Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

This guide is for climbers who want to embrace more sustainable approaches to their vertical adventures. By exploring the emerging ecopoint movement, we provide both the philosophical foundation and practical tools you need to reduce your carbon footprint while pursuing your climbing dreams.

We also take a look at some high-profile sustainable climbing initiatives, including last fall’s The Devil’s Climb, to show how ecopoint intentions don’t always translate to positive environmental action.

Ultimately, this guide will help you join the growing community of climbers worldwide making sustainability a priority on and off the wall. Note that all destinations listed below include specific crags accessible without a car.

Redpoint, greenpoint … ecopoint?

It all started when climber Kurt Albert originally coined the term Rotpunkt (redpoint) in the mid-1970s in Frankenjura, Germany.

As a playful nod to the redpoint (Rotpunkt) movement in sport climbing, German climbers coined the term Grünpunkt (greenpoint) to describe an initial free ascent on a bolted sport climb, relying solely on trad gear. The goal was to celebrate climbing approaches that minimized permanent impact on the rock.

In Germany, in 2021, climbers Lena Marie Müller and Sofie Paulus introduced a new style of sending: Ecopointing. After Müller completed Austria’s challenging trad route Prinzip Hoffnung (5.13d/5.14a) with an approach that included only public transportation in 2020, she decided to formalize a sustainable mode of climbing.

Rooted in Frankenjura, ecopointing focuses specifically on sustainable ways of getting to a climbing area, i.e., by biking and/or taking public transportation. But over time, the Ecopoint Frankenjura movement has evolved. Paulus, along with volunteers, have designed an ecopoint guidebook. They also facilitate community get-togethers and regularly update bike-to-climb routes on Komoot (a route-planning software). Ultimately, Paulus has written that ecopointing shouldn’t be viewed as a sacrifice. For her, it “simultaneously prolongs the experience of climbing outdoors” making it feel “more intense and richer.”

Footprints and footsteps: Pro climber ecopointing compared

Since the ecopoint movement got its start in Germany, the ethic has spread and been adopted by pro climbers in several high-profile instances. The most publicized, perhaps, took place In the summer of 2023, when Tommy Caldwell and Alex Honnold embarked on a 2,600-mile journey from Colorado to Alaska. They combined biking, hiking, and sailing to reach and then climb the Devil’s Thumb, a formidable granite monolith in the Tongass National Forest. Their adventure was chronicled in National Geographic‘s documentary The Devil’s Climb (released October 2024).

But was the Devil’s Climb project and production a true ecopoint, as Caldwell and Honnold had intended it to be? Climbing Magazine Senior Editor Anthony Walsh happened to be climbing in the Bugaboos during the shoot. “I witnessed near-constant helicopter flights ferrying supplies, support-crew members, and filmmakers around the range,” Walsh recalls. He also says that while Honnold and Caldwell were walking in to satisfy the ecopoint guidelines, their climbing gear was flown in to each campsite. Whether those decisions were made by the climbers or by the massive production company, it resulted in what was likely a high-carbon footprint expedition rather than a pure ecopoint mission.

Biking or public transit aren’t the only lower-impact ways to reach a climbing objective. Belgian climbers have pioneered the sail-to-climb expedition. In 2010, Sean Villanueva O’Driscoll, the Favresse brothers, and the photographer Ben Ditto sailed to Greenland—training on a hangboard en route—to pursue some Arctic big wall climbing.

Following in their footsteps, Belgian Seb Berthe crossed the Atlantic twice by sailboat to attempt Yosemite’s Dawn Wall, first in 2022, and again in 2025. After his initial Dawn Wall attempt fell short, Berthe’s persistence paid off. This past winter, he and his partner Soline Kentzel repeated the sailing ecopoint adventure, staying fit on the boat’s hangboard along the way. Finally, on January 31, 2025, after 50 days at sea, 30 days of land travel, and 14 days on the wall, Berthe achieved his goal of the fourth free ascent of El Cap’s Dawn Wall.

Adventure reimagined: Focus on the journey

Ecopoint inspiration can be found beyond the good (and not so good) examples established by the pros. Following in the footsteps of Paulus and Müller, Adele Zaini—an Italian climber, climate researcher, and activist—stresses the importance of a mindset shift among the climbing community. “The attitude behind bike-to-climb,” says Zaini, “should be to challenge the ordinary approach, break the mold and get creative: find your own way to make it the new cool!”

She suggests finding inspiration in the new ecopoint projects blossoming around the world, joining the movement, and creating a sense of community, in part by leveraging the power of social media.

However noble the motivation of reducing one’s footprint, in the long run, bike-to-climb is not sustainable without a mindset shift. It is therefore essential to redefine performance and adventure. “An adventure that starts from your front door will enrich your experience in ways you can’t even imagine. Until you first try … and get addicted!” says Zaini.

Over the years, she has bagged several bike-to-climb adventures. She’s pedaled and climbed her way from Innsbruck, Austria, to Venice, Italy. And she’s biked across Norway’s Lofoten Islands, linking up multipitch trad climbs. Today, she lives in Oslo, Norway, and bike-to-climb is her favorite way to reach the crag. The train ride and bike ride combined take her less than an hour to reach her nearest climbing area.

Bike-to-climb: A beginner’s guide

For successful bike-to-climb adventures, the first step is figuring out how to load your climbing gear onto your bike. Proper weight distribution is crucial. Prioritize weight on the front of your bike for better handling and stability, especially on varied terrain. Many climbers invest in quality panniers to carry gear without affecting balance.

Choose your bike according to the terrain you’ll encounter on the way to the crag. Road bikes work well for long, paved approaches and can handle light gravel, while gravel bikes offer versatility for mixed surfaces with their wider tires with better traction, as well as more relaxed geometry. For technical trails or rougher terrain leading to more remote crags, a hardtail mountain bike provides the necessary stability and control, while still maintaining efficiency for longer rides.

Ideally, look for a bike rack at the crag parking area to securely lock up your bike. If none exists, don’t worry! You can safely secure your bike to a sturdy tree near the trailhead, being careful not to damage any vegetation or block hiking paths.

Boulderers face unique challenges, but have found solutions through specialized inflatable crashpads or small trailers towed behind the bike. If possible, avoid backpacks or any significant weight on your back when pedaling whenever possible—your shoulders will thank you when you finally reach the rock and are ready to climb.

“If you want to become a real bike-to-climber, don’t underestimate the right features in your bike,” suggests Zaini. “But don’t get caught up either in the ultralight equipment obsession that can take the joy out of the experience. This is definitely not an essential requirement to getting started.”

Additionally, Zaini highlights how biking to the crag should not be seen as a sacrifice, but as an opportunity. Slow down whenever possible, admire landscapes in good company, let time fly by—this mindful approach allows you to experience things you’d miss while driving. “The summit shouldn’t be your only goal,” she emphasizes. “Make it about the entire journey, not just the climbing destination.”

Lastly, when it comes to safety and preparedness, you might have to double up on helmets. If you’ll be pedaling along busy road shoulders or tough terrain where a fall is possible or even likely, you’ll want to wear a purpose-built bike helmet. You can strap your climbing helmet to the outside of your pack. And don’t forget to bring your repair tools and pump—nothing ends a bike-to-climb day faster than mechanical issues that leave you stuck at the crag or keep you from getting there in the first place.

Top ecopoint climbing destinations

Boulder, Colorado

To access Eldorado Canyon (mostly 5.4-5.14 trad and sport routes), cyclists can follow Broadway south, continuing onto Marshall Road for a scenic 10-mile ride. Prefer something closer? The iconic Flatirons (with everything from fourth-class scrambling to 5.14) stand just two miles from downtown via Chautauqua Park—perfectly suited for a half-day adventure without the parking hassle. Boulder Canyon offers another excellent option, with crags like Elephant Buttresses and The Dome accessible by pedaling a few miles along the paved Boulder Creek Path.

Squamish, British Columbia

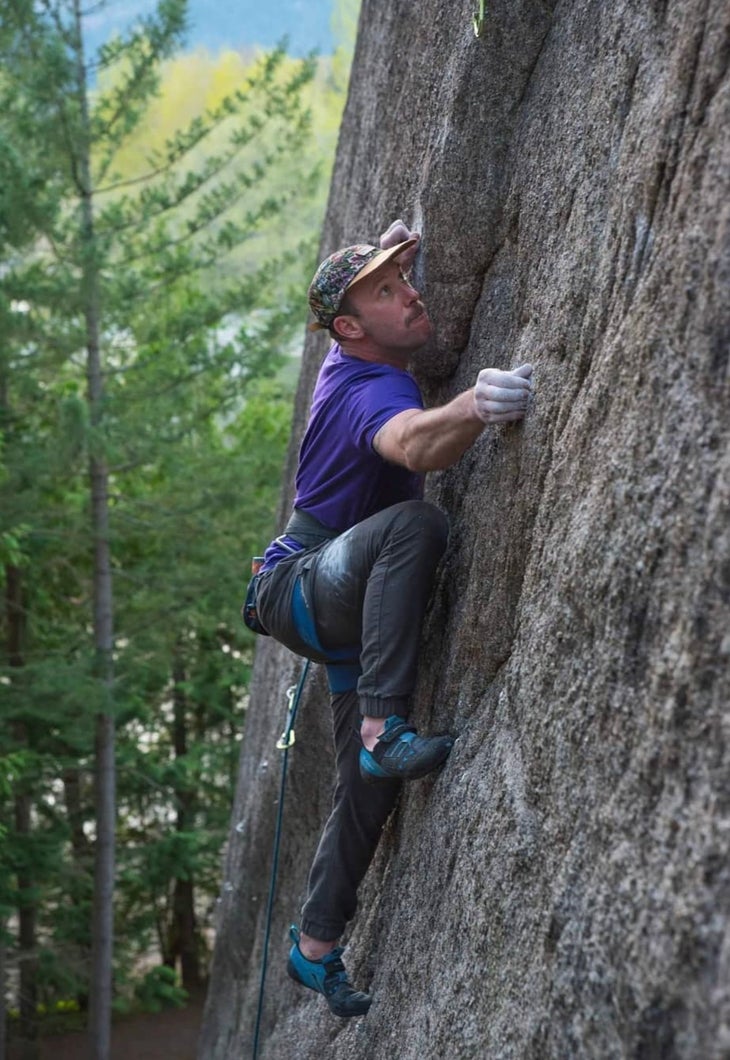

With its compact layout, Squamish delivers perhaps the ultimate bike-to-climb experience in North America. By bike, the popular Smoke Bluffs area (mostly 5.0-5.13 trad and sport routes) lies less than a 10-minute ride from downtown. The Grand Wall Base area (mostly 5.8-5.11 trad routes) is accessible via a 15-minute ride to the trailhead, followed by another 15 minutes of steep hiking. Even trailheads for outlying areas like Murrin Park (home to the Petrifying Wall) can be reached within 30 minutes on two wheels. The region’s growing commitment to cycling infrastructure includes designated bike lanes on main routes.

Yosemite Valley, California

Despite its reputation as a road-trip destination, Yosemite Valley’s flat terrain and dedicated bike paths create a surprisingly bike-friendly climbing environment. From Yosemite Village, Church Bowl (with trad and sport routes from 5.6-5.12) is a three-minute bike ride. And Swan Slab (5.1-5.11), located at Camp 4, is a 10-15-minute ride from Yosemite Village. El Cap, however, is not readily accessible via bike—unless you’re willing to brave the crowded road, which doesn’t have a bike lane. During peak season, when the Valley’s parking lots become congested, cyclists enjoy unimpeded access to crags. While bike rentals are available in Curry Village, the rental stock is pretty dated, pricey, and usually sold out by 8am, so it’s definitely better to bring your own.

North Conway, New Hampshire

This New England climbing hub features several premier crags within easy pedaling distance of downtown. The renowned Cathedral Ledge—home to popular trad routes like Thin Air and Toe Crack—sits about 2.5 miles via River Road from North Conway’s center. Whitehorse Ledge, another classic area featuring moderate slabs and challenging cracks, is accessible via the same route. The region’s popularity during fall foliage season means bike access becomes increasingly valuable as roads and parking areas fill with leaf-peepers.

Lecco, Italy

This easily accessible crag features an impressive vertical wall with occasional overhanging sections, located above Lake Lecco’s eastern shore. Positioned left of the Pilastro dell’Orsa Maggiore and Pilastro Rosso formations, Discoteca (most routes are 5.8-5.13) offers bomber limestone with some softer sections, characterized by edges, slopers, and nicely textured features. Reaching this Italian gem is straightforward—just 40 minutes by train from Milan to Lecco, then a quick 15-minute bike ride from the city center to the wall.

Car-free climbing in the ecopoint homeland

Haunritz, Germany

With a convenient 22-minute train ride from Nuremberg to Hartmannshof, climbers can easily access the Haunritzer Wand without a car. From the station, a pleasant 15-minute bike ride to Haunritz followed by a short five-minute approach hike leads to this impressive north-facing wall. Best climbed during the warmer months of June and July due to its shady aspect, Haunritzer Wand sits just 30 meters right of the neighboring Märchenland crag. What makes this wall particularly appealing is its impressive size and diverse grade range, offering routes from beginner-friendly 5.4s to project-worthy 5.13d testpieces.

Schmidtstadter Wand, Germany

Accessible via a quick 27-minute train ride from Nuremberg to Etzelwang, followed by a scenic 20-minute bike route, Schmidtstadter Wand (5.10a-5.11d) offers a perfect escape from crowded climbing areas. This hidden gem features excellent Jurassic limestone with short, quality routes on slightly overhanging, pocket-filled faces. Thanks to recent vegetation clearing, the wall dries quickly after rain, making it a reliable option even after wet weather.