The clash between guidebook authors and climbing apps raises a bigger question: what do we lose—and what do we gain—when beloved print traditions go digital?

The post Can Climbing Guidebooks Survive the Digital Age—and Do They Need To? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

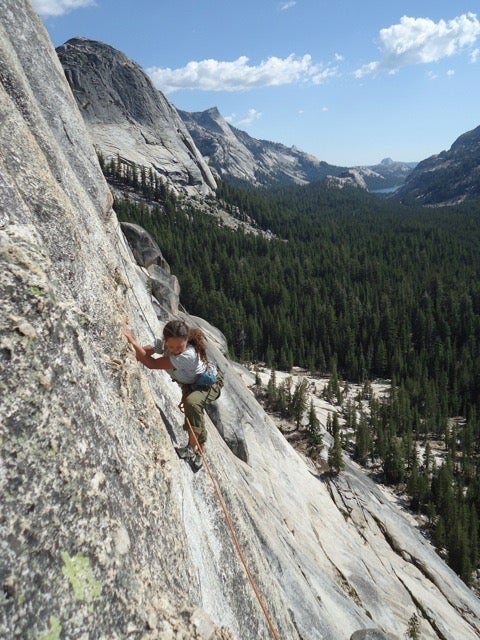

A boulderer in the desert

Picture, if you will, a lone boulderer with a pad strapped to their back, hiking across public lands, in some familiar place in Southwestern America. Scattered sagebrush, pieces of obsidian, and manzanita dot the desert as their approach shoes kick up dust on the trail beneath them. The pad makes scraping sounds as they turn to fit their body between a scrub oak and a boulder. Rounding the boulder, they look up and find their line. A condor grunts overhead as the boulderer tosses their pad on the ground and pulls out their phone.

They sit on their pad and watch beta videos while assessing their own body metrics and wondering if they have the ape index to reach the crux the way a user on their screen did. They set their phone up against a creosote bush to film themselves at the perfect angle, then they swap shoes, chalk up, and give it a burn. They top out and pump their first for the camera. When they get down, they log their send and upload their video onto the app. A gray fox watches a roadrunner as they scroll around for more problems on the boulder.

This portrait of the present plays out every day across hundreds of climbing areas. Jump back 20 years, and a paper guidebook and flip phone would be out. Jump forward 20 years, and, well, if researcher and Google’s AI Visionary Ray Kurzweil is correct, the Singularity will have taken place, and our lone boulderer will be some half-human, half-AI machine potentially crawling backward up V25s. The only recognizable element will be the boulder. Maybe the creosote bush will still be there.

In twenty years, there undoubtedly will be a whole host of new conversations concerning ethics and AI in climbing (Can it be used in comps? If using AI to develop a new area, does it get a FA credit?) and other aspects of human life. But, for now, we’re in the digital age. As apps progress, the paper guidebook endures. But, can it hold on—and should it? A recent, very public battle between a guidebook author and popular climbing app spotlights where physical guidebooks might someday get lost, and who is determined to keep them alive.

Common courtesy

In 2008, middle-school science teacher David Lloyd was living in Lander, Wyoming, when his friend Steve Bechtel, who had previously written a bouldering guidebook on the Wind River Range, suggested that Lloyd write an updated version. “He said I was so much more into bouldering than he was,” Lloyd tells me. With Bechtel’s permission, Lloyd went to work. He recruited graphic designer Ben Sears to do the layout, and they shelled out $8,000 for a run of glossy pages. “It was really pretty, and people liked it,” he says. “But it took four years to make our money back.”

Lloyd was on the board of the Central Wyoming Climbers’ Alliance (CWCA), and he sought their advice on whether he should follow his Wind River Guide up with another guide to The Rock Shop, a Lander-area bouldering destination. The other board members expressed concern that Lloyd would be moving to Grand Junction the next year and wouldn’t be around to help with any access and sanitation issues that might pop up from bringing in a new crowd. “So, I put the Rock Shop guide on hold and moved to Grand Junction the next year,” he says.

Years later, as climbers often do, Lloyd sold his house and most of his belongings in Grand Junction and decided to hit the road in his Toyota Tacoma. “I wanted to live the dirtbag lifestyle,” Lloyd says. “For who knows how long—10, 20 years, even. But I ended up driving straight to Lander.” Lloyd lived in his truck and climbed at The Rock Shop for a few months before the guidebook bug bit him again. “I’d been gone a long time, and nobody had made a new guide. So, I thought, ‘Alright, I’m jumping back in.’”

Lloyd convened again with the CWCA, and this time, they begrudgingly agreed that somebody was going to have to make a new guide soon, and that someone may as well be Lloyd. Executive Director Justin Iskra gave Lloyd a tour around The Rock Shop and showed him all the new routes that Iskra had developed. “I got the CWCA approval, I announced it on Instagram, and I talked to everyone at the coffee shop on Lincoln,” says Lloyd. “So, I knew I was good to go.”

Lloyd feels that there are a few bare minimum requirements for starting work on a new guidebook. “If it’s out of print, someone can update a guide, or, if someone has doubled the number of problems, then it’s time for a new guide,” Lloyd explains. “But the new author should always reach out to the old author. It’s common courtesy in our world.”

In the past, Lloyd has been supportive when authors have reached out about updating his guides. Jake Dickerson and Steve Bechtel reached out to him recently, and they all agreed that it was time to update one of Lloyd’s old guides. Lloyd says he completely supported their project. “They’re locals, and Steve Bechtel makes great guides.”

But in 2023, Lloyd got a phone call to discuss a different type of guidebook. “KAYA called me, and they wanted to use my guidebooks for The Rock Shop and Unaweep Canyon,” Lloyd tells me. “That’s when it all started.”

The Feist Case

KAYA describes itself online as “an all-in-one climbing platform” that helps you find climbs and beta, with over 300 partner climbing gyms and digital guidebooks for nearly 115 North American destinations. It was created in 2019 by four founders, including TED Fellow and current CEO David Gurman.

“We were on a climbing trip in Fontainebleau when I shattered my ankle,” Gurman tells me over the phone. “I was sitting around a hotel room wondering what to do with my life, when co-founder Austin Lee asked me if I wanted in.” Gurman did, and KAYA began. KAYA was mainly known for tracking beta for indoor climbing problems, until in 2022, Gurman and co-founder Marc Bourguignon were walking through the woods in Squamish when they got lost. “We were trying to find this boulder problem, and we were like, ‘Dude, there’s got to be a better way.’ Just that little moment really inspired building out the outdoor guidebook side of it.”

Now, KAYA considers itself a digital guidebook publishing company. “We don’t aggregate guides,” Gurman says. “We don’t make them. We’re a publishing platform for guidebook authors to create digital guides.” The advantages of a digital guide are plentiful: climbers can save weight and space in their packs, contribute their own photos and beta to the community, and enjoy updates without having to wait several years to buy a new version. KAYA’s $9.99 per month Pro tier and payment model separates the app from what most climbers see as its main competitor: Mountain Project. The free website, now run by mapping app onX Backcountry, puts the onus on users to upload all data. They don’t pay guidebook authors to upload their guidebooks.

“I would say that the hardest part of all of this is actually getting the GPS data of all the climbing locations,” Gurman says. “OnX is betting that people will give it for free via Mountain Project. KAYA collects community-submitted GPS data as well, but is mainly guidebook authored.” He reports that guidebook authors are responsible for 85% of KAYA’s total climb taxonomy; the other 15% is from regular users.

In 2023, a mutual friend connected David Lloyd with KAYA to discuss digitizing his Unaweep guides. “I wasn’t somebody who wasn’t into tech, or digital guidebooks at all,” Lloyd tells me. “In our first meetings, they made it sound so good. They wanted all 2,250 boulder problems for Unaweep, which are my volumes one and two.” But then Lloyd got the contract. “I’m willing to pay myself next to nothing to make a guidebook, but for them to offer next to nothing for the work just felt like an insult.”

Lloyd reports that he was offered several payment options, which ultimately amounted to about $1 per boulder problem:

“Option 1: 40% revenue share, no cash upfront, for providing complete data on 2,250 problems and moderating content monthly.

Option 2: 30% revenue share, $500 cash upfront for providing data on 2,250 problems and moderating content monthly.

… continuing in this pattern until Option 5, which offered $2,250 cash and 0% revenue share.”

KAYA confirms the details to me, adding that they’ve since increased their revenue share with authors. Option 1 is now 50%.“This aligns better with our ‘author-first’ mentality,” Gurman tells me.

Lloyd called the folks at KAYA and let them know that he didn’t think it was the right time for Unaweep to go onto KAYA. “Rather than write back and ask what my concerns were, they just said they were going to reach out to other people and have them put it on. I said, ‘Yeah, go ahead. No one’s gonna do it at that price. It’s nine miles of canyon, and the opposite side is a 40-minute hike.’ And here we are, it’s 2025, and users have put like 150 problems up on KAYA, but no one has signed the contract and done the 2,250 problems.”

Two years after the Unaweep encounter, when the KAYA team decided that it was time to put The Rock Shop up, instead of calling Lloyd again, they called a different Utah guidebook author named Matt Desantis. Lloyd didn’t know DeSantis, so he felt like KAYA should have reached out to him about their plans to create the digital guidebook. Those are Lloyd’s rules, after all. “Matt did reach out to me about doing the guide,” Lloyd says. “But immediately after hearing from him, I went and looked, and the guide was already up. So, he reached out to me after already doing it. I told him someone from KAYA should have reached out to the CWCA, since they weren’t even that happy about me doing my first guide.”

Lloyd and his daughter took a close look at the KAYA Rock Shop guide and couldn’t help but notice that it had all the first ascents on it. “How did they get that information? Only through my book could they get that info,” Lloyd says. “Nobody but me had put it all together.”

Lloyd was frustrated, so he went public with his concerns. On August 13, Lloyd published a blog post called “The Trouble with KAYA,” which later made it to Reddit. KAYA responded publicly on Reddit and Lloyd’s Instagram.

“I didn’t accuse them of plagiarism, exactly, but I did accuse them of plagiaristic practices,” Lloyd says. “It’s reference data they’re copying—the route names, grades, first ascensionists.” DeSantis confirmed on Lloyd’s Instagram that he got the first ascent information from Lloyd’s guide, but added that he independently collected all of the pins, pictures, and trail data. He wrote on Reddit that he added about 70 additional problems not featured in Lloyd’s list.

But is that a legal issue or a moral issue? Or both? To answer that, I contacted Michael Cohen, an IP lawyer in Southern California who has represented Hyundai, Walgreens, and Kia and been quoted in The Wall Street Journal, BBC, and Los Angeles Times.

“When you’re plucking out bits of information,” Cohen tells me, “Facts and numbers and statistics, etc., that’s not protectable.” But subjective descriptions could be.

Cohen tells me about a case he studied in law school called “The Feist Case.” Somebody had duplicated exact information from a phone book and was getting sued. The court came back and said that there was not enough creativity involved in names and phone numbers for duplicating them to be considered a copyright violation. A copyrightable work needs to be an original work of authorship with at least a minimal degree of creativity. So what does that mean for guidebooks?

“If it’s just an app that’s extracting factual information,” Cohen concludes, “It’s very unlikely you’ll find a copyright issue.”

Cohen did not comment on the ethical issue.

What about the black oaks?

David Gurman says it’s a “bummer” that David Lloyd decided to air his grievances the way he did, and that KAYA has little recourse to get him to pull it down. He also says that he thinks it forced important dialogue in the guidebook space.

“We’re not trying to destroy print guidebooks,” Gurman tells me. “We’re not trying to destroy guidebook authorship. If anything, we believe that a Mountain Project-like format sucks up all the data and cuts guidebook authors out of the monetization equation. And we want to continue to support guidebook authors. If there’s no more monetary incentive to create guidebooks, then there’s no more guidebook authors.”

Lloyd doesn’t agree with that: “Guidebooks are a labor of love, not money. A huge motivation when I write these guidebooks is that I fall in love with a place and I want to share it. And I’m trying to write the guides in a way that leaves people with a good experience and helps them love the place, too. Guidebooks have done that for me. They’ve changed my life and helped me appreciate places so much more. When I get on an app, it’s just about individual problems. And you don’t know the history or get the feel for the area as a whole. Guidebook authors fall in love with a place and that’s what they’re trying to pass on.”

In the future, Lloyd thinks there will always be a place for printed guidebooks, but only at the major destinations. “Yosemite, Joshua Tree, Squamish … [in] the areas that people travel to, spending another $50 for a good guidebook won’t stop anyone. With the little local areas, KAYA will take those over.”

Gurman disagrees. He says the wave of digital is inevitable, but the death of printed guidebooks is not. Gurman has a giant bookshelf in his office that is filled floor to ceiling with guidebooks. “It’s just different use cases. People enjoy sitting down the evening before and flipping through guidebooks… there’s just something about the tactility of having what really is a tree in your hand and just feeling it and reading it. Getting away from a screen for a second. Which, I admit, is really important.”

I spoke to another guidebook author who works with KAYA for one area, but turned them down for another: SJ Joslin, the author of the Yosemite Bouldering guidebook. In January 2022, KAYA contacted Joslin about putting the Yosemite Bouldering guidebook on KAYA. Joslin wasn’t interested.

Both Joslin and their co-author, Kimbrough Moore, did, however, publish the digital guidebook for Golden State Bouldering with KAYA. “The Bay Area is a really tech-forward place, and people are interacting with apps all the time, so KAYA was more suitable for it,” Joslin says.

Joslin adds that what’s really important to the community of Yosemite is that people get out into nature, and the Park doesn’t get consumed by social media and technology. “By and large, Yosemite is the kind of place you should be able to check out and interact with people more than platforms,” they explain. The author didn’t want to work with KAYA on the Yosemite guide, and they sent KAYA literature from the National Park Service about the Wilderness Act as a response. The excerpt talked about preserving the wilderness character of wilderness areas.

Eventually, KAYA sent someone else to the Valley to gather information. “They ripped off all of our work,” Joslin tells me. “It stinks, because I know many of the people at KAYA, and I really like them as people. If you’re going to put a guidebook out there, you should do it with the support of the community. You have those awkward conversations with people you’ve been climbing with for decades. It’s a relationship. And if the community says no, respect that.”

When I present Joslin’s case to Gurman, he responds, “We thought SJ [Joslin] was going to moderate and potentially come on as the guidebook author. “We had a guy go there and collect the GPS data. We pushed ahead, thinking we were collecting data to work with SJ later.” Gurman admits that Joslin saw the data live in the app and thought KAYA was competing with them. “It was a draft, but we didn’t have a draft mode. So, to be fair to SJ, that’s what it looked like. But that wasn’t the intention. It really was to collaborate and proactively add information so we could work with SJ on it in the future.”

Gurman took down the Yosemite guide and apologized to Joslin and Moore in an email. He says that KAYA won’t publish Yosemite until they have a local author and moderator.

KAYA may not have initially listened to Joslin, but, to their credit, when the pushback got louder and they started hearing from mutual friends as well, they took the Yosemite guide down. Legally, it was fine. Ethically, they finally agreed, it wasn’t.

On September 25, 2025, after Climbing interviewed Gurman for this article, KAYA published a press release addressing their communications with several guidebook authors. They called visualizing the Yosemite data in the app “a crucial mistake.”

“What I want when people come to Yosemite,” Joslin says, “is to notice the black oaks, and how Indigenous people have been using acorns to get food for thousands of years. And how they’re still doing prescribed burns, and that there are frogs in the pond. Not just how to get beta on a boulder. That doesn’t convey at all if my work is just uploaded to some app.”

Erik Sloan, guidebook author of Yosemite Big Walls, The Ultimate Guide, and Rock Climbing in Yosemite, the 750 Best Free Routes, agrees that guidebook authors don’t get the credit they deserve. “I think they’re a pretty misunderstood breed,” he tells me over the phone from the Valley. “I’ve been self-publishing for 11 years, and it’s exhausting work. The books take up my whole garage, and it takes forever to break even.”

Sloan hadn’t heard of KAYA. He uses Mountain Project, and he likes it, but he doesn’t always trust it. “The comments and updates on Mountain Project are a cool element, and you’d think a bonus over physical guidebooks, but so many of them are wrong. Maybe someday ChatGPT can go through there and comment about which human comments are right and which ones are wrong.”

Back to the Singularity

If physical guidebooks are gasoline-powered cars, and AI is electric, that would make current climbing apps like onX and KAYA hybrid vehicles. A more efficient way to travel now, but soon to be outdated themselves. Placeholders, if you will.

In September 2024, Apple released its newest form of Maps, which now includes customizable trails in national parks. Currently, this threatens apps like AllTrails, Gaia, and onX more than it does the climbing space. But with the popularity of climbing rising, will Apple someday go vertical? And when it does, will it come for digital climbing guides, too?

I ask Gurman how KAYA, a company run by six climbers, plans to protect itself against AI from larger companies like Google, Microsoft, and Apple, but he seems unimpressed with the tech giants’ progress so far. “If Apple were able to somehow snag the GPS data for every notable climbing and bouldering route across the world, then the question would be, are there other augmentations to the data set that would make KAYA’s data more valuable? Like the ascent data, the suggestion engine stuff—height and reach, the beta videos, and the metrics that personalize in-app experience.”

I joke with him that maybe when the Singularity happens, KAYA can pivot to printing guidebooks. “That’s not even a joke,” he says. “We’ve been in discussions with several print publishers about doing that someday.”

Lloyd and I talk about AI as well, and though he admits that he “wasn’t too techy,” he has experimented with it. “I played with ChatGPT while trying to find The Multiverse (V14/15) at Neverland one time,” he says. “I heard some rumors that AI was pretty good at GeoGuessr, and I thought, Whoa, then it might be good at finding boulder problems.” He says it was hallucinating at first, but then it finally put him in an area that could have been the right spot. But without a guidebook, he couldn’t be sure.

The post Can Climbing Guidebooks Survive the Digital Age—and Do They Need To? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

A routesetter reveals what your preferred hold might just say about your climbing style, desires, and fears.

The post What Does Your Favorite Climbing Hold Say About You? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

I’ve been a setter for about seven years, a climber for 11, and an extrovert for 33. I love getting to know people and climbing, and when those two worlds collide, I can convince myself that everything will be alright.

Recently, I had the unique opportunity to apply these two strengths and make some observations. I’m not saying these observations are scientific, but they might just explain why you keep picking problems that look suspiciously similar week after week. When you step towards a problem, what really matters isn’t what the setters intended, but whether they gave you holds you like. Your favorites reveal a lot about you —not just as a climber, but as a person navigating life.

Here’s what your favorite hold reveals about you and your Enneagram type—a personality framework with nine different archetypes based on insights dating back millennia. (If you’re not sure what your actual Enneagram type is, you can take a free test here.)

Crimps → Enneagram 1

The Rational, Idealistic Type: Principled, Purposeful, Self-Controlled, and Perfectionistic

If crimps are your favorite hold, you live on the edge—literally. You’re either (a) a shortie with fingers of steel, or (b) a masochist. As a crimp lover, you tend to be detail-oriented, disciplined, and, for some reason, have the most hip flexibility in the group. You’re not too sure why everyone is scared of that slab climb (why do their legs keep shaking?), and you might be too familiar with how an 8mm edge feels digging into your finger pads. Whenever the beta is too convoluted, you are the one to remember that no crimp is too small to piano match.

Your friends hate when you downplay how hard a climb is: “It’s just tiny crimps—super straightforward.” Meanwhile, their tendons are screaming. But hey, someone has to inspire fear and admiration simultaneously.

Jugs → Enneagram 2, The Helper

The Caring, Interpersonal Type: Demonstrative, Generous, People-Pleasing, and Possessive

You like security. You’re the type of person who reads Yelp reviews before picking a restaurant and always carries an extra snack “just in case.” In the gym, you’re always down for a campus board sesh or campus move on a boulder. Your folly is that you often misjudge climbs based on jug placement (“There’s no way a jug would be on a V8,” you say, looking at the start hold).

Outside, you’re the climber who says, “I climb for fun, not grades,” but also somehow ends up being the one logging every send on Kaya. Everyone loves you because you offer an encouraging “Yeah! Nice!” on every attempt. You’re basically the golden retriever of climbers.

Pinches → Enneagram 3, The Achiever

The Success-Oriented, Pragmatic Type: Adaptive, Excelling, Driven, and Image-Conscious

Pinch lovers are ambitious and unfazed about sketchy clips. “Pump” and “lactic acid” are not words in your vocabulary (or cardiovascular system). Whether you’re latching a hold despite it being “wristy,” biking a roof hold with your toes, or coconut-squeezing a plastic sphere like your sponsorship depends on it, you know how to adapt.

Pinch lovers are easy to spot in the wild because of their unnecessary urge to pinch almost everything. Common examples of prey include 2x4s at Home Depot, a stack of folding chairs, or sides of open doors.

Slopers → Enneagram 4, The Individualist

The Sensitive, Withdrawn Type: Expressive, Dramatic, Self-Absorbed, and Temperamental

Congratulations: you thrive in chaos and the unknown. Temperamental, like you, slopers can go from “solid” to dry firing at the drop of a hat. You’re the kind of person who believes in “trusting the process” even when the process is clearly failing.

In the gym, you brush the holds so often the setters wonder if they have a new dual-tex hold (see related personality below). In your friend group, you’re the one insisting the next sloper is “good” even though everyone can see its entire grabbable surface from the ground—and boy, is it slick.

Underclings→ Enneagram 5, The Investigator

The Intense, Cerebral Type: Perceptive, Innovative, Secretive, and Isolated

Underclings lovers are strong, focused, and can be a bit unhinged at times. You roll up and show everyone that sometimes finger strength means nothing when the hold is flipped upside down. Your betas can be seen as visionary, as you start underclinging holds no one thinks about. Eventually, this leads to more enigmatic moves like thumb-der clings.

Dual-Tex → Enneagram 6, The Loyalist

The Committed, Security-Oriented Type: Engaging, Responsible, Anxious, and Suspicious

You chalk your hands every 10 seconds, even though everyone knows it doesn’t help. You crave suffering and attention in equal measure. You love dual-tex holds because they’re cruel puzzles disguised as plastic. If dual-tex is your thing, you’re the kind of person who laughs when your friends slip and then immediately posts the video on Instagram. You find that stepping on the no-tex surface of a hold (or the half-inch-sized part of texture that’s exposed) perfectly encapsulates to others how close you are to an anxiety attack.

Volumes → Enneagram 7, The Enthusiast

The Busy, Fun-Loving Type: Spontaneous, Versatile, Distractable, and Scattered

Volumes aren’t just holds, they’re the future. If you love them, you’re artsy, experimental, and maybe just a little dramatic (or at least enjoy climbing with flair). You don’t climb problems—you perform them. Every climb has the potential to become a dynamic run-across-jump-double-clutch-gaston. The monochromatic setting in gyms is great, but you’d rather be spontaneous (or is it distracted?) in your movement. Many of your sessions feature either the phrase, “It goes,” or your attempt to climb a problem facing out, because why not? You find yourself trying random laches while your friends are resting by their projects.

You’re the most likely to be spotted lying on the pads, staring at the wall. Your spotters can’t decide if you’re seeing the next project or if you’ve finally sprained your ankle. Regardless, whenever you see a visionary move, your friends roll their eyes because they know that to you, “just one more try” actually means eight.

Pockets → Enneagram 8, The Challenger

The Powerful, Dominating Type: Self-Confident, Decisive, Willful, and Confrontational

If pockets are your favorite hold, you’ve accepted that every move is a gamble for your tendons, and you like it that way. In climbing and in life, you’re confident, decisive, and powerful. You’ve gotten really good at deadpoints, and blocked holds don’t intimidate you at all. What most people see as potentially tendon-popping holds, you see as holds without the fluff.

Unbeknownst to you, your friends have started a betting pool on when you’ll finally blow a pulley.

A common tell-tale sign that someone likes pockets is if they carry bags of groceries with a sub-optimal number of fingers per bag.

Mini-Jugs → Enneagram 9, The Peacemaker

The Easygoing, Self-Effacing Type: Receptive, Reassuring, Agreeable, and Complacent

Mini-jug fans are pragmatic realists. You like holds that look friendly but require focus (is that hold upside down and blocked?). Like the ever faithful mini-jug, you’re probably the glue of your climbing crew—the one who reminds everyone to hydrate, warm up, and double-checks anchors. Sure, people want to get to the volume-cluster at the middle of the wall, but to get there, they first have to climb through the mini-jugs.

In life, you’re dependable and steady. Without you, everyone knows the session falls apart.

Holds and personalities: In conclusion

At the end of the day, your favorite hold might say more about you than you think. Maybe none of this is true, or maybe the setters really do know you better than your therapist. Regardless, it’s always such a joy seeing all the quirks and betas that different climbers bring to the wall. And that’s what makes this sport so special. It’s a place where diverse personalities can meet under a common complaint: “What were the setters thinking?”

The post What Does Your Favorite Climbing Hold Say About You? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

A quick detour into the etymology of the term—and how climbing language is still evolving

The post The Strange Story Behind Why We Call Ropeless Climbing “Free Soloing” appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

In 1945, at age 45, John Salathé took a Sierra Club rock climbing clinic at Hunter’s Hill, a beginner-friendly crag in the Bay Area. His guide climbed to the top of a pitch, anchored in, and pulled up the rope.

“Go ahead, John, climb freely!” the guide hollered down to Salathé. The guide couldn’t pull up the slack fast enough, marveling at the speed of this Swiss novice. But when Salathé arrived at the belay, he wasn’t tied into the rope. He had thought “climb freely” meant to climb ropeless.

“I learned this story when I got artifacts from John Salathé,” said Ken Yager, president of the Yosemite Climbing Association, which runs the Yosemite Climbing Museum. Yager relayed the historic tale when I asked him about the origins of the term “free soloing.” Apparently, this mid-century incident is how the term “free” came to reference both the style of climbing without aid, and the act of climbing ropeless.

“They should have figured out it was a problem then,” Yager reflected on the double meaning. “I’m sure it’s just a conglomeration of different terms. It is very difficult to explain to people the difference, even people with a general understanding of climbing.”

Aside from the secondary meaning incurred when Salathé misunderstood his Sierra Club instructor, “free climbing” means using only holds on the rock to move up a route. Conversely, “aid climbing” refers to leveraging gear placed in the rock to move upward. (Yager shared that climbers called this “artificial climbing” back in the day.)

But the story of Salathé only explains half of the term in question. The other half, “soloing,” means to climb without a partner (and thus without a belayer). One can also solo with a rope, belaying themselves—referred to as “rope soloing.” So how did these two words come together?

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the first recorded use of the term “free solo” appeared in 1977 in the writings of John Gill. Perhaps best known as the father of bouldering, Gill also free soloed his way through the late 1950s and `60s. We reached out to Gill for insights but never got a response.

Whether Gill invented the term or was merely reflecting current vernacular, we may never know. But perhaps the phrase emerged like language often does—randomly and unpredictably, rather than intentionally. This might explain why so many climbers today find themselves correcting non-climbers on what “free solo” means.

Neither “free” nor “solo” imply ropeless. In general, Yager said he is relatively fed up with the evolving linguistics of our sport. “I gave up when they threw in pinkpoint, redpoint, and all that stuff,” he laughed. “And trad—that was another one that I hated. That’s real climbing. There’s sport climbing and real climbing.”

Another term that has changed over time is “power point,” which refers to your main tie-in point to an anchor. Jason D. Martin, executive director of the American Alpine Institute, says that at some point, the term “power point” evolved to “master point.” But using this second-generation term has become uncomfortable for many who recognize its connotations of slavery. Leaders in many fields, from computer science to religion, have chosen to move away from using “master” to describe relationships, including those between objects.

Now, Martin wants climbing to retire the word, too. In every BIPOC program Martin has led, someone calls out the term “master point” as triggering. He’s starting his effort with the second edition of the American Mountain Guides Association Single Pitch Manual, which he’s co-authoring with Bob Gaines. “With the new textbook, we’re trying to change the language to ‘central point,’” Martin said. He estimates that it will take a decade before “central point” becomes the predominant term.

So if our climbing lingo evolves—as it always does—could we come up with a better term for ropeless climbing than “free soloing”? Literal, albeit dry, alternatives make more sense in the binary with rope soloing, including “unroped soloing” or “ropeless soloing.” Gaines suggested “ropeless free climbing.”

We might also take inspiration from France, where, according to prolific free soloist Alain Robert, climbing without a rope is termed solo intégral. The word intégral translates to “whole” or “complete,” as in totally solo or full solo. “At the end of the day, solo intégral is a lot more meaningful,” Robert explained. “The meaning is deeper and more explicit.”

The path of least resistance might just be to remove “free” and call it “soloing”—something many climbers already do conversationally. It’s accurate, makes sense in contrast with “rope soloing,” and conjures up an image of a climber alone on the rock—no partner, no gear, no rope.

The post The Strange Story Behind Why We Call Ropeless Climbing “Free Soloing” appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

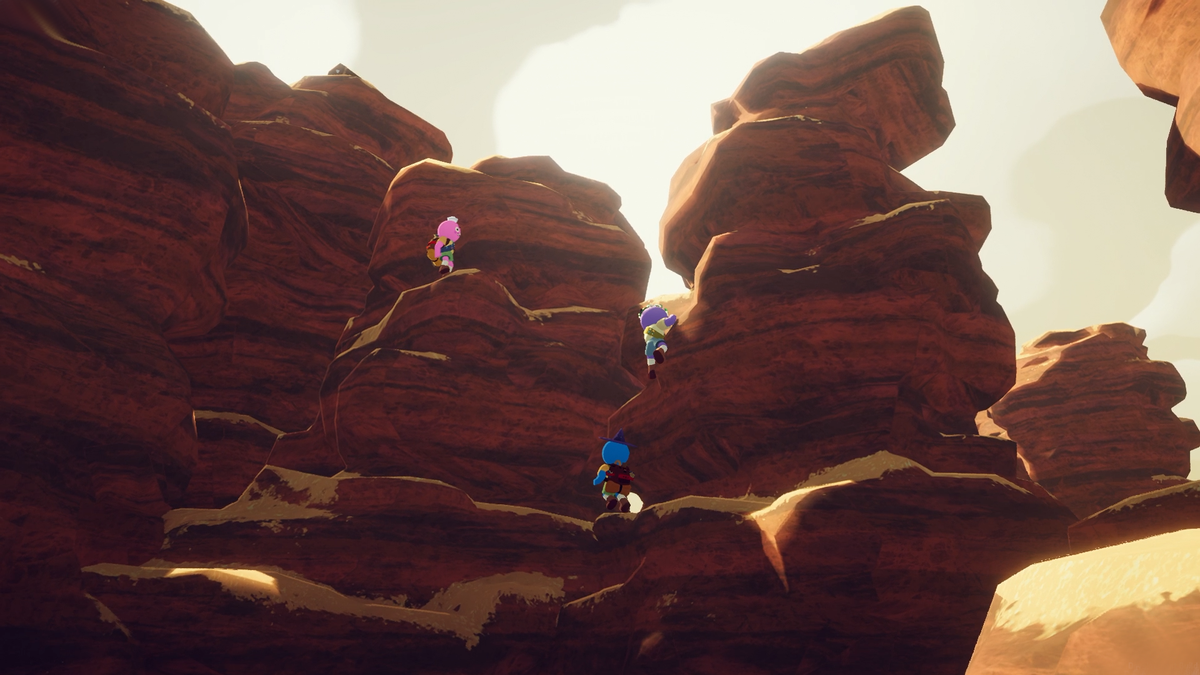

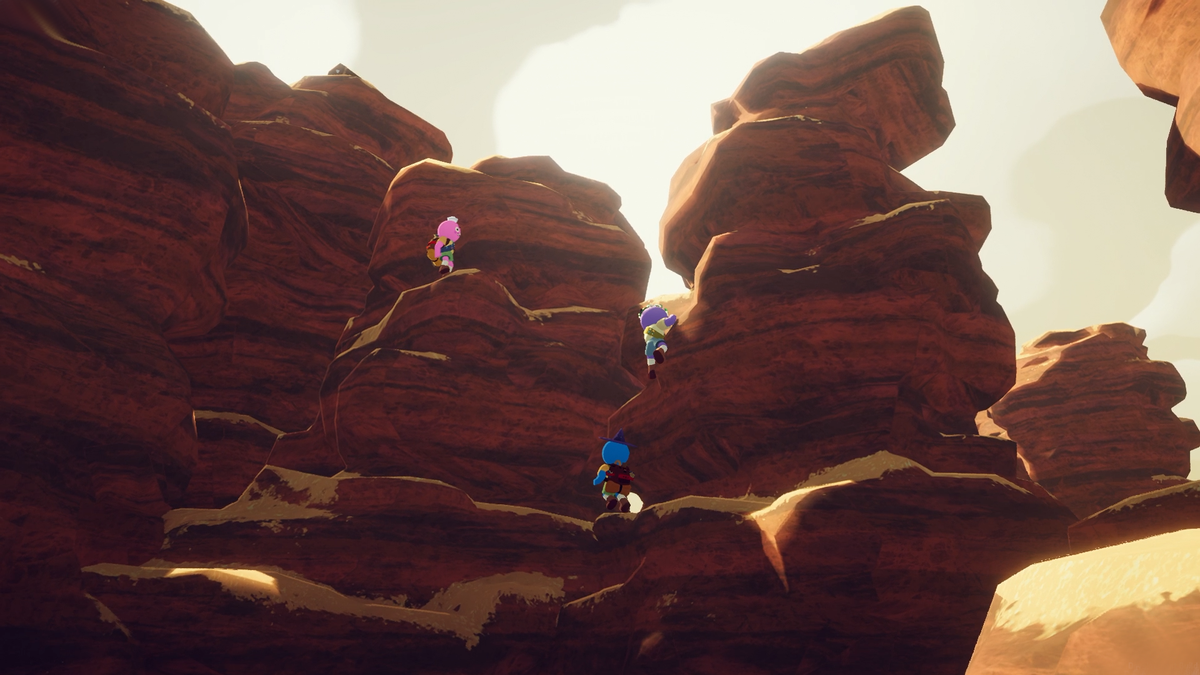

Our reviewer says ‘Peak’ might be the first "iconic" video game for climbers. Here's why.

The post This New Video Game Finally Gets Climbing Right appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

The wall seems overhung in all directions and the safest line is uncertain. My energy levels are low, and to make matters worse, it’s getting cold and the sun is about to set. My stomach rumbles as I look down into the yawning abyss. where I can hear my partner’s voice echoing off the walls, asking with concern whether we’re off-route.

A scene like this may feel familiar to many alpinists. Except I’m not in the Alps, Himalayas, or Andes. There are snacks within arm’s reach, and a warm blanket on my lap. I can hear the rain tapping at the window. I’m playing the new climbing video game: Peak. The objective is as you would expect: reach the top of the tallest mountain.

Unique among the world’s greatest sports, climbing has never really had its own iconic video game. Soccer has FIFA, American Football has Madden, and NASCAR has Mario Kart, each with their own obsessive following. As climbers and mountaineers, we’ve always had to make do with the real thing. This means the weary, the injured, and the rained-on are all denied their fix.

Well, those days might be done. Thanks to this quirky game released in June from Swedish developers Landfall, you might be able to scratch that climbing itch from home.

It’s not to say that climbing hasn’t featured at all in the gaming world. Beloved titles have put real effort into integrating climbing as a gameplay mechanic. We’ve seen Link scale massive mountains in Tears of The Kingdom, and cathedral-topping acrobatics in the Assassin’s Creed series. But climbing remains incidental to these games. It’s just a means by which you reach new areas to encounter a boss fight, items, or a puzzle. In Peak, we have a promising contender for the game many of us have been waiting for.

Why other climbing video games fail

Before we get into Peak, I must acknowledge that there is another category of games where climbing is the sole focus. I call these games “hand and foot positioning simulators.” Take the descriptively named New Heights: Realistic Climbing and Bouldering, for example. A player takes their time precisely moving one appendage from one gray 3D scanned feature to the next. Do this repeatedly for around five minutes and your avatar has reached the top.

Another game called Cairn (currently in demo) is visually gorgeous. With beautiful vistas and elegant movement style, it had me excited. But after actually playing it, I found that Cairn merely magnifies the mundane. You carefully move hands and feet to various grey polygons in search of upward movement, chalking up and shaking out as you slowly go. Developers have even tried doing it in VR with The Climb, but the formula is exactly the same.

What’s the problem with climbing games that faithfully recreate the biomechanics of climbing on screen? Sadly, playing them feels like donkey work. While they may represent the Euclidean form of rock climbing that you’d use to explain to an alien visitor (or your dad) “what it is,” the experience of performing it on a computer via repetitive clicks feels grim. Games that attempt to slowly, closely simulate climbing one move at a time feel a million miles away from real rock climbing—or from being a fun game.

A journey that will thrill climbers

Peak takes a different approach. Instead of focusing on rendering drop knees and 3D-scans of the Verdon Gorge, they took some of the core ingredients of climbing, then added whacky twists and perils to heighten interest.

Upon starting the game, the player finds themselves in the role of one of several scouts, played by up to three of your friends. Your small airplane has crash landed on a mysterious island. Thankfully, a helpful guidebook from a mysterious scoutmaster informs you that the only way to escape is up. You must climb the highest nearby peak to light flares and await rescue. (Note: If by some misfortune you happen to be in this situation in real life, the FAA’s advice is to stay near the wreckage!).

From the smoking crash, you can see the first peak towering above you. But what you can see is only the beginning. The climb takes you from ledge to ledge, over desert towers, up overhangs amid rain showers, and across dizzying Tyrolean traverses. All the while, you battle fatigue, hunger, and poisonous plants.

Designed for re-playability and with cooperation in mind, the game is great at creating moments of hilarity or tension. The cliffs of the game are regenerated at 1pm Eastern Time every day, so no two trips are quite the same. And the proximity chat means that friends who are close actually sound close, while friends who are far away sound far. This adds significantly to the atmosphere.

You may experience the sorrow of seeing a friend somehow miss a jump you just nailed, their anguished cries fading away into the mist as they tumble down the cliff. And the dreaded pump is as real in Peak as in real life. But since Peak is not real life, some players give over to their intrusive thoughts. One might deliver a banana peel, sending you skidding off a ledge. Or they could fiendishly lob a coconut at your head, just as you reach a cliff’s edge. But the game rewards comradely play. Some players make it to the summit of the peak, only to grow too weak with hunger to go on. The only way is for a friend to carry you Samwise Gamgee-style to a mountaintop rescue. Like real climbing, it’s at times frustrating, at times utterly cinematic.

Peak video game: My verdict

Peak doesn’t simply ask “What if you were climbing, but on a computer?” Instead, it asks “What if you were climbing in a race against a deadly frozen fog that will kill you if you falter?” Furthermore, it offers the novel ascension methods of human cannons, chain guns, or a strange “anti-rope” to assist with your ascent. And what if there were malevolent supernatural consequences for breaking Rule Zero of the game—that one should never ever abandon a friend in need?

By answering the questions we didn’t know needed answering and inventing options we never knew we were missing, this video game creatively builds on the world of climbing, rather than just digitally replicating it. The adventures it facilitates in the vertical plane are a near-endless source of shenanigans and stoke.

If you’re one of the weary, the rained-on, or the injured—or if it’s just your rest day—hit up some friends and give it a try. In an age of $100-plus cams, there aren’t that many ways you can squeeze more fun out of $7.99.

You can find Peak on Steam, or if you use macOS, you can play using this guide.

Watch a trailer for Peak video game:

The post This New Video Game Finally Gets Climbing Right appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

The climbing community has made positive strides against eating disorders and body shaming. But for some climbers, any discussion of weight now feels taboo. One doctor explores this tension.

The post Is It Ever OK to Talk About Weight in Climbing? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

I’m in the gym on a Saturday morning. I’m having a frustrating session where gravity seems awfully high. Later over coffee, my training partner and I are debriefing the session. I say, “I’ve been thinking of losing a few pounds.” Immediately, I feel a sense of guilt for bringing up this topic. “Absolutely not,” they reply. “You’re great just as you are.”

That’s what a friend is meant to say, right? Her default answer was rooted in body positivity, aimed at shoring up any insecurity or body dysmorphia I might have. Why, then, did it feel so dismissive?

Around the same time, I joined an online climbing forum. One of the cited norms caught my attention: “No body talk.” No discussing other people’s bodies, or your own. On the surface, this might seem a progressive safeguard against triggering people with eating disorders. However, something about the rule made me uneasy. It gave me the sense that talking about bodies at all was inherently problematic, as though the subject itself were shameful.

This made me think: What would be my preferred answer to my question following the gym session that morning?

Here are some examples of responses that would have been more helpful for me.

- “Interesting thought. How’d you think that might influence the power you’ve been trying to build?”

- “I don’t think that’s needed from a health perspective, but I get that weight can be a relevant training factor.”

- Or even just, “Tell me more about that.”

These are not the right answers for everyone, but I argue that body-related talk is not inherently bad, and it can be sensitive, constructive, and relevant.

I spent February in Idaho, enjoying a month in the snow—winter hiking, and skiing of all kinds, but not climbing. A few weeks in, I noticed I was about five pounds lighter. Seeing the number on the scale and knowing I wasn’t actively climbing at the time, I became concerned about losing muscle. I talked to a friend about it, and we had a thoughtful, healthy conversation about my weight, body composition, and nutrition. We also came up with strategies that would allow me to return home to Boston feeling strong. They even recommended a new brand of protein shake, which is now my favorite. It was a reminder that talking about these things can be empowering. These types of conversations can focus on performance and well-being, rather than judgment.

It’s important to be thoughtful about others’ histories with body image and remember that even a close friend might not have shared everything—but it’s also important to create a culture of listening and receptivity to ideas.

As a physician, I’m trained to talk about sensitive subjects like weight carefully. I also know how often silence around the topic can backfire. Instead of letting body talk become taboo, the community should cultivate spaces for sensitive, consent-based conversations where health, performance, and personal choice can be discussed without shame.

A sport wracked by eating disorders

Climbing has problems with body image and disordered eating. A 2020 survey study involving an international sample of 498 adult sport climbers reported an overall 8.6% prevalence of disordered eating. Among female climbers, prevalence was 16.5%, and among elite female climbers, it surged to 42.9%.

Recently, climbers have also shined a spotlight on these issues, making hard-won progress at fighting harmful attitudes. In 2020, Sasha DiGiulian bravely spoke out about body shaming and bullying, which had real consequences for the perpetrator, including losing sponsors. Beth Rodden has courageously written about how her long-term struggle with disordered eating undermined her well-being, despite short-term performance gains. And in 2024, after two doctors on the International Federation of Sport Climbing Medical Commission resigned and top athletes including Janja Garnbret spoke out, the IFSC became the first international sporting body to introduce regulations addressing Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs).

These were important, overdue changes. However, social change can bring about unintended consequences, even when the overall impact is positive. For example, mandatory seatbelt laws in the 1960s successfully reduced the risk of death if an accident occurred; however, some studies observed that drivers, feeling safer, then began to take more risks (known as the “Peltzman Effect”).

Has an unintended consequence of body positivity within climbing become a reluctance to talk about our bodies at all, and a sense that doing so is shameful? Has intentional management of weight become taboo, even when approached in a healthy, evidence-based way?

We often use the phrase “losing weight” to refer specifically to reducing body fat while preserving or even increasing muscle mass. But this is more accurately called changing your body composition. It involves altering the relative proportions of different tissue types in your body. Body composition can change even if your overall weight stays the same, or it can shift alongside changes in weight.

Fixing imprecise footwork, improving mental game, and working on pacing issues can bring more immediate results to one’s climbing than simply increasing one’s strength-to-weight ratio. Still, it is also true that an improvement of body composition can be helpful for climbing performance. That’s why it can feel frustrating—even gatekeeping—when already lean climbers dismiss weight talk entirely or insist “it doesn’t matter.” But here’s the important distinction: the fact that body composition matters does not mean it should be the focus for every climber, or that “losing weight” is automatically the best path forward.

There is also a difference between someone rapidly dieting in the pursuit of performance at all costs and someone changing their body composition in a gradual and responsible way. We shouldn’t treat the two as the same, because the real danger lies in confusing them. Nutritionist Tom Herbert (@usefulcoach) says on Instagram: “The act of paying closer attention to what you eat: source, quality, composition, macro/micro nutrient and energy values, is not disordered behavior, any more than paying closer attention to your training method … is disordered behavior … can become disordered behavior when used in a context that leads to poor physical, mental and social health. The desire to change your body is not disordered behavior.”

Is talking about weight taboo?

When I searched through threads on Mountain Project, Reddit, and the UK Climbing Forum, contributors warned that “Losing weight to gain climbing performance is one of the most short sighted ways to progress in climbing” and “almost every mid-level climber … should not focus on losing weight to climb better.” Others thought differently: “People will tell you to not worry about your weight because it leads to unhealthy habits of trying to lose it. This is certainly a problem in climbing and can’t be understated. It’s almost taboo to talk about it in some places …. but to act like it has no effect on climbing performance is wrong.” The conversation is complex and still evolving.

The desire to protect by avoiding a topic is not unique to climbing. We can borrow ideas from how medicine approaches sensitive conversations about weight, where historically, stigmas have led providers to avoid discussing weight altogether, even when it’s relevant to a patient’s health. Clinical guidelines now encourage moving beyond silence. Organizations like Obesity Canada advocate for person-first, non-stigmatizing language and frameworks such as the “5As,” where clinicians initiate conversations by asking patients if they are comfortable discussing their weight.

The lesson is clear: Making a subject taboo doesn’t eliminate harm. It is better to work on our abilities to have sensitive conversations about difficult topics than to avoid them. Like many things, this is easier said than done. So, how can everyday climbers approach this topic thoughtfully?

How climbers can talk about weight

Working with a professional like a dietician when navigating these topics is ideal, but many people face barriers to access. For example, insurance coverage is often limited unless there is an existing medical diagnosis.

A more achievable goal could be a renewed focus on the importance of consent for conversations that could be triggering. It’s not that these conversations need to be off the table, but more that they need to be explicitly signposted upfront. I’ve taken to asking friends beforehand if they’re comfortable entering this space. I might say: “Hey, I know many people don’t like talking about this, but I have thoughts about my body composition. Are you comfortable chatting about this?”

I’d like us to approach the topic with openness. Let’s understand that some climbers may choose to adjust their body composition for performance, while others may not—and that respecting each person’s choice is part of being truly body-positive.

Rather than “No body talk” as a standard, maybe we need to be more precise. Perhaps “No unsolicited comments about other people’s bodies” is a healthier guideline. Or the admittedly less pithy, “We know weight management is a tricky topic, but it is relevant for some, so if you want to talk about it, feel free, but please create a side channel.”

It’s more important now than ever to combat false information. Simple messaging, while catchy, can unintentionally reinforce falsehoods. The climbing community should discourage blanket advice such as “Losing weight for climbing is always a bad idea” and “Talking about bodies is never OK.” Instead, let’s cultivate safe spaces for nuanced discussions.

Avoidance under the guise of protection may feel safer, but it risks creating an environment where a generation of climbers grow up believing that it’s shameful to talk about bodies. Or one where people with a positive body image, who want to manage their weight in a healthy way, must do so undercover—a new type of body shaming.

Climbing thrives on problem-solving—on testing solutions and adapting strategies. Let’s extend this mindset to guide conversations about bodies that both protect and empower, so that next time someone like me says, “I’ve been thinking of losing a few pounds,” we don’t shut the conversation down, but meet it with curiosity and care.

The post Is It Ever OK to Talk About Weight in Climbing? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

An op-ed on how despite a narrowing “gender gap," everyday female climber experiences remain unchanged

The post Women at the Top Are Climbing Harder Than Ever. But What Does That Mean for Everyone Else? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

The number of impressive accomplishments in women’s climbing this year is inspiring. I feel lucky enough to call some of these women friends. Watching them achieve their goals has been so cool. In some ways, it feels like climbing is really changing. But something felt off as I read through the headlines. For example, take this one from The Washington Post: “The gender gap has narrowed in climbing. These women have closed it.”

I’m a bit of a skeptic. Plus, the buzzy language about “closing the gender gap” felt too tidy, too enthusiastic. It made me wonder: What are we actually talking about here? It felt as if we were trying to wrap up some annoying loose end in the narrative arc of climbing so that we could all move on.

The day I started writing this, I went out bouldering with a group of friends. They were all men, which is not unusual for me and typically not something I’d bat an eye at. A man I didn’t know very well joined us. I noticed right away that, although we were all climbing on the same problems, he never once asked me for beta. Yet he was relentless in his supply of (unsolicited) suggestions, advice, and pointers directed specifically to me and no one else.

Normally, I appreciate the collaborative nature of bouldering, but this time felt different. While the men got to simply climb, I couldn’t help feeling condescended to by the input and feedback directed at me. It was as if I was the only one who needed help, despite us all climbing the same grades.

This is actually a common gendered scenario in climbing, and I grimace at how cliché it is to even write about something like this. After climbing for years, I had naively thought that these types of scenarios didn’t happen much anymore.

I left the boulders seething. I couldn’t make sense of the disconnect between my own experience and the public excitement around “narrowing the gender gap.” How could the gender gap be closing when the everyday experiences of women in climbing aren’t really changing all that much? How many noteworthy physical feats are required to lift up every woman in climbing, rather than just highlight the outliers?

Clearly, “narrowing the gap” hadn’t changed my experience as an average female climber. I wanted to know how it felt for someone who is purportedly closing the gap. So, I called up my friend Katie Lamb to get her take. She agreed that this simplified narrative leaves out a lot when it comes to her actual experiences.

“The best men are establishing V17 and 5.15d. This takes categorically more skill and strength than repeating those grades,” Katie told me. “However, back in the day, Beth Rodden and Lynn Hill were actually pushing the limits of what anyone was doing on El Cap. And they received considerably more pushback for doing so.”

Katie pointed out plainly that there are two gender gaps: a performance gap and an experiential gap, both of which still exist. While at least some exemplary female climbers’ accomplishments are widely celebrated, this still doesn’t address the fact that most women in climbing are simply not taken as seriously as men, no matter “how hard” they climb.

“The accomplishments of the outliers don’t significantly impact how average female climbers are perceived,” Katie agreed. We should still celebrate these accomplishments, no doubt, but to assume that they have any impact on the overall perception of female climbers is a mistake, and a trap that I think I had fallen into.

To me, the idea of “the gap” itself feels male-centric. Why do women’s accomplishments only matter in relation to what men can do? Perhaps we fixate on upper-end numbers and outliers as a way of tracking progress because it’s easier and more comfortable than trying to understand women’s actual experiences in the sport.

So, I wondered, what would it look like if there were no gap at all? In my experience, the gap doesn’t actually exist when I am doing the activity. When I’m on the wall, I’m not thinking about what it means or where I fit into society. I’m just climbing.

The beauty of climbing is that it brings us into the present, into our bodies and out of our heads. Perhaps we can simply let climbing be what it is for all of us. Let’s allow women to forge their own paths outside of “the gap,” beyond simply following in the footsteps of men.

Finally, though this essay is centered in my experience as a female climber, I would be remiss not to mention the experiences of nonbinary climbers, too. I aim to highlight the complexity of the idea of the gender gap so that all people can feel embodied in climbing, outside of gender.

This story first appeared in Tommy Caldwell’s newsletter, “Routefinding.” You can sign up for his newsletter here.

Jane Jackson is a writer based in the Sierra Nevada. She loves granite and being in the mountains, and has spent most of her adult life obsessed with rock climbing in all of its forms. She is the editor of the “Routefinding” newsletter at Patagonia.

The post Women at the Top Are Climbing Harder Than Ever. But What Does That Mean for Everyone Else? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Our case for low-stakes sending

The post Is Your Projecting Toxic? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

If you’ve ever poured months of your life into a project, you probably know the feeling of the dreaded “One Fall” zone. If you don’t—well, you’re a way better climber than me. But what happens when you’ve lost count of how many times you’ve one-fallen a route and are dangerously approaching triple-digit attempts?

When I’m coaching individuals to climb their hardest, we call this part of the projecting phase the “One Fall Hell.” And it’s in this “One Fall Hell” where some of the most toxic projecting moments inevitably occur.

The pitfalls of One Fall Hell

Projecting becomes an endless redpoint cycle: Every attempt ends in the same place, just short of success. No matter where I fall, I can pull back on, climb through, and reach the top—earning the dreaded “I’m so close!” without ever actually clipping the chains.

At first, this can feel motivating. But stay in this zone too long, and projecting shows its toxic side. The curiosity that drew you to the climb fades. Movement becomes mechanical, automatic, uninspired. Self-doubt creeps in. Negative thought loops start to run the sessions. What should feel playful and creative instead begins to feel heavy, stifling, and draining.

Projecting at your absolute limit will always cut both ways. Done well, it’s exciting, full of growth and accomplishment. Done poorly, it can bring stress, frustration, comparison, body-image issues, and unhappiness.

What toxic projecting looks like

When I was in my late teens, I lived deep in One Fall Hell. I jumped on climbs far above my ability with little understanding of movement, pacing, or even how to use clipping stances effectively. I thought raw effort would be enough. And it wasn’t.

The result was ugly. I became unbearable—hyper-focused, self-absorbed, uninterested in others. I was the exact opposite of the climber and the person I wanted to be.

From here, a pair of outcomes diverge. One leads to grinding through the cycle until you finally send. But if you’ve been trapped long enough, clipping the chains may feel more like relief than accomplishment. The other possible outcome is shelving the climb in the “someday” category—or walking away altogether.

On the flip side, there’s the danger of never trying your hardest. I’ve met plenty of climbers who live in the comfort of a “someday mentality.” They avoid the discomfort of real effort, and in doing so, hold themselves back. That’s where potential goes to die.

So what’s the answer to avoid toxic projecting?

It’s time to incorporate a low-stakes projecting mentality. (And to be clear, I’m talking about what for many, is a normal climbing mindset.)

This is why balance matters. High-stakes and low-stakes projects have to coexist. You can chase your peak potential, but you can’t live there all the time. Routes in the range of “I can do this in three or four sessions” build confidence. They give you a foundation you’ll need when you’re deep in the grind of harder, potentially more obsessive projecting.

And here’s a wild idea: Low-stakes projecting isn’t just about the difficulty of the route. It’s also a mindset—an approach that takes the pressure off the outcome, even when you’re on one of the hardest climbs you’ve ever touched. That, too, is a low-stakes approach.

What does this look like on the ground? Project a route, but don’t invest your entire soul and ego into the outcome of a redpoint. As you go into the projecting experience, set more goals than just sending. Instead of only projecting with the goal of sending a specific route, project to learn, project for the experience, or project just for the fun of it.

Failure is part of projecting. In fact, if you’re not failing, it’s not really a project, right? The paradox is that failure is the healthy part of climbing. It keeps us learning, growing, and pushing toward our potential. The real trick is shaping that process into something healthy, instead of something that tears you down.

The post Is Your Projecting Toxic? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

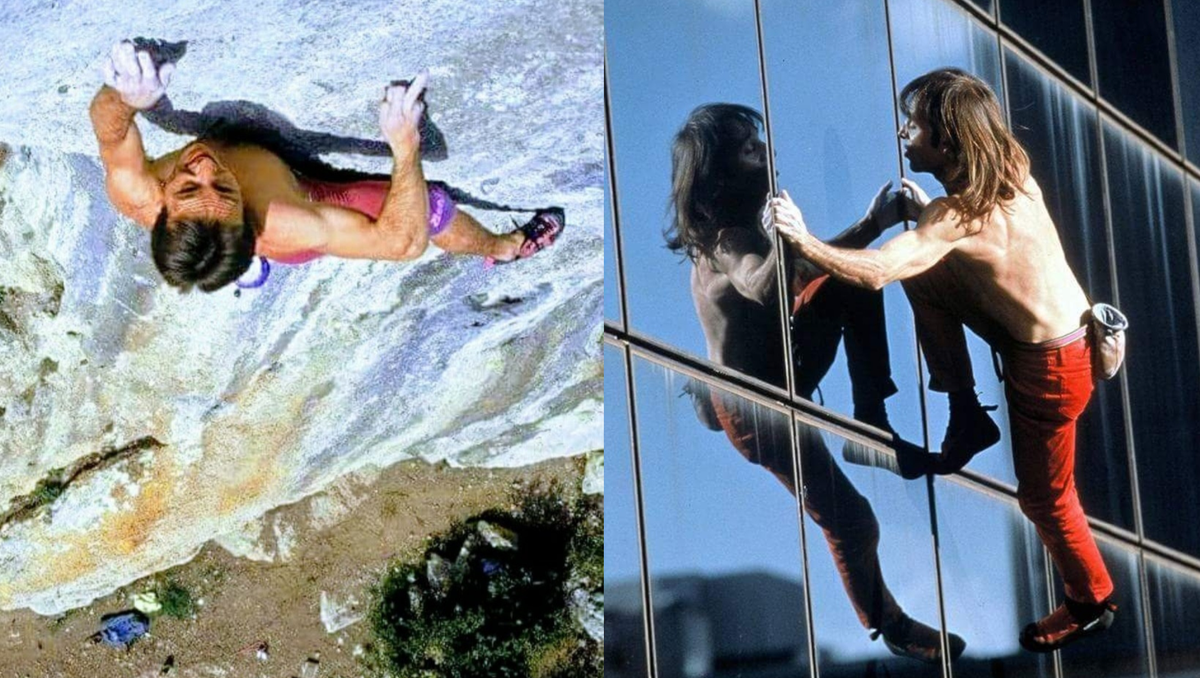

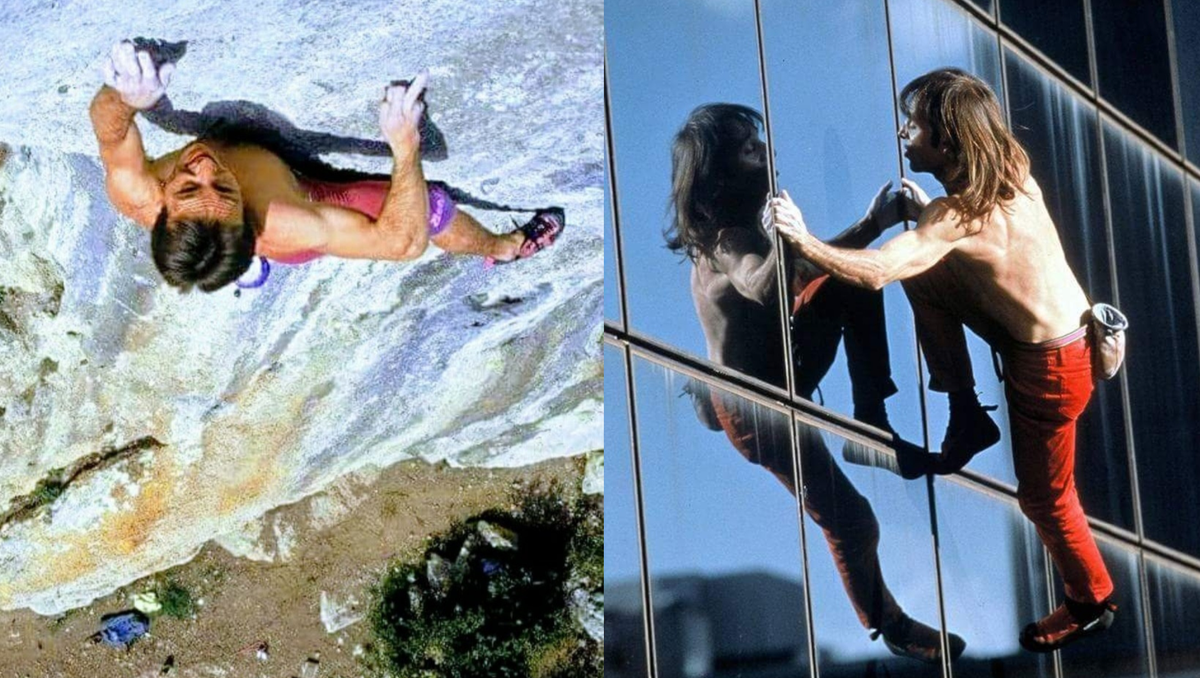

In a new biography on the French free soloist, Alex Honnold and Alexander Huber salute his pre-skyscraper record on rock. But how does Robert’s limestone heyday reconcile with his “crazy guy” reputation?

The post The French Spiderman Reflects on Free Soloing, Death, and Quantum Physics appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Alain Robert is worried the world has forgotten what happened before the internet. This may seem a bit strange, since he has become a fixture of climbing’s corner of the internet, and might be the most Instagram-savvy 63-year-old that I can think of.

But before he learned how to make a reel, before he climbed the Citicorps skyscraper in Chicago, and before he was arrested some 170 times topping out on buildings, Robert rolled the dice on rock. In a series of voice memos and screenshots delivered over WhatsApp, Robert made this abundantly clear to me.

I had originally reached out to the French free soloist after a new biography about him came out with forewords by Alex Honnold and Alexander Huber. At the time, I was in the middle of his first memoir: With Bare Hands: The Story of the Human Spider (2008). The other reason I contacted Robert is that little has been written about him here at Climbing. Just a book excerpt and a news story, 17 years old. A rollicking profile by Climbing contributor Owen Clarke did emerge recently in Summit Journal. The profile touched on Robert’s pre-internet legacy—and left me with an unsettled image of him as a conspiracy theory-slinging, Champagne-guzzling “crazy guy.”

The biography of Robert released last winter paints a different picture. Published by Catherine Destiville’s press, Éditions du Mont-Blanc, Spider-Man, Alain Robert, Free and Unattached is only available in French (and in Europe). Robert sent me English versions of Honnold’s and Huber’s remarks.

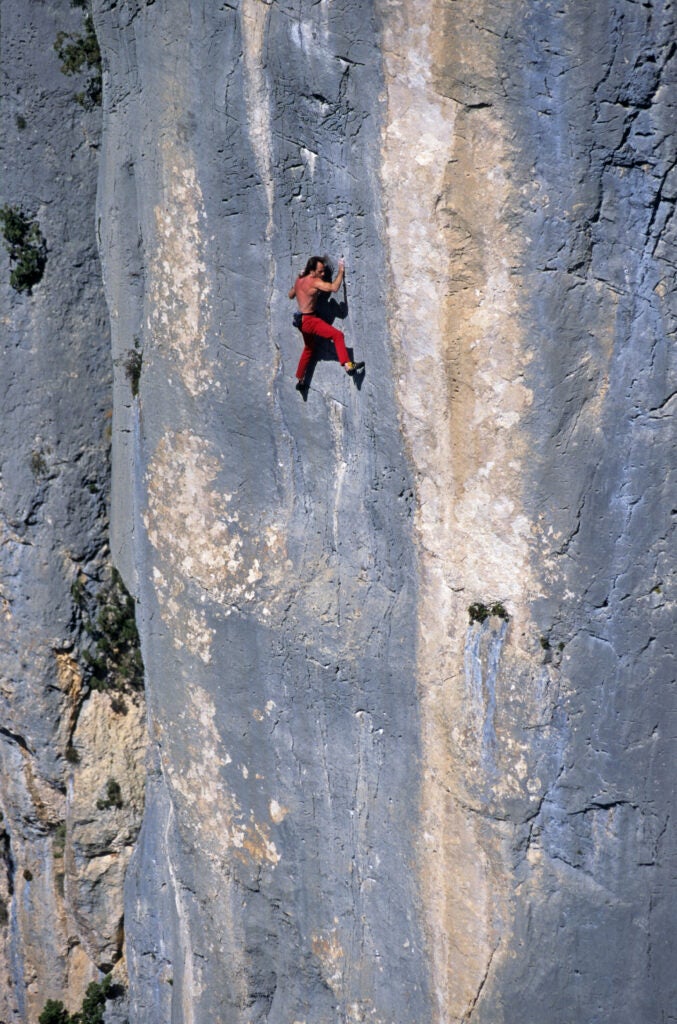

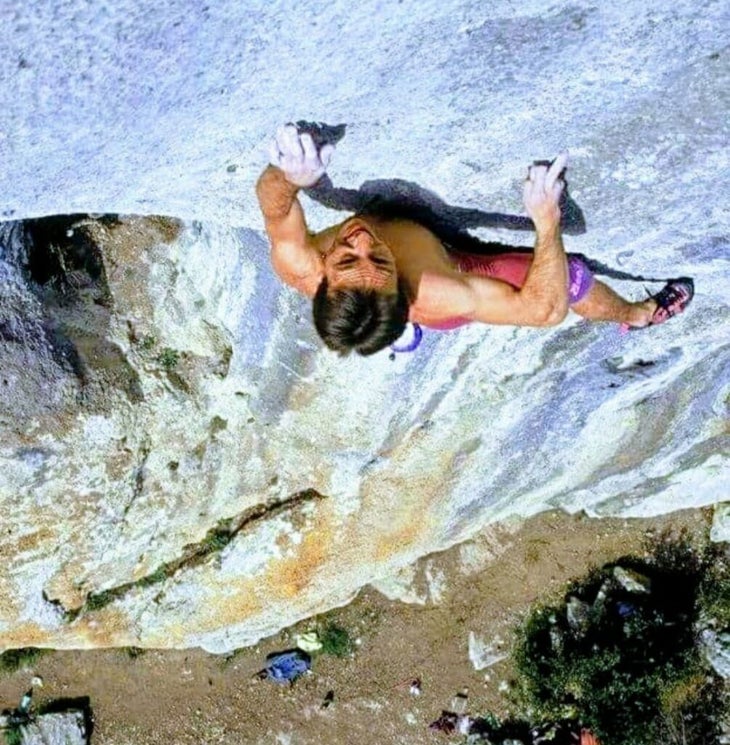

“I’ve always felt a certain connection to Alain Robert,” Honnold wrote. “The style and difficulty of the routes that he has free soloed on rock is truly unmatched,” Honnold specifically cited his free solo of La Nuit du Lezard (5.13c/8a). “I have nothing but respect for all that Alain has accomplished in his nearly 50 years of climbing.” He goes on to reflect that while sometimes Robert leans into the spectacle and is “derided” as a stuntsman, his climbing skills remain “unmatched.”

After declaring free soloing as the purest form of climbing, Alexander Huber wrote: “Alain Robert is far more than just a crazy climber who stood atop of the most spectacular buildings. Beyond that he is a pioneer who opened a new level in the art of free soloing.”

As this book reflects on Robert’s legacy, we are also watching the discipline of free soloing enter a different realm—and not the one Huber speaks about. As the democratization of media unfolds on social platforms, free soloists like Robert have an even greater opportunity to attract an audience with their shock-factor, can’t-look-away feats of climbing unroped. We recently tackled this subject at Climbing with a story on Lincoln Knowles, another soloist who monetizes his ropeless exploits, but through crowdfunding. Depending on who you ask, there might be vast or nuanced differences between Robert’s and Knowles’s soloing “content” and its potential harms.

So, on the one hand, there is Robert’s eccentric persona, rooted in recklessness, spiced rum (a long-time sponsor), and a swaggering sense of style that includes red leather and cowboy boots that he occasionally uses as climbing shoes. On the other hand, there are his staggering accomplishments, many of which seem to have indeed fallen to the wayside in our collective memory.

Before he donned a Spiderman suit up a Paris tower or went viral on social media, Robert made the first and second free solo ascents of a 5.13d. (At the time, the hardest grade yet climbed was 5.14b.) Many of his free solos on rock remain unrepeated. And while his urban “escalations” are indeed spectacles, the technical skill underlying his prolific success cannot be understated, with estimated grades up to 5.12d, according to Honnold.

Could free soloing shirtless for a photographer in the Verdon and taking selfies while climbing a skyscraper in a neon bodysuit be more similar than we think? Maybe it simply boils down to optics.

After weeks of back and forth on WhatsApp, I finally spoke with Robert from his home in Bali on the eve of his 63rd birthday. I wanted to find out if he was the outlaw Clarke made him out to be, with no intentions of backing off. Or could he finally be ready to dial it back as a senior soloist—with seven grandchildren—fraught with disabilities resulting from several groundfalls?

A conversation with Alain Robert

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and brevity.

Climbing: What part of Bali do you live in?

Alain Robert: I am in Balangan, quite close to Ulu. Maybe in the future, I’ll live four months in France in Verdon and eight months in Bali. It’s a good combination. I can still do rock climbing on a daily basis. The thing is, sometimes I’m a little afraid about myself, because I know that if I live four months in Verdon, I’ll be climbing free solo four months in Verdon every day—every single day.

Climbing: So maybe it’s better for you to stay in Bali.

Robert: Well, I went through that—meaning from the end of the `80s all the way until the mid-`90s, I was free soloing hard grades on a daily basis. But that was a very interesting period of time because when you are free soloing, you are alone. There was no media, no internet, no GoPros. Once in a while, there was a professional photographer or TV station following me, but there wasn’t much and I loved it this way.

Climbing: It sounds like you miss those simpler days. When was the last time you climbed on rock?

Robert: Oh, that was two years ago. I had stopped rock climbing for 22 years and then I came back to Verdon to do some free soloing onsight. Of course, my level was totally different. But what was interesting is that at the end of the day, my spirit hasn’t changed. I love pushing the envelope. Once upon a time, I used to be a good and strong rock climber. Nowadays, I am really an old guy. I’ll be turning 63 tomorrow. I see the new generation—there is this little girl who did 8c a few days ago. She’s like 9 years old. I have been free soloing for 50 years and I have seen a tremendous evolution in climbing.

Climbing: Going back to your time in the Verdon, I find it a little paradoxical that your three major climbing accidents didn’t come from pushing your limits free soloing, but from gear errors and a slip while guiding. How did each of those accidents change your perspective on climbing?

Robert: It goes back to the very beginning, before I even started climbing. I was afraid of everything as a young boy. I was shy and lacking self-confidence. Then I had a dream. I wanted to become courageous like Zorro, like Robin Hood. One day I saw a movie called The Mountain about a plane that crashed near the top of Mount Blanc. Two mountaineering brothers climb the mountain to seek survivors. That really inspired me. I decided, wow, one day I hope that I will be like those guys, climbing mountains, climbing on rocks.

So I fought very hard with myself, with this little boy, afraid of falling, afraid of dying, afraid of everything. That’s the reason why when people ask me about a few accidents, I say it has never changed my love of and my motivation for climbing.

Climbing: You must have a really unshakeable headspace to have survived those accidents and continued free soloing.

Robert: The thing is, I have deep faith in myself. You cannot say, “Oh, I’m just going to train hard to get physically stronger.” It doesn’t work this way. This is what Alex [Honnold] was saying about Pol Pot [a 5.13a slab route that Roberts considers the hardest free solo he’s ever done].

Climbing: Soon after you free soloed Pol Pot in 1996, you began pivoting your career toward free soloing buildings. Do you keep track of how many buildings you’ve climbed?

Robert: I’m not really counting anymore. Maybe like 250? But actually, I don’t really care. I still have some plans to climb new buildings. All of the sudden there is a new generation who are climbing some easy buildings and medium buildings. But if you look at all the difficult buildings I have climbed, none have been repeated.

Climbing: Is there a building out there that’s calling to you that you still really want to climb?

Robert: No, no, no. I have had the chance to stay alive for quite a long time. I took enormous risks and now I’m cooling down. I’ll be back in Verdon in October because I am doing a biopic. In the past, I have done 18 documentary films. This time, it’s something a lot bigger about 50 years of climbing. A little bit in the spirit of Free Solo. We’re going to see it most likely in 2027.

Climbing: While there have been a lot of documentaries about you, you’ve also done an effective job of promoting your own ascents on social media. Are you managing your own social media accounts?

Robert: Yeah. I am doing it on my own. The problem is that I am the one who is responding to people and if you’re not a climber, then it’s difficult because most people don’t understand much. So if it starts to be a non-climber who is responding, it’s going to be really bad.

Climbing: You’ve had some very diverse sponsors over the years. For example, you recently did a climb in Barcelona for a cryptocurrency company.

Robert: That was actually the second time that I was sponsored by cryptocurrency. What they organized with me in Spain was really huge. They rented a rooftop 300 meters away from the building and there were 100 people working up there, although everything was completely illegal. That was insane because actually they were live. I am still sponsored by Dead Man Fingers, this spicy rum.

Climbing: You’re not sponsored by a Champagne company? It seems like you need a Champagne sponsor.

Robert: I could have gotten Champagne for free. But the problem is that since I live in Bali, they cannot ship it to Indonesia or otherwise I will be paying an enormous amount of taxes … and you have realized that I love Champagne.

Climbing: Well, yes. Owen’s story about you in Summit Journal emphasized that. But that [indicating the mug he is holding on camera] looks like coffee.

Robert: This morning, I am on coffee. But you know it’s like eight o’clock in the morning in Bali. So I cannot start on Champagne. But actually I’m not drinking every day. Sometimes people may think that I am an alcoholic. The last two days, I didn’t touch a drop of alcohol. On Sunday, if I go for brunch, I like to enjoy a good Champagne. There’s a big difference between being seated with Owen, who is cooking me about climbing in Paris as it is raining cats and dogs—then, of course, I’m going to drink a lot. But if I am alone, I am just drinking like one or two glasses and that’s it.

Watch outtakes from our interview with Alain Robert, aka the French Spiderman

Climbing: I’m curious about your experiences in jail, where you’ve spent quite some time following your illegal “escalations” of buildings. What was the worst experience you’ve had in jail?

Robert: Maybe the last time I was in a jail that was bad was in the Philippines. I was injured; all of my fingers were destroyed, and also my feet. I was in a cell for six people, but we were 16 and there were cockroaches everywhere. Thousands. There is a light on 24 hours a day. And they are treating you like a shit.

It’s funny because when I was released, I was invited on a big live TV show and I met the mayor in Makati. She is the wife of a former vice president. We had lunch in a restaurant in Makati and I said on live TV that they could do a little better. It would be a small investment to get some clean cells like in Japan or South Korea. I have been jailed in San Francisco; there was a shower inside the cell—there was a TV. I have been jailed in China; it was not really good.

Climbing: Do you ever have dreams—or nightmares—about climbing buildings?

Robert: I’m dreaming very often about climbing on rocks or climbing on buildings. Sometimes falling. The good thing is that when you are dreaming and you are falling, the moment you are touching down, it wakes you up. Everybody is having this kind of dream. But I am a rather optimistic person. I’m not that afraid about dying actually. It’s just part of the process. We’re born, we die.

Climbing: What do you believe happens after you die?

Robert: For about two years, I have been very interested in quantum physics. There are thousands of studies by neurosurgeons on near death experiences from Yale, Oxford, Cambridge … they all come to the same conclusion: Our consciousness is not material. I am quite sure that we are energy, meaning our consciousness is not part of our brain. So when we die, our consciousness is still living. It’s just like entering into another room, another door, pushing a door.

Climbing: As you get older and continue to take risks, how have your thoughts on death evolved?

Robert: I would like to tell people not to be so afraid of dying. All our lives, we have been educated to fear death. I live here in Bali. And in the Balinese Hinduism, they are not afraid of dying. They believe that in death, the consciousness is not dying. They believe that they will be reincarnated as something else in their next life. People should be celebrating death. But if people are no longer afraid of death, then it’s going to become anarchy.

Climbing: When you die, what do you want people to remember you for?

Robert: I let them choose! What people may not realize is I did all the hard stuff on rocks or on buildings with a body that is completely destroyed. This is my hand. This is my wrist. [He holds up his visibly contorted wrist to the camera.] These are my fingers and these are my nerves. I also broke my ankles and everything.

[Editor’s note: Robert’s permanent disabilities result from three falls. The first two ground falls occurred in 1982 due to gear failures while rappelling. He also incurred serious injuries from a smaller ground fall caused by a slip while guiding in 1993.]

Climbing: Are you in pain all the time?

Robert: I have no pain actually. It’s more like two fingers, I cannot feel anymore because one of the nerves has been damaged in my elbow. When I am holding a pocket, if it’s very small, it’s a bit strange because I don’t feel it and the problem is that if you want to be sure that you’re holding it properly, you need to feel it. So I started to get used to it.

Climbing: Do you ever worry about popularizing free soloing and inspiring people who shouldn’t be climbing this way because they lack the necessary skill or mindset, and the consequences therein?

Robert: No, not really. If you look at the history, the people who are having the most accidents are those roof toppers. They don’t climb the side of the building—they use a fire exit, the lift, a big stick. So what has popularized this generation of roof toppers? The internet. Not me. I am fine with that, except this is not climbing. I am very sure that if tomorrow, there is no more internet, there is no more GoPro, there is no more of these people.

Climbing: What about you? If nobody was watching and there were no cameras rolling, no social media, would you still be free soloing?

Robert: I climbed for 20 years free soloing without nearly any media and I loved it and I’m still loving it this way.

Climbing: So, you would still climb buildings. You wouldn’t say, “Nobody’s watching. I’m going back to Verdon.”?

Robert: I love climbing buildings. As I said earlier, I am planning to live four months a year in Verdon. I’ll be climbing free solo every day. There most likely won’t be any images. There won’t be anything. It’s just because I love climbing.

The post The French Spiderman Reflects on Free Soloing, Death, and Quantum Physics appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

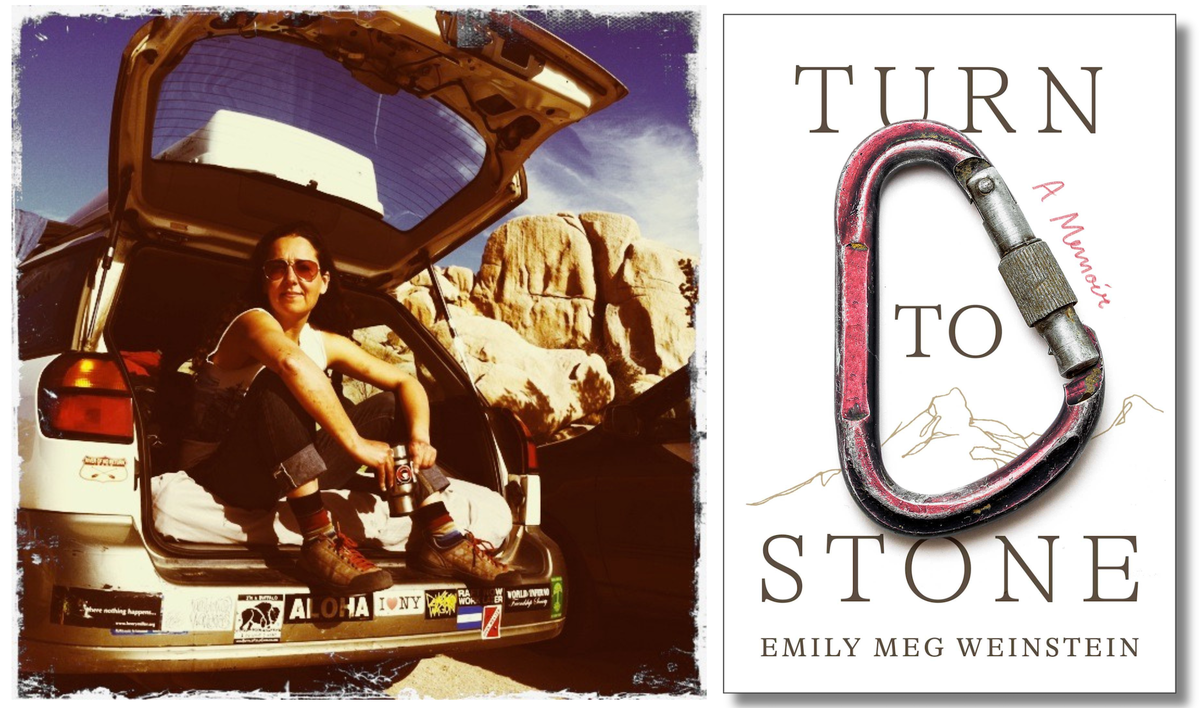

'Turn to Stone' shares one woman’s candid and hilarious confessions on dirtbagging, love, and the climbing lifestyle.

The post This New Memoir Reads Like Sex and the City, But for Rock Climbers appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

The new memoir Turn to Stone is not your typical climbing read. For one, the author is not a pro climber reflecting back on their career. (She is admittedly average.) Nor does the narrative center upon an epic mission ending in historic success—or tragedy. (The book spans a seven-year period during which nothing particularly noteworthy is climbed.) And there is no point per se—no soapbox assumed or major issue tackled. So what is Turn to Stone?

“The book is a love letter to climbing and the climbing community,” says author Emily Meg Weinstein.

The reading experience for me felt more like the diary of an unlikely dirtbag. Weinstein looks back on her best years with humor, nostalgia, and the search for meaning. Before becoming a climber, the author was embedded in the punk rock scene of New York—and decidedly unathletic. In search of new purpose after escaping a toxic relationship, Weinstein stumbles upon Yosemite and falls in love with the sport. She moves into her Subaru (dubbed “Suby Ruby”) and tucks under the wing of a rotating cast of charismatic mentors. And, yes, she also dates a lot of climbers—and has a lot of sex.