A pillar's verticality leads to strenuous climbing, and the skinniest of them are prone to collapse if conditions aren’t just right. We asked three expert ice climbers for their advice.

The post How to Know If an Ice Pillar is Stable appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Though beautiful and inviting, pillars are also intimidating. Their verticality leads to strenuous climbing, and the skinniest pillars are prone to collapse if conditions aren’t just right. We asked three expert ice climbers for their advice on pillar climbing: Roger Strong, a prolific first ascensionist from Seattle, Washington; Dawn Glanc, a climbing guide from Ouray, Colorado; and Raphael Slawinski from Calgary, one of Canada’s foremost ice climbers. Above all, they agreed, super-skinny pillars must be approached very cautiously.

Safety and stability

Before you attempt an ice pillar, you need to judge whether it’s solid enough to bear your weight and repeated strikes from your tools and crampons. In the 2010s, the 120-foot Fang pillar in Vail, Colorado, collapsed in early season when it wasn’t formed sufficiently—the climber on board barely survived the crash. And, of course, there’s this horrifying video from Canada. The pillar’s size and attachment, the condition of the ice, and the temperature before and during a climb all affect stability.

“Something I read a long time ago has stayed with me: Never climb a feature you’re afraid to stand under,” says Raphael Slawinski. “It seems like this would be clear, but we don’t always follow this obvious bit of advice.”

Assuming a pillar passes the stand-under-it test, consider recent weather and ice conditions. Bitter cold can make ice brittle and more likely to break— especially if there was a sharp drop in temperature in the day or two before your attempt. Although there are many variables, the ideal temperature range for well-frozen but non-brittle ice is around 25 to 30 degrees Fahrenheit.

Also, look out for horizontal fractures splitting the pillar—these often form just below the point where a free-standing pillar attaches to the wall above, as the pillar shifts and settles. Try to assess whether such a break passes completely through the ice, making the pillar unstable, or has partly filled in and refrozen, restoring the pillar’s strength.

“If I’m inspired to hop on a really thin pillar, I try to research the significant weather patterns leading up to it, such as how many melt/freeze cycles it has gone through,” says Roger Strong. More melting and refreezing generally makes a pillar stronger. “I also look at what’s above it, and the consequences below if it rips while I’m on it. I push and lightly tap all around the base to get a feel for the integrity. Then I’ll spend time doing just a few moves to get a feel for if it should be climbed or not, going one or two moves higher each time and then downclimbing. If all the senses are giving me the green light, I’ll commit to the radness. If not, I bail.”

When in doubt, toprope. Whether the climber is leading or toproping, the belayer should be positioned to one side or well sheltered from falling ice.

Protection

If a pillar is as wide as a car and mostly attached to the rock behind it, you can protect it with ice screws just as you would any other climb. But when a pillar spans the mouth of a cave from top to bottom like a snake’s fang, you’ll need extra precaution, especially when the spindle narrows to body width.

“My guideline for actually placing a screw in a pillar is it has to be around six to eight feet in diameter at the base,” Strong says. “This typically means this climb has taken a while to form and has survived a few melt/freeze cycles, contracted and expanded, and had the chance to settle.”

Sometimes you may be able to place bomber protection in the rock behind or beside a thin pillar. But if that’s not an option, the safest way to climb skinnier pillars may be to run it out. Place a solid screw or two below the foot of the pillar (often there’s a pedestal of solid ice below the spindle itself), and then don’t place another screw until you’re above the attachment point to the wall behind. This obviously requires careful judgment of the risk of a long fall versus the risk of pulling down the pillar, but since placing pro is strenuous on steep ice, you will be conserving strength as you conserve the integrity of the pillar.

Whether you run it out or place screws for protection, the old saying “the leader must not fall” is never more appropriate than on a skinny pillar. Climb slowly and well within your limits.

Movement

A skinny pillar narrows your options for tool and foot placements, and likely will force you out of the stable triangle position typically used on broad ice flows. You may find yourself pigeon-toed on a skinny pillar, and you’ll draw on rock climbing techniques to stay in balance.

“The main thing is good footwork—maintaining a balanced position,” says Dawn Glanc. “You may be doing that by standing on one foot and flagging the other foot to one side for balance. When you get ready to swing, suck your hips into the ice, with a nice arched back, to keep your weight over your feet.” On very narrow pillars, you may be able to wrap one leg around and behind the ice and squeeze it for better balance and purchase.

On brittle or fragile ice, especially at the foot of a skinny pillar, move very gently: Think tapping, pecking, and then hooking with your tools rather than swinging. Use those same divots for your crampon points (monopoint crampons help here). Step up as if you were moving up a face climb on rock, letting your body weight drive the crampon points into the ice. Make sure your picks and crampon points are razor sharp.

Never place your tools side by side horizontally on a thin or fragile pillar, or you risk creating a fracture. Instead, reach high to place the next tool at least six to eight inches above the other.

With aggressive curved tools, you can bump your hands up to the higher grips on the shaft for longer reaches. If you have one arm with more lock-off strength, like your right arm, you may choose to make more long reaches with that arm, Strong says. Get a high placement with your left tool, then match hands on the shaft of this higher tool. Now remove the lower tool with your left hand, lock off with the right again, and place high with the left.

Keep an eye out for knobs, holes, or ridges of ice where you can flat-foot a crampon or back-step for a more restful stance. If you find a stem rest, milk it.

You’ll likely be pumped at the top of a pillar and tempted to punch it to the belay. But the abrupt transition to lower-angled ice may be the crux of a steep pitch. Even if you’re pumped, stop and place a good screw before topping out.

Keeping it together

Pillars are pumpy, and the intensity of the climbing tends to make them feel even pumpier. To keep his forearms fresh, Strong says, “I like to move slowly and take the mental attitude that it’s like a 5.10 jug haul at the gym. After every three to four steep tool placements, I stop and relax into the curve of the pommel (the big grip at the base of the shaft) as if I’m resting on a jug.”

Fear contributes to the pumpiness of pillars. Your heart rate goes up, and you begin to clutch the tools with a death grip. As on a hard rock climb, remind yourself to breathe steadily. “You have to accept that you’re putting it out there and may not get gear for a while,” Glanc says. “Focus on the process and technique, and you’ll soon be up the pitch.”

The post How to Know If an Ice Pillar is Stable appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

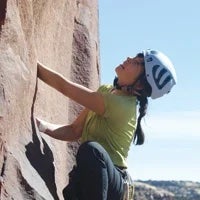

Head trauma is among the most feared and catastrophic injuries in climbing. So why aren't more rock climbers wearing helmets?

The post Why Do So Many Climbers Not Wear Helmets? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

This article was originally published in 2013 and has been updated where relevant—Ed.

Beth Rodden didn’t expect trouble on the Central Pillar of Frenzy on Yosemite’s Middle Cathedral Rock. After all, the 33-year-old superstar had free climbed the Nose of El Cap and put up the Valley’s hardest crack climb, the then-unrepeated 5.14c Meltdown. One of the best female rock climbers on the planet, she had never been injured in a climbing fall. Rodden devoured routes like the Central Pillar without breaking a sweat.

But this mega-popular 5.9 would serve as a reminder of one of climbing’s greatest risks—and also a leading appeal of the sport: that anything can happen, anywhere, anytime, without warning, even on the most familiar terrain. Partway through the first pitch on the Central Pillar, Rodden’s foot slipped on polished granite, flipping her upside-down and into a freefall. Twenty feet down, going approximately 23 mph, the back of her head slammed into rock.

At first, Rodden says, “I didn’t think I was hurt. We actually climbed the rest of the day. But the next night at dinner, I was having a really hard time concentrating. I could see [people talking], but I couldn’t process what they were saying.” Another red flag: Rodden’s forehead was sore, even though she’d hit the opposite side of her head. The next day she went to her doctor, who explained that her brain had slammed forward against her skull upon impact with the rock face. Diagnosis: concussion.

Concussion is only one of many serious head injuries a climber might suffer—others include skull fractures and severe lacerations—but new awareness of concussions’ frequency and their potential long-term effects has caused consumers, manufacturers, and regulators to re-examine many sports and their protective equipment. High-tech anti-concussion helmets are making their way into the cycling and skiing markets, and President Obama declared that if he’d had a son, he might not allow him to play football because of the latest research on traumatic brain injuries. One study, from the Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology journal, found that an estimated 5,067 patients suffered head and neck injuries from rock climbing nationally from 2009 to 2018. Concussion and closed-head injury was the most common injury at 44 percent. Indeed, there is little doubt that Rodden’s experience could happen to anyone.

Rodden says her recovery was slow, and she wonders if the concussion is to blame when she has trouble concentrating even today. The symptoms of traumatic brain injury can last for weeks or months—and multiple concussions can cause years of problems. The accident caused Rodden to rethink her stance on climbing helmets. “I hardly ever wore a helmet while climbing in Yosemite, but now I always try to wear one, even if the route is easy,” she says.

Climbing Magazine is now 50% off for a limited time. Just $24 a year gets you five print issues (four Climbing, one Ascent) delivered to your door. Subscribers also receive unlimited access to over 5,000 articles on climbing.com.

But sometimes, especially when the climbing is hard, Rodden chooses to leave her helmet behind. When we spoke, she was in Spain for sport climbing on overhanging limestone, and she hadn’t even packed a helmet for the trip.

When it comes to helmets and climbers, inconsistency is everywhere. Most ice climbers and mountaineers wear helmets, as do many traditional rock climbers. But far fewer rock climbers don lids for short climbs, especially sport routes. (Though you can’t rule it out, you’re much less likely to smack your head or suffer rockfall on an overhanging 5.12 sport climb, at the Red River Gorge, Kentucky, for example, than you are on a ledge-filled 5.8 in Eldorado Canyon, Colorado.) Many ice climbers forego their helmets while rock climbing. Some climbers wear a helmet to one crag but not to another. Or they’ll wear it while leading but not while belaying. And given the track record in cycling—around half of all cyclists still don’t always wear helmets, despite a great toll of head injuries—this is not likely to change. Most climbers will continue to make day-by-day decisions about their helmets.

On the surface, this seems nuts. If helmets prevent or mitigate head injuries, shouldn’t a climber always wear one, from the second she arrives at the crag to the moment she starts hiking back to the car? Or is helmet use, like so many aspects of our sport, an issue that resists pat answers?

Head injuries, though rare in climbing, are potentially catastrophic.

On a spring day in 2008, Evie Barnes, a 21-year-old boulderer, started up her first trad route, the long, easy east face of the Second Flatiron in Boulder, Colorado. Near the top, her partner asked if she’d like to lead a short step. Barnes fell partway up the pitch, popping out her naively placed pro, and tumbled down the slab. She sprained both ankles, strained a knee and thumb, and chomped a big chunk out of her tongue. Before she came to a stop, she smacked the side of her head just above her left ear against a big flake of conglomerate sandstone.

Barnes was in shock, but other climbers helped her get to the trail and walk down the mountain to her car. She didn’t go to the doctor right away, but then, a couple of days after the fall, a friend told her she was acting “weird.” Barnes says, “I’ve never been much of a crier, but I started randomly crying on my way to work.” A round of visits to neurologists and other specialists soon began. Though no evidence of injury showed up on MRI or CT scans, Barnes began suffering migraines. Her speech slowed, and her motor skills deteriorated. “If I was eating, my fork would just sit there; I couldn’t bring it to my mouth,” she says. “And my legs would crumple beneath me while I was walking.”

Barnes was diagnosed with post-concussive syndrome, a series of symptoms associated with brain injuries, and five years later she’s still trying to find her way back to a full recovery. “My neurologist put me on a seizure medication that helped my migraines but made me act like I was drunk. It was embarrassing,” Barnes says. She tried craniosacral therapy and massage. “Life was doable, and I could work a part-time job, but I never got the energy back that I used to have.”

Last fall, she banged her head against a low ceiling, and some symptoms returned. (Victims of repeated concussions are particularly vulnerable to long-term problems.) Now she’s undergoing hyperbaric treatments, breathing 100 percent oxygen in a chamber for 70 minutes a day. Unable to work full-time, she helps clean the hyperbaric business to pay for treatments she can’t afford. But she’s begun climbing again. “It took a lot of adjustment, because just like with the fork not being able to get to my mouth, my hands didn’t want to move to the next hold,” she says. “I’m definitely not as strong as I was before, and I’m way more cautious. But I’m starting to feel like I can actually train again.”

Luckily for climbers, injuries like Barnes’ are unusual. High-altitude mountaineering is more dangerous: If you venture above base camp on Annapurna, you’ve got about a 1 in 25 chance of dying. By contrast, fatalities in rock climbing and bouldering are very uncommon. Statistically, rock climbing is nowhere near as dangerous as the mainstream media (or your mom) would believe.

[Read: Is Trad Climbing More Dangerous Than Sport Climbing? What 30 Years of Accident Data Tells Us.]

An average of about 30 climbers of all disciplines die each year in the United States, from falling, rockfall, or any other cause—about the same number of skiers and snowmobilers, combined, killed by avalanches annually in the U.S. Compare this with cycling, which kills 600 to 800 riders a year and injures more than 40,000 in the United States—a greater rate of deaths per participant than in climbing. A parent or nurse might argue that 30 deaths is still an unacceptably large number, but compared to other sports perceived as less dangerous, rock climbing is statistically quite safe.

In fact, the huge majority of climbing injuries are non-traumatic—finger and elbow tendonitis, shoulder pain, and similar overuse injuries—or cuts, sprains, broken bones, and other non-life-threatening injuries, mostly in the lower extremities. In 2009, the American Journal of Preventive Medicine published a study by Nicolas Nelson and Lara McKenzie of U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission data on climbers admitted to emergency rooms. Injuries to the lower extremities accounted for nearly half of the climber ER visits between 1990 and 2007, with ankles bearing the brunt of the damage. In the same study, head injuries (including neck, face, eyes, ears, and mouth) accounted for 12 percent of the total—an average of about 275 a year. (There was no data on who wore a helmet.) Other studies and surveys have shown a 4 to 8 percent rate of head trauma among all climber injuries.

The actual total of head injuries is likely considerably higher than these studies suggest. Some surveys included tendonitis and other non-emergency injuries, and the Nelson-McKenzie study did not account for injured climbers who saw a non-emergency physician (as Rodden and Barnes did), nor did it track fatalities. We also do not know the numbers of unreported head injuries—climbers who took a blow to the head but never saw a doctor.

An average of about 30 climbers of all disciplines die each year in the United States, from falling, rockfall, or any other cause—about the same number of skiers and snowmobilers, combined, killed by avalanches annually in the U.S.

Meanwhile, there’s no doubt that head injuries, though relatively uncommon, often are radically different from other climbing maladies. Inflamed tendons are frustrating and painful, but they rarely require significant medical intervention; broken bones seldom demand hospital stays. By contrast, a quarter of the head injuries in the 2009 survey—more than twice the rate for all climber ER visits—resulted in hospitalization. And as Evie Barnes’ experience shows, the consequences of head impacts can stretch over years.

“Every single doctor said, ‘You should have worn a helmet,'” Barnes says now. “They said I probably still would have gotten a light concussion because I hit so hard, but they had no doubt that if I had a helmet, I would have been way better off.”

Rock climbers wear helmets in some settings but not others.

Not long ago, very few climbers wore helmets, even in the most dangerous situations. Pioneering alpinist and gear maker Yvon Chouinard climbed perilous ice and alpine routes with his head clad only in a yellow-and-purple knit hat. “When I started climbing 25 years ago, it wasn’t cool to wear a helmet,” says Dan Middleton, chief technical officer at the 65,000-member British Mountaineering Council (BMC), which has done extensive helmet research and education. “You’d very rarely see people [using them while] crag climbing. Now that’s changed.”

The vast majority of ice climbers and alpinists wear helmets. But among rock climbers, helmet use varies widely depending on where and how you climb. In a survey of 1,887 rock climbers published in Journal of Trauma in 2006, 36 percent reported wearing helmets most or all of the time, while 19 percent never wore helmets; the rest sometimes or seldom wore them. Another survey of 1,400 rock climbers, completed in 2012 by Kevin Soleil, then a master’s student at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, found similar patterns. The percentage of respondents who said they usually or always wore a helmet was 49 percent among sport leaders, 53 percent for topropers, and 86 percent for leaders on traditional climbs.

Look around a typical American crag, and Soleil’s numbers will likely seem high. (He cautions his results may be skewed because he did not survey climbers under 18—the mean age in his survey was 36, and younger climbers tend to wear helmets less often than older ones.) Based on multiple observations of sport and traditional crags in Colorado, helmet usage was lower across the board. In Boulder and Clear Creek canyons, at five mid-difficulty sport climbing crags, about 35 percent of leaders were wearing helmets. Less than 20 percent of belayers wore helmets, and only 10 percent of people standing or sitting under climbs wore them. Down the road in Eldorado Canyon, a traditional area known for loose rock and tricky protection, 66 percent of leaders wore helmets, and 45 percent of belayers were helmeted.

Unsurprisingly, Soleil’s survey suggests that as climbs get steeper and the difficulty higher, especially on sport routes, fewer people wear helmets. Generally, overhanging climbs are less vulnerable to rockfall and impacts with the rock. Chris Weidner, who says a helmet saved his life after a 30-foot fall on El Capitan a decade ago, usually doesn’t wear one anymore for sport climbing. “I can’t think of anybody that sport climbs hard and wears a helmet,” he says. Rodden said during her trip to Spain, “I haven’t seen a single person here wearing a helmet.”

Virtually no one boulders with a helmet, despite the frequent bruising falls many boulderers take. One who does is the father of the bouldering V-grade and author of the Hueco Tanks guidebook, John “Verm” Sherman, who has had multiple concussions and now sports a helmet on highballs and even some butt-draggers. In a column at dpmclimbing.com, Sherman wrote, “These days, if I can’t find a legitimate reason not to wear a helmet, I wear one. Which is 98 percent of the time.”

You can also find rare instances of people climbing indoors with a helmet. Mark Dixon, 55, is an emergency room doctor in Loveland, Colorado, and a 5.12 leader, and every time he ties in to lead a route at the Boulder Rock Club, he also straps on his helmet. “I started wearing a helmet in the gym about a year ago,” he says. “I was taking a lot of falls, and twice in a week flipped upside down and whacked my head. It was nothing serious, but I thought, ‘This is stupid—I wear a helmet biking, climbing outdoors, and caving; why not wear one here, too?'”

For many climbers, the decision whether to wear helmets is not based on safety at all, but more around comfort and fashion. Soleil’s survey found that trad climbers were much more likely to say helmets were comfortable and “acceptable fashion.” Sport climbers were more likely to say a helmet was “unaesthetic” or uncool. (Typical negative comment: “I feel like I stand out at the crag.”) Soleil also found a significant correlation between climbers who don’t wear helmets and those who believe brain buckets “take away from the aesthetic look and feel of a climbing scene,” or that they “reduce performance.”

Though it’s rare, there are cases where a helmet negatively affects climbing performance. Most trad climbers can recount stories of removing a helmet to squeeze through a tight chimney. Helmets also can push your face away from the wall if you’re pulling in close for a delicate move. And for climbers who count the ounces of their quickdraws and choose sub-9mm ropes for redpoints, even a half-pound helmet may be too much to bear.

“A risk-based approach to helmets is what we’re pushing,” says Dan Middleton of the BMC. “We don’t want to just say, ‘Oh, you must wear a helmet.’ Climbing isn’t about rules. We want people to think about the risks and make their own decisions.”

Soleil’s study concluded that rock climbers make some logical risk-based decisions: They tend to wear helmets more often when they perceive greater threat from rockfall or climbs are less steep (thus a climber is more likely to impact something if he falls), and where routes are longer, poorly protected, or farther from medical care. However, the survey also reveals that some climbers make poorly reasoned decisions, including basing their choice on what’s “cool.” And across all types of rock climbing, fewer survey respondents wore helmets while belaying than while leading or following—despite the fact that falling rocks and dropped gear are at least as likely to hit you below a pitch as when you’re actually climbing it.

If you count ice climbers and mountaineers, climbers as a group still don’t wear helmets as often as participants in other head injury–prone sports. After rapid growth in the 1980s, the number of cyclists wearing helmets leveled out at around 50 percent, with the percentage rising as cyclists get older. The National Ski Areas Association reported that 61 percent of skiers and boarders wore a helmet in the 2010/2011 season, up from 25 percent in 2002/03. But among rock climbers, especially if you count belayers, boulderers, and people hanging out at the base of a cliff, fewer than half at any given crag are likely to be wearing helmets.

Climbing helmets are good at protecting against some types of impacts, but not others.

If every climber wore a helmet all the time, some would avoid life-altering brain injuries. But others would still be killed or disabled by head trauma. In early 2002, Rod Willard, an accomplished ice climber, was belaying behind the Fang in Vail, Colorado, when a block of ice estimated at 400 pounds broke off and hit him in the head. He was wearing a helmet, but he died instantly.

Rick Vance, technical information manager at Petzl America, explains that climbing helmets are considered Category 2 personal protective equipment, because they can’t guarantee protection against all risks they’re designed for. “A helmet can protect you against a golf ball–sized falling rock easily, but it cannot protect you from a microwave-sized block traveling at terminal velocity,” Vance says. “They’re called death blocks for a reason.”

Smart climbers are aware of helmets’ limits, and they focus more on avoiding blows to the head than fending them off with a thin skin of plastic and foam. Simple steps like avoiding climbing under other parties and placing protection frequently to avoid long falls will do much more to prevent head injuries than any helmet can.

There are even a few rare instances where helmets will increase your chance of injury: For example, it’s possible you could choke on the chinstrap if wedged into a chimney or crevasse after a fall. Straps on construction hard hats are designed to break for this reason, but climbing helmets are different—they have to stay on during a tumbling fall, and the straps are tested under load not to slip or break.

A less obvious hazard is what’s called risk homeostasis, the theory that says humans take more chances when they feel more protected. If donning a helmet entices you to attempt a 5.11 X face climb, are you really any safer?

In fact, it’s very difficult to prove that climbing helmets save lives at all, despite many anecdotes suggesting they do. On its website, Petzl has collected stories from climbers who swear helmets saved their lives. Reading these accounts, and looking at the photos of the busted helmets, you could easily conclude these climbers would be “dead for sure” if it weren’t for that trusty lid. But would they? Would a helmet have prevented Rodden or Barnes’ concussions?

“The answer is nobody knows,” says Christopher Van Tilburg, a mountain rescue and wilderness medicine expert who has worked for 14 years as a doctor at an emergency clinic on Mt. Hood in Oregon. “And the reason nobody knows is we can’t do a randomized, double-blind study on people wearing helmets.”

Numerous studies have shown that ski and bike helmets reduce the severity of injury in certain types of crashes. And though the data cannot prove that helmets save cyclists’ lives—because it’s impossible to say with certainty that a person would not have lived if he didn’t have a helmet—the fact that a very high percentage of fatal cycling accidents involve head injuries, and that most of the cyclists killed are not wearing a helmet—well, that’s a compelling set of statistics.

In 2007, the British Mountaineering Council surveyed nearly 500 climbers who had suffered head injuries, from minimal to severe. It concluded, “Wearing a helmet significantly reduces the chances of suffering a severe or major head injury: Non-helmet-wearers [were] more than twice as likely to suffer a severe head injury than helmet wearers.”

“Helmets probably don’t prevent death [among climbers],” says Dr. Van Tilburg. “Rock climbers die when they take huge falls and they have massive trauma. So the question is, are helmets useful for preventing head injuries? I would say absolutely yes, they are. The bigger the fall, the less the helmet is probably effective at preventing a concussion, and it doesn’t prevent what we call contrecoup injuries, where your brain moves inside your skull and bounces against the opposite side. But certainly, for a non-fatal fall, with a medium degree of impact, the helmet absorbs some impact.”

The influence of media and peer groups.

Magazines and other media also have a huge influence. Climbing occasionally gets letters from readers, like this one from New Jersey: “I like your magazine, but it is very troubling that so many of the photos depict climbers without helmets on. Does your organization recommend climbing without proper head gear?” The easy and obvious answer is that, no, Climbing doesn’t promote helmet-free climbing. Instead, the magazine’s photos reflect the current state of helmet use by climbers—Climbing shows the sport as it’s practiced today. In advertisements and videos, the vast majority of sponsored sport climbers and boulderers rarely wear a helmet. But imagine if Chris Sharma showed up in the next Reel Rock film slaying 5.15 routes in Catalunya with dirty-blond locks poking out from under the plastic brim of his helmet. Helmet use among sport climbers would skyrocket. No one says badass freestyle skier Kaya Turski isn’t cool because she wears a helmet. No one calls downhill mountain biking champ Aaron Gwin dorky because he protects his head. Why should climbing be different?

Every time we tie in, we make dozens of choices that could have serious consequences: Should I try this route? Do I trust this belayer or spotter? Can we finish the climb before it rains? Decision-making is integral to climbing’s appeal, and helmet-wearing is just one fraught choice in a long chain.

I believe if they thought seriously about the risks and benefits, more climbers would wear helmets. Someday, I believe, helmets will be a lot more effective than they are today. Meanwhile, like so many choices in climbing, helmet use comes down to very personal calculations. Here’s how I’ve made mine.

In more than 30 years of climbing, I’ve been hit in the head multiple times, usually while belaying ice climbs. Once I was dropped from the ceiling of my local gym, falling about 30 feet to the mat, where I rolled backward and smashed my head into a milk crate full of holds. I ended up with nine stitches in my scalp. If I’d hit the rigid corner of the crate, I might be dead. I can still feel the scar in the back of my head eight years later.

After that accident, I didn’t go full Mark Dixon and start sporting a helmet in the gym. But today, even though I know that helmets could be made stronger and safer, and although I understand it might not save my life, I always wear a helmet while leading, whether sport or trad. I am certain that I climb better with a helmet, with more confidence. And though I frequently don’t wear one for toproping or belaying, that’s changing, too. Some accidents in climbing are completely out of our control, but wearing a helmet is one easy thing I can do to gain a little power over my fate, without any special skills or effort. And I couldn’t face my wife if I chose to climb without a helmet, and then a falling rock or a tumble made me unable to earn a living, or talk to her, or feed myself.

Ultimately, it comes down to this: There are many climbs for which it’s perfectly reasonable to argue a helmet is not really necessary, but there are rarely good enough arguments for not wearing one. And so, more and more, I do.

Heads Up! How to Handle a Head Injury

Laceration

- Signs and Symptoms (S/Sx): Cuts to the scalp are the most common head injury. Bleeding can be profuse.

- Treatment (Tx): Check for more serious injury (like fracture). Firmly apply a bulky dressing. Consider tying the hair across the wound to act as a makeshift stitch. Apply ice to control swelling, if possible.

- Evac? No

Skull Fracture

- S/Sx: You find a depression or obvious crack, discharge from the ears or nose, or black and blue around eyes or ears.

- Tx: Apply diffuse rather than direct pressure to stop bleeding (flow can relieve build-up and pressure in the skull). Stabilize spine and monitor airway, breathing, and circulation.

- Evac? Yes

Closed Head Injury

- S/Sx: If trauma causes brain swelling inside the skull, the brain becomes compressed. Did your partner lose consciousness? Watch for headaches, personality changes, altered vision, and dizziness.

- Tx: Manage airway, breathing, and circulation. Wake up every few hours to assess level of consciousness.

- Evac? Yes

In the days and weeks following head trauma, watch for symptoms indicating concussion: concentration and memory trouble, irritability, personality changes, light or noise sensitivity, problems sleeping, and depression.

Who Wears Helmets? Estimated Use by Climbing Discipline

- Bouldering: <1%

- Indoors: <1%

- Sport: 35-50%

- Outdoor toprope: 45-55%

- Trad/multi-pitch/big wall: 65-85%

- Alpine/mountaineering: 90%

- Ice:>95%

Sources: “Helmet Use Among Outdoor Recreational Rock Climbers Across Disciplines: Factors of Use and Non-Use,” By Kevin Henri Soleil, 202; author field observation.

The post Why Do So Many Climbers Not Wear Helmets? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Climbing in the Laramie Mountains? It's not for the faint of heart.

The post Dirty Dingus McGee and the Reese Mountain Gang appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

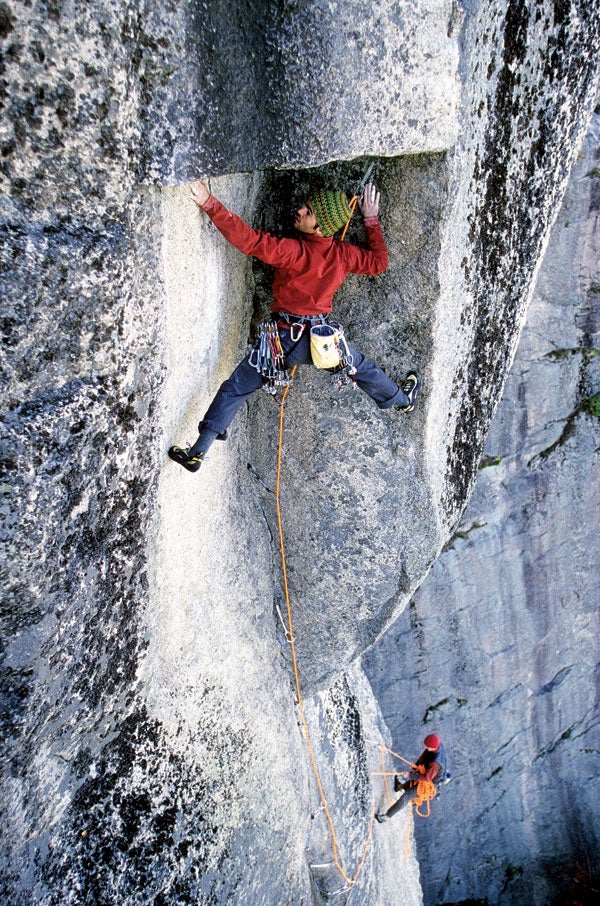

Dingus McGee had sent me written directions and three separate maps to Reese Mountain, but when we drove onto the Vale Ranch in Wyoming’s Laramie Mountains last September, already layered in dust from 15 miles of dirt roads, we quickly lost our way. A maze of ranch roads twisted through the grass like Land Rover tracks across the African veldt. In the distance, studying Dingus’ photos, we recognized the long ridge of Reese Mountain, where he and his posse have put up about 200 routes during the past two decades. But how were we supposed to get there?

Dingus had said Reese held the best sport climbing he’d ever done—and he’s put up more new routes in eastern Wyoming and South Dakota than any man alive. His photos revealed a striking fin of gray, green, and red rock, like a granite version of Eldorado Canyon in Colorado, but with better holds and plenty of bolts. Most of the routes are in the sweet spot for sport climbing popularity: 5.9 to mid-5.12. But Reese, we’d soon learn, presents many challenges unrelated to actual rock climbing. It took us an hour just to find the trailhead.

A faint trail plunged down a slippery wet draw through aspen and scrubby oaks. In the creekbed we pushed through thickets of poison ivy with glossy, scarlet leaves. (Reese climbers, we learned later, always hike to the crag in gaiters or rain pants, and then scrub their exposed skin with soap and water before climbing.) Bear shit lay in prodigious, berry-filled piles in the path. After more than an hour of walking, we climbed over a small ridge to a view of the crags, still 500 feet up a hillside. Suddenly the wind blew so hard that we staggered under our packs, loaded with food and gear for three days.

Within five minutes of reaching the lowest cliff, looking up and wondering which line of mystery bolts would make a good warm-up, I cartwheeled into the talus as a boulder rolled under my feet. As I gingerly checked for injuries, I was approached by a wiry, slightly stooped man. He had a silver beard and tangled hair poking out from under a ball cap and wore wire-rimmed glasses and a threadbare sweater. He looked us over. “You made it!” said Dingus McGee. He sounded surprised to see us.

I was beginning to sense why Dingus and his gang had decided to spill the beans on their long-secret enclave. Given what we’d experienced before even roping up, it seemed unlikely that Reese would soon be overrun with gym climbers.

Dingus McGee, née Dennis Horning, is one of America’s most prolific and enduring route developers. (Horning adopted the nickname from a 1970 film, “Dirty Dingus Magee,” starring Frank Sinatra. It’s a long story, and Dingus is more than happy to tell it, but it’d require a thousand-word detour.) Over more than 40 years, Horning has established or freed hundreds of routes at Devils Tower, the Black Hills of South Dakota, throughout southern Wyoming, and in other states. In the early 1980s, he was a pioneer of what eventually would be called sport climbing. And he’s still at it: Last winter, at age 65, he redpointed the first ascent of a 5.12 route at Guernsey State Park, a recently developed sport area in Wyoming.

Dingus is a born raconteur, telling stories in a high-pitched, singsong drawl, and his life has given him plenty of material. Growing up in Edgemont, South Dakota, (pop. 774) just south of the Black Hills, he was a bright, smart-ass kid who got in a lot of trouble without doing much real damage. When he was 17, Horning and some friends were jailed briefly for lobbing eggs at someone they thought had just egged them. “Well, that person was the new young police officer walking to work just after dusk,” he said. “Just after the jailing, a girl that had a crush on me showed up and offered to sneak some hamburgers through the small window. I asked for a hacksaw blade instead. They let everyone out when the 10 o’clock curfew whistle blew, and we never told anyone about the bar I’d sawn through in that cell.”

Horning discovered climbing in 1971 during a joy ride to Devils Tower on a new motorcycle. Ignoring the “Hiking Above Talus Requires a Permit” sign, he scrambled to the base of Hollywood and Vine(5.10c). It was obvious he couldn’t go farther without gear and knowledge, so he bought a how-to book at the visitor center. Back at the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology, where he was studying engineering, he asked local cavers where they bought their carabiners, and then sent an entire paycheck to Boulder Mountaineer (a gear shop in Boulder, Colorado, now closed) to order gear.

The Black Hills held the closest rock to campus, and Horning dragged friends out to the Needles, Mt. Rushmore, and Elkhorn Mountain, climbing whatever looked good. There was no real guidebook and precious few climbers in the area. Most of the routes he did were probably new.

Horning was a good athlete—he later competed in Nordic skiing and wrote mountain biking guidebooks—but it wasn’t just the physical side of climbing that appealed to him. He was an engineer and liked to make stuff. (He learned to make homebrew when he was just 14—with his parents’ permission—and at the tipi camp outside Devils Tower National Monument, where climbers used to crash in the ’80s, he constructed a bicycle-powered device to grind wheat for pancakes.) Making new routes naturally followed. “He might be the most prolific first ascensionist ever in the Black Hills, probably even more than Herb and Jan Conn [the original pioneers of Black Hills climbing],” said Brent Kertzman, a longtime climber from Rapid City, South Dakota.

During his first year of climbing, Horning spotted a group of climbers on a pinnacle in the Black Hills. It turned out to be Tom Higgins, Bob Kamps, Mark Powell, and Dave Rearick, four of the strongest free climbers of the day. “They befriended me immediately, and the next few days I climbed with them and learned a lot, including their ideas of what would later be called climbing ethics,” Horning said. “So I learned from the traddest of the trad,” Horning said. He paused for a beat: “I guess it didn’t catch.” He also later met bouldering legend John Gill in the Needles.

Without much concern for what other climbers thought—at a time when most new routes were still established ground-up—Horning began experimenting with rappelling to place bolts. “Doing new routes for me is a creative undertaking that makes use of several of my skill sets,” Horning explained. “But by the time I met Kamps and that group at the Needles, I had my own ideas as to what constitutes safety and fun. When you climb a new line, you are in control of the outcome, and I had several convictions of what I wanted out of a climb. Boldness and runouts never had much merit for me. If I did a climb, I wanted some 99.9 percent likelihood I would be around for another.”

Horning said he “came out of the closet” about his top-down tactics in 1981, and in 1983 he rap-bolted the second pitch of Everlasting (5.10c) at Devils Tower, while doing the first ascent. “Locals were furious,” he said. “But I put up a third of the routes at the Tower. I was more local than anyone!” (In fact, Horning put up or freed about a quarter of the routes in the Devils Tower guidebook, including many favorites: Assembly Line (5.9), Burning Daylight (5.10b), One-Way Sunset (5.10c), Mr. Clean (5.11a), the first free ascent of McCarthy North Face (5.11a), and, of course, Everlasting.)

“Back in the ’70s, I was a ranger at the Tower, and Dennis was on the South Dakota Climbing Team, which means he was on unemployment for the summer,” said longtime partner and friend Frank Sanders (see Under the Devil’s Spell). “Dennis definitely raised free climbing standards on the Tower.” Horning and his ex-wife, Hollis Marriott, popularized climbing at Devils Tower and the Black Hills through a long-running series of guidebooks, published under the pen names Dingus McGee and the Last Pioneer Woman. The Tower guide went through at least 14 editions.

Kertzman climbed many new routes with Dingus in the Black Hills, including some controversial rappel-bolted climbs in the early 1990s. Later, Kertzman said, “I decided there were better places to play that game, but Dennis would say, ‘Let’s stir up the hornet’s nest. Let’s see how long these routes will stand before they get chopped.’

“I call him the Howard Stern of southeastern Wyoming climbing,” Kertzman added. “He’s not worried about what other people think. And he was a harbinger of sorts—he understood climbing’s evolution.”

Dingus had enrolled in college to escape the draft and Vietnam, and he eventually chose mechanical engineering for a degree. However, he said, “Before I had finished three semesters working on my master’s, I discovered climbing. My foggy career goals soon became definite: I would rather be climbing than working at an engineer’s desk.” (He eventually did get a master’s and worked on a Ph.D., with the thesis topic “Using Lagrangian Coordinates to Model Shock Wave Propagation in Snow.”) Now he works just enough to get by, doing home remodeling and other building projects. Mostly he climbs.

In recent years, Horning and partners have developed dozens of routes in Harts Draw, a side canyon of Indian Creek, Utah; more than 100 routes at Guernsey, the lowest elevation and warmest winter climbing area in Wyoming; and about 60 routes on the limestone of 4 Stories, a summertime crag in the Snowy Range west of Laramie. Horning found Reese in the 1980s while perusing maps of the Laramie Mountains for mountain biking routes. He saw a cluster of contour lines and thought, I gotta check that out!

The southwest ridge of Reese Mountain is a granite fin that rises about 1,400 feet above winding Ashley Creek. Both sides of the ridge and its tip are laced with climbs. Because of the different sun and wind aspects, and who-knows-what geological influences, the rock and the climbing vary from crag to crag along the ridge.

The Hightower, at the low end of the ridge, has tricky sidepulls and edges, with a second tier of routes up an overhanging headwall. The Curl, around the right side, has chickenheads and incut edges. On the opposite side is the Amphitheater, a flat plane of gray overhanging rock. Higher up the ridge, Douglas Park, usually accessed by rappel from the ridge top, has overhanging slopers. Sherard Tower, near the top of the fin, has longer routes with slabs and roofs. Bolts are plentiful, and Horning and other climbers are rebolting their old routes to turn them into pure sport climbs or to reduce the possibility of ledge falls and other hazards. “We’ve crossed the River Styx between trad and sport,” Horning laughed. “I don’t want this to be a stick-clip area.”

“I’ve climbed at a lot of places, and steep, featured granite is pretty hard to find,” says Mike Friedrichs, a Salt Lake City climber who has been coming to Reese and developing new routes since about 1993. “City of Rocks comes the closest to what Reese is like. But it is coarse at times and doesn’t have the small-grain compactness of Reese granite.”

Like Friedrichs, many Reese climbers are part of a Wyoming diaspora—climbers who once lived or studied in the university town of Laramie but migrated elsewhere for work, or just to escape the wind, and now come back for homecomings at Reese and other favored crags. Ryan Laird, who now lives in Fort Collins, Colorado, says, “The remoteness and ruggedness of Reese provide a sense of solitude. The different sections of the ridge offer a huge variety of rock shapes and climbing styles: featured technical faces, four-pitch slabs, steep roofs, and even a few splitter cracks. It’s a special place.”

On our second day at Reese, we headed for The Curl with Friedrichs, Laird, and Anne Yeagle, another Reese climber now living in Utah, seeking the morning sun and some shelter from the sharp knife thrusts of Wyoming wind. We sampled a new route that Laird had just completed, brushing drill dust off the holds. Yeagle and Friedrichs led two 5.12a pitches, cranking positive edges over bulges. I climbed several 5.10 pitches that would be three stars anywhere in Colorado. Horning showed little inclination to shoe up. “That one’s beyond my hanging-on ability,” he said at one point. Instead, he directed traffic, telling the crew which routes they ought to climb for photographer Andrew Burr.

After lunch, I tried and failed to find the right sequence for the hand-jam and iron-cross crux of a wild 5.11 called Sex at Noon Taxes. Dingus, a fan of puns and palindromes, had coined that name. He is also prone to practical jokes and pranks. Once, when he felt a partner was lingering and chatting with other climbers for too long near the top of Devils Tower, Dingus rappelled off without him. Kertzman said every climbing trip he did with Dingus had a theme, usually involving flatulence or sex or human activities too perverse to describe in this magazine, upon which Horning would riff for days, sometimes in nasty ways, like a kid who doesn’t know when to stop teasing.

“I learned a lot from the guy, and he’s been inspirational, but in a kind of tormenting way,” said Kertzman. “He’s more of a tormentor than a mentor.”

Zach Orenczak, who has been climbing at Reese since 1998 and is about to publish a guidebook to the Laramie Mountains (see Beta section), said of Horning, “The steep routes of Reese were built by the blood, sweat, and tears of his many younger partners. Reese is Dennis’ Shangri-La, and when he’s out there, he’s the king. He rules with an iron fist and incredible punctuality. If you are not ready to hop in his van the moment he’s ready to roll, he’ll steal your route and name it Zachoff [Rendezvous Buttress, 5.11a]. At least he gives credit where credit is due.”

“Dennis can be irascible, petulant, and loves to argue,” Friedrichs said. “Some people just don’t want to be around him anymore. But Dennis also has a really caring side to him. One time a woman in Laramie was in an auto accident and was hurt pretty badly. Dennis showed up at her house and did chores for a couple of months until she was back on her feet. He’s given away more first ascents than most people ever have. I hadn’t known Dennis very long when he asked me if I wanted to do a first ascent at Devils Tower. He had cleaned the crack of poison ivy and placed a bolt, and he gave me the lead. I’ve seen him do that for a lot of people.

“Dennis is also interesting,” Friedrichs added. “He calls me at least a couple times a month to talk about string theory or nutrition—once, a long discourse on welding. It made me realize that you don’t have to stop learning when you get older.”

One veteran Wyoming climber calls Horning a cantankerous know-it-all. Another calls him a cherished friend. To many, it seems, he is both.

“One of my favorite stories is actually recounted by Dennis himself,” Laird said. “The family that lives next to Dennis once told their 6-year-old that he needed adult supervision to play outside. The kid thought about it for a minute and then asked, ‘Is Dennis an adult?’”

Late in the day, we hiked to the top of the southwest ridge, and Friedrichs, Yeagle, and I rappelled off the far side into Douglas Park. I climbed back out via Hanging of Yellowstone Kelly, a superb 5.11b with sequential cruxes between good rests. Friedrichs led the appropriately named Aeolus (5.12b), and then belayed on top with his coat snapping in the wind. “One time I couldn’t even throw the rope down to rappel to Douglas Park, the wind was so bad,” he said later. “I had to tie a pack to the rope to get it to go down.” The night before we arrived at Reese, the wind destroyed a brand-new tent.

“Is it always like this?” I asked Horning, hunched in the lee of a boulder.

“May and September are windy,” he said. “July is too hot. June and August are good.”

Reese is a bastion of Type 2 fun—activities that seem fun only after they’re over and you’re telling stories about them in the bar—which is undoubtedly part of the appeal for certain climbers. “I have had too many Reese experiences to count,” Laird said. “I have been baked, frozen, wind-whipped, and mosquito-bitten. I have experienced rain that soaked through my rain gear to my underwear, and forded flooded streams. I have seen deer, elk, bighorn sheep, rattlesnakes, and lynx. I’ve skinny-dipped and stomped out a brush fire, but not at the same time.”

In July 2002, Friedrichs and Yeagle hiked into Reese late at night during a fearsome lightning storm. “We sat on the rocks and watched an amazing show,” Friedrichs recalled. “The next morning there was a faint smell of smoke. Anne and I hiked around and climbed two pitches on Hightower. On top of the second pitch we saw smoke to the northwest. We headed back to camp and watched for about 15 minutes until flames came over the ridge two or three miles away. The flames were leaping from tree to tree. We packed up and left as fast as we could, and the fire eventually burned almost all the way around Reese. We were lucky the wind didn’t pick up.”

Rattlesnakes have been discovered at least twice at Camp Dingus, Horning’s favorite campsite atop the ridge. “We really like rattlesnakes, but not at camp,” Friedrichs said. “Dennis made a snare from a stick and a piece of twine, caught the snake, and put it in a five-gallon bucket. We put a lid on it, and Anne rappelled off the west side with the bucket clipped to her harness so she could let the snake go.”

In such an environment, it’s not surprising the Reese regulars do their best to ease the burden. When climbers are occupying Camp Dingus, hidden in a sandy patch amid the convoluted rocks on top of the ridge, a camouflage tarp keeps off the rain and sun, and a filter system provides drinking water from potholes filled by storms. The Reese crew stashes ropes and gear in strategic locations around the crags, and they stock mouse-proof thrift-store suitcases with cooking supplies and other necessities for return visits. This way, they can hike in for several days of climbing with a daypack weighing only 10 or 15 pounds. Entering Camp Dingus after scrambling up a gravelly gully and threading through rock passageways feels like you’ve stumbled into a guerrilla hideout. You expect to encounter armed sentries and trip wires.

Horning estimates he has spent more than a year of his life at Reese. One time he stayed there 18 days straight. Understandably, he’s a bit possessive. Twice, most recently in 2005, billionaire Pat Broe, who owns Notch Peak Ranch just to the north of Reese, tried to negotiate a land swap with federal officials that would have moved about 5,000 acres of land, including Reese Mountain, into his holdings. Horning helped rally opponents to the deal and kept Reese in public hands.

On day three the wind had lessened just a bit, and we walked around to the Amphitheater for two overhanging classics: Twenty Red Lights (5.11c) and Fading Into My Own Parade (5.12a/b). Looking up at the latter, Friedrichs said, “That route’s all 12b before you get to the 12b.” In late morning, Horning got inspired to climb. After a couple of us had done a long, tricky 5.10, Horning laced up, tied in, and floated the route. At 65, because of exercise-induced asthma, he no longer ski-races or bikes, but he’s plenty fit. “If you’re going to hike with Dennis, you better put your track shoes on,” Friedrichs said.

The Amphitheater had obvious room for new routes, likely very hard, but I wondered who would do them. There’s not much harder than 5.12b at Reese, and not much easier than 5.10. Given the isolation, the short season, the snakes, and the wind, even this article and the new guidebook are unlikely to lure hordes of sport climbers. Which will leave Reese Mountain to those who love it.

“Dingus first invited me to Reese about 15 years ago when he saw me climb the Left Torpedo Tube (5.10+) at Vedauwoo blindfolded,” said Laird. “Apparently he figured that if I liked climbing that much, then I would love the climbing at Reese. I’ve been trying to keep up with Dingus ever since. Reese is unique, and I love sharing the experience with other climbers and seeing how the place affects them.”

In early afternoon, facing a long drive home, I started to hike out from Reese alone. A rattlesnake buzzed by my feet as I followed the faint path up Duck Creek, and I got lost halfway to the car. But I knew I was one of those climbers who’d soon find his way back. //

The Dingus Dozen

The Reese Mountain Gang’s all-time favorites

(Commentary by Dennis Horning)

Red Mite (5.9+) The CurlGreat warm-up with chickenheads, bulges, rests, and an optional 5.10 finish.

Block Party (5.10c) Hightower150 feet of fun.

Rope Tricks (5.10d) HightowerPinches and gastons rule over crimps.

Mrs. Radical (5.11a) Douglas ParkHow good are you at slopers?

Ride Steppenwolf(5.11a/b) HightowerSidepulls, edges, and pinches for 140 feet on the upper wall.

Hanging of Yellowstone Kelly (5.11b) Douglas Park“The best 11b in all of Wyoming.”

Sport Trindleberg(5.11b) The CurlA steep wall to a delicate hip-shifter roof exit, with more fight to come on the face above.

Twenty Red Lights (5.11c) The AmphitheaterAn overhanging face not yet flashed by a Vedauwoo climber—they always go for the crack.

Gamma Bursts(5.11c) HightowerBurly moves on a double-overhanging dihedral.

Aeolus (5.12B) Douglas ParkLeft-trending crack and corner system. Spectacular stemming and arête moves.

Down Converter(5.12a) The CurlDifficult stemming finishes with a crimp at the exit shaped like a light switch in the “on” position. The first 80 feet to an anchor on the right is 5.10+ and excellent.

Fading Into My Own Parade (5.12a/b) The AmphitheaterFading will happen when your hands can’t feel to grip, toes too numb to step, and your boot heels are wanderin’. (Apologies to Bob Dylan.)

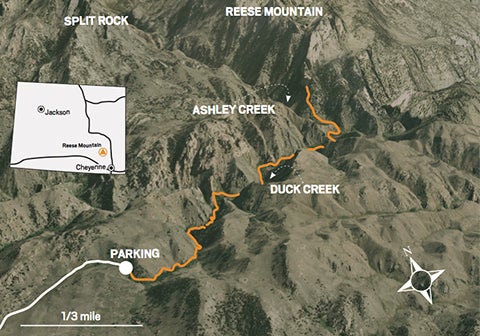

Beta

Get there Reese Mountain is in the Laramie Mountains, west of Wheatland, Wyoming. Allow about four hours of driving from Denver or eight hours from Salt Lake City. The last hour of the drive is along the gravel Tunnel Road and two-tracks across Vale Ranch; high-clearance vehicle recommended. The hike from the parking area at the top of Tony Gulch takes about 1.5 hours; the faint trail goes down Tony Gulch to Duck Creek and follows this to the confluence with Ashley Creek. Download GPS tracks for the drive across Vale Ranch and the hike here. Maps and other approach information are at mountainproject.com. Allow a few extra hours for the driving and hiking route-finding on your first visit.

Guidebook Zach Orenczak and his wife, Rachael Lynn, will release High Adventure in the Laramie Range: A Climber’s Guide ($50, extremeangles.com) in August. The book will cover Reese and many other crags accessed by Tunnel Road.

Camping There are good sites in the meadow below the crags (make sure you’re above private land at the junction of Ashley and Duck creeks; water may be hard to find in late summer). You can also camp on top of the crags; potholes hold water year-round (filtration mandatory).

Season The Reese Mountain window extends from May through September, with June and late August typically offering the best climbing, without being too scorchingly hot. Some roads may be difficult to pass in early season. Parts of the Laramie Peak Wildlife Habitat Management Area, including the approach to Reese Mountain, are closed to public access December 1 through April 30 to protect breeding bighorn sheep.

This article was originally published in Climbing in 2014.

The post Dirty Dingus McGee and the Reese Mountain Gang appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

We spot boulder problems. Sometimes we spot climbers before they clip their first piece of pro. Now imagine spotting a climber falling 60 feet.

The post A Mis-clipped Anchor Leads to a 60-foot Grounder—And a Life Saving Spot appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Climber: Douglas Kern

Location: Staunton State Park, Colorado

Date: August 23, 2014

The Scene

Asha Nanda, 21, had been introduced to climbing at a Christian leadership program in the Adirondacks. During a trip to Colorado, she and several other climbers hiked up to the Tan Corridor, high in a forested gully in Colorado’s newest state park. Douglas Kern, then 25, had just met Nanda the day before; he was one of the more experienced climbers in the group. In the afternoon, Kern led Reef On It! (5.10-), a vertical, seven-bolt sport climb. He left a rope running through quickdraws clipped to the anchors so the rest of the group could enjoy a toprope.

Nanda was the last climber to do the route. Before starting, she borrowed one of Kern’s thin Dyneema slings and girth-hitched it to her harness; she planned to use this sling to clip in at the anchor, thread the rope, and then rappel. Kern’s slings were rigged as alpine draws, with a wrap of tape cinching the sling tight next to one of the carabiners so it wouldn’t shift around.

When Nanda reached the top of the route, 60 feet above the ground, she clipped one of the anchor chains with the sling hitched to her harness. Although she was new to outdoor sport climbing, she had rehearsed anchor cleaning in a gym, and had run through the steps with one of her climbing partners earlier that day. She leaned back and fully weighted the sling connecting her to the anchor to test it, then yelled “off belay” and began untying the figure eight at her harness, preparing to thread the rope through the anchor. “I was very focused on checking and rechecking each step, and this process took approximately two to three minutes,” she says. Suddenly she heard a scream and saw the rope falling in loops below her. Then she realized the scream was her own and she was plummeting through the air.

The Response

Unbeknownst to Nanda, the single sling she’d used to clip the anchor had been compromised, either before she hitched it to her harness or while she was climbing. A loop of the sling must have slipped through the gate of the carabiner that was taped at one end, so now two strands of sling were clipped through the same biner. Although difficult to visualize, this creates a very dangerous situation similar to cross-clipping two loops of a daisy chain—in effect, when Nanda weighted the sling, only the wrap of tape around it secured her to the anchor. The beefy climber’s tape held her weight until she had completely untied and only failed then, leaving the carabiner still clipped to the anchor bolt and the now-useless sling hitched to her harness. The tape fluttered to the ground after the falling climber.

Startled by Nanda’s scream, her belayer, Julie MacCready looked up to see her plunging toward the ground, the rope looping below her. There was nothing she could do to stop her. Kern had just lowered off a nearby climb and was walking down the gully when he heard Nanda yell. Amazingly, he had no doubts about what he would do next.

“I once saw a dude fall in the Adirondacks when we were ice climbing,” he explains. “He fell 20 feet and landed on the ground right next to me. I said to myself right then, ‘If I ever see that again, I’m going to catch the person.’”

Nanda weighs about 125 pounds, and Kern is 6’ 2” and weighs 190 pounds. He had lifted weights throughout high school and college and practiced karate. As he saw her fall, he vividly remembers thinking, “She’s so small, I’ll catch her—it’ll be no problem. I’m going to stop this fall.”

No more than two seconds elapsed between Nanda’s scream and her impact, but Kern remembers that she seemed to be falling “really slowly.” He stood at the base of Reef On It!, planted his feet, and stuck his arms out in front of him, like a man about to catch a medicine ball in the gym. Nanda fell into his arms and slammed onto his chest, then ricocheted onto the ground, where she bounced “a foot or two” off a single narrow strip of dirt amid a sea of boulders and scree.

Flat on her back, Nanda looked up at her friends and said, “What happened?”

Both Kern and Jennifer Lee, another friend in the party, had wilderness first aid training and began to assess Nanda’s condition. MacCready called 911, and another climber ran down the mountain to direct rescuers to the scene. Despite the horrendous fall, Kern and Lee could find no injuries, but when rescuers arrived she was shaking and her blood pressure was falling. Rescuers carried her out of the gully and called for a chopper. She arrived at the hospital two hours after the fall. After seven hours of tests, Nanda was released—every test and scan had come up negative.

Nanda quickly returned to climbing, but says her accident taught her several crucial lessons, including to use her own gear, avoid taped “alpine draws,” and always back up her anchor. Also, she says, “If you’re new to climbing, advance cautiously and with respect to the risks.” She now lives near the Red River Gorge in Kentucky, studying nursing and volunteering for the local fire department.

While Kern’s actions undoubtedly were heroic, he was lucky too. The impact of Nanda’s fall could have seriously injured him or even killed them both. The great difference in the two climbers’ statures enabled him to absorb the blow. Kern also had prepared himself mentally for this day after witnessing a previous groundfall, and his self-confidence and desire to succeed boosted his ability to stand tall.

Kern, who is now living in New Zealand and working for an arborist, credits God for helping him save Nanda: “I think He wanted that girl alive.” Asked if he would do the same thing if he witnessed another falling climber, Kern says, “For sure! If I got a bruise, big deal. She didn’t die. Of course I’d do it again.”

Survival Tip: Give Accurate Directions

Write down or review the information you want to communicate before calling rescuers, including your location (without relying on route names, if possible), your name and number, and the patient’s status. “Rescues are often delayed by panicky callers that are unable to give a location to rescuers,” Simon explains.

The post A Mis-clipped Anchor Leads to a 60-foot Grounder—And a Life Saving Spot appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

On December 5, 2011, in Pinnacles National Park, California, Lars Johnson found his legs crushed by a 2-ton boulder. His fast-acting partners saved his life.

The post From the Archive: When a Climber is Pinned by Two-ton Boulder, Friends Launch Remarkable Rescue appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Climbers: Lars Johnson, Josh Mucci, Brad Young

Location: Pinnacles National Park, California

Date: December 5, 2011

The Scene

Three men had met because of a common interest in new routes in the obscure back corners of Pinnacles National Park, southeast of San Francisco. Before the day ended, each would help save another in extraordinary ways.

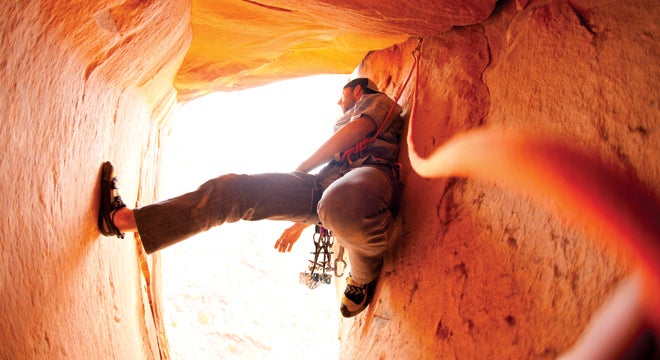

Lars Johnson, then 62, was a painter and illustrator who had done many new routes on the park’s rhyolite breccia, a well-featured but sometimes loose stone made from volcanic mudflows. Two decades earlier, Johnson had fallen 70 feet from an attempt at a new route, breaking his leg in two places. His drill bit still projected from the rock. Now he wanted to show this line and others to two younger climbers: Brad Young, then 49, author of the Pinnacles climbing guidebook, and Josh Mucci, then 30, a California climber passionate about adventurous new routes.

In late morning they reached a steep, narrow gully leading to a belay ledge below the line where Johnson had fallen. They started scrambling up the gully. Near the top, a boulder choked the path. Mucci led the way up a slot on the right side, balancing with his left hand against the boulder.

The teardrop-shaped block, about three feet in diameter, suddenly shifted and tumbled into the six-foot-wide gully, threatening to crush Mucci’s left arm and chest. Instantly, Johnson reached up with his right arm and pushed Mucci hard to the right and out of the way. Young dove to the left. Johnson had nowhere to go. The boulder rolled directly onto him.

The Response

Mucci and Young wrapped their rope around the boulder and tied it off to a tree, hoping to prevent further rolling. Throwing their weight against the rock, estimated to weigh two tons, they were able to move it an inch or two, freeing Johnson’s twisted left leg. But his right leg was trapped up to the hip.

Young, who knew the area best, ran for help. He reached the normally desolate West Side parking area after a half-mile bushwack and a mile of trail to find, quite luckily, park rangers and a trail crew. They radioed for more help and a helicopter, and ranger Mark LaShell and two trail crew left for the accident scene almost immediately, with Young leading the way.

Back at the boulder, Mucci dug at the stony ground for about 45 minutes, despite a badly injured wrist. Finally, Johnson was able to squirm out with Mucci’s help. Johnson had a compound fracture in his right leg and many other injuries. “I got him seated, splinted his broken leg using the rope and a leash from a hammer, and elevated his leg,” Mucci says. More than two hours after the accident, a helicopter dropped a nurse and paramedic on a nearby ridge, while other rescuers cleared a path down which they could lower Johnson in a litter. In fading sunlight, the chopper came in “right off the deck,” Mucci says, and then short-hauled Johnson to the parking area for a transfer to an air ambulance.

As the professionals took over, both Young and Mucci ended up making their way to the parking lot alone, very conscious of how close the margin had been.

“Had it just been me there with him, Lars would have been dead,” Mucci said. “Had Brad stayed and I went down for help, Lars would have been dead. If the ranger team hadn’t been there, he’d be dead. It all had to come together. And it came down to 15 minutes.”

Even though time was critical, Mucci and Young took crucial steps that professional rescuers recommend: They secured the scene to prevent further injuries and prepare the way for a rescue; they made a plan and effectively used the tools they had; and they assigned the right people to each job—Mucci, who had wilderness EMT training, tended to Johnson, and Young, the guidebook author, went for help and led rescuers to the victim.

Johnson mostly recovered from his injuries and returned to painting (studiolarsjohnson.com) and exploring California’s mountains. Josh Mucci says he experienced PTSD that affected him for several years. “In gullies, with loose rock, I’d just burst into tears,” he explains. Mucci now lives in San Diego, and Brad Young lives in the northern Sierra foothills. Both still develop new routes. But not on that obscure backcountry wall in Pinnacles. All three men have sworn they’re never going back.

Survival Tip: Take Care of Yourself

“Making certain that you and your partner are safe and secure is always rescue step number one,” Simon says. This includes a good anchor and adequate protection against rockfall, foul weather, or falling temperatures. “You are no good to your partner if you get hurt or incapacitated.”

The post From the Archive: When a Climber is Pinned by Two-ton Boulder, Friends Launch Remarkable Rescue appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Terminally pumped? Follow these tips to achieve a restful stance on vertical rock, steep caves, corners, and more.

The post Expert Advice for Advanced Resting Tactics appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

The best way to maximize your staying power for enduro-packed routes is by resting more often and more efficiently during the climb. You may do endless training laps for stamina, but learning to cop strategic rests mid-route is more likely to win you the onsight on any terrain.

Vertical Rock

Your legs are much stronger than your arms, so look for stemming opportunities to relieve your fingers and forearms throughout a route. Corners are the obvious places, but many times you can also stem between knobs, pockets, ribs and tufas, or other rock features on a flat wall. To rest on a face climb or arête, wrap your instep over a crystal or edge, rock onto it, and then squat onto that foot, with the other leg dangling to keep your weight close to the wall.

Stemming and thin face climbing may tire your feet and calves as much as your fingers and forearms, leading to imprecise footwork. Try standing on a good foothold with your heel—instead of your toe—to rest your lower leg. Alternate feet if possible.

A knobby wall provides plenty of opportunities to rest your fingers. Curl your thumb or crook your pinkie around a knob to give your fingers a chance to recover. When you reach an extra-large, flat edge, rest your forearm on the shelf instead of hanging on your hands.

If you have crack climbing skills, you can often find great rests on a face climb by hand- or finger-jamming in horizontal cracks or vertical pods. Pods or flares in a crack provide great pit stops during long laybacks—cam one foot into the pod, so you can stand up straight, get your weight over your foot, and stop pulling as much with the arms.

Overhanging Rock

Stemming is even more essential for resting on overhanging rigs, where your arms and core do most of the work. Even the shallowest corner or groove may present an opportunity for a quick stem and shake. When two planes of rock are too close together for effective stemming, you may still be able to milk them for a rest with a drop-knee: Turn your body sideways and drop your inner knee toward the ground, smearing with both feet in opposition, as if you’re chimneying. With a good enough drop-knee, you may be able to lower one or both hands for a rest.

While stemming or dropping a knee, your upper body can help ease the strain on bulging forearms. Look for opportunities to “scum” a hip, shoulder, or even your head against a dihedral wall or a roof to hold yourself in balance.

The ultimate scum is the knee bar, in which you wedge your lower leg between two surfaces, with the foot and knee in opposition. Knee bars are commonly found under small overlaps or inside corners, with the leg turned sideways to press the knee against the corner wall. Strong abs will be required to use a knee bar for very long on an overhanging route.

The heel-hook is the most common rest on this terrain, and toe-hooks may also offer a good rest—an extreme version is the bat hang, in which the toe is hooked over a lip or inside a big pocket, and you hang completely upside-down to shake out. Knee-bars, heel-hooks, and other core-intensive rests often reach the point where loss of strength in your abs and legs outweighs the gains in your forearms in just a few moments. Often it’s best to shake out, chalk up, and then move on.

Get the Best Rest

Hard onsights and redpoints often come down to managing your rests well. As you suss out a climb from the ground, try to identify good rests along the way. If the rock is vertical or overhanging, you’ll want to climb without pauses between the rest positions.

When you get to a rest, hang straight-armed from the hold. Use an open-fingered grip (not a crimp), and see how little strength you can use to hang on. (Think skin friction versus grip strength.) Vary your hand position: “Piano” your fingers along a small edge to give each finger a breather; alternate fingers in a pocket; and switch to different holds, if possible, to vary the grips.

Hopefully the rest will be good enough that you can shake out each hand alternately. If necessary, adjust your feet and body position to keep your weight over your feet as you switch hands. Gently shake the hand and your loose limb, and wiggle the fingers. The goal is to get the blood moving and thus remove lactic acid from your pumped muscles. (A quick shake between holds when you’re climbing is also effective and should become habit.) Trainer and author Eric Hörst helped popularize the technique he calls “g-tox in” which the climber alternates shaking out with the hand overhead and dangling at his side. Shake out in each position for five to 10 seconds before switching. A study by British researcher Luke Roberts in 2005 showed that this method is significantly more effective at speeding recovery than the simple dangle-and-shake, probably because gravity helps circulate blood out of pumped forearms in the overhead position.

Effective recovery is as much about relaxing the mind as resting the forearms. While resting, don’t focus on anything specific. Gaze into the middle distance, take slow, deep breaths, and let your thoughts grow calmer with your exhalations. If the stance is excellent (with most of your weight on your feet or in a comfortable knee-bar or heel-hook), stay in the rest position until your breathing and heart rate slow to near normal. Take a moment to visualize the next sequence or organize your gear, and then purposefully resume climbing.

https://www.climbing.com/skills/you-suck-how-to-deal-with-regression/

The post Expert Advice for Advanced Resting Tactics appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

These famous climbing accidents are equal parts gripping and inspiring. If any reader should someday find themself in such a desperate situation, we hope they too will remember how others endured, living to climb another day.

The post Six Near-death Climbing Accidents Analyzed and Explained appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Most climbing accidents happen suddenly, progress quickly, and they’re soon over. A stone falls, a piece pulls, a leg is broken. A rescue begins. Very few climbs result in true survival situations, in which the misery and uncertainty are prolonged for days or even weeks. Because of their rarity and inherent drama, many such incidents become legendary tales. Others remain private experiences, known only to family and friends.

But we also hope to inspire, for survival stories reveal the hidden capacity within many of us. Recounting their accidents, several of the climbers featured here said they drew strength by recalling Doug Scott’s epic crawl down the Ogre. And if any reader should someday find themself in such a desperate situation, we hope they too will remember how others endured, living to climb another day.

Crawling off the Ogre

- Mo Anthoine, Chris Bonington, Clive Rowland, Doug Scott

- Baintha Brakk, Pakistan; 1977

- Scenario: Two bone-breaking falls above 21,000’

- Injuries: Broken legs, ribs

- Elapsed time: 16 days

On July 13, 1977, British mountaineers Chris Bonington and Doug Scott summited Baintha Brakk (aka The Ogre), a 23,901-foot rock and ice tower in Pakistan’s Karakoram. The two men and their four teammates had spent more than a month attempting various routes up the complex peak. But any joy they felt after finally reaching the top was erased when Scott slipped on ice during the first rappel and pendulumed violently into a rock wall, breaking both legs above the ankles.

Bonington and Scott were 9,000 feet above base camp, and the sun had set. Though they had fixed ropes up the first part of the climb, descending the upper mountain would require a long traverse over the Ogre’s west summit. Just below the accident site, Bonington and Scott improvised a bivouac at over 23,000 feet without food, a stove, or even down parkas. The next morning, they continued rappelling and then were joined by Mo Anthoine and Clive Rowland, who had spent the night in a snow cave below the west summit. The three men helped Scott crawl back to the cave, where a storm pinned them for two nights.

On the third morning after the accident, despite the continuing storm, the team forced its way to the west summit, with Scott manhandling his way up ropes with jumars. It took him six hours to climb several hundred feet. After a night in another snow cave on the far side of the west peak, they continued downward, still in the storm, with Scott belayed between two partners as he crawled along the ridge. Later that day, Bonington rappelled off the end of two ropes of unequal length, plunged about 20 feet, and broke two ribs.

That night, they reached their tents, but the storm intensified once again, and they feared they’d never find the fixed ropes in the whiteout. They were forced to spend a second night at this high saddle—the sixth night since the accident—still above 21,000 feet. Their sleeping bags were soaked, and they hadn’t eaten solid food for days.

Finally, the weather broke. Bonington couldn’t use one hand and could not speak; he feared he was developing pneumonia. But after one more night in their tents, the team started down the fixed ropes. Rappelling was easier than crawling for Scott, and they all made it down to the glacier that day.