Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

On March 17, 68-year-old Earl Prunty, fell to his death while free soloing beside Washington’s Nooksack Falls, an 88-foot waterfall that plunges over a volcanic cliffside in two segments. While there are no established climbing routes at Nooksack Falls, Prunty frequently climbed and downclimbed the wet rock surrounding the falls unroped. Search and Rescue officials recovered his body on the south side of the falls, where no climbing equipment was present.

Rescuers discovered a phone that was filming the wall at the time of the incident. While the exact cause of the fall is unknown, the sheriff’s report stated, “The video, over three hours in total length, showed the bottom of the cliff band on the south side of the waterfall and clearly showed Earl falling from higher up.”

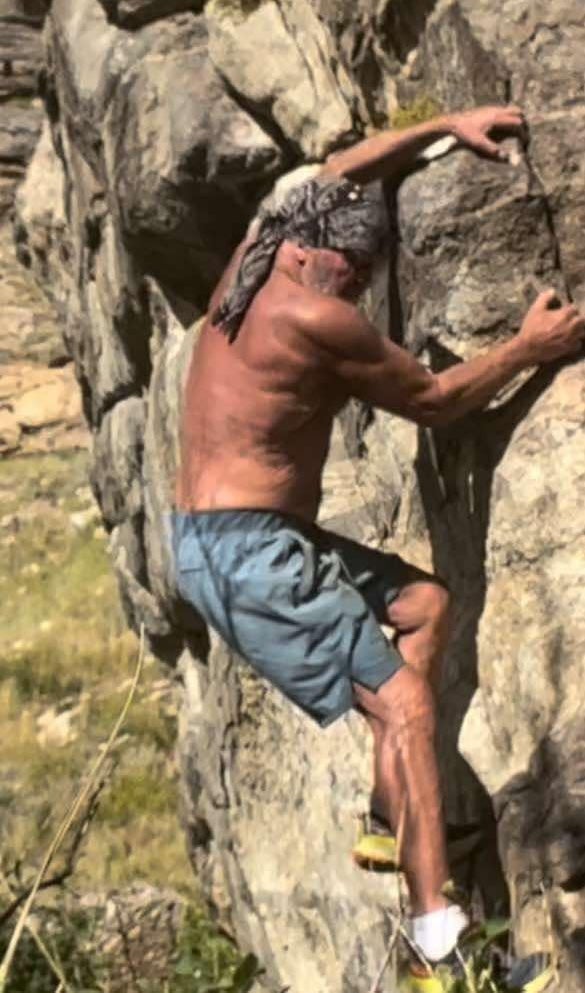

But Prunty wasn’t your average free soloist, if there is such a thing. The Washington climbing community knew him for both his kindness and his signature climbing style: downclimbing routes hands first, then free soloing back up.

Natalie Greisen, one of his three children, told Climbing, “I will be totally honest, when he told me that [he was downclimbing upside down] I said he was full of shit. He was a big storyteller. Larger than life.”

She assumed that Prunty’s penchant for humor and exaggeration had been at play when he revealed he liked to climb upside down. “Then my husband was with him one day, and he actually saw him doing it,” she recalled.

Appalled, Greisen asked her father why he’d do such a thing. Prunty explained to his daughter that he could see better by downclimbing this way, and that his hands were strong and agile enough to be up to the task.

A stonemason for 50 years, Prunty had a unique relationship with rocks. “Everybody knew his hands,” reflected Greisen. Stonemasons often cut, shape, and handle stone, which requires tremendous strength and dexterity.

“[His hands] were insane. They were stonemason hands. They were huge and cracked and calloused and rough. I think he just felt really stable and strong in his hands,” said Greisen.

Prunty’s social media feed is packed full of free soloing videos, most of which exhibit wet or icy conditions around his home waterfall. On occasion, Prunty roped up to climb with friends around Washington where he lived, or in Nevada. But he was never one to shy away from a challenge, which was one of the things that attracted him to climbing upside down.

As a young man, Prunty fell in love with the outdoors while spending time on his family’s ranch in Nevada. His role on the ranch was to break wild mustangs. “My dad would be out there running with these wild mustangs,” Greisen said. “He was totally wild.”

It was that same wildness that motivated him to backcountry ski and climb predominantly unroped. Prunty moved to Washington in 2014 or 2015, according to Greisen. He started hiking and skiing Mount Baker. That was how he discovered Nooksack Falls, a formation located just north of the peak that’s best known for its short hiking trail and overlook. Other climbers in the area tend to stay away from the feature due to its consistently wet or icy conditions.

Greisen described Prunty’s relationship with the Falls as “obsessed.” He’d often push his friends and family to get up before the sun to spend time at the waterfall.

Just a week before his death, Prunty accomplished one of his biggest goals: downclimbing the entire 88-foot Nooksack Falls wall head first. It took him two hours and 47 minutes.

In a celebratory Instagram post, Prunty reflected, “There’s little beauty downclimbing feet first with your eyes and nose smashed up against the rock, so I started climbing head first on the downclimb when I could, what a difference it makes to be able to take in all the movement and beauty where I climb!” He expressed a desire to “live outside the box,” and to follow through on challenging endeavors.

View this post on Instagram

While Prunty had originally planned to downclimb the route on March 20, he decided to move the date up to March 10. Prunty was newly married in 2024 to 58-year-old Dararat Kanjanakotch, who he’d met on a Facebook group for 50+ climbers. Kanjanakotch arrived in Seattle to visit her husband from Thailand on the day of his death.

Prunty’s “larger than life” personality, as Greisen described it, was a quality that made him a popular character in the climbing community and beyond. After her dad’s death, Greisen called his bank teller, who sobbed at the news. Strangers flooded Greisen’s inbox with kind words about the impact of her father.

While some climbers expressed incredulity at Prunty’s climbing style, others greatly respected him for it. Nick Dallaris first connected with Prunty to discuss climbing beta in the Mount Baker region. They became quick friends, and before long, Prunty took Dallaris to his favorite spot: Nooksack Falls.

The waterfall is relatively hidden, Dallaris explained, so a bit of bushwhacking is required to find it. “[Prunty] said he accidentally discovered it while skiing and almost fell into the ravine. We hiked up the mountain and then descended with a rope to the bottom of the waterfall,” Dallaris said.

Dallaris was surprised by Prunty’s determination, noting that he “went waist deep in the freezing water to get to the other side and did a little climbing.”

“He often referred to [Nooksack Falls] as his gym or sanctuary,” said Greisen. But unlike most climbers who prefer to keep their secret crags to themselves, Prunty was always sharing his sanctuary with friends and using it as a place to educate others about Leave No Trace principles.

In addition to his passion for protecting the environment, Prunty was also known for his ability to evoke belly laughs. “He started doing this thing where he would round up his age,” Greisen remembered. “ So, when he turned 60, he told everyone he was 65. And when he turned 68, he said he was 70. It wasn’t until I filled out his death certificate that I realized he was 68.”

“I feel so incredibly lucky that he was my dad,” said Greisen. “Usually when people die there are so many things left unsaid. But I feel so at peace.”