After climbing the 8,163-meter Manaslu, Carlos Soria shares his advice on training, seeking summits, and accepting change.

The post An 86-Year-Old Just Became Oldest to Summit One of the World’s Highest Peaks appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

For Carlos Soria Fontán, Manaslu is an old friend.

Early on the morning of September 26, the 86-year-old Spanish alpinist trudged to the top of the 8,163-meter (26,782-foot) mountain, making history as the oldest person to ever reach the top of a peak over 8,000 meters. He was accompanied by longtime photographer and close friend Luis Miguel López Soriano, and Sherpas Mikel, Nima, and Phurba.

It was a poignant moment for Soria, and not just because of the record. He has a longer relationship with this mountain than perhaps any climber alive today. He first reached Manaslu’s summit in 2010 at 71, but he was also a member of the very first Spanish expeditions to the peak, in 1973 and 1975. But Soria didn’t touch the summit on those trips. The first expedition turned back due to bad weather. On the second, he acted as a designated rope fixer.

Last week, Soria and his team summited Manaslu relatively quickly, and without any major hurdles. After their final acclimatization rotation, they pushed from basecamp to summit in just three days. But on the steep, icy descent to Camp III, the climb took a turn for the worse. Soria’s legs have been a weak point in recent years—he underwent a knee replacement in 2018 and severely broke his leg on Dhaulagiri in 2023. By the time he reached Camp III, he was in severe pain, and his balance and coordination were suffering as a result.

Ultimately, he opted for a helicopter evacuation to basecamp to ensure his injuries didn’t worsen.“If I tried to come down walking, I could cause everyone else problems,” he said. “Carlos wanted to keep himself safe, but also to keep the rest of us safe, everyone else in his team,” his photographer Soriano added.

With Soria’s summit, he broke Yuichi Miura’s world record for oldest person to stand atop one of the planet’s 14 8,000-plus-meter peaks by six years of age. The Japanese alpinist summited Everest at age 80 on May 23, 2013.

“I feel good up there”

Climbing an 8,000-meter peak, in any decade of life, is an impressive feat, but Carlos Soria has now summited a dozen of the world’s 14 highest summits, most of them in his 60s, 70s, and 80s. He is the only person, in fact, to climb 10 8,000-meter peaks after the age of 60.

It begs the question: Why?

At an age when most individuals are bouncing grandkids on their knees—if their knees even function—Soria returns, time and time again, to the most inhospitable regions on Earth, to test himself.

“I do not care about records,” he told me. “I am not looking to be ‘the best.’” He also does not seem particularly concerned with the usual Himalayan mountaineering shenanigans, like sponsorships and motivational speaking tours. In recent years, he has self-financed many of his expeditions. Instead, he is simply drawn to climb. “The mountains are the place I want to be,” he said. “I always want to come back.”

Soria began finding solace in the mountains as a child. He was born in Avilá, Spain in 1939. It was a rather inauspicious year—the last of the Spanish Civil War, and first of brutal dictator Francisco Franco’s 36-year rule. “It was a very difficult time to be in Spain,” he told me. “My family was poor. We didn’t have hot water, we rarely had electricity.”

At age 14, Soria began climbing, exploring the Sierra de Guadarrama range just outside Madrid. “In the mountains, in nature, I found a way to escape that life, to find beauty again,” he said. “That’s why I’ve kept coming back. I felt good there at 14, and I feel good there at 86.”

At 86, maintaining one’s health is an uphill battle. But Soria’s regime is not dissimilar to that of any other climber. He doesn’t touch alcohol or tobacco, and he’s a clean eater. He also spends every morning working out, seven days a week. But the trick, he said, isn’t checking all these boxes. It’s to enjoy the training as much as the climbing. “I really like training,” he told me. “I train when I have expeditions coming, and I train when I don’t. It doesn’t matter.” In recent years, he’s become a fan of indoor rock climbing, too. At 7:00 a.m., almost every day, Soria can be found roped up at a climbing gym near his house.

Everything in the mountains is harder at his age. His mobility, balance, strength, and stamina are all waning. It’s harder for him to catch his breath, harder for him to get food down. His list of old injuries has only grown as the years have gone on. Soria’s approach is to take things slow, and to err on the side of caution. When I asked him what was going through his mind when he took those final steps up to the summit of Manaslu, he answered simply: “I was focused on reaching the summit.”

And what was he thinking when he was finally up there, standing on one of the world’s highest mountains, the oldest person ever to climb an 8,000-meter peak?

“I was thinking about coming down safely,” he said. “I was happy, yes. But I wanted to make sure my team and I got down without problems.”

“If we didn’t change, we wouldn’t be alive”

The only 8,000-meter peaks Soria has yet to summit are Dhaulagiri and Shishapangma, but not for lack of trying. Soria has retreated from Nepal’s Dhaulagiri a staggering 14 times. It’s also where he broke his leg in 2023—though the injury resulted not from his own mistake, but from a Sherpa slipping and falling into him. “Dhaulagiri is not the most difficult, but the weather is unstable, and hard to predict,” he said. “Storms come fast from the valley.” Soria also lost a close friend on the mountain during one of his earliest attempts. Since then, has been extremely cautious in his approach. “I have a lot of respect for that mountain,” he said.

Perhaps no one is better positioned to bemoan the commercialization of high-altitude mountaineering than Carlos Soria. In his early days an alpinist, 8,000-meter peaks represented isolated, remote objectives—true wilderness. Back then, a single team coming together to put a pair of climbers on a summit incited national celebration. Within his lifetime, many of these peaks have become jam-packed thoroughfares. Hundreds of guided climbers may tick a summit in the space of a few days.

“We were totally alone in those times,” Soria said of his trips to Manaslu in the 1970s. “It was very different. We were the only expedition on the mountain. From the gear and apparel we used, to the style in which we approached the mountains, many things have changed today.”

But Soria says he isn’t nostalgic for years past, and he won’t speak ill of mountaineering, then or now. “Things have to change in this world,” he told me. “We cannot worry or be sad. Change is life.”

Many good changes have materialized, too, as Soria sees it. More young people are coming to the mountains, more women, more people of different ethnic backgrounds. “I don’t think the past is better, or worse,” he explained. “I am happy. I like to change with the times. If things didn’t change, if we didn’t change, then we would not be alive.”

In photographs, Soria often wears a wry, knowing smile, as though he harbors some hidden wisdom, some eternal secret, that the rest of us can’t quite seem to figure out. Wondering if I could chip out some of that secret, I asked for his most important piece of advice for anyone who dreams of climbing 8,000-meter peaks. Soria was clear. It’s not training hard or gaining experience. Those things are necessary, but they come later. First, “You have to love it,” he said. “You have to love climbing.”

You can’t be up there for the social media posts or the records or the sponsors. You can’t be up there for the feeling you get when you’re back at home, bragging to your friends at the bar. “If you love it, then you will naturally do it right,” Soria said. “You will train, you will acquire the necessary experience, because you love it. And then, if climbing 8,000 meters is your dream, you can achieve it.”

About the photographer: Luis Miguel López Soriano, who accompanied Soria on his climb, is a Spanish videographer and photographer who has climbed several of the world’s 8,000-meter peaks. Follow along @luis_m_soriano

The post An 86-Year-Old Just Became Oldest to Summit One of the World’s Highest Peaks appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Both parties were on the non-technical Clear Creek route. We spoke with the local sheriff’s office and Shasta’s lead climbing ranger to find out what happened, and why.

The post Two Climbers Died on Mt. Shasta’s Easiest Route. What Went Wrong? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Two fatal falls occurred on California’s Mt. Shasta (14,179ft) in the past month, both on the mountain’s “easiest” late-season route, Clear Creek.

At first glance, the deaths are surprising. By September, the ultra-prominent volcano is largely free of snow, often rendering the Clear Creek route a non-technical hike. “It’s a slog of a scree slope,” said Sage Milestone of the Siskiyou County Sheriff’s Office.

Yet Milestone and the peak’s lead climbing ranger, Nick Meyers of the U.S. Forest Service, told Climbing that the deaths highlight a stark reality. Even on an “easy” route, poor decision-making can compound into serious accidents, and even death.

Uncontrolled glissade leads to fatal slide

The most recent death occurred on September 12. Argentinian and 45-year-old Silicon Valley executive Matías Travizano was descending from the mountain when he wandered off route, according to Milestone. Although Travizano had arrived at the mountain alone, he linked up with two other men hiking at the same pace, and the trio summited together. Travizano and one other man began to hike down slightly ahead of the third, who later reported the accident.

Clouds had socked in the peak and visibility was poor. As the men descended from the main summit plateau, all three veered off-route to the east. “It’s pretty steep, and it’s all scree, so it’s easy to lose the trail, particularly with bad visibility,” Milestone said. She added that no clear landmarks exist to identify the way down. The party realized they were off route when, at around 13,500 feet, they reached a perennial snowfield, near the uppermost tip of the Wintun Glacier.

The men were hiking without crampons, ice axes, Microspikes, or other traction equipment for traveling across snow and ice. But instead of hiking to regain the correct, snow-free route, they decided to glissade down the snow and ice to save time. “They didn’t want to climb back up and regain a bunch of elevation,” Milestone explained. But jagged, exposed rock littered the snowfield, and it was incredibly icy due to the low temperatures. “It was a very bad time to glissade,” Milestone said. Chiefly, without ice axes, the men had no way to control their slide or self-arrest.

Soon after beginning to slide, Travizano lost control and gained speed rapidly. After plummeting down the slope around 300 feet, he collided with a large rock, knocking himself unconscious. Witnessing this, the second climber spent a few minutes trying to pick his way down the icy slope to reach Travizano and render aid.

He came close. But when he was roughly 80 feet up slope from Travizano, the man “regained consciousness, tried to stand up, and just fell,” Milestone explained. The 45-year-old continued to slide at an increasing rate of speed, down into gloom and out of sight.

At this point, it also dawned on the climber who saw Travizano fall that he was stranded on the same icy slope, and afraid to move. “He couldn’t get off, and he was having a really hard time self-rescuing from that position,” Milestone said. The third climber, who had descended more slowly from above, was the most experienced in the party, according to Milestone, and was able to coach this man off the steep slope. The two later regained the trail using a GPS device and called in the accident. Travizano’s lifeless body was located by 6:45 p.m., some 2,000 feet below, according to Milestone. His body was not recovered until the following day, however, due to storms and increasingly poor visibility.

Travizano, was a native of Argentina, but lived in the United States in recent years. He was the founder and former CEO of GranData—a Silicon Valley startup dedicated to data analysis and developing new forms of artificial intelligence—which he sold last year. “He had been on Aconcagua and a few other South American mountains,” Milestone said. “This was definitely not his first mountaineering expedition, but it was his first time on Mount Shasta.” A friend of Travizano’s remembered him as a brilliant mentor, “a special human being,” and a “great leader” with a love of nature. He is survived by his wife and son.

Two men split up to find their camp, only one makes it back

This season’s second fatality on Mt. Shasta occurred just a month earlier, on August 16, on the same route. A pair of climbers had summited via Clear Creek, also during a stormy period and without wet weather gear. As they descended to their camp, they became lost. It was their first time on the mountain. “They got on the wrong ridge, took it down to like 11,000 feet—completely off trail—and couldn’t find their basecamp,” Milestone said. “So the two men split up and went looking in opposite directions.”

One individual found the camp, and because he had cell reception, managed to call his partner. The man managed to communicate to his partner that he was lost, but was clearly suffering from altitude sickness. He was disoriented, and borderline incoherent. “The guy was trying to explain where he was at, but then they lost service,” Milestone said.

Storms, which had been brewing on the peak all day, quickly worsened. “It started raining, heavy cloud cover came in,” Milestone recalled. “Siskiyou Search and Rescue, CHP [California Highway Patrol] Air Ops, and the climbing rangers all searched through the night on that one, but they couldn’t find him.”

The man was later discovered at the bottom of a steep cliff band, “wedged between an ice sheet and the cliff.” He had sustained significant head trauma, and was found alive but unconscious. He died in the hospital two days later. “People have a very lax view of this route,” Milestone said of Shasta’s Clear Creek. “We see a lot of accidents this time of year on that route, because it attracts the least experienced folks, who want to take a stab at climbing Shasta in a non-technical way. Then you get some pretty gnarly weather, or just lack of experience, and bad stuff can happen.”

Just a few days before this fatality, on August 10, another serious but non-fatal glissading accident occurred. An unnamed climber lost control while glissading down another route, Avalanche Gulch, tumbling several hundred feet down the mountain. The climber was injured, but was successfully rescued. In total, Milestone said there have been nine rescue operations on Shasta this season.

What do Shasta’s climbing rangers have to say?

The Forest Service’s Nick Meyers is Shasta’s lead climbing ranger, with 22 years of experience working the peak. He also manages the Mount Shasta Wilderness Program, and serves as director of the Mt. Shasta Avalanche Center. “We try hard to spread the gospel of safe mountaineering practices, but you can’t hit home runs all day long,” Meyers told Climbing.

Shasta usually sees between one and three fatal accidents and a dozen rescue operations each year, so the two deaths and nine calls so far in 2025 don’t exceed average incident levels. According to Meyers, prime climbing season on Shasta begins, snowfall depending, in late April. The season continues through May and June, tapering off after early July, when snow begins to deteriorate.

He explained that although Clear Creek is generally a safe, non-technical route, it’s still a long, steep slog, with extensive elevation gain. If parties venture off-route, anything can happen. When the route experiences good conditions—and is followed correctly—the route is what Meyers and his rangers recommend for late-season climbs.

He also said that the fact that the men involved in the September 12 accident were not carrying crampons or axes wasn’t necessarily indicative of poor decision-making. “We’ll even go so far as to say, you don’t need to bring an ice axe and crampons for Clear Creek in good conditions,” Meyers said. “This is granted—in all capitals—that you stay on the route. Don’t get Casual Day Syndrome. Don’t treat it as just a hike.”

The September 12 incident resulted from not just one, but multiple bad decisions, Meyers said. The men climbed despite weather reports forecasting poor conditions later in the day. This led to them summiting in a whiteout. This poor visibility, coupled with inadequate navigation, contributed to their party becoming off-route during their descent, and arriving at the top of the glacier. The decision to glissade, instead of retrace their steps, was another clear blunder. For one, the men had no axes, and the terrain was in particularly poor condition. “This time of the year, the snow is so nasty,” Meyers said. “It’s dirty and icy—a total cheese grater.”

Shasta is one of the few glaciated 14,000-foot peaks in the contiguous United States, and among the most topographically prominent summits on the continent. Like many 14ers, it can morph from a day hike into a serious objective, depending on season, conditions, route choice, and fitness and experience.

Under ideal late-season conditions, Clear Creek can feel like a straightforward hike (this author ran the route in trail shoes in a morning last September). But weather can change in a heartbeat, and staying on-route is crucial. Checking climbing and avalanche conditions in advance can also help anyone vying for Shasta’s summit plan their trip more safely.

“Remember, a route description is for that route,” Meyers said. “If you get off route, you very likely will encounter different conditions.” This climbing ranger’s final piece of advice? “Do not climb into a whiteout or storm. Check the weather. Use navigation tools. Be prepared. In a lot of the accidents we see, folks are checking boxes that are pretty easy to avoid checking.”

The post Two Climbers Died on Mt. Shasta’s Easiest Route. What Went Wrong? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

A helicopter crash, brutal storms, and multiple dead climbers. For the world’s northernmost 7,000er, tragedy remains a familiar face.

The post Chaos on Pobeda Peak Leaves Four Climbers Dead appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

“I looked out the window. It was snowing heavily outside,” Alexander Semenov recalled. “Then we started spinning.”

It was August 16 and the veteran Russian mountaineer was leading a team in a last-ditch attempt to save Natalya Nagovitsyna. The 48-year-old climber had been stranded near 23,450 feet, not far from the summit of Pobeda Peak (24,406ft), for four days, after breaking her leg while descending the mountain.

Shortly after Nagovitsyna’s injury, horrendous weather had begun to rock the mountain. Temperatures plummeted and winds surged, dashing rescue attempts. The situation was so severe that military helicopters evacuated over 60 people—climbers, guides, cooks, porters, and others—from the peak’s base camp at 13,100 feet. Two Iranian climbers, Maryam Pilehvari and Hassan Mashhadiaghalou, went missing the same day. Both are now presumed dead.

Ten thousand feet higher, Nagovitsyna was clinging to life. Unable to carry her down, her climbing partner, Russian Roman Mokrinsky, left her in a tent and descended to get help. Lower down, he met with the two other members of their party, Italian Luca Sinigaglia and German Günter Sigmund. Sigmund had already made the summit and descended, and Sinigaglia had aborted his own attempt after losing a mitten.

On August 13, the pair reached Nagovitsyna’s tent beneath a rock outcropping at 23,450 feet, with a sleeping bag and pad, camp stove, fuel, and food. But aside from bringing supplies and splinting their partner’s leg with a trekking pole, the men could do little, as they were unable to move her, and even returning to bring the supplies proved disastrous. “They called us from [base camp] and said that we had to go down,” Sigmund recalled in an interview with Russian paper Izvestia. “The weather was getting worse, the roof of Natalya’s tent was torn by the wind, but we couldn’t fix anything. We had to leave her in the destroyed tent and go back to the cave where Roman was waiting for us.”

The ice cave where the men sheltered, at around 22,600 feet, kept being buried by driving snow, and Sigmund realized they needed to descend further. “I said we had to go to the next camp despite the bad weather. Then Luca lost his composure. He shouted for us to go without him. His hand was frostbitten, and he was worried that the doctors would want to amputate it.” Sinigaglia’s condition quickly deteriorated. “Half an hour later he died in my arms,” Sigmund said. He and Mokrinsky descended alone.

Semenov and his crew hoped to use a tight weather window to fly a Russian Mi-8 helicopter as high as they could, to Camp II (17,000ft), to launch a rescue attempt. But heavy winds began battering the helicopter at 15,500 feet, sending them into a spiral. Semenov shouted to his team, “Hold on, hold on, we’re going down!”

Everything happened in an instant, he said. The helicopter smashed into the mountain and tumbled some 1,300 feet down a slope, where it came to rest upside down. “There was pain, screaming,” he recalled. “We were lying on the roof, fuel was leaking everywhere.”

Everyone was injured to some degree, but adrenaline kept Semenov and a few others mobile. They disabled all the helicopter’s electrical terminals to avoid sparking a fire, and managed to haul the most severely injured out on a stretcher. “From the outside we saw that the helicopter was lying tail-down in a crevasse,” Semenov said. As the adrenaline wore off, almost every member of the party began to realize the extent of their injuries, “ruptured joints, sprains, bruises and tears.” Three of the helicopter’s nine occupants, two of the rescuers and the pilot, who fractured his spine, were severely injured, but not fatally. In many respects, it was a miracle. All nine passengers had survived a helicopter crash above 15,000 feet. But for Nagovitsyna, the botched rescue attempt was the nail in the coffin—the beginning of the end.

Rescuers continued to try to reach the stranded climber on foot, but as the days wore on, conditions grew worse. Winds increased, and temperatures dropped as low as –22 °F. “There was a blizzard on the night of the 17th and the 18th,” said Semenov. “There was extremely heavy snowfall, and then there were avalanches on the 19th.” Despite the horrendous conditions, Nagovitsyna clung to life. An unmanned aerial drone flew over the summit that day, capturing footage of her waving from her battered tent.

A second rescue team fought their way to 20,000 feet, but still were unable to reach Nagovitsyna. “Over August 23 and 24, three Italian rescuers and I were preparing to work with a small helicopter provided by the Ministry of Emergency Situations,” reported Semenov, “but by the 25th, everything was cancelled due to bad weather. We could not take off.” Two days later, another drone flew over Nagovitsyna’s tent, and its thermal camera detected no signs of life. She had been above 23,000 feet, alone, for nearly two weeks.

Nagovitsyna and her group were climbing independently, without a guide, but used an outfitter, Ak-Sai Travel, to organize permits and base camp logistics. Ak-Sai did not respond to requests for comment from Climbing. But the group did post a public statement on Facebook, signed by Semenov and a number of other experienced climbers on the peak, announcing the cessation of any rescue attempts:

“The participants of this group, having compared all the risks to the life and health of rescuers, taking into account the difficult weather conditions, [have come] to the conclusion that it is impossible to conduct a search and rescue operation in the current season. Further organization of rescue operations, unfortunately, may lead to more victims.”

An unforgiving mountain

Also known as Jengish Chokusu or Victory Peak, Pobeda Peak sits on the border between China and Kyrgyzstan, in the Tian Shan range. It is the northernmost 7,000-meter (22,966-foot) mountain in the world, and known for its brutally harsh weather.

Pobeda is also one of the five 7,000-meter peaks in the former Soviet Union. Summiting these mountains earns mountaineers a coveted “Snow Leopard Award,” a feat Nagovitsyna was hoping to complete. Since the award was conceived in 1960, 716 people have earned the accolade, but only 35 women.

Pobeda—widely considered the most difficult and deadly of the five—was Nagovitsyna’s last summit to earn the award. She began climbing in 2016, and had summited the four other Snow Leopard peaks, Lenin Peak/Ibn Sina (23,406ft), Korzhenevskaya Peak (23,310ft), Ismoil Somoni/Communism Peak (24,590ft) in Tajikistan’s Pamir Range, and Khan Tengri (22,999ft), also in the Tian Shan. The latter peak was the site of a previous tragedy for Nagovitsyna. In 2021, her husband, Sergey Nagovitsyn, died of a stroke while the pair were on the mountain.

The Khan Tengri incident was when Nagovitsyna met Sinigaglia, but no one else in the party knew each other or had climbed together before. According to Sigmund, they’d decided to climb together simply to secure a cheaper rate from Ak-Sai. “We didn’t know each other personally before the trip, and neither did anyone else in the group,” he said. “We just teamed up for the discount.”

Over 80 climbers have died on Pobeda since attempts on the peak began in the 1950s, and no bodies have ever been recovered from the summit, according to Russian national paper Kommersant. A blizzard killed 11 members of a 12-person attempt in 1955. The sole surviving member, Ural Usenov, was part of the first ascent team the following year, which was led by Soviet climbing pioneer Vitaly Abalakov (the inventor of the Abalakov thread).

Even with modern improvements in gear and apparel, medicine, and technology, Pobeda seems to have become no less deadly. At least a dozen climbers have died on the mountain since 2021, said Semenov, who has been climbing and guiding on the mountain since the 1990s, summited each of the Snow Leopard peaks twice, and made seven 7,000-meter ascents this season.

Semenov explained that it’s not just the peak’s elevation and weather that makes ascents and rescues difficult, but Pobeda’s long, exposed routes. The peak has three summits—East, Central, and West—strung out along a meandering ridgeline. “Recovering [a victim] from a height of 7,000 meters or more is already a very difficult task,” Semenov said. But on Pobeda, with its long ridgelines, the recovery would require “dragging [the victim] more than three kilometers along the ridge to the top of Vazha Pshavela,” the western subsummit of the peak, before descending. “This is much more difficult.”

Perhaps no one knew Pobeda as well as Nikolay Totmyanin. The veteran Russian climber summited each of the Snow Leopard peaks seven times, and died after descending from Pobeda the day before Nagovitsyna’s accident. He once wrote that “the price for reaching the top of Pobeda is the life of one or more climbers. If no one died on Pobeda in a given year, that means no one reached the top.”

A pre-existing injury?

Accounts coming from Pobeda at the time of Nagovitsyna’s accident indicated that her leg injury on the peak was unprecedented, but in an interview with MSK1.RU, Russian climber Alexander Ishchenko theorized that the break was preexisting, and dated to an ascent of another Tian Shan peak, Teke-Tor (14,695ft), earlier this year.

“This tragedy began in the Ala-Archa alpine camp, when she broke her leg during the May holidays,” Ishchenko said. He explained that Nagovitsyna was hit by rockfall, breaking her leg in two places, and he was part of the group that saved her. “Our rescue team split into two groups: some went to pull her across the glacier to the landing site, while others prepared to transport her to the camp.” Nagovitsyna was successfully evacuated.

It’s unclear if her injury on Pobeda was a recurrence of the same injury, which hadn’t fully healed since Teke-Tor, or an unrelated incident. But Ishchenko said that, when news of the Pobeda disaster broke, he was shocked to hear that it was Nagovitsyna stranded on the peak, because she would have had to arrive in base camp in July, soon after her severe injury on Teke-Tor. “My first question is, how did she end up there, two months after a double fracture?” he said. “She acted irresponsibly.”

Alexander Pyatnitsyn, the vice president of the Russian Mountaineering Federation, told Climbing that while “the Federation regrets what happened on Pobeda Peak,” its leadership “calls on everyone who plans to climb high mountains along difficult routes to complete the entire course of necessary mountain training.” (The Russian Mountaineering Federation recommends that climbers who attempt Pobeda hold a “third-class” rank in Russia’s three-tiered climbing certification system, and Nagovitsyna only held a second-class rank.)

In an interview with newspaper Komsomolskaya Pravda, Vladimir Shataev, the official Snow Leopard award record keeper, said that because Nagovitsyna had “skipped” the rankings, he would not have been able to give her the award for her Pobeda Peak climb in the first place. “She broke the rules,” he said. “A climber can set out on a route of a new category only after having completed two routes of the previous category—starting with 3B and further [referring to the six-tiered system of Russian climbing grades]. She went to Lenin Peak, which has a category of 4B, without having completed two 4A routes before that. Then, she went to Khan Tengri (5A), having completed only one 4B route. According to the rules, such ascents, with ‘jumping,’ cannot be counted at all.” The standard route on Pobeda Peak, the west ridge—which Nagovitsyna and her party were using—is 5B.

Semenov said that, regardless of classifications or pre-existing injuries, the deaths on Pobeda were clearly due “to a series of many mistakes.” He said that the groups that ran into trouble on the mountain, both the Iranians and Nagovitsyna’s quartet, were “following the strong teams along their path and their ropes” and “did not know the route itself well, and did not take into account their strength in accordance with the weather conditions.” As a result, when things went south, they were in a poor position to respond.

“Many experienced comrades, including me, tried to dissuade them from climbing,” Semenov said. “But they still went to the mountain.”

The post Chaos on Pobeda Peak Leaves Four Climbers Dead appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

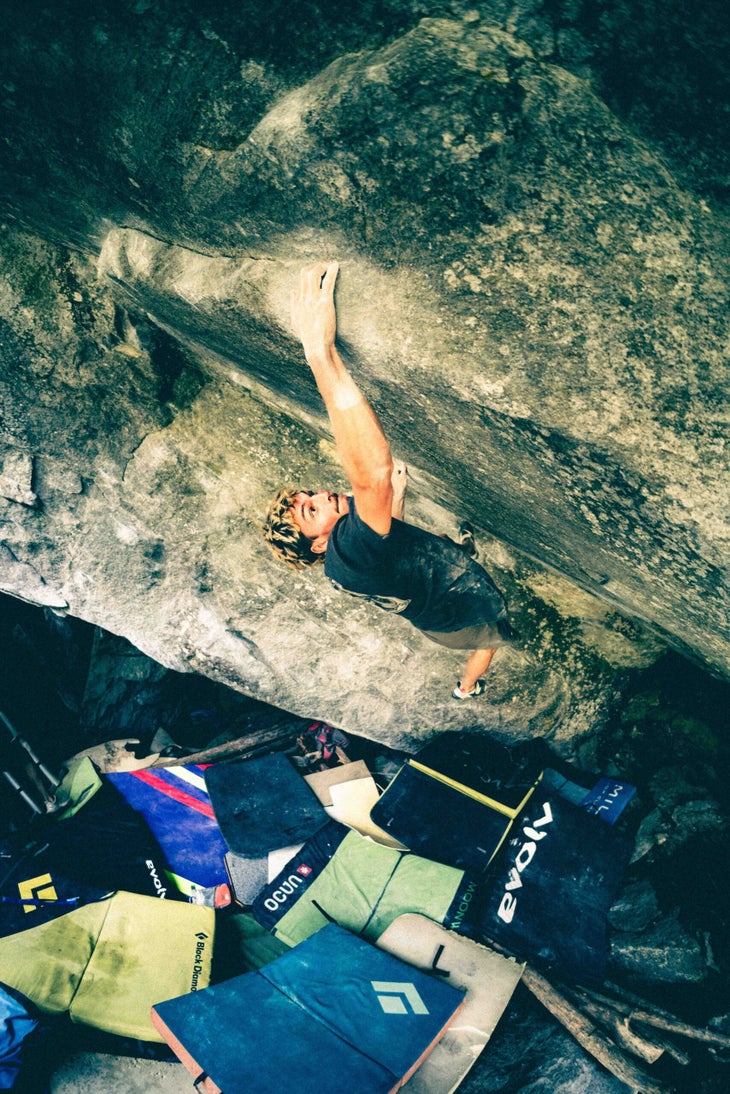

Yannick Flohé and Jules Marchaland just flashed V15, becoming—by most accounts—the first and second climbers to flash the grade, but the history of attempts is far from straightforward.

The post How Many Climbers Have Been the “First” to “Flash V15”? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

“Every time I finish a project, I have this habit of downplaying my performance in my head,” Jules Marchaland told me. “I tell myself, ‘Well, if I did it, then it must be soft.’”

Marchaland, a 24-year-old French ex-competition climber, told me he only really started bouldering outdoors this year. He sent his first V15 boulder (Foundation’s Edge) a few weeks ago. Now he’s flashed one. Marchaland’s effort on the Magic Wood problem Power of Now Direct marks the second flash of a V15 problem in history.

Or was it the first? Or the fourth? It’s a bit hard to say.

According to most media headlines, history’s first V15 flash occurred a few weeks ago, by German Yannick Flohé, also, ironically, on Foundation’s Edge. Flohé offered a humble, candid, and slightly contradictory appraisal. “I knew for a while that this is probably the most flashable [V15] in the world,” he wrote on Instagram, later adding, “to be fair, I don’t really think this is a proper [V15], even though no one has ever downgraded it and there’s for sure some softer ones out there.”

Still, he felt comfortable enough being the first person to step over the line and claim a V15 flash. “Grading is always tricky, especially when you flash something, so [I’m going to] take the soft [V15], like all the other greedy grade hunters on this one.”

The world’s first V15, like the first problem or route of any grade, is somewhat up for debate, but climbers have been scaling V15s for roughly 25 years. Fred Nicole’s Dreamtime is one strong contender. Nicole suggested V15 when he put the Cresciano rig up in 2000. Repeater Bernd Zangerl agreed, but third man Dave Graham suggested a downgrade to V14, and the problem was subsequently considered, at best, a slash V14/15. (A crucial hold broke in 2009, and Dreamtime now sits at firm V15.) The Rocklands problem Monkey Wedding (2002), another Nicole problem, is also a contender. This problem went through the reverse—here Nicole initially proposed V14, but subsequent ascensionists, including Paul Robinson, Adam Ondra, and Daniel Woods, all agreed V15 was more apt.

Even though it’s taken 25 years for a V15 flash to make headlines, the world’s strongest climbers have been teetering on the edge of one for more than a decade. Woods flashed another V15 Nicole problem, Entilege, in 2011, but suggested a downgrade to V14. In 2015, Ondra flashed a Woods V15, Jade, and suggested a downgrade to V14. In 2018, Jakob Schubert flashed Chris Sharma’s Catalan Witness the Fitness—which Sharma had not holistically graded but had said was an 8B+ sequence into 8A+, suggesting the problem was V15. Grading calculator Darth Grader agrees, noting this formula translates to hard V15. Schubert downgraded the problem to V14. In 2023, Tomoa Narasaki flashed Shinichiro Nomura’s Gakido, proposed at V16, and then downgraded it to V14. The list goes on.

To be clear, no one is debating that these problems are V15 anymore. But there is an established history of top-end climbers seeming to be uncomfortable staking their name to a grade on a flash, and instead shying away from the line and proposing a post-flash downgrade. Marchaland’s words seem apt, “If I did it, then it must be soft.”

The resulting conundrum is paradoxical. Is a problem soft because it was flashed? Or was it flashed because it was soft?

Foundation’s Edge, established by Dave Graham in 2013, is a popular V15. It has seen close to 20 ascents, if not more. Many recent repeaters, as Flohé mentioned, have suggested it is soft for the grade: Woods, Sam Weir, and Pietro Vidi, to name a few. Will Bosi and Simon Lorenzi both sent it in a single session, and Aidan Roberts came close to a flash, too.

But Power of Now Direct—a direct start to a reachy, Giuliano Cameroni V14 roof that was pioneered by Simon Lorenzi—has seen only a quarter of the ascents as Foundation’s Edge, and doesn’t have the same reputation as a known softie. In fact, Lorenzi called it “one of the craziest and most powerful boulders that I’ve ever done.”

Marchaland explained that although he really just wanted to “experience” the boulder, on some level he did come there specifically looking for a flash. “When I saw Giuliano’s video back then, I always knew that this line suited me well,” he said. “And when my friend Mejdi [Schalck] did the boulder, he made it clear to me that it was my style, and potentially something I could flash.”

After arriving at the problem, Marchaland could see that his friend’s appraisal was accurate. “I’d say the boulder is 100 percent my style—big holds, far apart, on a steep overhang.” He described it as “like a Kilter problem,” three apish moves on good crimps, requiring mostly finger strength.

Unlike Flohé, Marchaland didn’t play his ascent down, but he didn’t play it up either. He’s just happy with his performance. “It’s really hard to have a good idea of a grade when you flash something,” he admitted, but, “over time I’ve learned to accept that I’m capable of climbing some pretty hard stuff. So I tend to go along with the opinions of the climbers before me. Everyone’s strengths are different, and that’s why grades can be so variable.”

To Marchaland’s point, someone who is able to flash a problem is inherently a poor judge of its difficulty, both because a flash by nature entails limited research or preparation (compared to someone who sieges it over multiple seasons or years) and because anyone who can flash a problem could simply be too strong to accurately grade it. Accurate personal grading works near-limit. The difference between a 5.8 and a 5.9 is nearly imperceptible for Adam Ondra. But for someone who projects 5.9, the gap between those grades is profound.

Marchaland added that, for him, a flash represents an appealing challenge. “I’ve always been looking for that perfect flash, right at the limit of my abilities. This one was on my list, and once I got there, I waited a week for the right conditions, and it worked out!” He said that blasting up Power of Now Direct still “feels surreal, like a dream” and pulling out over the top of the problem was a moment he’d imagined in his head “too many times.”

“Everything was just like in my dreams,” he added. “The holds were the same as I imagined them. I have nothing to add, only thanks to my G’s for the support, and to Simon for the trip and the help on the proj.”

Now someone just needs to go downgrade Foundation’s Edge and Power of Now Direct. Then I can write this article again in a few years.

The post How Many Climbers Have Been the “First” to “Flash V15”? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Lincoln Knowles says he is “free soloing a harder route every day” until he falls. Why are we watching?

The post Climbing’s Newest Social Media “Star” is Going Viral for Free Soloing appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

I found Lincoln Knowles through an Instagram post. The floppy-haired 21-year-old was dancing to the rap song “Young Black & Rich” on the edge of a cliff, mimicking a Sumatran child who recently went viral for dancing on the prow of a racing boat. A text overlay read: “When you just got the first free solo ascent of the longest sport climb in America (1900’) but you’re still not sponsored so you have to aura farm for $.”

Like an up-and-coming OnlyFans model, Knowles provided his Venmo in the caption. Over 80,000 people had liked the post, but I found myself instantly irritated. Who is this clown? He wants me to send him money… for free soloing?

“No one is Venmo’ing you for that bro,” I wrote. In the days that followed, my comment racked up a measly four likes. Meanwhile, the top comment on the post (4,300 likes and counting), gushed that Knowles was “coming for alex honnold’s title for free soloing icon.” Was I missing something?

The line Knowles soloed, Squawstruck (5.11b), is certainly a contender for longest bolted route in the United States. It’s also fairly sustained in its difficulty—22 pitches, predominantly mid-range 5.10—but it has just one 5.11 pitch, and multiple opportunities to bail by traversing. In other words, it’s not exactly the sort of effort that most serious free soloists would brag about online.

Bragging about free soloing online, however, is exactly what Lincoln Knowles does for a living.

A deeply unhealthy approach

Lincoln Knowles has become infamous for his Instagram and YouTube pages, which include videos such as “DRUNK BOULDERING (banned from gym),” “free soloing buildings until I get arrested” (he doesn’t), and a campaign to “free solo a harder route every day until I fall.” (The most recent video in the latter series was Squawstruck, and was posted around five weeks ago. So if he’s still alive, that means Knowles free soloed a 5.17c today. Congratulations!)

At first glance, it’s hard to understand what draws viewers to this type of video. Do people really want to see him fall? Possibly. Right now, Knowles is one of the most viral figures in climbing media. His Instagram has over 70,000 followers, some of his posts have over 150,000 likes, and his YouTube channel, “Knowles and Company,” has racked up more than 13 million views.

When I called Knowles up, he told me he didn’t mind that I’d poked fun at him online, telling me that my reaction was kind of the point. He sees his online presence as a character, designed not to reflect his actual personality, but to garner engagement. “It started with pure rage-baiting,” he said. “Now, it’s evolved to, like, half rage-baiting and half shock value.” Knowles even makes fun of himself on many of his own posts, like a troll alter-ego, by commenting using his personal account, @lincoln.knowles.

When I asked Knowles about his “Free Soloing a Harder Grade Until I Fall” videos, he was reluctant to admit he was joking. “It’s kind of an excuse to push my solo grade in a way that is structured,” he said, “and… also try to make money.”

Rock climbing’s post-COVID explosion—coupled with the rise of self-made content creators on platforms like YouTube, TikTok, and Instagram—has given us a fresh breed of climber: the in-your-face swaggerer, the spawn of the chronically online age. These new figures, like Knowles, have managed to eschew the barriers of traditional media and sponsorship. Instead, they hand-deliver their exploits to the masses without a filter.

In many ways, the new system has democratized the path to fame and fortune. If you’re savvy enough to create the type of content people want to see, you can give the middle finger to brands, magazines, and other age-old gatekeepers of the spotlight. You don’t even have to climb hard. You just have to make videos that people enjoy watching, and your fans can finance your exploits. Knowles does have some traditional sponsors, but supplements his income with a crowd-funded Patreon and video ad revenue. “I want to make money off of climbing,” he told me. “My end goal is to climb as my job, and however I can get there is fine with me.”

Knowles is also using his newfound fame on social media to pressure himself to climb harder: “If I didn’t have this external pressure [from Instagram followers] to keep upping my soloing grade, maybe I would just have stopped at 5.10b,” he told me. “Basically, I have this challenge that holds me accountable, where I have to keep soloing harder.” When I pointed out that such an aggressive soloing diet would likely end in near-term death, he shrugged me off. “You’ll have to subscribe to my Patreon to find out.”

At this point in our call, I began to feel a bit sorry for Lincoln Knowles. I also began to wonder if I was simply missing something, because I’m not a free soloist. So I hit up someone who might understand. I called Alex Honnold.

“This is, like, everything I hate about influencer culture,” Honnold said after I shared Knowles’s account with him and he scrolled through the posts. He admitted that he could relate to the impulse to continuously up the ante and shock factor as a young climber, but added that when he was a young soloist, in the pre-social media era, it had been easier to compartmentalize. “That outside pressure influenced my soloing as well,” Honnold said. “It will always factor in, but by posting on social media, you’re putting it on steroids.”

When I asked Honnold about Knowles’s idea to use social media to pressure himself to continue soloing harder routes, he was frank. “That is a deeply unhealthy approach to free soloing,” he said. “Free soloing is always a deeply personal experience, because the consequences are always death.” Ultimately, he said that it comes down to motivation, making sure the urge to free solo is intrinsic, not coming from some external catalyst. “Part of that is parsing out anything that could affect your motivations, that could push you physically or psychologically beyond what you’re comfortable with,” Honnold explained.

But in the end, he was reluctant to judge. “I’m sure there were old climbers when I was coming on the scene that thought, ‘That guy’s sketch,’” he admitted. “With a young person, you want to give them the leeway to find themselves and grow up a little, doing what they love to do.”

My question is this: What is it that Lincoln Knowles loves to do? Is it going free soloing? Is it rock climbing at all? Or is it posting videos of himself, making money, or something else?

Is Knowles’s online persona unprecedented, or a logical next step?

Climbing has attracted devil-may-care figures for generations. For the Stonemasters of the 1970s, drugs, alcohol, and a general disregard for safety were often part-and-parcel to the climbing experience. It’s easy to cast these soloists of the past in a gentler light, compared to a self-aggrandizing social media soloist like Knowles. But it’s largely the landscape that’s changed, not the figures that are attracted to it.

Old-school figures like Tobin Sorenson and John Yablonski, and even more recent soloists, like Peter Croft, Dean Potter, and Honnold—could not share their exploits immediately with the masses, at least not without the helping hand of a sponsor or media outlet. To give Tobin Sorenson props on a solo, someone would have had to literally walk up to him in Camp 4, or mail him a letter. Knowles, by contrast, can post a video mid-free solo, and 100 people will tell him “good job” before he’s finished the next pitch.

Knowles is far from the only free soloist trying to make a name for himself using social media. When I stumbled across his profile, I was immediately reminded of self-taught ice climber Eugene Vahin, who also posted “rage-bait” on Instagram under the moniker @take_a_course. Vahin died in a fall earlier this year.

Other still-living free soloists have managed to integrate their exploits into a social presence with great success, like Alain Robert. Robert put down a string of audacious 5.13+ free solos in the late 1980s and early 1990s, before switching to a career climbing skyscrapers. Although he primarily posts old footage from his heyday, Robert’s Instagram following has soared from a few hundred thousand to over 1.5 million since the pandemic.

Looking for some perspective on Knowles, I also chatted with 24-year-old Alexis Landot, another urban soloist who also makes a living posting online. “From a business point of view, what Lincoln is doing is working,” Landot told me. “No doubt. He’s getting a lot of haters, but haters are always good, if you can manage it. From a personal point of view, I don’t know. He’s playing a character.” Though only a few years older than Knowles, Landot has given TEDx Talks, been profiled by Esquire, and generally kept his image out of the gutter. His social media is still filled with clickbait titles like, “I slipped and almost fell while free climbing [a] skyscraper!” but he avoids content designed to enrage, and instead focuses on scary or shocking footage.

Landot isn’t particularly proud of his online presence, but says it’s part of the game. “Have you seen my Facebook?” he joked. “It is so cringey.” He later explained, “I have two ropes, one in each hand. One is money, one is passion. Sometimes I pull more on one than the other, but I keep both in my hands.”

As a soloist, you want to be you

Knowles hasn’t been climbing for long. He grew up in the flatlands of Kansas City, Missouri, watched Free Solo when he was 13 years old, and began pulling plastic indoors two years later, at age 15. Within a year, he was taking trips to boulder outside at Horseshoe Canyon Ranch. It was around this time that he also started free soloing parking garages, churches, and other urban structures around Kansas City. He climbed his first multi-pitch at age 18, and has since moved to Salt Lake City for the climbing. Just a few weeks before we chatted, he sent his hardest redpoint, Machine Gun Funk (5.13a) in Colorado’s Clear Creek Canyon.

For as long as he’s been a climber, Knowles has also been a content creator. He dropped his first video, “Greek Gods Rap Video” in October 2018. But his early efforts were harmless skits. I grinned watching them, because they reminded me a lot of the home videos I made as a kid. “Greek Gods” shows a baby-faced Knowles and his friends dancing and rapping about Olympian deities. Another clip, “Double Diet Coke,” is a mockumercial for the soda brand.

But Knowles told me that around a year ago, he decided to blend his climbing with his YouTube and Instagram channels. His first videos documented roped climbs, but eventually he started filming his free solos. Then he began filming himself, selfie-style, mid route.

Honnold has famously (or infamously) filmed his own free solos in the past, but he said that in general, any integration of self-documentation and free soloing is “super sketchy.” He insists it’s different from having a third-party film you, because it requires you to think about two things at once—your climbing, and your videography.

Honnold is certainly no stranger to garnering fame and fortune for free soloing. He admitted that balancing motivations is a constant tightrope walk, but as an emerging climber, he said that instead of chasing fame, he strove to “do rad stuff” he found personally inspiring, and let the fame come to him. “My motto has always been, if you do something cool enough, other people will come film you. You don’t need to film yourself.”

For Knowles, bringing a camera up the wall to film himself felt like a logical progression. “Most soloists just keep their shit private, and I agree with that to some extent, if you think that the camera is gonna mess you up,” he said. “But also if you have a job you hate, and you’re soloing every day, doing things that the average person would think of as incredible and amazing—I don’t understand why you wouldn’t try to at least attempt to monetize it.”

It’s difficult to determine exactly how much risk Knowles is taking. His videos are often heavily edited and feature intentionally misleading titles and claims. In one video, he claims to be “trying a V10 dyno,” on what’s clearly not V10. In another, he shotguns a beer, chucks the can on the ground, and says he’s going to free solo a 5.11, but never gets more than 10 feet off the ground. Then there’s the “free soloing a harder route every day” series, which for obvious reasons, hasn’t actually occurred.

To Honnold, this is the biggest issue with Knowles; his Internet presence is so drenched in irony that it’s hard to parse what’s real and what’s not. In a word, he’s fake. “Posting as a character, it’s sketchy,” Honnold said. “As a soloist, you want to be you. You want to be honest with your motivations, your intentions, and all the things you’re doing. I make a real effort so that what you see in the media is exactly what you get in real life. It’s just me. Sometimes I’m scared. Sometimes I’m not. Sometimes I send, sometimes I don’t. But it’s all honest.” Landot agreed. “As long as you’re always being honest, you’re not setting a good or bad example,” he said. “You’re just showing the truth.”

All types of people interact with Knowles’s videos online. Many are rock climbers, and plenty discourage him. Others respond with gag-worthy ego stroking. Wrote one crooning fan: “Everyone is saying stop cause they are too cowardly to witness greatness born from passion.” Another: “Free soloist here. This is literally the mood.” Many of these followers, as corny as they are, appear somewhat familiar with rock climbing, at least enough so to realize free soloing is not standard practice, or an “entry-level” discipline.

But for others, Knowles is their first exposure to climbing, and his content appears to set a dangerous precedent. “I’m here in Utah looking to get into free soloing, any recommendations?” asked one follower on Instagram, as though referencing pottery or woodworking, a hobby one might dabble in. “What does ‘free solo’ mean for those of us that don’t know a thing about climbing?” wrote another.

For some new climbers, Knowles may be an introduction to rock climbing, and like all of us, he has his own heroes. He told me he was inspired by the famous soloists that have come before him: Peter Croft, Brad Gobright, and Honnold, to name a few, even though he’s aware “they probably disagree with most of my principles.”

“I try not to idolize anyone,” Knowles told me. Later, when I asked him if he’d ever interacted with Honnold, he said, “I don’t really want to meet him for a long time, because he holds this place in my head where he’s a fictional version of himself, and if I meet him, then it’s like shattering the illusion, you know?” “I dunno,” I said. “That sounds a lot like idolization.” Knowles laughed.

In many ways, Knowles reminds me of a child kicked out of the huddle at recess, clamoring to get in and play with the big kids, no matter the cost. “@enormocast [Chris Kalous] blocked me,” he told me at one point during our conversation. “I guess he just didn’t like my reels. @tradprincess [Mary Catherine Eden], she blocked me, too!”

“It especially hurts when I see Enormocast blocked me, because I like Chris’s podcast so much,” he admitted. “I hope one day I can go on there and have him grill me. I feel like he would have the best questions.”

(Ouch.)

It’s clear that Knowles is proud of the hate he receives and proud of being blocked by well-known climbers, but also sort of embarrassed. “A lot of climbers want social media following, but they don’t want to sell out to get it,” he added. “That’s kind of what I did. It’s easy for me to complain about not being taken seriously, but it’s definitely my fault for portraying myself this way.”

Worm food and legacy

From getting to know Knowles, it’s clear that, like many free soloists, he clings to an absurdist, and perhaps existentialist, view of life. We could die any second, and nothing really matters. Life’s short, and has no inherent meaning.

I tend to agree. Life has no meaning except what we give it.

So if Knowles and his followers have made it this far into this essay, let’s gather around and take a knee. Life is short. We will be worm food eventually. Maybe in 30 years, maybe tomorrow. Selling out a little bit to make ends meet is fine, but when you go splat, all the Instagram and YouTube cash in the world doesn’t do much except pay for a nice casket. What’s left? Legacy.

So, Lincoln, dude. You have a platform. You’ve got tens of thousands of eyes on you, maybe hundreds of thousands. A lot of them are clearly new climbers. Surely you have more to offer the world than “rage bait and shock value.”

I started climbing at age 11, introduced to our sport first by John Long’s writing about the Yosemite Valley heyday, and later classic tomes like Maurice Herzog’s Annapurna and Tom Horbein’s Everest: The West Ridge. Being introduced to climbing through these mediums impressed upon me that climbing was about more than being strong or agile. (If that’s what you’re after, try weightlifting or gymnastics.) Climbing was about more than being fearless, too. (If you want that, play Russian roulette.)

What I learned, before I ever tied into a route or stood on a summit, was that if I wanted to be a climber, I didn’t just need strength and tenacity, but integrity. I learned that climbing was about what you did and how you behaved in the wildest, most remote reaches of the planet—when no one was watching. I learned that climbing was about breaking trail and leading by example. That it required courage that was quiet, not loud. That it was about downplaying hard, scary things, not hyping them up.

I will always be grateful that this was how I was introduced to our sport. I’m grateful I’m not a kid today, scrolling Instagram, being introduced to climbing by Lincoln Knowles.

The post Climbing’s Newest Social Media “Star” is Going Viral for Free Soloing appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

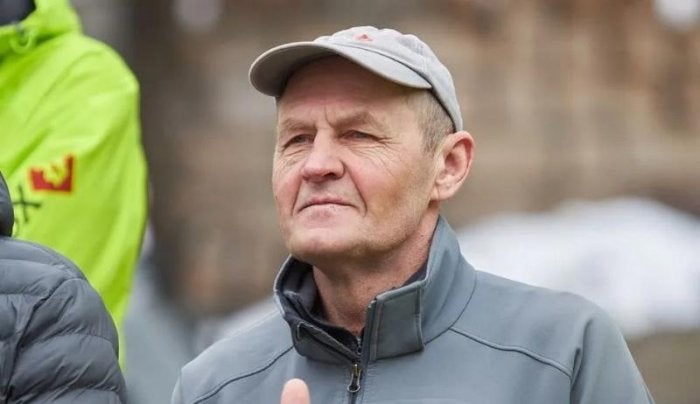

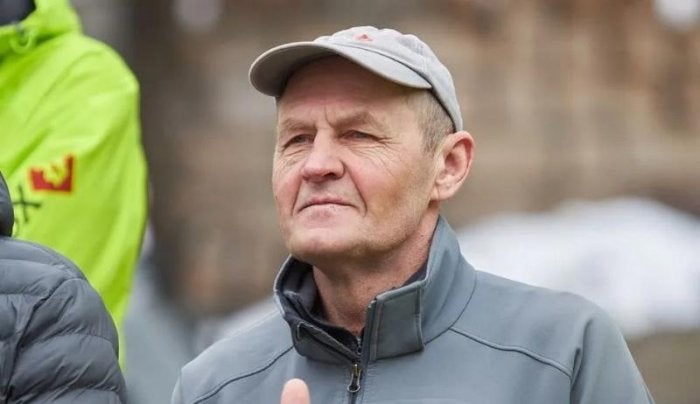

Friends and climbing companions shared their memories of “Iron Uncle Kolya,” Nikolay Totmyanin, who died August 11.

The post Legendary Russian Mountaineer Dies in Kyrgyzstan appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

One of Russia’s most accomplished and revered mountaineers died last week, after an ascent of Jengish Chokusu, also known as Pobeda Peak, a mountain on the China-Kyrgyzstan border. Nikolay Totmyanin, 66, became ill while descending the 24,400-foot summit on August 10. After getting off the mountain on his own, he managed to reach Kyrgyzstan’s capital, Bishkek, where he checked into an intensive care unit. He died the following morning.

Prolific and dauntless, the 66-year-old Totmyanin was a living legend in Russia, but kept a low profile. Everyone who spoke to Climbing for this story remarked, above all else, on the humility of the man known as “Iron Uncle Kolya.”

Internationally, Totmyanin is perhaps most well-known for being a key member of the Russian team that made the first ascent of Jannu’s (25,295ft) north face in 2004, winning a Piolet d’Or. But he participated in an array of other cutting-edge expeditions during his 50-year-career, including more than 200 significant climbs in the Caucasus, Pamir, Tien Shan, Karakoram, Alps, Himalaya, and Alaska ranges, both recreationally, and as a leader of the Russian national mountaineering team.

Nikolay Anatolyevich Totmyanin was born on December 8, 1958, in the small rural village of Leninskoe in Kirov Oblast. In 1972, aged 14, he moved alone to St. Petersburg (then Leningrad), to enter a Soviet boarding school for physics and mathematics. He began climbing in 1976, when he was 18, with the Leningrad State University climbing club. He graduated from the university in 1981, with a degree in physical mechanics, and spent the remainder of his life working as a nuclear power engineer in Leningrad/St. Petersburg, in between climbs and his part-time work as an alpine guide.

Longtime friend Sergey Semiletkin first met Totmyanin at the university club in Leningrad when the pair were students. In 1988, the two were part of a four-man team that established a landmark technical line, Semiletkin’s Route (Russian 6B, the grading system’s highest difficulty), up the 3,000-foot north face of Free Korea Peak (15,550ft), in Kyrgyzstan’s Tian Shan range. At the time, the route was the most difficult in the region.

“It cannot be said that Kolya was distinguished by super climbing abilities,” Semiletkin recalled, adding that instead, what made his late friend stand out—and clearly contributed to his moniker, Iron Uncle—were “his calmness, and confidence” even in the most harrowing, exposed pitches. He said Totmyanin’s nerve was unparalleled, and bolstered the spirit of any team he was a part of. “His endurance was amazing,” Semiletkin added. “A person with such character could have been born only in the depths of Russia, far from the big cities.”

Totmyanin went on to make multiple winter first ascents, and climbed nearly 50 7,000-meter peaks and five 8,000-meter peaks, some multiple times, all without supplemental oxygen. Among other prominent expeditions, he was part of a team that put up a new route on the south face of Lhotse (8,516m) in 1990, and led a rope team on the 2007 siege expedition that made the first ascent of the foreboding west face of K2 (8,611m). Totmyanin also earned the Snow Leopard Award—an accolade given to climbers who summit all five 7,000m peaks in the former USSR—seven times.

On Everest (8,849m), which he summited twice, Totmyanin free climbed the technical Second Step at 5.8/5.9, a feat which has only been performed four times in history. In 2013, he and three partners also made the first winter traverse of the Bezengi Wall, a ridgeline linking the highest peaks of the Central Caucasus.

In 2003, Totmyanin wrote of Pobeda—a mountain he summited at least seven times and that would eventually kill him— that “the price for reaching the top of Pobeda is the life of one or more climbers. If no one died on Pobeda in a given year, that means no one reached the top.”

In the above essay, Mountain.RU editor and former climbing partner Sergey Kalmykov added a postscript noting that Totymanin was the sort of partner who, if you were missing a crampon, would gladly give you his own without a second thought, and continue on without them. “He was always at the forefront of the attack,” Kalmykov wrote, “always in brilliant physical shape [and] always at the highest level of skill.” He was also “always calm, with a light sense of humor,” and “when many people lost their nerve and endurance, he continued to remain balanced and laconic.”

Despite his substantial list of accomplishments in the mountains, what friends and family wanted memorialized most about Totmyanin was an inclination to downplay his achievements. “He remained an exceptionally humble man, a person of few words, but with a great heart,” friend Elena Dudashhvili wrote on Facebook. “He was always reliable, attentive, and ready to help in any situation. You could go into the mountains with him knowing that by your side was someone you could trust without a second thought.” In a sense, his “Iron Uncle” nickname seems a perfect summary: partly a testament to his physical endurance, but also a nod to the internal fortitude and level head that made him the bedrock of the teams he was a part of.

Alexander Odintsov, who led the Piolet d’Or-winning Russian Jannu expedition, and climbed with Totmyanin on many other occasions, told Climbing that it was “hard not to envy him” for his skill and endurance in the mountains. “If normal people survived at altitude, Kolya flourished,” he said. “I think he was the world champion in staying at an altitude of over 7000 meters. I knew many people whom the god of altitude kissed on the lips. But Kolya was the best of them all.”

Odintsov said his late friend and climbing companion operated both in the mountains and in everyday life with a complete lack of ego, a quality that was extremely rare in the mountaineering world. Despite Tomyanin’s revered status in the Russian climbing world, Odintsov said he never let the acclaim go to his head. “He was a celebrity, and fame is a difficult test, especially for those who are deprived of it, but Kolya simply never realized his exceptionalism.”

Temperamentally, he compared his friend as akin to “Buddha,” saying, “I can’t imagine him in a state of irritation, and I do not know a single person who could treat him with hostility. Any attempt to quarrel with him was doomed to failure.”

One of Odintsov’s favorite moments with Totmynanin did not take place in the mountains at all, but while the pair were driving down a street in St. Petersburg, on their way to attend a press conference after their Jannu expedition. A woman driving another car haphazardly pulled out in front of them, almost causing a serious crash. “I barely had time to brake, and Kolya lowered the passenger window,” Odintsov recalled. Though she had been at fault, the woman was angry, and seemed about to curse at the men, “but Kolya tells her, ‘Madam, you are such a beautiful woman, and yet you can die in the prime of life [if you drive like this]!’ The situation was instantly defused, the woman was no longer angry, and was instead “left standing with her mouth open,” Odintsov recalled.

Reminiscing on his late friend, he offered words of Russian poet N.A. Nekrasov: Mother Nature, if you did not sometimes send such people out into the world, the field of life itself would have died out!

Russian alpine chronicler and Mountain.RU editor-in-chief Anna Piunova offered similar praise. She told Climbing that, “Kolya was the most tolerant person I ever knew. Remarkable, given how little tolerance there is in Russia, where people are quick to judge and just as quick to say it out loud. He had a way of smoothing over every conflict before it could even start. That was who he was.”

Dudashhvili, who was with Totmyanin when he died, said that “he came to Bishkek by himself, and we were speaking on his arrival. His condition was suspicious, so we called an ambulance.” She said that after that, “everything happened very, very quickly.” Some outlets reported Totmyanin died of a heart attack, but Dudashhvili disputed this, saying “the doctors didn’t have time to make a diagnosis.” An acute altitude illness appears likely, perhaps high-altitude cerebral edema, given the slightly delayed progression and death.

Totmyanin was married at the time of his death, and is survived by both children and grandchildren, but a family member who spoke with Climbing for this article stressed that throughout his life, Totmyanin made a point of never bringing his family into the spotlight, and requested this be upheld here. He was laid to rest at the Smolenskoye Orthodox Cemetery, in St. Petersburg, on Sunday.

The post Legendary Russian Mountaineer Dies in Kyrgyzstan appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Tanner Wanish and Michael Vaill repeated the 32-mile “Goliath,” the longest technical traverse in the world. Would they do it again? Maybe not.

The post Want to Try the Goliath Traverse? Everyone Who Has, Says: “Don’t” appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

When I spoke with Tanner Wanish after he and Michael Vaill finished the Goliath Traverse (5.9/5.10; 80,000ft) on Monday evening, the vibe was less “excited victor” than it was “lucky survivor.” “I’m happier to be done with it than I am to have done it,” Wanish said. Over nine days beginning on July 27, Wanish and Michael Vaill made the second ascent of Vitaliy Musiyenko’s mammoth solo enchainment of 60-plus peaks in the High Sierras.

Wanish and Vaill are best known for the “Yosemite Quad,” a sub-24-hour linkup of four of the most iconic faces in Yosemite Valley: El Capitan, Mt. Watkins, Half Dome, and Washington Column. But when the pair completed the Quad last fall, they were cool as cucumbers: “We just had a good day out climbing,” Vaill told me at the time.

The Goliath was another story. “In terms of output, maybe this would be like doing the Quad every other day for eight days,” Wanish said. “It’s just egregiously more challenging. We covered a similar vertical distance (~10,000 feet) every day on Goliath as on the Quad, but here it’s unroped, on loose rock in the alpine, with 25 pounds of gear on your back, not knowing where you’re going to sleep, where you’re going to get water. It was overwhelming.”

The Goliath is essentially a 32-mile backpacking trip along a tightrope in the sky, where a single misstep would prove fatal. The route, which begins at Taboose Pass in the south and ends at Paiute Pass in the north, follows exposed and often loose fifth class rock—largely at elevations between 13,000 and 14,000 feet—along the undulating spine of the Sierra Crest. (Musiyenko wrote about the climb for a 2022 print feature in Climbing. A detailed map of his route is also available in his report for the American Alpine Journal.)

For Musiyenko, the project was intended less as a formal route for others to repeat and more a personal exploration of style and raw commitment. “For me, what became the Goliath Traverse was a test, and an attempt to get as close as I could to the limit of my own mental strength [and] fitness,” said Musiyenko, who completed Goliath unsupported. When I texted with him over the weekend, a couple of days before Wanish and Vaill finished their ascent, Musiyenko admitted that he “never imagined Goliath would be something other people would be interested in repeating. In a way, it is exciting, but I also would feel completely devastated if someone got hurt.” He added, “I’d like to make sure the audience understands this route is not anything that should become popular.”

Wanish had wanted to repeat Goliath since Musiyenko established the line in 2021. “I remember watching Vitaliy do this [on social media], and just being like, ‘What the fuck is this guy doing?’” he recalled. “Because he didn’t say where he was going. He just was posting updates on his social media: ‘I made it here,’ and ‘I made it here.’ He just kept going, and going, and going for eight days. It rocked my world. It was the craziest thing I’d ever seen.” (Musiyenko and Wanish) have since become close friends and climbing partners.) Initially, Wanish said he planned to go solo on Goliath, but eventually convinced Vaill to come along. The duo spent the last six months training like mad to make it happen.

For Wanish and Vaill, the second ascent wasn’t formed from a desire to match (or outdo) a previous effort, but to test themselves on their own terms. They did not follow Musiyenko’s style—alone and without a cache. Instead, they stashed supplies at Bishop Pass, roughly halfway through the traverse, and also spent a full day resting there. “The goal was just to complete this thing,” Wanish said, laughing. “To frame it as an FKT attempt or whatever would be psychotic.”

Wanish had traversed some of Goliath’s terrain before, including the popular Thunderbolt to Sill Traverse, a short but technical enchainment of five 14ers, and the Evolution Traverse, an eight-mile line rimming the Evolution Basin, but said “around 90% of this terrain was new for both of us.” He and Vaill initially planned to take an extra month to recon sections of the ridge, but Wanish said Musiyenko advised them against that, because it might psych them out. “He was like, ‘Dude, you might get a little bit of help there, but overall, it’s going to be an enormous amount of work, and it’s probably going to stress you guys out more to know what’s coming and to have to repeat some of those sections.’”

The pair brought a 60-meter 6-millimeter rope and used it for about a dozen rappels, but did all of their climbing unroped. Aside from a single rainy night, the weather was sublime, and nothing objectively bad happened (there was no near-miss with rockfall, no one took any falls), but it was still nine days of high consequence climbing. “There’s at least a couple of days where you’re in fatally consequential terrain for six to eight hours, straight,” Wanish said. “It’s hard to stay locked in for that long, that many days in a row. It was mentally exhausting.”

Wanish said that the Goliath was certainly the hardest climbing objective either he or Vaill had ever completed, by a significant margin, but he seemed to have trouble deciding whether he felt proud he’d done it, or ashamed of the risk he’d put himself through by free soloing so much terrain. “I’m really proud of our performance,” he explained, “but also a large degree of it felt like luck or chance.” He was overwhelmingly grateful to Musiyenko, “for having had the vision and sheer grit to open this,” but was clearly glad Goliath was in the rearview. “It was a good objective for us, for what we were looking for,” he said, “but having done it, I would not recommend this to anybody else, unless you’re looking for a life-changing experience.”

Wanish says that the Goliath irrevocably “changed my perspective on risk in the mountains.” Wanish said that while overcoming fear and managing risk is one of the hallmark rewards of climbing—as with almost all adventure sports—some of the Goliath felt too much like a dice roll. “Danger can amplify purpose or meaning in the mountains,” he said. “You can tell yourself, ‘Oh, this is more meaningful, because I put myself out there and survived. But the Goliath felt like it had a disproportionate degree of luck built into it, rather than skill.”

Wanish placed much of his success, both physically and mentally, on his bombproof partnership with Vaill. The men have similar levels of risk tolerance, and although morale fluctuated throughout their nine days on the traverse, but when one was down, the other managed to boost his partner up (usually with a hefty dose of classic rock, like The Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin). “If morale starts dropping and we’re both feeling sorry for ourselves, we put some music back on and it turns things around.”

On some days, both hit a wall simultaneously. Wanish said at those points, each put on a brave face for the other. “We had to artificially inject some ‘fake stoke’ sometimes,” he said. “When we felt mentally drained, we made a real effort to be vocally joyous, singing and hollering. If you can fake it long enough, eventually that stoke kicks in and becomes real.”

The post Want to Try the Goliath Traverse? Everyone Who Has, Says: “Don’t” appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

A famed German biathlete, Laura Dahlmeier, perished on Monday while scaling a remote mountain in Pakistan.

The post German Alpinist Laura Dahlmeier Dies From Rockfall in Pakistan appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

While climbing the remote Laila Peak in Pakistan, famed German Olympic biathlete Laura Dahlmeier died on Monday, July 28, while rappelling. Dahlmeier was descending Laila Peak (20,000 feet), a tooth-like summit in the remote Hushe Valley with her climbing partner, Marina Krauss, also from Germany. At an elevation of around 18,700 feet, the women were struck by rockfall.

According to a statement from Dahlmeier’s team, published on her Instagram, the pair were rappelling when their rope dislodged rocks that hit Dahlmeier. Krauss remained unharmed, and immediately sent out an SOS with her satellite messenger. She then tried, for several hours, to reach her fallen partner, but the difficulty of the terrain and the risk of further rockfall stymied her attempts. As night fell, Krauss descended to her base camp.

Rain, wind, and poor visibility initially impeded efforts to rescue Dahlmeier by helicopter. By Tuesday morning, rescuers in search helicopters had managed to spot the fallen climber, but they saw no signs of life and could not descend to the ground due to poor weather. A ground team reached Dahlmeier’s body later that day, and confirmed that she was deceased. “Based on the severity of her injuries, her death is “presumed to have occurred immediately.” It appears that, due to the dangerous nature of the terrain around the accident site, no body recovery will take place. According to Dahlmeier’s team, it was her “express and written will that in a case like this, no one should risk their life to rescue her. Her wish was to leave her body on the mountain.”

In a subsequent memorial post on her Instagram, her team said that, “Laura enriched the lives of many, including our own, with her warm and straightforward manner. She showed us that it’s worth standing up for your dreams and goals and always staying true to yourself. We are deeply grateful, dear Laura, that we were allowed to share our lives with you. Our shared moments and memories give us the strength and courage to continue on our path.”

Laura Dahlmeier was 31 years old. She held two gold medals from the 2018 Pyeongchang Winter Olympics. She was the first female biathlete in history to win both the sprint and pursuit events at the same Games. She also won 15 World Championships medals over the course of her career, including seven golds. She won five of these gold medals at a single Championships, in 2017, becoming the first women to ever do so.

Dahlmeier retired from the biathlon in 2019, at age 25, to devote herself to alpine climbing full-time. Among other climbing accolades, she holds the female fastest known time on Nepal’s Ama Dablam. She scaled and descended the 22,349-foot mountain in just 12 hours. Since 2023, Dahlmeier had worked as a mountain and ski guide, and was a volunteer for the mountain rescue team in her hometown of Garmisch-Partenkirchen.

The post German Alpinist Laura Dahlmeier Dies From Rockfall in Pakistan appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Conflicting accounts surround a highly publicized link-up in the Swiss Alps and its 21-year-old predecessor.

The post The Definitive Account of an (Utterly Bewildering) Alpine-Climbing Controversy appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

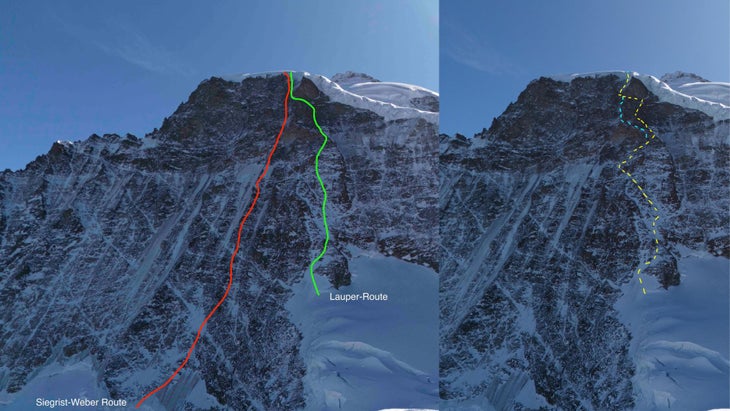

Two alpinists recently set a blistering speed record in the Alps. Maybe.

On April 5, Nicolas Hojac and Philipp Brugger linked the three most iconic north faces in Switzerland’s Bernese Alps—the Eiger (13,015ft), Mönch (13,484ft), and Jungfrau (13,642ft)—in a blazing 15 hours and 30 minutes. Their blitz vastly eclipsed the previous record, 25 hours, set in 2004 by the late Ueli Steck and Stephan Siegrist.

Hojac and Brugger’s effort was meticulously planned, documented, and publicized; both men wore action cameras on their heads, drones buzzed overhead, and camera crews waited on summits. When they started their climb, the pair stood on a glacier in the darkness, staring at synchronized watches on their wrist like bank robbers before a heist: “Three, two, one, go!” Chief sponsor Red Bull churned out a flashy short film, The Fast Line. In it, Hojac pays homage to the original linkup, calling Siegrist and Steck’s feat, “badass.” “Our motivation is not to beat their record, but to finish their project,” he says.

Watch Nicolas Hojac and Philipp Brugger climb sections of the North Face Trilogy project:

When he and Brugger reached the summit of Jungfrau (hugging each other and uttering odd remarks like, “You horn dog, you!”), the world of alpinism applauded. Red Bull’s press remarked that the climbers had “shattered” the 21-year-old record, and other alpine speed demons, from Benjamin Védrines to Dani Arnold to Killian Jornet, offered praise.

But there was an outlier: Stephan Siegrist.

In an email to Red Bull and another sponsor, Mammut, the veteran alpinist cried foul, saying no record had been broken. He called comparisons between the recent climb and his 2004 effort “damaging to the spirit of alpinism.”

Siegrist’s issue? Hojac and Brugger had taken an easier and less committing line—the Lauper Route (M4)—to ascend Jungfrau, instead of the Ypsilon Couloir (M6+) that Siegrist said he and Steck climbed. (Siegrist made the first ascent of this route with Ralf Weber, and in the Swiss Alpine Club’s guidebook it’s referred to as the Siegrist-Weber.) Hojac’s route choice not only made their 2025 climb less technical but, according to Siegrist, was not a true “North Face” route, as it ascended a lower-angle ridgeline. Siegrist said he and Hojac had spoken by phone before the climb, so he could offer the younger alpinist beta. He also wanted to clarify his 2004 lines of ascent, in case Hojac and Brugger intended to try to beat his time. Then, Hojac had deliberately taken the easier line.