Find more balance and improve your movement

The post Climbing Training Drills for “The Fighter” appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

In my story about “the Dancer” and “the Fighter,” I break down the mindset and approach differences between two types of climber. To help each archetype find more balance, I developed some drills to help different climber types grow and improve. These drills for “the Fighter” require enough practice within a short amount of time that the ego can be re-trained. This of course requires practice spread out over years so that the training is remembered, internalized, and regularly utilized.

You can do these drills at the crag, at the gym, or ideally at both. Both settings will yield different results. I would recommend making these drills a core portion of one to two climbing days per week for one to three months. Then, depending on the complexity of the drill, incorporate them into a warm up or a cool down for at least one full day per month for the next six months. Finally, incorporate at your discretion. These drills will never not be helpful to practice.

Fighter Drill 1: No Send Sunday

Purpose: To help Fighters dance.

We are going to avoid the traps of flash-pumps and sloppy climbing with this simple drill.

The Drill:

Pick a specific day when you take and hang at the first bolt of every single route on every single try. Simply eliminate the ability to send so that the fight is less likely to enter your system.

If you eliminate the ability to send, you become more likely to work on the moves at any point on the route. When you make moves that are not quite optimized (dynamic when they could be static with better lower body positioning, or stiff when they could be more fluid), take and hang, and explore other options.

You’ve already un-sent the route by bolt one, so there is no reason to put up a fight now. Repeat this question to yourself:

Where can I learn to dance on the route instead of fighting through it?

Pro tip: Find a supportive partner for these practice days. Surprise! That might not be your boyfriend or girlfriend.

A drill for Fighters who are starting to dance

I call this one the “Second-Go-Balancing-Act.”

Purpose: To help Fighters find the balance.

Planning: This drill encompasses both techniques and, in my personal opinion, is the benchmark of a talented climber. If a climber can send something very hard on the second go (or potentially the third), it demonstrates their ability to combine high effort and high precision in a relatively short amount of time.

Many pro climbers are incredible at this, especially if they have competition experience. They have this special (and by special, I mean they have spent loads of time training it) ability in which they gather so much beta on their first try that they can turn on a readily available amount of try-hard to send on their second go. While this requires serious effort, it also necessitates incredible focus and beta-finding. And it entails memorizing skills, climbing tactics, and a controlled ego.

Practice:

Pick a climb that is higher than your onsight or flash grade, but lower than your redpoint grade. If you have redpointed 5.11c and onsight or flashed 5.10c, then a 5.10d or 5.11a is perfect for this.

On your first go, do not spend all of your energy achieving perfection on every move. Also: Don’t try to onsight the route. The goal is to spend as little energy as possible learning as many of the important moves as you can. Also, learn how and where to rest, and which sections require try-hard vs. slow and controlled precision.

During your first go, try to commit the moves to memory. Then return to the ground and spend some time rehearsing the moves before attempting a second go. This is the Dancer-heavy part of the drill.

Next, try to send. The second go is when you introduce the Fighter part of the drill. Mix the Dancer memorization with the Fighter try-hard and intuition. On this redpoint attempt, give a full effort, while keeping an open mind for beta that feels more intuitive.

To retain the Dancer memory while fighting, you need to stay in the present. Do your best to think about only the moves directly in front of you. If you find your mind straying to “those hard moves before the anchor,” then you might forget your beta in the middle of the route and have to try harder than necessary. This could lead to falling by the time you reach “those hard moves by the anchor” (i.e., a self-fulfilling prophecy). I know I’m at risk of being a broken record, but breathwork is a fantastic way to stay present and limit your try-hard when you don’t need to activate it just yet.

Even if you do get so pumped that you can’t climb for the rest of the day, remember: This is still a goal-oriented session, so not sending is okay and productive.

Each attempt is a learning experience, and at the end of the day, it’s all money in the bank. Often, a route of that grade would take someone four tries to send normally. This is a practice in condensing four attempts of unfocused effort into two fully focused attempts.

Explore more about the Dancer, the Fighter, and Ego Grade.

The post Climbing Training Drills for “The Fighter” appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Become a more balanced climber by understanding which climber type defines you, your Ego Grade, and what lies on the other side.

The post What Type of Climber Are You: A Dancer or a Fighter? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

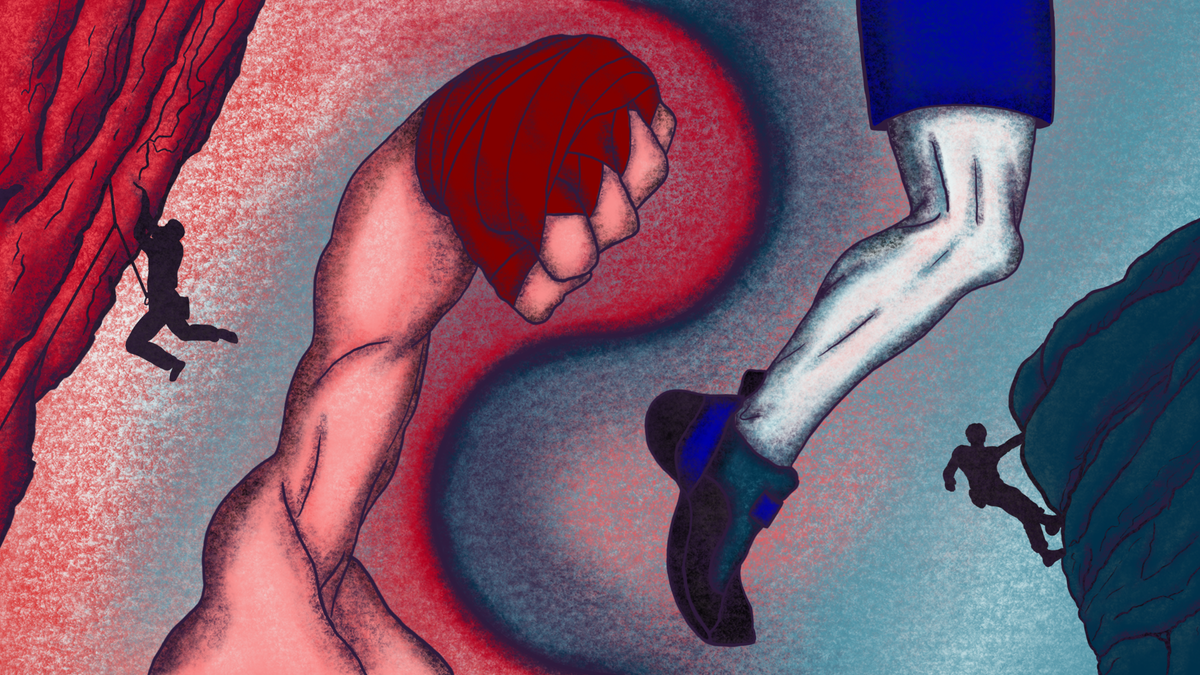

I have an issue with a particular grade in climbing. It’s not the hardest grade I climb, nor is it the easiest. The problem revolves around routes that I can do quickly, but are challenging enough to make me want to tick them on 8a.nu or Mountain Project.

I call this the “Ego Grade.” For me in sport climbing, that includes routes between 5.12a and 5.13a. On a climbing trip last year, I realized that my relationship with an Ego Grade was holding me back from becoming a better, happier climber. While my Ego Grade has different numbers in sport climbing, bouldering, trad climbing, and in the gym—they all stem from the same concept.

What’s an Ego Grade?

Simply put, an Ego Grade boosts your ego, or conversely, challenges your ego. It doesn’t necessarily contribute to your progression, and it may not even deepen your fulfillment from the sport.

Picture this: You walk into your local bouldering gym and at last, there is a fresh set on the wall. Before your shoes are even on, you lock onto the climb. It’s probably not the hardest problem you could try today, but it’s just hard enough for your ego to feast on. Honestly, how can a session feel satisfying if you don’t send one V“X”? Your ego eats it up like a fresh juicy burger from the Lander Bar after a long weekend in the Winds.

But the real question is: How many times do you need to do this before your ego is “full”? How many V”X”s of that style do you need to tick before you’re comfortable working your anti-style?

You might be unaware that your ego needs validation every time you climb. If this is true, you are not alone. Reworking this emotionally triggered mentality may bring more growth and satisfaction to your climbing.

Recognizing that you often partake in ego climbing and its performative satisfaction is no easy feat.

I struggled with my own Ego Grade for quite some time. My chest would puff up every time I climbed that idealistic, beautiful 5.13a grade. This mindset shaped my outdoor sport climbing for the better part of five years. Admittedly, there are silver linings: I got very good at sending my Ego Grade quickly. It helped me send stacked 5.12 multi-pitch climbs and get lots of volume on climbing trips.

Even with these successes, I truly believe prioritizing my Ego Grade has stunted my ability to progress to higher grades. Even worse, I became mentally uncomfortable struggling on almost any climb below 5.13. This robbed me of a significant amount of enjoyment I would have otherwise taken from the sport. At the end of the day, I still have so much to learn from climbs at a variety of grades.

Watch Casey Elliott climb past his Ego Grade as he explains the Dancer vs. Fighter binary

The Fighter and the Dancer

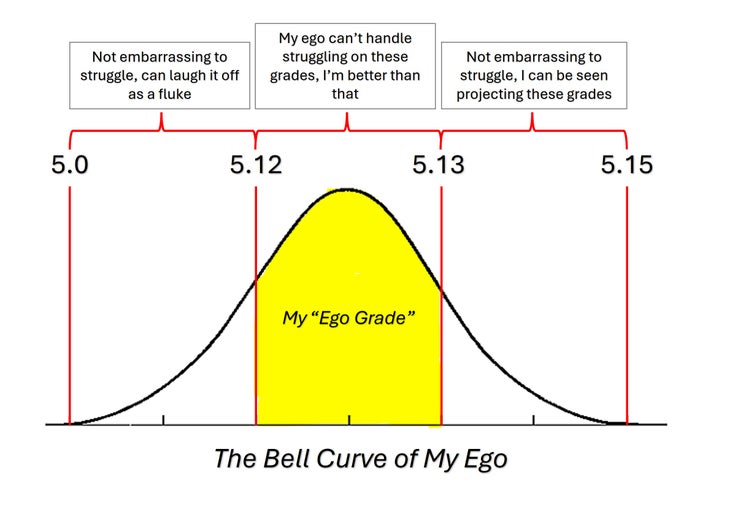

My friend Nicki is one of the most composed climbers I’ve ever seen—no grunts, no screams, not even a power peep. When we climb together, we feel the stark differences in our style. When I went for an onsight, I gave it my all every time, sometimes kicking and screaming. Nicki, on the other hand, had a habit that baffled me: While onsighting routes within her Ego Grade, she would often just … take.

It drove me nuts. “Why would you do that?” I’d ask. “You could’ve powered through and sent it. Then we could’ve moved on!” For years, I have been trying, mostly in jest, to coach her on how to try hard while onsighting. I assumed the reason she called “take” so often revolved around a fear of falling. It turned out I was completely wrong.

Nicki wasn’t afraid of falling, nor was she getting too pumped to continue climbing. What Nicki truly disliked was climbing through moves that felt unsure, awkward, or imprecise. She was a perfectionist. As a result, she eventually executed hard routes with grace and a deep understanding of the best movement. This type of approach requires time and does not lend itself to high-level onsighting. Her record shows that while she is more than capable of onsighting climbs closer to her redpoint grade, she often opts to sacrifice the onsight and work out the moves so she can climb it smoothly and confidently on a subsequent go.

In Nicki’s words: I know I’m physically capable of holding on longer and flailing my way up a harder route. While I can appreciate the sense of accomplishment that comes from sending something that way, it often feels at odds with how I approach most things in life. I prefer to act methodically and with precision, relying on preparation and a sense of predictability. Venturing into the unknown, both in climbing and in life, feels inherently challenging to me.

After our latest climbing trip together, we finally figured out how and why our approaches are so different.

The Fighter Mentality

On one end of the spectrum, there’s me, screaming through off-balance moves, pumped out of my mind, often successfully onsighting like an off-brand Sharma. I feel like I should send that grade quickly. So I send, regardless of how poor my movement is, because clipping chains justifies the effort. I call this the Fighter Mentality.

Fight·er Men·tal·i·ty:

Noun: 75% try hard, 25% technique, likely to run out of quickdraws while climbing

Signs that you might be a Fighter include:

- You skip anti-style routes because you can’t visualize the beta quickly enough.

- Your onsight/flash grade is very close to your project/redpoint grade (5.12c flash and 5.12d redpoint, for example).

- You often send in a way that you don’t think you could repeat, or “black out” and have no idea what you did.

- You struggle with or don’t spend time memorizing beta.

- You are embarrassed if you can’t figure out the moves quickly.

- There is a large gap between your style grades (e.g., V7 steep compression, but only V4 vertical crimping).

- You give it 110% every time you get on a rope or a boulder problem, often sacrificing learning opportunities and putting yourself at risk for injury.

The Dancer Mentality

In sharp contrast to my Fighter tendencies, there’s Nicki. She rehearses every move, even if she looks totally in control. Onsight-averse, she usually repeats a route several times. Eventually, she climbs like a dancer performing a beautifully choreographed piece. She loves the feeling of climbing immaculately. So if there’s uncertainty in her beta, she won’t try nearly as hard, because imperfect execution may not yield the same level of satisfaction or achievement. I call this Dancer Mentality.

Danc·er Men·tal·i·ty:

Noun: 25% try hard, 75% technique, likely knows the route length and puts the exact number of quickdraws on the appropriate side of their harness.

Signs you might be a Dancer:

- You take your time to dial in routes so that by the time you send, it feels like muscle memory.

- It takes multiple attempts or sessions to send routes even below your redpoint grade.

- Your onsight grade and redpoint grade are very far apart (5.11b and 5.13a, for example).

- You don’t want others (or yourself) to see you climb with sloppy beta.

- It is difficult to give maximum effort, even on a “send go.”

- You don’t fall often and opt to take if you feel uncertain about a move.

Finding the balance

Ideally, you have a combination of the Fighter and the Dancer within you. For Nicki and I, that wasn’t the case. We were too far on the ends of this spectrum. Ultimately, we were serving our egos more than our growth.

While being a Fighter or a Dancer has benefits, you are likely missing out on becoming a more well-rounded climber.

What the Fighter is missing

The Fighter avoids learning opportunities on Ego Grades and loses the chance to refine their movement skills. They skip anti-style routes because their ego can’t handle projecting a lower grade they “should” flash. The Fighter relies heavily on intuition and can easily access near-maximal try-hard.

Their true potential, however, might lie beyond these tendencies. If they embraced precision and took more time to learn movements that are not intuitive, they could likely climb harder and more efficiently. Ultimately, they could become a more well-rounded climber.

What the Dancer is missing

The Dancer avoids discomfort and only sends when everything feels just right. This approach often leads to more refined ascents, resulting in a deep understanding of projecting tactics and skills. However, it often means slower progress and longer redpoint timelines. The Dancer may struggle to give 110% when a performance has not been perfected. It is important to remember that trying hard is a muscle. Just like hangboarding, you have to train it to effectively activate it.

The sweet spot between the Dancer and Fighter

As with most things, the ideal lies somewhere in the middle. A well-rounded climber can quiet the ego, accept imperfection, and approach every grade as a learning opportunity. They can try hard when it counts and embrace messy climbing to get the send, while also appreciating the value in rehearsing new movements and exploring different techniques. Over time, this balance will unlock the potential to send higher grades and increase efficient climbing at lower grades.

What does a balanced climber look like?

I have a simple rule of thumb that indicates a balanced climber: Their onsight grade is approximately one number grade below their redpoint grade, and their flash grade is about one letter grade above that.

- For example, people who project 5.12a can often climb 5.11a first try, and probably 5.11b on a good day with good beta.

- A 5.14b climber has likely practiced onsighting to the point that they can do 5.13a or 5.13b with the right beta spray, and maybe even 5.13b or 5.13c in the first few tries.

- Even Adam Ondra fits relatively well into the rule— he has redpointed a 5.15d, onsighted 5.14+, and flashed 5.15a.

By this definition, I am not a well-balanced climber. I attribute that to spending too much time and mental energy on my Ego Grade. Last year, my max redpoint grade was 5.13b, my max flash grade was 5.13a/b, and my max onsight grade was 5.13a. I had climbed around 50 5.13- routes … talk about a flat pyramid!

This was a case of an overindulgence in the Fighter mentality. Once I had tried a route five to 10 times, I lost interest. Often, I couldn’t make the hard or uncomfortable moves feel doable quickly enough. Maybe to soothe my ego, I told myself that the route wasn’t worth my time. Perhaps low-hanging fruit within my style enticed me.

Ultimately, I discovered this was a deficiency I wanted to work on, so I put it to the test on a 5.13c called Pumped Puppets at Donner Pass, California. Rather than visualizing sending the route within five to 10 tries in an epic fight, I tried my best to be a Dancer and embrace a learning-focused long-term approach. I told myself there was always another day, and I didn’t want to send it if it felt like a fight.

My mantra became: Stoicism over hedonism. I delayed the gratification of a perfect send, foregoing the quick hit of sending fast and loose.

I wanted it to feel perfect, precise, and stripped of the Fighter try-hard. I believed that the only way I could convince myself that 5.14 is in my wheelhouse (the lifelong goal) was to climb 5.13c without having to fight for it.

In the end, I danced on the day I sent, and had plenty of gas left in the tank. I glimpsed into the future of climbing even harder routes. The battle was not won in a day, however. I constantly have to calm my ego to become more of a Dancer. It has been a beautiful process, and I have started to regain some of my love for climbing through removing my attachment to the ego grades.

For all of us, the real questions become: When is it important to use whatever it takes to try as hard as possible? When is it important to adopt a learner mindset? How do you access and toggle between these two mindsets? And how do you train both muscles?

How Dancers and Fighters can coach their egos

Two avenues exist when it comes to coaching a climber to balance the quick send with the precision send.

For both the Fighter and the Dancer, this will likely take some head game and ego work. Some of the work will overlap for the two approaches, while some will differ.

A commonality in working through both the Fighter and the Dancer mindsets is coming to terms with this:

Nobody really cares about your climbing.

You are most likely not a professional. This is not your net worth. There is always someone better than you. And people don’t judge you nearly as much as you judge yourself. So to retrain your ego, go make a fool of yourself! Get into the gym and make a silly try-hard noise. Jump at a hold and fall on your butt. Be goofy. And most importantly, teach your internal critic to be more compassionate.

Coaching the ego of the Dancer

The Dancer should focus on the idea that it is okay for people to watch you climb sloppily. During your next gym session, pick a route and either decide on the beta from the ground, or go in blind and embrace whatever happens. Do your best to execute the beta you set out for yourself, even if you hesitate and feel uncomfortable.

An even easier practice? Climb only until you fall, then come down. Cement the idea that you only get one attempt. Finally, climb on the anti-ego grade or anti-style climbs. If you love 5.12c or V7 vertical tech, work on 5.11 or V4 steep compression boulders.

Coaching the ego of the Fighter

The Fighter should go to the gym and be silent. No power screams, no jumping for holds, no pushing through fear or discomfort. Your goal is to stop whenever something feels awkward or uncomfortable. I would recommend toproping or climbing lowball boulders to dissuade poor climbing due to fear of falling.

Finally, climb on the anti-ego grade or anti-style climbs. If you like 5.12c steep jug hauls, hop on 5.11c vertical tech that makes you feel like an uncoordinated gorilla. Finally, take take take until you can dance your way up a climb.

Training drills for Dancers and Fighters

As you get your ego under control, there are also some exercises you can do at the crag to practice projecting, onsighting, and flashing climbs.

Similar to training, if you cut out parts of your plan because you don’t feel like doing them, you will progress more slowly. If you show up to the crag with a plan to onsight five routes, but only try one and decide to work your project instead, you won’t get better at onsighting. If you plan to project a route, but get distracted by a different climb closer to your flash grade, you won’t get better at projecting.

Once again, we need to find the balance. Here are two sets of drills to help you do that:

Get the Fighter Training Drills

Get the Dancer Training Drills

Final Thoughts

Whether you’re a Fighter clawing through every move or a Dancer perfecting every detail, your relationship with your Ego Grade shapes far more than just your tick list—it shapes your growth.

I wrote this advice through the lens of sport climbing because it easily accentuates these differences. The tactics and mindsets of sport climbing—stretched over dozens of moves—lend themselves to large observations. However, these same tendencies exist in bouldering, trad climbing, ice climbing, competition climbing, and interestingly enough, general life. Have you ever watched someone rapid-fire a boulder problem 30 times in 30 minutes with the same beta, then someone else send because they rested between go’s and tried a variety of beta? Have you ever observed fear accentuating these mentalities in trad climbing? (This is basically the entire premise of “headpointing.”) What do the egos of successful competition climbers have in common?

By identifying your default tendencies and deliberately exploring the opposite end of the spectrum, you begin to unlock new dimensions of learning, progression, and joy in climbing.

Remember: The real progress often begins when the send doesn’t matter as much as how you send. If you can toggle between trying hard and refining movement, between effort and elegance, you’ll not only climb harder, but you’ll climb better. And maybe, just maybe, you’ll discover that your proudest ascents aren’t the ones that fed your ego, but the ones that challenged it.

Special thanks to Nicki for bravely exposing her ego and mindset, and for sharing a perspective I once struggled to see.

The post What Type of Climber Are You: A Dancer or a Fighter? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Find more balance and optimize your effort level

The post Climbing Training Drills for “The Dancer” appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

In my story about “the Dancer” and “the Fighter,” I break down the mindset and approach differences between two types of climber. To help each archetype find more balance, I developed some drills to help different climber types grow and improve. These drills for “the Dancer” require enough practice within a short amount of time that the ego can be re-trained. This of course requires practice spread out over years so that the training is remembered, internalized, and regularly utilized.

You can do these drills at the crag, at the gym, or ideally at both. Both settings will yield different results. I would recommend making these drills a core portion of one to two climbing days per week for one to three months. Then, depending on the complexity of the drill, incorporate them into a warm up or a cool down for at least one full day per month for the next six months. Finally, incorporate at your discretion. These drills will never not be helpful to practice.

Dancer Drill 1: Learning to try hard and communicate with intent

Purpose: To help Dancers fight.

Pick 10 new routes that you and your partner have never climbed. Each partner will attempt to flash five routes and onsight five routes over two climbing days. The goal is to practice letting go of perfection.

The Drill:

Day 1:

Your partner is the “onsighter” and you are the “flasher” (please don’t take this literally) for five new and different routes.

Your partner (the onsighter) will try to onsight a route with the goal of sending. Their secondary goal is to collect as much information for their partner, the flasher, as possible. They will try their absolute hardest, committing to not saying “take” on the attempt.

Once the onsighter is back on the ground, talk it out. Discuss where the hard moves are. Talk about the beta options and where the rests are. Eventually, you can figure out how much beta is useful, what type of beta works for you, and how much information feels like overload.

Also notice how you prefer to receive beta. Do you want the full spray-down on the ground? Or would you prefer a play-by-play as you are climbing?

Then you (the flasher) will try to flash the route, knowing that you only get to try that route once. If you fall, pull back up and rest for five to 10 minutes before trying again to flash the rest of the route. No hanging around to work beta or re-try moves.

Clean the draws and repeat this process on four more routes that day.

Day 2:

Reverse roles: Now you are the onsighter and your partner is the flasher for five new and different routes.

Repeat the steps for Day 1. Kind of like understanding your romantic partner’s love language, remember that your beta spray needs likely differ from your partner’s. Again, you will try as hard as you can to onsight the route with the intention of helping your partner flash the route afterward.

Day 3 (Extra Credit):

Eating ice cream isn’t usually part of any real workout, but I often recommend it after a well-executed training session. So, Day 3 is the chunky monkey of this drill.

On Day 3, return to any route that you did not send on Day 1 or 2.

- Before you climb, practice discussing the beta options again with your partner, using the combined insight from both of your attempts.

- The second-go attempt of the routes will still require some flash or onsight practice since you won’t remember all the beta, even if you think you might. Work on being patient and open-minded, and don’t be afraid to sprinkle in some good ol’ fighter try-hard when needed.

Pro tip: This is a fantastic thing to do on climbing trips where you don’t want to spend time projecting. You can explore a lot of new areas, get familiar with the style of a zone, tick off new routes, and learn something in the process. I did this all the time with the students at The Climbing Academy for the first few days in a new zone as a way to find which crags they liked and explore the area, but still be targeted with training.

A Drill for Dancers who are starting to fight

I call this one the “Second-Go-Balancing-Act.”

Purpose: To help Dancers find the balance.

Planning: This drill encompasses both techniques and, in my personal opinion, is the benchmark of a talented climber. If a climber can send something very hard on the second go (or potentially the third), it demonstrates their ability to combine high effort and high precision in a relatively short amount of time.

Many pro climbers are incredible at this, especially if they have competition experience. They have this special (and by special, I mean they have spent loads of time training it) ability in which they gather so much beta on their first try that they can turn on a readily available amount of try-hard to send on their second go. While this requires serious effort, it also necessitates incredible focus and beta-finding. And it entails memorizing skills, climbing tactics, and a controlled ego.

Practice:

Pick a climb that is higher than your onsight or flash grade, but lower than your redpoint grade. If you have redpointed 5.11c and onsight or flashed 5.10c, then a 5.10d or 5.11a is perfect for this.

On your first go, do not spend all of your energy achieving perfection on every move. Also: Don’t try to onsight the route. The goal is to spend as little energy as possible learning as many of the important moves as you can. Learn how and where to rest, and which sections require try-hard vs. slow and controlled precision.

During your first go, practice committing the moves to memory. Then return to the ground and spend some time rehearsing the moves before attempting a second go. This is the Dancer-heavy part of the drill.

Try to send. On the second go, introduce the Fighter part of the drill. Mix the Dancer memorization with the Fighter try-hard and intuition. During this redpoing attempt, give a full effort to sending the route while keeping an open mind for beta that might feel more intuitive.

Climb until you fall, rather than deciding it is time to take, or purposefully letting go. If—like Nicki determined—you aren’t actually afraid of falling, this should help Dancers practice feeling uncomfortable while trying hard.

If you find that you are scared to do the next move, then that prompts other drills that you could work on in tandem. As always, gauge the safety of where you are falling because that fear might be justified!

Even if you get so pumped that you can’t climb for the rest of the day, remember: This is still a goal-oriented session, so that is okay and productive.

Each attempt is a learning experience, and at the end of the day, it’s all money in the bank. Often, a route of that grade would take someone four tries to send normally, so this is a practice in condensing four attempts of unfocused effort into two fully focused attempts.

Explore more about the Dancer, the Fighter, and Ego Grades.

The post Climbing Training Drills for “The Dancer” appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Project Direct coaches take a statistical dive into the strength tests and surveys of 600 climbers and find some interesting results

The post Are Max Hangs All They Are Cracked Up To Be? What Metrics Really Matter? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Tl;dr: This analysis shows that weight, gender, height, and ape index do not play a significant role in a person’s maximum sport climbing grade or bouldering grade. The analysis shows the most important factor in getting better at outdoor rock climbing is going climbing outside (crazy!), followed by several varieties of finger strength and upper-body strength. However, if you were part of this survey, maybe lay off the hangboarding and get your butt outside. If you want to see how well the multivariate model fits you or read the unabridged version, head to Project Direct Coaching.

Why Do We Care About Statistical Analysis in Rock Climbing?

We are on the cusp of a new era in climbing. Historically, climbers have relied on testimonial training plans and the “secrets to success” endorsed by elite climbers. In this way, the climbing world is far behind other sports that use hard, quantifiable data to influence training plans, draft choices, player values, and more.

Let’s discuss Major League Baseball as a prime example. This sport has more quantifiable metrics than almost any other. Therefore, it has seen the use of statistics and multivariate analysis to evaluate players and the odds of success in the major leagues. One historical, statistics-driven change in baseball scouting was to recruit players by their “on-base-percentage” rather than using physiological attributes like speed and strength. Through this method, abstract attributes like mental toughness, intelligence, and patience can be assessed. The theory is that baseball players can develop speed, strength, and power much faster and more reliably than mental toughness or patience. This alternative scouting method worked with high reliability because it focused on the main aspect of the game: to win, a team must score more runs than the other team. In the end, stacking a team with players that have high batting averages doesn’t directly translate to scoring runs. The moral of the story is to scout or train the variables that actually correlate with winning (or in our case, sending) rather than metrics that may seem important at first but prove to have less value than others, like speed and strength.

So what does this baseball analogy have to do with changing eras in climbing? Let’s go back to the testimonial training theory. Up until recently, coaches and advice columns have focused on what elite climbers did to see success, which at the end of the day, is a very limited, specific data set of few. We could start a podcast and talk to all the strong climbers (which has been done) and then try to find the similarities between what has shown success for them and distill that down. Generally, the climbing community has had relatively good success with that. Without proper statistical analysis we cannot say for certain that the variables the community sees as important truly cause improvement, or are just correlated with improvement.

For example, if every climber from the dawn of sport climbing has said that having stronger fingers is the most important key to success, then everyone trains fingers heavily and sees improvement in their climbing grade, are we actually able to say that finger strength was their biggest key to improving? Could it be that these climbers also climbed more, learned movement skills, acquired redpoint tactics, got stronger upper bodies, started deadlifting, and ultimately could have climbed as hard without training fingers as much or even progressed faster if they focused on other attributes more? Is this socially accepted and universally trained attribute something that we all do or something that we all need to do? And if so, how much?

But times are changing. Companies like Project Direct Coaching, The Power Company Climbing, and Lattice Training are working to create more data-driven answers to these questions. This is where multivariate analysis comes into play. We can survey climbers and test quantifiable metrics, utilize dozens of variables even if they have statistical collinearity (ex: “maximum finger strength” and “maximum number of 7:3 repeaters in a set” will have some physiological overlap) and ask our analysis tool which of these variables demonstrate real influence on the output of climbing harder grades. We can then create a model that weighs the importance of each variable appropriately and outputs a predicted response. If the predicted response is fairly accurate, it means the variables that show importance are truly important.

In short, we could test a climber’s metrics and with a good model, we can predict how hard they “should” sport climb or boulder and what variables played key roles in that output. Pretty neat! And it’s something that other sports industries have been performing for years to evaluate how much to pay for players or how likely they are to succeed.

What Variables Did We Have At Our Fingertips?

In this analysis, we wanted to know what are the most important variables that contribute to a climber’s maximum sport climbing and bouldering grades. Or in other words, what are the most important things a person can work on to achieve one specific type of “success” in the sport? We can all have herculean finger strength (or a great batting average), but still not end up scoring runs or clipping chains.

To this end, we obtained a data set of over 600 climbers with a maximum grade ranging from 5.9 to 5.14+ and V1 to V15 that contained the following variables:

- age (yrs)

- weight (lbs)

- height (in)

- BMI

- wingspan (in)

- ape index (in)

- training experience (days)

- outdoor climbing experience (days)

- maximum # of pullups in a set

- amount of weight added to a max hang on a 20mm edge (lbs)

- amount of weight added to a max pullup (lbs)

- the previous two metrics in terms of strength to weight ratio (lbs/body weight in lbs)

- maximum # of pushups in one set

- max # of sets of 7s:3s repeater

- maximum # of pullups in one set

- maximum time on a short campus ladder (feet on, up one down one), and

- maximum time of a long campus ladder (feet on, up two down two

Does Any Single Variable Prove Anything? Also, What The Heck Is R2?

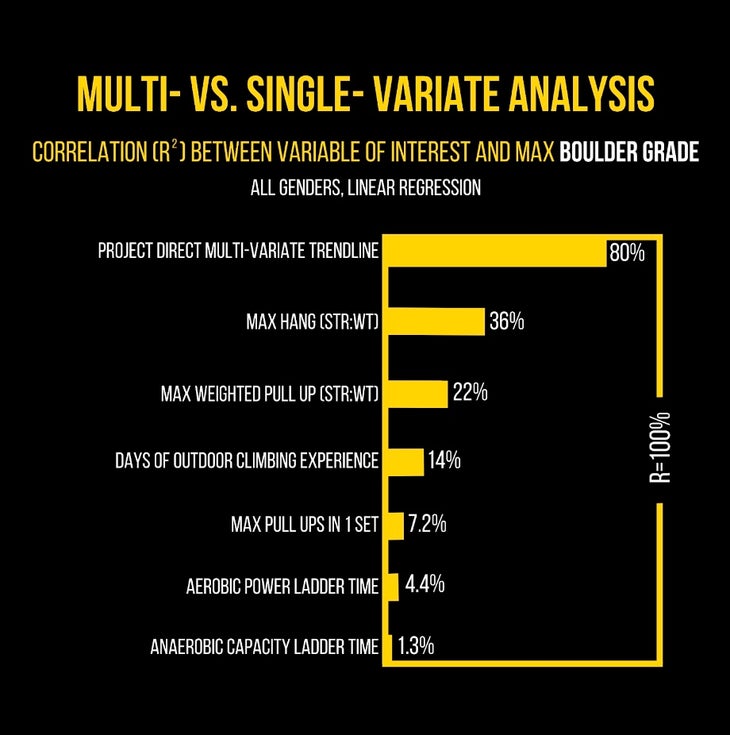

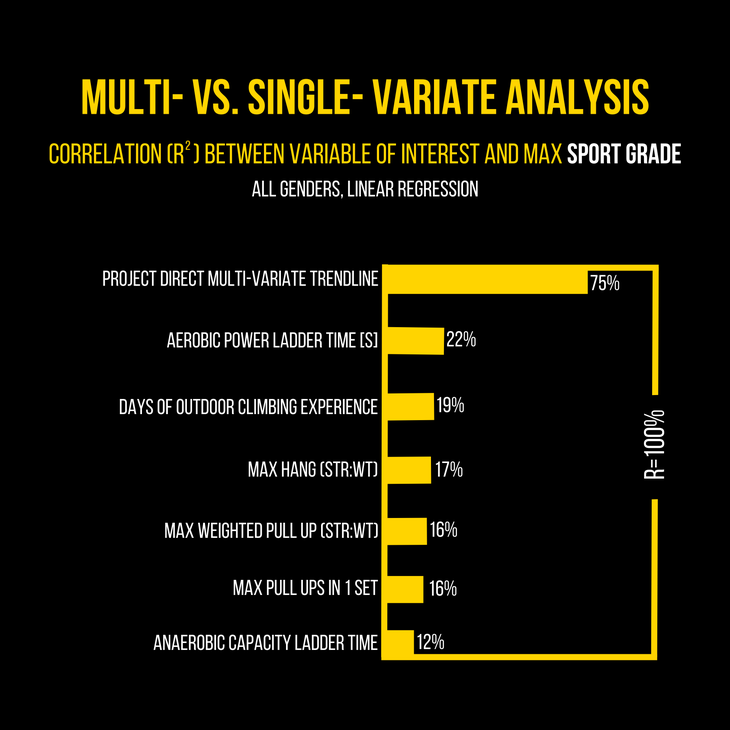

We started by performing single variable analysis to see if any variables had an independent and significant contribution to either maximum bouldering grade or sport climbing grade. We examined this data separately for men and women and did not find a significantly different result—less than 5 percent different! We also considered linear and non-linear correlation, and their relation to sport climbing and bouldering independently. No matter how we spun it, we never saw more than a 36 percent correlation between any single variable and climbing grade. And with how many variables there are, it would be impossible to even say that the 36 percent showed any real significance or if it was just coincidental.

Note: It is important to identify what correlation (or R2) values really mean. Correlation is not causation. Rather, an R2 of 0.40 indicates that 40% of the variance of the data can be attributed to the variable with this correlation. Looking at our data, the single variable models can explain a maximum of 22 percent or 36 percent of the variability in the outcome in sport climbing or bouldering, respectively. As the standard for “moderate positive relationship” sits at 30 percent, we can say that no single variable can get in the ballpark of predicting sport or bouldering grade. Especially when we look at how many variables we have, and how much they overlap (ex: max hang and repeater data both rely physiologically on finger strength to an extent). If we added up all the correlation values for all 15 variables, we would have higher than 100 percent which indicates that a good portion of those values are, without a doubt, only showing correlation.

Our Process Of Using Multivariate Analysis in Climbing

While single variable analysis gave some insight, we wanted to use all the variables at our disposal in a single model, just like the baseball analogy. To achieve this, we employed a partial least squares (a form of principal component or multivariate analysis) to see how much of an impact each of the following variables had on a climber’s reported maximum sport and bouldering grade when considered all together.

While all of these metrics must be generally quantifiable, some of them are physiologically-based and some are skill-based. An example of a physiologically-based metric is maximum finger strength. While it does take some coordination to perform the perfect hang, it takes a fraction of the skill than outdoor climbing requires and is easy to assign a value to it. The two variables in this set that show a higher relation with skill development are: “outdoor climbing experience,” and “training experience.” To quantify these, we estimated the number of days a person has climbed outside and the number of years they have spent training at least 4 months out of the year.

We performed the partial least squares regression on the set of climbers including all the independent variables bulleted above, and used maximum sport climbing grade and maximum bouldering grade as the dependent variables. We accounted for the collinearity between the variables and created an optimum set of factors that best fit the data set. Then, the multivariate analysis calculated three very important things:

- It showed which variables were statistically significant (when all variables are considered together) and which ones did not have a high enough correlation with the output to be deemed significant. This is useful for attaching meaning to the data and is the meat of what we will talk about.

- It assigned a weight to each variable for both sport and bouldering separately that allowed us to create models that can predict a climber’s theoretical maximum sport climbing or bouldering grade.

- It assigned an R2 value to the new, multivariate model which indicates what percentage of the variability in output can be explained by the model (or in other words, how well does the model predict the outcome).

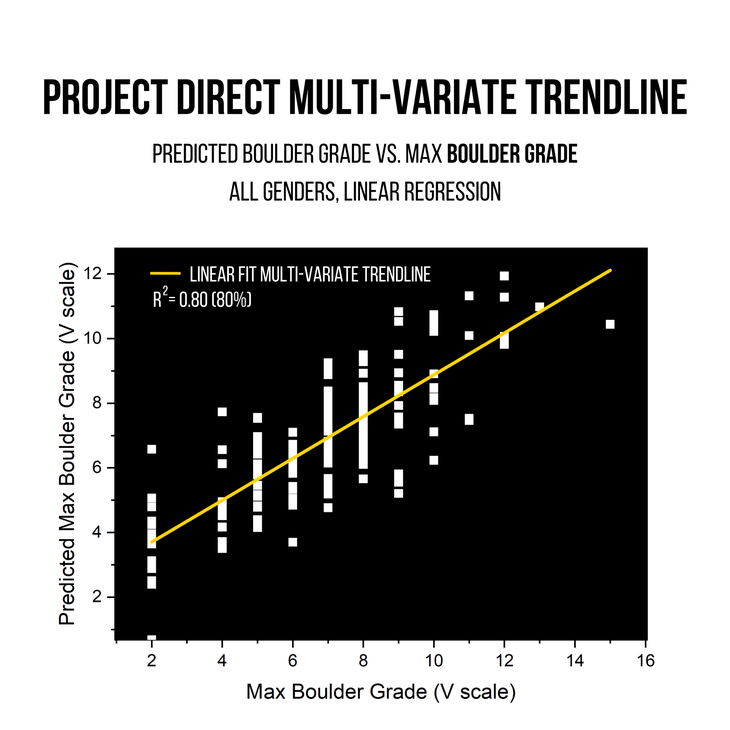

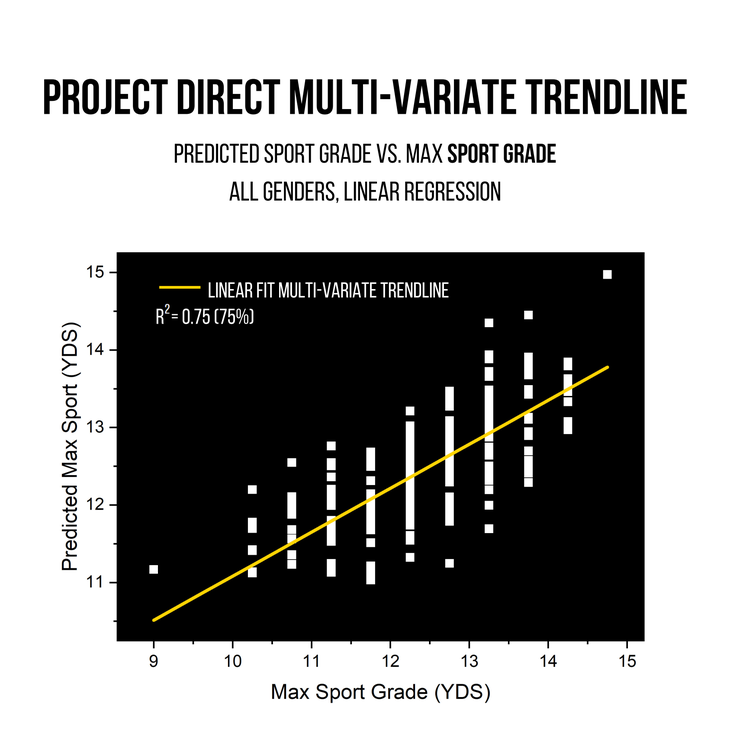

The Project Direct multivariate models show R2 values of 75 percent to 80 percent. This means the line or equation we calculated is four to eight times better at predicting maximum sport climbing and bouldering grade and tells us how strongly each variable is adding to that relationship, which is a massive improvement from single-variable analysis trendlines (the better the correlation, the more accurate the variable importance values are).

You could think of this as the ability to predict a climber’s maximum grade more frequently and with smaller error. However, with all this data, this line still only accounts for about 75 percent to 80 percent of the variability! That means about 25 percent to 30 percent of what makes a climber successful is still out there in the ether waiting to be captured, have the fun beaten out of it, and enumerated like a front range trail runner making us all feel bad on Strava. The darkest corners of the mysterious universe still remain! But some elucidation to this multivariate question has been gained, as was our goal.

The Results

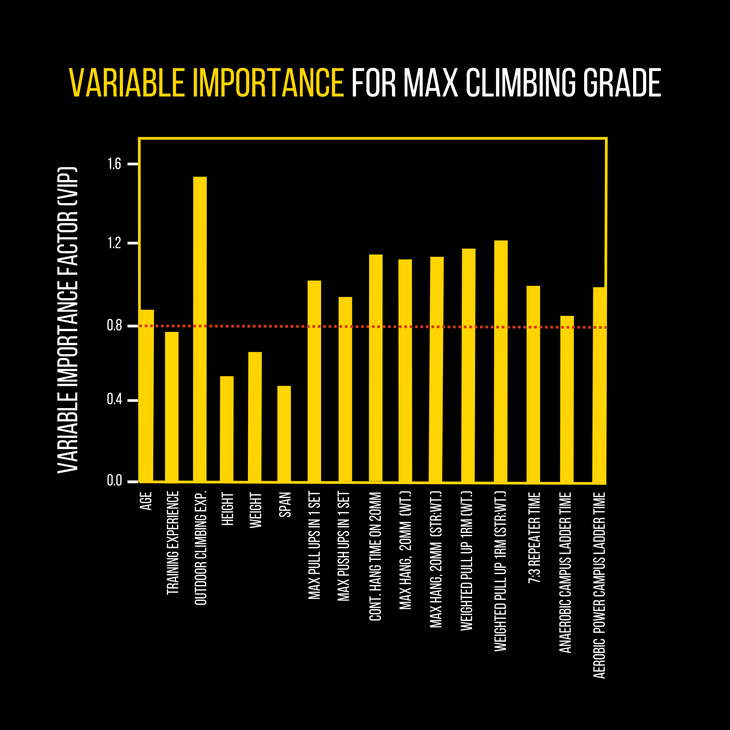

So what are the most important variables based on the regression? For the full spray, check out the graph and the bullet points below, as we have gone through each variable individually to talk about their significance and effect on maximum climbing grades! The variables that fall under the red-dashed line are not statistically significant and the variables that rise above the line influence the outputs (maximum grades climbed) in a statistically significant way.

Hopefully this can be the final word in every height and ape index debate. Here you have it folks! Height, gender, weight, wingspan, and ape index showed no significance in predicting sport climbing grade. How cool is that? We are terribly sorry to take away the topics everyone loves to complain about and sure, there are absolutely times where it pays to be taller or smaller or have longer arms, but in terms of a climber’s glass ceiling, their ape index isn’t playing a factor in shattering it.

- Gender – When we started this analysis, we found that gender did not show significance, so we removed it as a separator and considered all genders together in the data set shown above. It also allowed us to include participants who did not identify as male or female.

- Age – This variable proved to be significant. It showed a small, negative effect on the regression line meaning the older the climber is in this data set, the lower their maximum climbing grade. It is important to consider that age incorporates many unknowns that do not directly relate to physical acumen such as starting a family, work, available time, etc. Considering how important and positively correlated “outdoor climbing experience” was, this shouldn’t be considered a serious deterrent from climbers starting at an older age. Units are in years and ranged from 16 to 73 years old.

- Training experience – In some iterations of the analysis, training experience showed significance, however in the final iteration, it did not. Training experience is one of the variables I would consider to show a combination of skill and physical fitness as it implies a more serious dedication to climbing. Units are in years and ranged from 0 to 15+.

- Outdoor Climbing Experience – The MVP of VIPs! This showed the greatest significance in predicting a climber’s max bouldering and sport grade. WOW, groundbreaking (sort of)! While this has been stressed as important time and time again, it seems that people don’t fully believe it and want a “get strong quick” gym routine. But, here we have the data showing that there is no shortcut in the gym that can alleviate the need for time on the rock. Again, this is based on a single data set, but for the climbers surveyed, outdoor climbing was a more important variable than any finger strength or pulling strength metric. We could play devil’s advocate and say that nobody in this data set knew what they were doing, and took a very long and arduous approach to getting better at climbing. That would indicate this regression line shows the most important variables to get better slowly. Or, we could assume these people were incredibly dialed, knew the shortcuts to success, and this analysis is pure gold. We would love to do this analysis on World cup climbers, or professional climbers and see what variables change. Shit, even just give us the three Alexs and between them we probably have a decent chance of seeing some changes in the variables. In reality, there are surely people in this data set who are mega dialed, and people who are not, giving this data set a decent chance at being highly representative for the vast majority of climbers reading this. Units are in days and ranged from 0 to 3,750 days. We multiplied the number of years a person has been climbing consistently by the number of weeks they climb outside and the average days per week that they climb outside.

- Height – Simple. Not significant. Units are in inches and ranged from 57 to 77.

- Weight – Not significant! NICE! This actually showed up in an intriguing fashion. It is the principle reason that the variables “maximum weight added to a pullup” and “maximum weight added to a pullup in terms of strength to weight ratio” influenced the data in virtually the same way. Sidenote: This variable did not follow a normal distribution*. When we calculated the BMI statistics for the surveyed climbers we found the minimum BMI in the study was 10, and the maximum was 41. The average BMI was 22.6 with a standard deviation from that average of 2.59 (giving a range from 20 to 25 for the vast majority of the survey). Seeing as the healthy range given by the CDC for BMI is 18.5 to 24.9, the majority of climbers in this study were in the healthy BMI range. As a disclaimer, weight might be significant if we included every person in America, but if you are moderately close to the healthy BMI range, it doesn’t statistically matter how much you weigh. For example, if you are 5’8”, this says that you can range from about 120 to 170 lbs and still fit into the healthy BMI range. That’s quite the range. When we got into climbing, we were told it was easier to get 5 lbs lighter than 5 lbs stronger. Looking back, we feel like we were partially robbed of the opportunity to get stronger in the long run because once you regain the weight, you are back to where you started. In contrast, after you stop training strength, it sticks around. Hopefully this means we can drop the weight part of the conversation off the table for the most part. Tight tight, we love that. I say “for the most part” because we do not have enough data on climbers above 5.14+ and v13, and we are unable to draw conclusions about the ultra elite. Units are in pounds and ranged from 72 to 288.

- Wing Span – Not significant. We also previously analyzed ape index, and it also showed no significance. Units are in inches and ranged from 58 to 81.

- Maximum Pull Ups in 1 set – A metric that matters. This has shown a positive effect on climbing grade. People that could do more pull ups in this data set could climb harder. Units are the quantity of pull ups a climber could do in a single set and ranged from 0 to 68.

- Maximum Push ups 1 set – A metric that mattered. Funny enough though, this metric showed a negative influence on maximum climbing grade. That means people in this data set who could do a lot of pushups didn’t climb as hard as those who couldn’t. This is the fun thing about experimental data like this, it shows what “is” and/or not always what we expect. We think it’s a great idea to focus on opposition to stay healthy and even increase your compression skills. We wonder if a lot of people in this data set do crossfit more than they climb? Units are the quantity of pushups a climber could do in a single set and ranged from 0 to 90 (okay, there was one person who said 388 but I don’t believe it).

- Continuous hang – Another finger metric, mostly related to finger endurance. This showed a significant and positive influence on climbing grade. This is measured by timing how long you can hang on a 20mm edge at body weight without taking a break. Units are in seconds and ranged from 0 to 120.

- 20-mm Max Hang (total pounds added) and 20-mm Max hang (strength:weight ratio) – Now to the meaty, juicy stuff that everyone loves. This is a finger strength metric and is measured by testing how much weight you can add to your body while hanging on a 20mm edge for 7 to 10 seconds. This showed a significant and…. negative correlation to climbing grade! What? Okay, we all know stronger fingers mean climbing harder, but why is the data showing this as a negative factor? Our best conclusion is the same as with the push ups—too many people in this data set trained finger strength and did not spend enough time actually climbing outside. They have stronger fingers than what the regression line says they “should’ be climbing. As coaches of over 200 athletes, what we have seen is that raw finger strength is stressed too much in comparison to skill building, especially when it comes to sport climbing. Due to the non-significance of weight as discussed earlier, these two metrics showed a similar effect on the data. The collinearity between these two variables shows that the amount stronger we get is as good of an indicator as strength to weight ratio. Units are in pounds added or pounds added plus body weight divided by body weight and ranged from 0 to 200 or 1 to 2.08.

- Max Weighted Pull Up (total pounds added) and Max Weighted Pull Up (strength:weight ratio) – This is an upper body strength metric, and is found by testing how much weight you can add to a single pull up. This metric showed a significant and positive relationship with climbing grade! This was actually the second most important variable in the entire set. While this could mean that weighted pull ups are incredibly important and the secret key to success, it could also mean the climbers in this survey trained weighted pull ups the proper amount in comparison to how much they climbed outside or found success climbing outside. This metric showed a huge importance on bouldering grade and less importance (but still positive and significant) for sport climbing grade. Again, relating this to weight did not show much of a change in the variable effect on grade. Units are in pounds added or pounds added plus body weight divided by body weight and ranged from 0 to 175 or 1 to 2.03.

- Repeaters – Significant and positive. This is calculated by timing how many sets of 7 seconds on, 3 seconds off repeaters on a 20mm edge a climber could do in a row without stopping. This is a good metric of finger endurance. Units are in seconds and include the 3 seconds of resting between each 7 second hang and ranged from 0 to 480.

- Anaerobic Capacity ladders – Significant and slightly negative. This test is done by using a campus board. With feet on, move up two rungs on the ladder with one hand, match, then return to the starting position with one hand, match, and repeat until failure. This metric is more difficult to test reliability across many climbers and gym set ups. We do question the validity of the repeatability and accuracy of this variable and the aerobic power ladder (below) due in part to the variety of foot holds options and campus ladder edge sizes. Units are in total seconds and ranged from 0 to 260.

- Aerobic Power Ladder – Significant and positive. This test is the same as the last, except moves are made one rung at a time. This metric is more difficult to test reliability across many climbers and gym set ups. We do question the validity of the repeatability and accuracy of this variable and the anaerobic power ladder (above). Measured in total seconds and ranged from 0 to 730.

What Can We Conclude From All these Numbers? (Other than you should have paid better attention in stats class?)

We are psyched about the results because it reaffirms that as a climber, if you want to get better at climbing outside, going climbing outside is the most valuable part of the process! It also shows that anyone, regardless of height, gender, wingspan and weight (healthy BMI) can achieve high climbing grades with enough skill building and strength training. Our basic and unchangeable attributes do not hold us back, statistically.

If you aren’t able to climb outside, the next best thing is to climb inside but in a skills-based fashion that best resembles outdoor climbing. That means climbing outdoor style boulders or roped climbs (Moonboard, baby!) with some level of feedback. Doing this in tandem with focusing on as many of the important variables that apply to your discipline and season as possible. What does climbing with feedback look like? This could be self-assessing your climbing videos, watching YouTube videos of many beta options, climbing with stronger or more experienced climbers who are helpful, getting coaching from professionals, etc…

This analysis also promotes the idea that skill-based workouts which incorporate some level of finger training will hit several of the important variables at once (without sacrificing skill building for strength gains). This is something that has been prevalent in the history of climbing, and has resurfaced more and more recently. It’s a breakthrough to finally see it in a non-testimonial way, expressed through statistical analysis and testing.

All of this will promote growth faster than the typical 2-hour gym session where you hang out and eventually try a hard boulder a few times. On a side note, having fun is the key to not burning out, and we wish there was a metric for that in here!

These results can also help put an end to the constant complaining about team kids flashing your project. Now that we know that variables like weight or height are not significant in the long run, I would daresay that one of the main reasons youth team kids get better quickly is because they climb in a structured way, with a coach giving them feedback, and have little open-minded sponge brains.

If there are two conclusions we can leave you with to increase your outdoor climbing grade, it is to maximize improvement in the significant variables discussed above and prioritize time on rock. Two great avenues for this is to have a coaching mindset and seek out on-the-wall training ideas. That could mean being a self-taught student or hiring a coach, both are great! There are many insightful, free resources as well as paid skills coaching and on-the-wall training from a variety of incredibly talented coaches. At Project Direct Coaching, we have and will continue to focus on skill development, on-the-wall workouts, and data-driven analysis in all of our plans.

We want to give a thank you to Power Company Climbing for taking the time and energy to collect this data and for working with us to get to the bottom of it. If you want to see how well the regression model fits you, or read the full story in all its nerdy detail, head to www.projectdirectcoaching.com/climbingpredictor and input all the variables above.

***

Casey Elliott is currently pursuing a MS in Materials Science and Engineering in Reno and has worked in the climbing industry for almost 10 years. His psych for exploring the outdoors through climbing and skiing is only matched by his love of sharing that with others. He coaches for Project Direct Coaching.

Karly Rager is an engineering career drop-out and the founder and head coach of Project Direct Coaching. She loves climbing, traveling, and is stoked to belay anyone who wants to try hard.

Also Read

- Lattice Training’s Guide to Better Hangboarding: Part 1

- Are Most Climbers Getting Fingerboard Training Wrong? (Part 1)

- The Training Bible: A Complete Full Year Program. Phase 1: Conditioning

The post Are Max Hangs All They Are Cracked Up To Be? What Metrics Really Matter? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>