How to apply the smile beta

The post This One Simple Thing Might Change How You Climb appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Last spring, I worked the classic Moab V8 Chaos, which requires hanging from a right-hand crimp and stabbing a foot into one of three possible divots in a dihedral to the left. The lowest divot was the easiest for me to reach, but I needed to be on the highest to transition out of the crux. In a breakthrough sesh, I envisioned a foot-walk—left foot in the low divot, right foot in the middle, then left foot in the highest. The first time I tried it, my body tilting horizontal as I walked up the sidewall, I broke into a grin because it was undoubtedly the silliest move I’d ever done. Though I fell on the lunge to the lip, I knew this was the beta for me.

But on the next several attempts, I couldn’t repeat the foot-walk. I’d grit my teeth and bear down, and punt every single time. What was so different about that first attempt? I sat and listened to the birds and the babble of the Colorado River, replaying the initial try in my mind. Suddenly, I realized what made that burn so special: the smile. The next time I latched that right-hand crimp, I pasted a grin back on my face, and like magic, the foot-walk felt effortless again.

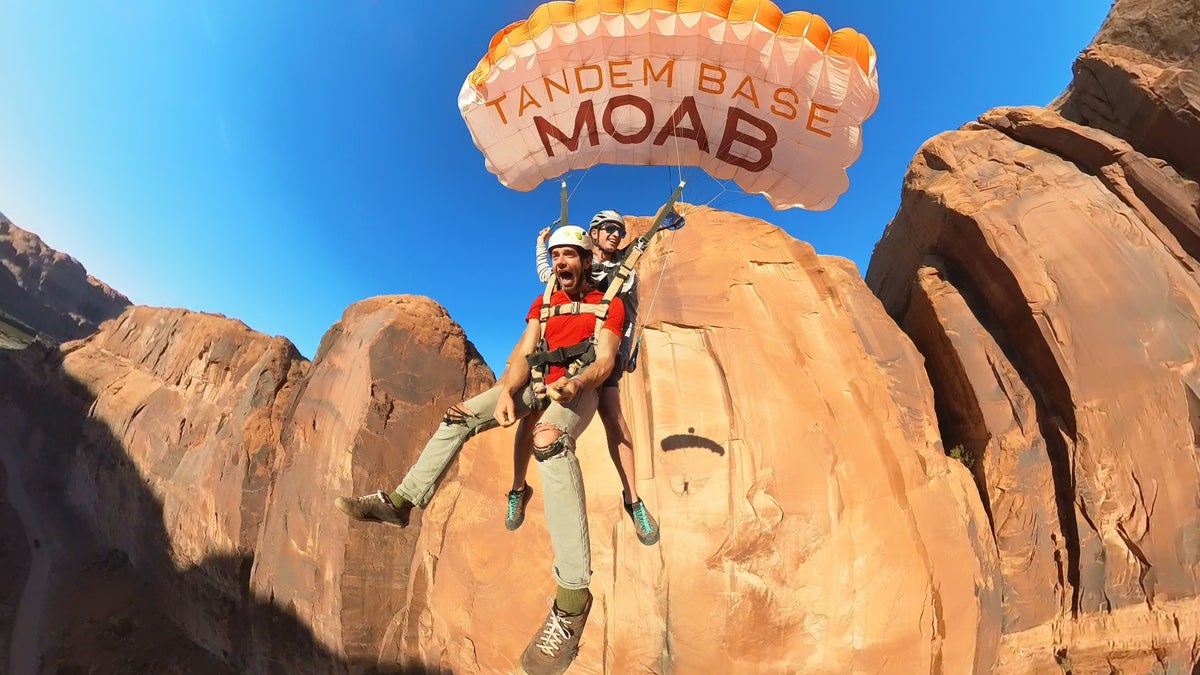

Watch the author send Chaos using the smile beta

The science behind smiling

If I’d been paying attention to the long-distance running world, I might have discovered the smile beta much sooner. Back in 2017, when marathoner Eliud Kipchoge approached the mythical sub-two-hour mark, running news outlets reported that periodic smiling had been an essential tactic. Kipchoge claimed his smile would “ease him to the finish line.”

Later that year, researchers at Ulster and Swansea Universities conducted a study that confirmed Kipchoge’s instincts: in a group study on runners, participants saw a nearly 3% increase in efficiency in their running when they smiled. In addition, the “smilers” self-reported significantly lower levels of pain and exertion than the “non-smiler” and “frowner” test groups.

We might think we smile because something makes us happy, but the causality runs the other way, too. We can feel happy because we smile. When the muscles associated with smiling contract, they trigger a release of stress-reducing serotonin and mood-enhancing dopamine throughout the body. In physiological terms, these chemicals lower blood pressure and reduce sensitivity to pain. But more broadly, a smile activates a lifetime’s worth of embodied associations: memories of prior positive outcomes and moments we’ve experienced with a smile on our face.

Does smiling = sending for climbers?

Though it hasn’t yet been empirically tested, anecdotal evidence suggests that smiling improves performance and mindset for climbers as well as for runners. A good case in point: the 2023 documentary Smile and Fight about Natalia Grossman’s dominant 2022 bouldering season. When she underperforms at a World Cup event in Salt Lake City, commentator Meagan Martin observes that Grossman is “clearly not having any fun” in the semifinals. She was climbing timidly, afraid to lose. But when she chalks up for the finals, the beaming grin has returned to her face, and she climbs like a beast—a happy, smiling beast—winning gold in front of her hometown crowd.

It turns out that the key to her strong performance had been reconnecting with her mantra “smile and fight,” which she had devised with USA Climbing National Team Head Coach Josh Larson. As Larson explains, “I don’t talk about winning World Cups. I just remind the athletes, you have to have fun, and if you start with that, everything else will fall into place a lot easier … That is success: enjoying what you’re doing.”

This attitude is widespread, not just on the US National Team but throughout the competitive climbing sphere. Because comp sets—especially for bouldering—are meant to be slightly sub-limit, every competitor is theoretically capable of doing every problem. It’s often just a question of whether the competitor believes they can. As a result, mindset work is a central pillar of comp preparation.

On an episode of The Nugget about training the mental game, climbing coach Justen Sjong says of watching the World Cups: “I look for that smirk [that means] ‘I don’t know what the outcome is, but I’m psyched.’ It’s the walk to the base that names it for me … You can see when an athlete’s going to send, when you see that moment of confidence.”

Ever since hearing that interview, I’ve tried to walk to the base of every climb—the warmup, the proj, even the Kilter Board—with that same optimistic energy. The boost to my own performance has been astonishing.

Tips for applying the smile beta

- Identify the points on your project (either by recording yourself and watching afterward, by having a friend watch and report, or simply by attending to your own body) when you’re scowling, and see what happens when you smile at those points instead.

- Train your body to associate a smile with difficult moves or sequences, both during visualizations and actual attempts. Picture the feeling of doing each move perfectly, and the grin that perfect execution will put on your face.

- On onsight and flash attempts, take note of your facial expressions while reading the route; it’s common to furrow your brow when eyeing a gnarly crux, but try to coax a smile, cultivating positive anticipation of what’s to come.

- Ask your belayer or spotter to cue you with the word “smile,” or something similar, where necessary. (A phrase I heard and liked recently was “eyes bright.”) Or just have them remind you, when you hit the crux, that Chris Sharma’s favorite car is the Volkswagen Passat.

Reminder: Climbing is fun

Beyond the measurable physical effects of smiling, a smile also has the subtler power to change the vibe of a session. From elite athletes competing on the global stage, to mere mortals logging hours on the proj, I’ve observed this phenomenon over and over. If you’re scowling on a climb and fall mid-crux, the scowl is likely to turn into a scream of frustration. But if you’re grinning when you fall? You might just erupt into laughter.

I’ve written in the past about the power of screams (they have a time and a place!), but I know that at least for me personally, it’s a lot more pleasant to be laughing than screaming. I also suspect it’s a lot more pleasant for everyone else at the crag, too.

After all, we climb for fun. Our sport is a haven for grownups who never outgrew the joys of the jungle gym. Sometimes climbers (myself included) forget this, and get wrapped up instead in a results-oriented mindset that owes to our sport’s longstanding focus on conquest—conquering literal mountains, battling figurative demons, and sending hard.

Now, on every new project, I identify the most important moment to smile, and I drill it into my muscle memory along with every drop-knee and gaston. The pain recedes and the dopamine flows. The smile beta is a deliberate step away from that outdated tone of aggression, toward an experience that rightly centers joy. Goodness knows, with our beloved public lands and National Parks under attack and our friends in federal agencies in constant upheaval, we hardly need more reasons to scream. But I, for one, am glad to be learning to smile in the middle of Chaos.

The post This One Simple Thing Might Change How You Climb appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

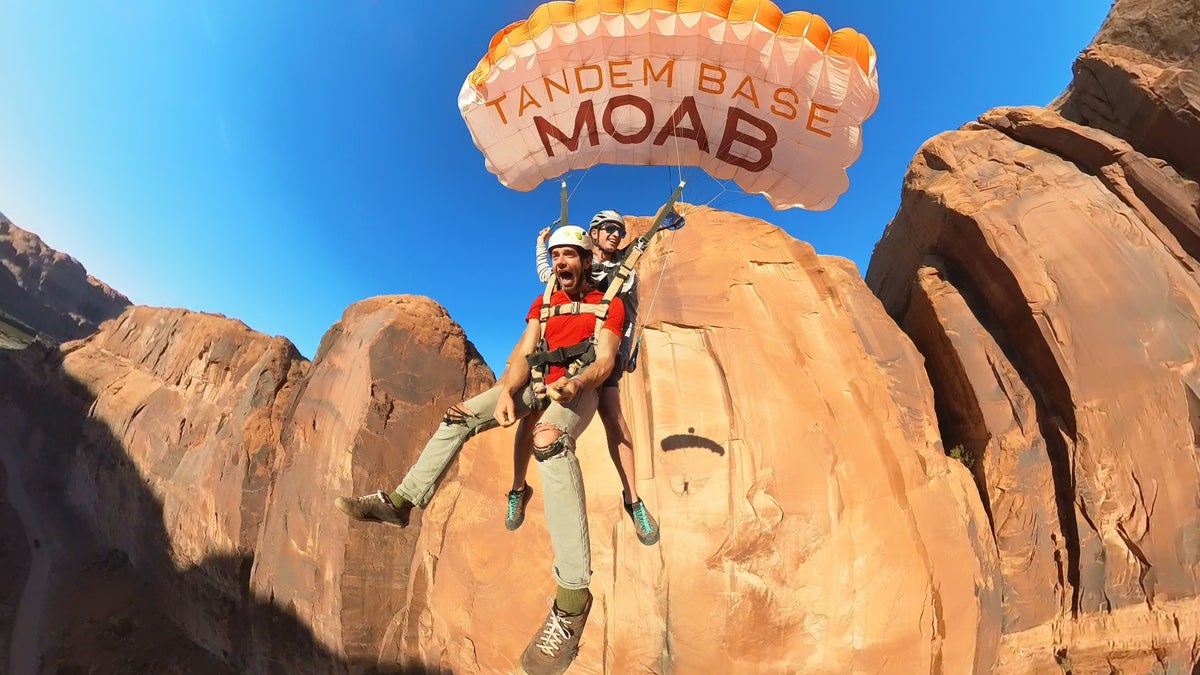

Could one tandem BASE jump change a climber’s POV on the high-risk sport?

The post This Climber Tried Tandem BASE Jumping for the First Time. It Wasn’t What He Expected. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Long ago, as young kooks, my best friend and I fumbled our way up Ancient Art, the iconic corkscrew in Utah’s Fisher Towers. Gripped the whole time, I finally tiptoed across its infamous walkway—a footwide sidewalk with several hundred feet of exposure on either side—and executed the critical beached-whale beta to approach the top of the spire. I crouched, gathered my courage, then levered upright so my partner could snap a pic.

By the time we’d started our descent, another party cruised up behind us. Half-watching, while rigging our next rappel, I saw someone standing on the apex out of the corner of my eye. And then, like a nightmare coming true, they tumbled off the summit cap. For a second, I envisioned the pendulum fall he was about to take. The rope would surely slam him into the tower. But then I realized he wasn’t even tied in.

Before I could decide whether to watch the carnage or avert my eyes, a parachute deployed. The whoosh vibrated the desert air around us, and then in surreal silence the figure drifted down to the parking lot. The jumper’s joyful flight was, paradoxically, our grimmest fear: coming unmoored from the rock, seeing the cliff rip past as the ground approached at lethal speed.

I’m cautious by nature, but I calculate my climbing risks with care, and keep things buttoned up on the wall. While we all know that climbing is inherently dangerous, it’s also a sport that prioritizes teaching safety practices—more so, I would argue, than teaching technique—from day one. Non-climbers may perceive what we do as thrill-junkie madness, but in general, it’s really, really safe.

According to the annual Accidents in North American Climbing from the American Alpine Club, the U.S. and Canada see around 30 climbing deaths per year, out of an estimated 5,000,000 active climbers. For perspective, the fatality rate for dance parties is higher than that. Meanwhile, with an average of 1 death for every 2,500 jumps, BASE jumping—jumping off buildings, antennas (i.e. radio towers), spans (i.e. bridges) and earth (i.e. cliffs)—is a statistically dangerous sport. In fact, it’s arguably the riskiest form of outdoor recreation, alongside other contenders like big wave surfing and backcountry skiing. Considering how many climbing legends have lost their lives strapped to a BASE rig, I never even considered trying it myself.

But then this fall, Ryan Katchmar (known to all as “Gravy”) of Tandem Base Moab saw an article I wrote for Outside about highlining, and offered to take me tandem BASE jumping. We live in a BASE paradise, and he tells me that the go-to jump for beginners is the Tombstone: a 400-foot face with a rounded summit. It looks like something you’d see in a graveyard for giants. There’s a hiking approach up the backside, but the Tombstone also hosts a classic trad line, “The Corner Route,” that climbs to a shoulder below its summit.

I spend the next week doing research that sometimes makes me feel better and often makes me feel worse. There has never been a guided tandem BASE death, I discover. Then I come across the BASE Fatality List, an online database of accident reports within the community. It takes a long time to scroll from top to bottom. I’m briefly reassured when I look into the certifications required through the American Mountain Guides Association, including fundamentals, first aid, and rescue skills. Then I’m appalled when it dawns on me that tandem BASE instructors don’t have to be AMGA certified. In fact, they have no accreditation at all—no official body to judge their aptitude.

Instead, the entire sport of BASE jumping is self-regulated. Most gear manufacturers won’t sell a BASE rig to a customer unless they can provide a skydiving license, which requires a minimum of 200 jumps from an airplane. But once someone has BASE gear, they’re free to do as they please. Prudent newbies find a mentor or enroll in a first-jump course, but there’s nothing (other than common sense) to prevent folks from diving unsupervised into the deep end, often with disastrous results.

When I learn all this, it seems outrageous. But then I think of how, outside of the gym, climbing is just as unregulated: a beginner can buy a rope and a set of cams, walk into the desert, and start cranking up choss with no instruction whatsoever.

Just 10 minutes from my house, the Tombstone perches above a curve of the Kane Creek drainage—where a BASE jumping accident made the news not long ago. On the way, I pick up my friends Mark and Maggie, who have offered to take photos and climb with me. We drive past wetlands with leaves brushed with the first yellows of autumn. My friends are cheerful and chatty as always, but I woke up nervous, looking for fateful omens in the patterns of my coffee grounds, wondering who will finish the revisions on my book if I crater today.

I’m not worried about the climb. It’s a five-pitch, 5.12-/7a+ trad route, but the rock quality is excellent, and the crux, I’ve heard, takes gear wherever you want it. It’s the descent, via BASE, that has me pondering posthumous publication.

As we turn downriver, cliffs thrust up on either side of us—angled benches collared in talus, rising to sheer sandstone walls. We park in a pullout, undertake one of Moab’s shortest approaches, and run up the first couple pitches. Midway up the wall, while I’m chicken-winging in an offwidth, I hear the whistle of rockfall. Instinctively, I duck my head and hunch my shoulders. A second later, I hear what sounds like a bomb going off, a shockwave through the cirque. I look to my right and see a parachute cutting a peaceful arc down toward the road. The sound wasn’t rockfall at all, just a jumper leaving the exit.

The last pitch is a thin-hand crack that tapers down to fingers, with a crux navigated first by jamming, then by stemming the route’s eponymous corner. On my first attempt, my forearms start burning in the ringlocks, and instead of gunning it to the stem-box as I clearly should have, I place another piece. As soon as I clip it, I melt out of the crack. I lower back to the belay and rest for a few minutes.

During the break, I remind myself that if I’m willing to take a 400-foot dive off a cliff today, I should also be willing to take a 20-foot whipper on this pitch. I don’t know how to assess risk in a BASE context; it’s like when I first started trad climbing, and couldn’t tell the difference between bomber rock and deadly choss. That’s part of what makes it scary. The air seems more agitated as the day warms up . Are these big gusts of wind going to be a problem? Will they make the chute collapse? I do know that a whipper on the crux of this pitch would be completely safe. On the next attempt I skip the extra cam, push through the crux and take it to the chains.

The top of the route provides a vantage of the wonderland behind the Tombstone: the winding wash through Pritchett Canyon, thin fins in the foreground, and the La Sal Mountains beyond. I also see that I have a new text message from Gravy, sent sometime that morning: The wind is an issue. We have to reschedule.

A series of storms pass through the desert and the delay gives me time to watch a new BASE documentary called Fly, which, like my previous research, sometimes makes me feel better and mostly makes me feel worse. It’s a National Geographic film full of love and community and vertigo-inducing cinematography and a host of larger-than-life characters, one of whom memorably quips, “Name of the game, bro: don’t touch your shadow.” But a lot of them end up touching their shadows. It feels like how Free Solo would have felt if Honnold had botched the boulder problem.

When the weather clears a week later, Gravy and I meet in the parking lot at the base of the Tombstone, and this time we take the hiking approach. I didn’t really know Gravy before this mission took shape, and I expected him to resemble certain camp counselors from my youth—rad and energetic, but also batshit crazy in a way that made me, as a cautious kid, uneasy.

I soon determine that Gravy is indeed rad and energetic. He also seems at least slightly batshit crazy, especially when describing his affinity for “low pulls,” which are jumps so short the canopy barely has time to open before you hit the ground. (Apparently it takes about 70 feet for a parachute to deploy, and Gravy’s lowest jump was from 78 feet.) But his confidence is undeniable, and it puts me at ease. He’s a double-black-diamond skier escorting me down the bunny slope.

The trail passes petroglyph panels with sheep and alien-like humanoids, geometric patterns, and perfect circles. I learn from Gravy that BASE jumping, like climbing, is seeing a huge explosion in numbers. He attributes this to viral clips of impressive stunts and hilarious pre-jump meltdowns, racking up millions of views. “The drama is right there,” he says, “People freaking out, saying funny shit, facing their fear. And it only takes a few seconds, so it’s perfect for social media.”

The trail skirts around the cryptobiotic soil and runs into a sloping sandstone fin, the backside of the Tombstone, which we ascend toward the summit. I finally ask about the accidents I keep hearing about. “What happens?” I say. “Does the chute get tangled, and it doesn’t open right? Or is it user error?”

“The gear itself doesn’t fail. If operated correctly.”

“So it doesn’t just … not come out?”

“It always comes out.”

We come to the top of the Tombstone, and the slabby fin we’re walking on abruptly terminates at a vertical drop. I’m overcome by the sensation I used to have while cliff jumping into rivers and lakes as a teenager—a sense of the void reaching upward to swallow me. “Where’s the exit?” I say.

Gravy points to a flat segment of capstone jutting over the headwall. I walk as close to the edge as I dare, then lie on my stomach and shimmy forward until my face peeks past the lip. Just as I take in the arc of the road, treetops, and meadow far below, I hear voices rise from the wall. A team of climbers are reaching the top of a seldom-done aid line.

“Who’s up there?” one shouts to the other. “It’s a couple of BASE jumpers,” his partner replies.

It’s the scene atop Ancient Art, but in reverse: they’re the cautious practitioners of stonecraft, and I’m the idiot jumping off a cliff.

We stall to let the climbers summit, and Gravy takes the interlude to introduce me to the tandem BASE jumping setup. I step into a harness clipped to the front of his rig, he tightens the straps and buckles, and then—still on flat ground—we test the timing of our leap. Gravy starts counting down from five, and after he says “four,” I’m supposed to join him. Then we’ll say, three, two, one, and hop forward. It doesn’t have to be a world-record long jump, he explains, just enough to take us a few feet past the edge. We try a few times, and it feels intuitive, easy enough.

Even now, right on the verge of the jump, I can’t identify how I feel. I’m calm. I love this. I’m confident, and I’m kinda rad, even? Then I look at the edge and it gets rounded with a white halo and there’s that sensation again of the abyss.

Once the aid team clears out, Gravy walks to the lip and spits to test the wind. “Primo,” he says. He’s right. All is still. The temperature is perfect, the low sun hits the fins and cranks the saturation of their highlights and shadows. The river glistens with broken light, and the La Sals do, too, with the season’s first snow.

Gravy walks back to me and we strap ourselves together. Safety-check: the chute, the pull-cord, the straps. With my back pressed up against Gravy’s chest, we take a choreographed series of steps up to the edge, our legs swinging in unison. We stand at the lip and I swivel my approach shoes into the sandstone, making sure I’m firmly planted.

“Are you ready to go BASE jumping?” Gravy asks.

“Yes,” I say. I mean it.

“Five, four, three,” Gravy begins.

“Two, one,” I say, and we’re airborne.

The freefall is brief and strangely peaceful, touching nothing but sensing one’s centrality to everything. The red walls sweep up to cradle us, and the chute’s opening must be loud, but I don’t hear it. Then we’re drifting through the canyon, the talus below us and the Cirque of the Climbables above. I can’t believe this life. My feet skate across the sand as we land. I don’t remember whether I give Gravy a high five or a hug—but I do recall talking a mile a minute. I know instantly that I’ve had way, way too much fun. This is a disaster. I step out of the harness and Gravy scoops the chute into his arms. I’m babbling and swearing quite a lot and telling him that was SO SICK.

It’s only a couple hundred feet from the landing zone to the parking lot. On this brief stroll, I ask, “How much does a parachute cost?”

“The tandem ones are expensive,” he says.

“No, I mean just a one-person setup.”

“Around forty-five hundred,” he replies. “Expensive, but not crazy. Why do you ask?”

“Just curious.”

I look up at the Tombstone. It looked different after I climbed it, and it looks differently different tonight, having jumped off the top. Its dimensions have now been expressed in the unit of my ascending and falling body.

Standing now next to our vehicles, about to drive off into the evening, I ask if Gravy has a philosophy about the sport, or a vision for where he wants to take it. He’s accomplished most of what he set out to accomplish, he says. He’s hit over 450 exits in the Moab area alone, many of which he established himself.

“I’m sure people find deep meaning in it, but for me I just love jumping off stuff for fun.” It doesn’t have to be more than that. “And it’s so different from climbing,” he goes on. “Climbing is hard and scary while you’re in it. But with this,” he gestures toward the cliff, “all the fear is in the anticipation. Once you step off the edge, you’re not scared anymore. You’re just doing your thing.”

The post This Climber Tried Tandem BASE Jumping for the First Time. It Wasn’t What He Expected. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Shout, shout, let it all out. Harness your bestial power scream for ultimate sending

The post How to Climb Harder by Utilizing Power Screams appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Recently, at Dude’s Throne in Golden Gate Canyon State Park, Colorado, I was gunning for my first 5.13, a power-endurance route called Buster Brown (5.13a). At the crux bulge, I grabbed a weird pocket-undercling and set up for a lunge. As sunset lit the orange-patinaed granite, I moved into the dyno, giving off a robust scream. Its echo skittered around the valley, still Dopplering long after I’d blown the move. From the alpine lake below—out of sight in the pines—some fishermen laughed. Then one of them yelled up, “What’s your safe word?”

Benefits of Screaming

I’m no pro climber, but I’ve been told I scream at an elite level. This probably has to do with my early training in martial arts, in which I learned to harness the explosive power of the kiai (more later). In my 20 years of climbing, I’ve learned that my screaming—in addition to being fortissimo—actually has helped me send. Screaming works in three overlapping ways.

1. Psychological

The benefits of screaming in sports have been well documented. In an often-cited 2014 study, “Effect of Vocalization on Static Handgrip Force Output,” researchers at Drexel University had test subjects squeeze a “handgrip dynamometer,” and observed that grip strength increased by 25 percent when accompanied by a scream. The researchers then extrapolated other potential athletic benefits—increased output in other muscle groups, heightened focus, psychological intimidation of opponents—which is why a variety of grunts and squeals has begun to echo around tennis courts, basketball arenas, and boxing rings worldwide. But even though the study wasn’t designed to assess climbing, the grip-strength bump these researchers identified is reason enough to get vocal.

2. Mechanical

A good belly-scream—originating deep in the diaphragm, where opera singers and yogis breathe from—engages the lower abdominals and the muscles around the rib cage, which helps keep your core tight. On cruxes, a tightened core keeps us closer to the wall, enables more-precise movement, and maintains body tension for optimal use of marginal holds. Conversely, a tight-throated squeak, in which just the upper part of the chest constricts, will not make the core-magic happen.

3. Neurological

The Drexel study also suggests that screaming may increase physical output by engaging the sympathetic nervous system: Screaming subconsciously triggers the fight-or-flight response, the adrenaline from which not only ramps up our grip strength but also heightens our focus. As the famed vocalist Chris Sharma once said, “You have to get totally animalistic .… When you’re doing a hard move, there is this excess energy you have to let out. Air explodes out of you”—tapping into our well of wildness.

Screaming and the Martial Arts

Many climbers scream only as an unconscious by-product of trying hard, but a premeditated scream, deliberately deployed at just the right moment, is a far more powerful tool. As a teenager, I worked my way up to a second-degree black belt in Shotokan-style karate. Particularly useful when I transitioned to climbing was the kiai,

the exclamation that a martial artist makes while executing a strike—it’s a way to gather energy at a crucial moment in a sequence of moves, a sonic punctuation mark to express the totality of your focus.

The kiai also translates perfectly into a climbing context: The crux of a route isn’t just the move that requires the most raw power; it’s also the moment that demands the highest degree of precision, body-awareness, and focus. A scream here, imbued with kiai-like intention, can propel you toward a fleeting instant of perfection. The yell can even become choreographed; hence we see Adam Ondra, in his visualization routines for his 5.15d Silence, practicing the accompanying sounds with the sequences. “It is very important to yell in the right places,” Ondra was quoted as saying in Outside. “When I yell, I am giving it everything I have. In the easier sections, I must give only the minimum necessary.” (See sidebar on aiki for more.)

Skills and Drills

These drills will help you develop the three key elements of a successful power scream: the inhalation of breath, the exhalation of sound, and the direction of focus.

Drill No. 1: Inhalation

Step one is to get a feel for diaphragmatic breathing, aka “belly breathing.” To practice:

- Lie on your back, either in bed or on a flat surface, resting one hand on your sternum and the other hand on your lower belly.

- Breathe in slowly through your nose, such that your stomach pushes out against your belly hand but your sternum hand doesn’t rise.

- Engage your stomach muscles, feeling your belly hand drop as the diaphragm expels air through your mouth. (Again, your sternum hand shouldn’t move.)

- Set a timer for 5–10 minutes, and practice daily until this mode of breathing feels natural.

Drill No. 2: Exhalation

Once you’ve mastered belly breathing, you’ll make sure your vocal sound originates from your belly—not your throat.

- To get the feel for exhaling from the diaphragm, place a hand on your belly (as in the previous exercise) and pretend to cough; that kick down low in your stomach is where your power scream should originate.

- Let a breath drop into your belly and make a loud fake-laugh with the sound Ha-Ha-Ha, once again using your belly hand to feel the diaphragm contracting. The throat should remain relaxed, almost entirely uninvolved in creating the sound.

- Repeat with the sounds He-He-He, Ho-Ho-Ho, and then Hi- Hi-Hi for a minimum of 30 seconds each. (If this gets as tiring as sit-ups, you’re doing it right.) Repeat the cycle 2–3 times daily, as a stand-alone exercise or warm-up before climbing.

Drill No. 3: Direction

The last, and most important, step is to learn to direct your scream’s energy—you’ll visualize where you’re sending that air, and the intention behind it.

- Find a difficult move on a route or boulder problem—ideally a full-extension deadpoint. Ultimately, you’ll want to try this exercise on three or four different problems.

- Attempt the move several times, each time mentally directing your exhalation (or even a light vocalization) toward a different limb.

- Pay attention to the results: What happens when you focus on the hand that’s deadpointing? How about the hand that’s remaining in place? A foot that remains on a foothold, a foot that’s flagging? What happens when you scream into your hips, your shoulders? What happens when you focus/exhale/vocalize toward the holds themselves?

Once you’ve gotten a feel for screaming on isolated moves, you can apply it to your project: Figure out which of your limbs/holds is the best mental target for your power scream, and remember to include the vocalization any time you’re visualizing beta.

The complementary energy of Aiki

Kiai has an equally important twin-concept, aiki. If the kiai is a manifestation of your outward-focused energy, then the aiki is its inverse: an expression of harmony with your opponent’s energy that will help dissipate your own muscular tension. There’s value in recognizing that the power-scream is only half the equation—if you can’t also manifest aiki, with your power scream leaving you unable to relax back into the flow, you may in fact be better off climbing in silence. As Dave MacLeod puts it in “The Sharma Scream” entry in his Online Climbing Coach series, “The great skill of climbing is to be able to switch from moment to moment between screaming to get maximum power on a very powerful but technically basic move, and calm focus the next instant to perfectly aim for a tiny foot- or handhold.” I’d suggest that the key to these transitions, whether powering up or powering down, is the breath: Pausing for a single, deliberate inhalation and exhalation after a crux helps dissipate the tension, and prepares you for calmer, aiki-informed climbing ahead.

Pro Climber Mix-n-Match

Match the climber to their power scream:

| Climber | Scream |

| A. Adam Ondra | 1. Nnnrrraaaaaugh |

| B. Margo Hayes | 2. Psaaaaaat |

| C. Kevin Jorgeson | 3. Urrrrrghghghghnnnnn |

| D. Chris Sharma | 4. Mmmnnnhfff |

| E. Alex Puccio | 5. Dyaaaaaaah |

| F. Pamela Shanti-Pack | 6. Yoooohuh |

| G. Daniel Woods | 7. Hhhneeeeeep |

Answers: A=5, B=6, C=1, D=2, E=3, F=4, G=7

Brian Laidlaw is an author-songwriter, PhD candidate in creative writing at the University of Denver, and lives part-time in Boulder.

The post How to Climb Harder by Utilizing Power Screams appeared first on Climbing.

]]>