Steven Potter is a digital editor at Climbing. He’s been flailing on rocks since 2004, has successfully injured (and unsuccessfully rehabbed) nearly every one of his fingers, and holds an MFA in creative writing from New York University.

This isn't a guide to 2025's flashiest new kicks. These are the shoes we return to when we’re not testing the latest and greatest.

The post Our Favorite Sport Climbing Shoes (Updated 2025) appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Most gear roundups cover new releases. When a company designs a new suite of shoes, they send pairs to us and our testers, and we climb in them, compare notes, write a review, and then, later, do a roundup of the latest and greatest releases of the year. The problem with this model, however, is that it focuses only on what’s new rather than celebrating the gear that holds up to the test of time. So we thought we’d compile a list of our favorite sport climbing shoes—the shoes that our editors and testers choose to climb in when we’re not testing new shoes.

Building the first version of this list was simple: we simply asked ourselves which shoes we wanted included, then pulled from the reviews we’ve written over the years. Updating it this year was also simple: we just looked at what we’re wearing and what we’d put aside.

Here are our top 10 sport shoes. All of these shoes are excellent, and all of them have slightly different functions, so we’ve opted not to impose any rigid ranking. We’ll be updating this list as we fall in love with more shoes.

—Steven Potter & Anthony Walsh

- Also read: The best new shoes of the year

The post Our Favorite Sport Climbing Shoes (Updated 2025) appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

The world’s second highest peak remains much more difficult and dangerous than Everest, but it’s rapidly commercializing. For true adventure, look beyond the mountain's standard routes.

The post Is K2, the “Savage Mountain,” Becoming Less Savage? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

K2 (8,611m / 28,251ft) is the world’s second highest mountain, after Everest (8,848.9m), and has traditionally been considered the most difficult of the world’s 14 8,000-meter peaks. It has been referred to as The Savage Mountain since 1953, when American climber and physicist George Bell, who’d nearly perished in a six-man fall on the mountain, told reporters, “It’s a savage mountain that tries to kill you.”

Until recently, the mountain’s death-to-summit ratio has paid honor to that name. K2’s historic fatality rate has been above 20 percent, making it one of the most perilous high altitude mountaineering objectives in the world, comparable only to Annapurna I (8,091m), which historically had a death rate above 30 percent, and Nanga Parbat (8,126m), whose death-to-summit ratio traditionally hovers around 21 percent.

But while K2’s height and technicality have traditionally deterred the amateur mountaineers that flock to “easier” mountains like Everest, commercially guided expeditions have swarmed K2’s summit in recent years. Up until 2021, just 377 climbers had stood on its summit, and the one-year record was 62 summits in 2018. In 2022 alone, however, 200 people summited, 145 of them in a single 24-hour period, and only two climbers died. And 2023 saw one death for an estimated 112 summits. These years have drastically lowered the K2’s overall death rate from 25 percent in 2021 to approximately 13 percent—and they’ve led to a widespread reconsideration of K2’s viability as a guided trip. “The Everest model is now official on K2,” Himalayan chronicle Alan Arnette wrote in a July 2022 blog. “I [once] wrote that K2 would never become Everest … I was wrong.”

At the same time, however, the mountain remains dangerous. Overcrowding on the peak is becoming a concern, especially in the standard route’s technical sections—like the Bottleneck (see below)—which lend themselves to traffic jams.

Increased traffic from guiding companies has also heightened some of the ethical concerns that often accompany high-altitude climbing and labor. This was made especially apparent by an incident in July 2023, when a woefully under-equipped and under-trained porter named Muhammad Hassan collapsed high on the mountain. The media pounced at allegations that dozens of summit-blind climbers walked past Hassan while he lay dying; though later reports suggest that high-profile climbers like Kristin Harila did render aid. Pakistan’s government launched an investigation and ultimately banned Lela Peak Expeditions, Hassan’s employer, from guiding in the region for two years.

Guided or not, K2’s upper slopes are one of the least hospitable places on earth. And for anyone who wants to escape the crowds, the mountain is also host to nearly a dozen existing but rarely attempted routes, many of which climb from the mountain’s frighteningly remote Chinese side. There are also a number of potential first ascents awaiting the very best and bravest high-altitude climbers.

K2’s Climbing History

Survey and Name

Originally surveyed by the British Great Trigonometrical Survey of India in 1856, the mountain was christened K2 since it was the second main peak in the Karakorum that they mapped. The other principal Karakakorum summits were originally named likewise (K1, K3, K4, and K5), but the surveyors later cast around for local names, and today these peaks are known as Masherbrum (7,821m), Gasherbrum IV (7,925m), Gasherbrum II (8,035m), and Gasherbrum I (8,080m), respectively.

K2’s name, however, has stuck—in part because, thanks to the mountain’s remoteness, surveyors were unable to identify a local name. The name “Chogori”—a mashup of two Balti words that separately mean “big” and “mountain”—may have been invented by Western explorers in the early 20th century, but it seems to have little local usage. Chinese administrators in Xinjiang, however, call the peak “Qogir,” which they derived from “Chogori.” Early K2 expeditions

The 1902 Northeast Ridge Expedition

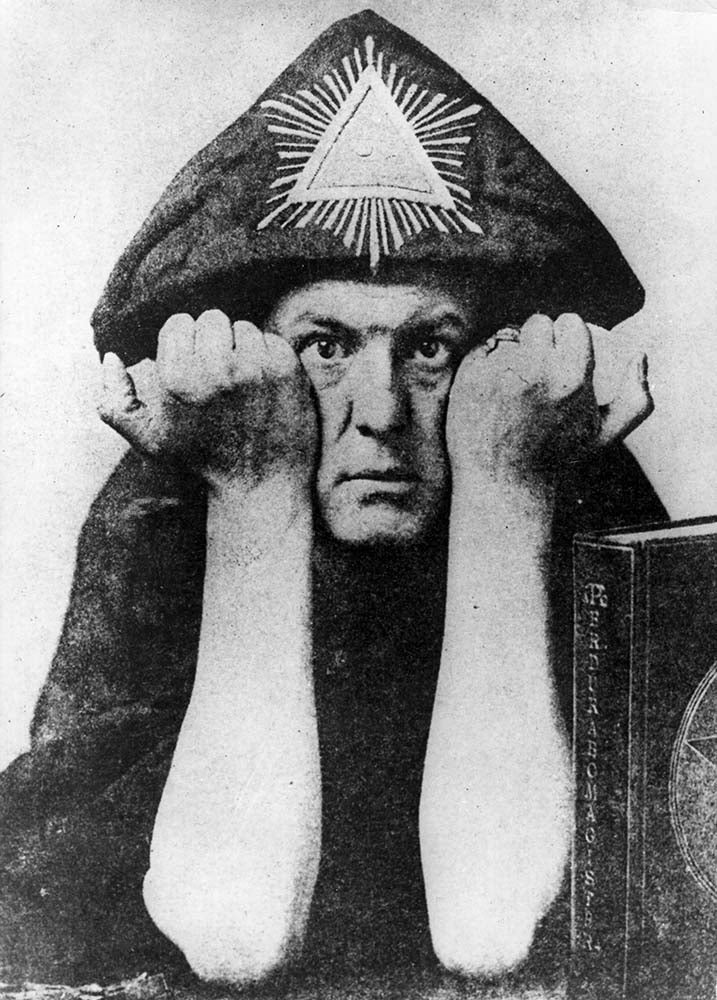

The first climbing expedition to K2 was in 1902 and was spearheaded by Oscar Eckenstein and notorious occultist Aleister Crowley, who was accompanied by Guy Knowles, Jules Jacot-Guillarmod, Heinrich Pfannl, and Victor Wessely.

The team approached the mountain from the Chinese side and attempted the Northeast Ridge, battling brutal weather during their 68 days on the mountain. They reached approximately 6,525 meters (21,407 feet) after five attempts, setting a record for the longest period spent at such a high altitude. Following the failed expedition, Crowley notably declared that the Southeast Spur (now called the Abruzzi Spur), not the Northeast Ridge, was the mountain’s most viable line of ascent. This was the route eventually used by the peak’s first ascensionist and is today considered its easiest route.

The Northeast Ridge wasn’t successfully climbed until 1978, when four Americans under the leadership of Jim Whittaker—Louis Reichardt, Jim Wickwire, John Roskelley, and Rick Ridgeway—finally navigated the long and corniced ridge. In the process, Reichardt and Ridgeway became the first two climbers to summit the mountain without using supplemental oxygen. And Jim Wickwire survived one of the highest exposed bivouacs in mountaineering history, spending the night in a shallow hole just 500 feet below the summit. (Reichhardt wrote an excellent report about the expedition in the American Alpine Journal.)

The 1909 Italian Expedition

Luigi Amedeo, an Italian polar explorer and Duke of the Abruzzi, led the second expedition to K2 in 1909, approaching the mountain from the south (Pakistani) side. When the team was driven back from the eponymous Abruzzi Spur after climbing to 20,500 feet, they retargeted their efforts on first the peak’s west and then northeast ridges but failed on both. The peak wasn’t tried again until 1938, when an American attempt led by Charles Houston reached 26,000 feet on the Abruzzi Spur only to be turned back by foul weather and dwindling supplies.

Death Comes to K2

During the 1939 American Karakoram Expedition to K2, Fritz Weissner and Pasang Dawa Lama climbed to within 600 feet of the summit (avoiding the Bottleneck feature by climbing the steep cliffs to its right), but the expedition ended tragically. Climber Dudley Wolfe was left stranded high on the mountain due to a series of miscommunications. Several attempts were made to rescue him, and though the rescuers reached him on their second attempt, Wolfe was dehydrated and hypoxic and refused to accompany his rescuers on a descent. During a third and final attempt to get him off the mountain, three Sherpas, Pasang Kikuli, Pasang Kitar, and Phinsoo, disappeared high on the mountain. Their bodies were never found.

Another American expedition in 1953, led again by Houston, saw the team trapped for 10 days at 25,590 feet amid a violent storm. During the storm, one of the men, Art Gilkey, developed thrombophlebitis, a life threatening blood clot condition caused by altitude. The team immediately gave up on the summit and began trying to get Gilkey to safety. They wrapped him in a sleeping bag and began lowering him through snow and 80mph winds. During that first day, Pete Schoening made one of most famous belays in mountaineering history, catching a six-man fall on a hip belay. Shortly after that, however, Art Gilkey—still in his sleeping bag—simply disappeared. Some believe that he was swept off the mountain by an avalanche. Others conjecture that he untied from the rope and slid himself off the mountain in order to make the descent safer for his teammates.

The first ascent of K2

K2 was finally summited on July 31, 1954, by Italian climbers Lino Lacedelli and Achille Compagnoni via the Abruzzi Spur. The expedition was led by Ardito Desio and also included Pakistani colonel Muhammad Ata-Ullah, Hunza porter Amir Mehdi, and prominent climber Walter Bonatti. One member, Mario Puchoz, died of pneumonia.

Though successful, the expedition created one of the great dramas of high altitude climbing history, when Compagnoni and Lacedelli established their high camp (Camp IX) at an elevation nearly 1,000 feet higher than originally agreed with Mehdi and Bonatti, who were to portage Compagnoni and Lacedelli’s oxygen tanks up to high camp prior to their summit bid. By the time Mehdi and Bonatti reached the new drop point, it was too dark to descend, and the pair were forced to bivy in the open, without sleeping bags, at 26,000 feet. Both men survived, but Mehdi was hospitalized for months and lost nearly all of his fingers and toes to frostbite. It was later indicated that Compagnoni deliberately moved camp, fearing that Bonatti would otherwise carry on and summit first himself. Check out Bruce Hildenbrand’s “High Crimes On K2”, which was published by Climbing in 2022.

K2 did not see a second ascent until 23 years after Desio’s expedition, when Ichiro Yoshizawa led a Japanese team to the summit, also by the Abruzzi Spur, on August 9, 1977.

The first winter ascent of K2

K2 was the last 8,000-meter peak to see a winter ascent, which was considered one of the greatest prizes in high altitude mountaineering. The first winter attempts were in 1987 and 1988, years that saw 13 Polish climbers, seven Canadians, and four Britons shivering on the mountain’s wintry slopes. All of them failed. As did every other attempt for the next three decades. Finally, in January 2021, a 10-person Sherpa team led by Mingma Gyalje Sherpa and Nirmal “Nims” Purja took advantage of an almost mystically good weather window (summit winds were less than 10 mph, and the temperature was a relatively balmy -40 degrees Fahrenheit) and sung Nepal’s national anthem on the summit. Nims Purja was the only climber not using supplemental oxygen.

That same winter season, however, the Savage Mountain reasserted itself. Famed Spanish climber Sergi Mingote fell to his death while acclimatizing around Camp 1. Bulgarian Atanas Skatov fell to his death while descending from Camp 3. And then, finally, three especially strong climbers—Pakistan’s Ali Sadpara, Chile’s Juan Pablo Mohr Prieto, and Iceland’s John Snorri—froze to death near the Bottleneck after getting caught in a storm. Though their remains were found the following summer (by Sadpara’s son), it is still unclear whether they summited.

The first ski descent of K2

While most of K2’s greatest firsts occurred in the 1980s and ‘90s (see the list of K2’s routes below), the 21st century hasn’t been without a few mind-boggling accomplishments—one of which was Polish ski mountaineer Andrezej Bargiel’s audacious summit-to-glacier ski descent of K2.

The mountain doesn’t exactly lend itself to good skiing; the continuous 50+ degree slopes are frequently interspersed with cliff bands, seracs, routine rock and icefall, and avalanche-prone gullies, and there’s no straightforward skiable line. Still, large sections of the mountain had been skied; in 2014, Luis Stitzinger, who passed away on Kanchenjunga in 2023, skied from Camp 4 to the mountain’s base via the Kukuczka-Piotrowski, also sometimes called the Polish Route, though he had to remove his skies to downclimb a 200-meter section of rock.

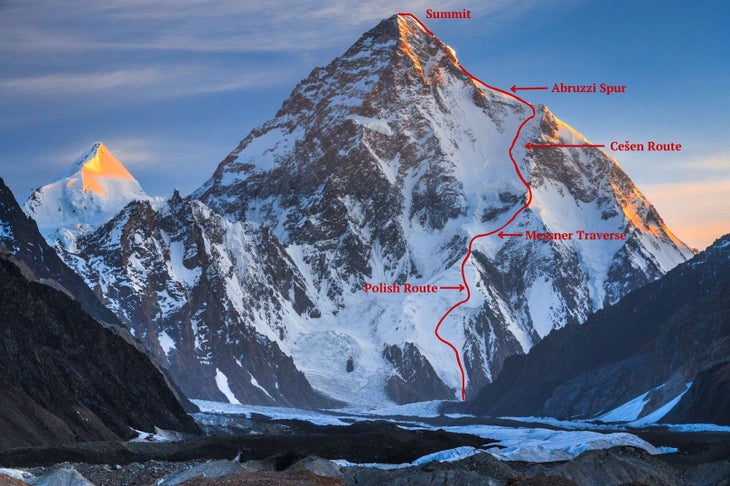

But after clicking into his skis on K2’s windy summit, Bargiel did not remove them. He descended the Abruzzi Spur through the Bottleneck (a section first skied by Dave Watson in 2009) before veering onto the South-Southeast Spur (Cešen Route) and negotiating the insanely exposed Messner Traverse (using a rope as protection for 10 especially heinous meters), which allowed him to access the Polish Route. From there, he skied a steep, crevasse-ridden glacier down to basecamp. He climbed and skied without supplemental oxygen. The AAJ has an excellent editorial about it.

Related: When A Climber Dies on K2, Is Anyone to Blame?

K2’s Climbing Routes

While nine of the 14 other 8,000-meter peaks (including Everest) are located in the Himalaya, K2 is located in Pakistan’s Karakoram Range, on the border of the Pakistani-Kashmir region Gilgit-Baltistan and a section of Kashmir administered by China as part of Xinjiang autonomous region. Climbers, therefore, deal with wildly different permitting systems depending on whether they climb the mountain from China or Pakistan.

Though K2 has more than a dozen routes (some of which overlap each other), the overwhelming majority of its ascents—and nearly all its recent ones—have come from via the Abruzzi Spur, which is considered its safest. We have listed only a selection of the routes and variations below. The East Face of K2 has never seen an ascent, in part due to the instability of its ice and snow formations. Neither has the direct North Face.

Abruzzi Spur

By far the most popular route on K2 is the Abruzzi Spur, also called the Southeast Ridge, which begins on the Pakistani side of the mountain. It was first attempted by the 1909 Italian expedition and was used for the peak’s first ascent in 1954. More than 75 percent of all successful K2 ascents are made via this route, which follows a ridgeline beginning at around 17,700 feet. It presents several technical and exposed sections, including the 100-foot crack House’s Chimney named for American climber Bill House, who successfully led it in 1938, and the Black Pyramid, a large arete protruding from the main spur. Another well-known feature is the Bottleneck, a steep couloir approximately 1,300 feet below the summit, which is overhung by a number of unstable seracs. Even though it’s considered the easiest of the routes, the mountain’s consistent steepness and formidable winds make it the hardest “trade route” on the 8,000-meter circuit.

The Cešen

K2’s second-most-popular route is the Cešen—also called the Basque Route and the South-Southeast Spur—which runs just west of the Abruzzi Spur and connects with it at the Shoulder (7,700 meters) roughly 60 percent of the way up the mountain, after which climbers follow the Abruzzi through the Bottleneck to the summit. The route was pioneered by Slovenian climber Tomo Česen, who soloed the line in 1984, though there is some controversy about whether he actually summited. Because the Česen avoids some of the technical obstacles like House’s Chimney and the Black Pyramid lower down on the Abruzzi, it is sometimes considered safer, but the line is significantly steeper and has rockfall and avalanche risks of its own.

Polish Route

When Reinhold Messner dismisses a route as “suicidal,” you know it’s rough stuff, and that’s exactly what he said of K2’s South Face before Jerzy Kukuczka and Tadeusz Piotrowski climbed it in 1986. The Polish Route, also sometimes called the Kukuczka-Piotrowski, begins in Pakistan, on the Southwest Pillar, before deviating rightward and launching up the center of K2’s extremely exposed and avalanche-prone South Face, joining the Abruzzi Spur just 1,000 feet below the summit. In a 1986 American Alpine Journal article, Kukuczka describes how, after making the first ascent, he and Piotrowski descended via the Abruzzi Spur over several grueling days; dehydrated, exhausted, and hypoxic, they fatefully forgot their rope at one of their bivouacs, which meant that when Piotrowski somehow dislodged both his crampons, he fell to his death. The Polish Route is so prone to avalanches and collapsing seracs, it has not received a second ascent—though Andrzej Bargiel did utilize large sections of it during his 2018 ski descent.

The Magic Line

Widely considered one of K2’s hardest and most aesthetically impressive routes, the Magic Line (as Reinhold Messner dubbed the South-Southwest Pillar) was briefly attempted in 1979 by an international team that included Messner and the great Italian soloist Renatto Casarotto; but the team had limited time on the mountain, and when it became clear how technically demanding the route was going to be, Messner insisted that they shift to the better-known Abruzzi Spur, which they used to make the mountain’s fourth ascent.

Casarotto returned in 1986, an astonishingly busy year on K2, and attempted the Magic Line alongside an American team, an Italian team, and a Polish-Slovakian team. The Americans and Italians did some crucial rope fixing lower on the route but decided to walk away after two of the American climbers, John Smolich and Alan Pennington, were killed when a boulder fell from the ridge above them and caused a large avalanche. Cassarotto then made three attempts on the mountain, reaching 8,300 meters before being turned around by bad weather; on his descent, just an hour above base camp, he fell 40 meters into a crevasse. After managing to reach his wife at basecamp by radio, he was rescued, but he died of his injuries shortly afterward.

Two weeks later, a Polish-Slovakian team composed of Wojciech Wroz, Przemyslaw Piasecki, and Petr Bozic made Magic Line’s first ascent. While rappelling through the Bottleneck on the Abruzzi Spur, Wroz, who was descending last, made a still-unidentified error and fell to his death. His teammates dedicated their climb to the four climbers who died in 1986 trying to accomplish it. Thirteen climbers died on K2 that year.

Since then, Magic Line has seen just one other ascent, by Spanish climber Jordi Corominas, who summited alone in 2006 after his teammates turned back. Climbing’s editor at the time, Dougald MacDonald, called it, “The most impressive ascent of a remarkable season.”

The West Ridge

The West Ridge (also sometimes called the Southwest Ridge) was first attempted by a British team led by Chris Bonnington in 1976, but they turned around after one of the climbers, Nick Estcourt, was killed in an avalanche. It was first climbed to the summit by a Japanese team in 1981, using supplemental oxygen. Remarkably, Japanese climber Matsushi Yamashita halted his effort just 150 meters below the summit, worried that his slower pace would hinder his teammates’ chances. Thanks to him, Japan’s Eiho Chtani and Pakistan’s Nazir Sabir reached the summit, after which all three returned safely to basecamp.

Watch Ian Welsted and Graham Zimmerman approach the West Ridge in 2021. Footage courtesy of Ian Welsted:

Since then, the West Ridge has been climbed just two more times. The line is still awaiting a pure alpine-style ascent, despite a 2021 effort by Piolet d’Or-winning alpinists Graham Zimmerman and Ian Welsted, who abandoned their effort after astonishingly warm temperatures made the climb too dangerous. “I knew that the climate crisis was affecting these mountains,” Zimmerman said afterwards, “but I can’t say that I anticipated getting scorched off the second highest peak on the planet.”

The West Face

When it was first climbed in fixed-rope siege-style (but without supplemental oxygen) by a large Russian team in 2007, the West Face was the first completely independent first ascent on K2 since 1986. The Russians’ direct line up the imposing 8,500-foot tall wall involves serious rock climbing, drytooling, and snow-climbing at high elevation. The route’s first crux is a 3,000-foot cliff called the Bastion, which ends above 25,000 feet. After that, typical K2 rigors—snowy couloirs, steep ice, and relentless wind—keep the difficulty consistent. Members of the Russian expedition likened the wall to what they’d found during previous expeditions to the North Face of Jannu and the Direct North Face of Everest, both in 2004. Eleven Russians summited during the expedition, a testament to the effectiveness of their controversial rope-fixing tactics. Lindsay Griffin, writing for Alpinist, described the West Ridge as “almost certainly the hardest route on the mountain.” It is unrepeated. Two of Japan’s strongest alpinists, Kazuya Hiraide and Kenro Nakajima, attempted the West Face in alpine style in the summer of 2024 but were killed by a fall.

Northwest Ridge

First climbed by France’s Pierre Beghin and Christophe Profit in 1991, the Northwest Ridge route begins on the Northwest Ridge proper before angling across the Northwest Face and joining with the North Ridge (first climbed by the Japanese in 1982) where they intersect at 7,800 meters. Writing about the unsuccessful 1995 American Expedition, John Culberson noted that, “The Northwest Ridge is a very long route, but offers some very good climbing, safe camps, and is free from the crowds.” His team was stormed off the upper mountain during their summit attempt. Interestingly, they also had a problem with ravens stealing their food caches from their higher camps: “Apparently there was so much snow in the valley,” he wrote, “that the birds were forced to forage on the upper wind-blown slopes.” Hearty birds. The Northwest Ridge remains unrepeated.

Northwest Face

First climbed by a Japanese team in 1990, the Northwest Face begins at the K2 Glacier and climbs the Northwest Ridge (see above) before deviating onto the Northwest Face and following rock and snow terrain until it intersects with the North Ridge route (see below) at 7,700 meters. The summiting climbers were Hideji Nazuka and Hirotaka Imamura. Their route is unrepeated.

The North Ridge

Described by legendary alpinist Steve Swenson as “one of the most striking lines on the mountain,” the North Ridge of K2 (also occasionally called the North Pillar) is a stunning rising arete that leads unbroken from the intensely remote North K2 Glacier to just below K2’s summit. It’s rarely climbed, in part because accessing it requires fording the hazardous Shaksgam River, and in part because the climbing is more challenging than it is on the Abruzzi.

The North Ridge was first climbed by a large Japanese team in 1982, and climbed again by an Italian the following year, but has seen just a handful of repeats over the decades—including an alpine-style ascent by Greg Child, Steve Swenson, and Greg Mortimer in 1990 (though they did make use of several hundred feet fixed ropes already in place on the mountain) and another alpine-style ascent by Kazakh superstars Serguey Samoilov and Denis Urubko in 2007. It was most recently climbed by Gerlinde Kaltenbrunner, who became the first woman to summit all 14 8,000-meter peaks without supplemental oxygen.

Northeast Ridge

The Northeast Ridge begins on the Chinese side of the mountain and charts a long and snowy course to its intersection with the Abruzzi Spur, just below the Bottleneck. It was first attempted in 1902 by Oscar Eckenstein and Aleister Crowley, who managed to climb to a height of 6,525 meters. Seventy-four years later, a Polish expedition managed to traverse the entire ridge, but they were forced to retreat from the higher mountain due to bad weather. The Northeast Ridge was finally climbed to the summit on September 6, 1978, by Americans Louis Reichardt and James Wickwire, who were followed the next day by John Roskelley and Rick Ridgeway. It was the fourth team ascent of the mountain and the first that did not use the Abruzzi Spur.

Is K2, the Savage Mountain, indeed getting less savage?

If you’re heading up the trade route, with the support of guides, the answer is an unequivocally “Yes.” But there’s plenty of adventure remaining on the peak. And even K2’s trade route is still a serious endeavor.

Basic facts and figures

- Elevation: 8,611 meters/28,251 feet

- Range: Karakorum, Kashmir, Pakistan/China

- First ascent: July 31, 1954.

- First ascensionist: Lino Lacedelli and Achille Compagnoni

- Cumulative successful summits: 800 (approximate)

- Cumulative deaths: 96

- Approximate death-to-summit ratio: 11:100

- Average cost to climb: $30,000

This article is part of Climbing’s online archives documenting climbing’s greatest mountains, such as Everest, and its pioneering practitioners such as Marc-Andre Leclerc.

The post Is K2, the “Savage Mountain,” Becoming Less Savage? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

The media giant’s removal of a key climber in “Jirishanca” sparked intense debate in the climbing-film industry.

The post How Real Should Reel Rock Be? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

I. The Coincidence

On July 23, 2022, a remarkable coincidence occurred on the snowy summit of Jirishanca, a notoriously difficult 6,125-meter mountain in Peru’s Cordillera Huayhuash.

It happened like this. After three continuous days on the mountain (plus one day beforehand spent freeing and then fixing rope on the first 10 pitches), American alpinist Josh Wharton kicked up a final pitch of 70-degree snow and became the first person to reach Jirishanca’s striking summit cone since 2003. Wharton whacked in a snow picket, chopped himself a seat, and began belaying up his partner, Vince Anderson. Meanwhile, a drone piloted by Cheyne Lempe and Drew Smith, videographers on assignment with Patagonia Films and Reel Rock, hovered overhead.

Yet when Anderson was still well below the summit, Wharton saw movement off to his right. Snow tumbling down the slope. An ice ax swinging for purchase. A moment later, Alik Berg, wearing an orange helmet and a blue parka with black shoulders, climbed into sight 10 meters away.

“Oh, hey, Alik!” Wharton said.

He knew Berg and his partner, Quentin Roberts, both Canadian, had started up Jirishanca on the same day as Anderson and Wharton—but what were the odds that a mountain that had seen three summits from the south in 65 years would get its fourth and fifth in the same 10-minute period by independent teams climbing hard independent lines? And mixed in with Wharton’s delight at the coincidence was relief: Whereas his route of ascent, Suerte Integral, was extremely high in technical difficulty yet relatively low in objective danger, Berg and Roberts’s route (for which they later won a Piolet d’Or, alpinism’s greatest formal honor) had quested off through wild-looking snow-mushroom terrain on the mountain’s previously unattempted southeast spur—a type of climbing that Wharton, who is famously understated, “would not describe as safe.”

“I was very excited that they survived their way up the thing,” he told me later. “I was psyched to see them—psyched that they were doing well.”

While Lempe and Smith watched on a screen in basecamp, Berg joined Wharton on the summit, dug himself a seat two feet away, and began belaying Roberts up.

A few minutes later, Anderson, breathing heavily, joined Wharton and Berg. Anderson whooped a few times. He and Wharton recorded some short videos. Roberts, still out of sight, swam carefully toward them through steep, three-dimensional snow. The drone collected fabulous footage of this moment: Berg, Wharton, and Anderson huddling on the flank of a near-vertical snow cone under a stony sky. I used one of those images in a 2022 news story about Wharton and Anderson’s ascent. Another appeared in a feature essay by Roberts that was published in this magazine’s 2024 issue of Ascent.

Wharton and Anderson didn’t tarry long on the summit. It was late in the day, they were thousands of feet above their bivy gear, and nights above 6,000 meters in the Cordillera Huayhuash are dangerously cold. So they began their descent having spent no moment alone together on the summit.

But when Lempe and Smith’s footage appears in the climactic summit scene in Jirishanca, a climbing documentary directed and produced by longtime climbing-film legends Josh Lowell and Peter Mortimer that premiered in Reel Rock 18 and is now available on Patagonia’s YouTube channel, Berg is nowhere to be seen.

Neither is his rope. Neither are his footprints.

The coincidence had been edited out of the story.

II. Reel Rock’s Jirishanca

If story-driven climbing films exist on a spectrum, with uncut send footage and bulletproof pieces of documentary journalism on the one side and shamelessly synthetic or even falsified stories on the other, I think that Jirishanca exists somewhere in the aesthetically successful middle.

The core of the story is relatively simple and undeniably true: Two American alpine veterans, Josh Wharton and Vince Anderson, attempt Jirishanca… and succeed. The climb is meaningful to them on several levels. Both men are famously bold alpinists; Anderson won a Piolet d’Or with Steve House on an arguably suicidal 2005 ascent of Nanga Parbat’s Rupal Face; Wharton has for decades been one of America’s greatest all-arounders, pioneering cutting-edge alpine climbs in Patagonia and Pakistan, trad climbing 5.14, winning international ice climbing competitions, and nearly flashing Free Rider on El Cap. In attempting Jirishanca, both men are trying to remain true to these hard-driving pasts while simultaneously honoring the survival imperatives impressed upon them by fatherhood. In 2019, during Wharton’s third attempt of the mountain and Anderson’s first, they bailed a couple hundred meters below the summit, worried that pushing on through “bad sugary snow” late in the day might subject them to a dangerous unplanned bivy. Now, in 2022, they’re back to recreate that summit-push opportunity—and to do so without exposing themselves to too much risk.

The narrative problem faced by the filmmakers here is pretty obvious: they’ve got compelling characters, but their film has very little intrinsic tension. On the mountain, Wharton and Anderson do not push the risk envelope; instead, they leverage their combined 50-plus years of alpine experience to avoid subjecting themselves to any anguished indecision about whether or not to “risk it.” Sure the climbing is incredibly hard (their route, Suerte Integral, involves dirty sport climbing up to 5.13a, loose mixed climbing up to M7, and dramatic WI6 ice, plus the objective hazards and logistical complexities inherent to most big mountain objectives), but since Wharton and Anderson got so close to the summit three years earlier, they—and the viewer—know that the climb is well within their technical abilities.

To offset these tension-numbing facts, the filmmakers (who, to their credit, do not invent drama where none exists) chose to ornament the climbing story with little human subplots—engines that, like beautiful sentences in a literary novel, keep the viewer invested despite the relatively low-stakes plot.

One of these subplots unfolds in Wharton’s on-camera banter with Peter Mortimer, Reel Rock’s founder and director of dozens of seminal feature-length climbing films, including Alone on the Wall, Return to Sender, and The Alpinist. In those scenes, which are interspersed throughout the film, Wharton explains why he has “dissed on” (Mortimer’s words) Reel Rock in the past for its tendency towards hyperbolic and sensationalized storytelling. “Hyperbole in climbing film and climbing media,” Wharton says, “puts people on pedestals in ways that really aren’t real.”

By including these exchanges, Reel Rock’s editors set up a clever change-over-time story for Wharton’s character: If, as legendary alpinist Steve House tells us early in the film, “You’re never going to get an ounce of hyperbole out of Josh Wharton,” and if Josh Wharton himself explains that his anti-hyperbole stance is a well-considered philosophical position rather than some basic schoolboy shyness, then if Wharton ever admits that his ascent of Jirishanca is meaningful or impressive, it will further underscore the climb’s significance to the viewer, and allow us to feel that Wharton has accomplished something he can feel proud of—which makes us happy.

And that’s how the film ends. While Wharton and Anderson celebrate on top of the world, we hear Pete Mortimer say, “Just to set the record straight. How badass is it?” And then we cut to Wharton, who looks only a little pained as he replies, “To be honest, for me it is super proud. …” As intended by Reel Rock’s experienced heartstring-tuggers, this ends up feeling somewhat moving.

But here’s the delightful irony: Wharton’s admission comes just seconds after we cut away from that spectacular—and highly edited—drone shot of two men alone on a mountaintop, looking singular, exceptional, spectacular… which feels a bit strange, a bit disingenuous, to any viewer aware of the fact that another man has been removed from their company, and that this missing man had arrived at that same destination via an inarguably more dangerous and committing route.

Which begs the question: Is Jirishanca, despite its subplot about hyperbole, a perfect example of problematic hyperbole in climbing film?

III. “We Can and Should Do Better”

On November 26, 2024, seven months after Reel Rock premiered in Boulder, Colorado, Alik Berg posted a pair of photos on Instagram: one of him on the summit of Jirishanca with Wharton and Anderson, and one of him edited out.

Berg then explained that he’d been reluctant to post these images “since the athletes and videographers we shared the mountain with are all friends… and to my knowledge had very limited input in the creative direction of the film. … Besides, we are talking about a few seconds of footage in an otherwise great film.”

But he added that, while he did not feel personally slighted by the edit, he did think this was a good moment to express his concern with “integrity in the climbing media world.”

“The online information landscape has become increasingly unreliable,” he wrote, “and I think that in the climbing community we can and should do better. The producers had some tough decisions to make in editing the otherwise spectacular summit shots, and I can respect that. To me, though, altering the footage to this degree seems disingenuous to the viewer, since the film is presented as a documentary. Besides, it was just a really cool part of the story!”

Berg’s post ignited what you might call a respectful hullabaloo in the comments section, where dozens of notable climbers, filmmakers, and articulate pundits discussed the role of truth in climbing media and the extent to which athletes and filmmakers ought to subordinate stories to facts or facts to stories. While it was an astonishingly civil dialogue compared to most discourse found on the modern internet, commenters were nonetheless largely critical of Reel Rock’s decision—and the wider climbing film industry as a whole.

American alpinist Colin Haley, for instance, argued that there was “a general problem in the climbing world… where ethics and integrity and accuracy seem not to matter if [you’re] making a movie. Tactics and behaviors that the community would judge poorly in normal circumstances are somehow accepted” when athletes are working with filmmakers. To make matters worse, “in most climbing films depicting ascents that I have personal knowledge of, I find many inaccuracies, often done intentionally in order to make the ascent seem more exceptional than it is.” He thus concludes that Reel Rock chose to omit Berg from the story because it “makes a more impressive movie.”

Meanwhile, Chris Kalous, the host of the Enormocast, honed in on storytelling—criticizing the media’s convenience-store relationship to facts (grab what you need, leave the rest behind) and simpler-is-better storytelling ethos, and arguing that Reel Rock’s summit omission is less some malevolent plot out to scrub Berg and Roberts from history than it is sheer artistic “laziness and wanting to deliver the same old story because brands don’t need/want complicat[ion].”

But another commenter, Colum Kelly, replied to Kalous pointing out that Reel Rock’s decision to edit Berg out of the shot was not an “omission”; it was an alteration. “There are clear guidelines for ethical documentary film-making,” he wrote. “Not cutting dialogue mid-sentence to change its meaning, using footage out of context, using cuts/juxtaposition to falsely imply simultaneity or the perception of cause and effect, selective omission to change the narrative etc.” To Kelly, if Reel Rock had omitted Berg by refusing to use that particular summit shot, they’d have been in an ethical gray zone, something he might not agree with but could understand. However, “deciding to use the footage anyway but remove the climbers is a bit different. That’s not editorial anymore, that’s completely removing the guarantee that the audience is viewing real footage. … Altering images brings everything into question. Was anything else justifiably altered to look more badass? Were anchors edited out? Were cameramen edited out? … There’s no guarantee that any of it is real.”

However, this wouldn’t be the 2020s without some healthy cynicism. Guidebook author Vitaliy Musiyenko wrote that “including other climbers, especially those sponsored by a different clothing brand, is not in the interest of the brand that paid for the production of the movie (commercial). … These films aren’t created because the brand wants you to be stoked on climbing, they are created as a more genuine way to advertise gear. Adding more to the story would likely require… shots of other climbers who are wearing clothing from a different brand.”

But Josh Lowell, commenting on behalf of the Reel Rock team, was quick to note that this was not Reel Rock’s intention. The decision to remove Berg from the summit shot, he said, was purely a matter of storytelling. One of the film’s early edits did include the unaltered footage, but its viewers found it “very distracting to suddenly see another person on the summit, who was visible from some angles and not others.” Realizing that they had the option of either altering the shot or dropping “a lot of explanation at the very end of the movie when it’s too late for new info,” the Reel Rock team “made the decision to avoid showing Alik.”

“I can understand how some people might find that choice debatable or objectionable,” Lowell added. “But it wasn’t about making the climb seem more impressive. And it had absolutely nothing to do with protecting a sponsor’s interest.”

Missing from the conversation were both Anderson (who simply didn’t comment) and Wharton (who does not have Instagram). So I called Wharton up to ask him about the edit and Berg’s post.

“I actually generally agree that it was sort of lame that they were edited out,” he said, noting that he’d had a good conversation with Berg before the post went up. “But by the same token, I understand why Sender [Films/Reel Rock] and Josh Lowell decided to do that—just to keep things simple and easy at the end. We like simple, easy endings. I think that’s a pretty common thing in movies.”

Then Wharton laughed, and I sensed a bit of weary dismay in it.

“And also,” he added, “thinking of climbing films as straight documentaries is a little naive. They are not, and never have been.”

IV. A Brief History of Climbing Films

Climbing films can, historically, be roughly categorized according to two competing impulses: vibes on the one hand, stories on the other.

In the early days of climbing media—before smartphones, GoPros, Instagram, and YouTube—most core climbing films tended, like skiing or skateboarding movies, to follow the vibes impulse. They were flashy anthologies of more or less independent climbing feats set to music and flavored by edgy, for-the-camera antics. (Think of Ben Moon and Jerry Moffat racing their BMWs in The Real Thing, released in 1996, or Jason Kehl fondling his dolls in Dosage Volume 1, released in 2002). These films, distributed by VHS and DVD, were designed for a core climbing audience who profoundly identified with the vibey expressions of the climbing lifestyle and, in the days before Instagram and YouTube, were easily wowed by grainy glimpses of pro climbers doing cutting edge things. We didn’t demand that our films tell traditional stories: that was the province of magazines.

But in the late 1990s and early 2000s, a wave of filmmakers—including Lowell and Mortimer—began experimenting with another kind of narrative. Dosage Volume 1 contains two utterly classic Chris Sharma shorts—Unfinished Business and Realization—that use interviews, voiceovers, and confessions of frustration to tell the story of Sharma’s multi-season struggle to establish Biographie (5.15a), which was then called Realization.

When I started climbing in 2004, DVDs of Dosage 1 were still on sale at Eastern Mountain Sports, and all the young sport climbers I knew not only owned a copy but watched it constantly. We were obsessed by the humanness of Sharma’s journey—the way he moves from overconfidence (Sharma had never not sent a climb he’d invested in) through failure and doubt (Unfinished Business ends with him leaving Céüse empty handed) to historic triumph (Realization was the first climb that everyone in the climbing world seemed to agree was 5.15). And we went out of our way to replicate that same arc in our climbing lives, idealizing the emotionally intense multi-year project as the main point of our sport.

I’m not sure if Reel Rock’s filmmakers explicitly saw Realization as a formula to follow forever after, but I suspect that they did realize that, by telling human stories with relatable characters, they could essentially make any viewer, regardless of how closely they already identified with climbing culture, care about the film. And so, over the course of the aughts, we began to see more and more films emphasize a relatively simple story structure: Introduce the viewer to a hero who has an emotional investment in a certain climb (the higher the stakes, the better) and then show them struggle with it—trusting the fact that the viewer will lend their own emotions to the climber’s success.

Yet sometimes these stories have felt forced and cheesy; we sense that we’re being told a thing because the filmmakers hope it’ll help us invest in the story’s outcome, not because the characters (real people, after all) actually think of their lives in such a way. I’d put Jonathan Griffin’s The Soloist VR, a virtual reality film about Alex Honnold soloing in the Dolomites and the French Alps, into this category. Despite excellent cinematography and insane climbing feats, it’s kind of a bad film, a boring film, a film with unconvincing dialogue (the characters are literally acting) and overly familiar narratives.

But while The Soloist VR is just boring, there are some instances in which I’d actually consider bad storytelling immoral. For example, in an intensely manipulative few seconds of “Will Power”—episode nine of Jimmy Chin’s NatGeo series The Edge of the Unknown—the filmmakers put an extreme amount of effort into making the viewer believe that it’s dangerous for Will Gadd to take a perfectly safe fall onto a bolt. Why? Because they want to keep the audience from changing channels during an ensuing commercial break. Of course, the film, though made by climbers, isn’t for a primarily climbing audience—but I don’t think that’s a good excuse to lie. Indeed, I think that makes it even more problematic. Because in so blatantly prioritizing storytelling over truth, ad slots over authenticity, Chin is essentially passing off a fictional danger as non-fictional one—which simultaneously gives non-climbers an inaccurate vision of our sport and threatens to undermine the authenticity of the real near-death experience that Gadd relates later in the same episode.

In that case, the “story” is being propelled by a lie, which undermines its own authenticity.

V. Can Some Lies Tell the Truth?

So, yeah, omission can clearly be problematic—but it isn’t always. Indeed, as Kalous implied in his comment on Berg’s post, making films—like making any story (including this essay)—involves accreting disparate details into a cohesive this-then-that order while leaving ancillary and unnecessary details out.

And we do want some stuff omitted.

We’re fine not watching Wharton (who had some tummy troubles on Jirishanca) pause his ascent to do his business. And we’re fine having 99% of the climbing omitted and instead letting a few impressive minutes give us an impressionistic understanding of an ascent that, in reality, took three full days. What we want is to feel like we’re being told a truthful story without feeling like we’ve wasted our time. And if the filmmakers deem “the story” too broad—too bulky for our attention or their time slot—they might choose to tell a part of that story rather than the whole thing.

Which brings us to a foundational (if somewhat counterintuitive) fact of documentary filmmaking: Simply shooting an event and publishing it unedited might actually tell us less about that event than a highly edited representational film, which shows very little of that event itself but gives us the information necessary to contextualize the story and its meaning. Uncut send footage of a boulder problem might, for instance, serve as proof that the ascent actually happened, but the footage doesn’t tell the viewer much about the climb, the climber, what that climb meant to them, and what their process on it was like. We don’t get a sense of the holds or the hours of failure that enabled the successful ascent. We might hear a yell of triumph, but we don’t have the data to interpret that triumph ourselves—to feel some simulacrum of what the climber might be feeling. That’s why many climber-filmmakers take the time to make edits of their sends, splicing in failed efforts, interviews, music that captures a certain mood, time lapses that capture the commute or the serenity of the climbing area. They want to help their viewer form a particular understanding of the climber, the climb, and their relationship to each other.

Jirishanca is simply a high-budget, big-picture version of this. Anderson and Wharton spent three days on the wall, plus months preparing for the trip, but instead of giving us “977 hours of uncut mountaineering footy” (as Chris Schulte, one of Instagram’s more insightful climbing trolls, facetiously requested), the filmmakers compressed that large story into 31 tightly edited minutes, most of which is character backstory, not actual climbing footage.

In their quest to give us these emotionally powerful representational films, filmmakers often rely on fabrication. For instance, that close-up shot of Chris Sharma’s fingers nestling into a tiny hold while sending some heinous, historic climb almost definitely wasn’t captured while Sharma was sending. (Capturing that moment in real time would require the filmmakers to have a shooter dedicated to getting that single shot during a send attempt.) Instead, it was captured before or after the send and then spliced into the relevant place during the send attempt in order to give the viewer a deeper and more realistic understanding of what that attempt actually entails. It’s a fabrication—but it’s in the service of a truth.

This “in service of truth” idea more or less governs every aspect of commercial film editing. Take sound design. When I spoke to Jonathan Griffin about The Soloist VR, he noted that birdsong, wind, breath, the rustle of fingers nestling into a hold, the clinking of gear—all of this was tinkered with, added in, removed, in order to give the viewer the puckering experience of being there on the wall beside a ropeless Honnold. Griffin even spliced heartbeats into crux sections—something that, of course, only Honnold himself would be able to hear—in order to trick the viewer’s nervous system into putting themselves in Honnold’s place. It’s a documentary in the sense that Honnold did actually free solo the climbs that he’s shown free soloing. But the film is attempting to convey an experience, not document that experience journalistically.

Even straight up altering footage is similarly commonplace in commercial climbing films. When I spoke to Reel Rock’s Nick Rosen about the Jirishanca edit, he told me that if Adam Ondra decides to send some magnificent 5.15 with a cameraman visible in one of the shots or a gumby (like me) falling on a 5.12d in the background, it’s more or less standard practice in commercial films and photo shoots to edit that person out. Sure, it’s a manipulation, he said, but that hangdogger/cameraman is not impacting the action, and removing them changes none of the facts; it just allows the viewer to focus on the facts that we have come to this movie to see. (This, of course, was one of Rosen’s main arguments in defense of cutting the footage: Berg and Roberts had done a different route on a mountain that had already seen plenty of summits. Their climb was a story—and a story that was worth telling—but it was a different story than the one that Reel Rock was telling, and introducing them into Anderson and Wharton’s tale amounted to an unnecessary distraction.)

But there are climbing films where omission, even if it does not involve alteration, is clearly problematic—and not just because (as with the Edge of the Unknown example above) it’s tricking non-climbers into believing something inaccurate about our sport. Sometimes, omission in film can lead to some climbers seeming to get credit for things that other people did first.

An excellent example of this, as Colin Haley notes in one of his Instagram comments, occurs in Renan Ozturk’s lamentable new NatGeo film, The Devil’s Climb, which follows Alex Honnold and Tommy Caldwell’s bicycle journey to Alaska and subsequent ascent of The Diablo Traverse on the Devil’s Thumb. In addition to being a straight-up meh movie (the “plot” is about as artificial as it gets; and Honnold and Caldwell more often deliver information by reading scripts than divulging information in candid interviews; and the whole endeavor feels utterly synthetic and unnecessary), The Devil’s Climb carefully avoids mentioning a very important contextual truth: That Honnold and Caldwell did not forge off into the unknown and conduct some magnificent first ascent when they linked all the towers in the Devil’s Thumb massif; instead, they were repeating a route that was established in 2010 by Colin Haley and Mikey Shaefer after being extensively scouted by Jon Walsh and Andre Ike in 2004. The only new thing was that they did it in a single day—and though they never overtly claim to be doing the traverse first, the film is carefully edited to imply that they are. Indeed, you could watch The Devil’s Climb and believe that no one had ever summited the Devil’s Thumb before—that the mountain, not its still-unclimbed Northwest Face, is what Honnold and Caldwell are referring to when they bandy around bogus phrases like “the last great problem in North America.”

You could argue—as its producers no doubt will—that this was an innocent case of sensationalization. The omission wasn’t designed to slight anyone. It was intended to simplify the story for the non-climber viewer and corroborate the film’s emotional narrative, which is that Caldwell, after a slew of injuries, still has what it takes to do badass things. But that, of course, makes The Devil’s Climb a perfect example of what Wharton is talking about in his interviews in Jirishanca: it’s hyperbole. And that hyperbole, in addition to simply making things feel stupid and fake, also puts Honnold and Caldwell (both of them legends I very much admire) on yet another pedestal that no other climbing duo is capable of reaching. Which is inaccurate. It’s lying by omission and implication. It’s actively appropriating the accomplishments of the climbers that stood on that pedestal before them.

So is Reel Rock doing the same thing in Jirishanca? Are they lying by omitting Alik Berg?

In the strictest sense, yes. Reel Rock shows Wharton and Anderson alone on that astonishing summit, two men having arrived in a location that no others are capable of reaching… except Alik Berg was there, too.

But in other ways, I think you could argue that Reel Rock’s edit is far less problematic than the divisively hyperbolic storytelling ethos on display in The Devil’s Climb, because—and this is crucial—Wharton and Anderson did a very different thing than Berg and Roberts. Neither team’s accomplishment is at all altered by any celebration of the other team’s. Reel Rock’s decision to edit Berg out of a film about Suerte Integral does not give Anderson and Wharton credit for establishing Reino Hongo. Editing them out of the shot is, at its core, more like editing out a hangdogger on an adjacent route.

But here’s a question: If, as Lowell says, Reel Rock’s edit had nothing to do with sponsor interests; and if, as I argued above, Reel Rock wasn’t being overtly appropriative when omitting Reino Hongo from a story about Suerte Integral; and if (though this is still debatable), we decide that climbing filmmakers are ethically permitted to edit ancillary or distracting details out of films so long as those details did not alter the events portrayed in the film—if all of that is true, is there still an argument that Reel Rock’s decision not to include Berg was nonetheless lazy? Should Reel Rock’s producers have taken a solid look at what happened and decided to tell a different story than the one they’d gone to the mountain to tell?

VI. What None of Us Are Thinking About

Before starting this essay, I sketched out a scenario that, I thought, might have allowed Reel Rock to keep Berg in the shot while increasing the film’s stakes and without interrupting the flow of the narrative. Here’s what I wrote:

They could have introduced Berg and Roberts early in the film (perhaps playing hacky sack at basecamp or packing up their gear) and then had Wharton, in a 10-second interview or voiceover, note (a) how special and unusual it was to be at Jirishanca’s southeast basecamp with another party, since the mountain is so rarely climbed, and (b) how he, a dad, was a bit nervous seeing these young guns heading up a line that clearly had a high level of objective risk. He could even explain how he’d given Berg and Roberts a ton of beta about the descent, since, if they made the summit, they intended to descend via Suerte Integral.

None of that, surely, would have severely disrupted the plot. Indeed, it would have added some tension. “What about Berg and Roberts?” we’d be wondering while Anderson dodged falling ice and Wharton climbed over fabulous ice roofs. And then, when Wharton is on the summit, we could get a drone shot of Berg appearing around the corner, which would augment rather than confuse the emotional climax of the film: Not only did our veterans achieve their dreams—the young guns lived! And everyone summited at the same time! What a happy ending!

But when I summarized this for Rosen and asked why his team didn’t take such an approach, he reminded me that film is not like writing. “I’m not sure there would have been a way to do that,” he said, “given the footage we had.”

He explained that no member of Reel Rock’s core management team was present in Peru for the shoot, so they weren’t even aware that Roberts and Berg were on the mountain until they saw the drone’s summit shot after everyone was back in town. So they quite simply did not have the footage they’d have needed to work the young climbers into the film. (“Maybe there is one shot of them, like, hiking up or something,” he said, “but I don’t remember seeing it.”) Working them into the film, he said, would therefore have involved either collecting footage retrospectively, which was not really an option on a mountain so remote as Jirishanca, or using still images with voiceovers.

“There was no natural way of back-filling them in the story,” he said. “So if we had been forced to change it, I think we would have just had this kind of awkward moment in the end. … I can picture it: You would just stop the action right there at the top, when all the emotion is crescendoing, and this partnership between these two guys has reached its apotheosis—you’d bring the story to a screeching halt and explain why they’re not on the summit alone.”

What about simply cutting their losses and not using the summit shot—omitting Berg rather than editing him out and instead relying on GoPro summit footage shot by Wharton and Anderson?

He replied that they could have—but it would have been hard since they didn’t have much alternate footage. Originally, a camera operator—Drew Smith—was supposed to climb Jirishanca with Anderson and Wharton, capturing film on the wall. But Smith got sick just before their attempt, which meant that the only on-the-wall footage they had was captured by Wharton and Anderson with their GoPros. “If we actually had someone up on the wall as we planned to,” said Rosen, “maybe we could have sacrificed that [summit] shot. ”

Still, Rosen, like everyone, acknowledged that editing Berg out was a grey area: “Not every filmmaker would have handled it in the same way. But I think I stand by our decision because, for the sake of the veracity of that one shot, we would have made the film a lot worse. And we have a commitment to our audience and to the quality of our films. We have to have an overwhelming reason to mess with the quality of the story we’re telling. And we felt like it would have made virtually no sense to the audience to reveal [Berg] at the end or try to backfill some story about the other team. The story just wasn’t about that. Storytelling, both written and documentary, is a process of omission. Essentially, you’re following a thread, but you’re also trying to cast aside unnecessary details. If people want the comprehensive history, they should read the American Alpine Journal.”

Hearing all this, I still can’t help but feel that Rosen is wrong—probably because part of me stubbornly believes that my sketch above could (somehow!) have worked. But another part of me recognizes that—as Berg himself pointed out—we’re talking about a four-second edit in an otherwise great film. A film that I legitimately enjoyed. So maybe there is no right or wrong here. And perhaps, as Rosen suggests, it’s time to subscribe to the American Alpine Journal.

The post How Real Should Reel Rock Be? appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Bailey has now climbed both V17 and 5.15c—making him one of the most accomplished outdoor climbers of all time.

The post Watch Sean Bailey Send ‘Shaolin’—America’s Newest Proposed V17 appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

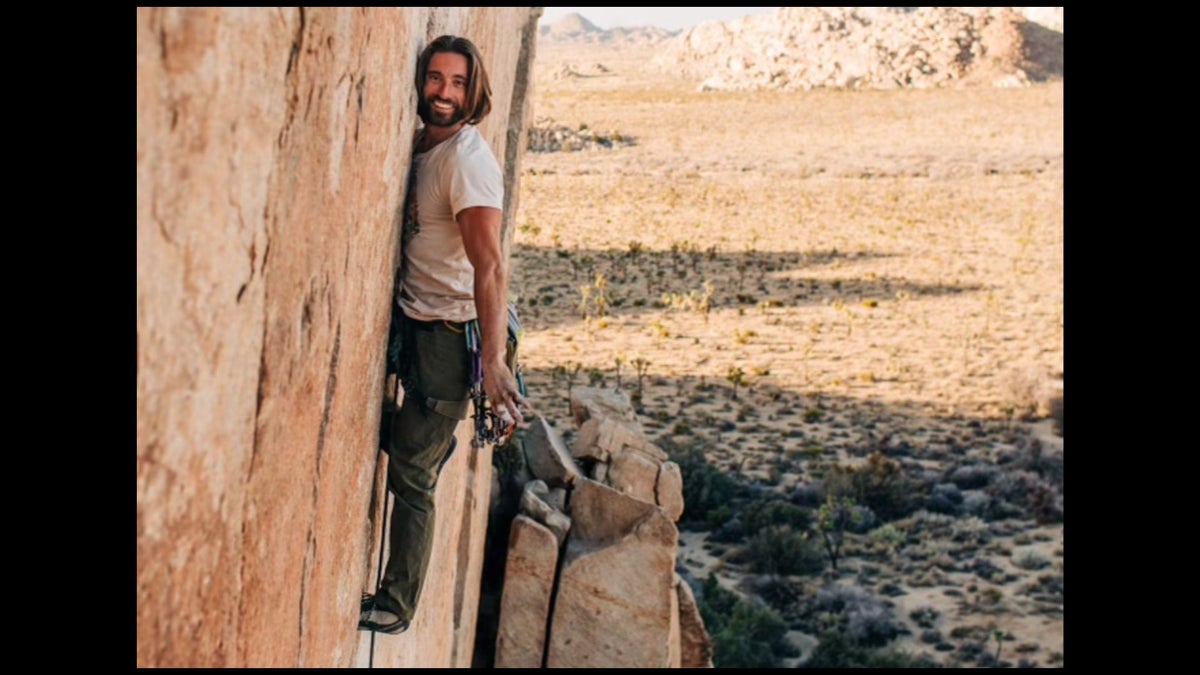

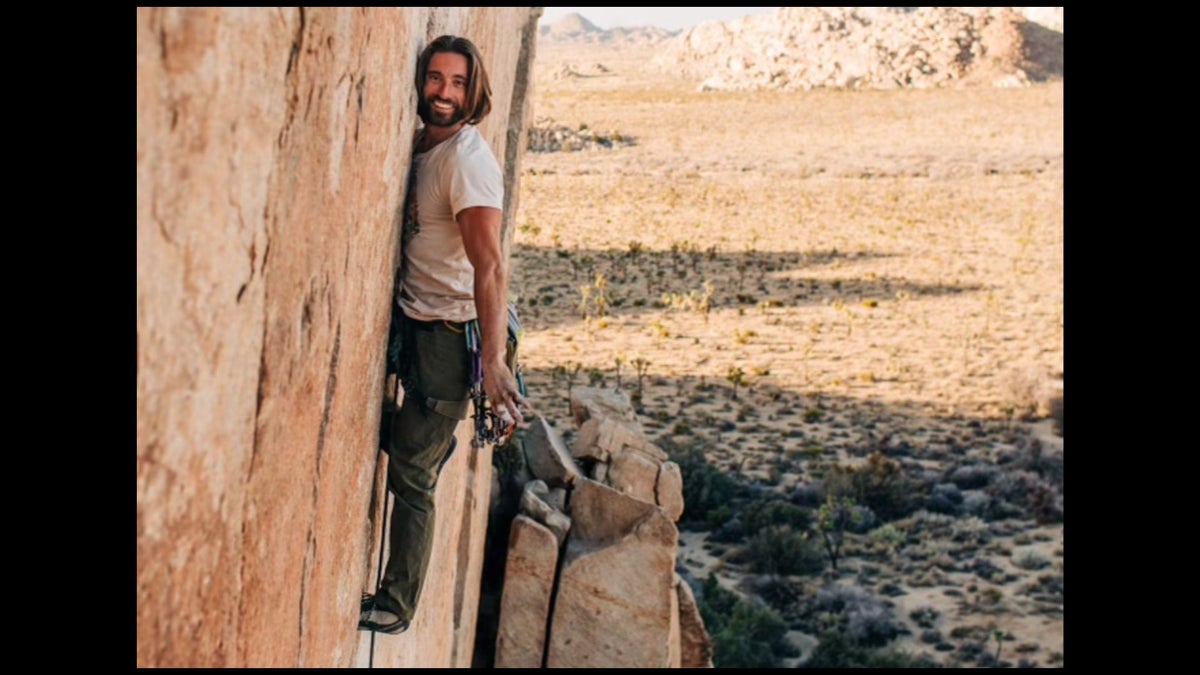

Mellow has released a video of Sean Bailey making the first ascent of his hardest problem to date, Shaolin in Red Rock, Nevada, for which he proposes V17.

Previously known as the Trieste Project (it sits on the same boulder as the popular V14 Trieste), Shaolin saw its first true salvo of efforts from Daniel Woods, Jimmy Webb, Drew Ruana, Shawn Raboutou, and Sean Bailey in the winter of 2020—when Daniel Woods was in the middle of his 80-day siege on the nearby Return of the Sleepwalker. The problem was later featured in a video called “The Hardest I’ve Ever Tried” on Shawn Raboutou’s YouTube channel.

The problem begins with a five-move V13 sequence directly into the crux move, which can be done statically (Raboutou’s method, which took him five days to stick in isolation) or as a “low percentage and physical” jump (Bailey’s method) to a sloping slot. This leads to a heartbreakingly hard-to-stick jump to a sloper, where Bailey fell multiple times from the ground.

After narrowly failing to secure a ticket to the Paris Olympics last fall, Bailey, who was already the only American to climb both V16 and 5.15c (Bibliographie), turned his attention back to the rocks. For the past 12 months, he’s been on a tear, flashing Slasher (V13) in Joe’s Valley, doing the first ascent of Doors of Perception (V15), repeating Lucid Dreaming (subtly proposing a re-upgrade to V16), making the first ascent of Devilution (V16), repeating Eye in the Sky (V15) in Switzerland, and making promising links on Burden of Dreams (V17). Now, he’s become the first American to climb both V17 and 5.15c.

5.15d, here he comes?

I’d put money on it.

The post Watch Sean Bailey Send ‘Shaolin’—America’s Newest Proposed V17 appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Whether you’re picking gifts for a gym rat, a diehard alpinist, or any climber in between, our holiday gift guide has you covered.

The post The Best Gifts for the Climber in Your Life appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Climbers are a notoriously picky bunch to shop for, so keep it simple this holiday season. The editors at Climbing have been testing non-stop in 2024, and we’ve highlighted the best new gear that your hard-earned money can buy. We’ve field tested everything on the list below—from cushy socks and comfortable hardshells to innovative belay devices and ropes—and can confidently say these will earn the appreciation of the climber in your life.

Best Gifts Under $75

Camp Nano 22 Rack Pack ($40)

The Nano 22 is billed as the lightest “fully functional” carabiner in the world, and we wholeheartedly agree. There are certainly lighter carabiners out there—but they are typically much smaller and therefore a nightmare to handle when pumped or while wearing gloves. The Nano 22, meanwhile, has a surprisingly deep basket for its featherlight weight (22 grams), enabling us to clip them in a hurry when pumping out on long multi-pitches. These carabiners live on our alpine draws and cam slings when we’re shaving grams.

Arc’teryx Merino Wool Grotto Mid Sock ($30)

All but the least-kempt climbers in your life wear socks and, unlike spoiled children, will be thrilled to receive a fresh set. The Merino Wool Grotto Mid is among our favorites from Arc’teryx: its soft and comfortable Merino wool is blended with nylon for added durability over years of use, and it’s lightly cushioned for long approaches. Whether you’re hiking to the crag, cold-weather rock climbing, or powering up an ice pillar, the Grotto Mid provides a snug, slip-free fit.

Gifts Under $150

Edelrid Pinch ($120 USD/$170 CAD at the link below)

Edelrid’s new assisted-braking belay device, the Pinch, made waves earlier this year with its ability to attach directly to the belay loop—no carabiner required. (To open the Pinch, you must press a small, tilting button while the device is simultaneously rotated 90 degrees from your body.) Climbing testers were initially skeptical of the Pinch’s ability to stay locked while belaying, but after four months of steady testing, we are now confidently catching airy whippers and belaying on big walls without the added weight or clutter of an extra locker. The Pinch feeds rope just as smoothly as other popular assisted-braking devices, and offers a smoother lower and rappel thanks to a beefy handle. An anti-panic feature—which locks the Pinch if lowering too quickly—can be disarmed if preferred.

Petzl Sirocco ($130)

The beloved Sirocco helmet is redesigned for 2024 and—somehow—is even better than before. Petzl has swapped its magnetic chin buckle for a plastic one (greater security), a bulbous forehead for a slimmed down silhouette (greater field of vision), and a better ventilation layout to encourage airflow while limiting the sand and dirt and ice that inevitably falls into big forehead vents while climbing adventurous terrain. Despite these extra features the Sirocco retains its 160-gram weight in S/M, making it our favorite ultralight helmet on the market.

Black Diamond Ultralight Ice Screw ($85-$90)

With instant bite, smooth boring, and easy-action handles, there is no need to run it out while climbing with BD’s Ultralight Ice Screws. The aggressive geometry on the steel teeth gives it a bulldog bite when placed on vertical ice, and the aluminum shaft—an ample 2cm in diameter—let us re-use most screw-holes on popular climbs that resembled Swiss cheese. Add in a snappy, fold-out plastic handle, and these things practically spin themselves in. BD has shaved 45 percent off the weight by pairing aluminum and steel—encouraging us to bring a couple more up that crux pitch.

Shop at blackdiamondequipment.com

Petzl Swift RL Headlamp ($140)

The Swift RL is a brilliant headlamp for those needing long-lasting support on their nocturnal adventures. Whether you’re sessioning crispy crimps by moonlight, accepting benightment on Epinephrine, or foregoing bivy gear in Patagonia, the Swift RL’s 1100 lumens and max burn time of 100 hours will surely outlast whatever sufferfest you’ve imposed on yourself. The rechargeable Swift RL is efficient in more ways than one: its 100 grams comes with a “Reactive Lighting” sensor that examines the ambient light and adjusts its brightness accordingly.

Gifts Under $300

Scarpa Arpia V ($169)

Designed for intermediate climbers, the Arpia V is both moderately downturned and asymmetrical, and gets especially high marks in both comfort and edging performance. It’s a supportive shoe, thanks to its full-length midsole and outsole, and should be attractive to heavier climbers who need stiff, supportive shoes while standing on small edges. That said, the Arpia V still has enough shape and toe-box sensitivity (thanks to the asymmetry and downturn) to let you curl into incut edges and feel small deviations underfoot. All in all, the Arpia V is an excellent shoe for intermediate climbers looking for something that will perform equally well on face climbs in the gym or outside.

Mammut 9.5mm Alpine Core Protect Rope ($290 in 60m)

Climbing-rope security has come a long way since the days of stiff hemp cords, and Mammut has taken their ropes to a new level with the Alpine Core Protect: a 9.5mm single rope that has a second sheathe woven with burly Aramid fibers. This rope handles and catches falls just as smoothly and softly as any of Mammut’s other 9.5mm ropes, but in the event of a dangerous fall over a sharp rock edge—as often found in mountainous environments—this Aramid-infused sheath will drastically increase its cut-resistance. We’ve spent five months beating the crap out of this rope—including on Minotaur Direct (5.11+; 500m) in the Bugaboos, Mt. MacDonald’s Northwest Ridge (5.8; 900m), and Buddha Nature Direct (WI 5; 120m)—and have noticed zero premature wear. The Alpine Core Protect also comes in 8.0mm half ropes, if wandery routes are your thing.

Patagonia M10 Storm Pants ($279)

The new M10 Storm Pants is this year’s best climbing-apparel innovation. Ice climbers, alpinists, and backcountry rock climbers who need the weather-proof security of hardshell pants have historically had to sacrifice a significant amount of comfort and mobility, since run-of-the-mill hardshell pants stem and lunge about as well as a pair of suit trousers. Such a sacrifice is no longer necessary thanks to the M10, which fuses the mobility-first design of jujitsu pants with various nerdy, alpine insights from Colin Haley, who has tested prototypes since 2019.

The M10 pants have a generously gusseted crotch—yes, you can do the splits in them—an elastic waistband and cuffs, a thigh pocket, a diagonal zipped fly, and little else. Coming it at just 240 grams in medium, the M10s are surely the lightest fully-waterproof pants we’ve ever worn, and have served us well while battling up ice pillars running with water and racing electrical storms in the rugged Purcell Mountains. Bonus: the M10 series also includes a full-zip jacket and an anorak. We’ve been digging the latter for its unrestricted arm mobility and low-key profile while tucked into a harness.

La Sportiva Mandala ($209)

La Sportiva’s No Edge technology is about as close to the term “divisive” as climbing technology gets: While the majority of climbing shoes have a defined, 90-degree intersection where the sole and rand meet in front of your toes, the shoes in the No Edge line have a rounded front, which La Sportiva achieved by wrapping the sole up around the toe so that it becomes toe-scumming patch on the top of the shoe. This design sacrifices some precision-edging performance, but it maximizes smedging—the ability to smear over edges and into divots—and allows you to extend on the tip of your toe like a ballerina.

With the new Mandala, the No Edge tech is paired with its most supportive shoe yet, making it an attractive choice for boulderers and sport climbers alike. Tester Matt Samet wore his extensively on a 15-degree overhanging 5.14 project in the Flatirons, while editor Anthony Walsh trusted them while onsighting 30-meter 5.11 and 5.12 limestone routes around Canmore. As Walsh put it: “I wouldn’t reach for these shoes for razor-thin edging (hello, Katana Lace!) or Font-style sloper problems (the Mantra!), but for everything else, they are in rotation. It’s what the La Sportiva Genius should have been.”

Gifts $300+

Coros Apex 2 Pro Watch ($449)

The Coros Apex 2 Pro is a GPS sports watch that gives mountain athletes of all kinds the ability to accurately track their training and performances. It features a touch screen made of sapphire glass and three low-profile buttons. It’s got all the bells and whistles, including geo-location data from five satellites systems, a topographic map, heart rate data, a barometric altimeter, a 3D compass, a thermometer, an oximeter, and music storage—plus specific activity tracking including the “Indoor Climbing” mode. The Coros Apex 2 Pro takes all the features we love from the Apex 2 and brings it to a new level with an increased battery life (now 21 days with stress monitoring, and 66 hours with full GPS tracking) and a slightly larger watch face. Climbers who struggle with either over- or under-doing it in the gym will benefit from the insight and accountability this watch can offer.

PAID ADVERTISEMENT BY MOUNTAIN EQUIPMENT

Mountain Equipment Oreus Jacket ($449.95)

Endorsed by leading alpinists, the Oreus jacket from Mountain Equipment delivers superior warmth, functionality, and durability in challenging environments. This versatile jacket is crafted with innovative Aetherm Precision Insulation for down-like performance with the durability and weather resistance of synthetic fill. Between warmth, quick-drying performance, low weight, and pack size, it’s perfect for alpine climbing, ski touring, hill-walking and more as an outer layer, warm mid-layer, or lightweight belay jacket.

Precision Insulation for down-like performance with the durability and weather resistance of synthetic fill. Between warmth, quick-drying performance, low weight, and pack size, it’s perfect for alpine climbing, ski touring, hill-walking and more as an outer layer, warm mid-layer, or lightweight belay jacket.

Black Diamond Hydra Ice Tool ($310)

Ice climbing tools have come so far since the medieval days of straight-shafted instruments that it can be difficult to wade through all the modern-day options. Most ice tools have a balanced swing weight, comfortable grip, and aggressively shaped shaft to minimize pump and bruised knuckles. So where does a would-be consumer go from there? We’d point them toward Black Diamond’s all-new Hydra, which is quickly becoming our favorite tool of all time.

One of our favorite things about the Hydra is how customizable you can make it depending on your objective. Its innovative head weights are the real headline here: Black Diamond sank the weights into the head itself, rather than bolting them onto the pick, simultaneously providing a more balanced swing weight and a lower profile. Thanks to this recessed head, ice climbers can opt for simple 5-gram “spacers” if they’re climbing warm, wet ice and don’t need the extra heft. Or, if swinging into bullet-hard ice in Canada, as we did on the north-facing Stanley Headwall last winter, drop in two 40-gram headweights to let the Hydras do the work. We’ve also been going hybrid—one light spacer, one heavy weight—to achieve that Goldilocks-swing at medium altitudes.

Head weights aside, the Hydra comes with a suit of tools that would make a mechanic jealous, including a long “Alpine” spike for snow plunging, a “Micro” spike, a full-size alpine hammer, micro hammer, adze, and handle spacers. And don’t get us started on their razor-sharp picks… Read our new field-tested review here.

Shop at blackdiamondequipment.com

The post The Best Gifts for the Climber in Your Life appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

'Dreamtime' was the world first proposed V15 boulder. In climbing it, Kiersch becomes the ninth woman to climb the grade.

The post Michaela Kiersch Sends ‘Dreamtime’—Becomes the First Woman to Send 5.15 and V15 appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Michaela Kiersch, 29, has made the first female ascent of Fred Nicole’s 2000 testpiece, Dreamtime, in Cresciano, Switzerland. This makes her the ninth woman to climb the V15 grade and the first woman to have climbed both 5.15 and V15.*

Kiersch is originally from Chicago. She started climbing in a classically dingy, spray-wall-style gym when she was 7 and spent a decade balancing comps with outdoor trips to the Red River Gorge. She placed fifth at the Youth World Championships in 2008 and competed intermittently on the adult circuit until 2018, when she stepped away to focus on outdoor climbing and school, ultimately earning a doctorate in occupational therapy. She now lives in Salt Lake City and works as an occupational therapist on a contract basis in between climbing trips.

And during those trips, she’s been almost disturbingly productive.

For instance: On a three-week trip to Magic Wood in 2022, she ticked 16 boulders V10 or harder—including Tigris Sit and New Baseline, both of which are V14. And during a six-week trip to Spain this past spring, she onsighted a 5.14a, redpointed a 5.14b and two 5.14c’s, and sent her second 5.15a, Victima Perfecta (5.15a). And this past summer, on a trip to Rocklands, South Africa, she sent 18 double digit boulders, including Fred Nicole’s crimp-classic Amandla (V14)—with a broken pinky finger.

Kiersch’s prodigious tick lists often pay dues to the sport’s history. While working on her doctorate, Kiersch took breaks from her studies to make the first female ascents of Super Tweak (America’s first 5.14b) and Necessary Evil (America’s second 5.14c), and the second female ascent of Dreamcatcher (Chris Sharma’s beautiful 5.14d in Squamish).

Kiersch says she chose Dreamtime for her first V15 in part because of its history. “Fred first established this boulder right when I started climbing,” she said. “Over the last 25 years, it has always stayed in my mind as the gold standard. I think it would make the top of anyone’s dream list.”

But she also added that Dreamtime was also, quite simply, the first V15 she’d put real effort into.

“I first tried Dreamtime in 2022 for one session on the stand start (V12),” she said. “I had just sent La Rambla and went to Ticino afterwards. I couldn’t hold any of the holds, and it felt nearly impossible.”

She had intended, she said, to invest some time and skin into a V15 this summer in Rocklands, “but with the broken finger and weather [2024 was an intensely wet Rocklands season] it became clear that it wouldn’t be in the cards.”

So she went home, trained, and then returned to Switzerland “stronger than ever.”

It’s been wet in Switzerland this fall, too, and once things dried out, she had to take a break from the boulders to compete in the Red Bull Dual Ascent—a multi-pitch plastic competition up Switzerland’s Verzasca Dam. But she managed to nonetheless send Dreamtime on her seventh day of effort this year.

The bonus? The rain seems to have let up.

“Now the fun can really begin!” she says.

What, specifically, is she about to have fun on? I asked.

“You’ll have to wait and see,” Kiersch said.

* I should note that speaking about “firsts” is complicated by the fact that grades are hard to determine. Ashima Shiraishi, for instance, has climbed two V15s (Horizon in Mount Hiei, Japan, and Sleepy Rave, in Grampians, Australia) and one 5.14d/5.15a (Ciudad de Dios, in Santa Linya, Spain). But while most ascensionists consider Ciudad de Dios hard for the grade, all 13 climbers 8a.nu and six climbers on The Crag have taken the lower grade.

The post Michaela Kiersch Sends ‘Dreamtime’—Becomes the First Woman to Send 5.15 and V15 appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Our tester found the Arpia—which is billed as a performance all-arounder for intermediate climbers—both comfortable and highly functional out of the box. But, at times, he yearned for a more specialized shoe.

The post Field Tested: Scarpa’s Arpia V Is a Comfortable Performance All-Arounder appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Our Thoughts

I spent much of last March and April testing an Ocun shoe called the Sigma, which was possibly the single best high-end, low-angle sport climbing shoe I’ve ever worn. (Yeah, I know, it surprised me, too.) Compared to gym shoes like La Sportiva’s Ondra Comp and Scarpa’s Veloce L, both of which I liked, the Sigmas were heavy, stiff, almost clunky, forcing your feet to conform to their fang-like shape and not the other way around. But I’ve never stood more comfortably on minuscule feet. So it was with a bit of sadness that—my Sigma review finished—I pulled Scarpa’s Arpia V out of the box, sighed at the old-school double velcro system, and started breaking them in.