Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

“Although physics began with ordinary objects, it developed as a science of forces and movements that are less obviously material yet from which matter is inseparable.”

—From New Materialisms: Ontology, Agency, and Politics by Diana Coole and Samantha Frost

Indoor climbing began with ordinary objects. Artificial walls were furnished with holds that were either rock or mimicked rock, and climbers did moves designed to imitate action outside. The relationship between indoor and outdoor climbing was clear.

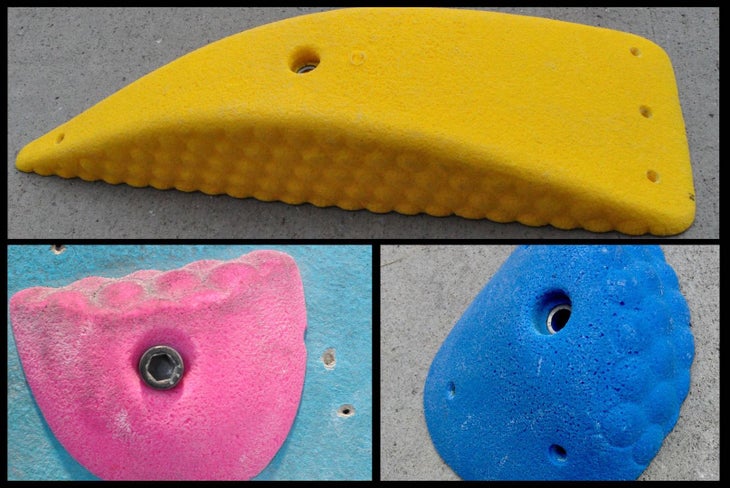

But hold shaping since those early days has changed dramatically, as innovations in tools and materials—from pilfered river stones and chiseled 2x4s to sand and polyester resin to contemporary polyurethane and fiberglass—enabled new textures and larger shapes. And as hold-shaping techniques evolved and indoor climbing grew more popular, it wasn’t long before certain hold-shapers began questioning the idea that the indoor experience was beholden to the outdoor one, involving pretend rocks and, by extension, pretend rock climbing. Eventually, they began making grips that took unabashed inspiration from urban or human objects—the bubble wrap that we all loved to pop as kids, a lightbulb, a baby head.

As objects, these holds tell a story about the history—and future—of our sport, and describe a gradual transformation from representation (holds mimicking rocks and existing outdoor movement) to what social scientists call performativity, the idea that holds—or any other objects or signs—can intervene in the world, which in this case means influencing the way we see and relate to real rock.

The Bubble Wrap, the Boss, and a new philosophy of movement.

First shaped by Ty Foose for eGripps in the 1990s (since acquired by Trango), the iconic Bubble Wrap texture marked one of the first clear and successful departures from the idea that indoor holds should emulate rock. “If it were a book series, Bubble Wrap would be like Harry Potter” setter Connor Schwartz told me. But while its name and shape are distinctly non-organic, Bubble Wrap still offers us a tactile experience reminiscent of real rock: Its complex surface makes us search for the correct hand position—“Should I palm this like a sloper? Should I try a several-bubble crimp?”—and those subtle choices can mark the difference between sending and falling.

The same was true of the Lightbulb, made by So iLL in the early 2000s, which did not go on to become a lasting classic like Bubble Wrap, perhaps because it was slimy and unappealing to grab, and perhaps because of its extreme disavowal of the natural. But it represented a kind of provocation to setters and hold companies to embrace indoor climbing in its own right. As setter John Marlatt put it, the Lightbulb and other urban designs “paved the way for a lot of these other companies that decided to depart from the natural stone texture and say, ‘We’re not rock climbing. We’re gym climbing.’”

Since the 1990s, shapers have experimented with balancing themes derived from popular culture or urban life with aesthetics of “nature,” which often includes rock types, climbing areas, bodies, or creatures. (Most contemporary hold companies feature both natural and cultural shapes. Trango presents Bubble Wrap and Galactic next to Fontainebleau and Dakota. So iLL boasts hold families from Babyheads and Pipes to Roids and Fungus. Rock Candy has lines called Brachiopods, Coprolites [meaning fossilized dung], and Trilobites alongside Gelatos and Tunnel Rats.) Shapers have also learned, in the past few decades, how to create large objects that encourage dimensional movement—suggesting that what is translatable from rock to gym is not simply the material or color of holds, but rather the physical and emotional questions they facilitate.

Perhaps the best and most transformative example of this was the Boss—a large brain-like sloper first made by Mike Call and Marc Russo from polyester resin for Pusher in 1994. A Pusher Instagram post featuring an old black and white photo of an early “Boss” hold begins: “An old friend… This is arguably the most famous climbing hold that has ever been created.”

View this post on Instagram

Why is the Boss iconic?

“Because it was big,” says climbing coach Andrew Lee. “If you ask any climber from my era—someone who started climbing 20-plus years ago—what is the most famous climbing hold, that’s the hold they’re gonna pick.”

In competitions of the 1990s, athletes were generally tested on their ability to pull down on small holds, a criteria informed by the outdoor face climbing then in vogue and by the limitations of the artificial walls and holds available. There were some slopers on the market, but the Boss was so big that it actually changed the “shape of the space,” as Noah Walker put it in an article about Pusher. “It showed the significance of volumes in route building.”

Setter and shaper Roy Quanstrom explained to me how the Boss enabled setters to conceptualize movement differently: “Instead of setting these forced moves on individual holds, we can put a THING on the wall, and allow the climber to be creative in how they get through it. The Boss was one of the first holds that really allowed route setters to experiment with that kind of movement.”

The Boss was not supposed to be a rock. Nor was it a repudiation of nature. Modeled after an experience the shapers had climbing on the sloping sandstone of Fontainebleau, the Boss was an invitation to press, squeeze, and wrestle up vertical terrain. It gave setters the ability to offer climbers a more creative, three-dimensional experience on the wall—which subsequently became key to indoor setting when wooden volumes and large, easily movable fiberglass “macros” grew more available in the 2000s (see Jackie Hueftle 2021).

How we move indoors is changing how we see rock outside

The modern aesthetic of shiny fiberglass macros might seem like an extreme departure from real rock climbing. But it is through these large features that setters can create the kinds of multi-dimensional experiences we so often encounter outside. In many ways, by not trying to be rock, indoor climbing is better able to emulate the range of experiences offered by its real rock counterpart. Indeed, most thoughtful setters and hold-shapers seem to disagree with the common quip that comp climbing has totally diverged from rock climbing. When rock climbers claim that some kind of comp-style movement doesn’t “exist” outside, what they really mean is that people have not historically possessed the imagination or ability to make those types of movements happen on rock—not that they can’t be found there. Just as outdoor climbing created the mimetic premise on which indoor climbing was built, indoor climbing is now defining the way many climbers see movement and potential outside. For example, a boulder problem like Industry of Cool—a huge paddle dyno in Rocklands, South Africa—wouldn’t have been conceptually possible in the pre-gym era.

But the relationship between outdoor climbing and indoor setting isn’t just about movement: it’s also about emotion. If large holds and volumes enable setters to craft space in multiple dimensions, increasingly sophisticated dual-textured and no-tex holds help setters craft affective experiences, forcing climbers to navigate emotions like fear, anxiety, confidence, and even revulsion. Do you really want to step on something that slippery? Do you have what it takes to do this committing off-balance dyno? What counts as a usable surface? What did the setters intend here, and how can I subvert that to play to my strengths?

In other words: If setting began with ordinary objects, it has become a science of forces, movements, and affects.

“The movement,” Roy Quanstrom says, “isn’t always about the hold. The movement, to me, is about the implication of the hold; the situation.” Where holds once represented rocks, they now (in the hands of a good setter) actively shape how we conduct ourselves, both on plastic and on stone.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: Thank you to Roy Quanstrom, John Marlatt, Connor Schwartz, and Andrew Lee for humoring my questions. For readers interested in a detailed history of climbing holds, I recommend Jackie Hueftle’s excellent pieces in Vertical Life magazine (cited below).

References:

Coole, Diana, and Samantha Frost, eds. 2010. New Materialisms: Ontology, Agency, and Politics. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Hueftle, Jackie. 2019-20. “Climbing Holds, a Historical Overview.” Routesetter Magazine, Issue #2, pp.40-51.

Hueftle, Jackie. 2021-22. “Climbing Holds, a Historical Overview Part II – Fiberglass and Wood Volumes.” Routesetter Magazine, Issue #4, pp.46-55.

Hampton, Kris. Power Company Podcast. “Roy Quanstrom: Translating Movement Through Shaping and Setting.” Power Company Podcast. Available at: https://www.powercompanyclimbing.com/blog/roy-quanstrom.

Walker, Noah. 2021. “Pusher Holds—Climbing’s Most Iconic.” Gripped.com. Available at: https://gripped.com/profiles/pusher-holds-climbings-most-iconic/