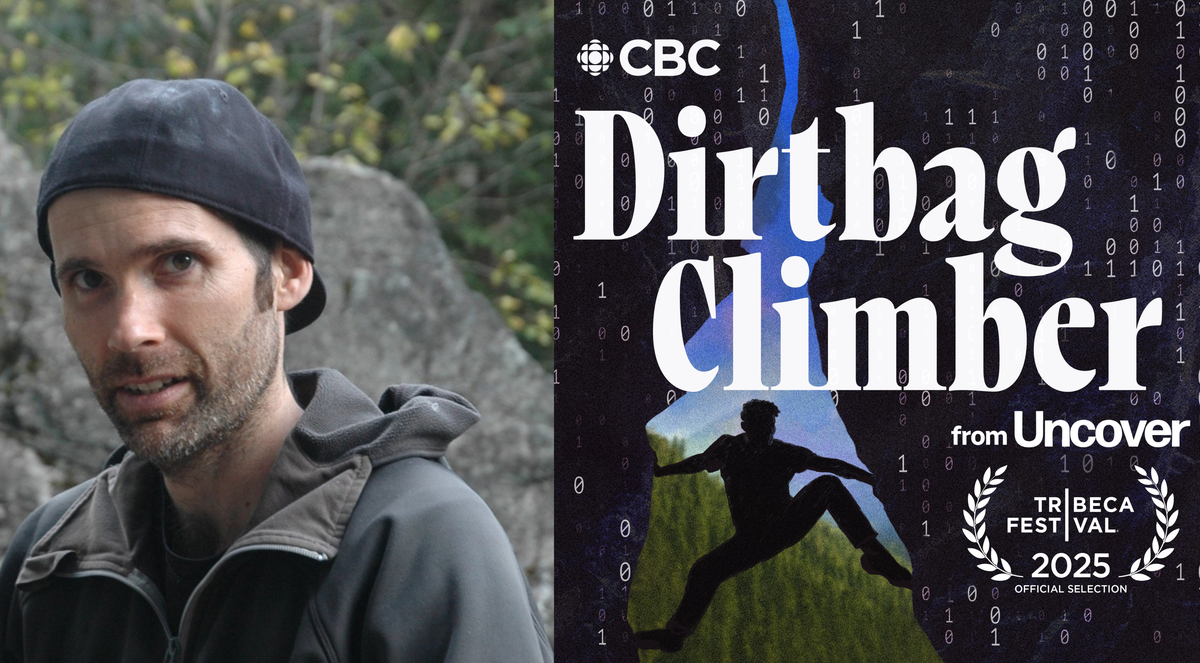

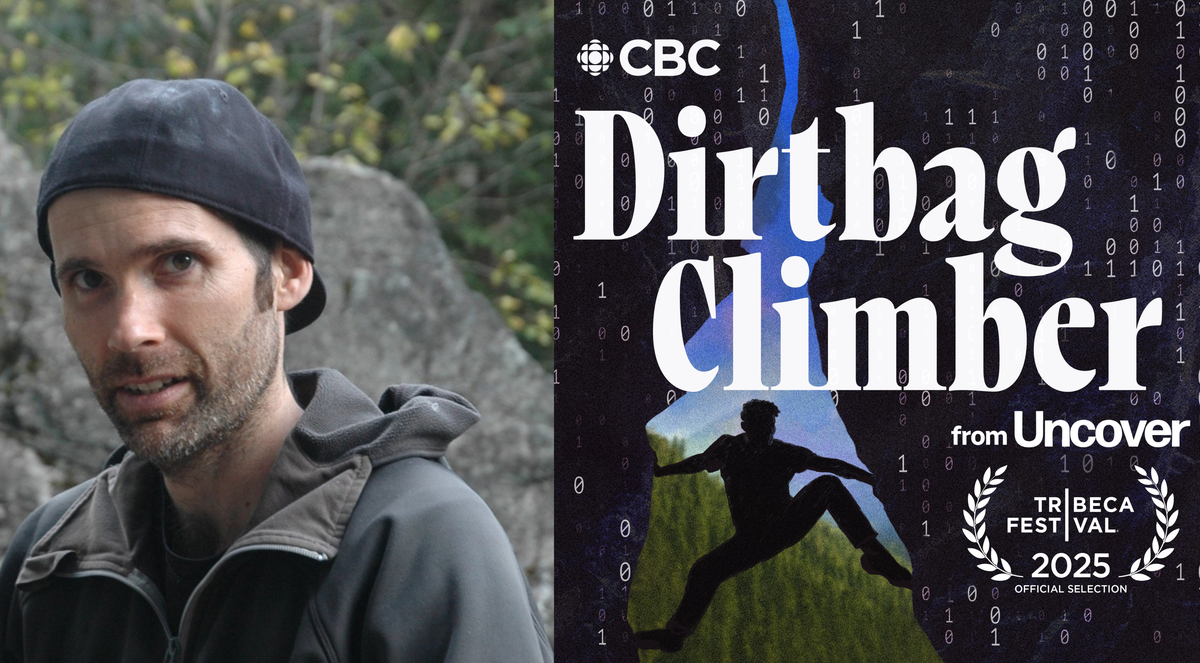

We interviewed the host of 'Dirtbag Climber,' a new podcast that explores the bewildering life and death of a climber who went by Jesse James in his final years.

The post A Squamish Climber Was Murdered in 2017. Now, Another Local Climber Searches for Answers. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Steven Chua had been working as a reporter for the Squamish Chief for only a month or two when he received a press release about a body found at the Cat Lake Recreation Site in Squamish, British Columbia. Chua had just moved to town, and anticipated the “bread and butter” of community reporting: school board meetings and small-town sports. He hadn’t expected to hear about the discovery of a charred SUV at the Cat Lake site on the morning of June 14, 2017, with a local climber known as Jesse James inside—killed by gunshot.

“Things are a lot less sleepy here than I thought,” Chua remembers thinking at the time.

It became clear that “Jesse James” was likely a pseudonym. But the man’s real name—or at least his legal name at the time of his murder—would take another three years to figure out. In 2020, police revealed that they had found that legal name: Davis Wolfgang Hawke. And with the name came a trail of dark, bizarre past lives, heavily publicized for the havoc they wrought.

Davis Wolfgang Hawke, the neo-Nazi

Chua’s reporting on Jesse James eventually led to Dirtbag Climber, a new podcast from CBC’s Uncover series. As the host of Dirtbag Climber, Chua retraces James’s history as Davis Wolfgang Hawke, from his upbringing in Westwood, Massachusetts, to his college years in South Carolina in the late 1990s. At age 20, Hawke caused a stir at Wofford College—and in the national news—for his grassroots organizing as a neo-Nazi. Hawke ran the Knights of Freedom website with a paid membership system, outfitted his dorm room with swastikas and Mein Kampf, and attempted to enact a plan for American history’s largest white nationalism rally.

Dave Bridger, the “Spam King”

Hawke’s movement lost steam, however, when the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Intelligence Report exposed his birth name: Andrew Britt Greenbaum, of Jewish lineage. That revelation turned hate group ire back onto Greenbaum and forced him to shed his neo-Nazi persona. But he immediately found a new one: Dave Bridger, “Spam King.” At the advent of spamming, Hawke-slash-Greenbaum-slash-Bridger’s company, Amazing Internet Products, bombarded millions of Americans with emails to trick a tiny percentage of them into buying junk products, including “herbal penis enlargement pills.”

Jesse James, the Squamish dirtbag

Greenbaum had to abandon this hustle when he was hit with a $12 million dollar lawsuit for buying a list of 90 million email addresses illicitly leaked from inside AOL. He fled internationally to avoid paying it. And then, in 2009, he reemerged “in his final form,” as Chua puts it in Dirtbag Climber: Jesse James, the rock climber and online troll who lived out of his truck. James would become known to the Squamish climbing community for ranting about routes and calling pro climbers “mutants” online. Yet at the crag, he showed a friendly, helpful side to new climbers and old friends.

As Chua works to peel back the layers of each of Jesse James’s past personas in the podcast, he makes one thing clear: James had made plenty of enemies in his 38 years. But Chua’s pondering of who may have murdered James is not the most interesting part of Dirtbag Climber. It’s the discovery of a boy, then a man, driven by the desire for money, authority, and most of all, influence. Dirtbag Climber depicts Jesse James as an early online influencer who toyed with now-prescient subjects a decade before they’d spread all over social media, including white nationalism, tech-savvy scamming, red pilling and the manosphere—even biohacking.

Listen to episode 1 of Dirtbag Climber

Chua caught up with Climbing ahead of the release of Dirtbag Climber’s final episode on podcast platforms on October 6 (though you can listen to all five episodes now on CBC’s Youtube channel). He shares how he used his own experience as a Squamish climber to further crack the story open, and the question that nagged him as he reported on it: How many of us are climbing with a Jesse?

Our interview with Steven Chua of Dirtbag Climber

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Climbing: First off, which name do you choose to call the subject of Dirtbag Climber?

Steven Chua: We’ll just call him Jesse. We’ll keep it simple that way.

Climbing: Take us back to when you first found out about the murder. What were the initial facts?

Chua: The initial picture we got was: this guy called Jesse passed away. There wasn’t anyone who was willing to talk to us about him on the record. We knew by word of mouth that it was 99 percent certain that he was killed, but no one was willing to go on the record and confirm it for us. So we held back on reporting it. The Davis Wolfgang Hawke stuff was still lightyears away at that point. We saw that on his Facebook page, there were a bunch of RIPs. Those were written by people who were on better terms with him. It seemed typical: “It’s a shame this guy got killed.”

Climbing: What impression did you get of him from early conversations with local climbers?

Chua: There were people who thought he was a nice, caring dude. But from all the folks I’ve talked to, it didn’t seem like anyone really knew about his past, aside from the fact that he was evasive about it. As people tried to ask him more about it, he kept on stuffing those questions down. They sort of accepted that.

I haven’t spent a lot of time in other climbing communities, but in Squamish, some people adopt a character in their climbing. You’ll hear about people with larger-than-life names like King Can Al and Heavy Duty. It’s just what people call them and that’s how they’re known around town. You’re just like, “Okay, that’s who they are.” Whether or not they’ll choose to share more personal details, you don’t know. A lot of people just accept it.

Climbing: Once Jesse’s previous name, Davis Wolfgang Hawke, was revealed, what did you set out to learn as a reporter for the Squamish newspaper?

Chua: A lot of the Neo-nazi stuff and the spamming stuff—that was stuff that you didn’t necessarily need local connections to report on. It was out there. So the way that we tried to add our own, different take on that story was to examine those things within the Squamish context. How could someone with this kind of past—as a very controversial, very public figure—adapt to life in Squamish and carve out a life for himself here? What did he do here? That was the different kind of value we could add, because we had that ability to tap into the community and get those bits and pieces that were harder for reporters who were just parachuting in to get.

Climbing: You shared in the podcast that you were able to do that in part because you’re a local climber yourself. Tell me more about your climbing experience in Squamish.

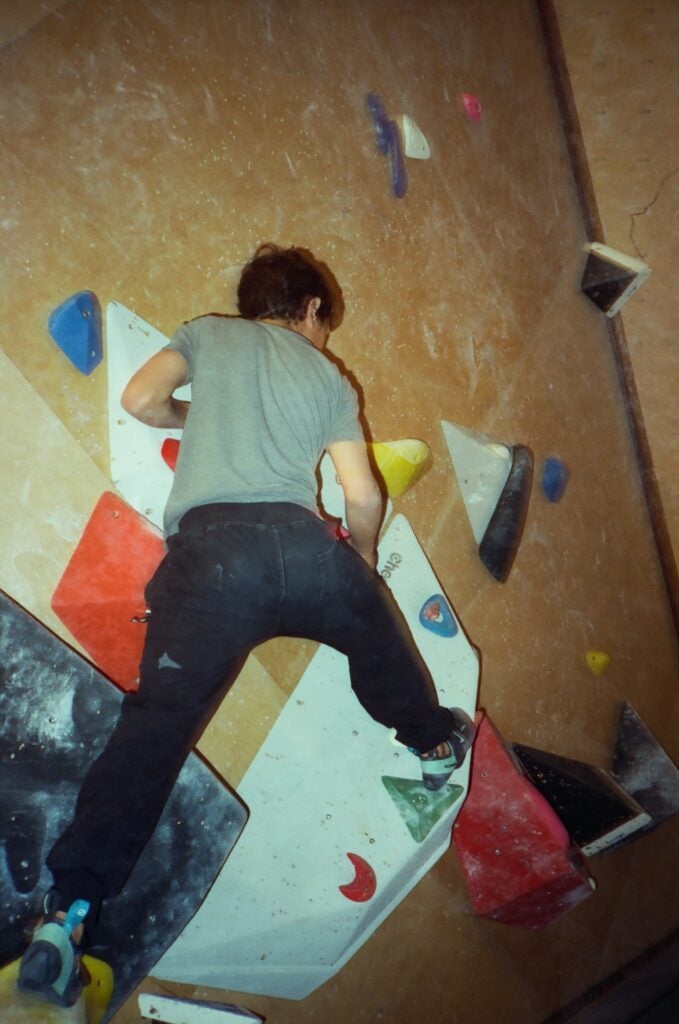

Chua: I started to climb in the later part of 2017. It wasn’t for a story. I was just like, “Man, if I’m going to be here, I’m going to be super miserable if I don’t learn how to do any of the Squamish things.” Because if you don’t do any of the outdoor stuff, the nightlife is nothing, the culture is nothing, really. You’re going to go to the same three bars over and over again and just languish.

I went to the gym, I made some friends, I started to boulder outdoors, and people showed me how to lead sport outdoors. Over time, I would learn how to trad climb and do multi-pitches. Eventually, I became addicted to the sport, and it became my favorite thing to do. And still is.

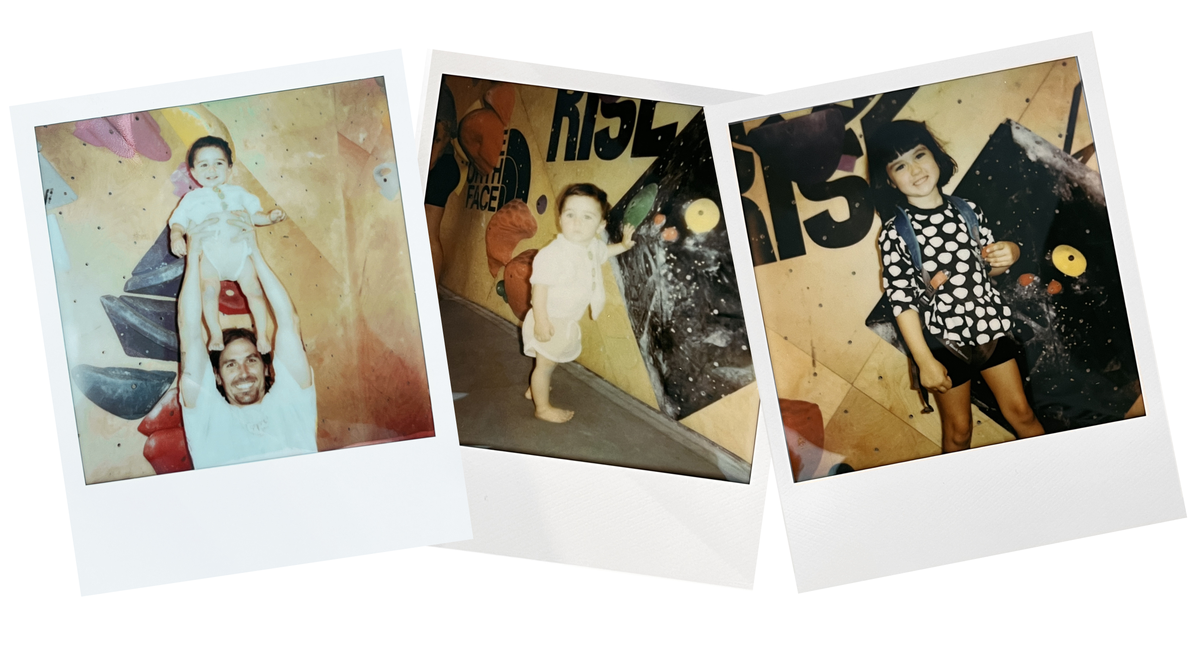

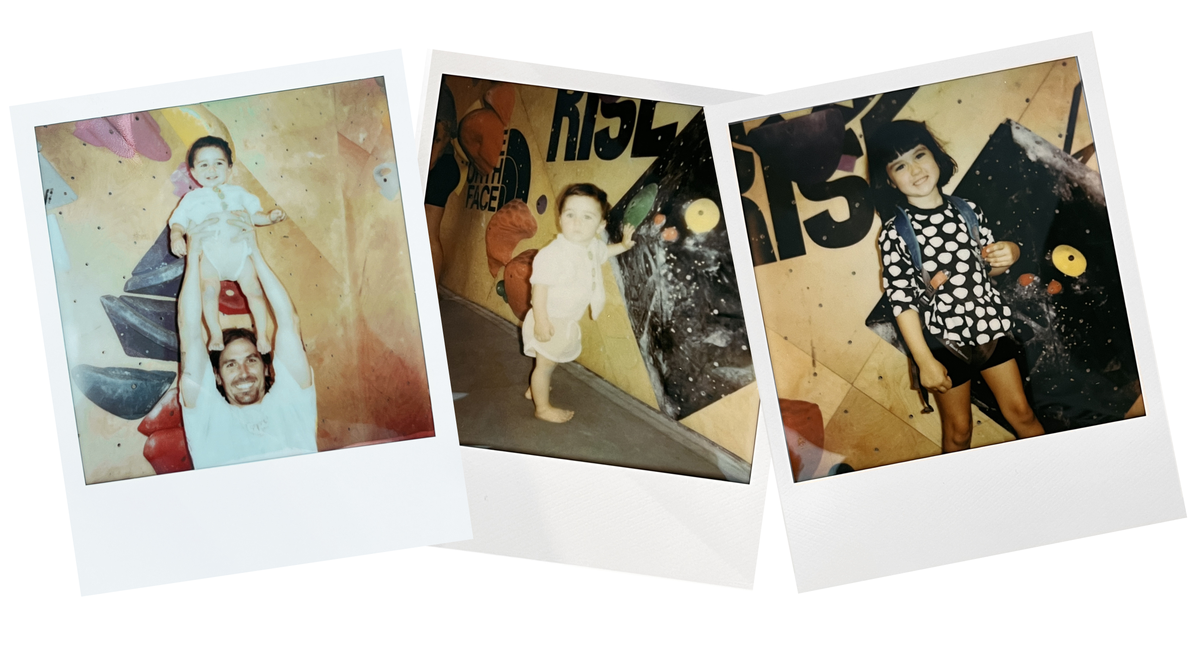

By 2020, I’d already been climbing for a few years. I had a pretty good working knowledge of the sport, and I’d made friends in the climbing community. Those friends knew people, who knew people. That was what allowed me to connect with one of Jesse’s old climbing partners, and with his romantic partner. And that was what allowed me to get a bit of an edge over other reporters, who didn’t necessarily climb or know much about climbing.

Climbing: As you learned more about each of Jesse’s neo-Nazi, spammer, and online climbing troll personas, what shape was this person taking to you, in terms of his patterns of behavior?

Chua: He was an archetype for a lot of the things that we see right now. He was an archetypical online influencer who managed to gain this pretty sizable following before social media became a thing, just using basic, `90s-style websites. He was an archetypical crypto bro, because he was investing heavily in it before any of us even knew what Bitcoin was. He was an archetypical spam advertising guy who was able to prey upon people’s insecurities long before any of us got high-speed internet. He knew there was a lot of influence in rage. Rage baiting. Controversy.

He’s a patient zero for a lot of these strange and unsettling trends that we’re seeing today. It’s just so interesting that one guy could be so involved in all those things in one go. The team I was working with, we call him the Catch Me If You Can of the dark web. You have this figure who is always on the run from authorities, putting on different personas, milking them for all they’re worth, conning a bunch of people, and throwing it away and doing it all over again.

Climbing: Why do you think Jesse did what he did, in all of his past lives?

Chua: This might just be me projecting or speculating, but the impression that I got is—especially from the stuff that his mother had to say at the time—he was bullied at a certain point in school. I think that even though his dad brushed it off, it left a very big mark on him.

In order to adapt to that, he felt the need to develop this skill of being able to influence people and get certain types of people to bend to his will or to follow him. In order to get himself out of this place of vulnerability, he started to practice that more and more. And in order to keep that influence going, he would adopt whatever persona would allow him to do that best. At first, it would be as this Neo-Nazi leader, and then, it would be as this Spam King. That’s the common thread that you see. Talking to his dad when I was doing the initial few stories, his dad was like, “He just wanted attention and influence.” I wouldn’t be surprised if that were actually true.

Climbing: Some people may see this guy’s high-level descriptors—Neo-Nazi, scammer, online shitposter—whatever you want to call him—and ask: “Why give this literal dirtbag any more attention?” Why did it feel important to you to keep digging and to tell this person’s full story?

Chua: That’s definitely a question I had in my mind for quite some time. It’s a very valid point—why are we continuing to give this person the spotlight? I can understand why people would have concerns about that, because we don’t want to glorify this kind of lifestyle. But at the same time—especially with a case like this, where it so deeply exemplifies all these things happening in our present-day world—I think it’s really important to understand where this all comes from and where it can go. The personal can sometimes have elements of the universal. If we try to understand the course of a person’s life, maybe we can better understand how we can live with all these things that are happening now.

Climbing: Did the process of recapturing this story in a podcast surface new insight for you about Jesse as a climber or as a person?

Chua: It brought conflicting perspectives. His old climbing partner had a very positive view of his experiences with the guy. In his experience, Jesse was maybe a bit of a troll, but generally a good dude and a good person to climb with. Then you hear from someone like Jennifer Archie, the AOL lawyer who was filing suit against him as a spammer, and you see the effect that this guy had, scamming so many people out of so much money.

It made me think of all the times you’re on the sharp end with someone, and you experience these very intimate things that only climbing can really bring out. You can see what a person is like when they’re runout half a pitch up. Their family and friends who don’t climb will never see that kind of fear or focus. But at the same time, you might not know very basic things about them. What’s their real name? It just made me think about: How much can you really know about a person?

Climbing: What’s your best guess as to what happened to Jesse?

Chua: What eventually happened is that his personality and his hubris made him too noisy—it made him a target. That character flaw propelled him to great heights, but eventually got the better of him.

I think if he had just shut up and lived a normal, quiet life, he would have been able to happily climb anonymously well into his old age, and probably just die in a hospital like a normal person. But instead, that one part of his personality just kept on showing up over and over again. And eventually, whether it was through him pissing people off or flashing obscene amounts of cash around town, someone realized that he would be a great target. Whether it was for money, because they were angry, or whatever, we don’t know, but I think that’s what did him in.

Climbing: You describe this as “the biggest story of your life” as a journalist in Dirtbag Climber. What are the life lessons you’re walking away with, from the story of Jesse James?

Chua: The one that probably stays with me is that duality of knowing and not knowing someone. I think the reason why people can get so attached to their climbing partners is because you see a part of them that is basically unknowable in day-to-day life. A climbing partner can give you amazing experiences in such an immediate, visceral way, like when a buddy of mine belayed me for the first time on a trad lead. I’m going to remember that for the rest of my life.

At the same time, maybe you just need someone to hold your rope, and you don’t care who. It made me think of how much you can know about someone you climb with, without really knowing them in the rest of their life. Maybe that’s a good thing, maybe that’s a bad thing. I don’t know. It’s funny in that way.

The post A Squamish Climber Was Murdered in 2017. Now, Another Local Climber Searches for Answers. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Boulder, eat, wander, repeat: The French Olympian shares her routine for living between the Magic Forest and the capital city.

The post Oriane Bertone Shares How to Climb and Eat Your Way Through Paris and Fontainebleau appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

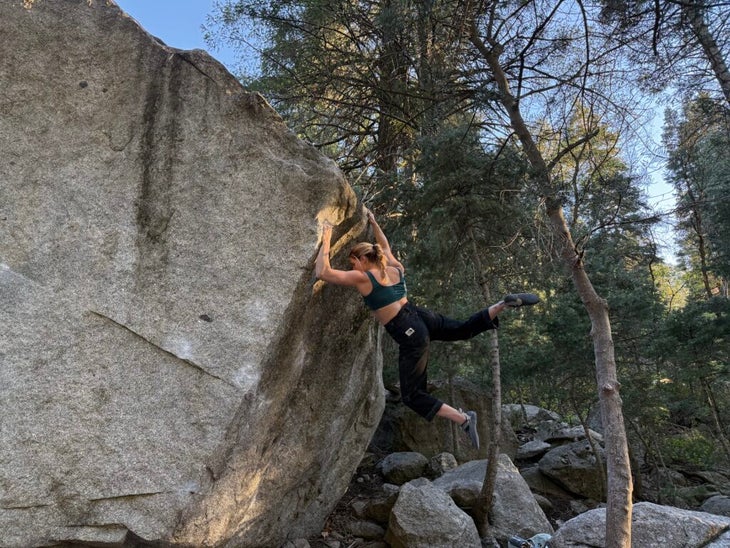

From week to week and morning to night, French pro climber Oriane Bertone keeps a foot in two worlds. The first is Fontainebleau, where thousands of acres of protected forest cradle thousands of internationally iconic sandstone boulders—and where Bertone now lives. The second is Paris, just an hour and a half north of Font by car and less than an hour by train.

When we spoke, Bertone shared her schedule for a recent week of going back and forth between the City of Light and the Magic Forest. It’s heavy on bouldering: Bertone holds the 2025 IFSC Boulder World Cup title and hopes to compete solely in bouldering at the 2028 Olympic Games, now that the disciplines will be split up. “I’m a boulderer, and I always knew it,” Bertone says.

Bertone spent Monday in Fontainebleau, working out and climbing hard boulders at Karma, a local gym staple and one of the training centers for the French national climbing team. On Wednesday, she went up to Paris and climbed at one of the 11 Arkose bouldering gyms scattered about the city (Arkose is a sponsor of Bertone’s). She can’t exactly remember which one, but it was probably Arkose Issy-les-Moulineaux, where she likes to train slabs and dial in her breathing. Thursday was a rest day in Fontainebleau, followed by another two days of climbing in Paris. “It’s always kind of like this,” Bertone says of her weekly routine.

It’s safe to say that the 20-year-old climber has insight on making the most of the indoor and outdoor bouldering in Paris and Fontainebleau. Bertone sat down with Climbing to share her tips, along with her favorite spots for rest day recreation, food, and culture in each area.

Where to climb, eat, and revel in the arts in Paris

Bertone started climbing indoors and outdoors as a kid in her hometown of Réunion Island, a French territory east of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean—more than 5,000 miles away from Paris. Her father didn’t have a climbing background himself, but he was fascinated by movement and fastidious in giving Bertone and her sister chances to climb the island’s abrasive, volcanic rock. “This is probably why I have thick skin now,” Bertone says, laughing.

She also credits her father with imparting to her the notion that “if you start something, you have to finish it.” When she moved across an ocean to Paris to train with the French national team in 2021—leaving her tight-knit family behind at only 16 years old—she leaned into that mindset. “I knew what I wanted,” Bertone says. “Everything fell into place.”

During Bertone’s first two years in mainland France, she lived in Massy, a southern suburb of Paris. As she settled in, Paris became one of her favorite cities in the world. “People can say whatever they want; I like Parisians,” Bertone says. “It’s always cool to walk around, see the little shops, drink good coffee. You’re able to get on the internet and go, ‘I want to eat Korean food,’ and walk two minutes and there is a Korean restaurant. There is everything in Paris.”

So how would Bertone enjoy the city as a climber? Let’s start with the indoor climbing in Paris. There are dozens of gyms in the city, but Bertone recommends Arkose bouldering gyms. She acknowledges her bias, but says she initially partnered with them because they’re her favorite. She goes to Arkose Nation and Arkose Issy-les-Moulineaux for slab climbing and finds the best hard boulders at Arkose Massy. “Everybody goes [to Massy], even the strongest people,” Bertone says.

Between training sessions in Paris, Bertone likes to refuel with Korean food at Sweettea’s, which serves classic dishes like bibimbap, barbecued beef, dumplings, and kimchi pancakes. The Asian fusion restaurant also serves honey mustard fried chicken and a mozzarella-infused take on tteokbokki, a Korean rice cake snack. Bertone’s rest day recommendations also include taking a walk through the Jardin du Luxembourg (just don’t go on weekends) and going to the opera at the world-renowned Palais Garnier. Heavy hitters like the Louvre are also worth seeing.

“I can cry in front of a painting or because somebody’s singing in a high-pitched note,” Bertone says. “I’m deeply touched by art, so I like going to operas and museums. And in Paris, we have so many.”

Bertone remembers the influx of visitors coursing through Paris when she competed in climbing at the 2024 Olympic Games. Looking back, she says she felt more energized than overwhelmed by being in that position. It helped that the French people kept their Olympic patriotism lowkey, Bertone says. “The people were proud of us and happy it was in France, but I think they were more upset about the expensive prices of the tickets,” she says. “I didn’t feel pressured at all.”

Though Bertone liked life in Paris and the Massy suburbs, when she turned 18, she thought about making a change. She had first traveled to Fontainebleau with her family when she was eight years old; ever since, she had dreamed of being closer to the sandy forest. They kept coming back throughout her youth, during which she managed sends of Satan I Helvete Low Start (suggested to be 8C/V15 at the time) and Super Tanker (8B+/V14). “I fell in love with climbing because of this, for sure,” Bertone says of her trips. “It was a dream place. Every time I left, I was sad and I was crying. I wanted to stay.”

Two years ago, Bertone finally moved to Fontainebleau. “This is where I’m happiest,” she says. When asked how she’d go about traveling to La Forêt for the first time, Bertone positively lights up.

Boulders, pastries, and leaving no trace in Fontainebleau

La Forêt, the Magic Forest, ‘Bleau, Font — Fontainebleau is known by many names. Bertone found a house there in 2023, where she now lives with her boyfriend and dog. But what exactly drew her there? “Just imagine,” Bertone says. “You’re like, ‘I want to climb outside.’ You take your car, your crash pads, you drive, you park, you walk five minutes, you climb. You put your crash pad in your car, you go home. Then, you’re like, ‘I want to go again tomorrow.’ The same thing. You walk in the sand and you climb whenever you want, wherever you want, every day. You don’t have to walk 10 miles just to get to the point where you want to go. It’s easy, practical, and beautiful. It smells like dirt and roots and rock. For me, Font is just the place to be.”

Bertone’s guide to Fontainebleau starts with getting there from Paris. She prefers taking the R train from Gare de Lyon, one of the capital city’s major train stations. Get on the R line, color-coded pink, in the direction of Montargis. You’ll make stops at Melun and Bois-le-Roi before arriving at Fontainebleau-Avon. If you’re not in a rush to get to Fontainebleau and it’s warm out, get off one stop early at Bois-le-Roi and go swimming at the base de loisirs, or outdoor activity center. Spring and autumn are popular climbing seasons in Fontainebleau, though Bertone’s season often depends on the demanding IFSC competition schedule.

Once you arrive in Fontainebleau, Bertone recommends renting bikes. There are plenty of ride sharing services like Ubers around as well. If you want to visit each of the charming, little nearby towns like Milly-la-Forêt or Arbonne-la-Forêt, you may also want to rent a car. Those towns are also chock full of comfortable gîtes (countryside home rentals) and Airbnbs.

You can find just about any kind of boulder you want in Fontainebleau—crimpy, slopey, physical—laid out neatly on Bleau.info. The selection is so dazzling, it’s almost indescribable (but Chris Schulte does a good job of it here). For first-timers, go-to sectors include Bas Cuvier, Isatis, Cuisinière, and Trois Pignon’s sandy Cul de Chien. “They have very easy access, and the boulders there are awesome,” Bertone says.

But tourists, be warned: the code of environmentally-responsible climbing ethics runs deep in Fontainebleau. Bertone breaks down some of the rules, which are in line with the Access Fund’s Climber’s Pact: Don’t climb too early or late and shine lights on the rock in the dark, disrupting the wildlife. Don’t blast music for the same reason. Leave no trace with trash—or poop. “Don’t wipe your ass with wipes and throw them in the forest,” Bertone says. Clean tick marks. And do not climb the sandstone after it rains or in high humidity. “You have to think: Would you like to be there after yourself?” she asks. “There are so many people coming. You have to be attentive to the wildlife and the forest. Don’t stop it from growing because you’ve been careless.”

If it rains, head over to Karma instead, where you can often spot Bertone and her teammates training. The gym also rents out crash pads for when you do get to climb outside. Another rainy day or rest day activity Bertone recommends is a visit to the Château de Fontainebleau in the region’s city center. And while you’re in town, pay a visit to Bertone’s three favorite restaurants: Démé for pizza and pasta (it’s always packed, so make a reservation); MA.SU for Japanese food (try the foie gras sushi); and L’A pâtisserie (get a big box and try one of each pastry).

Commuting between Fontainebleau and Paris and toggling between indoor and outdoor bouldering offers Bertone distinct challenges and opportunities—to which climbers young and old and new and experienced can relate. When Bertone trains in Paris, working to get better each day makes her feel alive. When she climbs in Fontainebleau, she’s struck by the passage of time. “I go back to a boulder I did 10 years ago and I’m like, ‘I can’t do it anymore,’” Bertone says. “Sometimes, it’s surprising. It feels like every year is full of lessons and full of new things.”

The post Oriane Bertone Shares How to Climb and Eat Your Way Through Paris and Fontainebleau appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Gym owners, gym members, coaches, and parents weigh in on paths to peacefully coexisting.

The post Don’t Fall on the Groms: How Kids and Adults Can Better Share Climbing Gyms appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

In a word, how do climbers, parents, gym owners, and youth coaches from around the U.S. describe the dialogue on dealing with kids in climbing gyms?

“Torturous,” says Grayston Leonard, owner of Long Beach Rising, a climbing gym in California.

“Contentious,” says Lily Kral, owner of Boardworks, a board climbing facility in Bend, Oregon.

And to Allyson Gunsallus, creator of the film series Hand Holds: Climbing after Parenthood, it’s “enlightening.”

Whatever the word for the discussion on this increasingly timely topic, issues related to sharing space with children in gyms revolve around both etiquette and safety. I interviewed parents and child-free members of the climbing community for this story, and together, we went over the common grievances we’ve heard—or had. I also did some Reddit rant deep diving.

Complaints mostly center upon kids with non-climber parents. Adult climbing gym-goers cite kids hovering over a single problem in packs or jumping on a just-brushed climb. They witness children of all ages sprinting, somersaulting, belly flopping, or rolling like a log on the mats. The cherry on top: when parents are too busy chatting or on their phones to notice.

These grievances grow into genuine concern for risk of bodily harm when kids end up in bouldering fall zones. In one such situation, a climber shared a video of himself falling on a girl in February. The reel now has more than 12 million views and a lot of inflamed opinions. Pro climber Alex Johnson chimed in with a comment last month: “I’ve seen this dozens of times in the gym and have almost been a victim of it myself, and so have friends. Kids running or climbing underneath people is so dangerous. Zero situational awareness. They need to be supervised, just like they would in a workout gym, it’s not a playground. 100% not on you.”

As many of the comments on that video and others like it reveal, a blame game emerges and ensnares parents, adult climbers, gym owners, gym staff, coaches, and the kids themselves. How can these parties free themselves of fraught social media discord and real-life tension, and find ways to better share the space? As a mom of a toddler who I hope will be a more frequent gym-goer soon, I wanted to see what the sport’s different stakeholders had to say about the issue. We also weighed solutions, ranging from communal correction to age-specific spaces.

“Set up for conflict”: How frictions arise with families in climbing gyms

Mike Rougeux has coached youth climbing in Bend, Oregon for more than 20 years. He’s brought his son, who’s now seven, with him to local climbing gyms since he was three. So in the past, it hurt to hear his friends in the climbing community complain about kids at the gym.

But as climbing gyms grow and commercialize, Rougeux understands how frictions arise. More casual climbers and individuals who are just climbing-curious are heading to the gym. “We have facilities where it’s a rainy day and parents are like, ‘What should we do today? Oh, let’s try rock climbing,’” Rougeux says. “So you have parents and kids entering a space where you just bring your kid there, and the parents don’t understand the social norms of how to operate within that space. Of course, neither do the kids. We’re set up for conflict to happen.”

All the climbers, coaches, and gym owners I spoke with agree that parents—however new they are to indoor climbing—should be closely monitoring their children. Not just nearby, but staying right on their heels. They also agree that gyms need to supply families with the information they need to understand the urgency in doing so. “For first-time folks going to the gym with a kid, the parental obligation is extremely high,” says Joey Churchman, a climber and father of three children ages one to five. “They need to be responsible for their child. It’s constant attention.”

But these folks also agree that the conversation shouldn’t stop there. Yes, parents need to watch their kids. But what else can be done before, during, and after mistakes are made? To start, Rougeux and the others say that a little grace for families goes a long way. “It’s intimidating going in and trying something for the first time, and you’re the adult trying to lead your kid,” he says. “You don’t know what to do. So now you’re relying on the 16-year-old behind the desk to tell you. The gyms, staff, and community can probably do a better job of helping.”

“It takes a village”: Sourcing ideas from other sports communities

Grayston Leonard, 35, didn’t start climbing until he was in his 20s. He grew up skating, and when I spoke with him, he was in his car on the way to go surfing. To Leonard, a father of three and a gym owner since 2019, indoor climbing could use more of the clear communication he received as a kid getting into sports. “In surf and skate, you’re constantly sharing these places,” he says. Out on the water, Leonard saw adults telling off adolescents all the time. “No one holds back,” he says. “No one’s shy about this. You’re teaching them the rules of how this works, how you share this space, and how you do it safely and respectfully.”

Adults and kids then return to those spots, recognize each other, and eventually learn from each other. “People will see you pushing your comfort zone and cheer you on and root for you,” Leonard says. “That then creates this feeling of belonging.”

At the gym, however, Leonard doesn’t apply quite as gruff of an approach to correcting kids. But he is direct with them. “People should feel more freedom to speak up to kids,” he says. “Kids don’t care what their parents say, but when they hear it from someone else, it freaks them out.”

When Leonard spots a kid running underneath him while he’s climbing, he doesn’t let it slide. He’ll go up to the kid and calmly explain the risk: “Hey, you ran underneath me. It’s really dangerous. I don’t want to fall on you.” It usually invokes momentary stranger danger and a dash to the parents. Leonard will give them a little wave. “That’s really all it needs to be,” he says. “Instead, there seems to be this really passive aggressive behavior of: ‘Why don’t these kids know any better?’ There seems to be no forgiveness, no grace, no leniency toward this. I get it. But let’s not act like we weren’t all kids ourselves, learning all of this stuff at some point. That’s where this saying takes on a whole new meaning: ‘It takes a village.’”

Allyson Gunsallus emphasizes that there needs to be a level of tact to these interventions. As a mom to a three-year-old (with another on the way), Gunsallus has climbed for nearly two decades, primarily in Yosemite. In an effort to learn from pro climbers who have navigated the challenges of becoming a parent, she created the documentary series Hand Holds. She tries to empathize with families who are new to the oft-unspoken norms of climbing gyms. “It’s important for us to consider how we would receive the correction we give, to help us be welcoming and helpful, rather than abrasive and confrontational,” she observes.

But giving the groms a chance to learn doesn’t mean letting inattentive parents off easy, Leonard cautions. At his gym, Long Beach Rising, parents to kids under 12 must closely trail them at all times. No bench sitting, no “la-dee-da-ing.” The staff has only had to pull people out of the space, refund them, and send them away a few times, but it’s something Leonard is willing to do if rules are repeatedly broken. “I would rather tell someone they can’t come back for a period of time or that their session is done for these reasons, than be afraid of the negative Yelp review,” he says. “You have to be willing to have those uncomfortable confrontations.”

Whether in the form of uncomfortable parent call-outs or direct communication with kids, this communal approach relies on active engagement. But not all adult climbers may want to step in. Not everyone wants to discipline someone else’s kid—and not every parent is receptive to it.

Boardworks owner Lily Kral remembers encountering that resistance. “I’ve seen it many times and heard about it many times, when there is a gentle correction and the parent doesn’t react appropriately,” Kral says. “In order to really facilitate those rules and ensure they’re enforced, you need a lot of front desk staff that are trained and have the confidence to correct parents.”

In her early years of working at a climbing gym, Kral didn’t necessarily feel equipped to do that. “I kind of cared,” Kral says of her time working the front desk as a 16-year-old. “These are really large spaces and front desk staff are busy checking folks in. They’re watching to make sure rules are enforced, but they can’t be everywhere.”

Another route: Designated climbing spaces for adults and kids

In 2021, Kral created a gym with no front desk staff and a few other unique features. Boardworks is a 24/7 climbing facility in Oregon dedicated solely to adjustable boards: Kilter, Decoy, Grasshopper, Tension Board 2, 2016 Moonboard, and a spray wall. But she also decided to make the space dedicated to adults: 18 and up for members, 16 and up for guests.

Kral chose to limit Boardworks to adults to suit the small gym’s 24-hour, staffless model—and to avoid “increasingly complicated” insurance policies related to minors. But the concept of offering climbers an adult-centered space was also enticing. She hadn’t seen many adult-only indoor climbing options. “People appreciate being able to climb without worrying about all of the problems we know can arise with climbing around kids,” she says. “Having a dedicated space for adults to work out, do their thing, and not worry about safety hazards or other complications.”

But adult-only gyms aren’t necessarily a knock on kids, Kral believes. “I have a lot of parents at the gym,” she says. “I don’t think that having a dedicated space for adults means that the intention behind it is to paint children in climbing gyms in a negative light. It’s purely to provide a more safe and dedicated space for what some adult climbers want to pursue.”

A group of dads that Kral has dubbed the “Dad Squad” go to her gym after putting their kids to bed. When they go indoor climbing with their children, they visit other gyms in Bend. They didn’t choose Boardworks to get away from kids, but rather to take advantage of its board-climbing focus and later operating hours. “The value of an adult-only climbing gym isn’t that there aren’t kids, it’s that you’re surrounded by adults,” says Daniel Ling, a member of the Dad Squad. He finds that the group’s night sessions at Boardworks provide a time and space in which trading stories about their kids throwing vegetables across the room is as enriching as swapping beta.

Adults aren’t the only demographic that could use dedicated space. In 2023, Rougeux opened the nation’s second youth-only climbing facility as the new HQ for Bend Endurance Academy. Before the facility opened, Rougeux coached climbers in the shared space of commercial gyms.

Back then, he tried to minimize his team’s impact by giving pep talks about representing the organization well in a public setting. He used to draft plans for practice that dispersed the kids rather than concentrating them on one wall. “But it was weird, because then, I had constraints placed on the coaching,” Rougeux says. “A lot of times, the way I was designing practice was strictly based off of managing the group and the impact the group would have within the gym.”

Now, the kids get their own version of a gymnastics center. Bend Endurance Academy hosts camps, the occasional birthday party, and one of the top-ranked competition climbing teams in the U.S. “No members, no day passes. It’s just youth programs, just like gymnastics,” Rougeux explains. “When they see those pads and want to do flips, we’re like, ‘Sick, let’s do flips.’”

The youth-centric space has brought something new out of Rougeux as a coach and the kids as climbers. “My coaching has totally changed,” he says. “It’s so much better across the board, from my highest-level athletes to our kindergarteners. It’s a better experience because we can design the space specific to the needs of who’s in front of us.” The kids at his gym are free to listen to high-tempo music, huddle up with more space, and hone specific movements. There’s been an energy shift, Rougeux says: “It elevates their experience in ways I didn’t really foresee.”

Rougeux recognizes that Bend Endurance Academy’s facility model isn’t feasible for youth recreational and competition climbing programs everywhere. But other gyms are already starting to adopt youth- or adult-designated spaces and time windows. The Circuit in Bend, for instance, has a contained kids’ climbing area with a slide in the middle. The gym has also introduced youth reservations for busy days like weekends and school holidays. Ruckus, a gym in Greensboro, North Carolina, offers a kids’ zone with challenging climbs for short wingspans.

Gunsallus encourages further exploration of these concepts and other ways to support families. She hopes to see the return of childcare, with which some climbing gyms used to experiment. An open, designated family area away from the mats would also help, or even allotting an unused yoga room. “A designated family space outside of the climbing fall zone could create a community among gym families that may even be strangers to each other,” Gunsallus says.

Though Rougeux and Ling both enjoy spending time in dedicated spaces, they also admit they miss the commingling of kids and adults. To them, and to Kral, it’s worth pursuing both options instead of pitting them against one another. They echo Leonard’s points about acting as a village to get along in shared spaces. Separate climbing facilities can also be harmonious within one community, as seen in Bend: Boardworks and Bend Endurance Academy have partnered up before, allowing the former’s adult climbing team limited access to the youth training center.

“As a community, the climbing world could be more inclusive to youth participants,” Rougeux says, “but I also directly see a need and a place for specific facilities or times.”

Final thoughts: How can gym communities approach solutions?

No single fix-all solution for safe, peaceful coexistence between kids and adults exists at climbing gyms. But the ideas that these gym owners, coaches, and parents shared with me may be able to alleviate some of the building tensions around kids in those spaces. From holding all parents of kid gym-goers to higher standards and communal communication strategies, to dedicated adult or kid spaces, many of these solutions can work in tandem to address the issue.

On my part, as a gym user, I’ll work on picturing different perspectives: of non-climber parents who don’t know what they don’t know, of the gym staff who feel uneasy squaring off with an inattentive parent, of the adult climbers who are just trying not break a little set of limbs, and of the kids who just want to play. “You can’t fault the children,” Kral says. “They’re kids. At the end of the day, it’s never the kids. It’s easy to forget that when they’re the ones running around.”

The post Don’t Fall on the Groms: How Kids and Adults Can Better Share Climbing Gyms appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Paraclimbing will have eight medal events at the 2028 Games in Los Angeles.

The post Last Week’s Paralympic Climbing Announcement Left Some Athletes Stunned. Here’s Why. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Last week, the International Paralympic Committee (IPC) announced that paraclimbing will debut at the Paralympics in 2028 with eight medal events:

- Visual impairment: women’s B2 and men’s B1 (on a scale of 1 to 3, the level of impairment increases with lower numbers; e.g., B1 climbers are totally blind; all athletes compete in the “lead” discipline, for which they climb on toprope)

- Upper limb deficiency: women’s and men’s AU2 (reduced function/absence of forearm)

- Lower limb deficiency: women’s and men’s AL2 (limited use/loss of one lower limb)

- Range and power (RP): women’s and men’s RP1 (RP spans impairments like hypertonia, ataxia, athetosis, and impaired passive range of movement, linked to conditions like muscular dystrophy, cerebral palsy, spina bifida, and spinal cord injury)

The announcement follows the IPC’s approval last June of paraclimbing as a new addition to the 2028 Paralympic Games. The IPC also confirmed that paraclimbing will take place at the Convention Center Lot in Long Beach, Los Angeles.

Watch the athletes interviewed in this story climb and share their reactions to the Paralympic climbing news

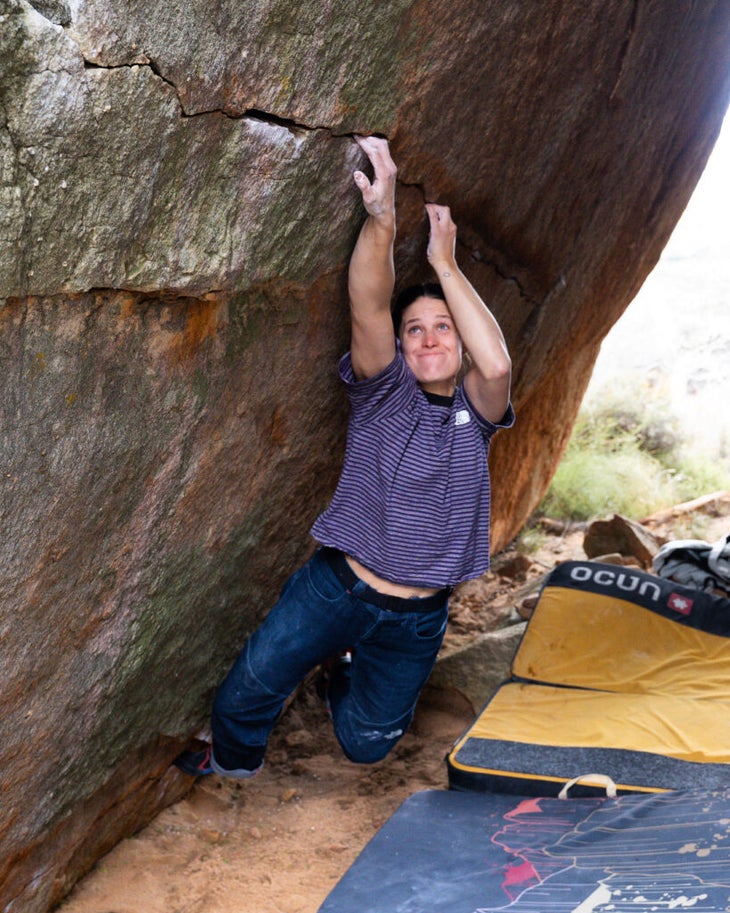

In the year of waiting to learn which of the sport’s 10 total events (per gender) would run in climbing’s Paralympic debut, athletes braced themselves for a smaller selection. “Just like able-bodied climbing, odds are we’re not going to get 10 medals,” professional paraclimber Maureen Beck remembers thinking in the leadup to the news.

Beck retired from international competition in 2023 with one “giant caveat.” She planned to return to try to qualify for LA28 if her event—women’s AU2—made it through (it did). “Anywhere between three and five medals is what my gut and conversations said we would get, and then we ended up with four.”

Which Paralympic climbing events the 2028 Games exclude

The 2028 selection excludes a dozen men and women’s International Federation of Sport Climbing (IFSC)-recognized paraclimbing events. The full set for both genders totals 20 events.

For the visually impaired category, the IPC omitted women’s B1, men’s B2, and B3 for both genders. For athletes with upper and lower limb deficiency, the following categories won’t compete in 2028 either: women’s and men’s AU3 (hand impairment, with one hand or multiple digits in both hands missing or with reduced function); and the women’s and men’s seated category, AL1 (athletes with no use of their lower legs). Within range and power, men’s and women’s RP2 and RP3 will also miss out.

The paraclimbing community anticipated a few of these calls, but some felt like head scratchers to climbers. Athletes have been working through different reactions, ranging from elation to heartbreak to disbelief.

“I’m not looking forward to going to Innsbruck this time, for the first time, because I know it’s going to be such a heavy environment,” says Ben Mayforth, an RP2 climber. “But I think our community really needs to do a good job of supporting the categories that are going, and then showing the IPC what their category can do in anticipation for Brisbane.”

Why paraclimbing visual impairment events differ between women and men

The IPC didn’t share rationale or details about the decision-making process with its June 3 announcement. Beck suspects that the decision probably came down to a few major questions tied to historical numbers: “Are the bigger picture disabilities all represented? That’s amputee, that’s RP, that’s visually impaired. Because each one has multiple classes, which ones have the biggest pool of athletes to pull from, and which ones have the best representation for men and women?”

Fabrizio Rossini, IFSC media and communications director, confirmed that the IPC primarily based its evaluation on participation numbers from IFSC events. “This has been a main limitation for some sports classes, which unfortunately do not have sufficient numbers of athletes and countries participating in competitions,” Rossini says.

One decision in particular—though rooted in athlete numbers—has perplexed some paraclimbers: including only women’s B2 and men’s B1 in the visual impairment category. Rossini explains: “The number of absolute athletes who participated in IFSC World Cup in the cycle 2021-2024 was not sufficient to guarantee an adequate starting list ahead of the qualification system, according to IPC parameters. Furthermore, the IPC is not in favour of combining the classes.”

Some visually impaired climbers have openly criticized the way the IPC has structured its medal event program for the 2028 Games. Emeline Lakrout, who competes in B1, questions the choice to pluck out the single B classes. For months, Lakrout says she and many of her peers expected the IPC to merge all three blind climbing classes into one and have the competitors climb blindfolded. “Getting the news that instead, there was this bizarre mishmash of different categories picked for different genders, and then an exclusion of the most blind—that was honestly very, very surprising,” Lakrout says.

Lakrout sat with the announcement on her phone for about a minute before deciding to fight it, fueled by what she describes as “routine inequity” against women’s B1. Just one example? Merging blind classes at past competitions, in which blindfolded women’s B1 climbers competed with other B-class climbers sans blindfolds. “We’ve already seen in the past, where they’ve dumped everyone in one category, and the question is, why do they not put everyone under blindfold?” Lakrout says. “Well, it would disadvantage those who are not used to it. So instead, the natural status quo was to disadvantage the B1s—those with the most severe disabilities.”

As a disability advocate, Lakrout is collecting athlete signatures for a petition to challenge the decision. “I personally get extremely fired up when I see a situation where the most disabled are being marginalized and shut out,” she says. “Literally, the IPC is saying I am too blind to climb.”

The paraclimbing community is tight knit, so the athletes who still have the chance to head to Los Angeles in 2028 are balancing excitement with empathy for those who won’t compete. Kyle Long, an AL2 climber whose class will run, wishes he could see AL1 and RP2 climbers on the wall at the Paralympics. The seated category’s omission was another surprising call to climbers. “AL1 climbers—visually, athletically, in every way, they’re the best of our sport,” Long says.

Personal heartbreak, collective joy

After learning that the RP2 category didn’t make it through, Mayforth has tried to keep things in perspective. “The way we’re reacting to it, we need to show ourselves grace and the community grace,” he says. “We all got to be part of this big push. We all put work into it, made sure categories were as competitive as possible, so that we could have these opportunities.”

Emmett Cookson, head coach of the U.S. national paraclimbing team, echoes that sentiment. “We want to keep focusing on what’s in front of us,” he told the team. “No classifications are being taken away from the World Championships. It’s still paraclimbing, through and through.”

From here, Paralympic climbers still await more information about country quotas per event and the qualification process. The IPC also still needs to announce whether the Games will include a separate series of qualifying events, as seen in Olympic climbing in 2024.

However it all unfolds, Beck remains optimistic. “I really hope that all of us—whether you’re going or not—are even more charged to keep growing the sport,” she says. “So the IPC has to say, ‘Holy crap, not only did you guys knock it out of the park at ‘28, you’re our favorite new sport.’ Just how climbing did at Tokyo and Paris. They doubled their medal count, now they have three in ‘28. My guess is by ‘32 we’ll have at least six. By ‘36, we could have the full 10.”

The post Last Week’s Paralympic Climbing Announcement Left Some Athletes Stunned. Here’s Why. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Vest shares her tips for getting started in sewing and what she builds into her own creations.

The post Pro Climber Allison Vest Thinks Climbing Pants Can Do Better. So She Makes Her Own. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

For Canadian professional climber Allison Vest, objects of obsession aren’t exclusively found within the realm of rock. She finds them in quiet moments at home between climbing trips, sitting at her sewing machine and losing track of time making her own clothes. Vest climbs in many of her handmade creations: bolero sets, tailored vintage North Face jeans, a gingham button- up shirt upcycled into shorts, and block-printed pants that she inked for 100 hours.

Vest learned to sew from her grandmother, who taught her how to work a sewing machine when she was a teenager. Now, mornings pass into nights as Vest emerges bleary-eyed from sewing sessions that often last longer than her bouldering sessions. It’s become a bit of an occupational hazard, as well. Vest recently noticed that after she’d hunch over her sewing desk with her head down for hours, a thumb tendon injury she got last year would flare up. Her physical therapist connected her neck position all the way to her worsening tendon injury—it was a full nervous system issue. To alleviate it, Vest had to start setting alarms to take breaks and raise her tools.

But to her, the craft of sewing is worth a little risk. Vest loves the hobby’s flow state, creativity, goal-setting, and embrace of imperfection. Sewing taps into some of the same states of mind that have led to her success in climbing. Vest is the first Canadian woman to boulder V13, she sent Show Your Scars (V14) in 2022, and she’s won multiple national titles in bouldering and lead climbing.

Vest sat down with Climbing to share her tips on getting started in sewing, exploring upcycling, and making climbing pants. Here’s Vest’s story, in her own words.

A common thread between climbing and sewing: projects

I tend to have a little bit of an obsessive personality about projects. I’m always trying to think about the next day or the next session. It’s nice to have something else to obsess over when I sew, so I can stop thinking about climbing. It’s a similar vibe: there’s a process, you have to go through the process, and you have to find enjoyment in the little bits and pieces of the process, because it’s a lot of trial and error.

For example, with a pair of pants I made, I worked on them for seven or eight months. I had to make all these different iterations of them and they weren’t working. I had to try something new, switch this and that, take some measurements out of the waist, add space in the hips. I think that’s similar to climbing, too. When you’re trying to figure out the beta for a boulder, it’s just trial and error. You try one thing, it doesn’t work. You try something else. And then you slowly figure out what the best way is.

All the little bits and pieces eventually add up to sending the boulder, or the end result. In a similar way, it’s important to be focused on the process.

Getting started without getting “sewverwhelmed”

I’m potentially skewed, because I did have some very basic sewing skills from when I was a kid. But to start, it’s always helpful to have a small goal or something to work on. You could try to practice sewing skills and learn super simple stitches or seams, but I usually decide I want to make something, and then I go backwards and figure out how it’s done.

I look up YouTube videos and figure out what the process is to make that thing. If you do that, you end up being a lot more inspired and driven to finish it. Back when I was starting, I relied heavily on YouTube tutorials that would show you exactly how to sew a pattern [a clothing template, with pieces to guide fabric cutting], exactly how to do a hem—exactly how to do every single step. A lot of the high-level pattern makers will make detailed, helpful YouTube videos to sew along to.

There’s a climber in California named Jess Capalbo, for example, who was really helpful for me. She’s helped create a couple of climbing pant patterns. Social media has so many problems in terms of toxicity, but one thing it’s really great for is getting fast, easy information. So I’ve found a couple people on Instagram that’ll give you sewing tips or tricks, and then people like Jess, who release really cool, high-quality patterns that come with full, detailed YouTube tutorials.

Starting out, you have to let go of trying to make everything perfect. I’m a perfectionist, so I’m always trying to make things exactly perfect. But at the end of the day, things that are handmade are handmade. As a tailor or seamstress, you get to a point where it’s high level and everything is exactly perfect, but when you’re first starting out or trying to get better, that is not the case.

Climbing pants: a sewist’s dilemma

I’ve always been inspired by the outfits that people wear more in dance than in climbing. It feels a lot more feminine, but also interesting in the way that movement looks on the wall, which obviously in dance is important. That’s the point: that the movement looks a certain way. Whereas in climbing, you don’t necessarily get points for aesthetics. When you’re climbing, it’s just about getting to the top. But I do think it’s interesting, the way that dancers dress to enhance the way movement looks, but also to make sure they have the full range of motion.

A lot of the trendy climbing pants don’t give you that full range of motion. The heavy-duty, canvas vibe of pant that is super common, I find a little restrictive sometimes. I think climbing has moved into a very interesting fashion niche. It feels a little bit like skate culture right now. I’m not a skateboarder—so skateboarders don’t come at me—but there’s a higher mobility requirement for climbing, just in terms of the positions you put your body in. That is an interesting dilemma in terms of creating clothing.

People always say: you look good, you climb good. People want to look good when they’re climbing, but at the same time, you don’t want to be restricted by your clothes in the pursuit of looking good. The goal with the bolero set was to have something that looks super fashionable and cute, but can also allow a full range of motion. I’ve liked playing with different fabrics.

How I like my bouldering pants

As far as athletic pants go, there are a lot of brands out there that I really like, but things circulate pretty quickly. There are all these North Face pants from a year or so ago that I like, so I’ve liked being able to measure those pants, make my own pattern, and try to recreate them.

I definitely like the baggier, oversized look, but I also want them to fit well on my waist, hips, and butt. I don’t want it to be so baggy that there’s no shape to it. So I guess baggy with some shape is what I’m going for right now. I try to keep the pocket styles simple. Climbing—and bouldering in particular—with things in your pockets is sort of dangerous. When I’m bouldering, I don’t have anything in my pocket, so I usually undercook the pockets. I used to really like a cinched ankle, and I’ve done that a little bit, but now I like an open, loose ankle. They sit a little bit higher above the ankle bone, so you’re not stepping on them.

One of the biggest superpowers of sewing is: No sizing is ever going to be perfect. You can only make so many sizes as a brand. So what’s been nice is having the power to make things that fit my body specifically. People are going to always have different opinions or preferences about the way that apparel fits. I also like buying slightly bigger sizes and then taking things in at the waist. I’m not 100% sure of the science behind why that’s exactly what I like, but that’s been my best go-to—getting things that fit a little big and taking them in at the waist.

The added appeal of upcycling

It’s really cool to see brands moving toward circular, sustainable practices. The North Face is really pushing for that. They have a few circular clothing projects. They also have a renewed and remade site on their website, where they take things from people with holes in them, fix them, and resell them. That’s one of the reasons I got into sewing, just because I think upcycling is really cool. I watched a documentary on HBO about clothing waste, where even when you donate clothing to a thrift store, most of it ends up getting shipped to Africa and into these massive piles of fast fashion clothing dumps.

To find and use fabric from other things rather than buying fabric new, I peruse thrift stores. I really like using stuff with an interesting pattern. I’ve made two bolero sets with old North Face hoodies. I got The North Face part on eBay, because that’s the attention grabber of the outfit—something that has a cool pattern or a cool color. But one sweatshirt is usually not enough to make a full set with pants. I’m always shocked at how much material pants take to make.

Then I’ll go to the thrift store and try to color match with that one piece, using maybe one or two other sweatshirts to make the full outfit. I like intentionally sourcing one thing from somewhere that is eye-catching for one reason or another. All of the extra material I need, I usually get from our local Savers.

A final thought for sewing-curious climbers

It’s just really fun. I hope more people will do it. It’s a super good side gig to climbing.

The post Pro Climber Allison Vest Thinks Climbing Pants Can Do Better. So She Makes Her Own. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>