A profile of the 20-year-old Canadian who sent Free Rider in 18 hours.

The post Ethan Morf, the Youngest Person to Free El Cap in a Day, Is Just Getting Started appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

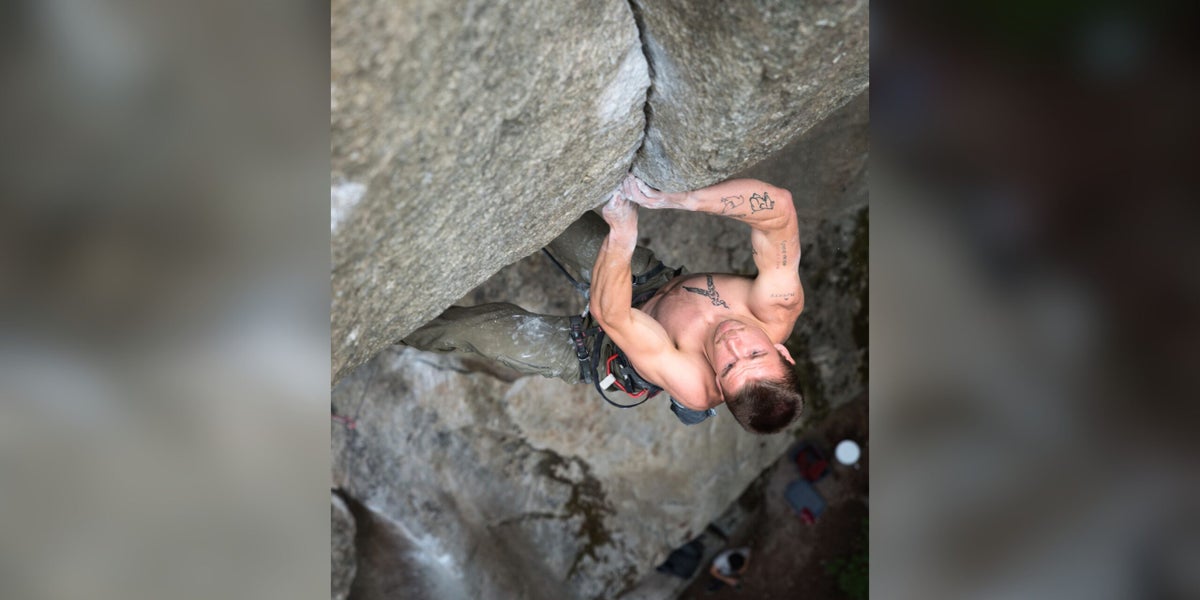

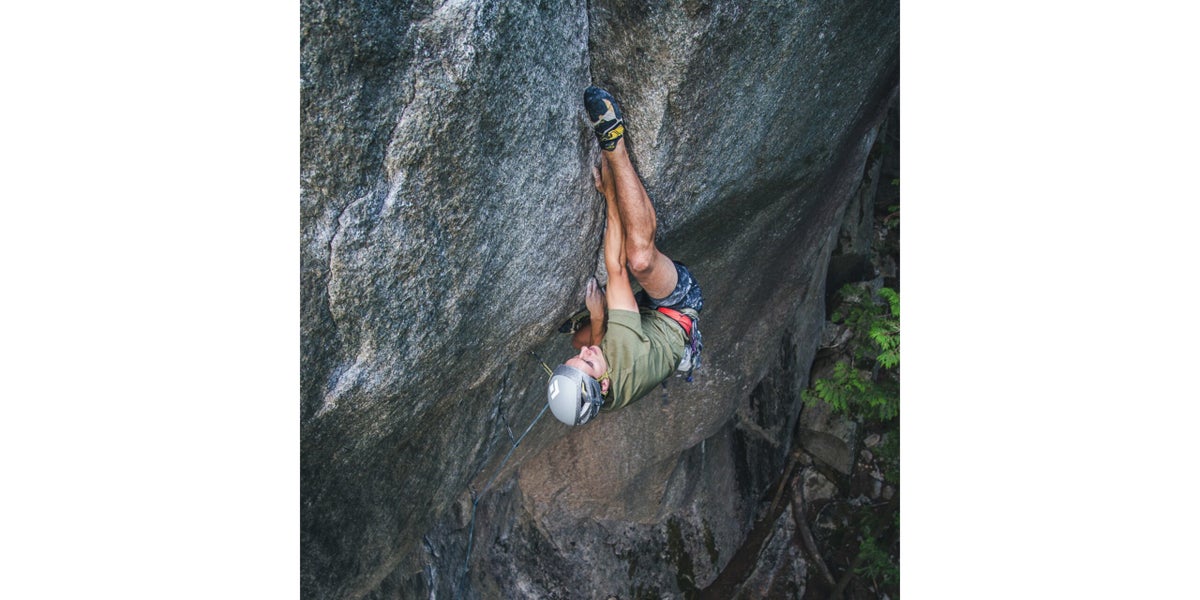

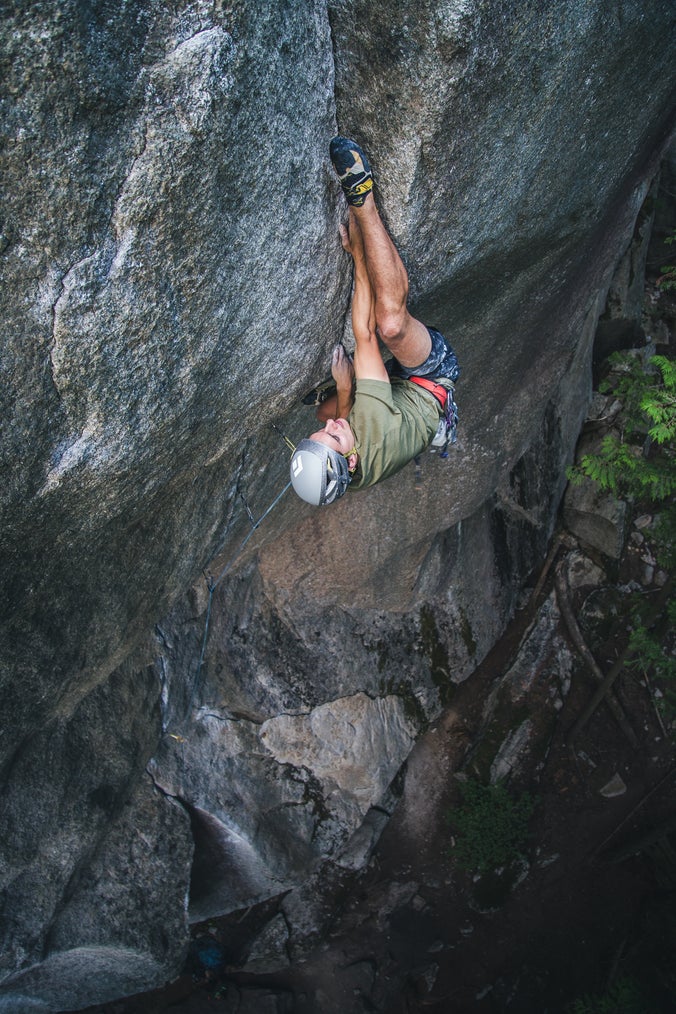

Ethan Morf had been climbing for fourteen hours straight before he took his first fall of the day. He slipped off the Roundtable Traverse (5.12a/b), 23 pitches up El Capitan’s Free Rider (VI 5.13a; 29 pitches) with all of the route’s cruxes under his belt. It was (kind of) in the bag if he could get through this last bit of 5.12. He ticked some footholds, rehearsed his sequence one more time in his head, and lowered to the hanging belay. His friend, Xavier Larivière, was waiting for him. “He couldn’t really hold on anymore,” Larivière said. Morf wasn’t sure if he could pull it off either. Up until this point it had been Larivière’s job to go fast and keep the pace, but now he reminded the 20-year-old Morf to slow down. “We hadn’t really rested since we started, so I encouraged him to just sit in his harness, drink some water, and relax for a bit.” Morf, exhausted, laid across Larivière’s lap, and fell asleep at the hanging belay. He woke up 15 minutes later and fired the pitch. Morf called Free Rider’s five remaining pitches “the fight of my fucking life.”

***

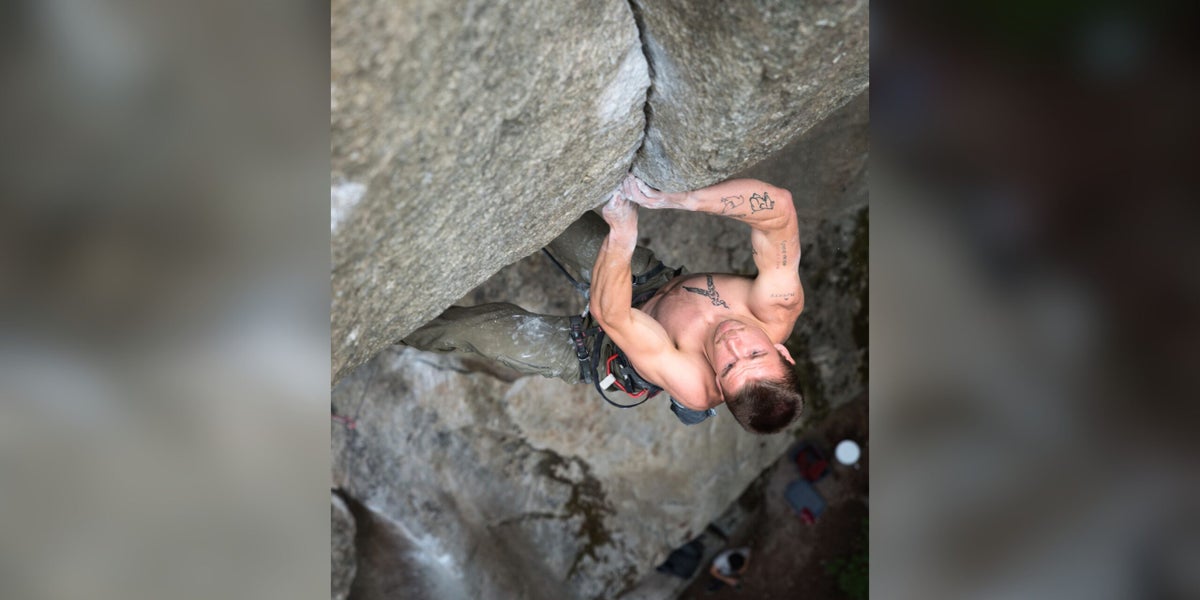

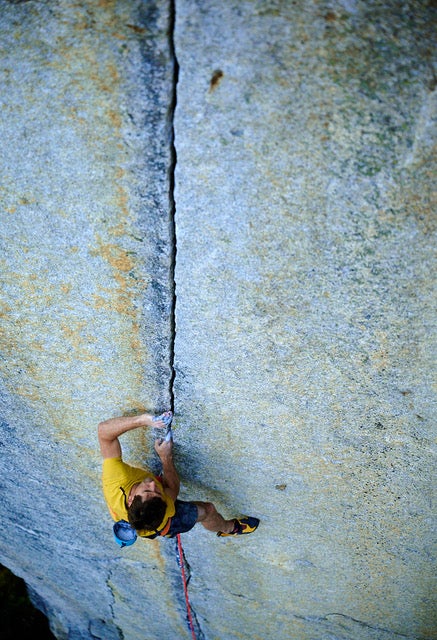

Four years ago, Morf was a junior in high school in Summerland, British Columbia. On the weekends, he and his friends would get a ride from parents (and then later drive themselves) to the nearby Skaha Bluffs, a world-class collection of technical gneiss. Armed with a set of quickdraws, a rope, an ATC, YouTube, and high-speed data, they would learn how to rock climb. “I remember vividly doing my first lead, getting to the anchor, going in direct—being turbo-gripped—and watching a YouTube video on my phone explaining how to clean a sport route,” Morf explained, laughing heartily over the phone. Arlo Kast went to high school with Morf, though they didn’t become friends until they ran into each other at the climbing gym, and then went to Skaha together with YouTube as their guide. “Ethan would YouTube ‘how to sport climb’ and then the next day he’d teach me what he learned,” Kast confirmed, shaking his head. They climbed as many of the best 5.10s in the park they could. Morf even did his first project, a 5.11c sport route called Rock Soft. “It really changed my perspective on things,” Morf recalled, “Like, ’Oh, you can just do hard things if you keep trying them.’”

Morf was in love with climbing, but he had still had one more year of high school. “It was sort of classic,” Morf remembered, “Like, this little boy found climbing and climbing became his whole personality.” He spent his senior year Moonboarding and watching climbing films, steeping himself in the classics: Dodo’s Delight, Rampage, First Ascent. For most Canadian climbers, all roads eventually lead to Squamish. Morf was no exception. He saw Didier Berthod trying the Cobra Crack (5.14b) in First Ascent and he knew where he was going to spend the summer. Right after graduation, Morf beelined to Squamish in a black Ford Econoline he built out with his dad. He was 17.

Amidst thick cedars and Douglas firs, there’s a campground at the southern toe of the Stawamus Chief. Because paying campers need somewhere to park their car before pitching their tent underneath the idyllic coastal rainforest, there’s a less-idyllic gravel parking lot. And because climbers are, well, climbers, they inhabit that gravel parking lot for months on end, occasionally paying their campground fee to try to keep the heat off. Lucky climbers get an actual campsite for a bit, but eventually the rangers will evict you after a few weeks. If all climbing roads in Canada lead to Squamish, a lot of them spit you out in the gravel lot. It’s awesome. It’s dusty. Vans are packed in like sardines. Friends, summer flings, exes, pros; they are all in the gravel lot. That’s where I was living when Morf rocked up in the black van he built out with his dad.

The gravel lot is a carousel of characters, and that summer was no different. One of those characters was “Rooftop Will” Larivière (no relation to Xavier) who was working as a park operator and living out of a black Honda CRV with a caged roof he liked to cook from. “He was this little kid with pimples, psyched on everything and everyone,” Will recalled. “He came in as this super-new-to-the-sport person wanting to know where all the best 5.9s and 5.10as were.” Morf was in Squamish for a month on that first trip. “Everyone took me under their wing. It was so cool,” Morf said. By all accounts it sounded like a classic, formative summer. Morf learned how to trad climb (mostly from folks in the gravel lot, and less from YouTube), promptly and harmlessly decked (but who amongst us hasn’t?), and made a lot of friends. Dreamy. At the end of it all, he went to the Bugaboos and climbed the unbelievably splitter Sunshine Crack (5.11-; 300m) which, as you might imagine, blew his mind) and then headed home to Summerland, not yet realizing many Canadian rock climbers chase conditions south like their gander compatriots.

Three years later—yes, only three years, that first summer was way back in 2022—Morf is a staple in the Squamish climbing community. The last few summers he worked as a park operator, recruited in the gravel lot by Will and their boss Connor Runge, another climber who climbed, if you will, the corporate ladder of the campground. In turn, Morf recruited Kast, his old friend from Summerland. “Ethan was perfect for working at the campground,” Will beamed. “Everyone loved him. It was cool to show him the ways—the ways of how to do as little as possible. He picked up on it quite fast, he was really good at fucking around.” Indeed, when they weren’t tending to the park’s bathrooms and garbages, and they’d finished up treating the work golf cart like a rally car, and they’d brushed all their friend’s bouldering projects and gotten their lap of Rocket Pig in, they were hanging out. Morf may have been a listless employee, but he is a very intentional human. I remember feeling like he was genuinely invested in whatever I was doing each time I’d catch up with him in the gravel lot. Multiple people I spoke with for this profile expressed a similar feeling—that Morf has such a strong community around him not out of chance, but because he got out what he put in. Will echoed: “He’s super engaged when he’s with people and it shows in how people respect him. It was cool to work with him and see him grow, and see it through his climbing.”

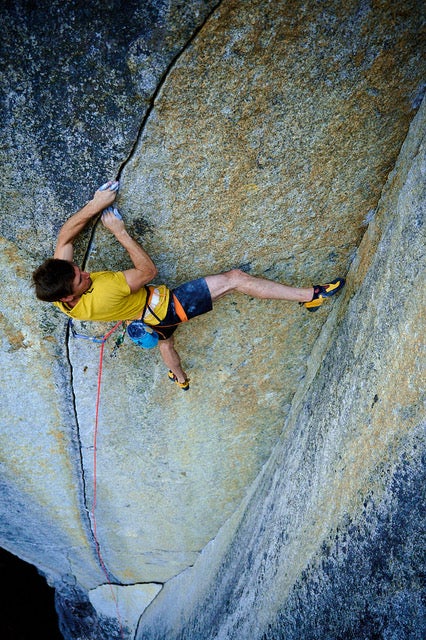

Indeed, his climbing has evolved. Working at the campground in the summers allowed Morf to travel in the winter. He did hit a bump, tearing his labrum on Yosemite’s Separate Reality in autumn of 2023. Morf spent the winter again in Summerland, healing and diligently rehabbing, ensuring he was ready for spring. Since then, he’s been on nothing short of a rampage, climbing his first 5.13c, 5.13d, and 5.14a, all single-pitch sport climbs, and has climbed a number of impressive trad climbs including Indian Creek’s Air Swedin (5.13 R). Up high, in no particular order, he’s climbed The Free Grand (5.13a; 300m) in Squamish, the third ascent of Manchu Wok (5.12d; 485m) on the remote Chinese Puzzle Wall, Zion’s iconic Moonlight Buttress (5.12+; 360m), El Gavilan (5.13a; 270m) and Los Naguales (5.13b; 270m), both on La Popa, a steep limestone wall in Northern Mexico. In the fall of 2024, Morf freeclimbed Free Rider over several days, ground up, with Kast. Morf brought a camera along for most of these ascents and publishes his videos on YouTube. There’s one shot where the boys are sitting on top of El Capitan after their ascent. Kast says, “If I could do it again, I’d do it again with Ethan, he’s the best partner.” Morf smiles at this, looks at the camera, and says “Arlo is the best fucking partner ever.” The shot changes to a sunset. They look like the climbing videos he watched with his dad back in Summerland. After Morf shot photo and video of Victoria Kohner-Flanagan on Squamish’s Tainted Love (5.13d R), she said: “For as long as I’ve known Ethan, he’s intentionally taken steps to do the things he wants to do. I think a lot of people want to do those things, but very few actually make decisions to do them. With the videos and photos, I think he’s been inspired by the last generation, and I think now he wants to add to the climbing literature of psych and inspire people in his own way.”

***

Morf’s in-a-day ascent of Free Rider sounded just as wholesome as him and Kast hugging in the sunset, but maybe a little more heinous. Things had gone according to plan up until that twenty-third pitch: no falls, thanks to the meticulous preparation Morf had undertaken the last few weeks. He did the crux karate-kick first try. Big-wall legend Mark Hudon reportedly called him a stud as he raged up the Enduro Corners (5.12+). But now, he was exhausted. After his nap in Xavier’s lap and subsequent firing of The Roundtable Traverse, their progress slowed to a crawl. Morf split up the Scotty Burke offwidth into two pitches, belaying at a bolt and a stance. Sheer will got him through the pitch; his exhausted body refused to comply with the beta he’d chosen to avoid offwidthing the pitch, so he squeezed in there and wiggled like a young man possessed with a dream. Still, though, it wasn’t over. The second last pitch, a 5.10d roof, took him multiple tries. But he did it. He topped out, all free, in a day. The fight of his life, as he put it.

View this post on Instagram

“It was the most inspiring thing in climbing I’ve ever seen,” Xavier said. Morf is the youngest person to free climb El Cap in a day, upping the ante from his friend Sam Stroh by a few months. “I’m so proud of him. I think it was the first time where Ethan got to tap into some Yosemite spirit climbing,” Stroh told me, which I can only assume describes the sensation of trying to offwidth while your whole body is cramping and you are trying to stay awake. Morf’s thoughts on being the youngest? “That’s only because Connor Herson was too busy freeing the Nose to do it. It’s this cool bonus, and a cool fact, and I feel incredibly privileged, but someone else [younger] will come along.”

When I originally set out to write this story, I thought it would be about this next-generation talent and his rapid rise to rock climbing stardom—how did he do it, and how did he do it so fast? To the podcasters out there, I apologize, as I don’t think Morf’s story has a get-strong-quick scheme. One adage, perhaps, is that multiple people close to him told me that he is “the most focused person” they’ve ever met. Sometimes, with that amount of focus comes some element of coldness—jettisoning relationships in the name of a craft, especially for someone in their early twenties. With Morf, that doesn’t seem to be the case. Morf’s warmth and excitement for the people around him preceded his climbing ability and seems to be an enduring part of his life. There isn’t a recipe to recreate here other than that intention, commitment, and privilege go a long way, and that things are easier—and better—with your friends. You can YouTube a lot of things, and then at some point you just have to go do it. Ethan Morf is doing it, and, as Morf and the other Gen Z kids say, it is coo-coo bananas.

The post Ethan Morf, the Youngest Person to Free El Cap in a Day, Is Just Getting Started appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

“I basically had a personal trainer!” our reviewer raved. “I don’t know what else I could’ve even asked for.”

The post Coach Reviews: Why Steve Bechtel’s Training Team Blew Us Away appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Climb Strong—the brainchild of Steve Bechtel—is a multi-coach hive of services, offering highly personalized coaching and a plethora of free information. They have coached some truly badass climbers. For four months in autumn 2023, I trained with them too. Here’s the gist: I reviewed a very comprehensive, expensive, one-on-one personal training plan created by a knowledgeable team and delivered by a brilliant coach, Ken Klein.

What I liked about working with Climb Strong was the general feeling of transparency and care. “There is every chance you can improve without having to hire a coach right away,” Bechtel writes on their website. “We have hundreds of articles available on the Climb Strong website, hours of in-depth video, and dozens of template training plans. Only once you’ve exhausted these resources do we suggest you get in touch.”

I really like that!

Me

My name is Nat. I’m 23, and am a White, cisgendered-male Canadian. I’ve been climbing for around seven years, and have trained consistently for the last four winters, but never with a plan prescribed by a coach. I like training. My training “plans” have always been made with the consultation of friends (some of whom have taken extensive training plans similar to this one), the internet, and my own imagination. Not scientific, but, so far, effective and fun.

I consider myself quite goal-oriented, and usually train with specific routes in mind. These routes are almost always single-pitch trad routes or multi-pitch free climbs. I have redpointed 5.14b. I sometimes climb 5.13 in a handful of tries. I often fall on 5.11, 5.12, and 5.13; in December, I learned I can’t climb 5.11a with a backpack on. For this training block, my goal was primarily to build a solid foundation for a few varied goals in the spring (a couple single pitch trad routes, and a long multi-pitch). I also had some time off school and went on a short climbing trip around Halloween, which the training adjusted to. Generally speaking, I consider my weakness to be endurance; most of my hard redpoints have been short, punchy climbs.

While reviewing this plan I was a full-time student living in a city with a very subpar climbing gym by 2024 standards. The gym had a Tension Board, weight plates (brought to the gym by members), a pull-up bar, and some hangboards including a Beastmaker 2000. There was no campus board, no dedicated weight room or equipment beyond the plates (and what folks brought from home), and the boulders were reset every four months. I also had access to a standard fitness gym, which was a two-minute drive from the climbing gym.

The plan

I reviewed Climb Strong’s premium coaching plan from September to December 2023. This would have cost me $460 month-to-month, or $325 per month with a year-long commitment. It was a privilege to review this plan, because I will likely never be able (or willing) to spend that much on coaching. This plan includes a monthly training schedule, weekly meeting with a coach, weekly program adjustments, and same-day responses from your coach; I basically had a personal trainer! It was way more than I needed, to be honest, but the sheer amount of support justified the price to me; I don’t really know what else I could’ve even asked for. If the cost of the program was coming out of my own wallet, I’d probably choose the one-hour consultation option ($140) with a coach (you can pick any Climb Strong coach) to consult on a training plan I constructed myself.

The coach

Based on your focus (bouldering, route climbing, alpine/big wall climbing), you can select your coach. My coach was Ken Klein, a Certified Personal Trainer and Certified Performance Climbing Coach. I found Ken to be knowledgeable, accommodating to my schedule, transparent, and excited.

Execution of the plan

The plan began with an extensive survey. There were questions on my climbing experience, goals, available equipment, time commitments, levels of stress, sleep, how much I smoke/drink (apparently you can put a price on morale), and any accommodations I would like my coach to make regarding access and ability.

After that, I met with Ken for the first time to discuss my responses over a video chat. He had a plan ready within two weeks (which was mostly due to my availability, as I was still on a climbing trip and in the process of moving). I then did a classic assessment (max hangs)—but with a twist! The assessment was two days and included a max boulder (in a session) element, as well as a capacity bouldering session to test endurance. This was important, in hindsight, as the plan was quite demanding—and featured a lot of mid-level endurance training in preparation for my Halloween trip. I think Ken was more interested in my capacity to avoid injury, rather than setting a baseline from which to progress. This philosophy of incorporating actual climbing into the assessment phase is likely a result of an ethos I perceived from Climb Strong: you cannot replace climbing, and you shouldn’t try to; we’re training to go climbing. That certainly aligns with my own purpose and view of training.

The plan was delivered through the Fitness App. Within the app was a schedule showing days and assigned workouts, instructive videos on assigned workouts, and instant messaging with Ken. It was very accommodating and personalized. We aimed to do some workouts I really enjoyed, and some new ones that he thought would be applicable to my goals. If school was heavy one week, he’d pare the workouts back. There was a constant fine-tuning. I just showed up! It was bougie!

I’m not going to divulge the whole damn plan out of respect for the folks at Climb Strong (though they divulge a whole bunch of stuff for free), but here are some highlights of the actual training:

- The 3-6-9 hangboard protocol. I’ve already recommended this to friends and have incorporated it into my own plan. This is Climb Strong’s bread and butter.

- I spent a fair bit of time in the fitness gym, including squatting for the first time ever. This time in the gym was partly to accommodate for the lack of weight facilities at the climbing gym, I think, but it made the mid-level endurance training prescribed later feel much less sapping than it had in the past (that’s an anecdotal observation, for the record).

- I learned a lot about warming up. They have some great warm up routines that made me realize how shit I am at warming up. It isn’t complicated, just an array of lower and upper body exercises, but damn!

- The drills. Ken prescribed some legit climbing drills—one was to climb problems using only heel hooks, as I’m historically quite bad at heel hooks. It felt goofy, but wow, so helpful. (To anyone reading, it is sacrilegious to do this on someone’s project. Just don’t.)

The results

With a week off from school, I headed on my little climbing trip feeling strong and all fired up to SEND only to get sick and throw up in my mouth mid-redpoint attempt. So, no, I don’t have a very clear “I did X and got Z” training story for you. But—and this is big—I didn’t get injured, and felt like I was really pushing myself without feeling tweaky. I am genuinely pleased with the results and am implementing workouts I acquired from this plan (mostly lifting more weights, and the 3-6-9 hangboarding) into my own plan this winter.

I’d do the plan again, in a heartbeat, but as stated, it was out of my budget. Climb Strong’s consultation feature is more attractive to me, and I will continue to use their free resources to contribute to my own training plans.

I’d highly recommend training with Climb Strong

I can only speak from my experience and social location, but I was impressed by the flexibility and client-centered framework Climb Strong operated from. They’re the first to admit that there is no magical training plan and seem keen to stay at the cutting edge of training knowledge. They also just seem to care about their clients as human beings, understand the climbing community is not and should not be monolithic, and appear to have the framework to accommodate an individual’s unique needs. The bottom line: whatever you buy from Climb Strong, you’re going to get your money’s worth.

Read more coach reviews:

The post Coach Reviews: Why Steve Bechtel’s Training Team Blew Us Away appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Berthod first tried 'Cobra Crack' in 2005, gunning for the first free ascent. Shortly after, for reasons unknown, Berthod disappeared into a Swiss monastery, where he stayed for over a decade.

The post 19 Years Later, Didier Berthod Climbs ‘Cobra Crack’ (5.14 Trad) appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

On Tuesday, May 14, Didier Berthod completed a nearly 20-year saga with Squamish’s Cobra Crack by redpointing the legendary pitch. “It is more so the end of a book, than a chapter,” he told me yesterday on the lawn underneath the Stawamus Chief, where friends of Berthod had gathered to celebrate his send.

Berthod first tried Cobra Crack in 2005 and his efforts were heavily documented in the film First Ascent. Shortly after the film, Berthod disappeared into a Swiss monastery, where he stayed for over a decade. His name and brief moment in the limelight became a sort of shrouded lore.

The truth, of course, ran far deeper than rock climbing and was personal and murky. In 2022 Berthod returned to Squamish to try to reconcile with his daughter, who he had never met, and her mother. Since then, the 43-year-old Berthod has become a beloved staple of the contemporary Squamish community. Regarding his climbing, he’s also evolved, doing the first ascent of the Crack of Destiny (5.14b trad) last year (read my article about it here, which Berthod insisted ended with “I love rock climbing and I love you rock climbers!”). After Crack of Destiny, Berthod refocused on Cobra.

Berthod spent roughly two weeks projecting the 25-meter splitter in 2023, feeling fit and with an optimistic mindset. But after pulling over Cobra’s lip—quite runout, he took the final “jug” with his left hand but was too tired to hold it. A wild fall ensued, crashing into the wall wrist-first and breaking it. Pondering, Berthod joked that perhaps his relationship with the Cobra was cursed, and a redpoint wasn’t meant to be. On social media, he quickly added, “to reassure some of you, [no, I] won’t go into a monastery again….[But] I don’t know if I’ll be giving another go on this one.”

But he did it! Amity Warme, who belayed the ascent, said that Berthod floated the crux—in the V9/10 range—including the iconic mono-finger lock and subsequent invert. (He’s the only one I know who stops in the mono to place gear. Outrageous!) The mono-cam placement, for Berthod, was mandatory: “I couldn’t risk taking that fall again.” No matter. Pim Shaitosa, who filmed the ascent, said there was “no yelling, just rhythmic breathing and flowing movement; it was beautiful.”

View this post on Instagram

Regarding the send go, Berthod said that it felt like any other attempt: “I’d been up there so many times, I’ve placed that last cam so many times. So many one-hangs. This time it felt similar, only I didn’t one-hang—I’d come from the ground!”

Berthod dedicated his send to Mason Earle, a fellow Cobra ascensionist and friend whose battle with a chronic fatigue syndrome has prevented him from climbing for years. He also thanked his “two sun rays,” Thomasina and Cedar, for supporting him on this longstanding and very personal project. “I think I’ll see life a little differently after this,” Berthod said yesterday, between drags of a cigarette and amongst summer chatter under the Chief. “Today, the Cobra was a little bit more benevolent with me.”

Congratulations, Didier.

The post 19 Years Later, Didier Berthod Climbs ‘Cobra Crack’ (5.14 Trad) appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

'The Dark Side' is a deceivingly simple-looking line located on the Thriller Boulder, in the woods adjacent to Camp 4.

The post Carlo Traversi on Establishing Yosemite’s Hardest Boulder appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

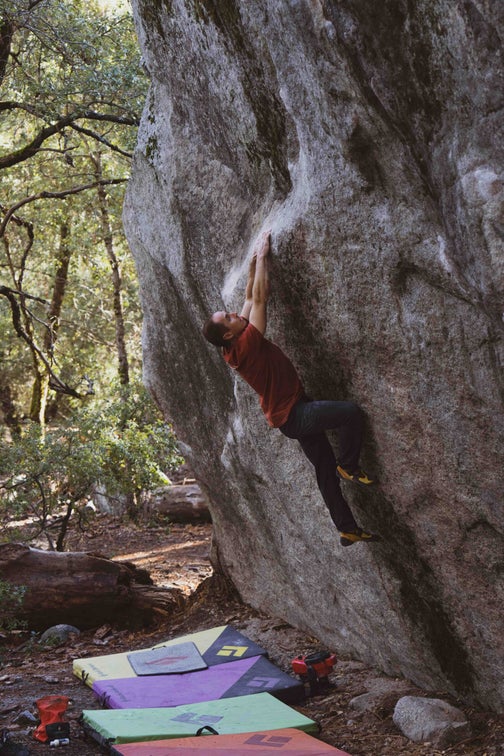

On December 23, 2023, Carlo Traversi topped out The Dark Side (V16), completing the first ascent of his (and Yosemite’s) hardest boulder problem. The Dark Side is located on the Thriller Boulder, in the woods adjacent to Camp 4. It is a deceivingly simple-looking line that follows a long, right-trending sloper rail, joining The Force (V9) near the lip.

Traversi, 35, has pursued hard climbing in Yosemite for the last decade. He’s redpointed 5.14c gear lines like Magic Line and Meltdown (second ascent), as well as Tieranny (V14, also second ascent). Traversi is one of the few at the cutting edge of both bouldering and trad climbing (and he’s climbed 5.15 on bolts), consistently chipping away at this or that project, spanning across the mediums. The Dark Side is his latest chapter: “a culmination of all those years.”

Climbing spoke with Traversi over the phone shortly after his ascent. His words have been edited for clarity and length.

On learning about The Dark Side

Traversi: When I got the Camp 4 “Bouldering Tour” when I was really young, in maybe 2003, I remember seeing Thriller (V10), but when you look at the left side of that wall, where The Dark Side is, and there’s no chalk, it doesn’t look like there’s a boulder problem. I couldn’t see it then. I still couldn’t see it when I did Thriller on a trip in 2009 or so. It wasn’t until I came back in 2013 that I thought, oh, this is something. There’s something here. Really, we just saw this cool sloper rail in the middle of the boulder problem and it was just this funny, I wonder if we can even hang on those slopers kind of thing. In 2013 I’d already climbed V15, and I remember not being able to hold the sloper rail then. I could hold the position off a ladder, but not really. I kept checking in on The Dark Side over the course of the last 10 years. I didn’t really start actively trying it until around 2015.

On The Dark Side itself

The Dark Side has a V9 intro into a sustained V15, and those intro moves change the setup for the crux. All told, it is 17 moves from start to lip.

It starts off on a jug rail, an actual jug! The feature continues and it becomes a slopey—but good—hold for your right hand, and then you get these two really, really bad crimps: the crux holds. The left hand is the one that you spend the most time on, and there’s a crystal that goes right into your index pad, that’s the one that splits. You load the left hand, and basically put all your weight on it to reset your feet. Then you do a big lock off and enter the sloper-rail section.

The sloper rail is really bad. One of the worst slopers I’ve ever grabbed, for sure. You shuffle along this rail for eight or nine hand movements. It really feels like you’re hangboarding on the Beastmaker 2000 45-degree sloper. Then you get into this crimp rail, which is better than the crimps at the beginning but still very thin. That puts you into a high gaston, and then one last big lock off to a hold that is basically the end of The Force, which comes in from the right.

The Dark Side is weird for a hard problem. I’ve never seen a problem that is V15 or harder that looks like it. It either looks impossible without chalk on it, or it looks kind of chill when it’s chalked up.

On climbing on the problem with others

The communal aspect of the climbing in Yosemite is one of the things that I appreciate the most. Especially in the winter, it feels like this family environment: I know almost everybody who’s bouldering there in the winter. If I don’t know them, it seems like everyone has this same mindset in treating other people with respect and being encouraging. That feeling of community is a huge part of what makes it one of my favourite places to be and I hope that tradition remains.

I think Randy Puro started The Dark Side around the same time I did. Randy’s a legend, he’s a magician on the Valley granite, especially on the boulders. Then, I think in 2020, I climbed on it with Jimmy Webb and Shawn Raboutou. Jimmy got really close. I thought for sure he was going to do it; he had it in two overlapping sections. I was doing well, but I didn’t feel like a send was imminent, and the frustrations of projecting were getting to me. Shawn looked pretty good on it too, but he was on a shorter trip.

I think Jimmy got frustrated by the split fingertip situation. There’s a hold on it that often splits your tip after one try. It kind of gets into your head, you’re like, I get one try from the ground today. If I don’t send it, I’m probably going to split my tip, and I won’t be able to try it for another 10 days. I think Jimmy got into that, and I think he said he had 10 or 15 days like that and got really close but also frustrated. Of course he was physically capable of doing it, it just didn’t work out.

On the fickle nature of the boulder

That’s the thing about this boulder problem; a lot of people are physically capable of climbing it. I don’t pretend to be the strongest or think I’m the strongest. It is just a really unique boulder problem: so many things have to line up (conditions, skin) and then you have to execute, and if you don’t execute, you don’t really get extra tries. A boulder like that is rare. Plus, it is frustrating, you know, to rely so much on things that aren’t in your control. Jimmy and I joked about how if the conditions were always perfect, and you never split your tip on it, it would probably be V14. But that’s not what it is. It is super fickle. And the conditions are super fickle! The window that I climbed it in was twenty minutes. On either end of that window I couldn’t pull on to sections that I can campus in good conditions. It is such an anomaly!

Some days I would go and I would only try the sloper rail because I knew that if I grabbed on to the crimps near the start I would split my tip. So I would try the sloper rail section and if it felt bad I would sit there for thirty minutes, wait for the conditions to change, and try it again, and if it felt good, I would be like okay, it’s good right now. I’ve got to try it from the bottom.

So I’d pull on from the bottom, and if you make one mistake on this thing, you’re off: if your finger is on the wrong crystal, you’re off—it was down to that level of nuance. Only, you weren’t just off, you’ve split your tip! Well, I guess I’ll try again in ten days. Some days, the sloper rail would never feel good and I wouldn’t even try from the start. It just wasn’t worth it. It was a lot of patience. It was an experience of patience.

On transitioning from “checking in” to focusing on the boulder

I was in the Valley in February 2023 hoping to climb on another project I was close on, but it was totally soaked and covered in ice—unclimbable. I tried to shovel off the snow and clean it up but it still wasn’t climbable. I wasn’t sure what to do, I really wanted to try hard that day. So I thought, I’ll go to Camp 4, I’ll do a little warm up circuit, and check in on The Dark Side.

I chalked it all up again. It had been about a year. The session started off terrible, but got better as the day progressed. I thought, okay, I’ll try it from the two crimps. That’s kind of a logical stand start; they are the highest holds you can reach from the ground, and they are the crux holds. So I pulled on from there, and it felt like velcro. I climbed it to the end, and it was just like holy shit, what just happened? Everything clicked. That was the first time. I couldn’t believe it.

I didn’t really want to call it a problem that day, because that wasn’t my original vision of starting on the obvious jug. I’m not a fan of multiple starts on problems, and that’s just not where the line starts: the rail keeps going lower. From those two crimps I think it is probably V15, and the lower start is maybe V8 or 9. But adding it in, especially with skin, ramps it up a lot—more than I expected, to be honest!

That day, I got pretty close to doing it from the bottom. I fell in the sloper section, after feeling kind of slippery. Turns out I split my tip on the crimp, and I was bleeding and slipping on my blood. I put another four or five days into it last year, trying to put it all together. Conditions. Splitting two more tips. It just didn’t line up. Then it got too hot.

Going into this season, I did feel this pressure to seize this opportunity with all the beta and knowledge I had acquired. There was this day two weeks before I did it where things really lined up: It felt insanely sticky, I did my warm-up circuit, I felt like I was on fire! I got one try and made a small mistake on the sloper rail, fell, saw that I split my tip, and that was that [laughs].

On the day he sent

It was a day trip from Sacramento. I didn’t feel particularly good warming up. There were a ton of people at the boulder, which isn’t normal for that time of year, and can be kind of distracting, but I thought, you know, I’m just going to hangout with everyone here, have a good time, and try my thing. Whatever. Everyone was super friendly, it was fun. I got two tries and it was pretty good. Not great, but pretty good. Mostly, I was just like holy shit, I’ve tried twice and haven’t split my tip. I didn’t even have a crease on my finger! I’ve never gotten three tries from the start on this thing, ever. So, I waited until the sloper rail felt pretty good, and then pulled on, and just kind of pulled through. It didn’t feel incredible. It felt like I was fighting through sections more than I should have, but things lined up.

I nearly passed out on top of the boulder. It felt like a weird dream. It is a weird moment to have. You’re so used to failing. I had to go check the video camera to make sure I actually did it!

Hard climbing is so special for that, it really taps you into this strange flow state. Everything you’ve learned in climbing, everything you’ve programmed, is just at work. You’re not telling yourself anything. Your body is doing what it knows to do.

On 20 years in Yosemite Valley, and being a part of history

Yosemite is a place where I’ve poured so much time and energy as a climber. It was the first place I really climbed outside, and I put so much time in here when I was younger, and took beat down after beat down. I’ve had so many humbling experiences here where I really felt like I was a terrible climber, and that I was never going to be good. So after twenty years it’s nice to have something that allows me to be like okay, I’ve mastered something here. Not everything, just one thing. There’s a lot more lessons to be learned for me in Yosemite, but I feel like The Dark Side is a nice culmination for all that work.

You don’t always get that satisfaction, you know? Sometimes you put all the work in, and make a lot of personal progress, but there’s nothing to show for it. That’s fine. But it is cool to have something that is a culmination of my time in Yosemite. There’s nowhere else where I’ve put so much time and energy. I felt like, for a long time, I didn’t have much to show for my time here. So this felt extra special in that regard; I proved something to myself.

I put the climbing history in Yosemite on a pedestal for so long, and now I did something that is a part of that. It is more important to me than I expected.

The post Carlo Traversi on Establishing Yosemite’s Hardest Boulder appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

It was the 23-year-old’s third free route on El Cap, after 'Golden Gate' and 'Freerider' in a day.

The post Sam Stroh Frees El Cap’s ‘El Corazón’ In a Day appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

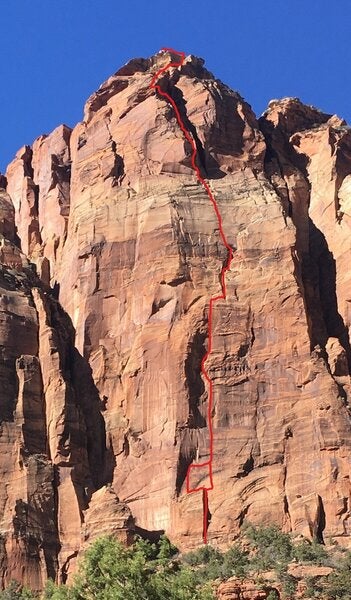

On Monday, November 13, 2023, Sam Stroh climbed El Capitan’s El Corazón (5.13b, 32 pitches) in 22 hours. Stroh is only the fourth person to climb the 3,000-foot route in a day, after Tommy Caldwell, Alex Honnold, and Brad Gobright.

Like many El Cap routes, El Corazón starts on Freeblast (5.11; 950ft). The route then follows various aid lines before sharing a finish with Golden Gate (5.13b). Of the 32 pitches, there are five 5.13s: The Beak Flake is low on the route. The Coffee Corner, The Roof Traverse, The Golden Desert, and The A5 Traverse are all back to back, about 20 pitches up. Corazón also features “very real” 5.12+ climbing on bird beaks, loose, runout 5.11 traversing, tenuous slab climbing, and 5.12 chimneying. “This climb has everything,” Stroh explained. “So many different styles. That’s the coolest thing. Also, it is extremely hard to follow, because it traverses so much. Major props to Will [Vidler, Stroh’s partner for the ascent].”

It was the 23-year-old’s third free route on El Cap (after Golden Gate and Freerider [in a day]), and, no, ECIAD doesn’t roll off the tongue like NIAD, or FRIAD. Alas, the Valley noticed this too, and coined the ascent CORAZIAD. Well played.

But what does free climbing El Cap in a day actually look like? Climbing eagerly sat down with Stroh to hear stories from his CORAZIAD. Below are snippets of that conversation. Sam Stroh. El Corazón in a day, in his words.

On climbing in Yosemite Valley

For one reason or another, everything kind of revolves around climbing in Yosemite Valley for myself and a bunch of my friends. You’ll be at the Buttermilks and think Oh, if I can do this hard boulder at the end of the day, I’ll be more prepared for doing a hard boulder at the end of the day on a hard El Cap route. If I do that one extra hard pitch, that’ll translate to the Freerider. There’s a certain weight, a certain history, and definitely a challenge to Valley climbing. El Cap isn’t easy. You aren’t just happy and cozy. It is a big challenge and it seems to matter a lot more—and weigh on us more.

Regarding Corazón, Adrian [Vanoni] and I had been working toward it for awhile. We did Freerider [both in a day, separately]. We did Golden Gate. One day Adrian said, “We should do Corazón.” And I was like “Maybe we should do it in a day. Why not?”

On the in-a-day style

We had done the ground-up, multi-day style, and we enjoyed that style. Trying to do Corazón in a day was a new way to explore free climbing on El Cap. Since we had already done the upper cruxes of Golden Gate, and the Freeblast, it seemed like a good one to not go ground up on.

We drew a ton of inspiration from Brad Gobright rapping in, rehearing routes on El Cap, and just doing them all in a day. We thought that was visionary: He did three El Cap routes in a day in one season (El Niño, Muir Wall, Golden Gate). The season before that he had done CORAZIAD and said it was the most challenging thing he’d ever done. We thought that was so rad. Brad was the man.

Plus, it is just so much better to not sleep on the wall. Prepping for an in-a-day ascent is such a joy. You climb a lot, but still sleep in your van. You can wake up, hangout with your friends, and have a longer morning. You do way more climbing; no stopping and faffing with ropes and bags. In-a-day ascents are still a lot of work, but just in a different way.

Previous attempts on El Corazón

We tried last fall [2022] but the Valley season was really short. It’s funny, I think we always talk about how rapping in is the easier style, but nobody ever talks about how hard it can be to rap into El Cap! I think on the first day I accidentally rapped into Magic Mushroom, or some random route [laughs].

It was kind of epic getting over to Tower to the People [prominent ledge between upper cruxes of El Corazón, shared with Golden Gate]. I had to swing out for like 30 feet, and then reverse-aid the crux roof, while on my GriGri, of Corazón. It was nauseatingly exposed. I was like God, this is so full value. We are not doing this correctly!

Anyway, we sorted it out, checked out the upper cruxes, and rapped all the way down to around pitch 15 or so: there’s an engaging (runout, above beaks) 5.12+ pitch, probably the most real 12+ I’ve done on El Cap. It’d be a proper onsight.

We got off of that recon mission all psyched and then it snowed about two feet. So we left. We went to Vegas, climbed some stuff, and went to the Cosmopolitan one night and played a bunch of roulette [laughs].

I went back to the Valley a few weeks later. I didn’t really feel ready, after three weeks away, but thought that I should have a go on Corazón while I was there, so I recruited bonecrusher Nik Berry. Long story short, we bonked below the Neitsche Chimney (19~ pitches up, right below the four 5.13s at the top). It was a Hail Mary attempt that only made it to the 50 yard line; I’m from Texas, as you can tell [laughs].

Then we went and lived our lives and came back this fall.

Leading up to El Corazón this year

From a climbing-as-an-athletic-pursuit standpoint, I didn’t have the most successful summer; things weren’t quite clicking. Adrian showed up climbing damn well after doing a 5.14 first ascent and Cobra Crack. And you could see it in his eyes. He was so psyched I had doubts he was sleeping. I’d been sick before going to the Valley and was like Dude, I just need to go hand jam. I reconsidered even trying Corazón. For the first while I didn’t feel at home on El Cap. The Freeblast felt slippery. The exposure felt intense. I had to start slow.

We would usually either jug fixed lines to Mammoth Terrace (9~ pitches up), or climb the Freeblast, and try the Beak Flake (5.13b). That pitch starts with a dynamic V7 boulder on diorite knobs to a full rest, and then mostly 12- climbing to a V5 boulder at the end. We sessioned that quite a few times. I wanted to get to the Beak Flake feeling like I hadn’t climbed at all.

Adrian and I would simul the Freeblast in two pitches in two-and-a-half hours. Then we would simul the next four pitches in an hour and try the Beak Flake once or twice. We’d be back on the ground by 1:30. It was so fun.

This was also the first season I had support from a shoe company, La Sportiva. Usually when I’m in the valley I have one pair of TC Pros and I have to make it work. That was different this year which was so nice. I blew through a pair of TCs in like two weeks from climbing the Freeblast so much.

We also did a four-day prep mission from the top, to dial in the 5.13s up there. Our friend, and brilliant photographer, Victoria [Kohner-Flanagan] came with us to take photos. After the recon mission, I stashed food and water on the route. A storm was looming in the forecast. So I rested for two days and went for it.

I was fully focused on CORAZIAD for three weeks. There’s so many people that come together for something like this to happen; you’re affecting people’s lives and asking them to accommodate you. That commitment and involvement of others increased the stress levels. Then I would forget beta when trying to visualize and just be in my van totally overwhelmed; There’s too much beta!

[Also read: Adrian Vanoni Frees Alpine 5.14 Crack on Prusik Peak]

The day of the ascent

Those nerves carried into the day I tried to do it. On the Beak Flake (the first crux pitch), physically I felt amazing, but I was so nervous that the feet felt small, and I was sort of shaking my way through it. I definitely relaxed a little after sending the Beak Flake and the next .12d R pitch.

I was worried about not giving myself a chance. I thought, If either of those pitches takes me multiple tries, I’d be too tired or slow for the upper cruxes. It would be over before it started. If I failed on the roof, or the A5, I would’ve thought that’s progress. This is a fucking hard, big goal, and that’s progress. I just wanted a chance.

Throughout the day, the biggest battles were just hanging out at belays while Will was cleaning. Many of the pitches are traversing and steep, and you’re unable to see your partner. I would go in and out of trying to get myself psyched up, and then the sun would bake me, and I’d get sleepy. Then I would go through a bunch of bad scenarios in my head.

But every time Will would get back to the belay, we would turn on some bitchin’ Lorde song, and he would psyche me up. It was so nice to give each other a hug, exchange some energy, and every time I started climbing again all the stress would go away. You know what, I’m climbing. I know how to do this shit. I was climbing well—faster than usual—and with way more confidence. No overreacting.

I had some mantras going through my mind: You owe it to yourself not to get scared right now. If I wasn’t trusting the gear I’d think You owe it to yourself to just place this piece and fire this. This is the day. It really helped.

The turning point on the ascent—when we got our second wind—(which, upon reflection, we realized lined up with when we took caffeine pills and ibuprofen) was at this stance below the Kierkegaard Chimney (5.12). I asked Will to remind me to stay relaxed. I tied in, and I don’t know what happened, but I just started chimneying like mad. It was crazy. I’ve never flowed up a chimney like that.

That whole corner system is so overhanging, and I remember getting into the steepness and just feeling like I had so much in my arms—below was mostly slab climbing! The next pitch is this epic hand crack, I just chainsawed up it! I was having so much fun.

Babsi [Zangerl] and Lara [Neumeier] had their portaledge below the Coffee Corner (5.13b). I hopped in their portaledge. I was buzzing stoked; straight wired. And then all of a sudden I got a massive cramp in my leg. I was mid-sentence and then went immediately into the fetal position [laughs]. They gave me some magnesium pills, Will rocked up and we had a big lunch, I had more caffeine pills, and it did the trick.

After the intermission, I tied in, put on “Perfect Places” by Lorde, and just fired the corner. I had these really specific ticked footholds for the crux chimneying sequence, but then I got there I didn’t care about the tick marks. I thought I’ve climbed 2,000 feet of granite to get here and my foot hasn’t popped off a single foothold. It isn’t going to now. I’m usually not like that.

I climbed it at sunset, with Babsi, Lara, and Will cheering me on. It was all-time.

It was totally dark when I set off for the roof crux pitch. I had never climbed it in the dark and was a bit concerned about seeing footholds. But Babsi and Lara took their headlamps and lit up the pitch with their headlamps. I also had friends on The Tower to the People, at the top of the pitch: my friends Tim [Greenwood] and Miška [Izakovičová] and their partners. They were watching me and cheering me on.

It was the crux, I needed a good song. Will put on “Make Me Feel”—the song from the Groove Train video. It hit the spot. I did the roof first try. My friends were cheering me on from either side and I just thought, Oh my god, I’m peaking!

I got into the Tower, hopped into Miška’s portaledge, where they had a cup of tea waiting for me! All of the support was amazing. Me and Will are both really into tea, so I made him a cup of tea when he got to the belay too. Eventually I tied in. Miška had her gear in the next pitch, Golden Desert (5.13a), and it just didn’t make sense for her to take it out, so I climbed it with her gear in. It ended up being quite a bit harder this way; Adrian and I use some straight-in jamming beta where most people layback, so the gear was in the foot jams. I barely stuck the jug at the end of the crux.

Then, I was sitting at the hanging belay below the A5 Traverse, and that was the heaviest moment. I was thinking about all the people that had been stopped by this pitch on their attempts on Golden Gate or Corazón. I know Brad [Gobright] fell there on an early Golden Gate attempt. And, I don’t know, I didn’t feel like I was on the level of people like Brad; I didn’t feel I was meant to be able to do it.

We were 19 hours in. Getting pretty tired. I changed my vibe a bit and put on “One Day More” from Les Miserables. I texted my girlfriend Madeleine and told her: One more crux. The A5. Pretty nervous. We love Ted Lasso; she just hit me with: Believe.

I pulled onto the A5. Because I couldn’t see my feet in the dark, I ended up campusing the start of the traverse basically, and got pumped. [We hope “One Day More” is playing for you, dear reader.] I did the exit sequence, which has this cool karate kick to a toe hook, and was thinking This is so cool.

My moment wasn’t on top, it was on this really large ledge below the last pitch. I laid down on this recliner-shaped feature in the rock, listened to “Into Your Arms” by Nick Cave looked at the stars, and was like Wow, that was so fucking cool. That’s the part you can’t really articulate, it’d be like asking someone to talk about their ego dissolving on psychedelics. Yeah, that part is really hard to think back on.

But you know what moments aren’t as fleeting? Hanging out in Babsi’s portaledge. Having a cup of tea on the tower with Miška. Interacting with Will throughout the day. I feel like those moments happened yesterday. But sitting on top of the summit feels like it was years ago.

I’m super proud of what I’ve done. Us climbers that are really trying to push ourselves just aren’t impressed easily; we’re so critical of our performance. But in that moment, I wasn’t thinking about next season at all, I was really psyched.

There’s also a sense of relief. There’s a lot that goes into the in-a-day style. And a lot of people supporting us; that adds pressure. You’ve had so many days of stashing, rehearsing, trying. I think it’s hard not to feel a sense of relief that it’s done.

The post Sam Stroh Frees El Cap’s ‘El Corazón’ In a Day appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

‘Prayer for a Friend’ joins a growing list of impressive multi-pitch free climbs in Washington.

The post Adrian Vanoni Frees Alpine 5.14 Crack on Prusik Peak, WA appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

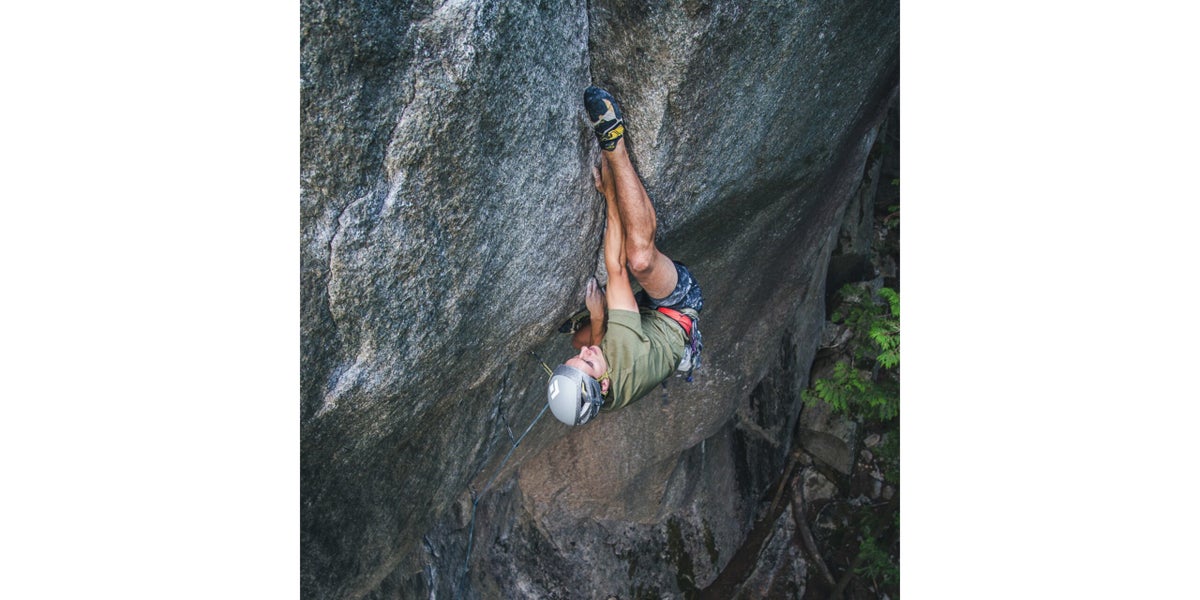

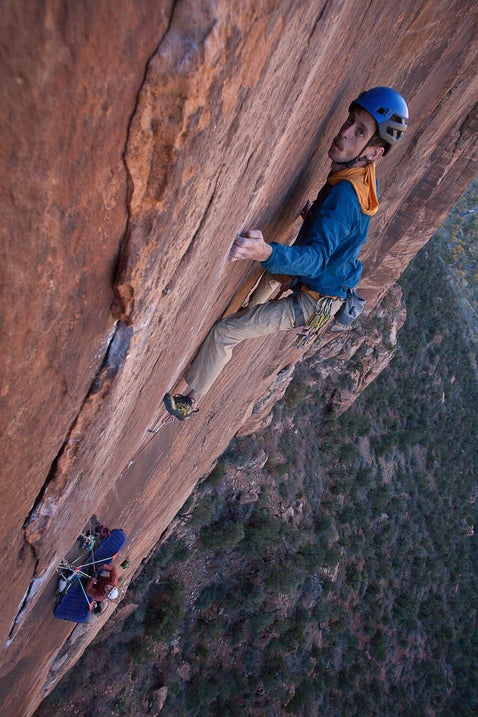

On October 5 and 6 Adrian Vanoni freed each pitch of Prayer For A Friend (5.14a; 600ft), a 20-year project on Washington’s Prusik Peak. Prayer wanders between crack systems for five technical, mentally demanding pitches (up to 5.12-) before a distinct crescendo: A striking overhung finger crack breaching an otherwise blank headwall. Some have called the crux pitch an alpine Cobra Crack.

The story of Prayer is intergenerational, and began with Fitz Cahall two decades ago. “Prusik Peak is iconic, especially if you live in Washington,” Cahall said, recounting his first glimpse of what is now Prayer. In the early 2000s, the longtime Pacific Northwesterner was enjoying a day of soloing multiple peaks in the Enchantment Range. “I had an awesome day, and was going up the West Ridge (5.7; 400ft) of Prusik, which goes right by Prayer; holy good God!” The West Ridge is classic, and Cahall knew that thousands of eyes had likely seen the lichen-specked splitter he was gawking at, but, alas, in this era there was no quick way to learn more about the line. Cahall made a mental note to investigate its history when he returned from the mountains, but life had different plans. He had missed many calls whilst in the mountains, and soon learned that one of his close highschool friends had died from a rare form of cancer. The splitter on Prusik slowly became a memorial: A Prayer For A Friend.

After some digging, Cahall learned that the splitter was likely untouched. He recruited his life partner Becca Cahall and their friend Aaron Webb to check out the entire 600-foot feature, spending the next three summers slowly learning its nuances. Cahall sandbagged himself on an early attempt, questing up the 5.11 face-climbing pitches with minimal use of the drill. He’d have to stomach his preliminary boldness time and time again while enroute to work the crux pitch. Nik Berry would later add a few bolts to this lower section, with Cahall’s permission. After three summers of effort, Cahall was still far from redpointing the crux splitter. “It was a powerful experience, those three seasons. But other things started happening in my life,” he said.

Other things. Cahall was expanding, and his inspiration went toward other creative expressions. He began making films under Duct Tape Then Beer, and telling stories on The Dirtbag Diaries podcast, and now Climbing Gold, too. In addition to becoming one of his generation’s prominent storytellers, Fitz and Becca welcomed their first child in 2011.

Prayer For A Friend served its purpose in Cahall’s life. It was a way to connect with himself and his friends—living and dead. Around 2007, it was time to pass the torch.

***

“I have hiked 80 miles in the past two weeks in rain, snow, heat, and 40 mile per hour wind to work on A Prayer for a Friend,” Nik Berry wrote in a 2018 social media post. Berry had gone all in on the razor splitter beneath Prusik Peak’s summit. “After having so much success in Yosemite [this season] it feels motivating to fail on an objective. … This route will provide ample motivation for future training sessions.” He returned the following season, logging more hours on the biting tips crack, but again fell short. “You never forget the ones that got away,” he later wrote. Berry couldn’t be reached for this article.

***

When Cahall was piecing together Prayer during those early 2003 forays, the line’s eventual first free ascensionist—Adrian Vanoni—was a toddler in the Seattle suburbs. Twenty years later, that toddler has grown up into one of America’s elite budding trad climbers. Vanoni has iconic cracks and big walls like Cobra Crack (5.14b) City Park (5.13d), Stingray (5.13d), and Golden Gate (5.13b; 3000ft) in his rearview mirror, but his climbing has remained centered around Prusik Peak; he’s a proud Washingtonian, after all.

“I climbed the Stanley-Bergner (5.10a; 500ft) in 2019, when I was nineteen,” he told Climbing “It was transformational—took us 18 hours!” Vanoni returned to Prusik a year later to solo the Beckey-Davis (5.9; 650ft). After summiting, he down-climbed the West Ridge and saw what Cahall, Berry, and countless others had: Splitter cracks shooting up a headwall. Prayer. Vanoni was entranced but also out of his league: “I thought, one day someone is going to do it, and then I’ll try to do it too, eventually.” He took a photo of the headwall, made it the background of his phone, where it remained for most of the next two years, and continued climbing in earnest.

After climbing Index’s City Park (5.13d) in 2022—a life-achievement route in Washington—Vanoni thought it was time to revisit Prayer. He walked the 10-mile approach alone, had a mini-epic trying to rappel into the route (“I built this shitty anchor unbeknownst that there were bolts pretty much right next to me. It was a whole thing.”), and eventually got acquainted with the moves in isolation. Vanoni returned a week later but quickly injured his finger on the steep crux fingerlocks. Nursing his injury, Vanoni and his friend toured other routes on Prusik and he hiked out of that trip having climbed nearly every route on the peak. Prayer loomed.

Prayer became a constant in Vanoni’s life. It was a guiding force. This year, he returned to Prusik multiple times. On one trip, he shiver-bivied with a friend and barely climbed. Another time, he shared Krispy Kreme donuts with strangers on the long approach. And, of course, he started to connect the dots on the crux pitch. After one-hanging the crux, Vanoni realized he was ready to start trying the route from the ground.

Even with the newly added bolts, Vanoni found the lower pitches hard, runout, and taxing. By the time he’d freed the first five pitches—onsighting all but one 5.11—the crux splitter was in the sun. He tried anyway, and when he fell out of the painful locks he chose to top out and return to camp.

The next day Vanoni returned, soloing alongside Will Vidler up the West Ridge—a route that was now like an old friend—to rappel into the crux and write the conclusion of his Prayer chapter. “I one-hung it again on my first attempt, and found some slightly better beta. Afterward, I was sitting on the ledge in the sun with Will and I just knew it was time. I had that feeling. I put on Gold Lion, by the Yeah Yeah Yeahs, and I just knew. I executed perfectly and got to this finger lock that marks the end of the difficulties. I sat there for a while, taking in the exposure, looking at the beautiful lichen, and smiling at Will. I couldn’t believe it.”

On paper, Vanoni’s ascent wasn’t perfect. He will be the first to tell you that. He was initially hesitant about even claiming a free ascent, thinking about Cahall, Berry, and the others that had put time into the route, and fearing sacrilege. “It was such a special line,” he explained, “that I didn’t want to marr it with any imperfection of style.” Not perfect, but, by all accounts, special (and technically imperfection, in this context, still included redpointing 5.14 ten miles into the backcountry). Vanoni warmly invites anyone interested to improve on his non-continuous style. For him, Prayer has served its purpose.

Sitting in his van in Yosemite Village, Vanoni concluded his reflections with this:

“If the rock climb was the sole motivator, I think Prayer would be really brutal. It’s sharp. It’s hard. It’s an amazing route, but it’s a lot of work. If I hadn’t had the mindset of just sharing this place with my friends and then climbing the route in the process, I would have had a very different experience.”

The post Adrian Vanoni Frees Alpine 5.14 Crack on Prusik Peak, WA appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

The 20-year-old sent four 5.14s (two trad, two bolted, all classic) and two 5.13 stem corners, in just over a month.

The post Connor Herson Just Hiked ‘Cobra Crack’ and 5 Other Squamish Testpieces appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

When Connor Herson clipped the chains on Spirit Quest (5.14d) earlier this month, he wrapped up an outrageous month of granite climbing in Squamish, BC. Spirit Quest was the twenty-year-old’s seventieth 5.14. It was preceded by rapid ascents of The Crack of Destiny (5.14b, trad), Cobra Crack (5.14b, trad), Spirit of The West (5.14a, sport), Tainted Love (5.13d R, trad), and a flash of Stélmexw (5.13c, sport). He also nearly onsighted The Shadow (5.13a), which ended with “an annoying foot slip.” Mind-blowing. Myself and the Squamish community at large have made too many jokes about Connor Herson dispatching our projects in a few tries; the world needs an interview about this!

I climbed with Herson once this spring in Indian Creek, and a handful of times in Squamish this summer. He struck me as someone who is obsessed with climbing and very much views climbing as a craft: His beta is almost always unique, and if there is a no-hands rest on a rock climb, Connor Herson will find it. For example, his Cobra Crack beta was not the traditional mono, but rather an individualized version of Sonnie Trotter’s beta used on the first free ascent. On The Crack of Destiny, Herson found (and used) an improbable no hands bat-hang before the redpoint crux—rock climbing, a craft.

In many ways, Herson’s summer in Squamish was like that of any other college student. He was obsessed with climbing, psyched on scoring free food, and was struggling with his skin on the sharp granite.

Only this time, the college student who spent summer break in a Subaru that has a slow leak in the front-right tire isn’t some kid recounting his forty-footer on Angel’s Crest. It is Connor Herson, and he’s on a rampage. A quiet, normal, absolutely ridiculous rampage. Our conversation was edited for clarity and length.

“This is my first time climbing outdoors outside of the US. It makes me realize that there is so much good rock out there [laughs].”

Climbing: How long was your trip?

Herson: It was initially supposed to be a month. It has been about five weeks now. I got here at the start of July. The first week or so I didn’t really send anything; conditions were bad and I was getting used to the area. It felt like a bit of a smackdown. Then something just kind of clicked.

Tainted Love (5.13d R)

Herson: I did Tainted Love on my birthday, July 8. It took me two days. That one was cool. I’ve actually never whipped on a nut before [that wasn’t fixed], but that pitch is all RPs! It was a mental challenge! I rehearsed it on top rope and sent it my first go on lead, so I guess I’ve kept that streak alive.

Climbing: You said you felt like you weren’t having a successful climbing year up to that point, and that Tainted Love was a big confidence boost.

Herson: Yeah, this spring I was busy with school. The weather was bad. I was struggling to go climbing at all, and when I did I was in my head. I tried The Carbondale Short Bus [5.14a R] this spring and felt like I could do it, but just didn’t. There were a number of situations like that all spring. Coming into this trip—especially after getting smacked down the first week—I was like “Oh man, this is still happening.” Doing Tainted Love felt like a relief, almost.

I think I just felt grateful to be able to try hard, to have time, to be able to focus, and to push myself without mental barriers or doubt. I felt grateful just to be able to go for it.

Climbing: What changed in terms of mental barriers and doubts?

Herson: Not having school was huge. There were no distractions. Being in a new area and climbing on this amazing route [Tainted Love.] I was just fully immersed in the climbing. The rock is amazing. And I was up there with Brent [Barghahn]; he’s such good energy. We were having a great time. It reminded me why I love climbing.

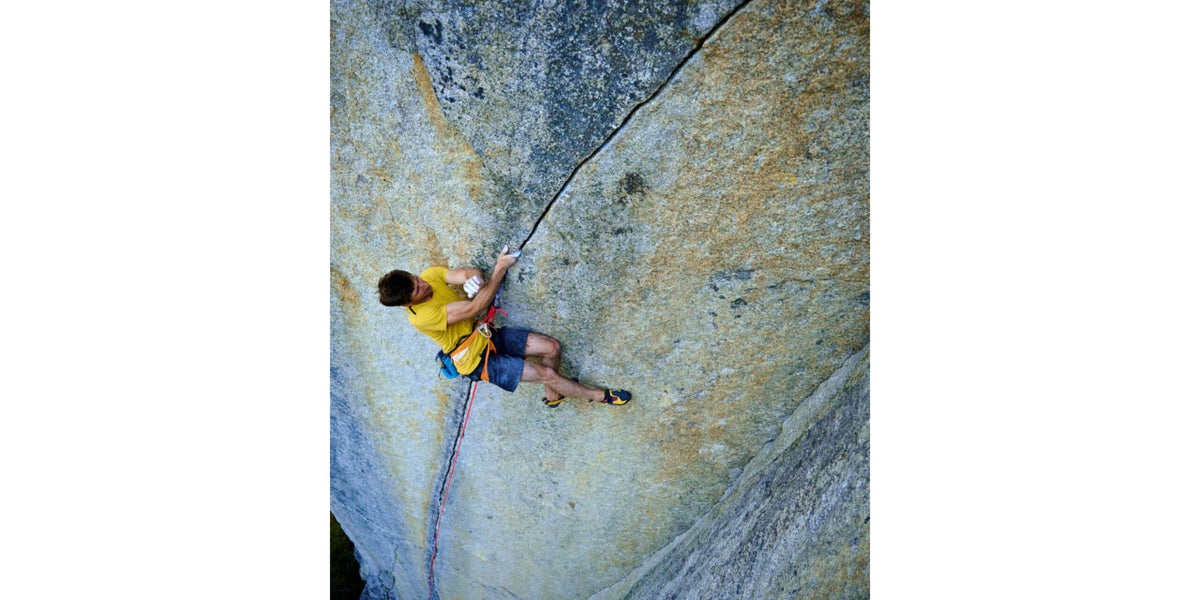

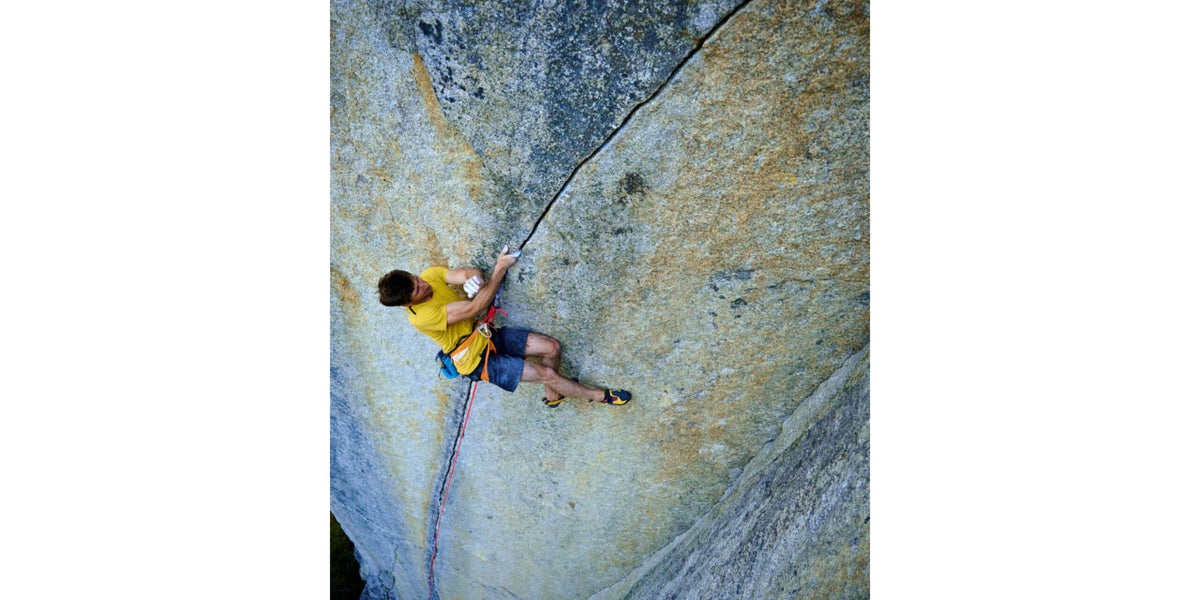

Cobra Crack (5.14b)

Herson: Cobra took me four days. My first session on Cobra, it was a really hot day. It was humid. It was still. The holds felt slimy. Going up that day I was like, “Maybe I’ll give it a flash go, but I didn’t make it very far on my flash go, just into the flake [the first crux.]” That session I realized that I couldn’t fit the mono [a single-finger jam that is the most commonly used beta mid-route.] I was trying with my index finger instead of my middle finger. I got a few gobies that day; overall, pretty discouraging.

After Tainted Love, I came back and conditions were way nicer, and I was more confident. That day, I found a way to do the mono with just the tip of my middle finger. I linked from below the mono to the top and just thought “Oh I’ll try to send it next go.” I fell pretty low down on that go, and I couldn’t do the mono move again. So I started experimenting with Sonnie’s [Trotter] beta in order to skip the mono. [Trotter switched his hands in the set-up for the mono beta, and did a long, powerful move to a finger lock just past the mono hold.] I found that I could do that. It was maybe a bit more powerful but it was so much higher percentage. I got really psyched on that beta.

I went back the next day and I learned that two days in a row on Cobra is not the way. I made no progress. My skin was bad and I had to tape. I learned that I should just let my skin heal so I can try it with no tape.

I took a rest day, and climbed at Paradise Wall for two days—I actually did Queen Bee (5.13c) and Spirit of The West (5.14a) during those two days—and then took another rest day and came back to Cobra.

I wasn’t really sure what to expect, but I had my beta. I decided to just tape my right pinky and nothing else. That day, I got to the crux from the ground, and then I got through it. I got to the lock that you invert off of, and my tape started sliding. I did the invert, tape still sliding, and then, doing the last left hand move, the tape fully slid. I fell.

I decided for my next go I’d take the risk and not tape at all. I ended up sending. It was a risk—I actually got two gobies—but it paid off. Thankfully I did it—I would’ve had to take a week off of the Cobra with those gobies!

Climbing: What’s that like for you, to come here and climb this iconic route, and to do it fast. What do you make of that?

Herson: It is really special. Growing up, I saw all the videos on that route. One of my favorite videos of all time is the Mason Earle video. That route was on my life list, and at the top of my list going into this trip. It was a dream line. It always has been. Realizing that it was a climb that I could do and not just a route I thought was amazing… that is really cool. That feeling of growing up, seeing a climb that feels next level, and then progressing to a point where it’s possible.

I heard from a lot of people that it was super sharp and heinous on your skin. What I learned from climbing on it was that the sharpness adds to the experience. It was less painful than I expected, especially after the first few days. You can sort of use the crystals to your advantage!

Stélmexw (5.13c, five pitches)

Herson: The day after I sent Cobra I went back to Paradise and started trying Spirit Quest. Third day on, I went up to Stélmexw. The plan was just to check it out. No expectations. Jesse [Huey] had been very vague about the grade, he said he thought it could be 13a or 14a, and settled on 13+. We were more planning on checking it out and trying to do it the next day rather than doing it in a day.

I slipped on one of the 5.11 approach pitches which was annoying. I lowered and redpointed it. Whatever. Anyway, we got up to the crux pitch, that corner, and Brent [Barghahn] chalked some holds and hung the draws. He was like, “Connor, you should try to flash this.”

And, yeah, I flashed it.

I was surprised. The important detail about that pitch is it is this perfect stemming corner. It isn’t really sequential. You don’t really have to learn a sequence.

Climbing: It is kind of interesting that you flashed that, but didn’t onsight The Shadow, which is easier on paper.

Herson: Yeah, that’s just how it goes on corners like that. There’s such an element of luck to doing climbs first go. On The Shadow, I felt solid and all of a sudden I was off. On Stélmexw I didn’t feel as solid, but I stayed on. It is fickle and risky, but it is nice when it works out. Brent sent second go, with shoes that were too big. That was really cool to watch. He had to work for it. I could tell that it was a pitch where if he had good shoes he would’ve hiked it, but his feet were sliding all over the footholds and he still did it.

We both did the 12c exit pitch first go. It was a crazy day. A great day.

The Crack of Destiny (5.14b)

Herson: It is perfect. It looks straight out of Indian Creek. My first reaction was “Why wasn’t this done earlier?” I was surprised that no one had given it a really focused effort until Didier [Berthod], cause it is such a beautiful climb. As soon as I sent Cobra though (and my skin healed) I switched my focus to Crack of Destiny.

My first session, I thought the moves were easier than Cobra but it was so much more sustained, and it was really hard to remember a sequence. In that sense it was very different from Cobra; having a sequence is really important. Destiny breaks down into a hard, thin crux at the bottom, and then easier climbing that gradually ramps up, culminating in the crux transition back into North Star. The route stands out because it is such a uniform crack: I probably didn’t climb the route the same way twice!

I was able to get through the first two thirds without a sequence but I really had to have one in the upper third. The next day, I found a really good sequence up there, and got through the entire crack. Climbing through it didn’t feel that hard. I got into the resting jug on North Star, and I thought I was recovering. But wow, that crux on North Star [V8] was so much harder than I thought it would be. When I did North Star alone the crux felt quite easy, I got there totally fresh. But that wasn’t the case on Destiny. I got into the top boulder and the pump went from 0 to 100 and I hit the second last hold with my fingers opening. There was no saving that. I fell on the last move.

I went back three days later with you [Nat Bailey] and Ben [Harnden]. It was such a good day. I knew I could get through the crack. It went really nicely. I was able to workout a bat-hang in the North Star rest and was able to recover enough. It felt really really nice. Harder than when I just did North Star, but it felt like I had some margin. It was just such good energy, with you and Ben. I remember hitting that final jug on the lip of the Chief and everyone was so psyched. I was psyched you two were there. The energy was so good. It was just a great day.

Spirit Quest (5.14d)

Herson: I think Spirit Quest was six days all in. The first session I got it in three sections. I was there with Connor [Runge] and he was psyched, had great beta, and it was such a good day. I had a session where I didn’t feel like I made progress, but then on my third day I fell getting back into Spirit of The West, [quite high on the route]. Then I fell way lower on my next session. Lots of ups and downs.

But man, what a route. I thought maybe it would be just a heinous, short, direct start into Spirit of The West, but there is a lot of independent climbing. Just a lot of V8-V10 climbing with no really good rests. Sustained, good climbing. It is really technical; a lot of the moves you can do when you’re pumped because you’re on your feet, but you still get really pumped. It is crazy that there is such a sustained, natural, beautiful line on granite. That seems really rare.

Climbing: What are your takeaways from the summer?

Herson: Enjoy the process. Even those attempts that feel like you should’ve sent or those days that feel like you should’ve been better are still days out on rock with friends and are still really good days. Learning to see that silver lining is something I’ve struggled with on this trip, but learned a lot about. Plus, every single route I’ve done here I would say is a five-star line. Totally mega. What’s not to like about that? Even when I’ve been getting close and falling this summer it hasn’t been the same. On Cobra Crack, Crack of Destiny, and Spirit Quest I had really high falls. Immediately afterward I was just psyched to be there. Instead of being hard on myself, the mindset was just like, “Oh, I get to climb it again!” I also began to think of those falls as like, “Wow, I can do this climb.” After each of those attempts where I fell really high, the routes just felt more doable.

It is ironic because on this trip I wasn’t super performance-focused and I think not putting the pressure on myself made the difference.

Climbing: Anything else you’d like to add?

Herson: Two weeks ago I was thinking “I want to send Destiny and Spirit Quest and then I’ll go home.” But now that I’ve sent those two, I don’t really want to go home! Maybe I will though, I just bought my seventh pack of Band-aids in a month!

Also Read:

- Scarpa’s Best Crack-Climbing Shoe is the New Generator

- 5.13 Walls and 3000-Foot Alpine Faces Climbed in Pakistan; 5.14c Flash First Ascent

- What I learned Watching Drew Ruana Knock Down a Nemesis Boulder

The post Connor Herson Just Hiked ‘Cobra Crack’ and 5 Other Squamish Testpieces appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

After quitting climbing to join a Swiss monastery in the early 2000s, Berthod returned to Squamish with two goals.

The post Didier Berthod Returns to Climbing Limelight With FA of 5.14 Crack appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

On June 23, Didier Berthod completed the first ascent of The Crack of Destiny, an airy single-pitch finger crack at the top of the Stawamus Chief in Squamish, BC. The Crack of Destiny—clocking in at anywhere from 5.14a to 5.14c—is now one of the hardest finger cracks on the planet (and the most beautiful, Berthod emphasizes).

This story is much bigger than another hard first ascent. For nearly two decades, Berthod’s place in climbing lore was one of mystery and gossip. After establishing multiple crack climbs on the cutting edge (Greenspit, Learning to Fly, From Switzerland With Love) in the early 2000s, Berthod vanished from the scene and joined a Swiss monastery for reasons unclear, a story famously documented in the film First Ascent. He returned to Squamish over a decade later, not for climbing, he happily says, but to try to make amends with his daughter and her mother. “But I love climbing, so, I’m going to climb.” Enter, The Crack of Destiny.

The Crack of Destiny was a long-standing open project that shares a beginning and end with the 5.13b trad testpiece North Star. North Star follows 5.11 climbing up a laser-cut, Bugaboo-esque dihedral before a slap-in-the-face V7 at the lip. Jeremy Blumel—North Star’s first ascensionist—told me that he and his friends had stared at Destiny for years: an independent finger crack that splits the left wall of the dihedral, before traversing back right just before North Star’s crux.

Berthod’s bid on Destiny wasn’t the first. Many folks have tried it over the years, from some of the world’s best crack climbers to the anonymously curious. “I first heard about it in 2008. It was one of those mythical projects,” Mason Earle told me, who tried the line briefly in 2017.

Sonnie Trotter tried the line in “2010 or 2011” when a direct finish looked feasible. “A key hold broke on Will [Stanhope] when he went to check out, and I haven’t been back since,” he said. Stanhope added: “I thought going out right was too thin. Pretty cool that Didier proved me wrong.”

Many dabbled—some more seriously than others—but for some reason no one went all-in on the notorious splitter beside North Star. Perhaps it was the lore, or the hour-long hike, or just the fact that things in life have to line up to climb a crack that hard. For locals and traveling professionals, that never happened on Destiny. Sam Eastman—a local—told me he had tried it “way back in the day,” and did the splitter portion of the route but couldn’t figure out either exit. More recently, Stu Smith—one of the strongest Canadian trad climbers you’ve never heard of—put in a few days last season, calling it “the single greatest bit of crack climbing, hands down.” You get the point: a lot of capable folks have checked Destiny out; a few of them with the Cobra Crack under their belt—but for one reason or another it was Berthod, off the heels of a decade-plus long climbing retirement, who finally completed the route after 39 days of effort. Blumel called this “a fitting way to bring Didier, a guy very connected with Squamish climbing history, back into the story.” Indeed, what struck me in my reporting for this story was how excited everyone was that Berthod was back, and that he had redpointed such a beautiful open project. Mason Earle called it “the best comeback ever.”

Without further ado, here are a few words with Didier Bethod, orbiting around The Crack of Destiny.

The Interview

Climbing: How did you learn about The Crack of Destiny? Was it on your radar for a long time?

Berthod: When I first came back here in March 2022, I was reading through the guidebook with an open mind and saw it in the photo of North Star. “Holy shit,” I thought, and started to inquire around. I asked Ben [Harnden] about it and he told me that he had been up there a little when he did North Star. I really wanted to know whether it was big enough to jam.

I walked up there July 5, 2022. As I rapped down, I was so impressed by the steepness. I thought maybe it would be a vertical crack and thus super, super thin since it hadn’t been done, but I was psyched to give it a go. After one day I immediately knew it was possible.

Climbing: Let’s get into the nuts and bolts.

Berthod: Yes. So, the splitter portion is about 15 meters [50 feet]. It starts with a couple of 0.3s, and then widens up to 0.4s for the middle section. I do think you could climb the whole splitter just placing 0.3s though. It is quite thin. At the end [when the crack traverses and joins North Star, the crux] it thins back to 0.2, but I karate kick into the dihedral to sort of skip jamming that section, which would be much more difficult.

Climbing: How would you break down the route?

Berthod: The first five or six meters is maybe 13b/c, I don’t know. It is 0.3s, no feet, kind of campusing.

Climbing: And really sequential.

Berthod: Yeah, very sequency, very hard. Afterward you have an okay rest where you can chalk. Then the middle section is really sustained: Long moves, few feet. I would also say maybe 13b/c to the setup for the crux: the karate kick. You do two or three setup moves, and then the kick. All of that together, from the setup, doing the kick, and rejoining North Star, is maybe V9 or so. I probably fell 15 or 20 times around there. And these are theoretical “sections” but after the first rest it is really all continuous. And then after the crux you get a bad rest, and then right into the crux of North Star. [Didier and I then paused to argue about the grade of the crux boulder on North Star. I think V8, he thinks V7, and you, dear reader, certainly care about this pissing contest. He finally compromised at “a tough V7.” —Nat]

Last summer, I spent around 10 days rope-soloing the crack, and then 20 more days trying it with a belay. This year, I spent six days going for the pinkpoint, and then three more days to redpoint it. Redpointing it was easier than I thought it would be. I placed the same gear that I pre-placed for the pinkpoint. Maybe 10 pieces?

Climbing: Is it the hardest route you’ve done?

Berthod: I don’t know, I’ve climbed 14c [sport] on limestone in Europe and I don’t know if the Crack of Destiny is 14c. It is so hard to compare cracks with sport routes. But this is definitively the hardest crack I’ve ever climbed. Greenspit, From Switzerland with Love, Learning to Fly, are all warm ups compared to Destiny. It even seems to me that the Cobra is slightly easier, but since I still haven’t sent it, it is tricky to say! What I can tell for certain is that Destiny is harder than 14a. When I sent it, it was burly, Chris Sharma style! It was a fight! I got to the last rest and I was fucked!

More important than the grade, Destiny is to me—by far—the most beautiful crack I have climbed.

Climbing: Any tricks in the process? Velcroing cams, specific tape? Anything like that?

Berthod: No! Nothing. This was actually one of my strategies. I did not enter into any complex parameters. I taped all my fingers. I didn’t velcro anything. I didn’t watch the humidity. No parameters, just keep it simple. No specifics about the tape. I didn’t want to enter that space.

Climbing: Tricks are for kids?

Berthod: [laughs] Tricks are for kids.

Climbing: What changed between this year and last year? Between falling a lot, and then doing it quite fast?

Berthod: Last year I had an elbow injury, so I wasn’t really able to train or even pull really hard on my left arm; I wasn’t in great shape. I trained a lot this winter.

Climbing: What did that look like?

Berthod: [laughs] One-arm pull ups and front levers. That’s it. Maybe two times a week. I was also bouldering outside a lot and climbing in the gym with my family. I went from not even being able to do a one-arm pull up in November, to doing almost four in a row in June, when I sent.

Climbing: Anything you want to highlight about this crack?