The clash between guidebook authors and climbing apps raises a bigger question: what do we lose—and what do we gain—when beloved print traditions go digital?

The post Can Climbing Guidebooks Survive the Digital Age—and Do They Need To? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

A boulderer in the desert

Picture, if you will, a lone boulderer with a pad strapped to their back, hiking across public lands, in some familiar place in Southwestern America. Scattered sagebrush, pieces of obsidian, and manzanita dot the desert as their approach shoes kick up dust on the trail beneath them. The pad makes scraping sounds as they turn to fit their body between a scrub oak and a boulder. Rounding the boulder, they look up and find their line. A condor grunts overhead as the boulderer tosses their pad on the ground and pulls out their phone.

They sit on their pad and watch beta videos while assessing their own body metrics and wondering if they have the ape index to reach the crux the way a user on their screen did. They set their phone up against a creosote bush to film themselves at the perfect angle, then they swap shoes, chalk up, and give it a burn. They top out and pump their first for the camera. When they get down, they log their send and upload their video onto the app. A gray fox watches a roadrunner as they scroll around for more problems on the boulder.

This portrait of the present plays out every day across hundreds of climbing areas. Jump back 20 years, and a paper guidebook and flip phone would be out. Jump forward 20 years, and, well, if researcher and Google’s AI Visionary Ray Kurzweil is correct, the Singularity will have taken place, and our lone boulderer will be some half-human, half-AI machine potentially crawling backward up V25s. The only recognizable element will be the boulder. Maybe the creosote bush will still be there.

In twenty years, there undoubtedly will be a whole host of new conversations concerning ethics and AI in climbing (Can it be used in comps? If using AI to develop a new area, does it get a FA credit?) and other aspects of human life. But, for now, we’re in the digital age. As apps progress, the paper guidebook endures. But, can it hold on—and should it? A recent, very public battle between a guidebook author and popular climbing app spotlights where physical guidebooks might someday get lost, and who is determined to keep them alive.

Common courtesy

In 2008, middle-school science teacher David Lloyd was living in Lander, Wyoming, when his friend Steve Bechtel, who had previously written a bouldering guidebook on the Wind River Range, suggested that Lloyd write an updated version. “He said I was so much more into bouldering than he was,” Lloyd tells me. With Bechtel’s permission, Lloyd went to work. He recruited graphic designer Ben Sears to do the layout, and they shelled out $8,000 for a run of glossy pages. “It was really pretty, and people liked it,” he says. “But it took four years to make our money back.”

Lloyd was on the board of the Central Wyoming Climbers’ Alliance (CWCA), and he sought their advice on whether he should follow his Wind River Guide up with another guide to The Rock Shop, a Lander-area bouldering destination. The other board members expressed concern that Lloyd would be moving to Grand Junction the next year and wouldn’t be around to help with any access and sanitation issues that might pop up from bringing in a new crowd. “So, I put the Rock Shop guide on hold and moved to Grand Junction the next year,” he says.

Years later, as climbers often do, Lloyd sold his house and most of his belongings in Grand Junction and decided to hit the road in his Toyota Tacoma. “I wanted to live the dirtbag lifestyle,” Lloyd says. “For who knows how long—10, 20 years, even. But I ended up driving straight to Lander.” Lloyd lived in his truck and climbed at The Rock Shop for a few months before the guidebook bug bit him again. “I’d been gone a long time, and nobody had made a new guide. So, I thought, ‘Alright, I’m jumping back in.’”

Lloyd convened again with the CWCA, and this time, they begrudgingly agreed that somebody was going to have to make a new guide soon, and that someone may as well be Lloyd. Executive Director Justin Iskra gave Lloyd a tour around The Rock Shop and showed him all the new routes that Iskra had developed. “I got the CWCA approval, I announced it on Instagram, and I talked to everyone at the coffee shop on Lincoln,” says Lloyd. “So, I knew I was good to go.”

Lloyd feels that there are a few bare minimum requirements for starting work on a new guidebook. “If it’s out of print, someone can update a guide, or, if someone has doubled the number of problems, then it’s time for a new guide,” Lloyd explains. “But the new author should always reach out to the old author. It’s common courtesy in our world.”

In the past, Lloyd has been supportive when authors have reached out about updating his guides. Jake Dickerson and Steve Bechtel reached out to him recently, and they all agreed that it was time to update one of Lloyd’s old guides. Lloyd says he completely supported their project. “They’re locals, and Steve Bechtel makes great guides.”

But in 2023, Lloyd got a phone call to discuss a different type of guidebook. “KAYA called me, and they wanted to use my guidebooks for The Rock Shop and Unaweep Canyon,” Lloyd tells me. “That’s when it all started.”

The Feist Case

KAYA describes itself online as “an all-in-one climbing platform” that helps you find climbs and beta, with over 300 partner climbing gyms and digital guidebooks for nearly 115 North American destinations. It was created in 2019 by four founders, including TED Fellow and current CEO David Gurman.

“We were on a climbing trip in Fontainebleau when I shattered my ankle,” Gurman tells me over the phone. “I was sitting around a hotel room wondering what to do with my life, when co-founder Austin Lee asked me if I wanted in.” Gurman did, and KAYA began. KAYA was mainly known for tracking beta for indoor climbing problems, until in 2022, Gurman and co-founder Marc Bourguignon were walking through the woods in Squamish when they got lost. “We were trying to find this boulder problem, and we were like, ‘Dude, there’s got to be a better way.’ Just that little moment really inspired building out the outdoor guidebook side of it.”

Now, KAYA considers itself a digital guidebook publishing company. “We don’t aggregate guides,” Gurman says. “We don’t make them. We’re a publishing platform for guidebook authors to create digital guides.” The advantages of a digital guide are plentiful: climbers can save weight and space in their packs, contribute their own photos and beta to the community, and enjoy updates without having to wait several years to buy a new version. KAYA’s $9.99 per month Pro tier and payment model separates the app from what most climbers see as its main competitor: Mountain Project. The free website, now run by mapping app onX Backcountry, puts the onus on users to upload all data. They don’t pay guidebook authors to upload their guidebooks.

“I would say that the hardest part of all of this is actually getting the GPS data of all the climbing locations,” Gurman says. “OnX is betting that people will give it for free via Mountain Project. KAYA collects community-submitted GPS data as well, but is mainly guidebook authored.” He reports that guidebook authors are responsible for 85% of KAYA’s total climb taxonomy; the other 15% is from regular users.

In 2023, a mutual friend connected David Lloyd with KAYA to discuss digitizing his Unaweep guides. “I wasn’t somebody who wasn’t into tech, or digital guidebooks at all,” Lloyd tells me. “In our first meetings, they made it sound so good. They wanted all 2,250 boulder problems for Unaweep, which are my volumes one and two.” But then Lloyd got the contract. “I’m willing to pay myself next to nothing to make a guidebook, but for them to offer next to nothing for the work just felt like an insult.”

Lloyd reports that he was offered several payment options, which ultimately amounted to about $1 per boulder problem:

“Option 1: 40% revenue share, no cash upfront, for providing complete data on 2,250 problems and moderating content monthly.

Option 2: 30% revenue share, $500 cash upfront for providing data on 2,250 problems and moderating content monthly.

… continuing in this pattern until Option 5, which offered $2,250 cash and 0% revenue share.”

KAYA confirms the details to me, adding that they’ve since increased their revenue share with authors. Option 1 is now 50%.“This aligns better with our ‘author-first’ mentality,” Gurman tells me.

Lloyd called the folks at KAYA and let them know that he didn’t think it was the right time for Unaweep to go onto KAYA. “Rather than write back and ask what my concerns were, they just said they were going to reach out to other people and have them put it on. I said, ‘Yeah, go ahead. No one’s gonna do it at that price. It’s nine miles of canyon, and the opposite side is a 40-minute hike.’ And here we are, it’s 2025, and users have put like 150 problems up on KAYA, but no one has signed the contract and done the 2,250 problems.”

Two years after the Unaweep encounter, when the KAYA team decided that it was time to put The Rock Shop up, instead of calling Lloyd again, they called a different Utah guidebook author named Matt Desantis. Lloyd didn’t know DeSantis, so he felt like KAYA should have reached out to him about their plans to create the digital guidebook. Those are Lloyd’s rules, after all. “Matt did reach out to me about doing the guide,” Lloyd says. “But immediately after hearing from him, I went and looked, and the guide was already up. So, he reached out to me after already doing it. I told him someone from KAYA should have reached out to the CWCA, since they weren’t even that happy about me doing my first guide.”

Lloyd and his daughter took a close look at the KAYA Rock Shop guide and couldn’t help but notice that it had all the first ascents on it. “How did they get that information? Only through my book could they get that info,” Lloyd says. “Nobody but me had put it all together.”

Lloyd was frustrated, so he went public with his concerns. On August 13, Lloyd published a blog post called “The Trouble with KAYA,” which later made it to Reddit. KAYA responded publicly on Reddit and Lloyd’s Instagram.

“I didn’t accuse them of plagiarism, exactly, but I did accuse them of plagiaristic practices,” Lloyd says. “It’s reference data they’re copying—the route names, grades, first ascensionists.” DeSantis confirmed on Lloyd’s Instagram that he got the first ascent information from Lloyd’s guide, but added that he independently collected all of the pins, pictures, and trail data. He wrote on Reddit that he added about 70 additional problems not featured in Lloyd’s list.

But is that a legal issue or a moral issue? Or both? To answer that, I contacted Michael Cohen, an IP lawyer in Southern California who has represented Hyundai, Walgreens, and Kia and been quoted in The Wall Street Journal, BBC, and Los Angeles Times.

“When you’re plucking out bits of information,” Cohen tells me, “Facts and numbers and statistics, etc., that’s not protectable.” But subjective descriptions could be.

Cohen tells me about a case he studied in law school called “The Feist Case.” Somebody had duplicated exact information from a phone book and was getting sued. The court came back and said that there was not enough creativity involved in names and phone numbers for duplicating them to be considered a copyright violation. A copyrightable work needs to be an original work of authorship with at least a minimal degree of creativity. So what does that mean for guidebooks?

“If it’s just an app that’s extracting factual information,” Cohen concludes, “It’s very unlikely you’ll find a copyright issue.”

Cohen did not comment on the ethical issue.

What about the black oaks?

David Gurman says it’s a “bummer” that David Lloyd decided to air his grievances the way he did, and that KAYA has little recourse to get him to pull it down. He also says that he thinks it forced important dialogue in the guidebook space.

“We’re not trying to destroy print guidebooks,” Gurman tells me. “We’re not trying to destroy guidebook authorship. If anything, we believe that a Mountain Project-like format sucks up all the data and cuts guidebook authors out of the monetization equation. And we want to continue to support guidebook authors. If there’s no more monetary incentive to create guidebooks, then there’s no more guidebook authors.”

Lloyd doesn’t agree with that: “Guidebooks are a labor of love, not money. A huge motivation when I write these guidebooks is that I fall in love with a place and I want to share it. And I’m trying to write the guides in a way that leaves people with a good experience and helps them love the place, too. Guidebooks have done that for me. They’ve changed my life and helped me appreciate places so much more. When I get on an app, it’s just about individual problems. And you don’t know the history or get the feel for the area as a whole. Guidebook authors fall in love with a place and that’s what they’re trying to pass on.”

In the future, Lloyd thinks there will always be a place for printed guidebooks, but only at the major destinations. “Yosemite, Joshua Tree, Squamish … [in] the areas that people travel to, spending another $50 for a good guidebook won’t stop anyone. With the little local areas, KAYA will take those over.”

Gurman disagrees. He says the wave of digital is inevitable, but the death of printed guidebooks is not. Gurman has a giant bookshelf in his office that is filled floor to ceiling with guidebooks. “It’s just different use cases. People enjoy sitting down the evening before and flipping through guidebooks… there’s just something about the tactility of having what really is a tree in your hand and just feeling it and reading it. Getting away from a screen for a second. Which, I admit, is really important.”

I spoke to another guidebook author who works with KAYA for one area, but turned them down for another: SJ Joslin, the author of the Yosemite Bouldering guidebook. In January 2022, KAYA contacted Joslin about putting the Yosemite Bouldering guidebook on KAYA. Joslin wasn’t interested.

Both Joslin and their co-author, Kimbrough Moore, did, however, publish the digital guidebook for Golden State Bouldering with KAYA. “The Bay Area is a really tech-forward place, and people are interacting with apps all the time, so KAYA was more suitable for it,” Joslin says.

Joslin adds that what’s really important to the community of Yosemite is that people get out into nature, and the Park doesn’t get consumed by social media and technology. “By and large, Yosemite is the kind of place you should be able to check out and interact with people more than platforms,” they explain. The author didn’t want to work with KAYA on the Yosemite guide, and they sent KAYA literature from the National Park Service about the Wilderness Act as a response. The excerpt talked about preserving the wilderness character of wilderness areas.

Eventually, KAYA sent someone else to the Valley to gather information. “They ripped off all of our work,” Joslin tells me. “It stinks, because I know many of the people at KAYA, and I really like them as people. If you’re going to put a guidebook out there, you should do it with the support of the community. You have those awkward conversations with people you’ve been climbing with for decades. It’s a relationship. And if the community says no, respect that.”

When I present Joslin’s case to Gurman, he responds, “We thought SJ [Joslin] was going to moderate and potentially come on as the guidebook author. “We had a guy go there and collect the GPS data. We pushed ahead, thinking we were collecting data to work with SJ later.” Gurman admits that Joslin saw the data live in the app and thought KAYA was competing with them. “It was a draft, but we didn’t have a draft mode. So, to be fair to SJ, that’s what it looked like. But that wasn’t the intention. It really was to collaborate and proactively add information so we could work with SJ on it in the future.”

Gurman took down the Yosemite guide and apologized to Joslin and Moore in an email. He says that KAYA won’t publish Yosemite until they have a local author and moderator.

KAYA may not have initially listened to Joslin, but, to their credit, when the pushback got louder and they started hearing from mutual friends as well, they took the Yosemite guide down. Legally, it was fine. Ethically, they finally agreed, it wasn’t.

On September 25, 2025, after Climbing interviewed Gurman for this article, KAYA published a press release addressing their communications with several guidebook authors. They called visualizing the Yosemite data in the app “a crucial mistake.”

“What I want when people come to Yosemite,” Joslin says, “is to notice the black oaks, and how Indigenous people have been using acorns to get food for thousands of years. And how they’re still doing prescribed burns, and that there are frogs in the pond. Not just how to get beta on a boulder. That doesn’t convey at all if my work is just uploaded to some app.”

Erik Sloan, guidebook author of Yosemite Big Walls, The Ultimate Guide, and Rock Climbing in Yosemite, the 750 Best Free Routes, agrees that guidebook authors don’t get the credit they deserve. “I think they’re a pretty misunderstood breed,” he tells me over the phone from the Valley. “I’ve been self-publishing for 11 years, and it’s exhausting work. The books take up my whole garage, and it takes forever to break even.”

Sloan hadn’t heard of KAYA. He uses Mountain Project, and he likes it, but he doesn’t always trust it. “The comments and updates on Mountain Project are a cool element, and you’d think a bonus over physical guidebooks, but so many of them are wrong. Maybe someday ChatGPT can go through there and comment about which human comments are right and which ones are wrong.”

Back to the Singularity

If physical guidebooks are gasoline-powered cars, and AI is electric, that would make current climbing apps like onX and KAYA hybrid vehicles. A more efficient way to travel now, but soon to be outdated themselves. Placeholders, if you will.

In September 2024, Apple released its newest form of Maps, which now includes customizable trails in national parks. Currently, this threatens apps like AllTrails, Gaia, and onX more than it does the climbing space. But with the popularity of climbing rising, will Apple someday go vertical? And when it does, will it come for digital climbing guides, too?

I ask Gurman how KAYA, a company run by six climbers, plans to protect itself against AI from larger companies like Google, Microsoft, and Apple, but he seems unimpressed with the tech giants’ progress so far. “If Apple were able to somehow snag the GPS data for every notable climbing and bouldering route across the world, then the question would be, are there other augmentations to the data set that would make KAYA’s data more valuable? Like the ascent data, the suggestion engine stuff—height and reach, the beta videos, and the metrics that personalize in-app experience.”

I joke with him that maybe when the Singularity happens, KAYA can pivot to printing guidebooks. “That’s not even a joke,” he says. “We’ve been in discussions with several print publishers about doing that someday.”

Lloyd and I talk about AI as well, and though he admits that he “wasn’t too techy,” he has experimented with it. “I played with ChatGPT while trying to find The Multiverse (V14/15) at Neverland one time,” he says. “I heard some rumors that AI was pretty good at GeoGuessr, and I thought, Whoa, then it might be good at finding boulder problems.” He says it was hallucinating at first, but then it finally put him in an area that could have been the right spot. But without a guidebook, he couldn’t be sure.

The post Can Climbing Guidebooks Survive the Digital Age—and Do They Need To? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

A new app called Tip Your Setter allows climbers to tip their routesetters, but it comes at a cost.

The post Is This New Tipping App the Answer to Better Routesetter Pay? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Do you remember the scene in Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory when Wonka opens the door, and the kids get their first look at candy paradise? Wonka sings “Pure Imagination” and the kids all scramble around, eating whipped cream-filled mushrooms and colorful flowers. Your eyes were probably on the candy, but did you ever notice the rock walls in the background? The wall behind the chocolate waterfall looked like it had routes anywhere from VB to V2. Rock climbing gyms have always had a Wonka vibe—big open spaces with candy-colored holds and big fluffy mats to fall on. But there usually isn’t a top hat-wearing psychopath behind them, just an owner (or corporation) trying to make money.

Routesetters are a bit like the Oompa Loompas. Not because they have green hair or misshapen hips, but because they’re always off in the distance, working diligently behind a line of cones or rope. Pay no attention to the people behind the curtain. They also aren’t fairly compensated (were the Oompa Loompas paid in…candy?).

Climbing has explored how gyms compensate routesetters, and the topic of unionizing before, but New York climber and app developer Kevin Wang now invites climbers to help compensate routesetters more fairly by tipping them via his new app, “Tip Your Setter.”

With Tip Your Setter, routesetters can apply through the app to be added as setters to their applicable gyms. Then, theoretically, climbers can send a monetary “tip” to that setter if they’ve enjoyed their services. I emphasize theoretically, because I downloaded the app and found only four “tippable” routes in two gyms across the entire Los Angeles area. To be fair, the app is new, having just launched on Apple’s App Store on July 22.

But, even if every single routesetter on the planet set up an account on Tip Your Setter, is introducing tipping culture a good thing for climbing gyms? This question recently appeared on the Reddit /climbing forum, with the title “Tipping Culture Has Gone Too Far.” Hundreds of climbers weighed in, and the overwhelming majority agreed with the original poster. The top comment was: “Are we supposed to tip the same amount we tip our belayer?” Several people commented that “out-of-control tipping” seems to be an American problem.

“I’m so American, I even tip the auto-belay,” said one Redditor.

Gym climbing and outdoor climbing are not the same, physically or culturally, but many of their idiosyncrasies do carry over. Frugality represents one of those traits that bridge the gap from indoors to outdoors. (Look no further than the phrase “dirtbag,” a highly regarded term of endearment among our people). This app is essentially asking climbers to pay more for their gym memberships because the gym doesn’t pay its employees enough.

And what if introducing tipping culture to climbing gyms inspires owners to lower their employees’ hourly wages even more, as bars and restaurants traditionally do?

On Tip Your Setter’s website, it states that they take a 10% transaction fee for every tip. When it’s easy enough to Venmo your setter, or bring them pastries or beer, it’s hard not to believe that what we’re really introducing here is another middleman who’d also like to profit off the Oompa Loompas.

But make no mistake—it’s the creativity, talent, and experience of routesetters that make climbing gyms what they are. They deserve to be fairly compensated for their efforts by their employer. So, by all means (if you have the means), tip your setter. Tip the desk person who played Guns N’ Roses while you were trying to send your project. Throw some cash to Izzy Stradlin for being the most underrated rhythm guitarist of all time, or tip your journalist for helping you kill three minutes … but you don’t need any new apps for that.

The post Is This New Tipping App the Answer to Better Routesetter Pay? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

A 17-year-old free soloist ran away to Yosemite. One year later, his body was found at the base of Royal Arches.

The post The Valley Boy: How a Free Soloist Met His Untimely End in Yosemite appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

I. Base Camp

Sometime after midnight on June 6, Grant Cline finished up his shift washing dishes at the Yosemite Lodge. Much of his time was spent in the “pot room,” a steel trap of a room recessed deep within the Lodge’s Base Camp food court and surrounded by commercial sinks and Labrador retriever-sized stacks of trays. Grant turned 18 just the month before and was happy to finally have a job in the Valley. Now officially a man, he still retained his boyish good looks—sandy, overgrown hair with floppy bangs and rosy cheeks that often betrayed him. According to his mother, Grant was a bad liar.

He biked back to an Aramark employee housing area called Boystown, navigating the Valley by headlamp. Or maybe he didn’t use one. The night of June 6th had a waxing gibbous moon of about 80% illumination—more than half lit, but less than full. Sunlight and moonlight are tricky in the Valley. Its walls take up more than half the sky, and sugar pine and Douglas fir trees filter much of the light. Whether Grant used a headlamp or not is lost, but he was no stranger to navigating the night. He rarely slept, often going on climbing missions alone at one or two o’clock in the morning. “Some nights he’d come home, though,” his roommate Kelvin Pittman tells me.

All Boystown beds are thin mattresses rolled over springy twin-sized frames. Grant’s was easily found with posters of Alex Honnold, the Stonemasters, and Lynn Hill right above it. He kept his gear clipped neatly in various places and had random piles of Climbing Magazine issues. His favorite stories were the old Yosemite articles highlighting the scene in Camp 4.

Grant crawled into bed a little after 1:00 a.m. on June 6 and accidentally woke Kelvin up. “He’d been at work, and I was like, ‘How are you doing?’” Kelvin recalls. Grant read his Royal Robbins book for a while—shining his headlamp through his Nalgene to make sure he didn’t keep Kelvin up. Kelvin figured Grant was going to sleep for a couple of hours and then go climb, like usual.

“I was tired, so I didn’t ask him if he had any plans,” Kelvin says. “Then I fell back asleep. I woke up a few hours later, and he was gone.”

Grant left to do what he called “free solo recon” on Royal Arches (5.7 A0; 2,000ft), a Yosemite multi-pitch classic that he’d scouted once before, a few nights earlier. The first time, he free soloed up to the pendulum on pitch nine in the middle of the night, and then downclimbed the route, having slept on a ledge somewhere on the way down. On June 6, Grant’s plan was to free solo higher than the pendulum, and then downclimb the route again (when climbing Royal Arches, the pendulum rope can be tucked on the far side). Nobody saw him leave that morning, and he wasn’t seen for the rest of the day.

Two days later, on the morning of June 8, Grant’s neighbor and climbing partner, Chris Guzman, knocked on Grant’s tent cabin door. They had plans to climb up to Dolt Tower on El Capitan, but Grant wasn’t answering. His bike wasn’t there, either. Chris called Grant’s phone and left voicemails and texts, but he wasn’t responding. Finally, thinking he’d mixed his schedule up, Chris biked over to Grant’s work at the Lodge. Grant’s boss told Chris that Grant had been a no-show for two days now. “But [the boss] hadn’t bothered to tell anybody,” Chris says.

Chris, extremely worried at this point, remembers Grant telling him that he was going to scout out the Arches after work on Friday. He found Kelvin in Boystown, but Kelvin didn’t know where Grant was and hadn’t seen him for a day or two. But that wasn’t so strange: Grant didn’t sleep. He was always either scrubbing dishes until 1:00 a.m. or climbing. And Kelvin and his work schedules never synced up. If Grant didn’t have the day off, Kelvin would only see him for a ten-minute period in the middle of the night, between the dish scrubbing, reading, and climbing. But when Chris told Kelvin that Grant had been no-show at work for two days, Kelvin immediately felt his stomach tighten.

“That’s not right,” he thought. “That’s not Grant.”

A little after noon, Chris called 911 and spoke with Yosemite Search and Rescue (YOSAR). Dispatch sent an active member of YOSAR out to meet him, and he conveyed all the information that he knew. As the YOSAR team started an investigation, Chris and Kelvin gathered several other friends from Boystown and ran over to the Arches, where they searched and yelled out Grant’s name. Shortly after, two National Park Service (NPS) vehicles and an ambulance showed up. A pair of climbers were rappelling the Arches, but they hadn’t seen Grant.

When it got dark, the group returned to Boystown. Then, at 9:30 p.m., Chris’s phone rang. It was YOSAR. They’d found Grant’s body beneath the Cobra feature of Royal Arches, several hundred feet east of the first pitch.

II. El Portal Market

A little over a year earlier, in May of 2024, Maison Davis, a clerk at the El Portal Market, couldn’t help but notice a boy sleeping in his car in the store parking lot. El Portal is a border town on the west gate of Yosemite, and only minutes from the Valley floor. Maison had seen the boy a few days in a row before he finally asked what he was doing.

“He said, ‘Oh, I’m just climbing.’ Maison remembers.

The clerk asked the boy if he was working in the park, and he replied that he was too young and that he’d just turned 17. “I thought that was amazing,” says Maison. “Way to follow your dreams and make it out here so young.”

Eventually, Maison got to know the boy as Grant. He even started giving him the expired products he couldn’t sell: “Things like frosting, whatever. He’d come in in the morning and say, ‘What’s expiring today?’ He’d look around the shelves and point stuff out that would be expiring soon and say, ‘Hey, I’m coming back for that on Tuesday.’ So, we’d keep him fed.”

A month before, Grant had asked his parents, Jennifer and Jeff, if he could dirtbag for the summer in Yosemite. He was only 16 years old, so his parents said no. But the Saturday after school got out, the family’s golden retriever, Boris, woke Jennifer up early by barking and pawing at the front door. Jennifer looked outside, and Grant’s car wasn’t there. She ran upstairs to his room and found that he’d packed his things and left a note on the bed telling them he loved them.

Jennifer woke Jeff and they turned their phones on. Grant hadn’t switched Find My Friends off, so they could see exactly where he was. “He was already almost in New Mexico, which is a long drive from Dallas.”

Grant didn’t answer their texts until a little after Amarillo. But he confirmed he was okay. “We didn’t scold him or anything. We just wanted to make sure he was safe,” Jeff said. “We were more worried about the legality of it with him being underage.” They didn’t approve of the trip, but they felt like it would be more harmful if they made him turn around and come home. “So, we just said go for it, dude!”

“We had a safe word,” his mom adds. “And he had to text it to us every morning by 9:00 a.m., our time.”

Sleeping at the El Portal Market was a clever cheat code, not only because Grant could avoid park fees and time limits at Camp 4, but also because the market has free WiFi.

“He was so frugal and independent,” Jeff remembers. “I offered him money, but he said, ‘No, I’m fine.’ He knew how to take care of himself.”

With free Wi-Fi, Grant was able to text his mother their safe word every morning, but he also had something else up his sleeve: he was getting a jump start on his senior year by taking high school classes online. He was planning to graduate a semester early so he could return and work in Yosemite after his 18th birthday.

“The day before he left that first time, I went up to his room and helped him adjust his bike rack,” Jeff says. “It didn’t even dawn on me that he was actually going to leave. Later, I found out that his preplanning was amazing. Financially and everything. He knew his routes and how much he had to spend. He’d been planning it for a long time.”

Grant slept in his car in various places around the Market—often, just right out front. “Crashed out with one leg sticking out the window,” Maison recalls. “It was a tiny little Corolla, and he was a tall, gangly guy. He would recline the front seat and just be out. One time I asked him if his neck hurt, and he said, ‘Nah, it’s not too bad. I only wake up once or twice a night.’ He never complained.”

Maison and his girlfriend took Grant climbing a few times on that trip. Grant had only done some sport climbs and led in the gym, so Maison took him out to Highway Star (5.10a), a crack climb at the Lower Merced area. He set up a top rope and had Grant mock lead the route with gear, since he’d never placed any protection before. Grant placed a bunch of cams until he got one stuck and couldn’t get it out. “I had to go to work and didn’t want to be late, so I split,” Maison remembers. Unwilling to leave a piece behind, Grant drove to the Mountain Shop in the Valley and bought a nut tool so he could dislodge it, which he did. He returned Maison’s piece to him at the market and gave him the nut tool, too. “I thanked him for my cam and told him to keep his nut tool, but he wouldn’t hear of it. Made me take it,” Maison tells me. “I still have it.”

Maison also took Grant to Generator Crack (5.10c), a classic Yosemite offwidth. Maison only managed to get himself halfway up before waving the white flag, but Grant gangled and chicken-winged himself all the way up. “He did a bunch of weird moves that weren’t even real moves,” Maison told me. “I think he was pretty good in the gym, but had never touched rock. And it doesn’t really translate—especially to crack climbing. But he crushed it. He was strong, talented, and creative.”

Eventually, Maison clued Grant in on the showers at Camp 4. Then Grant found the bulletin board, and as a result, climbing partners and friends in the parking lot. “Once he figured all that out,” Maison said, “we’d only see him at closing for food or waking up in the morning before he split for Camp 4 again.”

One day in May 2024, Grant struck up an unlikely friendship at Camp 4 with longtime Valley climber Bronson Hovnanian. Bronson had just come down from climbing the Nose (5.9 C2; 3,000ft) when he ran into Grant and a bunch of climber kids from Camp 4 hanging out around the parking lot. Grant spotted Bronson and asked what he’d been up to: a NIAD, or Nose in a Day, in four and a half hours.

“[Grant and the others] were young, but so curious,” Bronson recalls. He hung around for a while and answered questions. “Grant was a really cool kid. He’s just that quintessential story about a young climber coming out here from Texas and dirtbagging.”

For weeks after their first meeting, Bronson would see Grant around and ask him how things were going. “A lot of people come through like a gap year. They dirtbag around for a season or two, and you’ll never see them again. But Grant struck me as someone who I was gonna see around for a long time.”

At summer 2024’s end, Grant drove home to Frisco even hungrier for more time in Yosemite. He returned to high school for his senior year and applied for spring 2025 Valley jobs, landing a dishwashing job at the Lodge with Aramark, Yosemite’s concessionaire. As planned, Grant graduated from high school in December, and after turning 18 in May, left again for Valley life—this time, with his parents’ approval.

On the way, Grant stopped off for a few days at Red Rocks outside Las Vegas, but it just wasn’t the Valley. His mother got a phone call on his final night there. “He was crying and said he was feeling homesick for the first time,” says Jennifer. “He just wanted to get to Yosemite, so he could make a home and meet new friends, and be with people that he was invested in.” Grant told his parents that he was going to drive through the night. Jeff stayed on the phone with him all night until he got to Yosemite to make sure he didn’t fall asleep at the wheel.

III. Frisco

From a young age, Grant’s family visited National Parks and watched Grant run off and disappear down trails. “Ever since he was little, we’d be on a hike somewhere and he would take off a mile ahead of us,” explains Jeff. “And we’d eventually find him on top of a rock. We were never the family to go to malls or movies.”

Grant discovered rock climbing inside the Frisco, Texas, Canyons Rock Climbing gym when he was 14 years old. From then on, climbing was his full focus. “He was already the kind of kid who would climb out of his window and sit on the roof at night,” his father said. “But once he found rock climbing, that was it. And then his focus was Yosemite.”

Grant started working at Canyons his freshman year of high school and used the money to buy outdoor climbing gear. He became obsessed with Yosemite movies like Valley Uprising and Free Solo, and regularly made his family watch them. “It was important to him that we tried to learn about it,” his older sister Anna recalled. “We all watched Free Solo with him a bunch of times. He would dress up as different climbers for Halloween, and he wanted to make sure we all knew who he was.”

“Alex Honnold was probably his biggest hero on the planet,” his mom told me. “He watched every one of his movies over and over again.”

IV. Boystown

In May 2025, Grant arrived in Yosemite Valley after his marathon night of driving from Red Rocks. He checked in with housing and secured a tent cabin in Boystown. There, he met his short-lived and well-loved Boystown family.

In July, only two months later, I sat in the Boystown kitchen and interviewed his friends and neighbors. They included his roommate Kelvin Pittman, climbing partner Chris Guzman, neighbor Emily Wolk, and instant crush Audrey Balint. Loud kitchen sounds—fans from the commercial refrigerators, constant microwave door slamming, etc—threatened to drown out my recorded audio.

“Everyone he met liked him, and everyone he knew loved him,” Audrey Balint tells me while drumming her fingers on Boystown’s sticky Formica kitchen table. She was showing me a journal they’d made in Grant’s honor. His friends keep it sealed in plastic Tupperware. “He was confident, and amazing. There were no vibes between us at all, and within four days of knowing me, he asked me on a date. I said, ‘No, I’m not going on a date with you. You’re 18 years old!’ He said, ‘Well, I just couldn’t live with myself if I never asked.” After that, Audrey and Grant became buds.

“He was a very good conversationalist,” says Emily Wolk. “He was curious about everything and would focus on anyone who was talking. Which was so impressive for an 18-year-old.” She then added: “He was also very sweet and safe.”

Chris Guzman told me about climbing Grant’s Crack (5.9) and the Aid Route (5.11b) on Swan Slab with Grant. They’d also spent a day in Tuolumne, climbing Little Sheeba (5.10a) on Lamb Dome, and The Dike Route (5.9 R) on Pywiack Dome. “Both of us were shitting bricks the whole time, but it was so fun,” he says.

According to Kelvin, Grant was never on his phone. “This kid just wanted to get to know people and be present,” he says. “And he wanted to learn. Any time someone started talking, he was a sponge who wanted to know everything.”

In the Boystown kitchen, Grant would make a large batch of spaghetti for the week, store it in a Tupperware container, and then forget to put oil in it. So, when he’d pull it out later, it would always be in one big, congealed square. He was always eating spaghetti in squares.

I ask the group if anyone had ever spoken to him about his free soloing. There’s a silence. It’s Audrey who speaks up first.

“I talked to him about it,” she says. “He deeply enjoyed the feeling of having his own life in his hands. Every movement, every step, every breath was a choice to keep moving. He compared it to a character in the John Green book The Fault in Our Stars who put an unlit cigarette to his lips and said, ‘I never light it. I never give it the power to kill me.’ He saw soloing as his way of going out and taking his life incredibly seriously. And being purposeful about choosing to keep living. He took it very seriously.”

Chris worried about it and had asked him to stop. He didn’t think Grant had had enough time in the Valley to realize how dangerous it really is. “Had he listened to me or spent enough time here to realize that anything can happen to any good climber, I think that would have deterred him,” he says.

“We both asked him to stop,” Audrey adds. “He wasn’t stupid.”

V. Camp 4

In May, Grant climbed After Six (5.7), a popular five-pitch route for Yosemite beginners, with a rope and partner. Then he started free soloing it regularly. Then he started free soloing it barefoot.

This wasn’t news to his friends. According to Maison from the El Portal Market, Grant would free solo—even onsight free solo—many Valley moderates, including After Six, Swan Slab Gully (5.6), Jamcrack (5.9), Braille Book (5.8), and Ranger Crack (5.8). “It’s all gnarly to me, but downclimbing Ranger Crack sounds so scary,” Maison says.

Grant was open with his parents about his free soloing. “He would get into a routine,” his mom, Jennifer, told me. “And [free soloing] became natural to him. It made him feel so small—and part of something much bigger than him. I would beg him not to do it. Finally, he looked at me and said Mom—and he’s a horrible liar—I can lie to you, or I can tell you the truth. I told him not to lie to me, but he had to text me when he came down.”

Earlier this spring, Bronson was heading out of Camp 4 to go free solo Swan Slab Gully (5.6) with a friend of his, and Grant wanted to come along. Bronson was worried about Grant’s experience with soloing. “I said, ‘Wait, you’ve done this right? Don’t come climbing if you haven’t done this,’” Bronson remembers.

Grant told Bronson “Yes,” and that he’d free soloed it earlier that day, even. On the climb, Grant talked to Bronson about how often he’d been free soloing. “It seemed like he really liked the free soloing component of it,” says Bronson. “He wasn’t doing it because he couldn’t find partners.”

A few days later, Bronson saw Grant at Climber Coffee in Camp 4. It would be their last interaction. Bronson introduced him around. “I said, ‘Hey, this is Grant. He just graduated high school, and he moved to the Valley. How cool is that?’” While bouldering around Camp 4 later, Grant started talking about free soloing again. This time, he said he’d been free soloing a lot. “So, I had a little heart-to-heart with him,” says Bronson.

He passed down a story that Ron Kauk had told him years ago. “Kauk told me that [Jim] Bridwell told him that with free soloing, there’s so much to lose and so little to gain. And I’ve always remembered that. Bridwell told Kauk, Kauk told me, and I told Grant. It felt appropriate. Free soloing shouldn’t be glorified, and it isn’t necessary.”

Bronson also told Grant to buy some Micro Traxions and go to the Cookie Cliff. “There’s plenty of fixed lines around the Valley.” Bronson left the Valley shortly after. A couple of weeks later, he passed through Tuolumne and heard from his friends that Grant had fallen off Royal Arches.

His first reaction was to curse and shake his head. But he later insisted that Grant wasn’t soloing with an ego. “He felt more like a lone wolf,” says Bronson. “Social for sure, but he had his own relationship with climbing. He never bragged about any of his free soloing. I’ve been in situations now, a few times, where things have gone bad and I’ve had to say to myself, whoa, that was a close call. And those moments all changed how I assessed risk moving forward. But how do you assess risk when you’re young and haven’t had any—or enough—of those moments?”

In the video below, the author explains what it was like to work on this story and how he related to Grant through his own experience as a young man in Boystown.

VI. “Scrambling” culture

After locating Grant’s body, YOSAR Program Manager Jesse McGahey connected with Grant’s dad, Jeff. “Jesse called Grant’s accident a mistake,” Jeff tells me, “And I understood that. And I understand his perspective to protect other climbers and the community, but I think of it as an accident and a mistake. Grant had planned this. And for whatever reason, something happened.”

When YOSAR returned Grant’s phone to his family, the climbing app Mountain Project was still open to the Royal Arches page. Grant also had a number of photos of the route and 3D maps running, including onX Maps set to the Central Royal Arches area. Also, Spotify was open. He had been listening to the “How to Train Your Dragon” soundtrack.

His approach shoes were on, indicating that he had likely fallen on what he considered scrambling terrain. About 200 to 400 feet above where his body was located, there is a third-class ledge system that quickly cuts off into 5.10+ territory, off route from the Royal Arches climb. It’s beautiful there; Royal Arch Cascade flows not far to the west and trickles down and across the Valley Loop Trail as it winds its way towards Mirror Lake. A cairn made of granitic rocks marks the first pitch of Royal Arches under a Californian black oak tree that reaches high and wide toward the wall.

YOSAR found Grant’s body using the Find My Friends App—the same app his family used when they discovered he’d run away to Yosemite the year before. It was the first time they’d used it in a rescue, and it saved them a day of searching. Without GPS technology, they would have had to search the route pitch by pitch, canvas the base, the North Dome Gully descent, and likely dispatch the Park’s only helicopter.

Jesse wasn’t able to comment on the specifics of Grant’s accident, but he connected with me about Yosemite’s free solo culture, particularly in the post-Free Solo era. “The Park has seen many free solo accidents before and after the Free Solo movie,” he told me. “Climbing unroped is the second leading cause of death for climbers in Yosemite. There’s definitely a culture of free soloing in Yosemite, and that’s been here since I got here… and probably since the seventies.”

When I think back on just about every Valley climber I know—the ones who return every season and make Yosemite climbing a large part of their lives—every one of them has soloed something at one point: even Jesse, even me.

“So many of us here have been a part of this Yosemite culture,” Jesse says. “I’ve climbed Cathedral Peak [unroped] countless times, and I feel so locked in. But I have to reconsider soloing it now because there’s a lot to lose and little to gain. And if you’re a leader in the community or someone that people see as a model for safety, you just can’t do that. What am I saying? Do as I say and not as I do?”

When I think of free soloing in the Valley community, I don’t think of big gnarly projects, like the ones Alex Honnold does. I think of the simple Yosemite classics that my friends do: Cathedral Peak, Matthes Crest, After Six, Nutcracker… Royal Arches.

When you’re in Yosemite, it’s easy to get caught up in the crowd and culture of the Valley—to trust your experience, muscle memory, and heart. “I got this,” is a mantra that I’ve found myself saying in my head so many times throughout my climbing career. It’s a powerful credo to be used when out on the sharp end—when it’s time to trust your feet and gear. But it’s not just about you when you’re free soloing. You may have it, but what about the unknown variables—the rock, weather, vegetation, or animals. What about your family?

“People regularly refer to free soloing Cathedral Peak and Tenaya Peak as a scramble,” Jesse tells me. “They don’t even use the term, ‘free solo.’ ‘Oh, I did some scrambling in Tuolumne.’ What did you do? ‘NW Books, Matthes, Cathedral….’ Well, those are rock climbs. It’s just so common here for climbers to tone down the nature of their activities. To make it seem more approachable and less risky.”

If Jesse has been reevaluating free soloing lately, it makes sense. It’s his job to be the first responder when things go wrong. He recently lost a good friend and NPS employee to a free soloing accident, and Grant’s SAR impacted him. Of course it did.

“[Grant] sounded like a really cool kid. Seeing the anguish of his family, and what they’re going through, is unforgettable,” Jesse says. “I’m a parent and you’re a parent. I was just reading Harry Potter with my kids, and Dumbledore tells Harry at some point near the end that death is not about yourself, it’s about who you leave behind. [‘Do not pity the dead, Harry, pity the living.’] When you’re making that gamble, you’re gambling on your family and friends.”

Free soloing will continue. But I’m not sure that it’s fair to simply write all free soloists off as reckless. It’s their lives, after all. And if you love someone, you’re supposed to love everything about them. Those who connect to Yosemite are hardwired to enjoy the freedom of movement, purity, and rhythm that free soloing its formations allows.

There is no certainty in the Valley. And any argument for or against absolute climbing rules will swing back and forth, like the pendulum on pitch 9 of Royal Arches.

VII. A passion so deep…

When writing this piece, there was a moment when I was sitting in my garage office, hesitating to push the call button that would connect me to Grant’s family. I’ve done interviews like this before, but this time the incident was much more recent. I briefly thought about the call that YOSAR made to Grant’s parents the night they found him, and its impossible message.

I pushed the call button and his father picked up with a friendly voice and put me on speaker so his mother could join. They were open and candid and wanted to talk about Grant. His biggest dream was to be featured in Climbing Magazine. “His dream is coming true,” his mother said. “But not the way I wanted it to.”

After the news about Grant got out, a friend of theirs started a GoFundMe. “We’re not a wealthy family,” his mom said. “But we certainly don’t need the kind of money that it brought in. So we wanted to do something better with it. We got Jesse to get us the information for Friends of Yosemite Search and Rescue, and we added it to the GoFundMe page. So far, we’ve donated about $3,000, but we’ll make another donation soon.”

The Clines did use a portion of the funds to fly out to Yosemite. They hadn’t been there before, but they immediately felt Grant’s energy there. “It’s so wild and beautiful,” his mom said.

On the phone, his sister, Anna, agreed. “It was incredible,” she said. “It brought everyone a lot of peace. It was just easier to appreciate why he was there because it was so beautiful. Maybe it helped with a little bit of acceptance. Maybe it was a little easier to understand what he was doing.”

Grant’s dad admits that his family is still picking up the pieces, and that he imagines they always will be. However, they’re heading back to Yosemite in August, and plan to return again next year.

“Grant felt a big calling to Yosemite,” his mom said. “I think he’d been there before, and he’ll be back again.”

On the day Grant’s oldest sister, Sydney, learned of his passing, she turned to her journal and wrote, “I think that’s the beauty of human nature—when a passion runs so deep that logic and reason fall away, and fear can no longer touch the body or the mind.”

A previous version of this story incorrectly stated that Grant’s body was found about half a mile east of the first pitch of Royal Arches. His body was found about 800-1,000 feet east of the first pitch, under the Cobra feature.

The post The Valley Boy: How a Free Soloist Met His Untimely End in Yosemite appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

El Cap’s upside-down flag, the park’s fired lone locksmith, and the safety of Yosemite climbing this season

The post How the Yosemite Climbing Community Is Reacting to DOGE Layoffs (Updated) appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

March 17, 2025 Update: Yosemite Search and Rescue (YOSAR) has announced that they will be fully staffed for the 2025 season. “This week, the National Park Service was given the go ahead to hire additional staffing (AD-Administratively Determined) for public safety, incident, and emergency response,” wrote Yosemite Climbing Ranger Emeritus and YOSAR Emergency Services Program Manager Jesse McGahey in a statement released March 14. This includes full staffing levels for the SAR Site, which is critical for technical climber rescue calls.

Nate Vince, the suddenly famous Yosemite locksmith who lost his job as a result of the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE)’s recent slew of layoffs, texted me while hanging off the side of El Capitan on Saturday afternoon: “Yeah, Buddy, we’re up here! The teamwork to get this done was unreal.”

I reached out to Vince as a friend of a friend from my own days working for the Yosemite Bear Team and as a white carded EMT during the 2011-2012 seasons. With many other seasons working for the Mountaineering School and High Sierra Camps—as well as dirtbagging and climbing with members of the SAR Site—I felt hit hard by the news of the cuts to Yosemite Search and Rescue (YOSAR) and other park staff. To get to the bottom of how DOGE’s actions were impacting my favorite community, I reached out to Vince and others to find out how they were reacting.

The upside-down flag on Yosemite

On Saturday, February 22, Vince and a crew of six friends and ex-coworkers—all current or past National Park Service (NPS) employees—hauled a 30×50-foot American flag up El Capitan’s East Ledges and unfurled it down the headwall between Zodiac (16 pitches, Grade VI, C3) and Horsetail Fall (also known, this time of year, as the Yosemite Firefall).

The flag was donated by a current NPS employee (and veteran), and the crew took care to respect it. Hauling and rigging the flag wasn’t easy. The wind was whipping up the face and causing the flag to behave like a giant sail. “None of us had ever climbed El Cap with a 50-foot flag before, so it was all new,” Vince told me once he was down. “In the interest of safety, we pulled it back up and spent a couple of hours on top, waiting for the wind to die down before trying again. It wouldn’t have been worth it if anyone got hurt.”

The flag-hauling climbers released the following statement to various news outlets on Saturday afternoon:

“The American flag is a symbol of unity, pride, and honor. The flag represents the ideals, values, history, and people of our nation, and we recognize and understand the importance of treating the flag with respect and dignity. The upside-down flag is used as a signal of dire distress in instances of extreme danger to life or property.

The purpose of this exercise of free speech is to disrupt without violence and draw attention to the fact that public lands in the United States are under attack. The Department of the Interior issued a series of secretarial orders that position drilling and mining interests as the favored uses of America’s public lands and threaten to scrap existing land protections and conservation measures. Firing 1,000s of staff regardless of position or performance across the nation is the first step in destabilizing the protections in place for these great places.”

After a couple hours, Vince and his crew carefully raised the flag, folded it correctly, and packed it into their haul bags for the hike down. They could’ve left it up. It would’ve been tough for anyone else to retrieve it. But they’ve worked for the National Park Service, and visitor experience was on their minds. “We wanted to give people a chance to get their firefall pictures without the flag. It was a beautiful evening for it,” Vince explains.

How the DOGE layoffs hit Yosemite

If you haven’t heard the full story, Vince, aka Yosemite’s only locksmith, got fired on Valentine’s Day—exactly three weeks shy of completing his one-year probationary period. He was great at what he did, receiving numerous awards and glowing evaluations. “Then on Valentine’s Day, I got this generic email with my name pasted into it,” Vince says. “It said I didn’t fulfill the knowledge, skills, or abilities for my job. Now Yosemite has no locksmith.”

View this post on Instagram

You might not know it, but Yosemite has over 1,000 structures that use a lock-and-key system, including many historic buildings, archives, and housing. So by stating that they no longer need his position, the government is essentially saying they don’t need locked doors in the park.

While working as a seasonal mechanic during the last government shutdown, Vince witnessed what happened to Park structures when they were understaffed: “Historic structures got broken and damaged—and these are important places. They’re part of what makes America cool. And when they aren’t protected, people go to Joshua Tree and cut Joshua trees down, or they go to the Ahwahnee and steal hotel signs. And what’s worse? What happens if there’s a rescue situation and YOSAR can’t get into the SAR Cache? You can’t break that door down. The rescue ain’t happening, and lives are in peril.”

Of course, the layoffs aren’t only happening in Yosemite. Alex Wild—a former Yosemite wilderness ranger who climbed The Nose with Vince last fall—was dismissed from his job as an interpretive ranger and the only EMT at Devils Postpile National Monument. He got the email on February 15. “My immediate boss advocated for me, telling people, ‘Hey, don’t fire this guy; he’s our only EMT,’” Wild says. “But that’s how sloppy it all is. Maybe they didn’t mean to fire their only EMT, but they did.”

Devils Postpile averaged one or two rescues per week the previous season. “Just about every Saturday,” Wild says of their typical rescue cadence. “People get hurt here, but it’s nothing like Yosemite.”

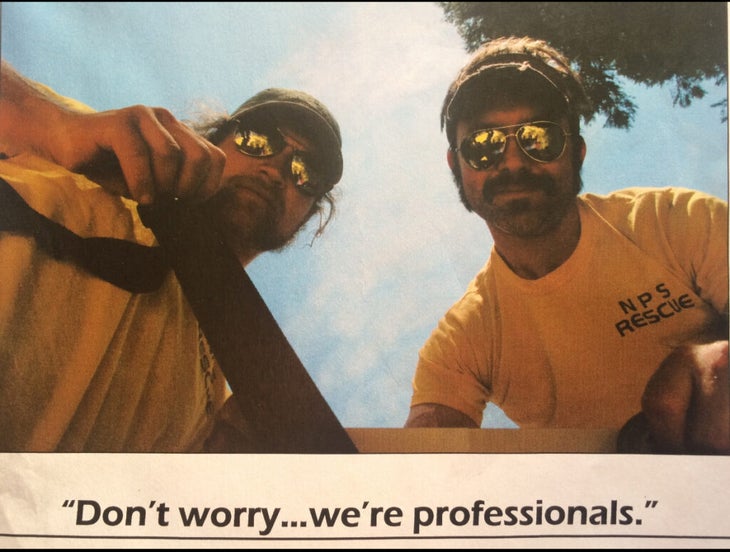

In Yosemite, YOSAR handles 911 calls for high-angle injuries, water rescues, and just about any other issue that occurs off pavement. Highly trained permanent and seasonal rangers staff YOSAR. But a specialized group known as “SAR Siters” have been part of YOSAR since the `60s, when the Park Service realized that the surging popularity of rock climbing called for expert climbers to assist with high-angle recoveries.

SAR Siters get paid as “AD hires,” which basically means as needed. They get called out for emergencies and are paid by the hour. On February 14, YOSAR sent out an email to all returning SAR Siters announcing a hiring freeze. “We will not be able to hire emergency SAR personnel for the summer season,” the email stated.

In 2024, YOSAR responded to roughly 250 rescues—a typical incident volume that steadily rises year after year. SAR Siters take the lead in nearly every rescue. Not only is confidence on the sharp end of Yosemite’s most difficult routes a prerequisite for being a SAR Siter, but so is being an EMT, Swiftwater certified, highly skilled at rigging, and proficient in short hauling. SAR Siters must also know how to work with Yosemite rescue chopper 551. These are not activities that a recently hired seasonal ranger would just be able to pick up.

If DOGE believes that leaving our national parks unlocked, unprotected, and unsafe is the smartest way to balance our nation’s books, then perhaps the interns crunching the numbers need to go back to school.

Or maybe there’s something else going on. As of last year, national parks constituted less than .05% of the federal budget. And for seasonal rangers, only a tiny sliver of that is congressionally allocated. Climbing rangers, for instance, are funded by grants alone.

“People are making huge sacrifices to live this life,” former Yosemite climbing ranger Eric Lynch says. “It’s not like seasonal or AD hires have any ability to cheat the system. Rangers were repeatedly and consistently abused by the system as it was.”

What do the YOSAR cuts mean for climbers?

Without a full SAR team in Yosemite this year, the climbing community is already contemplating the impacts on the upcoming climbing season.

“In Yosemite, I think the biggest thing is to be prepared to help your fellow climbers,” Lynch says. “The likelihood of being out climbing and running into an issue that you then have to step in and assist with is going to increase substantially.”

“Expect to self-rescue,” Wild adds. “There is so much uncertainty about the SAR teams and personnel that climbers need to go into this assuming that an EMS response either won’t be there or will be severely delayed.”

There will still be rangers in Yosemite working for YOSAR. But the search and rescue team and its resources will be more limited. Two rangers can’t carry a tourist with a broken ankle down the Upper Falls trail, for instance—let alone rig a short-haul mission off of Half Dome.

Will there really not be any SAR Siters this season?

“No,” an anonymous source in Yosemite EMS tells me. “This community is too strong. People are committed to the team and providing that role to the Park. But it will be barebones.”

Right now, the Yosemite community is figuring out how to take care of people. It makes sense that the climbing community is figuring out how to keep climbers and tourists safe, even without government support, because that’s what a community does.

“It’s the community that exists in Yosemite that makes people want to work here,” Lynch says. He knows that visitors value the community of Yosemite, too—it’s part of the experience in the Valley. But he cautions that they will be impacted by the cuts to YOSAR and park staff: “It’s a trickle-down effect, and they’re going to feel it.”

As for Wild, he may pivot to guiding for the season. While he’s less concerned about his own professional prospects, he is quite worried about the absence of rangers in the park. “Someone needs to have that job,” he says. “It needs to exist … How do you get rid of so many of us without any real plan?”

I contacted the Trump administration via email to pose Wild’s very question and didn’t receive a response by the time of publication. I also phoned the public information office for Yosemite National Park. As I poked my way through the phone tree, the assistant to the superintendent happened to be one of the options. The phone rang until an automated voice picked up and said, “We’re sorry, this position is currently vacant. This voicemail box will not be monitored. So please do not leave a message.”

An update from YOSAR

After publishing this article, I heard back from a longtime, respected Yosemite law enforcement ranger, who I had originally reached out to as a source. He works closely with YOSAR and Yosemite EMS—I knew him during my time in Yosemite—and he spoke with me anonymously.

This anonymous source wants the public to know that YOSAR is currently well-equipped with experienced permanent and seasonal law enforcement rangers, paramedics, climbing rangers, EMTs, and wilderness rangers. He strongly believes that Yosemite is still prepared to respond to search and rescue emergencies, even with the recent layoffs and AD hiring freeze. According to this anonymous source, the experience of YOSAR’s permanent law enforcement, wilderness, and EMS staff in rigging, high-angle rescues, helicopter rescues, and leadership is unmatched.

While the SAR Siters are instrumental in rounding out the YOSAR team, this YOSAR leader is confident that they will step up to the challenge until they can welcome all SAR Siters back—hopefully, in time for the summer season.

What can climbers of Yosemite and beyond do next?

When visiting public lands this season—and until appropriate staffing levels at our public lands are restored—please tread even more lightly than usual. Pack out what you can and practice preventative search and rescue measures. And whether you’re climbing in Yosemite, Joshua Tree, the Black Canyon, Zion, or any other national park, be prepared to help others out, too.

If you’d like to weigh in with your insights or experiences at Yosemite, you can contact representative Tom McClintock, who presides over California’s 5th Congressional District where Yosemite is located. You can also reach out to your local representatives to advocate for public lands in your home state. Yosemite is far from the only park affected.

The post How the Yosemite Climbing Community Is Reacting to DOGE Layoffs (Updated) appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

The life and legacy of Niels Tietze

The post When Yosemite Search and Rescue Loses One of its Own, the Rescue Work Goes on for Years appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

At pitch 23, high up on The Nose (VI 5.9 C2; 3,000 feet), Yosemite Search and Rescue (YOSAR) member Scott Deputy put in a piece and sat back in his harness. He admitted to me later that he was bonking. And that if he’d allowed himself more to eat or drink that morning, he surely would have made a better decision. But Scott was in a hurry. He was attempting to rope solo The Nose in a day—or the NIAD as it’s known in the climbing community. This feat is a classic Yosemite test piece that almost every YOSAR member attempts at some point during their season, usually with another YOSAR member as a partner.

Scott was going for it alone, and making good time. It had only taken him 13 hours to get up 23 pitches. But then, just below the ramp to Camp 5, he sat back on his yellow Alien, and it ripped.

“I was in an awkward position, and I kind of fell through my loops,” Scott remembers. His ladder flipped him, and he fell, inverted, down the face of El Capitan. He furiously smacked at his Grigri in an attempt to catch his fall, but its release lever was tangled in his rope system. As he picked up speed, the rope uncoiled, burning through his pants and palms. Scott kept smacking, and right before he got to the end of his line, his Grigri caught his fall—which was a good thing, because in the interest of speed, Scott hadn’t tied a knot at the end of his rope.

Scott found himself swinging, bruised, and bloody, 2,000 feet up in the air. He remembers the shock of still being alive—and wanting to be on the ground. “But at that point,” he told me, “The quickest way down was up.”

Scott’s massive fall was spotted in the meadow by Tom Evans, a photographer and the creator of the El Cap Report, who’d had his camera set up on El Cap Bridge. Tom texted the SAR Site immediately after.

It was October 6, 2012, and I was one of the SAR Site’s resident dirtbags at the time. The SAR Site is a tiny village of tent cabins nestled between the boulders and pines in the back of Camp 4. In appearance, they’re not at all unlike the tent cabins around Curry Village—stretched white canvas over collapsible wood beams, wire beds, and little wood decks—but culturally, they reside in a different park entirely.

“SAR Siters” earn the privilege of living at the site by being medically trained and climbing harder than any personnel in the park. They must be willing to go up anywhere, at any time. They’re rope guns for rangers—an insurance policy to ensure that anyone in need can be reached on any park wall, ledge, or spire at any time. They do the backbreaking work of litter carry-outs for the injured—and for those not as lucky.

As volunteers, SAR Siters only get paid when beeped, so they carry around little archaic devices called “pagers.” Much of their time is time off, which is the real reason why they’re there. Time off to a SAR Siter is usually spent breaking speed records on El Cap or linking Yosemite’s longest routes in a push.

Traditionally, they’re an eclectic group. They carry with them the energy, spirit, and history of past SAR Siters like Werner Braun, Jim Bridwell, Beverly Johnson, John Long, and John Bachar. And for the climbing community, SAR Siters are the soul of Yosemite.

In 2012, the SAR Site had two guest camp spots right next to Scott Deputy’s tent cabin. Having recently finished my season with the Yosemite Wildlife’s Bear Team, I had pitched a tent in one of them. With climbing routes to tick off, I wasn’t quite ready to leave the Valley yet.

A few minutes after 4 a.m., I woke to the muffled clanging of somebody attempting to quietly make food. Scott’s lonely breakfast is familiar to the solo climbers of the world: Breaking bread alone in the pre-dawn hours prior to a self-imposed sufferfest.

Later that evening, after his fall, Scott jugged back up to his high point and continued his climb. Two pitches from the top, he realized he was still on track to make the solo NIAD. It was a feat that maybe 20 people had accomplished at the time. He pulled it off.

But that’s not what this story is about. It’s about the guy who was waiting up there for him.

**

His name was Niels Tietze (rhymes with “pizza”). After Tom Evans had reported to the SAR Site that Scott had taken a bad fall, SAR Siter Niels Tietze and I split off for El Cap Meadow to have a look. Scott looked slow, but fine.

Niels left to gather some supplies for Scott when he topped out. Later that evening, he crept up behind me at the campfire and tapped me on the shoulder. “I’m gonna go fetch him,” he said quietly, never one to attract attention to himself when it came to these matters.

“I’ll go with you,” I replied.

“Not a good idea. I’m moving fast,” he said. He was right. Very few people in this world could keep up with Niels in any facet, but certainly not when he was moving uphill. Hiking to the top of El Capitan—via East Ledges—included fourth and fifth class terrain and jugging multiple fixed lines of unknown origin (though Niels always knew their condition). He disappeared behind the campfire shadows.

Scott topped out and touched the tree. Then he heard laughing, “It was a laugh mixed with relief and joy,” Scott later told me. “It was Niels.”

After making sure Scott was okay, Niels passed over some curry that Scott’s girlfriend had made and homemade bread that he’d baked himself. Then Niels tossed him into one of his ratty old sleeping bags to rest. “He carried all my gear away and said he’d see me later. I guess he had somewhere to be. But that was so Niels. He didn’t just bring me crap from the Village Store. He brought me food made by the people who loved me.”

**

I’d met Niels earlier that year. He was the final SAR Siter of eight to arrive for the 2012 season, his second on YOSAR. He’d ridden his motorcycle from Salt Lake City to Yosemite with his haul bag strapped to the back, showing up at Camp 4 a week overdue.

Things had been lazy for me. I had only arrived a few weeks prior and was getting ready for my High Sierra season to begin. I’d spent my days ticking off Valley moderates, bouldering, and getting acquainted with the new crop of Valley monkeys. I thought I’d met all the SAR Siters until Niels rode in.

“Who’s that?” I nodded over towards Niels as he rolled into camp. Niels popped his helmet off, and brown curls fell onto his face. He had sideburns that crawled past his ears and disappeared underneath a dirty bandana he’d tied over a tremendous grin. He was 25 years old then.

“That’s Niels, the famous missing SAR Siter,” somebody replied. I still consider it the best description of him.

Niels pulled a bottle out of his haul bag that first night in camp, and we all celebrated his arrival. He had bizarre stories stuffed inside the alcohol-soaked bandana around his neck. I kept maneuvering myself around him, so I could listen and take note of what the man was saying.

I learned that Niels had recently found his older brother, Kyle, dead in his family’s Salt Lake City home. He had entered Kyle’s room to wake him up, but Kyle had passed in his sleep. The reasons for his passing are still unknown. “We think he may have had an undiagnosed heart issue,” Niels later told me. “It would skip around sometimes.”

As the night progressed, Kyle’s name would continue to slip out randomly in the middle of Niels’s thoughts, like a failing clutch losing its gear. Niels finally crawled up into the boulders behind Camp 4, vomited, and went to sleep. He woke up and went climbing the next morning. I ran into him on his way back from The Moratorium (4 pitches, 5.11d).

“Hey!” I said, “It was great to meet you last night.” Niels smiled awkwardly and laughed. He had no idea who I was. We forged a friendship after that, founded upon books, poetry, and the mountains.

**

Later that season, I was working up in the Yosemite High Country when I heard Niels’s other brother had died. I had been returning a call to a climbing partner in Camp 4 on a tall rock that we called the phone booth.

“Niels’s brother died? Yeah, I know,” I’d said. “No,” my partner urged over the phone. “Not Kyle. His other brother, Eric … just fell in the Tetons.”

On July 12, 2012, Eric Tietze, the oldest of the three Tietze boys, was climbing the Cathedral Traverse in the Grand Tetons with friends when he fell to his death. He was alone when he fell, as he’d moved ahead of his party. His body was located by Grand Teton Search and Rescue the following day.

“When Niels arrived for his first season with YOSAR [2011], he was hurting from his first brother Kyle’s death,” SAR Siter Everett Philips told me. “And when it seemed like he might be able to start moving past it, Eric dies.”

At 25 years old, Niels was in what you might call his prime in Yosemite, positioned to make his mark in the climbing world. When it came to climbing, many considered him the alpha of the SAR Site. That doesn’t make you the best climber in the world, but it’s as good a first step as you can take toward being one of the world’s elite mountaineers.

“Eric was not only a horrible step back personally,” Everett continued, “as a brother and a human being, which of course it was, but it was also a huge step back to becoming the climber he’d wanted to be.”

When it came to climbing, Niels had his horse shot out from under him. Sometimes he’d demonstrate extreme caution. Then suddenly, a switch would flip, and he would feel the need to exercise his right to live by riding his motorcycle at 100 mph or driving the Valley loop backward.

“He was lost and scared,” Everett told me. “Which is not something we associate with Niels.”

A month after Eric’s passing, Niels decided it was important for him to finish his brother’s climb, and Everett wouldn’t let him do it alone. They left the Valley for the Tetons and wouldn’t make it back to the SAR Site for a month.

“The day on the Cathedral Traverse with Niels was a really long, emotional day,” Everett recalls. “Niels was putting on an Olympic demonstration of strength, and I did my best to keep up … he actually went down and found one of his brother’s ice axes and his glasses. Talk about looking for a needle in a haystack. That was the level that Niels was at in terms of his mountain sense. He’d go up there to remember his brother and figure out where his brother probably fell.”

Everett and Niels spent time with Eric’s community in the Tetons, then headed to the Tietze house in Salt Lake City. After a few weeks with Niels’s parents, they returned to the Valley.

“He was this force,” Everett says. “The first thing he did when we got back was jump on The Shield (VI, 5.8 A3; 2,900 feet) and try to solo it without a ledge. And he didn’t bring nearly enough gear to do that,” Everett remembers. “It was another one of those times where he showed what an incredible mountaineer he was to bail from up there.”

The Shield headwall of Yosemite is a vertical, sheer granite desert and may just be the worst spot to bail on El Capitan. Niels spent the night there, without a portaledge, spinning inside of his haul bag with all his gear clipped to the outside. He swung around in the open air, wrestling with ghosts and rope systems unimaginable. The next morning, he began a series of long and difficult rappels, somehow swinging himself back onto the headwall when necessary to clip in.

Everett and SAR Siter Zach Miller met Niels at the bottom and helped him carry his loads back to the Site. In the YOSAR community, helping out another climber is called fetching. The YOSAR fetching tradition goes way back to the days of Royal Robbins and Warren Harding.

Robbins and Harding were bitter enemies, of course, but the first helicopter rescue in Yosemite was actually Robbins retrieving Harding off the south face of Half Dome. It was one of those instances when the climbers were paying attention, but the Park Service was not. Robbins notified the Park Service that Harding and Galen Rowell were on the south face of Half Dome, freezing to death in a winter storm. They got a helicopter and rope together and flew Robbins up there to pluck them off.

And in 2016, when former Yosemite Mountaineering School guide Greg Coit and Everett climbed the Regular Northwest Face of Half Dome, Everett strictly instructed Greg: “If we get into trouble, don’t call 911. Call Niels. He’ll be faster.”

Niels was wired that way—as if there was a buzzing wire throughout his body that connected his physical tissues to those in distress. There are so many examples of Niels’s extracurricular Yosemite missions that I’m not sure how he found time for YOSAR duty.

For Niels, fetching a climber in need was instinctual, and fetching a SAR Siter was automatic. During the 2012 season, I remember going to fetch a SAR Siter named Bud Miller, who was soloing the West Face of Leaning Tower (V 5.7 C2; 1,000 feet). Bud was a strong climber and should have bagged it well under the 24-hour mark. But 24 hours were coming up, and no one had seen him. Niels, Scott Deputy, and I drove over to Bridalveil Parking, stopping to grab Bud a breakfast burrito on the way.

We parked and got out of the van and there was Bud, hiking into the parking lot with his middle finger bent up in the air. I thought he was giving us the bird until he got closer.

“I would have finished a lot sooner, but I broke my finger,” Bud said as he threw his gear onto the ground and snatched the burrito from Niels.

On the YOSAR side, Niels was their best. More often than not, if you called 911 hanging off a Yosemite wall between 2010 and 2014, it was Niels’s fuzzy face that popped up at you first from below.