Plus, the forthcoming film that will explore the mindset behind the Slovenian climber’s dominance

The post After Double Gold in Seoul and 10 World Championship Wins, Janja Garnbret Shares What’s Next appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Even from thousands of miles away, one thing was obvious: Janja Garnbret wasn’t there to compete. She was there to win.

In the Lead finals at the International Federation of Sport Climbing (IFSC) World Championships in Seoul, South Korea on September 26, Garnbret strung the route together with rhythm, while rivals were bucked off early. The next day, in the Boulder finals, she solved problems that stalled others, moving with a composure that made the crowd feel incidental.

Two events, two golds, one week. This brings the Slovenian prodigy’s total IFSC World Championship gold count to 10, alongside her 47 IFSC World Cup gold medals, two Olympic gold medals, and many more victories.

“Winning one gold at the World Championships is a dream,” Garnbret told Climbing. “Winning my 10th with two in Seoul feels impossible—but here I am. It’s hard to put the emotions into words. I’m just grateful for everyone who believes in me and helps make this possible. It’s always a battle, and I’m proud I proved to myself I could do it again.”

Garnbret’s performance at the International Federation of Sport Climbing (IFSC) World Championships in Seoul, South Korea last weekend wasn’t surprising—dominance has long been her signature. But this sweep felt less like another victory and more like a statement: the ceiling has moved. And as she recently told Magnus Midtbø, she believes she could compete against men—a remark that lands less like bravado and more like a total possibility.

“I was totally in awe of how amazing Janja is under pressure,” said adventure filmmaker Jon Glassberg of Louder Than Eleven productions, who was behind the camera in Seoul. “When she competes, she is there to win and it feels like second place would be ‘losing’ to her. The pressure she puts on herself is crazy, and the other competitors are always chasing her.”

A double gold at a World Championship is virtually unprecedented—no climber before Garnbret has won both Boulder and Lead golds at the same event. Though Garnbret herself pulled off the same feat at the World Championships in Bern, Switzerland in 2023, and in Japan in 2019. Adam Ondra earned golds in Lead and Boulder in two separate 2014 World Championship events (one in Spain, another a month later in Germany), but Garnbret remains the only one to snag double gold in a single World Championship event.

What really sets her victories apart, however, isn’t the medal count, but the assuredness of the performance: control, adaptation, and endurance across two disciplines, rarely mastered in tandem.

“Throughout the event, I was struck by her ability to perform at the highest level in Lead, winning both semifinals and finals,” Glassberg said, “and then the next day doing it all again in Bouldering despite the physical and mental drain of four rounds in 48 hours.”

Each style, Boulder and Lead, expose weakness and demand skill: one is problem-solving at speed, explosive power under the clock; the other, endurance, pacing, and analysis. Most athletes lean into one discipline and accept vulnerability in the other. That’s one reason why the decision to split up these disciplines at the 2028 Olympic Games was welcomed by many climbers. Yet Garnbret showed no weakness in one discipline over the other.

“Each victory has its own weight. People expect me to win now, and carrying that expectation feels heavier every year,” Garnbret reflected after the 2025 World Championships. “First and foremost, I want to prove to myself that I can do it. I know how much I put into training, and I want to show that work on stage. That’s why every win matters—and why I never take any of them for granted. The fans in Seoul and beyond were incredible, and their support meant everything.”

She switched between styles as if their demands were interchangeable. In Lead, she even recovered from a mid-clip slip on a slick right hold. After her composed save, she became the only finalist to top the route. In the Boulder final, the title hinged on the last bloc: Problem 4. She was the only competitor to top out, sealing the gold with a decisive, power-through finish.

What really struck Glassberg was how she dominated every stage of Lead, then came back less than a day later to deliver again in Boulder, pushing through the physical and mental fatigue of four rounds in two days. “It would break most people,” Glassberg said. “But not her.”

Garnbret also competed against a stacked field. The Seoul lineup included: Oriane Bertone, France’s Boulder prodigy, who placed second in Seoul; American Melina Costanza, who took bronze in Boulder; and Seo Chae-hyun, South Korea’s Lead specialist. That’s what made this double gold more than a medal count: It underscored the gap between a climber who can dominate in a lane and one who can finesse her skill across the sport’s stage.

For women’s competition climbing, Garnbret’s double gold is more than a personal triumph—it’s a marker of where the sport is heading. A decade ago, the idea of one athlete mastering both Boulder and Lead on the same stage was improbable. But after her performance in Seoul, this level of mastery feels like the new bar.

If that’s true, what does it mean? Can athletes still afford to specialize? Will training camps shift toward balance instead of bias? How much adaptability can a single season, or a single athlete, flex into?

What’s all but certain is the ripple effect. To younger climbers, Garnbret’s sweep is proof that all-around mastery is possible. To audiences outside the sport, it offers a glimpse of climbing’s complexity—part puzzle, part marathon—and why it deserves its place on the world stage.

As this comp season comes to a close, Garnbret’s calendar next year points toward more World Cups in the lead up to the 2028 Olympics. But she says she’s also excited to do some outdoor climbing: “I have plenty to look forward to, both in climbing and in life. I’ve started projects on rock that I want to finish in the coming months. Competition-wise, we’ll see how the calendar looks and decide how much to enter next season. Taking fewer comps this year was the right call—I needed to reset, focus on rock, and keep that sense of freedom and joy alive in competition, too.”

Currently, Garnbret is also shooting with Glassberg, who is capturing this chapter of her career with Red Bull Studios. The new feature film about Garnbret will show not just the wins, but the mindset behind them. “It should be a very real and vulnerable look into Janja’s life as a climbing superstar and the greatest to ever do the sport,” he said. The film will likely release sometime during the summer of 2028.

Of course, I’ll be watching, whether she turns up on a movie screen or on the Olympic wall. But what stands out to me is how she resonates with more than just climbing die-hards—non-climbers are rooting for her, too.

On Lead in Seoul, Garnbret’s last move told the whole story. She paused just before the crux, just long enough to breathe, shaking out, reading the wall. Then she launched for the dyno, stuck it, and hurried to clip. A flash of calculation followed by pure instinct. This is the balance that defines her climbing—calm when she can be, decisive when she has to be.

The post After Double Gold in Seoul and 10 World Championship Wins, Janja Garnbret Shares What’s Next appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

'Zone Local' has the beta on the best hidden boulders of Fort Tryon, proving that Manhattan's climbing history goes beyond Central Park.

The post These New Maps Reveal New York City’s Underground Bouldering Spots appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

In New York, nature survives by force, not grace—stretching toward the sun, splitting the sidewalk, refusing to yield. Life insists, whether in soil or cement.

Street lamps throw shade beyond the reach of branches. Gutters rush with the same insistence as the Hudson. Brakes and engines layer into a birdsong of their own.

Here, growth is reclamation. And sometimes, it’s louder than the subway.

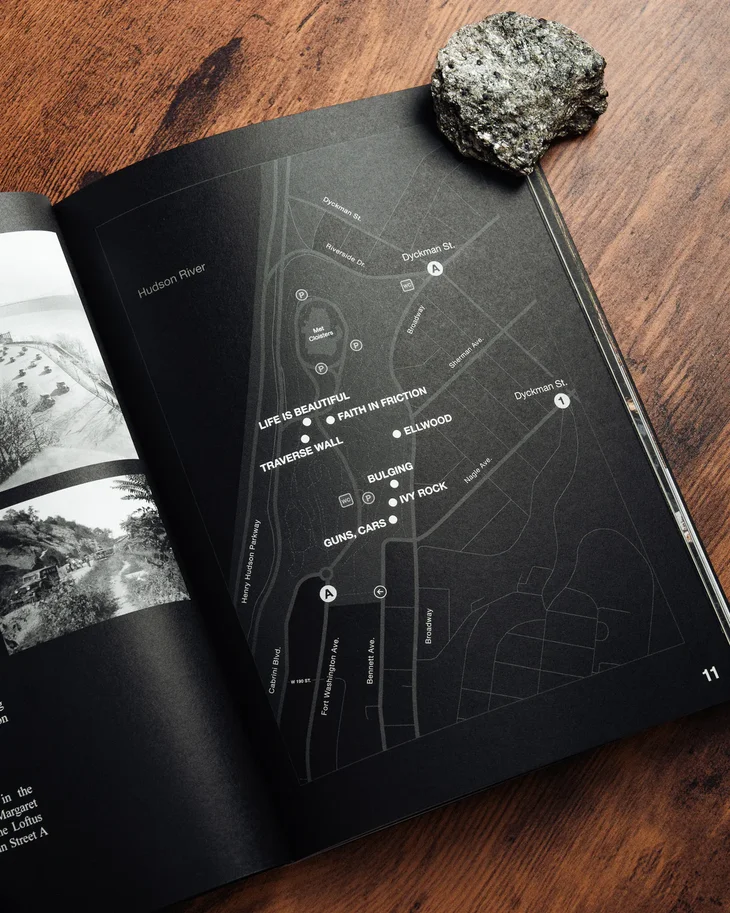

On the northern tip of Manhattan, Fort Tryon is another kind of fracture. One moment you’re on the grid, the A train spitting riders onto 207th. The next, the city thins. Switchback trails climb past stone arches, gardens spill over old walls, and the ground rises into slabs of schist.

For decades, most of the city’s climbers looked elsewhere for their fix: Central Park’s polished boulders or long drives north to the Gunks and Harriman. Fort Tryon’s stone, sharp and unpolished, was documented in earlier guidebooks such as Gaz Leah’s NYC Bouldering and Sam Lerner Dreamer and Conor O’Hale’s New York City Bouldering, but the area received less attention. Many problems were repeated over the years, known mainly to the local climbers who frequented the park.

Now, with Zone Local, climbers Trevor Riley and Rachael Elliott have given them form: a new guidebook equal parts topo, design experiment, and archive. Closer to field notes than a coffee table book, it documents the persistence of climbing in New York—and the community that refused to let it vanish.

For Trevor Riley, Fort Tryon was first a matter of proximity. When he moved to Washington Heights in 2021, the park became his local crag—fifteen minutes on the bus, thirty on foot. “I’m a picky climber,” he says. “Aesthetics matter. Fort Tryon might be the most scenic park in NYC. Central Park doesn’t overlook the Hudson and the Palisades. And the boulders here don’t suffer from as many contrived variations as Central Park’s polished schist. For me, it was hard to beat.”

For Elliott, the pull was slower. A designer by trade, she first climbed in Central Park and up at Powerlinez. But Riley’s enthusiasm carried. “The park is quite arresting in its hidden beauty and how remote it feels although you are still in the city,” she says. “That atmosphere of wonder made me prefer it over Central Park’s boulders, which tend to be more crowded.”

Zone Local reflects those two vantage points: Riley’s eye for climbs that unfolded organically and Elliott’s drive to shape a book that was intentional in both design and use. “It’s a privilege to print something and have it exist in the world,” Elliott says. “We wanted it to matter.”

Making the book required discipline. Photos were the hardest part. “Even though Fort Tryon is scenic, New York doesn’t exactly scream natural beauty,” Riley says. “Getting the right climber on the right boulder in the right light was rare, but necessary: “I wanted the photos to be impressive enough that even climbers from the most incredible places would want to visit.”

Elliott faced the opposite challenge: restraint. “The most difficult part was distilling through the noise and honing in on the important design elements and concepts,” she says. “Collaboration can often be tedious, but it’s almost always worth it in the end.”

The result was a minimalist guide, scaled for use. It can be held open with one hand. It fits neatly into a bag. The cover was given a scuff-resistant coating. Practical choices, but also intentional ones. “We thought guidebooks could be both useful and pretty,” Elliott says.

If the design demanded restraint, the history demanded digging. Riley fell into rabbit holes of Mountain Project threads, defunct blogs from the early 2000s, and even long-dead sites pulled up through the Wayback Machine. Every lead pointed to another—a rumor about a first ascent, a name dropped in a comment, an old website documenting Central Park problems. From there, he started reaching out directly, asking who was still around.

Some were. Climbers who had been pulling on Manhattan schist since the 1980s sat with him and helped fill in pieces of the story. Nicolas Falacci’s early website, Beta-Boy.com, became a touchstone. Ivan Greene’s contributions, like the proud line It’s a Wonderful Life (V11), immortalized in the Reel Rock film Dosage II, surfaced again in memory. Ralph Erenzo, who co-founded the City Climbers Club of New York in 1987 and later helped open two of the earliest climbing gyms in the country, emerged as a key player.

Other stories surprised even Riley: a climbing competition in Central Park in 2011 that drew a crowd of more than 20,000, and the 2008 Dabathon, when climbers, cyclists, and daredevils linked every climbable area in the city into one circuit. During the later, climbers were even chased at one point by police on horseback. “The internet is a messy, endless place to explore,” Riley says. “Once I’d found everything I could online, I started asking locals if certain climbers I’d read about were still around. In the end, it’s insufficient and imperfect. But we hope that the loose ends in our brief overview of NYC’s climbing history lead other climbers down the path of discovery for themselves.”

New York has never been a climbing destination, and maybe that’s the point. No one books a trip to boulder between subway stops. But that doesn’t mean the rock isn’t here—or that the restless need to climb is missing. What Zone Local argues, quietly but firmly, is that local climbing matters, even in a city like this.

“People are often surprised to learn we have climbable boulders in our parks,” Elliott says. “After that, they’re surprised by the variety of grades and the difficulty. Fort Tryon has plenty of project-worthy routes that truly test you.”

Riley agrees, but pushes the thought further. “Climbers will live in Manhattan for years and never climb the classics a couple train stops away,” he says. “I love climbing upstate, but I believe we owe our local zones more love.”

That sense of obligation runs through the book. It isn’t just about wayfinding; it’s about insisting that these places—the overlooked stone in city parks—belong in the story of climbing, too.

In the end, Zone Local feels less like a product than a gesture: proof that climbing in New York has always been a practice of reclamation. The stone resists, the city resists, and still the problems remain.

For Riley and Elliott, the book is both map and memory. It points to where to put your hands and feet, but also to the larger work of building community, preserving space, and telling stories with depth. It insists that climbing in Washington Heights matters—not because it rivals the Gunks, but because it refuses to be overtaken.

Riley hopes that future guidebooks and stories go deeper, that climbers here write more than captions. Elliott hopes more people step outside and touch the rock for themselves.

Zone Local is available for purchase now at zonelocal.net.

And when asked what he’d say to anyone who doubts that bouldering belongs in Manhattan, Riley doesn’t hesitate: “Fuhgeddaboudit.”

This article has been updated to reflect that Fort Tryon boulders are featured in NYC Bouldering by Gaz Leah and New York City Bouldering by Conor O’Hale and Sam Lerner Dreamer.

The post These New Maps Reveal New York City’s Underground Bouldering Spots appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Community leaders weigh in on how you can be an ally at the crag

The post DEI Isn’t Cancelled at the Crag. Here are 10 Ways You Can Show Up for Marginalized Climbers. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

In 2025, we’ve seen Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) efforts swiftly dismantled, reversing years of policies designed to combat discrimination and inequality. With these legislative policies and programs cut, many are now rethinking how to foster inclusion and equality on their own terms.

In the world of climbing, barriers to entry go beyond the physical. Systemic inequality, economic status, access, representation, cultural bias, and more factors shape who gets to climb—and who feels welcome stepping into the sport.

Climbing spoke with community leaders to get some guidance on how everyone can show up and support marginalized communities at the crag right now.

1. Educate yourself about climbing’s DEI challenges

Ignorance is not an excuse. Take the time to understand the challenges faced by underrepresented climbers. Read, listen, and learn about the experiences of BIPOC, LGBTQ+, and adaptive athletes.

Longtime climber and advocate Mariana Mendoza points out that barriers exist on multiple levels: “Some of us experience exclusion in different ways—whether through financial inaccessibility, dismissive attitudes at the crag, or the imagery we’re exposed to that defines who belongs in climbing spaces.”

The first step toward creating meaningful change is taking the time to learn more about some of the major issues—like systemic inequality, economic status, access, representation, and cultural bias—that marginalized communities face. Being thoughtful with whose stories you consume, support, and actively participate in is key.

2. Amplify diverse stories and voices

Representation matters. Use your platform—whether that’s social media, community meetings, or casual conversations—to share the stories and achievements of climbers from diverse backgrounds.

Pro climber Anna Hazelnutt recalls the impact of simply posting about her first ascent in Yosemite: “Seeing another brown girl putting up a new route in Yosemite can shift someone’s mentality—maybe they’ll think, ‘That could be me.’”

3. Support inclusive gear brands

Vote with your dollar. Many outdoor brands support DEI efforts, but some are far more proactive than others. Lou Bank, managing director at Flash Foxy—an organization dedicated to creating spaces and providing resources for women and gender queer climbers—emphasizes the importance of putting money into brands that are investing in accessibility: “Our gear sponsors allow us to offer sliding-scale education programs—without that, we’d be charging three times as much.”

Choosing to support companies—like Arc’teryx, Evolv, Patagonia, and Mountain Hardwear—that are committed to meaningful change and that prioritize inclusive sponsorships, hiring, and outreach can have a ripple effect across the industry.

4. Be an active ally

Allyship is more than a hashtag. If you witness discrimination at the gym or crag, speak up. If you hear a dismissive comment, challenge it. If someone is being left out of belay conversations, redirect the discussion to include them. Inclusion should be an action, not just a sentiment.

“Treat everyone with excitement and kindness,” says Hazelnutt. “Don’t assume what someone is climbing based on how they look.”

Paraclimbing advocate Katy Nelson echoes this: ”Every time someone is excluded, the community is missing out on something potentially great. The cultural idea of creativity, endless problem solving, and the comfort with trial and error, all while focusing on safely having fun, can and will benefit everyone.”

5. Donate to organizations doing the work

Put your money where your values are. Affinity groups and climbing equity organizations rely on funding to provide scholarships, training, and events. There are numerous organizations working to break down barriers in climbing, from mentorship programs to access funds.

I’ve added a list of some of these organizations at the end of this article.

Brittany Leavitt, Director of Brown Girls Climb, emphasizes the impact of financial support. “We’ve seen huge shifts in representation, but maintaining programs requires long-term investment from the community,” she says. “One-time initiatives are not enough. We need long-term investment in BIPOC and queer-led climbing spaces so that accessibility isn’t just a buzzword.”

6. Volunteer your time for these organizations, too

Actions speak louder than words. Volunteer for programs that introduce marginalized groups to climbing or help advance their climbing skills, whether through local gyms, nonprofits, or national organizations.

“The best way to grow representation is exposure,” says Marian May Perez, executive director of Rise Outside, which is dedicated to diversifying the outdoors. “People don’t always know what’s possible until they see someone like them doing it. If you can help facilitate that experience, it’s a game changer.”

They also added that “showing up” can mean mentorship and sharing knowledge, too.

“Exposure is one of the biggest barriers—people need to see climbers who look like them and know that there’s a space for them in the community.” Giving your time helps build the bridges that make climbing more inclusive.

7. Listen and learn about the experiences of others

Mendoza reminds us: “We can’t just invite people to climb without addressing the broader systemic issues that make climbing inaccessible in the first place.”

Marginalized climbers often face subtle and overt exclusion. Nelson says that as an adaptive climber, she often faces micro-aggressions. “People stare, whisper, or assume we’re inspirational just for showing up,” she says. Nelson went on to explain how DEI is an opportunity—not just a “problem” to be solved. She argues that when new people start climbing, they bring something new to the climbing community.

Instead of getting defensive, listen. Rather than assuming what someone is capable of, ask them and listen. Growth requires discomfort, but being willing to challenge your own biases is key to making climbing culture more inclusive.

8. Help promote inclusive climbing environments

A welcoming climbing space isn’t just about who shows up. It’s about who feels like they belong. As Mendoza reminds us, “Climbing doesn’t exist in a vacuum—it’s tied to economic justice, indigenous rights, and racial equity. We need to fight for all of it.”

Bank of Flash Foxy describes how the organization intentionally shifted from a “sending hard” mentality to a “having the most fun” approach: “At a Flash Foxy event, whether you’re climbing V0 or V13, you get the same cheers and support.”

In both indoor and outdoor climbing spaces, do what you can to eliminate gatekeeping, toxic elitism, and assumptions about who “should” be climbing what.

9. Stay informed

DEI work is ongoing. Stay updated on policies affecting outdoor access, pay attention to representation in climbing media, and keep tabs on issues faced by underrepresented climbers. By staying informed, you’ll be empowered to take action when needed.

Mendoza stresses that climbing is not separate from larger societal injustices: “If we want to change climbing culture, we need to advocate for economic justice, free public transportation, and Indigenous rights—because access is about more than just gym fees.”

To remain engaged in the conversation, follow activists, organizations, and outdoor equity advocates.

Bank adds, “We don’t need permission to create the spaces we want to see.”

10. Find your unique way to foster DEI in climbing

Creating a more inclusive climbing community isn’t about checking a box—it’s about shifting culture. Nelson sums it up best: “We’re not here to take over; we’re here to climb just like everyone else. Respect that, and let’s build something better together.”

Supporting affinity groups in climbing means committing to change—not just in words, but in actions. Whether through education, financial support, or simply being a better ally, every effort contributes to a more inclusive and welcoming climbing world.

“If you want these spaces to exist, you have to keep showing up for them,” Bank emphasizes. Whether you do that by supporting an affinity group’s event, mentoring a new climber, or simply being mindful of how you interact with others at the crag, inclusion isn’t passive or a one-time thing. Think about it as an ongoing practice.

Diversity in climbing isn’t a trend—it’s a necessity. By actively supporting and advocating for marginalized climbers, we can create a community that reflects the vast and varied people who love the sport. The crag belongs to all of us. Let’s make sure everyone feels welcome.

Now here’s that list of climbing DEI organizations I promised …

Here are just a few of the many affinity groups and community partners working to make climbing and the outdoors more inclusive and accessible. Learn about their mission, throw them a few dollars, volunteer your time, or just give them a follow. If there’s someone we missed, let us know!

Adaptive Adventures: Brings progressive outdoor adventures to individuals with physical disabilities and their families, regardless of location, equipment needs, or economic status.

Adaptive Climbing Group: Provides affordable climbing experiences for individuals with disabilities, aiming to transform their perspectives.

ASL Climb Network CA: Since 2012, this community group based in Los Angeles has been hosting climb days, events, and monthly meetups for the deaf, hard of hearing, and American Sign Language community.

ASL RocSends: A meetup for deaf climbers who use American Sign Language in Rochester.

Bay Area ASL Climbers: A monthly climbing group on Sundays for climbers who use American Sign Language.

Black Climbers Collective: An adventure community created by Black climbers for Black climbers.

Black Outside: A Texas-based organization dedicated to reconnecting Black, African-American youth to the outdoors.

The Brown Ascenders: Working to increase access, inclusion, and equity within the outdoor industry for Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) communities.

Brown Girls Climb: Facilitates mentorship, provides access, uplifts leadership, and celebrates representation in the outdoors and climbing for People of the Global Majority.

Brothers of Climbing: Seeks to reach, represent, and inspire underrepresented groups within the outdoor community.

Catalyst Sports: Acts as an agent of change in the lives of people with physical disabilities and our communities.

Chicago Adventure Therapy (CAT): Using outdoor adventure sports like paddling, camping, cycling, hiking, and rock climbing, CAT works with Chicago youth to have a lasting positive impact on their communities and become healthy adults.

Climbers of Color: Aims to increase access to climbing for BIPOC.

Climbing for Change: Pro climber Kai Lightner’s organization that facilitates pathways to increase BIPOC representation in the climbing community and the great outdoors.

Colorado ASL Climb: A meetup group at Denver’s The Spot gym for climbers who use American Sign Language.

Crux Climbing: Expands access to the sport of rock climbing and outdoor recreation for LGBTQ communities in the New York metropolitan area and eastern New York.

Diversify Outdoors: A coalition of social media influencers—bloggers, athletes, activists, and entrepreneurs—who share the goal of promoting diversity in outdoor spaces where people of color, 2SLGBTQ+, and other diverse identities have historically been underrepresented.

Earthtone Outside: Elevates the visibility of Montana’s diverse outdoor enthusiasts.

Flash Foxy: Stands with women and gender queer climbers—including trans and gender non-conforming folks—who need a space to pursue their love of the sport without having to deal with historic barriers to access.

G.L.A.M. Climb of Texas: GLAM provides a safe and inclusive space for anyone interested in rock climbing.

Green Latinos: A comunidad of Latino/a/e leaders fighting for political, economic, cultural, and environmental liberation.

Lady Crvsh Crew: A community for ladies who crush beta while empowering each other through climbing.

Latinos Outdoors: Inspires, connects, and engages Latino communities in the outdoors and embraces cultura y familia as part of the outdoor narrative.

Melanin Base Camp: A media company with a powerful voice that plays a major role in normalizing diversity in the outdoors.

Natives Outdoors: A media and consulting company that cultivates the talent of Indigenous communities.

Native Women’s Wilderness: Inspires and raises the voices of Native Women in the Outdoor Realm, encourages a healthy lifestyle within the Wilderness, and provides education of the Ancestral Lands and its People.

Outdoor Afro: Celebrates and inspires Black connections and leadership in nature.

Outdoor Asian: Creates a diverse and inclusive community of Asian and Pacific Islanders in the outdoors.

OUT There Adventures: An adventure education organization committed to fostering positive identity development, individual empowerment and improved quality of life for queer young people through professionally facilitated experiential education activities.

Paradox Sports: Dedicated to transforming lives and communities through adaptive climbing opportunities that defy convention.

Queer Climbing Collective: Hopes to connect the LGBTQIA+ community through their love for climbing and the outdoors.

Queer Crush: Fosters safe spaces for queer, trans, and gender-diverse folx to climb and make friends.

Queer Nature: Focuses on nature-intimacy, naturalist studies, and place-based skills for LGBTQIA+, Two-Spirit, & non-binary people and allies.

Rise Outside: Professional instruction and guided experiences on rock, ice, trail, and anywhere we connect with nature to diversify the outdoors.

ROMP: Ensures access to high-quality prosthetic care for underserved people, improving their mobility and independence.

Sending in Color: Diversifies the Chicago climbing scene, with meetups for People of the Global Majority (PGM).

She Moves Mountains: Creates an inclusive and empowering educational space for all women—including cisgender and transgender individuals—to realize their strengths through outdoor retreats and skills clinics.

Soul Ascension Crew: Empowers existing and beginner climbers of color in Northern California.

Texas Lady Crushers: Provides Texas women, gender non-conforming, and trans individuals education, community, and support to become self-sufficient rock climbers

TranSending 7: Advance transgender rights throughout all aspects of society by promoting athletics as a platform for transgender awareness and inclusion.

Venture Out Project: Leads backpacking and wilderness trips for the queer and transgender community.

The post DEI Isn’t Cancelled at the Crag. Here are 10 Ways You Can Show Up for Marginalized Climbers. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

The landowner cites “the climbers’ sense of entitlement”

The post The Zoo at Red River Gorge Closes Indefinitely appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

For decades, The Zoo at Red River Gorge was a cornerstone of the Southeast’s iconic climbing. This steep, storied crag offers world-class routes that test strength, inspire the community, and carry thousands of personal triumphs and defeats. But as of January 4, its walls stand empty.

Earlier this week, the Red River Gorge Climbers’ Coalition (RRGCC) announced the indefinite closure of The Zoo, prompting reflection on the impermanence of even the most cherished climbing destinations. The fresh “No Trespassing” signs serve as a sobering reminder of the fragility of our community’s access to climbing on private lands.

In a statement posted to Instagram, the RRGCC explains, “This situation highlights why we work so hard to secure land access for climbing—so that we can ensure the long-term preservation of such special places.” The Coalition urges climbers to respect the landowner’s wishes and comply with the closure.

View this post on Instagram

Why The Zoo Closed

As climbers reflect on their connections to The Zoo, for private landowner Brenda Campbell, the decision was clear-cut.

“My property, my decision,” Campbell wrote in a text exchange with Climbing.

Campbell explains her decision as follows: “I closed it because of erosion around the bottom of the cliff, illegal camping, no upkeep on trails, and continued installation of climbing bolts and screws on fragile sandstone cliffs. I resent the climbers’ sense of entitlement—that they can climb anywhere and do anything to private property without permission and leave it a mess. There are plenty of places to climb in this area.”

The RRGCC, however, has expressed hope for renewed dialogue with local landowners to prevent similar closures in the future. The organization acknowledges the challenges of balancing land stewardship with growing demand for safe climbing access.

“These aren’t just crags, they’re someone’s land, and it’s hard to ignore that,” says Billy Simek, RRGCC Executive Director. “You wouldn’t just go to someone’s house and start putting up paintings—why would you bolt routes on land without understanding the regulations? It’s a difficult balance, but we have to make it work.”

The History and Allure of The Zoo

For climbers like Ingrid Miller, the closure feels personal. Miller has been climbing in “the Red,” as it’s known by locals, since she was 12 years old. “The Zoo was one of those places that felt like a rite of passage,” she says. “I’ll always remember my first 5.12 there—that was a big moment for me. For the full-timers out there, I know this will hit them hardest.”

The Zoo’s history as a climbing destination dates back to the 1980s, when local climbers like Pat and John Bachar, as well as some of the early pioneers of sport climbing in the Southeast, developed the first routes on the cliff.

The crag, which had initially attracted climbers for its remote beauty and potential, began to play a vital role in the Southeast climbing community. Local climbers, driven by a passion for exploration and route-setting, continued developing new lines. The Zoo’s routes span a broad range of grades and styles, from easy top-ropes to more challenging sport climbs demanding precision and strength.

“The Zoo has always been this quintessential Red River Gorge crag,” Simek explains, “It’s got everything from beginner-friendly 5.9s to test-piece 5.14s. It’s rare to find a crag with that kind of grade progression and quality routes all in one spot.”

As the years passed, The Zoo became known for its distinct character: the boldness of its routes, the variety of climbing challenges, and the strong sense of community among those who climbed there. Route developers continued expanding the cliff, establishing harder lines and pushing the limits of sport climbing in the region. This growth—carefully chosen and meticulously set—cemented The Zoo’s reputation as a must-climb destination in the Southeast.

But it wasn’t just about adding bolts to rock; it was about building community. Climbers from all over the region would congregate at The Zoo, sharing tips, stories, and techniques, contributing to a vibrant, supportive climbing culture that went on to define the Red.

Growing Pains at Red River Gorge

At Roadside, the crag just across the street from The Zoo, private landowner April Reefer has seen firsthand the explosion of climbing in the Red, as well as its growing pains.

“It’s a constant struggle,” she says. “We’ve worked hard to create a place where climbers can come and enjoy the sport, but it’s not always easy when people don’t respect the land or the landowners.”

Reefer’s restaurant, HOP’s, located at the base of The Zoo, is named for her late husband, a climber who spent countless hours volunteering on trail crews in the Red.

“My husband and I bought the property to keep it maintained and accessible for climbers,” Reefer explains. “We wanted to protect it for the future.”

Managing Roadside has required significant effort, from creating a permit system to funding trail work and volunteer-led maintenance.

Still, overcrowding and parking challenges persist.

“If you go somewhere and the parking lot is full, find another place to climb,” Reefer advises. “People need to understand they’re on someone else’s land and act respectfully.”

For climbers like Reefer and Miller, The Zoo closure represents more than just the loss of a climbing destination—it’s a stark reminder of the greater responsibility the climbing community has to preserve the very places they love.

Protecting Climbing Access Through Stewardship

In recent years, climbing access has been increasingly threatened across the country. Crags in places like the Pacific Northwest and Sierra Nevada have also seen closures or restrictions due to landowner concerns, environmental impact, and the growing popularity of outdoor recreation.

“Every time you went up to the Zoo, you could see the trail degrading rapidly—at some point, it was bound to require maintenance,” Simek reflects. “It’s a reminder to all of us to think bigger picture about where we’re climbing and who owns the land.”

The Red River Gorge is not alone in facing these challenges, but it serves as a pivotal example of how urgent the need for responsible stewardship has become. As the RRGCC engages with landowners to find solutions, climbers will have to reconcile their love for outdoor adventure with a deeper understanding of the importance of preservation and mutual respect.

“It’s about more than just climbing,” Simek says. “It’s about making sure we have places to climb in the future. If we don’t protect these areas now, they won’t be here further down the line.”

While the loss stings, it’s also igniting important conversations about long-term solutions—most notably, climber-owned land.

Is Climber-Owned Land the Answer?

Daniel Dunn, Southeast Regional Director for the Access Fund, sees climber-owned land as one of the most effective ways to secure access and protect climbing areas.

“Climber-owned preserves are the gold standard for ensuring access,” Dunn explains. “They’re not just about climbing—they’re about conservation and creating spaces where the community can thrive without worrying about sudden closures.”

One of the best examples of this strategy is just down the road from The Zoo. Over the years, the RRGCC has acquired several key climbing areas, including the Pendergrass-Murray Recreational Preserve, the Bald Rock Recreational Preserve, and the Miller Fork Recreational Preserve. These areas, which encompass hundreds of routes and acres of forest, are protected by conservation easements held by the Access Fund.

“The Red’s climber-owned lands aren’t just rock walls—they’re ecosystems,” Dunn says. “By purchasing these tracts, climbers are also preserving wildlife, preventing development, and ensuring that these areas remain intact for generations.”

Dunn emphasizes how climber-owned land offers a level of security that handshake agreements with private landowners often cannot. In the case of The Zoo, “no formal agreement was in place,” he explained.

While climber-owned land offers a promising path forward, Dunn cautions that stewardship remains essential, even in protected areas.

“We have to be good stewards everywhere we climb,” he says. “That means respecting landowners, minimizing our impact, and supporting the organizations working to secure access. These efforts require time, money, and community support.”

For Dunn and others at the Access Fund, the loss of The Zoo underscores the urgency of securing more climber-owned land and educating the community about its benefits.

“Climbing’s popularity is exploding, and with that comes growing pains,” he says. “But it’s also an opportunity to build a stronger foundation for the future. Climber-owned land is how we ensure these places remain open—not just for us, but for everyone who comes after.”

The Zoo may be closed for now, but the lessons learned through its closure will serve as a crucial turning point in the future of climbing access in the Gorge—and beyond.

This is a developing story that will be updated as new information becomes available.

The post The Zoo at Red River Gorge Closes Indefinitely appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

At Boyce Bouldering Park, you don’t need a pricey membership or an exhaustive gear list to send—all it takes is grit and a pair of sneakers.

The post Pittsburgh Newest Bouldering Gym Is in a Public Park—and It’s Free appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Last month, Allegheny County opened Boyce Bouldering Park—a 6,000-square-foot expanse of artificial boulders. Carved into the edge of Pittsburgh’s urban sprawl—just fifteen minutes from downtown—this free outdoor bouldering gym was designed with an ambitious vision: to bring outdoor adventure to all.

The park boasts more than 100 problems, ranging in difficulty from VB to V10+, which will be reset twice a year by professional setters. It is part of a $4.7 million project inspired by a 2020 Pennsylvania Environmental Council (PEC) study, which highlighted a significant lack of accessible outdoor recreation in and around Pittsburgh. To address this need, planners chose to create a bouldering park and nearby pump track, paired with upgraded restrooms and other park facilities, aiming to foster a sense of community and adventure close to home.

From start to finish, the park revitalization project was designed with climbers in mind—but Dean Privett, a local gym owner, consultant, and longtime setter, did more to shape the park’s climbing functionality than anyone else.

Privett has been in the climbing industry for more than 13 years, designing climbing facilities worldwide, including one of his own in Pittsburgh. When he heard that Allegheny County had plans to build a free climbing-oriented outdoor park, he picked up the phone and got into the right room.

It was a good thing he did.

Lacking climbing expertise, the county was planning to install a 30-foot climbing tower with autobelays. But, in an 11th hour meeting, Privett convinced them that bouldering was a safer, more accessible, more affordable, and more climber-friendly alternative.

We aren’t motivated by profit; we’re motivated by getting folks outside.

“I knew I wanted to make sure whatever got built was as functional as possible,” he told Climbing. “Architect-led artificial climbing wall constructions tend to be more in the miss column than the hit column with true avid indoor and outdoor rock climbers.” His company, Boulder Solutions, ultimately consulted on the project—constructing walls with ambitious, progress-oriented setting at the forefront of the design. By prioritizing wall shapes that support varied movement and difficulty, the wall design itself ensured that a dedicated team of setters could regularly rotate problems.

Privett and Allegheny County plan to update the routes at Boyce twice a year, aiming to keep the space fresh and challenging for climbers of all skill levels.

For Privett, this approach was crucial.

“I wanted to create a range of routes that catered to the existing climbing community and also welcomed the ‘stumble-up’ climber,” he said. “With the outdoor design, we could control that experience through the wall shapes and by balancing slabs with overhangs.”

The park currently boasts over 100 new climbs, ranging from the smaller, kid-oriented “June Boulder”—named after Privett’s daughter—to a V10+ set by IFSC World Cup route setter Chris LoCrasto. Setters from GP81, Movement, The Rockmill, Blue Swan Boulders, and the former director of setting for the Cliffs, also contributed to the park’s initial setting.

“My goal was to provide Pittsburgh with a diverse palette of climbs from incredibly experienced setters,” Privett said. “So we set in a traditional commercial climbing gym methodology, maybe with a slight emphasis on fun over difficulty; we wanted to have things up there that would challenge people so they would come back.”

“My philosophy here was really to introduce people to it as physical problem-solving and not as a physical challenge,” he added, “to hopefully create that hook-line-and-sinker feel of having an enjoyment for solving a puzzle.”

His plan is working. On a recent visit to BBP, he heard a young girl, wearing sneakers, ask her parents to put climbing shoes on her Christmas list.

“There’s a bit of a mentorship barrier that’s been true of traditional rock climbing,” Privett said. “But here, there’s a nice crossover [between communities]. When climbing is in the public sphere, and in public spaces—it’s easier for people to give it a try.”

Since Boyce is within the jurisdiction of Allegheny County Parks, the challenges that traditional gyms face with liability insurance were minimal—it’s generally accepted that public areas operate with a “use at your own risk” legal structure.

“Within commercial climbing gyms, there’s a lot of liability that we’re obviously exposed to, but parks operate in a different realm,” Privett said. “There are federal laws that protect them. They have tolerances for those types of activities—and that allowed the upkeep and route setting to be a part of the overall budget.”

All of that allows the park to serve its primary goal: making outdoor recreation in Pittsburgh accessible to underserved communities.

“The climbing work is emblematic of that,” said Brett Hollern, Vice President for the PEC Western Pennsylvania Central Region. “So how does somebody without transportation, without equipment, having never done this before, how do they even approach recreating outdoors or climbing? We bring that experience to them.”

Privett echoed the sentiment: “In places like Pittsburgh, it’s just much less common to think about climbing as an activity that you would or could want to do. But our industry could benefit from more awareness around what climbing is. It’s all of our job to educate and introduce people to it.”

Hollern hopes that the Boyce Bouldering Park model can inspire other municipalities to consider climbing in their park budgets. “We operate on the premise that people who recreate on public lands will, in turn, become stewards of those lands. Outdoor spaces like this can activate communities, whether through economic development or quality of life, and Allegheny County really took that idea and ran with it.”

Joe Perkovich, the Allegheny County Landscape Architect who supported the project, said the proposal’s non-existent barrier to entry was a key reason for the county parks service involvement. “All of our parks are publicly funded assets and are there for people to use and enjoy,” he continued. “We aren’t motivated by profit; we’re motivated by getting folks outside.”

For most, the bouldering park is just another addition to Pittsburgh’s growing outdoor scene—but it’s a game-changer for advocates and climbers like Privett. It’s a space where the barriers to entry are lowered, and anyone, regardless of background or experience, can step up, fall down, and fall in love with the sport.

The post Pittsburgh Newest Bouldering Gym Is in a Public Park—and It’s Free appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

A Melbourne-based climber has a new vision for gym holds: art that climbs like rock.

The post You Should Definitely Touch This Painting appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

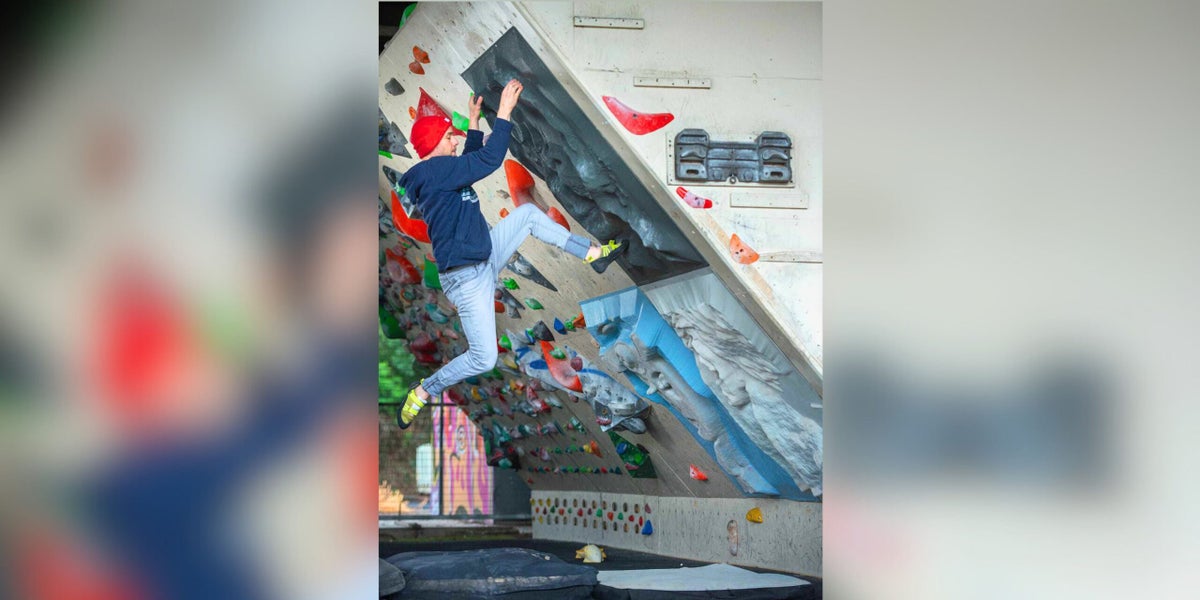

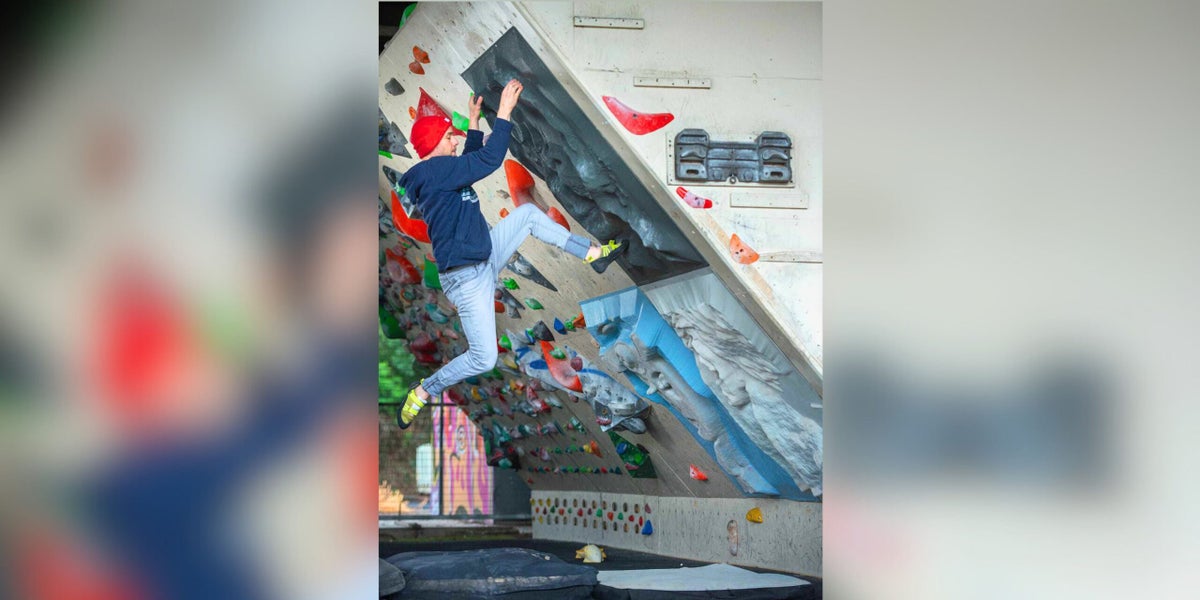

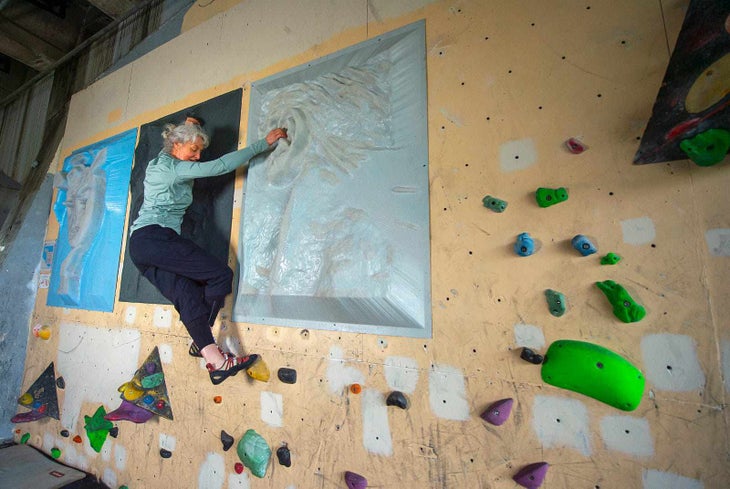

While Stu Beekmeyer was at home recovering from a life-altering and traumatic brain injury, he felt like he was “putting a solid dent in his couch.” The life-long climber was suddenly at a standstill, faced with an impossible choice: he could, in his own words, “sit at home and watch Netflix for two years,” or find a way to “regain his focus.” And after weeks of scrolling through the climbing-corner of Instagram, skipping past oversaturated sunset pics and flashy comp boulders, he came up with a way to reconnect with his sport—through art, through others, and through designing climbing holds fit for a museum.

His project, Bouldergeist, represents a groundbreaking endeavor that fuses bouldering and art, going beyond traditional gym holds to mimic the movement of outdoor climbing in an indoor setting. Climbing caught up with Beekmeyer to learn more.

Climbing: So what is Bouldergeist, and how did it start?

Beekmeyer: I think of Bouldergeist as art that climbs like rock. When I was a landscape architect, my entire business model was to try and steal public art budgets to put up climbing walls in public spaces. And I was looking for a way to go out and scan actual boulders to use as holds, and I couldn’t really afford to do it, so I scanned a head of lettuce. And I started looking at it and thinking: “There’s some seriously good climbing in this.” I don’t think climbers care what they are climbing as long as you can climb it and it climbs well—so why not climb a lettuce? Why not climb a painting?

Because I couldn’t climb for a year and a half, this project gave me a really nice connection with climbing, and the climbing world internationally, that I probably wouldn’t have gotten if I didn’t become sick—which is really, really ironic.

Climbing: Tell me about the business side of things. How is this project funded?

Beekmeyer: At the moment, I’m self-funding but in the next year will be looking for smart investment. Right now, the focus has been testing ideas and getting prototypes together. I’m about to launch the bouldering holds at Vertical Pro in Germany at the end of November with Banana Volumes and have the beginnings of a production partnership in Germany. Once we start getting the holds out, this idea is scalable between the gym, public sculpture and even the art gallery, so there’s lots of room to grow and to refresh.

Climbing: How do your holds differ from regular gym holds, and what can they add from a performance perspective?

Beekmeyer: With nature, we have to discover climbing. You have to go out and you gotta find the places that you’re projecting—and not all rocks are good for climbing. And, in the middle of all that, you’re trying to find one incredible line to the top. With artificial climbing, I see it more as choreography, like ballet, so ironically, the experience of what I’m making is actually more like climbing real rock—you have to search for the holds and challenge yourself to think and move differently.

Climbing: What’s it been like for you to see your vision start to come to life? How has the public response been?

Beekmeyer: It’s been incredible. I think people really engage with climbing art, not just the forms, but the subtleties of the brush strokes as well. I don’t want to sound like a hippy, but I think if you’re putting out something unique and creative the right people will respond. It’s like finding climbing partners, I guess—there’s a Zen to every partnership.

Climbing: What is your long-term vision for Bouldergeist?

Beekmeyer: I’d love to have climbable sculptures in big cities. One of my favorite things about climbing is the random people you meet on a constant basis, and who make you feel like the world’s a better place because you’ve just had this random chat. That’s the only thing I ever really wanted to bring into the discipline of landscape architecture, because as the world is getting more expensive, I just think public space is just really important, especially in cities, and I believe climbing should be a key part of that.

[This interview was lightly edited for clarity. —Ed.]

The post You Should Definitely Touch This Painting appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Sunna Shinn went from fundamentalist Baptist teacher to nonbinary climbing TikTok influencer in five years. As they learned to climb, they learned to embrace their queerness.

The post How Climbing Transformed This Fundamentalist Baptist Into a Nonbinary Influencer appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

This story, originally titled “Climbing Beyond the Binary,” appeared in our 2024 print edition of Ascent. You can buy a copy of the magazine here.

Sunna Shinn started climbing on a dark day. Their bones were heavy, their mind was fogged over, and even the familiar mechanics of breathing were strained. They felt like they had a slim chance at a new life. Like the world had already made up its mind about them.

It was 2018, five years after starting seminary school and a year after moving to Brooklyn to step away from the Independent Fundamentalist Baptist Church, in which God dictated every movement and every moment.

“I was coming from a place where I felt a lot of external ideas and pressure about what people thought of me,” they told me during our first interview last October. That pressure had become too much, too sinister—heavy, thick, and insurmountable. And yet, somehow, on an average Bushwick morning, they pried themselves from their bedsheets to face another day. Far from home. Far from their family. Far from their church. Far from the little apartment on Avenue Q, deep in Brooklyn, where, just six months earlier, they’d thrown away their mother’s last prescription and witnessed her last breath.

They went to the gym on a friend’s recommendation, but their first day felt, in many ways, like yet another defeat. They searched for strength, for balance, for mindfulness, for a purpose, for some motivation—and instead found a challenge. Even the V0’s were hard. But despite their aching forearms, Shinn came back the next week. And the next. The movement offered something new outside of the church, their home life, and their expanding grief. What started as a few taxing hours of gravity and grit became a calling. The routes became a map to self-discovery.

“I felt like a kid again, like I was climbing trees,” they say. “I started to think about what my body was doing, which let me start to question things, and I pursued that ideology in other parts of my life.”

Now, after five years in the sport, Sunna Shinn identifies as nonbinary, embracing they/she/he pronouns. Climbing, which began as a means of escape, has become a celebration of their body outside the confines of the gender binary: a way of exploring the intricate topographies of self-expression and inspiring others—both as a coach and one of climbing’s biggest queer TikTok influencers—while simultaneously confronting their cultlike religious upbringing.

As a young person, Shinn, now 30, was “isolated and lost.” They were raised in a small Baptist neighborhood in Jackson, New Jersey—the type of place where missing Sunday service was whispered about. Their local branch of the Independent Fundamentalist Baptist Church was the backbone of who they knew, what they valued, and who they thought they were supposed to be. “It was very much a small bubble,” says Shinn. “And because of that, my entire life was mapped out. I lived at church seven days a week.”

Days unfolded in a structured rhythm, a chain of rituals—homeschool, outdated VHS tapes, a uniform of starched shirts and pleated slacks for the men and long, modest dresses for the women—designed to mold minds toward a singular purpose. From an early age, Shinn noticed a weight to the conformity that surrounded them.

“Everything I learned was within a certain narrative. It was all very much aligned with our beliefs,” they say. “I was surrounded by the same people all the time and invested in the lives of everyone around me, because we were in this ‘family’ together. I was programmed not to question things.”

But there were things to question. Their clothes never seemed to fit right—and neither did the schooling, teachers, parents, science classes, or endless sermons. Eventually, their nonstop obedience, once a testament to devotion, began to weigh heavy. Growing up, they’d never heard of a nonbinary person. But they knew homosexuality was a sin.

“That’s the thing about my own journey with queerness,” says Shinn. “Because I was in that space, I had no exposure to it. They were so adamantly against it. Every time I considered that myself, I just shoved it down.”

I planned to meet Shinn at VITAL, a climbing gym in Brooklyn, at 11 a.m. on a rainy October morning. By the time I arrived, Shinn was already warmed up—thin, sinewy, and sculpted from five years of bouldering.

Shinn knows that most people look at them and assume they are a man. They are lanky and shy with impossible cheekbones and small wire-rimmed glasses. Muscular, squared shoulders bear a flat chest and a pink sports bra. A small patch of stubble rests on their upper lip. Their hair is long and wispy, and it remains impeccably in place even while they climb. But regardless of gendered assumptions, Shinn just wants to be known as “someone that makes you smile to think about.”

In both their online presence and their work as a climbing instructor at a local NYC gym, Shinn challenges conventional representations of what a climber looks like, creating safe, inclusive communities rooted in strength, creativity, and queer joy.

For Shinn, climbing is an artistry of form and function, a way to embrace both feminine strength and masculine grace according to each problem’s demands. This novel approach has helped them to amass nearly 40,000 followers on TikTok, a platform they use to foster the queer climbing community in New York City and gyms across the country. They do this by sharing videos that normalize queer bodies in movement and that challenge conventional ideas of strength.

We settled on trying a tricky blue V6 that required a long reach and the right blend of tension and crimp strength. With a quiet intensity, they began up the problem, their fingers tentatively exploring its tactile code like a pianist searching for their first note. After they climbed it, I asked them who they were wearing.

“Muscle mommy,” Shinn said, with a term often used in reference to women weight lifters. “Growing up as male is a much different experience than growing up as female, because society views body weight and strength differently. So for me, when it comes to presenting strength, it’s fun. And I mean, the muscle mommies paved the way.”

They talked enthusiastically, stretching their fingers between problems and questions, admitting they never expected to build a following online. At first, social media was simply a tool for them to connect with other queer climbers, to find a community of people who enjoyed “just being human together.” Then they began to notice a gap.

“Along the same timeline as my climbing, I started to explore my gender and identity,” they went on. “So the purpose of climbing and the social media presence was to connect with more people who identify how I identify, and to be the kind of role model I was looking for when I started out.”

Shinn says that climbing naturally lends itself to building community, and as an instructor, they teach life skills, conflict resolution, stress management, and relationship-building alongside more typical technical skills and safety requirements. They’re also quick to tell you it’s a chance to goof around, have fun, and take some pressure off the day-to-day.

“With climbing, you’re depending on one another,” they told me, massaging chalk between their fingers. “You’re building trust in a very physical way.”

Still, being online has had challenges—negativity and hate tend to litter Shinn’s comment section.

“I try to ignore it, and honestly, I don’t have the emotional capacity to fight back at this point,” they said. “It’s something I’m working on, but right now, I’m just allowing myself to keep my distance. Unfortunately, I think that’s the price of being visibly queer online.”

With a subtle, practiced motion, they pushed their glasses up their nose and refocused their gaze on the boulder in front of us.

“In New York, there’s a lot of diversity, but online, there’s another facet of that. I connect with a lot more people in sparsely populated areas, so being able to do that makes me feel very special,” they said. “Because of my background and because of how limited my exposure was, I wasn’t able to meet anyone who defied any social norm of any kind. Honestly, climbing was a way to recover my truth.”

Days as a child in the Open Door Bible Baptist Community were structured around service, each flowing predictably into the next like pages in a dog-eared hymnbook. The church was a sanctuary, not only of worship but of shared purpose, a place where Shinn sought meaning through faith. Within this, they were often at odds with their mother, who, Shinn says, “never understood or supported what I stood for.” Small things, like carrying their books in a “feminine” way or being “softer around the edges,” were scrutinized.

At 20, they moved to a stoic, whitewashed Independent Baptist seminary school in Lancaster, California. It was desolate and deliberately in the middle of the desert.

Seminary life demanded conformity, a strict adherence to the prescribed doctrines that left little room for introspection. There, dogma wrestled with self-discovery. Days were spent in silent prayer and nights in silent unease.

“Any thought that deviated was considered bad and your fault. I never wanted to be ‘wondering’ wrong,” says Shinn. “So I did everything I could to make sure that everything within me aligned with what He believed, and what His plan was for me.”

But they gradually realized that the chapel’s sobering exterior mirrored the harsh convictions inside—that though the seminary was a place where the sacred and earthly intertwined, it wasn’t one that saw Shinn’s beauty as part of its natural extension.

This realization ultimately led to the difficult decision to leave the church in 2017, and later, it allowed Shinn to stare down their wardrobe and look for pieces that hung differently, flowed easily, and dared to challenge the contours of the “masculine” frame they were born into.

“Having grown up with older siblings, I became familiar with how clothing would feel a bit too big when I was younger and a bit too small as I continued to grow,” they say. “This body, also a hand-me-down of sorts, was always something that I thought I’d grow into. But I’ve learned that life is a lot less about fitting in and a lot more about making things fit.”

Later still, it meant picking through their morals to decipher what was fundamentally theirs and what was fundamentally Baptist.

But before they could do this, the phone rang. Shinn’s mother, Tan Thai, had stomach cancer.

Thai, a woman of immense tenacity, had fled war-torn Vietnam, seeking refuge in a cramped Brooklyn apartment on Avenue H. All nine of her siblings piled in, huddled side by side on the damp floor during their first frigid New York winter. They slept, sweat, and shivered together, trading the familiar green of Vietnam for a few lonely trees watered by an overflowing storm drain. Thai quickly learned English and worked tirelessly as a telecommunications professional in two time zones, starting her own business and napping between work calls. She met her husband, Kee Shinn, at a Fundamentalist Baptist service. The church quickly became the bedrock of her new American life—a kind, family-focused community she’d not otherwise found in her new country.

But for Sunna Shinn, the church held a host of conflicting duties, identity, and pride—and their relationship to their mother was complicated, painful, and always in flux. “Being a child, and watching your family work so hard for you to have a better life—you try and live up to all of that sacrifice, that debt they’ve acquired for you, and you ask yourself if it’s morally right or wrong to do the things you want.”

Caring for their mother so soon after they left seminary was difficult, Shinn recalls. “I felt an immense responsibility, knowing how hard she had worked, and how much she sacrificed for me her whole life.”

In those last days of Thai’s cancer, Sunna filled prescriptions, changed bedsheets, and helped their mother to and from the cramped shower, up and down narrow flights of stairs, across subway platforms and busy sidewalks. Loss felt heavy, desolate, permanent—and on its way. “Seeing someone you care about losing their lifeforce in front of you… It was one of the most difficult experiences I’ve gone through,” they say.

When their mother ultimately passed, Shinn grappled with the life they’d led, the people they’d loved, and the lonely space ahead. Their once-unwavering belief system finally unraveled.

Back in the gym in Brooklyn, a comfortable silence settled between us. With one eye on a new problem and the other on the crowd nearby, Shinn told me that climbing, in many ways, allowed them to celebrate their physical form in a way they hadn’t known they needed. “When it comes to gender and climbing, really, I am the source. The internal drives the external,” they said. “There’s something really beautiful and simple about that.”

I was still stuck on that first blue V6—and, hopping up to the first crimp, I was quickly bucked off.

They urged me to find the flow, to move through the problem with balance. Between the adrenaline and the sweat, I reached up, searching for enough slope in the hold to press my weight into, acutely aware of my fingernails digging into the harsh plastic. And then, as swiftly as I found the balance point, I slipped off.

But Shinn approached my failure with patience and empathy, like any good teacher. “Work with it, not against it,” they assured me.

The sport, according to Shinn, is a great metaphor for this. When you climb, the dichotomy of masculinity and femininity dissolves. The weight of each is narrowed into smaller movements and challenged by subtle shifts and focused precision. Here, progress is earned through effort and determination. Here, the precipice of fear meets the precipice of achievement. Each boulder problem carries with it the potential for triumph or defeat, and within this contained world, there is solace in the simplicity of that struggle. At climbing’s core, there’s also a great deal of fun—a place to enjoy movement, to share intimate moments with friends, and to goof around. In confronting insecure terrain then, what truly matters is not the label you wear but the fluidity with which you adapt, evolve, and, ultimately, solve the problems that beckon you.

“The gender euphoria I experience comes from simply being in my body,” they told me, their lips curling into a quiet, knowing smile. The same one, I imagine, that drives their daily communion with resilience.

To read more from Ascent, visit our table of contents here.

The post How Climbing Transformed This Fundamentalist Baptist Into a Nonbinary Influencer appeared first on Climbing.

]]>