Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

Stories have always shaped the climbing community, whether it’s the play-by-play expedition tales that have inspired generations of alpinists to the candid and immediate storytelling of social media that drove unprecedented growth to our sport.

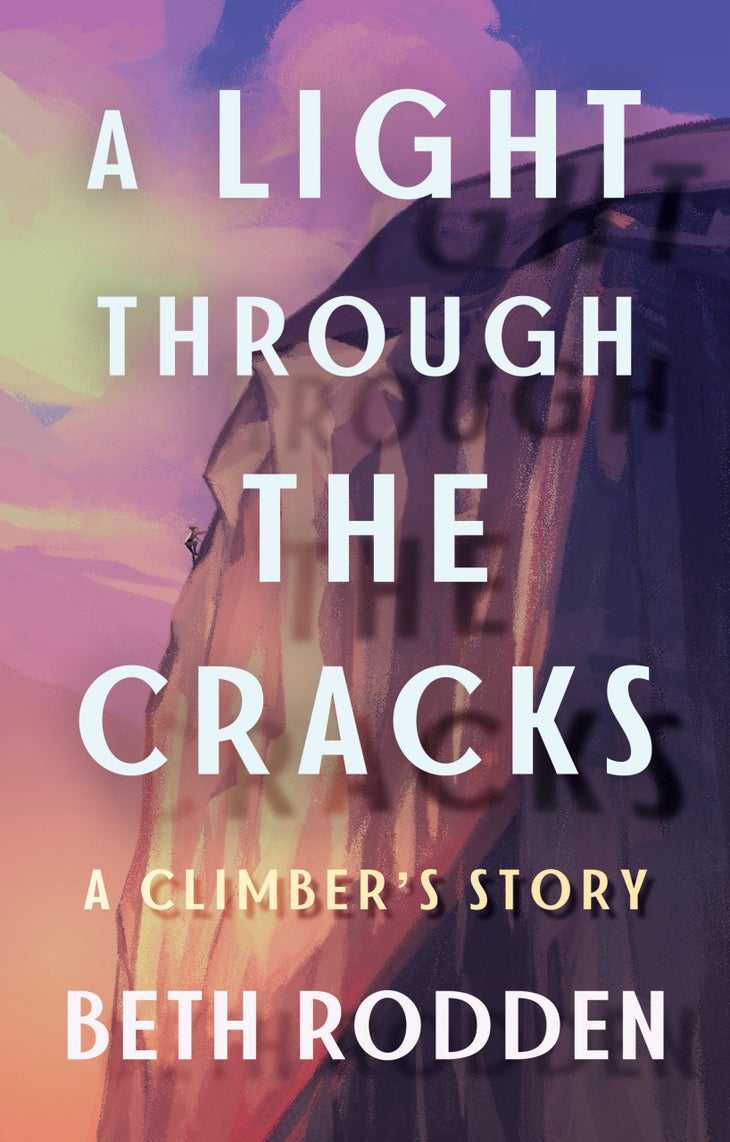

Professional climber Beth Rodden’s legacy extends far beyond her difficult first free ascents of Lurking Fear (VI 5.13c) and Meltdown (5.14c). As she progressed through her career, Rodden shone a spotlight on the unfair standards in professional climbing by advocating for equal pay among women and men. Her own story—of being one of the greatest free climbers in America—was a powerful argument for making her case.

Writer, climber, and podcaster Fitz Cahall staked his entire career on the belief that the best stories weren’t necessarily about the hardest sends, but rather the powerful, elemental human experience of turning wild dreams into reality.

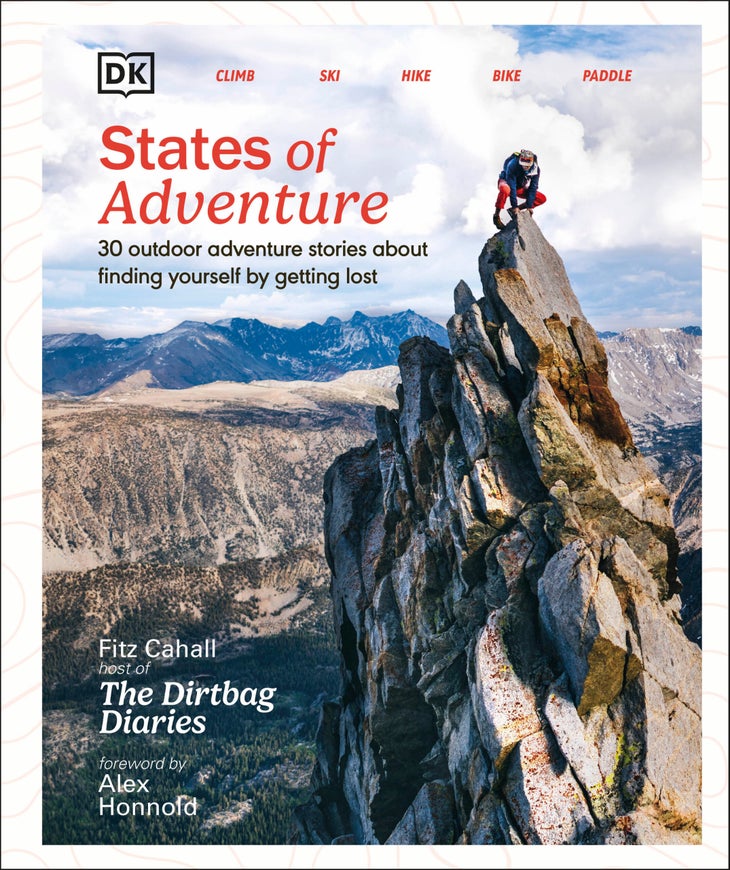

In the last year, each released their first book. In the unflinching A Light Through the Cracks: A Climber’s Story, Rodden dives into her kidnapping along with her then-husband Tommy Caldwell while on expedition in Kyrgyzstan, their subsequent escape, and the aftermath of post-traumatic stress disorder as it followed her into adult life and motherhood. Cahall’s State’s of Adventure: Stories About Finding Yourself by Getting Lost plucks 30 of his favorite stories from the last two decades of the Dirtbag Diaries, the beloved original outdoor podcast, and weaves them into a blueprint for a life lived with purpose, meaning, and taste for Type II fun.

The duo sat down to chat about climbing and the power of storytelling to inspire a new generation of climbers. The following is a lightly edited excerpt from that conversation.

**

The conversation

Cahall: I remember being around a campfire or a climbers’ table, listening to stories of expeditions and walls. It struck me how badass these people were. I thought, “Could I be like that someday?” That memory is so vivid—hearing tales of people putting up new routes and wondering if I could ever do the same. Did you have that experience?

Rodden: For me, it wasn’t a campfire but the gym. Back then, gyms were small and intimate. The community wasn’t that big. Everyone knew everyone. Mentorship was more of a thing. The climbers that I looked up to in the gym would come back from big trips, and I’d be bouldering alongside them, amazed. “You did that? Thirty feet up? That’s insane!” [Laughs] Slowly, they began taking me outdoors, and I understood more. But initially, it was the gym that gave me a sense of what you could do in the climbing world.

Cahall: Beth, was there a moment when you thought you could attempt something big?

Rodden: I started climbing in ’94, and that was right around the time Lynn Hill free climbed the Nose in a day. Every gym had that iconic poster of Lynn with the headline “It Goes Boys.” I’d look at it and think, “Could I ever do that?” Her poster inspired me to imagine the possibilities. It wasn’t immediate, but over time I began believing in my own potential.

Cahall: That’s so cool. It’s amazing how a single image or moment can have such an impact.

Rodden: Fitz, you’ve been telling outdoor and climbing stories for over 20 years. How does it stay interesting for you and your audience?

Cahall: Early on, I realized I couldn’t rely on my own stories forever. Doing something worthy—like a first ascent or a big trip—takes effort and time, so storytelling had to go beyond just me. I’ve always been fascinated by people who take an idea and turn it into something real. There’s something elemental about climbing stories: they’re about imagining something impossible and making it real.

I also love how our community has evolved. Twenty years ago it was hard to find a home for a story that wasn’t just about a pro climber. Our community has so many rich experiences, backgrounds, and ways into it.

Rodden: How do you decide who to feature on your podcast? How do you find people with compelling stories?

Cahall: Not everyone understands their own story, but some people just have a sense that what they’re doing is unique. They’re not just copying others; they’re carving their own path, pursuing the outdoor life in their own honest, thought-provoking way. Often, the best stories come from those with a deep sense of responsibility—to their community, family, or the environment—which adds this incredible tension. That’s what I’m looking for.

Beth, your story has been told by others before. Why was it important for you to write your own book?

Rodden: At first, I didn’t feel the need to tell my story—it wasn’t about setting the record straight. But once the book was done, I realized how important it was to share my experiences in my own words. Most stories about me had been told by men, who were often friends, but they inevitably added their perspective. Writing the book allowed me to express the nuances of my experiences on my own. At first I didn’t think that was a big deal, but towards the end I realized that it was freeing—my story, my voice.

Cahall: Was it daunting to undertake such a personal project?

Rodden: People often say it’s brave to be open and vulnerable, but once you own your story, it feels liberating, not heavy. The daunting part was not knowing how to write a book. Thankfully, I had incredible support from my editors. Writing about events like Kyrgyzstan or my divorce could be sticky, but once I started, it became easier.

Cahall: Do you think journalists or filmmakers avoided asking deeper questions in the past?

Rodden: For a long time, climbing media focused on the surface—the shiny, digestible stories. That’s changing now, but back then, people weren’t always interested in delving deeper. They didn’t want to ask those questions. It’s refreshing to see more complex, human experiences and stories being shared today. That’s something that’s changed for the better in the last decade.

Have there been moments when a story completely surprised you? Like where a story went in a completely unexpected direction?

Cahall: Definitely. Sometimes you approach a story with expectations, and it takes a 180-degree turn. Occasionally, you meet someone who’s more eccentric than you anticipated, and you have to step back and maybe just let it go. But the biggest surprise has been discovering incredible stories from people who aren’t self-promoters. They’re often the most talented and fascinating individuals, quietly doing extraordinary things.

For example, Craig DeMartino. I met him through a simple email and down the road I got to witness him spearhead the first all-adaptive ascent of El Cap. It was so powerful to watch him run with that idea. I’ll never forget being a part of that as a filmmaker. It all came from a simple email exchange that turned into a friendship. I try to stay connected with people whose stories resonate deeply with me. I think that’s why I hesitate to call myself a journalist. It’s not just transactional for me; where someone comes on the Dirtbag Diaries and then I never think about that person. I value those relationships and enjoy watching people’s bigger journeys unfold.

Beth, did it ever feel like you were writing climbing’s history during the peak of your career? There was a period where you were doing these groundbreaking ascents in the same way that Lynn Hill was. Routes like Meltdown took years for other climbers to repeat. Lurking Fear still hasn’t been repeated as a free climb. Did it feel like you were writing the bigger story of climbing?

Rodden: Not in the moment. Now maybe. At the time, I just felt like I was following in the footsteps of giants. In hindsight, I see how some of my ascents, like Meltdown or Lurking Fear, became part of Yosemite’s lore. But even now, I’m more focused on championing others. Climbers like Babsi Zangerl and Jacopo Larcher are rewriting history with their incredible achievements—and they’re doing it with humility and normal jobs. Those two—talk about people that don’t have an ego or self promote. They’re just machines up there. They’re writing that next chapter right now. It’s inspiring.

I think about the past too. Sometimes when I’m at hanging belay I’ll think about the early climbers with no leg loops, doing these incredible ascents in boots and in swami belts.

Cahall: It’s almost like they were going to space, it was so out there.

Rodden: Absolutely. Their achievements, often with minimal gear, are mind-blowing. Climbing multi-pitch routes in mountain boots or without leg loops—it’s hard to fathom. The risks they were managing. They weren’t just bold; they were extraordinary athletes. There are things they free climbed back then that are still difficult for modern climbers.

Fitz, climbing has a rich tradition of storytelling. Why do you think that is?

Cahall: I think it’s partly the drawn-out nature of climbing. Unlike a ski run that lasts seconds, climbs can take days, weeks, or even months. There’s time for reflection and problem-solving, which lends itself to storytelling. Climbing’s roots—from the Alps to Yosemite Valley—are steeped in epic journeys that resonate deeply.

Rodden: It’s also such a cerebral sport. Every climb requires problem-solving unique to the individual. That’s fascinating to share and learn from. It’s about how each person approaches challenges differently, looks at the risk differently. There is no one way.

Cahall: Exactly. Even climbing with my kids highlights this. Our body types and styles are so different, yet we’re tackling the same problems. It’s a great metaphor for the diversity of approaches in life.

Beth: I also think the climbing world has also valued storytelling more than say snowboarding or kayaking or biking. So I wonder if it’s not also a reflection of what the climbing industry and community values.

As a storyteller, have you ever felt like you were living through others’ experiences?

Cahall: In the beginning, the craft of storytelling felt like its own adventure. There was a period when I woke up every day with the same excitement I used to feel for climbing. But over time, I realized I needed to maintain my own connection to the outdoors. Recently, I rode my bike through Baja Mexico with some friends, and it made me remember how important that is in my own life. I don’t want to live vicariously. Seeking out experiences that challenge us is something that helps us all grow.

Rodden: What excites you most about storytelling right now?

Cahall: Tackling complex projects, like multi-episode podcasts like the Dope Lake or Cerro Torre stories we did on our Climbing Gold podcast, feels like the 5.14 of storytelling. It’s challenging and rewarding to create something that’s both intricate and impactful. I love projects that push me. How about you?

Rodden: Honestly, I’m looking forward to a break after the book. It’s nice to have some space and see where inspiration strikes next.

Cahall: Those voids, spaces, often lead to the best ideas. They’re vital to the creative process.