We spoke with Haley about his history with Aguja Standhardt, the ethics of hiring a porter, and why he doesn’t value “boldness” in climbing.

The post Days After Cerro Torre, Colin Haley Makes First Winter Solo of Patagonia’s Aguja Standhardt appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Veteran Patagonia climbers know one thing to be true: if the wind isn’t howling, and it’s not nuking snow or rain, you’d better go climbing—it could be months until good weather returns to one of the stormiest places on earth. Colin Haley, arguably the most accomplished Patagonia climber of all time, takes this approach as gospel. And so it was no surprise that after just six days of rest following his first solo-winter ascent of Cerro Torre, the 41-year-old American headed back into the Torre Massif when more good weather rolled in.

This time, Haley was set on the smallest of the three “Torres”: Aguja Standhardt, which he made the first-ever solo of in November 2010 via Exocet (WI5 5.9; 500m). Canadian Marc-André Leclerc made the second solo of Standhardt, and the first free solo, just days after the end of Austral winter, in September 2015, via Exocet’s “sit start” Tomahawk (M7 WI6). Haley says it was the Austrian Tommy Bonapace who initially inspired him to climb Standhardt alone. In April 1994—before forecasts or what we now consider the town of El Chaltén—Bonapace soloed to the top of Exocet’s ice chimney before retreating in a storm. According to the online guide Pataclimb.com, Bonapace “climbed free solo, trailing a 100-meter rope behind him and stopping briefly at belays to smoke a cigarette and haul his pack.”

Haley made an Instagram post summarizing this ascent, where he concluded: “This climb was undoubtedly much easier, and much less special, than my recent climb of Cerro Torre, so it felt a bit anticlimactic.” But though it might pale in comparison to Cerro Torre, Aguja Standhardt remains a truly beautiful mountain, and Exocet one of the most spectacular ice climbs on the planet. As Haley made his return home to Chamonix, I caught up with him via Whatsapp to learn a little more about this ascent.

Our interview with Colin Haley

Climbing: How were the conditions on Exocet? A lot of brittle ice or snowy mixed sections?

Haley: I would say that conditions on the route were pretty good. The amount of ice in the chimney was definitely less than the first time that I climbed Exocet, but I think the chimney was in pretty normal condition for the modern paradigm. The mixed pitches were actually in quite good condition, with very little snow or rime on them. The biggest difficulties in terms of conditions were that the ice in the chimney was certainly much more brittle than in summertime, and I had a lot of deep trail breaking on the glacier.

I actually think that in the entire Chaltén Massif, Exocet is probably the route whose difficulty is the least augmented by climbing in the winter season. For one, it is a route that is typically climbed entirely in crampons (as opposed to rock shoes), and also it is east-facing, so it receives sun in what is otherwise the coldest part of the day. In fact, one of the biggest problems with climbing Exocet now in mid-summer is that during good weather windows the chimney often starts to run with water by mid morning. One doesn’t have to worry about that issue in winter!

Climbing: On Instagram, you wrote: “After my recent climb of Cerro Torre I felt extremely tired and satisfied, and would’ve happily not gone mountain climbing for a while. In Patagonia, however, opportunities for alpine climbing are rare, and one doesn’t get to choose when they arrive.” Can you explain your motivations a bit more here? Obviously you know how rare good weather is, but still—you’d completed a very difficult lifelong dream less than a week ago. Why specifically did you head back out into the mountains? Or, in other words, why did you feel uncomfortable with the idea of “wasting” good weather?

Haley: Well, my motivations to go climb Standhardt were the same as any time I go try a difficult alpine climb, it’s just that in this case it took a bit more effort to overcome the inertia of chilling. This is nothing new to me, or other highly motivated climbers who have been in Chaltén with good weather windows coming in quick succession. A couple of the most epic climbs I’ve done in the Chaltén Massif, the Torres Traverse in a day and the Wave Effect Direct in a day, were done with just a few days of rest in town between.

Climbing: Where did you camp? And how much weight did [your porter] Maxy Abasto carry? Previously you’ve talked about how portering in Patagonia, especially in winter, feels like it takes away a big part of the solo challenge, and that it’s not an attractive strategic option for you. How has your opinion on that changed?

Haley: I slept the first night near the Nunatak, a little ways beyond Niponino, and I slept the second night on the glacier right near the base of Standhardt’s east pillar. On that first day Maxy carried 18 kilograms and I carried only 10 kilograms. The second day of the approach was much shorter, but involved a lot of trail breaking, and I was then carrying everything myself, so it felt just as tiring.

You’re right that in the past I have been purist about not using porters in Chaltén. I never did so before last summer, and I certainly think that in general it will still be more “my style” to not use porters in Chaltén, even if the biggest reason is just that I can’t afford porters. The reason that I twice hired a porter during this trip is because it seemed like it would actually make a real difference for me—the first time I had arrived in the middle of the weather window, and knew that it would be really advantageous to make it all the way to the top of Filo Rosso [near the start of the technical climbing on Cerro Torre’s Ragni Route] in very limited time. The second time I was just really tired still from Cerro Torre, and wasn’t sure if I was up for carrying 28 kilograms by myself all that way, and still have enough energy left for the challenge of the climb.

In addition to those very practical reasons, I also have done a fair amount of pondering on this question, and my purist viewpoint started to seem a bit illogical. The biggest reason for that is that most climbers, including myself, use gear caches in the Chaltén Massif during a climbing season, to reduce the amount of weight being carried back and forth on the long approaches. If Person A has three months to spend in Patagonia, then he or she can do a big load carry just once at the start of the season, and then carry a light pack for the remainder of his or her trip. If Person B has only 3.5 weeks off from work, it doesn’t seem fair to fault him or her for hiring a porter to climb in the same weather window as Person A, since they both end up carrying a light pack into the mountains. Also, if you are about to hike into Niponino to go climbing, and your friend mentions that they have ropes and rack cached there and offers for you to use them, of course you won’t say no. So if another person doesn’t have such luck from a generous friend, it doesn’t make sense to fault him or her for hiring a porter. In the last Patagonian summer, when Tyler Karow and I planned to go try the Southeast Ridge of Cerro Torre, Tyler’s friend Danny offered to porter for us for free, just for the experience of seeing the Torre Valley, and I definitely wasn’t purist enough to say no to that! But it doesn’t make any sense for it to be “cheating” if you pay for it, but not cheating if it’s free. Basically, I kinda realized that my purist logic had some large holes in it.

In addition, there is the fact that hiring porters to near the base of the mountain is considered completely normal and accepted in pretty much all of the Himayala, even though many mountains in the Himalaya are relatively easily accessible. For example, the approach to the normal route on Ama Dablam is easier than the approach to Cerro Torre in almost every way. The truth, of course, is that porters are “normal” in the Himalaya because manual labor in the Himalaya is affordable for foreign climbers. I think that the biggest downside to normalizing the hiring of porters is it makes a climbing objective a bit easier for those who can afford to hire a porter… but of course something being easier to achieve for those with the financial resources is an injustice that pervades nearly every aspect of human culture.

Climbing: You wrote that during your 2010 solo of Exocet, you “free soloed a lot of the route, including a bunch of the crux ice chimney. Now 15 years older, and a bit wiser, I rope soloed all except the really easy sections.” What specifically encouraged you to rope solo more this year? What prompted this new “wisdom”?

Haley: Personally, I have never considered free soloing to be “better style” than rope soloing, at least when it comes to alpine climbing. Some people do, and I think that is a symptom of a general problem in the climbing community, particularly the North American climbing community, of celebrating risk taking specifically. Personally, I value athleticism, I value intelligence, I value skill and talent, I value dedication, I value perseverance, I value the application of hard-won experience, but I don’t value “boldness,” which is just a euphemism for risk taking.

That definitely does not mean that I am one of those people who is against free soloing! I have been free soloing on a regular basis since I was about 12 years old, and any experienced alpine climber knows that free soloing is a completely integral part of alpine climbing. Like any kind of climbing the risks have to be taken into consideration, and since the consequence of a fall while free soloing is death, it should obviously only be done on terrain where the climber is extremely confident that he or she won’t fall.

If you are trying to climb a mountain by yourself, it is natural to free solo the terrain where you are extremely confident not to fall, and rope solo the terrain where you are less sure. Rope soloing has the advantage of being safer, but the disadvantage of being extremely costly in terms of time and energy. Free soloing has the disadvantage of being less safe, but the advantage of being extremely efficient in terms of time and energy.

When I soloed Standhardt in 2010 I only rope soloed as much as I did because I thought that I wouldn’t have enough time and energy to complete the climb if I rope soloed more of it. This time, having just recently rope soloed nearly all of the Ragni Route, I had a lot more confidence in my ability to endure the greater endurance challenge of rope soloing.

In addition, there is another reason. There is a generally held belief in climbing that free soloing makes more sense while ice climbing than while rock climbing. I think this belief came about in the 1970s because ice screws were so difficult to place that trying to protect ice climbs often seemed not worth the effort. In the modern era, I have realized that I actually feel the opposite: I generally think that free soloing makes more sense on rock than on ice, for a given feeling of climbing difficulty. The reason is that while rock climbing you can easily sense how secure you are or not, so you can free solo very carefully without expending much more energy than you would if you were climbing roped. In ice climbing you certainly get some sense of how solid your ice axe placements are, but it is not nearly as certain of a sense as when grabbing rock holds barehanded. Because of this, when I free solo ice climbs I make my axe placements much deeper than if I were climbing roped. This uses a lot more time and energy, as does removing your axes from those deep placements. In 2010 I free soloed roughly the first half of the crux ice chimney, but I was climbing very slowly, and using a lot of energy to really sink my picks deep in the ice. So, even though rope soloing those pitches this time was overall slower and more energy consuming, at least I got to climb those pitches in a similarly efficient manner than I would’ve belayed by a partner, not having to make super deep axe placements every time.

Climbing: When you wrote: “The most satisfying part of the experience was seeing how relaxed and at ease I felt during the climb, compared to my younger, less-experienced self 15 years ago,” do you have a specific example here to cite? I.e., a pitch where 26-year-old Colin would have felt was quite intense, yet 41-year-old you thought it to be not a big deal?

Haley: I think the climb felt more relaxed in part because I simply am a lot more experienced now than I was then, and have a lot more hard solo ascents under my belt. In addition, starting this climb already tired, I didn’t really have the physical or mental energy to rush, and was kind of forced to adopt a chill mindset from the beginning. I just told myself that the weather wasn’t meant to get imminently bad, and I had a really good headlamp with me, so I didn’t need to stress about time. Lastly, this time I only free soloed the really easy sections, and I’m sure that also contributed to the whole climb feeling more relaxed.

Climbing: Can you describe your rope-solo system?

Haley: Well, let me start off with the disclaimer that I definitely do not consider myself to be a rope soloing expert. It’s something that I do every now and then when a specific objective inspires me enough to put up with all the hassle that it involves!

Before this trip, I’m pretty sure that the last time I did any rope soloing was during my 2023 winter attempt on Cerro Torre. During my six days back in Chamonix before this trip I literally watched a Youtube video of Brent Barghahn explaining his system, and I more-or-less copied it, except that I kept the spare rope in a backpack on my back. I asked around to friends of mine in Chamonix, and my friend Dave Searle luckily had a Grigri+ to lend me, in addition to five of these little plastic things that Brent Barghahn designed to prevent “back-feeding”—they aren’t necessary, but they save a bit of time compared to using elastic prussiks. A couple mornings before flying to Argentina I went to an easy crag in Servoz and rope soloed a few pitches to make sure that the system was working well.

For both Cerro Torre and Standhardt I was climbing on an 80-meter Edelrid “Starling Protect,” which is a burly half rope, advertised as 8.2mm, but I think it is realistically 8.5mm. I wouldn’t have been comfortable using this rope on a predominantly rock route of similar length and difficulty, but for these predominantly ice routes I think it was a reasonable choice. Using an 80-meter rope allowed me to make very long pitches, and thereby save time on the various maneuvers required at each belay.

The post Days After Cerro Torre, Colin Haley Makes First Winter Solo of Patagonia’s Aguja Standhardt appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

The 11 best climbing pants for sport, bouldering, trad, the gym, and more—plus our pant pick for all-around climbing.

The post We Tested 42 Different Climbing Pants. These Pairs Came Out on Top. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Take a look around any crag and you’ll likely see a wide variety of climbing pants. Sure, there are plenty of climbers wearing purpose-built pants with four-way stretch and techy features. But we also see people climbing in leggings, billowy linen, the occasional Lycra tight, Carhartts, and denim (the horror!). While there are many pants that you can make work for climbing, if you’re in search of the best climbing pants, you’re in the right place. We put dozens of pairs to the test, from technical bottoms and department store leggings to burly workwear.

To help guide you toward the best pair, we identified the top all-around rock pants for anyone who doesn’t want to invest in multiple pairs. We also picked top pairs for sport climbing, bouldering, the gym, and trad/multi-pitch/alpine.

Searching for climbing pants for women? While we offer recommendations for both men and women here, we also created a separate women’s-specific guide to the best pants with more detail and additional recommendations.

The post We Tested 42 Different Climbing Pants. These Pairs Came Out on Top. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

How the 41-year-old American made the first winter solo of Patagonia’s famed Cerro Torre.

The post Cerro Torre, Solo, in Winter: An Exclusive Interview with Colin Haley appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

It was two hours after sunset but the darkness didn’t make a difference to Colin Haley. He was wedged in a vertical, chest-width crevasse just below the summit of Patagonia’s Cerro Torre, squirming for purchase amid the ancient glacial ice. “It was like [Yosemite’s] Harding Slot, but of ice,” Haley told Climbing. He’d left nearly everything at the base of the crevasse in order to fit inside—his extra jacket and gloves, Grigri, helmet, food from his chest pocket—and still could just barely squeeze through. Even without a helmet, when Haley turned his head, his headlamp would get knocked to the side. By 9:30 p.m., he’d been in that crevasse for over two hours with no clear end in sight. But he was determined. “I thought: either I make it through this crevasse somehow, or my attempt is finished.”

A change of plans

Colin Haley had originally planned to spend the entire summer in Pakistan’s Karakoram mountains, first attempting K7 (6,934m) with partners and then pursuing a solo ascent elsewhere in the range. But when temperatures soared to frighteningly high levels, leading to increased rockfall and challenging travel, Haley realized he would have to pivot elsewhere. “I knew Patagonia in winter was going to be the opposite of too hot and melted out,” Haley said. “Freezing my ass off sounded appealing, in comparison.”

The pivot was notably similar to three years ago, when Haley aborted an unseasonably dry solo trip to the Canadian Rockies. After seeing the sad state of the area’s summer snowpack, he flew to El Chaltén and ultimately made the first solo ascent of the Supercanaleta (5.9 WI4 M5/6; 1,500m) on Cerro Chaltén (Fitz Roy) in Austral winter.

This year, Haley arrived in El Chaltén in early August and immediately began bringing loads of equipment into the mountains. He planned to solo Cerro Torre’s line of first ascent, the Ragni Route (WI5+ M4), which tackles sections of vertical rime-ice and gains roughly 1,000 meters from the start of the technical climbing. The Ragni may technically be the easiest line on Cerro Torre, but it also has the longest approach of any route in the massif—over 45 kilometers of variable mountain terrain. “As soon as I arrived in town my goal became: get as much of my gear as close to the base of the route as possible, as soon as possible,” Haley said. He made four gear-portering trips into the mountains—totalling seven-and-a-half labor-intensive days—to ultimately deposit a large gear cache on top of Filo Rosso, a protected campsite near the start of Ragni.

Climbing the Ragni

Haley departed town on September 4 and skied in to the base of Cerro Torre in one long day. He spent a second, short day climbing from the basin (called Circo de los Altares) up to the top of Filo Rosso, encountering brief sections of mixed and steep ice up to M4, which he had fixed with a short length of rope. From that campsite, the “real” climbing of the Ragni begins: 600 meters of alpine ice, blocky mixed terrain, and the airy, poorly protected rime-ice flutings which the Torre group is infamous for.

On September 6, Haley packed up his bivy and began climbing around 6:45 a.m. He free soloed from his campsite to about one rope-length above the Col of Hope, and then rope soloed nearly everything after. Haley said that with a small pack he would have been comfortable free soloing roughly 50 percent of the Ragni’s terrain, “but due to the weight of my pack, filled with wintertime bivy gear, it was not appealing to me,” he explained.

Haley’s first day on route was a big one. He dispatched all but the final three crux pitches of the Ragni and bedded down around 3 a.m. Conditions had been surprisingly good—”I’ve definitely climbed the route with significantly more rime than it had now,” he said—but even so, the Ragni was in full winter condition, with brittle ice and plenty of excavating to do.

The following day, with just three pitches to climb, Haley left camp at 11 a.m. and prepared for what he knew would be the crux (typically, the Ragni increases in difficulty the higher you climb, with the very last pitch being the hardest). The first pitch went by easily, but the second required a lot of time-consuming digging through rime to reach solid protection and axe placements.

“But the real story is that the right side of Cerro Torre’s southwest face recently had a massive serac collapse some time within the last nine months,” Haley said. As a result, the right side of the final pitch had plenty of blue ice exposed rather than the typically white sugary snow. Haley beelined for this option, sure that the route was now about to get much more straightforward. He climbed securely up the often-overhanging glacial ice, occasionally aiding off of screws as the previous days’ exhaustion caught up to him.

Haley opted for this right-hand line because he’d spotted what looked to be a tunnel through the mountain near its top. “I thought if I could just get there I’d be home free,” he said. “Normally on that pitch you’re aiming for these tunnels formed by the wind, and once you’re inside it’s way easier and more secure because there’s real ice. But the tunnel I aimed for turned out to be an opening into a crevasse in this miniature glacier on the top of Torre.”

Squeezing through

The crevasse was too narrow to give himself a proper self belay with a Grigri, so Haley fixed his rope to an anchor at the start and made a rudimentary self-belay with a clove hitch instead. He’d arrived at the crevasse entrance just 15 minutes before complete darkness, “which was fortunate because I could just barely see blue light filtering through this ice crack, which gave me just enough hope to not completely give up.”

At that moment, Haley gave himself a “15 or 20 percent chance of summiting.” But he wanted to push on until it was 100 percent clear that he couldn’t make it any farther. “I was also taking time to chip ice out a little bit more than necessary in a few places because I was genuinely scared of getting stuck there,” he said. Haley was certain that if he had fallen and become wedged in the claustrophobic slot he would have eventually died there.

“So I spent two-and-a-half hours in this crevasse, chipping and digging and squirming, and at times I thought this was not going anywhere. I was actually not far from finally bailing when I was hacking away at some snow above me and poked my ice axe out into the night sky,” he said. Haley was slightly disappointed to realize he was not yet on the summit and actually midway up some vertical terrain, but after a few meters of stemming through rime he connected with another tunnel—this time appropriately human-sized—and climbed quickly to the top. “It was a crazy experience. The craziest tunneling experience I’ve ever had,” he said.

Haley was satisfied to have finished the route but anxious to descend. He began down climbing almost immediately. Not long into the descent, while rappelling the steep headwall section, Haley rigged his single 80-meter rope with a Beal Escaper to facilitate a longer rappel. “I started doing the pull/release and the rope didn’t move,” he said. “I feel sure I did at least 200 pulls. And it never came down.” The thought of re-climbing the steep ice to retrieve the rope was unappealing to the exhausted Haley, so he cut the remaining rope and descended the rest of the Ragni in roughly 40 short rappels. “I made a lot of Abalakovs,” Haley joked. “A lot.”

What the first winter solo of Cerro Torre means to Haley

Looking back, Haley believes this is one of the top five climbing achievements of his life—no small title for someone who has climbed the Torre Traverse in both directions, including a mind-boggling one-day ascent with Alex Honnold, in 2016. He also thinks it’s one of his best-ever alpine solos, tied for first with his extremely committing ascent of the Infinite Spur, on Alaska’s Sultana, in the same year.

Part of why this winter solo of Cerro Torre was so meaningful is due to the wide range of skills it demanded Haley to refine. Cerro Torre is certainly a technical mountain, but climbing it in winter requires a skillset that is more Alaskan, or Himalayan: dragging a sled across a glacier, being a proficient skier, bivying multiple nights in extremely cold temperatures—in addition to climbing steep alpine terrain efficiently and with great margin.

Add to that Haley’s personal history with the mountain—this was his third solo attempt of Cerro Torre in winter, and his tenth successful summit—and it’s no surprise that this climb felt extra special. “Solo climbing does have a certain beauty to it—doing something extremely hard, all by yourself, does bring with it a certain level of satisfaction. And I have thought, and still think, since I was 12 years old, that Cerro Torre is the most beautiful mountain in the world.”

For more information about Colin Haley’s ascent, and the history of winter climbing on Cerro Torre, check out his excellent blog post here.

The post Cerro Torre, Solo, in Winter: An Exclusive Interview with Colin Haley appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Three pro climbers faced an insurmountable crux on Jirishanca. Instead of admitting defeat, they invented a new summit (at their highpoint) and marketed their attempt as a grand success.

The post Can You Claim a “New Summit” If You Merely Stopped When the Climbing Got Too Hard? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Last month, professional European alpinists Dani Arnold, Alexander Huber, and Simon Geitl climbed some outrageously beautiful new terrain on Jirishanca (6,125m), in Peru’s Cordillera Huayhuash range. Photos circulated soon after, showing the men jamming steep grey limestone, perched on exposed bivy ledges, and smiling on what looked to be a summit. But the most widely shared image was one taken directly below the mountain’s southeast aspect. In the photo, a bright red line traces a weakness in the steep rockwall before branching onto the East Ridge. The climbers proudly touted their effort as a new route: Kolibri (5.11d A2), which ended on the mountain’s “east summit.”

The only problem? The east summit doesn’t exist.

Where is Jirishanca’s “east summit”?

Climbing has, for better and worse, written extensively about Jirishanca over the last three years. In 2022, Americans Josh Wharton and Vince Anderson freed Suerte (5.13a WI 6 M7; 1,060m) during the same period that Canadians Quentin Roberts and Alik Berg established Reino Hongo (M7 AI 5+ 90° snow). Afterward, the Canadians accepted alpinism’s greatest formal honor: the Piolet d’Or. Two years later, Jirishanca became the backdrop of a great debate when Reel Rock made a film about Suerte—but photoshopped key moments out.

So when I—who’d edited or written no fewer than four in-depth articles about the mountain—first saw the image of Jirishanca marked up with the supposed line of Kolibri, I was surprised I hadn’t heard of an “east summit” before. Wharton had climbed high on the same ridge in 2015 and 2019 before reaching the main summit. Had he ever considered stopping on this so-called sub-peak?

When I connected with Wharton over email, he told me he was unaware of any “east summit.” “I actually reached [the Kolibri team’s] high point on my very first trip to Jirishanca in 2015, climbed well beyond it in 2019, and ultimately made the actual summit in 2022,” he told me. “What they are describing as a ‘summit’ is really just a flat spot in the ridge about six to eight pitches of non-trivial climbing from the actual summit.” Wharton explained that, compared to the relatively straightforward rock climbing that comprises the lower section of the mountain, Jirishanca’s steep, snow-choked summit ridge is actually the mountain’s crux “in terms of logistics, conditions, and tactics.” The summit ridge may not have a flashy mixed or rock grade, but it includes real, consequential fifth-class snow climbing.

Wharton also said that, generally, he was not hyper-critical of those who end alpine routes below the summit. “I’m not a ‘summit guy’ when it comes to trivial snow fields, a five-foot summit boulder problem, or even three pitches of 5.8 atop a 15-pitch 5.13, for instance,” he said. However, for big, technical mountains like Jirishanca, he admits that, for him, “the true summit does count for something.”

I then reached out to Quentin Roberts to ask if he’d heard of an “east summit.” He said no, and sent me a photo of Jirishanca from a more sobering perspective, circling the flat bump which constituted the Europeans’ “summit.”

What were Arnold, Geitl, and Huber thinking?

Thoroughly confused, slightly annoyed, but still hopeful some logical answer existed, I decided to ask Arnold to explain himself. Was he aware of other climbers who recognized the east summit? Was he at all interested in reaching the main summit? Over email, he said he was “not sure” about other parties ending their routes where he ended his, and acknowledged that the team’s ultimate goal was, indeed, to gain the main summit. When Arnold and his team breached the steep rock crux low on the mountain, they felt certain they would stand on top. But conditions would have it otherwise. “It turned out that the most challenging part was not where we thought it would be,” he explained, describing the upper slopes as having “extremely dangerous” snow conditions. “You can dig down a meter and still won’t find any holds.”

During this email exchange with Arnold, any remaining benefit of the doubt I had dissipated. Arnold, Huber, and Geitl had retroactively lowered their definition of success midway through their climb. They wanted the main summit. They realized the main summit was too dangerous/difficult to attain. They looked around, noticed they were on a relatively flat piece of terrain, and decided their “route” ended on that “summit.” That doesn’t seem very sporting to me, and it sets a poor example to any aspiring alpinist who looks up to these professionals.

What they should have been celebrating

I was truly disappointed to realize these climbers had probably invented a new summit merely for the purposes of sharing an archetypal climbing success story. I’m not sure whether their decision was the result of inflated egos or the sponsor-induced pressures of being a modern-day professional alpinist. Regardless, it felt like there was an underlying sense of inadequacy at play. I thought back to something the American alpinist Colin Haley had written for Alpinist in 2016. He titled the Facebook series “No shame in failure.”

“[…] Climbing to the very top of a mountain is always more difficult than climbing only partway to the top of a mountain. … More painful are the times that we badly want to reach the top of the mountain, but the various forces that make alpinism difficult turn us down below. However, just because we’ve failed does not mean we can’t be proud of our effort. … When I see climbers claiming success without reaching the top of the mountain, it makes me believe that there must be some sort of misplaced shame in an attempt. …”

Haley went on to share anecdotes about the numerous near-miss successes of his career, including, most notably, Patagonia’s Torre Traverse (5.11 A1; 2,220m) in a single day with Alex Honnold—save for two straightforward pitches of rime-ice climbing. Haley didn’t pretend there was some new, previously unknown sub-summit two pitches below Cerro Torre’s real summit. He chalked the experience up to an attempt—itself among his best climbing accomplishments—and returned the next year to finish it up.

In the high-stakes game of alpinism, the Jirishanca team’s approach feels like a fundamentally dangerous idea to promote: that “success” only happens if you reach a summit. Instead, I wish they were emphasizing their decision to prioritize safe, secure climbing over achieving their goal. After all, the summit wasn’t impossible, it was unexpectedly difficult. I want to celebrate this team for ending their attempt when the terrain exceeded their risk tolerance. I do not want to celebrate them for inventing a new summit because they felt obligated to share a textbook definition of success. That is not the spirit of alpinism.

Editor’s note: After reading this article, the Italian-Polish alpinist Filip Babicz reached out to Climbing with a photo of Jirishanca from the southwest. He drew an arrow to more accurately depict where the mountain’s “east summit” is:

The post Can You Claim a “New Summit” If You Merely Stopped When the Climbing Got Too Hard? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Each experiment in paring down felt like a real consequential leap—more akin to driving without a seatbelt than merely risking a speeding ticket.

The post What I Learned Trying to Go “Ultralight” in Patagonia appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Climbing in Patagonia is a lot of things but lightweight is not one of them. The area’s granite towers involve a ton of technical climbing (big rack), include some amount of snow and ice travel (crampons, axe), and are many hours or even days from the road (good luck climbing most of them without bivy gear). As a result, the gear you carry holds far more weight than climbing in the Lower 48. “I always thought the [area’s] focus on ultralight was a bit silly and contrived,” my California-based buddy Thomas texted me during my first Patagonia season, in 2023. “And then I started climbing here and now I’m one of the silly crazy people with the ultralight everything.”

I learned many things while hanging around El Chaltén last December, but the most important was how to lighten up my pack. Climbing with partners far more experienced than myself, I learned how to cut down my bivy gear to the utmost minimum. This in turn let me take advantage of brief spells of clear weather—and climb some of the greatest routes of my life. After 10 weeks spread over two seasons in the range, I am by no means an expert on alpine climbing in Patagonia. But I did pester my local partners for their tips and tricks, and I’ve outlined my most relevant learnings below.

I. Big spoon or little?

My first earth-shattering no shit moment came less than one week into my trip. I’d teamed up with the American expat Kiff Alcocer to climb a mixed route on Cerro Pollone, a rarely visited spire rising quietly behind Cerro Chaltén. While packing up in town, Kiff very casually mentioned that I didn’t need to bring a sleeping bag to our high camp, despite us camping on a glacier, and despite it being springtime in Argentina. I quickly agreed, not wanting to seem prudish, but wondered if I was going to freeze my nuts off that night.

Kiff must have sensed my hesitation. He told me about the sleeping bag he would bring for us to share: one which he used on a late-autumn traverse of the Adela peaks and Cerro Torre’s Ragni Route (WI5+; 600m) with Quentin Roberts. The sleeping bag was pretty wide, he promised, and we’d use it like a blanket. We could spoon if it got too cold. We could also bring insulated pants.

I slept great that night. And as I trudged up the glacier in the next morning’s pre-dawn alpenglow, I came to a realization that will be painfully obvious to some and completely mind-blowing to others: Not only are two sleeping bags twice as heavy as one, but individual bags are a hugely inefficient way to maintain your body heat. What is efficient? Two humans with warm beating hearts trapping each other’s heat into one bag. I couldn’t believe I hadn’t shared a sleeping bag before.

II. Just don’t stop

When Kiff and I returned to town after climbing Pollone, I felt like I had unearthed some sort of secret. I’d effectively cut the weight of my sleeping bag in half yet somehow also made it warmer. I couldn’t wait to share my findings with other friends.

Unfortunately, the big reveal of my “discovery” would have to wait, because the next day Colin Haley—known for his climbing speed, including the Torre Traverse in a day—asked if I would climb Aguja Guillaumet with him. Less than 24 hours of clear weather was on the horizon, with high winds from the west. Colin suggested we eschew bivy gear altogether and dash up the east-facing Amy-Vidailhet Couloir (WI 3+ M4; 300m) from town in a day—6,000 feet of elevation and 18 miles, all told. I had previously only climbed the mountain, via a different but similar route, over three days town-to-town. But I agreed to the idea reasoning that an in-a-day approach was the only way we could safely climb in that window. The raging winds would have made camping absolutely heinous.

Colin and I started hiking around 5 a.m. at a conversational pace. After taking multiple snack and stretching breaks, we took turns balancing on Guillaumet’s precarious summit block at 2 p.m. Free from the burden of bivy gear and the cumulative fatigue of multiple days in the mountains, I noticed my legs still felt fresh and snappy. I remained well fed and hydrated. Had the good weather continued, I would have continued climbing for hours. This in-a-day push stood in stark contrast to my tired summit elation the year before, when I’d topped out in the afternoon of my second full day in the mountains.

There is an argument to be made for going slow while alpine climbing. You inevitably see more beautiful sunrises and sunsets. You share moments of quiet satisfaction with your partner. You can lounge on a sunny boulder or in a glacial tarn, then traipse through an alpine meadow. But if you’re working with a very short weather window, you must pick up the pace. After all, thanks to our weather-dodging, superlight tactics, Colin and I were the only ones who got to enjoy Guillaumet that day.

III. Squeeze ‘em tighter

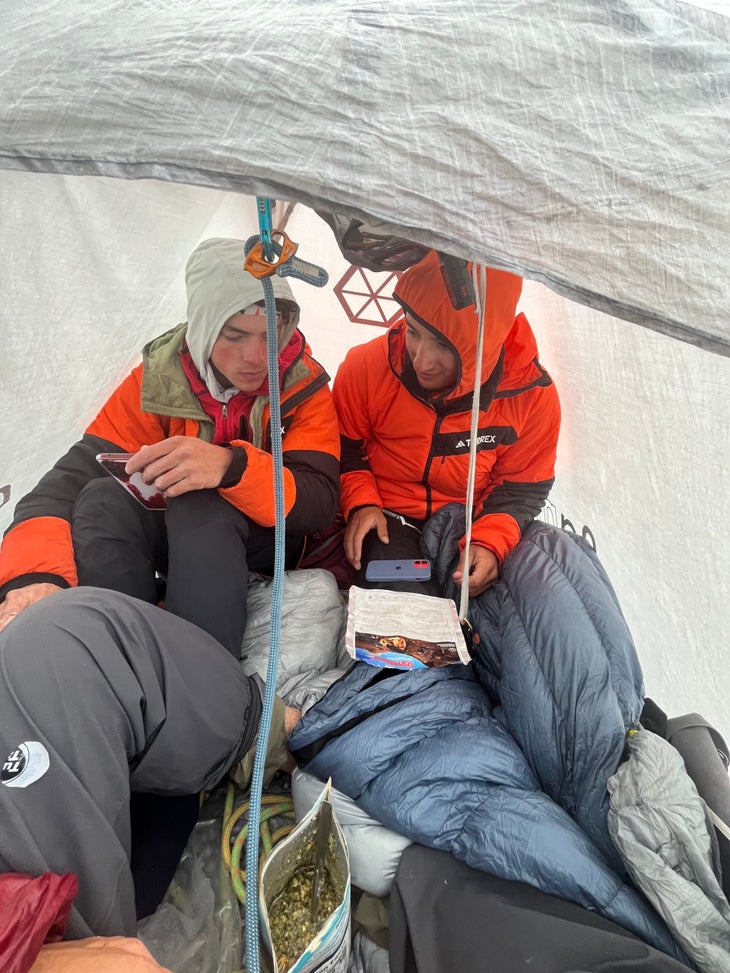

Until last December, I had never crammed more than the recommended number of people into a climbing tent, since two people in a “two person” tent leaves little room for cooking, stretching, or getting dressed. (Or maybe I am a prude!) But clearly I had lots to learn about alpine camping, because when my local friend Tomas Odell suggested we try Torre Egger’s Martin-O’Neill (5.12 M6 WI 4; 3,100ft) with Bauti Gregorini, it seemed like all but a given we’d squeeze the three of us into my tiny two-person tent.

I can’t say I slept well during our night on Torre Egger. But I did pass out for a while until our 3 a.m. alarm roused us. Employing tactic number one, our collective one-and-a-half sleeping bags kept us warm while we pondered the outstanding position we found ourselves in: strapped to Egger’s midheight snowfield, 1,500 feet above the glacier. I like to think that our light packs helped us get there with energy to spare—especially Bauti, who sent the route’s crux 5.12 slab without much difficulty the following morning. Even so, due to my route-finding error, we were forced to bail just 100 feet from the summit when a forecasted storm arrived two hours early. And as we rappelled Egger’s exposed headwall in 40 mile-per-hour winds, I understood that it didn’t matter if we had a tent with us. We couldn’t survive up there. We needed to go down.

Sharing a two-person tent three ways is something I’ve done multiple times since Egger, but I’ve realized that even minor increases in tent width can greatly increase one’s comfort. (Again: no shit.) On Egger, I used the Samaya Assaut2 (reportedly 43in/110cm wide, but due to a design flaw the floor curves up like the bottom of a tub, feeling much smaller). This required all three of us not-particularly-burly dudes to sleep on our sides. Four days later, I attempted Cerro Torre via the 30-mile Paso Marconi approach—easier climbing, much more walking and camping—and therefore opted to bring the slightly heavier Black Diamond First Light tent, which is at least five inches wider. The width gains are theoretically small but in practice feel massive. I felt like I slept, and recovered, significantly more in the wider tent.

IV. Use your brain

Looking back, summarizing all that I learned about bivy gear last year in Patagonia, I realize that most of what I’m preaching here is common sense. Bring less. Share more. Don’t bring anything at all. But, in practice, each experiment in paring down felt like a real consequential leap—more akin to driving without a seatbelt than merely risking a speeding ticket.

The decisions one makes in Patagonia have more gravity than those in less-volatile ranges like the High Sierra, Bugaboos, or Alps. Bivy gear can act as a temporary island of safety amidst a life-threatening storm, which may roll in early or unforecasted. There is a reason that each time I planned to bivy this season I did so in a waterproof tent—not a capella.

But I don’t think the moral of this story is to “be careful.” The lesson is to truly enjoy the company of the people you’re climbing with. Because whether you’re cuddling your buddy in a sleeping bag or not sleeping at all, you’re going to get to know each other pretty well.

The post What I Learned Trying to Go “Ultralight” in Patagonia appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Op-ed: Think you can’t bear the extra weight of carrying a helmet up your project? Consider this: I am without a doubt more anal about weight than you.

The post Shaving Grams Is a Bad Excuse for Not Wearing a Helmet appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Wearing a helmet has somehow become a contentious issue in climbing. If you wear one you’re either a gumby or an old timer. If you don’t you’re a cocky idiot—at least according to any comment thread ever on Reddit/Facebook/Instagram. I belonged to the latter category up until about four years ago, when I started working at Climbing. I would frequently ditch my helmet when climbing hard sport projects. (To save weight? To leave open the possibility of an impromptu rose move? I honestly have no idea.)

But when I started writing the beloved Weekend Whipper column—and was forced to analyze clips of seemingly solid cracks explode, huge flakes rip off of well-traveled sport routes, and even pro climbers with their impeccable footwork get wrapped up in the rope and careen headfirst into stone—I realized there is a frighteningly high level of randomness in our sport. As a result, I now almost never leave the ground without wearing a helmet. I even think there’s a strong argument to be made for belaying with one.

If you think you can’t bear the extra weight of carrying a helmet up your limit project, consider this: I am without a doubt more nit-picky about weight than you. I have worn unpadded ski harnesses on redpoint attempts. I have trimmed the excess shoelace off my climbing shoes to shave grams. I frequently ask my girlfriend to cut my hair before a big alpine route. I have specific “send-day” undies that are 40 grams lighter than my daily-driver “projecting” undies. Yeah, I’m that guy.

Seriously. If I can justify the weight of a helmet, so can you.

Aside from the weight complaint, I also often hear that helmets are simply too hot or uncomfortable to wear for more than a pitch or two. Anyone with this argument is just plain lazy. There are roughly 100 climbing helmets on the market today—there is, without a doubt, at least one helmet that fits your head comfortably and has your preferred amount of ventilation. I would know. I have a giant head—so big, in fact, that most large or extra-large helmets literally do not fit over my skull. And even I found not one but two helmets which fit me perfectly and provide plenty of ventilation when climbing in the stifling 90s. Believe me, if I can do it, you can too.

The post Shaving Grams Is a Bad Excuse for Not Wearing a Helmet appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Jordan Cannon and Michael Vaill raced up 8,000 feet of Yosemite granite, with difficulties up to 5.13 and A2.

The post “It Was the Hardest Thing I Could Think Of”: Inside a Badass Ascent of the El Cap Triple appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Jordan Cannon and Michael Vaill had an absolutely marathon day of Yosemite climbing earlier this month, when they linked up three routes on El Capitan—the Salathé, Lurking Fear, and the Nose—in just 23 hours and 19 minutes. In total, the pair climbed over 8,000 feet of steep granite (roughly 80 guidebook pitches) while free climbing up to 5.13 and aiding A2.

Cannon first encountered the “El Cap Triple” in 2016. He had just staggered down from his very first El Cap route and met Brad Gobright, who’d made the second ascent of the link up with Scott Bennett. “Our route took six days and felt hard and epic,” Cannon tells Climbing. “So to meet Brad in the meadow afterward and hear his stories really left an impression on me. The El Cap Triple became the link up that I aspired to do one day. It was the biggest, hardest thing I could think of in Yosemite.”

History

Hans Florine and Steve Schnieder were the first to race up three El Cap routes in a day in 1994, via the Nose, Lurking Fear, and the West Face. But for those unfamiliar with the topography of El Cap, there is a distinction to be made between routes like the Nose and the West Face; the former is “big wall” route—graded VI for its high commitment while nearly 3,000 feet off the deck—while the latter is considered a “multi-pitch” and receives the tamer V grade due to its more modest 1,800 feet. As a result, Cannon says the 1994 link up is often considered “the birth of the idea” of the El Cap Triple. The West Face team cracked the door open for Alex Honnold and Sean Leary to burst through in 2010 and bag three VI routes—the Nose, Lurking Fear, and the Salathé in a day.

View this post on Instagram

Building up to the El Cap Triple

Cannon was inspired by his meeting with Gobright nine years ago, but he was a long way from climbing like him. He had plenty of “firsts” to complete—first Nose in a day, first Half Dome in a day—and along the way Cannon began to grow comfortable with the idea of climbing nonstop for 24 hours. “It takes a long time to build all-day fitness,” he explains, “and seeing how your body responds to going without sleep.” After completing the Yosemite Triple Crown in 2021, which ticks El Capitan, Half Dome, and Mount Watkins, Cannon turned his attention almost exclusively to El Cap. His first “El Cap Double” was in 2024. That same season he met Michael Vaill.

Vaill made waves last year when he and Tanner Wanish set a blistering speed record on the Yosemite Triple Crown before upping the ante six days later with their invention of the Yosemite Quadruple: the Triple plus the South Face of Washington Column. Cannon watched all this from a distance and took note. “I was really impressed with Mike’s ability [to move quickly] on steep C1 pitches, which was the type of partner I needed to complement my free climbing background,” he says. Cannon had spent the start of his 2025 season making the fourth free ascent of the Salathé Wall (VI 5.13b/c) before turning his attention to the El Cap Triple with Vaill. “My strategy to climb the Salathé fast was to free large portions of the harder pitches because of my familiarity with the route right now,” he explains. The strategy worked well, and included some impressive nocturnal free climbing at the very top of the Salathé Headwall, where Cannon busted out a 5.13 sequence of “tips laybacking” instead of standing on some tedious micro-nut placements.

Sending the El Cap Triple

Cannon and Vaill started their day at 8 p.m. on June 2 and blasted up the Salathé in 6:47. The ascent went smoothly, more or less, save for a short aid fall Cannon took at the start of the Salathé Headwall, while simul climbing, in the middle of the night. Aside from brief, strategic moments of simul climbing, the duo planned to mainly short-fix (a tactic where both climbers move simultaneously as rope soloists, with a knot fixed to an anchor between them), enabling the second to jumar wearing approach shoes. “When you’re linking multiple routes in a day, limiting the time spent in climbing shoes is really important,” Cannon says. “Foot pain really builds throughout the day.” Due to the team’s varied strengths, Cannon could quickly dispatch lead blocks with free sections up to 5.12, while Vaill raced up blocks of sustained aid. Cannon says Vaill taught him a lot about how to aid climb quickly. “When you’re in full aid climbing mode, it’s easy to trick yourself into thinking it’s too hard to free climb—that you need to aid climb it,” Cannon says. But Vaill intentionally practiced his lead blocks as a free climber first, to dispel any assumptions of which pitches would actually be faster to aid. “[Vaill] remembers when the first half of a C1 pitch is just 5.9 … and develops an aid sequence around that, including which cams and hooks go where, much like a free climber,” Cannon says.

At the top of the Salathé, Cannon and Vaill hiked over to the top of Lurking Fear and rappelled back to the valley floor. They had discussed walking off the East Ledges descent after each route, but figured saving their energy by rappelling would keep the day as fun as possible. They got to the base of the wall at 4:30 a.m. and spent a stressful hour and a half waiting for their friend who had promised to resupply them with food and water. The friend never arrived—they’d slept in—but another scrambled to find the team’s supplies and hike up to them. The unscheduled rest may have been a blessing in hindsight because Cannon and Vaill set their PR on Lurking Fear: 4:41.

Another rappel descent teed them up for what ultimately became the low point of their day: climbing the Nose in the full June sun. “In some ways the crux of the El Cap Triple is climbing three big routes on the same sunny aspect,” Cannon says. “At some point you’re going to have to climb in the full sun, no matter what time you start, or which order you start the routes.” Knowing they had an hour-long buffer to finish within 24 hours, the pair slowed their pace on the Nose and tried to savor the day.

How the El Cap Triple compares to the Yosemite Triple Crown

When Cannon began preparing for the El Cap Triple after doing the Yosemite Triple, he thought the former would actually be easier since there was less hiking to do. “But I quickly realized that I was totally wrong,” he says, laughing. One benefit of the Yosemite Triple is that all of its walls are facing different directions, allowing climbers to spend all day in the shade. Another benefit is that its climbing is simply easier. “Even though, on paper, the El Cap Triple is only 1,000 feet more of climbing, the climbing you have to do is much steeper and harder,” Cannon explains.

On both objectives, Cannon says he tried to operate with a wide margin of safety. “When I was younger I was more willing to accept greater risk, but now from personal experience and seeing other people take big falls my personal risk is now much lower,” he says. “But we also weren’t fooling ourselves into thinking that, since we were climbing well, we’re invincible.” He cites a pitch of the Nose called the Stove Legs, a 5.8 hand crack which he essentially free soloed—he had one quickdraw clipped to the anchor and placed no cams. It would have been a horrendous 200-foot fall if he slipped. “But the likelihood of me falling was so small it felt like an acceptable risk to me,” Cannon says. “Thanks to our preparation and familiarity of all the routes, we could really choose when to take added risks, and why.”

What’s next after the El Cap Triple?

For climbers who dream about the El Cap Triple, it’s hard to imagine going even bigger in 24 hours. For Cannon, who has focused on speed climbing and in-a-day free ascents throughout his climbing career, he’s excited to turn towards all-free speed link ups next. “I’d like to try freeing more routes in one day. The El Cap Triple is as big as it gets for speed climbing at the moment. But there’s more free link ups to be had!

The post “It Was the Hardest Thing I Could Think Of”: Inside a Badass Ascent of the El Cap Triple appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

“It doesn’t ever abate. You have to keep given’ er all day every day.”

The post Massive Southeast Pillar of Ultar Sar (7388m) Finally Climbed! appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

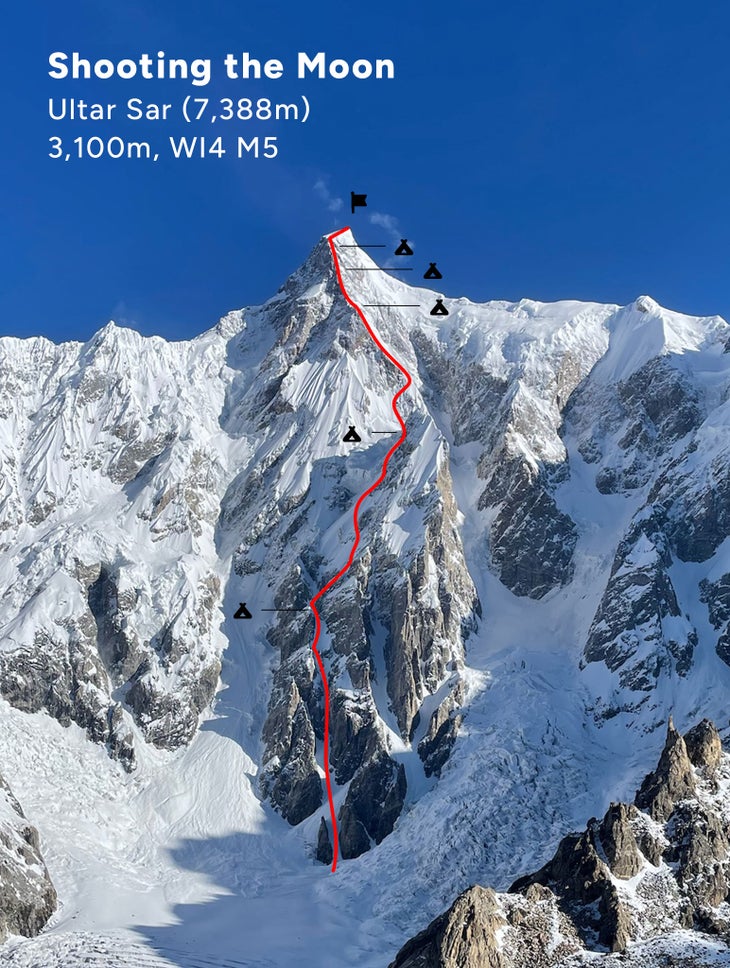

The steep upper flanks of the Southeast Pillar of Ultar Sar (7,388m/23,950ft) are a bad place to be pinned by a storm. Hemmed on either side by seracs and avalanche-prone slopes, the 3,100-meter buttress of blocky granite and glacial ice is a stressful descent even in good weather. Descending it with heavy snowfall and 50-mile-per-hour winds is unthinkable. But that’s exactly where Ethan Berman, Sebastian Pelletti, and Maarten Van Haeren found themselves on June 12 and 13, huddled beneath their homemade three-person sleeping bag, as they watched over a meter of snow accumulate against the thin yellow walls of their tent. Though they had reached the summit the day before, they were now trapped at 6,700 meters, and had been for over a day. “We weren’t celebrating the summit at that point,” Pelletti told Climbing. “You haven’t achieved anything unless you get down.”

Pelletti, Berman, and Van Haeren eventually completed the endless rappels back to basecamp (they “stopped counting” after 70) and their resultant route, Shooting the Moon (WI 4 M5; 3,100m), is an important contribution to Karakorum alpinism. For decades, Ultar Sar’s Southeast Pillar has been considered one of the most attractive and obvious unclimbed lines in the Karakorum range due to its stunning symmetry and steep, hard climbing all the way to the summit. But there’s a reason the Southeast Pillar has gone unclimbed since its first known attempt 33 years ago.

For one, it’s simply a pain to get to. Just note its alias, the “Hidden Pillar,” a nod to the rarified glances it receives from alpinists despite the enormous foot traffic elsewhere in the Karakorum. It’s also giant. After visiting the mountain in 2007, Colin Haley wrote in Climbing: “[The Hidden Pillar] makes the North Ridge of Latok 1 look small by comparison, and, while not as technical, it is still sustained, real climbing—very little simple slogging.” And then there’s the mountain’s remarkably unstable weather. Even though this team departed basecamp at the start of a “seven-day” weather window, they experienced high winds and snowfall nearly every afternoon. Ultar Sar has its own rhythm.

Pelletti, Berman, and Van Haeren first tried the Southeast Pillar in 2024. They made three attempts, their best to 5,900 meters, before bailing amidst unstable snow. “Each time we pushed a bit higher, as we learned to survive and thrive in the most complex environment I have ever experienced,” Berman later wrote. “Safety became a matter of position, not proximity. It was difficult to comprehend the scale of the terrain we were immersed in, and rewarding to unlock each piece of the puzzle.” During that trip, the trio learned the value of climbing at night on the Southeast Pillar. Even during periods of purportedly good weather, the route became barrelled by wind and snow each afternoon.

This season, when the trio hiked away from basecamp on June 6, they felt fit, acclimated, and mentally ready. They had trained specifically for Ultar Sar for the previous eight months, refining their climbing tactics and sleeping system like students preparing for an exam. For Berman, who received shoulder surgery immediately after returning from Pakistan last year, Ultar Sar had become a guiding force in his life. “It was so rewarding,” he says of returning to the mountain with all of last year’s lessons under their belt. “We could really go for it.”

The first two days on the Southeast Pillar were big. The team climbed 800 meters of technical ice and snow on day one, then 750 more on day two. Their blistering pace wasn’t so much out of enthusiasm as out of necessity. The mountain was unrelentingly steep; they were simply climbing from flat campsite to campsite. When they reached the upper pillar’s headwall, their pace eased. “We weren’t too affected by the altitude, but we noticed we slowed down a lot,” Pelletti says. “It took longer to leave the tent every morning, longer to climb crux pitches, and longer to recover from them.” Thankfully the climbing, at least, was all time: “Incredibly good granite and ice in all the right places.” The team climbed four distinct crux pitches at around M5 and eventually summited after six days on the mountain.

Berman says the team found success on Ultar Sar because they merged into one cohesive unit immediately upon crossing the bergschrund. “We didn’t see tasks as ‘your job’ versus ‘my job’—they were all team jobs and everyone was eager to do their part,” he says.

This crew gets along well together. Van Haeren audibly blushes when Pelletti praises him as “a fucking weapon” over the phone. And “[Berman] is cool, calm, and collected in the face of tough times,” Van Haeren says. “[He] really kept his head screwed on while pinned by the storm, when we were so far out there.” Pelletti—who became “Sergeant Seba” while on the mountain—was credited with having bottomless motivation even when the team was exhausted from another hard day of climbing. “Seba would sometimes yell at the stove for not boiling water fast enough,” Berman laughs. “And he encouraged us to always set the alarm one hour earlier in the morning. Less sleep, more climbing.”

The post Massive Southeast Pillar of Ultar Sar (7388m) Finally Climbed! appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

It was the culmination of a truly historic trip to the range.

The post Interview: Balin Miller’s Bold Solo of 9,000-foot ‘Slovak Direct,’ Denali appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Balin Miller spent 53 days on Alaskan glaciers this spring. And though he jokingly called the barren terrain a “hellscape” in hindsight, it also enabled an alpine-climbing season few could even dream of. The 23-year-old from Anchorage wrapped up his tenure just a few days ago, after making a historic solo ascent of the Slovak Direct (M6 WI 6 A2; 9,000ft) on Denali (20,310ft/ 6,190m) over three days.

Miller has known about the Slovak for most of his life. When the route was climbed in a single 60-hour push—no tent, sleeping bags, or enough equipment to bail from up high—by Steve House, Scott Backes, and Mark Twight in 2000, their ascent marked a new era of North American alpinism: A giant, steep face was climbed via the same lightweight means one might approach a multi-pitch in Yosemite.

“I definitely thought of it as being super duper hard,” Miller says. But when two separate parties climbed the face in under 24 hours in 2022, his perception of the route began to change. Matt Cornell, whose team dispatched the Slovak in 21 hours and 35 minutes, described it as “super chill,” with plenty of low-angle snow that could be climbed quickly. “I realized it was still hard, but it’s not, like, 6,000 feet of technical climbing,” Miller says. “The more I thought about it, the more I thought it would be a ton of fun to climb alone.”

“That said, while I liked the idea of soloing it, I definitely didn’t have to,” Miller notes. “If I’d had a partner I was getting along well with, who was also psyched, I would have done it with them in a heartbeat.”

On June 10, Miller skied away from his basecamp and gained 4,500 feet of elevation over 10 miles en route to Denali’s South Face. Cornell had warned him the heavily crevassed approach might be the scariest part of the whole endeavor, but thankfully a thick snowpack had formed secure snow bridges over the gaping cracks. Miller was intimidated on the ski in, but also comfortable in the landscape. He’d been in the area for over a month and a half by this point. “You definitely get desensitized out there on Denali—the scale is so big, it’s hard to really comprehend.”

The most impressive part about Miller’s ascent is how much he slept on route. He woke up at 9:30 a.m. on his first day, left camp two hours later, and climbed for just four hours before stopping to bivy at a prominent hanging glacier. He then hung out there for 19 hours. “I think I was just tired from the approach,” he explains. “I figured I would take a half rest day and sleep in. Normally you don’t have the luxury to do that. But I did have five days of good weather, so there was no rush.”

Miller expected to self-belay as many as six pitches with his rack, half rope, and Grigri, but Cornell assured him he’d only need to belay one—if he was comfortable free soloing up to M5/6 and WI 6, which he was. The route ended up being even easier than he dared to dream, and its fearsome reputation became less and less important the more he saw it for himself. “It’s not pumpy, sustained M5,” Miller notes. “It’s more like romping up M3/4 with a move of M5/6. And you’re not hanging off your arms, scratching around. You just need to do, like, a high foot and make a weird move.”

He found solid granite and stable snow low on the route, and then “sticky, fun ice” through the ice-crux corner system. Even the WI 6 pitches—labeled as “100 degrees” on the topo he’d been given—were only that steep for 20-40 feet and interspersed with lower-angle ice. “I was hoping for a [natural] ledge to set my pack on partway through the ice pitches, so I could haul my pack through them, but I didn’t see one and didn’t want to chop a ledge. So I soloed all the ice pitches with my pack on which definitely made the climbing feel harder,” he says. Despite the steep, physical free soloing, Miller describes his scariest moment as traversing a 5.6 slab that was covered in snow. He swung his axes into featureless rock numerous times before finding enough little edges to eventually connect to more secure terrain.

The one pitch Miller expected to rope up for was the technical crux of the Slovak: a series of steep A2 cracks that had been freed at M8. “It felt a little ridiculous to bring so many cams and a rope for just one pitch of aiding, but I was glad I had everything,” he says. “I might have been the first person to bring a Grigri up Denali!”

Above the crux headwall, Miller climbed one final pitch of M4 before connecting with the upper snow slopes of the Cassin Ridge and stopping for the night. “I was feeling the altitude at this point and I threw up a little bit. I bivied at 1 a.m. and started moving around noon the next day. Thankfully there was no more climbing, just snow, so I slowly hiked to the summit over seven hours. I ran into a friend who let me have some of his dinner at 14 camp, and then around midnight I left and walked all the way down to base camp. I got back at 4 a.m.”

Talking about the Slovak with Miller is remarkably underwhelming. I’ve had similarly subdued conversations with family members about their home reno projects, or manual labor. Yeah, hard work, but not too bad. I’m happy the Slovak was so firmly within Miller’s wheelhouse, but I also wanted some wider perspective. Colin Haley, a veteran of the Alaska range who has soloed both the Cassin Ridge and the Infinite Spur in record time, told me: “I think that Balin’s solo ascent of the Slovak route is very impressive, and the fact that he did it shortly after his solo ascent of the French Connection [M6 AI 6; 6,500ft] on the North Buttress of Begguya makes for a super badass, and I would even maybe say historic, trip to the Kahiltna.” Haley said Miller’s ascent of the Slovak is one of the greatest alpine-style solos ever done in the Central Alaska Range, second only to Renato Casarotto’s committing voyage up the Ridge of No Return on Denali in 1984.

And when Mark Twight—of that visionary 60-hour Slovak blitz—first heard about Miller’s solo, his first reaction was: “Holy shit.” Then: “Of course he did.” After all, the Slovak represented a logical progression from Miller’s free solo of the French Connection at the end of May. (At the time, Haley described that solo as one of the most impressive alpine-style solos ever done in the range.)

The French Connection climbs the long ice runnel—up to AI 6—of the French Route on Begguya (14,573ft/ 4,442m), also called Mount Hunter, before traversing hard right into the final pitches (M6) of the Bibler-Klewin. The crux of the route came at the very top of the North Buttress at “a section of slightly overhanging ice in a crack,” Miller describes. “It’s not super difficult, but it’s really awkward because the crack is narrow and steep. It’s hard to get your tools in there.” Although many parties stop at the top of the 4,000-foot North Buttress and begin rappelling, Miller continued up the extra 2,500 feet of snow and alpine ice to the summit, returning to camp in roughly 17.5 hours. (Of note: earlier this spring, with partners, Miller also climbed Deprivation (AI 6 M6; 6,500ft) on the North Buttress to the prominent “third ice band” and then returned two weeks later to take it to the summit.

Looking back at his nearly two months in the Central Alaska Range, Miller said he is happy with how much climbing he got to do, but is also looking forward to summer. “It was a very social season,” he says. “Despite all the soloing I was doing I was mainly hanging out with friends in base camp, and I had a lot of fun climbing with new partners on Hunter. There were only a few days I felt lonely out there, and those days were spread out between a lot of fun ones. Overall, it was a really special time.”

The post Interview: Balin Miller’s Bold Solo of 9,000-foot ‘Slovak Direct,’ Denali appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

The 20-year-old New Yorker just made climbing history.

The post “I Wanted a Fight”: Will Moss Becomes First Person to Flash El Cap in a Day appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Will Moss had one of the best days of climbing in American history on Tuesday, when he tied in at the base of El Capitan’s Free Rider (5.13a; 3,000ft) at 5 a.m. and topped out a little over 22 hours later. It was his first time on the route. He didn’t fall once.

The last time I spoke with Moss was in 2023, right after he’d put up one of the world’s hardest trad routes, Best Things in Life Are Free (5.14d R), on the Twilight Zone Buttress in the Shawangunks, NY. The former comp climber had begun trad climbing a mere three years prior, but quickly realized that the steep, pumpy roofs of the Gunks lent themselves to his sport climbing background. Evidently, he was also mentally strong enough to commit to feet-first V11+ boulder problems with ugly fall potential.

Moss moved to Boulder, Colorado, at the end of that year for a mechanical engineering degree and almost immediately went on a trad climbing tear. He quickly ticked the second ascent of Viceroy (5.14b R), lead rope-soloed China Doll (5.14a R), and sent both Cheating Reality (5.14a R) and Kill Switch (5.14a).

The whole time, Moss held a greater goal front of mind: flashing a route on El Cap. It was an audacious goal—Babsi Zangerl had yet to become the first person to flash El Cap via Free Rider—but he felt certain the route would suit him well. Moss traveled to Yosemite in early 2023 with his dad to try the flash, but the route was soaking wet. The next year, partners and weather never quite lined up.

While Moss’s main goal still eluded him by the end of his second Yosemite season, he’d still sent a number of routes that boosted his confidence on the Valley’s notoriously techy stone: Wet Lycra Nightmare (5.13d; 9 pitches), Final Frontier (5.13b; 9 pitches), Nexus (5.13a/b; 10 pitches), Dream Team (5.13a; 10 pitches) onsight, Romulan Warbird (5.12c; 9 pitches) flash, Mahtah (5.12d; 16 pitches) onsight, and The Phoenix (5.13a).

Finally, this spring, after waiting for the right moment, Moss blasted off. I caught up with him the day he got down, while he was still recovering by the Merced River.

Interview

Climbing: You have been talking privately about wanting to flash El Cap for over two years now. How has that goal evolved?

Will Moss: I first came out to Yosemite to try to flash Free Rider two years ago with my dad. But the route ended up being totally soaked so we didn’t go for it. But I’m honestly happy we didn’t because I don’t think me or my dad were really prepared for it—we didn’t really know how to haul, and it might have been a little disastrous.

But I had done a lot of studying to prep for the route. I had all the Free Rider media I could find in an album on my phone, in order from the ground up, and I knew all this info wasn’t going to go to waste. So I came back the next year with a friend, but partners, weather, and being psyched never really lined up, and I knew I didn’t want to waste my only flash go when the weather was too warm.

Both of those years, had I done it, I would have been the first person to flash El Cap. Soon after, Babsi Zangerl flashed it, so then I had the idea that I wanted to do something even cooler, something that had never been done. Like flashing it while leading every pitch in a day.

Even so, when I finally went for it this year, we actually had supplies for three days with us. (Editor’s note: Moss and his partner pre-hauled to Heart Ledge; though Moss stopped short of the actual Heart Ledge in order to not stand on it.) I was very much 50-50. And it’s sort of a hard decision to make on Heart Ledge—you’re only on pitch 10, so it’s pretty easy to think, “Oh, I feel great!” But in two pitches, maybe you won’t be feeling that great.

But when I got to Heart Ledge I was feeling psyched, so I said, “Fuck it. Let’s go for it in a day.” And I’m so, so happy I made that decision.

Climbing: It’s cool to hear how your goal of the El Cap flash changed after Babsi did it last year, that her flash made you want to up the ante. I’m curious why you thought you could flash it in a day. It takes a lot of confidence to even dream that.

Moss: I think the route just seemed like my style. I’m 6’1” with a 6’5” wingspan, and it seemed like the Boulder Problem (5.13a) is really good for tall people. I’ve also done a lot of offwidthing, and it seems like most people who go up there find the Monster (5.11a) pretty hard. I’m also a decent slab climber. In a way, knowing that I had the flash goal two years ago, and seeing how I’ve progressed since then, was really encouraging. I’ve become a much better all-around rock climber since then.

I also knew that if I gave a flash attempt over multiple days, I’d still want to come back to free the route in a day. I kind of wanted to skip all that and do it all in a day. It was definitely a little risky to go for the flash in a day because there are so many things that could go wrong—I was on the Enduro Corner (5.12d) at night which was one of the hardest pitches for me—but I wanted a fight.

Climbing: Aside from the Enduro Corner, were there any other hairy moments?

Moss: The Freeblast slabs (5.11) were pretty hard. I took like 25 minutes on one pitch I think. After that, everything up to the Alcove felt really good. I felt pretty dialed on the Boulder Problem and did basically the beta I had envisioned I would do, except for one foothold I had to change on the fly. The karate kick felt really good to me.

Honestly, I really underestimated the first pitch of the Enduro Corner—I just thought I would do it easily. And it ended up being super weird and hard pin scars and I wasn’t expecting that at all. Especially because it was in the middle of the night. I also think I accidentally had my headlamp on the lowest setting. But I never felt too close to falling—it felt pretty secure.

Climbing: That’s what is so interesting about these big, more endurance-based objectives: at a crag, flashing any of those pitches is not particularly noteworthy. But it is noteworthy on El Cap, when the fatigue builds pitch after pitch, physically and mentally, and it can be difficult to not get inside your own head or make those simple mistakes.

Moss: Yeah. There’s 3,000 feet to fall on. I was pretty nervous the whole time. It’s been the main objective of my climbing life for the last two years. But more than anything, I knew I wanted to experience this epic 24-hour thing. I’d never experienced such a long day like that before.

Climbing: How long did the whole day take you?

Moss: From starting up the first pitch to my partner jumaring the last pitch, it was 22 hours, 16 minutes, and 34 seconds.

Climbing: I know it’s been less than 24 hours since you’ve come off of the wall, but do you already have ideas for the future?

Moss: Oh, there’s so much more climbing to do. And I’m just so happy. It was literally the most fun I’ve ever had while climbing: flashing 3,000 feet of rock. It felt like I’d been up there before because I’d studied it so much.

I also just love climbing in Yosemite and I have two more weeks out here, plus I’m taking next semester off school to climb here more. Up until now, I’ve done lots of flash goals because I’m a full-time student, not a professional climber. The really hard climbs on El Cap are cool but hard to fit into a school schedule because you’ve got to rap in and work it a bunch, which takes a lot of time. But the flash and onsight goals don’t take that much time. You just show up and do them. And I can train for them at home. But mainly I’m excited to not have any homework for nine months.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

The post “I Wanted a Fight”: Will Moss Becomes First Person to Flash El Cap in a Day appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Ondra once again proved he’s still the best all-around rock climber alive.

The post Adam Ondra Just Did the Hardest Trad Flash of All Time—5.14 R appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

The man who brought you the world’s first 5.15c and 5.15d, the first flash of a 5.15a, a blistering free ascent of the Dawn Wall, and countless ear-splitting power screams, Adam Ondra, has defied expectations once again. He just flashed the fearsome U.K. trad route Lexicon—a 5.14 R with 80-foot fall potential. (And, yes, the runout is at the crux.)

Lexicon (E11 7a) was first established in 2021 by the legendary all-arounder Neil Gresham, who had to level up nearly every aspect of his life, including his ballet performance, in order to send. At the time, he compared Lexicon to the trad-climbing equivalent of an Olympic gold. “I wasn’t going to achieve it with the approach of a keen amateur,” he said. “I would need to give everything.”

Soon after Gresham sent, a Who’s Who of cutting-edge trad climbers flocked to the Pavey Ark crag to have a go. Steve McClure, in his classic shoes-untied, laissez-faire style, quickly began giving redpoint attempts. He hadn’t dialed the route nearly as much as Gresham, but figured the nest of gear at two-thirds height would keep him off the deck should he fall from the top of the pitch.

McClure’s subsequent 60-foot whipper—caught by Gresham just barely off the deck—instantly became the stuff of lore among core trad climbers.

All this background makes Ondra’s flash attempt even more impressive. Ondra watched that whipper. He understood it was a fall that resulted from a glassy foot slip, and one which, theoretically, any talented climber could also take. He also understood there was still another three feet of very hard climbing above where McClure pitched off. He knew the margin of error on those crux 5.14 moves was basically zero.

Even so, Ondra couldn’t resist. He warmed up on sections of the neighboring routes at the crag, making sure to not look at any of Lexicon’s crux grips. Sure, he’d watched beta videos of others climbing it, and the holds had been freshly brushed and ticked for him, but he wanted to find some balance between non-lethal recreation and a proper adventure.

“After that, I racked up on the top ledge and speed-rappeled down along Lexicon, facing the lake so I would not get any view of the holds at all,” he wrote.

Warm, racked up, and ready, Ondra got a reassuring fist bump from Gresham and started up the route. “I got scared, I tried hard, my heart was beating, but I made it to the final ledge without testing that massive whipper,” he said.

Bravo, Adam. That was badass.

The post Adam Ondra Just Did the Hardest Trad Flash of All Time—5.14 R appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Whether you’re a cragger, alpinist, or office-to-gym rat, we’ve got you covered.

The post The 5 Best Climbing Backpacks and Kitbags of 2025 appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Backpacks are one of climbing’s broadest gear categories, serving everyone from casual craggers and gym-goers to fast-and-light alpinists and multi-day big-wallers. Unlike harnesses and helmets, most of which are versatile enough to wear anywhere, each climbing backpack comes with a unique set of features—and is intended for a specific use case.

Over the course of five years, we’ve tested more than 30 climbing backpacks and taken diligent field-testing notes on each model’s comfort, design, durability, and feature-set. To be clear: This is not a story about the “best new backpacks for 2025.” These are the best backpacks you can currently buy. Full stop.

At a Glance

- Best for Cragging: Black Diamond Creek 50L ($220)

- Best for Alpinism: Patagonia Ascensionist 35L ($229)

- Best for Multi-pitch: Mountain Equipment Orcus 28+ ($155)

- Best for Multi-day Objectives: Osprey Mutant 52L ($230)

- Best for Travel: Rab Expedition II 80L Kitbag ($145)

- Other Climbing Backpacks We Like

- How to Choose a Climbing Pack

- How We Test Climbing Packs

- Meet Our Testers

Don’t miss: The Best Climbing Shoes of 2025

Best for Cragging

Black Diamond Creek 50L

$220 at Backcountry $240 at Black Diamond

Weight: 4.4 lbs (S–M)

Volume: 50L (S–M)

Size: S–M, M–L (unisex)

Pros and Cons

⊕ Comfortable carry

⊕ Many organizer pockets

⊕ Full side-zip

⊗ Quite heavy

Rock up to any busy North American crag and we’ll all but guarantee there’s a Creek 50 or two parked at its base. There’s good reason: BD’s flagship cragging pack is built to last, and its thoughtfully placed pockets will spare you the yard sale beneath the proj.