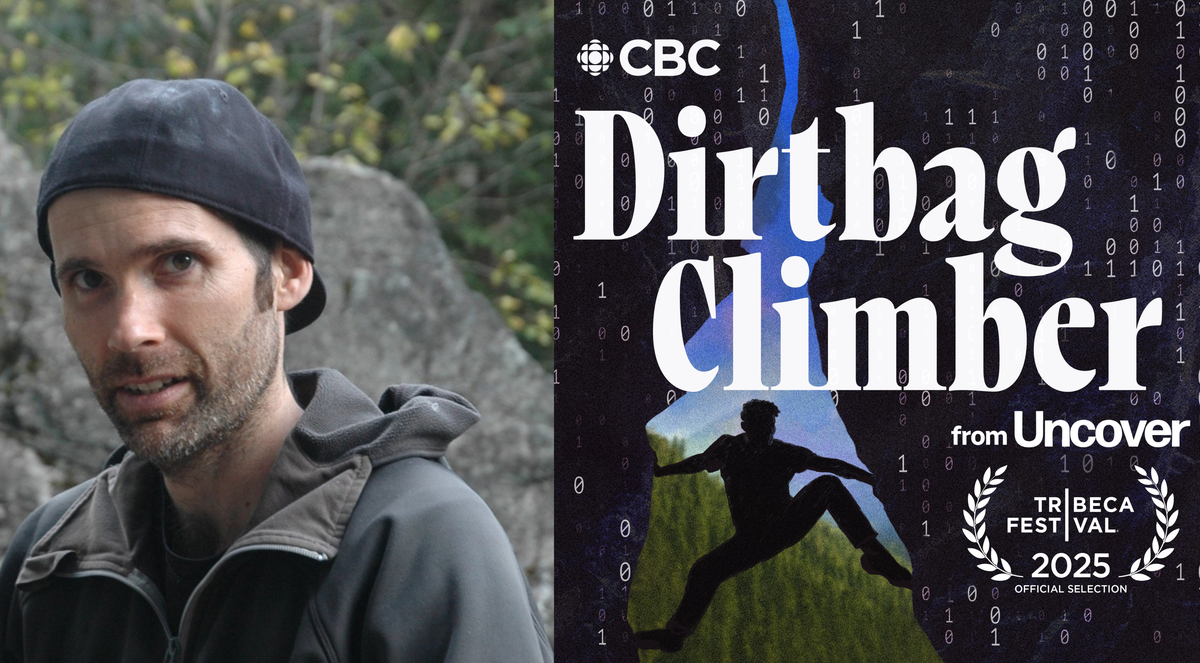

We interviewed the host of 'Dirtbag Climber,' a new podcast that explores the bewildering life and death of a climber who went by Jesse James in his final years.

The post A Squamish Climber Was Murdered in 2017. Now, Another Local Climber Searches for Answers. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Steven Chua had been working as a reporter for the Squamish Chief for only a month or two when he received a press release about a body found at the Cat Lake Recreation Site in Squamish, British Columbia. Chua had just moved to town, and anticipated the “bread and butter” of community reporting: school board meetings and small-town sports. He hadn’t expected to hear about the discovery of a charred SUV at the Cat Lake site on the morning of June 14, 2017, with a local climber known as Jesse James inside—killed by gunshot.

“Things are a lot less sleepy here than I thought,” Chua remembers thinking at the time.

It became clear that “Jesse James” was likely a pseudonym. But the man’s real name—or at least his legal name at the time of his murder—would take another three years to figure out. In 2020, police revealed that they had found that legal name: Davis Wolfgang Hawke. And with the name came a trail of dark, bizarre past lives, heavily publicized for the havoc they wrought.

Davis Wolfgang Hawke, the neo-Nazi

Chua’s reporting on Jesse James eventually led to Dirtbag Climber, a new podcast from CBC’s Uncover series. As the host of Dirtbag Climber, Chua retraces James’s history as Davis Wolfgang Hawke, from his upbringing in Westwood, Massachusetts, to his college years in South Carolina in the late 1990s. At age 20, Hawke caused a stir at Wofford College—and in the national news—for his grassroots organizing as a neo-Nazi. Hawke ran the Knights of Freedom website with a paid membership system, outfitted his dorm room with swastikas and Mein Kampf, and attempted to enact a plan for American history’s largest white nationalism rally.

Dave Bridger, the “Spam King”

Hawke’s movement lost steam, however, when the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Intelligence Report exposed his birth name: Andrew Britt Greenbaum, of Jewish lineage. That revelation turned hate group ire back onto Greenbaum and forced him to shed his neo-Nazi persona. But he immediately found a new one: Dave Bridger, “Spam King.” At the advent of spamming, Hawke-slash-Greenbaum-slash-Bridger’s company, Amazing Internet Products, bombarded millions of Americans with emails to trick a tiny percentage of them into buying junk products, including “herbal penis enlargement pills.”

Jesse James, the Squamish dirtbag

Greenbaum had to abandon this hustle when he was hit with a $12 million dollar lawsuit for buying a list of 90 million email addresses illicitly leaked from inside AOL. He fled internationally to avoid paying it. And then, in 2009, he reemerged “in his final form,” as Chua puts it in Dirtbag Climber: Jesse James, the rock climber and online troll who lived out of his truck. James would become known to the Squamish climbing community for ranting about routes and calling pro climbers “mutants” online. Yet at the crag, he showed a friendly, helpful side to new climbers and old friends.

As Chua works to peel back the layers of each of Jesse James’s past personas in the podcast, he makes one thing clear: James had made plenty of enemies in his 38 years. But Chua’s pondering of who may have murdered James is not the most interesting part of Dirtbag Climber. It’s the discovery of a boy, then a man, driven by the desire for money, authority, and most of all, influence. Dirtbag Climber depicts Jesse James as an early online influencer who toyed with now-prescient subjects a decade before they’d spread all over social media, including white nationalism, tech-savvy scamming, red pilling and the manosphere—even biohacking.

Listen to episode 1 of Dirtbag Climber

Chua caught up with Climbing ahead of the release of Dirtbag Climber’s final episode on podcast platforms on October 6 (though you can listen to all five episodes now on CBC’s Youtube channel). He shares how he used his own experience as a Squamish climber to further crack the story open, and the question that nagged him as he reported on it: How many of us are climbing with a Jesse?

Our interview with Steven Chua of Dirtbag Climber

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Climbing: First off, which name do you choose to call the subject of Dirtbag Climber?

Steven Chua: We’ll just call him Jesse. We’ll keep it simple that way.

Climbing: Take us back to when you first found out about the murder. What were the initial facts?

Chua: The initial picture we got was: this guy called Jesse passed away. There wasn’t anyone who was willing to talk to us about him on the record. We knew by word of mouth that it was 99 percent certain that he was killed, but no one was willing to go on the record and confirm it for us. So we held back on reporting it. The Davis Wolfgang Hawke stuff was still lightyears away at that point. We saw that on his Facebook page, there were a bunch of RIPs. Those were written by people who were on better terms with him. It seemed typical: “It’s a shame this guy got killed.”

Climbing: What impression did you get of him from early conversations with local climbers?

Chua: There were people who thought he was a nice, caring dude. But from all the folks I’ve talked to, it didn’t seem like anyone really knew about his past, aside from the fact that he was evasive about it. As people tried to ask him more about it, he kept on stuffing those questions down. They sort of accepted that.

I haven’t spent a lot of time in other climbing communities, but in Squamish, some people adopt a character in their climbing. You’ll hear about people with larger-than-life names like King Can Al and Heavy Duty. It’s just what people call them and that’s how they’re known around town. You’re just like, “Okay, that’s who they are.” Whether or not they’ll choose to share more personal details, you don’t know. A lot of people just accept it.

Climbing: Once Jesse’s previous name, Davis Wolfgang Hawke, was revealed, what did you set out to learn as a reporter for the Squamish newspaper?

Chua: A lot of the Neo-nazi stuff and the spamming stuff—that was stuff that you didn’t necessarily need local connections to report on. It was out there. So the way that we tried to add our own, different take on that story was to examine those things within the Squamish context. How could someone with this kind of past—as a very controversial, very public figure—adapt to life in Squamish and carve out a life for himself here? What did he do here? That was the different kind of value we could add, because we had that ability to tap into the community and get those bits and pieces that were harder for reporters who were just parachuting in to get.

Climbing: You shared in the podcast that you were able to do that in part because you’re a local climber yourself. Tell me more about your climbing experience in Squamish.

Chua: I started to climb in the later part of 2017. It wasn’t for a story. I was just like, “Man, if I’m going to be here, I’m going to be super miserable if I don’t learn how to do any of the Squamish things.” Because if you don’t do any of the outdoor stuff, the nightlife is nothing, the culture is nothing, really. You’re going to go to the same three bars over and over again and just languish.

I went to the gym, I made some friends, I started to boulder outdoors, and people showed me how to lead sport outdoors. Over time, I would learn how to trad climb and do multi-pitches. Eventually, I became addicted to the sport, and it became my favorite thing to do. And still is.

By 2020, I’d already been climbing for a few years. I had a pretty good working knowledge of the sport, and I’d made friends in the climbing community. Those friends knew people, who knew people. That was what allowed me to connect with one of Jesse’s old climbing partners, and with his romantic partner. And that was what allowed me to get a bit of an edge over other reporters, who didn’t necessarily climb or know much about climbing.

Climbing: As you learned more about each of Jesse’s neo-Nazi, spammer, and online climbing troll personas, what shape was this person taking to you, in terms of his patterns of behavior?

Chua: He was an archetype for a lot of the things that we see right now. He was an archetypical online influencer who managed to gain this pretty sizable following before social media became a thing, just using basic, `90s-style websites. He was an archetypical crypto bro, because he was investing heavily in it before any of us even knew what Bitcoin was. He was an archetypical spam advertising guy who was able to prey upon people’s insecurities long before any of us got high-speed internet. He knew there was a lot of influence in rage. Rage baiting. Controversy.

He’s a patient zero for a lot of these strange and unsettling trends that we’re seeing today. It’s just so interesting that one guy could be so involved in all those things in one go. The team I was working with, we call him the Catch Me If You Can of the dark web. You have this figure who is always on the run from authorities, putting on different personas, milking them for all they’re worth, conning a bunch of people, and throwing it away and doing it all over again.

Climbing: Why do you think Jesse did what he did, in all of his past lives?

Chua: This might just be me projecting or speculating, but the impression that I got is—especially from the stuff that his mother had to say at the time—he was bullied at a certain point in school. I think that even though his dad brushed it off, it left a very big mark on him.

In order to adapt to that, he felt the need to develop this skill of being able to influence people and get certain types of people to bend to his will or to follow him. In order to get himself out of this place of vulnerability, he started to practice that more and more. And in order to keep that influence going, he would adopt whatever persona would allow him to do that best. At first, it would be as this Neo-Nazi leader, and then, it would be as this Spam King. That’s the common thread that you see. Talking to his dad when I was doing the initial few stories, his dad was like, “He just wanted attention and influence.” I wouldn’t be surprised if that were actually true.

Climbing: Some people may see this guy’s high-level descriptors—Neo-Nazi, scammer, online shitposter—whatever you want to call him—and ask: “Why give this literal dirtbag any more attention?” Why did it feel important to you to keep digging and to tell this person’s full story?

Chua: That’s definitely a question I had in my mind for quite some time. It’s a very valid point—why are we continuing to give this person the spotlight? I can understand why people would have concerns about that, because we don’t want to glorify this kind of lifestyle. But at the same time—especially with a case like this, where it so deeply exemplifies all these things happening in our present-day world—I think it’s really important to understand where this all comes from and where it can go. The personal can sometimes have elements of the universal. If we try to understand the course of a person’s life, maybe we can better understand how we can live with all these things that are happening now.

Climbing: Did the process of recapturing this story in a podcast surface new insight for you about Jesse as a climber or as a person?

Chua: It brought conflicting perspectives. His old climbing partner had a very positive view of his experiences with the guy. In his experience, Jesse was maybe a bit of a troll, but generally a good dude and a good person to climb with. Then you hear from someone like Jennifer Archie, the AOL lawyer who was filing suit against him as a spammer, and you see the effect that this guy had, scamming so many people out of so much money.

It made me think of all the times you’re on the sharp end with someone, and you experience these very intimate things that only climbing can really bring out. You can see what a person is like when they’re runout half a pitch up. Their family and friends who don’t climb will never see that kind of fear or focus. But at the same time, you might not know very basic things about them. What’s their real name? It just made me think about: How much can you really know about a person?

Climbing: What’s your best guess as to what happened to Jesse?

Chua: What eventually happened is that his personality and his hubris made him too noisy—it made him a target. That character flaw propelled him to great heights, but eventually got the better of him.

I think if he had just shut up and lived a normal, quiet life, he would have been able to happily climb anonymously well into his old age, and probably just die in a hospital like a normal person. But instead, that one part of his personality just kept on showing up over and over again. And eventually, whether it was through him pissing people off or flashing obscene amounts of cash around town, someone realized that he would be a great target. Whether it was for money, because they were angry, or whatever, we don’t know, but I think that’s what did him in.

Climbing: You describe this as “the biggest story of your life” as a journalist in Dirtbag Climber. What are the life lessons you’re walking away with, from the story of Jesse James?

Chua: The one that probably stays with me is that duality of knowing and not knowing someone. I think the reason why people can get so attached to their climbing partners is because you see a part of them that is basically unknowable in day-to-day life. A climbing partner can give you amazing experiences in such an immediate, visceral way, like when a buddy of mine belayed me for the first time on a trad lead. I’m going to remember that for the rest of my life.

At the same time, maybe you just need someone to hold your rope, and you don’t care who. It made me think of how much you can know about someone you climb with, without really knowing them in the rest of their life. Maybe that’s a good thing, maybe that’s a bad thing. I don’t know. It’s funny in that way.

The post A Squamish Climber Was Murdered in 2017. Now, Another Local Climber Searches for Answers. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

The 23-year-old Alaskan achieved impressive solos of historic routes—with glitter on his cheeks.

The post Bold Young Alpinist Balin Miller Dies in Yosemite appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Balin Miller was fast becoming a legend in the climbing world. The 23-year-old had spent the year of 2025 making a name for himself, with historic solos—and soloing sprees—from Alaska to Patagonia. On October 1, Miller fell to his death from 2,400 feet on Yosemite’s El Capitan. In a horrifying set of circumstances, his death was captured on a stranger’s livestream with some 500 people watching.

Just after midnight on October 2, his mother, Jeanine Girard-Moorman, shared on Facebook, “It is with a heavy heart I have to tell you my incredible son Balin Miller died during a climbing accident today. My heart is shattered in a million pieces.”

Miller had been climbing Sea of Dreams (5.9 A4), one of the most challenging aid routes on El Cap. On September 29, he was photographed by Tom Evans, the creator of the once-daily El Cap Report.

On October 2, Miller reached the top of the last pitch of Sea of Dreams, but his haul bag got stuck on the terrain below. As he descended back down his lead line to free his bag, Miller rappelled off the ends of the rope. Evans described the incident on Facebook and later verified his report with Climbing. No additional information from Yosemite National Park staff or local officials has been released.

The livestreaming of a fall

Eric (who asked that his last name be withheld), a blogger and content producer who calls himself a “Yosemite super fan,” had been livestreaming Miller’s Sea of Dreams ascent online. “I was the sole witness down in El Cap Meadow monitoring Balin when he fell,” Eric told Climbing. He had started livestreaming climbers from the base of El Cap on his Tiktok channel on Sunday.

Using a scope and his phone, Eric had been following El Cap climbers including Miller, who had become known as “Orange Tent Person” among the livestream followers for his orange portaledge. Over the course of the week, some 100,000 people had been participating in the livestream, according to Eric. “Everyone was real interested in him [Miller],” he said.

On October 1, Eric’s livestream followers saw Miller start moving around 10 a.m. as he neared the final pitches of the route. “We were all cheering for him and wanted to see him summit,” he said. When he was almost at the top, around 1 p.m., Miller’s bag became stuck down the pitch. According to Eric, he descended to fix it and rappelled off the ends of his rope. Eric and Evans, who had been photographing climbers nearby, called 911 and a recovery effort was initiated.

Eric said that many of the livestream viewers have reached out to him, and have been having a hard time processing what they saw. “Everybody is shook up,” he said. He shared the video with Yosemite’s law enforcement rangers.

Miller’s bold life in the mountains

Just four months ago, Climbing Senior Editor Anthony Walsh reported on Miller’s historic solo of the Slovak Direct route (M6 WI 6 A2; 9,000ft) on Denali, which Miller said he thought “would be a ton of fun to climb alone.”

This past June, it took Miller three days to complete the ascent—during which, Miller assured us, he got plenty of sleep. With a five-day weather window, the Alaskan soloist opted to take a 19-hour nap at his first glacier bivy on Slovak Direct. He free soloed all but one pitch, which involved A2 cracks (freed at M8).

After Miller’s Slovak Direct solo, alpinist Colin Haley called his achievement “super badass.” Haley added that it was one of the greatest alpine-style solos ever completed in Alaska’s Central Range. And when the news was shared with Slovak Direct veteran Mark Twight, his reaction was simply, “Holy shit.”

Just a few months earlier, Miller had gone on a week-long soloing spree across, improbably, Patagonia and the Canadian Rockies. In January, he climbed Californiana (5.10c; 700m) on Cerro Chaltén, employing a mix of free soloing and rope soloing.

Then, Miller headed to Canada, where he soloed Virtual Reality (WI6), followed by one of Canada’s most infamous climbs: Reality Bath, ominously graded VIII in Canada for its WI5/6 difficulty and objective hazard. He told Walsh that what attracted him to Reality Bath was the route’s “lore,” built up over time by Twight, one of the first ascensionists.

Miller pulled off these three stout solos with a stripe of glitter on each cheek—a habit he’d adopted during a summer of yore involving alt rock, a girl, and partying. “If I was just going cragging, I probably wouldn’t wear glitter,” Miller explained to Walsh last January. “But it’s like a warrior putting makeup on before going into battle … you know you’re about to do something hard.”

When Miller wasn’t climbing, he worked as a crab fisher in Alaska and as a snow shoveler in Montana. Originally from Anchorage, Miller grew up climbing with his father and brother Dylan. He is also survived by a younger sister, Mia.

This is a developing story. We will update it as new information becomes available.

The post Bold Young Alpinist Balin Miller Dies in Yosemite appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

After climbing the 8,163-meter Manaslu, Carlos Soria shares his advice on training, seeking summits, and accepting change.

The post An 86-Year-Old Just Became Oldest to Summit One of the World’s Highest Peaks appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

For Carlos Soria Fontán, Manaslu is an old friend.

Early on the morning of September 26, the 86-year-old Spanish alpinist trudged to the top of the 8,163-meter (26,782-foot) mountain, making history as the oldest person to ever reach the top of a peak over 8,000 meters. He was accompanied by longtime photographer and close friend Luis Miguel López Soriano, and Sherpas Mikel, Nima, and Phurba.

It was a poignant moment for Soria, and not just because of the record. He has a longer relationship with this mountain than perhaps any climber alive today. He first reached Manaslu’s summit in 2010 at 71, but he was also a member of the very first Spanish expeditions to the peak, in 1973 and 1975. But Soria didn’t touch the summit on those trips. The first expedition turned back due to bad weather. On the second, he acted as a designated rope fixer.

Last week, Soria and his team summited Manaslu relatively quickly, and without any major hurdles. After their final acclimatization rotation, they pushed from basecamp to summit in just three days. But on the steep, icy descent to Camp III, the climb took a turn for the worse. Soria’s legs have been a weak point in recent years—he underwent a knee replacement in 2018 and severely broke his leg on Dhaulagiri in 2023. By the time he reached Camp III, he was in severe pain, and his balance and coordination were suffering as a result.

Ultimately, he opted for a helicopter evacuation to basecamp to ensure his injuries didn’t worsen.“If I tried to come down walking, I could cause everyone else problems,” he said. “Carlos wanted to keep himself safe, but also to keep the rest of us safe, everyone else in his team,” his photographer Soriano added.

With Soria’s summit, he broke Yuichi Miura’s world record for oldest person to stand atop one of the planet’s 14 8,000-plus-meter peaks by six years of age. The Japanese alpinist summited Everest at age 80 on May 23, 2013.

“I feel good up there”

Climbing an 8,000-meter peak, in any decade of life, is an impressive feat, but Carlos Soria has now summited a dozen of the world’s 14 highest summits, most of them in his 60s, 70s, and 80s. He is the only person, in fact, to climb 10 8,000-meter peaks after the age of 60.

It begs the question: Why?

At an age when most individuals are bouncing grandkids on their knees—if their knees even function—Soria returns, time and time again, to the most inhospitable regions on Earth, to test himself.

“I do not care about records,” he told me. “I am not looking to be ‘the best.’” He also does not seem particularly concerned with the usual Himalayan mountaineering shenanigans, like sponsorships and motivational speaking tours. In recent years, he has self-financed many of his expeditions. Instead, he is simply drawn to climb. “The mountains are the place I want to be,” he said. “I always want to come back.”

Soria began finding solace in the mountains as a child. He was born in Avilá, Spain in 1939. It was a rather inauspicious year—the last of the Spanish Civil War, and first of brutal dictator Francisco Franco’s 36-year rule. “It was a very difficult time to be in Spain,” he told me. “My family was poor. We didn’t have hot water, we rarely had electricity.”

At age 14, Soria began climbing, exploring the Sierra de Guadarrama range just outside Madrid. “In the mountains, in nature, I found a way to escape that life, to find beauty again,” he said. “That’s why I’ve kept coming back. I felt good there at 14, and I feel good there at 86.”

At 86, maintaining one’s health is an uphill battle. But Soria’s regime is not dissimilar to that of any other climber. He doesn’t touch alcohol or tobacco, and he’s a clean eater. He also spends every morning working out, seven days a week. But the trick, he said, isn’t checking all these boxes. It’s to enjoy the training as much as the climbing. “I really like training,” he told me. “I train when I have expeditions coming, and I train when I don’t. It doesn’t matter.” In recent years, he’s become a fan of indoor rock climbing, too. At 7:00 a.m., almost every day, Soria can be found roped up at a climbing gym near his house.

Everything in the mountains is harder at his age. His mobility, balance, strength, and stamina are all waning. It’s harder for him to catch his breath, harder for him to get food down. His list of old injuries has only grown as the years have gone on. Soria’s approach is to take things slow, and to err on the side of caution. When I asked him what was going through his mind when he took those final steps up to the summit of Manaslu, he answered simply: “I was focused on reaching the summit.”

And what was he thinking when he was finally up there, standing on one of the world’s highest mountains, the oldest person ever to climb an 8,000-meter peak?

“I was thinking about coming down safely,” he said. “I was happy, yes. But I wanted to make sure my team and I got down without problems.”

“If we didn’t change, we wouldn’t be alive”

The only 8,000-meter peaks Soria has yet to summit are Dhaulagiri and Shishapangma, but not for lack of trying. Soria has retreated from Nepal’s Dhaulagiri a staggering 14 times. It’s also where he broke his leg in 2023—though the injury resulted not from his own mistake, but from a Sherpa slipping and falling into him. “Dhaulagiri is not the most difficult, but the weather is unstable, and hard to predict,” he said. “Storms come fast from the valley.” Soria also lost a close friend on the mountain during one of his earliest attempts. Since then, has been extremely cautious in his approach. “I have a lot of respect for that mountain,” he said.

Perhaps no one is better positioned to bemoan the commercialization of high-altitude mountaineering than Carlos Soria. In his early days an alpinist, 8,000-meter peaks represented isolated, remote objectives—true wilderness. Back then, a single team coming together to put a pair of climbers on a summit incited national celebration. Within his lifetime, many of these peaks have become jam-packed thoroughfares. Hundreds of guided climbers may tick a summit in the space of a few days.

“We were totally alone in those times,” Soria said of his trips to Manaslu in the 1970s. “It was very different. We were the only expedition on the mountain. From the gear and apparel we used, to the style in which we approached the mountains, many things have changed today.”

But Soria says he isn’t nostalgic for years past, and he won’t speak ill of mountaineering, then or now. “Things have to change in this world,” he told me. “We cannot worry or be sad. Change is life.”

Many good changes have materialized, too, as Soria sees it. More young people are coming to the mountains, more women, more people of different ethnic backgrounds. “I don’t think the past is better, or worse,” he explained. “I am happy. I like to change with the times. If things didn’t change, if we didn’t change, then we would not be alive.”

In photographs, Soria often wears a wry, knowing smile, as though he harbors some hidden wisdom, some eternal secret, that the rest of us can’t quite seem to figure out. Wondering if I could chip out some of that secret, I asked for his most important piece of advice for anyone who dreams of climbing 8,000-meter peaks. Soria was clear. It’s not training hard or gaining experience. Those things are necessary, but they come later. First, “You have to love it,” he said. “You have to love climbing.”

You can’t be up there for the social media posts or the records or the sponsors. You can’t be up there for the feeling you get when you’re back at home, bragging to your friends at the bar. “If you love it, then you will naturally do it right,” Soria said. “You will train, you will acquire the necessary experience, because you love it. And then, if climbing 8,000 meters is your dream, you can achieve it.”

About the photographer: Luis Miguel López Soriano, who accompanied Soria on his climb, is a Spanish videographer and photographer who has climbed several of the world’s 8,000-meter peaks. Follow along @luis_m_soriano

The post An 86-Year-Old Just Became Oldest to Summit One of the World’s Highest Peaks appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Plus, the forthcoming film that will explore the mindset behind the Slovenian climber’s dominance

The post After Double Gold in Seoul and 10 World Championship Wins, Janja Garnbret Shares What’s Next appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Even from thousands of miles away, one thing was obvious: Janja Garnbret wasn’t there to compete. She was there to win.

In the Lead finals at the International Federation of Sport Climbing (IFSC) World Championships in Seoul, South Korea on September 26, Garnbret strung the route together with rhythm, while rivals were bucked off early. The next day, in the Boulder finals, she solved problems that stalled others, moving with a composure that made the crowd feel incidental.

Two events, two golds, one week. This brings the Slovenian prodigy’s total IFSC World Championship gold count to 10, alongside her 47 IFSC World Cup gold medals, two Olympic gold medals, and many more victories.

“Winning one gold at the World Championships is a dream,” Garnbret told Climbing. “Winning my 10th with two in Seoul feels impossible—but here I am. It’s hard to put the emotions into words. I’m just grateful for everyone who believes in me and helps make this possible. It’s always a battle, and I’m proud I proved to myself I could do it again.”

Garnbret’s performance at the International Federation of Sport Climbing (IFSC) World Championships in Seoul, South Korea last weekend wasn’t surprising—dominance has long been her signature. But this sweep felt less like another victory and more like a statement: the ceiling has moved. And as she recently told Magnus Midtbø, she believes she could compete against men—a remark that lands less like bravado and more like a total possibility.

“I was totally in awe of how amazing Janja is under pressure,” said adventure filmmaker Jon Glassberg of Louder Than Eleven productions, who was behind the camera in Seoul. “When she competes, she is there to win and it feels like second place would be ‘losing’ to her. The pressure she puts on herself is crazy, and the other competitors are always chasing her.”

A double gold at a World Championship is virtually unprecedented—no climber before Garnbret has won both Boulder and Lead golds at the same event. Though Garnbret herself pulled off the same feat at the World Championships in Bern, Switzerland in 2023, and in Japan in 2019. Adam Ondra earned golds in Lead and Boulder in two separate 2014 World Championship events (one in Spain, another a month later in Germany), but Garnbret remains the only one to snag double gold in a single World Championship event.

What really sets her victories apart, however, isn’t the medal count, but the assuredness of the performance: control, adaptation, and endurance across two disciplines, rarely mastered in tandem.

“Throughout the event, I was struck by her ability to perform at the highest level in Lead, winning both semifinals and finals,” Glassberg said, “and then the next day doing it all again in Bouldering despite the physical and mental drain of four rounds in 48 hours.”

Each style, Boulder and Lead, expose weakness and demand skill: one is problem-solving at speed, explosive power under the clock; the other, endurance, pacing, and analysis. Most athletes lean into one discipline and accept vulnerability in the other. That’s one reason why the decision to split up these disciplines at the 2028 Olympic Games was welcomed by many climbers. Yet Garnbret showed no weakness in one discipline over the other.

“Each victory has its own weight. People expect me to win now, and carrying that expectation feels heavier every year,” Garnbret reflected after the 2025 World Championships. “First and foremost, I want to prove to myself that I can do it. I know how much I put into training, and I want to show that work on stage. That’s why every win matters—and why I never take any of them for granted. The fans in Seoul and beyond were incredible, and their support meant everything.”

She switched between styles as if their demands were interchangeable. In Lead, she even recovered from a mid-clip slip on a slick right hold. After her composed save, she became the only finalist to top the route. In the Boulder final, the title hinged on the last bloc: Problem 4. She was the only competitor to top out, sealing the gold with a decisive, power-through finish.

What really struck Glassberg was how she dominated every stage of Lead, then came back less than a day later to deliver again in Boulder, pushing through the physical and mental fatigue of four rounds in two days. “It would break most people,” Glassberg said. “But not her.”

Garnbret also competed against a stacked field. The Seoul lineup included: Oriane Bertone, France’s Boulder prodigy, who placed second in Seoul; American Melina Costanza, who took bronze in Boulder; and Seo Chae-hyun, South Korea’s Lead specialist. That’s what made this double gold more than a medal count: It underscored the gap between a climber who can dominate in a lane and one who can finesse her skill across the sport’s stage.

For women’s competition climbing, Garnbret’s double gold is more than a personal triumph—it’s a marker of where the sport is heading. A decade ago, the idea of one athlete mastering both Boulder and Lead on the same stage was improbable. But after her performance in Seoul, this level of mastery feels like the new bar.

If that’s true, what does it mean? Can athletes still afford to specialize? Will training camps shift toward balance instead of bias? How much adaptability can a single season, or a single athlete, flex into?

What’s all but certain is the ripple effect. To younger climbers, Garnbret’s sweep is proof that all-around mastery is possible. To audiences outside the sport, it offers a glimpse of climbing’s complexity—part puzzle, part marathon—and why it deserves its place on the world stage.

As this comp season comes to a close, Garnbret’s calendar next year points toward more World Cups in the lead up to the 2028 Olympics. But she says she’s also excited to do some outdoor climbing: “I have plenty to look forward to, both in climbing and in life. I’ve started projects on rock that I want to finish in the coming months. Competition-wise, we’ll see how the calendar looks and decide how much to enter next season. Taking fewer comps this year was the right call—I needed to reset, focus on rock, and keep that sense of freedom and joy alive in competition, too.”

Currently, Garnbret is also shooting with Glassberg, who is capturing this chapter of her career with Red Bull Studios. The new feature film about Garnbret will show not just the wins, but the mindset behind them. “It should be a very real and vulnerable look into Janja’s life as a climbing superstar and the greatest to ever do the sport,” he said. The film will likely release sometime during the summer of 2028.

Of course, I’ll be watching, whether she turns up on a movie screen or on the Olympic wall. But what stands out to me is how she resonates with more than just climbing die-hards—non-climbers are rooting for her, too.

On Lead in Seoul, Garnbret’s last move told the whole story. She paused just before the crux, just long enough to breathe, shaking out, reading the wall. Then she launched for the dyno, stuck it, and hurried to clip. A flash of calculation followed by pure instinct. This is the balance that defines her climbing—calm when she can be, decisive when she has to be.

The post After Double Gold in Seoul and 10 World Championship Wins, Janja Garnbret Shares What’s Next appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

We spoke with Haley about his history with Aguja Standhardt, the ethics of hiring a porter, and why he doesn’t value “boldness” in climbing.

The post Days After Cerro Torre, Colin Haley Makes First Winter Solo of Patagonia’s Aguja Standhardt appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Veteran Patagonia climbers know one thing to be true: if the wind isn’t howling, and it’s not nuking snow or rain, you’d better go climbing—it could be months until good weather returns to one of the stormiest places on earth. Colin Haley, arguably the most accomplished Patagonia climber of all time, takes this approach as gospel. And so it was no surprise that after just six days of rest following his first solo-winter ascent of Cerro Torre, the 41-year-old American headed back into the Torre Massif when more good weather rolled in.

This time, Haley was set on the smallest of the three “Torres”: Aguja Standhardt, which he made the first-ever solo of in November 2010 via Exocet (WI5 5.9; 500m). Canadian Marc-André Leclerc made the second solo of Standhardt, and the first free solo, just days after the end of Austral winter, in September 2015, via Exocet’s “sit start” Tomahawk (M7 WI6). Haley says it was the Austrian Tommy Bonapace who initially inspired him to climb Standhardt alone. In April 1994—before forecasts or what we now consider the town of El Chaltén—Bonapace soloed to the top of Exocet’s ice chimney before retreating in a storm. According to the online guide Pataclimb.com, Bonapace “climbed free solo, trailing a 100-meter rope behind him and stopping briefly at belays to smoke a cigarette and haul his pack.”

Haley made an Instagram post summarizing this ascent, where he concluded: “This climb was undoubtedly much easier, and much less special, than my recent climb of Cerro Torre, so it felt a bit anticlimactic.” But though it might pale in comparison to Cerro Torre, Aguja Standhardt remains a truly beautiful mountain, and Exocet one of the most spectacular ice climbs on the planet. As Haley made his return home to Chamonix, I caught up with him via Whatsapp to learn a little more about this ascent.

Our interview with Colin Haley

Climbing: How were the conditions on Exocet? A lot of brittle ice or snowy mixed sections?

Haley: I would say that conditions on the route were pretty good. The amount of ice in the chimney was definitely less than the first time that I climbed Exocet, but I think the chimney was in pretty normal condition for the modern paradigm. The mixed pitches were actually in quite good condition, with very little snow or rime on them. The biggest difficulties in terms of conditions were that the ice in the chimney was certainly much more brittle than in summertime, and I had a lot of deep trail breaking on the glacier.

I actually think that in the entire Chaltén Massif, Exocet is probably the route whose difficulty is the least augmented by climbing in the winter season. For one, it is a route that is typically climbed entirely in crampons (as opposed to rock shoes), and also it is east-facing, so it receives sun in what is otherwise the coldest part of the day. In fact, one of the biggest problems with climbing Exocet now in mid-summer is that during good weather windows the chimney often starts to run with water by mid morning. One doesn’t have to worry about that issue in winter!

Climbing: On Instagram, you wrote: “After my recent climb of Cerro Torre I felt extremely tired and satisfied, and would’ve happily not gone mountain climbing for a while. In Patagonia, however, opportunities for alpine climbing are rare, and one doesn’t get to choose when they arrive.” Can you explain your motivations a bit more here? Obviously you know how rare good weather is, but still—you’d completed a very difficult lifelong dream less than a week ago. Why specifically did you head back out into the mountains? Or, in other words, why did you feel uncomfortable with the idea of “wasting” good weather?

Haley: Well, my motivations to go climb Standhardt were the same as any time I go try a difficult alpine climb, it’s just that in this case it took a bit more effort to overcome the inertia of chilling. This is nothing new to me, or other highly motivated climbers who have been in Chaltén with good weather windows coming in quick succession. A couple of the most epic climbs I’ve done in the Chaltén Massif, the Torres Traverse in a day and the Wave Effect Direct in a day, were done with just a few days of rest in town between.

Climbing: Where did you camp? And how much weight did [your porter] Maxy Abasto carry? Previously you’ve talked about how portering in Patagonia, especially in winter, feels like it takes away a big part of the solo challenge, and that it’s not an attractive strategic option for you. How has your opinion on that changed?

Haley: I slept the first night near the Nunatak, a little ways beyond Niponino, and I slept the second night on the glacier right near the base of Standhardt’s east pillar. On that first day Maxy carried 18 kilograms and I carried only 10 kilograms. The second day of the approach was much shorter, but involved a lot of trail breaking, and I was then carrying everything myself, so it felt just as tiring.

You’re right that in the past I have been purist about not using porters in Chaltén. I never did so before last summer, and I certainly think that in general it will still be more “my style” to not use porters in Chaltén, even if the biggest reason is just that I can’t afford porters. The reason that I twice hired a porter during this trip is because it seemed like it would actually make a real difference for me—the first time I had arrived in the middle of the weather window, and knew that it would be really advantageous to make it all the way to the top of Filo Rosso [near the start of the technical climbing on Cerro Torre’s Ragni Route] in very limited time. The second time I was just really tired still from Cerro Torre, and wasn’t sure if I was up for carrying 28 kilograms by myself all that way, and still have enough energy left for the challenge of the climb.

In addition to those very practical reasons, I also have done a fair amount of pondering on this question, and my purist viewpoint started to seem a bit illogical. The biggest reason for that is that most climbers, including myself, use gear caches in the Chaltén Massif during a climbing season, to reduce the amount of weight being carried back and forth on the long approaches. If Person A has three months to spend in Patagonia, then he or she can do a big load carry just once at the start of the season, and then carry a light pack for the remainder of his or her trip. If Person B has only 3.5 weeks off from work, it doesn’t seem fair to fault him or her for hiring a porter to climb in the same weather window as Person A, since they both end up carrying a light pack into the mountains. Also, if you are about to hike into Niponino to go climbing, and your friend mentions that they have ropes and rack cached there and offers for you to use them, of course you won’t say no. So if another person doesn’t have such luck from a generous friend, it doesn’t make sense to fault him or her for hiring a porter. In the last Patagonian summer, when Tyler Karow and I planned to go try the Southeast Ridge of Cerro Torre, Tyler’s friend Danny offered to porter for us for free, just for the experience of seeing the Torre Valley, and I definitely wasn’t purist enough to say no to that! But it doesn’t make any sense for it to be “cheating” if you pay for it, but not cheating if it’s free. Basically, I kinda realized that my purist logic had some large holes in it.

In addition, there is the fact that hiring porters to near the base of the mountain is considered completely normal and accepted in pretty much all of the Himayala, even though many mountains in the Himalaya are relatively easily accessible. For example, the approach to the normal route on Ama Dablam is easier than the approach to Cerro Torre in almost every way. The truth, of course, is that porters are “normal” in the Himalaya because manual labor in the Himalaya is affordable for foreign climbers. I think that the biggest downside to normalizing the hiring of porters is it makes a climbing objective a bit easier for those who can afford to hire a porter… but of course something being easier to achieve for those with the financial resources is an injustice that pervades nearly every aspect of human culture.

Climbing: You wrote that during your 2010 solo of Exocet, you “free soloed a lot of the route, including a bunch of the crux ice chimney. Now 15 years older, and a bit wiser, I rope soloed all except the really easy sections.” What specifically encouraged you to rope solo more this year? What prompted this new “wisdom”?

Haley: Personally, I have never considered free soloing to be “better style” than rope soloing, at least when it comes to alpine climbing. Some people do, and I think that is a symptom of a general problem in the climbing community, particularly the North American climbing community, of celebrating risk taking specifically. Personally, I value athleticism, I value intelligence, I value skill and talent, I value dedication, I value perseverance, I value the application of hard-won experience, but I don’t value “boldness,” which is just a euphemism for risk taking.

That definitely does not mean that I am one of those people who is against free soloing! I have been free soloing on a regular basis since I was about 12 years old, and any experienced alpine climber knows that free soloing is a completely integral part of alpine climbing. Like any kind of climbing the risks have to be taken into consideration, and since the consequence of a fall while free soloing is death, it should obviously only be done on terrain where the climber is extremely confident that he or she won’t fall.

If you are trying to climb a mountain by yourself, it is natural to free solo the terrain where you are extremely confident not to fall, and rope solo the terrain where you are less sure. Rope soloing has the advantage of being safer, but the disadvantage of being extremely costly in terms of time and energy. Free soloing has the disadvantage of being less safe, but the advantage of being extremely efficient in terms of time and energy.

When I soloed Standhardt in 2010 I only rope soloed as much as I did because I thought that I wouldn’t have enough time and energy to complete the climb if I rope soloed more of it. This time, having just recently rope soloed nearly all of the Ragni Route, I had a lot more confidence in my ability to endure the greater endurance challenge of rope soloing.

In addition, there is another reason. There is a generally held belief in climbing that free soloing makes more sense while ice climbing than while rock climbing. I think this belief came about in the 1970s because ice screws were so difficult to place that trying to protect ice climbs often seemed not worth the effort. In the modern era, I have realized that I actually feel the opposite: I generally think that free soloing makes more sense on rock than on ice, for a given feeling of climbing difficulty. The reason is that while rock climbing you can easily sense how secure you are or not, so you can free solo very carefully without expending much more energy than you would if you were climbing roped. In ice climbing you certainly get some sense of how solid your ice axe placements are, but it is not nearly as certain of a sense as when grabbing rock holds barehanded. Because of this, when I free solo ice climbs I make my axe placements much deeper than if I were climbing roped. This uses a lot more time and energy, as does removing your axes from those deep placements. In 2010 I free soloed roughly the first half of the crux ice chimney, but I was climbing very slowly, and using a lot of energy to really sink my picks deep in the ice. So, even though rope soloing those pitches this time was overall slower and more energy consuming, at least I got to climb those pitches in a similarly efficient manner than I would’ve belayed by a partner, not having to make super deep axe placements every time.

Climbing: When you wrote: “The most satisfying part of the experience was seeing how relaxed and at ease I felt during the climb, compared to my younger, less-experienced self 15 years ago,” do you have a specific example here to cite? I.e., a pitch where 26-year-old Colin would have felt was quite intense, yet 41-year-old you thought it to be not a big deal?

Haley: I think the climb felt more relaxed in part because I simply am a lot more experienced now than I was then, and have a lot more hard solo ascents under my belt. In addition, starting this climb already tired, I didn’t really have the physical or mental energy to rush, and was kind of forced to adopt a chill mindset from the beginning. I just told myself that the weather wasn’t meant to get imminently bad, and I had a really good headlamp with me, so I didn’t need to stress about time. Lastly, this time I only free soloed the really easy sections, and I’m sure that also contributed to the whole climb feeling more relaxed.

Climbing: Can you describe your rope-solo system?

Haley: Well, let me start off with the disclaimer that I definitely do not consider myself to be a rope soloing expert. It’s something that I do every now and then when a specific objective inspires me enough to put up with all the hassle that it involves!

Before this trip, I’m pretty sure that the last time I did any rope soloing was during my 2023 winter attempt on Cerro Torre. During my six days back in Chamonix before this trip I literally watched a Youtube video of Brent Barghahn explaining his system, and I more-or-less copied it, except that I kept the spare rope in a backpack on my back. I asked around to friends of mine in Chamonix, and my friend Dave Searle luckily had a Grigri+ to lend me, in addition to five of these little plastic things that Brent Barghahn designed to prevent “back-feeding”—they aren’t necessary, but they save a bit of time compared to using elastic prussiks. A couple mornings before flying to Argentina I went to an easy crag in Servoz and rope soloed a few pitches to make sure that the system was working well.

For both Cerro Torre and Standhardt I was climbing on an 80-meter Edelrid “Starling Protect,” which is a burly half rope, advertised as 8.2mm, but I think it is realistically 8.5mm. I wouldn’t have been comfortable using this rope on a predominantly rock route of similar length and difficulty, but for these predominantly ice routes I think it was a reasonable choice. Using an 80-meter rope allowed me to make very long pitches, and thereby save time on the various maneuvers required at each belay.

The post Days After Cerro Torre, Colin Haley Makes First Winter Solo of Patagonia’s Aguja Standhardt appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

From the state with the most fatalities, to the most common injury, preview some fast stats from the 2025 ‘Accidents in North American Climbing’

The post 9 Interesting Stats From 210 Climbing Accidents Last Year appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Nothing teaches you a lesson like making a mistake yourself. The next best thing, however, is reading about other climbers’ mistakes in Accidents in North American Climbing (ANAC), published annually by the American Alpine Club. Learning from the accidents of others is a valuable way to improve your systems, dial your safety practices, and avoid complacency.

Before diving into the accidents, the 2025 ANAC opens with valuable insights on making your next rappel safer. But the most fascinating story this year investigates the role of human error in accidents. Climber and researcher Dr. Valerie Karr searched for themes in ANACs from 2005 through 2024. In her surveying, she found the six most common ways human error leads to accidents. Climbing will also be publishing a story specifically related to Dr. Karr’s insights soon.

ANAC 2025 (Volume 13, No. 3, Issue 78) is now available for pre-order, with the official release in early October. Here are nine surprising takeaways from the report.

1. 2024 and 2023 were the highest fatality years since the 1950s in the United States.

Since the American Alpine Club first started soliciting accident reports some 75 years ago, between 10 and 43 climber deaths occurred per year. From 2022 to 2023, fatalities in the U.S. surged by 22% to a total of 51. In 2024, 49 total fatalities occurred in the U.S., the second highest number since the AAC started keeping records.

It was also a high year for climber injuries in the U.S., with 174 reported injuries, 15% more than 2023. This was also the second highest injury count in the U.S. since AAC records begin. Total accidents were also high, with 190 reported in the U.S., the second highest number since the 1950s.

While the reported incident volume is always higher in the U.S., our neighbors to the north had a more moderate year in 2024. The 2025 ANAC documents 20 total accidents from Canada (down 35% from 2023), 25 injuries (down 32%), and nine fatalities (up 23%) in 2024.

2. Before you blame “gym to crag” on rising incident rates, consider who got into more accidents.

Some climbers like to grumble about novice climbers who don’t know what they’re doing, whether they’re new to the sport or making the transition from gym to crag. But in 2024, expert climbers sustained far more accidents than beginners. While the experience level of a large volume of climbers involved in accidents remains unknown, we do know that 33 expert climbers got into accidents last year, while only six beginners and two intermediate climbers had accidents.

3. By far, California saw the most accidents and injuries reported in 2024.

ANAC uses geographic districts that include Canadian provinces (e.g., Alberta), Canadian territories (e.g. the Yukon and Northwest), U.S. regions that group together states with lower data thresholds (e.g., the Southeast), and U.S. states that are major climbing destinations (e.g., Colorado).

Unsurprisingly, California gets its own geographic district—and sees a lot of action. In the last calendar year, climbers in California reported by far the most accidents and injuries of any geographic district. In 2024, 40 climbing accidents occurred in California, followed by Colorado (28) and Washington (26). Thirty-four of those accidents involved injuries; runner-up districts for injuries across North America include the U.S. Northeast (26), and the state of Washington (24).

This brings California’s total accident count since 1951 to 1,798—second only to Washington, which has 2,134 reported accidents in the books.

4. But California did not see the highest fatality rate of 2024.

In 2024, Washington and Colorado both experienced 11 fatalities, the most of any other district. California accidents led to 10 deaths. This brings both Washington and California to a total of 378 reported climbing fatalities since 1951. The Colorado climbing community has experienced 295 deaths to date.

5. More accidents struck on the ascent than the descent.

Rappelling gets a bad, well, rap. But of all the accidents reported across North America in 2024, 100 occurred while climbers were ascending. Compare that with 46 accidents sustained during the descent. This trend is on par with historical data. (Note that with 46 of the 210 accidents, it was unknown whether problems arose on the way up or down, and 11 accidents also occurred on neither the ascent or descent).

6. The most common injury of 2024? Lower extremity fractures.

Those pesky ledges, nasty ground falls, and more hazards of the hobby led to 30 lower extremity fractures among climbers last year. Historically, lower extremity fracture has ranked ninth in terms of most prevalent injury. But the AAC only began breaking out fractures by location in 2021, and fractures in general have dominated climber-related injuries since the records begin for this datapoint in 1984.

The next most common injuries were hypothermia (17 cases in 2024), and head injuries/traumatic brain injuries (16 incidents in 2024).

7. Alpine climbing involved more accidents than any other discipline.

As usual, alpine climbing/mountaineering led to more accidents than any other type of climbing.

In 2024, 71 accidents occurred on alpine-style climbs. The second most accident-prone discipline of 2024? Trad climbing, with 52 total accidents. Sport climbing comes in third, with 35 accidents last year. Other categories include ice/mixed climbing, big wall climbing, bouldering, toproping, free soloing, and ski mountaineering.

But before you make assumptions about alpine climbing or trad climbing being more dangerous than, say, ice climbing or free soloing, keep in mind that these aren’t accident rates, only accident totals. The higher accident volume might be indicative of the popularity of each discipline. While nine people had accidents free soloing or deep water soloing in 2024, for example, the accident rate might still be quite high considering how few people climb ropeless.

8. A lot of climbers got lost last year.

After falling while rock climbing, the second leading cause of accidents in 2024 was becoming lost or stranded. With a total of 31 accidents involving getting stuck or off track, this is a good reminder to us all to download a navigation app, bring along a satellite comms device, and tell someone where we’re going and when we expect to return. Oh, and brush up on those self-rescue skills!

9. Male climbers got in a lot more accidents than female climbers.

Last year—and historically—men experienced more accidents than women. While this may lead you to draw some conclusions, keep in mind that this data doesn’t take into account the total numbers of men vs. women climbing. That said, 134 accidents involving men, compared to 40 accidents involving women in 2024, represents a pretty big gender gap.

Whether it’s about who’s actually climbing—or something else—we also saw a similar trend in our 2024 Climbers We Lost. Among 38 fatalities in our community, only one person on our list was a woman.

The post 9 Interesting Stats From 210 Climbing Accidents Last Year appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

A new open letter from Sébastien Berthe, Sean Villanueva O'Driscoll, Katherine Choong, and more signees aims to keep fossil fuel-based sponsorships out of the sport.

The post Pro Climbers Urge IFSC and the Climbing Community to Swear Off Fossil Fuel Ties appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

As competitive climbers converge in Seoul for the IFSC World Championships this weekend, several pro climbers and organizations have signed an open letter written by Cool Down, also known as the Sport for Climate Action Network. The letter, “Climbers for a Fossil Free Declaration,” calls upon the International Federation of Sport Climbing (IFSC), national climbing federations, and the wider community to reject all sponsorships from fossil fuel companies.

By signing the letter, climbers promise to reject support from fossil fuel companies, as well as carbon-intensive industries, including aviation and conventional automakers. Signees also pledge to use their platform to advocate for positive climate action.

This initiative follows the IFSC’s controversial partnership last year with Saudi Arabia for the NEOM Masters. Critics swiftly condemned the deal as a concerning example of “sportswashing” by a petrostate known for obstructing climate action, according to the independent scientific Climate Action Tracker. The open letter says the event represents the “wrong direction” for the sport’s sponsorship landscape.

“We urge the climbing community, event organizers, and national and international federations to take a stand by declaring a ban on high-carbon advertising,” the letter states. “As climbing grows, we must ensure our sponsors align with our values—protecting the future of the planet over profit.”

Climbers aren’t the only ones rallying their sport to do better. In early August, Cool Down announced a similar letter directed toward athletes and organizations in all sports. This cross-sport declaration makes the same demands as the open letter climbers have written: accept no fossil fuel-based sponsorships and use your platform for climate advocacy.

While climbers can also sign the Fossil Free Declaration, the climbing-specific open letter is a way to raise the profile of this initiative within the climbing community. So far, the letter has garnered 28 signatures, including Sébastien Berthe, Kilian Jornet Burgada, Lattice Training, Ecopoint Climbing, Sean Villanueva O’Driscoll, and Katherine Choong.

“I signed the declaration because as athletes, we have a responsibility to push for a future where sport is not tied to industries fueling the climate crisis,” Choong shared with Climbing. “Climbing teaches respect for the natural world, and I believe our sport should reflect that by ending partnerships with high-carbon sponsors.”

The letter makes it clear that this isn’t just about doing the right thing—climate change also critically imperils the sport with increased hazards. It states: “As glaciers retreat, rockfalls become more frequent, and mountain environments grow more dangerous, climbing faces an existential threat from the very forces that seek to profit from its destruction.”

Liam Killeen, a climber and campaigner with the Cool Down Network and Badvertising, helped write and circulate the climbing-specific open letter. He told Climbing that the strong environmental advocacy among many professional climbers sparked this initiative. The NEOM Games, flagged by climbers James Pearson and Caro Ciavaldini (pictured climbing an E8/5.13b route in this article’s lead image) as a concerning case of “sportswashing,” served as the specific catalyst.

“As lovers of the mountains and nature, it’s obvious why we would want to sign the open letter,” Pearson and Ciavaldini shared. “While it’s tempting to chase after the financial support these sorts of new, big budget partnerships might bring, it’s important to stay in touch with your base values, and think about what impact short-term gains like these may have on future generations.”

Rather than setting a specific goal for the number of signees, Killeen explained that he hopes the open letter will strengthen Cool Down’s position in conversations with key stakeholders such as the IFSC, the British Mountaineering Council, and more organizations. More broadly, Killeen said he hopes that the letter “raises awareness in the climbing community about the risk of harmful sponsors moving into the space as the sport continues to grow.”

While climbing has remained relatively insulated from fossil fuel sponsorship compared to sports like football or cycling, its rapid ascent as an Olympic sport in 2020 makes it an increasingly attractive potential investment for polluting companies. The declaration positions climbing to set a powerful example, demonstrating that sport can grow and thrive without the backing of companies that actively exacerbate the climate crisis. The message is clear: The future of climbing—and the planet—depends on a commitment to a fossil-free future.

The “Climbers for a Fossil Free Declaration” open letter is not only an initiative for pro climbers and organizations. Any interested climber can sign here.

The post Pro Climbers Urge IFSC and the Climbing Community to Swear Off Fossil Fuel Ties appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Both parties were on the non-technical Clear Creek route. We spoke with the local sheriff’s office and Shasta’s lead climbing ranger to find out what happened, and why.

The post Two Climbers Died on Mt. Shasta’s Easiest Route. What Went Wrong? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Two fatal falls occurred on California’s Mt. Shasta (14,179ft) in the past month, both on the mountain’s “easiest” late-season route, Clear Creek.

At first glance, the deaths are surprising. By September, the ultra-prominent volcano is largely free of snow, often rendering the Clear Creek route a non-technical hike. “It’s a slog of a scree slope,” said Sage Milestone of the Siskiyou County Sheriff’s Office.

Yet Milestone and the peak’s lead climbing ranger, Nick Meyers of the U.S. Forest Service, told Climbing that the deaths highlight a stark reality. Even on an “easy” route, poor decision-making can compound into serious accidents, and even death.

Uncontrolled glissade leads to fatal slide

The most recent death occurred on September 12. Argentinian and 45-year-old Silicon Valley executive Matías Travizano was descending from the mountain when he wandered off route, according to Milestone. Although Travizano had arrived at the mountain alone, he linked up with two other men hiking at the same pace, and the trio summited together. Travizano and one other man began to hike down slightly ahead of the third, who later reported the accident.

Clouds had socked in the peak and visibility was poor. As the men descended from the main summit plateau, all three veered off-route to the east. “It’s pretty steep, and it’s all scree, so it’s easy to lose the trail, particularly with bad visibility,” Milestone said. She added that no clear landmarks exist to identify the way down. The party realized they were off route when, at around 13,500 feet, they reached a perennial snowfield, near the uppermost tip of the Wintun Glacier.

The men were hiking without crampons, ice axes, Microspikes, or other traction equipment for traveling across snow and ice. But instead of hiking to regain the correct, snow-free route, they decided to glissade down the snow and ice to save time. “They didn’t want to climb back up and regain a bunch of elevation,” Milestone explained. But jagged, exposed rock littered the snowfield, and it was incredibly icy due to the low temperatures. “It was a very bad time to glissade,” Milestone said. Chiefly, without ice axes, the men had no way to control their slide or self-arrest.

Soon after beginning to slide, Travizano lost control and gained speed rapidly. After plummeting down the slope around 300 feet, he collided with a large rock, knocking himself unconscious. Witnessing this, the second climber spent a few minutes trying to pick his way down the icy slope to reach Travizano and render aid.

He came close. But when he was roughly 80 feet up slope from Travizano, the man “regained consciousness, tried to stand up, and just fell,” Milestone explained. The 45-year-old continued to slide at an increasing rate of speed, down into gloom and out of sight.

At this point, it also dawned on the climber who saw Travizano fall that he was stranded on the same icy slope, and afraid to move. “He couldn’t get off, and he was having a really hard time self-rescuing from that position,” Milestone said. The third climber, who had descended more slowly from above, was the most experienced in the party, according to Milestone, and was able to coach this man off the steep slope. The two later regained the trail using a GPS device and called in the accident. Travizano’s lifeless body was located by 6:45 p.m., some 2,000 feet below, according to Milestone. His body was not recovered until the following day, however, due to storms and increasingly poor visibility.

Travizano, was a native of Argentina, but lived in the United States in recent years. He was the founder and former CEO of GranData—a Silicon Valley startup dedicated to data analysis and developing new forms of artificial intelligence—which he sold last year. “He had been on Aconcagua and a few other South American mountains,” Milestone said. “This was definitely not his first mountaineering expedition, but it was his first time on Mount Shasta.” A friend of Travizano’s remembered him as a brilliant mentor, “a special human being,” and a “great leader” with a love of nature. He is survived by his wife and son.

Two men split up to find their camp, only one makes it back

This season’s second fatality on Mt. Shasta occurred just a month earlier, on August 16, on the same route. A pair of climbers had summited via Clear Creek, also during a stormy period and without wet weather gear. As they descended to their camp, they became lost. It was their first time on the mountain. “They got on the wrong ridge, took it down to like 11,000 feet—completely off trail—and couldn’t find their basecamp,” Milestone said. “So the two men split up and went looking in opposite directions.”

One individual found the camp, and because he had cell reception, managed to call his partner. The man managed to communicate to his partner that he was lost, but was clearly suffering from altitude sickness. He was disoriented, and borderline incoherent. “The guy was trying to explain where he was at, but then they lost service,” Milestone said.

Storms, which had been brewing on the peak all day, quickly worsened. “It started raining, heavy cloud cover came in,” Milestone recalled. “Siskiyou Search and Rescue, CHP [California Highway Patrol] Air Ops, and the climbing rangers all searched through the night on that one, but they couldn’t find him.”

The man was later discovered at the bottom of a steep cliff band, “wedged between an ice sheet and the cliff.” He had sustained significant head trauma, and was found alive but unconscious. He died in the hospital two days later. “People have a very lax view of this route,” Milestone said of Shasta’s Clear Creek. “We see a lot of accidents this time of year on that route, because it attracts the least experienced folks, who want to take a stab at climbing Shasta in a non-technical way. Then you get some pretty gnarly weather, or just lack of experience, and bad stuff can happen.”

Just a few days before this fatality, on August 10, another serious but non-fatal glissading accident occurred. An unnamed climber lost control while glissading down another route, Avalanche Gulch, tumbling several hundred feet down the mountain. The climber was injured, but was successfully rescued. In total, Milestone said there have been nine rescue operations on Shasta this season.

What do Shasta’s climbing rangers have to say?

The Forest Service’s Nick Meyers is Shasta’s lead climbing ranger, with 22 years of experience working the peak. He also manages the Mount Shasta Wilderness Program, and serves as director of the Mt. Shasta Avalanche Center. “We try hard to spread the gospel of safe mountaineering practices, but you can’t hit home runs all day long,” Meyers told Climbing.

Shasta usually sees between one and three fatal accidents and a dozen rescue operations each year, so the two deaths and nine calls so far in 2025 don’t exceed average incident levels. According to Meyers, prime climbing season on Shasta begins, snowfall depending, in late April. The season continues through May and June, tapering off after early July, when snow begins to deteriorate.

He explained that although Clear Creek is generally a safe, non-technical route, it’s still a long, steep slog, with extensive elevation gain. If parties venture off-route, anything can happen. When the route experiences good conditions—and is followed correctly—the route is what Meyers and his rangers recommend for late-season climbs.

He also said that the fact that the men involved in the September 12 accident were not carrying crampons or axes wasn’t necessarily indicative of poor decision-making. “We’ll even go so far as to say, you don’t need to bring an ice axe and crampons for Clear Creek in good conditions,” Meyers said. “This is granted—in all capitals—that you stay on the route. Don’t get Casual Day Syndrome. Don’t treat it as just a hike.”

The September 12 incident resulted from not just one, but multiple bad decisions, Meyers said. The men climbed despite weather reports forecasting poor conditions later in the day. This led to them summiting in a whiteout. This poor visibility, coupled with inadequate navigation, contributed to their party becoming off-route during their descent, and arriving at the top of the glacier. The decision to glissade, instead of retrace their steps, was another clear blunder. For one, the men had no axes, and the terrain was in particularly poor condition. “This time of the year, the snow is so nasty,” Meyers said. “It’s dirty and icy—a total cheese grater.”

Shasta is one of the few glaciated 14,000-foot peaks in the contiguous United States, and among the most topographically prominent summits on the continent. Like many 14ers, it can morph from a day hike into a serious objective, depending on season, conditions, route choice, and fitness and experience.

Under ideal late-season conditions, Clear Creek can feel like a straightforward hike (this author ran the route in trail shoes in a morning last September). But weather can change in a heartbeat, and staying on-route is crucial. Checking climbing and avalanche conditions in advance can also help anyone vying for Shasta’s summit plan their trip more safely.

“Remember, a route description is for that route,” Meyers said. “If you get off route, you very likely will encounter different conditions.” This climbing ranger’s final piece of advice? “Do not climb into a whiteout or storm. Check the weather. Use navigation tools. Be prepared. In a lot of the accidents we see, folks are checking boxes that are pretty easy to avoid checking.”

The post Two Climbers Died on Mt. Shasta’s Easiest Route. What Went Wrong? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

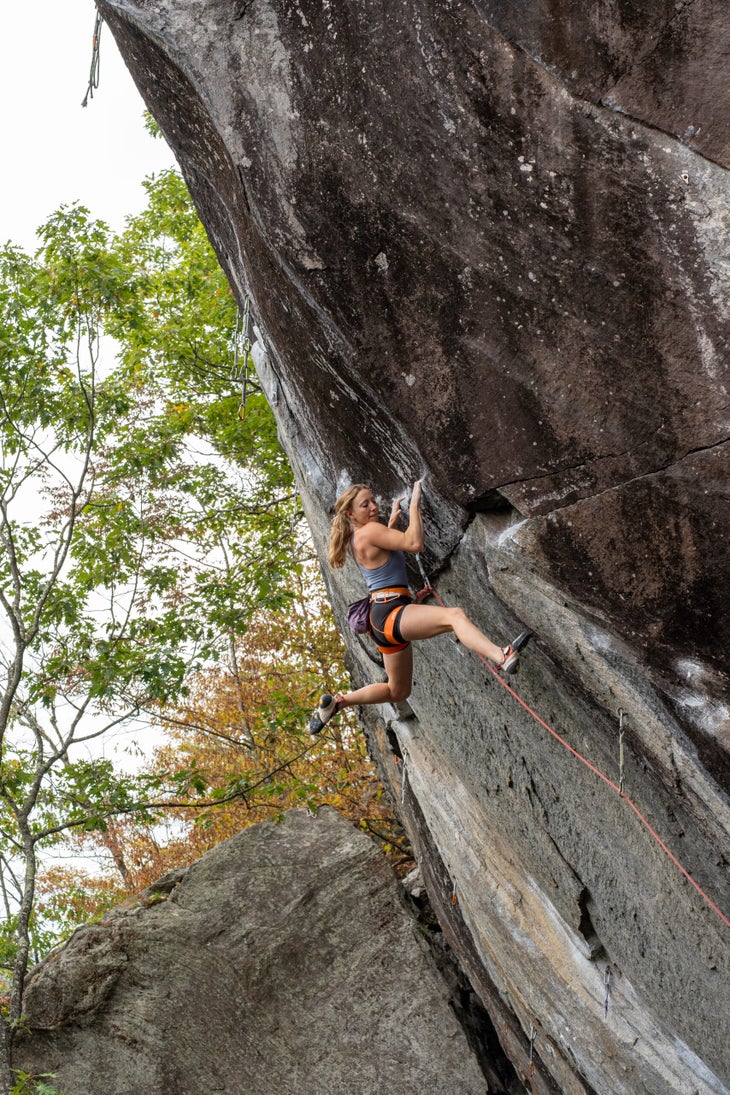

At 5.14d, her new route, ‘Mad Lib,’ is the hardest grade established by a woman in North America since Beth Rodden’s ‘Meltdown.’

The post Michaela Kiersch Just Made History With This First Ascent appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

In between flower-filled strolls and lakeside reading sessions, Michaela Kiersch pulled off the hardest ever first ascent of a sport route by a woman in North America. On September 11, Kiersch freed an open project at Vermont’s Lone Rock Point, dubbing it Mad Lib (5.14d/9a).

“There are existing 5.14s at the wall, and this line is an obvious link through the hardest sections of the cliff,” Kiersch told Climbing.

Mad Lib represents the hardest FA on the continent by a female climber since Beth Rodden’s 2008 takedown of Meltdown (5.14c) in Yosemite. While Kiersch’s FA bests Rodden’s in terms of the grade itself, Meltdown could be considered harder than Mad Lib because it’s a trad climb. Beyond North America, the hardest first ascent ever by a woman remains Sweet Neuf (5.15a/9a+) in Pierrot, France, established by Belgian climber Anak Verhoeven in 2017.

As usual, Kiersch pulled off this historic achievement with casual aplomb. The first woman in the world to climb both 5.15 and V15 also happens to be remarkably relatable. Impressively, this pro climber lives a double life as an occupational therapist. She loves solo travel (case in point: her trip to Switzerland, where she sent Dreamtime, V15). And between cutting-edge ascents, she shares no-filter selfies, carousels mocking Internet trolls, and cinematic homages to her favorite beverage. (No, not AG1 Greens shakes or athletic performance drinks. Just good ol’ Dale’s Pale Ales, one of her sponsors).

We caught up with this Salt Lake City-based climber to find out how she pulled off her latest feat, what else she got into in New England, and where she’s headed next.

Inside Michaela Kiersch’s 5.14d first ascent

“It’s incredible to feel like I can contribute back to the climbing community in this way and start to carve my own path with regard to hard first ascents,” Kiersch says.

Her newest contribution, Mad Lib, marks Kiersch’s second first ascent. She bagged her first first ascent in Kentucky’s Red River Gorge with Goldilocks, which she called 5.14b, but Alex Megos later upgraded to 5.14c. Mad Lib begins on a previously unsent, five-bolt start equipped by Jesse Franklin—local legend Pete Clark bolted the rest of the line. The route then merges with an existing route known as King Tubby (5.14a), at the top of which Kiersch says a “taxing kneebar rest” awaits. After the rest, powerful and dynamic moves lead up “an extremely beautiful arête,” coinciding with the top of Terror Wolf (5.13c).

The fact that Mad Lib includes sections of several other routes inspired its name. “When talking with local Peter Kamitses, the suggested name for this route grew so long and nonsensical that it sounded like a Mad Lib word game,” Kiersch explains. “It was a bonus that this coincided with the hip hop theme on some of the other routes.” Nearby route names like Bring Da Ruckus, Tiger Style, and Ghostface Drilla pay homage to Wu-Tang Clan. In addition to hinting at the word salad of a conglomerate route, Mad Lib alludes to a producer who’s collaborated with rapper MF Doom.

See where Kiersch’s route Mad Lib is located

Mad Lib rises 80 feet tall, but Kiersch says it “climbs much longer” due to its steepness. She spent six days working the route. On day five, she finally linked up the start. All in all, she estimates that she put down between 20 and 30 burns before redpointing it around 9 a.m. on September 11.

The hardest section for Kiersch consisted of “a hard deadpoint to a pinch, followed by a barn door and karate kick.” Alternate beta included turning the pinch into a full crimp, then launching a deadpoint to a sloper. “The movement is stellar and unique!” Kiersch says of the crux moves.

Mad Lib is located on a limestone cliff known as Lone Rock Point hanging over Lake Champlain. “It’s pretty special to find limestone sport routes on the East Coast, and the setting is just surreal,” Kiersch says of why she decided to check out this crag. Her September trip was only her second time in Vermont; when she visited for the first time last February, she “fell completely in love with the climbing community and area.”

Plus, a 5.14c FFA for good measure

“Hardest bolted first ascent in North America by a woman” isn’t the only record Kiersch walked away with from her New England trip. Just two days after she sent Mad Lib, she nabbed the first female ascent of Livin’ Astroglide (5.14c) at Waimea wall in Rumney, New Hampshire.

Livin’ Astroglide follows a black arête, leading to a shared crux with Jaws II and China Beach up top. “With crimps, heel hooks, and pure resistance and recovery climbing, it suited me extremely well,” Kiersch says of the route.

Rumney is actually what first sparked Kiersch’s desire to plan a New England climbing trip. “I’ve always been inspired by the Dosage [a Reel Rock film series] in Rumney,” she says. Then a good friend—and Vermont local—clued her into Lone Rock Point and the open projects there. “After seeing one photo, I was completely sold,” she says.

During her two weeks on the East Coast, Kiersch also spent some time working on Jaws II. This 5.15a route has yet to see a female ascent. She didn’t manage to send, but she noted that she set herself “up well for a return trip.”