How Nathan Longhurst bagged 100 summits in 4 months

The post American Dirtbag Becomes 2nd Person to Tick Off New Zealand’s 100 Peaks Challenge. Para-alpinism was His Secret Weapon. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Something historic, groundbreaking, and—I think it’s fair to say—paradigm-shifting has just gone down in the sport of alpinism. And there were no big corporate sponsors or throngs of media covering it. Starting on November 16, 2024, 25-year-old American Nathan Longhurst quietly embarked solo on the audacious 100 Peaks Challenge in New Zealand.

The NZ Alpine Club originally created this challenge in 1991 to highlight the beauty and variety of peaks in New Zealand. But it had proven perhaps a bit too ambitious. Until Longhurst came along, only one person—Don French—had completed the ticklist … 30 years after the list’s debut.

“Doing them all in a year or a summer season sort of never really crossed my head as a possibility,” says French of Longhurst’s effort. “… it is a horrendous thing!”

A paragliding “quiet crusher”

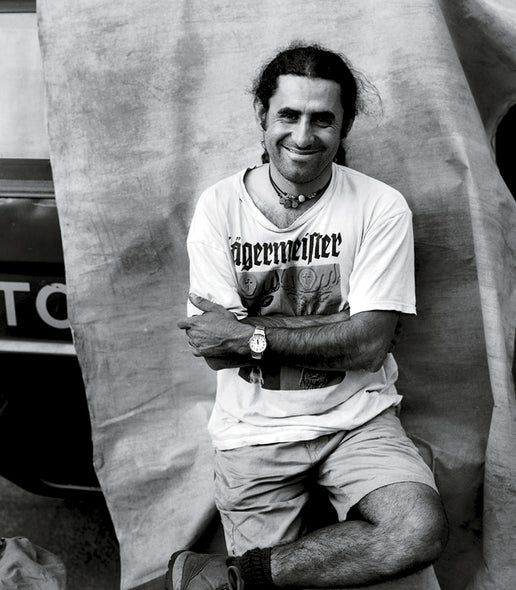

I first became aware of Longhurst’s unique penchant for immersive alpine challenges when I heard about him climbing the Sierra Peak Section: 247 peaks in the Sierra in just 138 days. It’s hard to put into words how heinous that is! It’s definitely an athlete-level accomplishment, and I really wanted to meet this dark horse. What I found was a pure soul with no big sponsors or media glory—just a dirtbag climber living nomadically in their van. Having just started the Dirtbag Fund, I mentally filed him away as a worthy kid to support in some way.

When I met Longhurst, I found him to be a sweet, soft-spoken kid, not fond of hyperbole. But clearly, there was something special about him. For instance, he was, at the time, the youngest finisher of Washington’s 100 highest peaks list—it took him just 84 days. “It wasn’t so bad,” he said of that achievement. “After a couple weeks you just reach this baseline of suffering where you can keep going indefinitely,” he elaborated. “That’s what I love, is really immersing yourself in the experience.” He fully lived up to the climbing world’s label of “quiet crusher.”

Tackling New Zealand’s 100 Peaks Challenge

Recently, Longhurst fell in love with paragliding and was looking to incorporate flying into his next superhuman sufferfest. “What I realized was you can climb so many peaks so much faster if you fly off and between them,” he explains. All this to say, he was uniquely suited for this obscure, yet formidable 100 Peaks Challenge. When I heard about his goal, I realized it was the perfect use of “Dirtbag Fund” cash—though it did make me nervous knowing how out there and close to the edge he would probably get. But that’s what made it compelling. With any good adventure, nothing is guaranteed.

See a map of the NZ peaks mentioned in this story:

When Longhurst set off to complete the grueling list in a single summer season, he recognized that, “there is a lot that can go wrong, and I probably won’t do it, but that’s what makes it so exciting.” Indeed, if he didn’t manage the many inherent risks in the challenge perfectly, it would also be incredibly dangerous.

Combining his love for ultra-running, climbing, and paragliding, Longhurst slogged his way through this remarkable feat of endurance, logistics, and creativity. Longhurst’s friend, Dan Cervelli—a fellow alpinist, who’s also on the board of the Dirtbag Fund—tracked his progress on a website dedicated to the project. Over 103 days, he soloed all 100 peaks, often descending by paraglider.

The stats are outrageous:

- 1,000 miles (1,609km) by foot, bike, or kayak

- 470,000 feet (143,256m) of vert!

- 84 paragliding flights, including three flights to cross rivers and several to reposition high on the next peak. The rest were descent flights from summits, most of which were first descents.

- 99 peaks soloed

- 1 peak (#97, Taranaki) with his dad

- 103 days to complete the challenge

The highs and lows of Longhurst’s experience

Unsurprisingly, a journey of this magnitude had its low points, including days of what New Zealanders call “bush-bashing” (the Kiwi term for bushwhacking). New Zealand is famous for some of the longest, most dense, and nearly impenetrable “bush-bashes” in the world. Longhurst listed some of the challenges as bush-bashing, bad weather, and significant climate change-induced glacial recession, which he says made “for some really nasty and dangerous travel through steep post-glacial moraine walls.”

But perhaps the absolute low point of the endeavor came on peak number 76 (Mt. Irene), when Longhurst badly sprained his ankle on landing. “I heard a pop, and I was alone and very far from civilization,” he recalls. His self-rescue entailed 10 hours of “butt-scooting, bush-bashing, and a 20-mile kayak.” Miraculously, after sitting out a few days of bad weather, he was back at it. He discusses this ankle-spraining fiasco in a recent podcast interview on The Climbing Majority.

“After that, I became more aware of how being really invested in a big project and being super fatigued can affect risk management,” he admits. “Honestly, I’m not proud of some of the risks I took, but through the process, I became more self-aware and managed my risk more responsibly for the rest of the project.”

Ultimately, Longhurst felt that integrating paragliding into alpinism created more opportunities and allowed him to test out different strategies in his pursuit of the 100 Peaks Challenge. He also bagged a possible first ascent or two along the way. On Mt. Alba, he soloed the presumably unclimbed north ridge, which included a V2 arete lieback boulder problem, in his trail runners. Then he flew off the top.

Of Longhurst’s achievement, Alastair McDowell, who holds many alpine speed records in New Zealand, says, “His creative use of the paraglider to link remote peaks was very innovative and shows us what is possible in NZ with this new method of mountain travel. It takes locals years to learn the intricacies of approaches and routes, and often times peaks require multiple attempts. It’s astonishing that he managed to gather enough beta to climb all one hundred peaks without a single failure!”

How Longhurst used para-alpinism to his advantage

Thanks to “para-alpinism,” which many climbers will say is the “the future of alpinism,” Longhurst was able to tick off a literal lifetime of summits on his summer vacation. Essentially, para-alpinism is a form of alpinism that uses the paraglider as a tool for descent. It can also be used as a way to approach an objective. Instead of an entire day spent descending a peak, you are back at the base in a matter of minutes.

Ice climber Will Gadd, who started paragliding 30 years ago, but found the gear too heavy for practically exploring the mountains, says that Longhurst’s pioneering use of para-alpinism proves that “the dream is real.” He says that paragliding may just be “the coolest evolution in mountain sports.” But Gadd adds that para-alpinism is “super hazardous” and requires extensive skill—not to mention something like 1,000 hours of airtime—to do what Longhurst pulled off in New Zealand successfully. McDowell reflects that Longhurst’s “lack of ego” and his pure passion for being in the mountains is also what led to his success.

While the benefits of a descent via paraglide are undeniable, the paraglider does undertake additional risk and weather becomes even more of an issue. “The wing can be a benefit, but also a detriment,” Longhurst says. “Sometimes I wasn’t present in the moment as much as I would have liked to be, because I was constantly thinking about wind—whether flying conditions would be safe.”

Longhurst says that ultimately he was attracted to this challenge because it lends itself well to para-alpinism. “The peaks in New Zealand are steep and rugged, and have huge vertical relief, providing ideal terrain for climb and fly objectives,” he explains.

All in all, Longhurst flew off about 60 peaks, but also used his paraglider in innovative ways, including for glacier travel between huts in the high-alpine section of Mt. Cook. During linkups, he used his paraglider to reposition between peaks, sometimes landing at their bases or slope-landing on their flanks. In a few cases, he also top-landed near the summit, skipping hours of additional approach time in the process.

In a traditional sense, some of these summits don’t “count” because they weren’t climbed from the base. Longhurst fully acknowledges this. He has not claimed to have completed New Zealand’s 100 Peaks Challenge, according to the rules issued by the NZ Alpine Club. Another caveat to his accomplishment is that he climbed the main, high summit of Mt. Elie de Beaumont, instead of the west, lower summit included in the formal list. He didn’t realize this at the time.

But from the perspective of adventure—and the fact that he stood on each summit—Longhurst’s effort is certainly epic.

What’s next for this para-alpinist

While he officially ticked off the 100 Peaks Challenge on February 26, 2025, Longhurst isn’t taking a break anytime soon. He’s planning to stay in New Zealand until early April and has been taking some speedflying laps.

After he summited his 100th peak, he told me that the spirit of this mission was driven by his philosophy to “do more of what you love.” He encourages people “to find a really difficult, scary, and challenging project, if it aligns with your vision of yourself and who you want to be in the world.”

Longhurst’s historic mission was supported by The Dirtbag Fund, which gives out yearly grants to climbers who are contributing to the sport and culture of climbing, while scraping by on next to nothing. The Dirtbag Fund will be presenting a short film documenting this mega-ultra-para-alpine achievement, which will likely debut at the New Zealand Mountain Film Fest in June.

When asked for any final thoughts, Nathan responded: “I’m so grateful for the opportunity I’ve had to experience these mountains in such an immersive way. It was beautiful and scary, humbling and empowering … it was epic.”

The post American Dirtbag Becomes 2nd Person to Tick Off New Zealand’s 100 Peaks Challenge. Para-alpinism was His Secret Weapon. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Wright recounts that time he and Alex Honnold were sandbagged

The post Cedar Wright on “The Value of a Good Sandbag” appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

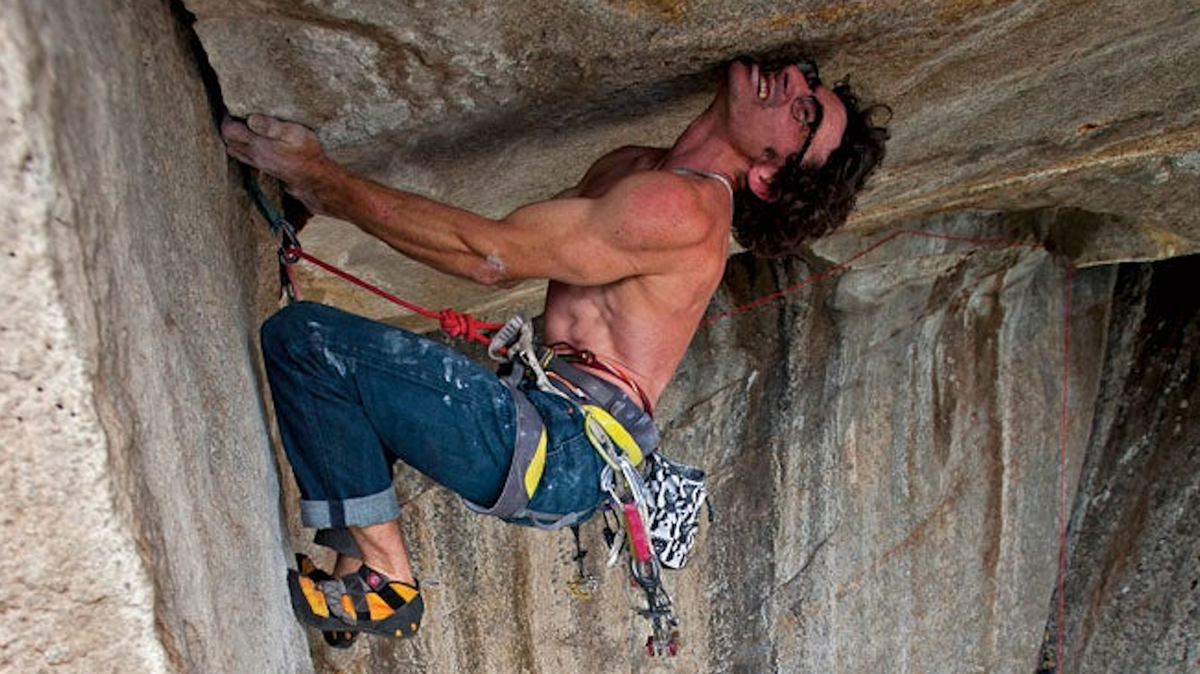

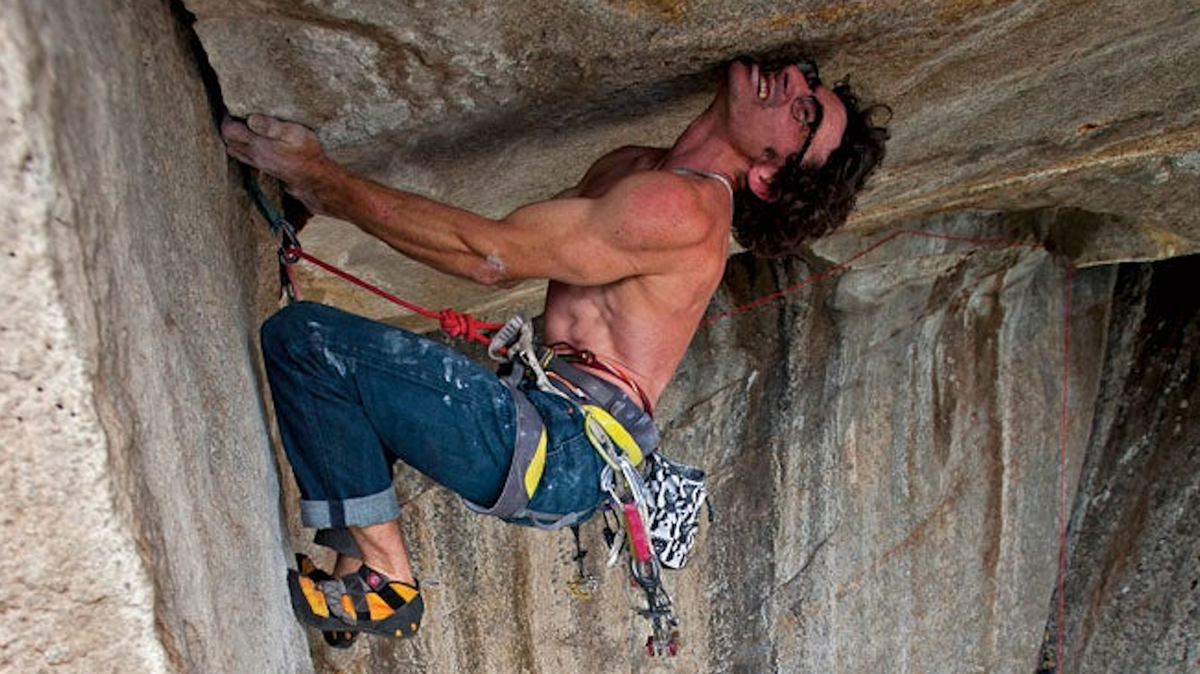

It’ll be ironic when Alex Honnold dies on a rope, I think, as each of his sketchy moves rains more choss on me at the belay. We are on pitch two of the Shark’s Fin in the Canyonlands of Utah, and in a bad spot. Alex’s foot trembles on a dirt clod. “Watch me, dude,” he says as his voice shakes. Every third hold rips off the wall while his body tilts and teeters on the verge of catching some HUGE air.

“This route is awesome; you can bring all your favorite holds home with you,” I joke. “Shut up and belay,” Alex snaps. The rope arcs 80 feet to Alex’s private hell without a single piece of protection capable of holding a fall. Initially, I worried Alex would rip us both off the wall if he pitched, but currently there’s no need to belay. If Alex falls now, he will deck from the second pitch.

How in the name of Royal Robbins, Warren Harding, and all things holy did we end up here? One word: SANDBAG. For those living in a bubble of friendly first ascents, honest grades, and safe routes, a sandbag is a route that is very, very hard for its grade. Climbing culture defines it in every online glossary, but my favorite comes from the Brits at The British Mountaineering Council (BMC).

Sandbag. (noun) A route whose grade belies its difficulty. This can be either because it is undergraded, or requires a trick move to overcome the crux. Or it’s just more work than it looks.

Sandbag. (verb) To direct someone to a route that is a sandbag, saying things like, “It’s easy; you will love it.”

The Shark’s Fin sandbag came in the verb form. During our “Sufferfest 2” mission to climb 45 desert towers in the four corners of the American Southwest by bike in spring 2014, Rob Pizem, a prolific desert climber, generously suggested routes.

“If you guys are down at Standing Rock, you have to do my route on the Shark’s Fin. It’s a super-fun tower with some easy climbing up to a fun, short 5.12 roof section; you guys could just run right up it. You’ll love it!” Rob effused with an innocent smile. In retrospect, it must have taken everything he had not to laugh out loud.

A week into Sufferfest 2, we parked our bikes in Canyonlands, ready to link Standing Rock and the Shark’s Fin together. After climbing the 5.11 route on Standing Rock in less than 25 minutes, we were confident Shark’s Fin would take us no time. One horrifying hour later, I had climbed a meager 60 feet. Each pitch was a 5.12 religious survival. Only a halfway-pounded-in piton protected the “fun short 5.12 roof” at the top. Even Alex—famous for being an atheist—saw God on that pitch. We cursed Rob all the way up the tower and thankfully topped out, albeit with twitchy, thousand-yard stares. The Shark’s Fin was the steepest, hardest, and most unique route of the trip. If Rob had told us how heinous and difficult the route was, we never would have climbed it.

That’s the value of a good sandbag; it pushes us out of our comfort zones and into adventure. But sadly, sandbags are in danger of going the way of Lycra, Tricams, and dirtbags. Not only are grades getting softer and softer (just compare 1980s grades to anything after 2002), but for the last 20 years, climbers have taken it upon themselves to upgrade one classically stout route after the next.

For 50 years the Steck-Salathe on the Sentinel in Yosemite was 5.9. When SuperTopo came along with a detailed rack list and a move-for-move beta map, it became 5.10b-. What the hell?! Sure it was really, really hard for 5.9, but that was part of the route’s charm. John Bachar originally rated Tuolumne’s Bachar-Yerian 5.10d—bless him for that. Now it’s 5.11c. This trend isn’t just in Yosemite. I’m sure every climber can think of a route that used to carry a lesser, but more “benchmark” grade.

R.I.P. Sandbag.

Obviously underrated routes and “stout” areas remain, but one well-meaning guidebook author or Mountain Project consensus can destroy yet another perfectly good sandbag. Think before you upgrade! Thankfully we have entire areas that remind us about how back in the day, we graded things a little differently. Shout-out to Seneca Rocks, Eldorado Canyon, Yosemite, Devil’s Lake, Vedauwoo, and Index to name a few. Also a special shout-out to plus grades, which are usually harder than minus grades with a higher number. “It’s only 5.9+.”

How can we keep the sandbag alive? Perhaps more first ascensionists should take the tact of my late great friend, climbing mentor, and notorious sandbagger Sean Leary, who once said, “Give routes the lowest grade possible while keeping a straight face.”

Of course routes can’t all be sandbagged. Be it the Yosemite decimal system, weird British E-grades, or the indecipherable UIAA system, the aim should be to give climbers an idea of the difficulty and danger of a route. It’s not all science, though. We use grades to set goals, compare ourselves to others, and quite often as a source of ego gratification. And, for this grade-induced inflated-ego syndrome, there is no better antidote than a good old-fashioned sandbag.

“How hard do you think it is?” I asked Rob Miller 14 years ago in the Yosemite cafeteria. A week before, I had finally freed a wild and proud 40-foot roof called The Gravity Ceiling, a former aid route, at the top of Higher Cathedral Rock. My epic siege prompted me to give it the illustrious grade of 5.13a, a standard-setting Valley grade at the time.

“Well Cedar, I wouldn’t say it was 13a,” Rob said before pausing to push the knife farther into my heart. “I’d call it athletic 12c.”

This brutal and notorious downgrading prompted Mikey Schaefer and James Lucas to call one 5.13 pitch on Schaefer’s Middle Cathedral route Father Time “athletic 12c.” I adjusted my grading scale after that, and while I still occasionally slip into wishful ego grading, it rarely happens these days.

Many climbers argue that sandbagging is dangerous, or just another form of “humble bragging,” a not-so-subtle way of stroking your own ego. Those claims aren’t without merit, but still I profess my love for the sandbag. And it’s not always malicious. Sometimes the climber is just too damn strong and sandbags everyone accidentally, especially when rating a route well below their level. Most 5.14 climbers have a hard time telling between 10a and 10d. Could this lead to risk? Yeah, but this sport is not golf. It’s supposed to be a bit exciting and sometimes dangerous.

Because I want other climbers to experience the surprise and struggle of the sandbag, and the ultimate success that comes from pushing ourselves beyond our perceived limits, I’ve continued the tradition. My latest hobby is routinely sandbagging the routes at my local climbing gym. New routes are graded there by consensus, with each person selecting between three grading options with a checkmark. To do my part, I forge different-looking checks in each box of the lowest grade to insure that the gym remains heinous. I know it’s not much, but it shows that I care and am doing my part to keep everyone honest.

One of the core benefits of sandbagging is that it helps us realize our true potential. Some of my best onsights have happened thanks to a sandbag. A quality sandbag can trick you into realizing that your capabilities are far beyond your expectations. We all need to get sandbagged now and again to grow and become better climbers. That’s why I urge you to sandbag your friends, like Rob Pizem did to us. It’s the right thing to do.

Also Read

- Massive New Route on Trango II; 90-Minute Ascent of ‘Thor’s Hammer’; Ontario’s Climbing Is at Risk

- How Ethan Salvo Went From V1 to V15 in Five Years

- Are These the Eight Closest Calls in Climbing?

The post Cedar Wright on “The Value of a Good Sandbag” appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

"Cars, trucks, and vans have been the unsung silent partners in the progression of our sport. We love our cars. We name them, live in them, and for better or worse, are utterly dependent on them to explore crags and send the gnar." (From 2016)

The post Cedar Wright: A Brief History of My Mobile Homes appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

No car, no gnar—it’s a fact. John Salathe, the true OG of Yosemite big wall history, famously arrived in the Valley in an old Ford Model T. Then he forged his first pitons from the axle stock of that same car. And no one stormed the Valley in more motorized style then the Legendary Warren “Batso” Harding. He established more than 30 first ascents in Yosemite but was better known “for driving fancy sports cars, often having a good-looking woman on his arm, and drinking red wine from gallon jugs,” according to the LA Times. What a badass!

Cars, trucks, and vans have been the unsung silent partners in the progression of our sport. We love our cars. We name them, live in them, and for better or worse, are utterly dependent on them to explore crags and send the gnar.

Fast-forward to the modern age of car-dependent climbing, and we have the newly minted badass Alex Honnold pushing limits and blowing minds while living a slovenly existence in his Ford Econoline van. A veritable modern-day Warren Harding—minus the fancy cars, hot girls, wine, and basically everything that makes climbing cool.

My point is that we are so married to our cars that “climber rig” is a term in our community and how we travel in these rigs defines us. Road trips are a rite of passage for climbers. This has roots in the early history of climbing. Perhaps the most famous climbing road trip of all time went down in 1968 when Yvon Chouinard, Doug Tompkins, Dick Dorworth, and Lito Tejada-Flores drove a Volkswagen van from California to Argentina to make the first ascent of the California Route on Patagonia’s fearsome Fitz Roy. Today, most climbers, from dedicated dirtbags to dabbling weekend warriors, dream of a road trip half as badass.

When I first arrived in Yosemite, I made my grand entrance in “The Blue Stallion,” a beat-up, leaky clunker of a 1987 Mazda 4×4 with more than 200,000 miles on it. I drove it as little as possible to prevent stranding it at the crag, only putting on select miles for the seasonal drive to Joshua Tree and back. I envied the more well-off climbers with their pimped-out vans and the girlfriends that accompanied them, but I was more concerned with prolonging my permanent climbing vacation than creature comforts. Life back then was a delicate existence, hinging completely on a terminally ill truck. If the sickly vehicle broke down, my entire dirtbag dream would crumble, a prospect that gave me nightmares.

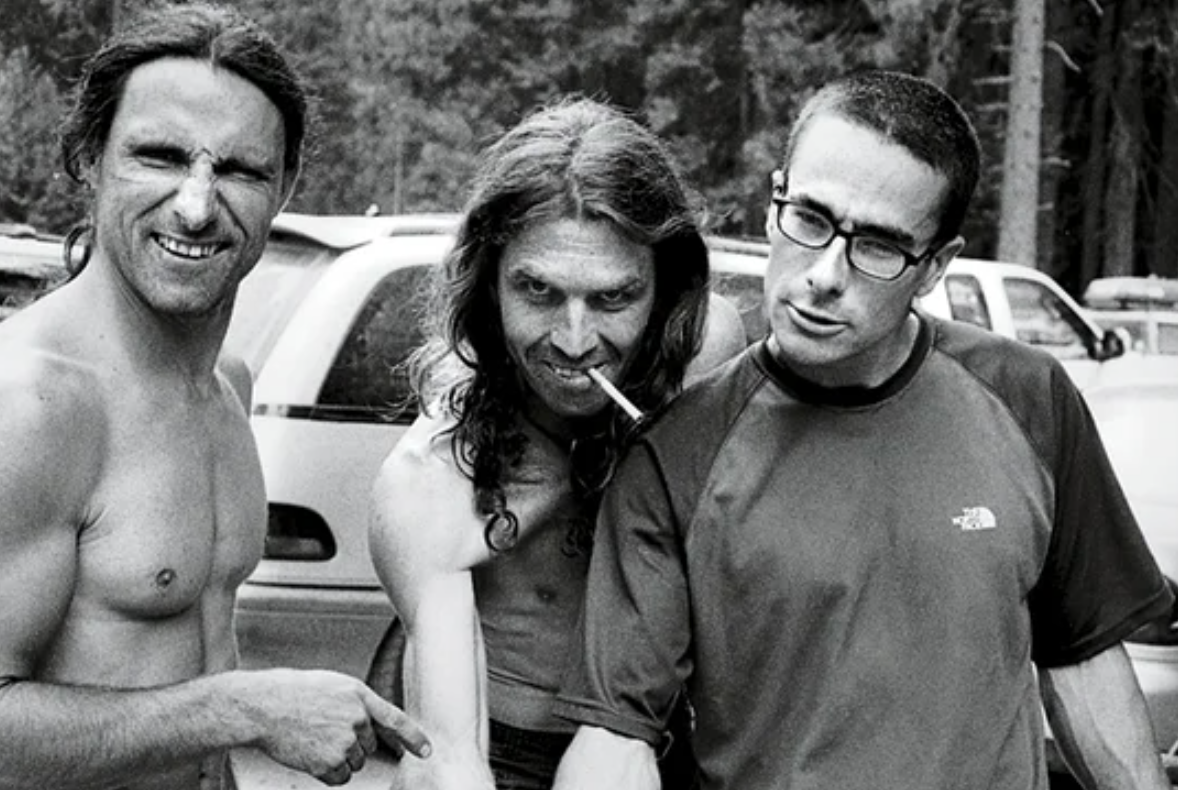

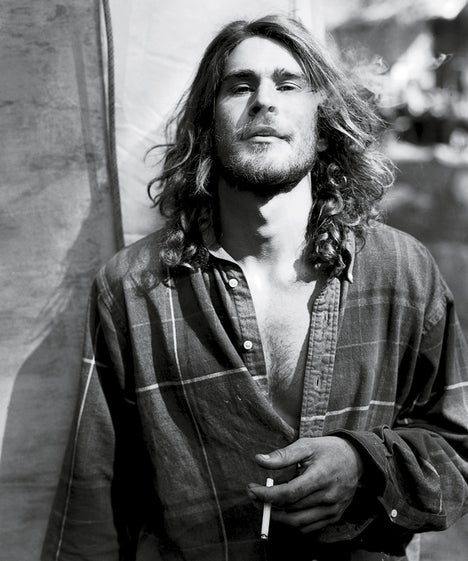

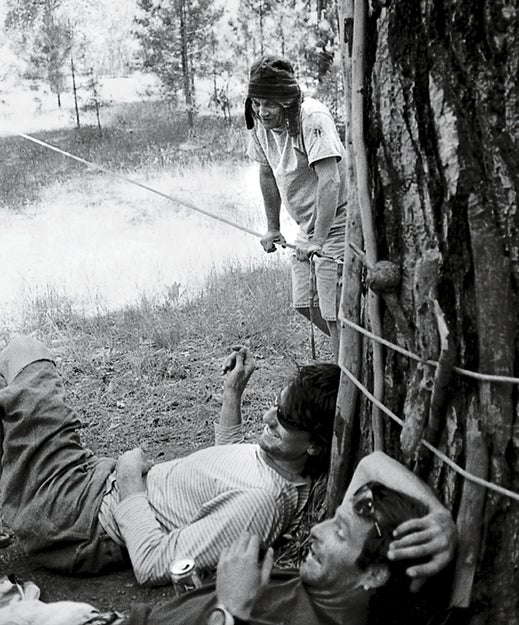

A few years into my dirtbag “career,” that sad and inevitable moment slapped me in the face. The Blue Stallion let out one last fumy gasp on a dirt road that shall remain unnamed, because, irresponsible knucklehead that I was, I stripped the plates and abandoned it. I had reached the four-alarm dirtbag state of emergency. I needed a rig, and I needed it fast. Conventional logic might have led me to step off the road for a bit and save up for a nice ride, but I needed to keep climbing. I begged, borrowed, and scraped together $500 to buy a slightly rusted 1989 Toyota Camry. When you go down the list of classic climber cars, the Camry is glaringly absent, but “Silver Lightning” became my reliable soldier for more than 10 years. While I slept in tents, caves, and for a while the SAR site behind Camp 4, Silver Lightning was for all practical purposes my true home. For a couple of years, I even had a roommate: my good friend and climbing partner at the time, Renan Ozturk. He was one of the few people even dirtbaggier than me and didn’t own a car, so he moved into mine.

Renan was an awesome climbing partner but a horrible roommate. Once he accidentally spilled an entire gallon of milk in the backseat. The rancid smell haunted me for years. To this day, I cringe at the smell of cheese. On another occasion, he forgot an empty sardine can in my car, and a crafty Yosemite bear ripped the passenger door completely off. Undeterred, the next day Renan and I road-tripped sans door through a snowy night to Utah, blasting the heater and wearing expedition down jackets while spindrift buffeted our faces. We suffered marginal frost nip, but survived. Actually, it’s one of my top five alpine achievements.

The next season in Yosemite the opportunity to upgrade came. An eccentric 60-year-old dude named Richard arrived in a Toyota Dolphin, basically a compact RV that gets decent gas mileage. Richard, the world’s only tennis bum, wanted to off load the Dolphin and return to Hawaii, where he lived in a ditch next to the tennis court and offered yuppies lessons in exchange for food. Richard offered to sell me the rig, but I had no money.

After some haggling, I traded Richard a sleeping bag and a ride to the airport for his Dolphin. A screaming deal, I thought, until I found the rat infestation. Then the mechanic doing the smog inspection told me it would be a thousand dollars to get it up to speed. I cut my losses, trading the Dolphin for a bag of weed from a colorful local named Denise, a mullet-wearing, hardened mother figure for Valley dirtbags. I pulled the Dolphin onto her property just outside the park and beached it there. A few weeks later, the neighbors found the dilapidated RV to be such an eyesore that they fire-bombed it. Denise was bummed, but a trade is a trade, and I’d already smoked all the weed.

Apparently luxurious van life just wasn’t meant for me. Silver Lightning was to be my sole form of transport through my tenure as a dirtbag and into my more established years as a homeowner and husband. I reached a point where Silver Lightning was a mark of pride for me, as well as a bit of an anti-materialistic statement and shout-out to my roots. When Silver Lightning finally died, it was deeply traumatic. I had so many of my stories wrapped up in her. She was more than a car; she was a companion. In some ways a car is like a dog. You bond with it, but it’s not going to live as long as you, so eventually you have to let it go—and it can be painful.

While living in a sedan made me an anomaly, the next generation was bound to come around. My good friend James Lucas, now an editor at this esteemed publication, was one of the few who had the dubious honor of picking up said torch, and his Saturn was arguably shittier than my Camry. He once asked me, “Do you know what it’s like to have sex in a Saturn?” “No,” I responded. “Me either!” he quipped. Yes, it’s harder to get laid living in a car without a real bed, but vans make you soft and require less ingenuity with the ladies.

Over my 15 years with Silver, climbing rigs have evolved. Fewer full-time dirtbags meant drastically improved rigs. Patched-together Volkswagen buses and clunky utility vans were replaced by luxurious and expensive Sprinters, which would become one of the most popular climber vans of all time, and for good reason. There are a lot of New York City apartments that aren’t as spacious as a nicely built-out Sprinter. Recently a Sprinter owner served me freshly baked cookies after a day of climbing in Rifle, Colorado.

However, the Sprinter is now being usurped by other brands. Hayden Kennedy went with the Dodge ProMaster because it’s cheaper, more square, and therefore easier to equip. Honnold followed suit. Many climbers are going for the Sprinter-esque Ford Transit. Joey Kinder just purchased the newly released Sprinter 4×4, perhaps the most baller climber’s rig ever. That bastard traded in his infamous maroon Astrovan for a car that costs as much as a mortgage! One of the more impressive rigs I’ve ever seen was a 4×4 Sportsmobile owned by the legendary inventor of the

V scale, John “Verm” Sherman. Verm had satellite television and a fridge so he could drink cold beer and watch sports at the crag.

Of course, vans aren’t for everyone. With a topper or camper shell, the Toyota Tacoma is the epitome of a climber’s car for four-wheel-drive approaches. An informal poll on my Facebook page showed that plenty of climbers swear by the Subaru, with the Outback and Forester getting praise for the ability to fold down the backseat and sleep in them.

In many ways a climber’s car reflects their personality. Some folks keep their rigs immaculate and organized. Others live in a constant state of chaos, like the junk show that was Silver Lightning. Somewhere in my trunk was everything I needed, the only trick was finding it. Once I stumbled upon a year-old petrified turkey avocado sandwich, and on another occasion, I racked up in El Cap Meadow for an in-a-day ascent, only to leave all the doors wide open.

A couple of years after Silver Lightning’s passing, I found my new companion in a blue Dodge Grand Caravan that my wife lovingly named “Big Blue.” With a comfy mattress in the back, Big Blue perfectly suits my current lifestyle. She’s soccer mom fast, making her efficient for weekend road trips with my wife, and a few times a year, I take Big Blue for an extended road trip.

We as climbers need cars, but the elephant in the room is that we should probably all drive less. I look forward to a time when I can get in my self-driving electric van and take a nap while road-tripping to Yosemite with a very low carbon footprint. But we’re not there yet.

The evils of emissions aside, we just can’t help but love our cars. For climbers a car is more than an engine and four wheels. It’s a ticket to our dreams, a path to that epic project or far-off crag. Much like a horse in the wild West, our cars are our trusty steeds, just as important as the carabiners and cams on our racks.

This article originally appeared in 2016 under the title “The Wright Stuff: Ride the Lightning” Cedar Wright was a contributing editor for Climbing. He’s a professional climber, filmmaker, and world-class goofball who resides in Boulder, Colorado.

The post Cedar Wright: A Brief History of My Mobile Homes appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

"I have a 'two degrees of poop' separation theory, that every climber either has a poop story of their own or a story about a friend somehow getting covered in poo." (From 2015)

The post “Many of My Proudest Climbs Have a Poop Subplot.” appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

What is it that sets climbers apart from the skiers, surfers, runners, and every other extreme athlete? What makes us special? The answer is, of course, quite nuanced and complex. But, I can say with heartfelt conviction that, when compared to other extreme endeavors, climbers crap their pants a lot. And that is special. I have a “two degrees of poop” separation theory that every climber either has a poop story of their own or a story about a friend pooping their pants, or in some other manner getting covered in poo. It just comes with the limited defecation resources we endure in the vertical world.

If you’re like me (and I hope you’re not), you don’t have just one crappy story. You have enough to fill an entire issue of Climbing magazine. Sadly, the editor shut down my dreamy pitch of putting out the mag’s first ever “Poop Issue,” and has limited me to 900 words. So, most remorsefully, I can’t play the whole discography, just the, ahem, greatest shits.

5. Mud Falcons

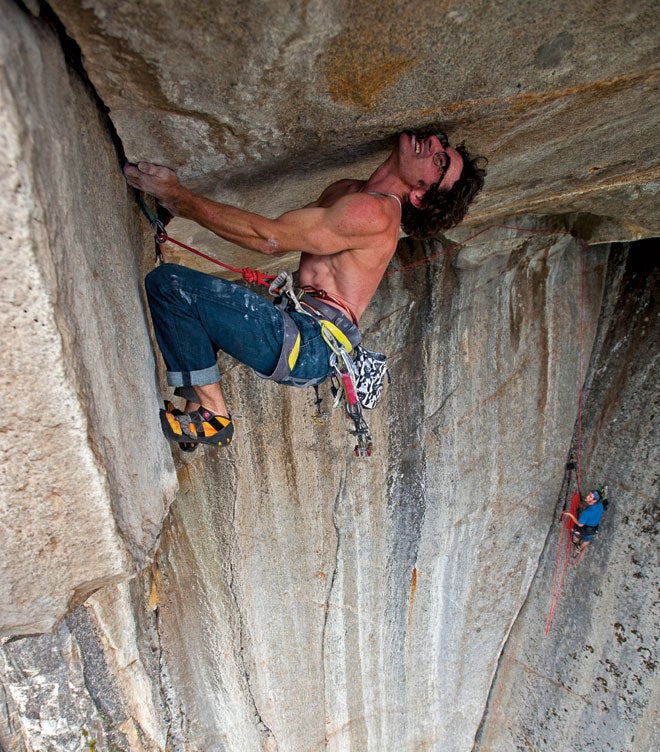

A high ratio of the best poo-tales involve El Capitan, for obvious reasons. El Cap is really big, and if you’re not climbing it in a day, you are almost certainly going to have to drop a #2 up there, unless perhaps you have some crazy Jedi powers over your sphincter—I have heard tales of a guy who held it for seven days on the wall.

While an emergent turd on the ground is a bit of a bummer, on El Cap… oh, man. You literally have to be on your shit, and this means pooping in a bag and bringing it down in a “poop tube,” unless you break the law and toss your poop down in a bag. More than one climber has been hit directly by a “mud falcon,” but I’ve only had one explode at my feet and pepper shrapnel against my legs.

While it may diminish your exposure time, climbing El Cap in a day doesn’t necessarily keep you safe. For instance, the day that Chris McNamara and I climbed The Shield in a day together, there was no time for bathroom breaks. I set a blistering pace. I’d soloed the first 5.10 pitch and was placing a couple pieces of gear per pitch. In less than an hour, we were nearly a thousand feet up the wall, and I had reached easy ground and was running and climbing like a heroic/idiotic maniac. I reached a small overhang and jumped gymnastically to the lip—double-dynoing my hands right into a big fresh steamer! The poop squirted up between the spaces in my fingers and splattered Pollock-like onto my face. “FUCK! FUCK! FUCK!” I shrieked. Chris probably thought I was about to take a hundred foot whipper and rip us off the wall. I did my best to scrape the stink-pudding off my hands, but Chris was yelling, “Go, go, go!” and before I could get it all off, my desire to set a record overtook my disgust. By the time we summited 10 hours later, thousands of feet of granite had scoured most of the trauma off my hands, but the stench lingered in my fingernails until I made it down to the valley floor and jumped in the river.

4. Speed Records

Now that I think about it, many of my proudest climbs have a poop subplot. One of my big breaks into becoming a pro climber came when I starred in Sender Films’ “First Ascent.” In the climactic scene, I manage to thrash my way up a burly unclimbed roof crack. What most people don’t know is that while racking up, I gambled and lost, trusting a fart that I shouldn’t have.

“Dudely, you just shit your pants; that’s no joke,” my partner, the legendary Bulgarian Ivo Ninov, exclaimed. Undeterred, I scooped the shart out of my pants with a rock and then fired the route. Watch the film again; you can just see a faint silver dollar-sized stain on my pants in a couple of the scenes.

3. Scared Sh*tless

I still consider my trip to Baffin Island with Jason “Singer” Smith to be one of the proudest and most difficult expeditions of my life. We managed perhaps the first grade VII big wall ever done in a single push—and I almost managed not to shit my pants. Halfway up the 4,000-foot A4 route, we climbed through a fresh rock scar from massive rockfall that had narrowly missed us earlier in the day. I stemmed past giant, teetering blocks the size of refrigerators and at times swam up what could be best described as vertical rubble. In a full survival panic, I accidentally kicked off a softball-sized rock, and it nailed Singer, shattering his kneecap. The only way off now was up and over, and Singer could barely jumar. I got off route several times, and we started to wonder seriously if this would be our last climb. In all the terror, I had shut off nature’s call, but as I neared the summit and it began to look like we might survive, I relaxed and a five-alarm crap was suddenly on deck. I frantically scooted up a chimney, reached a ledge, and at the speed of light dropped my pants. So close. I’d gotten my pants down around my ankles, but in the heat of the moment, I still managed to deposit the whole load right into my pants. It was a pretty extreme crap.

2. Ancient Art

Not all of my poop stories involve super-extreme climbs! One of my favorites happened on perhaps the most-climbed desert tower in the world. A certain mountain guide friend of mine had an emergent moment while taking a client up Ancient Art in Utah. A sudden and violent diarrhea overtook him, and at the end of the first pitch he realized that he had no choice but to do the unthinkable and defile the ledge. He took his harness off, draped it on the ledge, and as he relieved himself, the harness, rack, and rope all fell 20 feet down to a ledge below. As his client yelled up wondering what was taking so long, he who shall remain unnamed soloed down, retrieved his harness, and then used all the water in his reservoir to rinse the poo off before his client could follow the pitch. “What’s that smell?” the client asked. “I think the party above us shit here.” My friend replied, “Super disrespectful!” I’m sure the client wondered why they found no one above them at the top.

1. Boogie ’till you…

Now I’ll recount quite possibly the most famous pants-shitting story in the history of climbing (if not the modern world). For those of you who are living in a vacuum, Google “Boogie ’til You Poop,” and you’ll witness probably the most hilarious climbing film you will ever see. To summarize, my good friend Jason Kruk, having had one too many brewpub beers the night before, gets his knee stuck in Squamish’s 5.11b offwidth Boogie ’til You Puke, while I was filming and Andrew Burr was taking photographs. I went down to rescue Kruk while Burr turned his camera from stills to video mode to capture the magic. In order to support his free leg and help him get out, I was right below him with my face three feet from his ass when Jason began to panic, dry-heave, and then audibly shit his pants not once but twice. On occasion I actually get people who recognize me not for my climbing endeavors, but for being “that guy who got shit on in that video.”

Jason went on to do a “web redemption” on the Comedy Central show “Tosh.O.” Jason handled the whole unfortunate situation with humility and a good sense of humor: “Basically, if you climb enough offwidths,” he said, “you’re going to get your knee stuck and shit your pants. It’s an odds thing really. I’m just glad I had a professional photographer and videographer there to capture it so I can remember this moment for the rest of my life.” I think part of the reason the video was so popular is because we can all put ourselves in that position. In some ways there is nothing more human than shitting your pants. We all love. We all cry. We all shit. And no group, except perhaps infants, seems to shit themselves as often as climbers.

Cedar Wright is a former contributing editor for Climbing. He’s a professional climber, filmmaker, and world-class goofball who resides in Boulder, Colorado.

This article originally appeared in the September 2015 issue of our print edition.

Read More: “Who the F#$% bolted this?”: The Five Stages of a Sandbag

The post “Many of My Proudest Climbs Have a Poop Subplot.” appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Editor’s Note: What you are about to read contains a plethora of illegal activities, dangerous climbing techniques, and unsavory lifestyle choices that are in no way condoned or promoted by the editors of Climbing magazine. Read at your own risk.

The post Climbing Fast, Loose, and Dangerous with Yosemite Legend Ammon McNeely appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Editor’s Note 1: Ammon McNeely, the legendary El Cap pirate, passed away on Saturday, February 18, after an accident in Moab. Details of the accident are still emerging, though Gripped has reported it was not climbing related. We have a comprehensive obituary in the works, but in the meantime here’s Cedar Wright’s great celebration of his friend, which first appeared in Rock and Ice No. 204 (September 2012).

Editor’s Note 2: On September 3, 2017 McNeely was seriously injured when he struck a wall while BASE jumping near Moab, Utah. Due to the severity of his injuries, McNeely’s right leg was amputated below the knee.

My nerves were shot, and I leaned my head against the cold, blank granite of Iron Hawk (VI A4) on El Cap, just for a second of reprieve. The sensation of falling suddenly jolted me. I shrieked and applied an arm-cramping death-grip to my aider with my battered hand. My other arm spun to keep my balance … but … I wasn’t falling. I whimpered and watched the knifeblade shift again.

“Ammon, watch me here!” I yelled. No answer. Just the disconcerting rumble of my belayer, Ammon McNeely, snoring. Racing to get in a piece, I fiddled in a cam hook, and put two fingers through the webbing to clip it just as the knifeblade blew. I was airborne. The rope snapped taut on Ammon’s belay device, rudely jerking him awake. Some lessons are learned, forgotten, and then relearned in perpetuity. Mental note: Never climb with Ammon again!

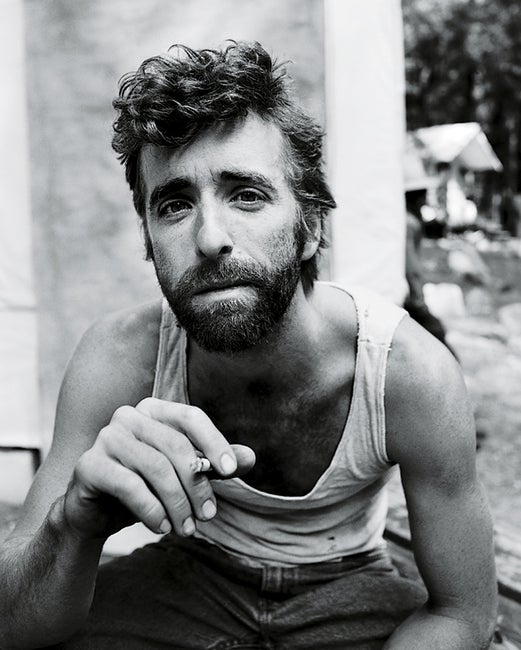

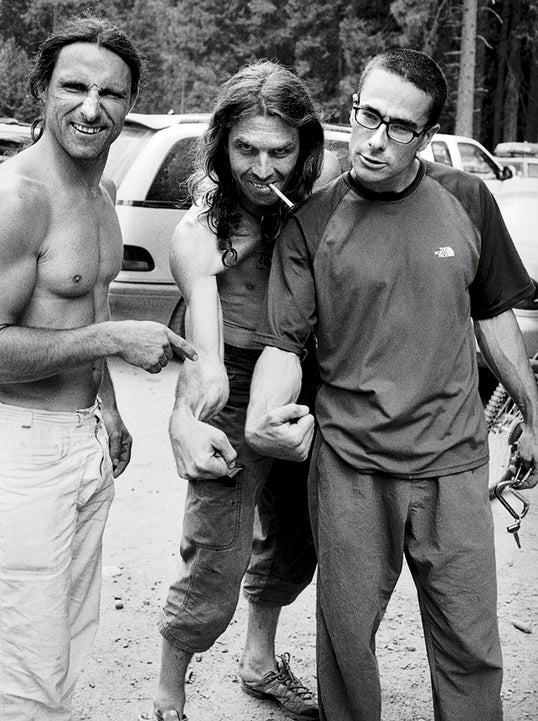

Climbing is a refuge for iconoclasts who want nothing to do with the common ideas of “success,” and instead choose to follow their passion down an alternative path of exploration and vertical ascent. The pantheon of our sport is rich with characters such as Jim Bridwell, Warren Harding, and Fred Beckey, who climbed hard and lived even harder, embodying a nonconformist lifestyle that placed experience and hedonism before financial gain.

Now, it seems, climbing is mainstream. Every city has at least one gym and a generation of grommets doesn’t know Royal Robbins from Baskin-Robbins. Some might argue that the era of the colorful, rule-breaking climbing maverick has ended. For those saddened by this notion, I have two words: Ammon McNeely.

Ammon does not remember the first time we met, but I understand why. If I’d ingested as much Olde English as he had that evening, I’d be too busy getting my stomach pumped to recall much. It was 3 a.m. in the Camp 4 parking lot. Having completed, many hours ago, my nightly ritual of stacking boxes and bags over my truck’s mattress to create the illusion of a vehicle too packed with gear to house a sleeping dirtbag, I was peacefully bandit-bivied in the cocoon that was my trusty “Mazda-Ratti” pickup. Somehow I awoke on a pirate ship.

“Arrr, matey! The seeeas arr rough toni-i-ightee, matey!”

My rig shook violently as Ammon fell awkwardly against my truck. My precarious stack of gear shook, shifted, and caved in on me. “Aye, me legs gonna give thee way to thee whennches, says meee.”

What in the hell was that? Something about weak legs and girls? And then the Beastie Boys, full blast. If you were in Camp 4 in the spring in the late 1990s, and if at 3 a.m. you were woken by “Listen all y’all it’s a sabotage,” and thought, “Who is that asshole?”

Ammon, of course!

“TURN THAT SHIIIIIIT UP!” someone yelled.

At this point the music was making my ears ring.

I popped my head out of my truck. “Hey, guys!” I said in an irritated tone. Heads turned and pupils dilated in shock. Before me on a tarp of clusterfucked climbing gear wavered two weathered and burly modern-day pirates, leaning on each other for balance.

“AYE, thar’s been a stowaway on the ship tonights, matey!” said one.

“Who goes there?” demanded the other.

“Cedar,” I offered meekly. A quick assessment of the situation told me it was time to make friends.

I was able to piece together that they were the brothers Ammon and Gabe McNeely, and that they were racking up to climb Pacific Ocean Wall, a

rather difficult route on El Cap. I was incredulous on several levels. A: I was certain this was a fool’s errand. B: There was no way I believed Ammon when he said, “We set sail at first light.” C: There was no way these guys were going to make it more than a few pitches before they bailed. To my disbelief, after I spent an entertaining hour of watching them fall down, get up, then haphazardly shove gear into haulbags, they began the long stagger to El Cap. One haulbag was filled almost exclusively with cans of Olde E.

By 6 a.m. they were climbing.

They didn’t fix lines; they just blasted off. For several days I’d cruise out to El Cap Meadow and spy them, each time a few pitches higher. I was impressed. These guys were hardcore. They also weren’t hard to find. Each day I had to smile as they hoisted a skull-and-crossbones flag from their portaledge “crow’s nest.”

It looked like they were going to defy my expectations until the mother of all storms unleashed its hellish fury, slamming the Valley with 60-mile-per-hour gusts and a torrential mix of rain, hail and sleet. On day two of the two-week storm, I grew concerned and ventured to the meadow to check on the pirates,

perilously adrift in a rough sea of granite. The swirling fog and relentless rain parted for less than a minute—just long enough to spy their camp two-thirds of the way up the wall, getting pummeled by a waterfall. My heart sank; this is how people die on El Cap.

Eight days later, by no small miracle, they oozed into the Yosemite Cafeteria, smelling and looking like death. They had been trapped for over a week in their portaledge waiting for the weather to clear. By day five they had finished off all the beer and food. Finally the scales tipped from “waiting it out” to a dire reality: bail or die. When they started rappelling, they were soaked to the bone, delirious and hypothermic. Had I been up there, I surely would have perished, possibly by unclipping and jumping. Their 2,000-foot descent entailed hip belays, extreme down-aiding, exploding bolts, and disappearing haulbags.

After that season Gabe headed home, but Ammon augured hard into the Valley. Spring became summer became fall as he knocked off one hard El Cap route after another, always hoisting his skull-and-crossbones flag, and returning with tales of huge falls and other near-death experiences. Ammon was on his way to becoming a Valley legend when he got arrested.

Fresh off an epic A5 solo sufferfest, Ammon headed for dinner at the Garden Terrace Buffet. Already a few too many celebratory beers deep, he neglected to pay before he ate. When a security guard approached, all Ammon had to do was pay, but the half-wild beast in him took control and trumped logic. He booked. Even that would have been OK if he hadn’t circled back through the parking lot a mere five minutes later, just in time to bump into several rangers and security guards trolling the parking lot.

“That’s him!” yelled a guard. The chase was on. The lack of a headlamp was but one of Ammon’s disadvantages. He sketched a few feet into the forest, only to look back at the approaching flashlights, and tripped over a root. He picked himself up, scrambled a few more feet, looked back, and ran into a tree. The rangers finally caught up with him crumpled in the talus.

Ammon spent hard time in the Yosemite Jail, aka “The John Muir Inn.” It wasn’t his first visit and it wouldn’t be the last. In fact, Ammon is well liked and on a first-name basis with the guards. I had a friend who went in recently for drunk biking and asked if he could wear McNeely’s orange jumpsuit, a request met with smiles.

In 1997 Ammon returned to the Valley with a skateboard. At the time the “Center of the Universe” was a parking lot across from Camp 4, where the dirtbags parked their cars for the season, and met to socialize. On Ammon’s first day back in the Valley, he was ollying off the tailgate of my truck when he landed too far back and shot the skateboard up into his face. Blood was everywhere, and a huge gash across Ammon’s cheek definitely needed stitches. Instead he duct-taped the cut and the next day headed up to solo the Sea of Dreams. The super-manly badass face scar remains to this day.

A year later I landed a climbers’ dream gig: a spot on Yosemite Search and Rescue, which meant enough work for a hand-to-mouth existence and a shanty at the back of Camp 4. I was the king of the world. I honed my skills on Yosemite’s endless supply of long free routes, and on my rest days I hung with Ammon and the rest of the “Rock Monkey” clan. We’d meet in the morning for coffee at the lodge cafeteria, then head to the Center of the Universe, or The Office, a nook in the woods designated for Safety

Meetings.

By then most of the regulars had acquired retired Yosemite rental cruisers, and my old-school Stonemaster friend Bullwinkle (Dean Fidelman) and I invented a game called “Bike Wars.” It started as a gentleman’s competition of strategy, where, with both on bikes, you try to get in front of your opponent’s bike, edging him toward an obstacle. If he put his foot down, you gained a point. We introduced the game to Ammon, whose strategy was less gentlemanly. He’d grab you in a headlock, then ride you toward a parked car. If you didn’t put your foot down, he’d crash headlong into whichever vehicle was in his path. I have a distinct memory of the two of us rolling violently up onto the hood of a BMW.

While I had become a decent crack climber, I wasn’t much of an El Cap climber. My only attempt at an in-a-day ascent of Lurking Fear had taken 40 hours and entailed heinous forearm cramps, debilitating dehydration, dropped headlamps and a shiver-bivy. But when Ammon asked if I wanted to climb the Zodiac in a day, I said, “Hell yes!”

The day before our big climb, the de facto “spiritual leader” of the Monkeys—Chongo—offered his wisdom and support. Chongo is famous for having written a big-wall book that is larger, heavier, and more inscrutable and open to interpretation than the Bible. There are three chapters on carabiners alone. Five years before, Chongo had actually coached Ammon up his first big wall in exchange for beer and grass. Surprisingly, his advice to us was solid.

“Cedar will do all the free climbing,” proclaimed Chongo, “And Ammon will do all the aid. Dean Potter short-fixes. You should short fix, too.

“And remember: Bitchin’ is a state of mind.”

We decided to bivy at the base. The Zodiac loomed above us as we set up camp. Ammon made a six-pack of King Cobra disappear, and entertained himself yelling and making ape calls to the 20 or so climbers on the wall. I joined in and soon we had all of El Cap alight in flashing headlamps and banshee wails. Around midnight Ammon passed out in a circle of cans. I was jumpy, and my nerves weren’t allowing much sleep. El Cap is sooo big. A thousand what-ifs gnawed at me. When the alarm went off at 4 a.m., I had barely slept a wink.

“Just a bit more sleep,” Ammon muttered before rolling over and turning off the alarm. I drifted in and out of nightmare-ridden restlessness. I met first light with a mixture of relief and dread. So much for the 5 a.m. start. It was 8:30 a.m. when I pushed start on the stopwatch. The first lead block was mine.

I climbed 30 feet, then whipped 28 feet down the wall. Ammon laughed like a pirate. “Get back up there, matey!” he boomed.

“Fuck it!” I yelled and in that moment I became possessed by Ammon’s infectious gung-ho spirit. I bat-manned up to my high point and attacked the wall: back-cleaning, blindly trusting, and in general being a dangerous dumbass.

The night before, we had discussed how awesome it would be if we could finish in less than 20 hours. We were halfway up the wall in less than four hours. We could hear ape calls from the other Monkeys in El Cap Meadow. A small crowd of our friends had gathered to watch the action. We were rock stars, hooting and hollering our way up one of the best big-wall climbs in the world as if it was a day at the crag. Nine hours later I clicked the stopwatch at the top of El Cap. Neither of us could believe our time.

“And remember: Bitchin’ is a state of mind.”

We received a heroes’ welcome on the Valley floor: A couple of nobodies had nearly broken the record on one of El Cap’s most famous climbs. Drinks and tall tales flowed at the Mountain Room Bar that night. Then Ammon got arrested for his specialty: disorderly conduct. They let him out the next day, and he said the food wasn’t half bad and the beds were “pretty comfy.”

That year Ammon went on to climb several other difficult big walls in record time with other climbers, and Chris McNamara and I managed to break the speed record on the Shield. Our commitment to climbing was paying off. Slowly we were carving out our own little piece in the Valley’s storied climbing history.

But by the end of the year, Ammon’s wild ways and one too many trips to the John Muir Inn came back to haunt him. The Valley Court handed down the dirtbag death blow. Ammon was declared “persona non grata” and banned from Yosemite for one year. Returning early meant big fines and real jail time.

That coming spring Ammon and I rapped in to a burly big-wall first ascent on the obscure SuperNova buttress in Yosemite. Both of us had a lot to lose: Ammon his freedom, and me, by association, my spot on Search and Rescue. As there was no great approach from below, we had thrown off 1,000 feet of rope for the rap in. The wall was so steep the rope went straight to the ground without touching rock.

Somehow Ammon had packed his belay device away and he figured it would be fine to rappel on a Munter hitch with a 100-pound haul bag clipped to his harness. Almost instantly the Munter spun him rapidly in circles. Since he had no wall to brace against, the farther he went down, the faster he spun. By the time he reached the base he was spinning so fast I couldn’t tell arms from legs. Upon touchdown he puked in the bushes.

What followed was my first experience with “hard” aid climbing. On pitch five I watched Ammon hook out an overhanging wall for 20 feet with nothing between him and the anchor. He pasted in a “bomber head,” then hooked for 35 more feet. PING! Ammon was airborne. The rope snaked about in the air as he spun his arms to stay upright. He fell more than 70 feet and past the belay. I was white-knuckled and nauseous, but Ammon just laughed. Then the copper-head blew and he factor-twoed onto the anchor. Now he was another 40 feet below me. I was mortified.

I sent him the jumars so he could get back up to the anchor. He cracked a beer, and we discussed options. I threw out possibilities such as bailing or drilling a bolt. Both suggestions were met with disgust. Ammon slammed the beer, then sent the pitch, which involved 80 feet of hooking with no protection! It was a pretty easy pitch to clean.

The most dangerous hooking pitch in the world brought us to a 30-foot horizontal roof with only a hairline seam in it. It was my lead, but all I saw was certain death.

“Look there in the roof,” I said. “I think it says ‘McNeely’ on it.”

Ammon quickly racked up and set off into the unknown, and I bore witness to the most impressive and ballsy aid climbing I’ve ever seen. He leaned hard off the anchor and tapped a bird beak about a sixteenth of an inch into the incipient seam in the roof. He clipped his aiders in and had me lower him onto the piece. To this day I cannot believe that beak held. Literally just the very point of the beak was into the rock! Then he went into full superhero pirate mode. He clipped his chest harness in and pressed his legs hard against the aiders, stretching horizontally with his back to the abyss. He reached out as far as he could and placed another bird beak that was even shallower than the first one.

Just then two rangers arrived at an adjacent cliff to investigate reports of an illegal highline. The highline had already been removed, but we were in full view, and a good friend happened to be shooting photos of us. When the rangers asked who was climbing, our buddy was forced to make up some less-than-believable-sounding names. “Oh, that’s Armando McMenez and Caesar Left,” he said sheepishly. The rangers bought it!

Oblivious to our near miss, Ammon reached out and clipped his aider into the next beak. I couldn’t believe it even held its own weight.

“Lower me very slowly,” he said, with just a hint of fear in his voice. We locked wild eyes. The beak held! Unbelievable! He repeated the acrobatic rigging maneuver and, again horizontal in the roof, reached out to a far mini-seam. If he fell now, he would slam upside-down against an unforgiving spiky wall. Breaking bones would be a best-case scenario. Two more tipped-out bird beaks and a shitty copperhead brought him to a “bomber” double-zero TCU in a loose flake. Defying logic, sanity and the laws of physics, Ammon pulled around the roof.

Now it was my turn. I had already given up one lead, and couldn’t give up another. I was hoping for a sweet A2 crack but was greeted by a shallow bird-beak seam. I got up about 20 feet off the portaledge and begged Ammon to let me drill a bolt.

“Don’t make me cut the rope!” he half-joked. I stepped onto another beak and was flying. I landed in the portaledge just as the rope went tight. Only a few times in my life have I wanted to bail more than I did in that moment, but pride got me back up to my high point, and a desire to make Ammon proud got me to the end of the pitch without drilling. A couple of heinous, dangerous pitches later, we had topped out on our proudest big-wall first ascent.

Though my time as a Valley dirtbag eventually came to an end, Ammon has remained rooted in Yosemite—pushing the limits of big-wall climbing to places I never believed possible, safe or sane. Ammon is still a lovable rogue, but he has toned down the drinking and his run-ins with the law have been less frequent. Though Ammon has gotten into BASE-jumping in recent years, his first love will always be El Cap, where he holds more speed records and first in-a-day ascents than anyone, by a wide margin. In an era where shirtless douchebags with beanies down-rate each others’ lowball choss nuggets, Ammon McNeely is strong evidence that climbing will never be mainstream. In fact, it seems like climbing is doing just fine.

The post Climbing Fast, Loose, and Dangerous with Yosemite Legend Ammon McNeely appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

"Lucho shouldn’t be up here. Not because this particular situation is dangerous (it is), but because it’s a miracle that he isn’t in prison."

The post How Climbing Saved Cedar Wright and Lucho Rivera From Their Downward Spirals appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

The rope arches in an unbroken loop from me to Lucho, 30 feet above. “At least there’s no rope drag,” I quip, trying to make light of his predicament. We are six pitches up the South Dragon’s Horn on Tioman Island, off the coast of Malaysia, living proof that climbing can go from fun to fubar in a microsecond.

A moment ago, we’d given knuckles at the anchor, raving about another classic pitch as we enjoyed a view of the jungle and the South China Sea below. Now, the good times are on hold. With accelerating gasps and groans, Lucho weasels in a small RP behind a suspect flake. He hurriedly clips a draw to it, gives it a tug, and promptly rips it right out.

He dances his fingers and toes back and forth on small nubbins, trying to devise a plan that doesn’t end with broken legs.

“Can you get a hook?” I ask.

“I don’t know, man…” Lucho’s voice quavers as he hunts his harness for the hooks.

“You’ve got this, man,” I say in a fairly less-than-convinced tone.

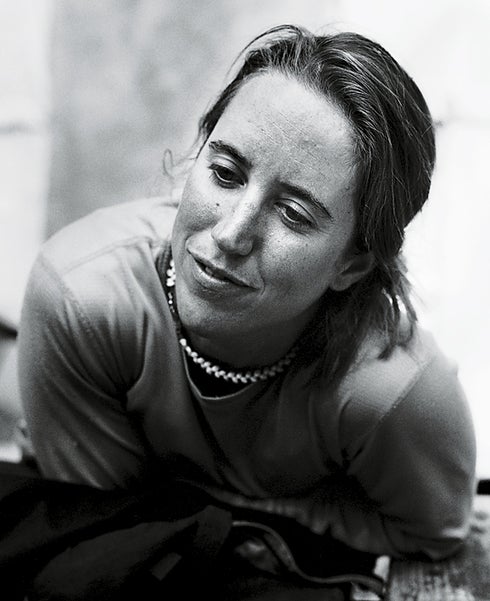

Lucho shouldn’t be up here. Not because this particular situation is dangerous—although it is—but because it’s a small miracle that he isn’t dead or in prison. Lucho grew up in a rough neighborhood in the concrete jungle of the Mission District in San Francisco, and by age 11 had joined a gang. “We’d hang out in the local park at night, walk up and down 24th Street, and try to control what people were walking around the block. If they were wearing blue, they’d get approached.”

The reality of Lucho’s life path became clear when he was about 16. He had gone with his crew to face off against a rival gang. “Everyone was talking shit, with bats and pipes, when the littlest dude of the bunch pulls out this Dirty Harry pistol and starts shooting. We all just started running. One dude got hit in the back. We dragged him into our car and blew every red light to the hospital. That was the moment where I was like, ‘This is fucked!’”

Lucho is just a stone’s throw above me, yet there’s nothing I can do for him but say, “Breathe. Relax.” He places a teetering hook on the hollow flake and slowly weights it. Ping! The hook pops off, slapping his chest, and Lucho’s body arches under the force. I can hear the scratch of his fingernails against granite as he puts the death grip on a micro-crimper. “Ahhhhh!” Lucho and I both scream in unison.

I really shouldn’t be here, either. When I was young, things were fine— great, in fact. While Lucho was a young gangster patrolling his block, I was happily bushwhacking across my family’s 11- acre northern California “hippie ranch.” I played in the dirt and climbed to the top of the huge trees that peppered our property. I was a lucky, happy kid. But somewhere along the pathway to adulthood, I got lost.

In high school, I buddied up to the cool kids, who reluctantly allowed me to hang around, though I felt more comfortable reading comics and playing Dungeons and Dragons with the geeks in the library. I was caught between worlds: too cool for one club and not cool enough for the other. I had no rudder, and I drifted to drugs.

I still vividly recall one low point: A mysterious smoke filled my 17-year-old lungs. For a moment I was indestructible; then I was a ghost. I watched my body fall backward into the street. My head made a loud thwackkk as it bounced off the blacktop. From a fetal position I could see my “friends” looming, laughing with distorted, clown-like grins, pointing their melting fingers as I convulsed on the ground.

I awoke to the sound of a car horn, and sat up face-to-face with blinding headlights. “Get the fuck out of the road, you idiot!” A middle finger popped out the window of the pickup as it careened past.

After high school, things got worse. Without my geek friends to bring me back to Earth, I floated away completely. For college, I chose the beautiful brick campus of Chico State—for its reputation as the “best party college in the world.” There was not a night that you couldn’t find a party on one block or another. I remember one evening watching a mob of drunken partygoers tip a car up on its side. This was not an isolated event. I became more morose and isolated. Somehow I managed to maintain a decent GPA, but I was an emotional mess. One morning I woke up covered in vomit in a ditch outside a frat house with no idea how I got there.

I didn’t have friends, just people I got high with, and pretty soon I was the go-to guy for a hookup. Acid, weed, ’shrooms— what do you need? By the first semester of my second year, the Feds were digging in my dumpster, and my breakfast came out of a blotter. After a particularly bad trip that left me bedridden for several days, I slipped into a dangerous depression. It’s amazing what we can recover from.

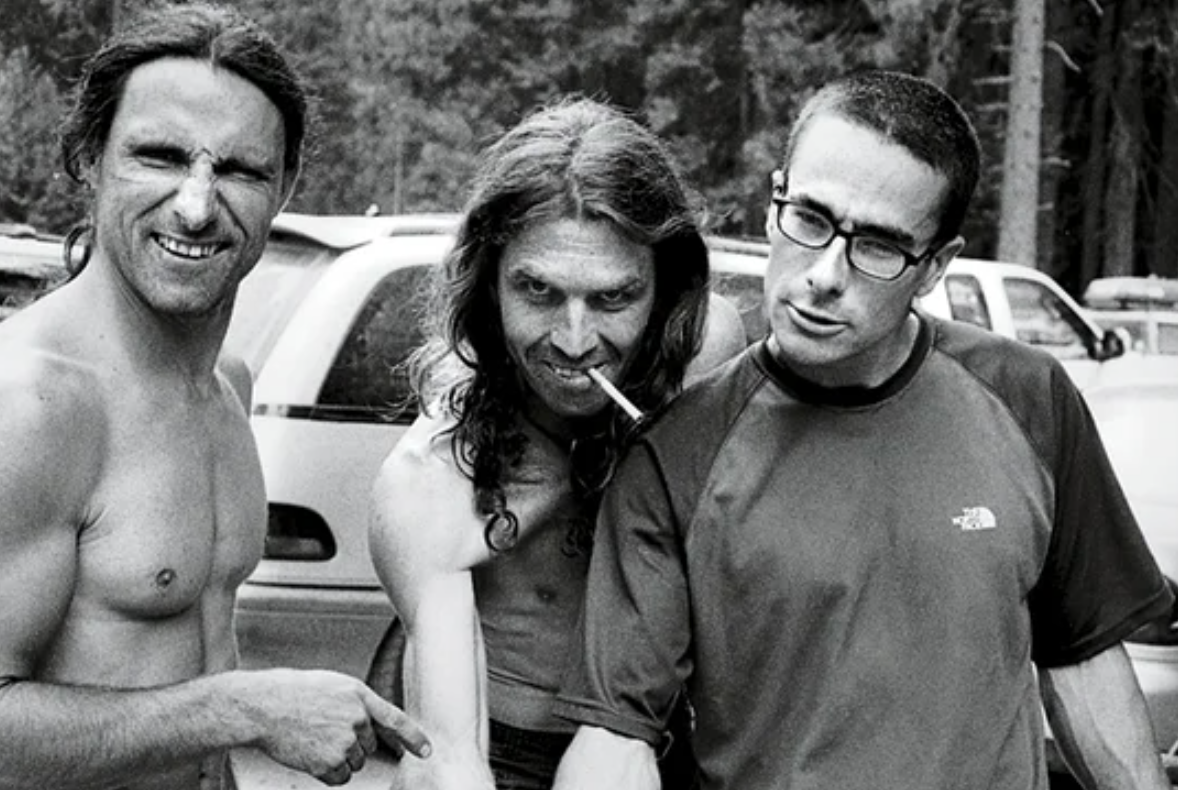

Having hit rock bottom in Chico, I managed to start a slow climb out of the darkness. I cleaned up my act, quit everything, even coffee, and transferred to Humboldt State. Walking Moonstone Beach one day, out on the mythical Lost Coast, I saw climbers dangling from the beach cliffs. “That looks badass,” I thought.

From my first climb, I was hooked. I spent my money on ropes and gear instead of bags and bongs. I climbed every day. When I burned through climbing shoes, I’d climb barefoot. I climbed in the blazing sun, and I climbed in the rain.

Soon after, I met the hardman Sean Leary, and I received a sandbag crash course in runouts, free soloing, and bolting from hooks. “Yeah, dude,” Sean said, “last summer I stayed in Yosemite for three months, and spent less than two hundred dollars.” I hurried toward graduation with my head full of dirtbag dreams. Screw getting a “real job.” I would live in my car, in places like Joshua Tree and Yosemite, and climb full-time on a shoestring budget.

For the little bit of cash I needed, I began working as an outdoor educator, sharing the passion that had saved my life. And why not? I was living proof that life on the rock was powerful therapy. I recognized myself in many of the kids: the insecurity, the aimlessness, the hidden potential. And I saw it work: The physical exercise, the teamwork, the beauty, and the separation from the influences of their daily life worked their magic on at least a few kids every trip.

I pushed through the grades and honed my crack climbing skills, in J-Tree in winter and Yosemite spring, summer, and fall. By my third year of full-time dirtbagging, I moved from outdoor educator to a spot on Yosemite Search and Rescue. I rubbed shoulders with the likes of the Huber brothers, Dean Potter, and Leo Houlding. In my eyes, these athletes were truly living the dream, a dream that soon became my own: to become a jet-set sponsored rock climber. A few speed-climbing exploits with Ammon McNeely and Chris McNamara put my foot in the door, and with a bit of luck and unadulterated desire, I started to pick up my first sponsors.

I brace for Lucho’s factor-two deathwhipper onto our anchor, but his survival instinct outguns the laws of physics, and somehow he stays on the rock. Spasmodically, he pushes the hook far above his head. It latches something unseen. Lucho eases, hyperventilating and wide-eyed, onto the blind placement.

“Are you sure that hook is good?” I call up nervously to Lucho.

“Don’t know man; want me to bounce-test it?” he snaps sarcastically, before delicately tapping at the hand drill.

A half hour later he slumps with infinite relief onto a bolt. “Dude, that was hella cool,” he boasts, his gangster bravado back. “We’re going to summit!”

By Lucho’s junior year in high school, he was rarely in class and facing expulsion. A school counselor suggested a program called Urban Pioneers, which gave kids school credits for a mix of classes and wilderness experience. Lucho was dubious, but felt he had no other option than a dead-end on the street.

Soon after joining, he was taken on a two-week backpacking trip into the Sierra. “I didn’t even know there was that much land,” he says. “I wanted to know what was on the other side of each ridge. Every day on the trip, when we got in to camp, I wanted to explore.” For the first time in his life, Lucho saw the Milky Way.

“At the start, there were kids from rivals gangs sporting their rags on the trail, and by the end of the trip they were homies,” Lucho says. “You had to stick together. Everyone had some piece of equipment that we needed for the trip to function.” On top of that, the instructors seemed to genuinely care. “I remember thinking that I’d never had a teacher like this who seemed to really give a shit about our lives.”

After that outing, Lucho and a couple friends from the trip returned several times to explore further into the Sierra. The small posse of ex-gangsters was quite the sight. One minute they’d brag how “hella easy” the hike was, and the next they’d be terrified, banging pots and pans to scare off a bear. The world had expanded for Lucho, and he was getting the same good tidings from the mountains that John Muir had gotten when he ventured out of the Bay and into the Sierra so many years before.

But Lucho’s old life haunted him. When he approached his gang leader about getting out, he got a chilling answer: “Blood in, blood out.” Translation: The only way you are leaving is dead. Lucho discretely tapered off his gang activities, and finally the crew approached him.

“I thought I was going to get shot,” Lucho says, “but they just told me I had to fight this guy.” The dude had been one of Lucho’s best friends in the gang. But Lucho just wanted to be free. All that desperation came out in a flurry of fists. “I kicked the shit out of him,” says Lucho. “Then he got up, shook my hand, and the rest of the guys were like, ‘It’s squashed.’”

Unlike most of his friends, Lucho graduated from high school. He got a job at The North Face Outlet in Berkeley. Several of the employees were climbers, and they gave Lucho his first taste of rock, on Bay Area crags. “One day they invited me to Yosemite to climb Higher Cathedral Spire.” The expedition turned into an epic, with off-route variations, slab whippers, dropped gear, and dehydration, but they summited, and the seed was planted.

But Lucho’s true turning point came at a slideshow at The North Face store. Jim Bridwell told tales of Yosemite first ascents, and Lucho thought, “Who is this crusty-ass old guy? He has done some badass shit.”

After the show, Lucho raised his hand and urgently asked Bridwell how he managed to defy the regulations and live in Yosemite full-time.

“I don’t know, kid,” Bridwell said. “We just did. We’d sleep behind boulders, move around a lot. We just stayed.” Soon after, Lucho went to Yosemite… and stayed.

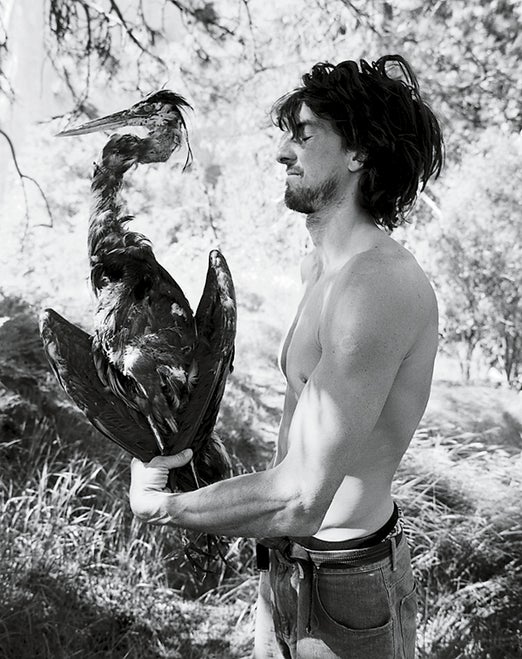

The arcs of my life and Lucho’s soon merged. I met him in the parking lot of Camp 4 three weeks after Bridwell inspired him to quit his job and move into his truck in the Valley. I was now a fairly seasoned Valley local, working on YOSAR. Though Lucho was a wide-eyed newbie, I was looking for someone—anyone—to help me out on my Gravity Ceiling project, a huge roof I wanted to free climb, many pitches up, near the top of Higher Cathedral Rock. I heard Lucho might be game.

Lucho’s learning curve was dramatic. In the year I met him, he went from epics on 5.9 to sending 5.12. Clocking one off the-beaten-path first ascent after the next, we started to get the reputation of being “choss masters.” Admittedly, not every FA was a gem, and some might be considered true suffer-fests, but our tortured pasts helped us find fun where others wouldn’t.

Years slipped by, and those times climbing in the Valley with Lucho started to seem like “the good ol’ days.” Each year I sojourned back to Yosemite, but also branched out to more exotic adventures. I established new routes around the world, fell in love, became a writer and filmmaker, and basically woke up feeling like a lucky bastard every day.

Lucho, meanwhile, continued to live the dirtbag dream, hanging tough in Yosemite, free climbing El Capitan, putting up obscure new routes, and only working as much as he absolutely had to. We kept in touch, and I think we were both a little envious of each other. “Dude, when are you going to get me on one of these sponsored trips?” he asked one day over the phone. “Don’t worry Lucho, I’ve got your back, man,” I promised him. “One of these days, I’ll hook a brother up.”

Fast-forward to 2011. An old college friend from Humboldt, Bennett Barthelemy, invited me to participate in a Big City Mountaineers fund-raising program called Summit for Someone. Big City Mountaineers’ mission was close to my heart: “to mentor under-resourced urban teens through transformative outdoor experiences,” and Summit for Someone was a program they ran to help good-hearted adventurers raise money for their cause. Bennett and I planned to put together a custom trip, using our industry connections and media savvy to raise a nice chunk of cash.

Bennett suggested an unusual objective: a pair of huge granite spires called the Dragon’s Horns, on Malaysia’s Tioman Island. He sent me a video link, and I realized that I’d actually heard about these obscure spires. My buddy Scotty Nelson had made the first ascent of the south tower. “It is definitely the coolest thing I have ever climbed,” I remembered him saying.

The project quickly built momentum. The North Face generously offered to match the first $5,000 we could raise. But then, last minute, Bennett had to back out. I scrambled to find a replacement.

I thought of Lucho. He had just finished a proud 5.13 first ascent on the Sierra’s Incredible Hulk. He was in the best shape of his life—psyched, but broke. With my end of the trip fully funded, I figured we could work that out. Lucho had never been overseas. I couldn’t help but feel like it was karmic: Lucho and I teaming up for our biggest first ascent, out in a jungle wilderness, raising cash to help troubled kids like the ones we used to be.

Our arrival on Tioman Island was surreal and abrupt. After three days of travel by plane, bus, ferry, and fishing boat, we dropped our bags at our rented bungalow, threw together some gear, and, in a jetlagged haze, hiked through the jungle toward the North Dragon’s Horn.

While details were sketchy, our Google/ Supertopo/American Alpine Journal search had revealed that the easier to reach South Horn had been climbed several times, but the North Horn was apparently a virgin summit. On the plane we had decided we’d first attempt the virgin north summit by the proudest line we could find, and then try to establish a new free route on the South Horn.

The jungle felt… pissed off. Every plant had a thorn on it, and we were thankful for our leather gloves. Huge ants swarmed everywhere. Some mystery bug was emitting a continuous, deafening shriek like a car alarm. I was immediately on edge.

During our journey to Malaysia, Lucho, the ex–street thug, had confessed that he was deeply afraid of snakes. And bugs. “Might be a problem, Lucho,” I warned. He had not been exaggerating. At every turn, he screamed and jumped at some real or imaginary critter. For me, the humidity and heat were the bigger battle. Sweat stung my eyes. My glasses fogged up. It was like hiking in a sauna.

Even though we’d packed our climbing gear, we assumed this would be a recon mission. But a few hours later, covered in scratches that were stinging from sweat, we found the steep granite of the North Dragon’s Horn suddenly looming above us. We could see huge sea birds playing in the thermals far above. Realizing we might actually get to climb, I was overcome by summit fever and began forging ahead through the jungle.

Suddenly, something that sounded like a hummingbird buzzed by my ear. More buzzing ensued, and then I felt a sharp, stabbing pain in my side, then another in my leg. I scrambled madly through the vegetation, reduced to a frantic, screaming kid. I reached back to a burning spot on my shoulder and snagged a huge, writhing object between my fingers. What I saw didn’t compute. It was a hornet, but larger than my thumb, with wild orange stripes across its pulsating abdomen. It squirmed as it tried to maneuver its stinger for another attack.

Thirty yards of frantic thrashing later, vibrating and hyperventilating, I was out of the swarm. A mix of poison and adrenaline surged through my body. Lucho had screamed and run in the opposite direction, beating a long retreat into the jungle. “You all right, man?” he yelled. Between us, dozens of pissed off mega-wasps divebombed their territory. “I think I’m OK,” I replied. I lifted my shirt to reveal a huge red-and-blue welt. Every gangster bone in Lucho’s body had evaporated, and it was only with my extreme coaxing, that he half-trembled, half-squealed his way in a wide arc around the swarm zone.

By the time he met me at the base of the tower, Lucho had recovered his bravado: “Dude, we got this shit fo sho.” I found his cocky outbursts equal parts hilarious and helpful in attacking the unknown.

Once we roped up, one pleasant surprise followed the next. The rock was bulletproof granite, with wild flake, knob, and pocket features, plus incipient cracks for protection.

As long as you didn’t mind 50-foot runouts and the occasional grass-hummock mantel, it was classic climbing. I tried to ignore the throbbing pains that were radiating from the stings while Lucho stretched out a sixth pitch and set up a belay under an overhang just as a bone-shaking crack of thunder announced a sudden downpour. The rain actually offered respite from the heat, and the stone was gritty enough to climb when wet. I found Lucho soaked but psyched at the belay.

As quickly as the rain had come, it went, and by the time I led the seventh pitch the sun had dried me out. My hornet stings began to throb as I belayed Lucho up. Then the clouds blew back in while Lucho led the eighth, and crux, pitch, with a hard 5.10 traverse 40 feet above protection. Wild cloud-to-cloud lightning began to flash around us, and another downpour hit as I started following the pitch. Was it possible to get struck by cloud lightning? By the time I reached the crux, a waterfall covered it. Facing a nasty pendulum, I held my breath, submerged, and somehow stuck to the crimpers that led to the other side of the cascade.

Past the hardest climbing now, we simul-climbed to the end of the rock. The rain subsided, and another few hundred feet of bushwhacking took us to the summit. Three days after leaving the States, we were the first documented humans on top of Tioman’s North Dragon’s Horn.

We climbed a spindly tree to get a view. The swirling clouds were on fire with oranges and reds, and we could see far into the interior of the island, where more wild towers protruded from green ridges, too far into the jungle to probably ever be climbed.

The idea of rappelling at night into the hornet-ridden jungle seemed less than awesome, so we open bivied on the summit. We awoke in the middle of the night and noticed that our bed of leaves was glowing, covered in a phosphorescent mold.

At around two in the morning, a new display of lightning convinced us to head down. All I could think about was hornets. But we made it down the wall and through the jungle without incident, and retired to our bungalow on the beach to enjoy a couple of rest days. I managed to get online and was happy to see that we’d already raised nearly $7,000 for Big City Mountaineers.

After completing the North Horn, we began scoping the south tower from various angles, consulting our notes to figure out where the three existing routes went. Eventually we realized that arguably the most beautiful line, an impressive Nose-like buttress, was unclimbed.

After three days of work, using fixed ropes to regain our high point each day, we were nearing the top on our South Horn dream route when Lucho ripped his hook and yet somehow managed to stay on the rock.

“Dude!” he said from the comfort of his newly placed bolt. “We’re going to the summit for sure. Hella cool,” he said, as he continued up the pitch.

A few days later we completed our new route to the top. During our forays we had freed every pitch, but the in-a-push free ascent remained. The monsoon was now upon us, and the weather socked in for several days. Lucho made earnest prayers to the mountain to allow us one last moment of passage.

Just before a month of nonstop fog and rain, we were granted a five-hour window of dry-ish weather, allowing us, just barely, to complete a free climb to the summit. We stood smiling on top of Tioman Island, looking out over the South China Sea, with a mass of clouds and lightning quickly approaching.

We let it all sink in: the surreal setting, the incredible climbs we had established, the many mishaps and mistakes in our pasts—all had somehow led to this moment. As we’d both experienced years earlier, there is nothing more transformative than colliding with nature on its own terms. Complications of modern life fade away. We are revealed to be fragile animals, in a beautiful and mysterious landscape. Climbing is dangerous, but for Lucho and me the alternative was infinitely more perilous. Climbing had saved our lives. A hard day out followed by a night under the Milky Way was our therapy.

“Dude, thank you so much for bringing me here,” Lucho said, with tears in his gangster eyes.

“It’s kind of a miracle we are here, huh?” I replied.

Cedar and Lucho raised nearly $10,000 to support Big City Mountaineers. Learn about Summit for Someone fund-raising expeditions and the Big City Mountaineers programs for urban teenagers at summitforsomeone.org.

Also Read

- New England’s Finest (and Sandbagged) Friction Slabs

- “I’m going to lose my leg”: How Rockfall Can Change Everything

- Saved by a Trail Line! Lessons Learned from a Rappelling Mishap and a 150-foot Fall

The post How Climbing Saved Cedar Wright and Lucho Rivera From Their Downward Spirals appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

In 2007 Cedar Wright and Renan Ozturk made an alpine-style FA of the 2,500-foot Northern Cat’s Ear Spire, the last unclimbed spire in the Great Trango Group. In the process he realized a thing or two about "style."

The post Cedar Wright: “It’s Bad Style to be Careless With Your Life” appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

This article originally appeared in Climbing in 2016.

I can’t breathe. Pumped, dizzy, and nauseous, I close my eyes, searching for composure. Crystals of static tingle and squirm between my brain and retinas. I gasp for oxygen, then thrutch up 10 feet of icy fist crack to the end of my rope.

“Hurgh,” I moan, using great effort to muster a shitty, unequalized anchor of a tipped-out #6 cam and two suspect stoppers. I slump against the wall, dry heaving. “Line is fixed, Renan.”