"The last thing I remember after reaching the chains at the top of the route is landing feet first on the ground, crumpling in a heap."

The post How Did Two Longtime Pro Climbers Forget to Tie Their Knots? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

In 1989, at a small crag in France, the Styx Wall at Buoux, Lynn Hill forgot to finish tying her knot connecting the climbing rope to her harness. At the top of a 70-foot warm-up, she started to lower off. The unsecured rope end pulled through and Lynn went airborne, windmilling her arms to stay upright. She crashed through branches of a tree and piled into the ground between two boulders.

When Lynn first told me about the accident, perhaps a year after it happened, I wondered how the many time world sport-climbing champion, the visionary who had first free climbed the Nose, and my long-time partner on and off the cliffside, had made such a rookie mistake. Twenty-five years later, however, at a climbing gym three miles from my house, I also failed to finish the tie-in knot to my harness. The last thing I remember after reaching the chains at the top of the route is landing feet first on the ground, crumpling in a heap and rolling up to see my tibia jutting out a hole in my shin. Fifty days and five operations later, I got discharged from UCLA Medical Center and spent most of the next year on crutches.

In the long months following my accident I felt puzzled and humiliated that Lynn, arguably the world’s finest free climber in the early 1990s, and I, who’d climbed steadily for 40 years around the world, and had written a dozen books on technical climbing, had both fallen asleep on the job. I felt especially guilty having decked in the “safe” environment of a climbing gym.

A little research showed that while serious gym accidents are rare (occurring less frequently than falls while hill walking, for instance), they do happen, the majority of which are basic pilot error. The question is: how did we, with decades of experience between us, simply fall asleep? The answer became clear when I read an article about industrial safety protocols, with the tagline being “complacency is safety’s worst enemy.”

The relevance of industrial safety issues to gym climbing was brought home by the oft-repeated point that no matter the particular task—from building cars, to painting a submarine—accident prevention is always a matter of vigilance. The key regarding gym climbing is to understand what is vigilance, how vigilance is practiced, when it goes missing, and why. The following Safety Checklist review might have saved me from an open fracture, and the great Lynn Hill, a broken ankle and dislocated elbow.

Vigilance is a matter of maintaining focused attention on a task. When our attention goes lax, often through distractions, knowledge and experience count for nothing. Accidents in North American Climbing (published annually by the American Alpine Club) shows how many expert climbers are injured on “easy” ground. Climbing is a contest with gravity, and gravity never sleeps. When we do, no matter the terrain, bad things can happen.

Vigilance often goes missing at the end of a session, when we’re tired, hungry and thirsty, or when our focus shifts from climbing, say, to socializing with those around us. Whatever the reasons, when our guard goes down, complacency (a false sense of security) steals in. Be clear: complacency is the principal cause of indoor-climbing accidents. Easy routes require the same vigilance as hard routes in terms of following basic safety procedures. I fell off a warm-up route. Any gym employee will tell you that most accidents happen on routes far below a given climber’s limit.

Vigilance

The desired state of mind is relaxed vigilance, but what does that mean? It does not mean hypervigilance, nervously scanning the environment, waiting for an accident to happen. A tense mind and body causes tunnel vision. We operate best when we are calm, alert and fully present to what’s directly before us, glancing ahead toward where we are going.

In short, vigilance assumes three basic forms that have stood the test of time: A) appraising difficulties B) regular reminders and C) oversight.

Appraising difficulties

Experienced gym climbers constantly appraise potential hazards and discuss solutions as a matter of course. You’ll see some version of this ritual in most every adventure sport. The champion studies their opponent.

We can’t appraise the difficulties unless we see them, and we can’t see them unless we’re paying attention.

Regular reminders

A safety checklist, part of every sport and technical activity, is not a one-time drill. We repeat it over and over, reminding ourselves of what to avoid, and checking our own systems at regular intervals. That’s the reason cars have gauges, which inform us about current conditions. We know those conditions will change over time, introducing a new set of potential hazards.

Double-checking our systems, glancing at our “gauges” before and after every burn, should be part of our standard practice. Anything less is driving with your eyes closed.

Oversight

Oversight means not only checking our own systems, but that of our partners, recognizing hazards and mitigating them. In virtually every gym, a revolving cast of staff members is circulating, keeping an eye out for trouble (again, oversight). But gyms get crowded, especially at peak hours, so our principal oversight comes from our partners, and we return the favor in kind.

Most injuries happen through bungling basic procedures we’ve done a thousand times—like tying into the lead rope. We suffered an avoidable accident because we got complacent. As Lynn’s and my accidents bear out, accidents are not just rookie mistakes. The best of us get complacent. Fighting complacency is a team effort. Without constant vigilance, gravity has the advantage.

Standard safety procedures vary slightly, gym to gym, depending on the chosen belay devices and other factors. Every gym runs mandatory belay and leading tests, conducted by trained staff, when the particulars are made clear and your proficiency is tested and reviewed. Safety regulations are also posted in bold print throughout most facilities. But ultimately your safety lies in the hands of your partner(s) and yourself. Again, the good news is that gym accidents are comparatively rare, and nearly all of them are avoidable. Once you are competent with the basic safety procedures, it all breaks down to vigilance.

The post How Did Two Longtime Pro Climbers Forget to Tie Their Knots? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

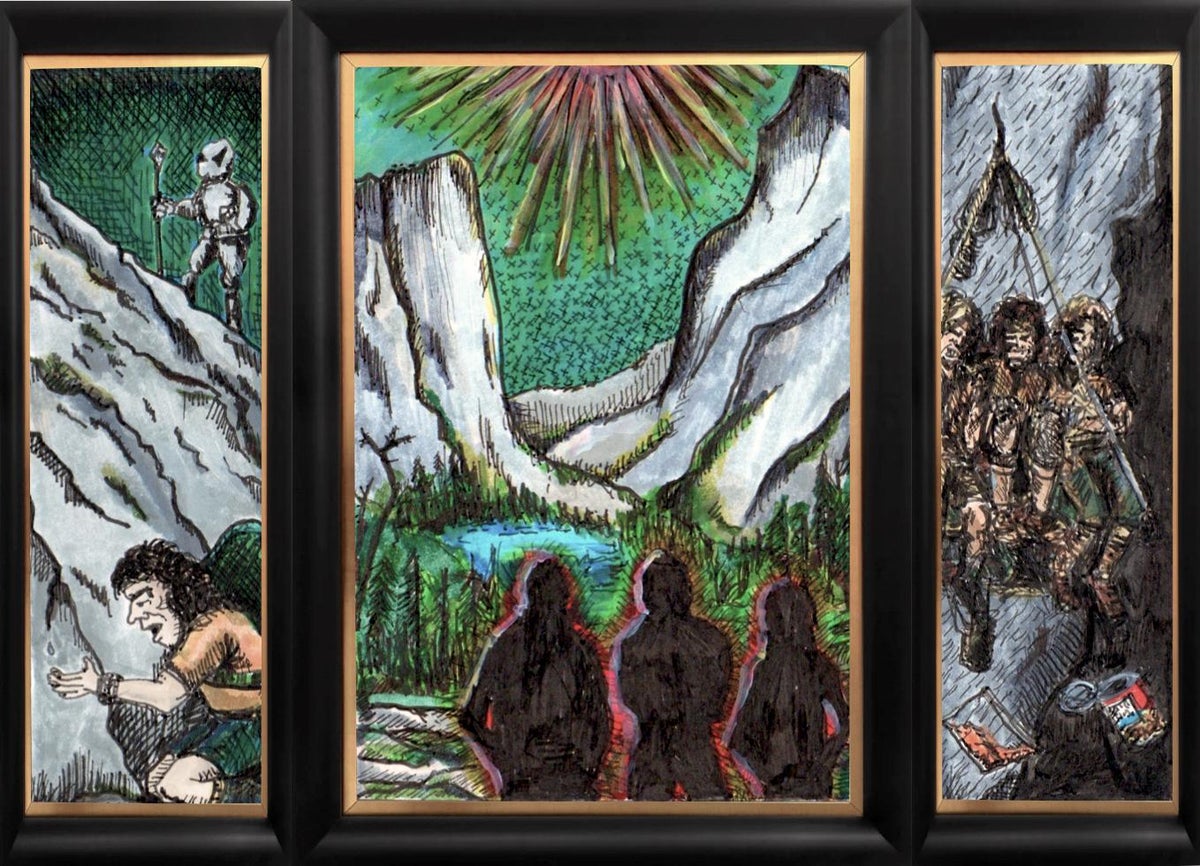

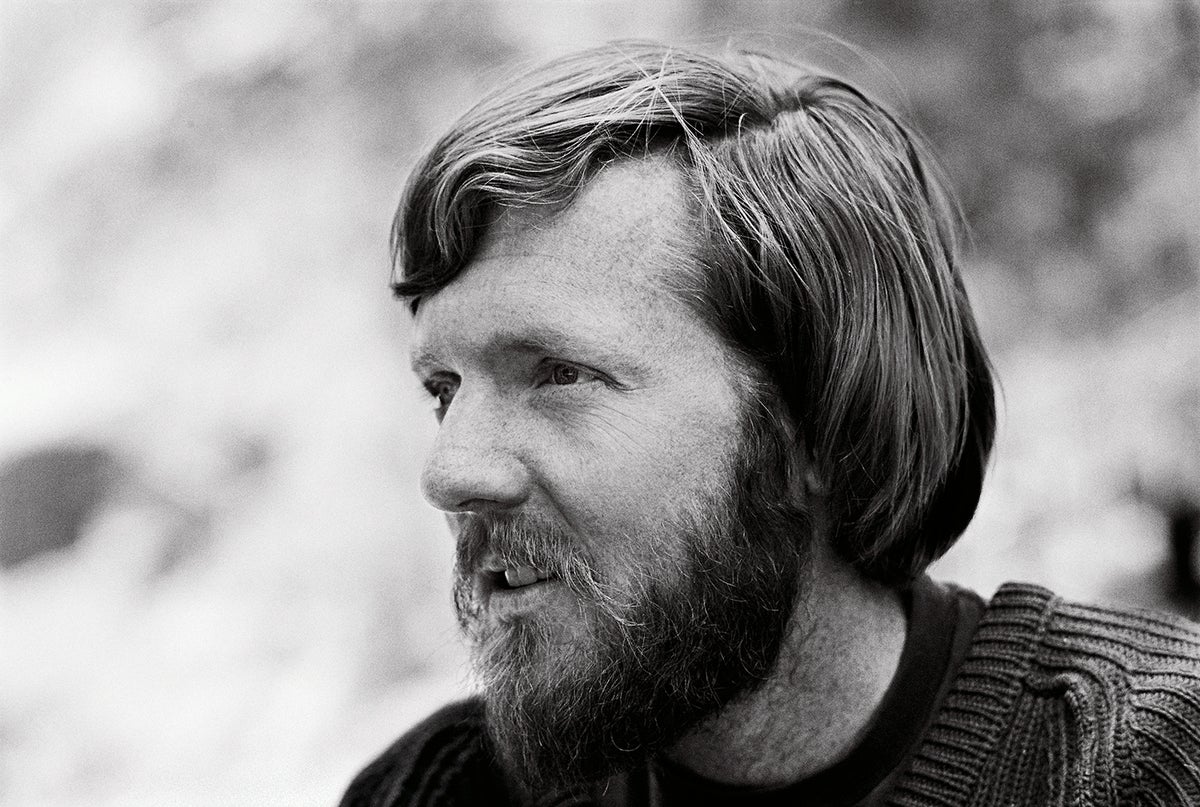

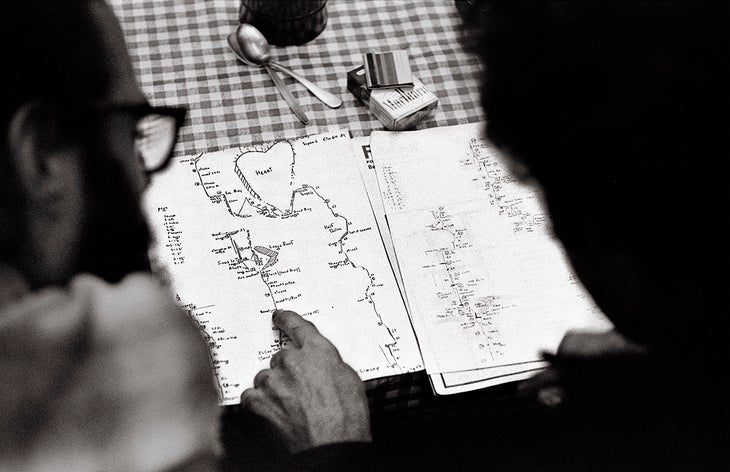

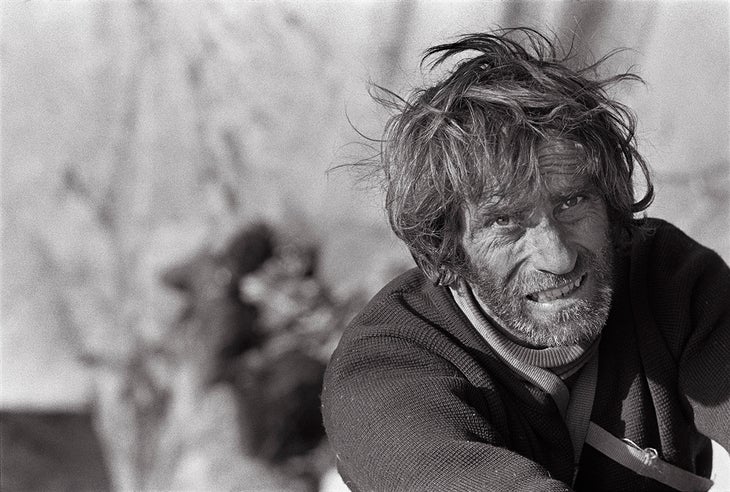

Who they were, what drove them, and the deeper questions that came later.

The post A Short History of The Stonemasters appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

The post A Short History of The Stonemasters appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

"We pushed on, as if floating in slow motion through a Hieronymus Bosch painting, found by tilting life on edge for 1,200 feet and emptying its pockets."

The post Benighted and Waterless on Washington Column appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

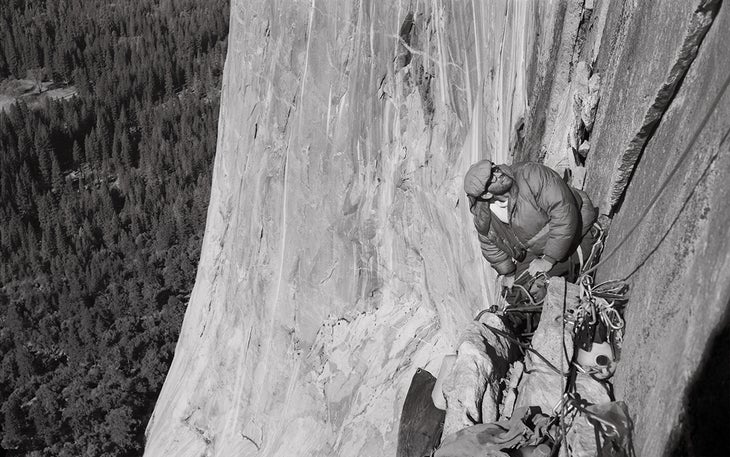

Richard, Jay, and I made good time, despite the angry weather, and climbed most of the way up Washington Column before bivouacking on Overnight Ledge, three rope lengths from the top. Night came tenderly but our hunger felt murderous once the adrenaline wore off.

Jay had brought a zip-locked block of cheese, swimming in yellow varnish after cooking in the haul bag all day. We wolfed it down in no time. Same with the summer sausage and family-size can of Dinty Moore stew. This was our first go at scaling a big wall, and knowing the hunger of the castaway.

We’d planned to start three days before but got washed out by a late summer thunderstorm that flash-flooded camp and the Visitor Center, close by Yosemite Falls. Now we had no water at all, swilling the last of it to gag down that funky cheese. No worries, said Richard. We could sleep the night away and climb off the wall in a few hours next morning. Then tank up on water once we got down.

We slouched back, wasted, three wannabe rock stars, shoulder to shoulder on our little granite bench.

Between roping up at the base and clawing over the summit lay a vertical gulf we could gaze past but never fully plot beforehand. The sorcery came from crossing that gulf with an unproven strategy made up on the spot, which felt risky as hell. Without a reckless curiosity about the unknown, where all things seem possible, we wouldn’t have gotten far. A dozen years later, we’d have fifty walls bagged between us, and half of those were crapshoots.

Richard kept fiddling with gear, pitching a few broken bits out into space and us chuckling anxiously as they plummeted through the night before clinking off the wall a thousand feet below. We all feared falling through the air, but tumbling through my mind was my greater fret. Dissolving into the crypt of self. Big walls as body snatchers. I’d quested up there, offering myself to fear, as the void reached up, grasping at my feet, dangling off Overnight Ledge. Slowly, the white noise died off, leaving signal, which is soundless and always right now.

To whom did this silence answer? Not to me. The world of sounds and shades and ten-thousand forms was no longer arrayed around me as the focal point. The order of things had flopped, somehow. Now everywhere was the center. Perhaps this was how the world perceived itself.

I had no idea, starting out that morning, as we idled up the trail, shouldering vicious loads. Inaccessibility was part of the magic. If anyone could stroll up here, most of gravities power would be lost. We were experienced climbers—not on this scale, it is true—but we were hungry for trouble and knew about ropes and pitons and going up. We all felt confident we were where we belonged.

Around noon, a fiery breeze blew the clouds away and heat waves welled off the rock, blistering to the touch. We’d climbed too high to safely retreat, otherwise we would have. Heat is heinous for its unrelenting strength, which no one can understand until it is endured. We panted, foreheads banging, seeking the patch of shade beneath the haul bag.

Then clouds rolled in like foaming breakers, darkened and snarled, as rain teemed from the sky for what felt like hours, us still stranded in slings. Finally the sky broke apart and the rock, scarfed in mist, dried out. For another hour, we dangled there, staring into the blue distances, wondering if Nature had lost Her mind (toggling the dial on the thermostat like that), shivering ourselves back to action. Rangers said the swing in temperatures was the largest in a day since they began keeping records in the 1890s. We sat stupefied on the ledge, wondering how this mercurial rock monolith could apprehend such extremes.

I never know a mountain till I’ve slept on it. But beat down like that, sleep refused me. The lights and campfires gleamed in the valley. My mind went blank. A quiescence without beginning, crawling with ancestral fears. It must have spooked the others as well because we all started talking furiously about nothing, blue stars winking back at us. It felt like being in church, almost, till a hankering for a sip morphed into brain-frying, soul-murdering thirst. It happened—like everything else in this circus-mirror world—one-two-three.

We’d climbed through the heat wave and had downed maybe a quart of water per man, many quarts shy of the required dosage. That triggered, on a time delay, a thirst like a freight train that ran us right over.

We sat in stupors, crying out for a drop. Anything. Staring at the moon, trying to will it across the sky. Time became the enemy. The mountain, monstrous. At first light, like three bursts of fire licking the wall, up we climbed, summiting in a daze, our mouths and eyes glued shut.

We staggered into forest and traversed right over a saddle to the start of North Dome Gully, a mostly treeless series of slabs and sandy ledges marking the start of the descent route. The storms of centuries had rolled a riot of teetering boulders into this ditch, bristling with snaggle bushes. The sky was blue blue and, already, the gully heaved with heat mirages. Jay warned to stay far left because out right loomed the Death Slabs, steep and naked granite covered with pine needles, where a traveler, dying of thirst and loaded with ropes and ironmongery, only went to die.

We trundled down, breathless and seeing double, through a maze of boxcar boulders and manzanita. Gaping at the Merced River, half a mile below, meandering from Tenaya Canyon and wending through the valley. A silvered strand of life, us shrieking inside at the sight of it. There, but tragically out of reach. We would gladly have sold the other guy into slavery just to have one cool inch of that river.

I couldn’t make out Richard’s words, just followed his hand, pointing to seep, drizzling from a fracture in the wall of the ditch. Clear water. Living water.

We’d all three stripped down to short shorts and sneakers, our thirst just as roaring and naked as our bodies. I reached a hand into the thread of drizzling brightness so intense that my mind stopped. It was the most unguarded moment of my eighteen years on earth.

Jay clawed at the drizzle, trying to catch it. Then rooted through the haul bag, retrieved our tin Sierra cup, and held it below the trickle. We watched, agonizing second after second, as the cup began to fill. Jay couldn’t wait and tossed down a spoonful. I wrenched the cup from his hands and held it under the drip, and we kept doing this in turn till round about noon, our bodies filled back out and we could see straight and make words again.

We pushed on, as if floating in slow motion through a Hieronymus Bosch painting, found by tilting life on edge for 1,200 feet and emptying its pockets. We’d never suspected a world so stark, so vivid as heat and cold and hunger and thirst. The absoluteness of water dripping from a rock. The teetering minarets and flying buttresses. Even the white rags of clouds, shredding as we strove for the silver river.

***

Also Read

The post Benighted and Waterless on Washington Column appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

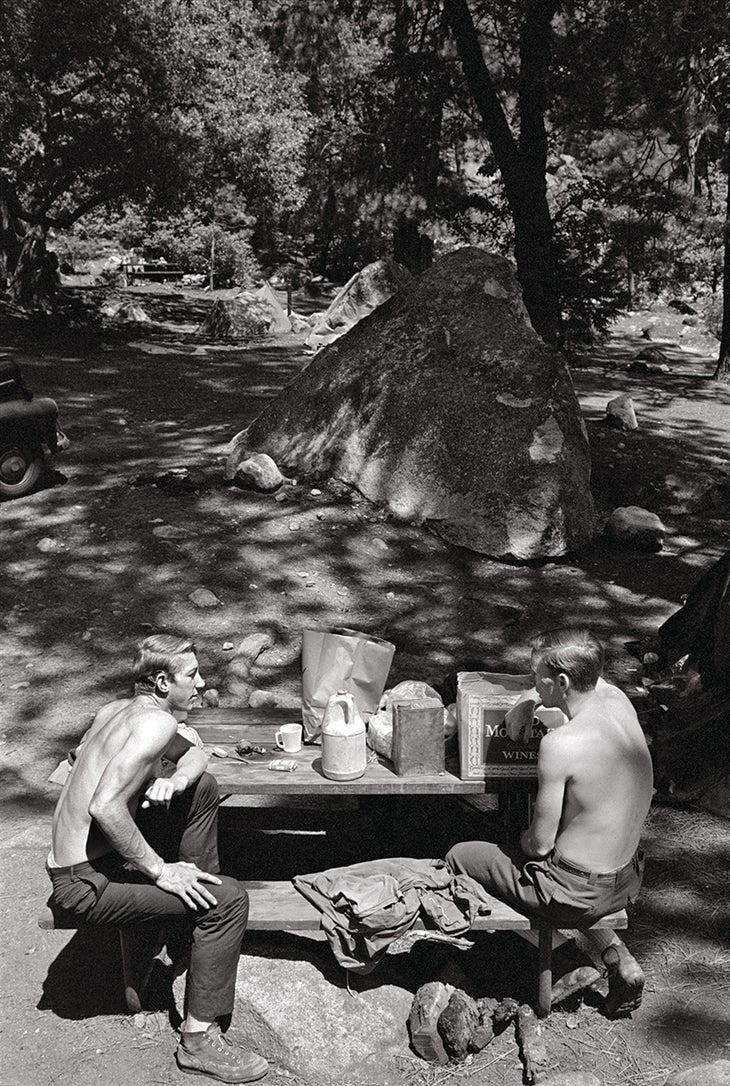

A gang of Camp 4’s hungriest showed up for an orthodox affair fielded by the Arise and Shine Pentecostal Church out of Modesto, California. We’d never seen so much grub...

The post We Stole the Preacher’s Food and Ran For It. I Had to Come Clean appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Work took me there and the mere sight of the sign for Modesto, California, Pop. 166,430, wrenched me back to the picnic from hell, when we scarfed all the faithful’s food and ran for it.

A handful of us teenagers were spending our first summer in Camp 4, the climber’s al fresco flophouse in Yosemite Valley. We had no money so we frequently crashed picnics and barbecues put on by groups streaming into the park for weekend retreats. We tried keeping our numbers down, losing ourselves in the swarm; but this time a gang of Camp 4’s hungriest showed up for an orthodox affair fielded by the Arise and Shine Pentecostal Church out of Modesto, California. We’d never seen so much grub, spectacularly arrayed over half a dozen picnic tables.

We sang along, mouths watering through all twenty verses of “Fire Fall Down.” Then Preacher John drifted into homily, touching on the Eight Visions, and Daniel in the Lion’s Den. We wanted to chuck the Preacher in there with him, tortured as we were by the smell of those burgers and ribs. Then some laps through Glory Be, us gritting our teeth, so dying to charge those tables and all that golly that space/time threatened to blown apart.

When at last we rose and Preacher John said, “Ah-Men,” twenty climbers stampeded over the congregation and plunged bare hands straight into vats of barbecue beans and potato salad, shoveling huge and sloppy loads into their mouths. Faces were mashed directly into pies and layer cakes as tabletops of tacos and fried chicken vanished before the proper crowd had eaten a carrot stick. When the shocking news spread that the food was all gone, we scattered into the forest with so many franks and ribs and rhubarb pies on board we could barely stumble back to camp.

Now fifty faces glared at me from that road sign, asking how come? Faces I couldn’t flee till I looked up Arise and Shine on Google and drove there in search of Preacher John. I’d put down the bottle a decade before but these 9th Steps (making amends) kept wearing me out. Only thing worse than doing them were those faces.

[Read: Stonemaster John Long Comes Clean on Alcoholism]

Preacher John was not so old as I remembered. He flushed when I mentioned that weekend in Yosemite. The moment hung in cringeworthy limbo till I asked how I could make things right. He flashed a sideways grin, amused that I thought he’d send up a prayer and call it good. Instead, I spent Saturday and Sunday sanding and painting and pulling weeds behind the plain-wrapped chapel.

As we painted stairs and yanked thistles, Preacher John—blue jeans, black T, ragged Keds sneakers—started talking about the intractable challenges in his life. People dying. Too much month at the end of the money. Hearing someone talk so undefended touched on worlds I’d never suspected, just as Preacher John had never imagined a refuge like Arise and Shine. For going on fifteen years, his congregation of ex-cons, bikers, porn stars, and grifters kept stumbling into grace. Preacher John couldn’t explain how he’d come to run the operation, or how it all worked. Only that most of the time, it did.

Preacher John suggested that, during services on Sunday evening, I stand before the brethren and come clean on the Grand Theft Spare Rib and Shortcake Debacle I’d helped author back in Yosemite.

“Guess I owe you people that much,” I said, and Preacher John said, “It ain’t for us, man. It’s for you.”

Several in the crowd had been in the valley those dozen years before, and no sooner had I described that shitshow, and my part in it, than they swarmed round and pumped my hand and said God works in strange ways most of the time, so far as they could tell. Nobody earns grace. It finds you.

Once the congregation retired, leaving Preacher John and me to our lonesome, he hemmed and hawed, grabbed himself, fiddled with a cup, till he finally mumbled something about a dream. A picture in his head, really. Maybe just a silly idea.

Jesus, Reverend. Come out with it already.

“Half Dome,” he said. “Can you get me up there? On top?”

That meant hiking him seven miles up the rugged back-country trail to Half Dome, the most iconic granite monolith in Yosemite, and wheedling him up the cable route (along the Dome’s eastern shoulder) that, every summer day, tourists march up en mass to the summit. It’s an ass-kicker hike to get up there, and the Dome tops out at nearly 9,000 feet. But the Preacher seemed dead-set. And I often do my best with a mission. Now I had one.

That evening, we drove the 100 miles to Yosemite, shooting for a blitz ascent, since Preacher John had to conduct services the following Tuesday night. To simplify logistics, I copped a 24-piece Super Bucket Combo, with sides of mac and cheese, slaw, biscuits, and corn on the cob, from a KFC as we blew out of town. Plus two-liter bottles of Mountain Dew, infused with enough cane sugar and caffeine that after three mouthfuls, you’re ready to swim to Oahu (you’d make it, too). That was our trail and bivy food to get us up the Dome and back to the parish in two days flat.

It took us till late the following day to gain the summit. Barely. Preacher John had a bum wheel and hiked with a wince. We stopped many times for him to massage his leg; it took us over an hour to cover the last bit, up the cables, two of a hundred and some-odd people who climbed Half Dome that day.

On the summit at last, the narrow valley, far below, stretched down canyon through continents of light and shadow.

We strolled around the arching Dome, feeling like sky walkers, till Preacher John slouched back on the granite slab and muttered out some anecdotes, pulled up in shards. How during the Vietnam War, he’d spent 416 days as a POW in the Son Tay prison. Even the good Lord couldn’t see him through a few dark nights, when all that sustained him was a childhood memory of camping in Yosemite with his single mom, and an image of Half Dome, floating in the sky like a celestial atoll, beyond pain and conflict, and the shrapnel in his leg.

We walked out onto the Diving Board, a flat stone parapet cantilevered over Half Dome’s 2,000-foot North Face. An inch too far and you’re off for a half-mile free-fall with ample time to contemplate the landing. But a steady wind had picked up, gusting straight into our faces so we could stand with our toes out over the quick, arms outstretched, leaning into the zephyr and feeling like Friedrich’s classic, Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog — except there were two of us, not one, and no fog, the Preacher and I fairly flying in an experience so attuned to our needs that I believed in something for a minute.

“I’m so famished,” Preacher John yelled into the wind, “I could eat the hind legs off the Lamb of God!”

Over at our packs, the Preacher retrieved the Super Bucket Combo of Kentucky Fried, and I watched him wolf down a cubit of greasy chicken, two tefachs of mac and cheese, an amah of slaw, and three baths of corn, washing it down with the Dew. Mighty gracious of him to leave me one measly drumstick in the bottom of the bucket, and nothing else. Fucker.

“Dude!” said the Preacher, two veins leaping off his neck. “You didn’t leave us nothing.”

Took him three days of painting and gardening and hiking with a wince for those hard feelings to geyser out of him. He wagged a finger in my face.

“We even now, or what?” I said.

“Getting there,” said Preacher John, who walked back onto the Diving Board. The wind had died and he gazed into the western expanse, which opened into rolling highlands spilling off towards the measureless brown plain of the San Joaquin’s.

We bolted the last of the Dew, pulled on our packs, and stumbled back down toward all the people, places, and things we could grab hold of and chew down to the bone, working up some strong regrets, come to terms—always a bar fight—then do it all over again.

The post We Stole the Preacher’s Food and Ran For It. I Had to Come Clean appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

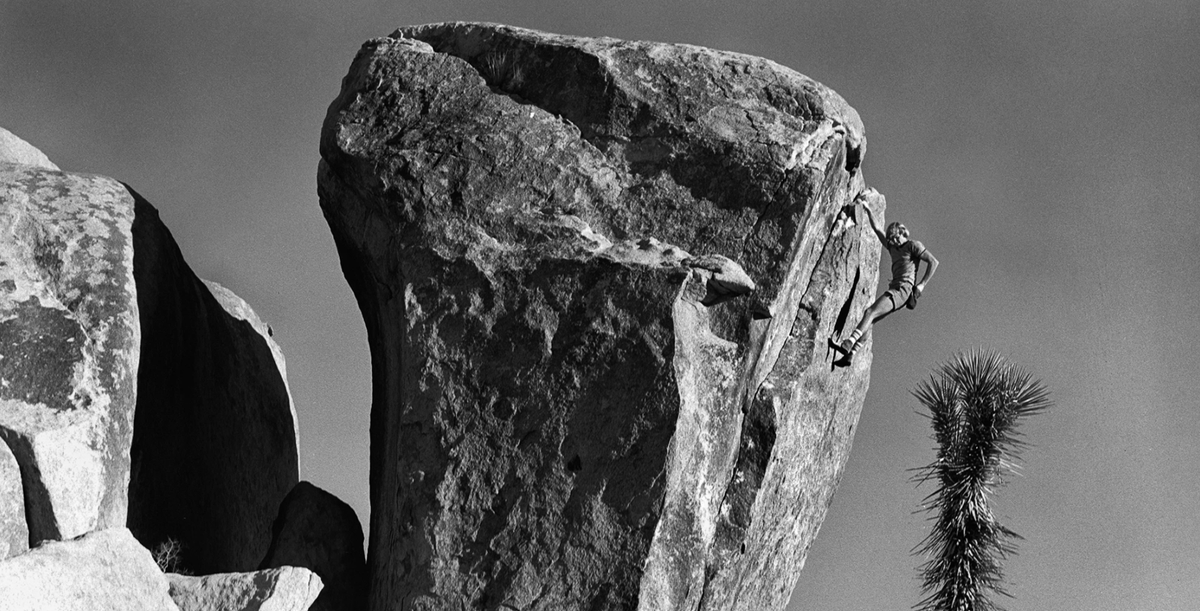

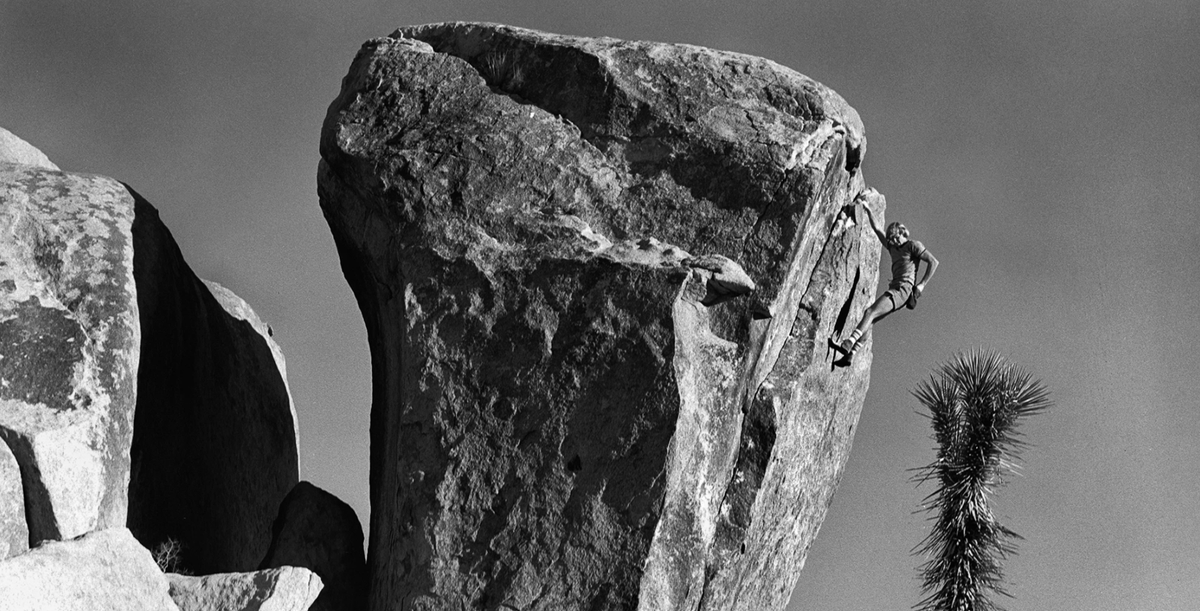

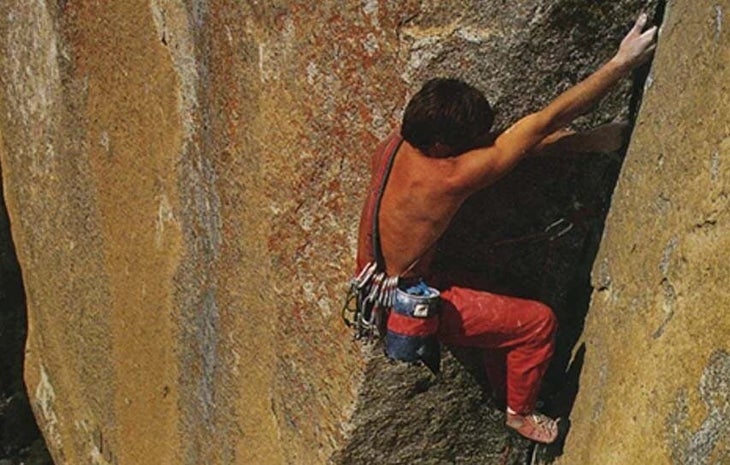

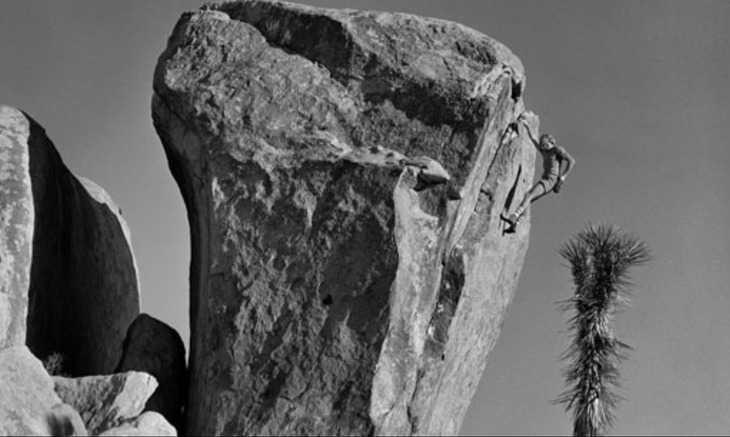

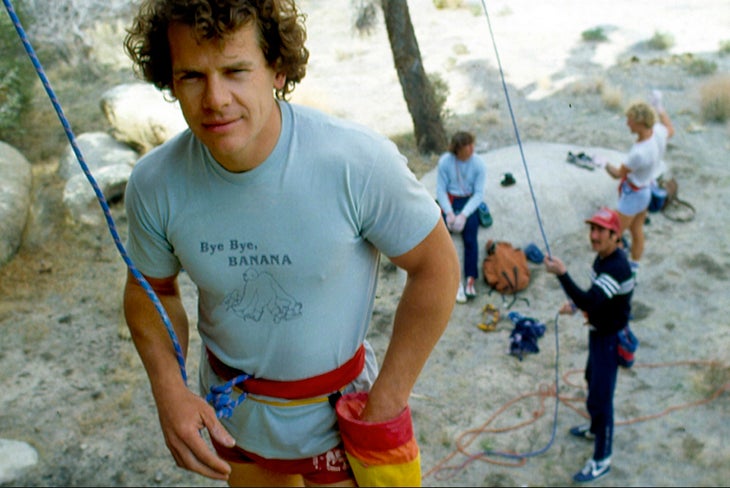

Most know him for his historic big wall ascents in Yosemite. But in fact, his favorite pastime was always bouldering. Here, he reflects on the discipline's evolution.

The post True Fact: John Long, Stonemaster, is a Bouldering World Cup Junkie appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

1970. During a Rock 1 course out at Mount Rubidoux, near Riverside, California. I’d just learned the figure 8 follow through when Phil Haney—in skin-tight, smooth-soled climbing shoes, his hands dusted with chalk—campused up the overhanging, 30-foot high, Joe Brown Wall. My eyes went out on stilts. I walked over and clasped the first holds, which felt like hacksaw blades, and burst out laughing.

“That there’s bouldering,” my instructor said, but it looked like magic to me. And Phil Haney was a regular Merlin.

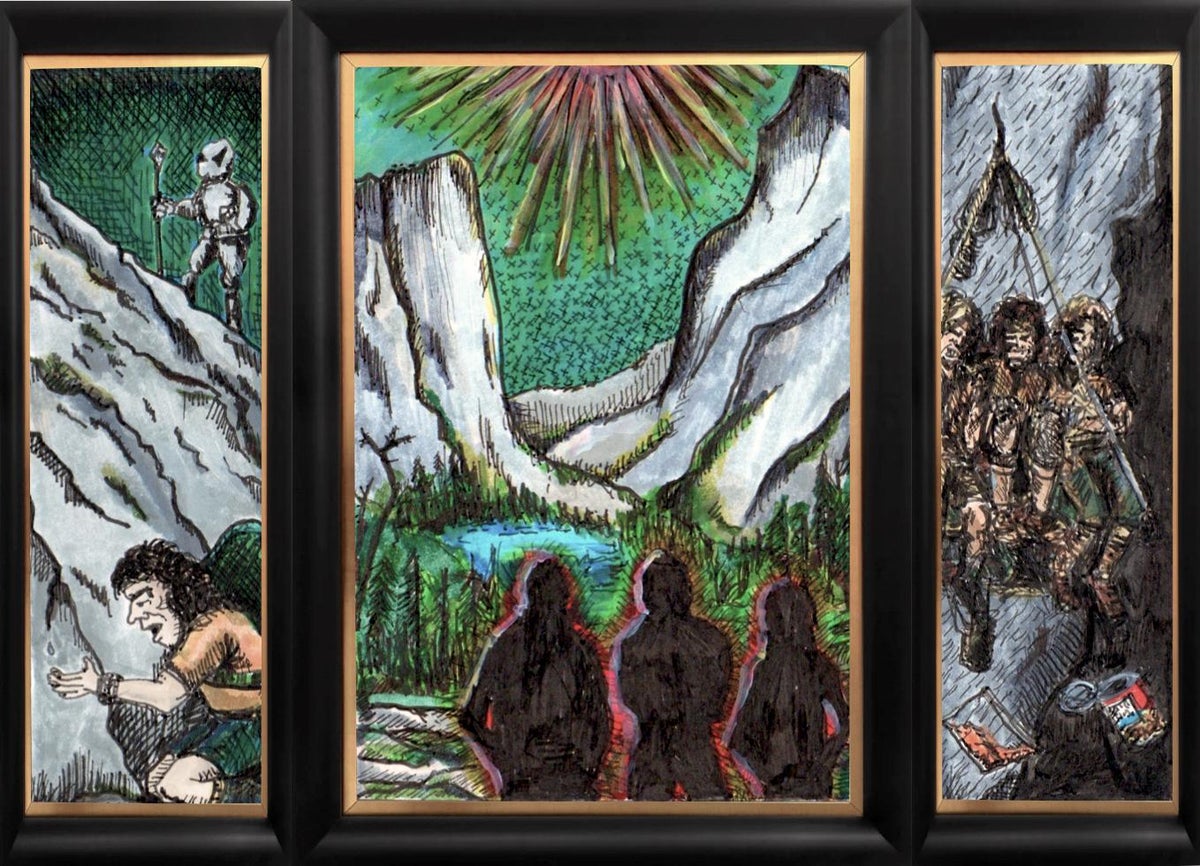

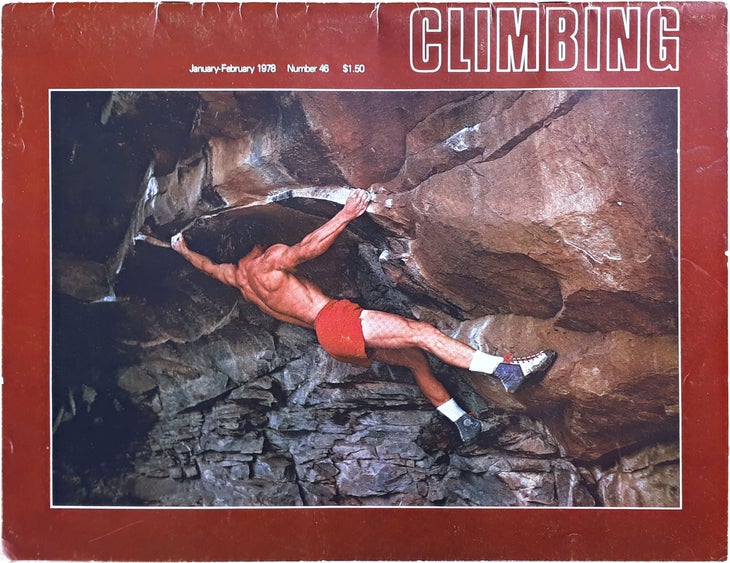

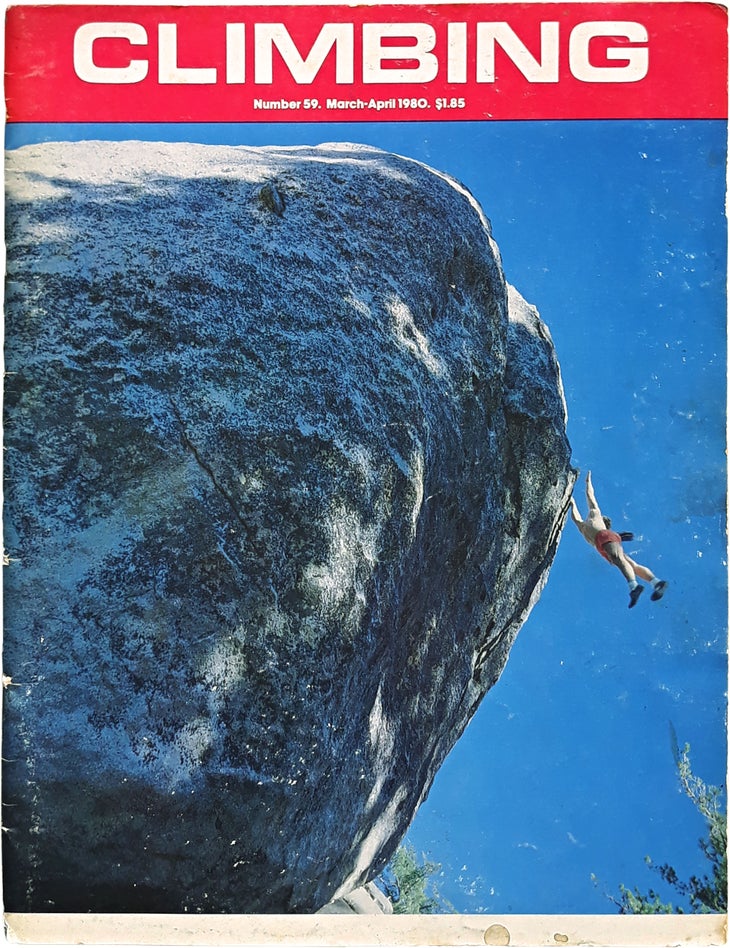

Six summers later, with a copy of Pat Ament’s Master of Rock in hand (basically a photo-essay on John Gill, “Father of American bouldering”), Climbing Magazine editor Michael Kennedy and I piled into his wheezy Fiat and tooled around central Colorado, hitting Flagstaff, Split Rock, Horsetooth Reservoir, down to Pueblo, and beyond, where starting in the late 1950s, Gill debuted dynamic climbing techniques on a slew of iconic boulder problems.

I frequently bouldered, mostly as practice for trying to free climb Yosemite big walls—my obsession back then. Michael, meanwhile, was questing up frozen mountains in Alaska and later that year came within a stone’s throw of bagging the FA of the North Ridge of Latok I, one of mountaineering’s greatest prizes. We’d both heard the legends about Gill levitating up holdless rock, stories rarely mentioned in the blinkered climbing media. That is, until Ament wrote Master of Rock, and Michael had a wise idea.

I’d crank as many Gill creations as possible, far and wide, with Michael snapping photos. Then I’d write an article and Michael would run it in Climbing as a cover story. The notion of a “bouldering expedition,” chasing the ghost of John Gill, felt as silly and exciting as searching for Paul Bunyan. We had no idea how readers might feel about it.

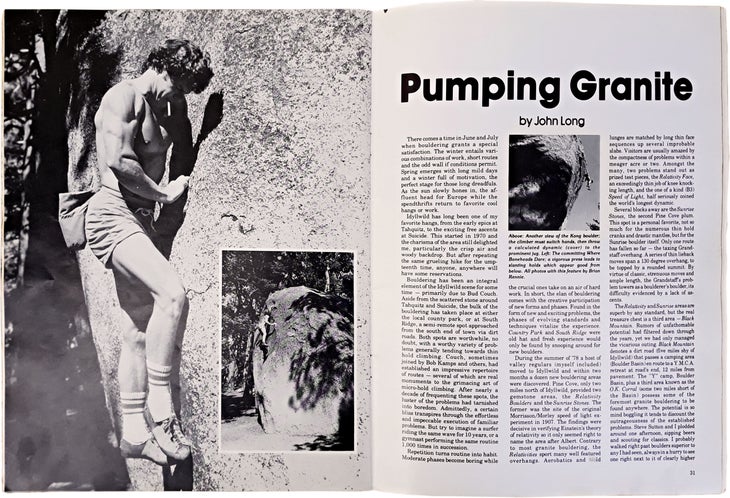

The highlight of our adventure was meeting John Gill himself, down in Pueblo, getting a guided tour of his private reserve, and repeating a few classic Gill problems—which favored the jumping-bean style I most admired. To my surprise, our article (“Pumping Sandstone”) blew up, and helped kick-start the modern bouldering rage, though how bouldering would evolve—as both an athletic pursuit and an Olympic sport—was something Michael and I could never have imagined. John Gill, I suspect, had seen it all coming, decades before.

2023. Forty-five years after “Pumping Sandstone” was hot off the press, and 5,477 miles from my place in Venice Beach, California, at the Esforta Stadium on the outskirts of Tokyo, 171 climbers from dozens of countries have gathered for a Bouldering World Cup, which kicks off the 2023 IFSC season.

I’ve dragged myself out of bed at an ungodly early hour to watch the live stream, gagging down a quad shot and two Krispy Kreme Custard Filled to get my engine running. I could wait a few hours and leisurely screen the comp on YouTube. But shit, man, if hard bouldering’s going down, I can never wait, even if I can’t do it anymore.

That sound on my laptop, over on my desk, is British announcer Matt Groom describing the format for the finals: Four boulder problems, six climbers, three podium places, in a men’s final so beastly hard that two-time World Bouldering Champion Tomoa Narasaki bombed out in the semis.

Groom says to keep an eye on 18-year old wunderkind, Hannes Van Duysen, the first Belgium climber to have a shot at a World Cup medal. And magnetic French whippersnapper, Mejdi Schlack, also 18, who moves with a shapeshifter’s mojo while flashing his dopy, endearing smile, reminiscent of Bocephus, the ventriloquists’ dummy from Gran ‘Ol Opry.

Rounding out the field are Kokoro Fujii, six-time World Cup winner, and the old man at 30; his countryman, Sarato Anraku, just 16, yet another Japanese gym climbing prodigy; celebrated South Korean boulderer, Jongwon Chon, 27, with the razor cut do and arty tats; and dazzling French grimpeur, Paul Jenft, 19, who slayed the junior tour, and has qualified first here in Japan.

Kokoro, who qualified last, gets the comp rolling, jumping straight off the mat to an unbearable bear hug off a swollen pink volume, feet dangling, his arms so outspread he resembles Da Vinci’s Vitruvian man viewed from behind. Then a windmill crossover with the right hand, stabbing for a donut hold, the hole sloping as the shingles on the Sydney Opera House—and only wide enough for one paw. Kokoro sticks the first donut, but quickly glazes off on further attempts. Same for the consummate Belgium, Van Duysen, who follows.

Then Mejdi Schlak, in the French team’s saucy black tank top and short shorts ensemble, bursts from iso, sprints across the mat and hurls himself at the problem, sticking the first donut on his fourth try, only to huck a deleterious dyno to pair of dual-tex bread loaf holds bolted nearly vertically onto the wall, which Mejdi sticks via a disturbing Gaston. Then another big dyno to a second donut and Schlack logs the first and only send of boulder one. A perfunctory chest bump and growl, then the Frenchman, to wild applause, dashes off the stage and through the curtain back to iso. One problem down. Three to go.

Back in the early-1970s, a few years before “Pumping Sandstone,” most of us moved slow and static as a ladybug wheedling up a Lodgepole pine. As the angle steepened and the holds rounded off, thrusting off foot holds, while slapping up top, carried us over grim stone with style and dispatch. Took a while to master open-handed climbing, to dial in dead-point timing, and to latch holds with muscles engaged; but practice on the boulders made perfect, and leading climbers started flying for it.

Old school duffers dissed dynamic movement as cheating, since a sober leader, a dozen feet out on a wired RP, would never start hucking dynos. This was the Indian Summer of the trad era, when bolts were shunned and arranging protection remained a critical concern. But dedicated boulderers were appearing at every small crag across the country, and how their artistry translated to roped climbing was an increasingly irrelevant question.

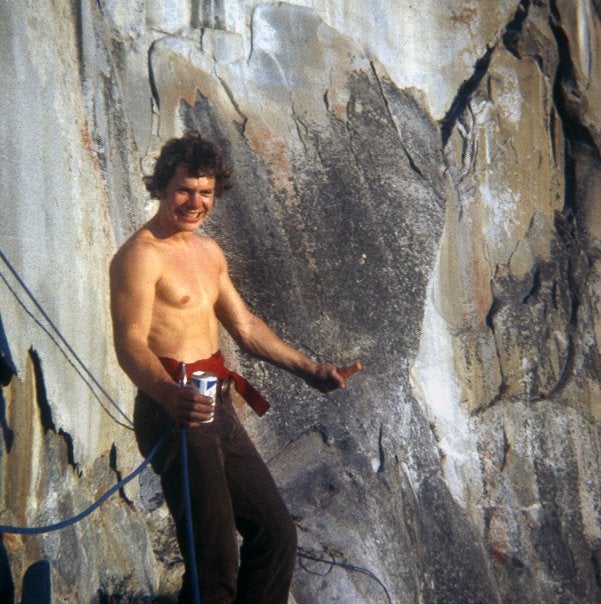

(Photo: John Long Collection)

But what about the fabled John Gill? Faster than a speeding bullet. More powerful than a locomotive. Able to leap tall boulders in a single bound—or so we’d heard. How might we match up with the master, in terms of dynamic movement, which was starting to dominate our curriculum? Michael Kennedy cooked up “Pumping Sandstone” to answer that question, one way or another. I was mostly the stunt dummy.

Boulder Problem 2 attacks a cruel slab, a degree or two off vertical. The only holds are widely-spaced orbs resembling piebald beach balls sawed in half. Plus a jib the size of a chickpea. Kokoro Fujii, Sarato Anraku, and Jongwon Chon all gain the beach balls by jumping onto small dual tex volumes offering puny, textured “slab” patches, secretly oiled or buttered judging by the continuously skating shoe rubber. Then several no-hand leg presses off the unctuous beach balls, all finesse and body English on this “slow slab,” requiring glacial-speed moves and absolute trust in your feet. But no tops, till Hans Van Dysen shows us what champion slab climbing looks like when he ticks the slab second try.

Then Medji Schlack dashes from behind the iso curtain because he’s dashing like that and, face plastered to the wall, teeters, presses, and balances to the top the slab on his third try. Medji wails and pumps his fist, as before, but rather than race off, he saunters toward the curtain, his arms outstretched, palms up, like Napoleon after the Battle of Austerlitz. Medji’s worth the price of admission. The straw that stirs the World Cup drink. The crowd goes off.

Then comes Paul Gent, Medji’s ami prochet and longtime training partner on Team France.

“I’m happy to finally be in zee finals,” said Jenft, earlier in the day, “but I’m also frustrated because Mejdi always beats me. We’ll zee how it goes.”

Monsieur Gent, to the amazement of the beetling crowd, hikes the slab on his second try. Take that, Mejdi. No one else tops the slab. After two of four rounds, only Mejdi has managed two tops.

La Jolla Beach, nearby San Diego. Ricky Accomazzo and I are scraping over the 20-foot, salt-washed boulders girding Black’s Beach, renown for body surfing and nude bathing. Withal a swank bouldering venue for two kids still in high school. And Ricky and I were onto a masterwork, sporting an incut rail for our hands and a second, lower rail to kick off, all the better to sail sky high. And we’d need to since the next hold, a big hueco with a sandy lip, loomed a body-length higher. We both could huck the big pull-and-jump to the hueco, but with too much body swing to stick the latch, which sent us windmilling into the sand, face first and from way up there.

Then Ricky suggested we fire for the hueco with both hands, instead of one. Carving the air with hands and feet detached, to us schooled to “always maintain three points of contact,” felt frightening and illegal. So we tried it straightaway, and both quicky got it. Why not? Gymnasts had for decades thrown full dislocate moves on the high bars. But the first time we pulled a double mo on the rock, it felt like discovering fire.

The previous generation of Yosemite pioneers cast such long shadows, it felt almost impossible to bust into the light with something all our own. The double mo was where we stepped into the future—or thought we had. Imagine my surprise when I first toured Colorado with John Bachar, and later with Michael Kennedy for “Pumping Sandstone,” and encountered the Pinch Overhang, Left Eliminator (classic dynos at Horsetooth Reservoir), and the much harder fare down in Pueblo, where (c. 1965) a young math professor named John Gill started chucking double-clutch dynos when I was still pissing my pants in nursery school. Who knew?

Kokoro Fujii squirts liquid chalk onto his mitts, heaves off twin acorns and slaps for a sloper, clasps a middling lieback rill, winds up and launches into a run and jump, via rapid fire paddle dynos off dual-tex sidepulls, with sloped volumes for his feet. Once airborne, Kokoro-San must keep it going by swiping successive holds—rather like swinging across an off-axis jungle gym—and hucking at last for a final sidepull bolted twenty feet right of the launch point. Kokoro-San never gets close on the problem that is a microcosm of current World Cup bouldering, which just a few seasons back, resembled movements found at your local crag. But not so much any more.

Gym bouldering needed to create its own, spectator-friendly rodeo, including these fashionable run and jumps—all part of the charge toward dynamic aerobatics. Such problems borrow heavily from the wall runs and bar swings found in parkour, requiring great explosive power, and fantastic coordination and timing to pull off. Because training props and routines are so advanced, and World Cup climbers are so skilled and adaptive, route setters are forever concocting novel movements to defy the competitors and keep the journey fresh. The unspoken aim is to add some wrinkle to the standard repertoire of moves, keeping the whole megillah a contest of discovery, and a total blast to watch. But it ain’t easy dreaming up and setting those problems, to say nothing of climbing them. Believe it. It takes many years, and all their heart and soul, for setters and climbers to achieve a World Cup final. These pros earn their money.

Only Medji gets close to topping Problem 3, but violent body swing rips his hands off the final sidepull, and he helicopters into the mat and has to lump it.

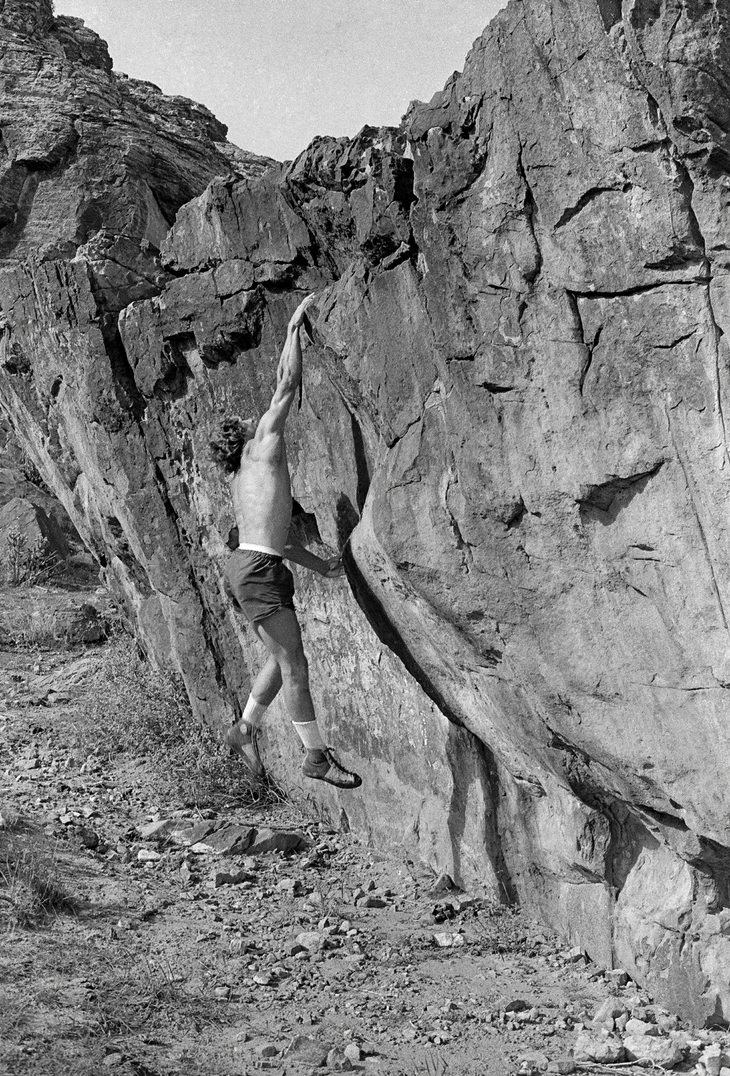

Three years after “Pumping Sandstone,” Canadian big wall pioneers Steve Sutton, Hugh Burton and I were exploring the dirt roads near Idyllwild, California—the small mountain hamlet below Tahquitz and Suicide Rock—when we rolled into Black Mountain campground and found ourselves surrounded by stunning granite boulders ten to forty feet high. Simply topping the hundreds of formations—which we started attempting right off—was the obvious first task, and I felt like Edward Whymper, c. 1890, peak bagging in the alps, though on a smaller scale, of course. A rope was never used because John Gill, we figured, would never have bothered with a cord. Not when he could highball. And Professor Gill could highball.

Following many exciting adventures at Black Mountain, c. 1980, I wrote “Pumping Granite,” which poured a little gas on the bouldering bonfire, and paid homage to two seminal Gill highballs I first encountered while pumping sandstone: the harrowing Thimble, which Ament described as “a 30-foot-tall, mitten-shaped pinnacle rising out of the Needle’s Eye pullout on the Needles Highway” (Custer State Park, South Dakota), and which, way back in 1961, Gill redpointed in lug soled boots, at 5.12a/b (when the hardest roped climbs were 5.10). And the punishing Gill Crack, at Castle Rock, in Boulder Canyon, a 30-foot, 5.12 finger crack that Gill soloed in the mid-1960s and which almost cost me two shattered legs (fat fingers are a liability up top).

Several years later, pawing up classic Black Mountain highballs like Moroccan Roll, Hank Panky, and Where Boneheads Dare, dynos, deadpoints, and highballs were standard practice, and presaged the current trends in both outdoor bouldering and indoor comps, where thankfully, cushiony mats soften the towering, out-of-control whippers often logged on the trampoline dynos for which World Cup Bouldering is renown.

The fourth and final problem features bulbous volumes set on opposite sides of a shallow, wickedly overhanging corner. Opposing, cross-pressured palms and dire stems might, it appears, install a mountaineer on the wall, rather like a clothes rack in a closet. But which way to face? In, or out?

Kokoro can’t crank it. Van Duysen can fly some, but not high enough. Schlack attacks but jacks his back attempting the clothes rack. The fourth problem goes unclimbed.

All told, six world-class boulderers have thrown down dozens of all-out attempts on four boulder problems, resulting in a paltry four tops. Mejdi is the only competitor to manage two. These problems are hard.

The women’s final had run the previous day but only appears on YouTube an hour after the men’s finals. Just time enough to pound another quad shot and two more Krispy Kreams as I watch American Brooke Raboutou, 22, with spectacular focus and authority, end up one hold shy of ticking all four problems. Austrian Hannah Muel takes home the silver, though the fräulein only manages one top. None of the four other four finalists top a single problem.

If a smile could translate into green money, Brook’s is worth a billion dollars. Her many friends—including announcer Matt Groom—shed tears for the Boulderite and her first World Cup gold.

The following weekend, in Seoul, South Korea, Brooke takes the bronze (all three medalists only manage 2 tops apiece), and Medji snags the gold once more. World Cup finals are nigh impossible to achieve, and any finalist can win on a given day. But going forward, Brooke Raboutou and Mejdi Schlack might well become fixtures on the podium.

Yet every insider wonders: what happens when Slovenian World and Olympic Champion Janja Garnbret returns from a toe injury, which should happen June 2, at the Prague Bouldering World Cup. Every sport needs a superstar, and comp climbing has Janja. Few champions dominate with Janja’s skill, fearlessness, and grace. Sixty odd years ago, when John Gill pictured a future bouldering hero, I imagine she looked exactly like Janja Garnbret. That a gang of up-and-comers are gunning for the Slovenian star is what makes World Cup climbing so enticing. But the soul of bouldering runs deeper than personalities or superhero moves on plastic or rock.

Back in the 1950s, legendary jazz trumpeter Miles Davis would start a recording session with nothing written down. No charts for the songs. Just a key and a few cord changes. He never told his fellow musicians what to play, only that they had to be working on something new. Some voicing. Some technique they wanted to make their own. Years later, Miles’ fellow musicians all had stories about those legendary sessions, when through spontaneous works of genius, they discovered the new and unexpected, and left us the best American music ever made.

Bouldering, like music that lasts, is not, finally, its medium nor its style; rather, something before, behind, above, and beyond all notes and all movement. None of us outlives our own time. What does is the magic of discovery, and what a climber becomes when it’s the air you breathe and the ground you cover. A sparkle silently passed on from John Gill to climbers of my generation, and which boulderers ever since have made their own, and dynoed to the stars.

Also By John Long:

EDITORS’ PICKS

The post True Fact: John Long, Stonemaster, is a Bouldering World Cup Junkie appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

The void swallowed him alive, his streaking form more easily imagined than described. The air froze in my chest.

The post Ripcord: A Story of Fame, Love, and Tragedy appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

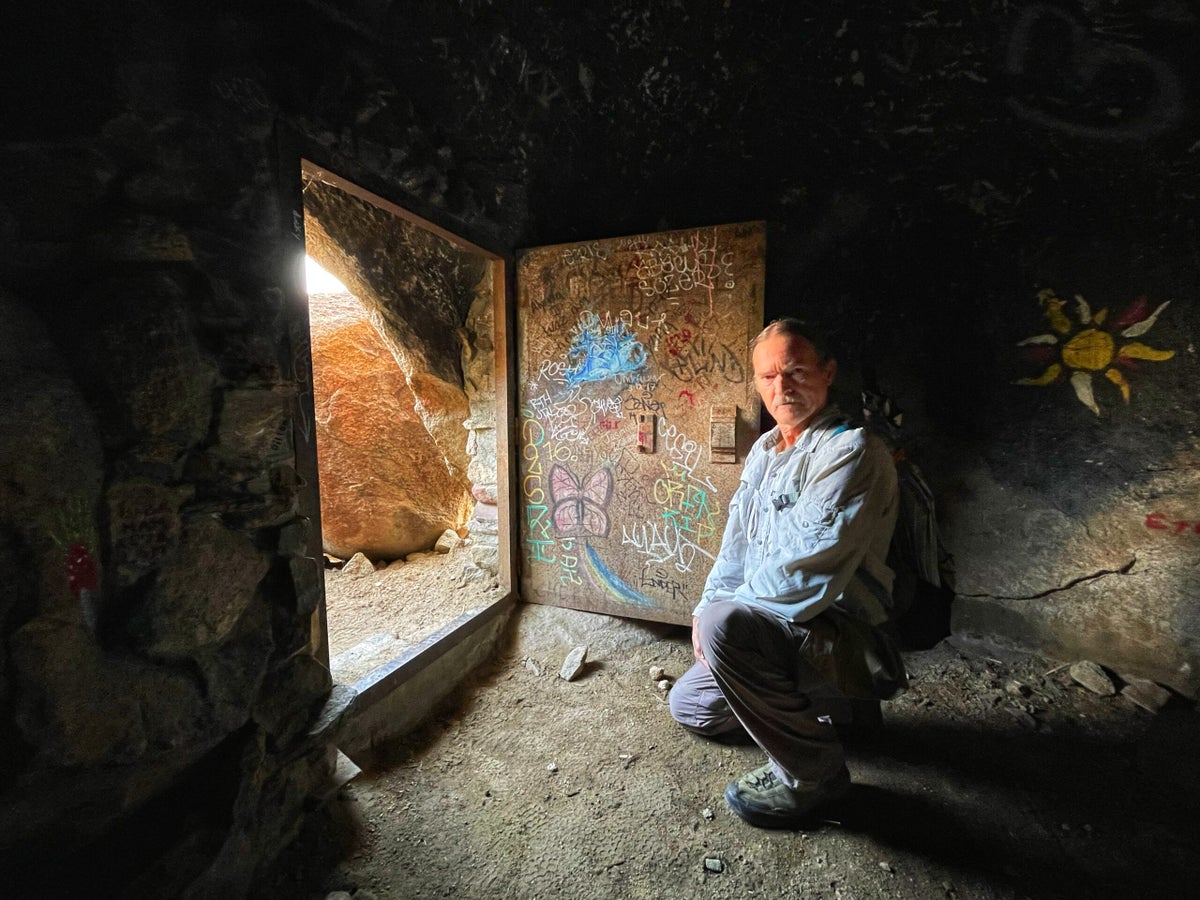

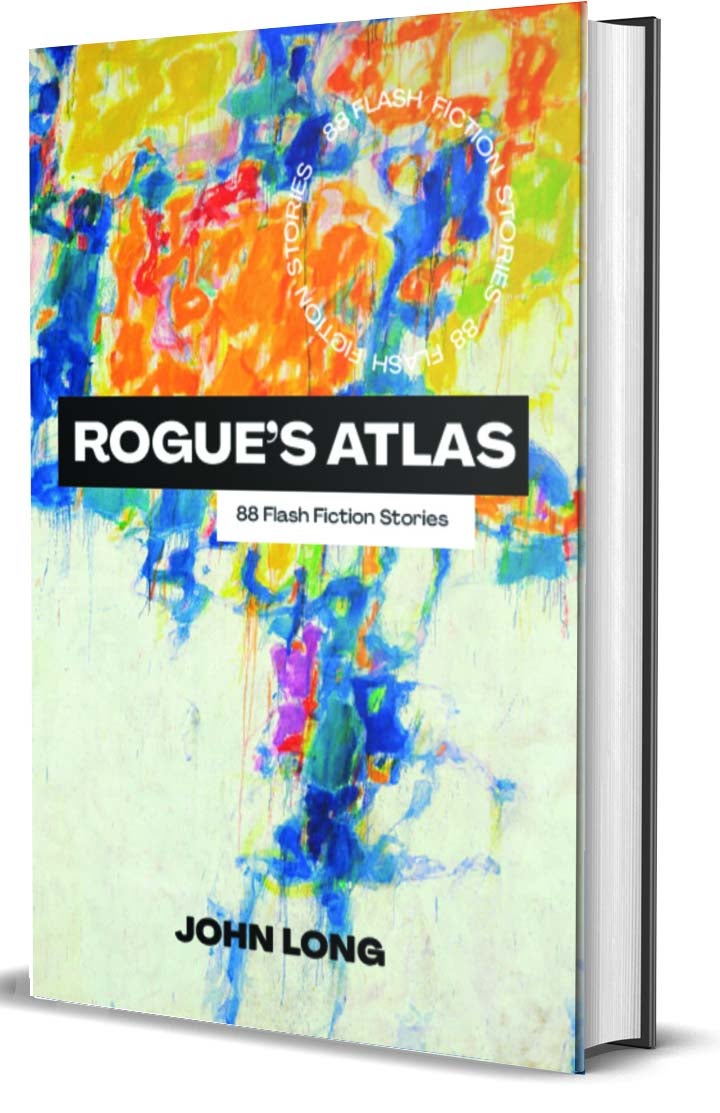

This feature first appeared in ASCENT 2013. This updated version has been excerpted from Rogue’s Atlas: 66 Flash Fiction Stories. Author John Long, Stonemaster, has written over 40 books, with nearly three million copies in print.

Yosemite Valley. Dawn. Mike Lechlinski and I are just stirring in our hammocks, lashed high on the granite face of El Capitan, when a whooshing sound shatters the silence. Louder, closer, building to a roar. Rockfall. Heading right for us: we’re dead. I instinctively brace for impact as two BASE jumpers streak over our heads at 120 miles per hour. It seems impossible that two falling bodies can make such terrifying, ear-splitting racket, like God is ripping the sky in half with his bare hands. We scream, craning our heads from our hammocks, our eyes following the jumpers plunging into the void. Their arms dovetail back as they track away from the cliff. The pop of their chutes fires up the wall like shotgun blasts. They swoop over treetops and land 50 feet into the meadow as a beater station wagon screeches to a stop on the loop road. The jumpers bundle their canopies, jog over, and dive into the beater, which quickly drives off. This last bit looks sped up, like a Roadrunner cartoon. If the rangers catch them in the act, they’re going to jail. We howl because we’re still there, still alive.

“I think I pissed myself,” says Mike. On a scale of one to a shitload, this sixty-second lark is off the chart.

In 1984, the adventure world caught fire and every serious player tried to blaze like hell. From our first sorties free climbing big walls to jungleering across Oceania, the mantra never changed: capture the burning flag. Our cousins in big wave surfing, kayaking, cave diving, and mountain biking were also charging hard, and we watched our group fever trigger the adventure-sport revolution. And the most visually dramatic show of them all was BASE jumping, the acronym for parachuting from a Building, Antenna, Span (bridge), and the Earth (cliffs).

A couple years after my close encounter on El Cap, I needed something bold to gain traction in the TV business, where I hoped to quickly score the trophy girls and crazy money. I was two months out of school, with a fistful of so-what degrees and a junker Volkswagen Beetle, determined to leave Yosemite behind. But secretly I didn’t so much wave at the train as grab for it, afraid of getting left behind.

British talk show maven and future Richard Nixon interviewer, David Frost, had a boutique production house with Sunset Boulevard offices. I hired on as a writer and associate producer, knowing zero about the television racket. The salary didn’t dazzle but my future glowed. We had several hour-long Guinness Book of World Records specials that we needed to style out with electrifying content. Previous episodes featured a dull parade of magicians, carnivorous spiders, and an English mastiff named Claudius, the world’s largest dog. I promised to hose out the dog shit, clean up the show, and boost the numbers. I knew going in that staging world-class adventures for television was sketchy, but so what. I was handy with danger and eager to debut BASE jumping on primetime national television. The plan felt like money. That left the tricky bit: collaring someone to do the jumping.

My immediate boss, Ian, smooth, sardonic, and classically educated at Eton, favored exciting acts. BASE jumping was one of several adventure pursuits, each riskier than the last, that I’d scribbled onto our dance card, and which the network, indemnified of responsibility, could promote to the moon. Ratings were everything, but in Jack Daniels moments Ian sometimes asked, “We’re not going to get anyone killed doing this, are we?”

“Not if I can help it,” I’d say.

The stars aligned and, in late June, I flew to London and joined Carl Boenish and his wife, Jean. Carl, 43, later dubbed “the father of BASE jumping,” was a free-fall cinematographer who, in the 1970s, had filmed the inaugural jumps from El Capitan, plus many other “first exits” off high-rise buildings, antennas, and bridges. For sheer burn and ebullience, Carl had few peers. Jean, nineteen years Carl’s junior, brainy, wholesome, and distant as polar ice, lived her life in a language I didn’t understand.

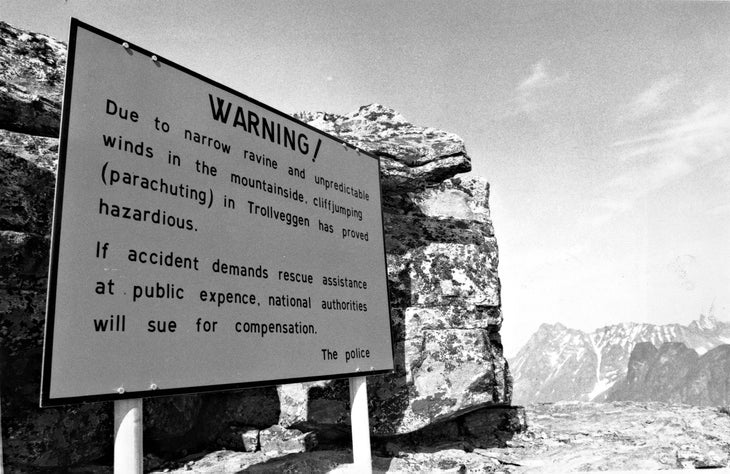

From London, Carl, Jean, and I flew to Oslo. The Norwegian airlines had gone on strike, so we packed six duffel bags into a rental station wagon and headed for the Troll Peaks in the Romsdalen valley, eight hours north. The narrow road meandered through still green valleys, dark as tourmaline, laced with alpine streams and glinting under the midnight sun. We stopped for beers at an inn (ginger ale for the Boenishes, who took no liquor), and I marveled at the year, 1509, chiseled on the stone hearth. Finally, we crept into the sleepy town of Åndalsnes, surrounded by misty cliffs, including the Trollveggen, Europe’s tallest vertical rock face, a brooding gneiss hulk featuring several notorious rock climbs and the proposed site for our world-record BASE jump. “Built when the mountain was built,” folklore says of Åndalsnes.

Carl and I breakfasted on pickled cod, peanut butter, and black coffee, and zigzagged up a steep road to the highest path and set out on a leg-busting trudge for Trollveggen’s summit. We were joined by Fred Husoy, a young local, among the finest adventure climbers in Europe, who knew the Troll massif by heart—critical in locating our jump site. We shouldered packs and trudged over shifty moraines toward a snowy col.

The first few miles climbed a glacial plateau, broken occasionally by lichen-flecked boulders and gray snow drifts that never melted, carved by wind into gargoyles and labyrinths. The lunar emptiness hadn’t changed in a billion years, and held the silence of the dead when the wind died down. It was so big and so blinding that even the birds felt lost in it, how they’d break the stillness and cry out. An elegiac keening that climbed to the ridgeline and broke. Another bird would answer. But the birds were not lonesome for each other. It was bigger than that.

From the moment we’d hit the trail, Carl hiked so slowly that I finally took his pack; but halfway over the big white plane, he once more had fallen well behind. Fred pulled on his raincoat against the drizzle, warning we had to hike faster or get blown off the mountain by afternoon storms. We slogged ankle-deep through a snowfield. When Carl caught up, wet clouds draped everything. No coaxing could make him hike faster. A little stone hut twenty minutes shy of the summit ridge offered a welcome roof from the shower. Carl limped in, collapsed, and pulled up a pant leg. Fred and I stared. Right above the ankle, Carl’s femur took a shocking jag, as if he’d snapped it in half and the bone had healed inches off plumb. I felt small and mean to have pushed him. How did a person hike at all with a leg like that?

“Jesus. When did that happen?” I asked. He’d shattered his leg in a hang-gliding accident several years back, said Carl, who clenched his way through a wonky exposition on natural healing.

“I don’t know, Carl,” I said. “A bone doc could surely fix that. It’s hideous.” Carl swished the air with his hand. Who needed doctors when God Almighty would set things right?

His fingers trembled as he pulled up his sock. It felt incredible and reckless to stake my future on a man living off stardust and voodoo.

A week before, we’d organized the venture at Carl’s house in Hawthorne, a small, L.A. suburb. From the moment I stepped through the door, Jean eyed me with steely reckoning, as though if she glanced away I might pilfer the china. Her clothes looked Mennonite-plain, the house, immaculate, all cups and chairs and handcuffs in their place. Nothing admitted she and Carl dove off cliffs for a living. As Carl raked through his garage, overflowing with gear, he’d bloviate about St. Peter, Coco Joe, or whoever. Without warning, Carl would dash to his piano and butcher some Brahms or Brubeck, then jump back into conversation, randomly ranging from electrical engineering to terracotta sculpture to trampolines and particle physics, galvanized by a screwy amalgam of new age doctrine and personal revelations. Often, he would heave all this out in the same sprawling rant. Ian thought he’d dropped acid. But Carl laughed so loud and burned so hot I found myself giddy by the inspired way he met the world. We lived in different keys, but we both craved the intimacy of risk. And in the fellowship of adventurers, folks like Carl Boenish drove the bus.

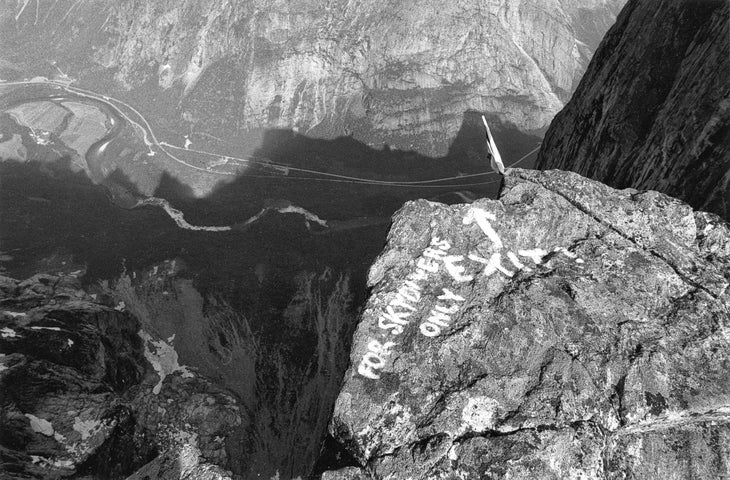

Outside our little stone hut in the Troll Peaks, the shower slacked off and we continued over snowy slabs toward the mile-long summit ridge, all dark clefts, precarious boxcar blocks, and pinnacles digging into the sky, so twisted and multidimensional, M.C. Escher couldn’t have drawn it in his dreams. The wall dropped 6,000 feet directly off the ridge and into the Trondheim valley. The rubbly slabs angled down behind us to the high glacial plateau, where perpetual snow framed a tiny lake glowing aquamarine. Black-and-white clouds gathered, masking the ridge, cutting visibility to several hundred feet and making it difficult to navigate. Without Fred’s knowledge of the labyrinthine summit backbone, we would have wandered blind. The clouds parted and we lay belly-down on the brink, sticking our heads out over the immediate, sucking drop. Carl rubbed his leg, laughed, grimaced, and laid out his requirements.

The wall directly beneath his launch must overhang for hundreds of feet, he said, long enough for a plunging BASE jumper to reach near-terminal velocity. Only at top speed, when the air became thick as water, could his layout positioning create enough horizontal draft to track and fly out and away from the wall (the now-ubiquitous wingsuit wouldn’t be invented for another dozen years) to pop the chute, as Mike and I had witnessed on El Capitan. The new parachutes didn’t simply drop vertically, but sported a three-to-one glide ratio—three feet forward for one foot down. But twisted lines could sometimes deploy a chute backwards, wrenching the jumper around and into the cliff.

“Here, that would be fatal,” said Carl with buggy eyes, peering back over the lip.

The most prominent spires along the ridgeline were named after chess pieces. Out left loomed The Castle, a striking, 200-foot-high spire canting off the brink like the Tower of Pisa. An exit from the summit, hanging out over oblivion like that, had to be safer than leaping straight off the summit ridge, making it an obvious feature to scout.

Carl hung back as Fred and I tied on a rope and scrambled up the water-logged Castle to the top—a flat and shattered parapet, perfect to start our rock tests. We wobbled a chair-sized boulder over to the lip and shoved it off. Five, six . . . Bam—a sound like mortar fire. Debris rattled down for ages.

“No good,” said Carl, yelling from the ridgeline. “Way too soon to impact.” We tried again. This time, I leaned over the lip and watched a second rock whiz downward, swallowed in fog 300 feet below. Three, four . . . Bam! My head snapped up. There had to be jutting ledges mere feet below the fog line. We shoved off more rocks and kept hearing the immediate, violent impact of stone on stone. “Forget it,” Carl yelled. “The Castle will never do. It’d be crazy.” The flinty smell of shattered rock wafted up as Fred and I rappelled off the pinnacle and joined Carl.

For another hour we continued with the rock tests, at successive points along the rubbly brink. Trundling rocks off most any other cliff could kill people. Not there. Any climbers on the wall and we’d have known about them. And below the towering upper wall spilled a massive, low-angled slab, terminating in a sprawling moraine field where nobody but climbers had reason to go. The menace, though huge, was strictly our own. All around us loomed forces and forms so elemental they had never organized into life, so nothing native to this place could even die. But we could. That’s what made it so heady to try and sort this out. But each rock we shouldered off dashed the wall within seconds. Lightning cracked off the lower ridge and we ran for the valley. Carl hobbled behind.

Norwegians are a handsome race, normally demure, until you pull the cork on Friday afternoon and the dritt hits the vifte. That night, all the young locals in town crammed into the pub in the hotel’s basement, where we drank Frydenlund like mad, chased it with beer, and danced to The Who. Several gallons in, a tall brunette with a stylish bob grabbed a handful of my shirt. She acted more curious than courageous, and couldn’t find the words. So I trotted out the one Norwegian phrase I had memorized from a handbook in my room: “Hvorkanjegkjøpe en vikinghjelm?” (Where can I purchase a Viking helmet?)

“Are you a Viking?” she asked in flawless English. I said I’d try to be one for her, and she said, “You will marry me.” That night I saw eternity and it looked like this: a girl and a boy dancing in a crowd on an unswept floor in a bar on a thousand-year-old street.

Aud came from the next town over, and worked some dreary retail job in Åndalsnes during summer break from nursing school. We spent our free time together, and I learned there are moments where nothing is so grim as being alone. I usually went it alone, a shark who survived by staying in motion. Until Aud drew the restlessness from me like a thorn, and light leaked through a soul cracked open. Over the next month, as we got the jump site dialed and waited for good weather, I was either with Aud or imagining her.

The next day, as Carl recovered in his hotel room, Fred and I slogged back to the summit ridge for our first of many recons, trying to locate a viable launch site. The existing world’s longest BASE jump, first established three years before, exited the ridge well east and some 400 feet lower than the Castle. That left us to scour the chaotic, quarter-mile-long ridge between The Castle and the old site—a confusing task for sure. Over the following weeks, when we weren’t kicking around the Trollveggen’s cloudy ramparts, Fred and I would snag Aud and go bouldering on huge, mossy erratics, or hike up spectacular peaks or along jagged ridges snaking through the sky. I was 26; Fred and Aud were in their early 20s, all of us novice adults, searching for where we fit into the world. For a weightless moment, we shared an enchantment. Twice more, Fred and I explored the summit ridge, ever dashed by hailstorms.

The rain, meanwhile, kept washing our budget into the talus, and my inability to locate a jump site was wearing us out. Norway completed our production schedule, and the crew looked toward holidays in Paris, the Greek Islands, or home. We had to get this done. On the ninth scout, after a nasty piece of scrambling and several tension traverses on crappy rock, we located the highest possible exit from the ridge: The Bishop, to use the old chess name. But again, we got weathered off before we made our rock tests. We returned early the next day and, lucky for us, the sky shone all blue distance, the entire ridge fantastically visible and spilling down on both sides for miles. After weeks spent wandering about in the fog, it felt like a vision from the Bible, the entire rambling cordillera unmasked before us. We definitely were on the apex, walking unroped on an anvil-flat, 10-by-50-foot ledge that terminated in an abyss as sudden and arresting as the lip of the Grand Canyon. If the rock tests checked out, we were halfway home. The easy half.

I lashed myself taut to two separate lines, bent over the drop, and lobbed off a bowling-ball-sized rock while Fred timed the free fall. The rock accelerated ferociously and dropped clean from sight. Twelve, thirteen . . . I glanced over at Fred and smiled. This could be it. Seventeen, eighteen . . . BANG! A faint puff of white smoke appeared thousands of feet below. That rock had just free-fallen three quarters of a mile. No question, The Bishop was our record site. Fred pointed out the original launch spot (or exit site), still far left and 300-something feet below. I chucked another rock and we watched it shrink to a pea and burst like a sneeze near the base, the echo volleying up from the amphitheater. I tried to imagine strapping on a chute and plunging off, but couldn’t. And I couldn’t yet imagine ever climbing this towering heap.

From a distance, Trollveggen looked classic, a 2,000-foot-high talus slope topped by a 3,600-foot rock wall. At its steepest, the summit ridge overhung the base by 160 feet. Up close, however, the greatest rock wall in Europe was all fractured statuary, a vertical rubble pile top to bottom. And so utterly, unspeakably other, neither alive nor dead. It simply was, somehow, and it spooked me more by the day and the week.

We ascended our fixed rope, reversed the traverse and, as the first raindrops fell, Fred and I hoofed it to the valley with the good news.

For the next five days, Aud, Fred, and I stayed glued to the Oslo news channel, frequently stepping outside and glancing through thundershowers for some providential patch of blue. Mostly we milled around the production HQ in the hotel basement, living off chocolate scones and espresso. Helicopters stood on standby, film cameras were loaded, every angle reckoned, logistics planned to the minute. Meanwhile, journalists throughout Scandinavia streamed into Åndalsnes. The local paper ran full-page spreads in a town where the breaking news trended toward a farmer hooking a record lunker in a secret stream. When approached and pried at, Carl would laugh and let fly his exotic babbling as journalists nodded and smiled but took no notes. Finally, Jean—normally so laconic she might have been mute—would answer with several cold facts and figures.

A celebrated Oslo stringer, newly arrived, cited previous BASE jumping accidents and questioned something that had every official chewing their nails. As starry-eyed admirers gathered to touch Carl’s jumpsuit, she all but screamed that the emperor had no clothes. The glossy hype and big money spent was nothing but a made-for-TV flim-flam in the service of a maniac who, by the sound of him, had flunked kindergarten and had little regard for his own safety. The worry on her face and edge in her words betrayed her annoyance that The Jump had a gravity even she couldn’t escape. None of this was simple.

We slunk around. Rain fell in sheets. Tension mounted. With all the media hoopla, all the delays, each emerging detail raised the story’s sails sky-high. Norwegian television ran nightly updates. The big Oslo station sent a video truck. With a week’s momentum, the production took on the pomp and blather of Hollywood—precisely what I’d hoped to avoid.

Several journalists took to quoting Carl directly. The translation to Norwegian vexed (“like Ted Hughes on peyote,” Ian suggested), the waiting game somewhat relieved by trying to guess what the hell Carl had said. The sky growled at us. Scandinavia stood by. Each day in limbo meant thousands of dollars lost to feed, liquor, and house the crew. This quickly morphed into an impatience for what required steadfast deliberation. Throughout, the Boenishes were ready to jump. At 8 p.m., July 5, 1984, the weather broke.

Everyone scrambled, desperate to shoot something, even in bad light. In two hours, cameramen choppered into position. The helicopter dumped Carl, Jean, Fred, and me into a small notch 40 feet from the launch site on The Bishop. This avoided having to wheedle the Boenishes across the traverses, fitted with fixed ropes, that had given Fred and me fits owing to loose rock. Carl pulled on his flaming red jumpsuit and paced around like someone waiting for the electric chair. Jean began assiduously studying the launch site. I pitched off a rock that whistled into the night. Other rocks followed to verify my estimates, but disclosed another hazard.

“Sure, they drop forever,” laughed Carl, “and that’s a good thing. But they’re never more than ten feet from the wall.” That left no margin for error. If they couldn’t stick the perfect, horizontal free-fall position, if they carved the air even slightly back-tilted—head higher than feet—they could possibly track backwards. Carl demonstrated with his hands, one hand as the wall, the other for the jumper. When his hands smacked together, Fred and I jumped. Jean, cool as the Romsdal Fjord, rolled more stones toward the lip. The light faded to a gray pall. Far below, the great stone amphitheater swallowed the night.

The radio coughed out: “Come on, mate, let’s get on with it!” The crew was freezing and the director of photography feared it would quickly get too dark to film.

“Hey,” said Carl, lucid as water, “I can’t be rushed to jump off this cliff, screaming past those ledges at midnight.” I quoted this word-for-word into the radio, and the crew backed off. They’d planned to jump in tandem—Jean first, followed closely by Carl—but for this run-through, Carl chose to huck a solo jump while the cameramen previewed and assessed the angles. The sun, at the wee hours, was too dim for full glory, but a practice jump could help the cameramen dial in the details. The sky, though darkening, remained clear and flawless so, with some luck, the good weather might hold. After Carl’s trial jump, we’d resume in a few hours, when full light returned.

Carl strapped on his parachute and I tried to capture his kinetic energy on film. But I couldn’t pull a focus in the gloom. I packed away the Ariflex, grabbed a still camera, and turned to the drama before the jump.

“Ten minutes,” said Carl, bug-eyed, jaw working, hands fidgety. Jean helped Carl with the last straps. Cued by days of front-page spreads, the road below swarmed with cars and people, headlights winking in 1 a.m. gloom.

“Five minutes,” said Carl.

He pulled some streamers from his pack. Leaning off the ropes, I lobbed them off. No wind. They fell straight toward the base, shrinking to a blur. Everything looked go.

“One minute,” said Carl, his voice high and tight. He cinched his helmet and slid twitching fingers into white gloves. I pitched off a final rock and Carl tracked it, visualizing his line.

“Fifteen seconds.”

Carl unclipped the rope and stepped over to the lip. Horns sounded below. I was tied off to several ropes, my feet on the edge, with a panoramic view for the ages.

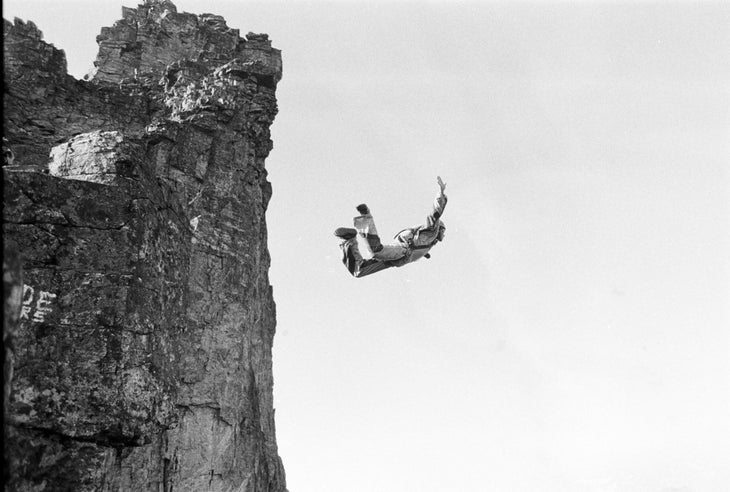

Carl’s shoes tapped like a rhythm machine, eyes unfocused. He started his countdown, which Fred mimicked into the radio: “Four, three, two, one!” And he was off. Watching someone jump straight off a cliff like this is so counterintuitive to a climber’s instincts that Carl might as well have jumped into the next world. The void swallowed him alive, his streaking form more easily imagined than described. The air froze in my chest.

After a few seconds, Carl’s arms went out to stabilize, his legs bending and straightening while his jumpsuit whipped like a flag. With roaring speed, Carl passed several ledges with 10 feet to spare, body whooshing, ripping the air with a violent report. After 1,000 feet, his arms snapped to his sides as he flew horizontally away from the wall, tracking 50, 100, 150 feet, at 120 miles per hour, a swooping red dot. Thirteen seconds, fourteen, fifteen . . . Pop! His yellow chute unfurled big as a circus tent, and he glided down, over the slab and moraine field to the meadow. The picture-perfect jump.

Fred and I crabbed back from the lip, gaped at each other, and howled. Some called Carl an idiot for risking his life over something that didn’t matter; but we’d just watched him rogue fear with imagination, and dive into the unknown. And if that doesn’t matter, nothing much does.

Back at the hotel at 3:30 a.m., the chaotic crews, gnashing producers, frantic journalists, film loaders, battery chargers, pilots, and hangers-on, all guzzled espresso and ducked out to check for clouds, everyone anxious to film the jump and clear out. A chartered jet sat gassed and awaiting the crew once we finished filming, hopefully by noon. At 4 a.m., I laid down with Aud for a short nap, but couldn’t settle for all the caffeine and apprehension.

At 6 a.m., two helicopters ground up through Persian blue skies and deposited us on The Bishop. Half an hour later, after some rock tests, and rechecking their rigs, the laces on their shoes, the film and batteries in their helmet-mounted cameras, Jean tiptoed to the lip, with Carl inches behind her. I stood five feet away, lashed to a rope, toes curled over the brink, shouldering a 16 mm film camera. 100 feet straight out in space, the helicopter yawed and hovered like a dragonfly. Fred gave the order to roll cameras. The Boenishes stepped off the lip and dropped into the void. Jean later wrote:

Eyes fixed on the horizon, I raise my arms into a good exit position. Then from behind, ‘Three! Two! One!’ For an instant my eyes dart down to reaffirm one solid step before the open air. Go! One lunging step forward and I’m off, Carl right on my heels. Freedom! Silence accelerates into the rushing sound as my body rolls forward. I quickly realize that the last downward glance has been an indulgence now taking its toll, for I roll past the prone into a head-down dive, which takes me too close to the wall. The first ledge is rushing towards me as I strain to keep from flipping over onto my back.

Through the viewfinder I watched Jean dive-bomb and slowly cant over onto her back. I panicked and ripped away the camera as she plummeted, her toes nearly brushing the first ledge.

“Holy shit!” Fred yelled.

Jean somehow arched back to prone, her hands came back, and the duo swooped away from the wall, shrinking to colorful specks, still flying, 200 feet out, still free-falling.

Their training, from thousands of skydives and hundreds of BASE jumps, steered them down the face. But watching the pair, as they streaked toward hungry boulders, stopped my heart.

“Pull the chute!” I screamed. Sixteen seconds, seventeen: POP! POP! A world record, no injuries. Cameramen raved over the radios. Newsmen and bystanders swarmed the Boenishes after their pinpoint landing. The world toppled off our shoulders.

Fred and I were done, and drained. Nothing but smiles, chocolate strawberries, and champagne back at the hotel. Ian and I both thought we had a shot at an Emmy with this one, and my career in television glowed. Aside from the delays, the jump had gone exactly as planned, but the crew scrambled to pack and leave on the charter. Ian was so worried about an accident that he rushed to clear out lest something happen retroactively. That afternoon the charter jetted for London, and those left behind, including half the kids in Åndalsnes, moved to the bar in the hotel basement, where several storylines began to converge. I could never have guessed where this junket was about to take us.

A Norwegian named Stein Gabrielsen and his fellow countryman Eric (last name unknown) had arrived in Åndalsnes only hours before. I met them in the bar, thinking they were another two Euro BASE jumpers drawn there by the big news, now splashed across Europe. In fact, while Fred, Carl, and I had begun scouting Trollveggen’s summit ridge, Stein and Eric (both working in America, and unaware of our plans) had purchased one-way tickets to Norway to attempt the world-record jump off the Troll Wall, something they’d planned for three years. They would have gotten the record, too, except they’d gone on a ten-day bender the moment they met with friends in Oslo. When a girl showed Stein the newspaper story about how Carl and Jean were already in Åndalsnes, waiting for the clouds to lift, he and Eric bolted directly, arriving in town late that evening.

They walked to the base of the Troll Wall, still glowing under the midnight sun, both men eager to scope out their record site. That’s where they met “a drunk old Norwegian dude” who pointed at the dark cliffs and said, “That is the Devil’s mountain.” They walked back to town and spent their last krone on beer at the pub, where several dozen of us were finishing our wrap party, a Hollywood tradition. I remained the final holdover from the American production crew, there to settle accounts and hang with Aud. Stein and Eric, both flat broke, joined the bash only to learn the Boenishes had scooped them by a few hours. At best, they might repeat the record—the adventure-sports version of an asphalt cigar. Their consolation was the $500 of production money I had left to blow on booze.

“Eric and I found Carl,” said Stein, “congratulated him, and asked about his launch site.” Carl said he jumped from The Bishop. Stein had surveyed the ridge and believed The Castle stood higher. “Check a chess set,” said Carl. “The Bishop is always taller than The Castle.” “Either way,” said Stein, “Eric and I are jumping The Castle tomorrow.”

“Carl became visibly nervous,” Stein later wrote, “and suggested we meet at their hotel for breakfast next morning, around 10 a.m. Then we could go jump together.” A free meal sounded good, so Stein and Eric agreed. We closed the bar and half-mashed on Aquavit; Aud and I staggered to her apartment and I passed out for twelve hours.

The following morning, Stein and Eric met Jean at the hotel. Jean said Carl was in town, arranging their travel back to the States, and she invited the pair to breakfast. An hour passed and still no Carl. Jean kept glancing at her watch, out at the driveway, back at the map of Trollveggen hanging on the wall. Jean said she was sorry. She’d deceived them. Carl had been afraid they would usurp his record (as The Castle is higher on the ridgeline than Carl and Jean’s launch site on The Bishop), so he’d left at sunrise to go jump The Castle. Jean figured he had already jumped and was at the landing field, waiting for a ride. She suggested Stein and Eric take the rental Volvo, snag Carl, and head back up to The Castle for round two. Jean needed to pack. Stein and Eric had gotten snookered and sent to fetch the culprit. One can imagine their conversation as they drove to the landing zone in the big meadow, to talk things through with Carl Boenish.

Back at Aud’s apartment, I sorted gear for a one-day, racehorse ascent of the Troll Wall. I’d changed my mind a hundred times, but couldn’t blow off Europe’s biggest cliff when it was right down the road. A quick rap on Aud’s door. It flew open and Fred rushed in.

“Carl’s been in an accident,” he said, “and it looks bad.” A car accident? No, said Fred. Early that morning, Carl had hiked back up to Trollveggen and jumped off The Castle. That couldn’t be right. After the last two days tromping around, Carl would be resting his bum leg for sure. Our production had caused such a stir that, for going on a week, jumpers like Stein and Eric continued streaming in from Sweden, Iceland, Denmark, and beyond. Any accident was theirs, I said, not Carl’s. Fred shook his head. Carl had enlisted two teenage brothers, both local climbers, to hike him up. One, Arnstein Myskja, had witnessed Carl’s accident and stood there next to Fred, trembling in his boots.

Ten minutes later, I was dashing across peat bogs, seeking a vantage point with the lower Troll Wall in clear view. I frantically glassed the lower face, nearly a mile away, finally spotting Carl’s big yellow parachute, unfurled and breeze-blown on a shaded terrace near the base.

“Goddamn it, Carl. Get up . . . signal . . .” The canopy billowed gently from the updraft. “Carl!”

Fred arrived and put a hand on my shoulder. Carl hadn’t moved. I followed Fred to a grassy field surrounding the grand manor of an expatriate British lord. A pall tumbled from gray clouds as the media streamed in, occasionally stealing glances our way. My center could not hold much longer.

The police chief arrived and I couldn’t meet his eyes when I told him I’d spotted Carl on a ledge near the base. The part about no movement ended our conversation. I didn’t have the courage to call Jean, but the chief did. Barely. Tears flowed from his eyes though his voice remained calm and stoic. I will never forget his face as he talked with Jean.

“I . . . regret to inform you that your husband has been in an accident, and it doesn’t look good.” This last detail took enormous bravery to admit. Jean’s voice sounded eerily detached over the speaker phone, soberly seeking details as every soul in Åndalsnes bore the chaos on her behalf. I stormed outside and pulled on my harness. Nobody knew if Carl was dead, or even seriously injured, and I yelled as much, confronting some with the news. They nodded slowly and shrank away, huddling under trees, waiting.

The whop, whop of the giant military rescue chopper thundered up the valley. It landed in a clearing, arching trees, buckling photographers, scaring all with its powerful thumping. Fred went and I stayed behind, shivering in my t-shirt and glaring up into the rain. Aud came over but I couldn’t talk or look at her. I thought about nothing, vaguely hearing the chopper’s hammering pitch in the distance. It set down and the crew filed out, staring at the ground. Fred walked over, his face hard as stone. Six photographers clicked shots as we fled back to the lord’s house.

As a free citizen, Carl could do as he pleased, but The Castle? I yelled. Carl himself had called the site crazy. The doctor, little more than thirty years old, requested that I go aboard to identify the body. “For what?” I begged. The doctor stared at the floor. The ordeal was far from over, and spared nobody. I felt like the Ugly American who had barged into a quiet little town with a small army and a wad of television money and broke every rule and every heart in the place.

We walked through wet, knee-high grass toward the ship. Amber light glinted off new puddles. How dare beauty show itself when Carl was dead? We moved through the chopper’s huge rear hold and back to Carl’s body, looking as though he’d laid down to get a load off that leg. No sign of regret on his face. The young doctor and I stood there, mourning a life cut in half, gazing from death as if unhurt. But he’d screamed a music too high to scale, and the cold mountain got him. The distance Carl had tracked away from us brought back the birds and their keening, high on the glacial plateau.

I joined the crowd gathering on the grassy field, everyone gazing confusedly at each other. Someone had to know why and how come. We watched the coroner and two policemen heft Carl’s black-bagged body into a white van and roll off into the mist. It felt criminal to leave it at that; but Carl could not die again. That was all. The end.

Fred and I silently drove to Aud’s place and I wandered in a traceless land. Even Aud couldn’t help me now. Why had Carl jumped from The Castle? I’d never felt such helpless confusion, and could have killed Carl a second time.

That evening I went and found Arnstein who, along with his younger brother, had guided Carl that morning. It had taken them nearly five hours to short-rope (drag by a tethered line) Carl over the glacial plateau and up to the top of The Castle. Carl conducted rock tests and, in seconds, as before, they smashed off outcroppings jutting directly into the flight path. But Carl was determined to go. Arnstein grabbed his camera. As he described to me and others, Carl was dead the moment he launched off the lip, or tried to. On his last exit step, he stumbled and, unable to push off and get some little separation from the wall, he frantically tossed out his pilot chute. With so little airspeed, it lazily fluttered up, slowly pulling his main chute from the pack. One side of the chute’s chambers filled with air and flew forward. With one side deflated, the inflated side wrenched the canopy sharply, whipping Carl around and into the cliff.

He continued tumbling, said Arnstein, his lines and the canopy spooling around him like a cocoon. 5,000 feet later, Carl’s tightly wound body impacted the lower slab “and bounced thirty feet in the air like a basketball.” Arnstein was so sickened by what he’d just shot on his Nikon that he yanked the film from the roll and tossed it into the void, so the images of Carl’s last moments were lost forever.

A few days later, Jean hired several local climbers to hike her up to The Castle, where she checked the site firsthand and did what a wife does where her husband has died. Then she traversed the ridge to the original, 1981 launch site, jumped off and touched down for a perfect meadow landing.

I couldn’t sit and kept pacing around Aud’s tiny apartment. For several weeks, I’d agonized over leaving Norway without her—a puzzling concern for a nomad like me. But life kept shifting. TV work stretched off like a cargo cult runway, inviting a rich future to appear. Then Carl crash-landed and it felt likely I was one and done with production work. Staring at the white stucco walls in Aud’s matchbox, I couldn’t see any future at all. I don’t recall saying goodbye to Aud and Fred, but I must have. I only remember driving through the dark dawn shadow of Troll Wall, heading for the airport in Molde, the giant cliff felt but unseen for all the clouds and rain.

Over the following decades, Carl and Jean’s Norway jump became a seminal event in BASE jumping’s short history. Several magazines ran feature articles on the couple, but they’d taken a novelist’s wand to Carl’s accident, and I couldn’t read them through. I wasn’t surprised when a producer called about a feature-length documentary on Carl, now in production, and asked if I might fly over to Åndalsnes and do an interview. Time had worked the sharpest edges off Carl’s death, and a trip to Europe sounded excellent. I found myself back in Norway a few months later.

The Trondheim Valley, and that towering junker, Trollveggen, were far more daunting than I remembered—which wasn’t much. Åndalsnes had modernized but still resembled a sub-burg of Camelot. My feel for the place had gone. Thirty years can blunt the sharpest memories. Mix in drink, work, a failed marriage, and it’s a miracle I remember anything. Fred and I reunited and immediately went bouldering at the old haunts—the mushy fields and cow pies, the scabby orange lichen on the rock, gaping up at the monstrous Troll Wall, “doing the joking” as we floundered on short climbs we’d once hiked with ease. The memories stirred. I talked to Aud on the phone and her voice pulled me back. But I still felt lost as the birds on the glacial plateau.