Each January we post a farewell tribute to those members of our community lost in the year just past. Some of the people you may have heard of, some not. All are part of our community.

The post A Climber We Lost: Stewart M. Green appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

You can read the full tribute to Climbers We Lost in 2024 here.

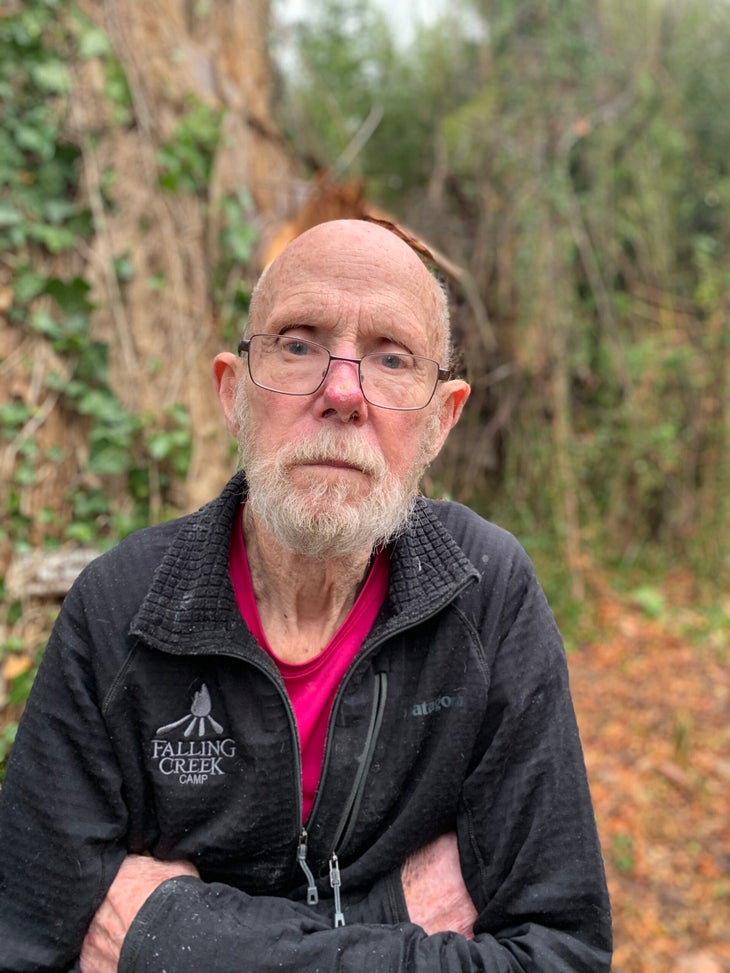

Stewart M. Green, the “Fred Beckey of adventure guides,” embarked on his final adventure on June 4. He was 71.

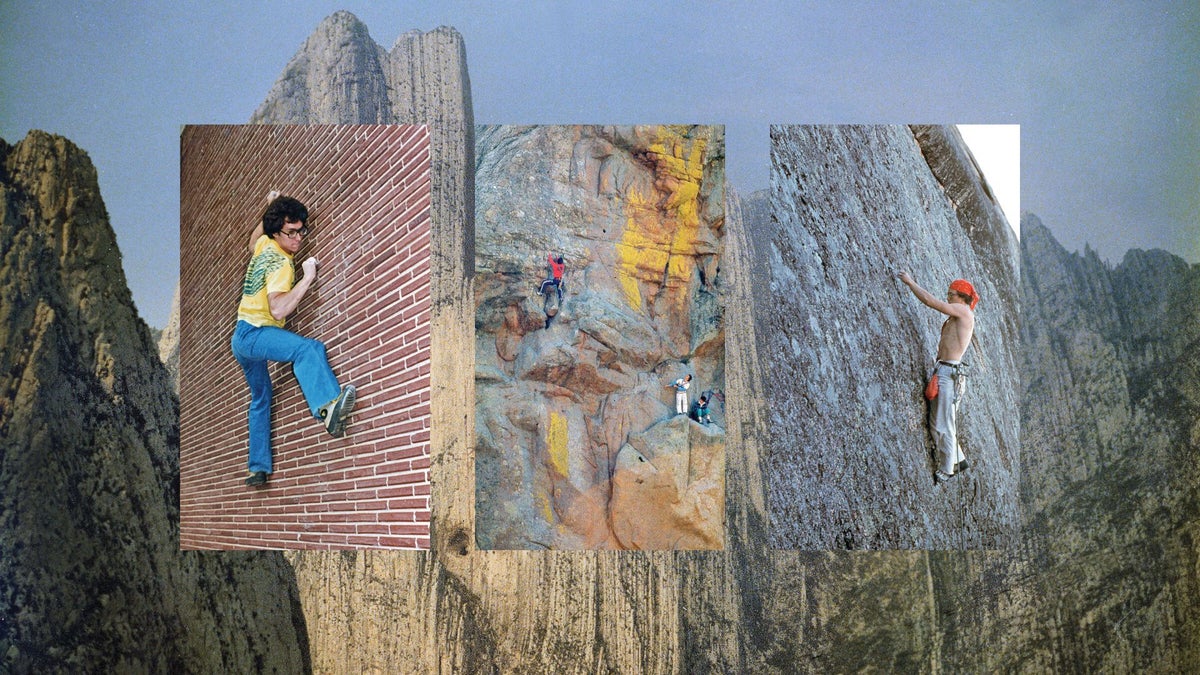

Green provided legions of climbers with routes to climb, but his books and photos will be his enduring legacy. Green penned and photographed some 45 to 70 books (the precise count is unknown). You may have gotten his beta in Rock Climbing Colorado with its 1,800+ routes, or Rock Climb New England, Best Climbs Moab, or Rock Climbing Europe, to cite just a few of his works. You may not be familiar with his Best Easy Day Hikes Phoenix, Best Lake Hikes Colorado, Scenic Driving Arizona or Scenic Driving California’s Pacific Coast—Green wrote and photographed outside the climbing world perhaps even more than he did within it.

A freelance writer and photographer since 1977, Green was steeped in an old-school work ethic and stayed the course. He did much of the research for his books himself, often climbing most of the routes in his guides, especially the ones covering his home turf around Colorado Springs. For his book on the Pacific Coast he drove the route four times and took 20,000 photos. For Scenic Driving Arizona he logged 10,000 miles. His last book, Best Easy Day Hikes Phoenix, was published in September.

“Stewart [had a] dedication to the reader, a need to provide reliable and useful information,” says Max Phelps, Green’s longtime editor at the publishing house Globe Pequot/Falcon Guides. “I was often left marveling at his energy, unwillingness to compromise on the quality of his work, and the many miles of hiking and driving.”

One of Green’s more recent books Hiking Waterfalls Utah, sold out before it was even in shops. “I was looking forward to sharing the news of early success for this book with Stewart,” says Phelps. “For most authors, it would be good for bragging rights, but boasting was not in his nature.”

At tradeshows Stewart’s popularity was evidenced by the long lines to get his signature on his books.

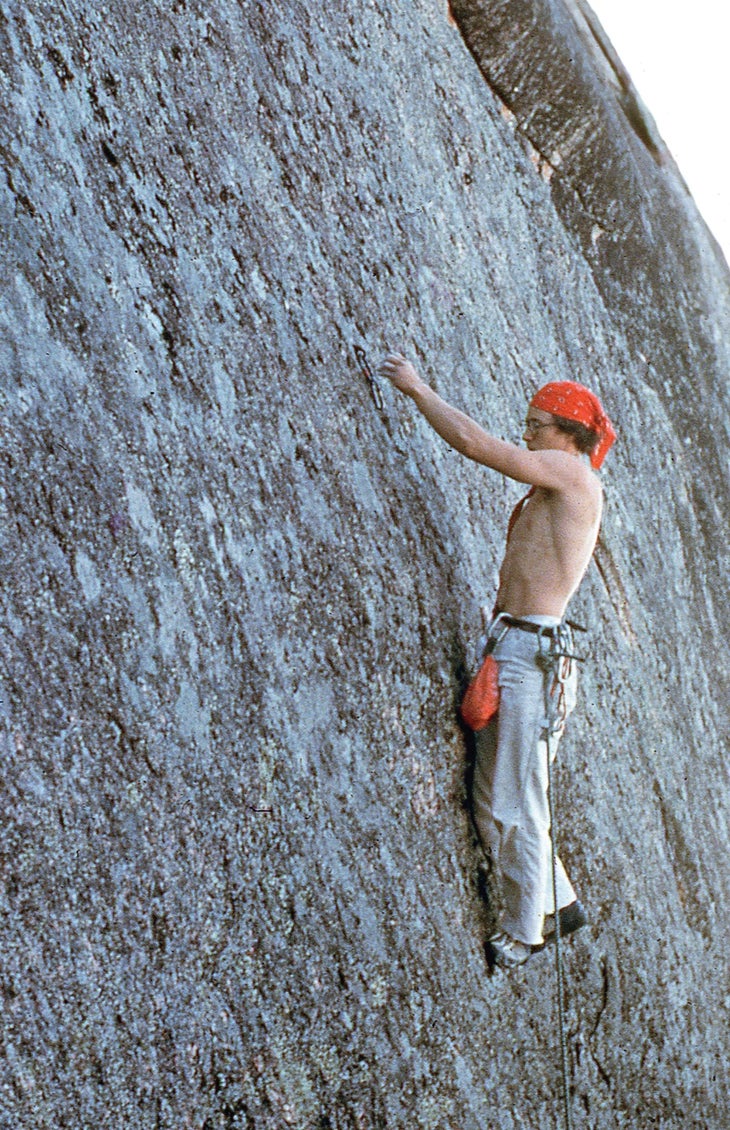

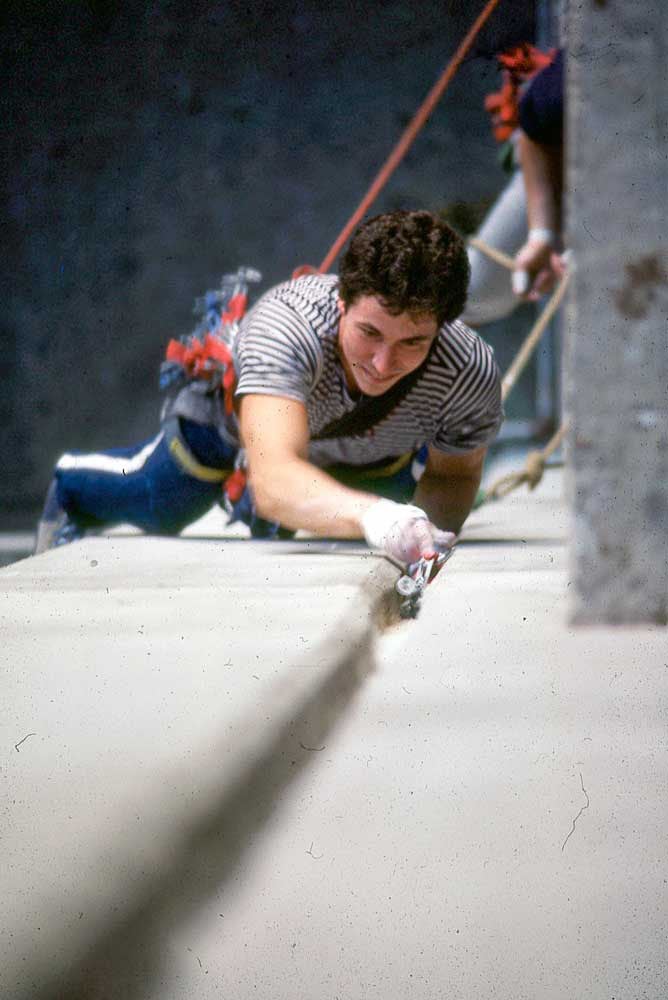

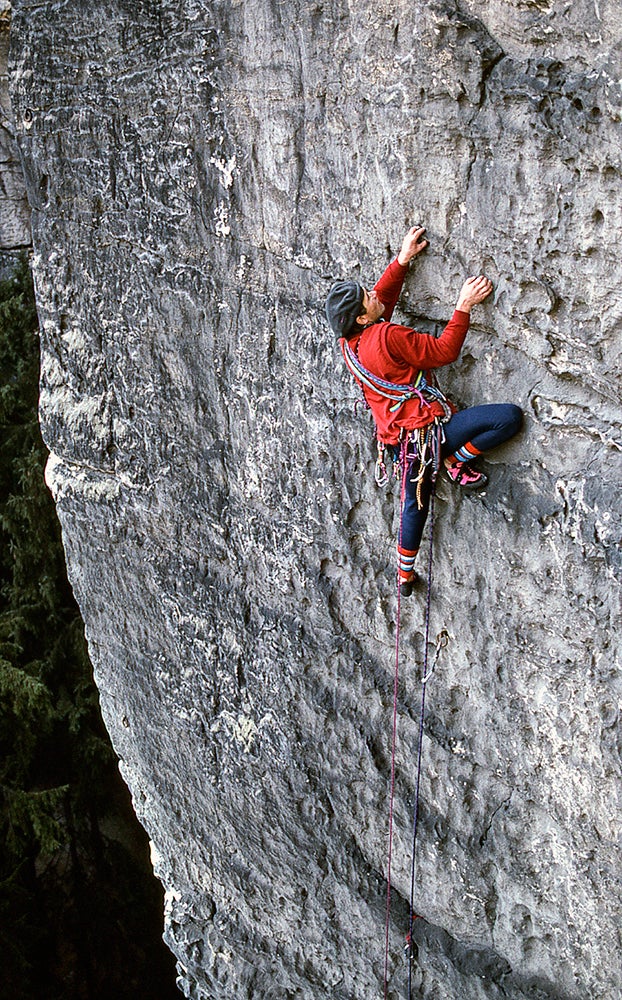

As an editor for Climbing, and then Rock and Ice and Ascent, I kept Green flagged in a Rolodex as a first call for when we needed a desert or mountain landscape or a photo of just about any route, old or new. Looking for a pic of Indian Creek’s Supercrack? Green had it. He was in fact there in 1976 photographing his buddies Ed Webster, Earl Wiggins, and Bryan Becker as they made the first ascent of the iconic route.

“[Green] rode shotgun, documenting climbing because of his love of climbing and photography,” says David Clifford, former Rock and Ice photo editor. “He earned his spot on the front lines of climbing history with his easygoing nature, and his ability to capture it all in a frame that was authentic.”

Green would say that he was a “Street photographer at heart, walking with a camera and grabbing shots as life happens on the avenue of life.”

Stewart Green came of climbing age in the early 1970s, and led a robust and inquisitive life. Unlike most climbers of the ‘70s, Green steered away from brickweed and drink. Also unlike most climbers who only locked on climbing, Green was a Renaissance man. He loved art, history (including that of Captain Jack, who was actually a woman), studied the geology, flora and fauna of the places he visited and happily shared the details. He had a degree in anthropology/archeology and wrote the book Rock Art: The Meanings and Myths Behind Ancient Ruins In the Southwest and Beyond. His homepage photo on Facebook isn’t a climbing pic, but one of a marble fountain in the Piazza Navona, Rome, taken during a nine-day trip to Italy, his first time there, just last February.

Jimmie Dunn met Green in the 1960s and they remained tight. They met bouldering. “He was impressed because I was the only person who could do the problems he could do,” says Dunn. “We called him ‘Stretch’ because when he was young he was so skinny that when he turned sideways you could barely see him.”

Dunn recalls a trip to the desert southwest in 1971 when he, Green, and Billy Westbay made the first ascent of Castleton’s West Face (5.11) the sixth or seventh ascent in total of a tower that today has seen over 80,000 ascents. Earl Wiggins noted that the West Face was “one of the hardest desert climbs of the era.” Green, on his blog, wrote that the “Three of us felt privileged to climb that proud tower and stand alone on its sky-island summit, surrounded by the untrodden red rock desert …”

On that desert excursion the three climbers also made the third ascent of Standing Rock and the fifth ascent of North Six Shooter Peak.

All, however, didn’t go smoothly. On the drive back home to Colorado, Stewart’s 1963 VW bug broke down on the road from Castle Valley to Cisco, Utah, a dirt track that at the time was impassable after even a light rain. “It was September, hot,” says Dunn. “Nobody was around, no cars, just an eagle soaring across the desert.”

Popping the hood, they found that the pulley wheel had broken on the bug’s air-cooled engine. Lacking tools, they used a piton and hammer to get the nut off the pulley, freeing it so they could get a matching part. But from where?

They walked in a beeline across the desert “six or seven miles” to Cisco—a ghost town today— from there they hitchhiked 50 miles to Grand Junction, scored a replacement pulley, and returned to repair Green’s German machine.

Decades rolled on and Green became an elder statesman who was passionate about the future of climbing, access, and the environment. “He talked about why climbers should not be able to do whatever we want in the National Parks,” says Dunn. “He said that if we can do absolutely anything, then anyone can do anything including dirt bikers and paint ballers. He wanted us to go by the rules and not ruin it.”

At the time of his passing Green was working on his memoirs. I hope that someone completes the project for him so we can all read about his adventures. Green was a colorful cat with a quiet charisma, Buddha like, and like The Enlightened One he remained a bit of a mystery.

“He could be elbow to elbow with you as a buddy,” says Henry Barber, “but he’d never tell you that he’d done anything. He was almost embarrassingly humble. If you mentioned anything he’d done he’d get red in the face and shrink back.”

I imagine that Stewart is now out there somewhere, getting up early to capture the morning light, staying for the golden hour of sunset, snapping pics and writing away about the magnificence he’d witnessed. I do look forward to reading his next book, though not anytime too soon, please: Best Climbs, The Galaxy.

Green is survived by his son Ian and daughter Aubrey.

You can read the full tribute to Climbers We Lost in 2024 here.

The post A Climber We Lost: Stewart M. Green appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

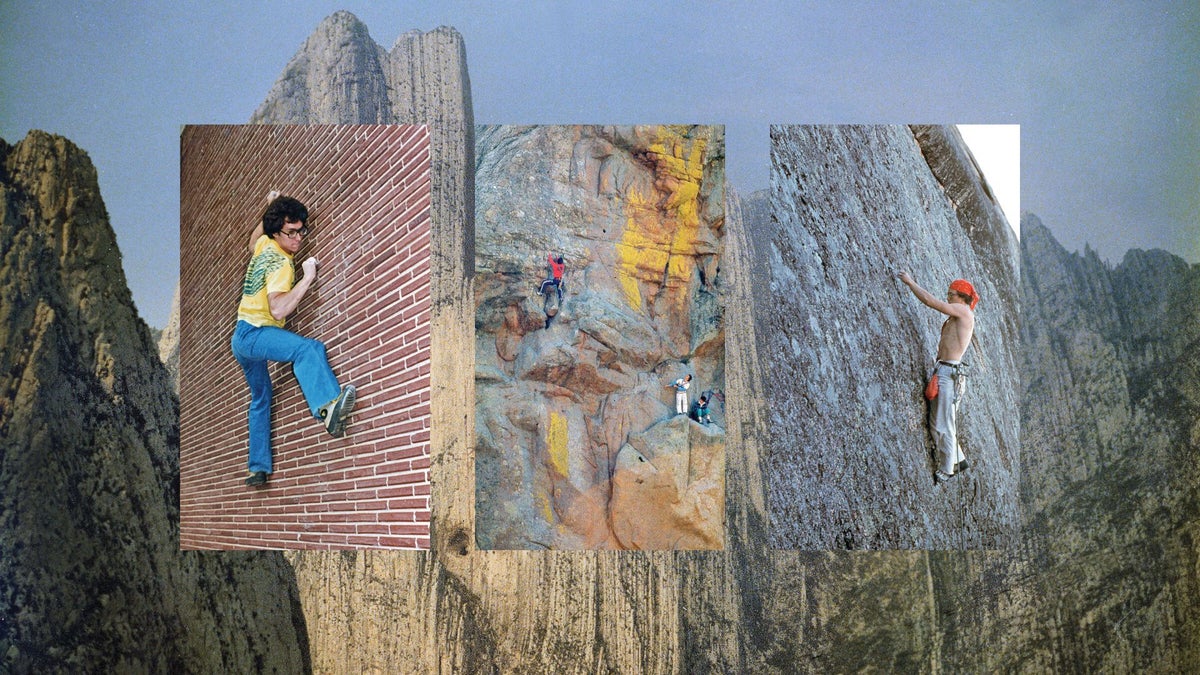

A lifer reflects on risks taken (and fates avoided) thanks to the unexpected friendships forged along the way.

The post How Many Times Can You Cheat Death? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

This story, originally titled “The Learning Curve,” appeared in our 2024 print edition of Ascent. You can buy a copy of the magazine here.

The three-story house blasted out of the limestone cliff had been built by a mad doctor, said someone in our group. “This is where he experimented on people and took drugs,” someone else said. I peered down a hole I imagined was a trapdoor and into the black of a concrete room.

We were there to climb Independencia, a thousand-foot limestone fin adjacent to the doctor’s abandoned home. Independencia is the most prominent wall in Cañón de la Huasteca on the outskirts of Monterrey, Mexico, notably not only because it soars well over 1,000 feet from the desert floor but also because it features a cyclops eye piercing straight through it. You could fly a Cessna through the Cueva de la Virgen, so named because it casts a silhouette resembling the Virgin of Guadalupe, though we never saw it, nor would we witness any miracles.

A few members of the Texas Sierra Club had recently been to Huasteca and had returned with tales of massive limestone walls. Climbing’s coconut telephone spread the word, and that’s how we found ourselves in the good doctor’s lair sometime around 1979.

Our headlamps sliced back and forth in the night, revealing more ruins. Doors and windows were missing, rebar protruded, and broken glass made walking noisy. Some of the windows had bars. Up on the cliffside, their only purpose could have been to keep someone inside. Should we be here? I stuck my head out a window. A draft of cold desert air blew my hair straight up.

“We should probably get out of here,” I said.

“Let’s check out the next room,” said Bill.

I was 18. Bill Thomas was a couple of years older and an artist in Dallas. He was a grown-up to me, worldly. Job. Wife, Vicki. I had yet to graduate from high school, and when I boarded the train in Oklahoma City to meet Bill in Dallas for the drive down to Mexico, I’d yet to have a full glass of beer.

We kicked around in the bunker on the cliff, scaring ourselves with imagined stories of dissections, then scrambled down the backside on an old mule and cut to our dusty campsite in the canyon bottom.

Decades later, I learned that the concrete bunker, built over five years beginning in 1955, had been the refuge of the famed Mexican scientist and physician Dr. Eduardo Aguirre Pequeño. In the 1930s, Dr. Pequeño put himself through medical school by preparing bodies for a morgue. Later, he contributed to the study of mal del pinto, a tropical disease exclusive to the Americas that is similar to syphilis. Part of his contribution included testing inoculations on himself. It is said that when the doctor was injecting himself, you could hear his screams echoing off the canyon walls.

Back in camp, Vicki had fired up a pot of ramen. Vicki didn’t climb, and I don’t think she even liked the idea of it. She was there to soak up Northern Mexico and monitor Bill. She always seemed to worry when he climbed, always telling me to “keep an eye on him,” not let anything happen. Bill would wave that off, and I didn’t really let it absorb into me, either.

Bill dropped an egg in the ramen.

Vicki handed us mugs of noodles. “What did you find up there?” she asked.

“Not much,” said Bill. “Just bones.”

“Really?”

Ignoring Vicki’s worried glance at the cliff we were to climb the next day, Bill pulled the top off a Carta Blanca and took a big drink, foam sticking to his thick mustache.

In the morning, we jammed our packs heavy with gear and ropes and did a loose and sweaty scramble to the base of Independencia’s north face, the steepest and tallest wall as far as we could see. The Sierra Club crew had noted a route somewhere on the face, and we hoped to climb it if we could locate it.

On the approach, we pulled off small holds and larger blocks of brittle limestone, which bounced and broke like jars below us.

“Hey, guys,” yelled a voice from below, “I’m down here.”

Bill and I paused. A few minutes later, a scrawny guy with a patched-up pack, buzz cut, knickers, and a thrift-store shirt pulled up to us.

It was The Roach.

That wasn’t his real name, but he worked for the government and had security clearance and never wanted to be mentioned in any story or have his picture taken. Some climber had coined The Roach’s nickname for his habit of traveling the country and snagging choice FAs out from under the noses of the locals, who weren’t always appreciative.

The Roach was a New Englander, a sergeant in the Army stationed at Fort Sill on the edge of the Wichita Mountains in southern Oklahoma, where I’d learned to climb and where I’d met him after he’d poached one of the best lines at the best crag. The Roach had a souped-up Volkswagen Rabbit that he drove fast, sometimes visiting a distant state over a weekend just to tag it. With a tail-light cutoff switch, CB, radar jammer, and Recaro race car seat, his car was tricked out to evade. With this, The Roach hadn’t thought anything of driving through the night down from Fort Sill to find us. That was fun.

“Yeah,” said The Roach in his shrill Yankee voice. “Heard you guys were here. Figured I’d climb with you, if you don’t mind.”

With The Roach now setting the pace, we quickly arrived at the base of the wall and threaded our way among limestone blocks and plants that either had thorns like barbed wire or spikes like icepicks—the Huasteca Giant agave can infamously grow to six feet across.

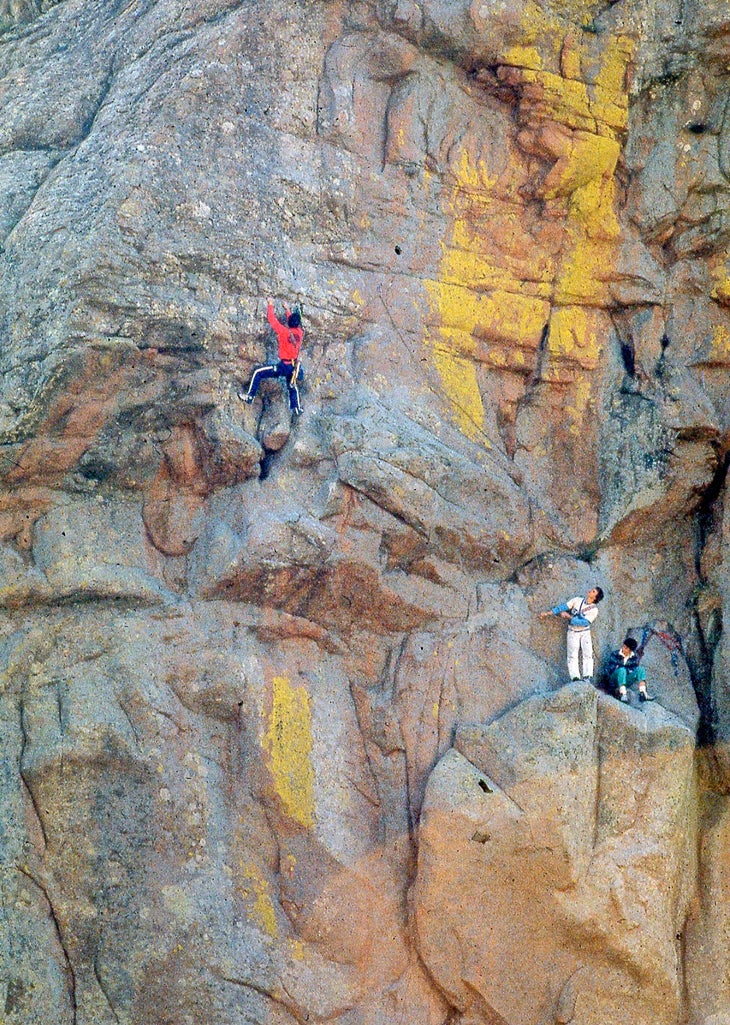

The start of the climb was obvious: rusty bolts and pins resembling an artist’s found-object work. They dotted a line into a fog soup that had settled on the wall. The pins were strap iron twisted sideways on the end and fixed with a clipping ring. The bolts seemed stolen from a mechanic’s junk bin. The gear had indeed been made locally, and the route, first climbed in the late 1960s, was a turning point regionally and even nationally—the dawn of a new age, the beginning of the Huastequismo Golden Era. It was, says Paul Vera, one of Huasteca’s current developers, “the first time a wall of such scale and steepness had been tried, and even the first time a modern dynamic rope had been employed.”

Mexican climbing legend Juan de Dios de Leon Camero had led the difficulties during the pioneering ascent, toiling on the gray limestone weekend after weekend. The group—Carlos Rangel, Adolfo Garcia, and Jose Reyes—descended on Sunday to be back at their blue-collar jobs on Monday. When the workweek was over, or on holidays, they’d return and advance the line, Prusiking frayed fixed ropes or hand-over-handing up electrical cable they’d strung between gear.

As de Leon Camero and team neared the top of the wall, news of a tragedy reached them. Two climbers had been killed in a crevasse on one of Mexico’s big mountains. One of the Independencia climbers would need to attend the funeral and represent the climbing community to pay respects to the families. As team leader, de Leon Camero quit the wall to attend the services. Now just an easy scramble from the summit, the remaining crew pressed on, completing an ascent as revolutionary in Mexico as the first ascent of El Cap was in the United States.

They named their route La Norte Independencia, but de Leon Camero would, says Vera, also christen it La Checoslovaca, after a certain Czech lady climber who had visited during the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City.

Pitches went by uneventfully, with Bill, The Roach, and I yarding on suspect pieces and swinging leads. At times, spicy free moves connected stretches of aid. For the first-ascent team, busting those moves in work boots, with no fixed pro ahead and not knowing what would come next, must have caused a few anxious moments.

Near the midsection, we encountered a stretch of the electrical wire tied between the bolts. Aside from not getting tangled in the wire, one of the greater challenges on the climb was avoiding the agave and yucca bristling from the wall like porcupine quills. A fall was unthinkable—you’d rather close yourself in an iron maiden than slam into one of those plants.

The climbing itself was simple aid, but the north face was the steepest, tallest, and airiest situation I’d been in, and I was relieved when we pulled onto the summit of Pico Independencia and kissed the wooden cross planted in the capstone.

The market in Monterrey the next day smelled of peppers, grease, and engine fumes. We—now including Texans James Crump and John Sanders—shouldered through the crowds around the stalls, and I bought a silver ring with a brown stone in it. Turned out, years later, when the glue failed and the stone fell out, that it was plastic, and the ring wasn’t silver, either.

We hammed it up, posing for photos; I donned a sombrero while a shop owner held a butcher knife to my throat.

Escaping the heat, we ducked into a dim street-side bar that reeked like a men’s room.

Bill and I ordered beers. They came out warm, and when my eyes adjusted I noticed a metal trough at our feet running parallel to and the length of the bar, terminating at a drain.

“Urinal,” said Bill. “Convenient.”

We spent a few more days in Huasteca, kicking around, climbing several easy free routes up long backbones of limestone. I was amazed by the abundance and scale of the rock. Walls and peaks rose as far as you could see, almost all of them unclimbed. If I’d moved there and spent the next 45 years putting up routes every day, you still wouldn’t be able to say the place was developed.

Huasteca Canyon was quiet. Just us and a few vaqueros on horseback, blanket rolls and bags of grain tied to the saddle horns, passing along the dry creek bottom. They never acknowledged us. We never acknowledged them.

We broke camp after about a week and began the 10-hour haul to Dallas. Late at night, I spelled Bill, taking a turn at the helm of his Volkswagen bus. Around midnight on the narrow Texas road, my mind was wandering, when a deer ran onto the highway. I hit the brakes, leaving two stripes of rubber on the road. Our piles of gear flew forward, and then there was a thump.

The deer had caved in the front end of the van.

“What was that?” Bill asked.

“I hit a deer.”

“Is it dead?”

The deer was still alive on the road, lying on its side, chest heaving, soft eyes scared.

“It’s suffering,” I said. “We have to finish it off.”

But how? We didn’t have a gun.

“Use this,” said Bill, handing me a hammer we’d used on the wall.

I aimed at the delicate spot between the deer’s eyes, raised the hammer, then slowly lowered it.

“Can’t do it,” I told Bill.

“You have to.”

“I’ll run over it.”

The van was still drivable, so we got in, and that’s what I did.

It was morning before anyone said a word.

Bill Thomas wasn’t my first climbing partner. Donnie Hunt was.

On Christmas Eve in 1975, when Donnie and I were 15, we rode our bikes 30 miles down I-40 to Red Rock Canyon State Park. Red Rock was the nearest thing we had to a real cliff. The walls there were 50 feet high at best, but it was rock, and a step up from the clay creek banks that we practiced on almost every day after school.

Arriving in Red Rock around noon, we hammered framing nails into seams on one sandstone wall, a checkerboard streaked with blue. As the winter sun began to dip behind the cedars, we clawed over the top, grabbing fistfuls of dirt as holds. An ice storm blew in during the ride home, and by nightfall our bikes were so glazed in ice, the chains wouldn’t turn. We dismounted and walked.

Around 11 p.m. that night, after about 25 miles of slow going, we topped a slight rise where we could see the glow of town up in the clouds.

A highway patrol car pulled alongside us, its red and blue lights turning.

The policeman leaned across to the passenger’s seat and rolled down the window.

“You the Hunt and Raleigh boys? Your folks called. They’re looking for you.”

“Found ’em,” he said into his radio. “Out by Hydro.”

The patrolman drove off, and when we got home, we were both threatened with grounding, but that didn’t stick.

Donnie’s stepdad, Virgil, distributed beef down in the southwestern corner of the state, about an hour and a half away. Part of his route took him to Lawton and the nearby Wichita Mountains, a small upheaval of rugged granite hills, a natural attraction, being the only topographical relief for hundreds of miles. The last Comanche chief, Quanah Parker, and the Apache leader Geronimo are buried there. Coronado and the conquistadors passed by in 1541. Jesse James stashed gold somewhere.

We were too young to drive, but Virgil let us ride along. For us, the Wichitas were an X on the treasure map.

Virgil dropped us off at Mount Scott; at 2,464 feet above sea level, it’s the second-highest peak in the area. “Pick you up here this evening,” he said, then waved and headed south in the station wagon.

We explored Mount Scott’s boulder fields, roping up to cross the larger gaps.

On another trip we found the Narrows, a deep canyon that, from a distance, looks like a stone gate. With us, we carried a copy of a 1974 National Geographic with the article “Climbing Half Dome the Hard Way,” about the first piton-less ascent of Yosemite’s Half Dome by Doug Robinson, Galen Rowell, and Dennis Hennek. The article was our instruction manual, and at the base of a climb, we’d review the pictures. We didn’t always get it right, belaying by wrapping the rope around a gloved hand.

Hiking to the Narrows, we skirted a herd of bison grazing on Indian grass, ditched our camp gear under a tree, and scouted for cliffs. We scraped through woodlands, dense oak and blackjack raking our arms like hay hooks.

West Cache Creek bubbled cold and clear in the Narrows. Sunfish darted after minnows. Golden eagles screamed from the granite cliffs. Donnie and I would swim as much as we’d climb, favoring a cold, dark pool upstream where the canyon pinched down.

Once we were old enough to drive, we’d cut from school on Friday and spend all weekend in the mountains, climbing routes that today would hardly qualify as technical, our sneakers holding us back from making any difficult moves, but the climbs were real to us.

We climbed there for over two years, yet still, we hadn’t seen another climber or even a sign of one: no fixed pins, no bolts, no chalk, no sling around a tree. We figured we were the first and only climbers from there to Colorado until we saw a long-haired guy with a pack and a rope tied to the top. A dark-haired woman followed him, and they hopscotched boulders in the creek.

We observed from the woods, anxious to finally meet another climber.

Donnie and I wore knickers and jackets we’d sewn ourselves. Donnie had even made his pack; he was good about seeing flat pieces of fabric and imagining them into shapes that could do things like hold gear. He was straight A and had long red hair that the girls loved. He married just out of high school, and later, after his kids had grown and left, he went back to school and got a degree in electrical engineering.

When Donnie and I finally stepped out of the trees, Bill gave us the once-over.

“You climb?” he asked.

We roped up with Bill, and again every weekend after that, until Donnie graduated and left small-town Oklahoma, and then it was just Bill and me and Vicki, who by now usually stayed in camp, read paperbacks, and worried about her husband.

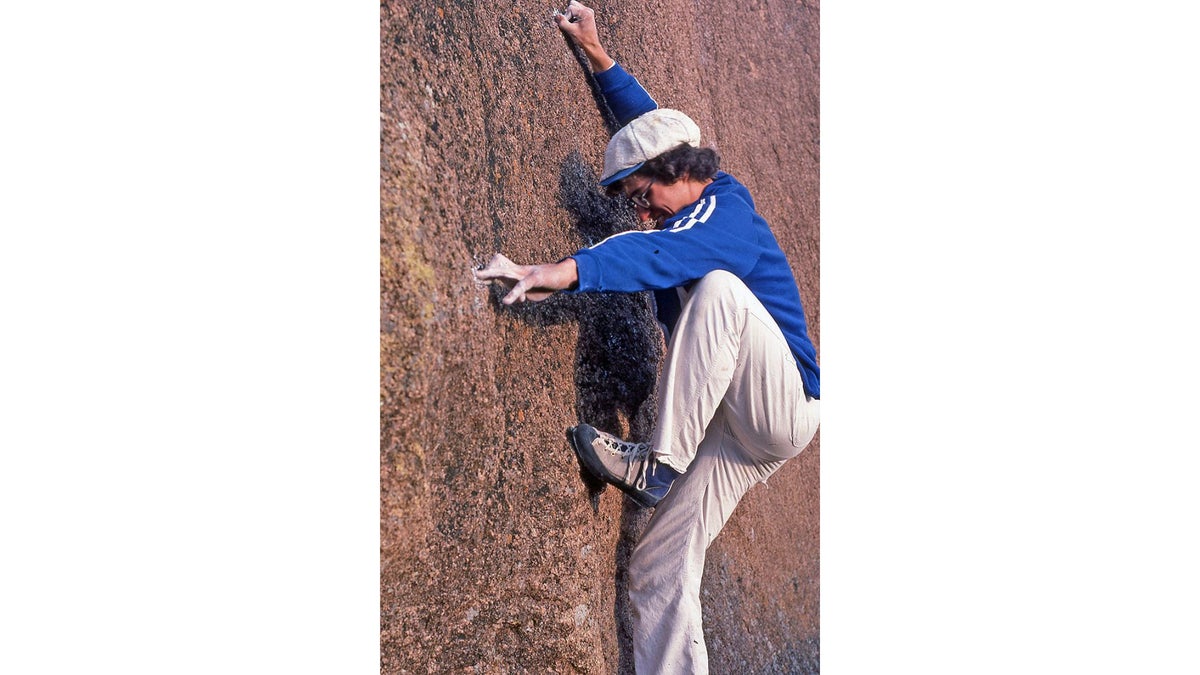

Bill had real gear and had climbed with others in Texas, usually at Enchanted Rock, a granite slab near Austin. His belay device was a marvel to me. He even had rock shoes, and I saved up, spending $50 on a pair of EBs just like his. I treasured those shoes, checking the soles after each outing, examining them for wear, calculating how many more routes they had in them before I’d have to shell out another $50.

The Lichen Wall is 250 feet high and the tallest cliff in the Wichitas. A few routes skirted its edges in the late 1970s, but nothing went up the center, a spoon of gray-green stone with water streaks like war paint.

Bill and I plotted a potential route that rambled up the king line. Two, three pitches? Bill wound webbing around his waist like a cummerbund, making a swami belt, tied in and shouldered a rack of slung nuts and hexes that clanged like cowbells.

Thirty feet up, Bill placed a small nut into a slot, the only pro so far, and climbed past, polishing off the crux moves and getting onto terrain that looked 5.7 or so. Easy for him—still no pro, though.

I fidgeted at the belay in the gravel by the creek and ran calculations—he was now so high that the nut wouldn’t do any good.

Bill’s progression was smooth, and with just 30 easy feet to go to the belay, it looked like he had it in the bag. From there, a series of horizontal overlaps would get us to a large ledge at the end of the second pitch. Above that, we didn’t know. It was too far away to tell much.

The jangling of bells got my attention. I looked up to see Bill rag-dolling down the wall. With rope stretch, he just brushed the ground, then rebounded, hanging from his swami belt, looking like he’d been broken in two.

I lowered him a couple of feet to the ground.

He wasn’t moving, and his eyes were rolled up in his head.

He’s dead.

I’d seen dead people before at funerals but had never touched any, and the thought of it spooked me. I didn’t have any training and didn’t know if I should try CPR or get help.

Another climber I’d recently met, Terry Andrews, was climbing around the corner out of sight with a friend. I ran over for help.

“Bill fell,” I screamed.

“How is he?”

“He’s dead!”

I ran back to Bill to wait for Terry.

When you sit next to a dead person, you feel dread. Dread about what comes next, what you’ll say, what your fate will ultimately be. At my age, though, it was just a flat dread. The other feelings wouldn’t come up until decades later when I’d help carry the body of a friend down from an ice climb and deliver him to his family. There was nothing to say, just the dread that pulled like a new gravity.

Terry came at a sprint. “What happened?” he said, gasping.

“Bill fell from up there.”

“What are we going to do?”

“Don’t know.”

We looked at Bill crumpled on the ground, the rope slack around him.

Then Bill sat up and rubbed his head.

“Sheeett!” he said. “What happened?”

Bill stumbled for words, looking up at the route, then looking down, then up. I still don’t know how he fell. Maybe a foot just slipped. Maybe a hold broke.

Once Bill’s mind cleared and he grasped the situation, he wobbled to his feet. We thought he might collapse, that we’d have to carry him out, but he straightened up and untied from the rope, no doubt considering the consequence that could have been and the one that might yet lie ahead.

“Hey guys,” he said, “don’t tell Vicki.”

On the hike out, Terry told us of a crag not an hour away with beautiful pink stone, just a few routes and loads of potential. “That’s the place to go,” he said.

“Lead the way,” we said and followed his tail lights west toward a promised land.

Baldy Point, also called Quartz Mountain, is an extension of the Wichitas and near its westernmost end, although you wouldn’t know it because they disappear under the farmlands for dozens of miles, then spring back up like warts as you near the town of Altus. From afar, Baldy looks a bit like the Loch Ness monster without the neck. This peak and others nearby may be a part of the Wichitas, but quartz granite is much better, fine-grained and clean as a tombstone—the smaller peaks around it are cut up with monumental quarries.

When Bill and I first pulled up, heavy fog hung over Baldy Point (known to climbers as just “Quartz”), and the stone seemed to reach forever into the sky. I think I actually gasped when I saw it.

Conditions were damp, but Bill and I couldn’t wait and jumped on a recent route—they were all recent, all seven of them. Bourbon Street was the obvious choice, a rusty streak over knobs and shallow potholes to a belay below a gaping offwidth that swallows you and eats your clothes on the second pitch. Greg Schooley and Bernie Wire established this 5.8 in 1978 and nabbed many other gems, notably The Hobbit, Three Bolt, and Pacific Route.

Climbing Bourbon Street was like hearing music for the first time. That climb showed us that seemingly blank faces were possible—as long as you had a hand drill. Quartz had no shortage of blank faces, and Bill had bolts.

The difficulties on Quartz rock are like the weather: If you don’t like it, come back tomorrow. On a cool day, your hands and feet stick anywhere. On a hot day, which was more often, hands and feet hardly stick at all—5.8 doesn’t just feel like 5.10, it becomes 5.10. Wind can also be a factor. Exposed to endless miles of flat wheatfields to the west, the face of Quartz is a giant windscreen taking the brunt of the pressure that builds on the flats down in Mexico and boils across the plains like the pressure wave from a thermonuclear blast. Quartz is the first obstacle in its way. If you are on the wall trying to rappel, your ropes blow straight up, and you can’t get them down.

But we had yet to learn any of that. Many lessons lay ahead, like the one taught on lead, trying to stance in a bolt or wrestling with the mental gyration of whether it’s better to keep climbing with no pro. One time I broke a drill before a hole was finished, and I was actually relieved because the decision just to go up had been made for me.

I didn’t realize it at the time, but on most routes there it’s easy to fall in your head but difficult to fall in practice. Gravity and texture hook onto you. You could pull out all the bolts and remove fear from your mind, and the outcome would be the same as if nothing changed, but it would be dangerous to know that in advance.

I climbed my first 5.9 and 5.10 with Bill at Quartz, learning curves that were more like ramps because they never curved down.

At nights, we’d crowd in a cave formed by semi-sized boulders that had rolled together, leaving a room that was high enough to walk upright in. I imagined that we weren’t the first to hole up here, that the Wichita or Commanche who ruled the grasslands had ducked into the cave during immoderate weather. And years earlier, during the Vietnam War, most likely, someone had spray-painted a peace sign on the back wall of the cave. Farmer Ted Johnson, who owned the crag and the surrounding wheat fields, didn’t know what it was and called it a “turkey track.” I don’t think anyone ever corrected him, but he could have actually been right.

A small gang of climbers soon formed, and evenings became social. We drilled a brass rivet into the cave ceiling to hang a lantern, and we’d stuff the fire ring so full of mesquite the heat would take the wrinkles out of our clothes. When the fire died down, we’d hitch a sling to the rivet and do pull-ups. Beverages were Brown Derby, and we’d puzzle out the pictograms on the insides of the caps that were so stupidly easy we sometimes couldn’t get them.

Once a few bottles had been drained, we’d play the bottle game, where you’d take an empty bottle in each hand, plant your feet, and walk out on your hands until you were fully extended, body parallel to the ground, then set a bottle out as far as you could reach. Whoever got the most distance out on a bottle won. We were competitive, stoking up for a turn. I think some of us even secretly trained at home and then would show up as if we’d never heard of the game: “Now, how do you play this …?”

Honestly, I don’t recall many specifics about the climbing except the time Herndie fell 100 feet and the time James fell 75 feet. (I know I said it was hard to fall on this rock, but there are exceptions.)

I do vividly remember worming through a natural tunnel maybe 100 feet long below the base of the headwall. We’d drop in there at night and belly crawl. One constriction was so tight I’d had to exhale to get through it. I didn’t know it then, but a naturalist from the Oklahoma City Zoo had investigated the tube and said the wall had been worn smooth by the writhing of thousands of rattlesnakes.

Those evenings in the Turkey Track Cave cemented lifelong friends, although I’ve lost touch with most of them.

I saw Bill at Quartz about 15 years ago. He was there with Vicky. They looked exactly like I remembered; hadn’t changed. It was as if we were still in Huasteca. But changes there had been. Bill didn’t climb much now. He was deep into endurance racing his boat down in the Gulf, getting way out there on the water.

“You should come out and crew,” he said. “Could use a hand.”

I thought about it, but Jaws really ruined the water for me.

“Well, maybe,” I said, knowing I’d never do it.

“You should go,” said Vicky, poking me in the ribs. “Bill, all the way out there on the water … You could keep an eye on him.”

To read more from Ascent, visit our table of contents here.

The post How Many Times Can You Cheat Death? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Over the years there's been some really, really terrible climbing gear that surprisingly made it to market.

The post And the Worst Climbing Gear Ever Invented Is… appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

In the interest of transparency, I’ll say that I am not sponsored, and never have been sponsored, but that some gear is sent to me for free, and other gear I purchase. I like most of the gear I use and have used, and almost all of it is great compared to even state-of-the-art equipment of just a decade or two ago. Shoe rubber is better. Ropes are lighter, helmets are no longer big eggshells, carabiners are easier to clip and weigh less. You get the picture. I can’t really single out one thing as the worst piece of climbing gear ever invented, because there have been so many flops, but I have narrowed it to five:

1. Stubai Marwa

This wine-bottle opener was also known as the “coat hanger” ice screw, because it was seemingly fashioned from a twisted coat hanger. The Marwa came in lengths from four to nine inches, and you screwed it into the ice. I used these in the late 1970s and they were so difficult to place and so flimsy that if you attempted to place one, you yourself were screwed. The Marwa was good for two things. In the days before modern ice tools and crampons, you could aid up vertical ice with it—if its bending action didn’t frighten you too much. The upside was the Marwa was so horrendous it spawned attempts to improve it, spawning the birth of today’s awesome tube screws.

2. Forrest Mountaineering Titons

These were bits of aluminum T-stock, basically scrap, with the sides tapered so you could place them (or try to) like large Stoppers or hexes, and had and I imagine still have die-hard supporters. Supposedly, you could cam Titons, but they rattled down the crack every time I tried that. As large passive nuts they were OK and similar to the Chouinard Tube Chock, though heavier. I actually bought a full set of Titons and carried them for several years before figuring out that they didn’t really work. To be fair to Bill Forrest, the rest of his gear was revolutionary or at least borderline so. My first sewn harness and first aluminum-shafted ice tool were Forrest, and he was the first in the climbing world to dispense with riveting and use glue to attach the tool head to the shaft, on his Mjollnir ice tool and Wall Hammer, and to produce a tool with replaceable picks. But the Titon …

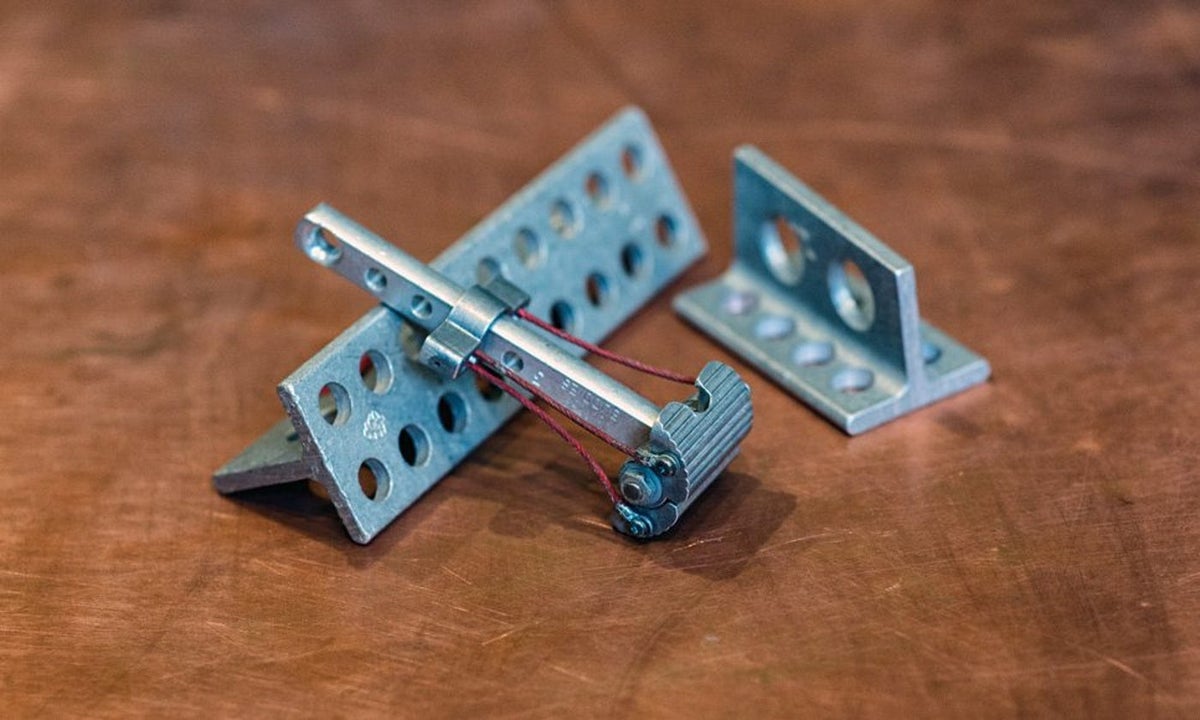

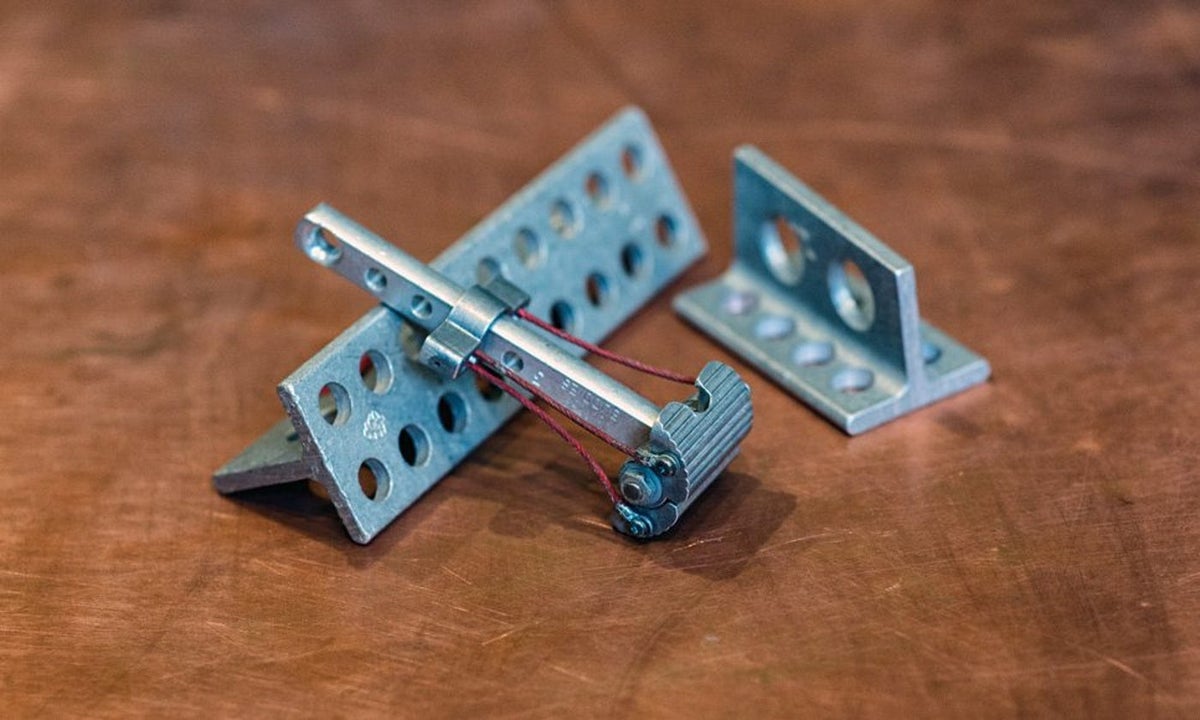

3. Canadian Quest Technology Buddy

I got one of these in Yosemite, out of the back of a car for $10 in 1982. Worst 10 bucks I ever spent. Well, I take that back because I like

having this rare and useless artifact in the Gear Guru Climbing Museum.

The Buddy was an attempt to best the Friend, which was still patent protected at the time, by having a long solid cam on either side of the stem, instead of two much thinner cam lobes that could move independently and adapt to the shape of the placement. On paper that might seem like a bright idea, but in the field the Buddy never fit anywhere except for perfectly parallel-sided cracks. Like the Marwa ice screw, the Buddy did at least get people thinking about other ways to improve upon the camming device, leading to TCUs, flexible stems, double axles and micro and macro units.

4. One Sport Resin Rose

Yikes. Besides being pink and blue, this rock shoe had a tin midsole for support and emerged on the scene in the mid 1980s. You heard that right: TIN. This midsole might have been hacked out of a beer can, but it did let the shoe edge better than the Fire, the leading shoe of the time. Problem was, the sharp piece of tin cut its way through the shoe like a festering thorn, eventually cutting thorugh the seam between the sole and rand. Very likely every pair that was sold was returned: I know that nearly everyone who bought a pair from me (I had a small mail-order business way back then) got their money back … if you didn’t, sorry, the warranty has expired!

Buy them here for 400 Euros (LOL)!

5. Coyote Mountain Works Samson

I didn’t have or use these plastic camming units from the late 1980s because they were yanked from the market before I could buy one. I was keep to buy the Samsom because a composite cam seemed to have advantages over a metal unit. The Samson was lighter, primarily. Unfortunately, the cam couldn’t handle a torquing load and shattered like carnival glass. Still, the idea of using composites in protection was revolutionary, and I suspect that we haven’t seen the

last of its likes.

You might also like:

-

How the Worst Crag Dog Saved My Life

-

13 Great Climbing Films You Might Not Be Familiar With (And 5 of the Worst)

The post And the Worst Climbing Gear Ever Invented Is… appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Our gear expert weighs in.

The post Is it Okay to Wear Socks with Rock Climbing Shoes? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

I have noticed that hardly anyone wears socks in their rock shoes. Hardly is an understatement. Actually, I may be the only climber on Earth who wears socks. To me, socks make sense. Rock shoes, even expensive ones, are uncomfortable and socks add a bit of cushion and a hygienic layer. Am I wrong to wear socks?

—Jesse Dank, Enumsclaw, Washington

The fashion of not wearing socks—or going “commando,” raw doggin’ it, etc.—in rock shoes is actually a recent phenomenon. When I started climbing in 1973, almost everyone wore socks with E.B.s or P.A.s, non-sticky-rubber shoes that were smart accessory footwear to the thumbscrew, but of limited value on rock. When you wore shoes such as these, said to have been cast on a men’s dress-shoe last complete with point, socks provided padding for your tortured dogs.

Yet sometime around 1983, when sticky Fires hit the market, most climbers refused to give up their socks. This might have been because we had been trained to wear them, or we wanted to look like John Bachar, who famously sported calf-high tube socks with his Fires, or because back then everyone climbed long routes and had to carry sneakers and socks anyway for the certain-to-be-really-long descents.

Then, curiously, some climbers began rocking their shoes bareback, and wearing socks branded you as a noob. This holds true even today.

Assuming you are merely a practical person rather than one who falls into the above category, wearing socks, as you noted, does protect your feet from a shoe’s harsh stitching, seam tape, and other interior sharpies. If I were climbing El Cap, or any bit of long stone, or cracks, I’d size my rock shoes slightly larger and wear socks for comfort.

There is, of course, the question of sensitivity. Performance demands a skintight fit, and that demands that the skin of your foot press right against the interior of the shoe. It can be said that going sockless gives you a better “feel” for the holds, that socks dull the sensation, like wearing a raincoat in the shower.

Pshaw. Saying that you can feel the rock through a slab of rubber and a midsole is to confuse “sense” with “feel.” You do develop a sense for how your shoe contacts the rock, how the edge sits on holds, for example, but it is a stretch to believe that you can actually feel the texture and shape of the holds through the shoe sole. This is especially true for board-lasted shoes, which have the feel of wooden clogs (and which I prefer, really).

In most cases, there is no rational reason for not wearing socks. Instead, it all comes back to fashion, and as they say, “fashion changes, style endures.” If you like socks, fly them with pride. Next!

Also Read

The post Is it Okay to Wear Socks with Rock Climbing Shoes? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

It's tempting to fit your shoes too tight, but easy to size them too large. Here's our advice for getting it just right.

The post How Tight Should Your Climbing Shoes Fit? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

One of your most critical climbing decisions is determining how tight your rock climbing shoes should be. Like your belayer, your shoes are your bond to the rock and thus life itself. Get it right and you’ll discover eternal bliss and solid performance. Get it wrong (i.e., fit your shoes too tight), and you’ll burn in a hell of pain relieved only when you replace said shoes with a pair that actually fits.

This begs the question: Just how tight should you fit rock shoes?

Watch long-time Climbing contributor Matt Samet talk through the ideal fit with four pairs of climbing shoes, including lace, Velcro, and slippers

Eons ago, when climbing shoes were constructed to fit like dress shoes complete with pointed toes, you had to size shoes as tight as torture devices to get them to seal around your feet with no wiggle room. After a season or two, those shoes did start to shape themselves to your feet. But breaking in climbing shoes was never an enjoyable process and footwork suffered. As John Bachar once said, “You can’t have good footwork if your feet hurt.”

Bachar and other shoe designers such as Heinz Mariacher played crucial roles in scrapping the shoe shapes of old and building rock shoes shaped more like your feet. Consequently, today’s many hundreds of models are more anatomically correct. Shoes now come in so many shapes that it’s possible for you to get a pair that seems custom-made just for you. But those shoes still need to fit tight.

Choosing the right climbing shoe size

My hunch is that many old-schoolers like me still buy shoes that are too small out of habit. Meanwhile, many climbers could go up a half size without sacrificing performance. I don’t think I’ve ever fallen because of my shoes, but more than once, I have ended a climbing day because my feet hurt.

Related: How to Choose, Fit, and Break In Rock Shoes

Wouldn’t it be nice if we could have a golden rule: Size climbing shoes a size smaller than your street shoes? Unfortunately, that isn’t possible. Different shoe brands use different sizing—a size nine in model X might equate to a size 10 in model Y. Plus, your street shoes might be a bit too large or too small. And which pair of street shoes are we talking about anyway? Then, throw in the complication of width: Are your feet narrow as ninja blades or wide as ping-pong paddles?

How to try on climbing shoes for size

In the absence of a golden rule for identifying your climbing shoe size, you generally must try on climbing shoes to find a perfect fit. Start the process by selecting a pair that is close to your street shoe size. How do those feel? I’ll wager that those shoes are comfortable and too large. Step down half a size and see how that goes. Keep going down until you can barely get your feet in the shoes—this is an indication that a shoe size is too small. Now go back up half a size, then another half size if necessary.

A new pair of rock shoes should feel like a tight pair of driving gloves. It’s okay if they’re a bit uncomfortable. In the context of climbing shoes, the definition of “uncomfortable” is subjective, since comfort and pain thresholds vary. One thing is for sure: If you can walk around in those shoes and not feel any discomfort, then they are too large.

A DIY Shoe Hack: Unbearable Rock-Shoe Pressure? Try This Slice-And-Dice Hack

If you can’t find a size in a certain model that fits, try a model with a different shape. The shoe for you is out there, you just haave to keep trying.

More climbing shoe fit considerations

Bear in mind that all shoes will stretch. Leather shoes stretch more than synthetic pairs. Unlined shoes stretch more than lined ones. Unlined leather rock shoes stretch the most. I’ve had them stretch a full size or more, so I fit these types painfully tight. Unlined leather stretches quickly, so you’ll only need to suffer in the shoes for one or two outings (or wear them at home to stretch them.)

The rand also affects sizing, fit, and stretch. Some rands are tensioned like slingshots to compress your feet. A compressed foot has more power than a relaxed foot, which is why a tight shoe feels more powerful and precise than a looser one. Tightness equals compression. Slingshot randed shoes still stretch, but will rebound when you take them off. They also won’t stretch as much as shoes with more relaxed rands. Thus, rands represent yet another variable to work into the fit equation.

A shoe’s support or lack of support also impacts fit and sizing. You can fit stiff shoes a bit larger than soft slipper-like shoes. That’s because the built-in stiffness—often called “board lasting”—provides support, rather than the shoe squeezing your feet. The softest shoes should fit nearly skin-tight in contrast because they rely on squeezing your feet to deliver support.

The hazards of too-tight climbing shoes

You may be tempted to fit your shoes too tight. Don’t! If you wince when you pull on your shoes, then they are too snug. Pain isn’t the only issue here. Too-tight shoes can cause joint damage to your feet over time. As one example, rock shoes can cause Hallux Rigidus. a form of degenerative arthritis in the big-toe joint. I know this first-hand. I developed Hallux Rigidus about 20 years into my climbing career, yet continued wearing shoes that were too small. Performance mattered more than anything … who cares about problems down the road? Eventually, my toe joints deteriorated to the point where I had to have the joints removed and replaced with synthetic ones. Let’s not let the same happen to your happy feet.

Ultimately, you will probably need at least two pairs of climbing shoes. A comfortable, larger pair you can warm up in and wear to send your dialed lines again and again. You can also wear these comfortable shoes on longer multi-pitch routes. You’ll also want a much tighter, more precise pair for redpoint or flash attempts and bouldering. You’ll only want to wear this tighter pair for shorter periods of time when top performance is your priority.

If my advice seems squishy, it is. I can’t tell you exactly how tight your shoes should be, because I literally can’t walk—or climb—a mile in your shoes. But I can say with certainty that you need to get the sizing right.

The post How Tight Should Your Climbing Shoes Fit? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

The four-pitch line on Looking Glass Rock in western North Carolina is a masterpiece of route finding, knitting together a confusion of “eyebrows”—horizontal pockets that flair in all directions.

The post The Best 5.8 Multipitch I’ve Ever Done appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Twenty feet out from gear. Correction, make that 20 feet above the ground. My hands noodled around inside the slit of an “eyebrow” for anything positive. Finding a slot to gobble up a cam and keep me off the deck would have been even better, but I would have had better luck getting pro inside a fishbowl.

My feet were slipping, and every few seconds I had to paddle them back into place. I chuffed the rubber soles against the rock to warm them, make them stickier—an old trick—but that only made them even slippier.

5.5, I thought. People ride bikes down 5.5, how can this be 5.5?

I looked up at the wall slabbing out and then bending upward where it got steeper. The dark rock and the way it layered with grey reminded me of a hornet’s nest. As far as I could see I couldn’t make out any feature that jived with the route description. Has this route even been climbed?

I lurched to another eyebrow, both hands slapping into it, sliding almost all the way out until latching on a dimple. Whew.

“You sure this is the route?” Michael Levy asked. He was paying rope through a Grigri, but unless he had the magic powers of snake charmer, the belay was only wishful thinking.

“Maybe we should try another way?”

Shakily, I reversed to the ground.

We consulted the Mountain Project route description.

From the end of the approach trail, head a little to the left and look for the pale right-angling ramp on the second pitch, it read.

“I don’t see a ramp, do you?”

“How far is ‘a little?’”

***

You’d create less of a fuss by proclaiming one particular religion superior to all others than you would by saying that one climb is The Best. But The Nose on Looking Glass Rock arguably is the best of its grade and length in the country. Certainly, it is the finest multi-pitch 5.8 I’ve ever done (despite my inauspicious start).

The four-pitch line on Looking Glass Rock in western North Carolina is a masterpiece of route finding, knitting together a confusion of “eyebrows”—horizontal pockets that flair in all directions and often aren’t good in any. The Nose, like the longer route in The Valley for which it was named after, is the rock’s king line with obvious appeal despite the route itself not being especially obvious.

The first ascent was in 1966, by Steve Longenecker, Bob Watts and Robert John Gillespie, natives to the area at the time. Fifty seven years ago no one had yet set foot on the moon. Cell phones, email, social media, and everything else that has us all in the same box were the imaginary stuff of Star Trek.

Flexible, flat-soled kletterschues were available back then for about $9, but Longenecker had heard that Vibram’s deep lug soles gripped better on rock. “We couldn’t imagine climbing in thin-soled shoes,” says Longenecker, “doing so seemed stupid.”

So, shod in high-top Lowa hiking boots, and with fiberglass motorcycle helmets perched atop their heads, the trio started up what promised to be the first technical rock climb on Looking Glass, a route that today sees hundreds of ascents a year and has a line of ticket holders at the base on any fair-weather day.

***

The granite monolith of “The Glass” rises like a bread loaf—or a pirate looking glass if you’ve been drinking—some 500 feet from the Appalachian jungle of rhododendron, oak, mountain laurel, locust, and spruce, in western North Carolina’s Transylvania county, one of this country’s wettest regions boasting enough annual rain to fill a swimming pool six feet deep. The closest town is Bevard, 12 miles southeast, known for its population of white squirrels, said to be the byproducts of escaped circus rodents. Forty miles north at the crossroads of I-26 and I-40 sits Asheville, where Longenecker lives, in the shadow of Mount Mitchell, the highest peak east of the Mississippi, taller even than Mount Katahdin in Maine and Mount Washington in New Hampshire.

When my wife Lisa and I moved to western North Carolina two years ago, I was first surprised that there were mountains, then was surprised by their scale. Not as big as the peaks we left behind in Colorado, but the mountains of North Carolina are still sizeable and the living among them are actually steeper. Biking, hiking or driving you seem to always be going up or down and the mountain roads are so crazy they could have been laid out by one of those space spiders that spins an erratic web in zero gravity. Another difference: while the Rockies are wide open such that you can get 50-mile vistas, in the Appalachia the hills are so tight you might as well be rolled up in a jute rug.

Longenecker and team had previously made several excursions on Looking Glass’s vertical to overhanging north side but, “We weren’t good enough. Didn’t know what we were doing,” he says, “we made it up as we went along.”

Thwarted by the steep rock, they pushed along the base to its slabby west face. “Looking for the easiest way to get from the ground to the top.”

It’s a little over two miles line-of-sight from the Blue Ridge Parkway, a 469 mile stretch of blacktop that rollercoasters along the backbone of the Appalachians, to Looking Glass Rock. With binoculars, Longenecker, Watts and Gillespie got on a Parkway vantage point and scoped Looking Glass, looking for a way up the wall.

When it rained, “We’d watch to see where the rain flowed, and anytime you saw a break we knew that was an overhang,” says Longenecker. “The rain on The Nose went down all the way from the top unbroken, so we knew it didn’t have any overhangs.”

Finally, they buzzed the formation in a small airplane and that settled it—The Nose definitely offered the least resistance of any line they could see.

On December 17, “a stupid time to start, the shortest day of the year was just a few days away,” and with snow on the ground, they started up.

***

Michael Levy and I had heard that even today The Nose can be challenging. Last winter we, both former editors at Rock and Ice, and, later, Climbing, figured that we’d see for ourselves. Over generous pours of wine the evening before we entertained ourselves with how we’d dispatch The Nose, and then knock off several other lines before our Thermos of coffee had time to go cold.

Levy was down from New York City, where he was in a masters in journalism program at NYU, and was currently on assignment for Outside, researching a feature he’d write about the free soloist Austin Howell, who had died in a fall in Lineville Gorge about 100 miles north of Looking Glass.

We got off to a messy start right out of the car. First we walked a hundred yards down a beaten-in trail to have it peeter out at a muddy crossing where footprints said we weren’t the only suckers. Another trail also went nowhere. In an ah-hah moment we located the log steps that mark the start of the real trail just a few feet right of the car. It seems the greenery—this part of the state is a temperate rainforest—hides everything. The tangle can be such that you can’t get a geographical fix on anything. In fact, you can’t see Looking Glass at all until you are standing at its base, and then it comes as a shock emerging from the woods like that, as unexpected as finding a gold coin in your backyard.

Levy and I chugged up the trail anxious to beat the crowds we had imagined would inconvenience us if we weren’t first to tie in.

At the base of the dark rock a stiff wind swept the face and the ground, frozen solid, wore a cloak of ice unnoticeable until you stepped on it.

If we had been vexed by the start of the trail, we were stymied by the start of The Nose.

Lacking any bolts or fixed gear as landmarks, and with any chalk washed off by frequent storms, The Nose could really start anywhere. The rock, the eyebrow features and the angles all look about the same. Finding the correct line on that wall … well you’d have better luck tracking a cloud in the sky.

I cinched down my shoes and headed up where the eyebrows seemed the most promising, meaning the largest and most frequent.

That false start led to another, but we took solace in knowing that we weren’t the first—and won’t be the last—climbers to muddle around on the first pitch, or what we thought was the first pitch of The Nose.

“The guidebook says 5.5,” Longenecker had said during an interview for this article. “Some guys from Alabama, some place where there’s a lot of slots for your hands and feet, they started up that pitch and they said, ‘You can’t climb this, this is not 5.5!’ They’d come all the way from Alabama, made it maybe 30 feet and that was enough for them!”

Michael and I piled the rope and rack on the ground and scrambled over to the North Side to inspect what must be the Astroman of the Southeast, The Glass Menagerie. While the west side of Looking Glass, where you find The Nose, is a slab, the North Face is intimidatingly overhung. The Glass Menagerie is seven vertiginous pitches that top out at 5.13. If The Nose is one of our best 5.8s, then The Glass Menagerie is one of the best 5.13s, at least by the looks of it.

Back at the base of The Nose, the rock now basked in the mid-morning sun. Prime conditions, although we were still the only humans on all of Looking Glass.

***

A weave of vines hung low from the tree canopy, thumping the top of my pickup cab like wooden knuckles as I jounced up wet ruts to Steve Longenecker’s house. Though his white clapboard home is just minutes from Asheville’s groovy downtown—summer nights you can see a musician balancing on a wobbleboard with a monkey dancing on his head—the place felt rural, smothered in trees. At a chokepoint on the driveway a makeshift guardrail of two-by-fours warned of a drop off. A dampness lingered and, autumn now, most leaves were down on the hillside painting it a deep auburn.

“I don’t get many visitors,” said Longenecker, striding over after hearing me pull up. “Don’t like anyone here unless I know. Glad you called, gave me a chance to run the sweeper.”

Outside were two wire boxes about six feet high that looked a lot like shark cages.

“Parrot cages,” said Longenecker.

Inside one was Joplin, a red-tailed hawk; the other housed an Eastern screech owl, Gizzie, both here on a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Special Educational Permit.

We walked downhill along two iron pipe handrails that had been installed when Longenecker injured his knee. Longenecker, thin like a climber and with wireframes that slide down his nose, moved carefully over the slick ground. The 84-year old has been here since 1976, an affirmed bachelor—“I met a few girls that were interesting, but they were taken”—who saw Asheville, a former industrial center bisected by the French Broad River, rise, fall and then rise fairly recently as an arts, music and brew center that some people dub AsheBoulder.

I’d heard that Longenecker slept adjacent to deadly snakes and I can confirm that. About an ape index away from the old sofa he crashes on in the living room were three copperheads and a timber rattlesnake.

“People tell me I should get rid of the snakes, too dangerous.”

Longenecker lifted the screen lid off one cage with Big Kenny (the rattler) and two of the copperheads.

“I have to be careful here,” said Longenecker. “This could be unpleasant for me if I screw up.”

The three snakes twined together, one body, three heads. A real Medusa.

Longenecker’s house was a miasma of animal things, animals, exercise equipment including bicycles, magazines, books on animals and climbing and one titled “How Doctors Think,” and a desktop computer.

Prior to COVID Longenecker, an environmental educator, hauled the snakes around in a pillowcase, introducing them to school children, instructing them about the natural world. When he had birds, he’d take those, too. Before that he was an elementary school science teacher beginning in 1961. Throughout he worked at outdoor camps, where he was introduced to climbing.

During a stint at Camp Mondamin in Western North Carolina in 1964 Longenecker connected with The Two Bobs, Robert Gillespie and Bob Watts, and Bill “Wally” Wallace who taught rappelling.

“We learned how to go down the side of a cliff but had no idea how to climb, belay, put in protection, or find routes,” wrote Longenecker in First Ascent of the Nose.

Eventually, Longenecker found a climbing school in the Tetons where he learned climbing’s fundamentals. Back in North Carolina he and the Bobs practiced holding falls on hip belays. I held a fall on a hip belay once and still have the rope-burn scar across my lower back. Holding falls that way for practice? No thanks.

Before he became a climber, Longenecker was invited on a hike to Rattlesnake Rock, “because I was a snake person. …Wasn’t a climber at that time, I didn’t care a thing about climbing, I was afraid to climb up in a tree.”

The search netting only a garter snake, but Longenecker did get his first look at Looking Glass. He was 19.

Four years later Longenecker ventured to the base of Looking Glass with The Bobs and began their efforts to climb to the top.

When I arrived Longenecker had Honey, a one-year old shelter dog with the speckled markings of an English Pointer, secured in a dog carrier. Now, Longenecker unfastened the cage door. Honey sprang about as if loosed from a bow, paws sliding down my nylon jacket.

“No, no, Honey, down,” said Longenecker. “Tell her No, she shouldn’t jump on you like that.”

Once Honey had supplicated, Longenecker broke a gingersnap in two and put a half on each front paw. Honey didn’t move.

“Ok,” said Longenecker, and Honey chomped down the cookies.

Before the visit was over Longenecker would share a half dozen gingersnaps from a plastic tub, carrots dipped in peanut butter and a chew toy slathered with peanut butter, with Honey.

“Tea?”

Why yes, I prefer tea, I said.

Longenecker boiled water in a blacked aluminum camp pot. He rustled around in the cupboard with doors shingled in curled photos, yellowed newspaper clippings, and postcards and produced a cup for me. He took his tea in a mug with a big chunk broken out of the rim like a missing tooth. We sweetened the tea with a dark local honey so viscous we had to use a spoon to dig it out.

The room was silent as we sipped.

“Gingersnaps?” he asked, offering a plastic tub of them.

Our conversation turned back to The Nose. Did he think back then that the climb would be as popular as it is?

He laughed. “As far as we knew, we were the only human beings out climbing,” he said. And as far as he knew, no other climbers outside their group of three had heard of the ascent at the time, unless they read the local paper which had carried the headline, “9 Grueling hours,” for a report about the ascent, an achievement that no doubt went right over the heads of every reader.

***

On my third go at The Nose, I took a line a bit left where the holds seemed a lighter color, worn down I imagined by all the supposed traffic the route gets.

The climbing there did feel easier, the warmed rock was grippier. I chugged past 20 feet, fiddled in a small offset, and punched upward.

I grew up climbing slabs and learned that smearing requires a faith of a religious magnitude. If you can believe in a God then you can believe your feet will stick to non holds, and the two aren’t mutually exclusive when your last gear feels like a memory.

I was surprised, pleasantly, that the first pitch, while necky compared to sport climbs, has reasonable pro. The corners of some eyebrows pinch down just enough to take solid offset cams. Also surprisingly, since from the ground the eyebrows look like they will swallow large cams, the gear is small, typically under an inch. Climbers familiar with the subtleties of the eyebrows might find holds and gear at will. Neophytes will essentially be driving with eyes closed.

I arrived at the belay about 100 feet up, a stance and two bolts.

Another thing about slabs: when you follow a pitch you wonder why the leader had fussed about so much. What took so long? Michael followed the first pitch, snatching cams from the eyebrows, taking just moments, and arrived keen for P2, the crux according to online sources.

The hardest set of moves on the route is right off the belay that begins the second pitch. This bit of 5.8 is protected by a fixed pin hammered into a slit of an eyebrow. This bit of iron—“not my piton,” said Longenecker, “I’m too cheap to leave anything,” is the leader’s only fixed gear in four pitches. The fixed pin was noted in the route beta, affirming that we were on route, as until then we hadn’t been certain.

The crux is a long reach to a sloping side pull and a high step that feels like you’re trying to put your foot in your own pants’ pocket.

Michael sorted out the moves and took off along an angling ramp.

Longenecker first climbed this stretch in those stiff mountain boots, and the ramp was one of the trickier bits on the route, saying that tiptoeing along it in those boots, his hands palming the rock, was as precarious as carrying a big sheet of window glass.

“That was pretty scary,” he says, “that part means a lot to me.”

When it was my turn I unclipped from the overhead pin, traversed onto a lesser angled but more holdless bit of stone, and ran up it, trusting everything to rubber on rock and momentum, a technique best reserved for toprope.

***

The winter day was waning when Longenecker arrived at the third pitch in 1966. He led off, and was stuck on another high step only to be told from below that “We don’t have all night to do this.”

He hammered in a pin, hooked a pinky through the eye and pulled up, the route’s only point of aid and eliminated when Longenecker returned and reclimbed the route about a year later. After that, he and friends returned and climbed The Nose numerous times, then added the harder line Peregrine (5.9) to the right.

Levy led that third pitch, easier feeling than the second, but it’s probably about the same—after 300 feet of eyebrows you warm up to the peculiar brand of movement.

At the end of the pitch, Levy flopped down onto an expansive ledge, “The Parking Lot,” so named because it is large enough for cars. From here you can walk off left and up, but the route proper goes up a final pitch with a vexing number of eyebrows. It looks intimidating, but you can’t go wrong here. The gear is plentiful and unlike lower on the wall, most of the eyebrows have a flat spot somewhere inside.

Longenecker and The Bobs topped out late day and raced down from the summit on the three mile Looking Glass Trail back down to Headwaters Road where a friend with a VW waited to drive them back to their car. The car was too cramped for the four of them and gear, so they stashed the rope and rack in the bushes.

To their dismay, when they returned for the gear, it was gone. Stolen. “Someone must have been watching us from the bushes,” says Longenecker. “We went to the police, forest service, sheriff. We had pretty much all the rock climbing gear that existed in North Carolina, and it was stolen. The guys who took it had no idea what it was.”

Somehow, the purloined gear did eventually resurface. You can see it for yourself, along with the Goldline rope they used at the Carolina Climbing Museum in Black Dome on Tunnel Road in Asheville.

***

The afternoon was bright when Levy and I topped out The Nose. The humidity that had magnified the cold had even abated and we were comfortable in just short sleeves. A couple of miles out we could discern the cut of the Blue Ridge Parkway. Somewhere along there was the spot where Longenecker and The Bobs had first glassed this rock. Since then, thousands of hands and boots have caressed its holds, an unimaginable scenario in 1966 when you could count all the climbers within a six-hour radius on both hands.

We kicked off our shoes, straightened the rope for the rappels, readied ourselves for the descent.

We had left the house with ambitious plans, but now time had gotten too short to consider more routes. We would have to content ourselves with just this one. Good thing it was one of the best.

Also Read

- The Climbing TikTokers I Can’t Stop Watching

- Two Retired Comp Climbers Pull Off a Rare Free Ascent of ‘the Nose’

- How to Train Everywhere and Anywhere: No Need for Rocks or Gyms or Weights

The post The Best 5.8 Multipitch I’ve Ever Done appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

We grouped up in various vehicles and drove straight from Oklahoma to Yosemite, pulled there by the unseeable promise of a salvation only the rock can lay on you.

The post The Road to Becoming a Yosemite Climber appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

I was riding shotgun with Jon Frank at the wheel heading east past Barstow in 1981. I’d drifted into a slumber from the hot Mojave wind drumming through the open window of the ’71 Volkswagen beetle, when I thought I heard something—a dry grinding, like a coffee mill without beans.

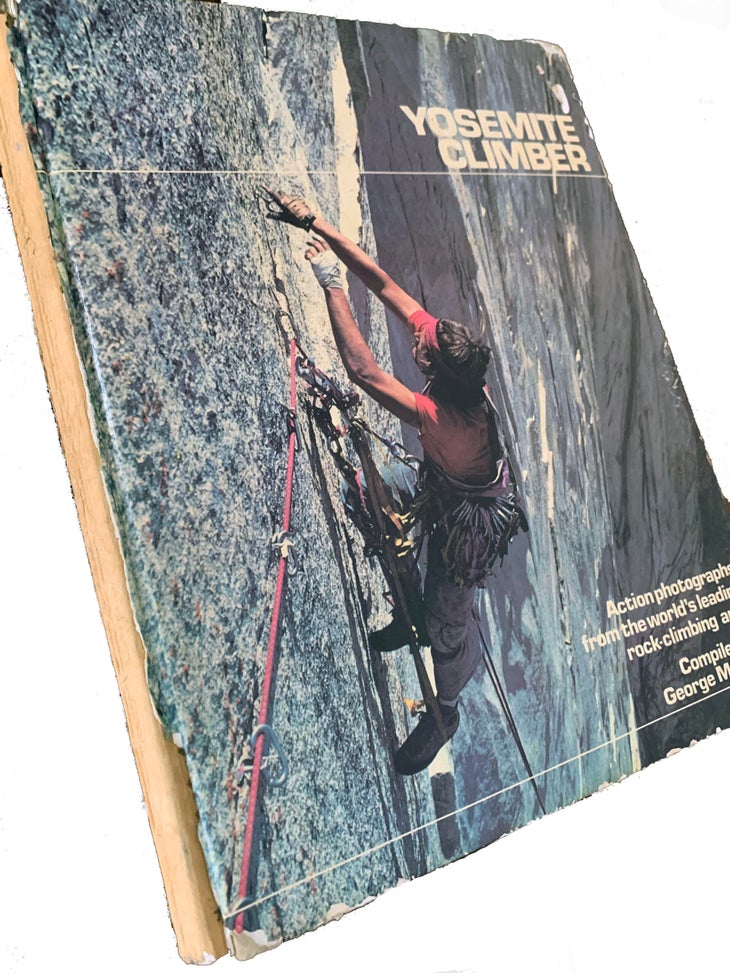

***

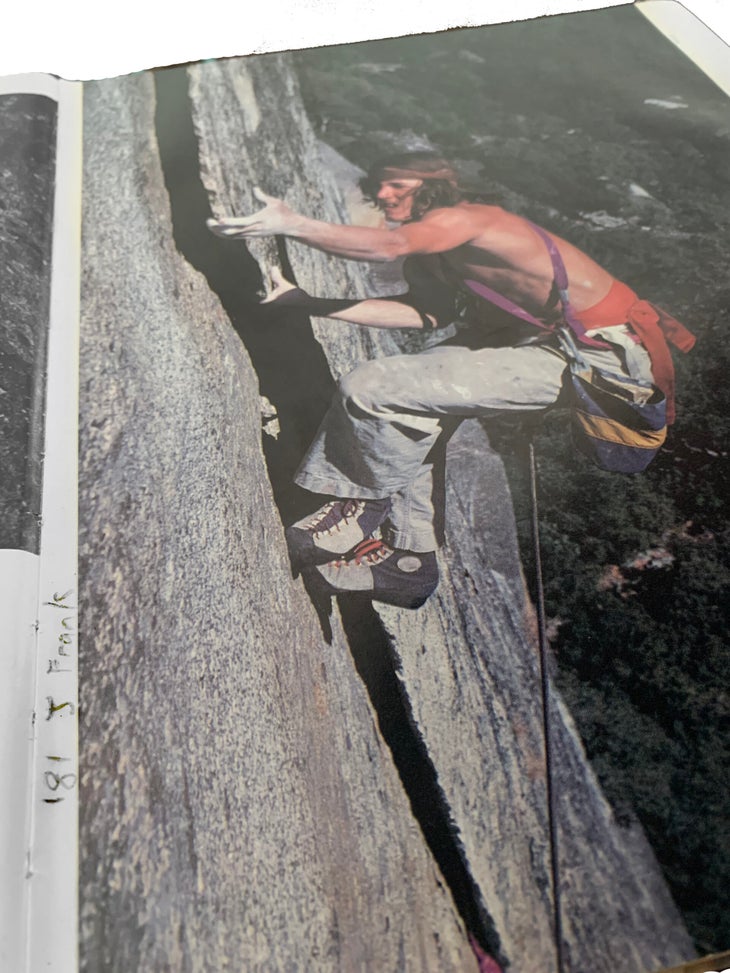

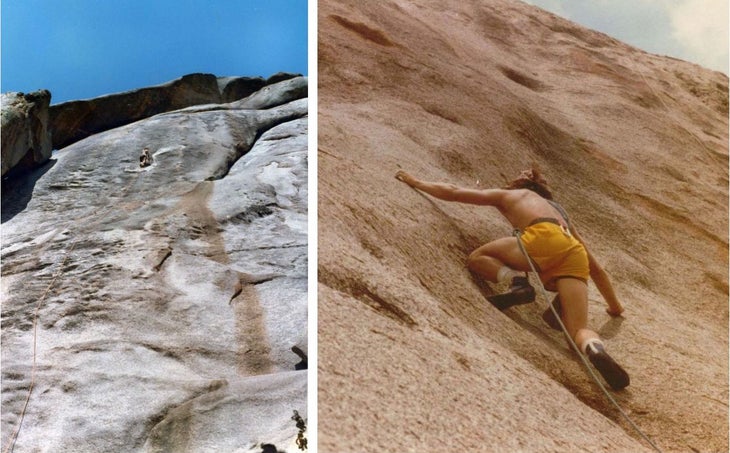

We had summered in the Valley, climbing as many routes as we could get up, gems chronicled in George Meyer’s Yosemite Climber, the book, bible really, that revolutionized climbing photography and even climbing itself. When we first cracked that book open and gazed upon Dave Diegelman suspended under the horizontal roof of Separate Reality, one taped hand wrestled in the crack and the other yarding slack to clip a nut, well that was it. Our small circle of single-minded climbers included Mark Herndon, who would become one of BASE jumping’s early protagonists and who now spends nights staring through lenses at distant stars, and Jimmy Ratzlaff, all 6-foot-2 of him and who would later become a preacher on the Front Range. And Sam Audrain, the coolest of the lot who attracted ladies like filings to a magnet. It was good just to be around him.

We grouped up in various vehicles and drove straight from Oklahoma to Yosemite, pulled there by the unseeable promise of a salvation only the rock can lay on you.

Camp 4, site 23, was a patch of dust and pine needles and with a leaning picnic table decorated with initials and names and years. The site smelled of old camp smoke, sap, and something worse when the breeze across the nearby restrooms was unfavorable. We pitched tent and in the days that followed worked our way through the book. It was a point of pride, or personal growth, when we got in the same positions on the same routes as in Yosemite Climber. Sometimes I’d pause on an especially satisfying move and let the vibes really vibrate in.

In pencil in the book margins I noted what we’d done in case I’d later forget. You could never forget Outer Limits, Wheat Thin, 10.96, Bircheff-Williams, The Good Book … but it would take me a lifetime to realize that.

Back in June, before we’d gone off to Yosemite Jon and I had purchased a car, a red VW beetle. It was already dented and a decade old, but its $250 price tag fit our pocketbook if we split it 50/50.

The bug ran smooth enough, and we had no reason to question its mechanics. We just had to top off the oil and never let the 60 horsepower air-cooled engine get too hot, which meant governing the speed to no more than 55 mph—coincidentally the national speed limit that year. We also needed to take care and keep the rpms to a minimum on the 4-speed. Don’t ever let the tach needle get in the red.

I’ve ridden lawn mowers with more zip than that bug, but it delivered us to Yosemite and puttered us around there, out to the Cookie and back. We were always mindful of the oil and rpms and tried to always park it nosed downhill in case the battery died and we had to roll start it. In August we had to head home and to school. Jon and I planned to drive straight through, day and night, swapping out the wheel while the other of us tried to recuperate. I’ve never ridden in a WWII sub, but I imagine it was a bit like being in that bug: tight, hot, loud, smelled of oil and gas and burning belts.

The trunk in the front of the bug swallowed our bulging haul bags of climbing gear: rigid-stemmed Friends, nuts, several hundred carabiners, enough iron to anchor a small ship, ropes, a portaledge. The back seat was jammed up with camping gear and clothing, canned goods and a couple of jugs of water we’d swig in the summer in a car without any air. If we hadn’t been so skinny there wouldn’t have been enough room for us in the car.

***

The rattle woke me. At first a distant sound I couldn’t understand. Slowly it came into clarity, and I woke from my heat-drunk sleep. I checked our speed. 55, good. No oil light on. Good. Then what?

The noise seemed to come from our car, but maybe it was from outside and was being thrown our way like how a ventriloquist messes with you.

But there was nothing outside but brush and the blazing sun.

I looked again at the instruments. The tach needle was in the red, laying all the way over as if it had fallen and couldn’t get up.

“How long have you been in third gear on I-40?” I asked Jon.

“What, there’s four gears?” he replied.

Jon slid the stick into fourth and the engine calmed like a baby on a bottle.

I pushed my feet against the floorboards to stretch, and was nodding off again when the engine threw a screen of thick smoke down the interstate. All the dash warning lights blinked on. Jon coasted to the shoulder as traffic braked and swerved, blinded by the greasy smoke.

The car was done, that was sure. It wouldn’t turn over, and once the cloud had cleared and the threat of an explosion seemed to pass, we popped the hood. The little German engine looked as if it had gone through a re-entry.

Getting a tow to a repair shop was beyond our means. Between the two of us we’d left the Valley with just enough cash for gas, maybe a bit extra for cold drinks if we got a tailwind to improve mileage.

“What’s next?” we asked each other.

“We’ll have to hitch home.”

We were 1,215 miles from home and the odds of anyone picking us up, two guys with a heap of bags, were slim.

Jon and I took turns thumbing on the shoulder as interstate traffic blasted us with waves of heat and fumes. To improve our odds, the one of us who didn’t have his thumb up hid in the tall weeds—a car is more likely to stop for one than two, especially if those two looked liked they’d escaped from incarceration.

Standing on the asphalt in the Mojave desert in summer was only slightly cooler than walking on coals, but we had food and water for several days and were used to some heat on Yosemite’s glorious walls, plus we were used to Oklahoma’s summer hellscape.

No one stopped for us the first day, and as the sun dipped behind the shimmering horizon we humped our pads and bags about 100 feet from the bug and laid down in a depression, hidden from the road in case a Ted Bundy sort happened by.

No one stopped the second day, either, and as our water ran low—Barstow recorded 110 degrees for three consecutive days, the hottest of the year—our youthful unconcern began to waver.

That evening, as the blacktop popped and cooled, a red convertible pulled up behind our bug. The ride’s top was down revealing a white interior and an even more revealing blonde in a low-cut top, eyes shaded by a pair of large sunglasses. Jon dropped his thumb and dashed over.

Jon is one of the most naturally powerful climbers I’ve known. With an upper body like a front-end loader and sandy blonde hair to his shoulders, he looked like he belonged in SoCal, and in fact that’s where he eventually went.

“I saw you here yesterday,” said the woman, “and I said to myself that if you were still here the next day I’d pick you up.”

Hearing this I rose from the bushes.

“Oh, there’s two of you,” said the blonde. “You boys grab your stuff.”

This is our lucky day, I thought. Absolutely. I gave Jon the thumbs up, and grabbed the straps on our haulbags.

“No thanks, mam,” Jon said practically immediately. “We won’t be needing a ride, we’re good right here. Appreciate it, though.”

Jon was and remains a solid Christian. Getting a ride in these circumstances with an opposite member wasn’t in his Psalms. About a year earlier we had been riding in his land shark cruiser, an old Oldsmobile type with a truck so large Jon slept in it, when Sympathy For The Devil by the Stones began playing on the 8-track. “Please allow me to introduce myself …”

“Noo!” Jon had screamed before ejecting the tape and throwing it out the window.

The situation we were in now was a similar evil.

“You sure about the ride?” asked the woman.

Jon was sure. We settled back into the brush for another night in the hard desert.

Propped up on our haulbags, we gazed at the distant glow of Barstow.

“Imagine,” said Jon, “if we ever do get a ride we can’t just leave the car here, can we?”

“Let’s burn it,” I said. “We’ll strip off the plates and VIN so it can’t be traced to us, then put a rag in the tank and light it.

We had just finished unbolting the plates and popping the VIN off with a knife when a highway patrol stopped. We scurried into the brush. Did he see us? At this point we couldn’t ask for help—how would we explain the missing tag and VIN?

The patrolman put his spotlight on the bug, then his radio cackled and he sped off.

“We can burn it in the morning,” I said to Jon.

The third day was another scorcher, and we again resumed duty trading shifts on the shoulder.

“How long do you think we can do this?”

“Until we become skeletons.”

About 5:30 that evening a pickup stopped.

“You want to sell your VW? I restore old bugs,” said the driver.

When he offered us $150 Jon must have thought an angel had descended. I even almost thought so. The money was just enough for bus tickets home, and we still had wall food so chow wouldn’t be an issue.

“I’ll be back in the morning with the money, and I’ll give you guys a lift to Barstow.”

We hopped in his truck the next morning. In Barstow, we wrestled our haulbags into the belly of a Greyhound, then settled in with the rest of the flotsam for the 30-hour ride home.

The bus station in Weatherford, Oklahoma, was about a mile and a half from my parent’s house. It was even hotter there than in the Mojave, and a stiff wind bent the trees to the north as if to point to more hospitable lands.

I was too beat to carry my bags any distance, and shuffled over to a payphone outside the depot.

I hadn’t talked to my parents in nearly three months, ever since Jon and I pulled out of the driveway in that bug. I’d sent a postcard, something like “Yosemite is great,” but that was the extent of communication and that’s how it was done back then. You left and came back and the middle was just details.

In the 1800s some of my dad’s ancestral clan left Kentucky, going west for new promises. The Kentucky Raleighs never heard from the “went-west Raleighs” again until just a few years ago when my dad looked them up in Breathitt County, Kentucky, a county infamous for blood feuds, and contacted them.

“We thought y’all had been killed by Indians,” they said, “good to hear from you in any case.”

Not that much had changed in the family concerning verbiage when I called home for a ride.

“Hi Mom, can you pick me up, I’m at the bus station here in town.”

“We’re having lunch. I’ll be down once your Dad’s done eating,” said Mom.

“Thanks,” I said, “and can you bring a dime, I had to borrow one for the phone.”

I dragged my bags into the shade, found a spot out of the wind, sat on them, and waited.

Also Read