and Brette Harrington put up an impressive first ascent on, is just one valley over from Slesse.

But the Fraser Valley is still far from being a true competitor to Squamish’s bouldering scene. The Fraser Valley Climbing Guide (2023) comes in at just over 100 pages—roughly a quarter of the size of either Squamish Select or Squamish Bouldering. Waddington argues this low number simply means the Fraser Valley has plenty of new-routing potential. Given the high cost of living in Squamish and crowding at popular climbs, he thinks that people are already looking for other places to explore. “We have the climbing society, we have a local gym getting more people climbing, we have a local guidebook, and we have folks like Denis finding these cool new areas,” he said. “I’m feeling stoked about the future.”

How to climb in the Fraser Valley and Fraser Canyon

Where to fly

- Fly into the region directly to Abbotsford airport, or into Vancouver. Driving from Vancouver to the Fraser Valley take between one-and-a-half to three hours depending on where you’re headed.

Where to stay

- Hope and Chilliwack offer the closest accommodation to the climbing areas, from hotels to private and provincial park campgrounds Check out BC Parks and Recreation Sites and Trails BC for all options.

Climbing beta

- Beta for the entire region can be found in the Fraser Valley Climbing Guide, available online or at shops like Mt. Waddington Outdoors in Chilliwack and Valhalla Pure in Abbotsford. Online beta can be found on Mountain Project and, for the 82 listed problems in the Fraser Canyon, on Kaya.

Rainy day activities

- Project Climbing has two gyms in the area, one in Abbotsford and a bouldering gym along the Chilliwack River.

- Land Cafe and Studio next door to the Chilliwack gym has great coffee and rest-day yoga.

Tread lightly

Make sure to practice Leave No Trace ethics at all climbing areas in the region, especially regarding human waste. Some areas in the Fraser Canyon are located near traditional fishing areas and other important cultural places. Respect the Indigenous nations whose land these climbs are established on. You can donate to the Fraser Valley Climbing Society to help with local stewardship and development projects.

The post Skip the Weekend Crowds in Squamish. Try This Nearby Bouldering Paradise Instead. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

I went to Alaska with plans to spend five weeks in the Arctic. My friend Malcolm and I had designs on kayaking from a small village on the northern shores of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to a remote bay where we would head out overland to scramble up mountains, explore valleys, and search for … Continued

The post Choss and Rain: Climbing (and Failing) in Alaska appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

I went to Alaska with plans to spend five weeks in the Arctic. My friend Malcolm and I had designs on kayaking from a small village on the northern shores of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to a remote bay where we would head out overland to scramble up mountains, explore valleys, and search for the tens of thousands of caribou who migrate through the region every summer. But, like all good plans, it all fell apart pretty quickly.

Our kayak route was clogged with miles and miles of sea ice, an endless white horizon, the last thing you want to see when you’re planning is to set out in a thin skinned, folding kayak.

After two weeks exploring as far as our feet would take us over the tundra and waiting for the ice to melt, we threw in the towel. We had been defeated by the ice. So, we did the only rationale thing I could think of. We went climbing.

The problem was, everything I knew about climbing in Alaska started with a chartered bush plane flight. Having emptied most of my bank account getting to and from the Arctic, there was no way I could afford that. But, I reasoned, Alaska is a state larger than Texas, covered largely by rocks and mountains. There had to be some climbing that didn’t require a plane. Right?

I fired up Mountain Project and poured over the entries for Alaska. I was right, Alaska was home to dozens of climbing areas, everything from near roadside bouldering to bolted routes and alpine trad. I smiled, un-interested in the warnings of unstable weather, swarming mosquitos and ornery grizzlies that seemed to mark every area description.

Flipping through the options, I was entranced by a place called Resurrection Bay where “route development potential” lay on seaside walls under which whales, bears and moose frequently frolicked. There were warnings that “there are reasons why climbers have avoided this area: RAIN RAIN RAIN, multi-day challenging access, expensive. Make sure you have loads of time, money, and optimism to succeed here,” but we seemed to be on the edge of a rare window of hot, dry weather. That, and we were pretty good at ignoring other peoples’ advice, no matter how wise.

We set out for the town of Seward, where we planned to launch our kayak to paddle out in search of first ascents. Enroute, we stopped for a warm-up on the cliffs that overhang the Seward Highway just south of Anchorage. Here, a few minutes drive from downtown Anchorage, rocky bluffs where the Chugach Mountains meet the wide, muddy tidal flats of Turnagain arm are home to one of Alaska’s most expansive bolted climbing areas.

Most of the climbs start just off the highway and ascend up crumbly, moss and lichen covered schist. It’s hard to call it “sport” climbing, but most of the routes are bolted, single pitch outings. And, while you’re rarely more than a stone’s throw from the Seward Highway, the views out over Turnagain Arm and up towards the glaciated peaks at it’s end are stunning. On a clear day, I’m told you can even see Denali out across the inlet.

Sunrise Ridge, about 20 minutes south of Anchorage, is one of the only long, multi-pitch adventures on the Seward Highway, and it’s where we chose to stretch our legs in the endless sunlight of an early July evening. With a number of different variations, and lengths ranging from three to five pitches, the ridge is a popular route, especially as a post-work solo among local Anchorage climbers.

The climbing was easy, fun, and some of the chossiest rock I’d ever been on. Three bolts up the first pitch, I pulled off a handhold. Two bolts above that, I lost my footing on a long section of crumbling shale, raining pebbles down on Malcolm while I tried to excavate ridges for my feet and hands from the pile of tiny rocks. The crumbling rock and collapsing holds were a quick awakening to the unique fun that is climbing in Alaska.

We arrived in Seward late the next morning. A fishing village that’s embraced the booming tourist trade, Seward is home to a number of guiding services for the nearby Exit Glacier, Harding Icefield, and Kenai Fjord National Park. I hoped we could get some beta from local guides, but most were already out with clients, and so we got mostly shrugs and a few dire warnings to be careful of trying to access any rock on private property when we asked around for beta. One local kayak guide, who let us in on the location of some of the best shoreline camping in the region, told us she had friends who had put up a bolted route somewhere in Resurrection Bay, but she couldn’t remember sure exactly where it was. Gesturing to a map on the wall of her office, she vaguely pointed at the bay’s entire eastern shoreline.

We wanted to go light, but also had absolutely no clue what we were getting ourselves into. So, I carefully packed our rope, a double rack and whatever slings and hardware I could scavenge from my van into dry sacks.

We paddled for three days past cliffs and sea spires, but none with a landing spot for our kayak, calm enough waters to attempt belaying from our tiny boat, or rock that looked safe to climb. I thought about free soloing a few of the spires, but couldn’t puzzle out a way to get onto the rock that didn’t involve some serious time in the freezing ocean. So, we filled our days with paddle strokes, salmon fishing, whales, seals, bears, otters and the countless sea birds that call the Gulf of Alaska home.

On the fourth day, we arrived at a protected beach near the edge of Kenai Fjords National Park called Porcupine Cove. A single basalt cliff line rose above the high tide line, split by a prominent crack stretching to the dense forest some 60 feet above. Beside it, a massive block, likely another cliff that had collapsed sometime in the past.

After we landed, set up camp, and ate lunch, I dove into the thick brush above the cliff and found some decent trees to set up an anchor. Rappelling the route for inspection, it looked promising. The upper section was littered with detritus from the forest above, but the rock looked OK. The crux would be a short overhanging section of rotten rock, but below that was a splitter crack. I looked out over the ocean, and, as if on cue, a sea lion popped it’s head from the waves and stared back at me dangling from the cliff.

After a few technical face moves, I made my way into the crack. The rock felt weird, almost like climbing on a chalkboard, but the hand jams were bomber, there were plentiful footholds, and I was on toprope. It felt like solid 5.9. Starting to feel the flow, I made my way up the lower crack, stopping just below the overhanging crux.

From there, I had two options. The direct line would follow the crack into the overhang, through a couple powerful moves on rotten rock onto an upper ramp to the final, I hoped, easy slabs above. The other was to step far to the left, onto an exposed, blank looking section of near vertical slab.

“Take!” I yelled down, sitting back into my harness to weigh my options. From above, and from the ground, it had looked like the chalkboard-esque rock continued up the entire route. But now, halfway up, I was staring at crumbly, dark gray schist. As I hung there, feeling around the holds on the overhang, the wall was dissolving under my feet. It seemed like every second hold snapped off in a rain of pebbles, moss, dirt, and other assorted choss.

Eventually, I decided on the lefthand route. I pulled two more moves up the crack and stepped left, easing my toes onto the thin edges and balancing my way onto the exposed slab. I wished I had set the anchor more to my left, realizing a fall anywhere above me might start a nasty pendulum, swinging me into the crumbly, jagged edge of the overhanging section.

Precariously balanced, I exhaled, sucked my hips to the wall and started up the slab. The first few holds felt good, and my confidence was starting to return when I heard an inaudible popping noise and looked up to see the edge I had using for my right hand had come off the wall, flaking off like a giant fish scale. I dug my toes in and held tight with my other hand in a sort of lopsided, desperate starfish pose. My face pressed against the dirty rock, I inhaled quickly, sucking in dusty, dried moss.

Thankfully, I held on. I would have been safe either way, held in place by the toprope, but I didn’t relish the idea of taking a big swing into the rocks to my right, so I downclimbed below the overhang and had Malcolm lower me to the beach. It was his turn.

Malcolm quickly dispatched the lower section of the route, reached the crux, and tried to muscle directly up the crack. He made it about four moves before pulling out a massive chunk of rock and dirt, and then lowering back to the deck.

We each tried again half a dozen times, even exploring a potential face climb to the far right of the crack. But each time we hit that band of crumbling schist, pulling and kicking off holds we had depended on during previous attempts. As afternoon became evening, it was clear we weren’t getting up this wall on a toprope, let alone climbing it clean from the ground up.

I pulled the rope, Malcolm bushwhacked up to clean the anchors and I resigned myself to bouldering on the nearby block. It was fun, with a couple challenging problems on it’s one overhanging side, but the ridiculousness of our plan was starting to weigh on me.

I laughed, because frankly, there’s nothing else to do when you spend three days on approach to fail to toprope a single-pitch climb. Over dinner, we talked about our plan to cross Resurrection Bay the next morning and start searching for the mythical route we had heard of back in town. That night, we slept beside bear tracks on a narrow stretch of beach between the ocean and a tiny lake.

We woke up to rain. Like a cold, gray sheet, the water fell down, sideways, and sometimes even up from the ocean. From our conversations with guides in town we knew this kind of weather was more the rule than the exception and so, weather window closed, we packed up camp and set out, paddling the whole way back to Seward in one long day.

North of Anchorage, sandwiched between the Matanuska and Susitna Valleys, the Talkeetna Mountains are one of Alaska’s best kept secrets. They are small, as far Alaskan mountains go, and lack famous summits like Denali, Hunter, or Deborah. But, what they lack in height and fame, the Talkeentas make up for in something I was desperate to find, easy to access granite.

About two hours drive north of Anchorage, past the city of Wasilla— famous as the place where Sarah Palin got her political start on city council— lies Hatcher Pass, a high mountain road home to the largest collection of developed granite climbing in Alaska. Lucky for us, the rains that had socked us in from Seward back to Anchorage seemed to be avoiding Hatcher Pass.

We decided to start in the Archangel Valley area, lured by the promise of 10-15 minute approaches. Driving up the rutted out dirt road, we entered a sweeping alpine valley, complete with babbling brooks, rolling green and yellow tundra, and towering granite cliffs. It was the first time I’d ever driven to alpine climbing.

We spent our first afternoon exploring the rock closest to the road, ticking some moderate crack climbs off, warming up and trying to make sense of the guidebook ratings, scratching our heads when, more than once, 5.8s gave us more trouble than much harder routes.

The next day, we turned out eyes to Toto, a classic six pitch 5.10 Hatcher Pass trad route a stone’s throw from our campsite. As I started leading up the first pitch, it felt good to be back on granite, to have a renewed faith in our gear placements, and feel like most of the holds would stay on the wall.

The first two pitches went easily. Pitch one was another confusingly hard, but fun, stretch of 5.8. Pitch two was easy 5.7 with a weird move through wide cracks near a mid-pitch belay station. Pitch three was a wandering stretch of 5.8 climbing that bounced between a bolted arete and a run-out slab where you had to excavate gear placements from beneath a mix of living and dead moss and grass. It was one of the strangest sections of climbing I had ever found, something I was starting to realize was par for the course in Alaska.

Next was a sustained, 5.9+ thin finger crack that ended below a section of the climb that had collapsed in a recent rockslide.

Rain started falling around halfway through my lead, but with much grunting and atrocious style, I finished the pitch just as the precipitation started to darken the low angle slab between the top of the crack and the belay station.

“It’s just spitting, it’s fine,” I muttered to myself as I set up the anchor.

The wind and rain picked up as Malcom made his way up the pitch, valiantly finding traction for his feet on the rain slicked quartzite. As he topped out the crack, I smugly dismissed the rain, just in time to watch his legs fly out from under him, the wet rock and lichen conspiring to form an icy slick surface on the slabs.

He recovered and picked his way gingerly up to the belay where we debated our options. I wandered out to the start of the next pitch, a gut-wrenchingly exposed stretch of 5.9 around a blind corner.

“Maybe if the rain lets up?”

Malcolm shrugged, happy to follow if I was willing to lead. I reached around toward the crack I would have to climb and wiped a pool of water from the rock into my palm. We were going down.

Our descent took four hours when I managed to get our rope stuck on the first rappel, forcing me to jug all the way back to the anchors, rebuild the rappel, and descend a different line. We were drenched and shivering by the time we made it back to the van. But, I was excited, it was still the most consistent climbing we had managed to do in all our time in Alaska.

The next day was clear, sunny, and warm. Still tired from our attempt on Toto, we spent a lazy few hours climbing single pitch trad routes on the Monolith, another nearby crag. Nothing was standout memorable, save for getting shut down on a 5.9 route called Zig Zag, but the climbing was fun and relaxing after our previous day’s epic.

That night we ate peanut butter noodles and made a plan to climb High Dive, another classic Hatcher Pass multi-pitch, the following day.

The sun was burning when we started down the Reed Lakes Trail the next morning. We hiked for an hour and a half, passing turquoise alpine lakes, waterfalls, dozens of day hikers, a few backpackers, and what looked like awesome single-pitch climbing and bouldering in the Lower Reed Lakes area.

Eventually, we arrived at a larger lake and picked our way to the far shore where a series of granite cliffs stretched up alongside a wide, sweeping waterfall. We racked up as clouds started rolling in over the mountains.

The first two pitches were classic, easy Alaskan trad. In other words, they wandered, had weird grassy run-outs, and required digging out gear placements. The third pitch, ostensibly the reason to climb the first two, is the real fun part. Twin cracks stretch up a sheer granite headwall, hanging you out over a primordial alpine landscape, complete with rolling clouds, shimmering lakes, and summer snow-patches hanging near the summits of the surrounding peaks.

It was a perfect stretch of climbing, fun-hard with easy gear placements, powerful moves, and one of the most picturesque topouts I’ve ever found—a tiny platform under a roof that offers a view, on a clear day, all the way to the ocean.

Unfortunately, I only had the view for about 30 seconds. As Malcolm called up to confirm he was on belay, the clouds picked up speed, pouring over the surrounding peaks down towards the lake below. He dispatched the pitch quickly, but it was starting to rain as we moved on to the short 5.6 section that finishes the route.

We climbed quickly as the rain picked up. After a quick summit high-five, I coiled the rope and we started to walk off, deciding against rappelling the route in the coming weather, our experience on Toto still fresh in both our minds.

The skies opened up, letting loose a deluge of biblical proportions, immediately making me regret my decision to walk down a wet grassy slope in my climbing shoes. We slid, slipped, and shimmied down the slope, alternating between boot-skiing in rock shoes and glissading on the wet grass.

I was soaking wet when we arrived back at the base of the climb. But, I was ecstatic. We had managed to climb an entire route in Alaska. We hadn’t retreated because of choss, been rained off, or been shut down by one of the countless natural forces that seem to conspire against anyone adventuring in the 49th state.

We trudged back the van on muddy trails, smiling wide and soaked to the bone. All told, I only managed to successfully climb two moderate multi-pitch routes in Alaska. Measured against a failed Arctic expedition, a questionable trip to climb in Resurrection Bay and countless other rainouts and failures, it shouldn’t feel like a successful trip. But, if I learned anything during my summer in Alaska, it’s that failing and changing plans comes with the territory, just like choss and rain.

Special thanks to Kelsey Gray for writing the indispensable Alaska Rock Climbing Guide and to the Alaska Rock Gym, the best place in Anchorage to retreat when the weather shuts you down.

The post Choss and Rain: Climbing (and Failing) in Alaska appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

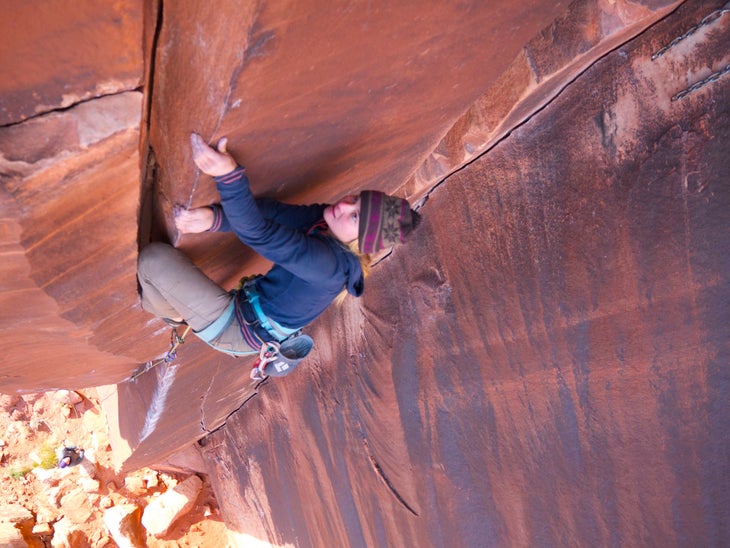

The legendary climbing destination Indian Creek falls within the Bears Ears National Monument. Photo: Bureau of Land Management/Flickr; CC BY 2.0 “We have a problem in Utah,” Congressman Ryan Zinke, President Donald Trump’s nominee for Secretary of the Interior, lamented during his mid-January confirmation hearings on Capitol Hill. He was answering questions about the fate … Continued

The post In Depth: Bears Ears and the Ongoing Battle to Protect U.S. Climbing Areas appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

“We have a problem in Utah,” Congressman Ryan Zinke, President Donald Trump’s nominee for Secretary of the Interior, lamented during his mid-January confirmation hearings on Capitol Hill. He was answering questions about the fate of the Bears Ears National Monument, the new 1.35 million acre protected area created by President Barack Obama on December 28, 2016.

While the Bears Ears monument designation was celebrated across environmental, outdoor, and Native American communities, it had a special significance for climbers. It wasn’t just that the designation protects Indian Creek, Lockhart Basin, Arch Canyon, Comb Ridge, Valley of the Gods, and dozens of other developed and yet-to-be-discovered climbing areas. It was that, for the first time, an official White House monument declaration cited the important role of climbing in the rationale for protecting the area.

“After hundreds of hours of targeted advocacy work in DC and Utah, this is the first national monument proclamation to specifically acknowledge rock climbing as an appropriate and valued recreation activity,” a post on the Access Fund’s website read.

Not everyone was on board with the celebration. Minutes after the new monument was announced, the Utah Senate Majority Leadership released a statement calling it “President Obama’s ‘midnight monument’ designation in southern Utah.” Orrin Hatch, Utah’s Senior Senator and chair of the Senate Finance Committee, took it a step further, labeling the Bears Ears designation as “an attack on an entire way of life.”

Erik Murdock, Policy Director at the Access Fund, disagrees. By his telling, the story of the national monument was a long one, with rigorous assessments, consultations, and no shortage of twists and turns.

“We didn’t get into this southeastern Utah lands management business six months ago, we got into several years ago,” he explained, walking through the Access Fund’s work to protect the climbing areas within the Bears Ears region. First through the Utah Public Lands Initiative, a piece of legislation championed by Utah law-maker Rob Bishop, and then through the pursuit of a national monument designation.

“When it became clear that the Public Lands Initiative was not going to be a good bill for the climbing community, for the Native American community, and for the environmental community, was not going to get a vote in Congress and was not going to be successful, we recognized that the only way to protect the Bears Ears region and Indian Creek was through the Antiquities Act.”

Despite this, opposition to Bears Ears has moved from condemnations to concrete action. In early January, Mike Noel, a Republican Congressman from Utah, announced plans to urge Donald Trump to overturn the Bears Ears designation and reduce the size of Grande Staircase Escalante National Monument, another protected area in Utah. Noel had previously described the Bears Ears National Monument designation as akin to the “unilateral tyranny exercised by the King of England against the American colonies two and a half centuries ago”. Later that month, amid protests and chants of “shame” in the Utah Statehouse, state lawmakers passed two resolutions calling for the President to do the same.

In the midst of this, Congressman Zinke has refused to come out clearly on either side of the debate. When asked during confirmation hearings, he replied that “it’ll be interesting to see if the president has the ability to nullify a monument.” While he’s non-committal, many in the outdoor and climbing communities are concerned about the rising opposition to Bears Ears National Monument.

During January’s Outdoor Retailer show, a major outdoor industry tradeshow held twice a year in Salt Lake City, Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard and Black Diamond founder Peter Metcalf each published letters urging politicians to abandon the fight against the monument designation. Chouinard went so far as to suggest an outdoor industry boycott of future Outdoor Retailer shows in Utah.

“The outdoor industry creates three times the amount of jobs as the fossil fuels industry, yet the [Utah] governor has spent most of his time in office trying to rip taxpayer-owned lands out from under us and hand them over to drilling and mining companies,” wrote Chouinard. “…I say enough is enough. If Governor Herbert doesn’t need us, we can find a more welcoming home.”

In early February, after Utah Governor Gary Herbert signed the state resolution, Patagonia made good on that threat, announcing that they would be pulling out of upcoming Utah Outdoor Retailer events.

But, according to the Congressional Research Service (CRS), Herbert and Utah state Republicans may have a problem getting Donald Trump to follow through on their motions. According to a November 2016 report from the CRS “the Antiquities Act, by its terms, does not authorize the president to repeal [national monument] proclamations.” The reason, they argue, is that presidential power under the Antiquities Act is granted by congress, and as such the president lacks the “implied authority” to overturn a designation.

Matt Kirby, who works on the Sierra Club’s Our Wild America campaign, agrees.

“We don’t think [Trump] has the authority to undo it, and I don’t think most legal scholars think he has the authority to undo it.”

Instead, the CRS report concludes, revoking a national monument designation requires an act of Congress. Of course, this is only based on what scholars and activists think “should” happen. With nothing tested in court, and no precedent for an executive order of this kind, anything is still possible.

“It is entirely plausible that President Trump would try to overturn a monument designation with an executive order, while at the same time Congress introduces the bill [to overturn it],” the Access Fund’s Murdock explained. On top of that, he argues, both congress and the president can shrink a national monument, and if all those avenues prove challenging, President Trump could cut off the resources that Bears Ears National Monument needs to get up and running.” In fact, Murdock points out, Trump’s federal hiring freeze may already be doing that.

“The first thing that the BLM needs to do is to hire a monument manager. Once a monument manager is hired, then you can start assembling the advisory committees and you can start the process to develop a monument management plan which takes a couple of years…from the information we have today it appears that the government is slow-walking this process.”

Bears Ears isn’t the only place where questions about the fate of protected lands are surfacing.

A few days after the letters from Chouinard and Metcalf were released, more than 100 outdoor brands and organizations—including Mountain Hardwear, Petzl, and REI—signed the Outdoor Industry Association’s “Together We Can Defend Our Public Lands” open letter.

“This is not a red or blue issue. It is an issue that affects our shared freedoms. Public lands should remain in public hands,” the letter read, imploring politicians to stand up to policies that “threaten to undermine over one hundred years of public investment, stewardship, and enjoyment of our national public lands.”

Their concern originates in the language of the 2016 republican electoral platform, which calls for large scale transfers of federal public lands to state management.

John Walbrecht, President of Black Diamond Equipment and a signatory of the open letter, went a step further, telling Climbing that “it is an American right to roam in our public lands and have access to outdoor recreation. The people of the United States share equally in the ownership of these majestic places. Today, we are more committed than ever to protecting and preserving these lands.”

For the Sierra Club’s Matt Kirby, this kind of united front among climbers and other outdoor enthusiasts is a good sign. As he sees it, Republican victories last November are emboldening politicians pushing the land transfer agenda.

“We saw the opening salvo when the House passed a rules change that would essentially make selling public lands budget neutral, making it easier to sell them off,” he explained, referencing the passage of a House rules package that allows land transfers to be proposed without an accounting of the economic value of those lands. “Now we’re seeing that followed up with Representative Chaffetz from Utah, who introduced a bill that would sell off over 3 million acres of public land.”

In early February, Chaffetz withdrew House Bill 621, a piece of legislation to “dispose of” over 3.3 million acres of mixed use BLM land across Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, and Wyoming. But, while he withdrew HB 621, Chaffetz left another bill, HB 622, on the table. If passed, this bill would hand law enforcement on federal lands over to the states, including laws related to both environmental protections for, and acceptable uses of, public lands.

For climbers, all of this should be setting off alarm bells. Nearly two thirds of climbing areas in the United States are on public lands. In the eyes of many, this makes attacks on national monuments and public lands a sort of Death Star on the horizon of climbing access.

So what is President Trump’s stance on the issue? In word, confusing.

During the 2016 election campaign, Trump opposed land transfers, telling Field & Stream magazine that he wants “to keep the lands great, and you don’t know what the state is going to do. I mean, are they going to sell if they get into a little bit of trouble? And I don’t think it’s something that should be sold.”

His son, Donald Trump Jr., went even further. Last September, while he was actively campaigning for his father, he told a Colorado TV station that “we want to make sure that, that land, public land, stays public. That’s one of the places that we’ve really broken away from conservative dogma.”

Ryan Zinke has also opposed land transfers, describing them as “an extreme proposal.” But, as Kirby explains, that only tells part of the story.

“There has been a sense of optimism that the president and representative Zinke are, on this issue, in a different step than their Republican colleagues. But, all we know is Zinke’s voting record.”

In 2015, the League of Conservation voters gave Zinke a 3% score for his environmental record. In that same year, he got an F from the National Parks Action Fund for his record on protecting National Parks. In his first term in office, he voted among other things, to weaken controls on air and water pollution in national parks and supported moves to limit the president’s ability to designate new National Monuments under the Antiquities Act.

“All we know is that he voted to pass that rules change that would make selling off public lands easier. All we know is that he voted for a bill in the last Congress that would have turned over management of a huge swath of forest lands to state control making it federal land in name only. All we have to go on is his record, if we take him at his word he doesn’t want to sell off public lands, but if we look at his record, it’s a very different story.”

Zinke and Trump have also been emphatic in their support for expanding resource extraction on public lands. In the same interview with Field & Stream, Trump answered a question about extraction on public lands stating, “I’m very much into energy, and I’m very much into fracking and drilling.”

In his America First Energy Strategy, which replaced the White House’s climate change website, Trump pledges to open up “$50 trillion in untapped shale, oil, and natural gas reserves,” most of it on public lands. Asked about this during his confirmation hearing, Zinke gave it a glowing thumbs up.

But, Kirby argues, expanding extraction on public lands sounds more like Trump “talking a big game” than something that’s in the cards.

“Between 2009 and 2016 the BLM offered 29 million acres of public land up for oil and gas bids, and only 7 million of those acres received bids. No matter what the industry says, there’s not a whole lot of clamouring for oil and gas leases when they’re actually on the table.”

It’s a sentiment echoed by the Center for Western Priorities, a Colorado-based think tank that dug into the prospects of drilling on public lands. According to Greg Zimmerman, deputy director at the Center, “drillers have more access to public lands than they know what to do with.”

“President Trump and members of Congress appear readied to do the bidding of oil and gas companies, while undermining common-sense rules that are in place to protect American lands and ensure taxpayers receive a fair return from drilling,” Zimmerman continued, referring to rumored plans among lawmakers to repeal regulations like the BLM methane rule that requires oil companies to capture waste emissions from fracking operations. “The big winners will be billionaire CEOs, while taxpayers and communities across the United States will be forced to shoulder the burdens of fewer protections.”

Others, like John Freemuth, a public policy professor at Boise State University and former BLM advisor to the George W. Bush administration, have cast doubt on the feasibility of Trump’s drilling plans altogether. Speaking to High Country News, Freemuth explained that Trump’s plans were “talking at the myth level, not the fact level,” arguing that rewriting laws at the scale required to meet Trump’s ambitions would, among other things, unleash a tsunami of lawsuits.

Some worry that these barriers, or pressure from within the Republican party, could turn President Trump into a land transfer supporter. While this all speculative, climbers should be wary. Consider the story of Oak Flat, a massive climbing area 50 miles outside of Phoenix, AZ, as a possible worst case scenario.

In 1955, President Dwight Eisenhower issued Public Land Order 1229 exempting the land around Oak Flat from mining, instead protecting it for camping and recreation. Nearly 50 years later, Rio Tinto and BHP Billiton found copper and announced plans to build the Resolution Copper Mine within the protected area. Arizona lawmakers made several attempts to pass land transfers through Congress, but when they failed Arizona Senators, John McCain and Jeffry Lane Flake, tucked a measure to privatize 2,400 acres of Oak Flat public lands into the must-pass National Defence Authorization Act in 2014.

The Access Fund describes what happened on their website as “private back-room, closed-door negotiations between powerful members of Congress that was devoid of any public input, comment, or scrutiny”.

“Resolution [mining company] has decided that the way that they need to develop that copper resource is so destructive that you could not do that if it were in the hands of the federal government,” Murdock explained. “Those senators said that they believe the benefits to Arizona outweigh the cost of losing those lands.”

Oak Flat isn’t a perfect example of what could lie ahead. For one, we can only speculate as to what motivated those Arizona Senators to attach a massive land transfer to must-pass legislation. Second, the Oak Flat land transfer would take federal lands and hand them directly over to a private corporation, not the state. This runs counter to the land transfer movement’s major argument that the constitution supports, even calls for, land transfers. Even so, it’s a poignant cautionary tale.

“It’s a good lesson that although a President may protect a certain piece of real estate, that does not necessarily mean future legislators cannot reverse that protection,” Murdock said.

It’s a chilling prospect to consider that is made all the more worrisome by Arizona congressman Paul Gosar’s late-January introduction of House Resolution 46. If passed, the resolution could repeal barriers to drilling within national park boundaries, something the National Parks Conservation Association says could mean:

“Leaks and spills could go unpunished without NPS authority to enforce safety standards. Companies would be able to build roads through national parks to begin drilling, such as the 11-mile road through the heart of Big Cypress National Preserve, built to reach an oil and gas lease. Drilling companies would not be required to inform parks or park visitors about when or how drilling operations would occur.”

The good news is that, as far as we know, no one is looking to start drilling at the base of El Cap anytime soon. Gosar’s proposal only applies to national parks where the US government does not own subsurface mineral rights. This keeps Yosemite safe. But, it would apply to the Grand Teton, one of 42 parks that the Centre for American Progress found either are, or could be, threatened.

While drilling in national parks, attacks on national monuments, and land transfers together present a major threat to the future of climbing and outdoor recreation, people like Murdock, Kirby, and Walbrecht are confident that if climbers get active in protecting the places they love, we have a great chance at preserving them.

Citing the Access Fund, who Black Diamond partners with on their Rock Project initiative, Walbrecht gets straight to the point, “Today, one in five climbing areas in the United States is at risk due to an access issue”.

But, he explains, climbers are well positioned to help stop that from happening.

“We know that no one loves climbing landscapes and the experiences they offer more than climbers themselves.”

The post In Depth: Bears Ears and the Ongoing Battle to Protect U.S. Climbing Areas appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

An activist performs some sketchy aid climbing to scale a moving oil rig in the pacific ocean. Photo: Courtesy Greenpeace International Late in the summer of 2010 I found myself hanging from a fixed rope in the middle of rural Minnesota. I was blindfolded, trying to move laterally from one fixed line to another using … Continued

The post Climbing for Change: A Brief History of Action Climbing appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Late in the summer of 2010 I found myself hanging from a fixed rope in the middle of rural Minnesota. I was blindfolded, trying to move laterally from one fixed line to another using loops of accessory cord tied into prusiks. Why? To stop global warming.

That was my formal training in action climbing. Over 10 days at a camp in the midwestern woods, I learned how to build anchors, rappel, perform rescues, and tie a lot of knots. The camp catapulted me deeper into a world of environmental activism, but also proved to be an unexpected pathway to rock climbing. I had climbed a few times before, but it wasn’t until I became an action climber that I really started climbing rock and began to learn about the the relationship between climbing and activism.

The formal history of action climbing starts in 1978 when New Zealand activists staged the first “tree sit,” climbing high into the trees to stop logging in an area now known as Pureora Forest Park. That same year Joe Healy, a then 25-year old navy veteran and Greenpeace activist, scaled the Sears Tower in Chicago to protest whaling.

“It’s the world’s biggest animal and it’s dying, and it seemed like the worlds tallest building was a good place [for the protest],” Healy told the Chicago Tribune.

His ascent took four hours. Healy drew on his self described, “four years of mountaineering experience” and used what the paper described as “homemade brackets,” a kind of aid climbing system that hooked into grooves on the outside of the building used by window washers.

“The first generation of action climbing definitely came from people who were climbers from other worlds—rock climbers, cavers, mountaineers, etc,” Matt Leonard, a climate change activist who has participated in, and trained people for, action climbing for over two decades explains. “They took those skills and pioneered creative ways to apply them to activism.”

Leonard, who now works for the climate change group 350.org and the vertical dance company Bandaloop—alongside climbing legends like Hans Florine and Peter Mayfield—describes how action climbing formed into a discipline in itself through the 1980s.

“The ’80s were an incredibly creative era, as techniques and systems were refined, bold action ideas were brainstormed—I’m sure many around a campfire or crag—and then some big risks were taken to carve new ground of what was possible.”

By the 1990s, action climbing started to get codified, with formal trainings and safety considerations on par with, if not exceeding, those for rope access work.

“A lot of people don’t realize that we do pay attention to safety standards, we do recognize there are going to be risks to partake in these activities,” Basil Tsimoyianis, a long time Greenpeace action climber and manager of the website Rope Guerrilla, explains.

Rope Guerilla, self described as a “a project dedicated to activists, rebels, and radicals in the vertical world” is a window into the world of climbing activism. It compiles resources, describes actions in detail, and dives deep into climbing-as-protest. According to the site, there are four main goals for action climbing; photo ops, direct communication, occupations, and blockades.

“You can’t buy an ad on the front page of the New York Times, but I’ve been a part of several activist climbing actions that got full-color, above-the-fold coverage,” says Leonard. “And of course, climbing also has been instrumental in direct action—giving activists new tools to protect old growth redwoods from bulldozers, stop illegal whaling ships, shut down polluting coal power plants, and much more.”

Most people probably know, or at least have seen, climbing actions like the 1999 banner hang at the World Trade Organization protests in Seattle. For a long time, the main use of climbing in activism was to hang banners like that one. But recently, like the early trend in rock climbing, action climbing is adopting a sort of ground-up ethic.

“A lot people are familiar with banner hangs, and those still happen a lot, but I think people are trying to move beyond that,” Tsimoyianis explains. “Bottom-up climbing allows for the story to be unfolded.”

In April 2015, six climbers boarded Shell’s Polar Pioneer when it was en-route to drill for oil in the Arctic. It wasn’t the first time that Greenpeace had climbed something like this, but the Polar Pioneer ascent started with what Tsimoyianis describes as “a section of aid climbing that many would try to avoid.” Using a stick clip, a hook and a caving ladder, a climber led his way up the side of a moving oil rig in the middle of the Pacific Ocean.

“The fact that this style of climbing was done on a moving vessel at high seas is extraordinary,” Tsimoyianis wrote.

In some ways, this move towards ground-up action climbing is a call back to Healy’s 1978 ascent. But, as Tsimoyianis argues, it also connects to something deeper, something that ties into climbing’s growing appeal.

“[Ground-up climbing] draws the attention of people who are fascinated by that, whether they’re climbers or not.”

Perhaps the best example of this, was the 2013 ascent of the London Shard by an all female group of Greenpeace climbers. The ascent unfolded over 16 hours, during which they held the rapt gaze of international media. When they topped out and unfolded their “Save the Arctic” banners, the media coverage was global, competing in scale with Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgensen’s 2015 ascent of the Dawn Wall.

Action climbing sits in a complex space between climbing and politics. For me, learning how to climb a rope and drop a banner was a pathway into the climbing community. For others, like Tsimoyianis, action climbing was a way to use skills he learned on the rock to express his politics. For a lot of climbers, action climbing is probably little more than hippies on ropes. But, whatever the case, it’s a part of the climbing world. And, who knows, Alex Honnold is an environmentalist who dedicated part of his memoir to buildering. Maybe we’ll see him freesolo Healy’s 1978 route in a Greenpeace t-shirt someday.

The post Climbing for Change: A Brief History of Action Climbing appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Photo: Andrew Burr Alex Honnold wants you to vote: “Climbers should actually vote, it’s the bare minimum for making the world a better place.” He’s not alone. Over the past few months outdoor advocacy groups, athletes and companies have been rolling out campaigns and get out the vote efforts in the lead up to the … Continued

The post How Much Political Influence Do Climbers Have? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Alex Honnold wants you to vote:

“Climbers should actually vote, it’s the bare minimum for making the world a better place.”

He’s not alone. Over the past few months outdoor advocacy groups, athletes and companies have been rolling out campaigns and get out the vote efforts in the lead up to the 2016 presidential election. One of the most ambitious is Patagonia’s #VoteOurPlanet campaign, the largest political effort the company has ever launched in twelve years of electoral work.

“We’ve ramped it up this year, we’re really doubling down,” Hans Cole, Patagonia’s Director of Environmental Activism explains. “We’ve already put $1 million in investment into this campaign in grants, to community groups that are getting out the vote, in videos and images to tell stories about environmental issues that people should care about, and into resources on our website so people can really get informed and learn what it means to vote our planet.”

Patagonia also announced plans to close down their operations, retail stories, head office and their distribution operations on election day to let their staff not only vote, but help efforts to get out the vote. It’s a big and bold campaign connected to other local and national campaigns, like Protect Our Winters’ “Drop in and Vote,” which has dubbed 2016 “the most important election in a generation.” With all this effort to get climbers and the outdoor community to make a larger political stand, it begs the question—do climbers really have a political impact?

According to the Outdoor Foundation, six million adults will climb in the Unites States this year. That’s a lot of people, especially while you’re waiting to get on a classic route. But how does it translate politically? In 2012, 129.1 million people voted in the United States. If every climber voted, we’d make up 4.5% of all voter turnout, which is nothing to scoff at. The AFL-CIO, one of the major labor unions courted by politicians—and a powerful political entity—is twice that size, at 12 million members. But, the number from the Outdoor Foundation includes everyone, including any person tying in for the first time at the gym today and, unlike groups like the AFL-CIO, there’s no climbers union organizing climbers politically.

Knowing this, you might dismiss the idea that climbers hold political power, but according to Brady Robinson, Executive Director at the Access Fund, you would be wrong.

“We have quite a bit of pull, and I think the reason for that is people acknowledge that climbing participation is on the rise and that we represent a vocal and passionate constituency. We’re people that know the land well, for the most part we’re good users and stewards of the land, and there’s a significant economic activity that’s associated with our sport.”

Robinson points to a study released earlier this year by Eastern Kentucky University examining the economic impact, what he calls the “climbing economy,” in counties near the Red River Gorge, including three of the poorest counties in the United States. According to the research, climbers pumped $3.6 million dollars directly into the local economy and created $2.7 million in revenue for local businesses. While this might not seem like much, imagine that number multiplied across hundreds of climbing areas in the United States.

Much of this economic impact is just starting to be understood, and though it’s sizable, it pales in comparison to the financial scale and power of the forces that threaten climbing areas and wild spaces.

“While some individual companies and CEO’s can make political contributions that register, we [the outdoor community] don’t hold a candle to the kind of money that the oil and gas industry, the gun industry, and other industries are spending this election,” Robinson explains.

Without the financial resources of the fossil fuel industry or other similar players, climbers, climbing advocacy groups, and the outdoor community have to play a different game. Right now, an iconic example is the ongoing battle over an area in southeastern Utah known as the Bears Ears.

Two visions of land use have emerged for Bears Ears, which is home to iconic climbing areas like Indian Creek, pristine wilderness, and countless sites that are sacred to local Native American tribes. On one side, Republican lawmakers have put forward a plan that would see much of the land privatized and handed over to oil and gas development. On the other, the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal coalition has proposed a plan to make the area a National Monument, a plan that has been supported by a broad coalition that includes a lot of climbers and climbing advocacy groups like the Access fund.

“It seems like a lot of the people who are stepping forward to get involved are either climbers or people interested in climbing,” said Robinson. “There is a sense that the climbers show up, they are putting in the time and the trail days, going to public meetings, waiting in line in the blistering sun for hours…for whatever reason [climbers] keep showing up.”

One of those reasons, and perhaps the reason this campaign has become so important to the Robinson and the Access Fund, is what lies within the Bears Ears; Indian Creek.

“There just isn’t another place like Indian Creek and the Bears Ears region in the world…if we’re not going to fight to protect this, what are we ever going to fight for?”

It’s not just the Access Fund. In 2015, Patagonia released a film called Defined by the Line and launched their own campaign fighting to protect the region. The film tells the story of climbing in the Bears Ears, and profiles the work of Friends of Cedar Mesa, a local organization helping to lead the campaign on the ground.

“What we got really excited about with the Bears Ears was the opportunity to introduce the topic of protecting public lands to our climber audience and to find ways for climbers to really take action around something they should care about,” says Cole.

While working on the Bears Ears campaign, Cole discovered that climbers “have a really authentic voice and ability to speak out on behalf of the places they get out and climb.” He argues that it can go a long way in not just motivating climbers, but the wider outdoor community— and even broader society—to care about these places.

“While not all climbers think of themselves as activists or politically engaged, there’s a huge opportunity for that group to get more involved and to use their voices to protect some of these places that are really at risk.”

Alex Honnold believes in the climbing community’s ability to affect change. While most of the work of the Honnold Foundation is in providing support to environmental non-profits, it’s his work bringing renewable energy to low-income communities featured in Sufferfest 2 and the Vice Media documentary about his trip to Angola to climb and install solar projects that most of the world knows about.

“Those trips were sort of attempts to bridge the environmental work with climbing in a more direct way,” Honnold explains. “They’re both sort of experiments because it’s hard to make the environmental projects look sexy. I think we did an alright job of it, but I don’t know the best way to make those go together.”

The challenge lies in one question: How do we increase our political impact? While both Robinson and Cole are optimistic that Bears Ears could be granted protection by the Obama administration before he leaves office in 2017, this fight is still a single skirmish in the unfolding battle over public lands. Add climate change to that, and you have a mix that presents a new kind of challenge to climbers, one that is about far more than ensuring access or protecting a wild space.

So, do climbers have political influence? The answer is almost definitely yes. Obama did tweet about the Dawn Wall, after all. But, at a time when one major political party is determined to sell off our public lands, that power needs to grow.

The post How Much Political Influence Do Climbers Have? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

The privately owned Sky Top crag at New York’s Shawangunk Ridge, where a day of climbing can cost upwards of $400. Photo: E Chu/Flickr; CC BY 2.0 Imagine your local crag surrounded by a fence. Inside, the sport routes have been secured with fixed gear. The moderate routes have permanent toprope anchors, like the kind you’d find … Continued

The post Ski-Style Climbing Resorts and the Future of Climbing Access appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Imagine your local crag surrounded by a fence. Inside, the sport routes have been secured with fixed gear. The moderate routes have permanent toprope anchors, like the kind you’d find in a gym. There are changing rooms and a cafe-bar with hot espresso, cold beer, and overpriced pizza.

At the rental stand, a standard rack can be borrowed for $20 a day, complete with a guarantee that each piece has never been dropped, and inspected by an expert every evening. A short drive away, there are hotels with hot tubs to sooth sore muscles and a craft brewery for “après-climb” socializing.

In a sport where the difference between a developed and un-developed area can be the presence of an outhouse, it’s easy to dismiss the idea of climbing crags that look like ski resorts. But, with climbing’s popularity on the rise, could pay-access crags and climbing resorts be in the future? Maybe.

According to a report from the Physical Activity Council, more people than ever are climbing in North America. Participation is growing at an unprecedented rate. Of the 170,019 new climbers that took up the sport between 2007 and 2015, nearly 150,000 started in the last year.

According to Climbing Business Journal, this growth is behind a booming indoor climbing industry. 40 new U.S. climbing gyms opened in 2015 alone, and at least 36 are expected to open in 2016. With this growth is coming money, big money. Described in Outside magazine as “investment offers [that] seem to be falling from the sky”, the bull climbing market is best exemplified by the nearly $49 million sale of New York’s Brooklyn Boulders to North Castle Partners, the fitness financiers behind names like Atkins and Jenny Craig.

But, with all this indoor climbing growth, what’s happening at the cliff?

While 170,019 people started climbing between 2007-2015, that only accounts for indoor climbing, sport climbing, and bouldering, three disciplines the researchers count together. During that same period, over 500,000 people took up trad climbing, ice climbing, and mountaineering, also counted in a group. While this doesn’t tell us exactly how many more people are at the crags, it clearly shows that more people aren’t just climbing, but more and more people are climbing outside.

“There’s more people in the outdoors,” explains Brady Robinson, Executive Director of the Access Fund. “Even if everybody is on their perfectly best behaviour, there are going to be impacts, physical impacts and social impacts…especially if these climbing areas aren’t ready for the crowds.”

To Robinson, it’s mathematically simple: more people climbing outside means more impact of the areas we climb in. Places that previously saw 20 people in a weekend, are now dealing with hundreds of climbers. That means parking areas might need to be leveled, trails formally maintained, and toilets might need to be installed where they weren’t needed before.

The Access Fund has also seen a shift in their role when it comes to supporting the climbing community.

“If we see access issues on the rise, it’s really the rise of this idea that climbing areas need to be managed,” Robinson explains, citing the Jefferson County Climbing Management Guide as an example of this new reality. Covering Cathedral Spires, the Dome, Clear Creek Canyon, Mt. Lindo and North Table Mountain in Colorado’s Front Range, the plan was designed specifically to prepare for the anticipated impacts of climbings rising popularity on the mountains.

“When we met with the people responsible for managing parks and open space in Jefferson County [they told us] ‘We’ve taken a look at how the sport has grown in the last couple of years, and when we look at the population projections for the Front Range it’s really alarming. We know if we don’t do something now it’s going to be bad; we’re going to have negative outcomes.’”

Plans like the kind in Jefferson County are few and far between. More often that not, the impacts of increased use are dealt with after the fact.

Case-in-point, the Roadside Crag in the Red River Gorge. At 9:02 a.m. on Tuesday May 24, 2011, the Roadside Crag was closed. The announcement came via a post on redriverclimbing.com from Grant Stephens, a local developer who worked to acquired the land for climbers in 2004. It read: