Pro tips and fuel ideas for any climber

The post 5 Climbing Nutrition Guidelines for Reaching Your Potential From Amity Warme appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Chances are, you’ve seen Amity Warme giving it her all on a route this past year. But Warme isn’t just a rising talent in the climbing world who’s impossibly fun to watch—she’s also a registered dietitian who specializes in providing nutrition guidelines to climbers and other athletes to help them reach their full potential.

Whatever Warme is doing when it comes to nutrition and training is clearly working. This past season, she put down the Vortex Trilogy—a series of three, under-the-radar multipitch routes on sandstone just outside Sedona, AZ: Cult Leader (5.13d, 5 pitches), Cousin of Death (5.13d, (5 pitches), and Dickel’s Delight (5.13c, 6 pitches). “Only a couple other people have sent all three routes so it felt like a worthy challenge and was really special to see it through,” Warme says.

When it comes to her own nutrition, Warme does her best to follow her own advice. She eats a wide variety of nutrient-dense foods, avoids being too rigid or restrictive, and makes sure she’s fueling adequately for the demands she places on her body through climbing and training. Some of her go-to fuel includes Greek yogurt with berries for breakfast, pita bread or bagels for on-the-wall snacks, and dried fruit for quick energy between pitches.

Read on for the climbing nutrition guidelines Warme follows to try hard on the wall.

As a sports dietitian, I work with a wide range of climbers from beginner to elite, including boulderers, comp climbers, trad climbers, and everyone in between. Despite the array of individual ability levels and interests, nearly everyone who comes to me for nutrition coaching wants to maximize their performance and general health.

The following are five guidelines to follow when it comes to nutrition to make the most of your training and (hopefully) send your project.

1. Underfueling will hold you back

In gravitational sports like climbing—where you are moving your body against gravity to accomplish the goal—there is a tendency to adopt the mindset that lighter is always better. That can make teasing out the nuance between discipline and disorder feel complicated.

I get it. Gravity is real, so we can’t ignore that nutrition is one piece of the performance puzzle. But chronic underfueling prohibits you from reaching your potential. Problems arise when too much emphasis is placed on low body weight. That’s because neglecting the importance of food as fuel impacts optimal performance, training adaptations, growth and development, and long-term health.

Why underfueling in climbing is a problem

Put simply, your body requires a certain amount of energy (calories) from food each day in order to maintain basic physiologic functions. This is called your basal metabolic rate (BMR). Adding in activities of daily living and exercise significantly increases the energy your body uses.

After subtracting the energy used for exercise, the energy left for physiological functions is called your Energy Availability (EA). If there is not enough to cover your BMR, your body will be in a state of Low Energy Availability (LEA). LEA can lead to Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs), which leads to a wide array of detrimental health and performance issues. Chronic underfueling, whether intentional or not, puts many climbers at risk for REDs and its associated symptoms.

2. You can’t maximize your training without proper nutrition

Athletes often come to me when they start a new training program in an effort to get the most gains for their grind. Establishing a proper fueling strategy before, during, and after your training sessions is crucial. This is what enables your body to achieve the training adaptations you’re looking for by spending all those hours in the gym.

Training is an anabolic stimulus for your body—you are prompting your body to make strength gains and respond to training. We want to use nutrition to augment and “convert” that workload into adaptations that will benefit your climbing. So how do we do that? By making sure we are properly fueling the training window. The goal is to bookend your workout with energy from food in order to buffer the stress of training on your body.

How to optimize your training through nutrition

Put in place nutrition around your training window. I recommend this dietary strategy from Tom Herbert of Useful Coach:

- Before training: Around 45-60 minutes before training, consume ~25-30 grams of protein, and a minimum of 60 grams of carbohydrates.

- Aim for simple, easily digested carbs like rice, oats, fruit/dried fruit, a baked potato, cereals, a bagel, and pita bread. Experiment with what works best for you. Most athletes will better tolerate foods that are lower in fiber and fat that are easier to digest before hard exercise.

- During training: If your workout or training session is longer than an hour, take in at least 30 grams of easily digested carbohydrates per hour.

- For these easy-to-stomach carbs, turn to bananas, dates, pretzels, granola, bars, or sport chews/drinks.

- Immediately after training: Eat at least ~25-30 grams of protein, and at least 60 grams of carbohydrates.

- Aim for nutrient-dense whole foods such as an animal- or plant-based protein source, whole grains, and plenty of fruits and veggies.

- If you don’t have time or access to a full meal right after your session, it is still important to replenish your body as soon as possible after training. Keep convenient, no-prep options in your car so that you have no excuse to skimp on recovery.

3. Fueling at the crag doesn’t have to weigh you down

Athletes often voice the concern of not wanting to eat too much and subsequently feel full or “heavy” while giving burns on their project. But at the same time, they feel frustrated by only having enough energy for a couple of good efforts before fatigue hits. To mitigate these issues, it is helpful to strategize both the timing and types of food you bring to the crag.

Here are some of my strategies for crag-day nutrition:

- Before you leave for the crag, start the day with a nutritious, well-balanced breakfast that includes both a protein source and complex carbohydrates. Don’t forget to hydrate here as well.

- If your day involves a long approach, eat a snack after the hike, before you start climbing, or as you are warming up. To ease digestion, aim for something higher in carbs, and lower in fat and fiber. For me, that usually looks like oats with fruit and other toppings, banana or apple, or yogurt with berries

- As you’re working your project, try to eat a snack after each attempt, right after you get back to the ground. This gives your body time to digest while you are resting and belaying your partner. By the time it’s your turn again, your body will have had time to convert that snack into available energy for your next attempt on the project.

4. Don’t delay multi-pitch nutrition until you’re bonking

It can be easy to forget to fuel appropriately on the wall when you’re always busy climbing, belaying, or dealing with gear and rope management. The goal is to stay ahead of your hunger and thirst on longer multi-pitch routes and on big walls. If you wait to eat and drink until you’re already famished, it will be much harder to catch back up.

This is the multi-pitch nutrition strategy I use to stay on top of my fueling:

- Fuel and hydrate well the night before and in the morning before starting your adventure.

- Pack foods that:

- You know you like and will be excited to eat

- Are not difficult or messy to eat

- You know work well for you and your digestion

- Keep snacks easily accessible by storing them at the top of your pack, in your pockets, or in an Avant Multipitch Snack Pack. This way you can quickly grab a bite while your partner is following the pitch or while you are racking up for the next pitch.

5. Your training weight doesn’t need to be the same as your performance weight

I see many climbers fall into the trap of striving to maintain their lightest possible weight year-round, for years on end. With training, we can’t expect to maintain peak strength, power, and fitness for years at a time. Likewise, with nutrition, it is not sustainable to be at “fighting weight” for an extended time.

Again, I understand that gravity is real. In theory, it makes sense that there would always be a positive correlation between losing weight and sending your project. But in order for weight loss to be used as a performance benefit, there have to be fluctuations. If you hold steady at your lowest possible weight year round, then you have nowhere to go and no room to use slight, strategic weight loss as a performance benefit when peak season on your project rolls around.

Certainly, not everyone needs to get this fine-tuned with their nutrition. But if you are truly seeking your limit, it can be worth exploring the idea of a training weight and performance weight. I would strongly recommend working with a sports dietitian to navigate the nuance of this.

How to strategically use “performance weight” to improve your climbing:

- Throughout the majority of the year, maintain a slightly heavier body weight and focus on optimally fueling your climbing and training. This allows your body and mind to make desired training adaptations, recover well between sessions, decrease risk of injury and illness, and generally thrive at a higher level of function.

- When the time comes for peak performance, you can strategically and conservatively aim to reduce body weight by a marginal amount (e.g., 2% of your total body weight). You can do this by choosing times of your day and week when you are less physically active to introduce a small calorie deficit, while keeping training and climbing nutrition in place as discussed above.

- The key is that this minor weight loss is acute, planned, and ideally managed with the guidance of a nutrition professional. Weight loss should occur before the performance period and focus should return to optimal fueling for energy and recovery during the performance phase. It is only reasonable to hit this performance weight up to two times per year and maintain it for a few weeks at a time, before needing to start the cycle again.

Amity Warme is a professional climber and registered dietitian. For further questions, get in touch with her at amitywarme.com.

The post 5 Climbing Nutrition Guidelines for Reaching Your Potential From Amity Warme appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Alcohol and climbing have a long history. A nutritionist dives into the pros and cons of crag drinks.

The post Do Climbing and Alcohol Mix? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Let’s play a game: Think of a beverage that goes well with climbing. Three, two, one … Let me guess, was it beer? From climbing’s countercultural roots, in which alcohol seemed to be a staple on walls and as an après celebration, to today’s scene with climbing gyms serving high-end beers on tap, it’s hard to separate drinking and climbing. In fact, according to Climbing’s 2018 reader survey, 43 percent of the magazine’s readers choose a cold beer as a post-climb drink.

However, as driven, health-conscious outdoor athletes, we also wonder, Is alcohol hurting my performance? There’s a lot to wade through here: nutritional and recovery implications; the safety considerations of climbing while drinking; the social/cultural aspects of drinking; and of course, the darker side—alcohol-use disorder (aka alcoholism). Let’s explore.

Nutrition and Recovery

If you’re serious about training gains, alcohol probably won’t help. In fact, there’s evidence that it can be harmful in more ways than one, including:

- Inhibiting recovery

- Decreasing reaction time

- Decreasing peak power the day after consumption (by delaying muscle repair and inhibiting coordination)

- Impairing cognitive function

- Increasing injury risk (due to impaired motor skills and decreased strength)

- Decreasing performance

- Interfering with glycogen restoration (glycogen is the storage form of sugar in your muscles and liver—the fuel that powers muscle contractions and helps keep blood sugar stable)

- Inhibiting sleep

- Increasing urine production/dehydration

- Interfering with protein synthesis (rebuilding and repairing muscle tissue)

- Speeding up digestion (can contribute to bowel issues like diarrhea)

- Providing extra calories (leading to weight gain)

- Decreasing thermoregulation (by way of reducing core temperature and increasing skin evaporation—both of which decrease workload ability)

- Decreasing blood sugar—may lead to hypoglycemia

- Decreasing testosterone production (males)

Taken as a whole, this list sounds pretty bad—and it certainly doesn’t synch up with climbing your hardest. Says Bill Ramsey, longtime 5.14 climber and a professor of philosophy at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, “Alcohol undermines your recovery, it dehydrates you, it diminishes strength gains from training, it fills you with empty calories …. It is just about the worst thing you can put into your body if you want to get stronger.”

And yet, some climbers seem to do fine with alcohol. Research shows that the effects are likely dose dependent, meaning one or two beers at a given time may not be a problem, but a binge-drinking session probably is, as is chronic overconsumption. It’s all a matter of degree.

The pro climber Paige Claassen drinks a glass or two of wine at night, and says, “I’ve never noticed an effect on my sleep, performance, recovery, or mental stamina.” One study in the journal Nutrients (2010) found that alcohol consumption at 0.5 grams per kilogram of bodyweight did not impact athletic recovery. For context, a standard drink in the United States contains 14 grams of alcohol (found in a typical 12-ounce beer). A person weighing 72.7 kilograms (160 pounds) would be able to handle 36 grams of alcohol, or about 2.5 beers, and, in theory, still enjoy adequate recovery from training. This finding is confirmed by a 2021 review in the International Journal of Sports Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism: Small to moderate amounts of alcohol seem to have little effect on muscle performance and recovery.

From a nutritional lens, your choice to consume alcohol may depend on various factors. If having one or two post-climb adult beverages would make the day perfect—as Claassen says, “It’s like a mini-celebration with my husband or friends to reflect on the day’s successes, efforts, and struggles”—go for it. On the flip side, it’s not recommended to consume alcohol the day before a big climb or comp. In fact, according to Zack DiCristino, medical manager for USA Climbing, the organization prohibits alcohol consumption for their comp climbers within 48 hours of and during a competition.

Safety + Climbing

Alcohol can inhibit critical-thinking skills, as well as gross and fine motor skills and reaction time. Our sport requires a sharp mind to place solid pro and anchors, tie knots, do safety checks, and climb efficiently. Specifically, alcohol affects the cerebellum, the part of the brain crucial for balance, spatial sensory perception, problem-solving, and skilled motor tasks—climbing, in a nutshell. Thus that “nerve-calming” nip of whiskey or beer before a scary lead can do more harm than good. Not only is your ability to climb hampered, but you’re less safe.

Says John Long, who recently wrote about his experience with alcohol-use disorder on Climbing.com (“Stonemaster John Long Comes Clean on Alcoholism”), “There’s no sport more unforgiving on safety errors. It’s not like you’re shooting baskets.” Long adds that even when he was struggling with alcohol, he did not drink while climbing. Recalling his time serving on rescue teams, Long says climbers should ask themselves, “Do I want to join the conga line of corpses of climbing accidents that happen often enough even when people are sober?”

Jonathan Horey, MD, board-certified in addiction medicine and psychiatry, is similarly blunt on the subject: “We know alcohol affects eye and muscle coordination. Any amount of alcohol will influence your brain. Reaction time and cognition are affected. Your ability to process information is slowed, as is the amount of information you can process.” (Um, what was that beta again? Did I tie that knot?) Horey adds that the way alcohol affects individuals varies based on genetics, weight, time since your last meal, and gender.

In short, it’s never a good idea to drink and climb.

Alcohol as a Social Lubricant

Enjoying food and drink is a beautiful part of life, but it’s possible to skip booze and still enjoy the meal and the company.

Alex Honnold, of Free Solo fame, has never had alcohol but says he still manages to party all night when the situation calls for it—as on his world travels. He thinks the emphasis on alcohol as a social lubricant is overblown. “I have plenty of friends who are occasionally wrecked from a big evening of drinking, and I certainly don’t envy them,” he says. “I’d guess that consistently not drinking … doesn’t make a huge difference in life, but it probably helps eke out that extra few percent at the top.”

Long’s opinion mirrors Honnold’s: “People who are trying to push the bar on climbing performance don’t drink alcohol. The two don’t mix. If you’re a weekend warrior or climbing for fun, you may be able to get away with drinking after climbing, but those who are climbing hard don’t drink.”

Jonathan Siegrist, a pro climber who has sent 5.15, skips alcohol when recovery is important, as during intense training periods. “But on a trip—especially in Europe or Asia—I have a drink every night or so,” he says. “Part of the experience of doing things like that is to drink the wine and eat the cheese—or drink the Bijou and eat the noodles if in China—and so I don’t want to look back at my life and think that all I experienced was rock.”

Nonalcoholic beverages

Like the taste of beer or the ritual of having a beer with friends, but not the hangover? Nonalcoholic (aka “near”) beer may be a good option. Keep in mind, however, that some brands still have trace amounts of alcohol—avoid these products if you’re a nursing mom, in recovery, or a comp climber subject to anti-doping testing.

As for beer’s touted health benefits, near beer may contain some polyphenols—which can act as antioxidants and help decrease the risk of chronic disease—plus have anti-inflammatory properties. And some studies (weirdly) show decreased risk of respiratory infection with regular near-beer consumption. Nonalcoholic beer can also be a decent re-hydration beverage, especially with added sodium, which is found in some brands marketed toward athletes. But beer is not the only food that contains polyphenols and anti-inflammatory compounds. You can also obtain these via a healthful diet of fruits and vegetables, nuts and seeds, whole grains, legumes, and omega-3 fats.

Alcohol-Use Disorder

If drinking for fun or for the social aspects is really just drinking to mask alcohol-use disorder, then you’re in trouble. The common “climb + beer” set on repeat may be a harmful pattern, especially if you’re using climbing’s countercultural roots to justify it. It’s a thin line.

How do you know if your drinking is a problem? Both binge drinking on weekends (defined as five or more drinks within two hours for men, and four for women) and regular drinking (more than seven drinks throughout a week) pose increased risk for alcohol-use disorder, which can have severe negative impacts on your health and relationships. Meanwhile, feeling desperate and living in extremes—as Long did during his worst years—is a sign of alcohol-use disorder. There’s an even darker side yet: Alcohol abuse is linked to increased sexual assault—as per the website alcohol.org, 69 percent of sexual-assault events involve alcohol use by the perpetrator, and 43 percent involve alcohol use by the victim. So stay safe in the wilderness by keeping yourself and your climbing partners sober.

Dr. Horey also urges pondering this: “How important is the alcohol to the experience? How much time and energy do you spend on acquiring, consuming, and recovering from alcohol use?” If the balance feels off, reduce your alcohol intake or seek professional help. (Consider organizations like the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation or Alcoholics Anonymous.)

So, should you have the beer? It depends. Take stock of your climbing goals, relationship with alcohol, immediate training plans, and social situation. As Ramsey says, “The trick is to try to find a balance. Some people do it easily and others not so easily. I (and other people I know) have completely cut out alcohol to send a hard project, and it definitely helped. But much of the time, I still enjoy a beer or two at the end of a climbing or training day.”

Marisa Michael, MSc, RDN, CSSD, is a board-certified specialist in sports dietetics and author of Nutrition for Climbers: Fuel for the Send. She has a private practice in Portland, Oregon. Find her online at nutritionforclimbers

.com or on Instagram @realnutritiondietitian.

Read this: Stonemaster John Long Comes Clean on Alcoholism

The post Do Climbing and Alcohol Mix? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Climbing your best requires finding alignment between what you eat, when you eat, and what you're trying to do.

The post Eat Right, Feel Better, Send Harder. It’s That Simple, Right? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

This article originally appeared in Climbing in 2017.

Does your climbing performance vary from day to day? Do you send hard only to feel like a wet rag the next time out? Do you feel a constant need to snack to avoid getting “hangry” or crave coffee to battle a midday crash?

The biggest gains in climbing come when your energy level is consistently high. This allows you to climb stronger, longer, and more frequently. Strategic eating optimizes energy levels and strength, and minimizes recovery time. After years of climbing in Northern California, experimenting on myself and working with clients to develop the Trailside Method, a four-week program of strategic eating for active outdoor lifestyles, I developed these strategies to help you eat your way to “next-level” performance.

Step 1: Eat Balanced Meals

Eating balanced meals and snacks will stabilize your energy at a high level, even out your appetite, and prevent midday crashes. Balancing meals and snacks means that every time you eat, you’re ingesting some form of carbohydrates, protein, and fat.

Carbohydrates

These are your body’s main fuel source—the gas that gets the car running. Carbs break down in your digestive tract to glucose, your body’s most readily available fuel, which then passes into your blood to fire cellular activity. How quickly you absorb glucose depends on the type of carb you eat. Both types come in refined (processed) and unrefined (whole) forms. Unrefined simple and complex carbohydrates are best: The easiest way to know how a carbohydrate is going to act is to eat it in its natural, unrefined state, as Mother Nature intended.

- Simple carbohydrates: These are the quickest source of fuel and the most easily digested. Because of this, your blood sugar will spike and crash rapidly. A simple carb is like trying to keep a bonfire going all night with newspaper, leaving you with short bursts of flames. Some examples of unrefined simple carbs include honey, molasses, and maple syrup, while refined simple carbs include cane sugar and high-fructose corn syrup.

- Complex carbohydrates: These have a carbohydrate structure that is harder to break down and usually present with fiber; therefore, they’re slower to digest, giving a steady, more gradually increased and decreased supply of glucose to the blood. Complex carbohydrates are a slow-burning log that gives off better heat and requires less maintenance. Some examples of unrefined complex carbs include most vegetables, legumes, nuts, and seeds, while refined complex carbs often come in the form of breads, pasta, and baked goods.

Protein

The protein structure is a chain of amino acids that your body breaks down and uses for different functions. The main function of protein in climbing is to aid in rebuilding muscle tissue after exercise. So, if carbohydrates are the gas for the car, protein is the mechanic repairing and rebuilding damaged parts at a pit stop. Animal proteins such as meat, poultry, eggs, and cheese are the best for repairing muscle tissues. Vegetarian proteins such as tempeh, legumes, whole grains, nuts, and seeds can also provide adequate repairing power if eaten together in a diverse diet.

Fat

The main function of fat is to slow digestion, to keep you full and control the rate at which you use your carbohydrate fuel. If carbs are the gas and protein is the mechanic, then fat is the brake pedal. Eating fat will slow down the digestion of both simple and complex carbohydrates. Some examples of good fats include avocado, nuts, olives, coconut, and butter.

Read More: Dieting for Climbing? Here Are Four Things You Should Know.

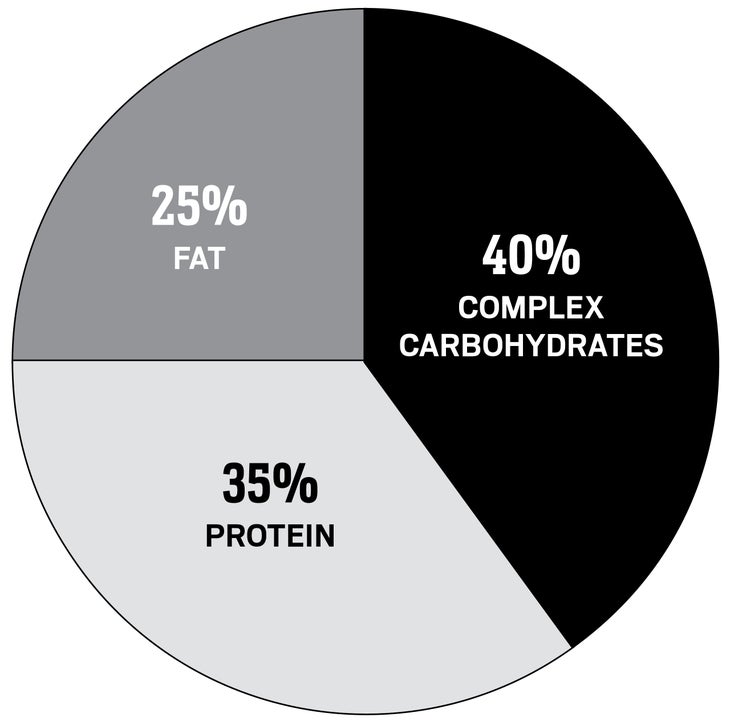

Step 2: Ratios of Carbohydrates, Proteins, and Fats

Knowing the different roles that carbohydrates, protein, and fat play allows climbers to customize food to our specific needs. In a primarily strength-focused sport like climbing, higher-protein and lower-carb food choices work best for rest days or light climbing days, since you’ll need more mechanics on duty to repair muscles after exercise and less immediate energy. As your intensity level increases, so will your carbohydrate requirement.

The ratio in the pie chart above assumes you’re taking in enough calories for your weight and activity level. To figure out how much you should be eating, try this test: After dinner, wait 15 to 20 minutes before going back for seconds to give your brain time to catch up with your stomach. If you’re still hungry after the wait time, proceed; if not, then you’ve eaten enough. If you can go four to five hours before getting hungry, then you’re getting enough calories. If you get hungry before then, ask yourself:

- Was there too much or too little protein, carbohydrates, or fat?

- Did I eat enough?

Ratio for a rest day:

Step 3: Combining Ratios and Timing Across Disciplines

Timing and food ratios allow climbers to fine-tune and manipulate food for optimal performance. If carbs are the gas, protein is the mechanic, and fat is the pedals, timing is how you upgrade your mini-van to a sports car.

For any climbing day, start off with a meal that includes 40 percent complex carbs, 35 percent protein, and 25 percent fat. Then, within 45 minutes after you finish climbing for the day, eat a snack or meal with the ratio of 30 percent simple carbohydrates, 60 percent protein, and 10 percent fat. This ratio will change based on the type and intensity of your climbing. Below, we’ve given ratios and sample meals and snacks for each climbing discipline. (Note: As you climb, right before or after a pitch or problem is the perfect time for unrefined simple carbohydrates. When exercising, your body can take in more fuel and use those quick-acting simple carbs for a power boost. They are also a good way to quickly refill your glycogen stores post-climbing, which aids with recovery.)

For a half day of bouldering

If you need fuel to send, have a snack that is 50 percent simple carbs, 30 percent protein, and 20 percent fat. After climbing, stop for a recovery lunch that is 30 percent simple carbs, 60 percent protein, and 10 percent fat. Drink water to stay hydrated all day long.

- Breakfast: Five-grain porridge with butter, sea salt, and hardboiled eggs

- Snack: Banana with peanut butter

- Lunch: Lettuce-wrapped burger with sweet potato fries

For a day of sport climbing

To help clip the chains, have a snack that is 60 percent simple carbs, 25 percent protein, and 15 percent fat. When you’re done climbing, stop for a recovery meal that is 40 percent simple carbs, 50 percent protein, and 10 percent fat. Drink water to stay hydrated all day long.

- Breakfast: Smoked salmon and goat cheese frittata with tomatoes, onions, and green lentils

- Snack/lunch: Apple slices wrapped in prosciutto

- Dinner: Rotisserie chicken with mashed potatoes and broccoli

For a long day of trad or alpine/ice climbing

Start your day with a bigger meal that incorporates the normal ratios. As you climb, have small, easy-to-digest snacks that are 70 percent simple carbs, 20 percent protein, and 10 percent fat. When you’ve returned to the car, stop for a recovery meal that is 60 percent simple carbs, 30 percent protein, and 10 percent fat. Drink a homemade electrolyte beverage to stay hydrated all day long.

- Breakfast: Quinoa bowl with scrambled eggs, black beans, bacon, and avocado

- Snacks: Oatmeal and fruit-squeeze pouches, dates and almonds, or sweet potato chips with almond-butter pouch

- Dinner: Beef stew with potatoes, carrots, and celery

Read More: When should You Use a Sport’s Drink

The goal of strategic eating is to make climbing nutrition actionable so that you can focus on the real goal, which is getting the most enjoyment out of doing what you love. So eat balanced meals, incorporate ratios, and time your simple carbs around exercise. If you feel great, you’ll climb better on a more consistent basis and can recover quickly, which means more pitches, problems, and sends.

Julia Delves is the founder of Trailside Kitchen and developer of the Trailside Method, a 4-week program of strategic eating for active outdoor lifestyles. Learn more at trailsidekitchen.com.

The post Eat Right, Feel Better, Send Harder. It’s That Simple, Right? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>