After a disastrous fall at the Red River Gorge, I investigated the root cause of several seemingly unexpected accidents in our sport.

The post “Nose Hooking” Broke My Partner’s Neck. Here’s How to Avoid This and More Freak Accidents. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

This spring, my partner Harrison was hanging from a jug after pulling through the crux of Fibrulator Direct (5.11d) in the Red River Gorge. He had been projecting this single-pitch crack for weeks, and had shaken out on that hold dozens of times. But this time, when he locked off to move up, the hold snapped and sent him airborne. His highest piece of protection, a 0.4 cam, ripped out of the wall. The carabiner attached to his next cam snapped in half (a result of “nose hooking”—more on that below). His lower pieces, two 0.3s equalized with an extended alpine draw, somehow unclipped from the rope. Harrison fell 40 feet to the ground.

Over the last four decades or so, climbing gear has become increasingly stronger, more reliable, and easier to use. But it’s not infallible. Pete Takeda, the editor of Accidents in North American Climbing, explained that when gear fails to perform its intended purpose, “there’s almost always an underlying error or environmental factor that has come into play.” He doesn’t like the term “gear failure” for this reason.

With Takeda’s help and a careful look at several years of accident reports, I’ve put together a list of common ways in which gear “fails.” Some might consider these instance “freak accidents,” but there are often reasons behind these failures—and ways we can do our best to prevent them.

Unclipping

On rare occasions, a carabiner can unclip from the rope or the bolt hanger to which it is attached. This type of failure leads to unexpectedly long falls.

How it happens

A carabiner can become unclipped from the rope in several ways, but back-clipping is the most common cause. When a climber falls from above a back-clipped draw, the rope can wrap around the gate of the carabiner, unclipping from the draw.

In 2024, a rope unclipped from mussy hooks at the top of a sport climb after a climber removed a carabiner above the hooks. It is unknown whether the rope accidentally unclipped or the climber unclipped them on purpose, but it is possible that the rope loaded the hooks incorrectly as the climber weighted the anchor, causing it to become unclipped.

In much rarer instances, during sideways or very long falls, quickdraws can become unclipped from the bolt hanger if the hanger-side carabiner twists/rotates inside the dogbone, causing the carabiner to be loaded against the hanger at the gate. This type of loading was the cause of two unclipping accidents in 2024.

Prevention

The most obvious way to prevent this kind of accident is by avoiding backclipping. If you’re not confident in this skill, seek qualified instruction.

On bolted routes, quickdraws should be clipped such that the gate of the carabiner is facing away from the direction of travel. On angled bolt hangers (common on expansion or mechanical-style bolts), clipping the draw toward the nut (from the opposite side) reduces the chances of levering the gate open.

Sling breakage

Slings used for permanent anchors can break after years of wear, causing long and sometimes fatal falls.

How it happens

Nylon webbing, common in “tat” anchors in the alpine, is weakened by UV exposure, freeze/thaw cycles, precipitation, and rockfall. When an anchor has many layers of webbing, it can be difficult to assess its quality. Worn-out slings can break under bodyweight or during a fall.

Prevention

Knowing how to assess the quality of nylon webbing—and taking the time to do so—can protect you from a fatal fall. Worn webbing might appear frayed or sun-bleached; be especially vigilant in alpine environments where webbing is exposed to direct sunlight and freezing. If you’re unsure of the webbing’s quality at first glance, spinning it around to look at the “backside” or inspecting the material at the knot might provide more information. If the material in these spots, which are subject to less wear, looks brighter or less weathered, the anchor may not be safe to use.

Be wary of white or gray nylon: webbing in these colors is sold, but it’s less common, and may indicate wear. Precipitation makes descending feel urgent, but wet webbing often appears brighter—be extra careful when inspecting webbing anchors in rainy or snowy conditions.

If you decide that an anchor is unreliable, you still need to find a way down. Fresh webbing and rappel rings are lightweight and inexpensive, and carrying them will allow you to replace worn anchors. A small knife should always be part of your kit on long routes—use it to remove old, worn-out webbing once you sub in your fresh piece. Doing so will help reduce the confusing “rat’s nest” of anchor material on popular climbs.

Protection pulling out

A perfectly placed cam in bullet rock can be as inspiring as a bolt. But gear placements are more often imperfect. Bad placements equals big falls.

How it happens

If a cam is tipped-out (too small for the crack it’s placed in), unevenly cammed (in a flaring crack), or making otherwise poor contact with the rock, it can pull out under relatively low loads. Similarly, if a nut has poor surface area contact or isn’t placed in a constriction, a fall can pull it out. This is especially true of smaller pieces, which present a much smaller margin for error. Remember: the bigger the fall, the more force on your gear, making it more likely to come out if it’s not a perfect placement.

If the rock around a piece of protection is crumbly or loose, it can break under force, pulling your piece from the wall and potentially endangering your belayer too.

Prevention

Practice placing gear with a mentor or guide who can give you specific, actionable feedback. Learn to assess rock quality and avoid placing “mental” pro—pieces that will likely rip out in a fall.

Make trad anchors redundant by placing three or more solid pieces of gear, and avoid placing all of your anchor pieces behind the same block, even if it looks completely attached. Inspect your cams regularly for evidence of trigger wire fraying or sling damage.

Bolt failure

In most popular climbing areas, bolts are replaced as needed by a climbers’ coalition or access group. But bolts and hangers can pull out of the wall, especially on less popular routes.

How it happens

On two-piece mechanical or expansion bolts, the nut and washer that secures the hanger to the threaded bolt shaft can become loose with repeated loading, loosening the hanger. Left unchecked, the hanger will eventually fall off of the bolt.

The modern bolting standard is one piece glue-in bolts: they fail far less regularly since they do not come apart and they are less likely to corrode. Unfortunately, older climbing areas are more likely to have been developed with mixed-metal coatings, and those bolts can rust in their holes. In these very rare situations, the hanger may look fine but the bolt in the rock might be completely corroded. This kind of corrosion was the source of a 2010 accident in Index, Washington.

Prevention

If climbing in an area with mechanical bolts (common nearly everywhere in the United States), carry a small crescent wrench—many nut tools have built-in wrenches. Tighten bolts if you feel the hangers spinning or twisting on their bolts. If you plan to climb in a less popular area, research forums about the area to find out which routes are commonly climbed and updated.

Carabiner breakage (levering, nose hooking)

Modern carabiners are very strong in most orientations. But when loaded incorrectly they can bend out of shape or break completely.

How it happens

When levered against an edge or loaded over the nose, carabiners can break. “Nose hooking,” which occurs when the rope runs over the “nose” of the carabiner (the point where the basket meets the gate), preventing the gate from completely closing and isolating the force of the fall at this weak point. The nose of a carabiner can also get stuck on a bolt hanger, stopper wire, or sling. When nose hooked, carabiners can fail at forces as low as 2 kN. Carabiners are also weakened when levered over an edge in the rock.

Prevention

If you see a nose hooked carabiner, reorient it immediately. Several carabiners have broken due to nose hooking, including my partner Harrison’s, but also because of less-obvious levering. Levering can occur when two carabiners are clipped into the same bolt hanger (if loaded, the top carabiner is more likely to break), or, more commonly, when placing protection the carabiners can lay awkwardly against protruding rock features. Extend pieces of protection as needed to prevent levering.

Toprope solo device failure

Toprope soloing has exploded in popularity for rehearsing highball boulders, climbing multi-pitches quickly, and getting pitches in without a partner. But climbing alone is inherently risky.

How it happens

All four toprope soloing accidents reported in the ANAC during the last three years occurred when climbers used only one progress capture device. When these devices are jammed or incorrectly loaded, they can become unclipped or fail to “grab” the rope. Without a backup, climbers can fall to the ground.

Two accidents involved the use of a Petzl SHUNT, a discontinued device designed to be a rappel back-up. When the rope above the device goes slack, the SHUNT can disconnect from the rope completely. If the SHUNT is used without a backup, a disconnection here means that the climber is now free soloing.

In a separate accident, a climber using a single Petzl Micro Traxion fell 30 feet to the ground after a sling jammed in the device, blocking its teeth and preventing it from “grabbing” the rope.

Prevention

In all of these accidents, a second progress capture device would have kept the climbers safe. Redundancy is a key part of any climbing system.

It’s also critical to follow manufacturers’s instructions when using a new piece of gear. Social media personalities are constantly introducing “innovative” and efficient-seeming ways to climb, but qualified guides and gear manufacturers are far more reliable. Petzl has repeatedly discouraged climbers from using any of their products as singular protection devices when toprope soloing, and heeding this instruction could have prevented several accidents.

***

After a few months to recover from spinal surgery, Harrison’s climbing hard again. But we’re both a bit more careful, whether we’re clipping bolts or plugging gear.

The post “Nose Hooking” Broke My Partner’s Neck. Here’s How to Avoid This and More Freak Accidents. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Index, Washington, has all sorts of tight-lipped lore, some of it deserved. But modern route developers are changing its tone.

The post Why America’s “Most Gatekept” Climbing Area is Becoming More Popular appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

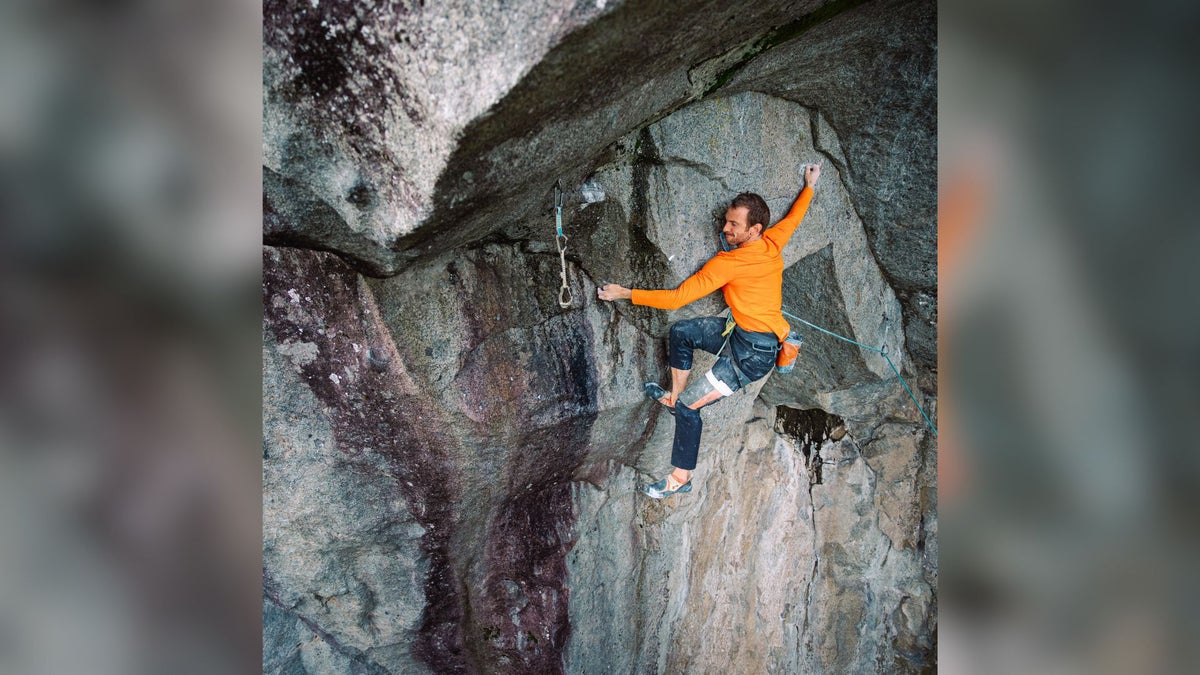

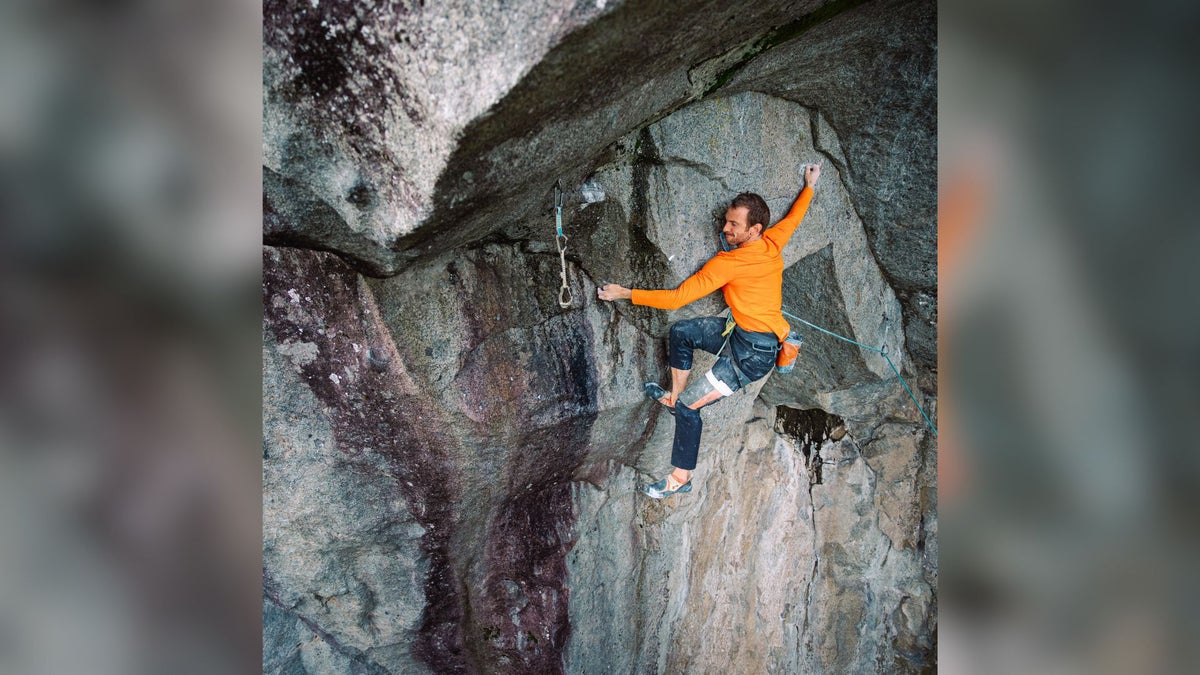

If you’ve heard anything about the climbing in Index, Washington, you’ve probably heard that it’s hard. The strongest person you know raves about it; the hardwomen you met bivying in the boulders behind Camp 4 head there as soon as Yosemite gets too hot. Alex Honnold says it’s home to the world’s hardest 5.11d, Natural Log Cabin. (And that’s not even the hardest 11d there!)

But some of Index’s strongest locals are at the forefront of efforts to make the area more accessible, too. They are establishing moderate routes, making the area easier to navigate with signs and guidebooks, and working to develop an amicable relationship between transient climbers and local residents. Stamati Anagnostou—a member of the Index Climbers’ Coalition, a visionary route developer, and the author of one of Index’s hardest gear lines, The Quad Crack (5.14a)—is leading the way.

Anagnostou, who began climbing in Index in 2014, embodies the imperative to try hard but stay humble. When I first met him at the base of Godzilla (5.9), one of the Lower Town Wall’s most popular routes, he cut an unsuspecting figure in faded black skinny jeans and a floral button-down. We got to chatting—Anagnostou never seems to tire of meeting visitors to his home crag—and I was surprised when he grinned with recognition at my mention of Endless Skies (5.12d), a seldom-repeated sport climb located two pitches up in an overgrown corner of the Upper Walls. I asked if he’d been on the route. He said yes, but didn’t elaborate. Later, scouring the internet for beta, I’d recognize his name on the route’s Mountain Project page. He had equipped the route and competed with Michal Rynkiewicz for the first ascent.

Anagnostou doesn’t just surround himself with 5.14 crushers and longtime locals. Eager to learn about my progress on his obscure route, he invited me and a few friends to his house for dinner. He’s lived in the 150-person hamlet of Index since 2023, and the four-room clapboard bungalow he shares with his partner, Huck, is furnished cozily in greens and browns. He’s a generous dinner host, tall and rangy in the galley kitchen. He has a high-pitched staccato laugh that erupts easily and doesn’t match his slow, considered way of speaking. He’s passionate about this town: he writes for the local newspaper; he and Huck run community clean-up events; they’ve established a climbers’ collective who help organize an annual climbing festival. Whenever he isn’t climbing, it seems, he’s thinking about ways to preserve his beloved climbing area.

Locals—especially people who have spent their whole lives in Index, or whose families have lived there for generations—are often skeptical of visitors, and Anagnostou can’t blame them. It’s hard to sympathize with the tourists who vandalize the public restrooms, spray paint trees on the UTW trails, or speed down Index Avenue to beat the traffic on Highway 2. Locals are also wary of alien opportunists looking to buy up the town’s very limited housing and develop short-term rentals, driving up the cost of living and stifling the growth of a local community. Understandably, many of Index’s residents want to see a benefit from the uptick in tourism, which has exploded in part due to the publication of a climbing guidebook in 2017 and the publicity that Index climbing has received in publications like this one. So when locals have felt like visitors are offering little to the area except for the graffiti and litter they leave behind, discontent has boiled into yelling matches at town council meetings.

In Index’s early days, “developers balked at grading their routes 5.12 for fear of getting downgraded,” Anagnostou says. Anything hard got 11+, and many of those grades haven’t changed to meet contemporary standards. (The 5.12s, 13s, and 14s are graded a bit more honestly.) So if you come to Index to chase grades, you might be sorely disappointed.

This sandbagging, Anagnostou reasons, might contribute to Index climbers’ reputation for gatekeeping. Not to mention that neither the climbing style nor the environment lend themselves to successful short trips. During the drier months, May through July, it rains about every two days. You might find your project covered in fast-growing moss that takes days to scrub off. And you’ll need to get used to trusting smeary feet on the fine-grained granite. So, on the rare days when the weather is good and the walls are dry—the theory goes—perhaps the locals are a little crankier about sharing the crag than their neighbors in, say, Squamish or Smith Rock.

Even so, climbers have flocked to Index as word has gotten out about the area’s dreamy high-friction granite, and Anagnostou welcomes the area’s growing popularity with more sincerity than I’d expected. He sees growth as an engine for route development and attention from conservation groups that might help protect local climbing. “Engagement drives conservation, and there are so many people doing work to further climbing in Index [right now].” Index climbers’ reputation for gatekeeping, he says, is dated and overblown: “I don’t think we really ever experienced the thing of Index being hush-hush.” Instead, the close-knit community he found there in 2014 welcomed him quickly.

Anagnostou may very well benefit from the “strong-climber effect”—those pushing hard grades, or developing new routes (especially if they’re men, and white), are usually welcomed into established climbing communities pretty quickly, even small communities in out-of-the-way areas. What about everyone else?

I can weigh in on the ordinary Index climber’s experience here. My credentials? I’m pretty solid around 5.10 on gear, and I project bolted 12s. My footwork is underdeveloped after years of climbing in the gym and on sandstone, and I start to panic when my last piece is about knee-high. I am also a woman, who usually travels alone, which means I don’t necessarily “fit” into male-dominated climbing areas—and I certainly don’t blow everyone away with my climbing prowess. Usually, I have to make a focused effort to find community when I arrive in a new place.

In Index, I made friends almost immediately. It helps that there’s a single parking lot, the Wagon Wheel, where most traveling climbers camp. Every evening, climbers—a heartening number of them women traveling alone, like me—would emerge from campers, vans, and built-out sedans to share dinner and chat. Finding climbing partners was easy and spontaneous, whether I wanted to try hard or excavate a dirty 5.7 with a wire brush. The locals, like Anagnostou, were welcoming; the weekend visitors were respectful. Developers invited people to try their new climbs with handwritten signs posted in the parking areas and at the trailhead.

Index’s reputation for gatekeeping remains, but climbers who frequent the area don’t seem to take it very seriously. In recent years, I’ve started seeing bright yellow “Index is choss” stickers on Thules and Sprinters from Squamish to Joshua Tree. The message is tongue-and-cheek, a parody of the secretive, selfish climbers that I have yet to find in Index.

Like the other climbers I met in Index, Anagnostou has a thoroughly considered climbing philosophy. Perhaps all the thinking that happens here has to do with the moody weather (183.7 rainy days in 2024!), which drives climbers inside to consider their sport on days when they can’t actually practice it. Maybe the philosophizing comes in place of blind ambition, which is stifled by the area’s baffling grades.

His development ambitions aren’t solely connected to his personal climbing goals. In our conversations, Anagnostou challenged the norm around first ascents—that commonly accepted rule that if you equip a route, you get to do it first, no matter how long it takes. Ben Gilkison bolted the anchor on The Quad Crack. Following Anagnostou’s first ascent of the route his friend rediscovered and equipped, Anagnostou is considering opening his own routes up to other first ascentionists. “I’m not an amazing climber or anything; it’s going to take me a long time to do some of these things,” he said of the handful of routes he equipped recently, the easiest of which is likely 5.13+. “Do I want to close them off to the world for the next five years so I can have the feeling of doing it first?”

Still, a few routes are too inspiring for Anagnostou to relinquish quite yet. Right now, he has a few projects that he still hopes to climb first. He grows excited telling me about The Slug Within, a sport route with a scrunchy roof traverse on smearing feet and directional edges, and Osiris, a technical face of charcoal granite he’s still working on. But to unlock the full potential of Index’s upper walls, he’ll need to enlist someone stronger. “Ryan [Hoover] and I accidentally bolted maybe a 5.15, a 35-degree shield for 40 feet that’s just slopers. It doesn’t look possible to me, but I bet someone could do it.” On future development prospects, he added, “There’s potential for stuff that’s the hardest in Washington, maybe the hardest on the West Coast.”

Anagnostou, Gilkison, and a handful of other influential developers are driving this shift in Index’s ethic toward bolting for safety, establishing more sport climbs, and publicizing new routes, which Anagnostou hopes will draw the emerging generation of elite climbers to the Northwest. “It’s an act of trust to let people get on your routes,” he admits, but he’s excited to draw strong climbers to Index by bolting routes beyond his own ability.

If you find yourself in Index, Anagnostou and his fellow developers hope you will bring a good deal of humility and a sense of adventure. And, maybe, a wire brush.

The post Why America’s “Most Gatekept” Climbing Area is Becoming More Popular appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

El Potrero Chico, or "the little corral,” is a bolted limestone playground

The post Bolted Big Walls? In Mexico? Yes Please. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

The cracked pavement gave way to dusty gravel as we rode away from Monterrey. Mountains shrouded in mid-afternoon haze from the nearby Cemex cement plant loomed over our little car. As we approached El Potrero Chico, the vertical limestone buttresses—some over 2,000 feet tall—came into focus. Soon, we could see climbers like insects in brightly-colored puffy jackets scaling the faces between thickets of wild agave and prickly pear cactus. Despite being exhausted after days of travel, we rushed to join them.

El Potrero Chico, or “the little corral,” is a bolted limestone playground located just outside the small town of Hidalgo in Nuevo León, Mexico. Hidalgo grew around the Cemex plant, established in 1906, but when climbers began flocking to the nearby mountains the local economy shifted to rely largely on tourism. Today, Hidalgo boasts large outdoor markets, restaurants, and grocery stores, all within walking distance of the park entrance.

Texas climbers Jeff Jackson, Kevin Gallagher, and Alex Catlin began bolting projects in El Potrero Chico in the early 1990s, shortly after sport climbing became popular in the United States. Some routes have not been rebolted since their original development, but most classics have seen frequent maintenance. A sign at the park’s entrance claims that the park hosts “the first big-wall climbs in Latin America.” Despite this grand proclamation, all the multipitch routes in the canyon can be completed in under a day by an experienced party.

The Climbing

El Potrero Chico boasts dozens of long multipitch sport routes with generous bolting and short approaches. The road to the canyon is paved, and approaches to many classic routes, such as Estrellita (5.10b, 12 pitches) and Space Boyz (5.10d, 11 pitches), involve little more than a short stroll on a sidewalk. An efficient party can easily get 1,000 feet above the deck before lunchtime, rappel for tacos at the park entrance, and do it again in the afternoon.

Most routes are entirely fifth-class. The limestone lends itself to techy vertical climbing, with cruxes that demand thoughtful problem-solving rather than power. Often, a sequence that appears impossible from the ground is unlocked by arranging your body in an improbable position on small footholds and high-stepping to a hold you hope is positive. Expect a calf burn!

Moderates are riddled with directional jugs that look like slopers and crimps from below. With patience, you’ll learn to recognize good holds and move your body to use them.

Route spotlight: Yankee Clipper (5.12a, 15 pitches)

Many people skip the final crux pitch of this classic, making for a variation comprised of three varied, thought-provoking 5.10 pitches: one sustained, vertical pitch with technical sequences on pockets down low, one steep jug-haul with a distinct high crux, and one wide, closed-in dihedral that demands a few moves of chimney technique and emerges above nearly 1,500 feet of exposure. The crux pitches are distributed rather evenly between 11 more pitches of 5.8 and 5.9 romping on jugs with the occasional techy sequence. Most of the pitches can be linked with a 70-meter rope and 20 draws.

The main drawback of the area is loose rock. Even the most repeated classics have several loose holds or sections, and those that top out often do so on teetering piles of choss. Because of this, we put helmets on as soon as we approached the base of the cliff and kept them on until we were on the ground and out from under populated climbs. Most loose blocks are either obvious or marked with an X, but be gentle when pulling on flaky jugs as some chalk marks may have worn off. When rappelling, saddle-bagging or coiling rope over your shoulders is preferable to throwing the rope to avoid dislodging loose rocks. Some have reported rockfall from pulling on stuck ropes tossed to rappel. Since most routes descend with multiple rappels on the same anchors used to climb, this could present a danger to your partner or other parties below you.

The vertical climbing does not lend itself to comfy belay ledges, and you’ll find yourself coiling the rope in your lap on most multipitch routes. Familiarize yourself with this technique to avoid becoming mired in a rat’s nest or short-roping your leader. If you’re worried about back pain from sitting in your harness all day, consider investing in an inexpensive big-wall harness. These are bulkier and better padded than traditional sport climbing harnesses, and many boast extra gear loops, which may be useful if you’re bringing large racks of quickdraws to link pitches.

In addition to El Potrero Chico’s notorious multipitch routes, the area boasts some stellar single-pitch climbing. The TNT wall features steep pocket climbing ranging in difficulty from 5.8 to 5.12a. For a gentler introduction to climbing on limestone, the Virgin Canyon is home to dozens of three- and four-star climbs in the 5.8 to 5.10- range.

Logistics

When to Go

The main season for climbers is winter, between November and March. During this time, the weather—usually in the 60s or 70s during the day, with nights dipping into the 40s—lends itself to long days out at sunny and shady crags alike. Local hostels and campgrounds are also dense with climbers from all over the world, making it easy to find a partner. During the summer, locals descend on the canyon to party and frolic in a nearby waterpark. If you visit during the summer, plan to seek shady crags and bring lots of water up long routes.

Gear

- Rope: A 70-meter rope is mandatory for many rappels and if you plan to link pitches. Some single pitches on classic routes, such as Pitch Black, are over 30 meters long.

- Draws: Bring at least 16 quickdraws, and up to 30 if you plan to link pitches.

- Anchors: For multipitch transitions and rappels, bring some anchoring material to place on hangers or chains. I like tying a quad on a quadruple-length sling and attaching it with two non-locking carabiners. My partner favors a cordalette and small lockers.

- Belay device: Every route descends with multiple rappels. My partner and I prefer pre-rigging and rappelling one at a time with a tube-style device extended on a sling and a third hand. Many people choose to simul-rappel with assisted braking devices like GriGris. If you choose this technique, make sure you understand how to mitigate its inherent risks.

- Helmet: Because of the loose rock on nearly every route, a helmet is mandatory.

- Guidebook: The most up-to-date guidebook is Frank Madden’s EPC Climbing 3rd edition. The book includes detailed topos, route descriptions, and pitch breakdowns for every established route in the canyon. You can buy the book in print here. I opted for the digital version on Rakkup, which connected to the GPS on my phone so I could navigate easily. In addition, the Mountain Project entries for many routes are quite thorough, and many classics have metal tags at the base so you can verify that you’re getting on the right route.

- Forget something?: The offices at the Rancho El Sendero and La Posada hostels have small gear shops.

Language

Most of the locals speak very little English, so knowing at least the basics in Spanish may make your trip easier. That said, signs and restaurant menus usually are printed in both English and Spanish, and many of the American visitors who I met spoke no Spanish. A language barrier may make it difficult to communicate with locals, but it will not present significant barriers to getting what you need.

Getting there

From the United States, it is easiest to fly into Monterrey, then either rent a car or get a ride to the canyon. Ride services like Uber may not pick you up because of local laws prohibiting their operation at airports. If you are staying at one of the local hostels or campgrounds, you won’t need a car after you arrive because climbing and services are both within walking distance. The ride from the airport to the canyon is about an hour. On the way to the canyon, we paid 689 pesos (about 40 USD) for a taxi to the campground.

Most campgrounds and hostels in the area offer rides to and from the airport, which you can arrange when you book a room. These services usually include a stop at a grocery store, where you can buy food and get cash from an ATM. To return to the airport, we paid 1,400 pesos (about 80 USD) for a ride from the hostel to the airport. Though car services from hostels are more expensive than regular taxis, they are more reliable and therefore recommended when you have a flight to catch.

Where to Stay

The road to the park is lined with hostels and campgrounds, but most climbers stay at one of three. For an intimate community feel and the mid-priced rooms, book a stay at Rancho el Sendero. They offer a campground, hostel, and private rooms. In addition, guests have use of a large community kitchen with food storage, a pool, and a small climbing gym. Many people come to El Sendero alone, making it a great place to find climbing partners. On Saturday nights, guests can take Salsa and Bachata classes in the modest bar, and anyone can enjoy the buffet on Fridays during the climbing season. This hostel is farthest from the canyon, about a fifteen-minute walk from the park’s entrance. Rooms and campsites may be booked online.

Quinta La Pagoda is slightly closer to the canyon and has cheaper rooms than Rancho El Sendero. The hostel is a bit run-down, but a maintenance crew keeps the essentials functioning. It is a great budget option for those just looking for a place to sleep. Guests have use of a community kitchen and pool. La Pagoda is typically one of the last locations to fill up during peak season.

La Posada is a bit newer than the other two options, with modern and well-maintained facilities, including a pool and a gear shop. If you plan on a longer visit, La Posada might be the best budget option, as they offer a 50 percent discount to guests staying for more than 30 nights.

Eating

The food in El Potrero Chico is delicious and cheap. The road to the park offers several barebones taquerias, where you can recover from a long climbing day over colossal margaritas and endless chips and salsa. For a more substantial meal, Leo’s tacos grill offers an unlimited buffet of rice, beans, tacos, and meat for around $15 per person. On Fridays, the buffet at Rancho el Sendero offers a lavish spread of traditional Mexican dishes, salad, and pizza. Vegetarian options are easy to find everywhere. Most restaurants only take cash, so get pesos from the ATM in Hidalgo before visiting.

For groceries, visit one of several small grocery stores in the town of Hidalgo, about a 40-minute walk from the canyon. On Tuesdays and Fridays, a market in the town center attracts climbers and locals. Here, you can buy local produce and fresh-cooked meat, as well as clothing and household items.

El Búho, a cozy American-run coffee shop in Hidalgo, has been a fixture in the climbing community since it opened in 2010. In addition to great coffee and pastries, the coffee shop operates a book swap to benefit local public schools. It’s a great place to go for information about the area from knowledgeable English-speaking employees.

Recommended Moderates

The good multi-pitch climbing generally starts at 5.10. For a gentler introduction to the area’s climbing, begin on easier single-pitch routes.

- Zombie Wolf, 5.8

- Cat Daddy, 5.9

- Mr. Fluffer’s Wild Ride, 5.9+

Recommended Multipitch Routes

Note that the sharp limestone edges can feel assertive at first, but become manageable with good body positioning and footwork.

- Five Pitch Harmony, 5.9, 5 pitches

- Will The Wolf Survive? 5.10a, 4 pitches

- Excalibur, 5.10a/b, 6 pitches

- Yankee Clipper (minus the last pitch), 5.10b, 14 pitches

- Estrellita, 5.10b/c, 12 pitches

- Pitch Black, 5.10d, 6 pitches

- Snott Girlz, 5.10d, 7 pitches

- Space Boyz, 5.10d, 11 pitches

Also Read

- The Best Harnesses for Hard Sport and Long Days in the Alpine

- Beth Rodden was a Visionary Yosemite Climber. Now, She Introduces the Rest of Herself

- Why Do So Many Climbers Not Wear Helmets?

The post Bolted Big Walls? In Mexico? Yes Please. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

These climbers—many of which are women of color—are claiming space in climbing media by showcasing their vulnerability.

The post The Climbing TikTokers I Can’t Stop Watching appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

“You know what’s annoying? Regressing. At least I look cute though!” Sophia Duong, 30, smiled into the camera of her phone as she spoke. Duong had just fallen off the committing last move of an orange V5 in the gym—again. She tosses a boulder brush to the ground and gets back on.

When she started posting on TikTok under the handle @sophiachalks in 2021, Duong felt that the platform was lacking a core part of the climber experience; rather than showing a range of outcomes and emotions, she found a homogenized pool of send videos. “I was like, ‘you guys, we fall so much more often, let’s be real here.’” Duong decided to post videos on her platform that included everything from falling to sending to rest-day FOMO.

I came across Sophia’s content in a mindless TikTok scroll one afternoon. Usually, my homepage is saturated with videos of professional climbers sending otherworldly boulders, wiry men doing front levers on ten-millimeter crimps, and the like. I’m inspired to see what’s possible at the most elite level of the sport I love, but amidst the deluge of superhuman ability, Duong’s video was refreshing. Commenters tend to agree. On a video of Duong working a scary top-out, they’ve left messages like “you always give me the inspiration to work on my projects” and “you’re killing it!” Duong is one of several climbers—many of which are women of color—claiming space in climbing media by showcasing their vulnerability.

Tiffany Gomez is a 25-year old climber from Washington, D.C. She started climbing about a year ago to connect with a friend. Gomez was apprehensive during her first few trips to the climbing gym: “I didn’t like being alone,” she says. “When I first started climbing I was a little bit intimidated because everyone was so good and I was just kind of awkward.” Worried to fail in front of more experienced climbers, she meticulously planned trips to the climbing gym around avoiding human contact as much as possible. She went to the gym when it was emptiest, early in the morning, and left as soon as people began trickling in.

Despite the intimidation that plagued those early trips to the climbing gym, Gomez told me, “climbing was the only time when my brain wasn’t anxious.” Looking to build community online, Gomez turned to TikTok in search of videos by beginner climbers like herself. She struggled to find anything relatable. “I was watching all these TikTok videos and they were all people who were really good. I was like, oh god. It looks like no one is just starting.”

Another climbing content creator, 30-year old Jocelynne Flor from Toronto, expressed a similar feeling of isolation. Flor remarked, “When I was first starting out, I would search ‘beginner climbing’ on TikTok or on Instagram and the only thing that I could find was tips for beginners from coaches or pros.” While advice videos were helpful, Gomez and Flor both felt that content about the more intimate aspects of being a beginner —the fear of falling, the satisfaction of a hard-earned send, the intimidation at new climbing gyms and crags—was missing.

Gomez began posting on TikTok shortly after taking up climbing. At first, she said, “it felt wrong because I have no idea what I’m talking about.” Instead of training programs or beta breakdowns, Gomez talks about how it feels to be a beginner climber. She makes memes out of her fear of falling, which has taken lots of hard work to overcome. She shows herself slipping and struggling. Soon after she started posting about her climbing, Gomez received a flood of positive comments. Other beginners confided in her that they considered quitting rock climbing before seeing her videos, which helped them recognize that other people were just starting out, too.

Now, Gomez sails through the climbing gym without trepidation and posts about proud moments and failures alike. In a recent video, she locks off on the slopey starting holds of a steep boulder problem and slaps at the second hold for a while before falling to the padded floor, cackling at her inability to stick the move. The caption reads, “I love petting slopers.”

Jocelynne Flor posts about her climbing “for people who are beginners or who climb alone.” Her videos range from post-climbing meal inspiration to face-to-face confessionals about anxiety in busy climbing gyms to beta breakdowns. In many of her videos, Flor encourages her 10.5K followers to try new things, which she notes can be difficult for adults: “Mostly because I’m in my 30s, I feel like a lot of people in their late 20s and early 30s are afraid to try something new. As an adult you just want to stick to what you’ve known.”

In an early video, Flor works to get over her fear of slab climbing. She works moves on a “dreaded V2 slab,” a problem that begins on two-finger pockets and sloping footholds before creeping up a series of directional volumes. She flows through the bottom half of the climb and then freezes at the final move, a committing sideways step with no handholds. She explains in voiceover, “I’m still just so scared to grab that last hold, but I’m working on it.”

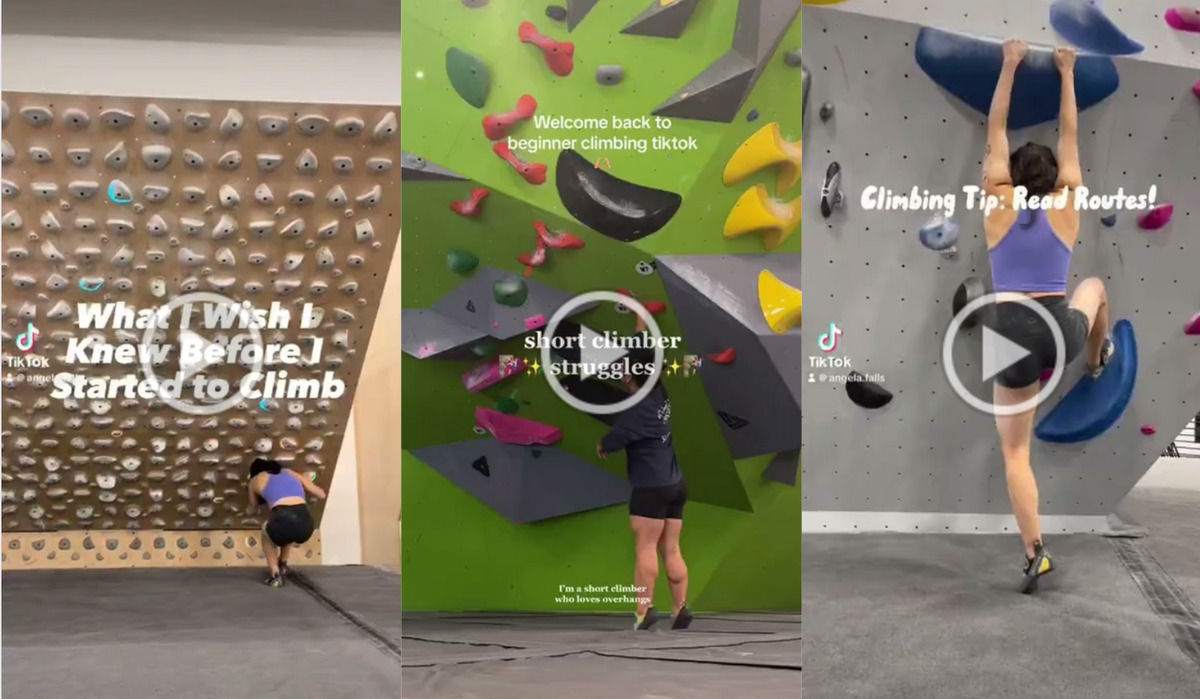

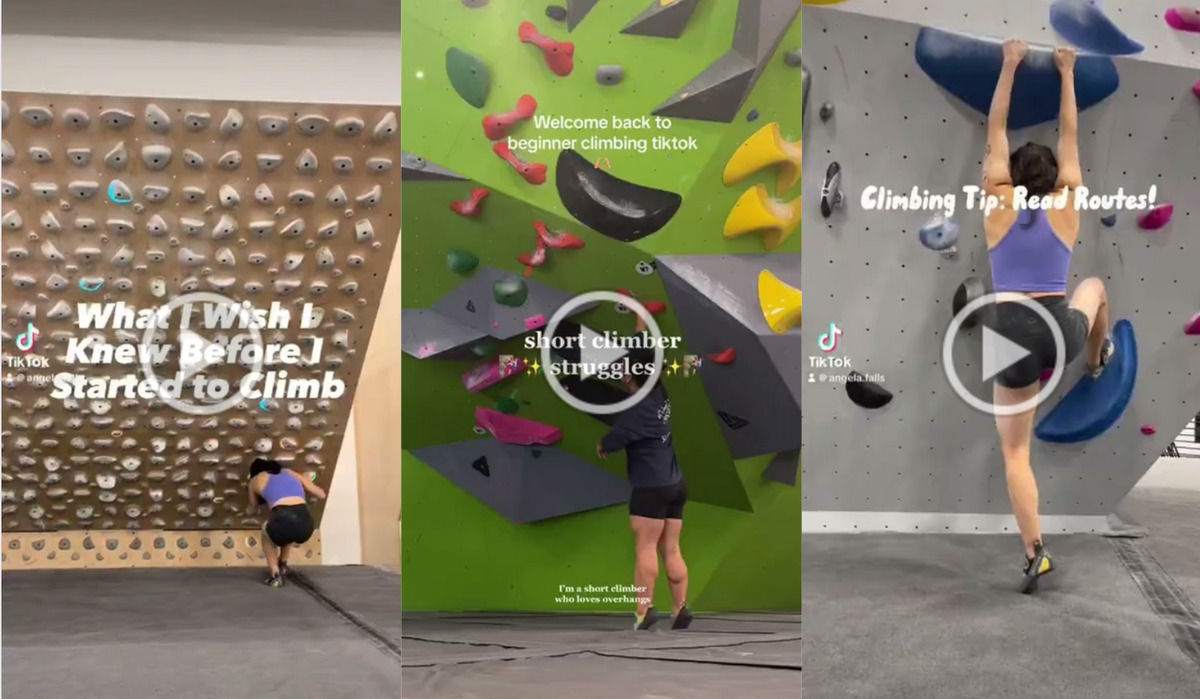

Angela Park is another content creator aiming to change the status quo of climbing media. A climber of eight years, Park posts the kinds of things you’d expect—beta breakdowns, outdoor sends, and strength training drills—interspersed with vulnerable moments and life advice that her 1.4K followers can use off the wall.

Park told me that her beta breakdowns are among the most popular of her videos, and I can see why. She uses these videos, in which she voices over clips of her climbing, to deliver thoughtful analyses of her strengths and weaknesses that other climbers find useful. In one such video, she says, “I make it a point to try and change something every attempt.” Being a smaller climber, she finds alternative beta for reachy moves. Her climbing style has evolved over the years: While she initially avoided powerful movement in favor of techy crimping, she now sometimes finds dynamic alternatives where taller climbers move statically.

Park sees herself as part of a broader movement toward diversity in climbing media, saying “I feel really passionate about women taking up space in climbing, I feel like women of color are particularly underrepresented.” By sharing her own struggles, as well as demystifying climbing etiquette and culture, Park hopes to encourage other climbers—especially those who don’t find themselves represented in mainstream climbing media—to push themselves. “It’s a really cool time to be a climber,” she says. “So many more people are getting into it, you see more diverse bodies, which is sick. More people isn’t always a bad thing.”

Though Park has been climbing for more than eight years, she uses her platform to dispense advice that new climbers will find useful. In a video titled “What I Wish I knew Before I started to Climb,” she talks about how trying intimidating climbing styles and getting comfortable with falling was crucial to her progress.

The creators I interviewed were often surprised at how meaningful their content was to fellow climbers. “A lot of people message me really long paragraphs…I get messages that almost make me cry, make me think, ‘wow, I can’t believe that this seven-second meme with a Spongebob quote is relating to people,’” Duong said.

Climbing is scary, frustrating, physically taxing, and, sometimes, joyous and rewarding. By showing that the joys of climbing can be had at any level, these TikTokers are inviting people who have not been represented in mainstream outdoor media to see themselves as climbers.

The post The Climbing TikTokers I Can’t Stop Watching appeared first on Climbing.

]]>