What are the ethics, safety, and implications of using xenon to unlock a one-week Everest summit?

The post The First Xenon-Powered Everest Climb Is Coming This Spring appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Picture yourself in your office. Your phone buzzes with a text message: Time to go! You sprint downstairs to a waiting taxi and zip to the airport, where you board an overnight flight to Kathmandu. You land, hop in a helicopter, and soar over the Himalayas to Mount Everest Base Camp, where Sherpas hook you up to oxygen. You and your guides climb the Khumbu Icefall, Western Cwm, Lhotse Face, and continue on to the summit, where you snap a triumphant selfie. You then descend 11,400 vertical feet back to Base Camp, where a helicopter whisks you to the airport, and you board your flight back home. One week after receiving the text, you’re back in your office.

Sounds like a scene from a science fiction movie, right?

In May, an Austrian mountaineer and guide named Lukas Furtenbach will oversee four paying clients on an Everest expedition that, door to door, will last just seven days. That’s about one-third the length of the speediest Everest expeditions currently offered by guiding companies. And it’s much shorter than most guided ascents of the world’s highest peak, which typically last anywhere from six to eight weeks. On those trips, climbers complete multiple acclimatization hikes up the mountain to adjust to the extreme altitude.

“Our type of expedition opens Mount Everest up to people who don’t have enough free time for the traditional experience,” Furtenbach told Outside. “We are confident they will summit. Our reputation is on the line, and our business would be impacted if we fail.”

All four clients are from the U.K., which means they will start their journeys at or near sea level. According to Furtenbach, each client is paying $153,000 for the trip.

So, what’s Furenbach’s secret to speed? In short, xenon gas. A few weeks before traveling to Nepal, Furtenbach’s clients will travel to a hospital in Germany where they will don a diving bell-like mask and inhale xenon gas. Studies have suggested that the odorless gas can protect vital organs from altitude sickness, while boosting the body’s production of erythropoietin, or EPO, the hormone that stimulates the production of red blood cells. When used alongside traditional at-home acclimatization methods, xenon gas can make the human body capable of withstanding Everest’s extreme altitudes, according to Furtenbach.

“We are doing this primarily for safety as a form of preventing altitude sickness,” Furtenbach says. “This is not about performance enhancement.”

The news of Furtenbach’s experimental tour caused a stir in the mountaineering world when he announced it in January, and in the ensuing weeks, the entire industry of guides and expedition operators appeared to wrestle with this new method. Some guides voiced their support of the experimental procedure, others chastised it, while others raised questions about safety. On January 22, the International Climbing and Mountaineering Federation, a global body that advocates on behalf of climbers, published a terse statement condemning the practice.

The ordeal has forced mountaineers and guides to revisit the ethics—or lack thereof—that climbers follow on the world’s highest peak, and to ask themselves how far climbers should go to improve their changes of actually reaching the top, and who belongs on the peak.

“The old adage, ‘Just because you can, doesn’t mean you should,’ applies in this context,” says mountaineer and longtime Everest chronicler Alan Arnette.

Lukas Furtenbach, Everest’s Technophile Guide

Furtenbach, 47, launched his own guiding business, called Furtenbach Adventures, in 2014. He made his first ascent of Everest two years later. These days, Furtenbach Adventures leads trips to 12 of the world’s 14 peaks above 8,000 meters, as well as to the seven summits, the highest peak on each of the seven continents.

His company touts its use of technological innovations that aid safety and summit success. His clients wear devices that track their heart rate and oxygen saturation during climbs. Clients also receive high doses of oxygen—eight liters per minute—on high-altitude ascents. In 2024, he took 40 paying clients to the top of Everest.

“He’s one of the more entrepreneurial guides on Everest,” says author Will Cockrell, whose 2024 book Everest, Inc. chronicles the mountaineering industry. “He’s young and hungry, and seems like he wants to appeal to the wider audience of climbers.”

In 2017, Furtenbach debuted his three-week Everest trip, called “FLASH” expedition, which required participants to use hypoxic tents at home for eight weeks prior to the ascent. The tents produce a low-oxygen environment, and sleeping in one helps climbers prepare for the thin air found in the Himalayas.

Furtenbach himself has acted as a guinea pig to test out his methods, including this new one that relies on xenon. He has personally tested xenon gas on his own body since 2019. That year, a German doctor named Michael Fries contacted him and asked if he’d undergo a test with the gas to see if it impacted his climbing. Furtenbach agreed. One week after the treatment, Furtenbach traveled to Argentina, took a helicopter to the Base Camp of 22,837-foot Aconcagua, and then ascended the peak the next day.

“It was surprising how well it worked—I was feeling so good on the mountain,” he says. “I had no altitude problems.”

Furtenbach saw the potential for using the treatment for Everest expeditions. In 2021, he again underwent xenon treatment prior to Everest’s spring season—he planned to climb the peak alongside his three-week FLASH clients. He ascended 21,247-foot Mera Peak nearby with no problem, then set his sights on Everest. But a COVID outbreak in Base Camp forced him to cancel the ascent.

In 2022, he returned having had xenon treatments. This time, he was not alone—a cameraman and a guide also did the treatment. The trio summited both Mera Peak and Everest with no problems. His door-to-door time from his home in Innsbruck was 16 days. That’s when Furtenbach got the idea for the one-week Everest trip.

“My heart rate and blood-oxygen was the same as guides who had been acclimatizing with altitude tents,” he said. “I knew that with the right logistics and backup of supplemental oxygen, one week was possible.”

Furtenbach planned to do a one-week test on Everest in 2023, but a film project involving him torpedoed that timeline. He targeted 2024, but again faced setbacks, when his two clients for the experimental trip backed out due to scheduling issues. So Furtenbach again tested it on himself, and ascended Everest from Tibet.

“This was my fifth time testing, and we could see an increase in my hematocrit of 10 percent,” Furtenbach says, referencing his blood’s percentage of red blood cells. “That’s about what you’d get after spending the traditional eight weeks at altitude during an Everest expedition.”

Can Xenon Gas Improve the Body’s Performance at Altitude?

During a xenon treatment, Furtenbach sits in a medical room and dons a mask attached to a ventilator. At first, the device pumps out pure oxygen, but over a 30-minute period, it gradually adds in xenon.

“You start to feel a little bit dizzy, but it doesn’t feel bad, and you don’t taste or smell anything,” Furtenbach says. “After 25 minutes or so, you turn it off and feel perfectly normal, like nothing has happened.”

But whether or not the gas actually helps the human body on the world’s highest peaks is still open to debate. Research into the impact of inhaled xenon on humans is still in its infancy.

In 2014, The Economist published a groundbreaking report about the Russian doping program during the Socchi Winter Olympics. The report stated that Russian athletes inhaled xenon to produce EPO and boost their blood’s ability to transport oxygen. Decades ago, pro cyclists injected synthetic EPO before competing in the Tour de France. The World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) officially added xenon to the list of banned substances for Olympic competition that year.

Two separate experiments, conducted in 2016 and 2019, sought to quantify just how much inhaled xenon could increase the body’s ability to carry oxygen. Both studies showed that inhaling xenon caused the human body to ramp up its production of EPO and also blood plasma within a few days of treatment. But neither study could conclude if this led to an uptick in actual human performance.

The 2019 study concluded: “Xenon inhalation did not increase fitness or improve athletic performance, and, given the adverse symptomology associated with dosing, our findings do not support the use of xenon as an erythropoiesis-modulating agent in sports.”

Furtenbach also points to other potential qualities of xenon—specifically, that the gas may prevent high-altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE) and high-altitude cerebral edema (HACE). Dr. Fries’s research suggests that xenon protects the brain and lungs in low-oxygen environments. But Dr. Friese’s experiments were conducted on animals. Critics point out that these tests are also inconclusive.

“His studies are interesting, but they’ve never been done on humans in protection from hypoxia,” says Dr. Peter Hackett, a mountaineer and expert in high-altitude research. “It’s a big leap from studying rodents and pigs to applying it to humans.”

But Furtenbach says that his own tests on himself have convinced him that xenon works. He told Outside that the day after undergoing xenon inhalation in 2019, he did his normal ski touring ascent at home in Innsbruck. “I was seven minutes faster without putting any effort into it,” he says. “We measured my hematocrit and could see the increase within five to eight days was dramatic.”

Plus, Furtenbach says, the xenon treatment simply supplements the tried-and-true acclimatization that his FLASH clients already complete before tackling Everest. Like the three-week FLASH clients, Furtenbach’s one-week clients will spend eight weeks sleeping in an altitude tent prior to the expedition. They will also complete a series of hypoxic athletic workouts prior to the trip.

“Xenon is just one component,” he says. “With acclimatization using hypoxic systems, one can achieve the same or even higher acclimatization than would occur at real altitude on the mountain.”

Critics Sound Off on Xenon

Furtenbach first spoke to Outside in December 2024, and predicted that his idea would likely ruffle feathers in the small world of Everest guides.

“I know there is going to be criticism,” he said. “People will say it’s doping. People will say it’s not real mountaineering anymore.”

The pushback was even harsher and more substantial than he predicted. On January 22, the International Climbing and Mountaineering Federation released a statement condemning the use of xenon. The statement called into question the science behind xenon’s use for acclimatization, and also pointed out the ethical dilemma of using a substance that’s banned by WADA. “Acclimatization to altitude is a complex process that affects the various organs/systems such as the brain, lungs, heart, kidneys and blood to different degrees, and is not fully understood,” the statement read. “Since the physiological changes take days to weeks to influence the organism, from a physiological point of view, a single, one-off drug cannot be the key to improved acclimatization or increased performance.”

But not everyone in the climbing world is as critical. In an interview with Austrian news site Der Standard, mountaineering legend Reinhold Messner, the first person to climb Everest without supplemental oxygen, called the method “fantastic.”

“I think it’s brilliant of Furtenbach to have realized what xenon can do for high-altitude mountaineering,” Messner said. “I congratulate him on his success.”

Furtenbach shrugged off the ethical questions over using the substance. WADA rules do not apply to mountaineering, and clients and guides already use a wide array of substances to artificially enhance their performance on the mountain, most notably bottled oxygen. Some mountaineers also bring an anti-inflammatory steroid called dexamethasone—or DEX—on expeditions to mitigate symptoms of altitude sickness.

Furtenbach claims xenon isn’t doping, but rather a protective measure similar to bottled oxygen.

“We are paid to be responsible and to care about the lives of our clients,” he said. “We have to do everything we can to make the climb as safe as possible. And if using oxygen or other gasses makes the client safer, then that’s what we will do.”

Still, the climbing federation wasn’t the only body to criticize Furtenbach’s use of xenon. Throughout January, other Everest guides also chimed in with pushback on the new method. New Zealand guide Guy Cotter told Outside that he viewed ascents using xenon to be “no more than a stunt.”

“My feeling about this new proposal to use xenon to dope up for Everest is ‘why all the rush?’” Cotter told Outside in an email. “An ascent of Mount Everest, when done properly, is one of the most amazing adventures on earth.”

British guide Kenton Cool told The Financial Times that, while he respected Furtenbach, he would not recommend the method to his clients. “Maybe it’s a reflection on modern-day society, where we want everything yesterday, and nobody’s willing to wait,” he said.

American guide Garrett Madison echoed that sentiment. Madison also offers rapid guided ascents on other peaks. But he said that the traditional six-week tour to Everest offers much more to climbers than just a moment spent on the summit.

“The tried-and-true ascent is a spiritual journey,” Madison told Outside. “You soak up the culture of Nepal and the culture of the Sherpa people and you get to really know this amazing environment. I wish expeditions could last longer.”

Madison said the week-long trip is just the next step in Everest’s evolution as a bucket-list travel destination. “Why not just fly up there in a helicopter and touch the top so you said you did it?” he says.

Furtenbach pushed back against the criticism in a series of emails with Outside: “For those with the time and flexibility to spend eight or ten weeks on an expedition, I congratulate them on the opportunity to immerse themselves in a new culture and environment at their own pace,” he wrote. Furtenbach Adventures also offers the traditional eight-week trip to Everest, as well as the three and now one-week tours, he pointed out.

“Everyone should be free to choose their expedition style and duration, with tolerance for differing approaches, provided no one else is harmed or endangered,” he added.

But there are lingering questions about whether or not rapid trips up Everest increase the risk. Guides who spoke to Outside stressed that patience on Everest is often a virtue, especially in years when the weather presents challenges. These days, hundreds of climbers surge onto the mountain at the same time to make the most of narrow windows of good weather. Climbers on traditional eight-week ascents can wait out the crowds.

Guides also said that acclimatization hikes on Everest give a client “mountain sense,” which can come in handy during an emergency. “There’s a lot to be gained by going onto the mountain in terms of overall preparedness,” Madison said. “You adapt to the cold and the wind. You learn the route. You get a sense of where you are on the mountain.”

Experts also expressed concern that climbers on rapid ascents may have a lower chance of survival if they were to lose access to bottled oxygen above 26,000 feet—the so-called “death zone.” At that altitude, climbers no longer breathe in enough oxygen to stay alive.

“A climber that’s been on Everest for six weeks and has done multiple rotations to Camp II or Camp IiI—if their oxygen runs out, they will be in trouble but they won’t die as quickly,” Dr. Hackett said.

Furtenbach disagreed and argued that at-home acclimatization is just as good as doing so on a mountain. Furtenbach said his clients will be hooked up to oxygen “as soon as it makes sense,” and that the four climbers on the one-week expedition would have a one-to-one or two-to-one guide-to-climber ratio. This high ratio, he says, will ensure that clients always have access to oxygen, and have the help they need in case of an emergency.

And Furtebach also pushed back on fears that Everest’s route will someday be clogged with climbers who are on rapid ascents. The expensive trips, he says, will always cater to a small number of climbers.

“The one-week expedition will always be a niche offering,” he wrote in an email. “It is decidedly not suitable for everyone and requires such extensive preparation, logistics, and financial resources that it could never become a mass-market product.”

Why Are Rapid Everest Ascents Becoming Popular?

Furtenbach’s one-week ascent represents the latest chapter in the ever-evolving history of guiding on the world’s highest peak.

In Everest Inc., Cockrell chronicled the rapid rise of Nepali-owned guiding businesses on Everest and other 8,000-meter peaks. Companies like 8K Expeditions, Asian Trekking, and Seven Summit Treks now dominate the guiding industry on Everest, in part because they offer low-cost alternatives to expeditions led by European and North American guides.

Clients can now get a shot at the Everest summit for less than $40,000 with a Nepali outfitter, versus double that with a western guide. Some Nepali companies now bring between 50 and 100 clients to Everest each year.

“Western guides absolutely recognize how hard it is to be competitive with the Nepalis,” Cockrell says. “They have to fight for their existence on the mountain, and one way to do that is being more innovative.”

Cockrell views the rise of faster expeditions as a result of the market dynamics. Furtenbach, as well as British-American guide Adrian Ballinger, offered some of the first rapid ascent using pre-acclimatization technology. Furtenbach led trips to 26,846-foot Cho Oyu and 26,414-foot Broad Peak in 2006 and 2007 that required climbers to use tents. In 2012 Ballinger led a trip up Makalu that lasted just one month, which was remarkably fast at the time. Ballinger had his clients acclimate at home by using hypoxic tents. Ballinger began offering similar speed trips up Cho Oyu and then Everest. Other western guiding companies followed suit.

“The Nepalis are doing such big numbers on these peaks, so it makes sense that other companies are going to target the high-end clients with different types of trips,” Cockerell says. “Innovation is always going to be more expensive by default.”

The proliferation of different durations—and different price points—for Everest trips, Cockrell says, is a sign that the mountain is rapidly being opened up to a wider swath of climbers. Gone are the days of the eighties and nineties, when only experienced mountaineers—or the extremely wealthy—dared to scale the peak. Like marathon running, or Ironman triathlons, climbing Everest is quickly becoming an activity for the masses.

“There’s still no easy way to climb Mount Everest—climbers are going to suffer their way up it one way or another,” Cockrell says. “What guides and companies have done is to create different versions of suffering. And they can accommodate a wide swath of people.”

“But no matter what, they still have to come down the same way Reinhold Messner did,” he says.

The post The First Xenon-Powered Everest Climb Is Coming This Spring appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Jimmy Chin just found the boot of Andrew "Sandy" Irvine—who disappeared on Everest alongside George Mallory in 1924—at the foot of Everest's North Face. It isn't answering as many questions as we'd hoped.

The post Sandy Irvine’s Remains Have Been Found on Everest. But the Mystery Endures. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

This story originally appeared in Outside Online.

German mountaineer and writer Jochen Hemmleb was scrolling through Facebook at his home in South Tyrol, Italy, on Friday when he saw a photograph that nearly made him fall out of his chair. The image showed acclaimed climbing filmmaker Jimmy Chin crouching over a weathered hobnailed boot protruding from melting ice. The boot, a photo caption proclaimed, belonged to British adventurer Andrew Comyn “Sandy” Irvine, who disappeared while attempting Mount Everest alongside George Mallory in 1924.

“My initial reaction was to think, ‘So Andrew, this is where you have been,’” Hemmleb told Outside. “After my feelings of excitement, my next feeling was of relief and then some closure.”

The discovery of Irvine’s boot sent shockwaves throughout the global mountaineering community when National Geographic published the news on Friday morning. Irvine and Mallory vanished on Everest’s upper slopes 29 years before Edmund Hilary and Tenzing Norgay became the first people known to reach the top, in 1953. According to a press release accompanying the story, a team comprised of Chin and filmmakers Erich Roepke and Mark Fisher found the boot in Tibet on a section of the Central Rongbuk Glacier just below Everest’s imposing north face this past September. The boot contained a partial sock, and the garment had Irvine’s initials and last name stitched to it.

“Any expedition to Everest follows in the shadow of Irvine and Mallory,” Chin said in a release.

Hemmleb, 53, is a global authority on Irvine and Mallory, and told Outside he became obsessed with it when he was just 16 years old. He has written 20 books about the world’s highest peak and those who have sought to climb it, and three of his titles are about the missing mountaineers.

The discovery had an even greater impact on a small group of climbers, writers, and historians who—like Hemmleb—have fixated on Irvine and Mallory. The two were part of an expedition to become the first to reach the highest point on earth, and they vanished less than 1,000 feet from the top. Fellow expedition member Noel Odell said Mallory and Irvine were “going strong” to the top at the time of their disappearance. Nobody knows whether or not they reached the summit, or how, exactly, they died.

Much like the disappearances of Amelia Earhart or Jimmy Hoffa, the enigma of Mallory and Irvine has ballooned over the decades, at times drowning out Everest’s contemporary goings-on. It’s the focus of dozens of books and documentary films. And over the years, it has spurred more than a few debates.

“This discovery brings out my whole fascination with the story all over again,” Hemmleb said. “It’s just such an emotionally gripping tale.”

In 1999 Hemmleb was part of an American expedition to Everest to try and locate Mallory and Irvine for a documentary film produced by Nova. Following Hemmleb’s research into their route, a team led by legendary climber Conrad Anker found Mallory’s preserved remains on a ledge at 27,000 feet on the peak’s north face.

“The name tag etched onto the Irvine’s sock is nearly identical to the one Conrad found in 1999,” Hemmleb said. “It feels like Andrew is on the level with Mallory now, like he’s stepped out of the shadow.”

But Hemmleb told Outside that Irvine’s discovery, while significant, does not solve some of the remaining questions at the heart of the Mallory expedition—specifically, whether or not the men ever reached the top, and how, exactly, they died. Another inquiry left unanswered: whether their remains were originally discovered decades ago by Chinese climbers—and whether that discovery was kept secret.

“It’s a seminal find, for sure,” Hemmleb said. “But as far as solving the mysteries is concerned, I am doubtful this will tell us much.”

Questions That May Never Be Answered

Like Hemmleb, American climber and author Mark Synnott was shocked by the discovery of Irvine’s boot. Synnott, whose wrote a 2021 book The Third Pole: Mystery, Obsession, and Death on Mount Everest about Mallory and Irvine, said he awoke to a flurry of calls and text messages.

“It feels like another hugely important piece of the puzzle,” Synnott told Outside. “I feel like I’ve been waiting for a discovery like this.”

But Synnott echoed Hemmleb’s sentiment that the boot does little to answer the remaining questions that he and other historians have. In 2019, Synnott led a trip to the Chinese side of Everest. He brought aerial drones to scout the peak’s slopes, as well as GPS coordinates that suggested Mallory and Irvine’s final known location. He was hoping to locate Irvine’s body, and to find the pocket camera that the men were carrying, which could prove whether or not they reached the top. He came home empty-handed.

During his research, Synnott heard rumors that Chinese expeditions had come across a body high on the mountain’s flanks in the sixties and seventies, and that they had salvaged the camera and attempted to develop the film. After publishing his book, Synnott said he was contacted by a former U.S. State Department worker who told him that his wife, a former British diplomat, had heard directly from Chinese officials that early expeditions on Everest did locate the body of a foreigner dressed in 1920s climbing garb. Synnott wrote about the ordeal in the book’s postscript, and published a lengthy essay about the revelation on Salon.com

China has never acknowledged that its climbing teams found Irvine or Mallory. In 1960, a Chinese team led by Wang Fuzhou became the first to reach the summit via the Northeast ridge. Evidence that Mallory and Irvine reached the top would rob the Chinese of the first ascent of Everest’s north side, Synnott said.

“For me, this doesn’t change my theory that the Chinese found Irvine,” Synnott said. “There’s a lot of information out there—too much for people to just throw it away and say it’s not true.”

But not everyone agrees. British historian Mick Conefrey told Outside that the likeliest explanation is that Mallory and Irvine died in a fall while retreating from a storm, having never made it to the top. Over the years, their bodies were blown down the peak by winds or melting ice, and then deposited at lower elevations.

“I’ve never believed the theories involving the Chinese,” he said. “When there’s a vacuum, when something is unresolved, you can speculate about it.”

Earlier this year Conefrey published the book Fallen: George Mallory and the Tragic 1924 Everest Expedition, which is framed as a “myth-piercing study.” He examined documents and testimonies from the expedition, as well as news clippings afterward.

-

Read: Mick Conefrey’s How Does Mallory the Myth Compare to Mallory the Man?

Conefrey said that the myths and rumors about the two climbers began several months after news of their deaths on the peak. “Once the last eyewitness said they were going strong, the story became supercharged,” he said. “They didn’t just die in an accident—they were on their way to the top.”

But Conefrey argues that the 1999 discovery of Mallory’s body is proof that the climbers died well shy of the summit—and that they were simply taken down the peak by natural forces. He also referenced the diaries of one of the other expedition members, Edward “Teddy” Norton, for his opinion.

“Norton said he thought Mallory had turned back because he realized it was too dangerous—he was well aware of the dangers and wouldn’t have taken undue risks,” Conefrey said. “That was Norton’s assessment, and people seem to have forgotten about that.”

While the discovery of Irvine’s boot may not quell the disagreements, it does lay bare an element of the mystery. Nearly 100 years since they went missing, Irvine and Mallory continue to stoke the passion and interest of anyone who comes across their story. Hemmleb, Conefrey, and Synnott told me that’s not likely to change anytime soon.

“The spirit of these men and how passionate they were about pushing the boundaries of human potential,” Synnott said. “You can still feel that spirit of adventure in us, and trace it back to them.”

The post Sandy Irvine’s Remains Have Been Found on Everest. But the Mystery Endures. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Climbers like Adrian Ballinger and brands like Osprey have offered public support to two women who say Purja harassed and assaulted them in a recent ‘New York Times’ story. Others are moving cautiously.

The post Nims Purja Faces Sexual Assault Allegations. The Community Is Weighing In. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Leading figures in the worlds of international mountaineering and Nepali politics are weighing in on celebrity climber Nirmal “Nims” Purja in the wake of bombshell allegations of sexual assault and harassment.

On May 31, the New York Times published the accounts of two women who allege that Purja, 40, sexually harassed and assaulted them on separate occasions. In one account, Finnish climber Lotta Hinsta says Purja invited her into his Kathmandu hotel room, where it’s alleged that he proceeded to partially undress her and attempt to initiate sex, despite her repeatedly telling him no. Hintsa said Purja eventually relented and then masturbated next to her. She said the encounter occurred in 2023, during what was supposed to be a business meeting between the two.

In another account, California physician April Leonardo alleged that Purja made unwanted physical and verbal advances toward her during a 2022 expedition to climb 28,251-foot K2.

The public relations team for Purja, who rocketed to global fame in 2021 after the success of the Netflix documentary 14 Peaks: Nothing Is Impossible, denied the claims in a lengthy statement posted on Instagram.

“A story has been published making heinous allegations to which Nims unequivocally denies any wrongdoing,” the statement reads. “These allegations are defamatory and false.”

In the days following publication, however, a growing chorus of mountaineers, brands, and even Nepali politicians have praised the women featured in the Times piece and have called for action against Purja. Purja is one of the most prominent figures in Himalayan mountaineering, and his Elite Exped guiding company takes clients to Mount Everest and other high peaks around the world.

Rajendra Bajgain, a member of Nepal’s parliament representing the Gurkha constituency, sent a statement to Outside saying the Nepali government should launch an investigation into the new allegations.

“As a member of parliament in Nepal, it is very important that these investigations are taken seriously and pursued diligently, especially when involving someone as prominent as Nirmal Purja,” Bajgain said. “We owe it to our visitors and everyone in Nepal to ensure they feel safe and can trust our authorities. I will be advocating for such investigations because no one is above the law. Ensuring safety and trust in Nepalese law is essential for our country’s reputation and the continued success of our tourism industry.”

According to the Himalayan Times, Bajgain urged the Nepali congress on June 4 to ban Purja from entering Nepal. Purja lives in the United Kingdom.

In the days after the story was published, several female climbers weighed in, among them Alison Levine and Melissa Arnot Reid, who wrote that she had “been waiting for over a year for this story to break.” In a statement published on Instagram, Arnot Reid told her followers that they were safe to share their stories with her.

“The number of messages I have received from women today telling me their story is both crushing and activating,” she wrote.

Some Brands Stay with Purja, Others Depart

A lengthy conversation about the allegations sprang up in the comments section of a post published by guiding company AWE Expeditions, which is owned and operated by women. The original post stated that AWE was “deeply troubled by the reports of Nims perpetrating sexual violence against women in the mountains.” The post also named and tagged some of Purja’s sponsors, among them Red Bull, Scarpa, and Osprey Packs.

In the comments section, Osprey said it had cut ties with Purja. “Osprey is aware of the recent allegations made against mountaineer Nirmal Purja. He is no longer an Osprey ambassador,” the brand wrote. A brand representative confirmed the statement to Outside.

Outside also reached out to Scarpa and Red Bull regarding the allegations. Through a spokesperson, Red Bull said, “It is a matter for the public authorities to determine the facts concerning allegations against any person who has been accused.”

A Scarpa representative provided a statement to Outside saying the company was looking into the claims of sexual assault and harassment. “Scarpa takes these allegations—and any like them—extremely seriously,” the statement reads. “We are in the midst of an internal inquiry to determine our course of action.”

Some Say Allegations Are “Tip of the Iceberg”

The discourse on social media continued throughout the weekend and into Tuesday, June 4. American guide Adrian Ballinger, who recently climbed Mount Everest from the Tibet side, said on Instagram that he’s familiar with the hurdles that women have faced in the mountaineering community. “This week one of Everest’s biggest stars, Nirmal Purja, was credibly accused of sexual assault by multiple women,” Ballinger wrote.

“I’m deep enough in this world to have a pretty good sense of where the truth lies,” he continued. “It’s way past time for that truth to have its day. And it’s always time for women to know we want this playing field to be safe and equal for them like it is for us.”

Ballinger wasn’t the only mountaineer to share the story alongside a statement of support. American guide Garrett Madison and Austrian expedition operator Lukas Furtenbach both praised the story. Furtenbach called the allegations against Purja “credible” and condemned the behavior. British-Egyptian adventurer Omar Samra called the story the “tip of the iceberg.”

“So many women, some I know personally, have been living in fear of speaking the truth because the power structures are built to keep them quiet, while others work actively to silence them,” he wrote.

Catalan mountain runner Kilian Jornet referenced Hintsa’s “courageous denunciations” alongside a photo of the Times story, and referred to a “lawless feeling” in the high-altitude community. He said climbers have an obligation for “calling out aggression we experience or witness, and ensuring those in power, often men in roles such as guides and expedition leaders, create and maintain a safe space.”

Purja’s Response

On Wednesday, June 5, Purja published another denial on his Instagram page. In this statement, he said he had instructed his legal team to “move forward with the next steps in proceedings against the publication” in the wake of the Times report.

Outside reached out to Purja’s public relations representatives for comment on the public and sponsor reaction to the Times piece. His representative said the Osprey relationship deal ending amid the story’s publishing was coincidental.

“We had been in the process of reviewing the contract between us before any article, and due to refocusing on their business model, they decided not to renew,” a representative for Purja said.

Purja’s team provided Outside with a statement that Purja published on Instagram. The statement denied any allegations of any sexual abuse or harassment and said the Times story “was biased and had a pre-determined narrative and outcome.”

“While we understand women’s safety is an emotive topic and a hugely important one in all spaces—not just the outdoor industry—allegation, speculation and rumor should not be able to override the legal process,” the statement said. “For society to function it must be fair and unbiased. The legal presumption is innocent until proven guilty— the outcome should not be judged in the court of public opinion, or the arena of likes, shares and clickbait headlines.”

The post Nims Purja Faces Sexual Assault Allegations. The Community Is Weighing In. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Thundercat jammed, Diana Nyad hugged, Jimmy Chin autographed, and thousands of fans soaked up the stoke in Denver this past weekend

The post The Inaugural Outside Festival in Denver Rocked. Here’s What You Missed. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Diana Nyad was parched.

Could you blame her? She of marathon swimming and now red carpet fame had just delivered a rousing speech to a packed house at the Denver Art Museum this past Sunday, June 1, during the two-day Outside Festival. After the speech, Nyad stood under the midday Colorado sun in front of a long queue of autograph seekers, all clutching copies of her 2016 memoir Find a Way. Nyad spoke to each person, delivering wisdom about overcoming goggle tans or facing down fear, hugged them, and then signed the publication. But even marathon swimmers sometimes get thirsty.

And only one refreshment would do. “I need a snow cone!” Nyad barked.

The handful of us manning the autograph tent—editors, film producers, and advertising reps—looked at each other in confusion. Luckily for Nyad, snow cones were not far away. Chris Keyes, the general manager for Outside, and SKI editor-in-chief Sierra Shafer were making the icy treats at nearby booth. Moments later, a piña colada-flavored ball of shaved ice arrived for our guest of honor, who bit into it mid-soliloquy without missing a beat.

This scene played out on Sunday, the second day of the festival. I was there, and so were dozens of my Outside coworkers—we abandoned our day jobs of editing feature stories and selling advertisements to cosplay as event promoters. Look, I’m absolutely biased here, but the shindig we helped throw ruled. The inaugural Outside Festival had killer tunes, engaging outdoor films, celebrity book signings, dog stunts, bike stunts, food, and too many other events to list. Based on my extremely rough estimate, a billion zillion people showed up to dance and attend panel discussions and pet doggies, and everyone one of them was stoked. (No, this is not the official attendance count.)

My gig—half crowd management, half info kiosk—was a job that any journalist would have been proud to do. In between my duties—wrangling Nyad and author Kevin Fedarko, and pointing lots of sweaty people to the closest hydration station—I perused the festival grounds to check out the sights and sounds and mingle with guests.

I met a ton of friendly attendees, all of whom love the outdoors. They told me all sorts of anecdotes about their time at the festival. Here’s what I saw and heard:

Groovin’ and Movin’

Crowds funneled into the festival grounds Saturday evening just as the sun began to set. Lights illuminated Denver’s City and County building behind the main stage as some warmup music prompted everyone to get on their feet for the next act, Thundercat

In the crowd, Micah Gurard-Levin, 39, also rose. Gurard-Levin is a former pianist who now works the director of community impact for broadband communications company Liberty Global. He didn’t know Thundercat’s music but his friends did, and after a few opening bars of the first song, he got into the groove.

“It was this real avant-garde fusion of jazz and funk—a style I hadn’t heard in a while,” Gurard-Levin told me. “It was like music from an old-school eighties video game. Like, you’re about to fight the final boss and the music gets faster.”

Everyone was dancing as the skies darkened. Gurard-Levin looked at the crowd and noticed that the makeup had changed. Earlier in the day, he said, the attendees looked like hardcore outdoor enthusiasts. As the festival progressed, he said, the makeup evolved—younger and more diverse crowd added to the climbers, runners, and cyclists.

“That was the big macro picture for me—there was this intersection between different communities in the park,” he said. “And everyone was having fun.”

A Meeting to Remember

Talia Hoke, 45, sat in the crowd at the Sturm Pavilion and listened to three speakers share their stories during the “Journeys of Purpose” panel on Saturday afternoon. One of them, wildlife biologist Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant, caught Hoke’s attention. Dr. Wynn-Grant said the outdoor world felt alien to her growing up, because it appeared to be the playground for white men. Early in her career, she felt like an outsider in wildlife biology because of her background and the color of her skin. Hoke, a marriage and family therapist, had traveled to Denver from Philadelphia for the event. She sat in the crowd and nodded along.

“Just because you come from Black America doesn’t mean you shouldn’t have access to these places,” Hoke said. “It was empowering to hear that she had the tenacity to make it the center of her life.”

After the panel ended, Hoke beelined for the autograph tent. She purchased three copies of Dr. Wynn-Grant’s memoir, Wild Life, and then stood in line to meet her. When Dr. Wynn-Grant finally arrived, Hoke made the most of the experience: photos, conversation, hugs, and even tears. One book is for her mother, Hoke said, and the other is for her soon-to-be mother-in law.

Meeting Dr. Wynn-Grant was a highlight of the weekend, but so was walking around Civic Center Park and checking out the city. Hoke said that downtown Philadelphia lacks the access to outdoors that we take for granted in Colorado. And on her flight back home, she started checking out home prices in Denver. “You never know what the future holds,” she told me.

“I’m not a mountaineer or a backpacker,” she continued. “I walked away realizing the positive potential for how the outdoors can impact the people in my life.”

Winning a Golden Ticket

Jonah Grove is a huge fan of Diana Nyad.

When her employer, Price Waterhouse Cooper, told its employees that it had a limited number of tickets to the Outside Festival to give away, and that hopeful attendees should write an essay about why they wanted to go, Grove focused hers on Nyad. “She’s a great entertainer,” Grove told me. “Every time I hear her talk I’m reminded that she did her swim at age 64. That’s inspiring.”

Grove won the tickets, and placed Nyad’s talk atop her to-do list. But what else was there to do? Grove checked out the schedule and picked out a handful of other events to hit: a screening of the film Wade into Water, listening to author (and former Outside staffer) Katie Arnold discuss her new book, Running Home. Grove could check out the food trucks, climbing competitions, and of course the music.

I met Grove on Saturday when she buzzed by my booth and filled out an online form to win a pair of Columbia running shoes. A few hours later we did a random drawing and she was a big winner. “I’ve never won anything!” she said when she claimed her footwear. Then, on Sunday, she returned to the booth to meet Nyad and get a photo snapped with her hero. Guess who took the pic? Yours truly—yet another skill I got to apply to my festival job.

I asked Grove what she spoke to Nyad about. “I got up there and didn’t know what to say—I think I asked her about how her day was going,” Grove told me. “I was too excited.”

The post The Inaugural Outside Festival in Denver Rocked. Here’s What You Missed. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Famed mountaineer, filmmaker, and Everest pioneer David Breashears died on March 14. Those who knew him best share memories of the legendary alpinist.

The post “The Best Storyteller on the Planet.” Loved Ones Remember Everest Icon David Breashears. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

You can read the full tribute to Climbers We Lost in 2024 here.

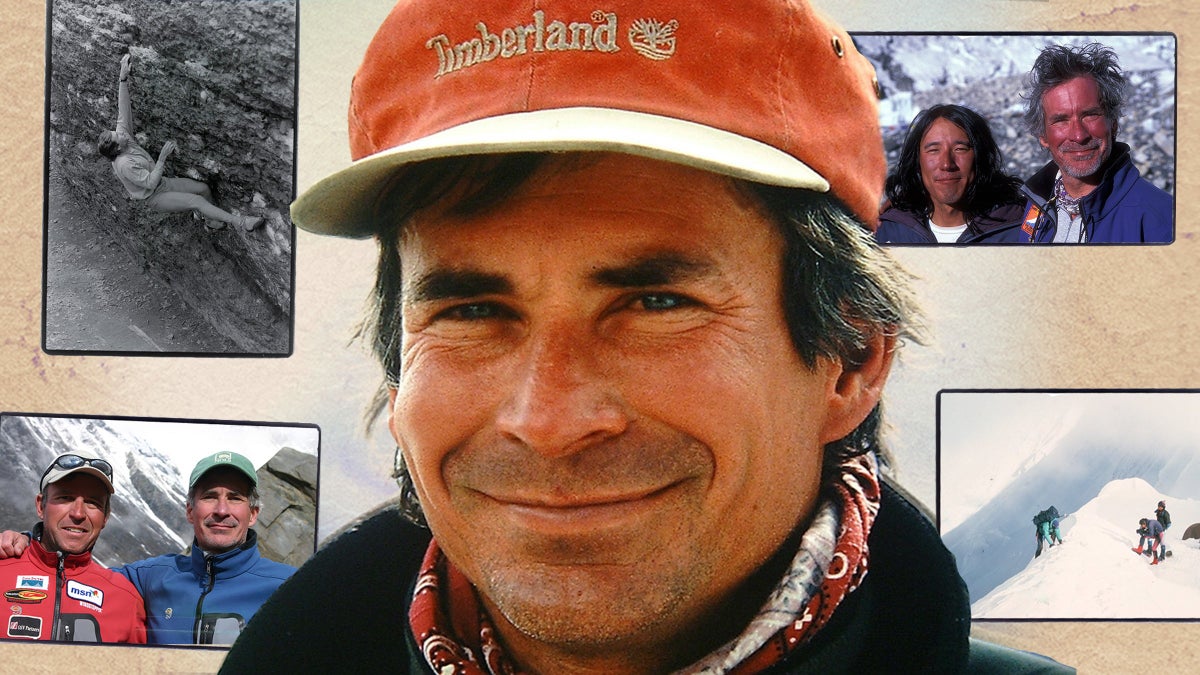

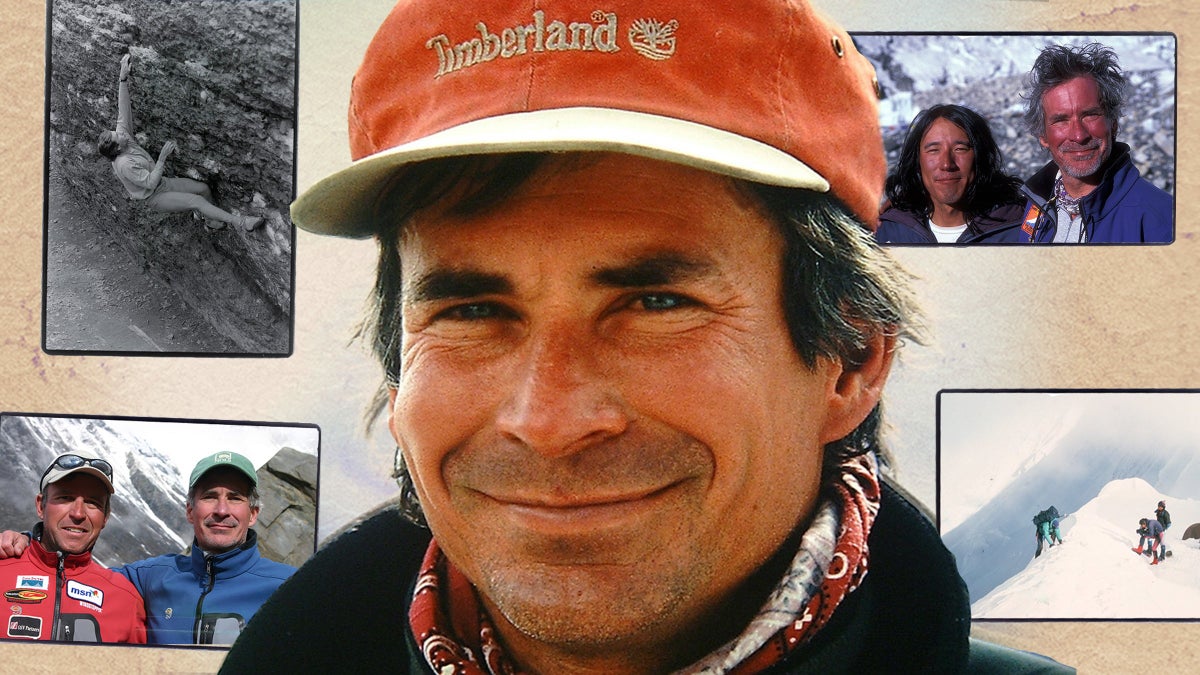

Outdoor enthusiasts lost a master of adventure storytelling earlier this month, when David Breashears died at age 68 at his home in Marblehead, Massachusetts. Breashears was a pioneer of filmmaking in the high mountains, and his documentaries about Mount Everest and the Himalayas brought millions of viewers up close to the famed peaks. His 1998 film, Everest, was the first to capture the world’s highest peak in ultra high-definition IMAX. And his 2008 film Storm Over Everest, which was produced by Frontline, took viewers inside the deadly 1996 disaster on Mount Everest.

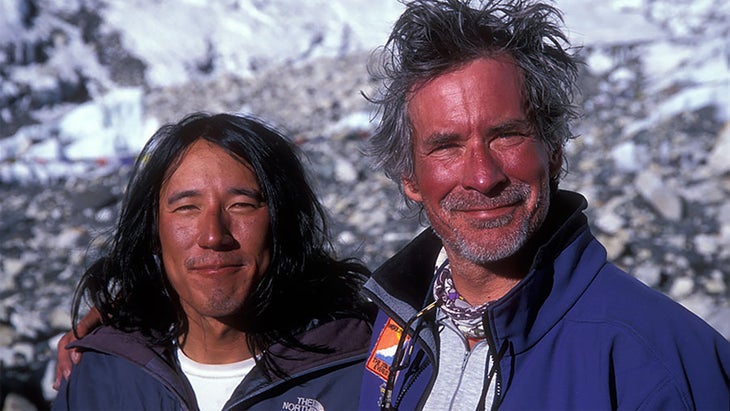

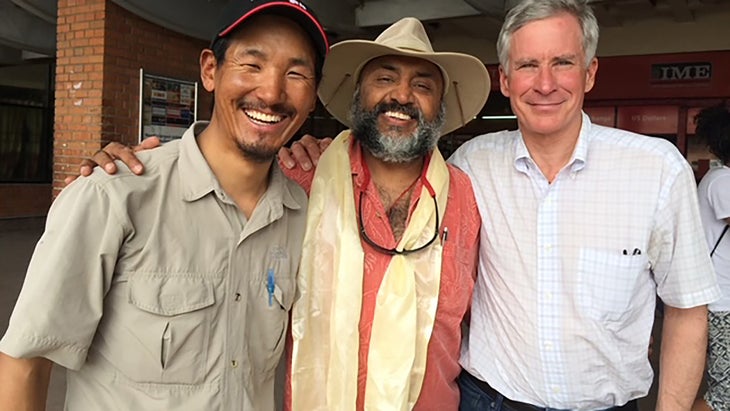

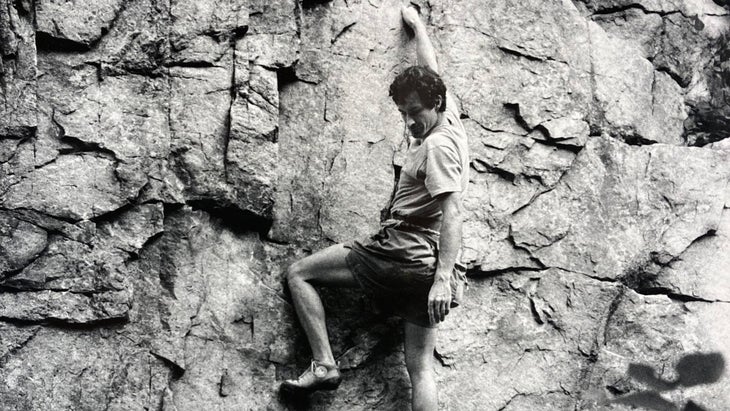

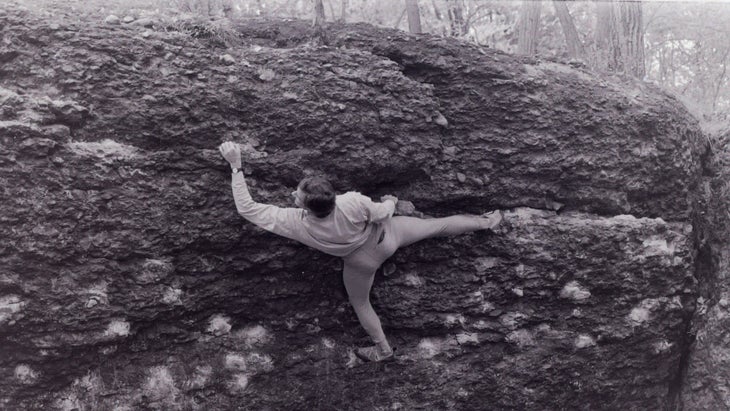

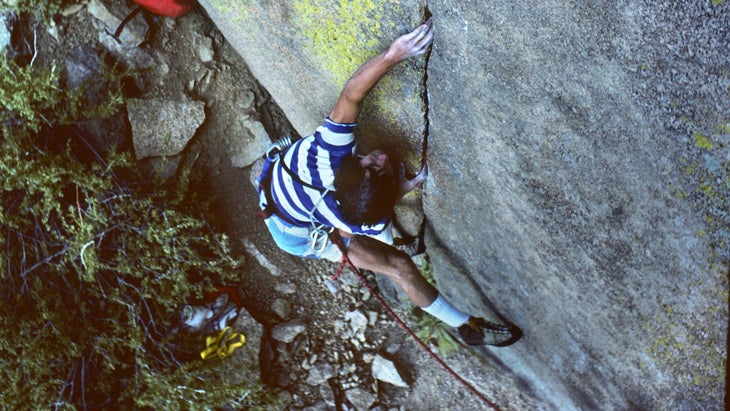

Breashears touched the lives of many through his work and his expeditions, and after his passing we compiled an outpouring of stories and memories from those who knew him best. Some of these tributes came from fellow mountaineers: Ed Viesturs, Sue Giller, Jimmy Chin, Ang Phula Sherpa, and others. Some came from rock climbers who watched Breashers excel on challenging routes in the seventies and eighties. Still other memories came from Breashears’ friends and family back home. Below, we have published these memories and photographs in full, to give you a sense of the man behind the many hard ascents, and the camera he hauled up high peaks.

He Set the Bar to 11

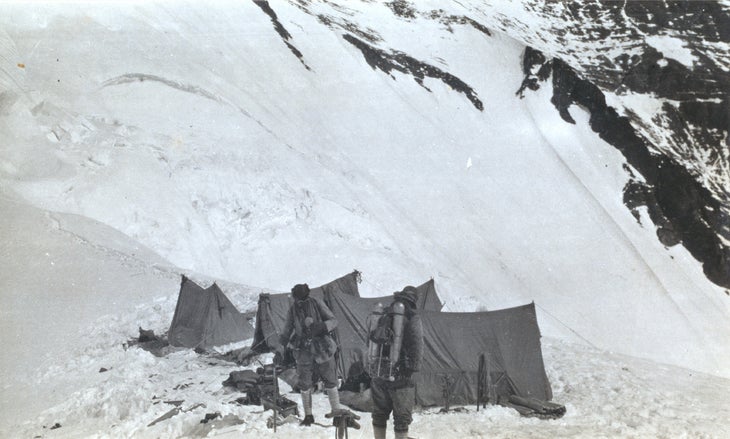

David Breashears was both a great friend as well as mentor. Early in my climbing career, in the late seventies and early eighties, as I read about mountaineering history and the current stars, I became aware of David. I admired him from afar and took note of his skills as a climber as well as his talent as cameraman and filmmaker. In 1987 we met coincidentally for the first time in the windswept, desolate Tibetan village of Xegar. We were both on our way to the north side of Everest. David to do some film work, while loosely attached to a Norwegian team, and me on my very first Himalayan expedition as part of a small American team led by Eric Simonson.

Years later, in 1996, after I had by then been to Everest seven times, David invited me to lead the Everest IMAX filming expedition. He would be focused on being the lead cameraman and director of the film. It was a monumental task, which in my opinion, not many people were capable of, nor had the skill set to achieve. Those were the types of challenges that David embraced and excelled at accomplishing. It was during that project that I witnessed his amazing work ethic, meticulous attention to detail, and his striving for perfection. He said to me “If my name is associated with something, it has to be done right.” His leadership inspired me and elevated me to go to another level. The IMAX expedition was the single-most challenging expedition of my career. I thanked him for including me on that journey. We partnered again on Everest for two other film projects in 1997 and 2004, standing together twice again on Everest’s summit.

Coming full circle, after having met him on my very first Himalayan expedition in 1987, he made an effort to join me in 2005, 18 years later, at Annapurna base camp, just days before I climbed to the summit—my last of the 14 8,000-meter peaks. We had a spell of bad weather, and before we made our final ascent, David had to leave for home. He asked us to keep him informed via sattelite phone as we made our way up. Veikka Gustafsson (my climbing partner of ten years) and I finally made our push. Climbing alpine style, we arrived at our second and highest camp, within two days, hoping to go for the summit on the third day. There we got trapped by a windstorm which held us there for two full days. Not wanting to descend, but not knowing how long we could hold out, we were truly tested. I chatted with David from this battered camp, on the sat phone during this time, and he encouraged us to hang in there and be patient. His positivity, along with the strength of my wife, family and friends, gave me the strength to wait it out. His presence was powerful.

He was always a man that I looked up to and I strove to emulate his level of attention to detail and planning. He set the bar to 11. He will be missed. —Ed Viesturs, American mountaineer

He Gave Me My First Big Break

I very much tried to follow in the footsteps of David, and in a way he gave me my very first break in the industry. Conrad Anker and Rick Ridgeway were leading a National Geographic expedition to the Chang Tang Plateau, and I filled in for David’s after he had to leave the expedition due to other obligations. I was very new. Rick told me to just commit to the shot and figure it out, and he mentored me on that trip. After that trip, David spoke with Rick and Conrad about how things went, and he then reached out to me. He needed someone to film on Everest in 2004 and apparently I had gotten favorable reviews. David brought me on the trip and it had a huge impact on me.

I got to see how David ran a large-scale Everest production, and how he approached filming in the mountains and climbing high peaks with a production crew. It was invaluable because I got to see how it was done correctly, and it accelerated my own growth as a filmmaker in the mountains. I saw how every detail counts: the gear, team, timing. I also saw how, with David, there was focus when there needed to be focus, but he was also a real jokester who made time for fun. He took me under his wing and I feel incredibly fortunate. And I’ve tried hard to live up to those expectations and standards. Because he pushed me to work harder and go farther than I would have on my own. —Jimmy Chin, American mountaineer and filmmaker

The Kloeberdanz Kid

I first knew Dave as the skinny young Kloeberdanz Kid from his Boulder days in the seventies. But I really came to know him better on our shared Himalayan expeditions: 1981 East Face of Everest and 1986 North Ridge Everest via Tibet. He was just learning his filming craft on the 1981 trip, where he was supposed to be the sound gaffer for Kurt Diemberger. But Dave was the only member of the film crew who could do the technical climbing, and thus became the camera operator too. On the 1986 expedition, Dave was running the whole show (producing and filming). While Dave could be extremely focused on his work, he always took time to be very supportive of me in my climbing career. He was a caring person. I always looked forward to catching up with his life at American Alpine Club meetings. Alas, that is no longer an option. —Sue Giller, American climber

His Social Work Will Remain Immortal

In October 1998 I had the opportunity to meet David Breashears at the house of my uncle, Wongchhu Sherpa, in Kathmandu. I was probably ten years old at the time. David and my uncle were very close friends, and I felt that the relationship between them was like brothers. David’s work in tourism and expeditions were done through my uncle’s company. In the year 2000 I started working as a porter on treks operated by David, and in the following years I got to work various roles in Everest expeditions, eventually attaining the job of climbing sherpa. For my first climb up Everest I had the opportunity to climb with David, and I had the opportunity to learn mountain climbing, photography, and filmmaking from him. I got the opportunity to work together on 44 different projects, and I worked with David 1,251 combined days over the years. He used to treat me like his son and give me inspiration by teaching me my work.

In 2015 the great earthquake hit Nepal, and on that day David and I were climbing Mount Everest. We had moved from Base Camp and reached Camp 1. We were in no position to do anything but watch helplessly and save our own lives. After that incident, David was traumatized from the inside, and began to worry about what can be done. One day he told me he wanted to stop climbing and study the effects of climate change on the mountains, and do work associated with it.

David has always been providing financial benefits to Nepalis through various means, and his social work will always remain immortal. When he came to Nepal, he did lots of work in my village, Tapting, in Solu Khumbu. In collaboration with my uncle, he helped in healthcare, education, hydropower, drinking water, and other public works.

In my 18 years working with David I had the opportunity to get to now the world. Sometimes we laughed together, sometimes we cried together, and sometimes we rejoiced together, and sometimes we were scared together. By loving me like his own son, I have given him the position of a religious father. Because of that I got a chance to act in his Everest movie and even step on the red carpet at a Hollywood premier. I am probably the first Nepali to walk on the Hollywood red carpet! —Ang Phula Sherpa, Nepali mountaineer and guide

A Brother I’ll Always Remember

Being the youngest of four siblings, only two years apart, David and I were a close pair growing up. His personality, marked by tenacity, determination, and a love of nature, was evident from a young age. I remember watching him tie hundreds of knots for his Boy Scouts certificate, which I was assigned to supervise by our mom. Once he set his mind to executing a task, there was no stopping him. When something piqued his interest he would learn everything he could about it, and often he’d rattle all the facts off to me.

Climbing was his ultimate goal, and once he discovered that passion he was set on doing it every second he could. In high school he dropped our mom off at work every day with the assumption that he’d take her car to class, but instead he would head straight to Boulder to climb all day before using a drill to reverse the mileage on the car and returning to Denver.

David was prepared enough for Everest by the time he climbed it that my biggest fear was him sleepwalking off a cliff. He sleepwalked enough as a child that when we went to summer camp I tied our wrists together with string when we went to sleep in our tent (and though he was still there in the morning, the string had mysteriously been untied). When I told him about my concern he just laughed and told me that wouldn’t happen. I wasn’t worried about the rest because David had prepared so carefully and intentionally for the climb, as he always did.

David valued the community he built around mountaineering as much as any other aspect of the climb. He built so many lasting friendships on unwavering trust and a commitment to keeping each other safe in dangerous conditions. He also respected nature and was deeply concerned about the fate of our planet. He was as passionate about the climate crisis as he was about anything else, founding GlacierWorks in 2007 dedicated to raising awareness about climate change. Though he is primarily remembered for mountaineering and filming, I know he would want his legacy to be this activism.

I’ll miss my brother’s voice saying “Hey sister” when he picked up the phone, and hearing all about his latest interests. This will be the first year without a dozen roses from David on Valentine’s Day, plus a dozen more on my birthday and the inevitable comment that, for the next two months, we were just a year apart.—Lisa Breashears, younger sister

My Unofficial Uncle

I’ve known David my entire life—he was the unofficial uncle in my family, and had known my mom since she was in her twenties. By the time I came around he was a big figure in our family, and an extremely close friend. He’d come over for dinners, sometimes appearing out of thin air in an unplanned way. He’d come back from an Everest expedition, sit in our living room, and tell his stories in such a way that captivated everyone. There was a sense of mystery about him.

So when I was 12 David was putting together an expedition to Killimajaro, and lo and behold he wanted to have a female child to participate. He approached my parents about me going and spoke to me about it. We had traveled before but never done a multi-day expedition to high altitude. My father came along on the trip and it was challenging because we were filming with IMAX cameras. He was directing so many people and in charge of everything, but he still found a way to have that uncle feeling with me. He made me feel safe and protected and encouraged me every day.

One day, we were heading up the mountain and I was having a hard time because my feet were so cold. David could see that I was uncomfortable and embarrassed. He stopped everyone on the trail, told me to take off my backpack and boots, and then proceeded to place my bare feet up under his jacket onto his warm bare stomach. It worked. It didn’t matter that we were chasing the sun for the perfect shot that day. In that moment, taking care of me mattered most. —Nicole Wineland-Thomson, neighbor and family friend

A Colleague, Close Friend, and Neighbor

David appeared at my office doorway one day and in a way never left. He wanted to talk about Tibet. On a recent trip to Lhasa he’d secretly interviewed, on video, young Tibetan activists, wanting to fight the Chinese occupation. Not only that, he’d ridden his bicycle into the countryside, scaled a nearby mountain and filmed the prison camp. What could he do with his footage? We went to lunch.

He would become a colleague, a close friend, and our neighbor round the corner. He was a great companion, curious and opinionated. Fearless and precise. He calculated risks and took action. That’s how I found myself in the back of a truck, climbing a 17,000 foot pass from Nepal into Tibet with David and my friend the journalist Orville Schell, posing as tourists with a home video camera, trying to take the measure of the Chinese occupation. Orville and I were completely dependent on David’s judgment and decisions for the next ten days; maneuvering into monasteries, meeting monks who were contemplating taking up the gun, and finally making it out by air from Lhasa. The film went out on Frontline, and our lives were linked.

One day in the mid-90s I was talking to Greg McGillivray in Laguna Beach, after we’d finished some editing work together. He said in passing he wanted to make a film about Everest. I told him I thought the one person who could get an IMAX camera to the summit was David Breashears. He’d never heard of him, but wanted his phone number. I asked David to take his call. The IMAX film made history, in part because of the awful conjunction of a deadly storm and a crowded mountain, but also that David, after saving lives and sharing supplies, rallied his team and delivered on what he’d promised to do: put the camera on the summit.

David was proud of the film, but didn’t think the IMAX format gave enough time to the complicated tragedy and its human failings. Using his own money he traveled around the world and interviewed as many key survivors as he could, fellow climbers who opened up to him. It was typical David: obsessive and daring, financing his own convictions, convinced that he could get a film made somehow. He took the upfront risk and it paid off: it was broadcast on Frontline — “Storm over Everest” — I think the best account of the tragedy.

At home in Marblehead, David would appear on our porch, discuss menus and argue the particulars. He was part of our family. We’d go fishing for striped bass and I’d drop over to watch him lay out piles of gear and cameras, meticulously from room to room, planning the next expedition and the logistics of what would pack where and what belonged with yak or Sherpa.

In 2008 our Frontline team asked him to go to “The Third Pole”—Everest—for a film about global warming. The producer Martin Smith drove with him to the base of the Rongbuk Glacier on the north side. Marty told me how David politely but firmly suggested that he and a Sherpa would move more quickly without him. They rolled up their pants, forded an icy river and took off. David had identified the actual spur where George Mallory had taken an iconic photograph of the glacier and the mountain in 1921. David framed an exact replica of the image, in order to dissolve one over the other, showing the massive loss of ice over the past century.

He later said that sequence in the film was an inspiration for GlacierWorks, the collection of massive photographs he made across the Himalayas to call attention to global warming. They represent a series of expeditions that were once again David taking the financial risk, convinced that his work was important and would be a contribution to the world. Today, an exhibition of those photographs, called COAL+ICE, is at the Asia Society in New York. It’s been on show around the world since 2011.

Setting off on the first of those expeditions, he told me not to worry. It would just be David, two sherpas, and a couple of yak herders.

I like to think he’s there now, in his beloved mountains. —David Fanning, founder and executive producer (1983-2015) of Frontline

He Supported Sherpa Families

I am very sad at David’s untimely passing. We will miss him so deeply. His legacy, friendship, mentorship will be forever remembered. He was my boss, friend, mentor. I met David the first time in 1996 at Everest base camp while he was leading the Everest IMAX Expedition. I came to know him through my brother in-law Jangbu Sherpa (who carried the Everest IMAX camera to the top of Mount Everest). In 1997 I worked as a Base Camp kitchen boy for his Storm Over Everest expedition.

During my early climbing career in 2004 I got opportunities to work with his filming expeditions, and I summited Mount Everest for the first time with him and his team. Afterward David gave me other opportunities to work with his GlacierWorks photographic expedition as head photographic assistant for many years in Nepal, Tibet, China, and the Karakoram in Pakistan until 2012, when I was employed by Peak Promotion in Nepal. I was so grateful to work with him for a great cause. During the many expeditions he always talked about our families and future.

David was so influential in my life. He was always worried about me and our families’ future in Nepal because of political instability. He often told me to have our kids focus on math, science, and English at school. I told my kids the same words that David said. Over time my son graduated in mechanical engineering in the United States. David and another good friend, Dick Morse, invited me to visit the United States multiple times.

By 2012 I climbed Everest four times and survived multiple close calls in the mountains. Over the years I became a permanent resident in the United States. I was able to bring my family for a better education/future for my kids. David supported me and many other sherpas families’ for better futures. I will be forever grateful to him. —Mingmar Sherpa, Nepali mountaineer and guide

Most of Us Struggled to Keep Up

David always reminded me of a whippet—lean and fast and moving at a pace most of us struggled to keep up with. His mind moved as quickly as his body, and he was always chasing down something in books or conversation he wanted to understand. He set the bar high—for himself and everyone around him—and whether developing a new filming technique at altitude, finding the perfect words or images to tell a story, or mastering a new pasta recipe, David was an indefatigable force of nature in all things he took on.

David is well recognized for his remarkable accomplishments as a climber, filmmaker, author, and climate activist. But he was also an extraordinarily kind and generous human being and a friend to many. My family was deeply moved but not surprised that David jumped on a train in Germany, grabbed a flight from Paris, and drove through the night from Boston to make sure he could be with my husband (and David’s partner in Arcturus Motion Pictures), Andy, one of his closest friends, in Andy’s final hours. You can be sure there are many families in Nepal who have stories of their own to tell about the decades of friendship they shared with David.

As in life, David moved on quickly, too early and too soon. We were lucky to have shared some of his magic. —Kathy Harvard, vice president of Inner Asia Rugs

The Story of Perilous Journey

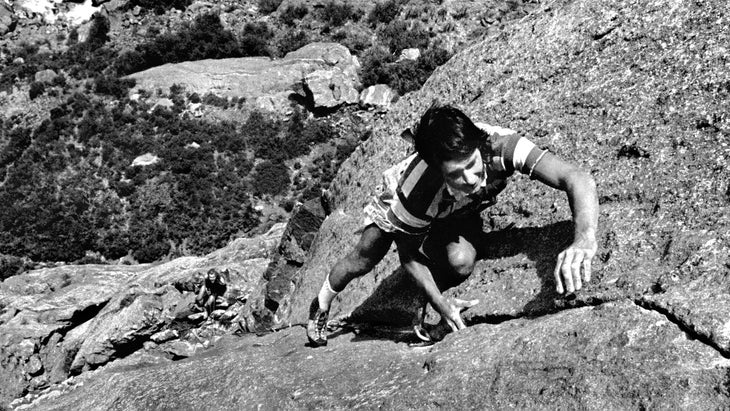

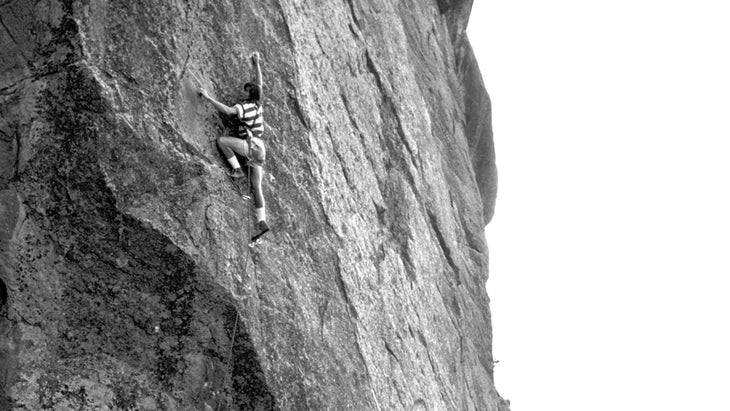

Climbing with David Breashears in the early to mid-seventies was a great time of adventure and camaraderie. We considered ourselves a climbing team, as our chemistry worked well together. By the summer of 1975 Dave was 19 and ready to make his mark on the climbing world. We had been eyeing a blank face on a cliff above Eldorado Canyon called Mickey Mouse. Dave’s intent was to try the blankest route up that face. We climbed in the style of the times, which was ground-up ascents with no bolts. We were disciples of the clean-climbing movement. Hiking up that morning I had no idea something truly amazing was going to happen that day.

We got to the wall and started bouldering up the route a ways. At some point we decided this is it and roped up. We traded attempts and realized there would be no reversing the first crux. Dave made it past the first crux with no protection available. Standing precariously on a sloping foothold, he was calm and in control as he looked up at what lay ahead of him. Both hands dropped to his side as he shook them out and yelled down to ask me which way looked good. I yelled back, “The left looks promising!”

In my mind all I can see, still, is the second crux. It looked more difficult than the first. At this point Dave was 40 feet up, the second crux at 50 feet.

Dave started up a few moves on poor holds and unobvious moves. He peered up and out and downclimbed back to the rest. I offered encouragement, saying “You look solid, you got this.” I knew he was going up, not down. He tried it again, but backed down to the rest.

He looked down at me and said, “I’m going this time.”

“You’ve got this!”

I had 100 percent confidence in Dave. After a quick shake out he went at it again; having figured the sequence out, he looked solid on it. He pushed through the second crux, running the rope out to the belay. He did the whole route, something like 100 feet, without pro.

Once set up, he called, “On belay” and, “Don’t fall, we want a clean ascent.” He always considered it a team effort but I knew the genius was in his mastery of the route. I was really sketchy on the moves but able to finish without a fall, and upon reaching Dave told him what an incredible piece of climbing he had just accomplished. I knew what I had witnessed. I believe the route, called “Perilous Journey,” changed everything for Dave. He took climbing a step into the future that day, a future where all things were possible for him. —Steve Mammen, American climber

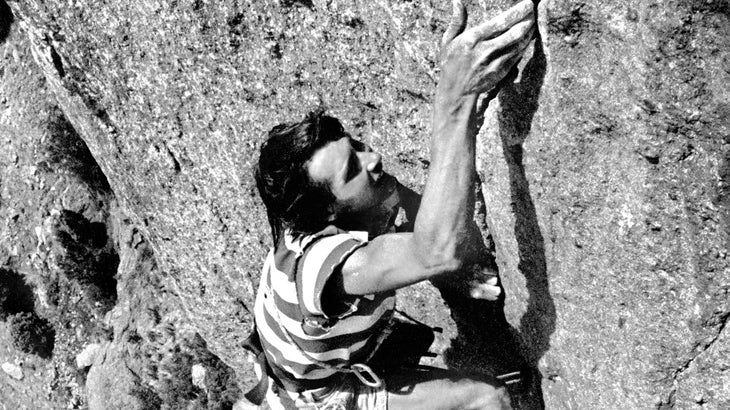

The Master of Control

I met Dave back in the seventies, when I was in high school. Much of my climbing at the time was bouldering at Horsetooth Reservoir outside Fort Collins, Colorado, and roped climbing in Eldorado Canyon. One of my main partners was Steve Mammen from Denver, and I met Dave through him. Both Steve and Dave were a couple years my senior and both were in their climbing primes. Dave would frequently come up to boulder at Horsetooth, and he was gracious enough to let me tag along.

Climbing during this time was vastly different than much of climbing today. Being in control was key. Falling was usually not an option but a last resort. The ability to escape from a situation both in rock climbing and high bouldering, and the art of down climbing, were essential. Gear was much less sophisticated as well: nuts were just coming onto the market, and there were no camming devices; there were also very few harness options. Most climbers opted for a “Swami Belt,” a length of two-inch nylon webbing wrapped around the waist and finished with a water knot. There was incentive enough not to fall. There were no bouldering pads. High boulder problems required the same control and ability to escape as rock climbs did. Footwear was another huge difference. Sticky rubber was still years down the road. Shoes at the time were stiff, with hard rubber. Precise footwork was critical and required full awareness of placement.

It was with this gear and in this style of climbing that Dave excelled. He was a master of down climbing and climbing in control. He would spend hours going up and down sections, gaining the confidence to finally push through. He had laser accuracy with his Vasque Ascender boots, the “Shoenards.” He rarely, if ever, fell.

I ran into Dave a number of times later in life. He was always smiling, asking about his friend Steve and wanting to make plans to go bouldering together. I was very lucky to be able to spend time with Dave, a true master and legend, on the rocks. —Mark Wilford, American climber

He Adopted Us

David came into our lives in his teens. He found my wife, Pamela, and me amongst the tribe of seventies climbers in Eldorado Springs Canyon. We were five years older, in possession of an Eldo shack and a dog, and we adopted David, except that he adopted us.

Our friendship endured for 52 years, enough time to feel certain of who he was. David’s wry, discerning smile, rock-solid loyalty to friends, and somber intensity accompanied us around the world. There he was, quietly observing the lunacy of guiding David Lee Roth up Lobuje in Nepal, diligently filming the excavation of Incan sacrificial mummies in Peru, tearing up as we guided a group of mentally disabled teens up Kilimanjaro.

David was complex: he embodied emotional range from giddy and goofy to dark and brooding. All those many facets were bound together by an abiding love for the natural world, deep empathy for others, and the capacity for rich, meaningful friendships. We loved David and will now depend upon the memories of shared time together. —Mike Weis, American climber and filmmaker

A Passion for Literature and Learning

In 1983 David Breashears, Kim Momb, and I were the youngsters on a star-studded American expedition attempting to make the first ascent of the east face of Mount Everest. I had followed a more traditional academic path and was on leave from medical school. David and Kim were full-time climbers since high school.

As a young rock fanatic in the seventies I had been, of course, aware of David Breashears. His bold ascents in Eldorado Canyon were legendary. I looked forward to hanging out with David and talking about climbing. However, he just wanted to discuss books. He chided and derided me for wasting time and money on an Ivy League education. His expedition duffle was heavy with issues of The New Yorker and books by Carl Sagan, Richard Feynmann, Camus, and Kant. He had a small notepad for writing down every word he did not know. David looked each one up in a dictionary and inserted that word into several sentences over the next few days. Over time he became my most articulate and best-educated climbing partner.

David was always full immersion and all in. He moved to Boston while I was still in medical school. We became frequent climbing partners. What I savor, looking back, were the conversations around the dinner table or in the car driving to New Hampshire much more than climbing the Black Dike on Cannon Cliff in full conditions.

When David began his work in film, he read constantly and studied every angle of the art. He was the ultimate craftsman, pushing himself to be his very best in every pursuit. When I moved to Utah, he came out a few weeks every year to ski with me and spend time with his friend Dick Bass. Each visit he was mastering something new, from glaciers and water geology to molecular gastronomy. He became a great chef and delighted in cooking meals at our home and teaching my daughters the tricks to making perfect homemade pasta.

David Breashears was a groundbreaking climber and cinematographer, a chronicler of the recession of Himalayan glaciers, a superb lecturer inspiring both youth and corporations; but most important, a friend to many and a man who lived a life with intensity and passion. —Dr. Geoff Tabin, co-founder and chair, the Himalayan Cataract Project

The Coolest Uncle

I’ve often thought about how excited other people—like Outside’s readership—would be to have David as an uncle, and that his penchant for adventure was wasted on me, an indoor type of girl. He once offered to climb Mount Kilimanjaro with me, and I asked (as a joke… kind of) if there was a book about it I could just read instead. Still, David applied his adventurous intensity to everything, so I got to see it throughout my life.

I first realized he was a big deal at the premiere of the Everest documentary, when I was three. David introduced the film and pointed us out in the crowd. I remember holding my breath during the scene where he made his way slowly over a chasm on a shaky metal ladder, it was the most frightening thing I’d ever seen.

He was a well of information about all things outdoors. After years of packing as light as possible he could pick up anything and tell you its exact weight, something I made him do incessantly over Christmas when he stayed with us in Denver. Though I spend most my time in archives and libraries now, thanks to David I know how to increase my chances of surviving an avalanche, how to stay alive in the face of hypothermic exposure, and how to prepare for impaired thinking from oxygen deficiency. He told me I couldn’t be scared, that fear distorted the mind’s ability to make good decisions, and the best way to combat fear was preparation. I couldn’t believe he hadn’t been scared walking across that ladder on Everest.

Since he couldn’t get me out on the mountain, David settled for launching an expedition on my terms. The year I planned to apply to PhD programs, David suggested I drive down to Massachusetts, and we’d visit some campuses on my list. By the time I arrived he was well-prepared: he knew the size of the school, the cost of living, and a myriad of other details. That was one of the most fun things about him, if he knew you were interested in something, he’d make a point to obsess along with you. After our trek he made me scallops and we discussed what I liked, what I didn’t, and what other factors I might need to consider. That was David about everything he encountered: he was intense, passionate, analytical, practical, and ready to get things done. I showed him Chef’s Table that evening since cooking was another of his passions. He toggled between talking about the documentary style and the chefs’ approaches to food. He texted me later to tell me he binged the whole show.

That same trip, David took me out on Marblehead’s Bay in a little boat, talking the whole time about how the boat worked, his safety concerns, how to read the compass, what to do in foggy weather or choppy waters. I just wanted to get in the ocean. We were out by a red bobbing buoy that evoked the opening scene of Jaws, which terrified both David and my mom when they saw it as kids. Once I jumped in David wanted me back on the boat almost immediately. I was too excited about my chance to be in the ocean, though, so I stayed.

“Ok Caroline, you have to come in now, your mom would kill me if a shark got you,” he said after a while.

“You climbed Everest, I can’t believe you’re scared of your little sister!” I teased.

Later, I realized I hadn’t been afraid because I was with David, who was exactly the person you’d want by your side at the first sign of danger. He respected nature and he knew it was far more powerful than him. Preparedness and knowledge made David very nearly fearless, with the small exception of those forces he stood no chance against, like the shark from Jaws and little sisters. —Caroline Johnston, niece

Bouldering in Boston

The first time I met David I almost felt sorry for him. It was fall of 1985, and the little bouldering area of the Alcove, a 12- or 15-foot protrusion outside of Boston, was busy. People were bedecked in a riot of Lycra, and he walked up amid the movement and commotion wearing a polo shirt, jeans, and a quizzical smile. Maybe he was a newbie, I thought; the scene might be intimidating. I tried to smile kindly. I had just moved to the area, and it was my first time at the Alcove.

Boom! Pinch grips on the cobbles of the dark, steep conglomerate. Powerful but smooth, static cranks from pocket to pocket, as we others dynoed and splatted. My friend said quietly, “I think that’s Dave Breashears.”

David was there with his dear friend and neighbor Jeff Brewer, and meeting them was one of the best things that happened in my time in Boston. I often bouldered with them and our mutual friend Dave Rose. David was often away in the Himalaya, but he’d come back and start rock climbing again. He is known to the greater world for his mountaineering, from what I think of as “Everest everything” to the huge hard ice face up Kwangde Lho, and to climbers as a superb technical talent. The hard and committing Perilous Journey and Krystal Klyr, famed 5.11s in Eldorado, near Boulder. The Breashears Crack, 5.12, on Cynical Pinnacle, the South Platte.

I thought of David as accomplished, artistic, and technologically expert (“expert” surely doesn’t touch it), but also principled and strict with himself. He stopped his own filming and offered help and all his resources immediately during the Everest 1996 tragedy because it was the right thing. On expeditions his motto was attention to detail.

We last spoke two years ago, when I called for an article on Sibleyville, the classic climber compound in Boulder where he had been taken in as a teen, and which had just burned down in the Marshall Fire. David (Jeff Brewer always called his pal The Great Man, though without letting on) was always busy, but he ruminated at length about how welcoming Paul Sibley and cohorts had been to him as a kid—“The Kid.”

We’d both left Boston long ago, and it was a nice day here in Western Colorado and at his place in Marblehead. He sat out on his deck, looking at the water, and I went upstairs from my basement office to, well, a parking lot, but in spring sunshine. We talked about his non-profit GlacierWorks project, to bring science, art, and mountaineering to the battle against climate change. In 2018, I’d seen his presentation at Telluride MountainFilm, on comparative studies of glaciers over the years. He showed archival photos, “wiping” them over with his, made with systems that created amazing details—he zoomed in on just one rock. David had the skill and meticulousness to use such equipment, and the mountain experience to ascend thousands of feet and set up a camera in exactly the right place. He educated so many, and still had so much to do. —Alison Osius, senior editor Outside and former editor Rock and Ice

Wet and Cold, No Problem

David was wet and cold, yet enthusiastic. His back to the relentless wind, in single-digit temperatures, he regarded the vista before him. Not the mountains surrounding Everest, but duck decoys rocking in the icy Connecticut River of New Hampshire, maybe 500 feet above sea level.