A trad climber on Mont Blanc attempts to bump a blue Totem and falls with the piece in his hand. Here's how to avoid that.

The post Weekend Whipper: Trad Climber Tries to Bump a Cam—Then Rips It Out appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Readers, please send us your Weekend Whipper videos using this form.

George Zhuravlev was high in the Alps and out of gear.

At more than 11,000 feet, Zhuravlev was leading a 0.3-sized finger crack on the fifth and final pitch of C’era una Volta il West (5.12a), a trad route on Rognon Vaudano below the Mont Blanc massif. He had just placed a blue Totem, but needed another one.

So Zhuravlev did what so many trad climbers do in this scenario: He grabbed his blue Totem and bumped it higher.

Unfortunately, just before he could re-place the Totem, his foot slipped. Zhuravlev flew off the wall, landing with a yell at 15 feet below his original position. When he landed near his belayer, he was still holding the piece he’d removed.

The dangers of bumping cams

Bumping—adjusting a cam to move it higher up—is risky for exactly this reason. While a cam is being moved, it’s not primed to catch the rock. Nevertheless, the move is very popular for trad climbers who accidentally run out of gear.

Jeff Jaramillo, the Head of Outreach and Gear Education at WeighMyRack, says that he most often sees people bump a cam when they get scared and want the rope above them. Zhuravlev’s case, he says, is a “prime example” of how bumping can end up extending a fall.

Not all bumps carry the same level of risk. For example, in offwidth climbing, climbers will often bump two pieces—one at a time—to ensure that one piece is always set in place to potentially catch a fall. When executed correctly, this strategy has the added benefit of keeping the rope out of the way of the climber’s knees and thighs.

Some gear is also easier to bump than others. According to Jaramillo, the design of a Totem cam, like the blue Totem that Zhuravlev was using, requires a lot of tension to load and unload. He finds that a stiffer cam, such as a Black Diamond C4 or Wild Country Friend, lends itself to bumping a bit more. “When it’s already placed in a crack and you give it a little bit of a push, it automatically starts to squish the lobes in a little bit,” Jaramillo explains, “so you don’t need as much pressure to collapse this style of cam as you do to collapse the Totem.”

Jaramillo’s advice for bumping

1. Bring more gear. “I generally try to avoid needing to bump a cam because that usually means that I’m not as prepared as I would want to be,” says Jaramillo. “For people getting into trad climbing, the things that you should look out for are, do I have all the gear that I’m going to need?” Don’t be afraid to add a few extra cams to your harness, especially if you’re new to leading trad.

2. Leapfrog your pieces. “Some people will backclean, where they’ll reach below themselves to grab a previous piece of gear—not the last one, but the one before it,” says Jaramillo. If the top piece is bomber, this practice minimizes the fall that could occur in transition.

3. Keep the piece in the crack. “If I was in [Zhuravlev’s] situation and really wanted that cam to be higher, personally, I would have wanted to just slightly disengage the cam, keep it in the crack, and push it upwards,” says Jaramillo. This move is slower but slightly safer than just pulling the piece out of the crack entirely and placing it higher. But it still doesn’t guarantee safety. “One of the things that happens when you fall is that you tense up, so you probably squish those lobes even more,” he adds. If you’re squeezing the lobes at all, assume that cam will be flying out with you.

4. Don’t bump until you’re totally secure. “When you are in a situation where you are bumping, the recommendation is usually to get to a spot where you’d be placing a piece again, and then bump to where you’d place the new piece,” says Jaramillo. Avoid adjusting your gear during a crux move or when you’re pumped.

5. Take. “If all you have is that one piece in front of you and you really need it to get higher, most of the time, I will just take,” says Jaramillo. “It’s so much easier to set the ego down for a second … if you’re scared or you’re pumped, and you’re right at that cam, take. Hang out for a second. Relax. Breathe. Get all the juices flowing where they need to be going again. Get thoughtful about where you’re going to go.” After a break, pull back on with a fresh mindset and bump the cam with full energy.

Happy Friday, and be safe out there this weekend.

The post Weekend Whipper: Trad Climber Tries to Bump a Cam—Then Rips It Out appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Thirty feet beyond your bolt? Above a cheese-grater slab? No thanks.

The post Weekend Whipper: A Slab Climber’s Worst Nightmare appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Readers, please send us your Weekend Whipper videos using this form.

Are you planning to climb a runout slab this weekend? After watching this week’s whipper, you might think twice.

Earlier this month, Vincent Krause and a friend set out to climb Schweiz Plasir at Switzerland’s Grimselpass. “I was nearly at the belay of the first pitch, 10 meters (32 feet) above the last bolt,” Krause told Climbing. “I touched the only wet spot on the slab with my right foot while I wanted to clip into the bolted belay.”

Krause slid down nearly half of the pitch before he spotted the last bolt he had clipped. “Because of the angle and the friction of the granite, I slowed down and I grabbed the last placed quickdraw to stop the fall and avoid hitting the small ledge below me,” he said. In the process, he scraped off a thick layer of skin from his right hand, both ankles, and also received burn blisters on his fingers.

We won’t pretend to know what the “right” course of action really was for this fall. Surely sliding down that slab for another 30 feet—and skidding into a ledge, or the ground—would have been heinous. However, we must point out that Krause was extremely lucky to not de-glove his finger by grabbing the quickdraw in this fall. Krause experienced the absolute best-case scenario for a fall of this length and style.

“I put on bandaids and a lot of tape and finished the pitch, but was unable to use most of my fingers on the right hand,” Krause noted. “I handed the rack to my climbing partner who then led the remaining 12 pitches, up to 6b+ (5.11a) to the top.” Krause followed using his left hand and primarily his right thumb, since his remaining fingers were just too painful to crimp.

Krause reflected: “I learned that the Magnus Midtbø quote ‘On slabs we are all equal’ is true and that a 5c slab feels harder than a 6a crack.”

The post Weekend Whipper: A Slab Climber’s Worst Nightmare appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Yes, I got my skull trapped in an wide crack roof. In Moab. In July. Choices were made.

The post How to Get Unstuck from a Crack, According to Someone Who Got Her Head Stuck in an Offwidth appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

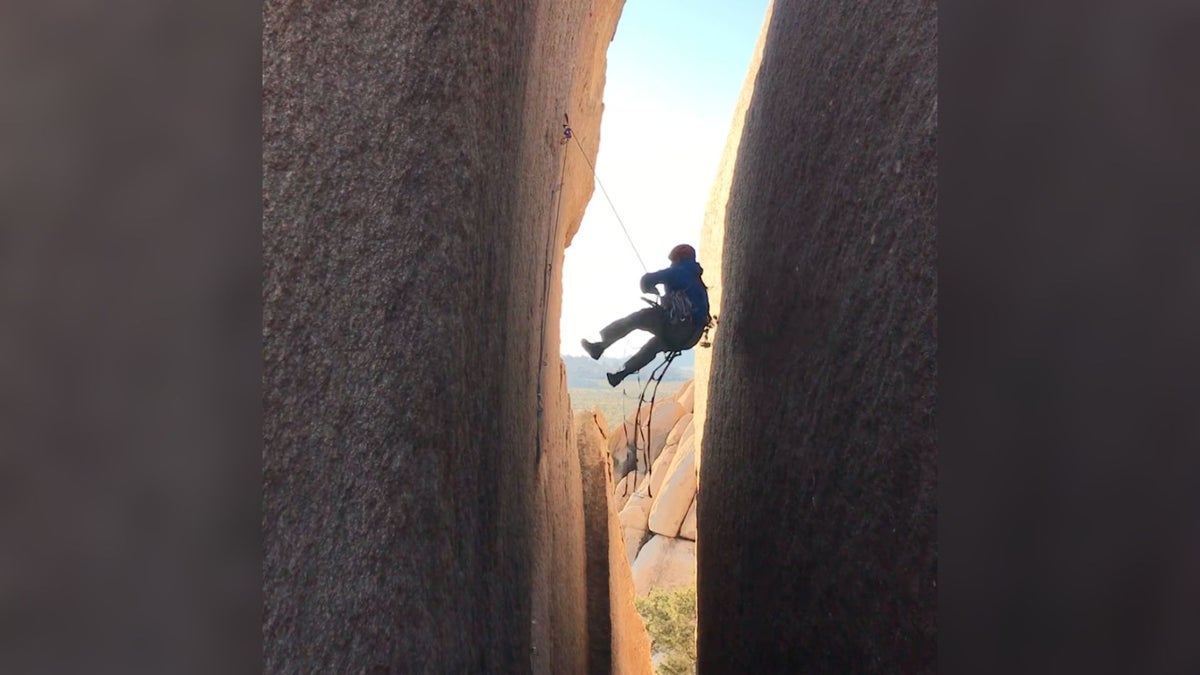

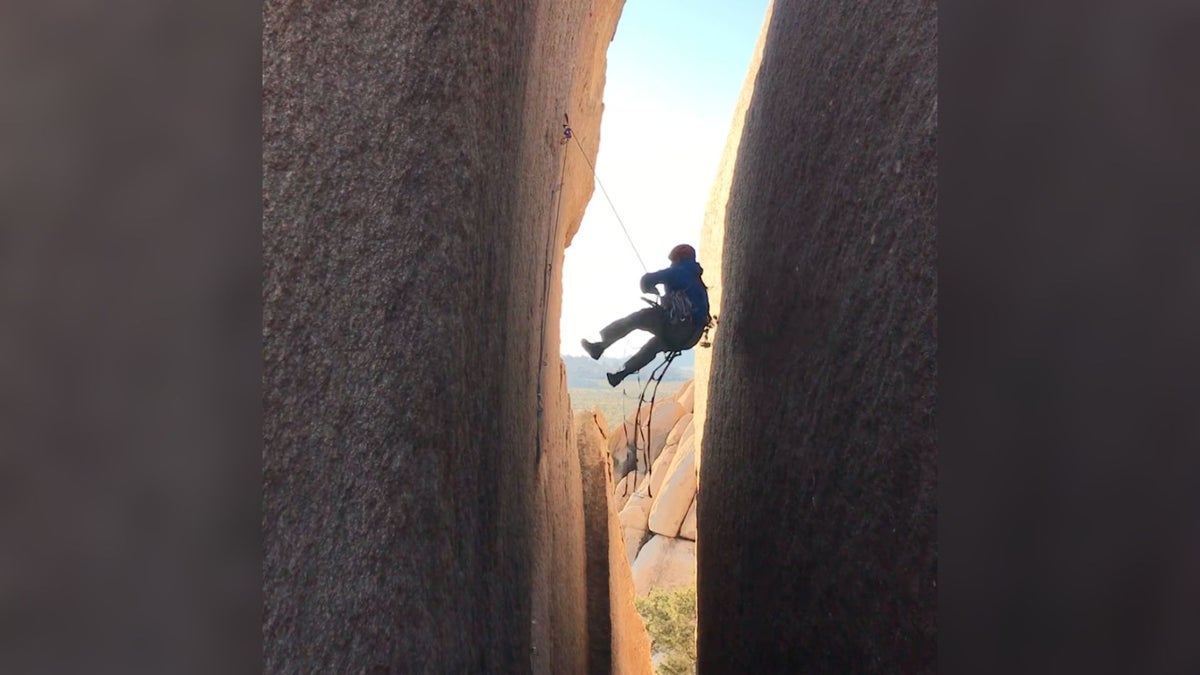

One hundred feet above the ground, I found myself stuck headfirst in Flavor Blasted (5.13-) in Moab, Utah.

This past summer, I have been training in my Moab garage for Century Crack (5.14b), a monster offwidth roof crack in the White Rim. Every four weeks or so, my partner and I have been climbing an offwidth outside to stay sharp. The crack trainer is great, but we wanted to make sure we were strong not just in the simulator, but on real rock.

That deload week, after hitting our training goals, we decided to try a local offwidth we hadn’t done yet, Flavor Blasted (5.13-). It’s a horizontal roof crack with shade, and it looked like a good challenge that wouldn’t totally wreck us for the next training week.

Flavor Blasted starts in a tight, awkward chimney below a long roof about the size of a #6 cam. The horizontal roof dips down before it expands into a number 7 cam size. Toward the end, as the roof turns vertical, it widens into size 8 territory for about 30 feet up to the anchors.

Climbing in Moab in July isn’t ideal, but we live here. You can’t change the weather, you just seek shade, hydrate, and do your best.

Getting Stuck

The common beta is to chicken-wing above the anchor, invert into the sixes, then layback the roof, making progress by pulling on holds along the left wall. After shuffling far enough into the sevens, you reach a hand jam, re-orient upright, and head into the tight vertical chimney.

I tried that beta on my first go that day, but it didn’t feel great for me. I have small feet, so instead of going feet first, I often do better leading headfirst with my upper body in tight,size-6 roofs, then progressing forward using a combination of arm bars, gastons, and leg bars. This route also had great footholds on the left wall, so I could push off those while driving my right shoulder into the opposite side of the crack. It felt much more efficient for my body, so I went with that beta.

The downside was that instead of skipping the tight, initial transition zone by inverting, I had to go through it. On my second go, I was adjusting beta and trying to stay tight to the wall when my head scraped along the interior and… wedged.

Right above my ears. Like a perfectly placed nut.

At first, I tried to stay quiet and work it out. I shifted forward, backward, up, down. Nothing. Finally, I said it out loud.

“This is new. My head is really stuck.”

Don’t Panic

I’ve learned that panicking never helps. Thrashing would only get me more stuck, so I stayed calm and focused on my breathing. I bumped a cam closer and higher above me and clipped my Petzl Connect Adjust to it.. My goal was to make sure I didn’t wedge myself into the constriction in a worse way.

I pulled the tether tight so I could rest. I love the Connect Adjust. It’s great for back-cleaning roofs, working beta, and in this case, precise emergency tethering.

I didn’t want my belayer to take, since the climbing rope might pull my body in a direction I couldn’t control with my head stuck. I reminded myself: If I got it in, I can get it out. That mantra helped me stay logical.

I tried shifting again, still no movement. Then I remembered to tilt my head.

That gave just enough clearance. I slipped free.

Watch Eden stay calm and dislodge her skull from the rock:

After hanging in my harness for a moment, it felt right to keep going. The plan was to refine the beta to avoid that same pinch point, so I back-aided to the belay. After a ten-minute rest, I sent the route clean using the same torso-first, non-inverted beta, this time remembering to duck my head.

Reflection

A helmet would have prevented my head from fitting in that tight space, but it also might’ve made the rest of the route impossible to fit. The vertical section is so tight it could’ve been a liability, which is why I chose to go without in the first place. In retrospect, maybe the only real lesson is this: Don’t climb offwidths.

If something goes wrong, breathe. Stay calm. Self-rescue is the best rescue if you can manage it.

Ideally, you don’t get stuck in the first place. Helmets are cool, and I would’ve preferred my helmet to get stuck versus my skull. But if you do get stuck, keep your cool, and maybe you’ll wiggle free.

The post How to Get Unstuck from a Crack, According to Someone Who Got Her Head Stuck in an Offwidth appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

A 15-foot ground fall with, somehow, zero consequences

The post Weekend Whipper: An Expert Catch Saves This Climber from Serious Injury appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Readers, please send us your Weekend Whipper videos using this form.

If there’s one thing that separates a regular member of society who’s watched Free Solo from a real rock climber—who, let’s be honest, has probably also watched Free Solo—it’s the understanding that a rope does not equal 100% safety.

Conversely, a ground fall does not, 100% of the time, equal injury and death.

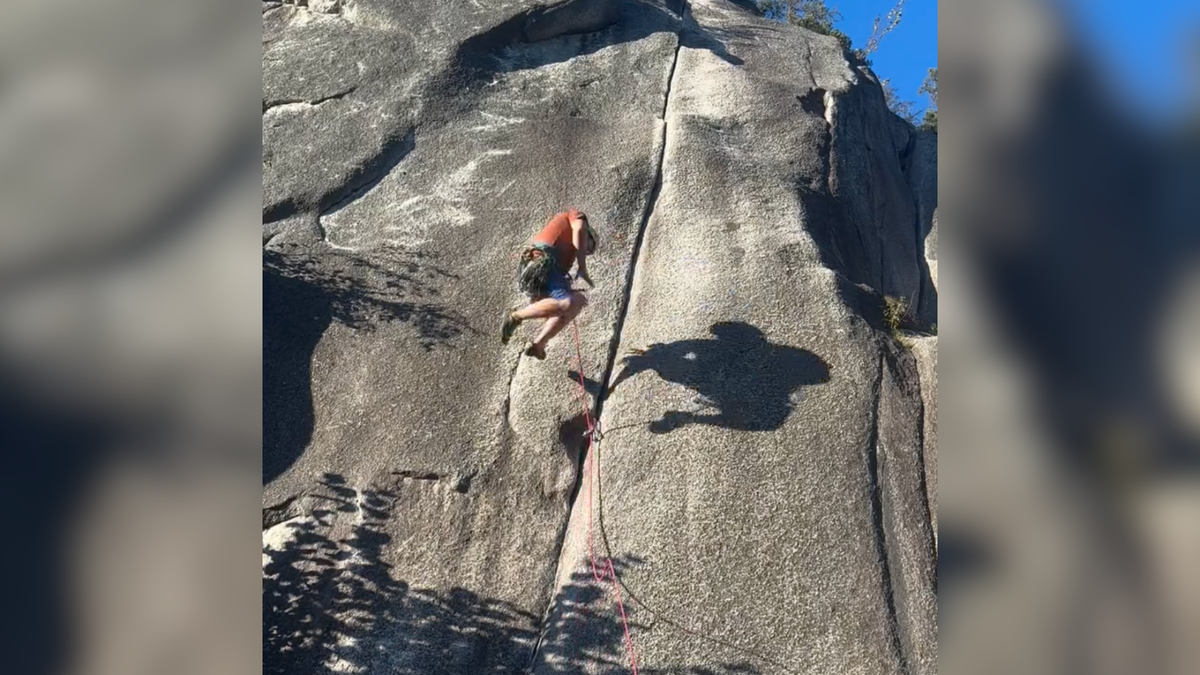

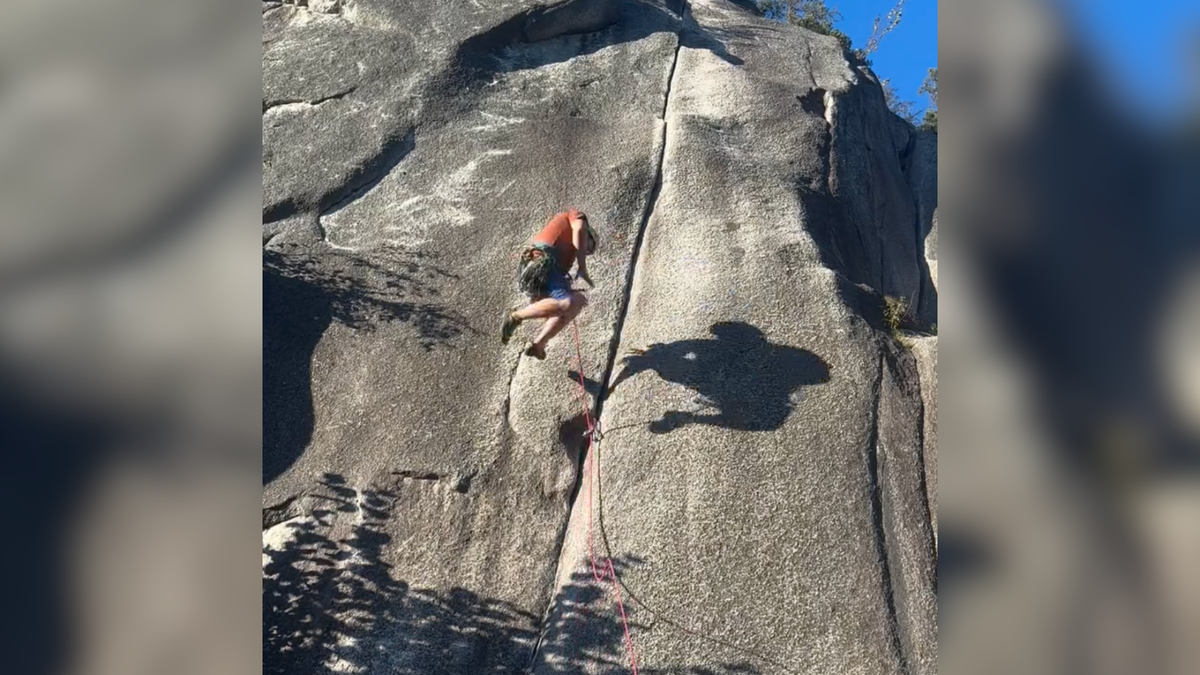

In this Weekend Whipper, Oregon-based climber Luis Armando experiences both of these truths at once.

He’s just starting up Partners in Crime (5.11a), a 100-foot finger crack in Squamish, British Columbia. Armando had tried Partners in Crime before, but he’d never fallen in the lower section. On this day, however, it was particularly hot and slippery.

By the time he had climbed about 15 feet up from the ground, Armando had placed two pieces, and he’d unclipped the lower one—a fine choice, as the lower piece wouldn’t be useful as protection. He’s five feet above his last piece when he slips.

“Falling!” he yells.

Armando’s belayer, Matt Gowie, has Armando on minimal slack, but even so, the rope doesn’t tighten until Armando’s feet have nearly touched the ground. Gowie, being lighter than Armando, is yanked five feet up into the wall.

It’s the soft catch, plus the fact that Armando manages to stay upright, that results in zero injuries from what could have otherwise been a bone-crunching drop.

Later, Gowie tells Climbing, “[Armando] jumped right back up like a champ … and continued to climb the route.”

Armando himself didn’t seem phased. “All and all, bad place to fall, great catch, and great route,” he says. “Will be back.”

Happy Friday, and be safe out there this weekend.

The post Weekend Whipper: An Expert Catch Saves This Climber from Serious Injury appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Yup, we don’t blame him for screaming.

The post Weekend Whipper: A 20-Foot Drop in First Person POV appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Readers, please send us your Weekend Whipper videos using this form.

In this Weekend Whipper, Colton Davidson gives us a premium GoPro display of his lead fall on Space Ranger (5.12-), a 90-foot classic on Lookout Mountain in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

According to Mountain Project, this sport route includes multiple stacked boulder problems. The description calls it both a “Southern-style trad route” and “quintessential to the aspiring hardman/woman’s tick list.”

Davidson agrees, calling it a “sick classic.” In this fall, he pumps out at the top of a runout slab section, taking 20-feet of air time before landing safely on the rope. We don’t blame him for screaming.

Lucky for Davidson, the route is extremely overhanging and he suffered no injuries. “I learned that it is important to be patient when trying hard, and even though a route seems intimidating, just going for it is the ticket to success,” he says. He adds that he ticked the redpoint the next day.

Happy Friday, and be safe out there this weekend.

The post Weekend Whipper: A 20-Foot Drop in First Person POV appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Check out this gnarly, 25-foot tumble.

The post Weekend Whipper: A Midair Somersault in South Africa appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Readers, please send us your Weekend Whipper videos using this form.

A few weeks ago, we looked at how climbers can avoid getting their foot stuck behind the rope and flipping upside-down.

Unfortunately, even with great footwork, it’s still possible to invert in mid air, especially during a huge fall.

In this week’s Weekend Whipper, Greg Wright takes a 25-foot tumble on “Explorer” (24/5.11c) in the Western Cape province of South Africa.

He’s nearly at the top of the route when his foot pops. Although Wright drops feet first, his last piece of gear was a few meters below him and off to the right, so his rope is off-center. He lands, lurches forward over the rope, and flips.

“I was knocked around pretty bad and found myself hanging upside-down over a 550-meter drop,” he says. “My shin was cut up, my shin and forearm were bruised, and I had a bit of whiplash. It was a rough fall.”

Luckily, Wright was wearing a helmet, and he didn’t end up with any broken bones.

The lesson? “I extended a piece of gear unnecessarily, which added to the length of my fall,” he says. Sometimes, the extra rope drag is worth it.

Happy Friday, and be safe out there this weekend.

The post Weekend Whipper: A Midair Somersault in South Africa appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Gate flutter almost never happens. But when it does, it’s terrifying.

The post A Quickdraw Unclipped Itself Mid-Whip. Here’s What Went Wrong. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Readers, please send us your Weekend Whipper videos using this form.

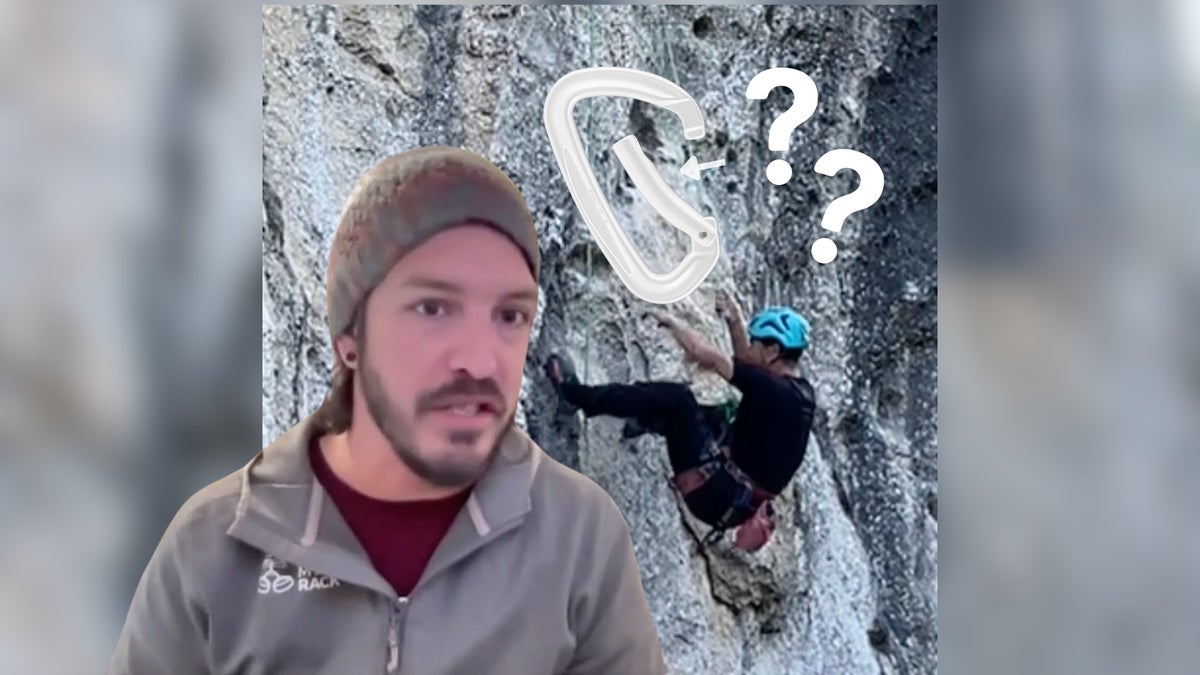

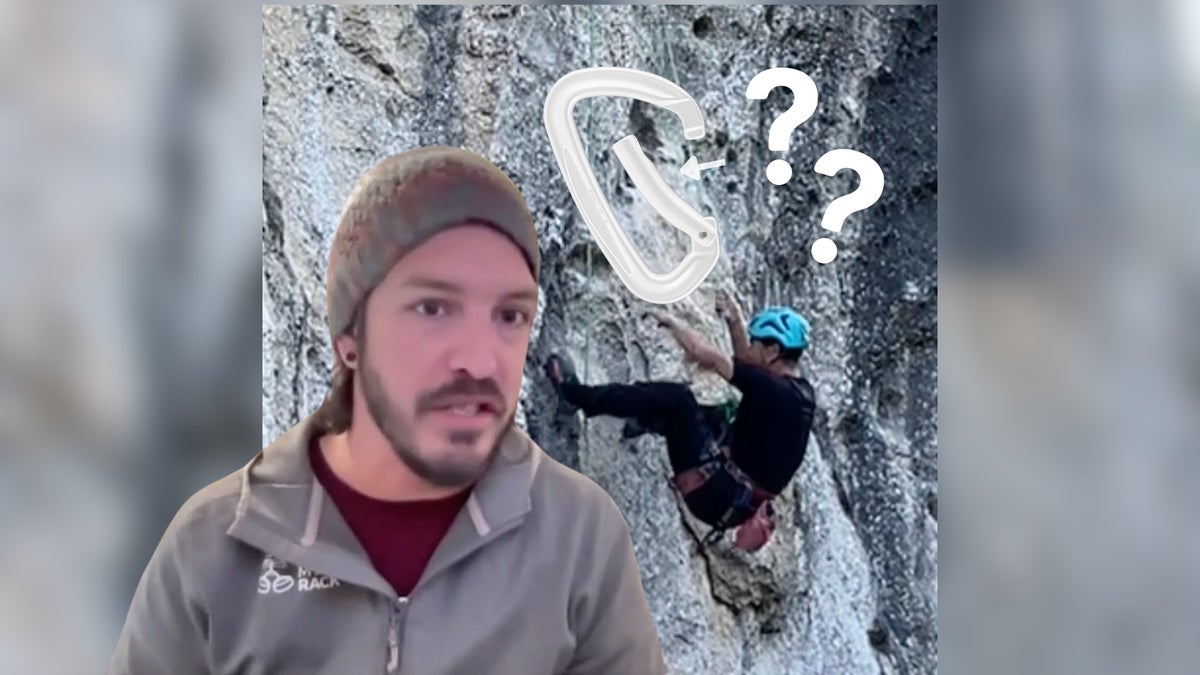

If you haven’t heard of “gate flutter,” you’re in the majority. This incident with a carabiner is rare to experience, and even rarer to catch on film.

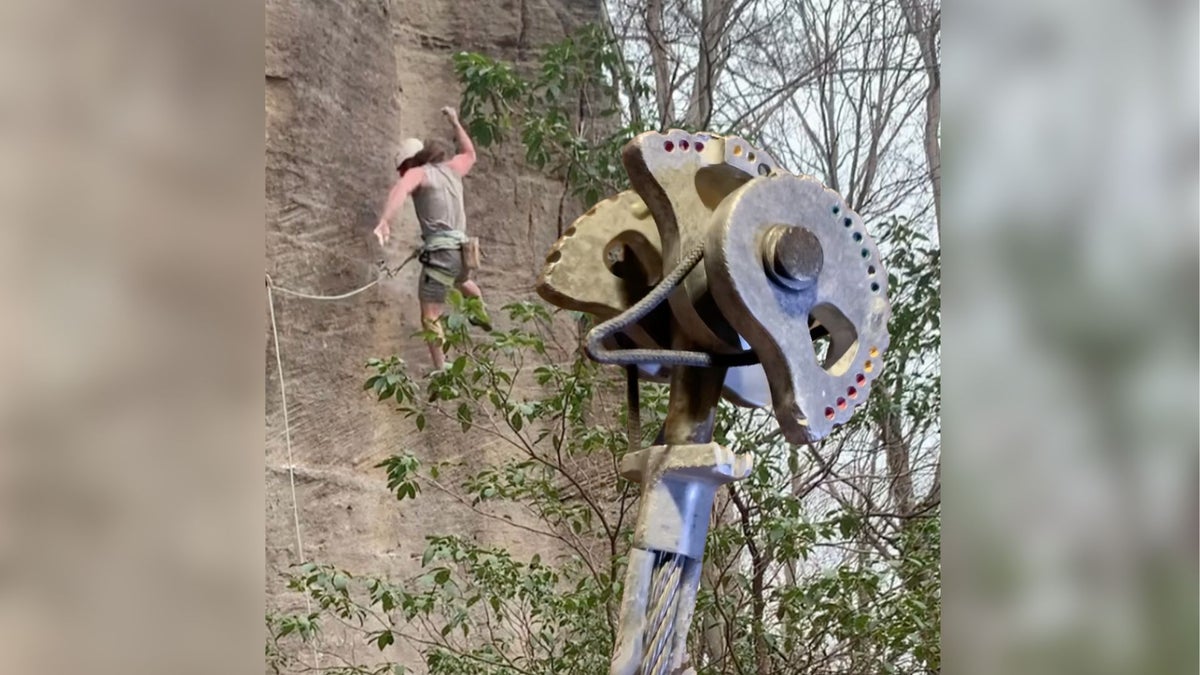

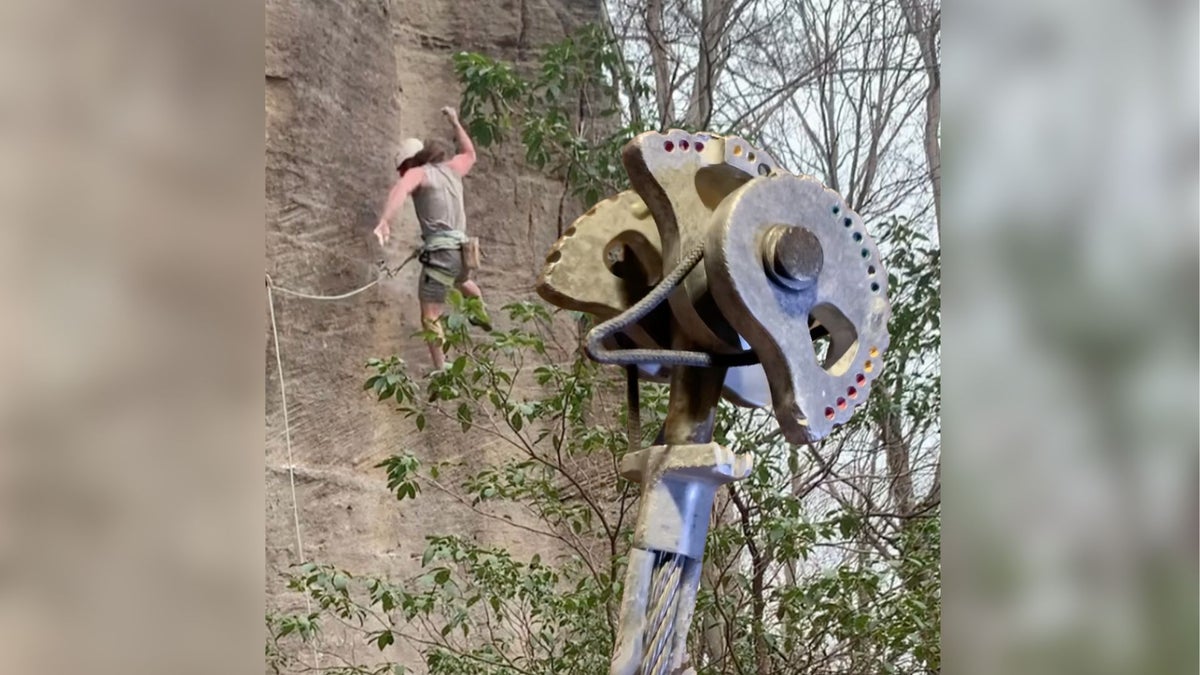

But when one climber falls on Singularity (5.12b), an 85-foot sport route in Yangshuo, China, we see a quickdraw come unclipped by itself up close.

Everything starts out normally. The climber is about two-thirds up the limestone route when he takes a hefty lead fall, landing in a soft arc about 30 feet below his fifth and final bolt. Physically, he’s completely fine. But when he lands face-to-face with his third quickdraw, he notices that it’s swinging in the air, ropeless.

A zoomed-in replay shows that the draw wasn’t back-clipped. Before he fell, the solid gate draw was closed around the rope. Then, during the fall, the rope bounced out—which means the carabiner’s gate must have opened on its own.

How did the quickdraw come unclipped?

A little disturbed, I hunted around the Internet for answers until I found a WeighMyRack blog post about gate flutter. According to the blog post, gate flutter happens when a carabiner’s spine smacks against the rock. At the right angle, and with enough force, this impact can cause the carabiner’s gate to bounce open. In the worst-case scenario, the rope could slide out of the quickdraw’s gate and render it useless to a falling climber.

Jeff Jaramillo, WeighMyRack’s Head of Gear Education and Outreach, confirms my suspicions. “Absolutely, I think what’s happening here is gate flutter,” he says over Zoom, “when a carabiner slaps up against the rock or a surface of some kind and the gate comes open temporarily. This is probably one of the best-filmed instances of this that I’ve seen.”

We move frame-by-frame through the video. Jaramillo points out that when the climber falls, he pulls at least twenty feet of rope quickly through the system. At high velocity, the friction of the rope pulls the bottom of the draw above the bolt. Any properly-clipped draw will be back-clipped if it’s flipped upside down, and that’s exactly what happens. However, this wouldn’t be an issue without this second part: the gate flutter. As it’s being flipped, the top of the draw hits the rock and its gate jumps open for a split-second. That’s just enough for the rope, which is still moving, to slip through.

According to Jaramillo, most of the people who know about gate flutter think that only solid gates, like the carabiner in this video, can experience it, but that’s not true: wiregates can still flutter open. “You’re probably going to see it more with the solid gate just because of the mass of the gate. There’s more potential energy that can be built up with more mass. As the carabiner swings over and stops, there’s more mass that needs to go somewhere,” he says. However, gate flutter has been shown to still happen with wiregates.

As a trad climber, I’m used to the idea that a properly-clipped bolt is the most bomber protection available. And while this climber had two other bolts above him, the idea that a healthy, perfectly-clipped bolt could become useless in an instant is an uncomfortable thought. So how can people avoid this?

Tips for avoiding gate flutter

“Unless you’re the person who bolted this route, I don’t think there’s much you can do to avoid where this carabiner hit that wall,” says Jaramillo, “short of maybe choosing a shorter or longer draw. Longer draws have a greater chance of flopping around.” He recommends that route developers avoid placing bolts directly below tufas or bulges, where a carabiner is most likely to flip up and hit the rock.

Taking shorter falls, however, will minimize the risk of having the rope come unclipped. “If this fall wasn’t so big, there wouldn’t be that much rope moving through the quickdraw, so the quickdraw wouldn’t have had time to get all the way upside down like it did,” he says.

Another precaution is using a locking carabiner at the end of the draw. This could take significant time and energy on lead, but would ensure the rope doesn’t escape.

Thankfully, gate flutter is still incredibly rare. “[Whether you’re] sport climbing or trad climbing, you’re in a system, and there are multiple pieces for a reason,” says Jaramillo, “so if you’re worried about one particular piece coming undone, I would say the pieces lower to the ground that could result in a groundfall would be the ones that I’d be worried about. That’s why I’m seeing more people locking the first or second draw if that’s a concern for them.”

Happy Friday, and be safe out there this weekend.

Original video credit: Mou Ding

The post A Quickdraw Unclipped Itself Mid-Whip. Here’s What Went Wrong. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Fresh from the Alps, Fay Manners gets some air time.

The post Weekend Whipper: Ripping Cams in a Swedish Finger Crack appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Readers, please send us your Weekend Whipper videos using this form.

Fay Manners has had a busy winter.

After ice and snow climbing in Scotland, putting up the first ascent of Apollo 13 (5.12+, 13 pitches) in Patagonia, and opening two new ski lines in the Alps, the British alpinist drove to Sweden this month to focus on single-pitch trad climbing.

As part of her warm up for rock season, Manners attempted an onsight of Trampoline (grade 7/5.11b) at Brodalen. This moderate crag in Bohuslän is known for its short approaches, rose-colored granite, and more than 1,000 single-pitch routes.

She was midway through the 80-foot climb, in a 10-foot finger crack stretch, when she placed a .5-sized purple totem—one that didn’t quite fit.

“I put it in when I was pumped and it was the wrong size,” she says, “but I didn’t have the energy to change it to a smaller size, so [I] just carried on.”

When Manners slips out of the finger jams, the purple Totem pops. Her five-foot fall extends to 15 feet, but the very next piece—also a purple Totem—catches her as she swings into the wall, feet first. Compared to most Whippers we’ve seen, it’s a gentle fall.

Manners says she intends to stay in Bohuslän for a few weeks to climb more granite trad routes. We can’t wait to see what’s next for her.

Happy Friday, and be safe out there this weekend.

The post Weekend Whipper: Ripping Cams in a Swedish Finger Crack appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

A narrow miss in an even narrower slot.

The post Weekend Whipper: First Trad Fall … in a Chasm?! appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Readers, please send us your Weekend Whipper videos using this form.

A climber’s ideal first trad fall—or, at least, the safest possible first trad fall—takes place on bomber gear with a clean landing.

That wasn’t quite the case for Joshua Johnson, who decided to take his first-ever fall on gear on Heart of Darkness (5.11a), a popular warm-up in Joshua Tree.

Heart of Darkness ascends a 40-foot splitter up a chimney that’s too wide for a full-body bridge. That means any climber who leads it risks hitting the back of their head on the wall behind them.

According to Johnson, he “aided up the route, built a nest” of several pieces close together, then “placed a single .5 above the nest, climbed to the anchors, and let go.” Presumably, his goal was to test the effectiveness of his .5 cam placement with a lead fall.

Luckily, when Johnson removed his personal anchor system and dropped from the anchors onto the .5, he absorbed the 25-foot drop with bent knees and perfect form. His .5 held, and his friends erupted into cheers.

If he had leaned back slightly further, his first trad fall might have ended in a hospital stay. Instead, Johnson’s head misses the chimney behind him by about a foot, while the extra cams on his harness brush the rock. Even though he’s wearing a helmet, we probably would have chosen a different route to test our gear on, with less potential for a back-of-the-head concussion or giant back contusion.

Happy Friday, and be safe out there this weekend.

The post Weekend Whipper: First Trad Fall … in a Chasm?! appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

How to not flip upside-down

The post Weekend Whipper: Lessons in Lead Footwork With Michaela Kiersch appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Readers, please send us your Weekend Whipper videos using this form.

It’s a normal day for Michaela Kiersch. The 30-year-old professional climber—the first woman in the world to send both V15 boulder and 5.15 sport—is trying one of the hardest routes in California: Everything is Karate (5.14c/d) in Pine Creek Canyon, near Bishop.

Unlike most of Kiersch’s recent big-name projects, this route ascends a sloping seam, requiring what she calls “ultra tech climbing” and finger locks.

“This style is not an obvious strength for me,” she writes on Instagram, “so it’s been cool to see progress every sesh.”

Kiersch is midway up the 70-foot route when she sticks the crux move and “bobbles the feet,” as she describes it. She’s about to take a fall—and from our perspective, she’s in a precarious position. She’s five feet above the last bolt and her feet are just a few inches from slipping under the rope. In past situations like this, we’ve seen falling climbers catch their ankle in the rope and get flipped upside-down.

But this is where her experience as a sport climber shows. When Kiersch falls, dropping at least 15 feet from her last extended draw, she’s careful to keep both her feet on one side of the rope—the side she’s going to fall toward. By the time she whips out of the frame, the rope is safely in front of her.

Some climbers try to keep the rope between their feet, but that’s not the safest technique for lead climbing, especially on a diagonal. It’s an easy way for the rope to get wrapped around your ankles or legs, which can lead to a flip whip. Instead, we recommend keeping the rope in front of your legs at all times.

Happy Friday, and be safe out there this weekend.

The post Weekend Whipper: Lessons in Lead Footwork With Michaela Kiersch appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

On ‘Blockage Project’ (5.13+) in West Virginia, a guidebook author accidentally sacrifices a cam for a second attempt.

The post Weekend Whipper: Black Metolius Cam Explodes on R-Rated Grit Route appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Readers, please send us your Weekend Whipper videos using this form.

In this Weekend Whipper, Andrew Leich is on his second redpoint attempt of Blockage Project (5.13+ R), a 40-foot gritstone trad route in Cheat Canyon, West Virginia. It’s an area Leich knows well—he’s the author of two guidebooks to Cheat Canyon.

About halfway up the route, Leich plugs a Black Metolius Master Cam—his third piece—into a .75-sized slot. He’s moving carefully up the sloping crimps, but his hands are beginning to sweat.

“I kind of let the nerves get to me, and I had lost some skin on my first attempt,” he tells Climbing. With the Black Metolius at his waist, Leich feels himself losing friction. He lets out a roar of effort, then slips off.

At first, it seems like Leich will take, at most, a three-foot fall. But Blockage Project is rated R for a reason.

Instead of catching him, the Black Metolius explodes out of its slot. Leich tumbles about 15 feet, swiping a tree branch and swinging into his belayer’s shoulders. He lands just three feet off the ground.

When he catches his spinning cam, he finds that his initial one-foot fall broke part of the Black Metolius. Specifically, it damaged part of the aluminum clasp, which holds the 13mm webbing that retracts the cam lobes, snapped off, leaving half the cam unable to retract.

“Unfortunately now, I can’t try it [again] until I buy a new cam,” says Leich, adding that the existing rock slot now has a broken edge, but will still fit gear.

Happy Friday, and be safe out there this weekend.

The post Weekend Whipper: Black Metolius Cam Explodes on R-Rated Grit Route appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

When this climber falls, the belayer takes flight.

The post Weekend Whipper: Does This Count as an Upward Deck? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Readers, please send us your Weekend Whipper videos using this form.

In this Weekend Whipper, Tara Miller is belaying on Keep Your Powder Dry (5.12b)—a steep, 75-foot line in Red Rocks, Nevada—when her climbing partner’s fall pulls her straight up into the roof.

“He fell. I flew,” she tells Climbing.

When Miller’s partner pumps out from a few feet above the fourth clip on the rightward traverse, Miller gets pulled about 12 feet up while the climber swings down and back toward her. Falling with outstretched feet, both climbers nearly perform a foot high-five in mid-air.

As the climber swings back, he lands via a soft slide on the ground. Meanwhile, Miller proceeds upwards and impacts the sandstone roof with her head. (Luckily, both climbers are wearing helmets).

Miller speculates that the massive whip was due to their weight difference, 150 lbs. vs. 98 lbs., plus the momentum of the fall. “I’ve never been pulled into the first clip before,” she says. “Time to buy an Ohm.”

An Ohm, indeed, may have saved Miller from being pulled into the first bolt. Designed for climbing partners with significant weight differences, the assisted braking device is placed through the rope at the first draw and adds friction in case of a fall. In lieu of an Ohm, she could also build a ground anchor next time.

Either way, we commend Miller for her totally unfazed reaction—and for keeping her hand on the brake strand through it all.

Happy Friday, and be safe out there this weekend.

The post Weekend Whipper: Does This Count as an Upward Deck? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>