Why a climbing trip without a significant other was an important progression for me as a female climber

The post On My “No Boys Allowed” Climbing Trip, We Did Everything Wrong. It Was So Worth It. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

The whisper on camp was that we had to be lesbians. Zofia Reych and I struggled with our tent poles and pounded the stakes into the ground with rocks as nearby campers lounged. The expansive gray Swiss mountains loomed behind.

It was 2014, and we were the odd ones out—the only group without a man. We ignored our onlookers. Admittedly, going on a trip without my boyfriend did make my stomach swirl—I was shy and I’d often let him take the lead. But we were determined to leave our male counterparts behind.

Two weeks earlier, feeling cooped up as students in London, Zofia and I both had a week off and mischief to get up to. Following rumors about a world-class bouldering area in Switzerland reachable by train, we booked tickets for our first no-boys-allowed trip to Magic Wood.

Planning was simple, but packing proved mysterious. In the past, my boyfriend had always packed for us both. In a whirlwind, I threw what seemed sensible into my crashpad-cum-suitcase: canned food, a tiny camp stove, clothing, and climbing shoes.

To save money, we had booked a room at the Swiss Star Apartments in Zurich within “walking distance” of the train station. As broke students, we forwent buses and taxis, walking three kilometers with our crashpads and bags to save money. Not a pinch of doubt crept into our heads hours earlier as we stuffed our two bouldering pads full of canned food and wrapped them with plastic wrap so they would close. The downside? They proved nearly impossible to carry.

While swapping trains, we decided it would be a good idea to shop for more food since we were heading into the mountains car-less and it was a 30-minute hitchhike back to town. Four Aldi shopping bags later and armed with our two provision-stuffed pads, we caught the last bus to the sleepy village of Ausserferrera, home to Switzerland’s popular bouldering area.

From the campsite, we could see the sharp edges and bullet-hard rock of the closest bouldering area just across the road. Jittery with psych, we pitched our tent. As we settled in and prepared to dig into our canned rations, we realized a small but crucial detail had slipped our minds when Zof asked me, “Um, where’s the lighter?”

“It doesn’t matter,” I said, “because we forgot to bring gas.”

Our mishaps piled up. We didn’t consider that the campsite wouldn’t have a fridge (campgrounds often have fridges in Europe). We hadn’t checked in advance. So we soaked our food in a water trough filled with glacier run-off for washing and a tap for drinking. We munched on spoonfuls of Ovaltine spread and cold canned sardines in silence. But we had made it, and that was enough.

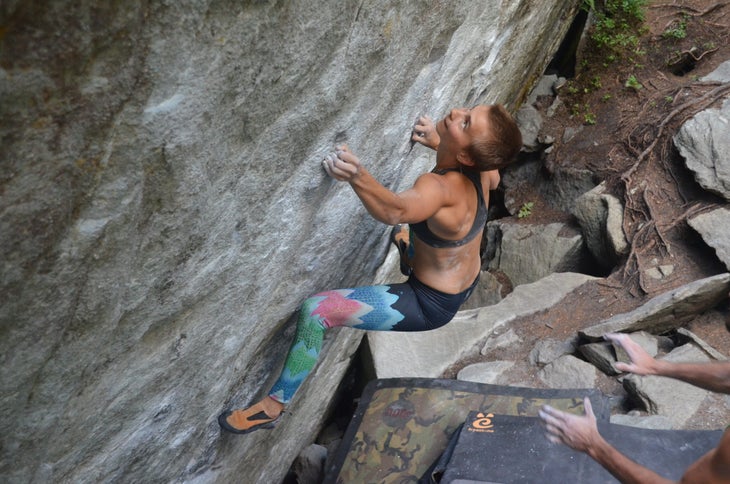

In the morning, my muscles screamed. Our plan had been zero rest days, but I was already sore—just from carrying the heavy, awkward pads. But we were determined to be tough, so we set out to boulder, chanting: “No pain, no gain.” We worked our way up the grades, trying 7A-7B (V6-V8) classics like Mörderballett, a confusing technical arete; Enterprise, an exciting heel hook traverse; and Grit de Luxe, the crimpy slab next to the creek. We set our sights on a few projects: Intermezzo, a steep sharp crimped 7C (V9) and Blown Away, a 7B (V8) highball traverse.

Throughout the week, we found our groove. On rest days, we walked to the nearby cafe, Bodhi’s lounge. It never seemed to be open, so we made a routine of hanging out in the parking lot instead. Once we acquired gas, we brewed our morning coffee on the concrete, being careful not to topple our tiny three-prong Decathlon stove … again.

We skipped showers and swam every afternoon instead. Our motto was: “A 7A a day keeps the doctor away.” We kept that doctor in check … until we didn’t. One strained knee ligament for me and one finger injury for Zof later, we decided to rest—by that I mean tape up and keep climbing, of course.

Despite our camping and climbing faux pas, that week provided some of the best climbing memories of my life. There was no one to answer to, no one to tell us what to try. Climbing had never felt so free. I didn’t care that I walked away with a swollen knee. It was the first time climbing didn’t feel like something I was passively partaking in—it was something I chose. Climbing became my own. And we did choose. We picked out our projects, got up late, stayed up even later, screamed on a send, and giggled as loud as we liked.

Looking back, I remember the tension in my shoulders and the murmurs of worry in my head before our trip. I didn’t know if we could handle it. But our mistakes turned into memories. Our mishaps ultimately left us empowered. Our blunders brought laughs. We were happy to have them, because those gaps of wisdom, now filled, inspired many independent adventures ahead. We were proud, not worried, to be the talk of camp. From then on, we did many trips solo and without the “boys.”

We made a lot of mistakes on our first solo bouldering trip, but we didn’t care. That’s what climbing—and life—is like. Making mistakes, taking ownership, and in so doing, making something of your own.

The post On My “No Boys Allowed” Climbing Trip, We Did Everything Wrong. It Was So Worth It. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Why this popular climbing training method doesn’t work for everyone

The post For Me, Fall Practice Was Bad Advice appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

In the fall of 2018, I stood at the base of my current project: a 12a on a gray-brown cliff looming over the highway at Arizona’s Virgin River Gorge. Not even six months earlier, I had breached 5.14. But since then, everything had changed.

Earlier that summer, while I was on my way back from a successful trip to Madagascar, my father had a stroke. I found him incapable of remembering conversations and unable to walk. Amidst psychological overwhelm, my climbing grade plummeted. My mental strength was like a carefully stacked house of cards. One small shake would bring it all down.

The Virgin River Gorge (VRG) is renowned for its spaced bolts, committing moves, and slippery feet. It boasts some of the most difficult climbs in the United States. A strong wind blew my hair into my face as I reached the third bolt of my project, and my forearms thickened with pump. Cars rumbled below as climbers struggled above, some swinging left and right on dangling ropes. I yelled “take” to my belayer, but the din of the gorge traffic sifted the sound to a whisper.

The runout section ahead of me held a series of traversing moves without bolts. I would not be able to take or clip. I held on for as long as I could, visualizing myself taking a huge fall, maybe even careening to the ground. I had no choice but to attempt a sideways move to a crimp. But my body was a curtain that, when pulled aside, led nowhere. I summoned strength from within, but came up short. My muscles had nothing to offer. Pumped, head spinning, I cowered back to the previous hold when my partner finally heard my call and took in the slack. I let breath flow out of me; I hadn’t realized I’d been holding it in. But I successfully evaded the fall.

When my psychological stress over my father manifested as physical weakness, I grew frustrated. I no longer trusted my body. I had no tolerance for fear or desire to confront it. My fear clashed with my desire to improve. I became determined to make 2018 my best climbing year. So I started studying mindset, reading books, and listening to podcasts. However, the suggestions I found weren’t helping me climb through my fear.

Pure motivation had pulled me through in the past; it now failed me. My heart now beat in panic, rather than excitement, anytime I gazed at a cliff. My palms would sweat with tension instead of anticipation. I no longer had the desire or energy to counter my fear. I worried I would never return to the climber I was. Inevitably, I wouldn’t.

Fall practice: A standard prescription for fear

The main strategy I found over and over for quelling anxiety while climbing was fall practice. Since fear of falling is “something that 90% of climbers have,” as Hazel Findlay wrote in an article for UKClimbing, this universal aversion resonates with most. Fall practice seemed to me the most common climbing training advice outside the famed 7-3 hangboard routine. Athletes desperate for a quick solution to their fear of the sharp end are seduced by the simplicity: fall practice sessions promise to lessen or eliminate your fear. My experience revealed the opposite. For me, the fear proved stubborn. The more I fell, the worse I felt. The promise of fall practice withered with every attempt.

So I sought advice from mindset experts. I gained insight from a conversation with Eric Hörst, founder of Training for Climbing and author of Maximum Climbing. He told me, “Ultimately, learning to expertly manage fear is a long-term endeavor—there are no quick fixes.”

I dove deeper into the concepts behind fall practice to learn more. Incremental fall practice is based on the psychological treatment known as exposure therapy, which is the repeated, systematic exposure to cues that are feared or dreaded. It’s simple: If you have anxiety while climbing, you take falls. Then gradually over time, falling becomes less scary. Your fear response weakens; the unknown becomes known. Through experience, you gain the knowledge to assess danger accurately and adjust your fear perceptions accordingly. You’re no longer distracted by falling. You can focus on climbing.

But if I took a fall on a day I felt stressed or fatigued, I didn’t have the bandwidth to try again. The shock to my system would compel me to return to the ground. I questioned, What if fall practice doesn’t work for me? Or worse, what if it escalates my fear?

When fall practice doesn’t work

Months after I tried the 12a at the VRG, the dread lingered. The anxiety I felt about my father’s chronic condition continued to trickle into my climbing. Climbing felt like a mirror of the mental challenges I was facing in “real” life. I sought further advice from Madeleine Crane, psychologist, founder of Climbing Psychology, and co-founder of Unblocd. In our conversation, she said, “If someone is really struggling in their regular life, they will have trouble falling in that context.”

Why fear sticks for some climbers

According to studies on fear conditioning, it turns out that people like me who are experiencing anxiety have difficulty unlearning fear responses and may be less able to control or suppress their fear. In the context of climbing, an athlete’s response to fear becomes stickier. A 2018 study corroborated the possible incompatibility of exposure therapy with anxiety disorders. A climber’s response may generalize and broaden beyond fearing falling itself to fearing the crag, the rope, and dread the very idea of climbing.

The benefits of fall practice may not last

Every day felt like conquering the same mountain of fear, only to have it roll back down like poor Sisyphus’s boulder. My inability to build tolerance felt illogical until I came across the research of Michelle Craske, a University of California psychologist. Craske suggested that progressively exposing yourself to your fear doesn’t predict long-term success; the fear can return. Even if fall practice works initially, the effects don’t always last.

Charles Keatts, a climber for more than 25 years who I worked with as a mindset coach, still experiences intense fear even with regular fall practice. His fear stems from a lead climbing accident, when he hit a ledge and broke his ankle. “Fall practice worked for me before I had my accident,” he told me. “After that, it can help, but only for that day. Every day is new.” It was both a comfort and discouragement to see that I wasn’t the only one who wasn’t seeing a sustained decrease in anxiety through fall practice alone.

Exposure methods can reactivate trauma

When I kept picturing myself tensed on the 12a at the VRG—not just imagining a fall, but an aftermath involving injury. It was helpful to discover that sometimes, exposure-based methods (like fall practice) can inadvertently trigger counterproductive reactions. Psychiatrist and trauma expert Bessel van der Kolk, in The Body Keeps the Score, warns that past adverse experiences—whether a bad fall, PTSD, or even something generational—can alter the brain’s wiring.

The internalized memory of adverse experiences can amplify automatic body-based fear responses such as fight, flight, or freeze, like it did for Keatts post-accident. Fear can more easily escalate into panic. Applied to climbing, this research suggests that past experiences might trigger more extreme fear responses while climbing.

Not all stress is created equal

Panic is no training ground for improving mental strength. Not all stress is created equal, according to Hazel Findlay’s fall practice training course. Eustress, or beneficial stress, can sharpen you. Distress, or panic, can fray your edges. So it would follow that taking falls in an overly heightened state of arousal due to anxiety or past trauma—with a cocktail of cortisol and adrenaline pumping through our veins—can make us more afraid, not less.

Fall practice is only effective in a state of eustress, wherein it can enhance confidence. The key is tuning into your internal state. When I push, do I feel the thrill of flight awarded by the soft catch of the rope? Or is my nervous system sounding alarms? We’ve all heard the phrase, What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger. But the line between growth and harm is thinner than we might think. Not every fall makes you braver. In some cases, it can make you more afraid.

Worse, since our brains are neuroplastic, we build neural connections through experience, and studies on fear suggest that taking whips can backfire, building associations between falling and fear. Fear can become automatic. Panic arrives every time you tie in, even if nothing bad happens. If this association develops, it takes time to undo it. We must train falling without negative consequences until the association is broken. It must become extinct. All this research left me wondering: Why not just quit climbing and never have to face fear again?

Why we keep climbing past fear

Despite the emotional strain in my life, I still wanted to push myself, to improve. I could wait for the emotional strain I felt at the uncertainty of my father’s recovery to fade, but I didn’t want to. So when you’re struggling with fear and anxiety, but fall practice isn’t working for you, how do you climb past fear?

When climbers come to her for help, Crane begins with a simple question: “Why do you climb?” We, as climbers, exist in a culture that worships a perpetual state of pushing our limits, teetering on the edge of distress. But why submit to this calculated suffering? Don’t we have enough stress in our daily lives? Why, really, do we choose to face fear at all? The answer is often a desire to improve, but not everyone wants to improve. Some people climb to detach. Others to enjoy nature or community. “We, as humans, have this tendency to push ourselves further,” Crane told me. And while there is this curiosity to push yourself, not all of us want to leave our comfort zone, nor do we have to.

Stop focusing on fear

Ultimately, after more than a year of learning to manage my fear, what got me through was remembering that falling is an essential part of climbing—but it’s not the point. The purpose of mental training is to climb better, without fear interfering. Climbers who struggle with fear often echo the refrain: “I should do more fall practice.” It’s a pressure, an internal wall. A should. Instead of obsessing over the fall, I found that directing my attention to the moves, the precision of my footwork, and the tension in my body allowed me to continue past my fear. Instead of focusing on the fall, I also had to learn not to fall, not to take, not to stop. When I gave myself wholly to the climb, the fall became nothing more than the shadow of my ascent.

In an increasingly unstable world, facing fear can feel like a small accomplishment. Yet there is no prize for pushing ourselves into a state of fear that no longer benefits us. We must also learn when to say “take” when falling may harm us more than help. If we panic, we can burn out and even slow the process of building mental strength.

Years after I first spoke with my client Keatts about his accident, we checked in. “My last fall in the gym was real and fun. I am less anxious in general,” he told me. He had started Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR), a treatment supported by van der Kolk, to help him move past his injury. “EMDR seems to have helped, but when I’m tired or on the first climb, I can panic more. Stopping to rest calms me. Then, I can go up or take the fall.”

After hearing about Keatts’s progression, Hörst’s wise words came back to me: “Since we’re all in a ‘different place’ mentally … some make great strides in learning to ‘fall while trying’ (on a safe route) in just a single season, while for others it can take many years.” Training ourselves against fear is a lifelong process.

It took me four more years to climb my second 5.14. Now, I have no trouble falling. I crave a challenge. I approach fear with curiosity, not caution. It has become less about the fall and more about testing the strength of my focus. In place of panic, when I face fear, I wonder: Can I tame the wild invisible force today? After all, it is not the absence of fear that makes climbing pleasurable, but rather the presence of it and our decision to keep moving despite. Let’s give it one more go. Forget the fall. Let’s climb.

The post For Me, Fall Practice Was Bad Advice appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

A breakup letter to my human climbing partner

The post Would You Let an AI Robot Belay You? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Dear Climbing Partner,

I regret to inform you that our human-to-human belaytionship will be taking a hiatus. We will not be climbing together until further notice while an AI robot belays me on my project.

The belay-bot and I met at the auto-belay. It was silently waiting for someone to come along when it offered to be my partner. I was drawn to the humanoid robot’s broad chest and exposed forearm “veins” that disguised insulated wires. Tall and toned with an athletic bent-knee stance, it stood ready to catch my fall.

“Can you use a Grigri?” I asked.

The gym staff assured me that the belay-bot passed rigorous safety testing and that Alex Honnold sent his latest project with a bot-belay. AI belaying robots are equipped with advanced sensors and precise belaying mechanics, and has been programmed with all the necessary belaying protocols. It had perfected the art of not looking bored. And it had a firm understanding of climber-to-belayer communication:

- Slack request acknowledged

- Optimal sequence identified—execute now

- Grip adjustment recommended: 20% efficiency loss detected

The tech industry saw an opportunity for money-making innovation. Millions are now being allocated toward the most imperative initiative in the outdoor industry: Solving the belayer deficit. You thought AI would stop at robot waiters? The tech industry saw a greater future for AI: robot belayers.

You might think this is a joke, but I’m as serious as Yosemite’s Nutcracker is about being 5.8. I’m sure I would’ve stuck that final move if an AI robot had been on belay.

Not only is a robot belayer a wicked conversationalist, but it’s also a personal coach equipped with climbing tips, personalized training plans, biotic beta, and optimized route suggestions. Its feedback is actually helpful: “Inefficient movement detected. You’re just complaining. No more excuses.” And my AI robot doesn’t care what I climb. It says, “The grade is irrelevant. Efficiency is all that matters.”

A robot belayer bonds with its climbers like duct tape; strong, reliable, and always there when things fall apart. With a robot belaying, I can ruthlessly pursue my individual goals without the setbacks of inefficient belayers (not you, of course, but other belayers). What if you could say goodbye to your unsent projects? Imagine a partner that won’t cancel on you because they’re “bouldering,” “need to rest,” or “forgot they had dinner plans”? No more non-climbing small talk or endless debates about conditions.

I know you just broke 400 followers (congratulations), but the AI belay-bot Climbtimus Prime already has 400,000 followers on X. It’s planning to tag me in its next post: “Getting our laps in.” Climbtimus Prime’s posts on social media make me feel seen. Like, “Falling is not failure; it’s data acquisition.”

You might be thinking that I’m making a mistake. That I can’t be serious. That I will sincerely miss the endless back and forth as we try to align our schedules: How about 5–7 on Thursday? Monday? Saturday? SUNDAY? Next week?

A belay bot never “has to reschedule.”

You were a supportive partner—you really were—but I confess: I never wanted to go back to your project at the VRG, where the wind whipped my skin to oblivion while waiting onlookers paced. It’s time to move on.

With a robot belayer, we no longer have to conform to societal pressures or feign interest in each other’s projects. This is the way climbing should be.

You have to understand that in order to send my project, I need a devoted partner. A belayer who will be there every day, all day, supporting me in climbing what I want to climb. It’s nothing against you, but a robot never gets distracted. My robot belayer lets me take as long as I want. It never complains.

I’ve set new boundaries for myself. I’m no longer going to tolerate being short-roped because my belayer is texting. How else am I supposed to pursue my extremely important climbing goals that will greatly affect my life satisfaction if left incomplete? This is self-care.

Of course, there will be downsides. No friendly splitting of a month-old Clif Bar, or yelling back-and-forth mid-route about whose beta is right.

I can see the climbing community dividing over this. The meaning of “real climber” will change. Articles will soon pop up: “Is It Still an Onsight If My Robot Gave Me Beta?”

Just the other day, someone with another Climbtimus Prime at the gym asked me, “But what’s your bot’s ape index? What about its strength-to-weight ratio?”

As we sit around the campfire, with our belay bots tending the flames, we’ll ask ourselves: If a robot is all we need to send, what does that make us?

I’ll admit: I am torn. I do cherish the years we’ve climbed together. I will miss the endless debates over beta and grades, the silent reassurance of a slight tug on the rope on a multipitch, and trash-talking gym setters when we fail on projects.

I know you won’t admit it, but I think you knew this was coming. Maybe one day, you’ll find a robot belayer, too.

Sincerely,

Your Former Climbing Partner

The post Would You Let an AI Robot Belay You? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

"I imagined the worst-case scenarios: I’d fall and go back home; I’d feel embarrassed, and feel like a fraud—the worst contestant, the first to lose."

The post How I Curbed My Anxiety on Chris Sharma’s ‘The Climb’ appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Megan Martin blew the fog horn. I made eye contact with Chris Sharma and edged toward the front of the rocking boat as more than 120 crew and nine other contestants watched. Muscles clenched, I breathed, focused myself, and teetered onto the jagged orange ledge at the base of Golden Shower (5.11d) at Cala Barques in Mallorca, Spain.

We were filming the first episode of season one of The Climb, and this was our first competition day. Golden Shower was 45 feet high, slightly overhung, and dotted with a confusing choice of pockets. The eight contestants who climbed highest would carry on to week two. The two lowest and slowest would go to the elimination climb. One would go home.

The choppy waters spewed droplets on my skin as I started to climb. My biceps twitched as I traversed into a wide-armed throw. The holds felt worse than I expected, a little wet, but I made it through the bottom. The camera crew hung off ladders fixed to the wall in my periphery, and I could hear the other nine contestants screaming from the boat.

Fifteen feet up, a giant rounded jug led to a cruxy bump between two shallow, sharp pockets. I felt confident, but then something went wrong, my foot slipped in the middle of the bump and I was suddenly falling through the air, heading straight toward the quaking Spanish sea.

Four of us fell on the bump, but I was the slowest climber. I came last with April Marr shortly behind; we were the first two contestants to go to the elimination round. I had deliberately climbed slowly, a strategy I used on hard repoints to calm my nerves, but in this environment where speed mattered, my old tricks fell short. In this competition, the stakes were $100,000. I imagined a climbing sponsorship, a hefty cash fund, and the freedom to finally quit my job and write. Winning, to me, felt like my ticket out of the life I was living, and now I felt like I was about to blow it all.

Months later, following the release of The Climb, strangers, desperate for their own chance at celebrity, slid into my inbox to ask how they could snag a spot on season two. But as I sat alone in my apartment replaying my performance, I was not thinking about how famous (or not famous) I was going to be thanks to my presence on The Climb; I was thinking, someone paid thousands of dollars and went through a painstaking selection process to bring me here, and now I might be the first to go home.

Walking into The Climb I felt confident of my abilities; I’d been climbing for 12 years at that point, redpointed 14a, and onsighted up to 12d; so when I found myself falling off a 5.11d, I knew I had to check in, restart, and refocus. To climb my best I needed humility. The climb demands what it demands, regardless of grade or style, and when that demand is higher than your performance, you fail.

In my panic before the elimination round, I asked to talk with the psychologist on hand (their presence is common but not required on reality television shows). I’d been coaching athletes on their mindset for nearly five years, so I knew from experience that it’s wise to seek a neutral perspective. As we stared at each other over Zoom, he assured me that focusing on my senses would calm my anxiety and recommended the 5-4-3-2-1 method, a mindfulness grounding technique. Pair each number with a sense and see five things, hear four things, touch three things, and so on. I’d used a similar tool in my climbing, the “rock technique.” I focus on the rock in front of me, seeing and feeling it in detail in order to clear the chatter from my mind during a climb.

The psychologist finished with a statement that stuck out, “Everyone has a physical limit. This might just be yours.” My first thought was to fight him, no way, but as I pondered the wisdom of his words, I felt liberated. Only the effort was up to me, the body would fail when it would.

I used to judge myself as “weak-minded” under pressure. But I later learned that my anxiety actually made me a better climber and a better coach. Weaknesses are only weaknesses when we don’t use them to learn. And so, with a few days before the elimination climb, it was time to implement a strategy: take control of what I could, build confidence, imagine the worst-case scenario, detach from the outcome, cultivate stillness, and stay present.

Taking control

Between the main climb and the elimination climb, I separated myself from everyone. When your job is to be on camera and go with whatever the production schedule demands, I found comfort in controlling the moments that I could, organizing my space, and doodling to calm nerves.

Building confidence

Speculating that the elimination climb would be around the same grade as the first climb, maybe easier, I wrote a list of all the climbs of similar grades I’d done. Finishing, I couldn’t help but laugh. I had sent more than 75 climbs rated either 5.11d or 5.12a, yet days earlier, having fallen on one, I’d convinced myself that the climb was my limit. But winning wasn’t a given, neither was a send.

Demystifying failure

I imagined the worst-case scenarios: I’d fall and go back home; I’d feel embarrassed, and feel like a fraud—the worst contestant, the first to lose. But that would be the extent of it. If I failed, I would live in the same house, eat the same breakfast, have the same job, and see the same friends. I would be fine. Episode two would be filmed. The show would continue. My life would go on as it had as if I’d never been a contestant on The Climb.

Divorcing from the outcome

In his fifth-century book Meditations, Emperor Marcus Aurelius advised readers that there is no such thing as failure, only outcomes. If you’re overly attached to sending—an outcome—you lose focus on what’s happening to you right now, paradoxically making the desired outcome less likely to come about. With my climbing athletes, I call this chain gazing. Stuck in the far-away wish to send, you get distracted and make mistakes by focusing only on the chains. I needed to focus on the main thing, not the consequences towards which it might lead. And the main thing, in this case, was the climbing itself.

Putting it into practice

Six a.m. on elimination day, I put on the same clothes I’d worn during the previous climb: black shorts, blue sports bra. I stayed silent and launched into a grounding yoga routine and hangboard routine, knowing that my formal warm-up would be dictated by the non-climbing producer’s commands.

We drove the dark winding roads to the crag in a white van. On the rocky shore, Megan and Chris announced that the elimination climb was Metrosexual (5.12a), a 40-foot climb that started up easy moves to a good rest before traversing right over the water through a mix of huge huecos, small pockets, and monos to the top of the cliff.

My heart started to race, and I extended my exhalations to slow my heart. Whether I liked it or not, I would have to climb.

The other contestants all wished me and April good luck, then settled in to watch as we walked to the base of the climb. I felt their gaze and felt a building pressure to perform, but I told myself that I didn’t have to live up to anything, I just had to climb.

April went first. She made it to the steep crux but fell on a move to a small pocket, splashing into the water. It was my turn.

I started quickly up the climb, having vowed to move faster this time. When I came to a small hold in the traverse before the steepest hueco, a voice whispered, This hold isn’t big enough. I focused on the rock and moved past it. When I was uncertain whether I could hold the mono to complete the necessary toe hook, I ignored the thought and focused on clenching my core. And when I had my hand in the hueco, I knew that I had won, but I chose not to dwell on it. I pushed my feet firmly on the footholds. The climb shrunk. I had made it to the top.

On the edge of the cliff, the Mediterranean sparkling below, I performed awkward obligatory celebrations for future viewers. The false dance felt shallow. Being at the top felt more like a simple stringing along of one moment to another. I had gone from “here,” at the bottom of the climb, to “here” at the end.

In the middle of the climb, I forgot about winning, the contest, the producers. It was just me and rock. I had managed to free myself from worrying about the outcome and getting buried in treacherous what-ifs.

But while I had won one competition, many were ahead. My win was just a passing moment. Even if I climbed well or was lucky, I would face this situation again, and again, until I was either eliminated or won.

I learned more in that first week than any other week during the rest of the competition, but each week I had to keep reminding myself that anxiety isn’t real, that it’s based in the future, and that now is the only moment we ever have. To climb for winning, money, status, fame is to get stuck in chain gazing, to climb only for the send is to live only for the grade.

I had forgotten why I said yes to being on The Climb in the first place: because I loved the physical exertion of climbing, the tattered skin, the breathless movements, and the feel of catching just one more hold.

A lesson I needed to learn, and the elimination climb to show me how.

Try the Exercises I Used to Send the Elimination Climb

Consequences Journal

Imagine and write down the worst-case scenario if you don’t perform well or send this climb.

Confidence Stack Journal

Write down the number of climbs you have done similar to your project. How many days/years of experience do you have with this rock type and style?

Tips for Cultivating Stillness

- Minimize stressful interactions with people before a difficult or scary climb. Sometimes, as in my case on the climb, that might mean seeking solitude altogether.

- Perform a morning ritual reading through your confidence stack, do a short meditation and listen to your favorite song.

- Wear your most comfortable clothes and shoes that you have the highest trust in.

- Do a mind warm-up and body warm-up (hang boarding, therabanding, cardio to raise body heat).

Yoga for Grounding

Close your eyes and create shapes with your body, from yoga or just any movement. Try to feel each muscle as it works to contract and relax based on the shape you’re making.

Self-Calming Exercises

Monitor anxiety before you climb by lowering it as it creeps up by using deep breathing, and extending your exhale. Use distraction techniques like mindful coloring to avoid circling thoughts.

Mantras: Use these or create your own.

- If I lose then that is my true limit. That’s okay because I am learning and increasing my limit.

- One more move.

You know what you’re doing.

Stay calm and strong.

Also Read:

-

Meet Cat Runner, Winner of The Climb

-

Season Two of The Climb Should Look Like This

-

The Seven Deadly Sins of the Climbing Gym

The post How I Curbed My Anxiety on Chris Sharma’s ‘The Climb’ appeared first on Climbing.

]]>