The fine art of sending your dream routes without really trying.

The post Topropers Unite! How to Convince Others to Haul You Up appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

I suck. After 25 years of climbing, I have elevated passionate mediocrity to an art form. I have never even considered climbing the Nose, never led a pitch of ice, and barely pierced the ceiling of 5.12a sport routes. I boulder like a wounded walrus. There is no real excuse for being this terrible. During the past quarter-century, climbing has been an important part of my life. I have climbed as part of my job teaching at a boarding school for much of that time and my wife gives me ample hall passes. My scarecrow-like physique favors climbing; there have been few serious injuries in my life, and no detours to locales with no rock. Still, I’m just not that good.

I have charged through 25 years with unwavering enthusiasm and the misguided belief that enough daydreaming and obsessive guidebook-reading in the bathroom would improve my climbing. My hopes of breaking into the inner circle of climbing bro-dom remained unrealized. Yearly I watched climbers with a fraction of my experience climb harder, longer, tougher routes. A student I had taught to climb fired a 5.13d. Another student climbed the Nose on El Cap and the Supercanaleta on Fitz Roy. It was time to stop talkin’ and start chalkin’. The problem was getting up a résumé route without risking my neck.

I worked all my usual tricks for a select classic in Rocky Mountain National Park: stronger partner, sequencing to land the easy pitches, plenty of excuses ready if I failed. However, karma caught up with me. We were three pitches up Spearhead when my lead petered out in a smooth slab with TCUs behind crispy flakes for pro. I noodled up and down searching for a way out. This was the moment when gravity met ego. The problem was that I had taught my partner to climb. Even though he now climbed grades harder than I, I had hoped to retain some of the old master aura. But every time the crystals crumbled under my feet the coward in me counseled retreat. I finally threw in a belay at the end of the crack. As my partner approached I tossed down the words of contrition that generally mark the end of a climbing partnership: “I don’t think I can lead the next pitch. It’s all you.”

At the moment of shame, as I handed off the rack, the unexpected happened. Instead of heaping scorn upon me, my partner smiled.

“It’s all good,” he said. “You’ve got a family, I’ll take this one.” Then he glided across some of the hardest runout climbing I’ve ever seen. That simple exchange shook me out of my self-pity and offered redemption. Getting a tow up the hard pitches was not sleazy; it was a proud act of cunning that required years of experience. It was time to embrace the idea that I was happier on toprope.

I also realized that I was not alone. Rather than being a useless poser, I was actually a member of a unique subset of the climbing community. Now it was time to spread the gospel and say, “Topropers Unite!” (TRU for short.)

“What the hell is so great about toproping?” you ask. After all, almost every one of us initially began climbing on toprope. You can, however, elevate the toproping game to the point where you achieve goals as well as TRU climbing status. The key is stealth. It’s critical to fool other climbers into thinking that you really are a “true” climber, not just a leech. Avoid clanking hexes, long underwear topped with shorts, and tube socks tucked into Fires. Most of my best routes have been done with climbers of far superior abilities, hauling my skinny butt up real routes that I could then namedrop.

My inspiration comes from a few of the patron saints of the TRU crew. The first is Edward Whymper, who achieved lasting fame getting hauled up the Matterhorn by guides who climbed circles around his tweediness. However, his accomplishment was marred by having to pay those guides. The real hero has to be Chongo, who scammed rides up numerous El Cap routes, “hitchhiking” his way to the top. I don’t have the scratch to hire a guide to haul me up climbs I could brag about. I also lack the cajones to live in the dirt and trade canned food for the right to jug fixed lines like Chongo. I am left to rely on wits, flattery and guile.

I present a few tips so that you, too, may get up the climbs of your dreams without too much heavy lifting.

1. RATIO

The key to attaining TRU status is to climb a lot, while also avoiding the dreaded sharp end as much as possible. Lounging in the gym with autobelays is not going to cut it. Get out to the crags and tie in. Just find a way to get on stacks of routes without leading. When really pressed, you must be prepared to lead to avoid sinking to boot-licking subman-ship. Aim for a camouflaging ratio of one route led for every four routes on toprope.

2. MRG

The best possible way to crank out a ton of routes without too much leading is finding a Magnanimous Rope Gun (MRG). The MRG is large-hearted, stoked to climb, and leading about three number grades harder than you. Generally the MRG is so psyched to climb that he or she won’t even notice that you aren’t leading any of the pitches. Alternatively these people may be so kind that they just charge along without pointing out that you haven’t led anything all day. They may even hand you creampuff pitches on worthy routes to keep your self-respect intact. MRGs are hard to find since they tend to be ideal partners for “true” climbers also. If you can’t find an MRG you may resort to a few of the following techniques.

3. THE STALL

Needed for when you are climbing with someone who has mistaken you for a “true” climber and expects you to lead half the pitches. This technique involves taking so long to shoe up at the sport crag that your partner can’t avoid being ready to go first. As you glance up from tightening your laces for the 11th time you note with some surprise that your partner has stacked the rope, racked the draws, tied in and is snorting with impatience at the bottom of the route. “You look ready,” you say mildly. “Why don’t you lead this one?” Your partner shoots away and your first toprope of the day is secure. Now you need to keep the momentum. You need sequencing.

4. THE SEQUENCE

This does not refer to remembering the mind-numbing beta that better climbers recite all day. No, this refers to finessing the flow of the climbing day. Now that your partner has led the first route, you are descending “tired” from the TR lap. Shake your forearms vigorously and mumble, “Nice lead. My forearms are blown right now. Why don’t you start the next one while I rest?” With any luck this sequence can get you through four or five routes before your partner really is blown from doing all the real climbing. When you hit the end of the line and your partner calls your bluff you need …

5. LOCAL KNOWLEDGE

Even if you aren’t really a local, having the goods from all those hours spent poring over the guidebook will pay dividends here. Casually mention the “classic” 5.8 just around the corner that you could lead. The key is to fire up something easily with a minimum of risk. When you’re finished your partner will probably want to get on something harder. Here the tried-and-true line, “Since I picked the last route, why don’t you lead this one?” often works. If your partner is insistent that you do your share on the sharp end, resort to point 6.

6. EXCUSES

You don’t need the overworked “hung-over” or “too reachy” or “tweaked finger/ jacked shoulder” type of excuses. These are so transparent any self-respecting “true” climber would know you were a total weenie dodging your duty. No, you need the bulletproof excuse, something like, “My kids were up all night vomiting with the flu.” The best excuses not only slip you off the hook, but elicit sympathy from your partner and any nearby onlookers. “Wow, you looked pretty good on that considering you didn’t get any sleep.” When you run out of excuses you may have to actually climb. If this happens, by all means step up and maintain your dignity and cover.

After all these years of walking the line between revealing my TRU gumby status and remaining included by “actual” climbers I have decided to come out of the shadows, though I suggest other TRU climbers keep a low profile to scam rides on the rock. Now if I could just get them to post a website with a TRU scorecard I could finally be a leader in something.

The post Topropers Unite! How to Convince Others to Haul You Up appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

They figured they knew enough about climbing to wing it, but took a dangerous risk that could have cost them.

The post They Climbed On a Home Depot Rope—Thought A Real Rope Was Too Expensive appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

During my senior year of high school, my friends and I were bored. We decided we collectively knew enough about climbing for it to be safe. We went to the local outfitter and bought harnesses, carabiners, and belay devices, but we scoffed at the price of a rope. It was way outside our budget. Instead, we went to Home Depot and bought 100 feet of poly cord that was rated for 200 pounds. We climbed on that rope all day, just easy 5.3 climbing on toprope. I’ve included a couple photos. It wasn’t until I was lowering at the end of the day that I realized what a mistake I’d made. The 100-foot rope had stretched to about 200 feet, shrinking to the size of 8mm cord. I bought a real climbing rope the following week. Wanted to share because we are all new at some point and even with the best intentions mistakes are made. We should collectively work together to improve safety across the sport. I wish someone would have stopped us from climbing on that poly rope.

—Kyle Harris, via email

—

—

LESSON: Modern climbing ropes include a number of climber-friendly features. They can hold thousands of pounds of force. They have durable sheaths that prevent abrasion and cutting. They have the ideal amount of stretch to catch a fall softly, and then bounce back to their original length and diameter. They’re supple and easy to tie and untie. They’re tested to meet rigorous safety standards. And they work great with modern belay devices. A random hardware store rope is not designed with any of these goals in mind, and can’t be expected to meet them. Always use proper climbing gear designed and rated for climbing.

Want more? Check out more installments in our ever-growing hall of shame:

Lucky He Didn’t Die. Lowered From a Toy Carabiner

Unfortunate Groundfall, Fortunate Landing

Leader Decks When Experienced Climber Bungles the Belay

Saw Through Someone Else’s Rope

Belayed With Hands Only—No Device!

Smoke Brick Weed and Go Climbing

Belay With a Knife In Your Hand

Don’t Let a Clueless Dad Take a Kid Climbing

The post They Climbed On a Home Depot Rope—Thought A Real Rope Was Too Expensive appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Parents love their kids and will do anything for them, including taking them toprope climbing when they don't have a clue.

The post For Safety’s Sake Don’t Do This: Let Parents Belay Through A Bolt Hanger appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

The Incident

I was climbing at Clear Creek Canyon, Colorado. After our first route, we moved to another next to a family that was toprope climbing. My partner pointed out that they were toproping off a single bolt in the middle of the route. We quietly shared a grimace. When I was halfway up our route, I noticed that their toprope was actually running directly through the bolt hanger with no other gear. One of their pre-teen kids was climbing the route.—Will, via email

The Lesson

There are two major issues here. First, bolt hangers are not designed for the rope to run directly through them. Some companies do make big, fat, rounded hangers that you can lower or rappel through, such as the Metolius rap hanger, but these would only be found at the top of a route. The angular metal edges of a typical hanger will not be friendly to your rope as it grates and stretches across them. The amount of wear from a group climbing up, lowering down, and taking toprope falls over and over will surely knock months off the life of your rope at best.

Furthermore, bolts can and do break sometimes, so you should not depend on just one. Notably, a climber died while rope soloing a route last year because he was only attached to one bolt and it failed. Bolts are very strong, but sometimes things do go wrong, which is why it’s important for anchors to be redundant. Just climb to the top of the route and build a redundant anchor on two bolts. This is sport route, after all. Sport climbing is an entire discipline that was designed to make things less sketchy. And toproping should be even less sketchy than that. I shudder to think of how this person even went about threading a rope through a bolt hanger mid-route. I hope the climber was standing on a massive ledge.

Also Read

- Weekend Whipper: Ice Climber Decks In Spite of Dad’s Advice

- When a Climber Dies on K2 is Anyone to Blame?

- Remembering Tom Hornbein, Visionary Everest Pioneer

The post For Safety’s Sake Don’t Do This: Let Parents Belay Through A Bolt Hanger appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Learning how to try hard is hard. And it’s so easy to be stupid.

The post Having a Project Made Me a “Dumb” Climber appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Part I. The Big Easy

I have a general hatred for trying hard. This will come as a surprise to those who climb with me—my belayers often stare at their feet in embarrassment while I thrutch and scream up steep sport pitches and offwidths—but it’s true. Climbing hard hard is not for me.

I love that 80th-percentile of try-hard. A sequence that may feel out of reach on my first go, but after a few more tries (and usually within the same session) I have beta that works and I’ll redpoint the pitch before long. If a problem is actually difficult for me (like, multiple sessions to work out a single sequence, or multiple seasons to fire a single pitch) I am completely and utterly disinterested.

I’ve held this element of my climbing personality in high, cocky regard for years; I learned to climb on big, loose, and easy routes in the Canadian Rockies, where one’s ability to onsight with confidence is a far more important skill than one’s ability to suss out (and execute) nails-hard sequences. But, as is the case for many wannabe Rockies hardies, my love of living eventually outweighed my love of chossy faces, and I began seeking out more difficult climbs on solid stone. As a good friend of mine often says: “Life’s too short to climb on bad rock.”

So I swapped broken ridges for water-worn limestone canyons and granitic peaks, but I lacked the mental discipline to actually enjoy projecting. In fact, my redpoint and onsight grades, for both sport and trad, were often (and up until very recently) the exact same grade.

Part II. Having a Project

As a Climbing editor, I speak with professional climbers on a fairly regular basis. Boulderers, bolt-clippers, alpinists, you name it. Each of them has a level of climbing fitness and skill that I will never even half-heartedly try to achieve. I will, however, ask for (and then at least try to implement) any and all climbing advice that Carlo Traversi or Sébastien Berthe can give me.

Talking to the world’s best climbers about their career-highlight ascents is, as you can imagine, pretty damn inspiring. And I soon began to wonder where my own physical limit lay. Or at least how hard I could onsight in the alpine. (I’ve bumped up three letter grades since starting this job a year ago.) It would appear, now, that I like to try hard. Like hard hard. (I tried an overhanging friction corner three times this summer and I still don’t know how to do the crux move!) Which brings me to the point of this spray-a-thon. Projecting. How to do it, how to think about it, and how not to do it (i.e. how I did it).

Recently, I threw a toprope down a technical and thin trad pitch that connects seams with shallow cracks and runout face-climbing scoops. It’s a cult classic, and a pretty safe one at that, but the gear is a bit tricky and the line’s reputation for big whippers and broken heels is justified. I dropped the rope, plugged a few directionals for the traverses, and began toproping the pitch. The off-vertical granite felt tenuous and insecure, but not all that pumpy, and I basked in the toprope illusion of security. I sagged onto the rope near the top, at the redpoint crux, a shallow corner with no immediately apparent holds or gear. I pawed at the nine-inch-wide open book, moving my hips like a pathetic Bachata dancer, trying to finesse a sequence.

This crux feature was brief, with a chalk-splattered knob just out of reach above, but I realized the last obvious crack was over a body length below me. That would be quite the ride, I shuddered. I wanted security, and I wasn’t about to find it on a greasy sloper rail in July. I swung around out left and found a series of diagonal micro edges—half-pad laybacking with crystals for feet—and I did the crux (barely) on my first try. I climbed to the top, lowered, and (barely) made it through the crux a second time. Huh. I guess that’s my beta. My partner, Emilie, was dealing with a bad cough—we’d been living out of a leaky pickup truck for the previous five weeks and our lungs were attacked by the thick accumulation of black mold beneath our bed—and she declined to try the pitch. “You look good from down here!” she wheezed.

I returned with Emilie the next week and tossed the toprope down again. This time it was wet, but, somehow, I stuck the layback crimpers once again. I ran another TR lap while placing gear, which was terrifying, because I could see just how far away my last finger-sized cam was, some meters below me while I squeaked through the crux.

You need to lead this, the toxically proud part of me warned. Carlo Traversi wouldn’t toprope this much.

Part III. Finishing a Project

Two weeks later I was about to leave town and I hadn’t given this pitch a lead attempt. I recruited Nat, a mutant friend of mine who’d climbed this pitch as his first of the grade, to give me a catch. I allowed myself one more toprope lap, to practice placing the RPs on the low crux, before tying in sharp.

“Dude, what are you doing?” Nat laughed, as he watched me quest to the left, to my tiny layback crimps, at the redpoint crux.

“What? This is my beta. I’ve done it this way, like, three times.”

“Why don’t you stay on the route? Just reach past that corner and grab the juggy knob. … And there’s two gear placements in the seam at your chest—that’ll shorten your whip.”

This was a lot to take in. I shuffled back to the right, squarely below that damn corner, hiked my feet up, and, sure enough, deadpointed to the knob with minimal grunting. Then I peered into the seam and, sure enough, two excellent placements stared back. I lowered, cleaned my gear, and pulled the rope.

Twenty minutes later, I hiked the pitch. I was never fearfully runout and I giggled (loudly) at the chains. Sometimes the hardest part of trying hard is not trying too hard.

Part IV. What did I Learn?

In the days since this mini project, I’ve talked to my co-workers, friends, and pros about my beta-finding ineptitude. I was prepared for a well-deserved ribbing, but empathy largely prevailed. As it turns out, it’s easy to be dumb while projecting. Here are my takeaways:

Climb with people who are stronger than you.

Having never climbed on the route with anyone before, it hadn’t occurred to me to try different (read: more powerful) beta. I wanted slow, controlled movements—that’s why I chose the thin-but-plentiful crimps out left—instead of a single explosive lurch. But Nat, being much stronger than I, didn’t find this deadpoint to be all that cruxy, and, though I didn’t have the self belief to figure this beta out for myself, as soon as Nat recommended it to me I realized it was a perfectly fine option. (Note: climb with strong people who, ideally, are roughly the same height as you.)

Climb with people who are weaker than you.

Another way-stronger friend of mine, Nolan, invited me to his project and then promptly stole my beta. Previously, he’d been taking my first piece of advice, climbing with people far stronger than him, and trying to emulate their beta, but what he found is that 5.14 rock climbers can use 5.13 beta to climb 5.12. I, on the other hand, need every ounce of that 5.12 beta to send 5.12—and by taking me there, Nolan got to watch me develop the physically easiest beta—a sequence full of weak-man intermediates and foot trickery that Nolan realized was the most user-friendly solution.

Play to your strengths but be willing to confront your weaknesses.

Had I been willing to think critically about my beta, I would have realized that the style that suited me was not the easiest way. And, had I asked literally anyone for beta, I would have learned that “no one goes out left.” Most of the time, the go-to beta is the go-to beta for a reason: it’s the easiest way. Don’t refuse to try it just because it’s outside your style. But also be looking for ways to tweak beta so that you’re playing to your strengths. For me that means finding ways to make big moves slightly less big without closing myself off to anything that isn’t static.

Buy your belayer a pizza, since beta-finding takes time.

While I moan here about not climbing with anyone on this route—that my belayer literally just hiked up there to support me while she hacked up a lung—I will clarify: belaying projects is far more work and far less interesting than your typical cragging belay, and those willing to support you should be showered in gold. Or beer. Or pizza.

Don’t define what is “hard” for you.

This aha! moment would have never happened if I hadn’t planned to “try hard” from the beginning. But, since I decided I was finally going to “have a project,” I made the route harder to send because I went into the process with that expectation. It turned out to be fairly easy for me, unfortunately, and my friends are asking when I’ll actually get on something hard hard.

Anthony Walsh is a digital editor at Climbing. He looks forward to not trying too hard in the mountains this summer.

The post Having a Project Made Me a “Dumb” Climber appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Get the safest method and helpful tips for giving the best toprope belay, whether you're using an ATC or a grigri.

The post How to Toprope Belay appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

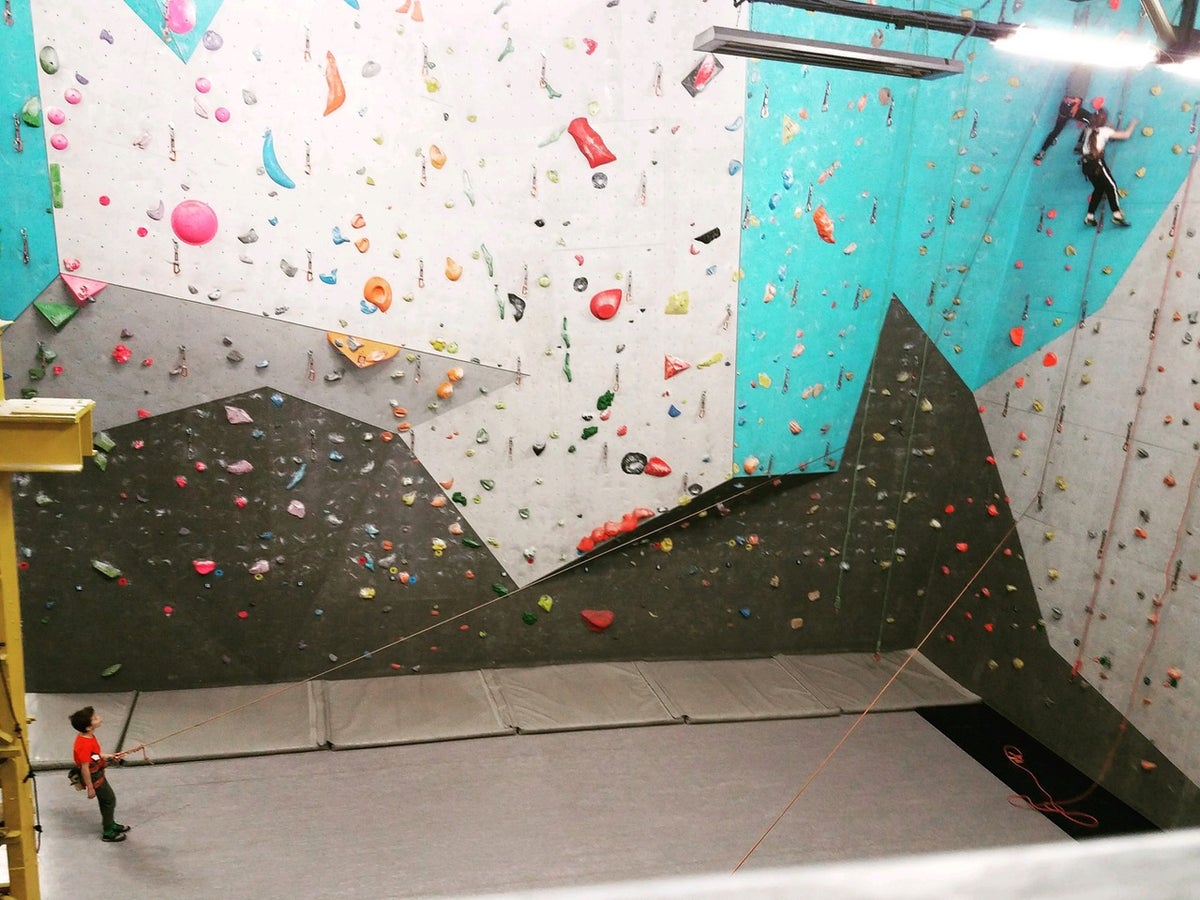

Belaying a climber on toprope—where the rope runs from the belay device up through an anchor at the top of the climb and back down to the climber’s harness—is as straightforward as it gets. The climber doesn’t have to clip bolts or place gear as they move up the wall. With the rope secured overhead, any falls are usually short and safe, as long as you have an attentive belayer. If you’re a newer climber, learning how to give a safe and proper toprope belay will also make you a much more desirable climbing partner.

Here are some tips and the best method for giving a good toprope belay, whether you’re using a tube device like an ATC or a brake-assisted belay device like the grigri.

Universal Belay Advice: Pay Attention

This is the most important part of any type of belaying. You must be aware of where your climber is and what they are doing at all times. It can be challenging to ignore the many distractions of a climbing gym or crowded crag—music, other climbers, conversations—but paying attention is absolutely vital to being a good belayer. Watch your climber closely when they’re on the wall and communicate clearly and effectively when necessary.

Load and Lock: Putting a Climber on Belay

With a tube-style belay device (e.g., ATC or Reverso), thread a bight of the rope through either slot in the device. (Some devices have grooves on one side that make braking easier, so ensure the brake strand is coming out on that side.) For a brake-assisted device like a grigri, thread the bight of rope through the groove, ensuring the correct end leads up to the climber. For either device, clip a locking carabiner through the rope and device, then through the belay loop on your harness. Lock the carabiner.

With toprope belaying, the part of the rope that goes up to the anchor is the climber’s end. The other part coming out of the device is called the brake strand. Orient your belay device correctly so that the brake strand comes out away from your harness or to the same side as your brake hand (typically your dominant hand).

Double-Check Your System

You and your partner should visually inspect each other’s knots and belay setup before starting a climb. Make sure both harnesses are worn correctly with all appropriate buckles doubled-back. The belayer should make sure the climber’s knot is threaded through both tie-in points, tied correctly, and dressed properly (no crossed strands).

The climber should make sure the belayer’s device is set up properly: The rope is threaded through everything, and the carabiner is locked. Test the system by pulling on both strands of rope coming out of the belay device. If it pulls the belayer via the harness belay loop, you’re good to go.

Do this double-check every single time either person is about to climb, meaning you might go through this process a few dozen times in one climbing session. These double-checks are vital for preventing mistakes.

[Also Read: Common Belay Screw-ups and What To Do About Them]

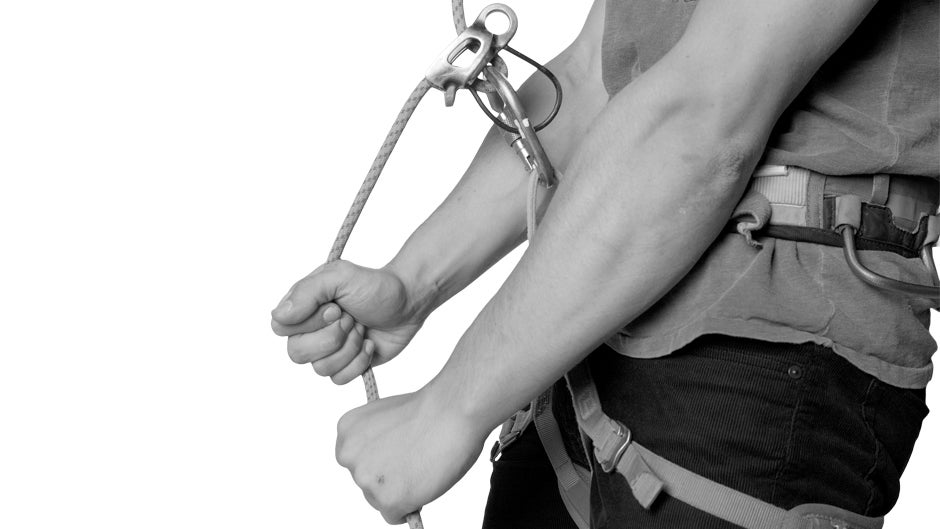

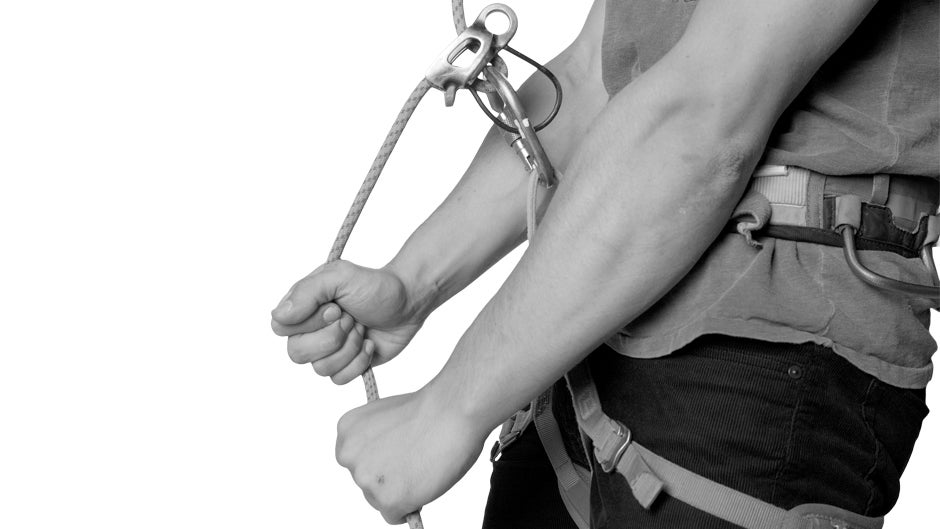

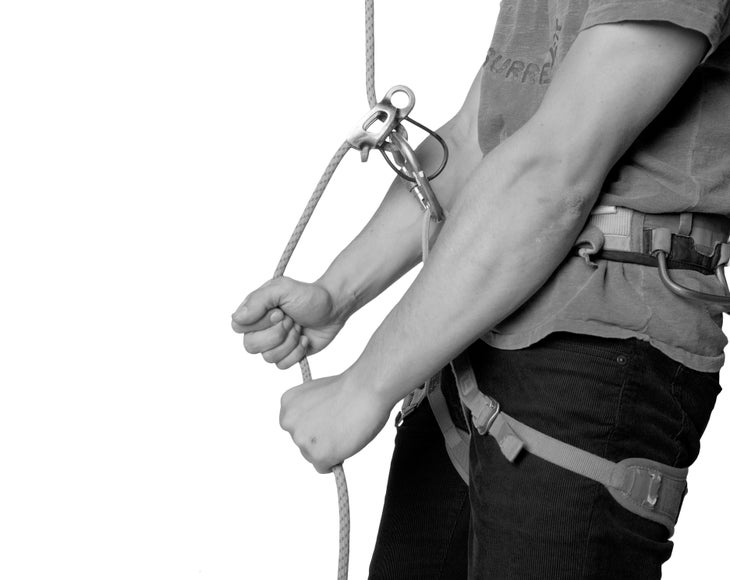

Toprope Belay Method: PBUS

Pull, Brake, Under, Slide

A universal rule for belaying is that your brake hand, which is palm down on the brake strand of the rope, should never come off the rope. The PBUS method—which stands for pull, brake, under, slide—is a tried and true technique that will ensure your hand never leaves the brake strand, while providing a safe belay.

1. Pull: Pull down on the climber’s rope with your guide hand—which is the hand on the climber’s end of the rope, and usually your non-dominant hand—to remove slack as the climber moves up. At the same time, pull out with the brake hand to get the slack through the belay device.

2. Brake: Put the brake strand in the brake position, which is down in front of you. This puts a bend in the rope at the belay device that will keep the rope from moving through it.

3. Under: Take your guide hand off the climber’s strand and place it on the brake strand under your brake hand, meaning it’s lower on the rope.

4. Slide: With your guide hand now tightly grasping the brake strand, slide your brake hand up the brake strand (without removing it from the rope) so it’s a few inches away from the belay device. Then put your guide hand back up on the climber’s strand.

Repeat

You’ll keep doing this PBUS motion each time the climber moves up and creates slack in the rope. Once you do it a few times, it will become muscle memory and you should be able to do it without thinking.

Take and Brake

When the climber reaches the top, falls, or needs to sit on the rope to rest, take in all the slack and put the rope into a solid braking position. Pull the brake strand down in front of you. Use two hands on the brake strand if the climber wants to hang for a while, or consider wrapping the brake strand around your hip and slightly under your bum with only your brake hand on it. The friction and weight from your body will help reduce the force needed from your hand to hold the rope in place.

[Also Read: Why Dynamic Belays Can Matter]

Lowering a Climber

When your partner is ready to come down, take in as much slack through the belay device as possible and put the rope in a brake position down and in front of you. Wait until the climber is comfortably weighting the harness and the rope.

For a tube-style device, put both hands on the brake strand and slightly raise the strand to lessen the angle between it and the device. Use the top hand to feed rope through the device while the bottom hand controls the speed. For a brake assisted-device, carefully pull the lever up slightly to allow rope to feed through the device, keeping your brake hand on the brake strand at all times. Keep the lever only partially raised and use your brake hand to control the speed at which you lower the climber.

Be very careful to stay in control. If at any time the climber is moving down too fast, immediately move the rope down away from the device into a strong braking position. If you’re using a brake-assisted device, close or depress the lever to slow the lowering rate.

More Toprope Belay Tips

- Little movements are better than big ones. Instead of waiting to take a bunch of slack in at once, constantly take in any slack in the line. This will make any potential fall much smaller.

- When the climber first starts off the ground or when they are right above a big ledge, keep the belay tight so that a fall and the resulting rope stretch won’t result in them hitting the ground or ledge.

- When first learning to belay, it’s crucial to use a backup belayer, or someone who is also holding the brake strand in case you don’t catch a fall. Not only can a backup belayer provide important pointers as you’re belaying, but they also provide a third person to double-check everyone’s belay and tie-in setups.

- Always have a certified instructor or experienced climber show you this technique and watch you practice it before doing it on your own.

The post How to Toprope Belay appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Use a long cordelette or sling to create a fast, safe, and self-equalizing quad anchor

The post How to Build a Quad Anchor appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

The quadalette, aka the quad anchor offers a strong, fast, redundant, and simple anchor. It’s great for when distributing forces between pieces is a high priority. Note that the quad will extend slightly should either side fail. That makes it best suited for routes with modern, two-bolt belays and/or ice routes when using two screws at a stance. The quad also works well on multi-piece gear anchors, though it requires more consideration.

How to Build Your Quad

Building a quad requires either a cordelette at least 14 feet in length (6mm nylon minimum or 5.5mm tech cord), a quadruple-length sling (240cm), or two 120cm slings. You can easily store this system on your harness. Here’s how to tie it:

- Unfurl your sling or cordelette into one giant loop and double it into a smaller, two-stranded loop.

- Tie an overhand knot 4–7 inches from each end. Now you have a two-stranded loop at either end, with four strands of material between the overhand knots.

- You can leave your quad rigged for a long day out. Unlike the cordelette, it doesn’t require re-tying at each stance.

Pro climber and guide Genevive Walker demonstrates how to build a quad anchor

Setting up Your Quad Anchor

- Clip a carabiner into each end-loop and clip each of those into a bolt or a screw.

If you’re belaying a second up from the quad anchor:

- Clip a locker into two of the four strands between the overhands. You clip into two strands in the middle to effectively “trap” the locker between the overhands. Never clip all four strands—a failure in one bolt/screw would result in the anchor carabiner sliding off the quad. Then clove-hitch yourself into the locker.

- Rig your belay device on the two free strands.

If you’re setting up a top-rope anchor:

- Clip a locker into two of the four strands between the overhands, and another locker into the other two strands. As stated above, never clip all four strands—a failure in one bolt/screw would result in the anchor carabiner sliding off the quad.

- Feed the rope through the two lockers, then tie yourself in and lower or rap down.

Note: While two strands offer ample strength for both climbers at the belay, clipping each climber into their own two strands lets one climber hang on the anchor without pulling on their partner.

Equalizing a Quad Anchor

The quad’s equalization/distribution comes in handy when the anchor relies on two pieces of equivalent strength—it distributes the load equally between the pieces.

The quad has a wide range of self-equalization between the two overhand knots. It accounts for changes in the direction of forces at a belay. If using two pieces whose strength is difficult to assess—older bolts, screws in sub-par ice, etc.—move the overhand knots closer together to reduce extension and the range over which the quad distributes forces (or self-equalizes).

Three-Point Quads

At certain stances, a three-point quad anchor makes sense. Here’s how to rig it:

- Unfurl your cord/sling and double it, without yet tying the overhand knots. Then clip each two-stranded loop into your two smallest/weakest pieces.

- Pull the sling down to tension it and tie an overhand below the two pieces; they are now equalized, with two strands hanging between the pieces.

- Pull this two-stranded bight down and tie a second overhand in it. Then clip it into your largest/strongest piece—you now have a quad between two small, equalized pieces and one large, bomber piece.

The post How to Build a Quad Anchor appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Toproping is the safest way to climb—and often the most fun. If leading a testy route is the pinnacle of mind-and-body focus, toproping is surely the pinnacle of pure recreation; a chance to relax and enjoy climbing solely for the movement, without the nagging tension of an ever-present lead fall. Assuming your toprope anchor doesn’t fail. The day … Continued

The post Toproping Might Not Be as Safe as You Think It Is appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Toproping is the safest way to climb—and often the most fun. If leading a testy route is the pinnacle of mind-and-body focus, toproping is surely the pinnacle of pure recreation; a chance to relax and enjoy climbing solely for the movement, without the nagging tension of an ever-present lead fall. Assuming your toprope anchor doesn’t fail.

The day I witnessed an anchor pull, I was in Ouray, Colorado. Three years ago, mid-winter. My partner had led a mixed route and clipped into a small tree overhanging the edge of the cliff. Black webbing noosed around the narrow trunk revealed that it had been used before for an anchor. My partner clipped it, and yelled “Take!”

“Don’t you want to back that up?” I shouted.

“It’s fine,” he said. “Lower me.”

I had lowered him less than five feet when the tree pulled, sending him hurtling earthward. He was saved only because he hadn’t yet cleaned his top piece, a piton hammered in a horizontal crack.

Toprope anchors don’t often fail. In fact, they should never fail. And when they do, pilot error is usually to blame—the homemade bolt hanger broke, the single tree pulled out, the slung block cut loose. In most cases, climbers simply fail to understand the loads that toproping can generate. Logic tells us that toprope forces equal at least our bodyweight and then some, but beyond that, it’s anybody’s guess—until now. For this article, we wanted to determine the loads that toprope falls place on anchors—with both a taut rope and a “lazy belay” scenario with several feet of slack in the system.

The fall tests were conducted on a pulley-style toprope, i.e., one where the belayer stands on the ground and the rope runs up through the top anchor and back down to the climber. The lessons learned, however, can apply to any type of toproping or following situation.

The Fall Scenario

To determine how a lazy belay affects the loads on an anchor, we staged two series of test falls and measured the maximum impact forces. In the first series, a 200-pound climber fell near the anchors of a taut pulley-style toprope. In the second series, using the same pulley-style setup, the same climber fell with four feet of slack in the rope—a common scenario if the belayer’s attention has lapsed for a moment. For consistency, both tests were performed with 35.5 feet of rope between the climber and the belayer, and the belay was virtually static. (We used a belay device clipped directly to a belay bolt—certainly not a recommended use of the device nor a good belay style because it doesn’t allow for dynamic load absorption, but one that allowed us to remove most of the variables from the belay setup.)

The Results

First Series: A standard pulley-style toprope fall with virtually no slack in the rope.

—The details: 200-pound climber, static belay, 35.5 feet of rope in the system. Forces were measured at the toprope anchor.

—Fall 1: 800 pounds load on the anchor.

—Fall 2: 750 pounds load.

—Fall 3: 700 pounds load.

Second Series (the lazy belay): Same details as the first series, but with four feet of slack.

—Fall 1: 1,300 pounds load on the anchor.

—Fall 2: 1,550 pounds load.

—Fall 3: 1,500 pounds load.

Lessons Learned

The dramatic increase in forces generated by only four feet of slack should serve as a wake-up call to all us lazy belayers. You know how it happens: As your partner works his way slowly up the warm-up route, you stare at your feet, kicking dust and thinking about what’s for lunch. “TAKE!” breaks your daydream—a big U of slack hangs at your waist.

The good news is that a little bit of slack won’t come close to testing the holding power of your gear if you’re using a safe anchor, which will have several thousand pounds of holding power to spare. But the fact that four feet of slack essentially doubles the toprope impact forces should reinforce the need to build totally bombproof anchors. Suddenly, slinging that gnarled juniper tree, or clipping two TCUs and yelling “Off belay!” seems questionable. Would the anchor hold a harsh toprope fall?

The lesson: Even when toproping, build your anchor to be 100-percent failsafe.

Why a Pulley-Style Toprope Increases the Forces

There are two ways to toprope. One is to belay from the top of the route or pitch, and belay your partner directly up; the other is to belay pulley- or “slingshot” style from the ground, with the rope running in an inverted V up to the anchor and back down to the climber. This is the most popular style of toproping because both partners can base from the ground, and you can easily communicate with one another.

What you should know, however, is that this method dramatically increases the forces on the anchor. The pulley-style toprope loads the anchor with not just the climber’s weight, but also the counterweight of the belayer (that’s why you feel an upward tug when holding your partner’s fall, and sometimes get pulled into the air). In a frictionless world, a climber hanging on the rope would load the anchor with twice his weight. But because of friction, rope stretch and other real-world variables, the load on the anchor is lower—more often roughly 1.6 times the climber’s weight.

Belaying directly from the top of the pitch, either with the belay device clipped to the anchor or to the belayer, eliminates the pulley effect. In this situation, the second loads the anchor with just his body weight—assuming that the rope is kept snug. The disadvantages of belaying from the top are as you likely imagined: You might not be able to see or hear the climber and your belay position is likely awkward, either on a ledge or stance or in the branches of a tree, or, due to the anchor configuration, you belay directly off your harness so you have to hold the full weight of the climber should she/he fall. A slingshot belay from the ground eliminates all these issues, which explains why it is the go-to technique for nearly everyone—just make sure your anchor could hold a truck.

The post Toproping Might Not Be as Safe as You Think It Is appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

See something unbelayvable? Email unbelayvable@climbing.com and your story could be featured in an upcoming edition of the column. For more Unbelayvable, check out the Unbelayvable Archives. I was in Russia recently and noticed a toprope belayer standing on the other side of the room from his climber. Startled, I looked more closely and realized he … Continued

The post Unbelayvable: The Strolling Belay appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

See something unbelayvable? Email unbelayvable@climbing.com and your story could be featured in an upcoming edition of the column. For more Unbelayvable, check out the Unbelayvable Archives.

I was in Russia recently and noticed a toprope belayer standing on the other side of the room from his climber. Startled, I looked more closely and realized he wasn’t using a belay device at all—he had a figure-eight on a bight clipped to his harness, and he was supporting his partner’s weight by walking backward. I didn’t become alarmed until the after-work crowd trickled in and I saw dozens of people belaying like this, criss-crossing the gym as they backed up from one wall to the other. I don’t speak Russian and didn’t want to come off as bigoted about cultural differences, so I didn’t say anything.

—Ron P., via email

Lesson:

I mean, why overcomplicate things, amiright?

Kidding aside, I was equally baffled upon hearing this story, so I did some research. From speaking with some Russian gym personnel, it sounds like this is a common and condoned practice, at least in some facilities. According to one manager of a St. Petersburg gym, traditional belaying with a Grigri is preferred, but some of their coaches teach kids the walking belay method as an easier alternative, and international visitors often use it as well.

The technique looks untidy. It looks uncomfortable. It looks decidedly uncool. But it’s not necessarily unsafe, especially provided that the climber doesn’t weigh significantly more than the belayer. In the photo, you’ll notice that the kids have clipped the belayer’s end of the rope to the first quickdraw, introducing a sharp bend and therefore a significant amount of friction to the system. That friction increases as the belayer moves further back and the angle grows more severe. Usually, that’s plenty to stop the small-magnitude falls that toprope climbing generates.

Low margin of risk aside, this method does present some problems, especially in a crowded gym.

- Rather than relying on the camming action of an assisted-braking belay device or the multi-directional friction of a tube-style device, the climber in this setup pretty much just has that one bend—and the friction of the belayer’s feet against the carpet. Again, that’s usually plenty to prevent a ground fall. And it would definitely be plenty if everyone had on Velcro shoes (still waiting for that patent to come in). But most gym belayers sport either bare soles or rock shoes. Neither option has a particularly confidence-inspiring coefficient of friction on gym carpeting. So, if a heavy climber punts on a dyno and the belayer begins to stumble forward, that climber is going to drop quite a bit further than intended. Again, the risk of injury is low, but it’s not an optimal result.

- In this photo, the ropes aren’t double-wrapped around a bar at the top. Instead, they appear to be threaded through two draws as in a lead-climbing setup. Double-wrapping would add more friction, better defending the belayer from carpet-skidding into the wall in event of a dramatically botched crux. Double-wrapping also helps avoid the perils of speed-lowering.

- The bigger issue with this technique, of course, is the total chaos it causes on the gym floor. If the belayer and climber are on opposite sides of the room, it becomes impossible to traverse the gym without walking between the two. If the belayer gets pulled into the wall, they’re taking any innocent passersby with them. Plus, if two belayers cross ropes—well, you can just imagine. (The Ghostbusters have that slogan for a reason.) Finally, even if all your neighbors somehow prove sufficiently spatially aware to avoid entering your zone of hazard, walking blindly backward across a crowded gym is, in general, not a good idea.

In sum: For public safety reasons, use a belay device.

The post Unbelayvable: The Strolling Belay appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Have you ever noticed that lots of climbers don’t belay the same way as you do? Or that climbing instructors teach belaying one way, but then after class those same students belay differently? Where does all that variety come from? Is it safe? The AAC’s Universal Belay Program is designed to help every belayer find … Continued

The post AAC Universal Belay Standard: Toproping appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Have you ever noticed that lots of climbers don’t belay the same way as you do? Or that climbing instructors teach belaying one way, but then after class those same students belay differently? Where does all that variety come from? Is it safe? The AAC’s Universal Belay Program is designed to help every belayer find a common language and recognizable belay standard to ensure you get a safe catch. This episode takes you through the fundamentals of safe belaying and goes through the program’s toprope belay standards.

- Related: AAC Universal Belay Standard—Lead Belaying

- Related: AAC Universal Belay Standard—Details Matter

Coming Soon: Take the AAC Universal Belay Standard course at your local gym, club, school, or course provider. You will receive a Universal Belay Certificate that will give you and your partners knowledge and confidence in your ability to provide a fundamentally sound belay.

The post AAC Universal Belay Standard: Toproping appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

SCARY (AND TRUE) TALES FROM A CRAG NEAR YOU

The post Unbelayvable: A Toprope of Dubious Quality appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Every Monday we publish the most unbelievable stories of climbing stupidity submitted by our readers. See something unbelayvable? Email unbelayvable@climbing.com and your story could be featured online or in print. For more Unbelayvable, check out the Unbelayvable Archives.

I was at Gimmer Crag in the Lake District, England. I saw a young climber struggling on F Route, a grade VS (~5.7) layback crack that gets steeper and more committing as you go higher. He called up to friends at the top of the cliff to set a toprope. They did, then lowered a pre-knotted rope, which he clipped to his harness. He then climbed quickly and confidently. As he pulled up onto a ledge just below the top, he was surprised to see his end of the rope continue up past his nose without him. Given that he’d just climbed 60 feet on a toprope of dubious quality, his shouted expletive was perhaps understandable.

—Patrick, via email

LESSON: Understandable perhaps, indeed! If I climbed 60 feet and then found out that I was never on belay, I would yell some things. That’s the proper way to handle that situation from that point. Of course, you would be better off if you never got to that point in the first place. I don’t know what went wrong here. I suspect a miscommunication. Regardless, the advice is the same. If the climber had double checked the knot before he started climbing, he should have caught the problem, whatever it was. Always double check your knot! Make sure it’s properly tied and through both of your tie-in points (or if clipping in with a carabiner like above, that the knot is properly tied with enough tail and that the carabiner is locked). If someone else is around, make them check it too. All human beings make dumb mistakes. If you climb long enough you will probably make a dumb mistake. If you always double check your system, you should catch that mistake before it turns into a dangerous mistake.

We want to hear your Unbelayvable stories!

Email unbelayvable@climbing.com and your story could be featured in a future edition online or in print. Unbelayvable photos are welcome, too.

The post Unbelayvable: A Toprope of Dubious Quality appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

SCARY (AND TRUE) TALES FROM A CRAG NEAR YOU

The post Unbelayvable: A Bad Anchor is Worse Than No Anchor appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Every Monday we publish the most unbelievable stories of climbing stupidity submitted by our readers. See something unbelayvable? Email unbelayvable@climbing.com and your story could be featured online or in print. For more Unbelayvable, check out the Unbelayvable Archives.

I brought some friends to a popular toprope crag. We met two guys climbing an easy 5.4 and decided to share ropes with them. They described their anchor for me: a sling around a chockstone with lockers. It sounded OK. I frequently solo this route, so I figured anything was better than nothing. When I reached the anchor, I found a single sling around the chockstone with a single locker, and upon closer inspection, I found that the chockstone was quite loose. If the route had been any more committing I would have peed myself right then and there. After building a proper anchor, I rapped back down and asked my new friends if they would appreciate some helpful criticism. Thankfully, my suggestions were accepted graciously.

—Tristan, via email

LESSON: You know that expression about how you shouldn’t look a gift horse in the mouth? That does not apply to climbing anchors. If someone offers you a climbing anchor, you should look it directly in the mouth and inspect it closely. Unless you see an anchor for yourself, you’re taking the anchor builder’s word that their anchor is safe. That doesn’t usually include their experience or the level of risk they’re willing to accept. It can be a great time saver to share ropes, but always examine any anchor before you trust your life or your partner’s to it.

We want to hear your Unbelayvable stories!

Email unbelayvable@climbing.com and your story could be featured in a future edition online or in print. Unbelayvable photos are welcome, too.

The post Unbelayvable: A Bad Anchor is Worse Than No Anchor appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Scary (and true) tales from a crag near you

The post Unbelayvable: Eight Awful Words appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Every Monday we publish the most unbelievable stories of climbing stupidity submitted by our readers. See something unbelayvable? Email unbelayvable@climbing.com and your story could be featured online or in print. For more Unbelayvable, check out the Unbelayvable Archives.

I was at my local climbing gym on a Tuesday afternoon. The facility was relatively quiet, with the exception of a couple toproping in the corner. It was easy to see that this was their first time climbing. As I was about to lower my partner, I heard eight awful words: “Honey, let me take your photo up there!” I turned to see the belayer move her left hand onto the brake strand so she could take out her phone with her right. Then, while trying to strike a pose, the climber slipped off his foothold. In the moment of panic that ensued, the belayer dropped her phone and let go of the brake with her left hand while grabbing the rope with her right. She managed to catch him before he hit the ground, but it sent him into a pendulum swing. All that could be heard was a quick yelp and then a loud smack as belayer and climber collided. Luckily everyone walked away from the incident with just bruised egos.

—Nick, via email

LESSON: If there is only one belaying rule that you should never, ever break, it is this: Never take your hand off the brake strand. There’s no task more important for a belayer than ensuring the safety of your climber. If you do find yourself in a situation where you need to release the brake strand, tie a backup knot first. Have your climber go in direct to a bolt or piece of protection, then tie an overhand or figure eight on a bight in the brake strand below your belay device.

We want to hear your Unbelayvable stories!

Email unbelayvable@climbing.com and your story could be featured in a future edition online or in print. Unbelayvable photos are welcome, too.

The post Unbelayvable: Eight Awful Words appeared first on Climbing.

]]>