Becoming an Olympic climber involves submitting your body to intense training loads. And for that training to work, you've got to fuel correctly.

The post What an Olympic Climber Eats in a Day appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

As excitement for Paris builds, we asked some Team USA athletes headed to the Olympics about their diet, including their favorite sending snacks, training day fueling, and—yes—even the worst thing they ever ate before climbing. Their responses include tales of food poisoning, great fueling ideas, and desserts we must now try. But before we dive into what you can learn from the diets of Olympic climbers, meet some of our Olympians.

Piper Kelly: Speed

Shoulder surgery in 2020 didn’t stop Kelly from sending her speed route in 7.52 seconds to score a gold medal at the Pan American Games in Santiago, Chile, in October 2023. She holds a degree in exercise science and has been climbing since she was seven years old.

Natalia Grossman: Combined Boulder & Lead

Climbing since she was six years old, Grossman secured her Olympic ticket by winning gold at the 2023 Pan American Games. She has climbed numerous V13s and is one of the most decorated competition climbers in American history, with ten World Cup wins under her belt

Jesse Grupper: Combined Boulder & Lead

Grupper has ulcerative colitis (a bowel disease), which means that his diet poses challenges beyond the typical elite athlete performance. He has climbed 5.15, is one of the few Americans to flash 5.14c (which he’s done twice), and finished 2nd overall in the 2022 World Cups season. Also an engineer, Grupper has worked designing physical therapy devices for a bioengineering lab out of Harvard University. Like Grossman, Grupper won his Olympic ticket at the Pan American Games, where he took gold in men’s Boulder & Lead.

Samuel Watson: Speed

Just 18 years old, Watson is the youngest climber on the U.S. Olympic Team. In Edinburgh, in 2022, he became the youngest person to take gold at an IFSC World Cup. Another product of Pan American Games, Watson’s personal best time in competition is 4.79 seconds.

Emma Hunt: Speed

A 21-year-old Georgia native, Hunt set the U.S. women’s Speed record—6.301 seconds—at the IFSC World Cup in Salt Lake City this past April. She has medaled in six World Cups, took second place in the 2022 World Cup season, and won the 2022 World Games in Birmingham.

-

Not seeing everyone? Check out the full Team USA climbing roster here.

What is your training day food schedule like?

Sports nutritionists currently recommend that, in addition to getting adequate calories throughout the day, athletes should aim to take in simple carbs during active training and then follow their training with a mixed meal with protein, carbs, and fat. These athletes have their routines dialed.

Kelly starts her day with either oatmeal with protein powder or eggs with rice and veggies. During training she fuels with carbs and quick sugars. Around 2 p.m., after training, she has lunch “with an emphasis on protein so I can recover.” Dinner happens around 7:30, after her second training session, “Where I again emphasize protein and vegetables.”

Grupper generally opts for two eggs and avocado toast for breakfast. This is a nice choice, providing protein, vegetables, healthful fats, and fiber for steady energy levels. His snacks of choice include granola, banana and peanut butter, or a protein bar. The granola and banana provide carbs for quick energy, and the protein bar can contribute to a feeling of fullness—all of which are helpful for long training sessions. For lunch, Grupper likes grain bowls with vegetables and tofu, plus a protein shake. For dinner: “I love making pad Thai, curries, and fried rice,” he says.

Hunt doesn’t have a specific training food schedule, but she preps breakfast the day before because she’s “not a morning person.” “My current go-to breakfast is overnight oats with Gnarly Whey Protein, fruit, and sometimes dark chocolate chips,” she says. “I try to eat within an hour of going to the gym so I’ll be full for my whole training session.”

Props to Hunt: skipping breakfast is a common fueling mistake. During the rest of the day, Hunt opts for “super easy meals, like chicken tacos! Then I try to eat as soon as possible after a training session for recovery; this is usually dinner—a balance of protein and my favorite veggies and carbs.”

Do you have any favorite training snacks?

An ideal training snack includes simple, easily-digested carbohydrates, such as a white bagel, gummies, or pretzels. Simple carbs enable the fuel to get metabolized quickly to provide immediate energy to the working muscles; they also tend to be easier on the stomach when climbing. You’ll notice these climbers adopt this practice in their own snack choices.

Kelly’s favorite training snack is GoGo squeeZ Speedy Strawberry applesauce (“perfectly named for speed climbers!” she says). As a bonus, these are easy to eat without greasing up your hands and contain natural sugars for quick energy.

Grossman opts for bananas, apples, or Nature Valley granola bars. Grupper is similar, “I love homemade granola, a protein bar, and bananas.”

Watson, however, is team fruit. He recommends dates: “They are one of nature’s true candies,” he says, “and they’re a fast way to raise my energy levels.” Hunt is also a fruit fan—she loves strawberries—but she supplements with Pop Tarts and Rice Krispie Treats, both of which are “a great way to bring up my blood sugar if it is getting low.”

Water, electrolyte drinks, or energy drinks? When and why?

Kelly and Grossman are both energy drink users. “I am a big fan of caffeine,” Kelly says, “so I always have a Reign Energy Drink before my morning training session. Not the healthiest option maybe, but we all have our vices!” She also uses water and a hydration mix. Grossman, who’s sponsored by Red Bull, opts to save the energy drinks for comp day.

Hunt says, “I drink water throughout the day. And I love drinking Powerade! I feel way more hydrated when I drink it, and it’s good for electrolytes. I drink it during training sessions and always look for it when traveling.” Hunt is onto something, as electrolytes need replenishment during and after intense training sessions; they can also help counteract travel dehydration from the dry air and the pressurized cabins in airplanes.

Grupper drinks mostly water but adds electrolyte tablets on hot summer training days. Watson also prefers water.

How do you factor timing into your eating schedule?

“I really like to eat a larger meal two hours before I climb,” says Grupper, “and if I’m doing multiple hard rounds in a day, having something filling like a protein bar or a banana and peanut butter an hour out from the round is important for me. I also like having a small snack about 30 minutes before a hard indoor effort or outdoor project.”

Hunt dials her nutrition in by factoring timing into her food schedule. She does this by making sure to eat balanced meals before and after training. “Part of my food schedule is making sure I plan for meal prepping so I always have meals ready to go.”

Are you a vegan, vegetarian, pescatarian, or an omnivore? And why?

Diet patterns are very personal, and each climber has their reasons for following a specific one. Kelly, for instance, says she doesn’t eat red meat, but she does eat white meat such as chicken and turkey. She likes these leaner sources of protein, since she follows a somewhat low-fat diet. Grossman, meanwhile, has been a pescatarian for about 10 years. And Grupper has a specific diet due to his ulcerative colitis, which informs what he can comfortably eat.

“Having the condition has pushed me to follow a gluten and dairy free diet,” he says, “and also avoid fried food. For environmental reasons I also follow a mostly pescatarian diet. Needless to say, finding a restaurant on the road can be a bit of a challenge.”

While Kelly, Grupper, and Grossman’s approaches to diet are restrictive, these diets can still be conducive to high performance and health so long as the athletes make sure to get ample calories and nutrients.

Watson and Hunt, meanwhile, are omnivores, which is healthy due to the wide variety of food available to them. More food options usually results in increased nutrient intake. “I love cooking and the different options that come along with being an omnivore!” Watson said.

“I like meat,” agreed Hunt “My pre-comp dinner is a burger from Five Guys! It’s the perfect size and tastes so good!”

If your stomach can tolerate it, a burger can be a good night-before choice because it offers protein, fat, and carbohydrate. Mixed meals like this tend to digest more slowly, giving a steady energy source for an hours-long competition. Adding in some quickly digesting simple carbs closer to climb time can help fuel a solid climbing performance.

What is the worst thing you ever ate before climbing? And… what happened?

Hunt identifies a mistake I see over and over as a sports dietitian: Just because salads are a healthful food choice doesn’t mean they will translate well into fueling for a climbing session. “When I was a youth competitor, a group of us decided to eat a super basic salad for our pre-comp meal,” she said. “We thought that salads were healthy and we wanted to feel good and healthy before we climbed. As you can imagine, it was not our best competition. We didn’t have enough proper fuel for good fast laps. This comp landed salads on the permanent ‘not for comps’ meal list.”

Milkshakes were a bad idea back when Grupper did not yet know he had a bowel disease. “Before I was dairy free,” he said, “I used to have a large milkshake after a full day of climbing outside. The ride home was not a fun experience for anyone else in the car.”

What food item do you always have with you when traveling to comps?

Kelly always has applesauce when traveling to competitions, though another favorite is Uncrustables. Grossman always brings gummy bears. Grupper carries chocolate, bananas, and Cheerios. (“You have to have your comfort food!” he says)

Watson prefers dates, fig bars, energy bites, and other simple carbs. “A shaker bottle and some protein powder is also a good option for longer days,” he adds.

Hunt, meanwhile, isn’t taking any chances after her salad experience: “I bring a whole pantry of food with me to comps,” she says. “I think it’s why my suitcase is always so heavy. I bring Gnarly Whey Protein, bagels, Zone bars (I love the Fudge Grams), Nature’s Bakery Fig Bars, and Rice Krispie Treats.”

What’s your favorite dessert?

Kelly: “Probably Crumbl Cookies. But you can never go wrong with chocolate and peanut butter.

Grossman: “Ben and Jerry’s with whipped cream.”

Grupper: “Nora Cooks Mug Cake! If you haven’t tried it, you have to! As a backup, anything chocolate usually does the trick.”

Watson: “Chocolate lava cake.”

Hunt: “Chocolate cake and frosting is my favorite! I always look for some after comps, but will settle for almost anything chocolate.”

Author’s Note: While it’s fun to explore what elite athletes eat, copying their diet isn’t always the best plan. Everyone has unique nutrition needs based on a variety of factors. We hope you come away from this article inspired to try new things and find out what works for you.

Marisa Michael, MSc, RDN, CSSD Marisa Michael, MSc, RDN, CSSD is a board-certified specialist in sports dietetics and author of Nutrition for Climbers: Fuel for the Send. She serves on the USA Climbing medical committee and has a private practice in Portland, Oregon. Find her online at nutritionforclimbers.com or on Instagram @realnutritiondietitian for nutrition coaching, workshops, and writing services.

The post What an Olympic Climber Eats in a Day appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Alcohol and climbing have a long history. A nutritionist dives into the pros and cons of crag drinks.

The post Do Climbing and Alcohol Mix? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Let’s play a game: Think of a beverage that goes well with climbing. Three, two, one … Let me guess, was it beer? From climbing’s countercultural roots, in which alcohol seemed to be a staple on walls and as an après celebration, to today’s scene with climbing gyms serving high-end beers on tap, it’s hard to separate drinking and climbing. In fact, according to Climbing’s 2018 reader survey, 43 percent of the magazine’s readers choose a cold beer as a post-climb drink.

However, as driven, health-conscious outdoor athletes, we also wonder, Is alcohol hurting my performance? There’s a lot to wade through here: nutritional and recovery implications; the safety considerations of climbing while drinking; the social/cultural aspects of drinking; and of course, the darker side—alcohol-use disorder (aka alcoholism). Let’s explore.

Nutrition and Recovery

If you’re serious about training gains, alcohol probably won’t help. In fact, there’s evidence that it can be harmful in more ways than one, including:

- Inhibiting recovery

- Decreasing reaction time

- Decreasing peak power the day after consumption (by delaying muscle repair and inhibiting coordination)

- Impairing cognitive function

- Increasing injury risk (due to impaired motor skills and decreased strength)

- Decreasing performance

- Interfering with glycogen restoration (glycogen is the storage form of sugar in your muscles and liver—the fuel that powers muscle contractions and helps keep blood sugar stable)

- Inhibiting sleep

- Increasing urine production/dehydration

- Interfering with protein synthesis (rebuilding and repairing muscle tissue)

- Speeding up digestion (can contribute to bowel issues like diarrhea)

- Providing extra calories (leading to weight gain)

- Decreasing thermoregulation (by way of reducing core temperature and increasing skin evaporation—both of which decrease workload ability)

- Decreasing blood sugar—may lead to hypoglycemia

- Decreasing testosterone production (males)

Taken as a whole, this list sounds pretty bad—and it certainly doesn’t synch up with climbing your hardest. Says Bill Ramsey, longtime 5.14 climber and a professor of philosophy at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, “Alcohol undermines your recovery, it dehydrates you, it diminishes strength gains from training, it fills you with empty calories …. It is just about the worst thing you can put into your body if you want to get stronger.”

And yet, some climbers seem to do fine with alcohol. Research shows that the effects are likely dose dependent, meaning one or two beers at a given time may not be a problem, but a binge-drinking session probably is, as is chronic overconsumption. It’s all a matter of degree.

The pro climber Paige Claassen drinks a glass or two of wine at night, and says, “I’ve never noticed an effect on my sleep, performance, recovery, or mental stamina.” One study in the journal Nutrients (2010) found that alcohol consumption at 0.5 grams per kilogram of bodyweight did not impact athletic recovery. For context, a standard drink in the United States contains 14 grams of alcohol (found in a typical 12-ounce beer). A person weighing 72.7 kilograms (160 pounds) would be able to handle 36 grams of alcohol, or about 2.5 beers, and, in theory, still enjoy adequate recovery from training. This finding is confirmed by a 2021 review in the International Journal of Sports Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism: Small to moderate amounts of alcohol seem to have little effect on muscle performance and recovery.

From a nutritional lens, your choice to consume alcohol may depend on various factors. If having one or two post-climb adult beverages would make the day perfect—as Claassen says, “It’s like a mini-celebration with my husband or friends to reflect on the day’s successes, efforts, and struggles”—go for it. On the flip side, it’s not recommended to consume alcohol the day before a big climb or comp. In fact, according to Zack DiCristino, medical manager for USA Climbing, the organization prohibits alcohol consumption for their comp climbers within 48 hours of and during a competition.

Safety + Climbing

Alcohol can inhibit critical-thinking skills, as well as gross and fine motor skills and reaction time. Our sport requires a sharp mind to place solid pro and anchors, tie knots, do safety checks, and climb efficiently. Specifically, alcohol affects the cerebellum, the part of the brain crucial for balance, spatial sensory perception, problem-solving, and skilled motor tasks—climbing, in a nutshell. Thus that “nerve-calming” nip of whiskey or beer before a scary lead can do more harm than good. Not only is your ability to climb hampered, but you’re less safe.

Says John Long, who recently wrote about his experience with alcohol-use disorder on Climbing.com (“Stonemaster John Long Comes Clean on Alcoholism”), “There’s no sport more unforgiving on safety errors. It’s not like you’re shooting baskets.” Long adds that even when he was struggling with alcohol, he did not drink while climbing. Recalling his time serving on rescue teams, Long says climbers should ask themselves, “Do I want to join the conga line of corpses of climbing accidents that happen often enough even when people are sober?”

Jonathan Horey, MD, board-certified in addiction medicine and psychiatry, is similarly blunt on the subject: “We know alcohol affects eye and muscle coordination. Any amount of alcohol will influence your brain. Reaction time and cognition are affected. Your ability to process information is slowed, as is the amount of information you can process.” (Um, what was that beta again? Did I tie that knot?) Horey adds that the way alcohol affects individuals varies based on genetics, weight, time since your last meal, and gender.

In short, it’s never a good idea to drink and climb.

Alcohol as a Social Lubricant

Enjoying food and drink is a beautiful part of life, but it’s possible to skip booze and still enjoy the meal and the company.

Alex Honnold, of Free Solo fame, has never had alcohol but says he still manages to party all night when the situation calls for it—as on his world travels. He thinks the emphasis on alcohol as a social lubricant is overblown. “I have plenty of friends who are occasionally wrecked from a big evening of drinking, and I certainly don’t envy them,” he says. “I’d guess that consistently not drinking … doesn’t make a huge difference in life, but it probably helps eke out that extra few percent at the top.”

Long’s opinion mirrors Honnold’s: “People who are trying to push the bar on climbing performance don’t drink alcohol. The two don’t mix. If you’re a weekend warrior or climbing for fun, you may be able to get away with drinking after climbing, but those who are climbing hard don’t drink.”

Jonathan Siegrist, a pro climber who has sent 5.15, skips alcohol when recovery is important, as during intense training periods. “But on a trip—especially in Europe or Asia—I have a drink every night or so,” he says. “Part of the experience of doing things like that is to drink the wine and eat the cheese—or drink the Bijou and eat the noodles if in China—and so I don’t want to look back at my life and think that all I experienced was rock.”

Nonalcoholic beverages

Like the taste of beer or the ritual of having a beer with friends, but not the hangover? Nonalcoholic (aka “near”) beer may be a good option. Keep in mind, however, that some brands still have trace amounts of alcohol—avoid these products if you’re a nursing mom, in recovery, or a comp climber subject to anti-doping testing.

As for beer’s touted health benefits, near beer may contain some polyphenols—which can act as antioxidants and help decrease the risk of chronic disease—plus have anti-inflammatory properties. And some studies (weirdly) show decreased risk of respiratory infection with regular near-beer consumption. Nonalcoholic beer can also be a decent re-hydration beverage, especially with added sodium, which is found in some brands marketed toward athletes. But beer is not the only food that contains polyphenols and anti-inflammatory compounds. You can also obtain these via a healthful diet of fruits and vegetables, nuts and seeds, whole grains, legumes, and omega-3 fats.

Alcohol-Use Disorder

If drinking for fun or for the social aspects is really just drinking to mask alcohol-use disorder, then you’re in trouble. The common “climb + beer” set on repeat may be a harmful pattern, especially if you’re using climbing’s countercultural roots to justify it. It’s a thin line.

How do you know if your drinking is a problem? Both binge drinking on weekends (defined as five or more drinks within two hours for men, and four for women) and regular drinking (more than seven drinks throughout a week) pose increased risk for alcohol-use disorder, which can have severe negative impacts on your health and relationships. Meanwhile, feeling desperate and living in extremes—as Long did during his worst years—is a sign of alcohol-use disorder. There’s an even darker side yet: Alcohol abuse is linked to increased sexual assault—as per the website alcohol.org, 69 percent of sexual-assault events involve alcohol use by the perpetrator, and 43 percent involve alcohol use by the victim. So stay safe in the wilderness by keeping yourself and your climbing partners sober.

Dr. Horey also urges pondering this: “How important is the alcohol to the experience? How much time and energy do you spend on acquiring, consuming, and recovering from alcohol use?” If the balance feels off, reduce your alcohol intake or seek professional help. (Consider organizations like the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation or Alcoholics Anonymous.)

So, should you have the beer? It depends. Take stock of your climbing goals, relationship with alcohol, immediate training plans, and social situation. As Ramsey says, “The trick is to try to find a balance. Some people do it easily and others not so easily. I (and other people I know) have completely cut out alcohol to send a hard project, and it definitely helped. But much of the time, I still enjoy a beer or two at the end of a climbing or training day.”

Marisa Michael, MSc, RDN, CSSD, is a board-certified specialist in sports dietetics and author of Nutrition for Climbers: Fuel for the Send. She has a private practice in Portland, Oregon. Find her online at nutritionforclimbers

.com or on Instagram @realnutritiondietitian.

Read this: Stonemaster John Long Comes Clean on Alcoholism

The post Do Climbing and Alcohol Mix? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

82% of adolescent climbers under-ate their target calorie needs, and 86% under-ate their target carbohydrate needs. This has a cost on both health and athletic performance.

The post Yes, You Should Count Calories… To Make Sure You’re Getting Enough appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

It seems undefinable, yet present. Harm disguised as virtue. A looming problem that is not yet solved—or is it even a problem? Under-eating among climbers is championed and admired, yet current research shows climbers do not eat enough to support health and training. And in my own research in adolescent climbers in 2019, 82% of climbers under-ate their target calorie needs, and 86% under-ate their target carbohydrate needs.

Researchers also looked at climbers’ dietary intake, risk for low energy availability (basically not eating enough to match their body’s needs) and risk for eating disorders. According to Monedero et al. (2022) these researchers found that 88% of their participants had suboptimal dietary intake and 8% were at high risk for disordered eating. Still another study by Sas-Nowosielski’s research team in 2019 found climbers were under-eating both calories and carbohydrates, and were dissatisfied with their body mass.

How did we get here? Why do some climbers fall into the abyss of diet restriction and eating disorders? Because those high-gravity days can really do a number on your psyche. Couple that with seeing lithe, toned bodies at the crag, and elite climbers displaying both prowess and abs in competition can make one think, “I must weigh too much to be a good climber.” And we have proof that this mentality is real.

We have anecdotal data such as Kai Lightner, Caroline Wickes, and Angie Payne, Emily Harrington, and Andrea Szekely sharing their experiences with disordered eating. The documentary Light portrays climbers that have struggled with this mental illness.

We also have scientific data. In one study presented at the International Rock Climbing Research Association in 2018 in Chamonix, France, researcher Gina Blundt-Gonzalez and her team asked climbers to rate if they agreed with statements like, “My climbing performance would improve if I lost weight,” “My climbing performance would improve if I lost body fat,” and “I try to decrease my body weight and body fat to improve climbing performance.” Most climbers agreed to strongly agreed with these statements. Preoccupation with body and diet increases eating disorder risk.

Also Read: Why Underfueling Will Lead To Underperforming

This year researcher Mattias Strand combed Reddit and nine other climbing online forums for conversations about eating disorders. Three themes emerged: Yes, eating disorders are a problem, no they are not a problem, and eating disorders are a thing of the past. Others debated whether losing weight will really help performance, while still more questioned the health of competitive climbers that appear as “living skeletons,” and other similar language. Clearly, many climbers have thoughts about body weight, eating disorders, and performance.

How many climbers actually suffer from eating disorders? In my adolescent study, thankfully only 1 subject out of 22 was at high risk. Still, nearly 5% seems like too many, given the devastating nature of eating disorders. In a study conducted by Dr. Lanae Joubert in 2020 she found that 9% of climbers were at high risk for disordered eating. That number increased the more elite the climbers were. Forty-three percent of female elite climbers were at high risk for disordered eating.

Also Read: Should You Lose Weight To Climb Better?

In a 2022 study headed by Dr. Lanae Joubert, our research team surveyed IFSC licensed female climbers and asked about their menstrual status and eating disorder risk. Twenty-five percent had some sort of irregularity with their menstrual cycles, suggesting that they may not be eating enough to maintain normal menstruation. Fifty-nine percent of these females had a body mass index of less than 20 (healthy is considered 18.5-24.9) , suggesting a trend toward irregular menstruation with lower body weight. While looking at BMI on an individual level isn’t usually helpful, it is useful when examining trends within groups. Some also reported menstrual disturbances when they increased training volume or decreased food intake. And 26% reported having had or were currently experiencing disordered eating.

Reading between the lines suggests: You may be thin, but it may cost your health. Let’s recap:

- Many climbers do not eat enough

- Some climbers are striving for thinness

- Some are at high risk for eating disorder

Taken together, it seems safe to say that we should still acknowledge that eating disorders are a concern, whether within the climbing community or elsewhere. Eating disorders can cause serious and sometimes permanent health problems. Some signs and symptoms of under-eating and disordered eating include:

- Skipping meals when others are eating

- Eliminating foods or food groups until allowed food choices are progressively narrowed

- Not eating with others

- Weight changes (loss or gain)

- Going to the bathroom after meals

- Feeling preoccupied with food thoughts

- Tracking, weighing, measuring food

- Inflexibility in food choices outside of the home, such as traveling or going to a restaurant

- Fatigue

- Decreased training gains

- Frequent illness or injury

- Lost or irregular menstruation

- Mood changes (irritability, anxiety, depression)

- Lightheadedness or dizziness

- Foggy mind; inability to concentration

- Feeling out of control around food or addicted to food

How Much Should Your Eat?

Eat enough! Climbers can burn anywhere from 300 to 600+ calories per hour. More strenuous climbing, such as backcountry adventures with a long approach can use many times this. Be sure to eat enough to cover your basal metabolic rate, plus exercise expenditure and day-to-day activities. For many climbers this is much more than the “standard” 2,000 calories per day.

One way to know how many calories you need is to use metabolic equivalents (METs) to calculate your energy expenditure during climbing.

One MET of energy expenditure = 1 kcal/kg/hour. General rock climbing is 8 METS. For a 160 pounds person (73 kg), you plug it into an equation: Weight in kilograms x METs x hours exercises.

Also Read: Science Says Quit Worrying About How Often You Eat.

73 kg x 8 kcal/kg/hour x 1 hour = 584 calories burned for 1 hour of climbing for a 160-pound person. Remember, this only estimates how many calories you used while climbing, not the rest of your daily activities or your basal metabolic rate.

To prevent relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S), you need at least 45 calories per kilogram per day of your fat-free mass, but this calculation requires that you know your body composition, and most climbers likely don’t and won’t go to the trouble to get measured.

What else can we do? Use evidence-based practices. Yes, climbing is a high strength-to-ratio sport. Yes, weight matters. But so does experience, footwork, strength, flexibility, training hours per week, finger strength, and so much more. Research is pretty clear that in climbers within a normal weight range, weight has little to no bearing on climbing performance, estimated at 1.8 to 4% impact. That’s it. Study after study shows that in general, body mass index (BMI), body fat, and body weight do not correlate with climbing ability.

This means to get better at climbing, weight loss should not be the messaging.

We should use neutral language in how we talk about bodies and food choices. “Oh, you like gummy bears for climbing? That’s cool. It must energize you.” Not “Eww, gummy bears are full of processed sugar.” More of, “Can you weight your foot on that chip properly, or get your hip to the wall?” And less, “I bet if you lost five pounds you could send that.”

We can speak up if we see something that causes concern. “I notice that you skip snacks during our three-hour team practice when everyone else is eating. Tell me about that.” “It looks like you are feeling more fatigued than usual. Do you need a break for some fluid and a snack?” “You mentioned that you lost your period. Have you asked your doctor about that?”

Subtle yet simple changes in how we speak about our bodies, our weight, and our climbing ability can mean the difference for those susceptible to developing eating disorders. Especially with our youth climbers who are going through puberty, teaching them to expect and embrace body changes and pivot their technique and training to reflect that, rather than hyper-focusing on body weight changes, will enable us to flip the script for future generations.

Marisa Michael, MSc, RDN, CSSD is a board-certified specialist in sports dietetics and author of Nutrition for Climbers: Fuel for the Send. She serves on the USA Climbing medical committee and has a private practice in Portland, Oregon. Find her online at nutritionforclimbers.com or on Instagram @realnutritiondietitian for nutrition coaching, eating disorder support, workshops, and writing services.

The post Yes, You Should Count Calories… To Make Sure You’re Getting Enough appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Heat, ice, and contrast baths have all been touted as recovery tools. But to what extent (and when) are they effective?

The post When to Ice? When to Heat? When to do Contrast Baths? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

You’re scrolling through Instagram and see a prominent climbing coach climb out of a sauna tent and throw himself into a bath full of frozen water bottles, telling the viewer in voiceover that he adopted the contrast bath technique after listening to a popular podcast. Gah! An Instagram influencer following a podcast influencer! But wait, you think… Should I get a sauna tent?

Hold that Amazon purchase! Because deciding whether to use heat or cold (or both) depends on what your goal is.

Cold therapy

Nothing numbs the pain like a nice ice pack! I couldn’t have gotten through foot surgery without days upon days of icing, and just about every climber I know has iced a sore or injured finger at one point or another. This common practice is backed by research: Cold does have an analgesic effect. It causes vasoconstriction (a constriction of blood vessels), which in turn can clear swelling, creatine kinase (a marker of muscle damage), and other inflammatory substances out of an injured joint, muscle, or extremity.

A long practice of research suggests that submitting tissues to cold therapies—ice packs, ice baths, cryotherapy, etc.—can reduce muscle soreness and swelling, as well as enhance recovery, power, and performance after a hard workout. This is likely due to the analgesic effect of cold therapy. Cold therapies are also useful in lowering core body temperature in very hot weather, which can also lead to improved performance.

So when to use it?

Ice your joints or muscles when you need pain relief or need to perform well on back-to-back hard days, such as multi-day comps or important climbing trips. In short, icing is helpful if you are fatigued or injured and need to make the next session really count.

But icing is not without its drawbacks. While ice baths may help with short term recovery or pain relief, they may not be great for long-term gains. Inflammation is often thought of as a bad thing, but acute inflammation following a hard training day is what signals the body’s tissues to rebuild, repair, and adapt to a new training load. Tamping down inflammation via cold therapy actually blunts a key signaling protein that helps with recovery. This was demonstrated by a well-designed study in which athletes performed an exercise protocol, then drank a protein shake with tracers that showed researchers exactly where the protein molecules ended up in the body. The athletes then placed one leg in an ice bath and the other in a neutral temperature bath. The study found that the leg in the cold bath took up significantly less amino acids from the protein shake—a finding that has matched findings of other, longer-term studies.

For this reason, climbers should probably avoid using cold therapy on a regular basis. Reserve it for when you need acute recovery—such as after an injury—or if you’re going for intense, back-to-back climbing days.

Katie Pajerowski, physical therapist, agrees.“Knowing that ice can potentially blunt protein synthesis signaling,” she told me, “my advice to climbers as far as when and how to use cold therapy depends on the context and their specific problem or injury. For instance, if a climber is in the process of recovering from a finger pulley injury, an important part of this process is progressive strengthening so that the body will lay down new connective tissue and gradually re-build the load tolerance of the injured pulley. In this case, I would not want a climber to use ice after a training or rehab session, because it’s not worth the possible risk of reducing those gains in connective tissue strength. On the flip side, if a climber is managing some finger irritation in a performance context, like a competition, or a redpoint attempt while on a climbing trip, this may be an appropriate situation to use cold therapy to decrease irritation in the short-term.”

Heat therapy

Most research around heat relates to hot baths/saunas for promoting acclimation to hot weather, which these therapies are quite good at doing. If you live in Canada but are headed bouldering in the Virgin Islands for a winter vacation, heat therapy can train your body to tolerate the weather and may help you have a far more productive climbing trip. There’s also research suggesting that these whole-body therapies (saunas/ hot baths) can increase blood flow, increase connective tissue elasticity, improve long-term cardiovascular health and longevity, reduce arterial stiffness, and reduce blood pressure.

Heat packs applied to the surface of the skin don’t penetrate much below the skin, so they will not have any profound whole-body effects; that said, they can have analgesic effects, and they can also increase local range of motion and perceived muscle stiffness, which can be useful if you’re trying to work on your flexibility.

Contrast baths

Contrast baths, in which you submit the body to alternating cold and heat stimuli, is not new, but there is frustratingly little research about its utility for athletes; and the research that does exist is riddled with non-standardized protocols and conflicting outcomes. It seems to be a way to reduce the user’s perception of pain and fatigue—but it’s hard to draw clear conclusions beyond that.

One purported use of contrast therapy is to clear edema, which is localized swelling and fluid. The theory is that alternating cold and heat could make blood vessels alternate between dilation and constriction, thereby “pushing” the fluid out of the swollen area. However, the bathing itself doesn’t perform this action as well as muscle contraction does, which is why climbers should prioritize physical therapy, which is known to play a useful role in acute injury recovery when that recovery involves swelling and edema.

Because of the lack of solid literature about the effects of contrast baths, it’s hard to draw any real science-backed conclusions about whether or not it’s worth your time. Some people swear by it, though. If this is you, great! Contrast bathing may be helpful on some level, and it can also (for the masochists out there) be kind of fun.

Christine Neal, physical therapist at The Climb Clinic, describes it this way: “Contrast bathing has been shown to increase superficial blood flow and skin temperature… using cold, heat, or both are considered ‘passive modalities’ and should be used as only a part of a program to control swelling, as different modalities may have a different effect on each climber.”

So should you use hot therapy, cold therapy, or contrast baths? If you’re looking for quick recovery or pain relief, these are viable options. But using each therapy in a targeted, thoughtful manner that aligns with your goals will give you better outcomes than ordering that sauna tent and dipping in an ice bath daily.

Marisa Michael, MSc, RDN, CSSD is a board-certified specialist in sports dietetics and author of Nutrition for Climbers: Fuel for the Send. She serves on the USA Climbing medical committee and has a private practice in Portland, Oregon. Find her online at nutritionforclimbers.com or on Instagram @realnutritiondietitian for nutrition coaching, workshops, and writing services.

The post When to Ice? When to Heat? When to do Contrast Baths? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Why do some people take Tums for cramps while other people drink pickle juice? And why, in most cases, are bananas utterly unhelpful?

The post Cramps Thwarting the Send? Dehydration Isn’t the Only Possible Culprit. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

You’ve been climbing all day, or it’s hot, or you’re tired, or you’re doing a style of climbing you’re not used to and…. your forearms or hamstrings or biceps start cramping. Some people would advise you to swallow some salt tablets. Some would advise you to eat a banana. The legendary Yosemite speed climber Hans Florine personally prefers Tums—citing the presence of calcium, which is an electrolyte. But the reality is that cramping—a sudden shortening or contraction of your muscles—can be symptomatic of a number of different causes, and your ability to treat or prevent a cramp is largely reliant on your ability to diagnose its root cause, which can vary according to individual body compositions and external circumstances.

By understanding why you’re cramping, you may be able to troubleshoot your cramps and prevent them in the future. Here are some reasons for cramping, based on current research:

Reason #1: Dehydration/electrolyte imbalance

Dehydration is probably the most commonly cited cause of cramps—yet people still get it wrong all the time. I’ve heard of many people who eat bananas for cramping. But that banana won’t save you unless you’re cramping from glycogen depletion (see theory #4). If you’re cramping from dehydration, potassium is the least of your concerns. It’s sodium that needs replacing, because it’s sodium chloride that is lost in the greatest amount in your sweat. Heat increases your risk of cramping because it increases the rate at which we sweat.

The solution: Drink fluids with electrolytes; at least eight ounces per hour.

Reason #2: Altered neuromuscular control

When cramping occurs toward the end of a workout, in active, shortened muscles, it can be the result of nervous system alterations and over-excitation of the alpha motor neurons. I’m pretty sure this is what happened to me when I placed basically my entire body weight on my big toe while in the drop-knee position after climbing hard for hours. My muscles told me, “Hard pass on that one, time to cramp.”

The solution: Understand where your physical limits currently are; slow your pace, decrease your intensity, and train to increase your capacity. If you do start cramping, pause and stretch.

Reason #3: Fatigue

Fatigue causes cramps when we’re deconditioned—i.e. not in shape for the intensity or duraction of the activity we’re engaged in. Lack of sleep can also contribute to this, as can heat and humidity.

The solution: Increase activity-specific conditioning; strength train muscles that cramp often to correct imbalances; get enough sleep; build in recovery days.

Reason #4: Glycogen depletion

Glycogen depletion is another cause of cramping. Glycogen is a storage form of sugar (energy) in your skeletal muscles and liver. As you exercise, glycogen gets broken down and used to fuel muscle contractions and keep blood sugar stable. During long climbing days, glycogen stores can become depleted. If muscles run out of fuel, they may cramp. There’s a growing body of evidence that climbers are in general an under-fueled bunch, at risk for Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S).

The solution: Eat enough from day-to-day to support training and basic body functioning. Fuel regularly throughout your climbing day. Aim for at least 30 grams of carbs per hour during active climbing.

Reason #5: Central nervous system (transient receptor potential receptor agonists)

This type of cramping can happen when your central nervous system gets fatigued. It may be a result of genetic predisposition, underlying medical conditions, a history of prior cramping, or stress. This is the theory behind why mustard, pickle juice, spicy peppers, etc. may help cramping: If the receptors in the mouth get a signal that something strong is being ingested, it may disrupt the nerve signal that is telling the muscle to cramp.

The solution: Bring something spicy or sour, such as a mustard packet or pickle juice shot if you’re prone to cramping often.

Reason #6: Medications, supplements, caffeine

And finally, some medications, supplements, and caffeine may cause cramping. Coffee in the morning, sports gummies with caffeine at the crag, plus a late-afternoon energy drink—that can all add up to far too much caffeine. If you must use caffeine to send, you’re doing it wrong. Food provides energy to working muscles, not caffeine. While caffeine can help with fatigue and alertness, it also alters neuromuscular function, which means that if you are physiologically prone to cramping, caffeine may be exacerbating your cramps. Similarly, medications such as beta agonists (common bronchodilators for asthma treatment) are associated with cramping in some people. If you suspect any of these in your own cramping history, consult with your doctor before making any changes.

How to prevent cramps

Try to identify which risk factors may be playing a role. Then try to alleviate or manage them the best you can. For example, if you cramp when it is comp day or when trying to send a big project, but not during training, it may be because you are stressed, moving faster, or climbing more intensely than usual. Either condition your body to tolerate these factors, or slow your pace to one you can manage.

Identify the underlying cause and address it. Think about the context of the day. Did the cramp occur when you were tired? Not quite in shape? Climbing in a style you’re not used to? Going longer than usual? Did you eat and drink appropriately? Were you overheated? Play detective to troubleshoot what went wrong so you can prevent it next time.

Practice self-care: Cramping is generally brought on by being vulnerable. Lack of sleep, poor strength, poor endurance, inadequate food, and inadequate fluids/electrolytes—all of these things increase your risk of cramping. Inoculate yourself against the wrath of the cramps by having good self-care and training practices.

Note: This is general information only and not nutrition or medical advice. Always speak with your healthcare professional before undergoing any diet or lifestyle change. For more information about cramps, see “An evidence-based review of the pathophysiology, treatment, and preventions of exercise-associated muscle cramps” in the Journal of Athletic Training.

Marisa Michael, MSc, RDN, CSSD is a board-certified specialist in sports dietetics and author of Nutrition for Climbers: Fuel for the Send. She serves on the USA Climbing medical committee and has a private practice in Portland, Oregon. Find her online at nutritionforclimbers.com or on Instagram @realnutritiondietitian for nutrition coaching, workshops, and writing services.

The post Cramps Thwarting the Send? Dehydration Isn’t the Only Possible Culprit. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Feeling tweaks, aches, and pains? Finding it hard to finish your workouts? Believe that more climbing, more hangboarding, more movement is better? You may be experiencing exercise addiction.

The post One Great Way to Ruin Your Climbing Career? Get Addicted to Exercise appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Author’s note: Exercise addiction is a serious health condition. Seek help from a qualified health professional if you suspect exercise addiction. Most eating disorder treatment centers can address exercise addiction.

Climbing usually draws people to the sport because of its unique movement pattern. It’s so fun and satisfying to figure out the beta, be completely focused on a route, and see what your body can do. Exercise addiction—also sometimes called exercise compulsion, exercise dependence, anorexia athletica, and obsessive exercise—steals the pleasure from climbing and twists it into a perverse game of see-how-much-you-can-move.

Sarah Gorman, climber and physical therapist from California, describes her experience with exercise addiction as a collegiate climber: “It became an obsessive detour during a well-intentioned fitness journey. Ultimately, it felt like that dream where you are making the motions of running but not actually moving anywhere—frustrating, demoralizing, unsatisfying. Yet it was so enticing, as though the promise would hold up its end of the bargain: More training and less calories = desired outcome. I wanted to believe it. I really felt the spiral spinning when I realized I started using more exercise as a punishment for eating something that I saw as not appropriate.”

Why we fall into the trap

One of the trickiest elements of exercise addiction for climbers is that, in the early days of that addiction, your climbing may actually improve. This may be due to increased endurance, strength, flexibility, or skills due to increased training. People experiencing exercise addiction often feel a sense of sharpness, euphoria, flow, and strength. This comes from heightened hormones like adrenaline that keep your body functioning in fight or flight mode, even in the face of dysfunctional exercise. Eventually, however, the compulsive movement catches up, and your body begins rebelling against all the excessive stress.

In the short-term, this may make you feel like you’ve hit a plateau or are even losing fitness; you may also feel “flat” or unmotivated, or feel increasingly prone to injury. But in the long-term, exercise addiction can lead to serious health consequences such as poorly-healing injuries, stress fractures, profound fatigue, depression, cardiac irregularities, and even death.

Signs and symptoms of exercise addiction:

- Exercising beyond what you’re told by a coach or trainer (“to get ahead”).

- Exercise takes up a large portion of your life.

- The time you spend thinking about exercise, working out, and recovering from exercise crowds out other aspects of your life (social, family, work, or school).

- Exercise needs to be increasingly longer and/or more intense to feel like you did enough; you often do more than intended.

- Anxiety, guilt, irritability, or shame if you cannot exercise as planned.

- Exercising in abnormal ways (wall sits and planks in your room at night, even though you already worked out, fidgeting to burn more calories, bounding upstairs instead of walking).

- Arbitrary goals drive the exercise (needing to get 20,000 steps, 100 pushups, etc. that are not based on science-driven exercise protocol).

- Exercise is used to avoid life or emotions.

- Exercise is accompanied by irritability, stress, anxiety, fatigue, body aches, poor concentration, sleep disturbances.

- Exercise becomes your identity.

- Exercising despite being injured, sick, tired, burnt out, or impractical for your day’s schedule.

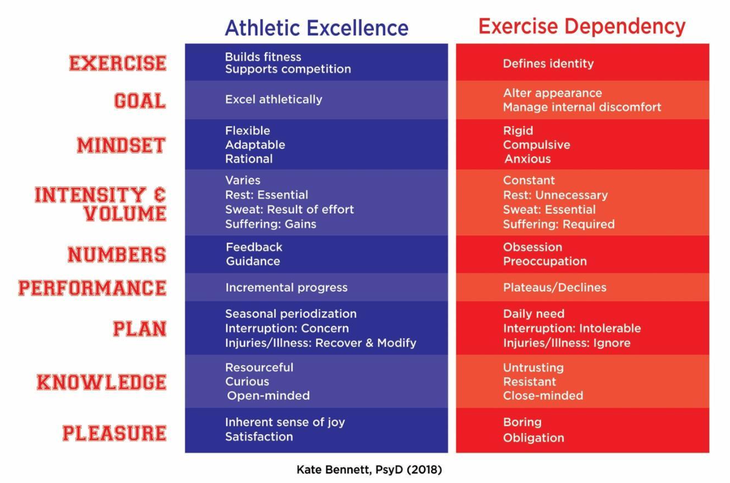

Dr. Kate Bennet, sports psychologist and author of Treating Athletes with Eating Disorders, describes in this graphic how to distinguish between normal exercise and exercise dependency.

How can exercise addiction be harmful?

Exercise addiction can thwart your health by:

- Decreasing bone density

- Impairing heart function

- Compromising connective tissue

- Elevating stress hormones and “fight or flight” mode in your nervous system

- Impairing spatial functioning (coordination, balance)

- Increasing injury risk

- Increasing risk for sleep disturbances

How can we prevent it?

- Do not praise people for doing extra exercise. Especially if you are a coach or parent of a youth climber—if you see them going beyond the prescribed practice regimen, say something.

- Notice if you start to feel anxious around exercise. Is it taking over your life? Does it feel compulsive? Get curious and seek professional help.

- Normalize being human. We all need rest days, even unplanned ones. You are not an exercise robot.

- Honor your body with compassion. If you notice you are feeling run down, sick, or fatigued: rest.

- Do not push yourself through a planned workout if you feel injury tweaks or fatigue. There is a line between being uncomfortable to stimulate fitness gains vs. pushing through and creating injuries and an overtrained body. Be mindful and learn the difference.

What should you do if you suspect exercise addiction?

Exercise addiction is a complex behavior, often intertwined with food relationship, body image, or trauma. The best way to treat these sorts of maladaptive coping mechanisms is to seek professional help. Understanding what is driving the behavior is the first step to overcoming exercise addiction. With a flexible mindset and awareness, you can have a healthy relationship with exercise.

Marisa Michael, MSc, RDN, CSSD is a board-certified specialist in sports dietetics and author of Nutrition for Climbers: Fuel for the Send. She serves on the USA Climbing medical committee and has a private practice in Portland, Oregon. Find her online at nutritionforclimbers.com or on Instagram @realnutritiondietitian for nutrition coaching, workshops, and writing services.

The post One Great Way to Ruin Your Climbing Career? Get Addicted to Exercise appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

You train, buy the best gear, stay stoked and try to give yourself every advantage on the rock or in the gym, but you run out of energy part way through. You aren't eating the right foods.

The post What to Eat to Crush Your Climbing Day appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Joe is working a tricky boulder problem during a comp. He’s already climbed a couple rounds and did well. But now he’s falling on easy moves. He feels weak. He feels shaky. Figuring out the beta seems impossible—his brain just isn’t working right. He’s getting tired.

Joe is experiencing symptoms of low blood sugar because he didn’t eat enough. Some symptoms include:

- Feeling weak, shaky, or dizzy

- Feeling irritable or angry

- Difficulty concentrating

- Fatigue

Is there something Joe could have done to prevent this? Aside from proper training and conditioning, the answer lies in your nutrition.

30-60 Minutes Before you Climb

If you have 30-60 minutes before you climb, eat foods that contain quick-digesting carbohydrates. Foods like:

- 1 oz. pretzels

- 1 white mini-bagel

- 1 piece of fruit—apples, bananas, oranges, etc.

- ¼ c dried fruit

- 8 oz. sports drink

- 2 sheets graham crackers

- 8 oz. chocolate milk

- 1 packet sports gels (like Gu)

- 1 packet sports gummies and chews

Carbohydrates give you quick energy for climbing. They are digested rapidly and taken up into your bloodstream and into your cells.

If you’re less than 60 minutes away from your turn to climb, avoid foods with more than 10 grams of protein, 4 grams of fat, or 5 grams of fiber. Protein, fat, and fiber all slow down digestion. If you eat foods with too much fiber, fat, and protein, the food won’t be digested quickly enough to help you during the climb. You may be left with a heavy stomach and not enough fuel getting to your muscles. I’ve never met anyone who likes to climb on a full stomach!

2 Hours Before You Climb

If you have two to four hours before you climb, your body has some time to digest food. This means you can add a little protein, fat, and fiber, such as:

- Peanut butter and jelly sandwich with chocolate milk or protein shake

- Tuna wrap with cheese and a side of fruit and yogurt

- Oatmeal with milk or almond milk, bananas, and walnuts

- Fruit smoothie and a protein bar

- Trail mix and an apple

- Jerky

- String cheese

- Nut butter pouches

These types of foods give you longer-lasting energy and are slower to digest. Eating them a few hours before you climb will help you start your comp fueled and ready to go.

Have a hydration plan: Hydration can play a key role in climbing performance. Some symptoms of dehydration include:

- Lightheadedness, shakiness, or dizziness

- Difficulty concentrating or confusion

- Dark urine

- Fatigue or lethargy

- Nausea

In general, climbers need about eight ounces of fluid (either water or a sports drink) per hour of climbing. If you are competing in hot or humid weather, you may need more. You’ll need electrolytes if your comp is at a higher altitude than you are used to, it is hot or humid, or you sweat a lot. You can use a sports drink with electrolytes, or electrolyte tabs dissolved in water. Experiment during training to see what works best for you. Remember, nothing new on comp day

The post What to Eat to Crush Your Climbing Day appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

The world's best all-around climber shares his philosophy on diet and nutrition, the stuff that's powered him behind and in front of the scenes.

The post Adam Ondra’s Power Secret? Drink Warm Water. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

I was fortunate to interview Adam Ondra about his diet and philosophy on nutrition for my new book Nutrition for Climbers: Fuel for the Send. Ondra, who climbed 5.14d at age 13, established the world’s first 5.15d, made the first ever flash of a 5.15a, and has climbed over 60 5.15s, is widely considered the world’s best climber of all time. In competitions, Ondra has amassed 21 gold, 10 silver and four bronze medals in World Cups. He also, in 2015, made the second ascent of The Dawn Wall (VI 5.14d) on El Capitan, widely regarded as the most difficult big wall route in the world. In short, whatever Ondra eats must be working—perhaps we can learn from him and up our games, too.

MM: Have you found that nutrition and hydration play an important role in your climbing and training?

Ondra: Yes, definitely. I do feel that the right nutrition helps me to climb harder, most notably in making the recovery much faster. So actually, when I am training, I feel that nutrition is even more important than when I am about to give a performance. Hydration: that’s something that’s pretty obvious—I need to drink a lot and I mostly drink just water. For Chinese medicine, I drink a lot of warm water. It is easier to digest for my constitution and I drink a lot of herbal tea and black tea, especially in the morning.

MM: What do you consider important for your nutrition?

Ondra: I feel it is mostly about the speed of recovery. What is the right nutrition? Of course, there are so many different opinions. I have experimented a lot, and what I feel most important is eating real food. I believe in Chinese medicine. It is something that helps me.

MM: What do you enjoy eating for training and competing?

Ondra: I mean, for training, it’s important to eat real food, and the diet has to be complex, so, more or less eating everything, as long as it’s real food. For breakfast I usually have something warm, so I usually have some oatmeal with some spices, usually cinnamon, that is easier to digest, with some sort of proteins and fat, like seeds and nuts, with maybe honey or some homemade marmalade. And if the training day is going to be hard, I increase the volume of protein by using some vegan protein powder. I use vegan protein because it is the best to digest for my stomach.

In between breakfast and lunch, and in between lunch and dinner, I usually have some really small snacks. Usually consisting of dried fruits, and maybe a little bit of nuts and seeds. Lunch, even if I’m at the crag (which is sometimes complicated), I would cook at home usually some kind of cereal or lentils, or chickpeas with some vegetables. Vegetables, especially in the wintertime, I eat vegetables that are cooked or baked. As for my constitution, it definitely makes me feel better. And for dinner I would usually have some animal protein, mostly fish, with a little bit of cereal such as quinoa or brown rice, and some vegetables again.

And if the training is very hard, right after training I would eat some sort of protein and carbohydrate, so I would have a little bit of protein powder mixed with oats and eating it as fast as possible. So that’s what I do on a regular day.

MM: Do you use any supplements?

Ondra: Yes, I use BCAA [branched chain amino acids] and protein powder, nothing more. All the rest that I am trying to eat is 100% natural.

MM: Is there anything else you would like to share about nutrition and hydration? Do you have any stories about a time where you felt like it really helped? Or if you had poor nutrition and you felt a difference?

Ondra: For example, if I am not really following the instructions for Chinese medicine in winter, I definitely feel much colder. Of course, if I train super hard and I don’t eat very well, I don’t recover—but that’s pretty logical. It’s the whole complex really: if you train hard, you should eat well, you should recover well, you should sleep enough. There are all these kinds of things that help you recover faster, and eating well is one of them. Overall it is something that will help you to feel healthy. But as I said, what is eating well? That is very individual. Everybody has a different point of view. I think, looking at it from the most complex point of view with the most years of experience, and for me that’s traditional Chinese medicine. Hydration is a very important part of Chinese medicine. There are many people that don’t drink enough because they don’t feel thirsty. I drink a lot. I feel it’s most important to drink during the morning, so I always start the day with almost half a liter of warm water before I eat anything. That is a nice start of the day and all of the sudden you feel much better.

Author’s note: Adam Ondra is following individualized nutrition and supplement plans based on his own health needs and preferences. If you are thinking about including any of his tips into your own climbing routine, check with your doctor before adding supplements or changing any part of your diet to make sure it is right for you.

Adam Ondra and Tommy Caldwell Discuss the Dawn Wall and Big Wall Free Climbing

The post Adam Ondra’s Power Secret? Drink Warm Water. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Why optimizing the strength-to-weight ratio through weight loss is bad beta

The post What Studies and Experts Say About Losing Weight to Climb Better appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

My teenage son is belaying me on a route I keep getting stuck on. Desperate for some insight, I shout down, “What next?”

“Up!” he replies.

That’s not what I’m looking for. I want something useful. Likewise, coaches sometimes give bad beta.

A climber asks, “What can I do to get better?” The coach’s reply: “Lose weight.”

Climber weight loss is bad beta

Most climbers think that the simple act of losing weight will help them climb better. But is that bad beta?

A high strength-to-weight ratio is needed in climbing. Many climbers—particularly competitive climbers—try to optimize that by losing weight. Anecdotes of climbers shedding weight or developing eating disorders to climb harder remain ubiquitous.

But optimizing strength-to-weight ratio through weight loss is not so simple. Chelsea Rude, professional climber and founder of She Sends Collective, agrees. “I stand firmly on the fact that climbing, for better or worse, is a sport that crowns those who have better strength-to-weight ratios.” But, Rude adds, “That said, I do not think that losing weight is the magic ingredient to suddenly be able to send your project, break through to the next level, or win that National Championship.”

Climber attitudes toward food

In 2019, researchers asked 605 climbers about their attitude toward eating and food using a questionnaire called the Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26), which measures the risk of eating disorders. This test measures responses to statements like, “I am terrified about being overweight,” and “I feel extremely guilty after eating.” The researchers asked participants if they agreed with, “My climbing performance would improve if I lost body weight,” and “I try to decrease my body weight and body fat to improve my climbing performance.”

Across the board, climbers identified with these statements. The climbers who scored higher on the eating-disorder questionnaire also more often agreed that body fat or body weight significantly impacted climbing ability.

For some individuals, losing weight may prove helpful to performance. Imagine someone who is 50 pounds “overweight.” Would they benefit from shedding a few pounds? The answer is probably yes, as long as they’re also preserving or increasing their strength. But evidence shows us that weight loss through diet is usually not sustainable. Restricting food can also place major stress on a climber’s mental and physical health. With that in mind, climbers are better off focusing on good nutrition, training, experience, skills, and strength.

Climbers should focus on strength, not weight

Given the available research, we have enough data to show that training variables are much more important to climbing ability than weight. This is especially true if you’re already a “normal” weight, with a body mass index (BMI) ranging from about 19-25.

Hayden James, a registered dietitian, recreational climber, and owner of Satiate Nutrition, agrees: “Perhaps weight loss could be performance enhancing to a certain extent for adults in larger bodies, but adult climbers will likely reap the most benefits from a consistent structured training regimen, and nutrition optimization … I’ve heard many comments from climbers sharing their desire to lose weight. More often than not, these comments come from very lean individuals. Body weight likely matters to a certain extent; I speculate that climbing is likely more challenging for those living in larger bodies.”

What about all those climbers who lose weight and say they climb better? Numerous confounding variables may be at play. Was it weight loss specifically that made them climb better? Or was it a higher-quality diet? An intense focus on meaningful training? More kale, less cookies. More sleep, less beer. More training, less Netflix. The weight loss may have been ancillary.

It may be scientifically sound from a strength-to-weight ratio to tell a climber to lose weight. But is it morally and ethically appropriate? The answer depends on the climber’s health history, current weight, climbing ability, and other factors. Of course weight matters, but so do mental and physical health. Some climbers may do very well losing some body fat. With others, weight loss may be contraindicated.

Many studies that take examine anthropometrics—which refers to measurable body characteristics, such as weight, height, BMI, ape index, and body composition—show that climbers tend to be lighter than the general population, and even lighter than other athletes. Elite climbers are often lighter than casual climbers. So, do you have to be thin to be better? Correlation does not equal causation.

A 2018 study backs up the notion that weight loss doesn’t equate to higher performance. The study, which was published in the Brazilian Journal of Kinanthropometry and Human Performance, examined climbers body and fitness levels to see which parameters had the greatest impact on performance. Researchers measured body fat, BMI, ape index, and leg span. They also assessed fitness levels with tests like balance, grip strength, jump height, pullups, and bent-arm hangs. They found that body fat didn’t directly affect climbing performance, particularly at the elite levels. In fact, “ … a large portion of the variance in climbing ability can be attributed to trainable variables.”

More research verifies these findings. A 2015 study published in the Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports found that only about four percent of climbing ability can be attributed to anthropometrics. According to the study’s calculations, body weight and body fat have only a 1.8 percent impact on climbing ability.

The weight loss catch

In all the studies that pinch, prod, and measure climbers, the climbers already clocked in at a “normal” weight and “normal” BMI. The researchers were basically studying climbers who already had good strength-to-weight ratios. They simply found out that if you are already “normal” and you compare yourself to another climber who’s also “normal,” the difference in your climbing ability has to do with training, experience, and strength—not weight.

It’s worth noting that all of these studies were descriptive. This means they take a “snapshot” of climber ability, fitness, and anthropometrics at a certain time period. They did not study them over time or make any sort of intervention. The researchers simply measure climbers, put them through a battery of tests, and report the data. No randomized control trial—the “gold standard” of research—yet exists.

Weight and climbing performance

The climbing community must be careful in recommending weight loss for climbing performance. Adolescents are especially vulnerable to this advice. Coaches may perceive that adolescents are gaining weight or putting on body fat and be tempted to tell them to lose weight. But this can be incredibly harmful and short-sighted. Females gain about 40 pounds over the course of puberty, and often put on fat mass. This is healthy, normal, and appropriate.

Emphasis on weight loss also puts climbers at risk for eating disorders and relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S), also referred to as low energy availability. Consider the sobering side effects of under-fueling your body. These consequences can occur at any weight, even in “overweight” bodies, and include:

- Lost bone mass

- Lost muscle mass

- Decreased cardiovascular capacity

- Decreased immunity

- Hormone imbalances

- Lost or irregular period

- Decreased testosterone

- Gastrointestinal issues

- Depression

- Irritability

- Reduced brain volume

- Increased risk for injury

- Decreased coordination

- Decreased glycogen stores

- Decreased training response

- Delayed or stunted growth and puberty (adolescents)

Ashley, a recreational climber I spoke with, said, “I have noticed that at my lightest weight, I did not climb at the level that I currently am … my energy levels weren’t the highest and my recovery times were awful … I would feel exhausted and pumped. Now at a ‘heavier’ weight, my sessions are longer and more effective.”

Rude agrees. Referring to losing weight and her period, she says, “I was afraid of continuing down that path because of injury and the fatigue I was feeling. I think I got scared because I knew better … Most, if not all, climbers … can improve without having to cut weight. More longer-term gains in climbing can come from improvements in technique, analysis and adjustment of specific types of movements, conditioning exercises, improvement of mental game, and for some, even more rest!”

Jeremy Artz is a climber in a bigger body trying to get the word out that all body shapes should climb. He writes, “I think body weight matters in the sense that climbing is a power-to-weight ratio sport … Good technique makes up for a lot of sins, but at some point, strength-to-weight will become an issue. [But] I’ve seen some relatively bigger climbers climb difficult problems.”

What climbers and coaches can focus on instead of weight loss

If you’re wondering how to enhance performance and support training, go see a sports physician, qualified trainer, and sports dietitian. Avoid the knee-jerk reaction to lose weight. Never put an adolescent on a weight-loss diet or comment on their body. Coaches, fellow climbers, parents, and trainers should avoid talking about weight with any climber at any age. Don’t comment on food choices. Do not forbid foods.

So what can you do to send hard, crush it, and get better at climbing? When considering optimizing your strength-to-weight ratio, seek advice from coaches, physicians, trainers, and dietitians to explore what approach to improving performance is right for you. Fuel your body. Eat enough. Train right. Sleep. Spend time learning skills. Get stronger. Be kind to your body.

Climbers share their perspective on weight

Molly Mitchell, 5.14 trad climber

I think it would be naive to say that weight doesn’t play a role in how you feel climbing. Climbing is by nature a strength-to-weight ratio sport. However, I do not think it’s as big of a factor as the strength part. You need to build lean muscle, and that’s hard if you’re just trying to stay super light all the time. And you need your head to be less concerned about what you weigh and more present with learning, trying hard, and having fun.

The focus should never be simply on how much you weigh—this is a slippery slope and has caused many eating disorders in our sport. Best answer I can give is to eat healthy, not less. I eat a lot, but it’s okay because most of it is healthy (although I like treating myself to some cookies here and there!) and I train and climb a lot. My body needs the calories to recover. Kids are particularly at risk for the eating disorders developing in our sport. It’s incredibly important to make sure that kids who start climbing young understand that it’s totally normal to gain weight during puberty, and maybe feel a little off for a bit. The weight will actually help them in the long run.

Also, for adults, I believe it’s completely acceptable to drop a couple pounds when you feel close to sending your project. Again, though, this can’t be taken too far or you will lose energy and injure yourself and that will outweigh the positives of the light feeling. And as in everything, once the project is complete, it’s beneficial to give your body a break and gain the weight back. I call it “fighting weight,” and I only go down to it when I’m close on a project. And I know my limit for what I absolutely cannot go below.

It’s hard to tell someone what works best because weight is a sensitive topic that should be handled carefully. We are all different, and our bodies work differently. To each their own. Most of the time, I don’t use a scale because I don’t want the weight issue to get in the way of me trying as hard as I can—if I know I’m a little heavier than previous days, I might be more likely to latch onto that and sabotage myself. I only bring out a scale if I am extremely close on my project and just am curious what I’m at, and if dropping a pound or two might be slightly beneficial.

Jon Cardwell, 5.15 climber

With climbing, it’s obvious that strength-to-weight ratio can play an important role in performance. It is, after all, the challenge—pulling up against the force of gravity.

However, in my climbing experience, I’ve thought little about weight being the most important factor, as climbing to me seems to be so much more complicated. Strength and endurance, recovery, plenty of sustainable energy, and having a focused mind, among many other things, are important. All of these factors benefit from a healthy diet. If you restrict that diet, you probably will only get a short-term result until inevitably something gives out.

No doubt there have been times where I’m lighter, but that was a result of increased activity. For example, hiking to Céüse or Rocky Mountain National Park to go climbing four or five days a week. On those days and seasons, it was especially important for me to give my body the necessary nutrients during and after. I felt good, and I was having a blast. My head was in a good spot.

That said, I remember departing from a trip in Spain a few years ago. I was climbing with Matty Hong, and he was trying Fight or Flight (5.15b). He stayed a few extra days because it was just too close to leave. The morning I left, I bought some gummy worms, left them on the table and said good luck! I was on the flight home when he sent later that day, and when I landed, I congratulated him and asked if he ate the worms. He said he “crushed them” before they went to the crag. I’m not saying gummy worms are the key to success, and no doubt Matty is actually pretty healthy, but the moral stands. The less stress you put on yourself, the better you’re able to focus and eventually perform.

Stephanie Forté, One of the First Climbers To Speak Up About Eating Disorders, Looks Back

The post What Studies and Experts Say About Losing Weight to Climb Better appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

This high-fat low-carbohydrate diet will deplete your energy and can lead to health issues.

The post Why The Keto Diet Will Hurt Your Climbing appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

The keto diet is the perfect way to kill your climbing hopes and dreams. Hop on this diet wagon and your weak fingers will slide off those slopers as if they were coated in the bacon grease that anchors your food plan. Why?

First, it’s helpful to know what the keto (or ketogenic) diet is. Ketosis refers to the metabolic state your body will enter if you eat an extremely low carbohydrate diet, around 20 to 50 grams of carbs per day. This usually is around 60 to 80 percent fat, and around 10 to 30 percent protein. One medium apple has about 25 grams of carbohydrate—half an entire day’s worth. This is an extremely low carbohydrate intake, especially for an active climber.

When your diet consists of very little carbohydrate, it looks for other ways to metabolize substrates in order to fuel the demands of life. This is when ketosis occurs. Ketones are basically a substrate your body uses for fuel, instead of the preferred glucose. Ketosis is not a state your body likes to be in—it’s a difficult metabolic adaptation that occurs in absence of sufficient carbohydrate.

From a climbing standpoint, ketosis is not a good idea. Your brain and skeletal muscles prefer carbohydrate as their fuel source. Limiting it to a measly 20 to 50 grams per day is a recipe for fatigue.

At lower intensities, your body uses both fats and carbohydrates as fuel sources. When working above 60 percent of your maximum effort, your body uses carbohydrate. The nature of climbing usually switches back and forth in intensity, such as doing a long trad route with a powerful crux, or a boulder problem with a dyno. These high-intensity efforts need carbohydrate. If your body is getting fat and protein with very few carbs, it is difficult or impossible to be powerful. If you’re a speed climber, forget about it.

You Start To Lose 25% Of Your Strength At Age 25. Here’s What To Do About That.

Training adaptations are also blunted on a low-carb diet. Carbohydrates are the key to powering movements during training and fueling recovery.

Over decades of research on the keto diet and athletic performance, not one study has shown improved performance. Research reveals:

- Same performance but increased rate of perceived exertion

- Decreased performance

- Reduced power

- Increased time to fatigue