Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

I pressed hard on my fingertips as my body wavered on the granite slab. Runout on the 6th pitch of Squamish’s notorious 5.11b R friction slab, Dancing in the Light, I tried to mantle my way up to a bolt. But my body teetered. Suddenly I was running down the Apron, the huge swath of low angle granite below the Chief. Alex Honnold, my wide eyed belayer, watched me hussle down the slab, eventually catching me 30 feet below the belay. I smeared back up to where he was waiting, took a few minutes to calm down, and then tried again. My second try on the pitch, I did better, walking up it with ease. But the contrast between that first try and the second—aided by the spectacular nature of my “fall”—made me obsessed with slab climbing. I wondered how hard it could get and how I could improve.

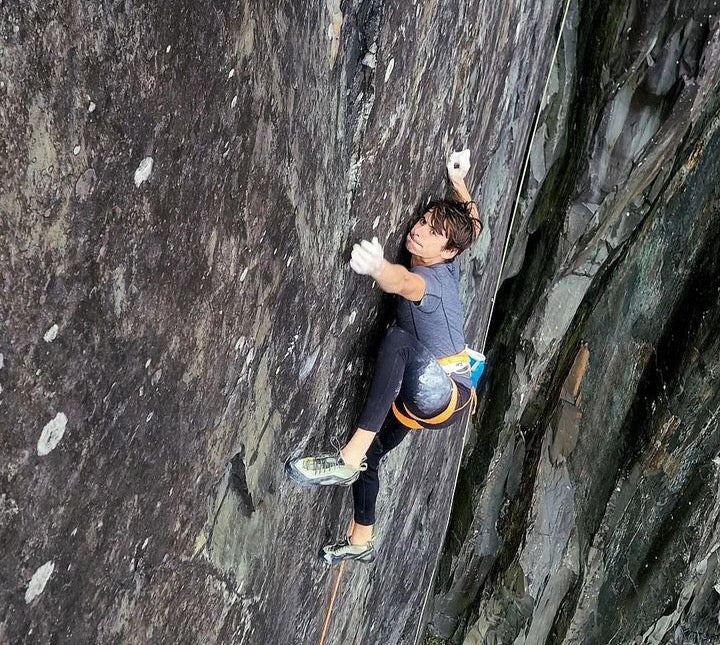

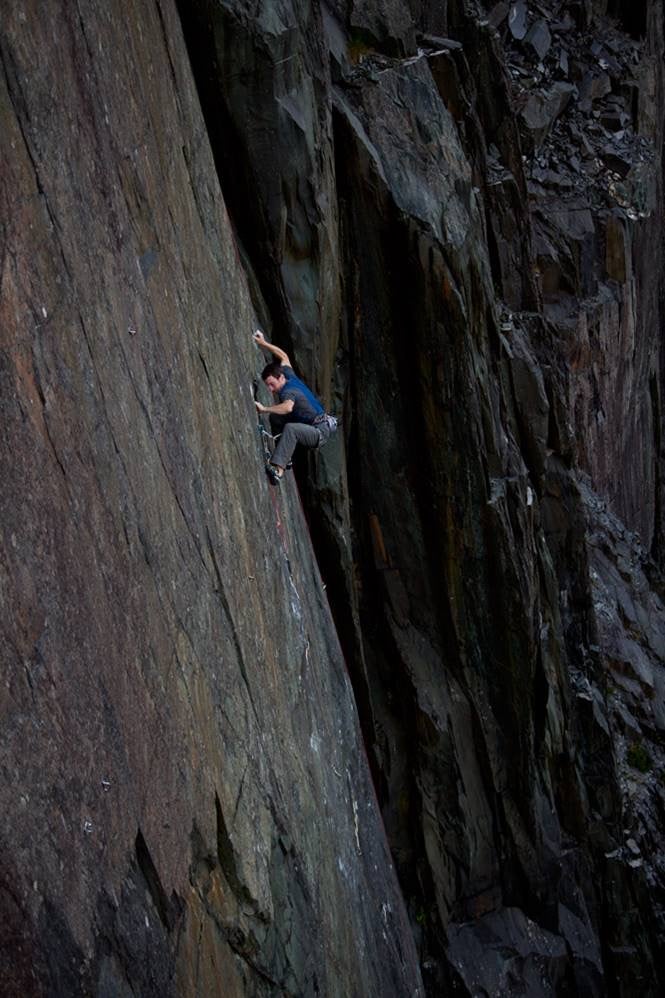

This past November, Franco Cookson made the first ascent of The Dewin Stone, a 5.15a slate route at Twll Mawr, in North Wales. The route takes a direct start and direct exit to James Mchaffie’s Meltdown (5.14d). Both are among the hardest graded slab routes in the world.

View this post on Instagram

The slate has a long history of hard slab. In the 1990s Johnny Dawes, known for his bold gritstone routes and no-hand climbing ability, established The Very Big and the Very Small, a three bolt 5.14a at the Rainbow Slab area in Dinorwic quarry in Llanberis. For a decade, the route held the title as the world’s hardest slab. But Dawes tried harder routes in that style, eventually bolting and projecting what would become Meltdown.

“It’s tiny footholds but super positive,” Mchaffie said of climbing on slate slabs. “It’s more about flexibility and confidence than endurance and [power].”

“Slate’s quite unique really. There’s very limited friction on the natural rock itself,” Franco Cookson said, adding that the distinct holds with little texture in between makes the climbing feel different than grit or granite. “It is generally more like climbing indoors.”

When I asked if The Dewin Stone was as hard a slate line as was possible, Cookson said that there’s a line that starts on The Dewin Stone, reaches the intersection of Meltdown, and then heads right and up into new and harder terrain. Aptly named The Nails Project, Cookson said it could be the hardest line on the slate. But the future of difficult slate slabs is limited though due to the size of the area. Mchaffie supposed that places like Yosemite; Pedriza, Spain; and the granite walls of Madagascar could yield harder slab climbs. The difficulty would be in being able to invest in the formations, he says, since some slabs can just be impossible. “You have to spend a lot of time on a bit of rock to discover whether it’s climbable or not,” Mchaffie said.

With its 5.15a grade, Dewin Stone currently holds the title as the hardest slab climb in the world, but that belies the difficulty of many other low angle climbs. “It is weird that there’s so little really hard slab climbing,” Cookson said. “Because grades are so subjective, if something’s got a really high grade, all that’s saying, really, is that there’s only a select number of people who can climb it. Surely there’s slab climbs where that’s applicable.”

Paige Claassen, who made the second ascent of Art Attack, a 5.14b granite slab in Northern Italy’s Val Masino, agrees that slab grades are a little out of whack. “Slabs don’t really receive high grades even though most people probably can’t get off the ground on many slabs, so it’s difficult to quantify from a grade perspective,” she said.

This theme of difficult grading is typical in places like Yosemite, the mecca for hard slab climbing in the United States, where the polished granite slabs make for excellent terrain but the grades largely fail to translate the difficulty. In June 2000, for instance, Tommy Caldwell and Beth Rodden made the first free ascent of Lurking Fear (VI 5.13c) on the left side of El Cap; but despite being one of the more accessible El Capitan free routes, the smooth granite wall hasn’t seen a second ascent. “No single move is crazy,” Caldwell said of the meandering second pitch, which is one of the cruxes. “But for thirty minutes your feet are just sliding off the holds, so it’s more of a mind test.” The seventh pitch proved to be even more difficult. Caldwell had a portaledge set up at the base of the pitch and traded multiple lead attempts with Beth Rodden. “It’s probably a 5.13a slab to a really hard three-move section. Finally one day my foot just didn’t slip. I got the body position just right and I got through it.” Rodden sent the pitch a few days later.

“It was all the kind of slab climbing that I love,” said Rodden said of the first hard pitch on Lurking Fear, “which is balancing, figuring out how to grab a hold, how to weight your foot, and how much to put on your fingers. The hard slab climbing on Lurking Fear was just super fun because it was like little tiny edges on granite, the best granite around, in Yosemite, on El Cap. Not only was the climbing good but the history and made it amazing up there.”

Despite efforts from strong climbers from across the world over the last 23 years, Lurking Fear hasn’t been repeated. “At the time I’d never heard of a slab harder than 5.13c so we just rated it that,” Caldwell said. “I think in modern grade it would be firmly into 5.14.” Which may just mean that Lurking Fear belongs on the list of hardest slab routes in the world.

“Really good climbers are comparing slabs in terms of how much time and mental anguish it takes them versus 5.14+ non slabs and then grade them the same,” Caldwell says.

Grades aside, even defining what the slabs are can be challenging, since many people have different definitions of what counts as a slab.

“People call routes slabs that are not slabs.” Claassen noted, highlighting Smith Rock’s To Bolt or Not to Be (5.14a). “It’s not a slab. It’s vertical.”

Claassen added that people often mistakenly use the term “slab” to define a style. “I think people don’t like slabs—or technical insecure face climbing—so anything that feels insecure and on your feet they just lump into the slab category so they can hate on it.” Claassen said. “I would define slab as an angle, not a style.”

“If you want to talk about the hardest slabs in the world,” Caldwell said, “It’s got to be the old definition, you have to be able to stand there and let go without tipping over backwards.”

Though the slate has some of the hardest graded slabs in the world, the style’s quite different from granite slab climbing. “The slate generally has better holds,” said Ignacio Mulero, a Spanish climber who made the second ascent of Meltdown. “It’s a style in which you climb more with your hands than with your feet and perhaps finger strength is more important than good foot technique.” Granite slabs tend to feature more climbing that you can do with no hands.

In the spring of 2017, Ignacio Mulero made the first ascent of Territorio Comanche (5.14c), a 90-foot, 75- to 80-degree, Joshua Tree-esque slab located near Madrid. The climb has numerous no hands sections.

“Pedriza, or granite in general, is the opposite [of slate],” Mulero said. “You climb more with your feet than with your hands. Most of the holds are crystals, they are more imperfect and when you take them you use your thumbs or the sides of your fingers more as a balance rather than to pull them. All the strength to make the movements falls on the big toes and legs.”

View this post on Instagram

Tricks to improve the dark art of footwork.

“What makes slab climbing hard?” Beth Rodden asked. “Gosh… Everything! It’s hard to learn to trust how much weight your rubber can take, how much you can really use the footholds, and how much a little teeny handhold can actually make a difference, even if it’s just a smidge. It’s learning to see all the little tiny imperfections of the rock and how that can help. I don’t think you can hangboard your way into better slab climbing. I think if you really want to get better at slab climbing, you just have to go do it.”

Mulero agreed. “It is always easier to train the physique aspect than the technique,” he said. “Training on a climbing wall doesn’t have as much transfer when you go outside to climb on the slabs. That is what makes people lose interest in this I think.”

Franco Cookson, however, had other ideas, recommending the UK phenomenon of toe-boarding, which involves exercises similar to a hangboard but for your feet, as a way to improve at slabs. He suggested that the best way to improve toe strength is training in a semi-unsupported shoe and switching to stiffer shoes when climbing for performance. He also noted that budding slab climbers should remember to use not just the straight-on front of your shoe but the side as well.

Claassen, too, thinks slabs can be trained indoors. “It’s about trusting yourself and your body and your center of gravity and balance,” Claassen said, adding that comp style boulders, particularly those involving balancing around on volumes, help build slab skills. “Also believing something is possible that feels really really unlikely. I think that’s part of why people don’t like slab climbing: it seems so improbable. And it’s hard to track progress and know how hard something is and how close you are.”

Perhaps one of the best ways to succeed at the dark art of slab climbing is to simply do it. Honnold and I smeared our way through Squamish’s long list of granite slab routes, and the practice certainly paid off for Honnold, who’s mastery allowed him to solo the notoriously insecure Freeblast (5.11b) on El Cap while sending the Freerider (5.13a). As for me, I’ve kept working on those skills, standing on my toes, balancing on volumes, and trying my best not to skin my knees.