The Boulder local and her French partner simul-climbed the five-pitch route “bridge to bridge” in 37 minutes 8 seconds, shaving 32 seconds from the previous record.

The post Kelleghan and Pineau Set New Women’s Speed Record on the Naked Edge appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

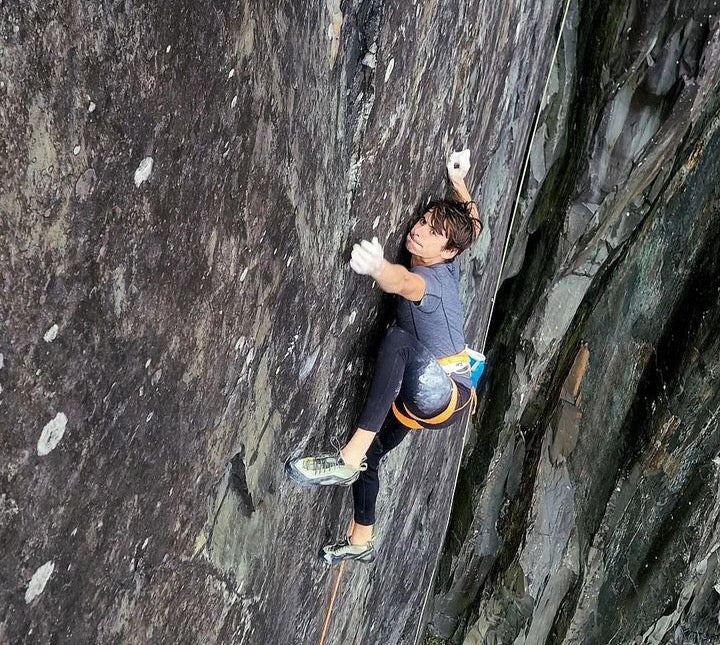

On Friday, March 28th, Kate Kelleghan, a 31-year-old climber from Boulder, Colorado, and Laura Pineau, a 24-year-old climber from Toulon, France, set the women’s speed record on the Naked Edge (5.11b) in Eldorado Canyon, Colorado. The pair climbed the five-pitch route “bridge to bridge” in 37 minutes 8 seconds, shaving 32 seconds from the previous record, set in 2021 by Kelleghan and Becca Droz, of 37 minutes 40 seconds.

Racing the Edge

After a morning warm-up lap on the route, Kelleghan and Pineau started their clock and raced across the bridge over South Boulder Creek. Sprinting toward the Red Garden Wall, they soloed ~200 feet of 5.8, the lower pitches of Anthill Direct, and reached the start of the Naked Edge in approximately 9 minutes.

From there, Pineau rested for two minutes and belayed the more experienced Kelleghan, who led the route. Kelleghan jammed up the first pitch, a 5.11a finger crack, and continued up the 5.10b arête second pitch. As she neared the second pitch anchor, Pineau began climbing at the end of their 25-meter rope. Kelleghan cruised through the 5.8+ moderate cracks of the third pitch, and then launched up the 5.11b bomb-bay chimney to layback boulder problem to steep hand crack. As Kelleghan finished up the 5.6 crack at the top, Pineau climbed behind her on a terrain belay, racing up the route in approximately 21 minutes as Kelleghan began walking down, still tied in.

The pair protected the simul-climbing with three micro-tractions, allowing Pineau to potentially fall without Kelleghan feeling her weight. After having climbed the route 75 times, Kelleghan knew where Pineau would be while the pair simul-climbed and kept a few pieces between them. Kelleghan, who took most of the risk of the ascent, placed nine cams and clipped nine pieces of fixed protection, including bolts, pitons, and fixed stoppers.

When they reached the summit, Pineau untied and the pair blitzed down the East Slabs, which included some 5.0 moves, in around seven minutes.

Kelleghan and Pineau knew the previous record was 37:40. After a broken shoelace slowed them, they worried that they’d lost precious time.

They were right. By the time both climbers had touched the center of the bridge—the unofficial finish line—their watch read 37:50, 10 seconds too late.

A Dream Team

Kelleghan, an avid speed climber and former Yosemite Search and Rescue member, had been searching for a female speed partner for years before she finally met Pineau over social media in 2024. That October, Pineau made a notable ascent of Greenspit (5.13d/14a), a 15-meter trad route in Valle dell’Orco, Italy. She had only started trad climbing two years prior.

Kelleghan pitched speed climbing and Pineau, fresh from her successful roof project, traveled to Yosemite in late October, where the pair climbed a day on the Nose. Then, this past winter, Kelleghan headed to Toulon, where they tackled a few multipitch routes in Destel and practiced thirty pitches of simul-climbing. Their first big goal as partners would be in March, when the athletes would test their speed on Kelleghan’s hometown racetrack, the Naked Edge.

“I’m teaching Laura to speed climb, and this was a perfect milestone,” said Kelleghan. As soon as Pineau got to Colorado, she climbed the Naked Edge with local Matt Reeser, who cruised up the pitches and placed little gear. The thought of speed climbing on the route initially terrified Pineau, who admitted, “No one in Europe does speed climbing.” In the following days, Kelleghan steadily trained Pineau in her tactics from sixty-odd Naked Edge laps. The pair would do a warm-up run and then a timed run, climbing the route in one hour 10 minutes, then 54 minutes, then 44 minutes, and finally, in 37:50.

In the United States, speed climbing’s main arena has been on the Nose of El Capitan. From a 47-day campaign on the first ascent, the time to ascend the 3,000-foot line has been whittled down to a blazingly fast 1 hour 58 minutes.

In the last decade, The Naked Edge has become Colorado’s local racetrack. In 1964, Layton Kor and Rick Horn made the route’s first integral ascent by aid and free climbing the technical cracks, chimneys, and faces of the sandstone arête. Seven years later, Jim Erickson and Duncan Ferguson made the first free ascent. Like the Nose, the prominence of the route, the popularity, and the ease of access tempted climbers to move faster on the sandstone. In 2012, the Colorado climbers Stefan Griebel and Jason Wells went “bridge to bridge” in under an hour. A friendly competition began between Brad Gobright, Scott Bennett, Griebel, Wells, and others, who whittled the time down until Joe Kennedy and Griebel set the current record of 22:44 on October 22, 2022. While the men’s time quickened, Kelleghan recruited fellow Boulder climber Becca Droz to set a new women’s record in 2021.

Last Go, Best Go

Standing by the bridge on March 28th, Kelleghan and Pineau processed their ten-second miss. The forecast showed incoming snow, so they decided to give it one more go. After a few hours of rest, they re-warmed up by climbing The Bomb, a short 5.4 on Wind Tower.

On the descent, Pineau realized that she could run down the East Slabs in her TC Pros. Her approach shoes’ broken laces wouldn’t be a problem. However, after blitzing through the morning, the fatigue of a second lap threatened to end their Naked Edge aspirations. Still, they geared up for a final attempt.

“My legs and my arms were already on fire when we started,” said Pineau. But this time—their ninth time climbing the route together—Kelleghan reached the base 30 seconds faster than on their previous attempt.

They were back in the game, tracking for the record. They raced through the climb, with Kelleghan’s heart rate averaging 173 beats per minute and Pineau’s averaging 162.

When they reached the top, Pineau untied and started running, intentionally not putting on her shoes. She bolted past Kelleghan, who coiled the rope and dashed down the East Slabs behind her.

As Kelleghan slapped her hand on the bridge, Pineau stopped the clock at 37 minutes and eight seconds—a new milestone for both the Naked Edge and for women moving fast on rock.

Watch a video of Kelleghan sprinting to the finish line and celebrating with Pineau below:

“It’s important to see women represented in the speed climbing world,” said Kelleghan, who has become a fixture of women’s speed climbing. Beyond Eldorado Canyon, Kelleghan has also become a must-watch climber in the Yosemite speed game. In summer 2024, she and Michelle Pellette climbed two El Capitan routes in a day: the Nose in eight hours 45 minutes and Lurking Fear in nine hours 45 minutes. They were only the second female team in history to climb El Capitan twice in 24 hours.

There has been a steady increase of women speed climbing in Eldorado Canyon. When Kelleghan and Droz set their 2021 record, only a few women had led the route in a single pitch: the two of them and Madeline Sorkin. Recently, Boulder climber Lynn Anderson joined the mix, setting the female-male partner Naked Edge record with Jack Neus in 28 minutes 32 seconds on September 13, 2024. Kelleghan suspects that the women’s record could go sub 30 minutes, but says that she and Pineau have other summer objectives. For now, their record will remain until another pair of women steps up.

The post Kelleghan and Pineau Set New Women’s Speed Record on the Naked Edge appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Get the timing, destination, goals, and more right

The post Timing Is Everything. Here’s How to Get it Right on Your Spring Climbing Trip. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Sitting behind a desk as snow covers the local crags makes warm days in Yosemite, Smith Rock, Red River Gorge, and other spring destinations sound dreamy. In the depths of winter, planning a spring break climbing trip becomes paramount for maintaining sanity. Making that fantasy a reality takes a bit of planning and some flexibility. Before you set off, consider timing, the weather, the best partners for the occasion, and the goals you want to achieve to make the most of your trip.

Timing Your Spring Break Climbing Trip Right

First, consider the amount of time you have. With ideal weather, most people can easily climb two days on and one day off. Sure, you can climb 14 days in a row straight. You can also stick your hands in hot lava. Setting a steady, sustainable pace for your trip will allow you to climb consistently well and make you less prone to injury.

So if you go on a week-long climbing trip, plan for about four days of climbing. If you can get away for a two-week spring climbing trip, expect to get in about nine days of climbing.

When you have your climbing days aligned, sort out how long the commute to the crag will be from where you’re staying. Travel time—both the daily commute and getting to and from your destination—cuts significantly into climbing and resting time. You should also take into consideration any time spent bouncing around between destinations. Doing a mega road trip can be fun. but hopping from one climbing town to the next can be exhausting, expensive, and eat into your climb time.

If your goal is really to focus on climbing, less is more—consider staying put at a single destination. You could also check out nearby towns or other outdoor attractions on your rest days.

For trips shorter than two weeks, traveling internationally can be hard because of the time difference. Jet lag takes a while to get over, even if you’re a pro. Likely, you’ll need to stay domestic or head south of the border. While Mexico’s climbing destinations may have fewer amenities than Europe, beating the time difference can save a day or more on a two-week trip.

Here are a few prime spring climbing trip destinations, with a few notes on timing to consider:

- For most folks, Bishop, CA requires a long drive to get to, but only a short daily commute from local lodging.

- Las Vegas is just a short plane ride away but requires a longer daily commute, particularly to reach the limestone crags when the sandstone is wet.

- Depending on where you’re staying, Yosemite can require both a long trip to get to and a long daily commute.

- Flights to Monterrey, Mexico put you within spitting distance of Potrero Chico or nearby El Salto. Both of these areas also have short crag commutes.

- If the weather where you live is climbing-friendly in spring, a spring staycation can actually be a great idea. This strategy lets you swap one or two days of travel for more climb time.

How to Outsmart Spring Weather

“Bad weather always looks worse through the window,” said singer/songwriter Tom Lehrer. Indeed NOAA’s forecast for a 30% chance of showers might feel like the promise of a hurricane, when in reality, it might just drizzle. While we can’t control the weather, we can choose places more likely to have good spring weather—and choose climbing destinations that have several climbing areas available in case a storm rolls in.

As a general rule, steep climbing tends to stay dryer in bad weather. Although it can seep for a few days after a big storm. Granite and limestone dry faster than porous rocks like sandstone and tuft. If there’s a chance of precipitation, check on the local ethics to avoid breaking the rock.

The other option is to climb in an area with a few different zones close by. Smith Rock can be a great spring destination, but if the weather’s bad there for a week, there are few alternatives. Conversely, Las Vegas may get snow, but it’s easy to escape to the sandstone boulders of Moe’s Valley or the limestone of the Utah Hills. Yosemite can get socked in with the weather, but the basalt sport climbing in nearby Sonora can be beautiful.

Another thing to keep in mind is the availability of a decent gym. While most climbing areas have an indoor option, the quality can vary. Often the smaller towns where you’ll find the best outdoor climbing have tiny gyms—or none at all. These facilities can work well for a short bit of bad weather, but motivating yourself to climb in a tiny gym for a whole trip can be hard. So if you pick a climbing destination with dicey weather, it might be worth considering what the local gym scene offers.

When choosing a destination, especially after wet winters, consider desert environments with less rain. Sedona’s soft sandstone can offer a solid option for those looking to get off the ground on some trad adventures. The adventurous bouldering in Roy, New Mexico tends to dry fast and be less crowded than Joe’s Valley. The Red River Gorge, while sometimes wet in spring, has a vast amount of quick-drying climbing.

How to Choose the Right Partners for a Spring Climbing Trip

The best trad route, sport climb, or boulder only gets better when you have amazing partners. Not only will a good partner fuel your climbing, but they can also make any challenges you encounter go so much better. Car troubles, injuries, and bad weather can all plague climbing trips. Having reliable friends around can make a trip significantly easier.

Not only can the right partners help you weather any literal storms, but they can also share the beta burden. From figuring out the moves on a problem to sorting out carpooling and finding a place to stay, partners can streamline planning, not to mention costs.

In an ideal world, pick partners who you’ve traveled with before and climbed with before. This is especially important if you’re planning a trip that’s longer than a week, or involves a remote or international destination you’ve never visited before.

The magic number depends on your personal preferences, but traveling with a single partner for a week or two can be intense, no matter how good of friends you are. Having a few other climbers around can also alleviate any tension about bad belays or poor spotting.

If you’re looking for solitude, there are a few places where you can climb alone. But if you’re looking for belays and spots, then heading to areas with friends is key. Having friends helps lighten the climbing load.

Guidance on Setting Goals for Your Climbing Trip

One of the best parts about climbing trips is having a variety of new and stretch objectives to try. There are all kinds of different goals you can set—here are a few ideas for goals for your spring climbing trip:

- Try all the classics in the area you’re visiting

- Go hard and focus on projecting one dream route

- Pack some hardware and establish something new

- Simply explore a new zone

Putting together a successful trip involves not only setting these goals but establishing a timeline for them. If you’re planning on projecting a route on a trip, aim to finish it at the 2/3 to 3/4 mark of your trip length. That gives you time at the start of the trip to get used to the style and moves. Then you can spend the middle of the trip attempting the project. Toward the end of your trip, you’ll then have extra time to either walk off with more sends or give it a few last-ditch efforts.

If you feel like you perform better under pressure, then find ways to manufacture that. Establish kill criteria—if you don’t hit certain goals within a set time frame, then move on. For example: If you can’t do all the moves by the end of your second session, then stop trying it. If you don’t one-hang by the third session, move on. This can also save you end-of-trip pressure, allowing for a more even-keeled trip. It also prevents you from getting over-invested in a project that you can’t finish in the allotted time.

Another important note about goals: Be willing and able to adjust your goals according to the weather, partners, and your abilities. Going into a trip, it’s easy to have a mile-long list of goals. But sometimes, a storm, a sick partner, or a lack of appropriate preparation derails your plans. Having some flexibility can help tremendously.

It’s also wise to set achievable goals. New climbing areas often take a while to adjust to. Expect a bit of a break-in period.

Finally, trips can be a great way to prepare for other goals. If you have a summer sport project and want to get stronger, head to a destination bouldering area to power up. If you’re looking to climb El Capitan in the fall, the long routes of Red Rocks can help you prepare. Set yourself up for future success by making a step toward your goals with your next trip.

Explore a map of some of the spring break climbing destinations discussed in this story:

The post Timing Is Everything. Here’s How to Get it Right on Your Spring Climbing Trip. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Hannes Puman becomes first to send the alt pitch to Changing Corners

The post El Cap Rhinoplasty: The Nose Gets Straightened appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

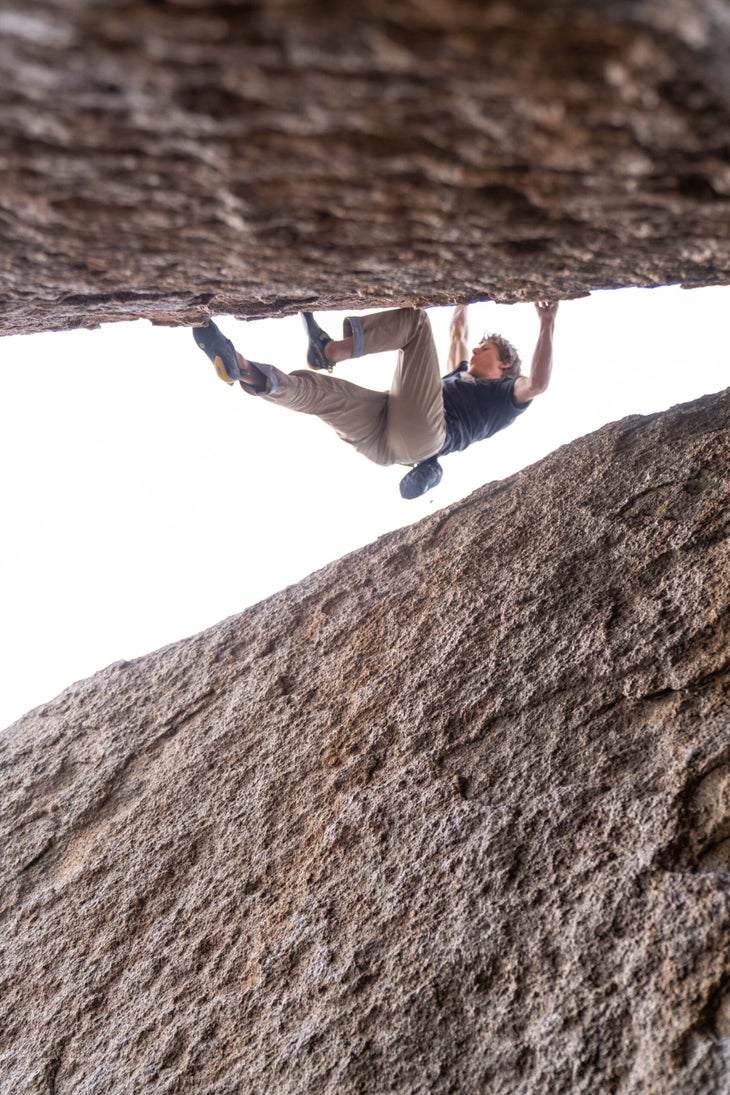

This December, 26-year-old Swedish climber Hannes Puman snagged the first ascent of the pitch known as The Schnoz on The Nose of El Capitan in Yosemite National Park. This V10 boulder problem has been an unsent alternative to the notoriously tricky Changing Corners (5.14a/8b+) pitch. As the first to send this variation, navigating past a pin-scarred corner, Puman has made the route a bit more accessible and made a step towards a more free and pure El Capitan.

Freeing the Nose

The Nose, which climbs up the prow of El Cap, splitting the southeast from the southwest portions of the wall, has a history dating back to 1958. That year, Warren Harding, Wayne Merry, Rich Calderwood, and George Whitmore became the first to climb the route over 47 days, drilling a bolt ladder to the summit. In the ensuing years, the route became the crucible for free climbing.

The route’s path to a free ascent required significant work. In the late `60s, Jim Bridwell and Jim Stanton freed the classic Stoveleg Crack pitches at 5.10+/6b+. In 1975, Ron Kauk, John Bachar, and Dale Bard freed more of the route, eliminating the aid except for a handful of pitches on the upper section at 5.11+/7a. Five years later, Ray Jardine made a significant push on The Nose, fixing lines and working large sections. He manufactured holds to create a traverse that bypassed the King Swing. However, his chipping was not well-received and Yosemite climbers drove him out of the park. For the next decade, climbers invested their energy into freeing other parts of El Cap.

Then in 1990, Brooke Sandhal tackled the route. His tactic was to rappel in from the top to work the crux. He rebolted many of the belays and added lead bolts for free climbing where necessary. Then he quickly accessed the four pitches that hadn’t been free climbed yet: The Great Roof, the pitch above Camp V, the Changing Corners, and the Harding Bolt Ladder. The latter is the final pitch to the summit. Sandhal made the first free ascent of the final pitch, then sorted the beta and sent the pitch above Camp V. Only two cruxes remained: the Great Roof and the Changing Corners.

History of the Changing Corners

In 1990, water streaked down the Great Roof, so Sandhal and Dave Schultz looked at the Changing Corners. Scouring the face, they found a variation 12 feet to the left. “It was more straightforward climbing and less worming around in that corner,” Sandhal says. The pair powered through most of the moves, climbing up to a small stance, then launching into a boulder problem.

“You do a big span move and get a tiny flat edge and then you’d have to match it,” Sandhal remembers. “Then you’d piano, getting your left hand where your right hand was.” This allowed Sandhal to reach over into the Changing Corners and finish up the 5.10/6b climbing on that pitch. The high temps made it too hard for Sandhal to link the climbing though.

The following year, Sandhal returned with Lynn Hill, who made quick work of the Great Roof. But as a short-statured climber, she lacked the reach to send the variation pitch, so she tackled the original aid line. By performing a contortionist series of stemming, arm barring, and El Cap disco, she freed the Changing Corners. Hill and Sandhal then attempted the route from the ground over five days. Sandhal was able to do all the moves on the Great Roof but ran out of time.

In the end, Hill ended up redpointing the two crux pitches, making the first free ascent of El Capitan via The Nose. A year later, she returned to climb it in a single day in one of the most significant climbing accomplishments in history. Despite attempts by some of the world’s strongest climbers, the route has only seen a dozen free ascents in the past 21 years.

Why so few? The answer usually boils down to the Changing Corners (5.14a/8b+) pitch. The cryptic style makes it hard to repeat. While working the route in 2004, Matt Wilder scoped Sandhal and Schultz’s variation. Supposedly a hold had broken, making it impossible to traverse into the Changing Corners.

In the early 2000s, Alex and Thomas Huber and Ivo Ninov had bolted a belay at the small stance, making it more accessible. This allowed Wilder to stand and stare at a sequence of holds that lead more directly to the Changing Corners anchor. “It’s hard and technical,” Wilder says of the variation. Though he was nearing a ground up attempt, on the day he sent the variation on toprope, he tore his rotator cuff lower down on a 12d/7c pitch, thus ending his bid. Huber and Ninov also sent the pitch, though they did not free the route.

The Nose Gets Straightened

Earlier this season, Alex Honnold added a lead bolt to The Schnoz to make climbing the variation safer, and to direct the line to the anchors of the Changing Corners. “It’s the way it should be,” Honnold says. “You wind up at a nice stance, you skip the other hanging belay on The Nose, and you do the crux right off the belay. It’s kind of a better thing.”

After dialing the V10 moves, Honnold attempted the route from the ground, sending through the Great Roof in a day with Tommy Caldwell belaying. “I fell on the last move of The Schnoz,” Honnold says.

View this post on Instagram

After splitting a tip, he tried to send it with his back three fingers. Then he split another tip. “I was just bleeding everywhere,” says Honnold, whose index and middle fingers were gushing blood. Unable to hold on despite numerous attempts, he tensioned over to the Changing Corners and finished up the route. “Is this middle age and not quite having the fire?” Honnold remembers contemplating when he left the Valley.

Hannes Puman frees The Schnoz

Honnold may have lacked the fire this year, but it was alive and well inside Swedish climber Hannes Puman. On his two-month trip from October through early December, he worked his way through the Yosemite classics. He bouldered in the Valley, flashing the technically demanding Kauk Slab (V8), as well as the iconic Midnight Lightning (V8) and the highball King Air (V10).

Puman headed to Tuolumne, where he fired off Peace (5.13c/8a+) on Medlicott Dome. He stemmed up Book of Hate (5.13d/8b) at the Elephant’s Graveyard and crushed his fingers in the vice grip of Cosmic Debris (5.13b/8a). He also explored longer routes, including an ascent of Lost Arrow Chimney, a 10-pitch 5.10a route that navigates a series of wide climbing on the Yosemite Falls Wall. And he made quick work of Wet Lycra Nightmare (5.13d/8b A0) on Leaning Tower and Final Frontier (5.13b/8a) on Fifi Buttress.

Toward the end of this send spree, Puman turned his attention to El Capitan, where he and his partner Jacob Östman, free-climbed Free Rider* (5.13a/7c+). “It was my first big wall,” Puman says.

They began the route the day after a storm, so many of the cracks were wet or damp. They expected the climb to take three days, but it took five. Without a #7 camalot, Puman climbed The Hollow Flake without protection. Mice ate their water tank and their haul line got a core shot. “We didn’t really expect it to be such an extreme experience,” Puman says. Despite the challenges, they made easy work of the climbing. Puman fell once on Freeblast and once on the Enduro Corner pitch, while Ostman only fell on the Boulder Problem pitch. They redpointed the pitches and walked away with a free ascent.

After just two rest days, Puman went on to tackle The Nose. “I was really exhausted,” he recalls. But he decided to just try his best and “see what happens.” That attitude helped carry him up the wall.

With support from 22-year-old Scottish climber Jamie Lowther, Puman made it to the Great Roof. But when he got there, he discovered water dripping from the pitch. He attempted to dry the holds, but each time he dried it and started climbing, different holds became wet. He fought through the water, sending the hard underclinging traverse of the Great Roof.

Finally, Puman reached the Changing Corners. He had rappelled into the pitch before, working the moves. While he had hoped to send both the Changing Corners and the variation, he reached the crux tired. “At that point, I just wanted to do it,” Puman says of taking on The Schnoz. “It’s a lot more basic and Changing Corners is super technical,” he adds. So he crimped his way through the hard moves and made the first ascent of the pitch. Then he continued to the summit, becoming one of the elite few to have free-climbed Yosemite’s classic route.

View this post on Instagram

So why did it take so long to free The Schnoz? Many free climbers on The Nose may have not even known about this alternative route, and weren’t looking for the beta. The path of least resistance was to stick to the aid line, and until December 2024, that’s what everyone had done. Since Honnold had been working the line and chalked it shortly before Puman’s ascent, he in effect paved the way for the variation to be freed.

Ultimately, Sandhal, Wilder, Honnold, Puman, and other climbers’ attempts on The Schnoz mark an evolution in Yosemite’s big wall free climbing evolution. Instead of following the exact aid line, climbers have moved along the wall, searching for better alternatives to the chipped and pin-scarred terrain. While much of El Cap free climbing depends on freeing existing aid lines, sending The Schnoz shows that not every hard pitch needs to be pinned out first, a concept that may preserve the rock of other formations.

*Although the route is today most commonly formatted as Freerider, Alexander Huber has noted that the route was actually meant to be formatted as two words (Free Rider). This is a reference to the 1969 film Easy Rider.

The post El Cap Rhinoplasty: The Nose Gets Straightened appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

I spent 40 days working on Freerider before freeing it in a 16-hour push. Here's what I wish I knew at the start of that process.

The post 5 Things I Wish I Knew Before Climbing El Capitan appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

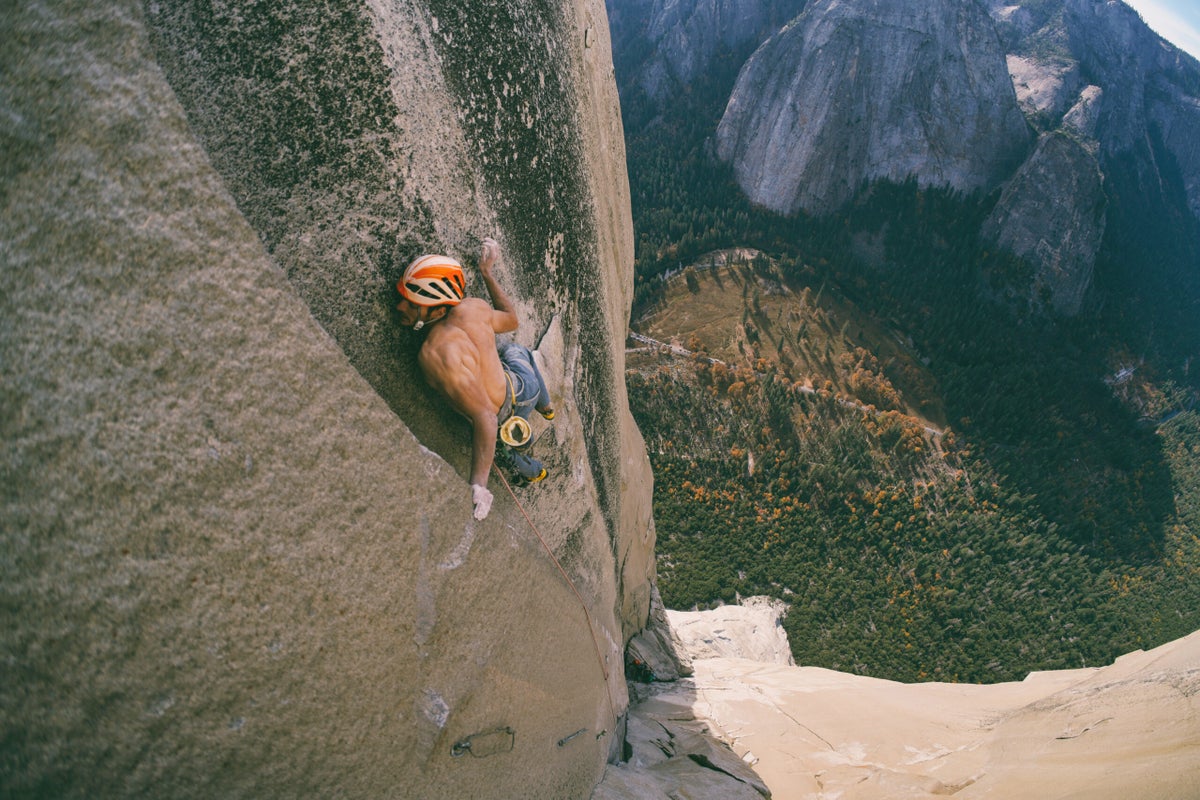

El Capitan, the world’s most accessible big wall, sits just a thousand feet from the road in sunny California and begs to be climbed. If you’re a free climber, the Free Rider (VI 5.13a; 3,000ft ) is the “easiest” true El Cap route. That makes it an obvious target for pros trying to flash the Big Stone (congrats Babsi Zangerl!), but it also makes it an obvious choice for mortals like me. I spent years preparing for the climb on other big Yosemite walls before finally, in 2012, beginning the process myself. Over the next three years, I made four ground-up attempts and spent roughly 40 days working the pitches. Then, in 2015, I made a 16-hour ascent, leading all the pitches. Needless to say, I logged some time on the wall, spending nights in the alcove, days hiking to the top and rapping in, and weeks staring up at the route, dreaming.

Here’s everything I wish I’d known at the start of that process.

1. Freeing El Cap Requires All the Skills

With a V7 slab boulder, pumpy 5.12 sport style liebacking, burly 5.11+ crack climbing, a huge 5.11 slab, long sections of 5.10 offwidth, and a lot of moderate climbing in between, Free Rider will test your movement strength and skill set. But success isn’t just about climbing. You’ve also got to be an experienced wall climber (familiar with hauling, short-fixing, and prolonged exposure) and accrue Free Rider specific logistics, like where to bivy, how much water to haul, and how many wag bags you’ll bring per day.

Big wall free climbers tend to fall into one of two camps: one-arm pull-up mutants who can’t set up a portaledge, and wall rats who’ve never crimped a 10mm edge in their life. If you’re the former, then climbing El Cap is simply a matter of reading some instructions. When you arrive at the base of Freeblast, simply type “how to haul a bag” into YouTube, then remember the old El Cap adage: Don’t bail and don’t die. You’ll make it to the top.

If you’re the latter group—comparatively weak but experienced—then you probably need to sell your iron skirt of cams, pick up a crash pad, drive to Bishop, and try Yayoi Right (V7) and Junior’s Achievement (V7/8). It takes a long time to build the technical ability to climb hard on El Cap. Get a coach. Climb on every Moonboard set. Drink protein shakes until you can do a one-arm pull-up. Redpoint 5.13 sport routes and 5.12 slabs. Then head back to El Cap and do a quick session at YouTube university to freshen up your wall skills.

If you’re one of the unlucky ones—neither podiuming at a World Cups nor aiding the Nose in a day—I suggest you either call up Connor Herson and ask if he has some coat tails you can ride on.

Alternatively, you could…

2. Work Your Way Up to it

It’s fairly common for people to start up El Cap and quickly bail because they’re not ready. Building a base of experience will prepare you for the wall. You can start before you even get to Yosemite with smaller walls like Moonlight Buttress (5.12c) in Zion National Park, The University Wall (5.12a) in Squamish, Romantic Warrior (5.12b) in the Needles, The Rainbow Wall (5.12a) in Red Rock, or Ariana (5.12a) on the Diamond.

When you arrive in Yosemite, try something less committing like The Final Frontier (5.13b; 1,000 ft) on the Fifi Buttress or The Westie Face (5.13a A0; 1,000ft) on the Leaning Tower. Also run through a few classics like Astroman (5.11c; 1,000ft), The Crucifix (5.12b; 700ft), and even warm up on Freeblast (5.11b; 950ft) to hone in on the start of the route. Do all those. Then do some laps on Generator Crack (5.10c), a horrendous roadside offwidth; and on your way back to Camp 4, stop by the Cathedral Boulders and send The Hexentric (V7), The Octagon (V6), and The King (V6) to ensure your fingers are strong enough for the “5.11” move off Heart Ledges and, of course, the Boulder Problem.

It wouldn’t be a bad idea to have climbed the Nose (VI 5.9 A1), Zodiac (VI 5.9 A3) or another El Cap route just to know how to jumar efficiently and experience true big wall life, which is like #vanlife but not as posh.

While you don’t need to have done everything on this list, you want to have a solid resume before applying for the job.

3. Partners Matter

“Good thing you didn’t pull us off the mountain,” Alex Honnold shouted to me from Hollow Flake ledge.

I’d just finished downclimbing and then thrashing up the Hollow Flake Pitch (5.8), climbing 280 feet but only gaining 70 feet on the mountain. When I’d got to the ledge at the end of the pitch, I short-fixed the line and then launched up the 5.7 chimney that leads to the Monster Offwidth. Tired from the climbing, I went further into the crack than I should have, offwidthing rather than chimneying the outside. Almost at the exact moment that Alex reached the ledge and unclipped the rope, I slipped. There was no gear between us. I slid down toward the chasm below and would soon be pulling Honnold off with me. In desperation, I slammed my feet across the wall, arresting my fall by essentially falling into the chimney. It was a World Cup parkour maneuver. I could feel blood pouring down my back.

“That was scary,” I said.

“Keep going!” Honnold responded.

So, buoyed by his encouragement and my adrenaline, I kept charging up the mountain. While I didn’t send during that attempt (I’d fallen repeatedly on the crux of the Boulder Problem) I’d felt confident in my ability to go for it having Honnold as a partner. And more importantly, Honnold helped me maintain my composure when things went awry. “Things like that happen,” he said. “You’ve got to just get going again.”

Free climbing El Cap requires a lot of support. Make sure to climb with someone who’s competent with the rope skills, the hauling, the wide climbing, and the basic logistics of big walling, but who also wants your success and shares your dream of flowing over the Big Stone.

4. The El Cap perspective—i.e. it’s not always fun

During the years I was trying Free Rider, every time I sat in the meadow, I’d stare up at El Cap, wishing I was on the wall. I pictured laybacking the Enduro Corner and jamming the Scotty Burke Offwidth. But when I was actually got on El Cap, for instance while thrashing myself as I rehearsed the Monster Offwidth before my successful ascent (I rappelled into it and climbed it eight times in a single week, just to get it dialed), I’d look down at El Cap Meadow and wish I was there, eating Have’A Corn Chips with Tom “Ansel” Evans.

The reality is that climbing on El Cap can be scary and intimidating and uncomfortable. It’s normal to be on the side of the wall and suddenly decide you’d rather be at home snuggling your cats. But it helps to remain present—to think of the moment as it’s happening—and to remember how unlikely and amazing it is that you’re up there. Whether you’re jugging to Heart, smearing in the heat on Freeblast, or hiking loads down the endless East Ledges, know that these un-fun moments make the whole process more rewarding.

5. Success or Failure, the Memories Remain

I managed to send Free Rider, but if I hadn’t, I’d still get to remember having a dance party with Hazel Findlay in the Alcove, helping two stranded climbers off the Salathe Wall with Honnold, and watching Lyn Barraza drop a shoe from Mammoth Terraces. All of these memories will stick with me longer than the shoulder scars from the Monster Offwidth—though I suspect those scars will be with me for a while.

The post 5 Things I Wish I Knew Before Climbing El Capitan appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

John Middendorf revolutionized portaledge technology, allowing climbers to survive terrible storms on big walls.

The post A Climber We Lost: John Middendorf appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

You can read the full tribute to Climbers We Lost in 2024 here.

In the winter of 1986, John Middendorf, Steve Bosque, and the late Mike Corbett shivered, nearly hypothermic, on the South Face of Half Dome. It was the 25-year-old Middendorf’s 40th big Yosemite route. On their fourth day on the wall, light rain prompted the team to don their portaledge flies. Their radio promised clearing weather, but, as the day progressed, the rain and wind instead intensified. The tall, lanky Middendorf hucked the radio off the wall in frustration. By the next morning, they were being smashed against the wall by 50+ mph winds, and their portaledges had fallen apart. Their frozen ropes and the traversing nature of the route made retreat impossible.

The storm changed Middendorf’s life and the climbing world.

John William Middendorf IV, who passed in his sleep on June 21 while visiting his family in Rhode Island, was born in New York City on November 18, 1959, the son of John William Middendorf II, former Secretary of the Navy, and Isabelle Paine Middendorf. He grew up with his three older sisters, Fran, Martha, and Amy, and his younger brother, Roxy Paine, in Connecticut, the Netherlands, and Virginia.

Middendorf began climbing in Colorado, when, at age 14, his mother sent him to the summer camp at the Skyline Ranch Mountaineering School in Telluride Colorado. It was a decision that changed his life.

“I was lucky enough to be his instructor,” the renowned free soloist Henry Barber told Climbing. Barber climbed extensively with Middendorf and took him on his first ever first ascent: a 5.10 near Colorado’s San Animas River. “He approached his initial climbs the same way as he approached his big wall things, it was always a learning experience,” Barber said. “He was determined.”

Middendorf became an insatiable climber. In 1978, just after finishing high school, Middendorf traveled around the U.S., climbing in Boulder Canyon on Coffin Crack (5.10b) and Curving Crack (5.9+). Middendorf attended Dartmouth College for a year before transferring to Stanford University, where he eventually graduated with a Bachelor of Science in Mechanical Engineering in 1983. (A lifelong learner, he later studied fabric architecture at the University of Sydney, and received masters degrees in Architectural Design from Harvard University and Teaching from the University of Tasmania.)

When he moved to California, Middendorf met Bob Palais at a Grateful Dead show and joined a posse of climbers splitting time between shows and Yosemite. “He had a magical aspect to him,” Palais said of Middendorf’s humorous energy and his lively spirit. Middendorf would sing a parody of Country Joe & The Fish’s “Vietnam Song”:

It’s one, two, three,

What are we climbing for?

Don’t ask me, I don’t give a damn.

Next stop El Capitan!

Shortly after graduating from Stanford Middendorf moved to Camp 4, where he worked from January 1984 to the fall 1986 as a Yosemite Search and Rescue Member. During his time in the Valley, fellow granite climber Grant Hiskes mangled Middendorf’s last name to Dusseldorf, which was shortened to “Deucey,” which stuck.

Deucey spent over 2,000 nights in Yosemite during his climbing career and made 30 ascents of El Capitan. Middendorf soloed The Prow (V 5.8 A4) on Washington’s Column for his first wall route, and his resume quickly expanded to El Capitan, including the 1985 first ascent of Atlantic Ocean Wall (VI 5.10 A4) with John Barbella, the 1990 first ascent of Cosmos (VI 5.9 A3+) with Jimmie Dunn, and the 1993 first ascent of Flight of the Albatross (VI 5.10 A4) with Will Oxx. In December of 1984, Middendorf and Dave Schultz set the speed record on the Nose (VI 5.9 A2) at 10 hours 45 minutes.

He also climbed elsewhere in Yosemite, making first ascents of The Kali Yuga (VI 5.10 A4) on the Northwest Face of Half Dome in 1989, Autobahn (5.11+ R/X) on the South Face of Half Dome with Charles Cole and Rusty Reno in 1985, and Aqua Vulva (VI 5.10 A4) with Eric Kohl on the Yosemite Falls Wall in 1989.

But the storm on Half Dome, in the winter of 1986, remained one of Middendorf’s seminal climbing moments. As he shivered on the wall with Corbett and Bosque, having thrown the radio off the wall, he wondered if he’d survive. Luckily, a few friends had hiked to Lost Lake to check on them and called out to see if they needed a rescue, which they confirmed. They continued shivering on the wall as snow mounted on their broken portaledges. On their sixth day on the wall, the sun briefly cut through the clouds. They could see another storm coming, so they chopped out their buried ice-covered ropes, planning to embark on a horrific descent attempt. Then they heard the thuds of a helicopter. The team was plucked off the wall, hypothermic and burdened by nightmares, but otherwise unscathed.

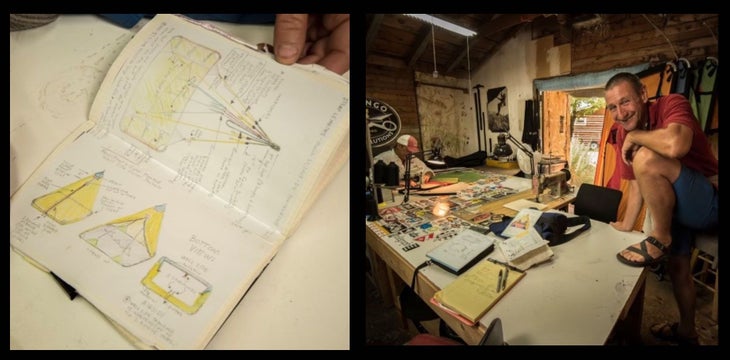

Middendorf was a lifelong innovator

After the storm Middendorf began to wonder what if he was wasting his mechanical engineering knowledge. “The technology wasn’t there in portaledges for a storm of that caliber at the time,” Middendorf said in a Common Climber interview. So he began A5 Adventures, a company based in Flagstaff, Arizona, that was dedicated to manufacturing cutting edge big wall climbing equipment. He redesigned portaledges and their flies, making significant advancements in both their day-to-day functionality and their storm tolerance. In 1997, he sold the company to the North Face, where he briefly worked as a designer. But it wasn’t long before he found himself disillusioned. “It was never about making money for John,” his climbing partner Simon Mentz said.

For a while after that, Middendorf stepped away from climbing equipment. He worked as a surveyor and had a GIS business in Colorado. He worked as a reporter for a newspaper in Pagosa Springs, Colorado. He guided river tours in the Grand Canyon. And, later, he taught high school mathematics, science, and robotics in Tasmania. But in 2016, he returned to big wall equipment, redesigning portaledges under the brand D4.

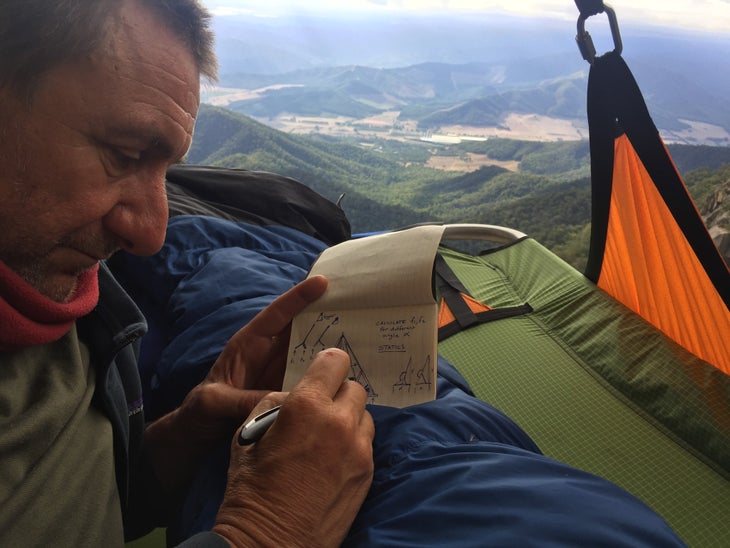

“He was always about speed, efficiency, and tactics,” said Bill Hatcher, a longtime friend who climbed with Middendorf and Brad Quinn on the first ascent of Tricks of the Trade (V 5.10d A2) in 1993. “My image of Middendorf is he has a pad of paper and a pencil and he’s figuring out the next great problem. That’s his approach to climbing.”

Middendorf also applied his big wall techniques in the alpine. In 1992, Middendorf used the tools he’d crafted at A5 Adventures to climb Great Trango Tower (20,500ft) in Pakistan’s Karakorum. Climbing in a capsule style, establishing a portaledge basecamp, and fixing lines up the mountain over 16 days, Middendorf and Xaver Bongard established Grand Voyage (VII 5.10+ A4+ WI 4), which still stands as an unrepeated testament to Middendorf’s climbing prowess. In December 1993, he took what he’d learned on Great Trango and climbed the Compressor Route on Cerro Torre with Conrad Anker in just 14 hours.

After moving to Tasmania in 2008, Middendorf continued to climb, exploring Mt Arapiles in Australia and testing his D4 portaledge with Simon Mentz on Mount Buffalo’s Ozymandias Direct (AUD 10 M4; 1,000ft) with Simon Mentz. He also climbed with his son Rowen on Mount Arapiles. But over time, his focus shifted toward education. “John was always an enthusiastic student himself,” said Mentz, and he wanted to pass on his knowledge.

Middendorf wrote extensively about his climbing, sharing both his exploits and his technical knowledge. His website bigwall.net was the first of many websites that Middendorf coded himself and was an important source of information in its time. In 1988, Middendorf wrote Big Wall Tech Manual, a 50-page big wall manual published by A5 Adventures. In 1994, John Long and Middendorf wrote How to Climb Big Walls. In 2023, he wrote and published Mechanical Advantage Volume 1: Tools for the Wild Vertical and Mechanical Advantage Volume 2: Tools for the Wild Vertical, both of which investigate climbing through the lens of climbing tools. Middendorf also planned on writing a history of Great Trango Tower.

If it wasn’t for Middendorf, Camp 4 might be a parking lot

On January 2, 1997, warm weather and heavy rainfall in the Sierra caused the Merced river to rage through the Valley floor, causing unprecedented destruction. When the water receded, the National Park Service proposed using the $178 million appropriated by Congress after the flood to expand the Yosemite Lodge north over Northside Drive to Swan Slab and the Columbia Boulder, replacing Camp 4 and its boulders with parking lots and buildings. In response, Middendorf joined forced with Greg Adair and Tom Frost to form The Friends of Yosemite Valley, which rallied the American Alpine Club, Access Fund, and various Yosemite climbers to sue the National Park Service and prevent the destruction of Camp 4 citing the National Environmental Policy Act. The lawsuit, combined with other pressure from climbers, helped get Camp 4 listed on the National Register of Historic Places, which guarantees its preservation. For Middendorf, saving Camp 4 was just the beginning of a globe-spanning conservation career—some of which involved putting his own body on the line.

Late one night in 2018, when logging companies in Tasmania were intent on plowing down hectares of takayna (the Tasmanian rainforest), Middendorf and Erik Hayward snuck into the forest south of the Arthur River carrying a haul bag filled with water, food, ropes, and a portaledge. When they reached a 14-meter myrtle that he’d previously climbed with his son Rowen and daughter Remi, Middendorf ascended the tree and anchored his portaledge to the myrtle. “This was an eviction and he was holding space,” Hayward said of Middendorf’s activism.

Middendorf also worked hard to advance the technology that made these protests possible. In 2010, he joined Bill Hatcher, who was documenting an aerial blockade in the Upper Florentine that aimed to save Tasmania’s old growth forest. Hayward and other activists from the Bob Brown Foundation had hiked heavy plywood bed frames into the forest, climbed the eucalyptus trees at night, and anchored their ledges to the logging equipment to stop the loggers from destroying the forest. Seeing the beauty of the forest and wanting to contribute, Middendorf donated portaledges to the cause. His portaledges were lightweight, which meant that activists could hike farther into the forest, easily bypass loggers, and set up tree camps quickly, allowing them to get ahead of and stop the destruction.

After his experience at The North Face, Middendorf wanted his portaledge innovations to be open source—something that climbers and forest activists could replicate if they didn’t have the resources to purchase one. “He was always willing to share about the things he could help with. He was a real innovator,” Hayward said. Outside of the Bob Brown Foundation’s campaign center in Hobart, Middendorf and Hayward set up “Deucey’s Sew Table of Dreams,” a place where Middendorf showed activists how to create throw bags to better catch trees and how to cheaply make portaledges to replace the ones confiscated by the authorities. “John’s principal idea was that we need to make it easier for anyone [with access to] a home sewing machine to create the means to defend earth,” said Hayward.

Middendorf also sewed extensively for his friend Paul Pritchard, who kayaked with Middendorf often. Pritchard only has use of one arm after a nearly fatal fall on Tasmania’s Totem Pole, and Middendorf engineered and adapted gear for Pritchard so the two could adventure together. “He was always a hero to me,” Pritchard said.

John Middendorf: family man

While river guiding in the Grand Canyon, John met his wife, Jeni, who was also guiding at the time. They married in 2006 in Pagosa Springs, Colorado, had their son Rowen, in 2007, moved to Hobart, Tasmania, in 2008, and had their daughter Remi in 2012. “He was a hands-on dad who loved sharing experiences and adventures with his children,” said Jeni.

In 2020, Bill Hatcher, Middendorf, and Rowen went on a road trip to Rowen’s first sculling race. As a school kid, Middendorf had been on a rowing team, and he wanted to share that experience with his son.

“He was the perfect mentor any child would want,” Hatcher said, describing how Remi would shadow her father around his shop, answer all her questions, and indulge her curiosities.

Middendorf took both of his children climbing at Mount Arapiles and across the world. With Rowen, Middendorf climbed Devil’s Tower in Wyoming, hiked around Tasmania, and skied at Hakuba in Japan. Middendorf had two hip replacements but still charged. “To be 64 and to keep up with me at 17 is pretty impressive,” Rowen said.

At night, he read Archie comics with Remi. He also took her to Bali. Recently, the family took a 20 day trip down the Grand Canyon, further cementing themselves as an outdoor family. “I couldn’t imagine having a better dad,” Rowen said.

“John gained many accolades throughout his life, and he touched many lives with his brilliant mind, his generosity, innovations, knowledge, creativity, wisdom, and care for the environment,” said Jeni. “But his biggest success was his dedication to his family whom he loved more than anything. He was truly an extraordinary and beautiful human being.”

Related:

- Was This Yosemite’s Most Miserable Shiver Bivy? by John Middendorf

- “I Tried to door More With Less”: An Interview with Henry Barber

- A Climber We Lost: Mike Corbett

You can read the full tribute to Climbers We Lost in 2024 here.

The post A Climber We Lost: John Middendorf appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

After months of work (and more than a 100,000 vertical feet of hiking) Chase Leary and Andy Puhvel finally freed ‘Keel Haul’ (5.13c; 2,000ft). The crux is pitch is above 14,000 feet.

The post California Has a New 5.13c Big Wall—It Tops Out at 14,000 Feet appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

“It’s the Salathé Headwall of the high country,” said Andy Puhvel of the immaculate crack crux on his and Chase Leary’s 17-pitch masterpiece, Keel Haul (V 5.13c). Located on the east face of Keeler Needle, a 14,260-foot sub-peak of Mount Whitney, their 2,000-foot line is a free variation of the aid route Australopithecus (VI A3+), established in 1999 by Ammon McNeely and Kevin Conti. The technical climbing begins at 12,400 feet and tops out in the thin air above 14,000 feet. When they sent, in early June, their route became one of the highest hard crack climbs in the United States, with two pitches of 5.13, four pitches of 5.12, four pitches of 5.11, and more of moderate terrain.

In fall 2022, Puhvel was hiking near the Keeler Needle and, in the afternoon light, saw a splitter crack running through the headwall. On April 20, 2023, during the heaviest snow year that the East Side had seen in decades, Puhvel recruited Leary to rap in and investigate. They spent 45 days at the Whitney Massif over the next year, cleaning the holds, trundling loose rocks, and bolting the belays. Their top-down tactics allowed them to clean the route as much as possible. “We take a lot of pride in making our routes buffed,” Puhvel said. “We want them to look like they’ve been climbed 30 times.”

They attempted to free the line twice in 2023 but failed to send the crux eleventh pitch, the Gemstone Crack. At first, they tried to climb the route over multiple days, spending the night on a portaledge, but they found it hard to recover given the altitude.

“We woke up super hammered from not getting any sleep,” said Puhvel, “so we decided to try to send it in a day.”

Climbing hard 5.13 at altitude was also a challenge. “In the beginning, it was pretty dang harsh,” he said. “Even jumaring last year I was like, Oh my god, my heart and my lungs.”

This year, they got fit for the altitude early in the season, hiking out to the route six times between early April and early June. When they saw temps of 102℉ in Lone Pine, they knew temps on the route would be in the idyllic 50s. “The moment the sun hits, you could be shirtless,” Puhvel said. The prevailing winds come from the west, but because the route faces east, the winds just pass over, allowing them to climb despite frequent 30-40 mile per hour wind reports.

On trip 27, the pair started the approach—which gains 4,600 feet of vertical in just 5 miles—thinking, “Damn, we’re kind of over it.” Nevertheless, at 6:30am, they began up the wall.

After 10 pitches of mostly 5.11 and 5.12 cracks, they arrived at a 300-foot overhanging headwall, home to the 40-meter 5.13c splitter they called the Gemstone Crack. After Leary successfully led the pitch—which protects with small cams, nuts, and two bolts—Puhvel followed it cleanly. He’d just reached the belay when the skies opened up.

“If it had just rained 10 minutes longer, everything would have been in flux,” said Puhvel of the storm. “We would have gotten wet and cold, the route would’ve got too wet. But instead, it did that 10% drizzle thing for half an hour and nothing got too wet and we could finish.”

They freed the last 5.12 pitch, followed by four pitches of 5.10 and 5.8, summiting at 6:30p.m., 12 hours after they started. They rappelled the route with two 60-meter ropes.

Prolific developers

Andy “Big Hippy” Puhvel, a 53-year-old Bishop climber who runs the Youth Climbing League, a Bay Area recreational kids climbing league, has established a half dozen Sierra routes with Chase “Swami” Leary, a 33-year-old East Side local who works as a Mammoth ski patroller. In the 2023 edition of the American Alpine Journal Puhvel describes Leary—whose father, Kevin Leary, made the first ascent of The Gong Show (5.11d), a classic roof crack in the eastern Sierra, and the Buttermilks classic Leary-Bard Arete (V5)—as “a local granite master whose wizardry on the rock has earned him the nickname ‘Swami.’”

“We climb like bread and butter,” said Puhvel of his partnership with Leary.

The pair have recently emerged as some of the most prolific developers on the East Side of the Sierra, making the first of such lines as King of the Jungle (5.14a) and, with Peter Croft, the five-pitch Green Thunder (5.13b) and the six-pitch Up in Smoke (5.13a) on the Hulk.

In 2022, Puhvel and Leary added four striking routes to the textured green granite of Trapezoid Peak, including Puff the Magic Dragon (5.12b; 5 pitches), the Shield of Dreams (5.13b; 6 pitches, protected mostly by RPs), Harvest Time (5.12d; 6 pitches), and Rasta Root (5.12b; 5 pitches). The Trapezoid routes, which top out at 13,000 feet, added a bunch of classics to a highly accessible section of the High Sierra. The formation is a 15-minute drive from downtown Bishop and a two-and-a-half-hour approach. “You can make it back to Bishop for restaurant time,” Puhvel said.

Puhvel speculated that the Keeler Needle is home to other free-climbable routes, and he has eyes on Crimson Wall (5.12d A3), which was first aided in 1992 by Mike Carville, Kevin Brown, and Kevin Steele and is named after the pre-dawn glow on the wall. It has only a single pitch of aid.

And after that? Leary and Puhvel plan on exploring other formations in the Sierra. “Chase and I have a thing that as long as the lines keep appearing as really classics, we keep doing ‘em,” Puhvel said.

The post California Has a New 5.13c Big Wall—It Tops Out at 14,000 Feet appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

The new HBO film "Here to Climb" offers an analytical and surprisingly candid exploration of Sasha DiGiulian's journey from solitary sport climber to team player. The film debuts Tuesday, June 18 at 9pm ET/PT on HBO.

The post Sasha DiGiulian Gets Surprisingly Candid About Career in New HBO Film appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

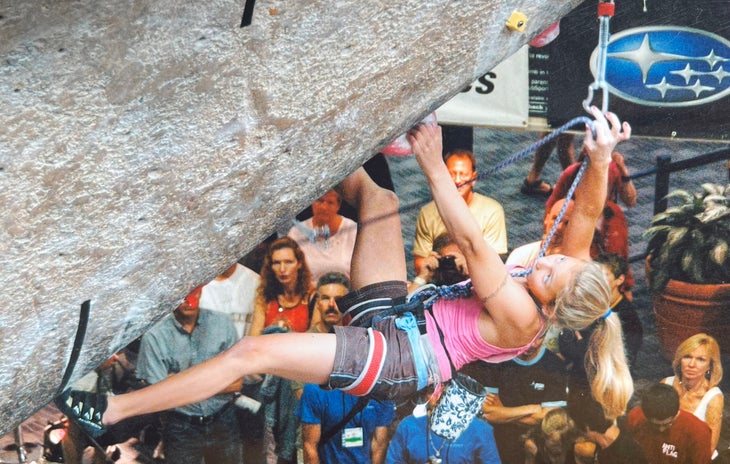

Midway through Sasha DiGiulian’s new eighty-minute HBO sports documentary, “Here to Climb,” she expresses one of the film’s major tensions: “You have to be selfish,” she says. Early in her climbing, DiGiulian’s mom acted as her belayer so she could spend time on the wall and not waste time belaying other people. Thanks to support like this—and personal dedication—DiGiulian became one of America’s most accomplished sport climbers, sending some of the hardest sport routes around the world, and she recently ticked off her 50th 5.14. But when she shifted from short sport climbs to making first female ascents of longer, multi-pitch routes, she found that focusing on herself wasn’t enough. “Big wall climbing is about teamwork and about partnership,” professional climber Cedar Wright says in the film. DiGiulian, admittedly, needed to learn how to climb with others.

The main narrative of “Here to Climb,” which debuts June 18 on HBO, uses DiGiulian and Lynn Hill’s 2023 ascent of the three-pitch 5.13c Queen Line on the Flatiron’s Maiden to demonstrate DiGiulian’s development as a climber and teammate.

DiGiulian grew up with a poster hanging on her wall of Hill making the first free ascent of the Nose of El Capitan with the caption, “It Goes Boys!” And, in the film, Hill assumes the role of mentor and DiGiulian’s foil. Though they both stand at the forefront of climbing in their respective eras, the two women developed vastly different understandings of what it means to be an elite climber. Hill came from a time before social media, where even groundbreaking ascents, like Hill’s first free ascent of the Nose, were understated. Digiulian, meanwhile, a late-generation millennial, discusses her focus on monetization and hyping her ascents. “I took a very business-forward approach to my career,” DiGiulian says, which allowed her to move from a skilled climber to a professional who capitalized on her social media reach.

“She’s the OG millennial influencer pro climber,” Wright says.

But social media work comes at a price. The film discusses her struggles with her body while operating both as a performance athlete and as an influencer. DiGiulian describes her experience of being an 18-year-old 94-pound comp climber with body dysmorphia and then, gradually, finding comfort in her own skin. She talks about the criticism she received from an Agent Provocateur campaign, where she climbed in lingerie to show a correlation between strength and femininity. The film also examines the fat shaming she experienced online, though the film avoids naming Joe Kinder and the specifics of the event.

Though DiGiulian does note that this “was an incredibly traumatizing period,” the fact that the cyberbullying occupies a mere three minutes of the film might leave some viewers might be left to wonder just how much these things have affected her. Lynn Hill, however, notes that, DiGiulian is “really good at compartmentalizing her emotions,” saying that she was shocked to observe a calm, young DiGiulian giving a slide show not long after the death of her father in 2014.

The film delves a little into the negative impacts of DiGiulian’s relentless drive, however. During one of her attempts on Pico Cao Grande, a volcanic plug on Sao Tome, an island south of Nigeria, DiGiulian rips off a large section of rock, which nearly hits her photographer. After that, the team questions her motives and her acceptance of risk for others. After nonstop rain, DiGiulian and her partner, Angela VanWiemeersch, reassess their objective and bail, one of the few retreats in DiGiulian’s long career.

As with her struggles with social media and body image, her climbing failures and difficulties are only briefly portrayed, but candor leaks into the film.

“I feel like with every big thing she’s done, there’s always a weird asterisk,” Alex Honnold notes early in the film, referring to the significant scrutiny that DiGiulian’s ascents have seen from the climbing community.

After her 2021 ascent of Logical Progression, a long multi-pitch bolted route in Chihuahua, Mexico, DiGiulian posted on Instagram that her partner didn’t successfully free one of the crux pitches and that DiGiulian top roped it, which adds a small asterisk to the ascent. Drama has also surrounded DiGiulian’s first female ascents, as with a public tiff in 2014 (detailed in an Evening Sends article) she had with Nina Caprez over which one of them should have the right to rig and film the first female ascent of Orbayu, a 5.14 big wall on Spain’s Naranjo de Bulnes. While the film alludes to another controversy on the Eiger, it glosses over the details.

In addition to the Lynn Hill partnership, the film also focuses on DiGiulian’s experience with chronic hip dysplasia, for which she underwent five surgeries in 2020. She had planned for Logical Progression to be a last hurrah before the surgeries, but before she could arrive, Nolan Smythe, one of the film crew riggers, died while fixing ropes for DiGiulian’s team. The death caused DiGiulian to retreat from the climb and instead push forward with her hip surgery. She struggled through her recovery, fixating on getting back on rock and returning to Logical Progression. “She needs something that’s just on the ragged edge of insanity,” her partner Erik Osterholm said of DiGiulian’s drive to get back to her pre-surgery objective. Her dedication saw her back to Mexico and up the route.

“Here to Climb’s” arc moves quickly through DiGiulian’s problems, offering a superficial glimpse into what drives her. That’s easy criticism, though. It both minimizes the film’s breathtaking climbing footage and doesn’t do justice to the fact that DiGiulian speaks with vulnerability about her career. All in all, it’s an enlightening look at professional climbing.

Ricki Stern and Annie Sundberg directed the HBO sports documentary Here to Climb from Red Bull Media House. The film debuts Tuesday, June 18 at 9pm ET/PT on HBO.

The post Sasha DiGiulian Gets Surprisingly Candid About Career in New HBO Film appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

The rope solo record on the notoriously slow ‘Salathe Wall’ was just shy of 20 hours. Honnold did it in 11.

The post Honnold’s Yosemite Partners Bailed. So He Smashed the ‘Salathé Wall’ Speed Solo Record. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

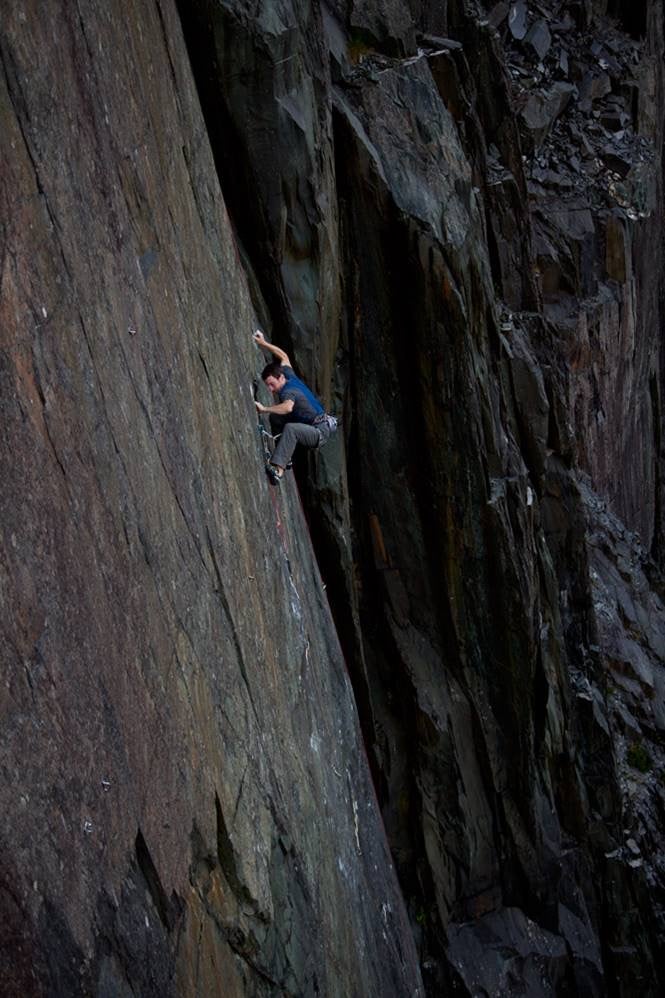

“I was only in the Valley for a week,” Alex Honnold said of his recent trip to Yosemite National Park. He’d gone there without his family, hoping to refresh his wall climbing skills on Mount Watkins, but when all his partners bailed, he resorted to smashing the speed record on El Capitan’s Salathé Wall (5.13b, 3500ft) instead. “No better time to rope solo than when all your partners have left you.”

Located on the southwest face of El Capitan, the Salathé Wall climbs a long slab section called the Freeblast into a series of wide and physical cracks, followed by an immaculate headwall. The 35-pitch route covers approximately 3,500 feet of terrain. Royal Robbins, Tom Frost, and Chuck Pratt made the route’s first ascent in 1961; Peter Haan made the first roped solo ascent in 1972; Todd Skinner and Paul Piana made the first team free ascent at 5.13b in 1988; and Alex Huber made the first individual free ascent in 1995. While the route now serves as the standard free climbing route on El Cap, this spring it became a race track for rope soloing.

Unlike its neighbor, the Nose, where intense competition has pushed the current speed solo record down to 4 hours and 37 minutes, the Salathé has seen just a few fast rope solo ascents in its lifetime. In 1992, Steve Schneider set the record with a 21:42 time. In 2013, Cheyne Lempe broke it with a time of 20:06. In early May this year, Byran Hansell rope soloed the route nine minutes faster, climbing it in 19:57. Then on May 17, Jordan Cannon attempted to set the record and was making good time but got stuck behind a party on the Enduro Corner/Headwall. He ultimately topped out with a 21:30 time. Seeing that there was a race for the Salathé rope solo speed record, the ever-competitive Honnold jumped in.

“I don’t love it,” said Honnold of rope soloing. “I kind of hate it actually. But it’s a useful skill to have.”

Nearly nine hours faster

To retune his speed climbing game for the Salathé, Honnold first climbed the Nose with Connor Herson earlier in the week. Then he poured through Brent Barghahn’s blog learning as much as he could about rope soloing. He took a day to practice what he’d learned, climbing up to the Hollow Flake (pitch 13). (“I was basically freeing the Freeblast while rope soloing so I could learn how to do it,” Honnold said.) After a rest day working in the valley, he got up early and walked to the base of the Salathé Wall at first light with a double set of cams, a few offsets, and a backpack.

He rope soloed the Freeblast, the difficult flare of pitch 19, the Boulder Problem pitch, the Enduro Corner, the pitch to the headwall, the headwall, and the pitch above the headwall. The rest of the time he used a combination of daisy soloing, free soloing, and using a rope for short sections. He made it to the Block in just six hours, which is approximately 900 feet from the top, but then his climbing slowed down.

“The Enduro Corner and the Headwall just take a long time,” Honold said.

He passed two parties on the Hollow Flake and one in the Alcove. “There was a party up on the Headwall as I was climbing that I thought I was gonna catch but I never managed to. I was like, ‘Aww man I can’t even catch a wall climbing party.’ ”

Despite this, he still shaved eight hours off the previous rope solo speed record, finishing in a blisteringly fast 11 hours and 18 minutes.

Even though Honnold’s preparation for the ascent sounds pretty minimal, and even though he’s characteristically nonchalant about the significance of his time, it’s worth noting that he has done extensive prep work over the years—including climbing the route numerous times. He first freed the Salathé over three days in 2007. Two years later, he free climbed the route in a day, nearly linking the entire headwall in a single pitch (which goes at 5.13d when enchained) but falling at the last boulder problem. He then redpointed the second headwall pitch on its own. Later that same year, he set the Salathé speed record at 4:55 with Sean Leary.

Beyond his time on the Salathé, Honnold also held the solo speed record on the Nose from 2010 to 2023, and he soloed the Nose, Half Dome, and Mount Watkins in a single day in 2017. “Doing those, I never actually rope soloed whole pitches though,” Honnold said. Instead, he’d daisy solo or protect himself with a rope for short sections. “Maybe I should call it free solo plus.”

He also free soloed Freerider, which shares 90% of the terrain of the Salathé, in 2017. Rope soloing the Salathé is quite different though. “Free soloing the Freerider takes years of preparation whereas with rope soloing you can just go up there and do it and feel relatively safe. I read like three blogs and 27 links, watched a YouTube video, and was like ‘I got this.’”

Still, he doesn’t love the logistics involved in rope soloing. And on the day he soloed the route, he was tempted to go bouldering with a couple of friends instead. But ultimately he thought, “If I left the family for one week to come to Yosemite, I should probably go climb El Cap.”

Plus, the rope soloing gave him the opportunity to catch up with the innovations being made in the rope soloing game, particularly by Brent Barghahn’s Avant Climbing.

Honnold didn’t quite use any of the new gadgets, belaying himself with an unmodified Gri-Gri but it seemed useful for him to learn about.

“There were a bunch of things that I could have done better but that’s kind of the point,” Honnold said, before speculating that the record could be shaved down further. “I’m sure that the right person willing to really go for it could probably do six or seven hours.”

That said Honnold doesn’t think the time will drop as far as it has on other routes on El Cap. “It’s a long route,” he said. “And it’s more involved than the Nose with all the chimneys and stuff. It’s a grind. There’s no easy way to do the Hollow Flake.”

Related: An Incomplete List of Alex Honnold’s Less Famous Badassery

The post Honnold’s Yosemite Partners Bailed. So He Smashed the ‘Salathé Wall’ Speed Solo Record. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

While James Lucas was working on the new Bishop guidebook, he put together a list of Bishop’s best highballs at every grade up to V10. Pad these climbs carefully—or better yet, don't fall.

The post The 10 Best “Moderate” Highballs in Bishop appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

In the 1940s, mountaineer Smoke Blanchard played a high-stakes game of “the floor is lava” in the enormous desert stonescape outside Bishop, California. He coined the term “Buttermilking” to describe the moves that he performed, jumping between the boulders, jamming up the cracks, manteling onto towers, and linking together large sections of terrain without ever touching the gravel.

From Blanchard’s days to the 1980s, climbers continued to Buttermilk. They maintained a soloing mentality, only going as far up as they could comfortably downclimb, thinking of their game as fun practice for big-mountain terrain. In the 1990s climbers began pursuing the lines in the Volcanic Tablelands and the Buttermilks as more than mere training climbing. Seeing bouldering as an end unto itself, and emboldened by the introduction of crashpads, they extended the bouldering mentality onto ever higher lines.

Blurring the line between bouldering and free soloing, Bishop’s beautiful highballs now attract climbers from across the globe. As the problems have gotten taller, so have the pad stacks and the prevalence of gritstone-style toprope rehearsal and headpointing tactics.

With thousands of climbs in Bishop, picking the best can be difficult. But while I was working on the new Bishop guidebook—it hits the shelves this month and is now available for pre-order—I combined my years of experience climbing in the Buttermilks with input from locals and the history of the area to create a list of Bishop’s best highballs. Pad these climbs carefully and be mindful that you may find yourself in some proper Smoke Blanchard-style Buttermilking.

The most Classic Bishop highballs from V0 to V10

Southwest Arete (V0)

Location: Buttermilks, Grandma Peabody

It’s rare to see pads underneath this line even though it’s the easiest way up the gigantic Grandma Peabody. Most people forgo pads because it’s more of a free solo than a highball. The Southwest Arete tackles some footwork intensive terrain all the way to the rounded slab at the top. It’ll be properly terrifying if you don’t trust your feet.

Heavenly Path (V1)

Location: Happies, Heavenly Path / Main

Located in the center of the Happy Boulders, Heavenly Path follows a series of large undercling features to a committing move that leads to an easier but heady chocolate slab. Though moderate, this climb has claimed a few broken backs and sprained ankles—thanks to both its height and the protruding rock near the base.

Sheepherder (V2)

Location: Buttermilks, The Loaf

The Loaf Boulder appears to be unassuming, with a few crimpy lines on its left side, but Sheepherder tackles a right trending series of delicate smears in the center… and it gets rather tall. Staying challenging throughout, this low-key Buttermilks classic rewards a calm head and keen footwork.

Black Magic (V3)

Location: Happies, Black Magic / Blood Simple

Mick Ryan’s old Bishop Bouldering Survival Kit pamphlet listed this impressive 30-foot climb as V5. Better beta and larger pads have lowered the grade but not the height. The crux comes low but heady high moves and a little suspect rock keep this engaging to the end.

Jedi Mind Tricks (V4)

Location: Pollen Grains, Jedi Mind Tricks

“It’s an easy warmup,” my ex-girlfriend assured me. The flake system sitting on the south side of this Pollen Grains bloc gets a lot of sun, making it perfect for cloudy days. But if you climb it in the sun, as I tried to do, the problem may be more of a warm climb than a warm up—especially since the problem escalates in difficulty the higher you get, culminating in a hard move at the top. It’s no wonder the relationship didn’t last.

René (V5)

Location: Happies, Hand to Hand / Rene

“The wall has a clean angle change in the middle—from slabby to slightly overhanging—that gives it a nice, imposing lean,” said first ascensionist Victor Copeland, who originally thought this line was V9 or 10. After he crimped more at Indian Rock, he lowered the grade. Though he was still drawn to it. “The tiny holds, with an exciting deadpoint to the lip at enough height, give the finish a dramatic, cruxy feel.”

Atari (V6)

Location: Happies, East Rim/Atari

Named after the late ’70s video game council, this problem involves squeezing up an Atari-shaped double prow above a bad, tiered landing. While not as tall as many of the other problems on this list, a bad fall on this could be worse than many of the bigger lines. Still, it’s an absolute classic—and one of the most photogenic problems in the United States.

Pre-order James Lucas’s Bishop Bouldering here

Mesothelioma (V7)

Location: Pollen Grains, Beekeeper

“It’s V4,” Bishop local Andy Liu told me before I tried his amazing arete. He was right…almost. Some V4 moves at the start lead to a V4 section in the middle and a very engaging V4 section at the top—which makes the whole ensemble… not V4. Be warned: the easiest way off is a heady V2 downclimb.

Highbrow (V8)

Location: Happies, West Rim/Highbrow

Sometimes bouldering requires having friends and a lot of them. The prow of Highbrow, which features difficult squeezing in a wild position high on the west rim of the Happies, requires a ton of supportive partners—though even with them you should be prepared for some equally wild falls on this aesthetic climb. Supplement your pads and spotters with a careful blend of confidence and good judgment.

Fall Guy (V9)

Location: Buttermilks, Flyboy Boulder

How long can you make difficult pulls on tiny edges? If you want to find out, test your fingers on this power-endurance crimping test piece. If you want more, Haroun and the Sea of Stories, begins a few moves lower.

Golden Shower (V10)

Location: Pollen Grains, Beekeeper Boulder

Though mega-tall lines like Too Big to Flail are what people think of when they think of Bishop highballs, these are also more like free solos than traditional boulder problems, so the comparatively “diminutive” Golden Shower makes the cut at half the height. This line tackles an amazing arete and culminates with an airy heel hook and some thank God buckets above the lip.

Pre-order James Lucas’s Bishop Bouldering here

Related: Flood in the Desert: How Tidal Wave of Climbers is Reshaping Bishop, California

Other tall Bishop classics

V0*

Natural Melody (V0-)

Celestial Trail (V0-)

Althea (V0)

The Pursuit of the Wow (V0)

Southwest Arete (V0)

Big Slab (V0+)

*Be warned: the difference between V0- and V0+ can be the difference between 5.8 and 5.10.

V1

The Black Stuff

Heavenly Path

John Bachar Memorial Problem

Blood Kin

Good Morning Sunshine

V2

The Hunk

Sheepherder

Fire Pit

Timothy Leary Presents

V3

Black Magic

Roadside Highball

East Rib

The Bee Sneeze

The Hard Crack

Scooped Face

V4

Professional Widow

Green Hornet

Grommit

Jedi Mind Tricks

Cuban Roll

Professional Widow

My Heart Grew Wings Under Desert Skies

V5

Strength in Numbers

Done with the South

Rene

Finger Prints

V6

Atari

Drone Militia

The Ninth

The Beekeeper

V7

Los Locos

Lawnmower Man

Mesothelioma

Suspended in Silence

Secrets of the Beehive

V8

HighBrow

Magnetic North

Water Saps

Flight of the Bumble Bee

V9

Saigon Direct

Luminance

Fall Guy

Hueco Wall

This Side of Paradise

V10

Too Big to Flail

Golden Showers

The post The 10 Best “Moderate” Highballs in Bishop appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

It’s easy to think that we can look after our pets’ needs at the cliff, but, in reality, we can’t.

The post Why Pets Don’t Belong at the Crag—Ever appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Wesley, a mohawked Labrador-chow mix, chased my red Saturn station wagon as I drove down Buttermilk Road. It was winter 2010, and I was housesitting in Bishop, California, for Wesley’s owner, taking the 70-pound dog to the boulders and then “walking” him afterward—OK, redneck-running him. Being at the boulders with me four days a week helped Wesley stay fit and happy. Wagging his tail behind me, he’d spend his days doing dog things—sniffing, running around, sleeping. Nine years ago, the Buttermilk Boulders were empty, and it felt reasonable to have an off-leash dog. Today, with the crowds, it would be chaos.

Though friendly, Wesley liked to wrestle with other dogs. This created a few fiascos in the small canyon of the Happy Boulders, but it was less of an issue at the more-open Buttermilks where Wesley often joined a dog pack that dashed from one end of the boulder field to the other, chasing each other or tearing after rabbits, getting into dust-tornado-forming fights. At times, other dog owners complained about Wesley’s rowdiness, but I brushed off their criticism. Spot pooped just as much at the Tableland Boulders, and I’d seen Mr. Peanut Butter steal lunches and chew climber shoes below High Planes Drifter. How was Wesley any worse? Dogs, I thought at the time, belong at the rocks—even rowdy ones like Wesley.

I was in denial.

It’s easy to think that we can look after our pets’ needs at the cliff, but the reality is we can’t—the rugged, often-crowded venues make it nearly impossible. “That was the worst belay of my life!” Hayden Kennedy griped in 2009 after I lowered him off Omaha Beach, a 5.14a out the Madness Cave in the Motherlode, Red River Gorge. I couldn’t deny that I’d short-roped him three times, once for every time a pack of four unattended dogs ran around my feet. The owners had let their hounds play wildly, fighting at the crag base, making it hard to focus. I neglected to say anything, given that the owners were already the type of clueless/inconsiderate people who let their dogs cause chaos at the crags, so would probably have said something defensive like: “They only get aggressive around people wearing climbing shoes because of crag trauma as puppies”—or just get indignant. And I worried that by complaining I’d just come off as some animal-hating sociopath who strangled puppies and punched kittens.

The same winter that Wesley roamed the Buttermilks, Gus, a prize-winning show pug, followed dutifully behind Cedar Wright on the 25-minute hike out from the Monastery in Big Thompson Canyon, Colorado. Cedar fell into a bolting argument with his partner, and then looked behind him only to see that Gus had disappeared. Gus—all 15 pounds of him—spent a week in the Colorado alpine, eating berries and hiding from predators. He eventually found his way to a nearby porch, 15 miles from the Monastery, escaping the epic and bumping his Instagram account to 14.6k followers.