Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

Big-wall history was made when Siebe Vanhee, Sean Villanueva-O’Driscoll, Nicolas Favresse, and Drew Smith topped out Riders on the Storm on Torre Central, in Torres del Paine National Park, after a team-free ascent last week.

Over 18 days, the foursome battled 80-mile-per-hour winds, multiple snow squalls, ice-filled cracks, plenty of rockfall, and a boring storm-bound week in their portaledges. They also experienced some of the finest big-wall free climbing of their lives.

History of Riders on the Storm

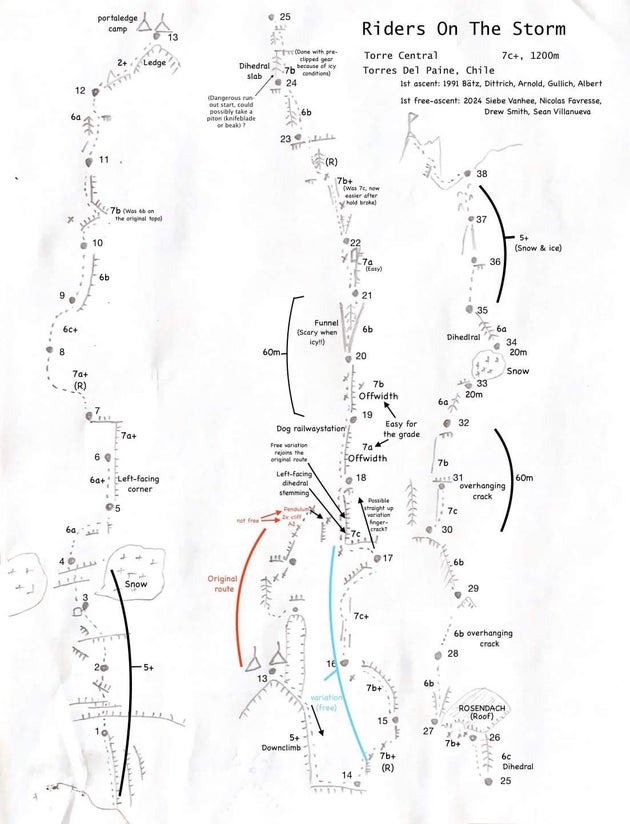

Riders on the Storm was established in January 1991 by a legendary German team of Kurt Albert, Wolfgang Güllich, Bernd Arnold, Nobert Bätz, and Peter Dittrich. Their ascent prioritized free climbing as much as possible, and over a six-week period of largely stormy weather they breached the 1,200-meter East Face at 5.12d and A3. Another 100 meters of mild mountain rambling lead to Torre Central’s summit. The Germans spoke highly of Riders on the Storm. They promised impeccable rock quality, splitter cracks, and fantastic exposure high on the wall. The route largely went (or would go) free, except for a steep and utterly blank slab they crossed via an aid pendulum.

In 2006, up-and-coming Belgian superstars Villanueva-O’Driscoll and Favresse flew to Chile to try the route. Being in their 20s and from a country not particularly known for its mountains, neither had much alpine experience, but they were strong big-wall free climbers, and they summited Riders on the Storm after freeing 90 percent of the route.

Mayan Smith-Gobat became the route’s custodian of sorts a decade later. In 2016, she, Ines Papert, and Thomas Senf pioneered a five-pitch free variation to avoid the blank pendulum above pitch 13 and excitedly opened terrain up to 5.13a. The free route was unlocked! They opted to tag the summit before freeing the remaining pitches, but on the descent they were peppered by rock and ice fall—and yet more poor weather—which ended their expedition and Papert’s willingness to return to the route for a free attempt. (After nearly being killed when a rock ripped through her portaledge fly, she decided the wall had too much objective hazard.) Smith-Gobat called up Brette Harrington and Drew Smith the next year, but they spent a frustrating six weeks sitting out storms and battling up snow-choked cracks. The free variation sat in wait.

The free ascent

Siebe Vanhee first climbed in Torres del Paine with Villanueva-O’Driscoll and Favresse in 2017, when they freed El Regalo de Mwono (VI 5.10 A4) on the Central Tower at 5.13b. Vanhee returned in 2022 to attempt Riders with Brette Harrington and Jacopo Larcher, but the five-week trip was again plagued by poor weather, and the team never truly got a chance to try the whole route. When Harrington and Larcher were pre-booked this winter, Vanhee texted his old friends with a simple query: “I want to try to free Riders, are you psyched for another sufferfest?”

Smith-Gobat’s free variation, which loops around the pitch-14 pendulum, begins with a right-trending 5.10 downclimb and then two pitches of 5.12c—the first of which is quite runout. The 5.13a crux, pitch 17, consists of two steep, parallel cracks culminating in an airy roof pull. Smith-Gobat had placed “many” bolts on rappel on this pitch, not all of which were necessary. “The pitch would go without any bolts at all,” Vanhee told Climbing. “But it would definitely be bold and it would make the pitch much harder.” Vanhee continued: “But the bolting is also in character with the rest of the wall. In general the route protects quite well. [The first ascent team] had the habit of adding many bolts to his routes, even beside easily protected cracks, especially the offwidths.” Future suitors should note that the free route is no clip-up; according to the topo, there are three R-rated 5.12 pitches.

Why did Riders take so long to free?

At 5.13a, Riders on the Storm is far from a cutting-edge big wall. So why did it take so long to receive a free ascent?

“It’s tough to find reasonable climbing conditions on that wall,” Vanhee explained. “The rock needs to be warm and dry of water and snow, and then you need a window where you can actually climb on it.” One time, as Vanhee prepared to lead the crux pitch, the wind picked up so ferociously that his belayer couldn’t even pay out slack. The wind tossed the ropes in the air repeatedly, and it took them an entire hour to detangle them. Vanhee said that climbing this route was frustrating, in a way, because everyone on the team could climb pitches of this grade. “But it felt like a 5.14 effort.”

View this post on Instagram

They spent 18 days on the wall, but only nine were spent climbing. By day six, they were camped below pitch 27—two-thirds of the way up the route, the crux behind them—when a nine-day storm pinned them down. Winds exceeded 80 miles per hour (140 km), and over a meter of snow fell on their portaledge camp. “Most days on the wall were spent reading, playing music, and eating popcorn…” Favresse wrote on Instagram. “The only days we could climb, we had to clean ice from the holds and fight with cold fingers and toes to free climb in sub-zero temperatures.” Drew Smith, the photographer on the trip, wrote: “These guys spoke about having lots of luck, but I don’t think we had much or any. … The summit was reached far before we stood on top because of the positive energy of the team. … Every little sliver of marginal weather was taken advantage of. Nico encouraged us ‘it doesn’t matter if we get wet the first or last day,’ Sean would always say ‘the summit is inside of us!’”

“I think our team is exceptional because we were not scared of being shut down,” Vanhee said. “One day, we jugged 10 pitches to try a section. I had my shoes on for five minutes, and then more weather came in and we went down. Throughout the climb we said: ‘Let’s get wet anyway. Let’s go into the storm anyway.’ And sometimes the storm didn’t come. That’s the key to succeeding in those conditions.”