Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

The ability to properly tie climbing knots is an essential skill that every climber, regardless of experience or ability, should not only learn, but master. There are hundreds of types of knots you can use for climbing, so taking the step to learn them can be daunting. Still, don’t tie yourself in knots with worry. When I started climbing in 1973, climbers used four basic knots: the Double Bowline, Ring Bend, Prusik, and Clove Hitch. Those four got me by for over a decade. Of course, since those early climbing days, climbing and climbing knots have evolved to better meet climbing’s demands.

Entire books have been written on knots. My favorite, The Ashley Book of Knots, covers nearly 4,000 knot—it’s a veritable encyclopedia, with 7,000 hand-drawn illustrations. But you can get started with eight basics: figure-8 (aka figure-8 follow-through loop), ring bend, prusik, figure-eight on a bight, Munter hitch, double fisherman’s, girth hitch, and clove hitch. I’ve never been in a situation where I needed to know more than these seven, although I do know quite a few more “just in case.” Gym climbers will hearten to know that they really just need to learn one knot: the Figure-8. This is the knot most climbing gyms require you to use when tying the rope to your harness.

Even my eight recommended knots might be too many to get you started. Depending on what type of climbing you’re doing, you might never use the Munter Hitch or prusik (neither is a knot by technical definition, but I digress). These knots are more commonly used in trad climbing than sport climbing. Even so, when you climb you can and probably will find yourself in situations or predicaments where knowing these knots will save the day.

This article is just an introduction to knots—not a master class with field time. Read it, then partner with a mentor or get professional instruction from a certified guide. You could also enroll in a climbing class or clinic. There is no substitute for hands-on experience taught by an expert.

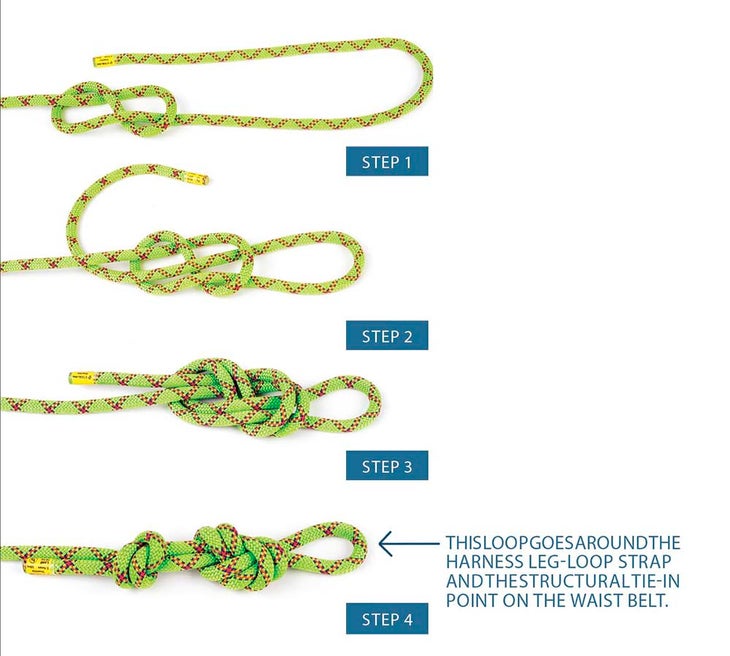

1. The Figure-8 Follow-Through (or Trace Eight)

Your tie-in knot—the one that connects you to the end of the rope—is the knot to learn first. Climbers use various knots to tie in, but the figure-8 is the easiest to learn and the least likely to untie itself. Unfortunately, it cinches up tight after a hard fall, making it difficult to untie. Consider this a small price to pay for security. Practice this knot until you can tie it in the dark.

The figure-8 follow-through is easy to tie. Simply tie a figure-8 knot about 24 -30 inches from the end, then reverse weave the end of the rope backwards through the knot as shown, leaving a 12-inch tail. Secure the tail with half of a Double Fisherman’s knot, or an overhand as a backup. Tighten!

To climb in a gym you just need to know this one knot, the figure-8. You’ll use this knot to tie in to the rope, both for leading and toproping. In fact, many gyms require that you tie in with the figure-8, and they will make you take a test to demonstrate that you can tie it correctly.

Note that the other most commonly used tie-in knot is the double bowline—see how these two knots stack up against one another safety-wise.

Figure-8 Uses

- Connect rope to harness.

Figure-8 Advantages

- Easy to tie and remember.

- Easy to visually inspect—looks wrong when you don’t tie it correctly.

Pro tip: Focus!

Pay attention every time you tie in. Serious accidents happen each year because someone becomes distracted while tying in and either ties this critical knot wrong or never completes it. This even happens to the pros—look no further than the opening pages of Lynn Hill’s memoir. Concentrate as if your life depends on it (it does), and make certain you thread the rope through both the leg-loop strap and the waist belt on your harness, as prescribed by the manufacturer.

Watch pro climber/AMGA guide Genevive Walker demonstrate how to tie all the knots in this story

2. Water Knot (Ring Bend)

Use the water knot to tie webbing to webbing, cord to cord, and rope to rope. The water knot is secure and easy to get right because it’s simply an overhand knot traced through itself. It is possible for the water knot, like all knots, to loosen and untie itself. Inspect it before every climb, and always tie it leaving at least two inches of tail—more is better—on each side.

The main use for the water knot is to tie loops of nylon into slings, or “runners.” Sewn slings and runners are more compact, lighter, and rack more easily, but since you can’t untie a sewn sling they can’t be tied around chockstones or trees (e.g., for descending multi-pitch and alpine routes).

Some climbers prefer the water knot for tying rappel ropes together. The double fisherman’s, however, serves the same purpose and is easier to untie after the ropes have held weight. Generally speaking, knots in wet ropes can be difficult to untie, since they stretch more than dry ropes.

Water Knot Uses

- Tie slings and cord into loops

- Tie rappel ropes together

Water Knot Advantages

- Simple and easy to remember

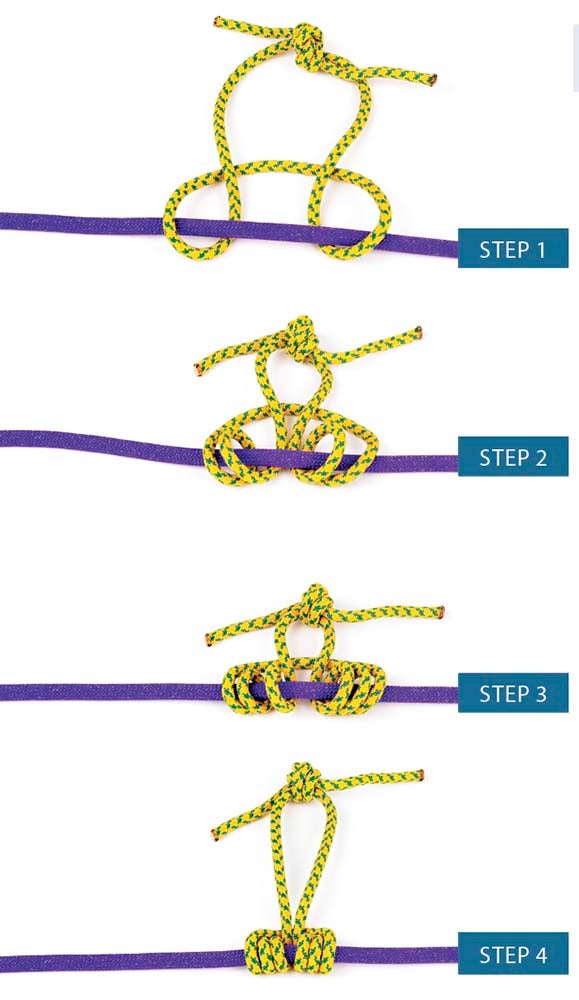

3. Prusik

The prusik is a useful friction hitch that slides freely when not weighted, but bites down on the rope when you weight it. Many variations on the prusik exist, including the autoblock and klemheist. For simplicity’s sake, we’ll stick with the prusik. The most common use for the prusik is to back up your rappel device by tying a prusik on the rope below or above (depending on your preference) the belay device. I prefer it below the rappel device so I can push it down with my brake hand as I rappel.

You can also use a prusik to ascend a rope. Two prusiks placed on a rope and clipped to your harness with long runners let you climb the rope by alternately weighting and unweighting the prusiks, inchworm style. This technique is a lifesaver when you fall on an overhanging route and are stranded, unable to get onto the rock. Even one prusik on a rope is a good handhold, letting you boost yourself past an impossible move on toprope.

To tie a prusik, use 4-6mm perlon cord tied into a 12-inch loop with a ring bend. (You can buy sewn prusik loops.) Thinner cord grips better than thick cord, and shoelaces will work in an emergency. Wrap the loop three or more times around the rope until it bites well enough not to slip. Webbing works in an emergency, but requires more wraps to grip, and is more difficult to loosen and slide.

Prusik Uses

- Back up a rappel

- Ascend a rope, aka “prussiking”

- Good for crevasse extraction and other emergencies

Prusik Advantages

- Simple and easy to remember

- Has many variations to suit various uses

- Can be tied in nearly any cord in an emergency

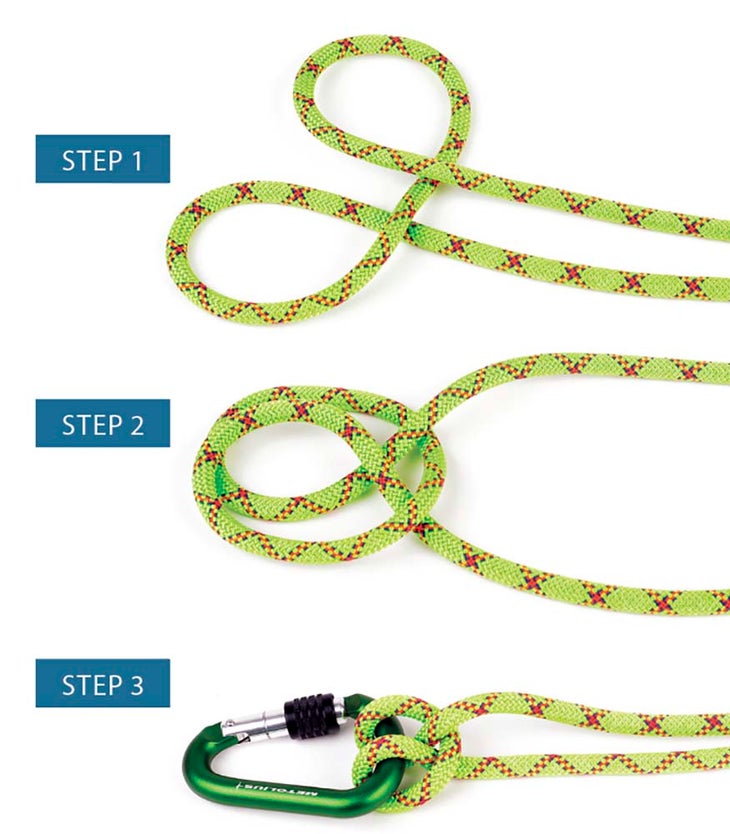

4. Figure-8-on-a-Bight

The figure-8-on-a-bight is useful for quickly securing the rope to an anchor, and for quickly anchoring yourself to a belay station. Note that a clove hitch is the superior choice for tying in to the belay station using the rope, since it’s easily adjustable and easy to untie after holding a load.

Figure-8-on-a-Bight Uses

- Anchor yourself to the belay

- Tie off the rope to anything, as long as you have a locking carabiner to connect it

Figure-8-on-a-Bight Advantages

- Simple and easy to remember

- Quick to tie

- Easy to untie after it has held a load

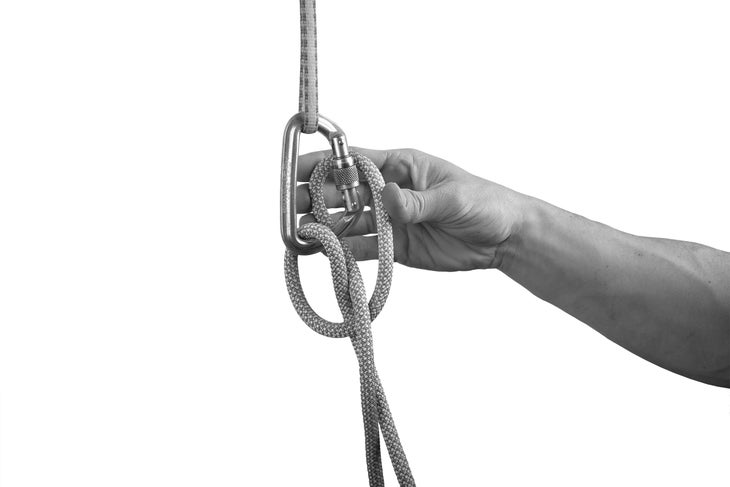

5. Munter Hitch

Drop your belay/rappel device and you will be glad you know how to tie a Munter hitch.

This hitch works for belaying and rappelling: pull back on one side, and the Munter hitch cinches onto itself, creating enough friction to hold a fall or control a rappel. Tie the Munter hitch on a large locking carabiner to allow the knot to swivel, as it must when you are paying out and reeling in slack.

Despite the Munter hitch’s utility, only use it in a pinch. The hitch twists the rope into snarls.

Munter Hitch Uses

- Works as an emergency belay or single-rope rappel “device”

Munter Hitch Advantages

- Works on any size rope

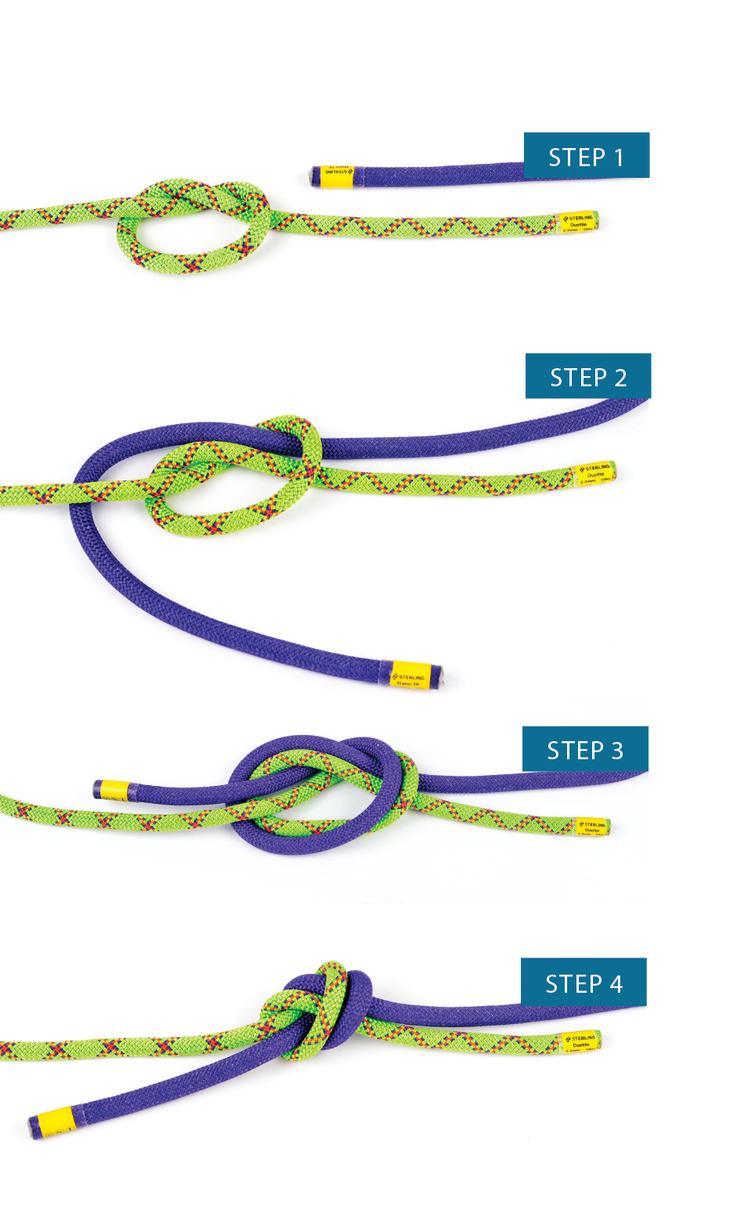

6. Double Fisherman’s Bend

Joining two ropes of the same or different diameter is a job for the double fisherman’s. Due to its many twists and turns, the double fisherman’s is less likely to untie itself than the ring bend. You can also use the proven double fisherman’s to tie off cord threaded through a nut. As a variation (the single fisherman’s), this knot can also back-up and secure the tail of your tie-in knot: the figure-8. Some climbers use the double fisherman’s instead of the ring bend to tie webbing runners.

Though the double fisherman’s works well, it welds itself into a near impossible-to-untie lump after it has held a fall, although less so than the Ring Bend. Since you sometimes need to untie your slings to thread them around objects, such as trees, you can tap and roll a tightened double fisherman’s against the rock to soften it, then use your nut tool (or teeth) to pry it apart.

Double Fisherman’s Uses

- Tie slings and cord into loops

- Tie rappel ropes together

- Back up and secure the tail of your figure-8 tie-in knot

Double Fisherman’s Advantages

- Bomber—unlikely to come untied

- Easy to untie after it has held weight, even in wet ropes

7. Girth Hitch

The girth hitch has innumerable applications, including cinching a runner on a knob or around a tree, attaching a sling to your harness belay loop, and hitching several runners together into a chain to make a longer sling. The girth hitch also works well to cinch a short sling around the shaft of a fixed pin or bolt that sticks out too far, reducing leverage.

Girth Hitch Uses

- Hitch clings together to lengthen them when you don’t have a carabiner

- Tie off fixed pitons that aren’t drive all the way in

- Versatile—you’ll find many other uses for it

Girth Hitch Advantages

- Simple and easy to remember

8. Clove Hitch

The clove hitch is popular for attaching yourself to a belay or rappel station. Quick to tie and adjustable, the clove hitch is more versatile and user-friendly than the figure-eight on a bight. If you tie yourself too close to the anchor, simply loosen the clove hitch and let slack slide through. Re-tighten. Reverse the process to position yourself closer to the station.

A cinched-up clove hitch can be difficult to loosen, unless you know the secret. Wiggle the carabiner out, and the knot falls apart.

The caveat is that you must never use the clove hitch to anchor the end of a rope—if the clove hitch slips, the tail could pull through the knot, untying it. Use the more secure figure-eight loop to anchor the end of a rope.

Clove Hitch Uses

- Attach yourself to an anchor

- Tie off anything that you need to be able to adjust in length

Clove Hitch Advantages

- Versatile—you’ll find many additional uses

How to Tie Knots With One Hand

The crucial equation in alpine climbing—efficiency equals speed, which equals safety—means that every second saved at a belay transition is another second you can spend getting to the top. One simple (and pretty suave) time-saver is tying two often-used hitches—the Munter and the clove—with one hand. You might be at a sketchy stance with one hand on the rock for balance, while you build the anchor and clove yourself in, or you might be simul-climbing and suddenly need to put your partner on belay quickly with a Munter. Whatever the scenario, learning to tie both hitches one-handed will help improve your overall efficiency on long routes (and impress your friends to boot). Plus, they’re easy to learn and will quickly become muscle memory.

Watch the video in this post to see Genevive Walker demonstrate how to tie a clove hitch with one hand, or read the instructions below.

How to Tie a One-Handed Clove Hitch

This hitch is used most often as a way to connect yourself to the anchor. Not only is the clove hitch easy to tie (one- or two-handed), but the beauty of it is that you can adjust the length of the rope on either side of the hitch without untying it.

1. Clip into the carabiner like you would when leading, with your side of the rope on top—coming up through the carabiner and away from the wall.

2. Reach across your rope and grab the bottom strand. Pull it up slightly and create a small loop, with the bottom part of the rope on top.

3. Bring the loop across your rope and, with palm facing gate, clip on the carabiner.

4.Pull on each strand to tighten it up, and you’ve got a clove hitch.

How to Tie a One-Handed Munter Hitch

Every climber should be able to quickly tie a Munter; you can use it to belay or rappel if you drop your belay device. Plus, it’s good for de-icing the rope in frozen conditions. However, it will kink your rope much more than a standard belay device.

1. Start the same way as the clove hitch, with your rope coming up through the carabiner and away from the wall.

2.Grab the strand behind the carabiner with your hand palm up and flick your wrist toward the carabiner to create a loop (bottom section of rope on top).

3. Turn that loop so your knuckles are facing the carabiner and clip it on.

4.Pull on each strand to tighten; the Munter should flip through the carabiner.