Originally published on Yoga Journal

“Yoga has really challenged my ability to sit with uncomfortable situations,” explains New Jersey-based rock climber and yoga teacher Malka Abreu. Although that experience has been yoga’s most significant and lasting effect on her climbing and her life, after years of practicing both, she’s found that incorporating yoga for climbers into her routine has a lot of other benefits. Namely, it’s increased her flexibility, steadiness, strength, and calm and has forced her to be exquisitely aware of her body.

Not unlike climbing, when you’re holding a yoga posee that feels unbearable, you have no choice but to focus on your body and breathe through the discomfort, says Abreu. Yoga trains you to concentrate on your breath and let everything else fade away. By doing so, your brain and body communicate on a different level to enhance your intuition.

Yoga and rock climbing also force you out of your comfort zone to strengthen your awareness and your connection to movement, breathing, and mindfulness. They also demand that you put in the work, physically and mentally, each time you show up to practice.

“When you reach the crux of your climb and you feel like you can’t make it through or you just took a huge whip and don’t feel like moving forward, you must challenge yourself to be in that hard and uncomfortable situation and to learn how to breathe through it,” she explains. “Only then will you be able to truly make progress and reach that next hold.”

Yoga For Climbers

Abreu suggests the following yoga for climbers to target tight hips and hamstrings. Either practice them before your climb to stretch or afterward to help you find some release.

Hands and Knees

Why it’s great for climbers: This deceptively simple stretch lengthens and realigns your spine and both stretches and strengthens your wrists, forearms, and shoulders.

How to: Begin on all fours and place your hands beneath your shoulders and your knees beneath your hips. Slowly begin to rotate your hands to angle your fingers outward. Stay here for 10 breaths.

To intensify the stretch in your forearms, turn your fingers toward your knees. If you want to intensify the stretch even more, ease your hips back toward your heels. Stay here for 10 breaths.

Puppy Pose (Uttana Shishosana)

Why it’s great for climbers: This pose stretches your spine, shoulders, upper back, arms, and abdominal muscles.

How to: From hands and knees, rest the tops of your feet on the ground with your toes pointing straight back. Keep your hips stacked over your knees as you slowly walk your hands in front of you and lower your chest toward the ground. Release your forehead to the ground or a sweatshirt or bag. As you inhale, lengthen throughyour spine. As you exhale, let your chest release closer to the ground. Stay here for 10 breaths.

Hero’s Pose (Virasana)

Why it’s great for climbers: This cringe-inducing pose is sometimes known as “toe killer.” It can feel intense but delivers an essential stretch to the arches and entire bottom of your feet. Practice it each time you extricate yourself from your shoes.

How to: From hands and knees, tuck your toes and walk your hands back toward your knees so you’re sitting upright on your heels. If the stretch is just too intense, bring your hands back to the ground in front of you to take some of the weight off your heels. Stay here for 10 breaths.

Low Lunge (Anjaneyasana)

Why it’s great for climbers: Low Lunge is probably the most familiar of any yoga for climbers poses. It stretches your quads, hip flexors, and hamstrings. It also delivers a slight backbend to help stretch across the chest.

How to: From hands and knees, step your right foot forward between your hands, bringing your right knee over your right ankle. Untuck your back toes and bring your hands to your right thigh, or if you feel stable, reach your arms alongside your head. Push your right heel into the ground to steady yourself. As you let your hips sink forward and down keep engaging your abs and lifting your chest to createa. slight backbend without collapsing in your lower back. Stay here for 10 breaths. Come back to Low Lunge and repeat on the other side.

Half Monkey (Ardha Hanumanasana)

Why it’s great for climbers: A common runner’s stretch, this pose preps you for a good high foot by stretching your hip flexors and hamstrings.

How to: From Low Lunge, bring your hands to the ground on either side of your front foot, propping yourself on your fingertips. Take your time as you inhale and as you exhale begin to straighten your front leg by sliding your heel away from you. Keep your hips stacked over your back knee and flex your toes toward your face in Half Splits. Each time you inhale, find length in the spine. Each time you exhale, fold a little more deeply over your front leg. Breathe here for at least 60 seconds. Repeat on the other side.

Downward-Facing Dog Pose with Crunches

Why it’s great for climbers: This foundational yoga pose strengthens your upper and lower body and delivers a back-body stretch from your head to your heels. Incorporating crunches helps strengthen your core and shoulders.

How to: From hands and knees, walk your hands slightly forward so your wrists are where your fingertips just were and are slightly in front of your shoulders. Tuck your toes, straighten your legs, and shift your hips up and back into Down Dog. Inhale and straighten your right leg up and back.

As you exhale, draw your knee toward your nose as you press your fingers into the ground, round your spine, and stack your shoulders over your wrists. Inhale and straighten your right leg up and back again. Exhale bring your knee outside your right elbow. Inhale straighten the left leg back and as you exhale bring the knee outside your left elbow. Switch legs and repeat on the other side. Repeat 3 times.

Scorpion Stretch

Why it’s great for climbers: This untraditional pose stretches your shoulders as well as the muscles across your chest. It also releases the hip flexor muscles. It sounds confusing until you’ve done it once and then it quickly becomes intuitive.

How to: Begin lying on your belly. Extend your arms straight out from your shoulders forming a T with your palms facing down. Turn your head and bring your left cheek to the ground. Bend your right elbow and place that hand beneath your right shoulder. Bend your right knee and roll onto your left side as you step your right foot behind you, resting your toes or the sole of your foot on the ground. Continue to press your right palm or fingertips into the ground, feeling a stretch across your chest and shoulders as well as your right hip. Stay here for 10 breaths. Repeat on the other side.

Pigeon Pose

Why it’s great for climbers: Pigeon Pose looks different in every person who practices it. What remains the same about the stretch is how it challenges your hips and glutes as well as your ability to breathe through discomfort.

How to: From hands and knees, bring your right knee behind your right wrist and angle your right shin in front of your body with your heel somewhere in front of your left hip. Extend your left leg straight behind you and sink your hips toward the ground. Untuck your back toes. Your tendency will be to roll onto your right hip and shift all your weight into that side. You want to counterbalance and distribute your weight equally. If your right glutes aren’t resting on the ground, place something like a sweatshirt beneath that side as support to level your hips. As you inhale, lift your chest and take a slight backbend.

As you exhale, either stay upright or walk your hands forward and lower your forearms or your forehead to the ground in Pigeon Pose. Focus on releasing your shoulders and your right hip or at least breathing through the intensity. Stay here for 20 breaths. Switch sides.

Ankle-to-Knee Pose (Agnistambasana)

Why it’s great for climbers: Not gonna lie—this pose is another intense stretch for your outer hips and glutes. Focus on your breath and, if you start to hold it, focus on lengthening your exhalations.

How to: Begin seated with your legs straight in front of you. Bend your left knee so your shin is parallel to your body. Do the same with your right leg and stack your right ankle on your left knee. Your shins will be stacked. Press your fingertips into the ground beside your hips and flex both of your feet. Reach your hips down as you lift up through your upper back. Stay here and breathe or explore resting your hands on your shins or walking your hands in front of you while and bending forward over your legs as you keep your back straight. Stay here for 20 breaths. Repeat on the other side.

Bound Angle Pose (Baddha Konasana)

Why it’s great for climbers: This stretch for your your inner thighs and lower back can be practiced anytime and anywhere. Rather than drawing your legs toward what’s in front of you, you release them in the opposite direction.

How to: Begin seated with your legs straight in front of you. Then bend your knees and bring the soles of your feet together. Draw your heels a little toward you to form a diamond shape. Let your knees lower to the sides and allow the soles of your feet to peep apart in Bound Angle. As you inhale, sit taller and straighter.

As you exhale, either stay still or begin to fold forward at your hips. Release your neck and shoulders and rest your hands on your feet or at your side. Breathe here for at least 20 breaths. Remember, you’re not trying to force your body to hold the pose. You’re trying to let your body find release into the pose. If you find that your body starts to shift more forward after you’ve been here for a while, let it.

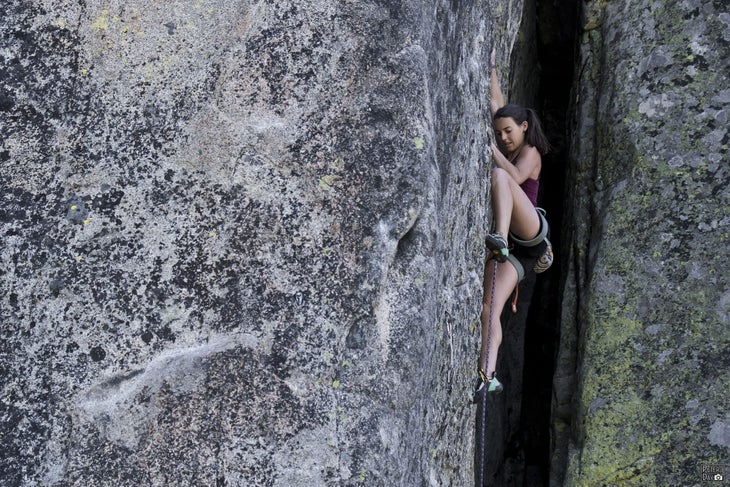

About Our Model

Ben Ko is a longtime student of yoga and all things related to the outdoors. He’s also a Phoenix-based hair stylist.