Francis Sanzaro's classic book 'The Craft of Bouldering' puts bouldering into conversation with disciplines like dance, skateboarding, painting, martial arts, and parkour.

The post What Exactly Are We Doing When Trying Hard Boulders? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Author’s note: The Craft of Bouldering is a revised and updated edition of a classic climbing text, The Boulder: A Philosophy for Bouldering. Why the new name? I don’t know exactly, other than the publisher who bought the rights wanted to put the title more in line with The Zen of Climbing, which is also in the series.

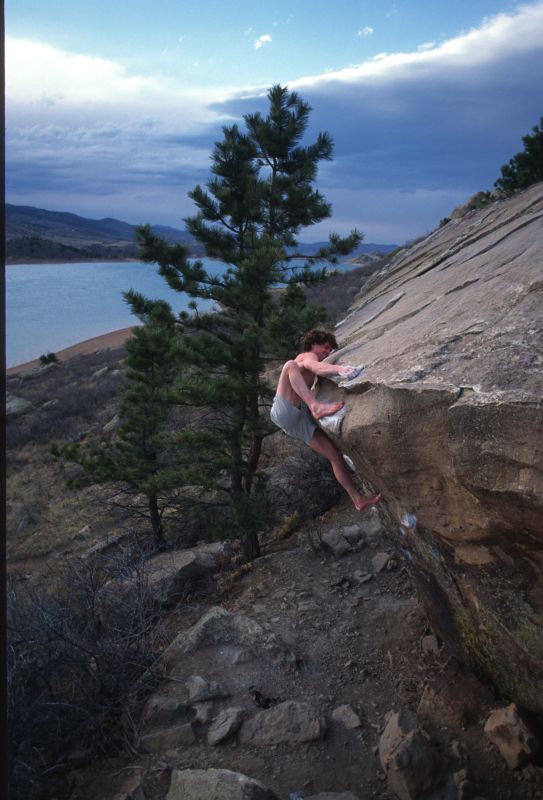

My purpose in writing The Craft of Bouldering was twofold—to make you a better boulderer (and climber in general), but also to put bouldering into conversation with disciplines as varied as architecture, dance, skateboarding, painting, parkour, martial arts, and gymnastics. That exercise, as literary as it is philosophical, helps us to better understand what it is we are doing when trying hard boulders. In short, this book intends for us to think about our bodies and our sport differently. When I first tried climbing, around age 13, I was a gymnast, which is also a movement art, just as pure as bouldering, with an analogous bodily language. But once I was a climber, I fled the gym and spent the next few years bouldering in the woods of Maryland, on shit rock infested with poison ivy. We bleed. We cleaned. We topped out. Bouldering was a language I learned fast, and one which I’d spend over a decade refining. I hope some of that comes through.

— Francis Sanzaro

Below is an excerpt from The Craft of Bouldering, published by Saraband.

No Style Needed

The man who is really serious, with the urge to find out what truth is, has no style at all. —Bruce Lee

To a boulderer, a problem is infinite in its own little way, forever changing the way it greets us when we climb on it or even look at it, never boring us with its fixed number of holds but always opening toward us, always revealing a new aspect of itself, and, conversely, of us. The slightest bit of humidity (or frustration) can make a hard problem feel impossible—whatever your limit is—just as a split tip can set you back on attempts for days.

To boulder is to be put into a space that is, well… only like bouldering, which is both obvious, and not. Once you are hooked, a boulder is no longer a chunk of lifeless stone but a giant apparatus to which we sacrifice our greatest energies—something to which many, myself included, devote years of prime physical strength. Contrived? Yep, but what isn’t?

In time, we are defined by the stone as much as it is defined by us, by its speeds, textures, holds and behaviors; our muscles and tendons adapt, bigger lats, bigger triceps for mantels, or, equally, our bodies break, in which we are defined by it much more. As sprinters of the climbing world, no form of climber is as injury prone as the boulderer.

When we see boulders, we scrub, touch, inspect and analyze every inch of their bodies, looking for a way up. We search for a line to ascend, which will allow us to leave our mark on the sport, something lasting, a first ascent. We are looking for a creative act that will eventually produce a performance that others can share and admire. Bouldering is unique in that unlike a famous football goal or touchdown, the consequence of the first ascent of a boulder problem is a publication of its movement sequence, like putting down notes to a new song on paper so others can play it. This solution is postulated against the theses of other possible solutions; it is a brave thing, really.

Once you are hooked, a boulder is no longer a chunk of lifeless stone but a giant apparatus to which we sacrifice our greatest energies

Hopefully, we have found the unique sequence—since the success of our problem is often judged against other possible solutions (or lack thereof). A simple kneebar or a crimp a first ascensionist didn’t see can significantly drop the grade—not an ideal scenario—bruising the ego, but, more importantly, indicating that they didn’t look carefully enough. Fontainebleau bouldering sensei Charles Albert, who climbs barefoot, had his first V17 downrated by two potential grades because Nicolas Pelorson found a better heel hook. Because we boulder with different bodies, bouldering will forever be a dance requiring reinterpretation. As it is with stone carving, so it is with bouldering—look five times, strike once. We succeed to the point that others don’t. That is, we succeed in cataloguing our brief performances into bouldering’s archive when we are the first person to perform this movement. This act is both extremely solitary and public—a boulder problem’s solution is ultimately found by an individual at a single point in time, yet its solution is often, but not always, a collaborative agreement born from a team mentality. Therefore, the boulder problem lives only insofar as it is remembered and memorialized by those for whom the act itself is of the utmost importance.

A problem is a short performance, lasting about a minute or two. Despite the prep and training and obsession, when you are bouldering at your limit, a hard send feels like a gift, often coming at the most improbable of times—at the end of a long session, for example, or on a ‘rest day’, or on your last try before you have to pack things up and drive home. This was the case with Ben Moon’s first ascent of Black Lung (V13) in Joe’s Valley, which, in legendary fashion, he sent on his final go of the trip, after having packed up and gone for the car, only to turn around because the snow stopped and conditions got prime.

Bouldering will one day go extinct. Like the ancient and not-so-ancient sports of Harpasta, Jeu de Paume, Equilibrium, Tug of Hoop and Trigon, bouldering will no longer be part of the cultural imagination. Bouldering will no longer “live,” for sports have lifespans, like people. One day, the lights will be turned out inside the boulders themselves—the life they once had, which we boulderers gave to them so passionately, will die, and that vision and yearning we had for them will die as well, which isn’t to say it was pointless, quite the opposite—all the more meaningful.

Before we “found” them, boulders were anonymous faces of stone in varied landscapes—forests, mountains, valleys, neighborhoods, Central Park—and we walked past them or simply marveled at their shape and color. Now they are apparatuses for the most brutal, pleasing, modern athleticism, a combination of art and instinct, max exertion, and softness. The combination of said skills is what it feels like to be in that bouldering space.

Non-Habitual Movement

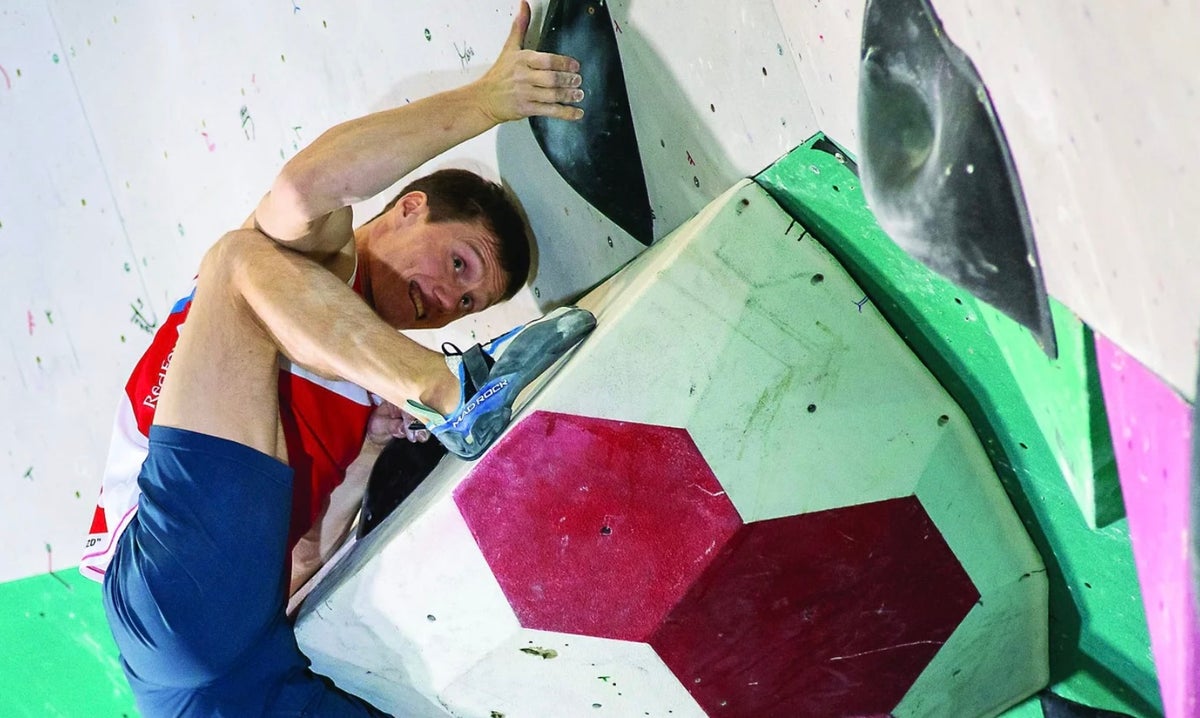

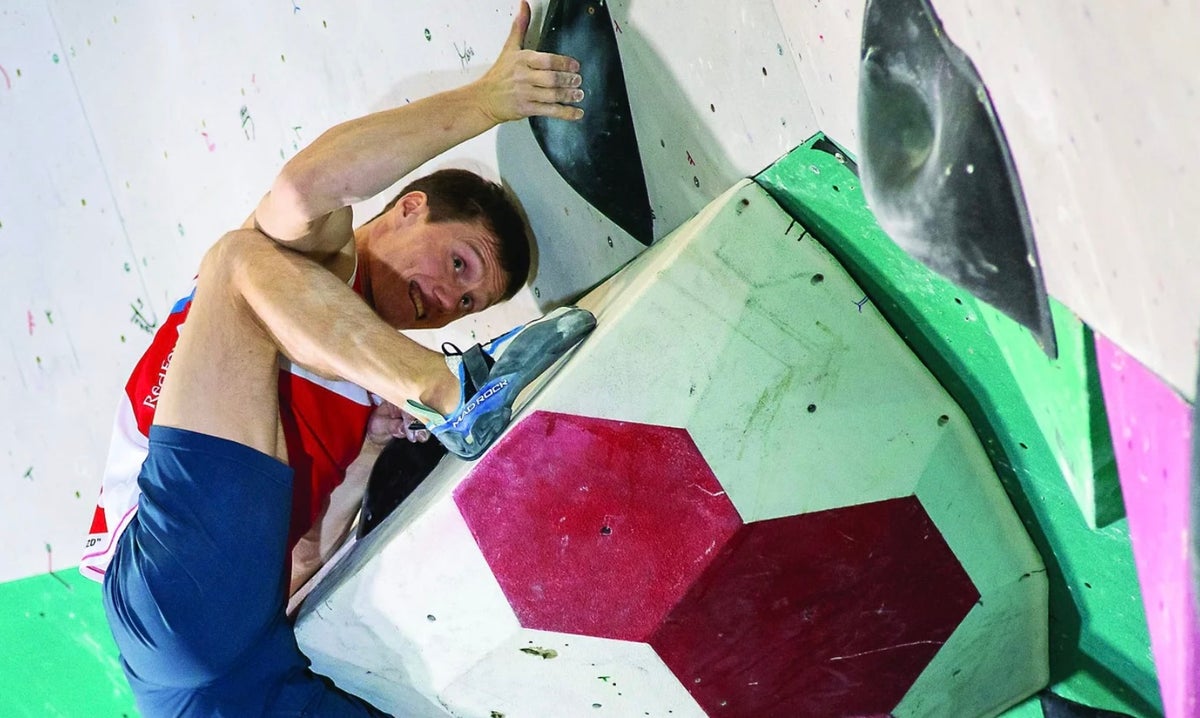

Non-habitual movement, which is the breaking of our formal movement patterns, is the sine qua non in bouldering. In general, sports work within this category, but not all require the violent positions that the boulderer must undergo.

Solutions to problems work within the non-habitual range of movement. In what is now an internet classic, the “wizard of climbing” (a.k.a. Dave Graham) speaks of “imaginary boxes” that one must get into in order to succeed; boxes which, one might add, take a long time to construct. Likewise, a golf swing has these imaginary lines, the swing itself being such a finicky thing that a professional golfer can “lose” his swing for an entire year. Tiger Woods went through several swing coaches to get his back again (he was critiqued for this type of swing ‘outsourcing’), and it was a sad day when he could be heard saying that he “just wasn’t playing well today” because of a glitch in his neutral position mechanics. Swinging from a place of instinct only to then sweat the minutiae of mechanics is like being stranded on a deserted island—one has suddenly been alienated from a “place” once known intimately, and now, will do anything to rekindle the relationship. The calculating mind does indeed help in practicing a swing or learning the moves on a problem, but it is a hindrance once it’s game time and you need to perform. As boulderers, we all know how mechanical some movement feels and how instinctual other movements, often within the same problem. A quarterback loses his toss, a pitcher his fastball, a batter her swing, a hurdler her step—this is just the nature of athletics, and there is no formula: one must wait and experiment and hope. Body position and posture-in-movement remain as elusive as anything.

Like what you read? Check out Sanzaro’s book here.

The post What Exactly Are We Doing When Trying Hard Boulders? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Climbing is hard enough as is. Avoid stunting your progression by avoiding these 7 easy-to-fix mistakes.

The post The 7 Most Common Beginner Climber Mistakes appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

The most common thing holding beginner climbers back is themselves. After climbing for over 25 years, here are seven mistakes I’ve seen rookies commonly make.

1. You are trying something too hard.

Too often, a V5 climber spends the majority of their time on a V8, or a V2 climber on a V5. Bad idea.

If you must try something three grades harder than you’ve done, just do it for a bit. And do it for the right reasons. Don’t obsess. About three to four tries per session. If you have a project, keep it to one to two grades above your max. That builds confidence. Getting shut down all the time sucks. And the longer you spend on moves you don’t belong on, the greater chance you have of getting injured. Also, more wins is better—you are going through the motions of what it feels like to put something together. The latter is invaluable.

2. You are not warming up properly.

You do a few problems (or routes) below your ability. Then you get a drink, have a chat, and think you’re good to go. You are not.

I don’t care how old you are, warming up takes 30 to 45 minutes. If you leave the office at 5:30 to go to the gym, do 50 jumping jacks and some push ups, or even run in place, before you get in the car. Getting the blood pumping and heart rate up is key to any warm up. By the time you arrive at the gym, you will notice you are looser and ready to go quicker.

Related: Getting Strong is Half the Battle. But Don’t Forget the Other Half.

3. You are falling on the bouldering wall and letting your legs absorb the fall.

Keep doing this and a knee, ankle or hip injury is not far off.

Learn the art of rolling backward when you fall. This is assuming, of course, that your gym has good pads. Land in a squat with your momentum moving backward, from your butt to your back. Roll like an egg, but not so much so as to get whiplash. Gymnasts have been perfecting the art of the backward roll for decades. Falling in the bouldering cave is the most common form of injury for gyms. Practice falling and don’t add to that statistic.

4. You are too scared to fall while lead climbing.

If you are scared to fall, you’ve got a problem on your hands. Of course, a wee bit of trepidation is okay. But if you generally don’t like to fall, you need to practice ASAP. This fear alone will keep you from reaching your potential as a climber.

Practice taking small falls on toprope, then small falls on the (overhanging) lead wall. Then bigger falls on the lead wall. On your warm up, climb to the top, then downclimb and take a whip on the last bolt. I have seen so many people not send because of their fear of falling. But becoming comfortable with the whip is in your control. It should be the first thing you master.

Related: How to Conquer Your Fear of Falling—Even in the Gym

5. You are trying to climb with good posture.

Are you keeping your back straight and slightly arched, like you would when doing squats? This is not the weight room everyone—this is climbing. There’s no such thing as good posture in climbing. There is only what works—the cruel fact of natural selection in terms of movement.

If you must, the best “posture” is to stay loose, moving, and flowing between holds. Keep your form adaptable, never stiff … unless, of course, you need to be stiff. Climbers talk about being “in position” for a move. Moves and positions are always changing. It is never a one-size-fits-all scenario. Good “posture” is only applicable on a per-move basis.

6. You aren’t resting enough between burns, AKA, the rapid fire.

For the entirety of my twenties, I was guilty of this. I’d fall then get frustrated and hop right back on, typically with the same result: failure. Force yourself to take rest, even if you don’t think you need to. Muscle needs to recover after exertion, period. End of story.

7. You are wearing horrible shoes.

Just. Stop. Doing. This. Get yourself a good pair of shoes. Don’t buy the cheapest. Buy the shoes that suit your needs and have the best fit. You just spent $30 on a kale salad and a beer last Thursday night, and you won’t spend an extra 30 bucks for climbing shoes that you will use three times a week for months? No sense do you make.

Watch Avianny Frady talk about some of the climbing mistakes she made as a beginner

Francis Sanzaro is the author of The Zen of Climbing and The Craft of Bouldering. Learn more about him here.

The post The 7 Most Common Beginner Climber Mistakes appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Enjoy these three chapters—The Summit, Copyright on Enjoyment, and Erasing Art—from our former Editor-in-Chief's newest book, 'The Zen of Climbing'

The post Why Hard Sends (and Private Islands) Won’t Make You Happy appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Francis Sanzaro’s newest book, The Zen of Climbing, is officially available for purchase. The long anticipated volume dives in to the intersection of climbing and philosophy, discussing the psychological determinants of success and the art of living (and climbing) in the moment. The former editor-in-chief of Rock and Ice, Gym Climber, and Ascent has been climbing for more than 3o years. His first book, The Boulder: A Philosophy for Bouldering, received critical acclaim and is now in its second edition. The Zen of Climbing is available on Amazon and at Barns and Noble. Enjoy the three excerpted chapters below and stay tuned for a review.

***

The Summit

It is at the top where you find the bottom.

I remember watching a TV show about a billionaire who developed his own private island near New York, adjacent to Manhattan. It took him years of painstaking work to build. He spared no expense. Then he finished it. Standing there, on film, pondering the sea and his new home, said he had expected to have great thoughts on his private island. But, after the last construction worker left the site, it turned out nothing had changed. He still had the same old thoughts. After a few months, he sold the place. He looked sad. He had expected so much.

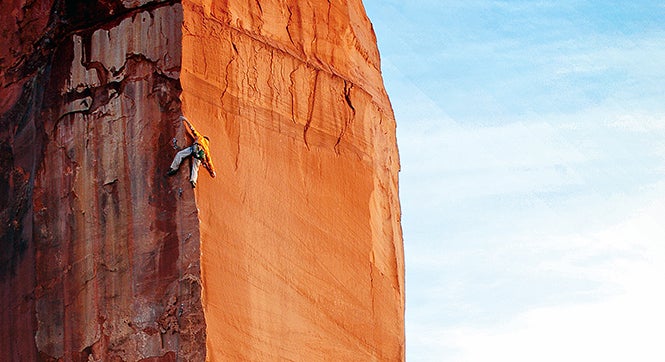

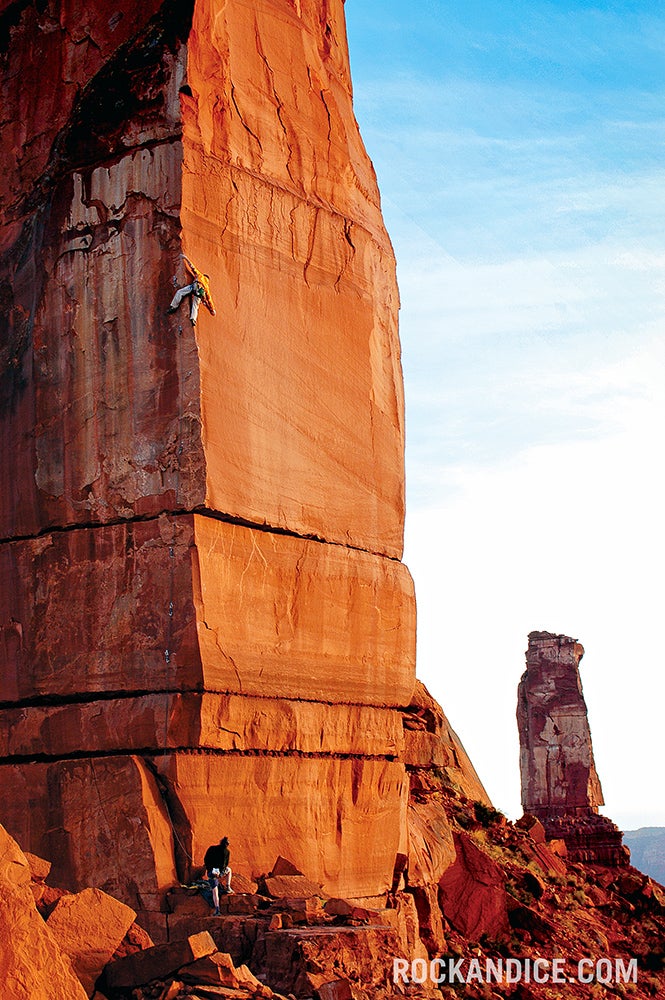

We’re lucky as climbers. The places we go are inspiring, the stuff of billboards and multi-million-dollar commercials—desert towers, ribbons of ice, soaring ridges and cliffs of blue limestone. The climber’s terrain is idealized, given the romanticization of the summit. As far as nature is concerned, the Western imagination is ‘topophilic’ (in love with place). The earliest goals in climbing—in the 1800s and first half of the 1900s—were predominantly those of being the first to stand on top of something. Such was the case for Mont Blanc, the Matterhorn, then into Alaska, the Himalayas. Climbers were “conquerors,” and the visual iconography in that time was one of a general marching into battle along with his soldiers (and porters). Then, after most peaks were topped out, alpine climbing moved to more technical faces while, starting in the 1970s, rock climbers and boulderers found difficulty as a reward. In America in the 1950s and ’60s, however, John Gill’s focus on form and inner feeling was an exception. Gill, with a modest background in gymnastics, viewed climbing, and especially bouldering, more in terms of gymnastics than anything else. For Gill, grace in execution was paramount.

The top is a legacy of climber-thought, drawn from our deep history, popular imagination and our own romantic leanings that overcoming difficulty, and hence, achieving a new level, is the main goal. The problem is that climbing is equally expressive—a dancer would not go to the studio and consider it a good day if they only did a hard sequence, as if, once they had done it, they could move on to another hard sequence. A dancer wants to feel flow. A dancer wants to be in it. The dancer wants to become the dance, to merge with their body. A dancer chases a feeling, a state of bodily affairs. Ueli Steck, the late Swiss alpinist and holder of multiple speed records up the most dangerous alpine faces in the world, including the North Face of the Eiger, once said: “Mountaineering is a transient experience. I need to continuously repeat it to live it.” Steck is right. Doing a difficult alpine climb is satisfying, but it’s a label post-performance, and, hence, a dull concept we apply to something beautiful and timeless. We too build our private islands—visions of success—and we convince ourselves that once we achieve it, we’ll be like the billionaire. We’ll stand on the shores of our hard sends and be different people, have better thoughts. But that’s never the case. We are chasing ghosts. It is better to go into a hard project, or trip, convincing yourself that doing such and such a route will not change a thing about you, or your life. Do that with climbing, and your trip changes. For the better. Do it with the rest of life, and you are starting to taste Zen.

Copyright on Enjoyment

The art of a mindful body is the art of elite athletics.

Elite climbers are no more satisfied with their sport, nor do they enjoy it more, than average climbers. A pro surfer has no more fun than an average one. But there is a caveat: a seasoned athlete embodies the possibility of deeper affects as a result of their trained body, which can lead to a richer, more meaningful experience.

When you have muscle and neural memory in certain movement patterns, the body provides a potpourri of sensation a beginner does not have access to—namely, climbing gracefully creates pleasant sensations in the body that climbing clumsily does not. Give a beginner a javelin, tell them to toss it, and their focus will be on gripping the thing and trying to throw it as far as possible. Throwing the thing won’t feel very beautiful. Their minds are riveted to base execution. Their bandwidth of attention is taken up by the mechanical complexities of completing the task. As for climbers, a beginner applies too much strength at the wrong time, ignores their footing, overgrips, undergrips: a sense of awareness in and of the movement is inaccessible. They are overthinking it. Underthinking it. A first-time javelin thrower might like it, but they don’t experience deep joy in tossing it. Give the javelin to an expert, and they will also concentrate on execution, but their bodies know the basics, which loosens attentional space for a deeper engagement with the movement, like being able to watch a beautiful film without having to take notes. Because it is an experience, and all experience has shallow and deep forms of engagement. All athletic movement has levels of engagement as well. It is this deeper engagement that builds craft, practice and mastery. Top athletes in any sport are able to apply no more, nor less attention than is needed. This is the age-old formula for your own quest to be a better athlete.

To borrow a term from critical theory, a seasoned athlete is more affective, affect defined as potentiality to feel, a state of being receptive to the energies the body and world provide. Affect is a pre-verbal possibility in which we can be moved. Affects are not feelings or emotions but indicators of our ability to be moved by the former. Top athletes have the potential to be deeply affected by movement because of their psychosomatic investment in a specific set of movement patterns. Movement is memory, and memory spans the spectrum of cognitive functions because it is the inter-connective tissue of temporality: memory spans time like nothing else can. Movement for seasoned athletes is an echo chamber where previous movements come alive, where they interact with the present, where they built the future. Where they analyze, compare, get drawn into the well of the body’s deep psychosomatic history. It’s just a fact of movement that athletes move with deep history in their muscles, thought patterns and tendons. Muscles produce feelings. Doing something well is not just a concept we give to ourselves, such as “It sure feels good to be good,” and that’s the reward. Rather, it is autotelic, which means the purpose of doing something well is sufficient unto itself. The reward is in the moment, and, for that reason, a concept cannot capture it.

Erasing Art

The art of erasure ensures that creative perception is highest priority.

American poet and artist Jim Dine put on retreats and clinics. At the end of each day, he told his students to erase what they have done. The students are always shocked, if not offended. They look at him weirdly. They hesitate.

Did he say what I think he said?

They are puzzled.

WTF?

They look at each other.

This is my best work.

This is what I paid for.

Yes, he did say that.

Erase it all.

With great reluctance, the students erase eight to twelve hours of hard work in seconds. After a few days of working and erasing, however, Dine has made his point—most artists are too attached to the outcome and not enough on drawing. His first point: when you are figure drawing, what matters is looking, looking carefully and patiently, and not caring what the result looks like because if you look carefully enough, the result takes care of itself. And another thing happens: the act of looking becomes the priority, and hence, you become a better artist because you are a better “looker.” Riveted attention to the task is the goal. His second point, implied in the first, is that it is natural to be future-oriented and let attachment take hold. We often default to that position. After you have internalized the art of looking, only then, at least in terms of realistic drawing, can you take liberties in attention, that is, you can (like an expert javelin thrower) explore style in the execution. This happens because you have the bandwidth.

The history of Zen art testifies to the power of internal awareness, because listening is subtracting. Clearing the mind from any preconceived notion of what you think you need to paint allows that perfect moment when the brush brushes itself. D.T. Suzuki wrote of Zen art, “Technical knowledge is not enough. One must transcend techniques so that the art becomes an artless art, growing out of the unconscious.” Calligraphy, of which Zen art has a long history, seeks that moment when the artist’s arms and hands move without cognitive distraction, and it is said it can take a lifetime just to perform the simple task.

As a climber, when you start ‘erasing’ like one of Dine’s students, you need to develop deep patience. It can take years, but the payoff is tremendous. In place of thinking that you will either succeed or not, always a very imprecise way of thinking, awareness needs to be on the only thing that matters—execution. Strategy is execution as well, but to pull that off, you need your base layer of execution to be seamless. In his process of doing the world’s second V17/9a at Red Rocks, the Colorado-based climber Daniel Woods described to me in an interview how he had to learn the art of erasure, of removing attachment from the outcome: “At first I was too consumed about the send, rather than just flowing with the move, like taking it move by move and focusing on my breath…and I’d be like, man, this could be the one or this could be the one, you know, I was too. I was too focused on the send rather than being present. And I had, like, we had probably a week and a half where I just had that feeling. And then suddenly, I just had to flip my head and be like, look like, every, every day now is just a session, we’re going to start and just see how far we can get. I think I just told myself every time to just see how far you can go, like, create, like, focus on your flow, focus on your breath. Like, create a good rhythm and have fun on it. You know, like, you’re climbing on a line that has sick moves. It’s hard. It’s challenging, but just have fun, you know. And when I started getting into that mentality, all that pressure kind of vanished, and I just, I was climbing better on it.” Wood’s experience grew because he took away.

Also by the Author:

The post Why Hard Sends (and Private Islands) Won’t Make You Happy appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

And how to prevent these simple mistakes.

The post The Perils of Plastic: Gym Climbing’s Most Common Accidents appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Cassie has been climbing for about six months, mainly toproping, but is beginning to dabble in the bouldering cave. Last week she climbed her first V2, and she was stoked. Upping the ante, she’s recently been throwing herself on a steep V3, which ends with a slightly dynamic move, a big left-hand bump to the finishing jug. Finally, she gets to the last move, though with a mild pump. Tasting success, she goes for it. But no dice. Off she comes from the top of the bouldering wall, careening sideways. Her left leg, stiff and extended, hits the mat first. She fractures her tibia and sprains her ankle.

Cassie is fictional, but her injury isn’t. In fact, according to estimates by industry insiders, this exact type of injury—of intermediate climbers injuring their legs or ankles while bouldering— accounts for 40 to 50 percent of all gym accidents.

Is there such a thing as safe climbing? No, there isn’t. There are too many variables and opportunities for human error, the cause of the vast majority of accidents.

“Safe,” one CEO of a major gym retailer told me, “is a four-letter word.” Rather, managers prefer the term “management of risk.”

In researching the most common types of gym accidents, I spoke with the owners and CEOs of some of the biggest gym companies in the U.S., and, as one might expect, their stories were similar. The following list ranks gym accidents (from top to bottom, and most common to least) as they are found in the three main sections of your gym: bouldering, toproping and lead-climbing areas.

Bouldering

Sprained ankles or wrists, broken bones and hyper-extended knees and elbows.

Because of its simplicity and immediacy, many beginner and intermediate climbers just start bouldering. But no one would arrive at a gymnastics facility and start doing front flips. Point being: true, you can just start bouldering, but if you’re new to the sport, you’re asking for it. According to one owner, “These accidents happen when climbers lose track of where the ground is.”

The harder you boulder, the more you will be exposed to moves that put you sideways or require you to jump or heel hook with your foot by your face. The good news: these accidents are largely preventable. I’ve been bouldering for 20 years with lots of highballs tossed in for good measure, and in that time I’ve only had one sprained ankle, about a dozen years ago.

First, learn how to place mats properly, if your gym uses them. Second, do proper dynamic stretches for your ankles and lower body for no shorter than 10 minutes. Even if you’re already “feeling warm” from leading or toproping, your soft tissue and ankle joints are not. Third, take your gym’s bouldering class, and if the instructor doesn’t talk about body awareness, ask about it. The best way to prevent bouldering injuries is to start falling. Body awareness is crucial, and falling is an art. Unless you pop off completely unexpectedly, which is rare, your body has ruminations that falling is imminent, and when that happens, you should be thinking about how you want to land; i.e., it should always be softly. See also the bouldering tips in “Errant Spot and a Shattered Leg” for a lengthier treatment of the art of falling.

Toproping

Improperly tied knots by experienced climbers; improper ATC threading.

Injuries from unfinished or mis-tied knots are commonly caused by experienced climbers who let their guard down. As common sense would have it, newer climbers are stricter about using proper protocols (verbal commands such as “Climbing,” “Climb on,” etc.) than experienced climbers, who might have become lax. Prevention: never let your guard down, ever, regardless of your skill level. The stakes are just too high. Whatever commands you use doesn’t matter, what matters is that you are communicating with your belayer about what’s happening—before climbing or lowering—and that you have checked each other’s knots or devices. Good communication should also prevent another common accident: an improperly threaded ATC, where the rope is pinched through the device, but not clipped into a carabiner.

Outdoor crags are not immune, either. The majority of climbing accidents are user-generated: rappelling off the end of your rope, taking people off belay when they shouldn’t be, or just plain bad belaying. If everyone tied knots in the ends of their ropes and used proper verbal commands, my gut tells me that a large number of all climbing accidents would vanish overnight.

A second common accident in the toprope area of any gym is associated with auto-belays. One gym owner relayed the story of how a frequent auto-belay user got to the top of a wall before those around him yelled up to tell him he wasn’t clipped into anything. The auto-belays had been sent out for maintenance. Thankfully, the climber downclimbed and was safe. “You can’t imagine how often we see that,” the owner said. Now that most auto belays have a feature (such as a nylon tarp clipped to the wall and rope) to prevent individuals from simply climbing without being reminded to clip in, these accidents are becoming more infrequent. However, each owner stressed that these accidents do occur, despite safety measures, and that auto-belay accidents can be severe.

Lead belaying

Botched clips, smashing into the belayer, weight differences.

Every gym has its own protocols for lead belaying, and you should stick to them. As a lead belayer, you should always anticipate a fall and never stand directly below the lead climber. As the leader climbs, move positions to ensure that you and the leader are out of each other’s way in case of a fall. However, even if you (as belayer) are out of the way, a big weight difference between the leader and belayer can have deleterious effects, such as the lead climber smashing into the belayer; according to all sources, this was the most common type of lead climbing accident. If you are belaying someone much heavier than you, look for anchor points on the ground (assuming the gym has them), or, when belaying, beware of extra slack in the system, which would pull you off the ground unnecessarily. When in doubt, ask someone in your gym for the official protocols.

A common accident is hitting the deck as a result of having too much slack out. Often, a beginning leader may try to clip too early, and bite out as many as three loops of rope from an insecure position. If this is at the second or third clip, the leader can hit the ground as a result of excessive slack in the system. Most gym routes have “clipping holds,” which means the routesetter puts a decent hold on the route to clip from. Use them. Rather than make the clip two moves too early, it’s often easier to clip where you are supposed to, which is often around your waist, or slightly above. Don’t attempt to clip unless you are relaxed and confident you can hold that position for 10 or more seconds.

This article appeared in Rock and Ice issue #251 and has been updated where relevant.

Also Read:

- Weekend Whipper: Be Mindful of the Polished Classics!

- For Safety’s Sake Don’t Do This: Saw Through Someone Else’s Rope

- The Lost Art of the Pre-Wireless Rest Day

The post The Perils of Plastic: Gym Climbing’s Most Common Accidents appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Tufas, food, wine, sunshine, and a hearty culture await those who escape to the Italian island climbing paradise.

The post Hate Winter? Love Sicily Instead. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

My trip to Sicily’s sport-climbing paradise, the fabled limestone of San Vito Lo Capo, started with a massive disappointment—a reminder to not fly too high until you could—nothing major and nothing to do with mother Sicily, since it happened in the Rome airport, but it was aggravating because I had to relearn a universal truth first debated at length by Plato and Aristotle in their 4th century B.C. philosophical Academy. Never expect great things from airport pizza.

~~~~~~~

At the airport I had ordered a pizza margherita, the Toyota Camry of pizzas. Simple, reliable, time-tested. In my mind, I was already in Italy, and, to be fair, I was inside its borders and keen for the best food the Mediterranean country had to offer.

What was put before me two minutes later—yeah, it was microwaved—was a sad sponge, the cheese little squares of bland something-or-other and the sauce … a watery, tomato pasty wash.

Never expect great things from airport pizza. It is a truth as verifiable as the second law of thermodynamics, and yet, smuggled within this truth is another, secondary truth—one that didn’t immediately occur to me, the pizza thing led to it—a truth of climbing, and onsighting in particular: Don’t let your guard down until you clip the chains. Freud’s reality principle meets climbing.

The last day of the trip

A high plateau rimmed by craggy limestone the color of burnt skin, dried orange peels and pan-fried cheddar soared above me. Bristly green grasses held where they could, between, below and above the crags—dig down only a few feet anywhere in this part of Sicily and it’s rock.

Below the expanse that sauntered out of sight to distant crags and sheep trails and carved into the limestone hillside via millions of years of geo-human forces, was an overhanging amphitheater, the Lost World crag.

The Lost World dripped, literally and figuratively. Literally because of a cold rain the night before and the occasional shower that taunted our otherwise stunner of a day. Figuratively because tufas are geological marvels, inverted drip-castles kids make on beaches, minerals in creative posture, things that, I learned, to use successfully you must be awake, not in a yogic sense of being “woke” to the enlightenment of climbing, but three-dimensionally awake. Tufas can grow behind you when you climb. Awake means knowing how to navigate them.

On those tufas in said cave, high drama was unfolding. Cognizant of it being my last route of the trip, I was desperate for a knee bar on an epic 5.12b, pumped out of my gourd from 35 meters of tufa wrangling, easy, yes, but 35 meters of anything ain’t so. And you can bet your shit I wasn’t going to botch it. Remember the secondary pizza lesson?—don’t let your guard down until you clip the chains—I was putting that into practice.

Tu Ri, a local Italian we befriended, had told me the route was 11d, but he also downrated everything with a dismissive shrug of the shoulders in what can only be called the local’s sandbag, the belief that something is easier than it is simply because you’ve done it dozens of times. That’s like believing that everyone should be able to juggle four balls since you’ve been doing it for 10 years.

On an adjacent route Ben Rueck was cruising a super steep 13b, but the last-move crux loomed just above him, a rare crimpy sequence, the gatekeeper, and he was resting, shaking out.

After a mutual “Come on man, you got it,” we both clipped the chains. My forearms were so wrecked I promised myself I’d take a month off when I got home. Which of course I didn’t.

Throughout our day at the Lost World, a scrappy little wildfire had been wreaking havoc on a hillside a few miles distant, flaring up, calming down, raging, abating—a little smoke show. As I lowered, I noticed that the wildfire was out. Curtain closed.

The Toe of the Toe

If Sicily is the toe of the Italian boot, San Vito is at the toe of the toe, peacefully residing on the far end of a small peninsula, a beach town with a crescent-shaped shore on its northern edge, the Zingaro nature reserve to the east, a multi-pitch limestone sentinel, Monte Monaco, at its rear. An abode where middle-class Italians escape and trade their polished leather scarpas (shoes) for flip flops and a lipsmack of Limoncello. Here, you can be sinking your toes in the sand of San Capo’s beach and in 15 seconds by foot be downtown, but not before encountering gelato stalls and plein-air cafes, which, since it was off season when we were there, were boarded up.

As the crow flies, San Vito is 30 miles from Palermo, the big city to the east—yet home to only two rock gyms—but San Vito is an hour and a half drive on one-laners that slice through the heart of every village, town and hillside curiosity. My partners for this sojourn were Ben Rueck, whom you just met, Lena Palms and Jeff Rueppel: friends, crushers, artists.

A pro climber, Ben wears a shaggy, half-mop of brown hair, hails from Grand Junction, Colorado, and is rather serious except when he’s not, then he’s 12 and as giddy as my eight-year-old daughter. He’s a friend of years, a top all-arounder, equally at home on hard Indian-Creek splitters as he is the dura of Céüse, and always climbs as if he is setting a speed record. Typically, he’s clipping the chains on his warm up, something in the 5.12 range, by the time I look at the guidebook. On a given year, he teaches courses at five or six Craggin’ Classics. Ben and Lena just got married. In addition to being a climber—she just sent her first 5.13 this past year—Lena is half Japanese, half Canadian, a former on-air news reporter, and translates Japanese news stories to English, which she would do throughout the trip. Lena is tall and lean with straight dark hair and climbs deliberately and boldly.

A San Fran native, Jeff Rueppel was the man behind the lens. Jeff is forever unshaven and has studied, focused eyes and is always down for an adventure. He has been a Rock and Ice photo-camp instructor for years and has two Masters degrees under his belt, one in Computational Linguistics and another in French Literature, which explains why he is in his element—at least when he is not editing photos, which he is constantly doing—when discoursing about the finer points of Brexit and United States trade policy towards China.

The post Hate Winter? Love Sicily Instead. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Opinion: Climbers through the ages have found value intentionally courting risk. There's a reason for that.

The post Climbing Should be Dangerous appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

After a recent accident on Yosemite’s Snake Dike (5.7 R), in which a young woman got severely hurt, it was proposed—in various forums and threads—that the route should be retrobolted to make it safer. Snake Dike was first climbed in the summer of 1965 by the trio of Jim Bridwell, Eric Beck and Chris Fredericks. It is a classic, and very runout. After the accident, debate ensued. It wasn’t always pretty. Some yelling, name calling, baiting, etc. “Hard men” and their “egos” were to blame for the existence of dangerous routes. The conversations quickly moved into claims concerning the accessibility for all, elitism of a few, ruining the adventure of climbing, and so on.

The debate, in my opinion, was about the essence of climbing.

Climbing’s fraught relationship to the safety-danger couplet, as framed by historical “essence of climbing” conversations, is by no means a new phenomenon. In the 1910s, Austrian climber Paul Pruess was adamant that his style—largely onsight free soloing—was the best and that all others should adhere to it. Royal Robbins scoffed at Warren Harding for poor style on the FA of the Nose. In the 1970s and 1980s, Yosemite soloist John Bachar was called an elitist. Messner believed his anti-siege tactics were the true method for the Greater Ranges. Fair-means alpinists claim their style is the natural evolution of the sport.

Just to be clear, it’s not hard to make climbing safer. Just sink a bolt, or four, in that run-out section, such as on Snake Dike. Replace the rusty piton that Royal Robbins pounded in five decades ago. Add a two-bolt belay on that chossy ledge. Dynamite the widow-making serac on K2. Yes, someone has actually suggested that, but it’s not as if the idea, or the desire, has no precedent in mountaineering. Decisions to make climbing safer are made all the time in climbing. But they are just as often not made, and that’s interesting.

“Should climbing be dangerous?” When I heard people asking this question after the Snake Dike incident, my knee-jerk reaction was, ‘Of course climbing should be dangerous. It’s climbing. Case closed.’ But that’s lazy thinking, and about as good advice as telling someone that if they want to climb harder, “just hold on longer.”

As I thought about it, I learned the question is also, “Why are so many climbers adamant that climbing remains dangerous?” and “Would the essence of climbing change if it was made safer?”

Those are interesting questions.

As the former Editor-in-Chief of Rock and Ice, I wrote the accident report for years. I lost friends. I interviewed grieving mothers and fathers, analyzed gruesome details, and did my best to inhabit the last psychological moments of those who lost their lives, so as to prevent future accidents. In short, the question of climbing’s safety is something I’ve thought a lot about.

On my accounting, the conversation about climbing’s “inherent risk,” has been brought to the fore by four things: (i) a recent spate of injuries and deaths has led to debate about retro-bolting historic routes; (ii) tens of thousands of new climbers have been introduced to the sport via gyms, and those new climbers might not know the deep, historical relationship between climbing and danger; (iii) the very public deaths of a fair amount of our top alpinists; (iv) our pervasive and well documented culture of safety—signs warning people that river rocks are slippery, that you will die if you fall off a cliff—in spite of the general public’s fascination with the risk-porn of The Alpinist and Free Solo. The fact that the public has latched onto climbing as this avant-garde adventure sport pursued by heroes who confront death for breakfast is testament to the idea that this same public experiences and tolerates less and less risk in their daily lives. Also a studied fact.

The question of danger is finally knocking on our collective doorstep, at our crags, mountains and cliffs. And so I’d like to talk about it.

But first, a confession.

My first impressionable climbing experience occurred on the six-pitch Ruper (5.8) in Eldo, outside of Boulder, Co. I was 14 and had been climbing for about a year, but I hadn’t trad climbed at all. It was summer, real slimy and hot. I had forgotten my harness that day but managed to jerryrig one from webbing. A few pitches up, I got off route, and as I stood on a four-inch ledge, frozen, pondering my mortality, the options, what it all meant, my webbing harness fell to my ankles.

I survived the experience, obviously, but it was this very phenomenon—of literally holding my life in my hands—that got me hooked on climbing. Climbing showed me life was optional, and this realization was a gift, one that helped me through some rough teenage years.

Though I’ve been climbing for three decades—I climb ice, mixed, clip bolts, trad climb, boulder, whatever—I do find it illustrative to think every soccer coach in the country would immediately remove a hazard (say a small metal stake sticking out of the ground) from the playing field, whereas I can go climbing 15 minutes from my house and clip a rusty piton that has squatted in an eroding crack, at the crux of a hard route, for 30 years, a piton that wouldn’t hold a proper fall. And we are all OK with that fact. Well, more than OK. Many climbers are adamant that the rusty piton remains where it is. I sure am.

Of course, there’s a big difference between a metal stake in a soccer field and a metal stake on my local M7 WI5. But that difference is somehow bound up in climbing’s raison d’être. The difference illustrates what the climbing game is about. To be clear, what I’m not saying is that we shouldn’t entertain discussions about making climbs safer, or that sport climbing at your local crag should be dangerous. Rather, we should understand at a deep level the entanglement of danger and climbing, so as to help us create better routes. And become better climbers.

The post Climbing Should be Dangerous appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

I thought about it for .0000004 seconds and realized the opportunity was just too good to pass up.

The post The Day I Sandbagged My Boss appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Preamble

Once upon a time I was a jerk, which I’m not often, but I’m not against it, at least in principle. My mother used to say never say never, and apparently I interpreted that to being a jerk as well.

Case in point. It was a summer day in Estes Park, and I was on a beautiful granite multi-pitch route on Lumpy Ridge, one of the most delicious climbing areas in the world. I was at a crossroads, a moral crossroads.

Should I sandbag my boss or not? was the quandary.

Not Hamlet, you say, and you’d be right.

Me and my boss—my actual boss who employed me—were high on Pear Buttress. I, on lead, was running it out properly. But then, as chance would have it, I came across a small bush, if you could even call it that; it was more like a vagabond shrub whose roots clung desperately to the thin ribbons of soil that had washed down the cliff and settled into the cracks.

The branch before me wouldn’t have held a small cat if it was harnessed up and took a whipper. It was the only piece I’d place in a 50-foot stretch, but the route was casual for me, as I’m an excellent climber—60% of the time, I send 100% of the time.

Do I sling the shrub so my boss feels dejected when he gets to it?

My boss was a beginner climber and I knew he’d be gripped on the pitch. He’d see the shrub and, I hoped, know I was toying with him.

I thought about it for .0000004 seconds and realized the opportunity was just too good to pass up. I slung the small shrub with a shoulder sling and continued to run it out to the belay. I got cooked at the belay and waited for him to make his way up. Tap tap. Tap tap. My skin would peel for the following week.

***

In case you don’t know what a sandbag in climbing is, it is when a climber is shut down by a route, either because they have no business being on it, or because it’s harder than what the grade says. Or, in the form of a verb, you can sandbag your friends by secretly working their project, and then, in the opportune time, send it in your tennies.

We all do it.

A sandbag is not defined by an action, but by a psychological result that is inflicted upon the victim. Surprise. Ego deflation. A great laugh. Etc. A sandbag can backfire and you can look like an a-hole, or it can be taken lightly and get a great laugh.

The day on Pear Buttress, I was aiming for the latter.

Some sandbags are immediate. These are good and you can be proud of them. But when you can implement the timebomb sandbag, such that the unsuspecting victim stumbles upon the scene and realizes they have been sandbagged, except no one is around, it is much better, more operatic, in line with drama, postmodern architecture even. Like when the late Michael Reardon left women’s underwear in summit registers during the first sub-24 hour ascent of the Palisade traverse, solo and unsupported.

I was aiming for the timebomb.

***

The beginning of this tale started when my boss, whom my 22-year-old self reported to, wanted me to take him climbing for my last day of work. “Up something fun,” he said. I had just gotten off a summer in Yosemite dirtbagging and really needed the dough and the job, but the stone needs to keep rolling, as they say.

I had done a lot of routes on Lumpy, but not Pear Buttress yet.

Worried I was not—it would be cruiser for me, since I’m an excellent climber, above average in all respects, nearly phenomenal—people say I float, not climb, but I don’t want to brag.

David was in his early 40s, charismatic and archetypically Mid-Western, and stood about five-eight, red hair trimmed military-style, mildly fit in a backyard-pull-ups kind of way. He had two kids at home.

David was only months into buying a carpet cleaning and fire restoration business—to which I was presently employed—and he had the unfortunate luck of inheriting the previous owner’s daughter as the office assistant, a blond with a textbook RBF (resting bitch face), who sat behind the desk doing jack all day, and the daughter’s boyfriend, a skinny know-it-all named Tom, who, with a resting d$%khead face (RDF), and wielding whatever power he thought he had—and trust me, it wasn’t much—routinely arrived late to jobs only to leave, complaining about this or that. Tom was, hands down, the worst employee I have ever come across, in any job, period.

David would fire both of them within a few months. As he should have.

I had let David know months ahead of time that I had to quit. I worked hard for him, so he said he wanted to go climbing on my last day. Even better, I’d be on the clock in my pseudo-guiding adventure, or whatever you call it, so of course I agreed to take him out for a romp. David worked hard and didn’t get out much.

***

I opted for Pear Buttress, a brilliant little route, five pitches, 5.8, bomber granite, cracks, face climbing, flakes.

If you haven’t been to Lumpy Ridge, go there. The views behind you are expansive in a David Caspar Friedrich type of way, a broad valley in which storms roll through, a place that is “meta” in the meta sense of the world, African savanna’ish, the mythical Longs Peak nearby, the golden grass like a canvas painted by the wind when the storms approach.

David would be gripped on Pear Buttress, which was the point. The guy wanted an adventure and who was I to let him down.

Some great opening pitches of flakes and cracks got us into rhythm. Naturally, I had left the stoppers in the car, along with my extra chalk and a few crucial cams. Nothing to worry about though. Meh.

David took his time following, which provided me ample time to get sunburnt and work on a severe case of dehydration. At each belay he looked nervous and kept saying how thirsty he was, which, given the sweat pouring off his face, wasn’t untrue. Also, during the first few pitches, he was hooting and hollering, the grand ol’ time it was. He was proud of himself, as he should have been. I was proud of him too. He wasn’t my boss at that moment, just two guys having an excellent time, not that he had ever really acted as “the boss.”

Throughout the day, he’d pat me on the back, say how thankful he was, and check my anchor four times before leaning back. Remember, I’m excellent, very good, the best type of climber. I’m fantastic. But I had never told him as much, out of humility.

Up until this point, David had been nothing but a first-class guy, generous when he didn’t need to be; took the crew out for steak dinners and didn’t squabble when we ordered the 32-ounce New York Strip and three margaritas and then drove the company vans back to the shop. But, then again, part of our job included cleaning up the guts and blood of dead bodies and what have you from carpets and walls and mattresses, and David was making a killing off the insurance money, so I guess a few steaks and a buzz was in order.

As we neared the top—I don’t remember which pitch exactly—I got to that shrub and my moral crossroads.

To reiterate, I slung the bush with a smirk and ran it out to the belay.

***

Twenty minutes later he came up in a huff, sweating profusely.

“You mother f%#ker,” he said with a cotton mouth, shaking his head, then bursting out into laughter. “Here I am gripped and you f&%king sling some little goddam shrub.”

He looked dejected and humored; exhausted and peeved and overjoyed.

On the inside, I felt excellent. Extravagant. My ego, which every self-help guru in history advises you to not puff up, had indeed ballooned and it felt great, not because I had put David in his place, but because I had given him a good laugh. Timebomb achieved.

Afterwards, we drove into town and ended up at a Mexican joint that had a dirt parking lot suitable for a Boeing 747. I had the chicken fajitas, as I am always inclined, and slurped down two margarites instantly: rocks and salt.

I had a buzz in five minutes. The salt stung my cracked lips, in a bad way.

David was still laughing about the shrub and asked me if I’d consider not quitting. I told him no, “I had to go see about a girl,” which is, funny enough, what Will, of Goodwill Hunting, said to his therapist (Robin Williams) after turning down a job and splitting town. That girl is now my wife.

I can’t be sure of it, but something tells me David is still telling that story today.

***

Francis Sanzaro is infrequently on Insta, FB and Twitter. Originally published in Rock and Ice, in 2020.

Think You Know Your Climbing Terms? Take This Quiz and Find Out.

Weekend Whipper: Bolt Hanger Falls Off—With the Climber Attached

The post The Day I Sandbagged My Boss appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Just who climbs a route first is nuanced, and with big money at stake the lines between success and failure have gotten fuzzier.

The post Who Did It First? Style, Grades and Dispute in First Ascents appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Climbing grades don’t matter. You, me, us—we should just climb because it feels right or we’re trying to impress a girl…or a guy. Whatever comes first. Don’t judge. An unnatural focus on grades or definitions is to miss the whole point of climbing—freedom, travel, experience, intensity, overcoming boundaries. We all hate the grade police. Just get up the thing, right?

Not really. That’s half of the story. We, the pluralis majestatis, were in the Olympics, and companies far and wide took notice, with marketing budgets and opportunities for sponsorship following suit. With gobs of money pouring into our sport (Coke is sponsoring athletes now) comes the necessity for athletes to promote those products. In order for those athletes to get attention, they climb new and exciting things, FAs, FFAs, routes in exotic locations, light and fast ascents, naked ascents, and so on. Getting millions of eyeballs to read about climber X traveling around the world to send 5.7s is impossible; of course, that’s rad—no, really, climbing 5.7 is awesome—but it doesn’t make headlines. All good and fine thus far, and we shouldn’t judge.

And yet news abounds daily about claims of a certain type of ascent. A typical email—”Me and my team just climbed “x” in “x” style,” and so a claim is made. More often than you would think, the claim is inaccurate.

Climbs are tricks in a way, and since tricks can be performed with style, it’s only natural that climbing achievements are judged on improvements in style. In this context, style is not referring to how someone moves, but the way in which they chose to climb something. It’s a “game climbers play,” to cite Lito Tejada-Flores, and someone is always upping the ante. Alex Honnold’s free solo of Freerider on El Cap was one such improvement in style. Climbing doesn’t have objective measurements like line tape or a stop watch. We do have a rating system, but all climbers know body type is a huge factor. “Take!! I’m just too short for this move. It’s like 5.14 for me,” said everyone at some point.

Here’s a for instance: say you go out and climb the South Face of the Petit Grepon, in Estes Park, an eight pitch 5.8 on beautiful alpine granite, totally classic, and often crowded. A friend and I climbed the South Face a few years ago and we swapped pitches, as is normal on a typical trad outing. Yea, I’ve done that route, even though I didn’t lead every pitch. It was well below my ability on a gear route, so I didn’t feel the necessity of telling everyone, in conversation or whatever, that I had led half the pitches. No bounds nor speed record nor any record of any sort was broken that day, and it was perhaps all the better for that reason.

However, on ascents where performance levels are raised, collectively or individually, and they are reported upon, the stakes become higher, and it does matter. Climbing a 20-pitch 5.13 gear route and leading every pitch is exponentially harder than doing it with a partner and swapping leads.

In particular, magazines see a lot of incorrect reporting on the nuances between team ascents, free ascents, and individual ascents, among others. It likely comes from an over-eagerness to do something “first,” with a little bit of market pressure thrown in for good measure. Regardless, here’s some provisional thoughts, nothing in stone, and largely applicable to big wall rock climbing where the stakes are high. Let’s start with the simple stuff, then get more complex.

Individual ascents should be claimed when the climber leads all pitches, without falling.

Team ascents send the rig, but “swap leads.” This is the most common form of hard free ascents and first free ascents. In 2015, Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson sent the Dawn Wall as a team ascent and free ascent, since they swapped pitches; however, each sent the crux pitches. In 2016, Adam Ondra climbed every pitch himself, which amounts to the first individual ascent and second free ascent. Could Tommy and Kevin have each made the first and second individual ascents?—yes, of course. They just didn’t. Jorgensen wrote of Ondra’s ascent: “For Tommy and I, the question was whether it was even possible. We left lots of room to improve the style and Adam did just that!” Ondra’s ascent was an improvement in style, and arguably, in difficulty; however, having the vision and dedication to see the route, clean it and work it over years is more difficult in my estimation.

What about first female ascents (FFAs) in a mixed team? Can an FFA be claimed in a team ascent?

Single push ascents, as opposed to multi-day, refer to a climb being done in a single push, either by team or an individual, regardless if they have rehearsed it before. For instance, if you start climbing and then top out, without hitting the dirt to party on a rest day, then it’s a single push ascent. Lynn Hill was aware of this, and so, after her 1993, four-day team ascent of the Nose, she returned the next year to plant her flag with a single push (23 hours), leading every pitch herself—the first individual free ascent of the Nose. She wanted to do it in a better style. Ante up gents—“It goes, boys,” said Hill.

If you didn’t rehearse the route, then it’s a ground-up single push ascent. Assuming you didn’t onsight every pitch, did you pull gear on rappel?…since to properly claim a single-pitch trad send you can’t have pre-placed gear. The same should apply for big walls, right? It gets complicated. Did you stash food and gear up high? Did you have big-wall porters? Does that change anything?

Ok, down the rabbit hole some more. Say you have a 10-pitch project, and, over the course of the last five years, you’ve led every pitch. Maybe the first year you led pitches, 1-3, 7 and 9, and then on year five you led 4, 5, 6, 8 and 10. Can you claim the first free individual ascent?

Back to the Nose on El Cap for context…in 1998 Scott Burke nearly freed the Nose, an attempt that took 12 days, and he top-roped the Great Roof pitch because of impending storms. Tommy and Beth made a team ascent in 2005, and then Tommy made an individual free ascent in the same year, leading every pitch himself, in a single push, in 12 hours. Technically, in 2005, that means the only people to have sent the Nose individually were Lynn and Tommy.

I could easily keep going with distinctions—such as variation pitches—or take up the idea that naked, chalkless free soloing is the logical culmination of Royal Robbin’s “clean climbing” revolution, but I won’t. People ask how Honnold can be outdone—well there it is. Chalk and rubber are still quasi-technologies.

Style matters, and style informs difficulty, and we need to be clear about who did what and how. Since style is progressive, honesty is paramount.

For the majority of climbers, these distinctions don’t matter, but for those of us reporting on them, it does. As climbs are touted with increasing pressure from all parties to do something unique and singular, gone are the Warren Harding days of getting up the thing…unfortunately.

The post Who Did It First? Style, Grades and Dispute in First Ascents appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Specters, “third men,” and otherworldly encounters... Are they trying to tell us something?

The post The Mountains are Graveyards. Some Climbers See Ghosts. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

I.

Who to believe? The mountain or the ghost.

Both saved our lives, Almost.

II.

As she hunkered down at 6,800 meters for her third open bivy on the second winter ascent of Nanga Parbat, French mountaineer Elisabeth Revol met an old wrinkled lady. The lady offered her warm tea, but only if “you give me your shoes.”

Revol did as requested, and woke up the next morning with a frozen foot. “Fuck, what happened,” she thought to herself.

III.

In 1985, Jeff Lowe arrived in the Everest region with Earl Wiggins to attempt a new route on Pumori (23,400 feet) and the South East Spur of Nuptse East (26,000 feet). Upon arriving at base camp, Wiggins fell sick.

Lowe, impatient and eager, headed out solo on Pumori. As he made his way up, Lowe realized he had a friend with him. A ghost. The ghost gave him beta and guided him to the summit. Lowe then fell sick on the mountain, emptying his stomach of all he had and remaining unable to hold food down. With persistence and sound advice, the ghost got him to base camp. Lowe would later recount the story not with an “I,” but with a “we.”

Once back in base camp, Lowe learned that Wiggins had recovered faster than expected, and had started up to do a new route on the mountain he just came from. Exhausted, Lowe turned in for the night, but kept hearing a voice crying “help.” Lowe realized that Wiggins, over a mile above him on Pumori and far out of range to be heard, must be in trouble. The ghost was relaying a message. Lowe roused an extremely reluctant base camp team in the middle of the night—they figured he was just delirious—and went up to look for Wiggins. In what can only be of the mystical variety, Lowe spotted a glow and found Wiggins face down in a frothing pool of vomit.

“What took you so long?” quipped Wiggins.

IV.

Ghosts, spirits and souls—the latter our true daily ghosts—all have chosen the mountains as their proscenium, where they play with us. Put on a show. It’s called the third-man factor, or third-man syndrome. Sometimes the ghosts are mischievous, as with Revol, sometimes comforting, as with Lowe. It just depends.

In 2014, a Swiss researcher by the name of Olaf Blanke was reportedly able to recreate the third-man factor. By manipulating bodily sensation via robotic arms and temporal delays, in essence playing tricks on his participants, Blanke said he was able to generate strong feelings of a “third presence” in his subjects. But how would Blanke’s theory explain away Lowe’s story on Pumori? Or the hundreds of other stories? It can’t.

V.

In May of 1996, Tsewang Paljor, an Indian mountaineer and border-police agent, was high in the death zone on Everest. A storm was brewing and the mountain gods had just turned off the lights. He was exhausted, stumbling, alone.

Paljor, a young-looking 28, had just tagged the summit with two others and was hours away from making history as part of the first Indian team—an Indo-Tibetan Border Police expedition—to summit Everest from the north.

In family pictures, Paljor has soft, proud eyes, not an athletic frame but not unathletic either, a black rubbly mustache and black hair, the kind you can’t really comb, just sticks up. In another photo, in official police garb, he has beady black eyes, is clean shaven with tamed hair that parts right and his mustache has filled out. He looks older. According to friends, Paljor liked to sing in his free time.

Earlier that morning, the 10th of May, Paljor and his teammates Tsewang Smanla and Dorje Morup overslept. They would start out at 8 a.m. from Camp VI, four and a half hours after their intended start. Given the late start, they agreed to fix ropes that day, rather than gun it for the summit. It was the reasonable decision. Harbhajan Singh, the expedition leader, was good with that plan. He was on the mountain with them, but he couldn’t keep up, so they went ahead.

By 2:30 p.m., Singh wanted them on their way down, and so, around that time he gave the order to return. But much to his surprise, at 3 p.m. the team wasn’t heading down. They were heading up, for the summit. Unable to catch up, and sensing the veil of mortality being drawn on himself, Singh headed for the tent in Camp 4.

VI.

At 5:35, Singh got a call on his radio. All three were on the summit. He was relieved, but, and no one knew it yet, the infamous 1996 blizzard—the same one that made Krakauer’s Into Thin Air and stole the lives of eight climbers—had wrapped itself around the mountain.

Exhausted, unable to go any farther, Paljor found a small cave of black rock, a bit of respite from the biting cold and the blinding snow. Likely, he thought he’d just rest a bit, gather some strength, and head out when the storm cleared. He laid down on his left side.

The post The Mountains are Graveyards. Some Climbers See Ghosts. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

As the gear-review manager, I own over 50 pairs of climbing shoes. And that’s lowballing. I’m trying on new shoes almost every week. My feet hate me. First World problem? You betcha. Forget all you know about how to find, and fit, your next climbing shoe. Most of the information out there is junk. This … Continued

The post How to Find and Fit Your Next Climbing Shoe appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

As the gear-review manager, I own over 50 pairs of climbing shoes. And that’s lowballing. I’m trying on new shoes almost every week. My feet hate me. First World problem? You betcha.

Forget all you know about how to find, and fit, your next climbing shoe. Most of the information out there is junk. This is your first and last guide.

APPETIZER

Primary Laws of Shoes

1. Comfort is not king.

Fitting your climbing shoes for comfort is like buying a car because you like the driver’s seat. What I’m not saying is that climbing shoes should be uncomfortable, only that buying for comfort first isn’t wise.

A few exceptions exist, however, where comfort should be top priority: for kids, because their feet are still developing and they just need to have fun; for absolute newbies who don’t need the distraction of less-than- comfortable shoes. If either of these situations sounds familiar, get the comfiest pair of kicks imaginable, let ’er rip, and stop reading. For the rest, keep on.

2. Performance mostly matters.

The marketing of certain shoes as for “performance” is a lie. Performance is relative. A 5.8 climber needs a shoe that performs for their ability just as a 5.15 crusher does. That is what matters. Performance means you are using a shoe for what it was made for.

3. Have two pairs, at least.

I bring three to the crag, or gym, and so does almost everyone who takes climbing seriously. First, ask yourself what type of climbing are you doing? Are you mainly bouldering, leading or toproping? Whichever one will determine your shoe. There’s no such thing as an all-arounder, really. Thinking one shoe can do it all is like trying to shoot your best round of golf with only a five iron.

First, you want a pair to warm up in, and a pair when things get serious. Why? Save the wear and tear on your sending shoe, which can cost upwards of $200, and grind down the rubber on a cheaper pair.

4. Foot shapes are different.

I know some climbers whose feet only fit in a La Sportiva shoe. Others only use Scarpa. Try on loads of brands and whatever shoe you end up getting, there should be no extra space in the toe box, heel cup or arch. If there is, keep shopping.

MAIN COURSE

Now to the Shoes

Flat Shoes

Flat shoes, as in where your feet are absolutely flat and no crunched toes, pretty much like your everyday shoes. The bottom of these shoes looks flat. In general, flat shoes are excellent for slabs and the vertical wall, and kids. Flat shoes can be soft to stiff. Stiff are for harder vertical routes or hard slabs, such as when you need to stand on quarter-inch edges and such. Stiffness helps you stand on smaller holds with more efficiency, putting the burden on your calves. These shoes are not ideal for bouldering or anything steep. Flat shoes tend to be the most comfortable.

Fitting for flat shoes: “Yum, these feel good” to “Ahh, perfect.” Fit these shoes snug, your toes right up to the tips, but not crunched. If it’s a tad tight, ask yourself if you can wear them for 15 minutes. If you can, get them. Snug yields better performance than loose. Bear in mind that rock shoes stretch, usually half a size.

A flat shoe with a relaxed rand lets your toes lie naturally without being squeezed. These are great entry-level footwear, and because they are comfortable, are suitable for all-day wear.

Downturned Shoes

Downturned shoes are designed for steep to overhanging climbing and bouldering. A downturned shoe arcs like a bird beak.

Downturned shoes are usually mid to extremely soft for sensitivity. Unless you predominantly climb on vertical terrain, you want a pair of downturned shoes in your arsenal. There are subcategories:

Mildly downturned: A mid to mildly downturned shoe will get you up techy slabs, can perform on vertical terrain, can still get into pockets, and is great for the lead cave and bouldering.

Medium down-turned shoes strike a balance between comfort and performance. If there is an all-arounder, this is it.

Extremely downturned: A rule of thumb: the more downturned a shoe, the more it is meant for overhanging climbing, the reason being it lets you grab and pull in with your toes (for a caveat, see “Asymmetrical shoes”). There’s nothing sadder than seeing someone on a steep route

with a flat shoe. As Yoda said, No favors do they make for themselves. For steep bouldering or steep sport routes—over 45 degrees—get an extremely downturned shoe.

Fitting for downturned shoes: “Not bad” to “Uuugh” to “Damn, that hurts.” Again, they’ll stretch a bit, about a half size. You only need to wear them for one to five minutes at a time. If you size these shoes too big, it’s like tying up a horse’s leg before the race. Very snug to tight is the rule. During fitting, your toes should be crunched and angled downward—this allows you to pull on steeper terrain, and the asymmetry in these aggressive shoes will allow your big toe to engage.

Aggressively downturned shoes with a slingshot heel rand perform better as the wall gets steeper. This type of shoe compresses your foot and puts the power in your toes.

A Note on Rands:

The rand is the strip of rubber running around the shoe upper. Most downturned shoes have a tensioned “sling- shot” heel rand that keeps your heel locked in and drives your toes to the end of the shoe. There are other variations of an active rand, such as arch rands. Some flat shoes will have an active heel rand, but the majority are relaxed.

Stiff Shoes

Stiff shoes—as in, the bottom of the shoe feels like a board—refers not to shape but feel. These shoes are for outdoor climbing, trad climbing and slabs or vertical routes with a lot of edges.

A stiff shoe has a rigid midsole, a midbed stiffener that supports your foot (especially when torqued in cracks), so you don’t have to have strong feet to get the best performance out of them. Stiff shoes can be flat or downturned, but usually they are flat’ish.

Fitting for stiff shoes: same as for flat shoes.

Asymmetrical Shoes

This refers to the shape of the shoe. Imagine a twisted banana. The more the tip of the shoe bends away from the center line, the more asymmetrical the shoe. Flat shoes are typically more symmetrical, but never perfectly so. Most asymmetrical shoes are downturned. The purpose of the asymmetry is to keep your toes in a crimp position, which helps with digging into holds on steep routes and, with some models, help keep you on small holds on vertical terrain with greater precision, thanks to your big toe doing a lot of the work.

Fitting for asymmetrical shoes: Same as for downturned shoes.

The post How to Find and Fit Your Next Climbing Shoe appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

For the past year, I’ve used the Blue Ice Reach 8L for ice, rock, and varying mountain adventures. In the genre of small, lightweight, performance, on-route packs, it’s by far my favorite. I’ve taken the 12.5-ounce pack up Bridalveil Falls, a three-pitch WI 5+ in Telluride, Colorado, and then, in spring, up the Scenic Cruise … Continued

The post Field Tested: Blue Ice Reach 8L appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

For the past year, I’ve used the Blue Ice Reach 8L for ice, rock, and varying mountain adventures. In the genre of small, lightweight, performance, on-route packs, it’s by far my favorite. I’ve taken the 12.5-ounce pack up Bridalveil Falls, a three-pitch WI 5+ in Telluride, Colorado, and then, in spring, up the Scenic Cruise (5.10; 9 pitches) in the Black Canyon of the Gunnison. In between, the Reach 8L has been on ski-mo trips and up Fourteeners. I also just took it on a big enduro day—some running and some hiking—in the Elk Mountains, near where I live. Why do I mention all this? On these trips, I only take the good stuff. The Reach 8L is an excellent pack, thoughtfully designed, and relevant for just about any mountainista.

What I Liked

Here’s what I like about the Reach 8L: First, it carries high on your back, which means a harness doesn’t mess with it. When you’re wearing it, it has an ultra-running-pack feel—i.e., it’s anatomically designed to aid and enable efficient movement. With a slight taper from top to bottom, this pack is meant for moving. Could you run 20 mountain miles in it? Yep.

Second, it carries like a dream. The shoulder straps are wide, snug, and flat, which means they feel more secure on your chest. It feels like you’re wearing the Reach 8L, rather than carrying it. I was able to lead demanding 5.10+ trad with a double rack with the pack on. One innovative design is that the main shoulder straps connect to pack’s base on its outside (farthest from your body), not the part of the pack nearest your lower back. That means that any are held in place firmly, with tension, as opposed to more traditional pack design. As a result, when the pack is empty, it lies even closer to your skin. This might sound like a trivial point, but it isn’t. The strap design is intended to get rid of the bobble effect you get with so many backpacks

Third, the front strap pockets (which also zip) can hold a phone, soft bottle, or a snack, all of which you can access very easily while on a long pitch. That the front pockets zip is great for the phone. The pack does have small gear loops on the side, but I haven’t used them yet.

Fourth, the Reach 8L has ample straps for attaching just about anything, for a variety of sports, though I do wish the side rope-carry straps were not the kind you cinch down, but rather snapped: The reason being you have to shove your rope through the straps, rather than just loop your rope around the top and snap it on.

A Few Bells and Whistles

The inside has a zip pocket for valuables and a hydration pouch, and the optional helmet carry is another great design. As for durability and material, it is what you expect from Chamonix-based Blue Ice, a high-end alpine brand. I have run mine through the wringer for months now, and it’s showing no signs of letting up.

The post Field Tested: Blue Ice Reach 8L appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Looking for a light, all-purpose helmet for ice, rock, and alpine? This model is available with Recco technology and in hard and soft shells.

The post Grivel Stealth Helmet, A 7-Ounce All-Arounder appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

The Grivel Stealth is a light, all-purpose helmet for ice, rock, and alpine. One thing I’ve liked is its lack of breakable plastic on the inner casing—those fragile little slivers. The majority of the Stealth’s inside is webbing, and there are only two bits of plastic, where webbing is held together; it would be hard to break those. Adjusting is easy via a single pull tab on the back. The shell is polycarbonate, which instills more confidence, at least for me, than a pure-foam helmet. Despite the feel of a hard shell, the Stealth is classified as a soft shell. The back of the bucket drops low, just under the occipital bun, and all climbers who sometimes forget to put their leg outside the rope can thank Grivel for that. At seven ounces, it weighs as much as an adult hamster, and as for the bright-yellow color option, hint: It’s best for getting rescued. You can also get the hardshell, which drops the price $20, or Recco reflective technology, which ups the price $10.

The post Grivel Stealth Helmet, A 7-Ounce All-Arounder appeared first on Climbing.

]]>