Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

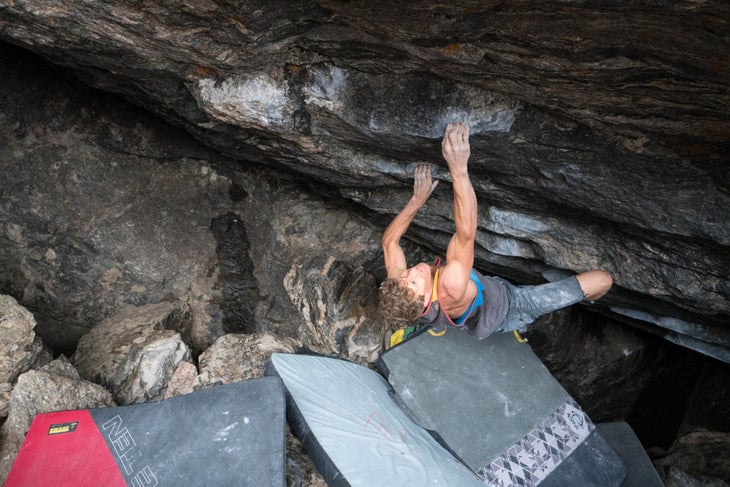

In the summer of 2014, bouldering icon Jimmy Webb established Flying Piñata (V12) on the Colossal Boulder in Upper Upper Chaos Canyon. Located above 11,000 feet, Flying Piñata was one of the highest-elevation boulder problems in Rocky Mountain National Park and revolved around a massive one-arm jump to a narrow slot that Webb called “one of the coolest moves I think you’ll do in Chaos.”

Eight years later, on June 28, 2022, 2.7 million cubic yards of rock and debris broke off the southeast slope of Hallett Peak, tumbling as much as 804 feet in less than two minutes before colliding with the Colossal Boulder and coming to a stop. The landslide registered on seismic stations 43 miles away and sent a group of climbers working a project south of the Colossal Boulder running for their lives, shrouded in dust.

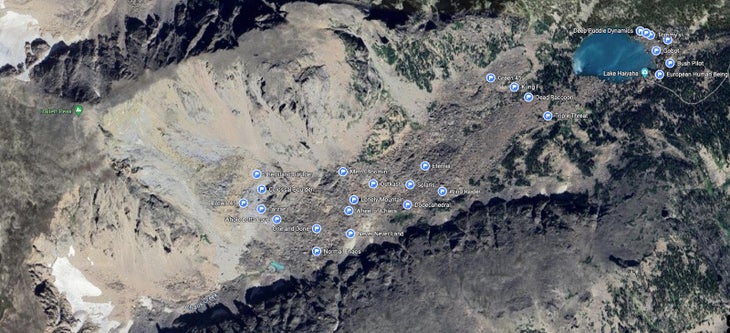

Bouldering in RMNP has been markedly different ever since. After the slide, the National Park Service closed Upper Chaos Canyon, rendering about 80% of the bouldering in the area inaccessible. Although climbing around Emerald Lake and Lower Chaos stayed open, many Colorado climbers flocked to other alpine areas to escape the summer heat.

Meanwhile, there was little optimism about a potential reopening in the months after the landslide. On the RMNP Instagram page, the National Park Service said in July 2022 that there was “no known time on when this closure will be lifted.” Jamie Emerson, author of the Rocky Mountain National Park Bouldering Guide, reported during a podcast interview last summer that a climbing ranger had recently told him the area was “closed indefinitely.”

But all that’s changed. Last month, the NPS officially (and quietly) reopened Upper Chaos Canyon, noting in its announcement that it is “a popular area for bouldering.” The opening represents nothing less than the start of another era for RMNP bouldering: Classics like Jade and Creature from the Black Lagoon will be rediscovered, while others will never be found. And new problems will inevitably go up on some of the many boulders that barreled down from Hallett Peak.

A new era for Chaos Canyon bouldering

Emerson, who first explored the area around the Colossal Boulder in 2004, assessed the fallout from the slide during a hike up Otis Peak. He told Climbing that some 15 boulder problems in Upper Upper Chaos had been destroyed or buried, including Flying Piñata and adjacent lines. More may have shifted in a way that changes the nature of the problems that ascend them.

Yet the potential for new lines is enormous, Emerson added.

On the day of the landslide, a number of individual boulders started rolling down the Hallett Peak slope at around 3 p.m. Then, an hour and a half later, two 80-foot-wide granite monoliths that had towered over Chaos dislodged and slid into the canyon, setting off the full slide.

The collapse of the Two Towers eventually formed a debris pile containing “15 to 20 house-sized boulders,” Emerson said.

“There are new opportunities now for people to go climbing on different boulders,” he said. “That’s pretty exciting.”

If climbers who return to the upper bounds of Chaos Canyon this summer find an array of quality, untouched rock, they’ll be reliving the experience of the first boulderers who adventured into the Rocky Mountain alpine, indulging in the minor absurdity of six-move first ascents over loose talus in the shadow of a 12,700-foot peak.

Dave Graham put up some of Upper Chaos Canyon’s first problems in the early 2000s, including the long roof climb Eternia (V11) and Skipper D (V8), one of the best moderates in the park. In 2007, Daniel Woods made the first ascent of what was known at the time as the Green 45 project and became Jade, perhaps the most famous problem in Chaos Canyon. Jade was graded V15 until the crux right-hand crimp—which Woods famously described as a “horseshoe razor blade”—improved after either breaking or being chipped, according to Emerson’s RMNP guide.

Alex Puccio bagged the first female ascent of Jade in 2014, and Czech climber Adam Ondra added to the lore around the problem when he visited Colorado in 2015 and flashed it. Graham, who sat below the boulder watching Ondra, called it “the hardest flash in the world” and “just, like, loco.” Ondra boarded a flight back to Europe hours later.

In the years between, Chaos Canyon saw a number of other historic ascents. Tyler Landman established Top Notch (V13) in a single day in 2008. Angela Payne became the first woman to climb V13 when she sent The Automator in Lower Chaos in 2010. Mysterious strongman Griffin Whiteside later put up numerous hard climbs around Upper Upper, including Boyz Gone Wilder Sit (V13) on the Upper Meadow Boulder. In 2019, Swiss climber Giuliano Cameroni added Blade Runner (V15) to the Green 45 boulder, and in June 2022, just one day before the landslide, Matt Fultz established one of RMNP’s hardest lines with his Brace For The Cure (V16), an extension of Jade. All of these problems were inaccessible during the canyon’s closure.

The Hallett Peak landslide was decades in the making

Curiously, bouldering development in Upper Chaos Canyon started at about the same time that the southern slope of Hallett Peak first showed signs of failure.

The Two Towers slid about 33 feet from 2000 to 2009 as temperatures around the Hallett Peak flank began regularly rising above freezing, according to a recent U.S. Geological Survey report. Movement accelerated in 2018, one of the warmest years on record. Between 2016 to June 2022, the Two Towers advanced about 174 feet downslope.

Kate Allstadt, the lead author of the USGS report, said during a January presentation that permafrost degradation due to the long-term warming and spring snowmelt likely triggered the slide. Allstadt also underscored the seemingly singular nature of the event.

“Most debris slides in the literature also became an avalanche or a flow,” she said. “This did not.”

As the Two Towers—along with adjacent boulders and debris—skidded down the south slope of Hallett Peak, they encountered the extremely coarse rock glacier on which Upper Chaos Canyon’s boulder problems sit. The sheer roughness of the rock glacier—that spiky surface that Colorado climbers know only too well—was one of the main reasons the landslide slowed and then stopped, Allstadt said.

For Emerson, who started bouldering in the park in his early 20s, the landslide adds a fascinating chapter to the history of RMNP bouldering, supplementing the stories of near-fatal lightning strikes and massive floods.

“It’s a dangerous place, and it’s an adventurous place,” he said. “For people like myself, those facets are really attractive.”