Climbing poorly won’t ruin your reputation. Pooping like an amateur absolutely will.

The post Never Poop on a Belay Ledge and More Key Bathroom Beta for Climbers appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

In the 12 years I’ve been climbing, I’ve heard countless stories about gastrointestinal emergencies. I’ve told a fair number of them myself—from that time a friend and I both got sick and had to pass a single W.A.G. Bag back and forth for 13 hours on a ridge traverse, to that time I pooped my pants in an offwidth in Eldorado Canyon. Now that I’m 32, I’ve realized two things: Poop stories are still very funny (sorry, Mom), and there’s actually no such thing as an emergency—just a lack of preparedness.

The proliferation of human waste is a serious issue that threatens access to climbing areas across the U.S. It’s also just plain gross. The good news is that, with the right kit and a little know-how, it’s an entirely preventable problem.

Here are our favorite tips, tricks, and gear for responsibly managing your human waste across the major climbing disciplines. I also offer tips on how to use the loo in arid, remote, and wintry environments.

A climber’s guide to pooping and peeing, by discipline

Cragging and bouldering

Crags and bouldering zones with short approaches tend to draw the greatest concentration of human traffic. This means it’s extra important that we all remain on our best behavior. Here’s what that looks like:

- Use the trailhead toilet. An actual toilet is your first line of defense, especially if you’re in a crowded area or fragile environment. If it’s a long walk, embrace the extra exercise.

- Dig a six-to-eight-inch hole. Digging “cat holes” works if you’re in a forested area with deep soil. I like the PACT Outdoor Bathroom Kit ($50), which comes with a shovel, just-add-water wipes, and mushroom capsules that speed up decomposition. (Reminder: Pack out the wipes and any TP. Contrary to popular belief, these items can take up to three years to decompose.)

- Carry a W.A.G. Bag. The ubiquitous W.A.G. Bag (short for “Waste Aggregation and Gelling”) is a disposable, odor-proof, leak-proof plastic pouch. Fill it up, pack it out, and toss it at the first gas station you hit on the way home. Pro tip: Local climbing organizations, climbing stewards, and ranger’s stations often pass them out for free.

Follow Leave No Trace guidelines whenever possible. Pack out all your toilet paper, wet wipes, pads, and tampons, and try to pee at least 200 feet off-trail and away from water sources.

Pro tip: Always try to use the bathroom before getting your knee hopelessly in an offwidth, as this classic climbing clip demonstrates:

Multipitch climbing

This advice can be summed up rather succinctly: Do not shit on a belay ledge. Hold it, poop into a Zip-loc, carry a W.A.G. Bag—I don’t care what you do. Just don’t drop your payload on the one place climbers are forced to hang out for hours at a time. If your partner is on the ledge beside you and you’re feeling shy, tell them to close their eyes and sing loudly. It’s a good bonding exercise. Trust me.

Peeing is a little more free-form. Try not to urinate in cracks (they’ll stink forever) or directly onto the route. But anywhere else is generally fine. Ladies, here’s some useful gear to make that easy (even with a harness on):

- Freshette Reusable Pee Funnel ($22.95)

- Kula Cloth ($20)

- Gnara Go There Pants ($168)

Big walling

In the olden days, Yosemite climbers were known to throw used W.A.G. Bags off the wall into the valley below. Later, climbers carried up sections of PVC pipe that they stuffed with used W.A.G. Bags. These “poop tubes” were relatively reliable—but prone to cracking and exploding if dropped. These days, the go-to vessel for multi-day waste containment is a soft-sided haul bag. The most popular of these is the Metolius Waste Case, according to Sam MacIlwaine, a former Yosemite Climbing Steward and Climbing associate editor.

“You hang it at the bottom of your chain of haul bags so you don’t have to smell it,” MacIlwaine says. Most people are pretty generous in sharing Waste Cases, she adds. If you don’t have one, you can typically borrow from a friend.

The unspoken rule is that if you spill your excrement, according to MacIlwaine, is that you must pause your objective until the wall is, well, poop-less. “You have to clean it. If you don’t, it will destroy your reputation in the valley forever,” she says (and she’s not exaggerating.) A few of MacIlwaine’s other tips for big wall bathrooming:

- Use a harness with detachable leg loops. That way you can make a deposit without unclipping.

- Pull the ropes up before peeing. Also pay attention to the direction the wind is blowing.

- Wait til your partner—and any other parties—are above you. Or at least on the ledge next to you. If someone’s beneath you, hold it.

- Keep tampons and wipes in a fanny pack. The top of your haulbag also works. Just make sure your period kit is accessible. Also bring a zip-top bag to pack out used tampons and wipes. These can go in the Waste Case when you have access to it next.

- Don’t drop trou in Yosemite between 12:30 and 4:30 pm. That’s when the high-powered telescopes are out.

How to responsibly dispose of waste, by climbing environment

Desert

The desert is a complicated place to use the bathroom for several reasons, the foremost of which is that things don’t really decompose. The environment is too arid. Anything you leave on or in the sand is more likely to get mummified—and therefore become a lasting monument to your irresponsibility—than to peaceably disintegrate. Plus, bushwhacking around and digging holes disturb the fragile cryptobiotic soil that desert life relies on. Shitting on-trail is a no-no. And shitting off-trail is even worse.

The third problem is that if you forget TP, there’s nothing much to wipe with. Except cactus. The fourth problem is that desert crags and towers are often remote, and bathrooms are hard to come by.

Once, while climbing Castleton Tower about a decade ago, I started to experience hints of gastrointestinal distress on the second pitch. By sheer force of will, I managed to reabsorb and carry on. Then, almost as soon as we rappelled back to the base, my partner decided it would be a great idea to climb the tower again via a different route. My belly wobbled, but all I had with me was a bagel bag. So, I puckered up and nodded reluctantly. By the time we got to the base the second time, the situation was code-red. Out came the bagel bag.

Aiming was no easy feat. The sandy rocks I elected to wipe with (and pack out) left me chafed for weeks. My advice to you? Bring a W.A.G. Bag every time you go climbing. Bring a lot of them. One per person per day is the general rule—unless you want to share.

Alpine

Like desert environments, landscapes above treeline tend to be bereft of moisture. Human waste can take years—if not decades—to break down. The soil is thin and rocky, and digging holes is next to impossible.

For those reasons, leaving waste in the alpine is typically a huge faux pas, especially in places with high visitation like Mount Whitney or Rocky Mountain National Park. There are a few exceptions in truly remote ranges where the brown falcon method is considered acceptable (for the uninitiated, this involves shitting on a flat rock, then frisbeeing it into the void). I once had a guide recommend the ol’ smear-and-throw during a Backpacker Editor’s Choice Trip in Colorado’s Weminuche Wilderness. We were at 14,000 feet, surrounded by miles of talus. He said a single lone turd wasn’t likely to have much of an impact.

That said, I pretty much always bring a W.A.G. Bag, even if I’m way out in the boonies. Altitude does strange things to the digestive tract, and you never know when you’re going to need it.

Finally, piss responsibly above treeline. Marmots, mountain goats, and other high-altitude critters are desperate for salt and will attack anything you’ve peed on. They’ve also been known to eat sweaty backpack straps and chase urinating hikers. In goat country, have a friend stand watch. Then, pee on rock rather than plant matter. That way, the goats will get their fix licking stone, rather than unnecessarily pawing up native vegetation.

Snow and ice

It doesn’t matter whether you’re alpine climbing, ice climbing, or mixed climbing. If there’s snow on the ground, digging holes is useless. Nothing is more horrifying than watching the onset of spring leave dozens of melted-out turds on the surface of god’s green earth.

If there’s a toilet nearby, use it. If not, it’s time for a W.A.G. Bag. Pro tip: Snow makes excellent wiping material. The color allows you to reliably monitor progress, and the temperature is, well, refreshing.

The post Never Poop on a Belay Ledge and More Key Bathroom Beta for Climbers appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Anxiety about falling is normal, no matter how long you’ve been climbing. Here’s how to deal with it.

The post How to Conquer Your Fear of Falling (Even in the Gym) appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Anyone who tells you they’ve never been scared to take a climbing fall is lying. Falling is scary. It’s scary for beginners and lifelong experts alike. Over my 10 years writing about climbing, I’ve interviewed pros, coaches, and mountain guides who have all confessed that they still get scared to fall from time to time. Even these experts work diligently to keep that fear in check. Hell, I have to re-teach myself how to fall at the start of every season—no matter how fearless I felt just months before.

“100% of climbers could do with working on their head game,” says Kevin Roet, author of Climbing Psychology and owner of UK guiding outfit Rise and Summit. The human brain isn’t wired to love leaping from great heights. Being afraid to fall is very normal—and very human.

Some people feel embarrassed to be scared of falling in the controlled environment of a gym, but it happens all the time. Whether you’re bouldering, leading, or even toproping, you can still get scared indoors. The good news is that fear isn’t something you’re stuck with, even if it feels insurmountable now. If you do the work, you can chip away at this anxiety until it’s something you barely think about.

Now for the bad news: While we all love a quick fix, there’s no single drill, mantra, or breathing technique that’s going to banish your fear for good, says Roet. That’s because fear looks different for everyone.

To start working on your particular brand of falling fear, you’ll need a few ingredients: 1. a clear idea of what scares you, 2. an understanding of your fear threshold, and 3. a plan for working through that fear piece by piece.

Identify your stressors

First, figure out what scares you about falling in the gym. Are you afraid of getting hurt? Of the rope breaking? Of embarrassing yourself?

If fear of embarrassment is the primary stressor, try climbing with someone whose opinion you don’t care about. Find a partner who’s at or below your ability level, or someone who isn’t your mentor or significant other. It might also be helpful to reevaluate why you climb. If you’re putting too much pressure on yourself, figure out where that pressure is coming from.

Are you afraid of getting dropped or spiked into the wall? You may want to switch belayers. Even if your regular climbing partner is pretty competent, getting belayed by a coach or expert can be an incredible way to develop trust with the training wheels on, says Roet. Most gyms offer a learn-to-lead class or instructors you can book a one-on-one clinic with.

No matter the source of your fear, be careful not to judge yourself or apply any moral evaluation. Don’t tell yourself that your fear is silly, or that you “shouldn’t” be afraid of falling in a gym.

“What causes stress for one person versus another is highly personal,” says Roet. “One person might perceive sitting on the rope to be stressful. Another person might be happy to fall below a bolt, but find that falling from above a bolt is difficult.”

Understand your fear threshold

Roet breaks fear into three zones. At the low end of the scale, there’s the stress-free zone. This is perfect calm. You’re on the ground, you’re happy. Maybe you’ve got a donut in your hand. That’s Zone 1.

“The next zone is the learning zone. This means you have an exciting and manageable level of stress,” Roet says. In Zone 2, you’re engaged and you might feel a little nervous, but you can still think straight. You’re able to absorb information, and you’re more or less having a good time.

At the high end of the spectrum, there’s Zone 3.

“This is the panic zone, and you don’t want to be there,” Roet says. Panic is redlining—you’re sweating, you’re breathing fast, your heart rate is high, and you’re spiraling. You can’t absorb advice or think clearly. Some people feel frozen in place. Others feel frantic.

Some climbers like the idea of pushing themselves to their limits. They assume that more challenge—and therefore more stress—will accelerate their progress. It’s especially easy to get caught up in this in a gym setting when you’re surrounded by other people training hard; it’s easy to compare yourself to everyone else. However, Roet says, when you push yourself too hard and cross the threshold into the panic zone, you’re actually going backward.

“Once you get into panic, you’re going to start to associate negative feelings with climbing,” he says. The result is a trauma response, which will actually trigger more stress the next time you think about falling.

If you want to overcome your fear, try to keep your stress levels comfortably in the learning zone, even if that means you can only dial up the stimulus by a hair at a time. Don’t worry about what anyone else in the gym is doing. Baby steps are better than negative progress.

How to spot the fear coming

If you’re not used to tuning into your emotions, you might not notice your stress levels inching up until you’re in full-blown panic mode. That’s how I started out. I often found myself in the middle of a freak-out, blindsided by a wave of panic I never saw coming. But even if you didn’t perceive it, there’s always something that triggers fear.

Next time you get scared, try this: “Sit on the rope, and take the time to be quiet and close your eyes,” Roet says. “Try to think back. What are you feeling? What thought process did you just have? It’s like creating a comic strip. Try to go back to that first picture. What was it? Did you tell yourself something was scary? Did you look at the bolt below you and start thinking about how high up you were?”

Visualize your fear

I started trying this comic strip exercise a few years ago. At first, I couldn’t imagine what any of the pictures in my metaphorical comic strip might be. But after a few months of practice, it got easier to piece things together.

It’s sort of like remembering your dreams. When you start out, you wake up and don’t remember a single image. But over time, if you think about your dreams enough mornings in a row, you’ll start to remember snippets, then whole sequences. It takes practice, but it works.

These days, I’ve been doing the comic strip drill for so long that I know exactly what set me off as soon as I start to feel nervous. Usually, it goes something like this: I look down between my feet, I spot my last bolt far beneath me, and I start thinking about falling. Then I remember that time my buddy broke her ankle, and I began to panic about hitting all manner of nonexistent things below me.

As soon as I know how the spiral started, I can rewind the first half by refuting all the little stories I’ve made up in my head. I take a deep breath and start talking to myself: The bolt is right at my feet. The fall will only be a small one. I’m safe. I know how to fall. I have good technique. I’m at a good rest right now. These holds are good. I have lots of time. There are no ledges. My belayer has me.

Better yet, I now notice subtle changes in my mental state while they’re happening. This means I can nip them in the bud before they devolve into full-on panic. If I feel my heart rate rise even a little bit, I step down to the last rest and shake out until I feel calm enough to keep going.

Develop a plan to address your fear

The secret to working through fear is to take tiny, bite-sized steps. Come up with a drill you can execute in your local gym and do it consistently, week after week, for as long as it takes.

“Start easy. Start somewhere where you think it’s almost ridiculous,” Roet says. “If you’re afraid of falling on lead, for example, start by climbing up five or six clips, sitting on the rope, and coming back down.” Then take some falls on top rope or on the autobelay. Fall with the bolt just above you, then just at your waist, then an inch below your waist. Then two inches. You want your brain to be saying, “Good God, this is so ridiculously easy for me.” That’s the foundation on which to build confidence.

Increase the level of stimulus until you feel a healthy level of challenge. The difference between the “learning zone” and the “panic zone” might be just a single inch. That’s okay. When you’re at the upper end of the learning zone, stop for the day. End on a good note, and don’t overdo it.

“Also keep in mind that you might get used to one environment, but that doesn’t mean the stress levels will be the same somewhere else,” Roet says. Any time I go to a new gym or crag, I have to take some practice falls to recalibrate my brain. That’s incredibly normal.

Progress isn’t always linear, but there’s success in every session. Before you go home for the day, reflect on your successes. Maybe you took a bigger fall today. Maybe you didn’t. Regardless, you’re out here, doing something that’s hard for you. You’re putting serious effort into overcoming your fear of falling. That’s worth celebrating.

“Stay consistent,” Roet says, “And you will see progress over time.”

Watch avid gym climber Avianna Frady talk through her tips for managing your fear of falling at the gym, particularly when it comes to bouldering

The post How to Conquer Your Fear of Falling (Even in the Gym) appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Critical tips you probably won’t see in your gym’s FAQs section

The post Climbing at the Gym for the First Time? Here Are 7 Things You Should Know. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Here on the eve of your first-ever gym visit, you might find yourself nervous. What if, god forbid, you’re bad at rock climbing? What if it’s scary? What if you hate it—or, worse—like it, and then have to watch all your free time, money, and emotional energy spiral down the drain of all-consuming obsession?

If you have an addictive personality (like yours truly), beware: Climbing may be habit-forming. If you’d prefer to save your money for World of Warcraft figurines and keep your evenings and weekends free to rot in front of your television, then this is your last warning. Get out now, while you still can.

If you aren’t the obsessive type, then you have much less to fear. Climbing can be a thing you enjoy once a month, once a year, or once and never again. It can be a first date, a weekly fitness habit, a seasonal sport, a mid-life crisis, or an existential epiphany that you quit your job and move into a van for. There’s no one right way to approach it. But there are a few things you can do to make sure Day One goes well—no matter where you plan to take things next. Here are seven things you should know (that your gym probably won’t tell you).

1. Wear pants.

You’re about to spend 90 minutes whacking your knees into plastic holds. Pants are the best way to ensure your coworkers don’t make a lot of assumptions when you go back to work on Monday. Slim-fitting joggers or leggings are especially important if you plan to rope-climb. Basketball shorts may feel comfy on the court, but they tend to wad up in inopportune places under a harness.

2. You don’t have to go to the top.

You’re a grown-up, and no one can make you do anything. If you hate heights, feel free to call it quits halfway up the wall. This applies to boulder problems and roped climbs alike. If you’re tired and want to get down, feel empowered to do so. If your buddy tells you to keep going, reply with, “You can’t tell me what to do!” at the top of your lungs. In my experience, that tends to shut them up quite nicely. If you’re bouldering, simply jump off or downclimb whenever you feel like it.

3. No one is watching you climb (we promise).

It’s normal to feel self-conscious in a new setting, particularly if it seems like you’re the only one squealing and falling all over the place. But trust me: No one cares how bad (or good) you are at rock climbing. Everyone else is too busy working on their own equally pointless gym project, checking their biceps in the mirror, or wondering if that hottie from the front desk is working today. They’re paying zero attention to you. So go nuts.

4. You can use any holds you want.

At some point, friends, gym personnel, and total strangers will all try to tell you that you can only use holds that are “on route” (i.e., all of the same color). While staying on route is useful for dedicated climbers who want to work on progression, this doesn’t apply to beginners. You’re an adult (see rule 2), and climbing was designed to be recreational. To quote the ‘90s improv show Whose Line is it Anyway?, “The rules are made up and the points don’t matter.” So, if you really like the look of that pink hold, to hell with it—grab the thing and charge shamelessly onward.

5. The chalk is there for a reason.

Most gyms will sell or lend you chalk. Use it. Like climbing shoes (and Viagra), chalk is performance-enhancing. It will vastly improve feel and friction, and will help you go longer with less effort. Plus, everyone knows climbing is all about virtue signaling. And nothing says “Hey, I just went climbing!” like going to lunch with chalky handprints all over our clothes.

6. You don’t have to like climbing.

Plenty of people are obsessed with climbing. But the vast majority of people in the world aren’t. Don’t let your friends or significant other pressure you into falling in love with their sport. It can be their thing and not your thing—and that’s okay. If you don’t want to leave your comfort zone, try harder routes, or be “braver,” then don’t. Goof off and heed the sage advice of the late Alex Lowe: “The best climber in the world is the one having the most fun.”

7. Wash your hands—and your feet—after climbing.

You just spent the day touching the same holds as countless other germy adults with questionable hygiene. So wash your hands before heading out of the gym. And if you trusted your bare tootsies to the gym’s putrid rentals, give those feet a soapy scrub before you contaminate your street shoes. You’re welcome.

The post Climbing at the Gym for the First Time? Here Are 7 Things You Should Know. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

On March 18, Stylos became the first woman to send D15+/D16- with her redpoint of Parallel World, a Derak Sokolowsk king line in the Italian Dolomites.

The post Katie McKinstry Stylos Just Broke the Glass Ceiling for Women in Drytooling appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

There are a few reasons you may never have heard the name Katie McKinstry Stylos. For one thing, she’s relatively new to climbing, period; she didn’t touch rock until 2015 and didn’t start projecting hard routes until 2021. For another, her discipline of choice, sport drytooling, is incredibly niche. But within that niche—an incredibly powerful, gymnastic, and male-dominated sub-discipline of mixed climbing—she’s quickly become a tour de force, flying through the grades faster (and further) than any woman has before.

To illustrate: Stylos first started drytooling in late 2020. A little over a year later, she followed a climbing partner to Italy on a whim. They spent a few weeks at Tomorrow’s World, the iconic drytooling crag developed by the late alpinist Tom Ballard. On that trip, Stylos sent Edge of Tomorrow (D13), one of the cave’s most famous lines. (D13 is essentially an ice-free M13—a grade comparable to 5.13 in rock climbing.)

In 2023, Stylos came back and sent her first D14. The year after, she successfully redpointed Ballard’s A Line Above the Sky (D15). Line was the world’s first D15 and is still considered a global endurance test piece. Sending it was a big deal. But that was only the beginning.

On March 18, 2025, Stylos bagged Parallel World (D15+/D16), the cave’s hardest route. In doing so, she became the first woman in the world to climb the grade.

While her sends may seem to be firing off like clockwork, Stylos says the actual process has been anything but smooth.

“Parallel World pushed me to my absolute limits,” she says. In the process, she had to scrap almost everything she knew about projecting and rebuild her mindset from scratch.

Getting skunked

When she first arrived to try Parallel World in the fall of 2024, Stylos figured she’d make fast progress. Then she pulled on—and discovered that the line was nothing like what she’d envisioned.

For one thing, two of the holds were missing. For another, the moves were way bigger than she expected—many at the absolute max for her 5’6” height and 5’8” wingspan.

“Parallel World is a more interesting but significantly harder route than Line Above the Sky, ” says Chris Snobeck, who was the first American to climb Line and to climb both D15 and D15+. “It has some really long moves. When Katie started working on it, one of my big question marks was whether she’d be geometry-limited in not having a longer wingspan.” (Snobeck, it should be noted, has a tall frame and long arms. And more so than other climbing disciplines, drytooling tends to favor a longer reach.)

That first trip, Stylos spent eight weeks in Italy and failed to make much serious progress. Coming home, she felt like a failure.

“I had been really secretive about the route up to this point. I hadn’t told anyone what I was working on. I thought that it would leave me feeling less expectation from other people,” she said. “As it turns out, my expectations for myself were way too high. So I felt both crushed by them and completely isolated.”

When Stylos came home, she started opening up about what she was working on—and about her lack of success. Suddenly, there were people there to support her, both when things were going well and they weren’t. She also worked on her mindset, planning to approach the route with patience and curiosity rather than rigid expectations.

“When I went out to Italy in the fall of 2024, I wanted to send when I was ready to send,” Stylos says. “But it wasn’t ready to happen yet. I needed to wait, and to find peace with that.”

She also needed to totally overhaul her training plan.

Training overhaul

Stylos has always had superhuman endurance. Power? Not so much.

That winter, Stylos spent three months rebuilding strength and focusing intensely on her power endurance. She did four-by-fours, move repeaters, and linkups of limit moves with a 10-pound weight vest on.

She also replicated Parallel World as accurately as possible on the 12-by-12-foot woody her climbing partner Kevin Lindlau had built in the corner of Bozeman’s Mountain Project training facility. For a full month, she projected her replica.

“I can’t think of anyone else I’ve seen give that much commitment to a route,” Lindlau says. “Katie will stick to her training to a T. Even when some of us decided to do something at night and skip training the next morning, Katie wouldn’t. When she sets her mind to something, she puts 100 percent of her whole body and soul into it. She does not waver.”

For three months, Stylos was in the gym three hours a day, five days a week. To fit in a full workweek around her training, she worked seven days a week doing freelance graphic design all winter long.

Redemption

When Stylos went back to Parallel World this spring, she felt ready for anything—be that spectacular triumph or total failure. That approach, she says, made all the difference.

On March 18, Stylos trudged through the snow to the base of the climb, warmed up, and tied in. And for some reason, on that day, all the stars seemed to align.

She floated the first section of the route—a panel of heads-up D10 on poor-quality rock. The clips went smoothly. Her footwork was perfect. She made it to the roof within minutes.

There, she paused to shake out, because that’s where Parallel World starts to get real. All of a sudden, the angle kicks back and the rests disappear.

“From there, things get really thuggy and punchy—you’ve got these comp-style moves back to back to back and these huge cuts that strain your grip,” says Lindlau, who sent Parallel World a few years ago. “Then you just have to hang on through the middle section and keep going until it spits you out at this final boulder problem—a seven-move section that’s foiled all of us who have climbed it at some point or another.”

The boulder problem is burly and reachy, forcing the climber to do a full 360 on their tools to switch their grip and angle of attack. That kind of full spin is exhausting, as is using the tools in “reverse grip”—i.e. holding them backward to squeeze out an extra inch or two of reach. For Stylos, the moves were at her absolute limit. She had to cut feet, then reel them back in to reset for the final throw.

“That last move is one of the hardest on the route—it’s a huge deadpoint to a tiny hold that’s no bigger than a dime,” Lindlau says. “You have to swing to it—even after you’ve been climbing full-on for 30-plus minutes—and hope you hit it the first time.”

But on her send go, Stylos didn’t hit it the first time. Or the second. Desperately pumped, she had to reset yet again. Exhausted, nerves frayed, her whole body thrumming with adrenaline, she forced herself to breathe, one hold from the finish and almost within reach of the chains.

Don’t fall off here, she remembers telling herself. Don’t you dare fall off here.

On the third go, she stuck the move, hurriedly clipped, and lowered to the ground amid cheers. It was finally done.

A step forward for the sport

The send, Stylos says, is still sinking in—as is the fact that she was the first woman to notch the grade

“I hope that, by doing this, I can be the kind of inspiration to others that Angelika Rainier was to me,” Stylos says. “Angelika was the first woman to send Line Above the Sky. Getting to talk to her about it—and having a woman in the sport to look up to—that’s been huge for me.”

Lindlau says the send isn’t just a big deal for Stylos; it’s also groundbreaking for the climbing community at large, and especially for women in the burgeoning discipline of sport drytooling.

“It hasn’t been known if this route was possible for a shorter frame given that it has so many big reaches,” Lindlau says. “But now Katie’s proved it’s possible. Hopefully this is going to inspire more people to get out and try these big routes and not be intimidated by them.”

Snobeck adds that breaking this grade ceiling in Tomorrow’s World—often considered the global ground zero for hard drytooling—makes it all the more poignant.

“I’m so stoked for Katie. She has so much strength, motivation, and drive,” Lindlau says. “I can’t wait to see what she sets her mind to next.”

The post Katie McKinstry Stylos Just Broke the Glass Ceiling for Women in Drytooling appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

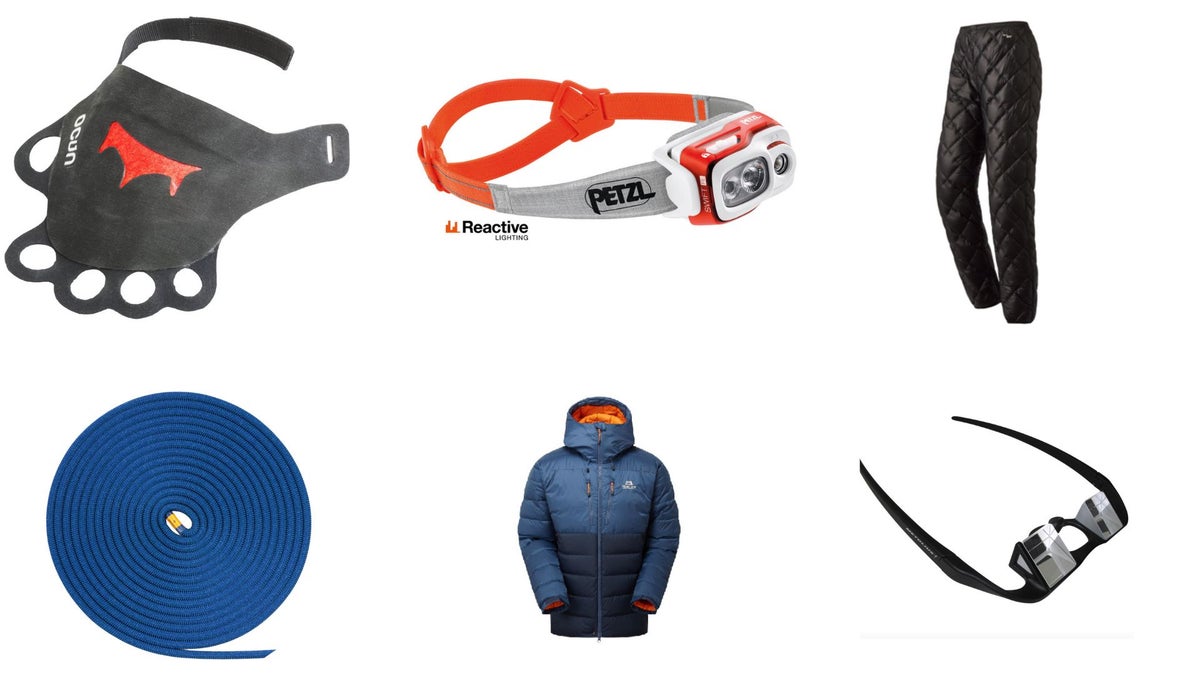

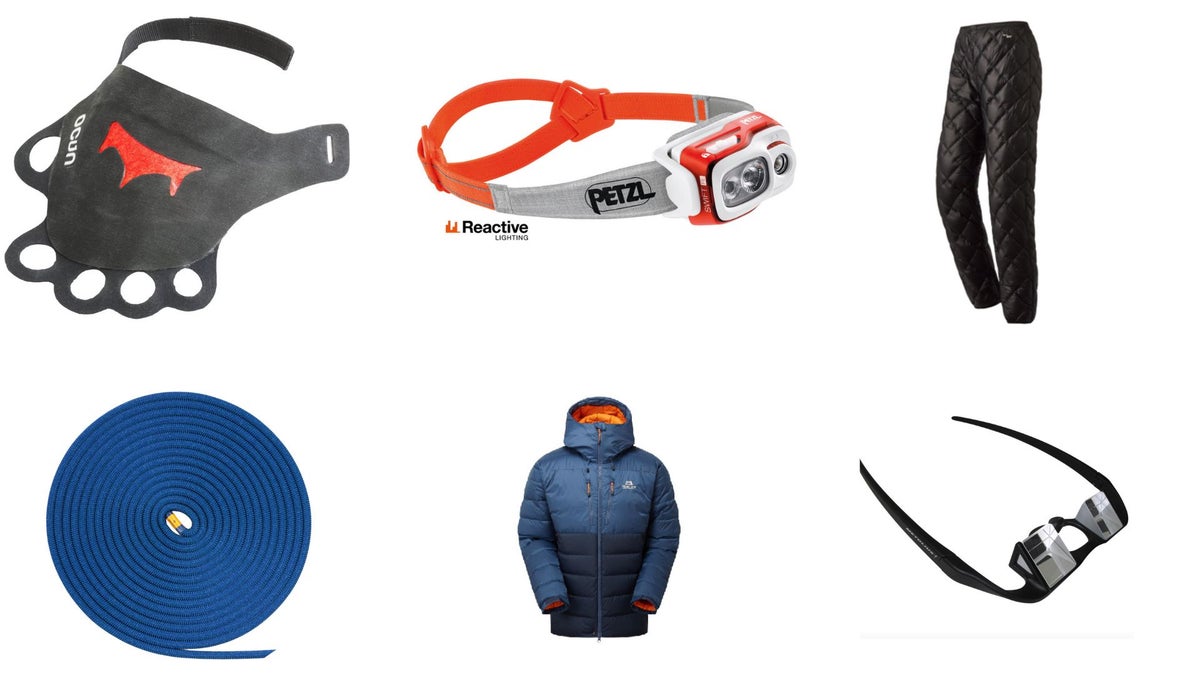

Five gear nerds tested 31 products, from carbon-fiber ice tools to top-of-the-line apparel. These six came out on top.

The post The Best Ice Climbing Gear for Your Next Winter Objective appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Ice climbing is a high-stakes sport. Do it right, and you’re in for a meditative cruise with just the right level of spice. Do it wrong, and you’ll be left spooked, shivering—or worse. The difference often boils down to your experience level. But right after that comes your gear. When you’re 100 feet off the ground, pinned to a silvery ribbon of ice by nothing but four blades of steel, you need absolute trust in your equipment. But how can you tell which products to rely on? That’s our job.

This season, we tried out 31 different pieces of ice climbing gear. Some turned out to be overengineered, overpriced, or poorly built. Others proved thoughtfully designed and dependable in a range of winter conditions. Over several months, dozens of miles, and thousands of vertical feet of testing from Colorado to British Columbia, we sorted out the latter. Those are the pieces below: the best new ice climbing gear for 2025.

At A Glance

- Black Diamond Hydra Ice Tool ($310)

- Scarpa Phantom Tech HD ($899)

- Trango Kestrel Ice Tool ($500)

- Patagonia M10 Hardshell Pants ($279)

- Petzl Sitta Harness ($175)

- Blue Ice Harfang Tech Crampons ($230)

- How to Choose Ice Climbing Gear

- How We Test

- Meet Our Testers

If you buy through our links, we may earn an affiliate commission. This supports our mission to get more people active and outside. Learn more.

Black Diamond Hydra Ice Tool

$310 at REI $310 at Black Diamond

Weight: 1.3 lbs (per tool, with pick)

Pros and Cons

⊕ Modular head weights

⊕ Ultra-sharp picks

⊕ Adjustable handle size

⊗ Geometry is isn’t aggressive enough for seriously overhung terrain

An impeccably balanced swing, ultra-precise pick, and a high degree of modularity make the Hydra a new category leader—and our tool of choice for both moderate and vertical ice this season.

For starters, there’s the head-weight system. Most tools come with just two options: weighted or unweighted, which let you adjust the weight of the tool’s head and therefore its swinging momentum. But the Hydra’s interchangeable head-weight system let us choose between two screw-on weights (either a 5-gram aluminum weight or a 40-gram tungsten weight) for each side of the tool. That’s three weight options total. That allowed us to dial-in our perfect balance for every kind of terrain. Between that and the razor-thin picks—just 2.5 millimeters wide at the tip, as opposed to the 3- to 3.5-millimeter industry average—these tools place like a dream. “They easily handled everything from a sketchy, thinly delaminated WI 5 pitch on Cody, Wyoming’s Mean Streak, to the steep, engaging features of Legal at Last (WI 6),” reported lead tester Maury Birdwell.

The Hydra’s handle is another highlight. A slight offset protected testers’ knuckles from bashes on bulging ice, and a durable, insulating rubber coating guaranteed a good grip. Testers also appreciated the optional handle spacers. “I used the Hydra with both thin dry-tooling gloves and with thick, three-finger mitts over a season of testing in British Columbia,” said Climbing digital editor Anthony Walsh, who took them out on a variety of different crags and ice flows. “I certainly appreciated being able to adjust the handle size to accommodate the difference.”

While this is an excellent all-around tool, some testers found the handle geometry insufficiently aggressive for moving through roofs or transitioning onto ice daggers, which Walsh discovered on the crux move of Dark Nature (WI 5+ M5/6) at Lake Louise, Alberta. Ultimately, we prefer the Hydra for steep, technical ice—but not for overhung mixed lines. Read our longform review of the Hydra here.

Scarpa Phantom Tech HD

$899 at Backcountry $899 at Scarpa

Weight: 1.75 lbs (per boot, size 42)

Sizes: Unisex 37-46 (half sizes); 47-49 (whole sizes)

Pros and Cons

⊕ Top-tier durability

⊕ Technical aptitude

⊕ Out-of-the-box comfort

⊗ Not quite warm enough for extreme-altitude objectives

We only thought Scarpa’s fan-favorite Phantom Tech boot couldn’t get any better. Then the Phantom Tech HD came along in 2023. The new boot offers the same level of climbing precision as the old version, but with more warmth, durability, and comfort—at just a 2.5-ounce weight penalty. Over an action-packed season in Colorado, Wyoming, and Canada, the Phantom Tech HD became our testers’ go-to for everything from overhanging mixed routes to steep, techy ice.

The improved warmth comes courtesy of a body-mapped insulation strategy. Micropile, aerogel, and PrimaLoft Gold Eco (a premium synthetic insulation with comparable insulating power to down) are strategically placed to prioritize warmth around the toes and ensure uninhibited articulation elsewhere. As a result, the Phantom Tech HD both kept our feet frostbite-free in negative 22 degrees Fahrenheit (albeit with vapor barrier socks) while ice climbing near Field, British Columbia, and ensured a natural, comfortable gait on long approaches. (That said, the warmth threshold ends around there; we wouldn’t quite trust these for spring or winter trips to Denali.)

“The rockered outsole has a trail-runner-like feel,” Climbing digital editor Anthony Walsh said, noting the grippy Vibram rubber and high-traction lugs. “And the clever, three-part lacing system makes it easy to isolate where I want my foot to be tightly supported.” The lacing system let us ratchet down our heels—boosting security and eliminating heel-lift on steep lines—without compromising toe circulation. “I’ve hiked and skied many miles in ice climbing boots over the years, and the Phantom Tech HD is without a doubt the most comfortable I’ve used,” Walsh said. And even after a full season of chimney scuffles, long boot-packs, and mixed climbing, our sample pair shows no signs of wear or delamination.

Trango Kestrel Ice Tool

$500 at Backcountry $500 at Trango

Weight: 1.0 lbs (per tool, with pick)

Pros and Cons

⊕ Light weight

⊕ Good impact-dampening

⊕ Moderate geometry ideal for vertical ice

⊗ Small handle size

⊗ Expensive

In the past, we’ve steered clear of carbon tools, which, though much lighter than aluminum models, often feel rigid and chattery, especially on hard ice. But the Kestrel was the first carbon-fiber axe that both lived up to its featherweight promise, and provided a comfortable swing. The secret is a Kevlar core, which provides a little more give than a traditional carbon shaft, dampening impact forces. “It swung fluidly,” said climber Seena Vali after a weekend of testing in Ouray, Colorado. He added that the handle felt surprisingly comfortable and grippy for a carbon tool, thanks to a textured paint that coats the shaft.

The picks each taper down to 3.5 millimeters, and the weight differential between the steel picks and the featherweight shaft is enough to keep the tool feeling balanced and powerful. As a result, the Kestrel offers an extremely precise swing, even without pick weights.

“With other carbon tools, I’ve had to adjust my technique to compensate for the rigidity,” reported category manager and ice climber Corey Buhay. “But this one hammered straight into the ice—perfect sticks every time.”

She added that the tool performed best on vertical to slightly overhanging ice, ideally WI 3+ to WI 5, thanks to the shaft’s moderately aggressive curve. On lower-angle routes, the sharp angle made swinging feel awkward. One other caveat: Large-handed climbers found the handle a little cramped with thick gloves on and would have preferred more room between the top and bottom pinky rest. But most testers loved the handle’s narrow diameter, which provided a more secure grip than some other tools we’ve tried.

Patagonia M10 Storm Pants

$279 at Backcountry $279 at Patagonia

Weight: 8.5 oz

Sizes: men’s XXS-XXL (the women’s counterpart is the M10 Storm Bib)

Pros and Cons

⊕ Surprising stretch and durability

⊕ Superior range of motion

⊗ No women’s-specific version

The M10 Storm Hardshell offers hands-down the best range of motion we’ve ever experienced in an alpine climbing pant. Thanks to a roomy fit, gusseted crotch, and slightly stretchy fabric—a mix of ripstop nylon, proprietary waterproof laminate, and a slick jersey backer—we were able to step high and wide without feeling constricted—a refreshing departure from the Euro-style, slim-fit trousers that have taken over the market in recent years.

“While transitioning from a panel of limestone to a hanging ice dagger, I stemmed my legs as far as I could between the two mediums and felt zero resistance,” reported Climbing digital editor Anthony Walsh. Some testers reported doing a full split just to test out the mobility. No torn crotches yet.

The rest of the layout is smart but simple. The thigh pocket, big enough to fit a smartphone, and fly are both positioned to remain accessible even with a harness on. “The zipper is on a diagonal rather than vertically-oriented like most other pants, so you can relieve yourself without a harness’s tie-in points or belay loop getting in the way,” Walsh reports. Elasticized cuffs keep moisture out—something we appreciated when spring conditions left our ice pitches streaming with water.

We loved how waterproof the M10s were, too. “I tested the M10s on some of the wettest pitches of my entire season,” said Walsh. “My ‘waterproof’ gloves soon wetted out, and my face had a steady drip of water coming off my nose, but under the M10 pants, I stayed 100 percent dry.” Credit goes to a lightweight, breathable, proprietary membrane and a PFCs-free DWR (durable water repellent) that boasted best-in-test longevity. After eight straight days of fighting up scrappy mixed lines in the Canadian Rockies, both the waterproofing and the fabric remained intact.

Petzl Sitta Harness

$175 at REI $175 at Backcountry

Weight: 9.7 oz (M)

Sizes: XS-L

Pros and Cons

⊕ Light weight

⊕ Superior packability and durability

⊗ Limited adjustability

⊗ Minimal padding

Our favorite packable harness for light and fast objectives, the Petzl Sitta crams all the features you need for hard ice climbing and mountaineering into a sub-10-ounce package. High-modulus polyethylene fibers reinforce both the leg and gear loops, providing enough rigidity to make this lightweight harness functional on the wall. Broad front gear loops (and three other accessory loops) fit a full rack of alpine gear, and two lateral ice-clipper slots kept our screws organized on WI 5 ice leads.

After months of testing on everything from overhung dry-tooling routes in Colorado’s Vail Amphitheater to steep ice and moderate mixed routes in British Columbia, we were impressed with just how little space the Sitta took up—about the size of a bike bottle—and just how much abuse it withstood. Neither knee bars, hip scums, nor beached-whale mantles were able to scuff the polyester and nylon materials, even while fighting up rough M6 chimneys in the Canadian Rockies.

While testers with larger thighs grumbled at the non-adjustable leg loops, category manager Corey Buhay preferred them. “I loved the streamlined silhouette for tricky ice and harder dry-tooling, where I generally want as few buckles and straps in my way as possible,” she said. The loops are also auto-balancing (the leg loops connect via a rudimentary pulley system rather than having two distinct straps). That means we never had to stand around picking at our butt straps to even them out.

While the spartan design had its benefits, we quickly discovered that the Sitta isn’t sufficiently cushioned for hanging belays on steep multi-pitch lines.

Blue Ice Harfang Tech Crampons

$230 at Backcountry $240 at Blue Ice

Weight: 1.4 lbs (per pair)

Sizes: one size

Pros and Cons

⊕ Best-in-class packability and adjustability

⊗ The flexible sole falters on super-hard ice; we prefer it for temperatures above 5°F

If you’ve ever opened your pack at the base of a climb to find a shredded back panel or puffy, you know the worst part of using crampons is often storing them. The Blue Ice Harfang Techs eliminate that issue by folding in half, which let us pack them into our helmets for puncture-free portability.

The secret? Blue Ice replaced the customary steel center bar with a fabric strap composed of ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene (UHMWPE)—the generic name for Dyneema. The two-inch-wide replaceable strap sacrifices little durability and is both highly flexible and lightweight: The pair clocks in at a mere 1.3 pounds. Not bad for a steel crampon.

This construction doesn’t just enhance packability, either: Because the strap ratchets through a buckle, it also allows for infinite adjustment, letting climbers of all shoe sizes dial-in a perfect fit. (Contrast that with steel bars, which have only so many size settings.) The Harfang Techs also have a knob on the heel bail, letting us make micro-adjustments on the fly.

Some testers reported that the UHMWPE strap tended to relax and loosen throughout the day, especially on the hard, north-facing ice of B.C.’s Stanley Headwall. But climbers in warmer environments had no issue. “I climbed M8 and WI 6 with no problem at all in Ouray and Vail,” says lead tester Maury Birdwell. “The steel also held up nicely and required no sharpening after 10 days of sustained use on ice and rock.” If you’re planning to kick into concrete-hard alpine ice, consider bringing a traditional crampon. Otherwise, the Harfang Techs should do the trick.

How to Choose Ice Climbing Gear

Where to Begin?

Your first purchase should be a pair of reliable mountaineering boots. While hardware like crampons and ice tools are relatively straightforward to rent or borrow, boots and apparel tend to be less so—and more critical to your comfort on the ice. Fit is critical. Purchase your boots too tight, and you’ll run the risk of cold toes or even frostbite. Too loose, and you’ll suffer from blisters on the approach and the dreaded toe-bang on the wall. While you can find a nice pair of used boots for $200 to $300, we recommend buying a new pair if that’s what it takes to find a perfect fit. Head to your local climbing shop, tell the sales associate about your objectives and experience level, and they should guide you to the perfect pair.

Next comes clothing. Thin, warm merino wool tends to be best for both socks and baselayers; it traps heat and wicks moisture without leaving you feeling overheated or encumbered. Hardshell pants—like the Patagonia M10—are critical to staying dry on weeping flows. Ditto for a hardshell jacket. Pack a warm baselayer top and a wicking, active midlayer like a synthetic fleece or wool sweater so you can finetune your insulation for the conditions.

Another piece of must-have gear is gloves. Most ice climbers carry two to three pairs with them at any given time. Wet hands are cold hands, so the number-one tip for staying comfortable in icy conditions is keeping those mitts dry. Like boots, it pays to buy new if that’s what it takes to find a perfect fit. At the very least, you’ll need a dextrous, medium-weight, not-too-tight glove for climbing, and a heavy-duty glove for belaying and emergency wear.

The final touch to your kit should be a big belay parka. A hood and interior glove pockets are nice, but the most important factor is warmth. Standing around belaying in the snow can be downright frigid. The bigger and warmer your belay puffy, the happier you’ll be.

Can I Use My Rock Climbing Gear?

While you can use your rock-climbing harness, rope, and helmet for ice, it pays to level up as you get more into the sport. Harnesses like the Petzl Sitta are compatible with ice clippers—big plastic carabiners that let you stash screws or an ice tool on the fly. Winter-specific helmets are designed to both keep your head warm and deflect torpedoing chunks of ice, and winter-specific ropes are thoroughly dry-treated to reduce the odds of freezing mid-pitch.

Can I Buy This Gear Used?

We recommend buying safety essentials—like ropes, harnesses, and helmets—new. It’s hard to tell if use gear has been compromised. And when it comes to saving your life, trustworthy safety gear is the cheapest insurance policy you’ll ever buy. For most other items, consider shopping secondhand; used gear can help you get a feel for what you like and don’t like before you shell out for a spendy new kit. Check out online forums like MountainProject.com, GearTrade.com, and even eBay. Craigslist and Facebook Marketplace can also be great options if you live in an outdoorsy town.

How We Test

- Number of testers: 5

- Number of products tested: 32

- Miles approached: 40

- Vertical feet climbed: 22,000

- Coldest temps encountered: -22°F

- Highest winds endured: 37 mph

Gear reviews are highly subjective, but we do our best to combat that by taking a slightly more scientific approach. At the beginning of each season, we wade through sheaves of PR requests, consider the specs and promise of each one, and then carefully select the gear we deem fit to test. Then, we do our utmost to get each piece in the hands of as many testers as we can—and in as varied conditions as we can manage.

This year, testers picked and kicked their way up everything from moderate mixed lines in Ouray, Colorado, to steep WI6 pitches on British Columbia’s Stanley Headwall. We belayed through blizzards, swung into bullet-hard ice, whooped over perfect sticks, and cursed through some of the wettest pitches of our lives. At the end of the year, we compared notes and selected only the best gear to review. Those are the products you’ll see here.

Meet Our Testers

Maury Birdwell

Maury is an attorney and climber based in Boulder, CO. He has had the good fortune to climb and establish routes around the world. Some highlights include freeing the original Royal Robbins line on Mount Hooker in the Wind River Range with Jesse Huey (Original Sin, 5.12+), the first free ascent of Armageddon (5.12+) on the North Howser Tower in the Bugaboos, Canada, and setting the car-to-car speed record for climbing (solo) the Diamond of Longs Peak. In 2012 he co-founded the Honnold Foundation with Alex Honnold – perhaps his greatest personal “send” to date.

Corey Buhay

Corey is a freelance writer and editor based in Boulder, CO. She is a former member of the U.S. Ice Climbing Team and has climbed up to WI5 and M12- around the Colorado Rockies. She is a volunteer climbing instructor at The Ice Coop, Colorado’s only dedicated ice-climbing gym, where she does much of her training. There, she’s fortunate to be a member of a vibrant and tight-knit local ice climbing community—where willing testers and fellow gear nerds are easy to come by.

The post The Best Ice Climbing Gear for Your Next Winter Objective appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Max Barlerin is a family man who holds down two jobs while also running a fledgling business of his own. But he also somehow found the time to open a 14-pitch 5.13 in Wyoming's remote Wind River Range.

The post The Secret to This Everyman’s 5.13 Big Wall First Ascent? A Work-Life Balance appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Max Barlerin is an everyman. He has a wife and child. He holds down two jobs to keep his bills paid—one as a climbing ranger and one as a cobbler—while also co-running a fledgling side business in Boulder, Colorado, dedicated to climbing education. And yet, he somehow makes time to author big routes—including a new 14-pitcher deep in Wyoming’s Wind River Range. The route, Children of the Sun (IV 5.13-; 1,500 feet), ascends the Monolith, a towering chunk of stone that looms over its corner of the Wind River Range like a broad-shouldered god. The project was the culmination of years of effort, a year-long recovery from a life-threatening illness—and a nearly heroic ability to find balance amid the chaos of life.

The Monolith first entered Barlerin’s consciousness in 2018, when he read about Sam Lightner’s first ascent of Discovery (IV 5.12c C1; 1,600 feet) on the same feature. The Monolith’s rock quality, aesthetics, and sheer size were all striking, and, for Barlerin, its remote location added a little extra sparkle. Plus, the Monolith only bore a handful of other routes—including the famous Beckey Route (5.9+). The majority of the massive face was a blank canvas.

Barlerin, it should be said, is no stranger to big alpine objectives. He’s put up a few first ascents in Rocky Mountain National Park—where he works as a ranger on his days off from cobbling— including multipitch trad lines Highwayman (5.11) and Geronimo (5.12-), both on Chiefshead.

“Max is an incredible undercover boss in the mountains,” said Maury Birdwell, who accompanied Barlerin on the first free ascent of Children of the Sun this September. “Aside from his technical climbing ability—at the 5.14 level—he has tons of experience [in the alpine].”

Enraptured by the Monolith, Barlerin trekked into the Winds a few times to take a look—once in 2020, and once in 2022. The 2020 trip was ill-fated; Barlerin and a partner got eyes on the feature, but stormy weather kept them off the rock. They’d intended to tackle the wall in a single-day push, but didn’t have enough gear to either do the route or wait out the weather. So, in 2022, Barlein came back better equipped. This time, he had more gear, portaledges, camping equipment—and Keiko Tanaka.

Barlerin and Tanaka had worked together for years: Tanaka is the operations manager at Rock and Resole in Boulder, Colorado, where Barlerin is a cobbler. But Tanaka is also as close as you can get to a household name in the U.S. aid climbing scene, having notched 11 different El Cap routes and several first and second ascents in the Fisher Towers. Barlerin had never climbed with her before, but he knew that Tanaka knew what she was doing—and she was psyched

“I had a hard time finding partners who were willing to hike the 13 miles into the Winds without any certainty of success,” Barlerin said. “But Keiko was.”

“I hadn’t done anything that remote, and the Monolith was about two-thirds bigger than the other first ascenting I’d done,” Tanaka said. “This lofty goal, to go out there and just figure it out—that was really inspiring to me.”

So they hired horse packers and—armed with haul bags, cams, portaledges, and aid gear—set off into the Wind River Range for a two-week expedition. Neither Barlerin nor Tanaka had any vision for their line until they stood at the base of the wall, gazing up at the sea of silver stone.

“That’s a really rare thing these days, just to go up to a formation and have open country laid out before you like that,” Barlerin said. “I love that. I live for that. I think it’s rare for our generation of climbers to be able to step into the unknown and try to get a little taste of the adventure that’s part of all the alluring stories and climbing literature we grew up with.”

Barlerin and Tanaka ultimately spotted a potential line on the Monolith’s Northeast Face: 1,500 feet of adventurous-looking climbing, connecting sections of run-out face climbing, splitter cracks, vertical seams, and steep roofs. They didn’t know if it would go, but it seemed worth a shot.

“So we chose a line and just kind of whacked away at it over two weeks,” Barlerin said. The method: Barlerin would free-climb until the terrain or gear got too bad, at which point Tanaka would take over, aiding via cams, hooks, and tension traverses until she found a logical belay. At that point, she’d build an anchor and Barlerin would jug up, cleaning the route as he went and placing bolts where necessary.

“We were able to play to each other’s strengths,” Barlerin said. “It worked out. Yes, I cleaned her out of the tent with my farts, and, yes, she listened to way too much ABBA. But we made a good team.”

Their line, Tanaka said, followed “bulletproof granite” and veins of quartzite, much of it between 5.11 and 5.13/A3 in difficulty. At one point, they pulled up to a belay to find nothing before them but a sea of rounded, granite knobs—no protection in sight. It was Tanaka’s turn. She racked up, clicked into problem-solving mode, and went questing.

“I had to lower down about 20 feet, then tensioned and pendulumed to the right to access this quartzite vein,” she said. “I mostly hooked and used number-one beaks—really small pitons—and all bodyweight placements. I was in this really hard quartzite, so the pins weren’t going in.” She followed tenuous hook after tenuous hook until she gained a crack, which deposited her at a solid belay. Barlerin was able to rap-bolt the X-rated face, reducing the risk enough to bring the grade to a run-out 5.12-.

“Probably no one will ever do that aid pitch again,” Tanaka said. But she’s glad she got to.

Over the course of their two weeks on the wall, Barlerin was able to free every pitch except one—a 60-foot A3 beak seam on pitch nine that seemed to go at low-end 5.13—before their weather window closed.

He meant to return for it fairly soon after the first trip, but life got in the way—big time. Shortly after coming home from the Winds, he started to experience extreme fatigue. That devolved into a 105°F fever, ruthless nerve pain, and chills that left his whole body shaking. After weeks of seeing various doctors, he finally got a diagnosis: he had West Nile virus.

“I was sick for about six months,” Barlerin said. “There was a lot of nerve damage and nerve pain. I had to teach myself how to climb again.”

Coming back to activity was slow. Everything felt painful, and it took him days to recover from even the simplest exercise. He started with V0 and 5.7, and he worked up from there.

By the next year, he was back to climbing at a moderate level, but he and his now-wife had gotten engaged. Wedding planning kept him off the rock that summer. And the arrival of their first child kept him home the summer after. That same year, he launched his guiding and climbing education business with Tanaka, which they dubbed Yama Vertical (yama is Japanese for mountain), and he poured his spare energy into a longtime project closer to home: Tommy Caldwell’s The Honeymoon is Over (5.13c; 1,000 feet) on the Diamond on Longs Peak.

“It sounds like a lot to be doing all at once, but it’s really just me focusing on the things that are most important to me,” Barlerin said. “When I was younger, I spent a lot of time on whimsical trips. I would hear about an area or route that was in season and just drive out there to check it out. These days, I’ve had to really refine my climbing and my life to what’s important. Family is first. After that, climbing and career. So I sat down after my daughter was born, and I asked myself what I really wanted to be doing with my life. Now I try to cut out all the faff and be as efficient as I can with the time I have.”

On August 4, Barlerin sent Honeymoon. By late August, his fitness and free time started to align again. His thoughts turned back to the Monolith. He wanted to go back and finish what he started. It would be his first trip away from his newborn daughter, and he knew that would be painful on its own. But going back felt important, and Barlerin’s wife understood.

This time, he called up photographer Alton Richardson and alpinist Maury Birdwell—both talented free climbers—to go with him. They trekked into the Wind Rivers in early September, intending to free the route, possibly in a day. But bad weather plagued the group. They were able to climb eight pitches up to the crux—all of which Barlerin freed consecutively—and fix ropes before drizzle turned to rain. Graupel—tiny chunks of packed snow—poured from the sky as they rappelled. Within a few days, their gear stash was buried in about four feet of the stuff. They had to dig it out by hand. A few days later, the team was halfway up the wall when a gear bag cut loose and went careening 700 feet to the ground. Between that and the still-dripping rock, they were forced to descend once again.

With just a 10-day trip, the team didn’t have that kind of time to lose, Birdwell said. “We’re all balancing work, personal life, and in the case of Max, a newborn. So we played the cards we had.”

It wasn’t until the day before they were due to hike out that the team finally got a small window.

Barlerin squinted up at the wall, streaked with water and dark under the gray sky. The rock wasn’t even close to dry. But it was now or never. He’d been thinking about this route for years, and this was his third expedition out here. He missed his wife and daughter. He wanted to get it done. So he geared up, and he started jugging.

“It was a Hail Mary attempt,” Barlerin said. “The crux pitch was still wet, but I was able to clean it up and chalk it.” After a run-through on toprope-solo, he pulled the rope and decided to go for it. And somehow, it all came together. His fingertips moved deftly up the seam, one hand after the other. He felt strong—something that, deep in the shivering pain of West Nile, he’d feared he might never feel again. And after 60 feet, when he at last pulled up to the final anchor of this massive multi-year project, he felt gratitude wash over him.

“We were initially hoping to do an in-a-day ascent or an integral ascent, and with the weather, that just didn’t happen. So, yes, we traveled a really long way just to free this one pitch,” Barlerin said. “But it felt good to get it done, and to finally have this complete route. It felt like a big relief.”

Birdwell, Richardson, and Barlerin have all hinted that they’d like to go back to do it again—hopefully with better conditions and in better style. Though, Barlerin confesses that if life gets in the way again, he’d be at peace with leaving it as is.

As for the name? Children of the Sun is a reference to Barlerin’s two-month-old daughter, Anya, who was born on the solstice.

To him the name is a nod to the fact that, no matter how hard or glorious the climbing is, no matter how all-consuming your goals, there’s always something that matters more. Back in the real world, there’s someone more important to come home to.

The post The Secret to This Everyman’s 5.13 Big Wall First Ascent? A Work-Life Balance appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

After decades of friendship, a British duo just nabbed a first ascent of Yawash Sar, a stunning 6,000-meter peak in Pakistan.

The post They Could Be Retired. Instead, They’re Chasing Unclimbed Peaks in the Karakorum. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

There are bold alpinists, and there are old alpinists. And then there are Mick Fowler and Victor Saunders.

Earlier this month, the pair—who have been friends for nearly 50 years—topped out the Karakoram’s 6,258-meter Yawash Sar, notching an impressive first ascent of the remote Pakistani peak. But while that alone is remarkable, it’s their stats that really earn the double-take: At the time of the climb, Fowler was 68 years old. Saunders was 74. In a world where daring alpinists rarely seem to live past middle age, these two seemed to have cracked the code.

The first secret? Knowing what you’re doing. Saunders and Fowler are both decorated alpinists. Fowler is a three-time Piolet d’Or winner. Saunders is an IFMGA-certified mountain guide and has six Everest summits—among many others—to his name. Both men have authored notable first ascents on 6,000- and 7,000-meter peaks throughout the Greater Ranges—including the first ascents of the Golden Pillar on 7,027-meter Spantik in the Karakoram, which they did together in 1987, and of the 1,000-meter North Spur (ED) on Sersank Peak (6,050m), in the Indian Himalaya, in 2016.

But the partnership didn’t always feel so divinely inspired. In fact, when the pair first met in 1976, they were sure they’d never climb together. At the time, Fowler had developed a bit of a reputation as a choss hound, establishing FAs on sea stacks, chalk cliffs, and other crumbling chunks of stone around the U.K.

“He was known for having a predilection for loose rock,” Saunders recalled. “Everyone said, ‘Don’t climb with him, this person is not normal.’” But one evening, Saunders was sitting around a pub, drinking beer, when Fowler called him up.

“Mick had run out of climbing partners for the week. It was a Wednesday, and he was going on a Saturday,” Saunders said. “I had been warned not to climb with him, but by then I’d had too much beer and I said ‘Oh, alright.’” The two spent several days climbing in Scotland, and Saunders discovered his assumptions had been wrong.

“I felt happier with Mick on serious, difficult ground than I did with lots of people on easier ground,” Saunders said. The two found they had a similar approach to climbing, similar risk tolerances, and similar visions for what made a good line.

That year, they nabbed the first ascent of Ben Nevis’s The Shield Direct (VII, 7)—Scotland’s first route above grade V. The trip launched a 45-year partnership that’s yielded more than a few cutting-edge, alpine-style lines. And yet, they both call Yawash Sar one of their finest routes to date.

“It’s shapely and steep, with good climbing,” Fowler said. Which all came as a bit of a pleasant surprise.

“We were quite depressed, initially, because we had a period of bad weather for the 10 days or so we were in base camp,” Saunders said. “The forecast just looked horrendous. At one point, Mick said he didn’t think we had more than a 10-percent chance of getting up it.”

But then the weather cleared. And once they crossed the bergschrund and got a good look at the route, the stoke started to set in.

“Victor is a complete beast when it comes to walking and wading through snow,” Fowler says. “But above the bergschrund, that’s what we like most: Doing about 50 meters of lung-busting activity at a time, then sit down, belay, enjoy the view, snap a few photos, and hurl abuse at your mate. That’s when the fun begins.”

But while fun, it wasn’t all easy. Route finding was the first real challenge.

“It was a complex face,” Fowler said.” We were following thin, discontinuous ice streaks, and a lot of them ended in huge vertical walls of loose rock. It was very difficult to work out which line would connect to the face.”

Another big issue was the route’s relentless verticality. Much of it was steep snow flutings and WI 3-4 ice, interspersed with short, steep mixed pitches. Ledges were few and far between—which made setting up camp difficult.

“The place was unusually devoid of decent sites for bivouacs,” Fowler said. In some places, they built their own ledges by stacking rocks against the slope. One night, their only option was a narrow catwalk, gently sloping and slick with ice. They spent the night sitting upright, occasionally slipping off the ledge into a startling free hang. This was particularly uncomfortable for Fowler. A survivor of colorectal cancer, Fowler had a good chunk of his rear end removed during an invasive surgery. He also now uses a colostomy bag. Both the scars and the bag make sitting—and hanging in a harness—painful.

“We probably only slept about a half-hour total that night,” said Fowler. “That made the next day of climbing really difficult.” As luck would have it, the sitting bivy lay right beneath the crux pitch: a steep wall they’d been worried about since base camp. Up close, they found it was composed of incredibly loose rock—Fowler’s specialty, if not his preference at that moment.

“This was the pitch that had been weighing most heavily on our minds,” Saunders said. “We thought that if there was a pitch that we’d get turned back by, this was it. We had no idea if we’d be able to do it.”

Any rock that wasn’t frozen together was loose. Stacked flakes of shale lay everywhere. But after a little reconnaissance, Fowler managed to scout a way through the headwall. Saunders followed, tiptoeing through the skittering blocks.

After that, only three pitches of steep snow lay between them and the top. And when they pulled onto the summit, they couldn’t help but smile. “It was one of the best routes we’d done together,” Fowler said.

As for the other secrets to their rarified old, bold status? First, exercising caution. Once settled in base camp, they took more than a week to scope out the route with binoculars and identify the safest possible line.

In general, both men say they’re extremely picky about their choices of objective. (Fowler, for one, favors loose rock less than he used to.) And both are choosy about their partners.

“Over the last 50 years, I’ve had very few climbing partners that I’ve done anything serious with. I can count them on one hand,” says Saunders. “I think it’s good to appreciate what the objective dangers are on a given route. But those are only half the dangers. The other half are the subjective dangers—the people, the egos. One way of staying alive is staying away from dangerous people.”

But the biggest reason they’re still climbing after all these years is much simpler: they love it. They love it enough that it’s worth the pain. It’s worth the achy joints and indigestion, the wind and the cold, the hanging bivies and occasionally leaky colostomy bag. Both Saunders and Fowler are careful to keep ego out of the equation. They climb only for enjoyment—never for glory or gain. That keeps them from getting in over their heads and ensures the stoke remains strong. And, by all accounts, it’s working.

“I don’t think this partnership will end any time soon,” Fowler said. “We already have plans for the next adventure.”

The post They Could Be Retired. Instead, They’re Chasing Unclimbed Peaks in the Karakorum. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

In 2023, Catalina Shirley took a life-threatening fall and questioned whether she’d ever lead again. This year, she returned to the site—and became the first American to podium in an Ice Climbing Lead World Cup.

The post Meet the Young Ice Climber Putting The US Team on the Map appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Slats of sun fall through the coffee shop’s high windows, casting shards of light and shadow over the patrons within. I’m one of them, sitting on a bench with my back to the glass, staring across the table at the woman who was once my greatest rival.

Catalina Shirley blinks in the light. She’s 21, tall, and lanky, with a mane of curly blonde hair she usually keeps in a pair of tidy braided pigtails. She’s got a gentle voice, pale blue eyes, and a wide smile. It’s a face you’d expect to find on a Disney princess, not on a hard-charging, internationally ranked, three-time U.S. National ice climbing champion.

I watch her cup her latte with her hands, smiling at me. And I think about how strange it is to be a journalist sometimes. A few days ago, Cat and I were battling it out on an ice-encrusted climbing structure in southwest Colorado, going head-to-head in a high-caliber international competition just as we have for years. Today, we are wearing jeans and drinking lattes, and I will ask her, on journalistic record, how exactly she got so much better than me. Then, I will call her mother and ask the same question.

The stranger thing is that her answer actually matters—and not just to me on a petty, personal level. Catalina is a case study of climbing for all the right reasons and using that pure, joy-fueled motivation to achieve enormous success. She’s a full-time student, works part-time, and grew up in an average household. Her parents weren’t climbers. She wasn’t born with abnormal opportunities or mutant-level DNA. She just found a way to work with what she had. And in doing so, became proof of what’s possible—for me. For women. For everyone.

***

I first met Cat in December of 2016. I was 23, and she was 14. I was a reporter, and she was a youth competitor at the UIAA Ice Climbing World Cup in Durango, Colorado. At the time, I had no idea what competition ice climbing really was; I was just there on assignment.

The competition structure stood in a brewery parking lot. It was a hulking, ramshackle tsunami wall cobbled together from plywood sheets and two-by-fours. I shuffled around it, weaving around knots of climbers from Korea, Russia, Ukraine, Italy, and Japan, looking for people to interview. I spotted Cat and assumed she was a local child searching for entertainment. I introduced myself. She told me she’d participated in the youth competition that morning. Then, shyly, she revealed she’d placed second.

“How long have you been ice climbing?” I asked.

“I just started a couple of months ago.”

She was small and soft-spoken. I had to stoop to hear.

“That’s just how she was as a kid,” Katy Shirley, Cat’s mother, told me over the phone last month. “Catalina was always kind of quiet and shy. She was so unassuming.”

But she was also very high-energy. Cat’s parents tried enrolling her in soccer, gymnastics, and other sports, but none really clicked. Then, after watching their 7-year-old daughter stem up the narrow hallways in their home, they decided to enroll her in a local YMCA climbing camp. There, she met a 12-year-old girl named Bridget, who took young Cat under her wing.

“I wanted to be on a climbing team like Bridget,” Cat recalls. “She was my first mentor.”

When Cat was nine, the family moved from San Diego, California, to Durango, Colorado. There, they enrolled her in the tiny climbing program at The Rock Lounge, Durango’s now-closed climbing gym.

The Rock Lounge’s head climbing coach, Marcus Garcia, eventually convinced Cat to join his side project: a fledgling youth ice climbing team. It was the first of its kind in the country.

While Cat seemed to enjoy the ice climbing, Garcia said she wasn’t exactly a natural.

“She was shy and timid and afraid to fall with the ice tools,” he says. “And she was lanky, wiry, tiny. She probably weighed 80 pounds when I first met her. ”

The first time I competed against Cat—at a small local event in the spring of 2017—I remember being astonished at how slowly she moved. At age 14, she was as shy on the wall as she was on the ground. Most competitors can flip the switch into go-mode when they need to. Cat didn’t seem to have a switch at all.

“But then something started to click,” Garcia says. After a few seasons of experience, Cat became more comfortable with the tools. She found a certain fluency with them. She’d always been hard-working, but now she had just enough confidence to put her other superpower to use: her tenacity.

“Looking at her you wouldn’t know it, but inside she’s very determined and tenacious,” Katy Shirley says. “She wouldn’t give up on things.”

Within a few years of knowing Cat, I realized that myself. If she got to a crux during a competition and couldn’t reach a hold, she would sit back and consider it. Then she would throw for it again—and again and again. Sometimes, she would be in the same spot for minutes, trying repeatedly.

It wasn’t a frustrated, self-flagellating sort of repetition, the way you see some climbers do. Instead, Cat’s efforts seemed to come from a simple sense of curiosity. She wanted to know how it could be done. And she was certain that if she kept throwing, it would have to happen sooner or later. So, she’d sit there, calmly working out the problem as the audience held its breath. It was like she’d just sort of forget that she was supposed to be tired.

The year after that first competition in 2017, Cat and I made the U.S. Ice Climbing Team. Back then, I outperformed her a lot of the time. To me, she was still just a kid. Then, around 2021, something changed. Cat found her switch.

***

To understand Catalina Shirley, you have to understand her coach. Catalina’s determination, strength, and cunning are all her own, but her climbing philosophy largely comes from him.

Marcus Garcia is a Durango-based professional climber and guide. In his nearly 30 years of climbing, he’s notched hundreds of first ascents, including desert towers and scarcely repeated big-wall routes on El Cap.

In 2016, he embarked on a dubious new experiment: he gathered together a small band of Durango children, strapped tiny knives to their feet, put axes in their hands, and decided to turn them into America’s first youth USA Ice Climbing team.

Over the years, all those kids have gone on to become incredible prodigies. One, Keenan Griscom, became the youngest American ever to win the Ouray Elite Mixed Climbing Competition at age 16. Another, Kevin Lindlau, sent the world’s hardest known drytooling route (Aleitheia, D16) just last month. Young phenom Liam Foster became the youngest American to climb the famous Line Above the Sky (D15) at age 19. Last year, he sent his first 5.14c. And just a few weeks ago, Catalina Shirley became the first American to podium in lead at an Ice Climbing World Cup. Not the first woman, but the first American. Ever.

Even more impressive, Garcia still acts as a mentor to most of them.

“He’s not their coach for just a few years or a season,” says Katy Shirley, Catalina’s mother. “He’s really in it for life.”

When Cat was in middle and high school, the local parents would drop their kids off with Garcia for weeklong trips. Sometimes, those trips were to competitions in Denver or Colorado Springs. Sometimes, they were abroad.

“A bunch of us went to France with Marcus when I was 14. It was my first time traveling abroad without my parents,” Cat recalls. “We were there for a week, and he figured out how to house all of us and feed all of us and drive the stick-shift van with all of us.”

Cat says Garcia always seemed to put them first, even though he was running a gym and a construction business back home.

“A lot of his own life had to go on the backburner—including his own competition climbing—so that he could focus on us,” Cat says. “He’s very much a giver, and he gave a lot to us kids.”

Even today, despite their busy schedules, Garcia finds time to send Cat training plans and talk through her performance at every competition. When Cat has good or bad news to share—in climbing or life—she calls Marcus.

“Anytime she calls, he’ll respond,” Katy Shirley says. “For him, it’s like she’s his kid, as well.”

Garcia was also adamant about treating all kids equally—regardless of age or gender. In his gym, there was no beginner or advanced category. Everyone did the same workouts. Katy Shirley recalls a competition in Colorado Springs where he had all the kids compete against each other on the same route for the same podium.