Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

What Are Plyometrics?1,2

We’ve all seen that climber at the gym who can effortlessly dyno to a hold five feet above their head, catapulting themselves upwards like a spring. If you have ever wondered how that’s possible or wanted to use big words like the stretch-shortening cycle or post-activation potentiation, consider investigating plyometric training. Plyometrics involve rapid muscle stretching and contraction to increase power production. For a climber, this means the ability to move quickly off a hold with a large amount of force. Enter the climbing dyno.

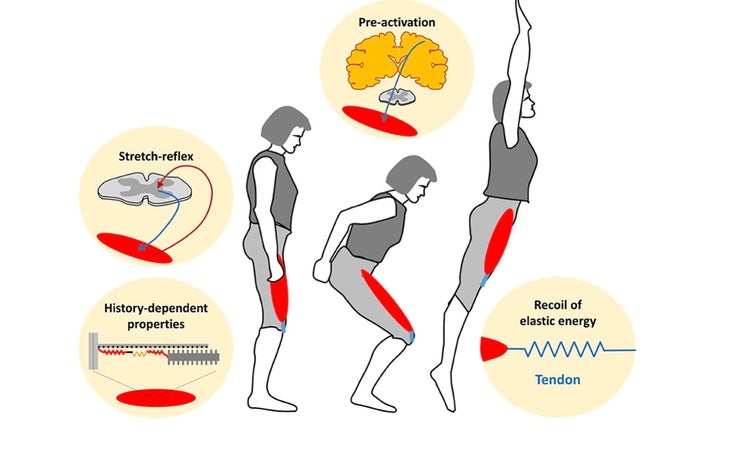

The more force a muscle can exert in one second, the more it will enable you to reach an inch further when moving dynamically. It is the combination of eccentric muscle action (the stretch) with concentric (the shortening) that actually increases power through a phenomenon called the stretch-shortening cycle (SSC). Very often it is a natural instinct to perform this countermovement like when you squat before performing a big jump. And studies show that the SSC helps individuals to increase their maximum jump height just by utilizing this muscle stretch during eccentric quad action before the concentric contraction to propel the body upwards.

The SSC is commonly attributed to three factors: the reflex exhibited by receptors, called muscle spindles, that respond to stretch with increased contraction of the muscle; the muscle action facilitated by the pure elastic energy stored in stretched tendons; and the addition of countermovement, which allows more time for the functional proteins of muscle fiber to contract.

This is how plyometric training increases muscle power. However, there is not a reciprocal increase in tendon stiffness just from these lower-load quick movements. Therefore, it is important to combine plyometric training with exercises targeting tendons such as heavy, slow loading or isometric holds. This type of training may have more of a place when training for bouldering which is often associated with dynamic problems, but there are more and more dynos seen in lead climbing competitions as well. Speed climbers can also benefit from power training, especially exercises that emphasize quick contact time. This article will assist you in choosing some plyometric exercises to implement into your training and how to keep them specific to the context of your training goals.

Assessment

Power production of the upper extremities can be measured most precisely with an accelerometer which can measure force and velocity during movements such as a pull up.3 However, there are other ways to assess upper extremity power production in the climbing gym. Two examples are something similar to the Power Slap Test4 which gives a unilateral height comparison of a single throw. An example on a common campus board can be seen in Figure 1, though note how this climber latches onto the rung instead of slapping as high as she can. To avoid the additional demand of having to recruit finger flexors and latch on, instruction can be given to just slap the wall as high as possible. Another option for advanced climbers is the Arm-Jump Board Test,5 seen in Figure 2, performed by going from hanging to jumping both hands up as high as possible on a campus board. If this is too difficult, a scaled version that involves foot holds may be appropriate, although it is not as targeted to just the upper extremities.

Figure 1. Power slap test4

Figure 2. Arm-jump board test5

Lower extremity power and reactive strength index can be measured best with a drop jump test where the athlete steps off a box onto a force plate to calculate the ratio of jump height relative to ground contact time. However, this can similarly be achieved without a force plate by simply finding maximum box jump height, Figure 3. Although this does not take into account ground-contact time, it could also be compared to maximum drop jump height which involves a decreased ground contact time, Figure 7. Other tests include a vertical jump test if a box is not available and a single leg jump test to compare side-to-side. Without having to do calculations or reference normative data, scoring can be as simple as comparing your performance overtime—seeing if you can hit a rung higher on the campus board or increase your box jump height.

Figure 3. Max box jump

Training

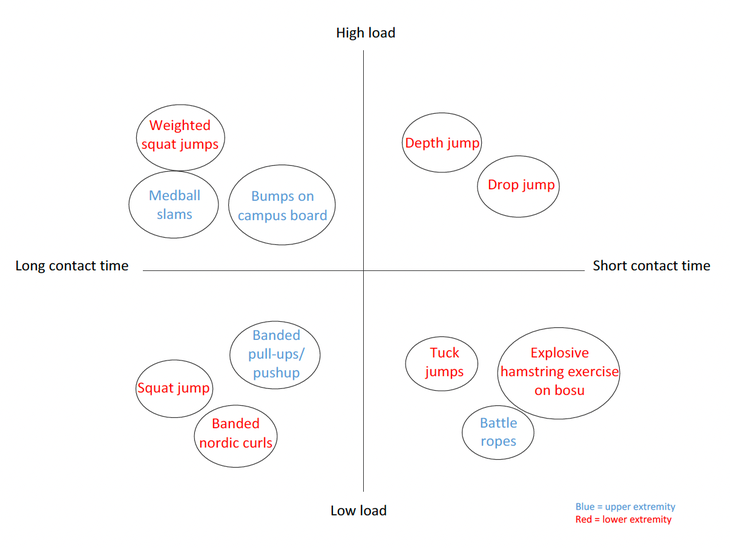

Plyometric training can be applied to the upper extremity for increased pulling or pushing power as well as the lower extremity for higher/quicker jumps. Training can additionally be made more specific by altering the amount of ground contact time and load. Decreasing ground contact time helps train reactive strength, the ability to rapidly change from eccentric to concentric. This can be achieved by utilizing cues to move the weight as quickly as possible. Load can also be altered but should not exceed 60-70% 1RM in order to maintain the ability for speed generation and effectively train muscle power. To achieve an optimal amount, load can be reduced using bands or augmented using weights. The movement should be easy enough that several repetitions can be completed quickly. The graph below features how the different exercises discussed in this article could be conceptualized according to load and contact time to best train a climber’s specific goals. It is one example of how load and contact time can be manipulated, but the exact placement of exercises on this graph and in relation to one another will vary based on each individual’s setup depending on factors such as the thickness of band used and the speed at which movements are performed.

Graph 1. Plyometric exercises organized by load and contact time

Upper Extremity Plyometrics

A plyometric push-up variation would involve the athlete moving through the motion as explosively as possible, even coming up off the ground as shown in Figure 4. For pulling power, plyometric pull-ups could be performed, as shown in Figure 5. These two exercises are shown with a band to decrease load closer to an appropriate 60% 1RM that can be moved quickly. But alternatively, weight could be added to a weight belt/harness or with a weighted vest if body weight is too light of a load to be adequately challenging. Other upper extremity power exercises include battle ropes, medicine ball slams, and bumps on a campus board.

Figure 4. Plyometric push-ups with a band

Figure 5. Plyometric pull-ups with a band

Figure 6. Bumps on campus board

Lower Extremity Plyometrics

Training lower-extremity power involves many jump variations depending on the goal of the exercise. For example, a simple jump squat with countermovement utilizes a larger ground-contact time and may be more relevant to train for boulderers, while tuck jumps utilize a lower ground-contact time to work on quick force generation and may be relevant to speed climbers. Box jumps, in addition to the assessment of power, can also be used to train it. Two variations are the drop jump and depth jump. The setup is similar, however the focus of the drop jump is maintaining stiffness in the leg muscles on landing and springing up as quickly as possible with minimal ground contact time, while the focus of the depth drop is to jump as high as possible. Again, depending on the goal of training, the quicker ground-contact time of the drop jump may be more specific to speed climbing than sport climbing or bouldering. However, they both provide the body with the challenge of having to stop the downward momentum after stepping off the first box which requires the maintenance of tendon stiffness and production of an explosive contraction to change direction and propel upward. These may be especially considered to train force absorption when landing after coming down off the bouldering wall. Lower extremity and upper extremity plyometrics can even be combined such as with a squat jump up to a pull-up bar, then a plyo pull-up to practice the rapid push through the legs and pull from the arms that is required by many dynos.

Figure 7. Drop jump

Figure 8. Depth jump

Lower extremity plyometrics don’t always involve jumping. Although the power for dynos typically comes from the glutes and quads which are targeted with the squatting and jumping movements, plyometrics for the hamstrings are also beneficial for climbers. This is the muscle that is going to allow you to powerfully pull up onto a ledge from a high heel hook. An exercise to train this is a nordic hamstring curl. These challenge the hamstrings significantly and can be modified by adding a band as shown in Figure 9. An example of a hamstring plyo exercise that requires quick contact time, is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 9. Band-assisted nordic hamstring curl

Figure 10. Explosive hamstring exercise on bosu

More Than Plyometrics…

Because power movements utilize the body’s type II fast-twitch muscle fibers, heavy resistance training which also recruits these fibers can help further their development. This type of heavy loading of tendons also has been shown to improve tendon stiffness which not only helps them transfer force quickly to muscle, improving power, but also helps prevent injury.6 Plyometrics and resistance training can even be combined with a training concept called post-activation potentiation (PAP) which involves pairing a high-force production-demand exercise with a high-power demand exercise. The idea is that the large amount of type II muscle fibers recruited to lift the large load have just been primed and are ready for the explosive movement that follows.7 PAP has been shown to improve power production over time and also serves as a good warmup to prepare the muscles before a challenging climb.7,8 An example warmup for the upper extremity could include doing five pull-ups at 85% of 1RM8 and eight squats or deadlifts at 50% 1RM for the lower extremity.9

When to See a Doctor of Physical Therapy

These exercises are designed to train power and assume a baseline level of strength. If you find the foundational exercises they are built on difficult such as squats or pull-ups, it would be helpful to work on these before progressing to plyometric training. If you have pain with training or climbing be sure to reach out to a physical therapist.

About the Author

This article was written through a mentorship process in The Climbing SIG, a rock climbing special interest group for physical therapy students developed by Dr. Jared Vagy DPT – The Climbing Doctor.

Sammi Iannucci completed her doctor of physical therapy at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and is now an orthopedic PT resident at the University of Southern California. In addition to climbing, her passions include movement analysis, advocating the need for resistance training, and preserving the capacity for continued sport participation throughout the lifespan. To contact Sammi with any questions or comments, you can email her at iannuccisammi@gmail.com.

About the Contributors

Dr. Jared Vagy “The Climbing Doctor,” is a doctor of physical therapy and an experienced climber, has devoted his career and studies to climbing-related injury prevention, orthopedics, and movement science. He authored the Amazon best-selling book Climb Injury-Free, and is a frequent contributor to Climbing Magazine. He is also a professor at the University of Southern California, an internationally recognized lecturer, and a board-certified orthopedic clinical specialist.

To learn more about Dr. Vagy you can visit theclimbingdoctor.com or visit him on Instagram @theclimbingdoctor or YouTube youtube.com/c/TheClimbingDoctor

Kevin Cowell is a physical therapist, clinical instructor, and rock climber based out of Broomfield, CO. Kevin owns and operates The Climb Clinic (located at G1 Climbing + Fitness) where he specializes in rehab and strength training for climbers and mountain athletes. He found his passion for climbing in Colorado while attending Regis University for his Doctorate of Physical Therapy and has since become a Certified Strength & Conditioning Coach (CSCS), Board-Certified Orthopaedic Clinical Specialist (OCS), and a Fellow of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Manual Physical Therapy (FAAOMPT).

You can contact Kevin via email at kevin@theclimbclinic.com or by visiting www.theclimbclinic.com. Also, be sure to follow Kevin at @theclimbclinic on Instagram for free rehab and strength training resources.

Julien Descheneaux is a master of physical therapy who dedicates himself exclusively to rock climbing injuries, having treated over 1,200 climbers. He’s been covering Quebec competitions as a certified Sport First Responder since 2014. He is also the author of the online class “Climbing injuries at the upper quadrant” for the Quebec PT Board (OPPQ) and gives regular clinics and conferences on the subject. He founded PhysioHR in 2016, the first PT clinic inside a rock climbing gym in Canada and is currently the resident PT at Bloc Shop Chabanel.

You can contact Julien via email at julienlephysio@gmail.com or by visiting https://www.physioescalade.com/.

Todd Bushman is a doctor of physical therapy, clinical instructor, Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist (CSCS), and climber of mountain, rock, ice, and plastic. Todd is a dedicated climbing specialist based out of Bozeman, MT where he practices full time. He is actively pursuing advanced training to become a Certified Orthopedic Manual Therapist (COMT) through the North American Institute of Orthopedic Manual Therapy. Todd is also available for remote consultation regarding climbing injuries, movement analysis, and strength training.

You can contact Todd via email at todd.climbingcoach@gmail.com or visit him @try.hard.pt on Instagram.

Carly Post is a physical therapist in Los Angeles, California. She is passionate about climbing and enjoys helping people move better and optimize their ability to participate in their lives to their fullest potential. She can be reached at carlypos@usc.edu and on Instagram at @carlypost

References

- Fukutani A, Isaka T, Herzog W. Evidence for Muscle Cell-Based Mechanisms of Enhanced Performance in Stretch-Shortening Cycle in Skeletal Muscle. Front Physiol. 2021;11:609553. Published 2021 Jan 8. doi:10.3389/fphys.2020.609553

- Kubo K, Ishigaki T, Ikebukuro T. Effects of plyometric and isometric training on muscle and tendon stiffness in vivo. Physiol Rep. 2017;5(15):e13374. doi:10.14814/phy2.13374

- Levernier G, Samozino P, Laffaye G. Force-Velocity-Power Profile in High-Elite Boulder, Lead, and Speed Climber Competitors [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 22]. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2020;1-7. doi:10.1123/ijspp.2019-0437

- Draper N, Dickson T, Blackwell G, et al. Sport-specific power assessment for rock climbing. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2011;51(3):417-425.

- Laffaye G, Collin JM, Levernier G, Padulo J. Upper-limb power test in rock-climbing. Int J Sports Med. 2014;35(8):670-675. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1358473

- Merza EY, Pearson SJ, Lichtwark GA, Malliaras P. The acute effects of higher versus lower load duration and intensity on morphological and mechanical properties of the healthy Achilles tendon: a randomized crossover trial. J Exp Biol. 2022;225(10):jeb243741. doi:10.1242/jeb.243741

- Seitz LB, Haff GG. Factors Modulating Post-Activation Potentiation of Jump, Sprint, Throw, and Upper-Body Ballistic Performances: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2016;46(2):231-240. doi:10.1007/s40279-015-0415-7

- Sas-Nowosielski K, Kandzia K. Post-activation Potentiation Response of Climbers Performing the Upper Body Power Exercise. Front Psychol. 2020;11:467. Published 2020 Mar 24. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00467

- Evetovich TK, Conley DS, McCawley PF. Postactivation potentiation enhances upper- and lower-body athletic performance in collegiate male and female athletes. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2015;29(2):336-342. doi:10.1519/jsc.0000000000000728