'Zone Local' has the beta on the best hidden boulders of Fort Tryon, proving that Manhattan's climbing history goes beyond Central Park.

The post These New Maps Reveal New York City’s Underground Bouldering Spots appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

In New York, nature survives by force, not grace—stretching toward the sun, splitting the sidewalk, refusing to yield. Life insists, whether in soil or cement.

Street lamps throw shade beyond the reach of branches. Gutters rush with the same insistence as the Hudson. Brakes and engines layer into a birdsong of their own.

Here, growth is reclamation. And sometimes, it’s louder than the subway.

On the northern tip of Manhattan, Fort Tryon is another kind of fracture. One moment you’re on the grid, the A train spitting riders onto 207th. The next, the city thins. Switchback trails climb past stone arches, gardens spill over old walls, and the ground rises into slabs of schist.

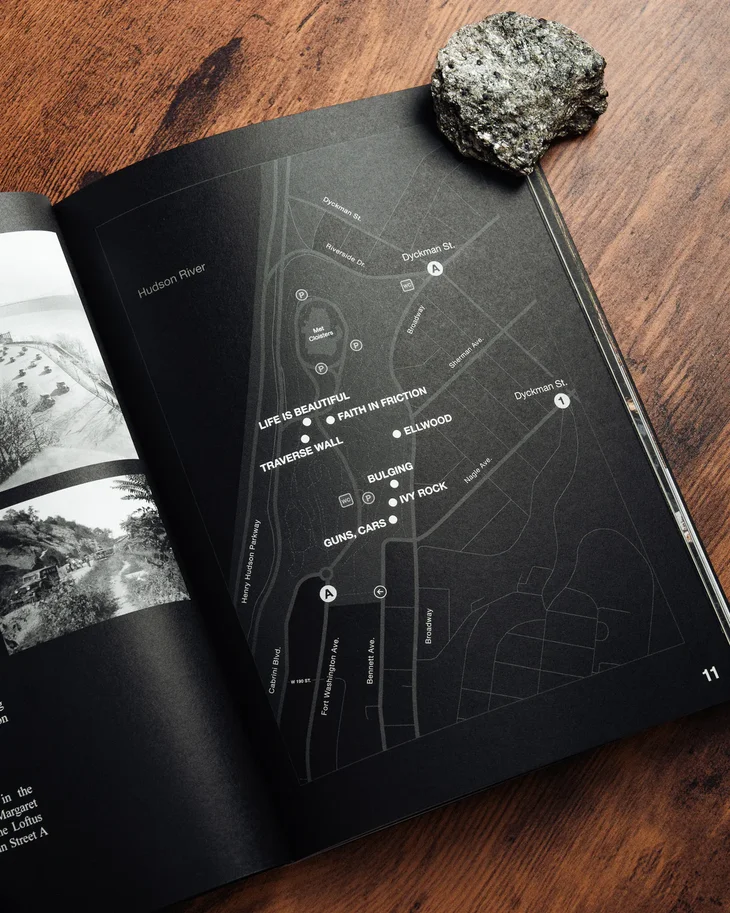

For decades, most of the city’s climbers looked elsewhere for their fix: Central Park’s polished boulders or long drives north to the Gunks and Harriman. Fort Tryon’s stone, sharp and unpolished, was documented in earlier guidebooks such as Gaz Leah’s NYC Bouldering and Sam Lerner Dreamer and Conor O’Hale’s New York City Bouldering, but the area received less attention. Many problems were repeated over the years, known mainly to the local climbers who frequented the park.

Now, with Zone Local, climbers Trevor Riley and Rachael Elliott have given them form: a new guidebook equal parts topo, design experiment, and archive. Closer to field notes than a coffee table book, it documents the persistence of climbing in New York—and the community that refused to let it vanish.

For Trevor Riley, Fort Tryon was first a matter of proximity. When he moved to Washington Heights in 2021, the park became his local crag—fifteen minutes on the bus, thirty on foot. “I’m a picky climber,” he says. “Aesthetics matter. Fort Tryon might be the most scenic park in NYC. Central Park doesn’t overlook the Hudson and the Palisades. And the boulders here don’t suffer from as many contrived variations as Central Park’s polished schist. For me, it was hard to beat.”

For Elliott, the pull was slower. A designer by trade, she first climbed in Central Park and up at Powerlinez. But Riley’s enthusiasm carried. “The park is quite arresting in its hidden beauty and how remote it feels although you are still in the city,” she says. “That atmosphere of wonder made me prefer it over Central Park’s boulders, which tend to be more crowded.”

Zone Local reflects those two vantage points: Riley’s eye for climbs that unfolded organically and Elliott’s drive to shape a book that was intentional in both design and use. “It’s a privilege to print something and have it exist in the world,” Elliott says. “We wanted it to matter.”

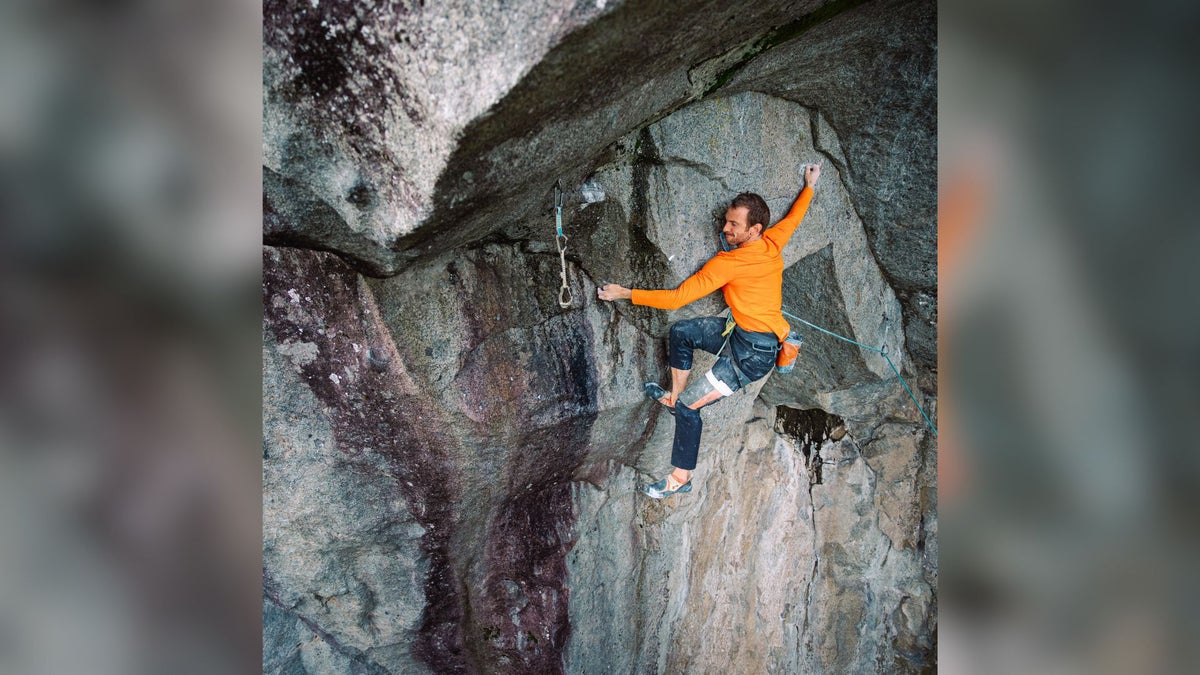

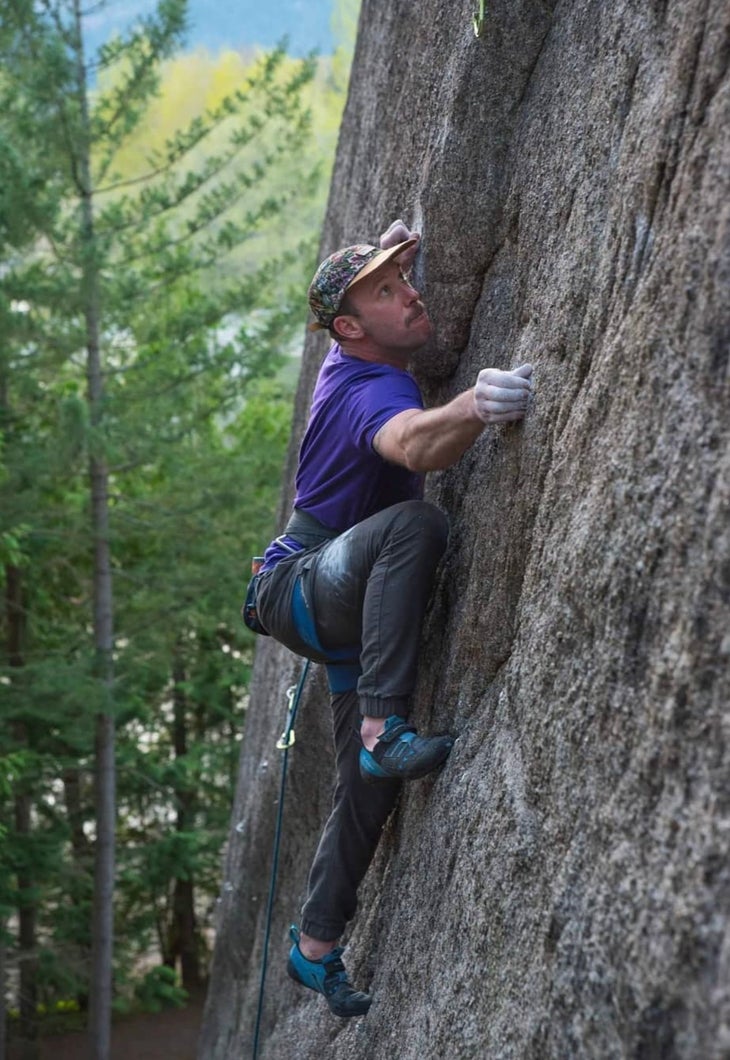

Making the book required discipline. Photos were the hardest part. “Even though Fort Tryon is scenic, New York doesn’t exactly scream natural beauty,” Riley says. “Getting the right climber on the right boulder in the right light was rare, but necessary: “I wanted the photos to be impressive enough that even climbers from the most incredible places would want to visit.”

Elliott faced the opposite challenge: restraint. “The most difficult part was distilling through the noise and honing in on the important design elements and concepts,” she says. “Collaboration can often be tedious, but it’s almost always worth it in the end.”

The result was a minimalist guide, scaled for use. It can be held open with one hand. It fits neatly into a bag. The cover was given a scuff-resistant coating. Practical choices, but also intentional ones. “We thought guidebooks could be both useful and pretty,” Elliott says.

If the design demanded restraint, the history demanded digging. Riley fell into rabbit holes of Mountain Project threads, defunct blogs from the early 2000s, and even long-dead sites pulled up through the Wayback Machine. Every lead pointed to another—a rumor about a first ascent, a name dropped in a comment, an old website documenting Central Park problems. From there, he started reaching out directly, asking who was still around.

Some were. Climbers who had been pulling on Manhattan schist since the 1980s sat with him and helped fill in pieces of the story. Nicolas Falacci’s early website, Beta-Boy.com, became a touchstone. Ivan Greene’s contributions, like the proud line It’s a Wonderful Life (V11), immortalized in the Reel Rock film Dosage II, surfaced again in memory. Ralph Erenzo, who co-founded the City Climbers Club of New York in 1987 and later helped open two of the earliest climbing gyms in the country, emerged as a key player.

Other stories surprised even Riley: a climbing competition in Central Park in 2011 that drew a crowd of more than 20,000, and the 2008 Dabathon, when climbers, cyclists, and daredevils linked every climbable area in the city into one circuit. During the later, climbers were even chased at one point by police on horseback. “The internet is a messy, endless place to explore,” Riley says. “Once I’d found everything I could online, I started asking locals if certain climbers I’d read about were still around. In the end, it’s insufficient and imperfect. But we hope that the loose ends in our brief overview of NYC’s climbing history lead other climbers down the path of discovery for themselves.”

New York has never been a climbing destination, and maybe that’s the point. No one books a trip to boulder between subway stops. But that doesn’t mean the rock isn’t here—or that the restless need to climb is missing. What Zone Local argues, quietly but firmly, is that local climbing matters, even in a city like this.

“People are often surprised to learn we have climbable boulders in our parks,” Elliott says. “After that, they’re surprised by the variety of grades and the difficulty. Fort Tryon has plenty of project-worthy routes that truly test you.”

Riley agrees, but pushes the thought further. “Climbers will live in Manhattan for years and never climb the classics a couple train stops away,” he says. “I love climbing upstate, but I believe we owe our local zones more love.”

That sense of obligation runs through the book. It isn’t just about wayfinding; it’s about insisting that these places—the overlooked stone in city parks—belong in the story of climbing, too.

In the end, Zone Local feels less like a product than a gesture: proof that climbing in New York has always been a practice of reclamation. The stone resists, the city resists, and still the problems remain.

For Riley and Elliott, the book is both map and memory. It points to where to put your hands and feet, but also to the larger work of building community, preserving space, and telling stories with depth. It insists that climbing in Washington Heights matters—not because it rivals the Gunks, but because it refuses to be overtaken.

Riley hopes that future guidebooks and stories go deeper, that climbers here write more than captions. Elliott hopes more people step outside and touch the rock for themselves.

Zone Local is available for purchase now at zonelocal.net.

And when asked what he’d say to anyone who doubts that bouldering belongs in Manhattan, Riley doesn’t hesitate: “Fuhgeddaboudit.”

This article has been updated to reflect that Fort Tryon boulders are featured in NYC Bouldering by Gaz Leah and New York City Bouldering by Conor O’Hale and Sam Lerner Dreamer.

The post These New Maps Reveal New York City’s Underground Bouldering Spots appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Boulder, eat, wander, repeat: The French Olympian shares her routine for living between the Magic Forest and the capital city.

The post Oriane Bertone Shares How to Climb and Eat Your Way Through Paris and Fontainebleau appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

From week to week and morning to night, French pro climber Oriane Bertone keeps a foot in two worlds. The first is Fontainebleau, where thousands of acres of protected forest cradle thousands of internationally iconic sandstone boulders—and where Bertone now lives. The second is Paris, just an hour and a half north of Font by car and less than an hour by train.

When we spoke, Bertone shared her schedule for a recent week of going back and forth between the City of Light and the Magic Forest. It’s heavy on bouldering: Bertone holds the 2025 IFSC Boulder World Cup title and hopes to compete solely in bouldering at the 2028 Olympic Games, now that the disciplines will be split up. “I’m a boulderer, and I always knew it,” Bertone says.

Bertone spent Monday in Fontainebleau, working out and climbing hard boulders at Karma, a local gym staple and one of the training centers for the French national climbing team. On Wednesday, she went up to Paris and climbed at one of the 11 Arkose bouldering gyms scattered about the city (Arkose is a sponsor of Bertone’s). She can’t exactly remember which one, but it was probably Arkose Issy-les-Moulineaux, where she likes to train slabs and dial in her breathing. Thursday was a rest day in Fontainebleau, followed by another two days of climbing in Paris. “It’s always kind of like this,” Bertone says of her weekly routine.

It’s safe to say that the 20-year-old climber has insight on making the most of the indoor and outdoor bouldering in Paris and Fontainebleau. Bertone sat down with Climbing to share her tips, along with her favorite spots for rest day recreation, food, and culture in each area.

Where to climb, eat, and revel in the arts in Paris

Bertone started climbing indoors and outdoors as a kid in her hometown of Réunion Island, a French territory east of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean—more than 5,000 miles away from Paris. Her father didn’t have a climbing background himself, but he was fascinated by movement and fastidious in giving Bertone and her sister chances to climb the island’s abrasive, volcanic rock. “This is probably why I have thick skin now,” Bertone says, laughing.

She also credits her father with imparting to her the notion that “if you start something, you have to finish it.” When she moved across an ocean to Paris to train with the French national team in 2021—leaving her tight-knit family behind at only 16 years old—she leaned into that mindset. “I knew what I wanted,” Bertone says. “Everything fell into place.”

During Bertone’s first two years in mainland France, she lived in Massy, a southern suburb of Paris. As she settled in, Paris became one of her favorite cities in the world. “People can say whatever they want; I like Parisians,” Bertone says. “It’s always cool to walk around, see the little shops, drink good coffee. You’re able to get on the internet and go, ‘I want to eat Korean food,’ and walk two minutes and there is a Korean restaurant. There is everything in Paris.”

So how would Bertone enjoy the city as a climber? Let’s start with the indoor climbing in Paris. There are dozens of gyms in the city, but Bertone recommends Arkose bouldering gyms. She acknowledges her bias, but says she initially partnered with them because they’re her favorite. She goes to Arkose Nation and Arkose Issy-les-Moulineaux for slab climbing and finds the best hard boulders at Arkose Massy. “Everybody goes [to Massy], even the strongest people,” Bertone says.

Between training sessions in Paris, Bertone likes to refuel with Korean food at Sweettea’s, which serves classic dishes like bibimbap, barbecued beef, dumplings, and kimchi pancakes. The Asian fusion restaurant also serves honey mustard fried chicken and a mozzarella-infused take on tteokbokki, a Korean rice cake snack. Bertone’s rest day recommendations also include taking a walk through the Jardin du Luxembourg (just don’t go on weekends) and going to the opera at the world-renowned Palais Garnier. Heavy hitters like the Louvre are also worth seeing.

“I can cry in front of a painting or because somebody’s singing in a high-pitched note,” Bertone says. “I’m deeply touched by art, so I like going to operas and museums. And in Paris, we have so many.”

Bertone remembers the influx of visitors coursing through Paris when she competed in climbing at the 2024 Olympic Games. Looking back, she says she felt more energized than overwhelmed by being in that position. It helped that the French people kept their Olympic patriotism lowkey, Bertone says. “The people were proud of us and happy it was in France, but I think they were more upset about the expensive prices of the tickets,” she says. “I didn’t feel pressured at all.”

Though Bertone liked life in Paris and the Massy suburbs, when she turned 18, she thought about making a change. She had first traveled to Fontainebleau with her family when she was eight years old; ever since, she had dreamed of being closer to the sandy forest. They kept coming back throughout her youth, during which she managed sends of Satan I Helvete Low Start (suggested to be 8C/V15 at the time) and Super Tanker (8B+/V14). “I fell in love with climbing because of this, for sure,” Bertone says of her trips. “It was a dream place. Every time I left, I was sad and I was crying. I wanted to stay.”

Two years ago, Bertone finally moved to Fontainebleau. “This is where I’m happiest,” she says. When asked how she’d go about traveling to La Forêt for the first time, Bertone positively lights up.

Boulders, pastries, and leaving no trace in Fontainebleau

La Forêt, the Magic Forest, ‘Bleau, Font — Fontainebleau is known by many names. Bertone found a house there in 2023, where she now lives with her boyfriend and dog. But what exactly drew her there? “Just imagine,” Bertone says. “You’re like, ‘I want to climb outside.’ You take your car, your crash pads, you drive, you park, you walk five minutes, you climb. You put your crash pad in your car, you go home. Then, you’re like, ‘I want to go again tomorrow.’ The same thing. You walk in the sand and you climb whenever you want, wherever you want, every day. You don’t have to walk 10 miles just to get to the point where you want to go. It’s easy, practical, and beautiful. It smells like dirt and roots and rock. For me, Font is just the place to be.”

Bertone’s guide to Fontainebleau starts with getting there from Paris. She prefers taking the R train from Gare de Lyon, one of the capital city’s major train stations. Get on the R line, color-coded pink, in the direction of Montargis. You’ll make stops at Melun and Bois-le-Roi before arriving at Fontainebleau-Avon. If you’re not in a rush to get to Fontainebleau and it’s warm out, get off one stop early at Bois-le-Roi and go swimming at the base de loisirs, or outdoor activity center. Spring and autumn are popular climbing seasons in Fontainebleau, though Bertone’s season often depends on the demanding IFSC competition schedule.

Once you arrive in Fontainebleau, Bertone recommends renting bikes. There are plenty of ride sharing services like Ubers around as well. If you want to visit each of the charming, little nearby towns like Milly-la-Forêt or Arbonne-la-Forêt, you may also want to rent a car. Those towns are also chock full of comfortable gîtes (countryside home rentals) and Airbnbs.

You can find just about any kind of boulder you want in Fontainebleau—crimpy, slopey, physical—laid out neatly on Bleau.info. The selection is so dazzling, it’s almost indescribable (but Chris Schulte does a good job of it here). For first-timers, go-to sectors include Bas Cuvier, Isatis, Cuisinière, and Trois Pignon’s sandy Cul de Chien. “They have very easy access, and the boulders there are awesome,” Bertone says.

But tourists, be warned: the code of environmentally-responsible climbing ethics runs deep in Fontainebleau. Bertone breaks down some of the rules, which are in line with the Access Fund’s Climber’s Pact: Don’t climb too early or late and shine lights on the rock in the dark, disrupting the wildlife. Don’t blast music for the same reason. Leave no trace with trash—or poop. “Don’t wipe your ass with wipes and throw them in the forest,” Bertone says. Clean tick marks. And do not climb the sandstone after it rains or in high humidity. “You have to think: Would you like to be there after yourself?” she asks. “There are so many people coming. You have to be attentive to the wildlife and the forest. Don’t stop it from growing because you’ve been careless.”

If it rains, head over to Karma instead, where you can often spot Bertone and her teammates training. The gym also rents out crash pads for when you do get to climb outside. Another rainy day or rest day activity Bertone recommends is a visit to the Château de Fontainebleau in the region’s city center. And while you’re in town, pay a visit to Bertone’s three favorite restaurants: Démé for pizza and pasta (it’s always packed, so make a reservation); MA.SU for Japanese food (try the foie gras sushi); and L’A pâtisserie (get a big box and try one of each pastry).

Commuting between Fontainebleau and Paris and toggling between indoor and outdoor bouldering offers Bertone distinct challenges and opportunities—to which climbers young and old and new and experienced can relate. When Bertone trains in Paris, working to get better each day makes her feel alive. When she climbs in Fontainebleau, she’s struck by the passage of time. “I go back to a boulder I did 10 years ago and I’m like, ‘I can’t do it anymore,’” Bertone says. “Sometimes, it’s surprising. It feels like every year is full of lessons and full of new things.”

The post Oriane Bertone Shares How to Climb and Eat Your Way Through Paris and Fontainebleau appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Featherbagged—aka “soft”—cragging and bouldering areas for your climbing pleasure

The post The World’s 7 Least Sandbagged Climbing Areas, Ranked appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Sandbagging hits us where it hurts the most—right in the ego. When your psyche gets hit hard by one of these notoriously sandbagged areas, there’s only one cure: Soft grades. Put the pieces back together again with some easy ticks for the rating.

“Featherbagging”—giving Charmin-soft grades to routes and boulders—is just as much a climbing tradition as sandbagging. Heck, sometimes gyms and destination areas even use it as a secret tool to get repeat “customers.” You climb your hardest there, and so come back for more, gleefully opening your wallet.

Gyms aside, the following seven areas are all known for featherbagging. As with all climbing venues, of course, much of this is subjective. There’s variance between climbs, and you’ll still find sneaky sandbags lurking in the shadows, waiting to draw blood.

So go forth and climb soft at the world’s least sandbagged areas, ranked from somewhat featherbagged to “Wow, I’m a better climber than I thought” featherbagged.

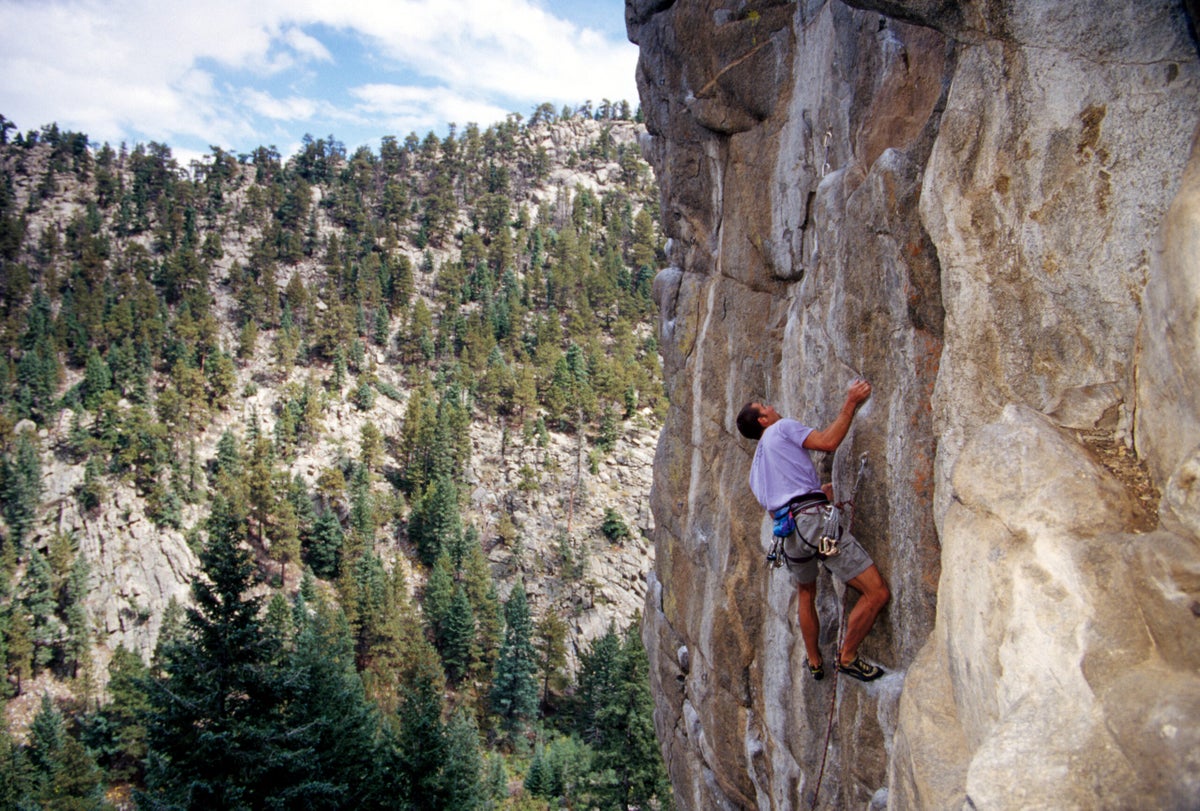

7. Boulder Canyon, Colorado

As far as backyard areas for Colorado’s Front Range go, Boulder Canyon is one of the most historic. Here you’ll find some of the country’s earliest 5.10s and 5.11s, dating back to the 1960s. But make no mistake—the original routes on the area’s granite, like Country Club Crack (5.11c) and Umph Slot (5.10c)—are not the softies you’re looking for. Rather, it’s the newer sport areas from the 1990s and Aughts, like Avalon, the Rivieria/Bihedral, and Cascade Crag, where the routes typically range from 5.9 to 5.11.

Furthermore, Boulder Canyon’s granite is rough and featured, with slabby to vert angles that make it easy to piece together beta as you go. Plus many climbs are gym bolted (see the routes of Sport Park), inspiring leader confidence.

6. Indian Creek, Utah

It’s not 100 percent accurate to say that the Wingate-sandstone cracks of Indian Creek are soft. In fact, they’re long, continuous, pumpy, and (often mercilessly) the same size from deck to anchors. But given how homogenous these cracks are, the splitters that fit your fingers perfectly for locks, or accommodate your hands for jams will feel “easy” at the given grade.

So, people with big hands will find Supercrack to be slammer hands and chill at 5.10, while the small-handed might find it to be a loose-fists 5.11. Or take the infamous 5.11+ rattly-fingers face splitter Johnny Cat, which protects with 0.5 Camalots. In all honestly, it felt like 5.9 to me with my Jimmy Dean sausage fingers, even as the neighboring 5.11+ tips crack Puma slapped me around and stole my lunch money.

5. Red River Gorge, Kentucky

This might be a controversial pick. Some people find the Red to be stout—and those people are called boulderers! However, if you are blessed with ample endurance, aerobic capacity, slow-twitch muscle, and good on-the-rock strategy, the Red’s Corbin sandstone is nirvana. The cruxes rarely exceed V4–V7, even on 5.13s and lower-end 5.14s. Most holds are super-friendly deep pockets, huecos, and incut, grippy crimps.

So if you can read the rock and hang on like a sloth, you will take routes down at the Red. On the flip side, the pitches are wildly overhanging and you need to be fit. Perfect examples of this treadmill style include the Chocolate Factory’s Oompa (5.10b), Naked (5.12a/b), and Silky Smooth (5.13c). These routes are all doable for their grades, with no real stopper moves. But they also all deliver a massive pump.

Watch Ada Cronin take down No Redemption (5.13b) in the Red with ease

4. Rocklands, South Africa

The brightly colored Cederberg sandstone of Rocklands is legendary for a reason: It’s fun, featured, solid, and steep. Untold boulder fields stretch as far as the eye can see. Another lure? The area’s user-friendly grades. Many make the pilgrimage to tick their first 8B (V13), given how many options there are to fit one’s unique strengths.

Coloradan Brian Stevens recently spent a season in Rocklands. He said that as a rule, the problems felt two V-grades easier than Hueco Tanks and one grade softer than Joe’s Valley. For example, the classic V4 jug roof of Girl on Our Mind felt on par with the similar roof climb Nobody Here Gets Out Alive (V2) at Hueco. Another factor is the sheer density and volume of problems. “Rocklands has so much, and you can pick and choose whatever you want,” Stevens says. “It’s like nature’s Kilter/Tension/MoonBoard, where you just swipe to the next problem if you don’t like the current one.”

3. Kalymnos/Telendos, Greece

Kalymnos and the neighboring island of Telendos offer perfect blue, white, grey, and tan limestone laced with tufas and stalactites. But there’s more—these routes come riddled with pockets, flakes, sidepulls, and crimps. And with hundreds of climbs from 5.7 to 5.14+, life is good here. Climb sublime rock in the morning, then take a dip in the blue-green Aegean Sea when it gets hot.

But the isles are also known for “holiday grades,” usually a letter or two soft, perhaps engineered to lure repeat visitors. Colorado climber Chris Weidner cites Punto Caramelo, an 8a+ (5.13c) in Kalymnos’s Grande Grotta. He sent it second try and said it felt more like 7c+ (5.13a). “The ‘soft’ feeling in Kalymnos came mainly from the size of the holds: they’re just bigger than you might expect at a crag in, say, France,” says Weidner. “Of course, the Grande Grotta is very steep—probably from 10 to 40 degrees overhanging—so the holds are necessarily larger.” (See also the “Red River Gorge.”) Weidner adds that the tufas make it easy to find kneebar rests mid-route.

2. Moe’s Valley, Utah

This St. George winter destination is a boulderers’ playground, with tight clusters of blocks and a high density of problems. You’ll also find mostly flat landings that are friendly for families and kids. It also has squishy grades, but because everyone’s having so much fun, no one seems to take issue. Says onetime Utah climber Ryan Pecknold, Moe’s has “pockets and edges galore, and most routes are straightforward and require minimal creativity and imagination, with juggy topouts that rarely require a sketchy high heel hook.” In other words, just pull down. (Utah’s Joe’s Valley, though stiffer than Moe’s, has been called soft for similar reasons: lowballs, heavily chalked/ticked holds, easy access, lots of problems to choose from, etc.)

Epitomizing the accommodating Moe’s style is Crippler (V6) in the Sentinel Area, a well-chalked lowball with good holds that might be many a climber’s first V6. At the Pink Lady Area, the photogenic IsRail, also V6, is another classic local example. Impressively, Timothy Kang did 10 double-digit problems from V10–V13 during his first day at Moe’s. This perhaps confirms that the area is soft—but also what a beast he is.

1. Ten Sleep Canyon, Wyoming

Ten Sleep is one of those areas where climbers get lots of firsts: “first 12a onsight,” “first 5.13b in a day,” “first 5.14a redpoint,” etc. This would certainly lead one to believe that it’s featherbagged. And overall, it probably is, especially when compared to the cranky grades at other Wyoming dolomite areas like Wild Iris. On the flip side, some of the older climbs, like Go Back to Colorado (5.12b), are stiff. Beware of wild cards!

In truth, what mostly makes Ten Sleep “soft” is the featured limestone. Tiny crimps and pockets abound, allowing for multiple beta solutions. This also makes it easy to wander off the bolt line, perhaps looping around a crux that the first ascensionist beelined straight up. Famous case in point: the Grasshopper Wall testpiece Blue Light Special (5.13b).

View this post on Instagram

Honorable Mention: Kilter Board

As with the MoonBoard listed as an honorable mention for one of the most “sandbagged areas,” this one’s a bit tongue-in-cheek. Still, of the “Big Three” boards common in the States—the MoonBoard, Tension Board, and Kilter Board—the Kilter Board perhaps has the softest grades. Or maybe there’s just more variance within each grade range. (Don’t worry, there are plenty of stiff rigs. See any problem set by Jimmy Webb or the crimpy offerings on the Fullride 7×10 home wall).

Friendly and ergonomic holds, rounded jugs, flat crimps, and pinches also make the Kilter Board less tweaky. This makes it more conducive to putting in multiple project burns. It also favors taller or more dynamic climbers, with big jumps to positive holds. UK climber Toby Roberts famously did 50 8As (V11s) in an hour on the Kilter Board. Five reps of 10 separate V11 problems is something I can’t imagine anyone pulling off on the fingery MoonBoard. But hey, prove me wrong!

The post The World’s 7 Least Sandbagged Climbing Areas, Ranked appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

The history of the route up Luzzone Dam, plus your mini guide to climbing it.

The post The World’s Tallest Artificial Route Soars up a Dam. Here’s Your Guide to Climbing It. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

While people have been climbing the Luzzone Dam for well over two decades, the concrete cliff recently had a moment in the spotlight on the Disney+ TV series Limitless. In a recent episode, actor Chris Hemsworth confronts fear—and possibly frostbite—by climbing the five-pitch dam.

Climbing a giant dam in Switzerland might sound ridiculous, but since I live three hours away in Lausanne, I decided to try it. It turns out it is ridiculous—and also ridiculously fun.

My experience climbing Diga di Luzzone

Research told me to expect plenty of two things: exposure and bird poop. Both were true. From a distance, it’s hard to see that there is indeed a climbing route that goes to the top. This is mainly due to the sheer size of the dam—it rises some 165 meters (541 feet) above the Verzasca Valley. As we walked closer, the route began to appear—along with the realization of how much exposure we were about to experience. Standing at the base of the Luzzone Dam triggered the same vertigo I felt under El Capitan. No moderate route I know of matches this level of exposure.

My friend Caroline and I began our climb around noon in late August. Our idea? Attempt to create an official speed record for Luzzone. As far as we knew, there was no prior speed record attempt on the route and no known speed records existed. Though we were tired from working the weekend prior at a local climbing fest, we set a simple goal: Climb fast, but above all, have fun.

To achieve the fast part, we decided to link the five pitches into two by simul-climbing with a 60m rope and 25 quickdraws. Since the recommended rack is 14 draws, I skipped nearly every other bolt until we reached the third pitch. (A quick note on simul-climbing: This is a dangerous form of climbing. Anyone who uses this technique should be very confident in their skills and systems for this type of climbing.)

The grades increase slightly with each pitch, not due to the movement itself, but because the dam gently curves from slab to vertical higher up. A few of the 600-plus holds drilled into the Luzzone Dam were broken, and one was spinning. With the amount of weather this wall receives, it’s rather impressive this is the extent of the damage to the route.

Thanks to the dam’s curved flat shape, I could chat with Caroline the whole way up. Generally, our conversations focused on the sheer volume of crunchy bird poop that we encountered—and the silly nature of what we were doing.

Caroline led the last two pitches in style. She took a short minute at the belay transfer, but basically did not stop climbing until reaching the top. We topped out in one hour and 18 minutes, with a car-to-car time of about three hours. This includes two (very necessary) cappuccino stops before and after climbing.

I later found out that rumors say the speed record was about 30 minutes, so at least we know what to shoot for next time. We are already planning the next attempt … with glitter, silly costumes, and more quickdraws!

Climbing the dam is a one-of-a-kind experience. I’ve never been on a multi-pitch route that felt so exposed, so absurd, and yet so much fun on moderate terrain. I’d even dare to say there’s nothing else like it. If you don’t take climbing too seriously, you’ll absolutely love it.

A short history of Switzerland’s Luzzone Dam

While construction on the dam itself wrapped up in 1963, the climbing didn’t come to be until several decades later. Just a few years after the height of the dam was extended by 17 meters in 1998, the Ticino Alpine Guides Association bolted a five-pitch sport route up the dam in 1999.

The local tourism board had wanted a new attraction in the valley, so the guides got creative. They designed the route in a climbing gym using a scale model of the dam, measuring every hold. Then they bolted into the 165-meter concrete wall, making it the longest artificial climb in the world.

Since then, the Ticino Guides have continued to oversee the route with annual maintenance. Each spring, guides rappel the dam, inspect every hold and bolt, and replace what’s worn out. In 2023, several anchors were upgraded and small ledges were added at the belays to make the exposure slightly less terrifying.

Luzzone is actually one of three climbable dams in Ticino. About an hour and a half away from Luzzone, the Verzasca Dam hosts the Red Bull Dual Ascent competition and is only accessible to professionals associated with Red Bull. And a two-and-a-half-hour drive away, the Sambuco Dam offers a much more beginner-friendly climbing experience than the Luzzone Dam, with five routes, all more moderate than the line up Luzzone.

As for Hemsworth’s recent ascent of Luzzone (on toprope), the secretary of the Ticino Alpine Guides Association, Pierre Crivelli, says locals aren’t complaining “as long as the region, privacy, people, and the land are respected.” Crivelli mentioned several other Luzzone cameos in popular media. One example he shared is a series of YouTube videos from five years ago wherein people throw objects off of the dam. “If you look carefully at the base, you can still occasionally find remnants of material,” Crivelli told me. Basically, you are welcome to climb the dam, but do so with the same respect you would any climbing area.

How to climb the Luzzone Dam

If you want to try to get your own first dam ascent, this is the beta you need. I’ve put together a mini guide to climbing the Luzzone Dam based on my own experience and research.

Seasonal access

You can climb the gym from May through October only. Unless you have Disney+ level production permits, winter ascents like Hemsworth’s are not possible nor recommended.

While I began my climb mid-day, if you’re climbing in the summer, I would recommend starting at an earlier time to avoid the sun.

Registering and cost to climb

To prevent unskilled climbers from attempting Luzzone, the route starts about 25 feet up the dam. A locked ladder accesses the start of the route. So you’ll need the key to the ladder to climb the route.

Each climber must pay 20 Swiss Francs (or $25 USD) and sign a waiver. Then you will be given a key to unlock the ladder at the base of the route. As of this summer, the location to pick up the key is no longer at the restaurant and has moved to a campsite 15 minutes from the dam itself. The current key pickup location (as of 2025) is the Polis Camping Bistro in Olivone (15 minutes away). The location is subject to change so be sure to check the confirmation email sent after booking online.

Note that there is a two-person minimum—yes, you need a partner. You’ll also need to pay a 100 Swiss Francs ($125 USD) refundable deposit that you get back when you return the key.

Luzzone climbing difficulty and time required

The route up Luzzone consists of five pitches, with the hardest pitch at the top: 5.10c. Expect long, consistent sequences on old-school plastic. Here’s the pitch-by-pitch grade breakdown:

- Pitch 1: 5.9

- Pitch 2: 5.10a

- Pitch 3: 5.10b

- Pitch 4: 5.10c

- Pitch 5: 5.10c

While simul-climbing the dam allowed Caroline and I to make pretty quick work of the climb, budget around two or three hours to climb the dam.

Luzzone gear list

An anchor for each pitch consists of two bolts with chains. There is a small ledge you can stand on at each belay.

Here’s the gear you’ll need to climb the route:

- Helmet (required)

- 14 quickdraws

- 50m twin ropes or a 70m rope

- Standard multi-pitch kit

Bailing: Don’t count on rappelling the entire wall. The top pitches are overhanging, making retreat (especially after the fourth pitch) complicated and sometimes impossible.

More tips for the climb

Parking and approach: There are two lots, one above and one below the dam. It’s less than a five-minute approach from the lower parking lot, and 20 minutes from the upper parking.

Guides: If you lack multi-pitch experience or want to toprope the Luzzone Dam route, you can book a guide through Ticino Alpine Guides Association.

More pointers:

- The dam is located in an Italian-speaking part of Switzerland, but people working in tourism will likely understand English.

- You can get a cappuccino or beer before (or after) your climb at Ristorante Luzzone. They also serve incredible food sourced from local farmers.

- Please show respect for the environment, the locals, and the route. Practice Leave No Trace and support locals.

The post The World’s Tallest Artificial Route Soars up a Dam. Here’s Your Guide to Climbing It. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

From Colorado to the Czech Republic, here are the climbing areas across the globe with the most sandbagged grades and, in some cases, R-rated vibes.

The post The World’s 13 Most-Sandbagged Climbing Areas, Ranked appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

As long as there’s been climbing, there’s been sandbagging. No, we don’t literally hit one another over the head with bags of sand to then rob each other like bandits. But we climbers do delight in giving routes implausibly stiff ratings or downplaying their seriousness. Sandbagging may result from an area being “old school,” with many routes graded when 5.9 or 5.10 topped the scale. Or it may simply be because the first ascensionist wanted to see their enemies fail.

Whatever the reason, knowing that a certain area is sandbagged ahead of time can help you prepare. You might choose routes below your limit, set out with a bigger rack, or bring some extra crashpads for a safer landing zone. Some might choose to avoid these areas altogether. And for the sandbagged sport climbing areas below, you won’t want to forget your stick clip. For the traveling rock climber, here are the 13 most-sandbagged areas around the world, ranked from least to most “hard for the grade.” We’ve also included the type of climbing predominant in each area, plus a wild card entry at the end of the list.

13. Eldorado Canyon, Colorado (trad)

Eldorado near Boulder is a storied traditional area, with many routes first freed or established back when 5.10 was the top end of the grading spectrum—thus its slew of stiff 5.9+ routes (e.g., the slimy, sure-feels-like-5.10 dihedral of The Green Spur). Extra spice comes in the form of long runouts, slick sandstone, manky pins, thin pro, weird moves on diagonalling holds, and horizontal bands of shattered purple choss criss-crossing the walls.

12. Céüse, France (sport)

Céüse may arguably offer the world’s best sport climbing, but it’s also unforgiving. The hike is a steep hour uphill, the upper half of the butte is treeless and sunbaked, and weather moves in quickly. (In 2022, a 23-year-old woman was struck unconscious by lightning while sitting below the route Bibendum.) What’s more, the routes don’t have “holiday grades”—in fact, they’re quite stiff—and the climbing is engagé: The spaced-out bolts usually, and cruelly, arrive right after the thin-pocket cruxes.

11. Dolomites, Italy (trad)

After Colorado climber Chris Weidner put down the classic West Face of Cima Grande—a V+ (5.7/5.8) established in 1913—he said it felt more like mid-5.10. From the ground, the crux Dulfer Corner looked so intimidating to Weidner and his climbing partner that both were certain they were below the wrong route. Many factors are at play in Dolomites’ sandbagging, notably the area’s venerable history, the pumpy, overhanging rock, the museum-relic fixed pitons, the fast-moving weather, and the friable limestone. In fact, the rock is so ill-reputed that when Alex Huber free-soloed the 500-meter Hasse-Brandler Direttissima (5.12a) on Cima Grande in 2002, he wore a helmet.

10. The Needles, South Dakota (trad/sport)

The fact that the Needles favors a ground-up ethic with bolting at stances or hanging on hooks comes through loud and clear in the climbing. Epitomizing this style: the 5.10 and 5.11 R/X climbs on the slender spires of the Ten Pins, and the thin, sporty face of Vertigo (5.11+ PG-13) in the Outlets. But the grades here are also feisty, exacerbated by the fact that the myriad quartz, feldspar, mica, and other crystals studding the granite are prone to snapping. This is quite alarming when you’re runout 20 leg-quaking feet. (Note: The Needles in California are also sandbagged, but at least the stone is perfect and there’s better protection—usually.)

9. Yosemite National Park, California (trad, bouldering, sport, multipitch, big walls)

It feels odd to list the area—along with Tahquitz/Suicide—where the Yosemite Decimal System was literally created as “sandbagged.” But most would agree that the Valley is stiff, perhaps because so many benchmarks are found here, from early 5.10s like the offwidth Ahab, to relatively newer-school testpieces like Beth Rodden’s 5.14c crack Meltdown. The splitters stretch forever, and the slabs come glacier-polished and runout. Moreover, an unwritten bouldering code meant that, for years, no FA could be harder than V12—a spell only recently broken with FAs like Carlo Traversi’s V16 The Dark Side.

8. Castle Hill/Flock Hill, New Zealand (bouldering)

The wind- and water-weathered limestone blocks on New Zealand’s South Island are an adventure-boulderer’s paradise, with a raw feel and limited documentation (try castelhillbasin.co.nz). For ages, the problems went ungraded. Now, even with V-grades, the ratings are stout. Quick-to-polish rock, spaced-out pockets, body-position-dependent sloping dishes, and dire, rounded-mantel topouts make the sandbagging even more dire.

7. Rifle Mountain Park, Colorado (sport)

Notoriously, Rifle has river-polished limestone glossed by three decades of traffic (“Grab the white spots; step on the black spots”). This is the land of unrelenting steeps and blocky, roofy, hard-to-read rock with few downpulling holds. But Rifle also succumbs to trickery, especially kneebars and kneescums—beta the locals will “crag-splain” from the road. According to these suspect locals, that impossible-feeling 5.12b is actually just a casual stroll, with 14 secret no-hands rests you somehow missed on your first go.

6. Shawagunks, New York (trad)

Climbers have been putting up routes in the ‘Gunks for a looong time, since the 1930s/1940s, starting with the climbing icons Fritz Weissner and Hans Kraus picking the plums, like High Exposure. The Gunks’ near-century of history has thus led to grade compression and especially heinous “plus” grades (5.8+, 5.9+, 5.10+). And it’s heckin’ pumpy, even on the moderates. The gently overhanging to massively roofy quartzite’s horizontal bedding forces you to hang off your arms to pro up the horizontal cracks.

5. Horse Pens 40, Alabama (bouldering)

HP 40 is known both for its slopers and stout ratings, epitomized by the slope-rassle Bumboy (V3). Also beware stiff problems like the aesthetic Skywalker (V8) and the high, committing arête of Mortal Kombat (V4). Michael Rosato, a onetime local who made the brilliant HP 40 homage EGODEATH, says the sandbagging is threefold in origin:

- The grooved, weathered sandstone dictates precise, hyper-positional movement.

- Inspired by the Fontainebleau ethic, Adam Henry, a driving force behind HP 40 purportedly only suggested a grade for his first ascents once he and/or other fellow early developers had repeated the climbs numerous times to optimize the beta.

- The ratings heavily factor in elusive “optimal conditions” in the warm, rainy South.

And there you have it.

4. Joshua Tree National Park, California (sport, trad, and bouldering)

At least J-Tree’s sandbagging is equal opportunity. The sport routes are stout (half the crimps fell off Desert Shield, originally given 5.13a, yet one guidebook still called it “5.12d”). The trad climbing is stressful, committing, and baggy (see the holdless, RP-protected stemming on the 5.11b Coarse and Buggy). And the bouldering will crush your soul (try the tips-eating patina crimps on the “V5” JBMFP, or the slappy crimps/seams of the John Bachar “V7” Pumping Monzonite).

3. Rochers de Freyr, Belgium (sport)

This diverse and storied limestone crag—its first documented FA was in 1930—with 700-plus routes on the River Meuse is Belgium’s crown jewel. It’s also the early proving grounds for the country’s superstars like Nico Favresse and Séan Villanueva-O’Driscoll. But Freyr is also well known for runouts, mirror-slick moderates, cryptic beta, and cranky grades. Famously, the “6c” (5.11b) Beau Gorges offered a bounty of a bottle of Champagne for anyone who could onsight—a prize not even Favresse was able to claim.

2. Index Town Walls, Washington (trad and sport)

The running joke about “Index 11b” holds more than a few grains of truth. Back in the 1980s, when 5.12 was still the upper end of the grading scale, the locals at this granite backwater were convinced they couldn’t climb that grade, leading to insane compression at 5.11. For the full Index “5.11” flavor, try the Lower Town Wall’s technical tips/pin-scar crack Iron Horse (5.11d, or 5.12c+ everywhere else on Earth). And find out why exactly this traditionally “gatekept” area has become more popular in recent years.

1. Elbsandstein in Dresden / Adršpach in the Czech Republic (trad/rings/jammed knots)

The strict ethics on these sandstone towers split by the international border of the Elbe River is legend:

- No nuts or cams (climbers use jammed knots and sling chockstones)

- No chalk or rosin

- The only sanctioned fixed pro is massive, half-inch-plus-diameter rings that must be drilled ground-up

The result: sweaty hands, terrifying runouts, and huge fall potential on sternly graded routes. If all that isn’t enough, you can also fill your days (and trousers) on the Czech side with tower jumping, linking spires with terrifying salti mortali.

*Runner Up: The MoonBoard

While a bit tongue-in-cheek, the MoonBoard is an “international venue” in the sense that these boards have existed worldwide since the mid-Aughties. Of the many versions of the board’s modern, light-up, app-interface hold sets, 2019 is considered the stoutest, followed by 2016, 2017, and 2024. On the MoonBoard, the ratings routinely feel two to four grades harder than commercial or outdoor boulders. The board’s creator, Ben Moon, actually calls the pre-app/-lights 2010 set the fiercest, with its 40 tendon-punishing School Room Originals. The tweaky yellow holds are so small, they’re barely substantial enough to serve as paperweights.

The post The World’s 13 Most-Sandbagged Climbing Areas, Ranked appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

I brought a group of Black climbers to Jamaica. When two locals stopped to watch—then asked to climb—it reminded me why visibility, joy, and belonging matter in the sport.

The post In Jamaica, I Watched Two Locals Try Climbing Because They Saw Themselves in Us appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Discovery Bay is where modern climbing in Jamaica began. Spanish climbers like Daniel Oury and later Juan Luis Toribio bolted the island’s first sport routes here, laying the foundation for what’s now a growing community.

Fifty-five sport routes ascend sharp, pocketed limestone, from gentle slabs to overhangs. When we arrived in Jamaica, Toribio, a leader in the local climbing scene, hadn’t visited the area in months, since he’d been busy bolting routes in India. So on our first day in the country, we made our way to St. Ann Parish, where Discovery Bay is located, to revisit a crag now partially reclaimed by nature.

The trail had become overgrown during Juan’s time away. We tiptoed through thick brush, slipped over loose rock, and bushwhacked our way forward. For many of us, this was our first glimpse of Jamaican rock—the start of something we’d spent months preparing for.

By “we,” I mean Clmbxr, the community I founded in 2019 to make climbing more accessible for Black and underrepresented communities. I never imagined my first trip to the Caribbean would come because of it. Ten individuals in the Clmbxr community signed up for something bigger than just climbing. This trip would be a mix of culture, coastlines and crags—a retreat rooted in movement and meaning. Although, if I’m honest, I know a few of us came for the vibes. It is, after all, Jamaica.

To make the trip happen, we partnered with Toribio, founder of JamRock Climbing. He’s been leading the charge to grow the Jamaican scene. In 2023, he launched @Jamrockclimbing and a WhatsApp group—now nearly 80 members strong—to raise visibility and bring locals into the fold. When I approached him about collaborating, we talked about building on the work already being done. Just last year, he filmed a project with Kai Lightner, amplifying the scene’s potential.

During our first day at Discovery Bay, the Caribbean sun beamed down on us, heat clinging to our backs like a second layer. The air was thick with humidity. Every movement left your fingers sweaty, your body drenched.

Still, there was magic in it. From the top of the wall, the turquoise ocean stretched past the tree line. It felt like being let in on a secret. We weren’t just visiting Jamaica—we were seeing it from a vantage point few ever do.

For some of the newer climbers in our group, that first 6a (5.10a) route represented a milestone. The rock felt razor sharp, the route stretched 35 meters up, and the third clip came just after a sketchy sequence that tested nerves and footwork. One climber came down after sending, eyes wide and adrenaline still buzzing. “I didn’t think I could do that,” they whispered, half-laughing, half-crying. That’s what climbing does—especially when you’re surrounded by people who look like you, who cheer you on, who believe in you even when you’re doubting yourself.

After a sweaty goodbye to Coral Spring, where we’d rented our Airbnb just 20 minutes from Discovery Bay, we headed east to Kingston. The 2.5-hour drive gave us time to swap playlists, nap in the backseat, and watch the coastline shift from wild beaches to bustling city streets. We checked into RaggaMuffin Hostel, dropped our bags, and enjoyed cold Red Bulls before rushing out to the Bob Marley Museum.

The tour walked us through the bones of Marley’s life—his studio, his family spaces, and the scars of the past still visible on the walls. You could feel the tension between struggle and peace. It didn’t feel unrelated to what we’d been doing on rock all week, moving through difficulty, trying to find our rhythm.

That’s when we learned about our next crag: Cane River Falls. Legend says it’s where Bob washed his locks. In the song “Trench Town,” he sang, “Up a Cane River to wash my dread…” In Rastafari, water isn’t just cleansing—it’s sacred. Water serves as a symbol of purification, of connection to Jah. For Bob, washing his locks here wasn’t hygiene—it was ritual.

Tucked just outside Kingston, Cane River Falls is owned by a local woman named Mona. You follow a winding path until you’re met with the cool rush of cascading water. It’s part crag, part waterfall, part sanctuary.

Climbing there felt surreal. One moment we were gripping pockets and clipping quickdraws. The next, we were diving into the water, laughing, catching our breath. It was humid, wild, and deeply Jamaican. The kind of place that makes you question whether going home is really necessary.

As we climbed, a group of locals wandered past and paused, eyes fixed on the wall. One of them stood watching me and Takiyah, one of the strongest climbers in our group, as we worked our way up a 6b (5.10c). Eventually, without saying much, two of the local Jamaicans asked if they could try. We didn’t catch names—they just slipped into harnesses, headed up the rock barefoot, and gave it a go.

That moment stuck with me. They didn’t ask if they needed climbing shoes. They didn’t question whether they belonged on the wall. They just moved. It reminded me that climbing is instinctual, something your body understands before your brain catches up. That right there is what we mean when we say representation matters.

For 10 days, we climbed, connected, and carved out space on the rock. In doing so, we reminded ourselves and others: We belong here, too. Not as guests or outsiders, but as part of the landscape and the future of climbing. Jamaica gave us more than just routes—it gave us rhythm, grounding, and a new horizon to dream from.

The post In Jamaica, I Watched Two Locals Try Climbing Because They Saw Themselves in Us appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

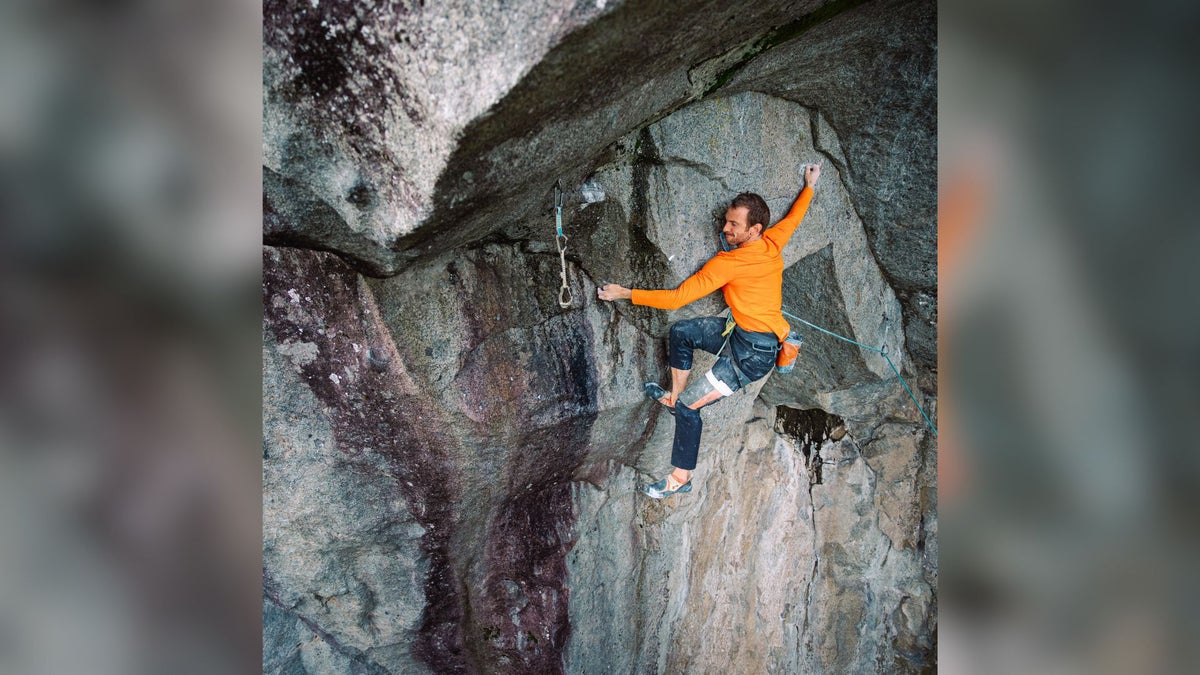

Most PNW climbers beeline to Squamish on weekends. But quiet options (with impeccable stone) exist nearby

The post Skip the Weekend Crowds in Squamish. Try This Nearby Bouldering Paradise Instead. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Like many people who come to southwestern British Columbia, Denis Langlois wanted to climb in Squamish. It didn’t matter that, when he moved from Montreal to Canada’s westernmost province, he landed in the rural farming community of Agassiz, nearly two hundred miles from Squamish’s towering granite walls. On weekends, Langlois would load up his car and wait in stop-and-go city traffic for hours, making regular pilgrimages to Canada’s climbing mecca. Until he discovered the Fraser Canyon.

Located a short distance northeast of Langlois’s home, the Fraser Canyon is a deep chasm stretching from Lillooet to Hope, BC. Carved by one of western Canada’s most iconic rivers, the canyon starts on the dry, sagebrush interior plateau and ends in temperate coastal rainforest. It’s a region steeped in history, from Indigenous peoples to the fur trade, gold rush to the birth of Canada as a nation.

Driving through the Fraser Canyon feels like going back in time. Heading north from Hope—where Rambo: First Blood was famously shot—the road is lined with old motels, shuttered restaurants, and tourist attractions from a bygone era. But off the road, on the banks of the mighty Fraser, Langlois and a group of friends unearthed a new bouldering paradise.

The first boulder

A mind-numbing work commute can be thanked for Langlois’s curiosity about the canyon. He frequently drove two and a half hours from his home in Agassiz to dairy farms up the canyon, helping farmers use new technology on their land. As he drove, his eyes wandered from the blacktop pavement towards the forests and shoreline. He caught glimpses of boulders protruding from sandy beaches and mossy cliffs hidden in thick vegetation.

A few days before Christmas 2020, Langlois was headed home from a family sightseeing trip when his curiosity boiled over. He pulled off the highway, thanked his wife for staying with the kids, hopped over a concrete barrier, and bushwhacked to the base of a house-sized boulder. He found one side with a clean 45-degree wall that looked like a natural Kilter Board. Unfortunately, it lacked the Kilter Board’s jugs, so he contoured around the massive boulder and discovered a cave with holds on the other side. This one boulder convinced him of the area’s potential. He returned several times that January and February, despite heavy coastal rain, to start building a trail. By the end of February the Fraser Canyon’s monsoon season began to taper, and he finally got to climb on the giant highway-side boulder. Langlois told a few friends about what he was up to. Most of them gave a polite, absent smile—likely thinking of their project in Squamish—and then gently declined his invitations to drive up the canyon. Eventually, his persistence paid off when he convinced a few local buddies to come out for a day.

Gold Beach

By the end of that first summer, Langlois’s small crew was clearing trails, scrubbing moss, and establishing problems from beginner friendly V1s to stout V10s. One hot day, one developer walked down to the river’s edge and noticed the water level was way down, exposing a cluster of semi-truck-sized boulders nestled on a white beach of soft, fine-grained sand. They named the area Gold Beach and spent the rest of the day establishing instant classics including Beauty and the Beach (V6), an airy prow that ascends one of the massive boulders deposited by the mighty Fraser. “We were like kids in the sandbox,” Langlois recalled.

The potential for climbing in the Fraser Canyon seemed nearly endless to Langlois. But if he was going to keep climbing and developing, he wanted to make sure it was happening in the right way. “Early on I did a property search to try and find out if [the boulders] were on private or crown land. That’s when I found out it’s all native land,” said Langlois. Specifically, the boulders were on the lands of the Spuzzum and Yale First Nations. Neither nation had a public contact for land management, so Langlois eventually showed up at the band office to ask for permission to climb in the area. He met with the chiefs of the two nations who were happy to see climbers enjoying their land. “[They] said, if you’re cleaning the boulders and taking the moss off, just put some tobacco down and say thanks to the land for giving you the ability to play there,” Langlois explained.

A push for outdoor recreation

In May 2023, the Spuzzum Nation submitted a proposal to build a new all-season mountain resort in a sub-range of the North Cascades above the Fraser Canyon. According to the Nation’s proposal, the South Anderson Resort would serve 9,000 skiers a day in the winter and provide a range of summer recreational activities, including climbing.

The Spuzzum Nation’s proposal says the resort will bring in visitors, create jobs, and support “recreation opportunities in the Cascade Mountains in an environmentally sustainable and responsible manner.” This plan is one piece of a larger strategy using outdoor recreation to revive the Fraser Canyon’s struggling tourist economy.

Up until the 1980s, the Fraser Canyon was the only major highway connecting southwestern British Columbia to the rest of Canada. The canyon hosted a booming tourist economy with travelers frequenting restaurants, motels, and other tourist traps up and down the canyon. But in 1986, BC opened the Coquihalla Highway, a more direct route that shaved hours off the drive. A story in Canadian Biker compared the Fraser Canyon to America’s Route 66 after the construction of the Interstate Highway system, noting scenes of “abandoned motels…hotels, and gas stations surrounded by tumbleweeds and sporting rusted signs—the stuff of broken dreams and economic ruin.”

Locals hope that outdoor recreation can revitalize the region and fuel a new, sustainable economy. According to a 2019 study published by the Fraser Valley Regional District, outdoor recreation contributes $1.52 billion annually to the broader regional economy, supporting 10,262 jobs. Unfortunately for the Fraser Canyon, most of that economic impact is happening closer to the more popular, outdoorsy towns of Hope and Chilliwack. “While outdoor recreation is growing, the development has been slower in the Fraser Canyon,” Sam Waddington, owner of the local gear shop Mt. Waddington Outdoors, explained. “To any of us who spend time in that corridor, it’s hard to understand why, because it is spectacularly beautiful.”

Sharing the canyon

Initially, Langlois was hesitant about promoting his work in the Fraser Canyon. He was all too familiar with the crowded crags, lineups at boulders, and the trash and trampled vegetation that followed the climbing crowds in Squamish. He also recognized that without more climbers, all his work developing and maintaining could be for naught. “Route developers put in a ton of effort to clean, bolt, and set up an area—only to see it reclaimed by the forest when it wasn’t used enough,” explained Waddington, also a founding member of the Fraser Valley Climbing Society.

It was a familiar experience to Langlois who, during his first trip to the local Harrison Bluffs, spent the day “bushwhacking around alder and blackberry bushes” just to get to some of the area’s most popular routes. Not wanting to see his own hard work go to waste, Langlois eventually decided to upload beta about the area to Mountain Project and Kaya. He also enlisted Jesse Wheeler to help make a film about the area. The result was a 30-minute doc called Gold Rush, which features Langlois and the rest of the developers bouldering on the canyon’s premium granite blocks, as well as the area’s roots with Indigenous singing, drumming, and dance.

A new Squamish?

So far, Langlois hasn’t seen a horde of new climbers descend on the Fraser Canyon. Even with everything it has to offer, he still sees most climbers, including a lot of Fraser Valley locals, head to Squamish. This traffic is something that Sam Waddington, who operates gear shops in both the Fraser Valley and Sea to Sky region—the area north of Vancouver that stretches from Squamish to beyond Whistler—thinks could be about to change. “In Squamish, they’re building new crags to try and spread out the crowds, while here, developers are trying to entice people to come climb out here,” he explained. “I think the bouldering, especially around Hope and the Fraser Canyon, has the potential to be some of the best anywhere.”

Waddington is also quick to point out that the Fraser Valley is already home to some iconic climbing. The Northeast Buttress of Slesse Peak, an iconic fang of rock in the Chilliwack River Valley, is written up in the Fifty Classic Climbs of North America. The late Marc-André Leclerc, whose image hangs behind the till at Waddington’s Chilliwack shop, grew up in Agassiz and established and soloed all types of ambitious routes in the region. The Chinese Puzzle Wall, which both he and Brette Harrington put up an impressive first ascent on, is just one valley over from Slesse.

But the Fraser Valley is still far from being a true competitor to Squamish’s bouldering scene. The Fraser Valley Climbing Guide (2023) comes in at just over 100 pages—roughly a quarter of the size of either Squamish Select or Squamish Bouldering. Waddington argues this low number simply means the Fraser Valley has plenty of new-routing potential. Given the high cost of living in Squamish and crowding at popular climbs, he thinks that people are already looking for other places to explore. “We have the climbing society, we have a local gym getting more people climbing, we have a local guidebook, and we have folks like Denis finding these cool new areas,” he said. “I’m feeling stoked about the future.”

How to climb in the Fraser Valley and Fraser Canyon

Where to fly

- Fly into the region directly to Abbotsford airport, or into Vancouver. Driving from Vancouver to the Fraser Valley take between one-and-a-half to three hours depending on where you’re headed.

Where to stay

- Hope and Chilliwack offer the closest accommodation to the climbing areas, from hotels to private and provincial park campgrounds Check out BC Parks and Recreation Sites and Trails BC for all options.

Climbing beta

- Beta for the entire region can be found in the Fraser Valley Climbing Guide, available online or at shops like Mt. Waddington Outdoors in Chilliwack and Valhalla Pure in Abbotsford. Online beta can be found on Mountain Project and, for the 82 listed problems in the Fraser Canyon, on Kaya.

Rainy day activities

- Project Climbing has two gyms in the area, one in Abbotsford and a bouldering gym along the Chilliwack River.

- Land Cafe and Studio next door to the Chilliwack gym has great coffee and rest-day yoga.

Tread lightly

Make sure to practice Leave No Trace ethics at all climbing areas in the region, especially regarding human waste. Some areas in the Fraser Canyon are located near traditional fishing areas and other important cultural places. Respect the Indigenous nations whose land these climbs are established on. You can donate to the Fraser Valley Climbing Society to help with local stewardship and development projects.

The post Skip the Weekend Crowds in Squamish. Try This Nearby Bouldering Paradise Instead. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Crags and bouldering areas hidden in America's concrete jungle

The post 9 Cities With Surprisingly Good Climbing Less Than 45 Minutes Away appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Think there’s no outdoor climbing near your city? Think again. Across the U.S., climbers in unexpected metro areas have carved out surprisingly solid places to send. Urban climbers scramble up graffiti-covered bridge abutments, link up post-work topropes, and preserve sandstone faces from development.

Of course, these aren’t world-class destinations—but they’re accessible, quirky, and worth checking out. These zones may be scrappy, but they’ve become cultural hubs, local proving grounds, and sometimes even launchpads for bigger goals. Here are nine U.S. cities where outdoor climbing exists surprisingly close to downtown—often within a quick Uber or bike ride.

Washington, DC

Washington, DC

Crag: Carderock

- Distance from downtown: 12 miles / ~25 minutes

- Approach: Park at the north lot in Carderock Recreation Area, then follow the riverside trail west to the cliffs (~5-10 mins)

- Number of Routes: ~140 (mostly toprope, some trad and bouldering)

- Type of Climbing: Schist face climbing and technical bouldering

- Grade Range: 5.3-5.12, V2-V7

Why Carderock is cool: Carderock isn’t just D.C.’s local crag—it’s one of the most historically significant climbing areas on the East Coast. Nestled along the Potomac in the C&O Canal National Historical Park, the area’s clean gray schist and white quartz crystals have hosted generations of climbers, from mid-century pioneers to weekend gym escapees.

The cliff band rarely tops 40 feet, but the real challenge is in the footwork—delicate smears, micro edges, and high steps. Most routes are toproped using tree anchors, though a few lines go on gear. Bouldering also exists, tucked around Jungle Cliffs and Hades Heights. On weekdays, it can be a peaceful forest escape—until a jet flies overhead on approach to Reagan National Airport.

More info: Potomac Mountain Club

Atlanta, GA

Atlanta, GA

Crag: Boat Rock & Chattahoochee River Corridor

- Distance from downtown: 12-25 miles / ~20-30 minutes

- Approach: Varies by area; most accessible via short hikes from public parks or trailheads

- Number of Routes: ~200+ boulder problems, 50+ toprope and trad routes

- Type of Climbing: Granite bouldering and short trad/toprope faces

- Grade Range: V2–V8+, 5.7–5.12

Why Boat Rock and Chattahoochee are cool: Granite slabs hide in Atlanta’s wooded pockets, from the preserved boulders at Boat Rock to the riverine corridors of Allenbrook and Island Ford. Boat Rock’s low, techy bouldering is famously unforgiving—demanding balance, footwork, and a tolerance for pad math. The climbing scene thrives on volunteerism and local advocacy, turning limited terrain into a deeply local culture built on effort and access.

More info: Southeastern Climbers Coalition – Boat Rock

Charlotte, NC

Charlotte, NC

Crag: Crowders Mountain

- Distance from downtown: 30 miles / ~35 minutes

- Approach: 20-minute hike from Linwood Road access

- Number of Routes: ~175 roped routes and hillside bouldering

- Type of Climbing: Quartzite face climbing and bouldering

- Grade Range: 5.6-5.13; V0-V8

Why Crowders is cool: Crowders has been the first real rock experience for many climbers raised in the Southeast. Steep, sun-baked quartzite routes demand technical movement, and basic anchor knowledge often enables a top rope setup when leading is not an option. A grassroots bouldering scene is also emerging among hillside blocks. Consistent local stewardship keeps the area accessible and evolving.

More info: Carolina Climbing Coalition – Crowders Mountain

Cleveland, OH

Cleveland, OH

Crag: Whipp’s Ledges

- Distance from downtown: 25 miles / ~35 minutes

- Approach: 5-10 minute walk from Hinckley Reservation parking lots in Cleveland Metroparks

- Number of Routes: ~100 toprope and trad routes, ~60 boulder problems

- Type of Climbing: Sharon Conglomerate sandstone—face climbing, horizontal breaks, and sloped crack systems

- Grade Range: 5.4-5.12; V0-V8

Why Whipp’s is cool: Whipp’s Ledges sits in the mossy ravines of Hinckley Reservation, offering short sandstone walls with horizontal breaks and slopey holds. The ethics here are traditional: long webbing, tree anchors, and minimal chalk. While modest in stature, the ledges offer plenty of challenge, particularly for those working on footwork and rope systems. For many Ohio climbers, this is where skills get sharpened before heading to the New or Red.

More info: Ohio Climbers Coalition

Minneapolis, MN

Minneapolis, MN

Crag: Taylors Falls – Interstate State Park

- Distance from downtown: 39 miles / ~45 minutes

- Approach: Easy 5-10 minute walk from parking areas within the park

- Number of Routes: ~200 routes (85 toprope, 66 trad, 118 boulders)

- Type of Climbing: Basalt columns—think vertical cracks, blocky faces, and pocketed overhangs

- Grade Range: 5.4-5.12; V0-V11

Why Taylors Falls is cool: Taylors Falls feels more remote than it is. Stacked basalt columns rise above the St. Croix River in a setting that looks pulled from the Northwest. There’s no sport bolting here; Minnesota state parks encourage clean climbing ethics. Climbers sling trees, jam cracks, and set long toprope anchors in the piney shade. With nearly 370,000 visitors a year, it’s one of the most trafficked climbing areas in the Midwest—and a true proving ground..

More info: Minnesota Climbers Association

St. Louis, MO

St. Louis, MO

Crag: Rockwoods Reservation Conservation Area

- Distance from downtown: 25 miles / ~30–35 minutes

- Approach: ~1/4 mile hike up a nature trail from West Christy Road

- Number of Routes: ~20 total (15 bolted sport, 4 boulders, 1 seasonal ice route)

- Type of Climbing: Short sandstone sport routes, featured boulders

- Grade Range: 5.7-5.12; V2-V6

Why Rockwoods is cool: Tucked into a quiet corner of Missouri oak forest, Rockwoods Reservation is the closest true outdoor climbing area to St. Louis—and it’s undergone a quiet renaissance. Originally a toprope zone, it’s now home to a growing selection of short, well-bolted sport lines, thanks to the efforts of BETA Fund and the Missouri Department of Conservation. Greensfelder Park lies just west of Rockwoods and offers hiking and mountain bike trails rather than roped climbing—but it adds a nice crossover option for multisport days.

More info: BETA Fund

Chicago, IL

Chicago, IL

Crag: Henry C. Palmisano Nature Park (plus scattered buildering citywide)

- Distance from downtown: ~4.5 miles / ~15–20 minutes

- Approach: Park at 29th & Halsted; walk 2–3 minutes to the boulders

- Number of Routes: ~25 modern boulder problems at Palmisano; ~100+ buildering and DIY problems scattered citywide

- Type of Climbing: Artificial boulders, preserved dolomite quarry walls, and urban concrete features

- Grade Range: V2-V6+

Why Palmisano Park cool: Most Chicago climbers head for the Red when they can, but Palmisano Park offers a legit local option. Once a limestone quarry and landfill, it was transformed into a 26-acre climbing park through a partnership between The North Face and Trust for Public Land. The community provided input to help co-design the sculpted boulders, which sit just minutes from the Loop.

Scattered buildering at Montrose Beach, Steelworkers Park, and university slabs round out the scene. It’s not glamorous—but it’s grassroots, accessible, and entirely Chicago.

More info: Palmisano Project – Trust for Public Land

Richmond, VA

Richmond, VA

Crag: Belle Isle and Greater Richmond Boulders (Buttermilks, Forest Hill, Manchester Wall)

- Distance from downtown: 0-5 miles / 5-20 minutes

- Approach: Varies—most areas are within walking distance or a short drive from city center

- Number of Routes: ~270 boulder problems and ~100 roped routes across multiple in-city parks

- Type of Climbing: Granite and quarried rock—slabs, faces, cracks, and traverses

- Grade Range: V0-V10; 5.6-5.12

Why Belle Isle and the Greater Richmond Boulders are cool: Richmond might be the most unexpectedly stacked city on this list. The James River Park System runs right through downtown, with granite boulders at Belle Isle, a bolted cliff band at Manchester Wall, and dense circuits in Forest Hill and the Richmond Buttermilks. Most locals treat the entire trail-linked network as their home gym, flowing between bouldering, paddling, and climbing—sometimes all in the same day.

Community stewardship is strong here, with trail days, meetups, and fresh chalk in every neighborhood. It’s an urban climbing ecosystem hiding in plain sight.

More info: James River Park Climbing

The post 9 Cities With Surprisingly Good Climbing Less Than 45 Minutes Away appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Index, Washington, has all sorts of tight-lipped lore, some of it deserved. But modern route developers are changing its tone.

The post Why America’s “Most Gatekept” Climbing Area is Becoming More Popular appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

If you’ve heard anything about the climbing in Index, Washington, you’ve probably heard that it’s hard. The strongest person you know raves about it; the hardwomen you met bivying in the boulders behind Camp 4 head there as soon as Yosemite gets too hot. Alex Honnold says it’s home to the world’s hardest 5.11d, Natural Log Cabin. (And that’s not even the hardest 11d there!)

But some of Index’s strongest locals are at the forefront of efforts to make the area more accessible, too. They are establishing moderate routes, making the area easier to navigate with signs and guidebooks, and working to develop an amicable relationship between transient climbers and local residents. Stamati Anagnostou—a member of the Index Climbers’ Coalition, a visionary route developer, and the author of one of Index’s hardest gear lines, The Quad Crack (5.14a)—is leading the way.

Anagnostou, who began climbing in Index in 2014, embodies the imperative to try hard but stay humble. When I first met him at the base of Godzilla (5.9), one of the Lower Town Wall’s most popular routes, he cut an unsuspecting figure in faded black skinny jeans and a floral button-down. We got to chatting—Anagnostou never seems to tire of meeting visitors to his home crag—and I was surprised when he grinned with recognition at my mention of Endless Skies (5.12d), a seldom-repeated sport climb located two pitches up in an overgrown corner of the Upper Walls. I asked if he’d been on the route. He said yes, but didn’t elaborate. Later, scouring the internet for beta, I’d recognize his name on the route’s Mountain Project page. He had equipped the route and competed with Michal Rynkiewicz for the first ascent.

Anagnostou doesn’t just surround himself with 5.14 crushers and longtime locals. Eager to learn about my progress on his obscure route, he invited me and a few friends to his house for dinner. He’s lived in the 150-person hamlet of Index since 2023, and the four-room clapboard bungalow he shares with his partner, Huck, is furnished cozily in greens and browns. He’s a generous dinner host, tall and rangy in the galley kitchen. He has a high-pitched staccato laugh that erupts easily and doesn’t match his slow, considered way of speaking. He’s passionate about this town: he writes for the local newspaper; he and Huck run community clean-up events; they’ve established a climbers’ collective who help organize an annual climbing festival. Whenever he isn’t climbing, it seems, he’s thinking about ways to preserve his beloved climbing area.

Locals—especially people who have spent their whole lives in Index, or whose families have lived there for generations—are often skeptical of visitors, and Anagnostou can’t blame them. It’s hard to sympathize with the tourists who vandalize the public restrooms, spray paint trees on the UTW trails, or speed down Index Avenue to beat the traffic on Highway 2. Locals are also wary of alien opportunists looking to buy up the town’s very limited housing and develop short-term rentals, driving up the cost of living and stifling the growth of a local community. Understandably, many of Index’s residents want to see a benefit from the uptick in tourism, which has exploded in part due to the publication of a climbing guidebook in 2017 and the publicity that Index climbing has received in publications like this one. So when locals have felt like visitors are offering little to the area except for the graffiti and litter they leave behind, discontent has boiled into yelling matches at town council meetings.

In Index’s early days, “developers balked at grading their routes 5.12 for fear of getting downgraded,” Anagnostou says. Anything hard got 11+, and many of those grades haven’t changed to meet contemporary standards. (The 5.12s, 13s, and 14s are graded a bit more honestly.) So if you come to Index to chase grades, you might be sorely disappointed.

This sandbagging, Anagnostou reasons, might contribute to Index climbers’ reputation for gatekeeping. Not to mention that neither the climbing style nor the environment lend themselves to successful short trips. During the drier months, May through July, it rains about every two days. You might find your project covered in fast-growing moss that takes days to scrub off. And you’ll need to get used to trusting smeary feet on the fine-grained granite. So, on the rare days when the weather is good and the walls are dry—the theory goes—perhaps the locals are a little crankier about sharing the crag than their neighbors in, say, Squamish or Smith Rock.

Even so, climbers have flocked to Index as word has gotten out about the area’s dreamy high-friction granite, and Anagnostou welcomes the area’s growing popularity with more sincerity than I’d expected. He sees growth as an engine for route development and attention from conservation groups that might help protect local climbing. “Engagement drives conservation, and there are so many people doing work to further climbing in Index [right now].” Index climbers’ reputation for gatekeeping, he says, is dated and overblown: “I don’t think we really ever experienced the thing of Index being hush-hush.” Instead, the close-knit community he found there in 2014 welcomed him quickly.

Anagnostou may very well benefit from the “strong-climber effect”—those pushing hard grades, or developing new routes (especially if they’re men, and white), are usually welcomed into established climbing communities pretty quickly, even small communities in out-of-the-way areas. What about everyone else?

I can weigh in on the ordinary Index climber’s experience here. My credentials? I’m pretty solid around 5.10 on gear, and I project bolted 12s. My footwork is underdeveloped after years of climbing in the gym and on sandstone, and I start to panic when my last piece is about knee-high. I am also a woman, who usually travels alone, which means I don’t necessarily “fit” into male-dominated climbing areas—and I certainly don’t blow everyone away with my climbing prowess. Usually, I have to make a focused effort to find community when I arrive in a new place.