Our case for low-stakes sending

The post Is Your Projecting Toxic? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

If you’ve ever poured months of your life into a project, you probably know the feeling of the dreaded “One Fall” zone. If you don’t—well, you’re a way better climber than me. But what happens when you’ve lost count of how many times you’ve one-fallen a route and are dangerously approaching triple-digit attempts?

When I’m coaching individuals to climb their hardest, we call this part of the projecting phase the “One Fall Hell.” And it’s in this “One Fall Hell” where some of the most toxic projecting moments inevitably occur.

The pitfalls of One Fall Hell

Projecting becomes an endless redpoint cycle: Every attempt ends in the same place, just short of success. No matter where I fall, I can pull back on, climb through, and reach the top—earning the dreaded “I’m so close!” without ever actually clipping the chains.

At first, this can feel motivating. But stay in this zone too long, and projecting shows its toxic side. The curiosity that drew you to the climb fades. Movement becomes mechanical, automatic, uninspired. Self-doubt creeps in. Negative thought loops start to run the sessions. What should feel playful and creative instead begins to feel heavy, stifling, and draining.

Projecting at your absolute limit will always cut both ways. Done well, it’s exciting, full of growth and accomplishment. Done poorly, it can bring stress, frustration, comparison, body-image issues, and unhappiness.

What toxic projecting looks like

When I was in my late teens, I lived deep in One Fall Hell. I jumped on climbs far above my ability with little understanding of movement, pacing, or even how to use clipping stances effectively. I thought raw effort would be enough. And it wasn’t.

The result was ugly. I became unbearable—hyper-focused, self-absorbed, uninterested in others. I was the exact opposite of the climber and the person I wanted to be.

From here, a pair of outcomes diverge. One leads to grinding through the cycle until you finally send. But if you’ve been trapped long enough, clipping the chains may feel more like relief than accomplishment. The other possible outcome is shelving the climb in the “someday” category—or walking away altogether.

On the flip side, there’s the danger of never trying your hardest. I’ve met plenty of climbers who live in the comfort of a “someday mentality.” They avoid the discomfort of real effort, and in doing so, hold themselves back. That’s where potential goes to die.

So what’s the answer to avoid toxic projecting?

It’s time to incorporate a low-stakes projecting mentality. (And to be clear, I’m talking about what for many, is a normal climbing mindset.)

This is why balance matters. High-stakes and low-stakes projects have to coexist. You can chase your peak potential, but you can’t live there all the time. Routes in the range of “I can do this in three or four sessions” build confidence. They give you a foundation you’ll need when you’re deep in the grind of harder, potentially more obsessive projecting.

And here’s a wild idea: Low-stakes projecting isn’t just about the difficulty of the route. It’s also a mindset—an approach that takes the pressure off the outcome, even when you’re on one of the hardest climbs you’ve ever touched. That, too, is a low-stakes approach.

What does this look like on the ground? Project a route, but don’t invest your entire soul and ego into the outcome of a redpoint. As you go into the projecting experience, set more goals than just sending. Instead of only projecting with the goal of sending a specific route, project to learn, project for the experience, or project just for the fun of it.

Failure is part of projecting. In fact, if you’re not failing, it’s not really a project, right? The paradox is that failure is the healthy part of climbing. It keeps us learning, growing, and pushing toward our potential. The real trick is shaping that process into something healthy, instead of something that tears you down.

The post Is Your Projecting Toxic? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Why most of us shouldn't try to train like Janja Garnbret—or your favorite YouTuber.

The post Don’t Fall for the Training Trap appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

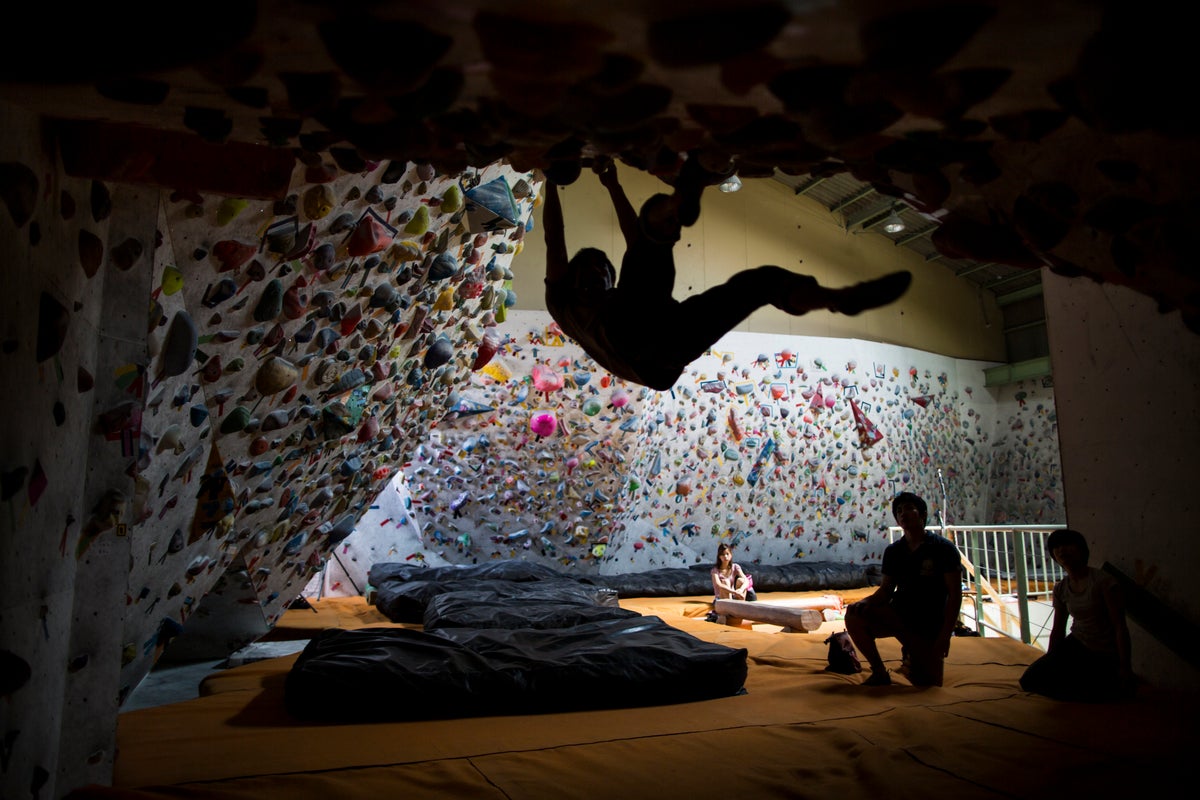

Sitting on the edge of a bouldering mat, I eavesdropped on a conversation between two college-aged kids.

“Well, Janja [Garnbret] just climbs to train, so I’m just going to train like her,” one said.

I frowned thinking I misheard. Were they talking about the two-time gold Olympian?

For a few minutes, I listened as they bounced ideas back and forth about building training programs modeled after their climbing heroes, pieced together from YouTube clips and social media posts. Their plan? Climb six days a week, two to four hours per session, with morning workouts and “supplementary sessions” in between.

“How long have you two been climbing?” I finally asked, a little concerned.

Turns out, they had only started climbing eight months earlier. They’d found climbing as a much-needed stress release from the grind of freshman year.

I wished them luck, but the exchange stuck with me. It highlighted just how easy it is to get swept up by online climbing training advice. Everywhere you look, flashy programs promise quick gains: Do these exercises and you’ll climb harder in no time. But the reality is far messier.

I see two big problems with these cookie-cutter approaches:

1. Mimicking pro routines is a shortcut to injury or burnout.

Elite climbers like Janja Garnbret can handle massive training loads because they’ve built decades of base strength and skill. And nutritionists, physiotherapists, and coaches help keep them healthy and balanced. For the average climber, jumping into that level of intensity is unsustainable and often harmful.

2. When someone who isn’t a pro is selling a program to train like a pro, that might be a problem.

This is where the insidious nature of online training can cause real problems for a new climber looking to build their training programs. Vetting these sources often goes by the wayside, putting participants at risk from the get-go.

A spreadsheet and a YouTube link won’t fix your form. Without proper coaching, it’s easy to ingrain poor habits, bad posture, sloppy movement, and over-gripping. This can lead to real injuries down the line.

What non-professional climbers should look for in training plans

Early training for recreational climbers should be about building healthy movement patterns and correcting mistakes, not rushing headlong into faux-pro workouts.

Having been one of those kids, I’ve seen the difference between internet-based training and the results I got when I was fortunate enough to work with Dicki Korb from Kafe Kraft in Germany. Having a coach’s eyes on my climbing was invaluable. He provided instant feedback and corrected my form on the spot.

It’s really important to find a program that allows regular check-ins with a coach. A hybrid of online and in-person training builds responsibility and accountability in a way a purchased spreadsheet never will. Many excellent coaches can observe your sessions via Zoom, which is a great option if you’re committed to working with a specific trainer who doesn’t live near you. Just make sure whoever you’re working with gets eyes on you and your form.

But the main takeaway is this: If a program doesn’t personalize its plan to account for your own climbing abilities, that’s a risk I wouldn’t take. The online space is virtually anonymous. Few checks or support systems exist for new climbers. Oh, and surgery is expensive. Unfortunately, falling victim to the latest training craze without proper context is one of the quickest ways to find that out.

The post Don’t Fall for the Training Trap appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Weird ways to free stuck limbs, cams, or other oddities in your time of crisis

The post Why You Should Always Climb With a Partner Willing to Spit On You appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

“I’m sorry… did you just say five gallons of olive oil?” I relayed down the line.

Slack-jawed, I stared at my current situation—50 feet off the deck, my knee hopelessly wedged in a 5.11+ offwidth. Mary Eden—famous for her Instagram personality, brutal desert sends, and general aura of “desert goblin”—was dangling on a fixed line, laughing as she tried to free my leg from the gaping maw of a Moab splitter.

“Yeah,” she said between chuckles. “This guy’s knee was so stuck that they had to call SAR. After like eight hours, they finally freed him by dumping gallons of olive oil down his leg.”

Laughter below floated up through the shimmering desert heat, carrying with it mental images of Jason Kruk’s infamous 2010 Squamish incident—hungover, stuck in an offwidth, puking, and ultimately—after about 25 minutes and a bold-brown decision later—shitting his pants. That episode turned “Boogie ’til You Puke” into “Boogie ’til You Poop” and even earned a “web redemption” on the popular Comedy Central series Tosh.0.

Unfortunately, I wasn’t alone in my humiliation. Mary and I were in the middle of teaching a group of 10 people the finer points of offwidth climbing—and here I was, their instructor, offering a live demonstration of “what not to do.”

“I could spit on your leg,” Mary said, giggling like the demented impish fiend that she was.

“If I ever get free,” I threatened, “I will find you, and I will make you pay.”

I tried to stay calm. I did not want this climb to be renamed in my honor with any sort of bodily function reference or some sort of defecation-suit—the court of appeals would just laugh me right out of the room. After 10 minutes of awkward twisting, cursing under my breath, and bargaining with the crack gods, my kneecap Houdini’d past a constriction, freeing me from the sandstone’s iron-maiden-like grip.

With a bruised knee and an even more bruised ego, I sulked and reflected on my latest mess-up, but grateful my knee had ultimately freed its bindings.

But what if it hadn’t? What if the desert demanded more effort? We didn’t have olive oil, but climbers usually have… other resources.

Beer, for one, though not a microbrew; no one is sacrificing a $17 craft hazy IPA for a rescue. Chalk could work, I guess, if you’re into the “dry rub” method, but I thought chalk was supposed to make you stickier?

Duct tape? Only if you’re willing to make things much, much worse before they get better. But let’s be honest, there’s only one tried-and-true combo to free anything from stuck cams to elbows, fingers, knees, and toes from a crack. Beer and spit, which are basically the Swiss Army knife of the dirtbag medicinal arsenal, right up there with 10-cent cans of cat food, or the “walk it off” method.

Moral of the story? Don’t panic, respect the crack’s authority, and always have a partner willing to spit on you.

The post Why You Should Always Climb With a Partner Willing to Spit On You appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Advancing your climbing? Don't get too caught up in the numbers.

The post I Climbed One Grade Harder and Now I’m Insufferable appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

There’s no better feeling in the world than sending your project. But breaking into a new grade? That’s a whole different kind of high—one that can turn a little … insidious.

In climbing, there are two classic steps to this unchecked progression. Over the years, I’ve seen the overwhelming cycle repeat itself: First comes the hubris, then the fall.

One of my favorite tragic heroes was a climber at my local gym. For the sake of this story, let’s call him “Chad.”

Back in the early 2000s, Chad had just sent his first 5.12b and was dead set on breaking into the 5.13 range. But, instead of building a proper pyramid or refining his technique, Chad dropped a few hundred bucks on a six-week training program: crimp strength, mobility, conditioning, coordination, endurance, and power. The works. Bouldering circuits, campus board sessions, and hangboard routines (this was pre-LED board era) became his religion.

Then, he picked a project in Rifle, Colorado, of all places. One of the most sandbagged crags in the U.S., with slick limestone, brutally specific beta, and long, pumpy routes. Instead of choosing something within reach, Chad went all-in on one of the longest, most sandbagged 5.13bs in the canyon.

Each session ended the same: no links, full meltdowns, epic wobblers. Shoes were ripped off and flung into the river. Chad’s rage was legendary, but don’t feel bad for Chad—feel for his belayer.

Yet somehow, Chad stuck with it. He trained. He suffered. He kept showing up. And by week eight, in a twist of fate, he clipped the chains. His first 5.13b (8a). Because, as his European friends insisted, 5.13a doesn’t count.

This is where the story could’ve gone differently.

Chad could have taken the win, acknowledged the effort it took to climb that one route, and gone back to rebuild his base, slowly developing true competency.

Instead, he chose the second path.

He started calling himself a “5.13 climber.” He sprayed. Hard. To anyone who would listen, especially to the unfortunate souls in the neighboring town. In the gym, at the crag, he’d talk about his send to anyone within earshot. People nodded along, half-listening. It was … insufferable.

Then came the Great Humbling.

Chad jumped on the next 5.13—this one a little easier—to see all the “gains” he possessed. He was completely and utterly shut down. A wobbler was thrown, and a stick-clip may have been lost to the trees.

His mistake? Thinking that one send meant he could now climb any 5.13–that he was a 5.13 climber. Oh, and being truly insufferable.

Chad would’ve been better served by this truth. Be proud of your accomplishments, but understand that success in climbing isn’t linear. Advancement means embracing failure just as much as success. If you can do that—if you can truly accept your reality—your potential is yours to grow.

P.S. That Chad guy? Yeah, that was me.

The post I Climbed One Grade Harder and Now I’m Insufferable appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

An op-ed on why it's better to go (relatively) small on your first big wall

The post Thinking of Climbing El Cap as Your First Big Wall? I Wouldn’t. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Yosemite Valley is the granite mecca every climber dreams of visiting at some point in their journey. Towering walls, glacial polish, and stone streaked in blue, gray, orange, and gold—few places are as iconic or awe-inspiring. And standing above them all—literally and figuratively—is El Capitan.

Rising 3,000 feet from the valley floor, El Cap has captured the imaginations of climbers since Royal Robbins in the 1950s and ‘60s, and has humbled climbers ever since. Its sheer face, endless features, and relatively easy accessibility offer a vertical playground for those bold enough to commit.

But as tempting as it may be to make El Cap your first big wall, I’m here to say one thing: Don’t.

You can go for it, and people have. But the reality? More often than not, your dream ascent turns into a logistical nightmare. In all likelihood, you will find yourself stuck in a bottleneck on the Nose or Salathe (some of the world’s most-attempted big wall routes). You’ll discover your hauling systems don’t work. You’ll be working with gear you’ve never practiced with. And let’s just say your first experience pooping in a tube mid-air should probably not be during a multi-day epic surrounded by other parties.

Before you pack that shiny new haul bag or invest in a deluxe portaledge, here are a few things to consider. First, are you overestimating your and your partner’s abilities? This is a common mistake for first big wall climbs, so take a deep breath—and a solid dose of humility.

Let’s start with systems. Hauling, jugging, cleaning, and organizing on route are all skills that take years to perfect. If your experience is at a single-pitch crag—or worse, the gym—you’re in for a rude awakening.

Efficiency is safety on a big wall. Without experience, when things go wrong (and they will), knowing an effective way out of a situation is the safest way to go. Figuring that out 2,000 feet off the deck isn’t a great place to start.

Logistical overload is another major aspect of climbing on a wall that a lot of people forget to take into account—even veterans of big-walling. Mental endurance and managing exhaustion whilst watching weather windows, water rations, food consumption, time management, and more becomes the priority when navigating that kind of terrain. Doing that while on a wall next to several other parties wanting to bypass you? Real rough.

For what it’s worth, don’t give up on El Cap. Make it your second wall experience. Take on the challenge after you have at least tried to climb a multi-pitch that involves an overnight to see what it’s like to set up a bivy in the dark with a headlamp. To be honest, to make your climb up El Cap more fun, try a lesser-traveled big wall. Choose one that’s less demanding, yet still offers massive amounts of experience and learning. There are several in the Yosemite Valley itself, as well as routes in other national parks like Zion in Utah.

El Cap isn’t going anywhere. In fact, it gets better and safer when you’re ready. Your systems will be faster. Your gear will make sense. Your partner will (fingers crossed) still be your friend by the end. Those are pluses that are worth the wait.

The post Thinking of Climbing El Cap as Your First Big Wall? I Wouldn’t. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

An op-ed on why pulling on plastic has its shortfalls. Here's what I recommend doing instead.

The post I Run a Climbing Gym. Here’s Why I Tell People to Climb Outside More. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

It’s 2 a.m. on a sleepless night. A dull red light illuminates my pitch-black room as I doom-scroll through the dumpster fire that is my Instagram algorithm. I’ve left the wholesome cat memes. Now, I’m navigating influencers pushing the latest climbing trends and advertising their “training programs” to help you send your project.

“Learn to climb 5.12 in just two weeks!”

“Train on a board to get the gains for your project!”

These tropes play over cliché music. They are layered with catchy cuts, smiles, and a kernel of good advice—but mostly, it’s just a garbage diatribe searching for clicks and sign-ups, all with promises that pulling on plastic in a gym will get you to the chains of your outdoor project.

I believe training in a gym is a useful tool. It’s especially advantageous for those who work full-time jobs, have kids, or need to build a foundation of strength, power, or endurance to achieve their climbing goals. However, it isn’t a substitute for being outside. If the gym is your only approach to sending, you’ll likely walk away from a session on your outdoor project feeling disheartened and unmotivated.

I’ve taught several clinics on the process of redpoint climbing with the American Alpine Club’s Craggin’ Classic Series from 2012–2024 (R.I.P.) and have had the fortune of working with a gamut of people with wildly different climbing experiences. The participants ranged from teenagers to a spry 70-year-old, and from people just learning how to top-rope belay to those questing after their first 5.14. One common thread among all these climbers? The desire for some kind of training program—a shortcut or a quick way to improve their climbing immediately.

My answer to those queries was simple: “No amount of burpees, one-arm hangs, lifting exercises, or pull-ups will solely get you through a route or boulder problem.”

This may have been a disappointing answer, but I think time on route, rather than gym training, is king. Getting on your project day after day and gaining experience and fitness will do more to help you meet and surmount your goal than doing trending exercises to “strengthen that core” without knowing how to apply the gains.

What’s the best way to get started? First, find a project that inspires you. You’ll be spending a lot of time on it, and if you’re not inspired by what you’re doing, then there’s little reason to do it in the first place.

It’s also worth having projecting friends or a partner who is on the same page. Don’t drag out friends or significant others who hate the project mentality; it just causes rifts and a lack of focus.

Next, get comfortable on the route. If you’re afraid of falls, extend draws for more comfortable clipping stances. Find a belay partner you trust implicitly. Remove any variables that keep you from focusing on the climbing.

Last, I suggest setting a timer. Honestly, this may have saved my marriage and climbing partnership. Give yourself a 40- to 60-minute timer for sussing out beta. This way, no one gets upset about long belays, and the climber doesn’t feel rushed.

There’s no silver bullet to your next send, but putting in the time (and doing it on rock) is a surefire way to increase your chances at success.

The post I Run a Climbing Gym. Here’s Why I Tell People to Climb Outside More. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

What my big wall mentor—and my arrogance—taught me on ‘Hearts and Arrows’ (5.12b) in 2012

The post My Mentor Taught Me Something Invaluable on The Diamond. But the Lesson Didn’t Come Easy. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Alpine starts are the absolute worst.

As my alarm blared with the urgency of a code-red nuclear meltdown, my climbing partner, Mayan Smith-Gobat, groaned to my right. I wished I felt as groggy as she sounded, but I’d spent most of the night begging my overanxious mind for sleep. In less than four hours, I’d be on my first big wall: the East face of Long’s Peak, The Diamond. Our goal was to onsight a newly established route called Hearts and Arrows (5.12b), equipped and freed by Bruce Miller and Chris Weidner. The nine-pitch granite masterpiece takes the center overhang of the wall and tops out at 14,000 feet.

I checked the time: 2:30 a.m. I sat up in our rented minivan—my Jeep Wrangler had thrown an engine rod a few days earlier on my way to pick up Mayan from Denver International Airport. When I flicked on my headlamp, its beam cut through the inky darkness. The cargo door clicked, and with a mechanical whir, slid open. I slithered out of my sleeping bag, my feet finding cold asphalt. Above, a dusting of starlight scattered between the branches of alpine needles, faintly highlighting the thin path that marked the beginning of what would become a very long day.

“We need to get moving,” Mayan said, her trademark Kiwi accent cutting through the stillness.

New Zealand-raised, Mayan had honed her skills on the granite walls of the Darran Mountains near Milford Sound on the South Island. Quickly outgrowing her experiences Down Under, she pursued big wall climbing, ticking some of the most notable and sought-after lines in Yosemite Valley—namely, the Salathé on El Capitan, and eventually, the women’s speed record on the Nose.

I stuffed our meager rations of water and bars into my hastily packed bag, along with a 60-meter rope, shoes, a harness, and a rain jacket.

“Where’s the gear?” I asked, looking around the van.

“I borrowed some from a friend who’s working a line up there; it should be stashed,” she replied.

“That’s convenient,” I thought as I slung my bag onto my shoulders and clipped the waist belt.

In retrospect, I should have asked for more details, what gear we were taking, or what we would need in case of emergency. I can now conjure a slew of other questions that would help me be my own advocate for my safety, or for our little party of two. But no, this was just the beginning of a series of inexperienced and arrogant decisions that occurred for the rest of the day.

Instead of leaning into my inexperience, I had the “fake it ‘til you make it,” mentality. My partner was a true pro-climber. I thought I had all the experience I needed to be a bold and adventurous big wall climber. While I barely knew how to tie a clove hitch, it was only eight or nine pitches of climbing, none of which were harder than 5.12. Surely, my days in Rifle Mountain Park sport climbing would prepare me for this alpine big wall.

The approach

We trekked through darkness, each step rhythmic to my labored breath. As we gained elevation, we came across spring-watered marshes, a flowing brook, and, thankfully, a small pit stop to drink water.

“The most important thing, Ben, is to stay hydrated,” Mayan reminded.

“I know, it’s not like this is my first time climbing outside,” I replied, dry mouthed and thirsty.

Genuinely embarrassed by this small chiding, I admit that I hadn’t taken a single sip of water throughout our three-hour hike. I drank half of a Nalgene and refilled it in the spring.

An hour later, dawn’s light painted the tapestry of the Diamond; the reflection of the 1,000-foot giant rippled on the surface of Chasm Lake. A talus field of broken granite giants littered the base of the wall—a testament to time and the chaos of loose stone freed from the cliffs surrounding us.

Navigating the maze of talus pitfalls and car-sized blocks, Mayan disappeared from view to unearth the hidden gear stash. Already exhausted from the elevation, I sat and searched the wall for our line. I could see other parties already headed up the left side of the face, having bivied the previous night. I felt a pang of jealousy that they were starting somewhat fresh, or at least more caffeinated.

“So we didn’t walk as fast as I’d thought,” Mayan said as she approached with a small stash of gear in her hand. “We can solo up to the Broadway Ledge, which wouldn’t be too terrible, or we can rope up, but that will take more time.”

I’d never free soloed before, let alone the 300-400 feet of somewhat scary, broken, low-angle granite. Most parties rope up for these fifth class approach pitches to the top of the Broadway Ledge and what are considered the beginning pitches of the Diamond’s East Face. But I was confident in my ability and didn’t think too much of it.

To be honest, I felt that I needed to perform for Mayan and act the part of an experienced partner, even though I lacked the acumen. “Is that all the gear we’re taking?” I asked, seeing the fistful of cams. (I would soon learn the gear she took from the stash consisted of slightly less than a single rack, from Black Diamond Camalot #3s to a sparse smattering of C3 finger-sized cams).

“Yup, we are going light and fast today,” Mayan replied.

“Great.” I said, with a pertinent question catching in my throat, and a bit of unease in my chest.

“Thoughts?” Mayan questioned, opening the floor dissent.

I’d met Mayan just a handful of weeks earlier and climbed with her only a few times, so we were still in the initial “feeling out” stages of our climbing partnership. Calling my knowledge of systems, trad, and mountains “green” would be giving me too much credit. Mayan, on the other hand, was famous for her wall climbing, bold ascents, and general mastery of this form of climbing, putting me in the dangerous position of blind trust.

“You’re the expert!” I said, switching the subject, wanting to pretend that I was equally ready.

A sound of thunder broke the stillness around us. Confused, I looked up at a bluebird sky, only to glance back at Mayan and watch her eyes go wide as she quickly moved to our right.

“Rock!” The shout from above came from an unknown source as I watched a series of microwave-sized blocks tumble down the wall. We were close enough for it to be dangerous, but far enough away that I didn’t understand why Mayan took off so quickly.

“Get over here, you idiot!” she called out.

Without hesitation, I started to move toward her, though I was confused, because it really didn’t seem like a super dangerous situation.

“Why the concern?” I asked as we took shelter behind a large boulder.

“Rocks can bounce around and be unpredictable; better safe than sorry,” she said.

Years later, I still remember that sage advice, as well as the sheer lunacy of holding that mentality, while simultaneously carrying less than a single rack for what we were about to accomplish.

Safe from the rockfall, Mayan clipped what I’d dubbed the “diet rack” to her harness and began walking directly toward the part of the wall where the blocks had just tumbled down.

“Where are you going?” I asked.

“That’s where our route starts. Let’s go,” Mayan trailed off.

Grabbing the rope and slinging it onto my back, I smiled and started the grand adventure of my first big climb. It was 5.12b and I’d just climbed my first 5.14 sport route—how hard could this be?

The humbling

Tears streaked my cheeks as the wind whipped against my rain jacket. The valley floor, a little over a thousand feet below, felt perilously distant. I was sitting at a hanging belay in space, on a single Black Diamond green C3 (a cam about the width of a finger). The wind rocked me in my harness like a cradle, just waiting for me to fall and crash down upon the rocks below.

I’d just witnessed the most inspiring and fucked-up climbing performance of my life. This holds true even today, a little over a decade later, as I recount this story. Mayan had entered the crux—pitch seven, the dreaded 12b—full of vigor. However, before she started up on the pitch, she swapped my perfectly equalized three-cam trad-anchor for that single cam. Her rationale for this significant anchor downgrade? She curtly noted that she needed the gear, before questing off into space for an onsight attempt.

Due to a lack of natural protection, Mayan endeavored to make it to a single rusted pin, wedged into the wall an uncomfortable distance from the belay. She moved 10 feet up without a single placement, then 15, then 20.

“Umm, can you place something?” I politely shouted up to her.

“Nowhere to place. I’m focusing. It’s chossy here,” she shot back.

Small rocks crumbled under her foot as she navigated the sea of overhung rock. I side-eyed the one finger-width cam I was anchored into, sunk into a shallow crack. This was the only gear that would potentially keep me and Mayan attached to the wall if she fell. As Mayan came within five feet of the fixed pin, a wave of relief started to wash over me. A grunt, then a curse emanated from Mayan as a baseball-sized rock broke off in her hand. She began to “barn door,” the right side of her torso hinging outward by the momentum of the unexpected break.

Two appendages—one foot, one hand—were all that kept her from launching into the void, leaving me to wonder: Would our single finger-sized anchor sustain a 40-foot factor-two fall? Overwhelming dread sank into my bones, cutting deeper than the frigid winds sweeping the wall.

“This is how I fucking die,” I thought.

Slow motion and crisis mode hit me as I prepped to … I don’t know. To this day, I actually have no idea what I would have done. There was truly nothing I could do but imagine all the scenarios where, in the valley below The Diamond, I had the capacity to ask this unhinged Kiwi to maybe take more than a fucking barebones rack up the wall.

Cursing the gods, I’d just spent the last six hours in a meat grinder, exhausting my mind, body, and resilience. All I wanted to do was go home, but that was no longer an option. On the pitch before, Mayan had made a casual statement, that in retrospect, should have been a question.

“This is the point of no return. We either go down now, or we have to summit, because our rope isn’t long enough for retreat.” Mayan said, as she collected the gear to re-rack for the crux pitch.

Did I even have an option? Was there even the possibility of discussion in that statement? Was the subtext, “We can go down if you want, but that is most certainly not what I want.”

Mayan was close to achieving her goal of onsighting the wall, so who was I to hold her back? Guilt for feeling scared, being unable to keep up, and generally feeling inferior took hold of my decision-making. I knew that the idea of no retreat is never a good thing in the mountains. But I considered Mayan the expert, far superior in judgment and skill. Surely, there was no way that she would put us in unnecessary danger.

Right?!

Not wanting to seem weak and bail on our arrangement, I decided to err on the side of my frail masculinity and lead with, “For sure! I’m great. Let’s fucking roll!” I pasted on the feigned confidence that I’d lost on the first pitch of this godforsaken day.

So there I sat, a mess of snot and tears, shivering as my breaking point brick-walled me into becoming a lemming. I watched Mayan teeter us toward a dirt nap that I didn’t know I’d signed up for. I’m no physicist, but it didn’t take a lot of calculations to know that if she fell, it was game over. We would certainly bolo our way to the teeth of jagged rock below. What poisonous internal rhetoric got me into this position, where my anxious snot dripped uncontrollably to the valley below, you may ask?

Blind trust

As I contemplated my life’s end, I looked up to see Mayan kick her left leg behind her as if in a choreographed action movie stunt, then counterbalance the swing, re-establishing her control after her barn door. She latched her left hand back onto the wall.

Quickly moving to the pin, she slammed a quickdraw into the eye of protection and whipped the rope into place.

“Oh, thank god!” I exclaimed, as I almost passed out from relief.

“Hold on a tick,” Mayan said and gently slid the pin out of place and held it in her hand before she reinserted it back into its original state.

My jaw dropped. My hope died.

“How long until you can get a placement?” I asked, sliding a mask of apathy in place. The emotions were just too much, and I had nothing left in the tank.

“Not for another 10 feet or so,” Mayan replied, trying to gauge her distance to the alluring twin cracks above her and the first solid placement.

“Well, hopefully, that was as exciting as it gets,” I prayed.

Mayan quickly dispatched the rest of the pitch without much incident and soon I was pulling on my downsized, downturned sport climbing shoes. Feet aching, I met Mayan at the anchor.

“I’m fried. I am not going to be able to lead if we want to get to the top,” I said.

“That’s fine, just do your best and we will get there.” Mayan said with a finality that I didn’t like.

The loop

To my chagrin, the next pitch went about as well as the last pitch. Pitch eight was a hands- and fingers-sized crack—features with which I had zero experience. Mayan had easily sent pitch eight, making it look like 5.8. She was well on her way to onsighting her objective. Meanwhile, I had long ago given up, opting for pure survival, and changing my objective to “make it to the top.”

Inspired by her tenacity and strength, I felt a fourth or fifth wind hit as I disassembled the anchor, pulled my heels onto the iron-maidens I called my shoes, and prepped to climb. As Mayan put me on belay and took out extra slack, my life line cinched down in the crevice of the roof 15-20 meters above. In an attempt to take in slack, she yanked the rope through the belay device, further welding the rope into the crack and sealing my fate.

“Up rope!” I yelled, chalk dusting my fingertips.

The wind carried Mayan’s voice as a whisper from above: “Rope’s stuck …”

“What? Up rope!” I yelled again.

“I can’t, the rope is jammed …” Mayan shouted down.

“What do we do?” I asked.

“You climb and don’t fall! It could cut the rope!” she yelled.

“No! Absolutely not! What the hell?” I screamed in protest, even though we both knew there was no other choice. We couldn’t go down, and I would basically have to solo 15-plus meters of the pitch to make it to the end of the roof and hopefully dislodge the rope.

I couldn’t even get angry after the initial shock. I was just sad.

Resigned to my fate, I began to climb. The opening of the pitch was an off-vertical incline that led to a jutted roof, so I had to climb both into, then out of the rock. As I inched my way to the climb, my loop of impending doom grew. But so did my determination. To avoid slips and slides, I moved methodically and carefully.

I drained more of my luck bucket as I navigated the slick granite, noticing and avoiding small pockets of seepage—the alpine wall adding more spice to my situation. At the back of the roof, I prepped and planned for a series of jams and layback techniques, then quested to the pinch point. The death loop was about 15 meters below me. Mayan had been able to wrench a few precious handfuls of line through the wedge, but ultimately not enough. My feet stayed melded to the rock, my toes curled through the rubber, trying to increase any purchase as I eased my way toward the end of the roof.

I hit the choke point at the end of the roof flawlessly and jammed back into the crack to anchor my body, trying to position myself to free the rope. I refused to move upward until I released that line from the jaws of Pitch Eight. It took a few extremely hard yanks to feel the give of the line as it freed.

“Up rope, please dear god, please!” I cried in joy.

I felt the rope slide upward quickly as Mayan marathoned the line through the belay device. The comfortable tug against my harness signaled that I was okay for another moment of this day. My savior and tormentor smiled as I clipped the anchor a few minutes later.

“Last pitch of 5.9,” she said, beaming at the prospect of onsighting the line.

“How can you be so calm?” I wanted to ask. But by the time I got around to it, she had already taken off and 20 minutes later, called for me to climb.

We stood atop The Diamond looking at the Rocky Mountain Chain. Mayan had onsighted Hearts and Arrows and was elated. I was just happy not to have shit my pants in fear and to have made it to the top.

The lesson

In retrospect, I can’t say I was happy as I thought about how that day on The Diamond had unfolded. I was angry at some of the risks we took. I blamed Mayan for a lack of consideration, before I realized that we had very different levels of acceptable risk and danger mitigation. A lot of what had happened wasn’t her fault.

Of course, I also bore some responsibility to ask questions and not just placate a new partner—especially a pro. My own arrogance of thinking that climbing on a rope was the same, regardless of the discipline, is laughable now. And my misguided ego of grades and environments humbled me.

With Mayan, or with any mentor, I learned that day that I needed to advocate for my own thoughts and forge a partnership, not just a guided tour or a lesson in a classroom.

I could barely understand Mayan’s vast ocean of knowledge and experience, especially considering the outcome of our attitudes at the top. For Mayan, this was just another day out in the mountains that lit a fire in her heart for more. There was no malice, or intentional hazing from her—she was just sharing her excitement.

Our experience on The Diamond was something I wanted to learn from. In a weird way, I had found not the mentor I wanted, but the one I needed to help foster what I wanted to do in the mountains. To be honest, I got lucky. My job now was to put that luck that I’d used up into my “experience bucket.”

In all of my adventures that followed with Mayan, she would put me through the wringer, testing me, terrifying me, and growing my climbing experience. But, unbeknownst to Mayan, the greatest lesson she gave me during my experience on the Diamond was the seed of responsibility to take care of my own well-being. She taught me to ask questions of people who I perceive to have more authority in situations where my life is—for a lack of better word—affected. That, and, of course, to take a bigger rack and a longer rope.

The post My Mentor Taught Me Something Invaluable on The Diamond. But the Lesson Didn’t Come Easy. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

When your comfort zone is pushed, you become more curious, more adventurous, more dynamic—a better climber.

The post Five Tips for Expanding Your Comfort Zone appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

The following story originally appeared in the February 2015 issue of our print edition.

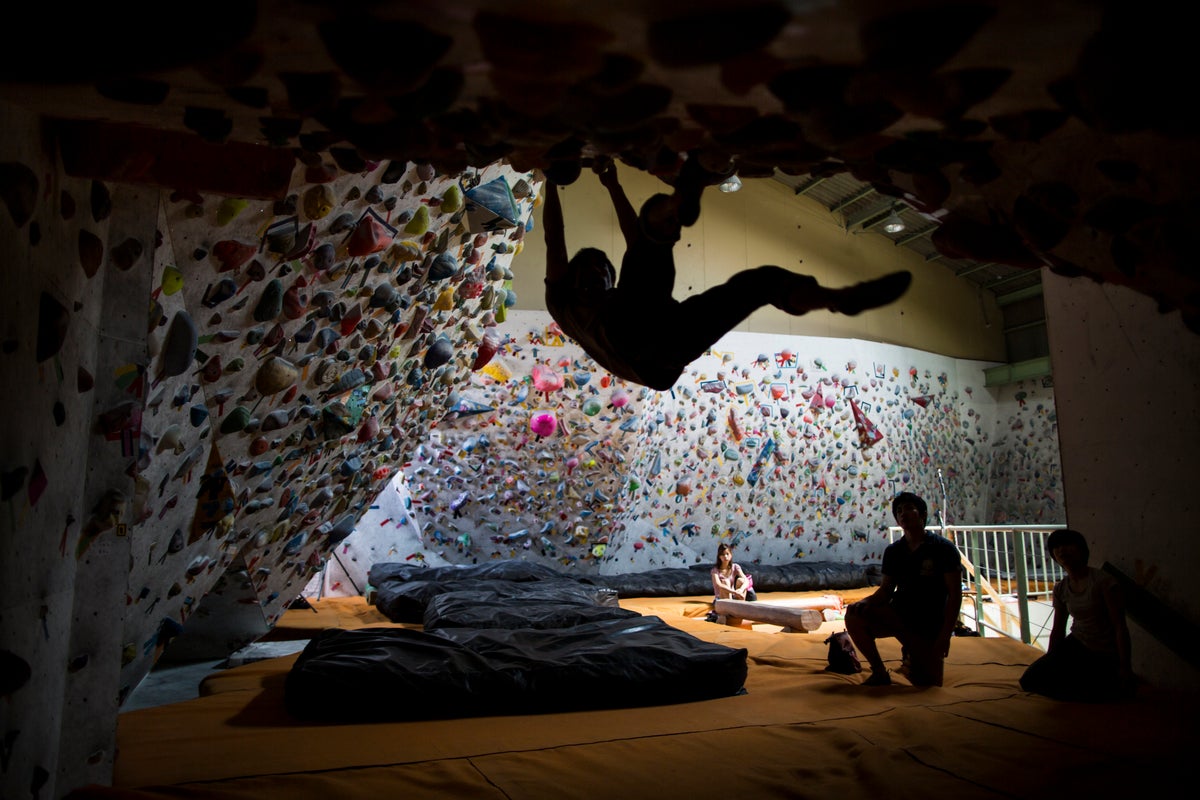

We all have a comfort zone, this warm, fuzzy little place in our minds we retreat to whenever we are challenged or afraid. For the first half of my climbing career, my comfort zone was bouldering. Growing up in Grand Junction, Colorado, I had access to some of the best boulders in the world. As I matured as a climber, though, something felt lacking in topping out problem after problem. I became stagnant and arrogant, justifying shortcomings by labeling anything that challenged me as lame or not “pure climbing.” I was an idiot.

That all changed when I met my two closest friends and training partners, Rob Pizem (aka Piz) and Mayan Smith-Gobat. Both are prolific roped climbers that tend to focus on big walls and traditional climbing, so my options became limited if I wanted to get outside with them. Piz and Mayan would drag me up walls, teaching me the finer points of “pitching out” and placing gear—all the while my nerves were on fire as my stomach clenched with fear. More often than I like to admit, I thought I was going to die—my comfort zone was trying to protect me from the unknown as well as perceived failure.

Those two quickly shattered my zone. We usually had goals of completing routes in a day, making the option for retreat unavailable. The first big wall I climbed was with Mayan on the Diamond in Rocky Mountain National Park—Hearts and Arrows (5.12b). I was proficient on 5.12, but it was completely out of my league. I sat petrified on small-cam anchors as the wind and ice-cold water ripped at my jacket. I stared at the ground just waiting for the gear to fail and send me plummeting to my death. I wasn’t able to lead a single pitch; Mayan had to drag me on toprope to the summit. However, there was a small sense of accomplishment and a spark of curiosity.

[Overcome your fear of falling with this course by Arno Ilgner]

My second wall was with Piz in the Black Canyon outside of Gunnison, Colorado. I led quite a few of the pitches—terrified but still on the sharp end. It was slow progress, but progress all the same. As I gained more experience on multi-pitch, single pitch, and walls, I pushed the boundaries of my comfort zone. I discovered that my fear was more manageable. I gained strength and confidence as I ventured farther above bolts or cam placements. Mental pieces that I was not aware of surfaced, and soon climbing became a game. The questions “What am I capable of?” and “How does this sequence go?” became my mantra, and with it, I achieved my goals.

But a comfort zone is a funny thing. Like your climbing ability itself, it’s dynamic. Climbing The Place of Happiness (5.12d, 18 pitches) in Brazil brought to light that if you are truly challenging yourself, you will always be outside your comfort zone. Place of Happiness crushed me on the first attempt. Unable to manage my fear due to 30- to 60-foot distances between bolts on small, friable granite holds, I felt paralyzed. My mental game fell apart, and I was back to being that scared little boy on the Diamond. However, even though I was frightened, I managed to pull it together for the second attempt and climbed my pitches until Mayan and I were weathered out 180 feet from the top and had to bail. Pushing myself in these situations created exponential growth in both my personal and climbing life. When your comfort zone is expanded and challenged, you become more curious, more adventurous, more dynamic—a better climber.

How to Expand Your Comfort Zone

1. Ask better questions

This was tough for me to learn, but when met with failure, many climbers ask “Why can’t I climb this?” I am guilty of it, but as I developed, I learned that it is not a why can’t I, but a how can I. With this subtle shift, there become definable terms that can be improved upon in sequences and step—which inevitably will lead to some level of success.

2. Eliminate “failure”

Climbers are too often focused on the negatives—shortcomings in strength, power, endurance, etc. When we fail on a climb, we chastise ourselves. Here’s a secret: No one cares! So neither should you! If you learn from mistakes and maintain a positive attitude, there is no failure. Not achieving a goal isn’t failing. It’s just a baseline for trying again.

3. Think less, do more

Most fears that keep us from learning or trying are centered in our imagination. We think more than we act. Calculating risk and reward is a good trait as long as a balance is found by putting those calculations to use. Make a move or nothing ever gets done. Even if all that gets done is moving on from a project or bailing on a route, you’ve done something.

4. Embrace community

No man is an island. Climbing is social; we develop relationships with friends and partners that help us grow. A community can help create a connection and reach breakthroughs. Support and encouragement can help expand comfort zones into trying new things (even if you don’t achieve your goal that particular time).

5. How bad do you want it?

When I first started training with Piz, we would start at 4:30 a.m. After eight weeks of this, I felt a drop in motivation. When the alarm sounded, I’d debate between sleep and train. Each time I asked myself, “How bad do I want it?” Every time I’d get up and go meet Piz. Those words have pushed me completely out of my comfort zone.

Also Read

- Ordeal By Alps With Allen Steck, Father of American Climbing

- Why Did Eddie Bauer Lay Off Its Whole Team of Professional Athletes? It’s Complicated.

- Was I Wrong To Call For a Rescue?

The post Five Tips for Expanding Your Comfort Zone appeared first on Climbing.

]]>