A Climber We Lost: Richard “Dick” Shockley

Each January we post a farewell tribute to those members of our community lost in the year just past. Some of the people you may have heard of, some not. All are part of our community and contributed to climbing.

Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

You can read the full tribute to Climbers We Lost in 2023 here.

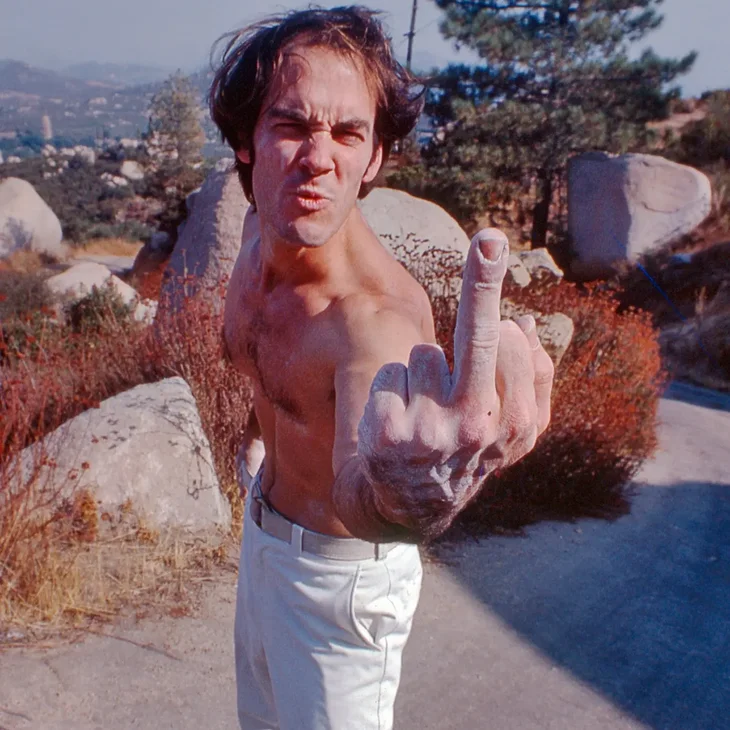

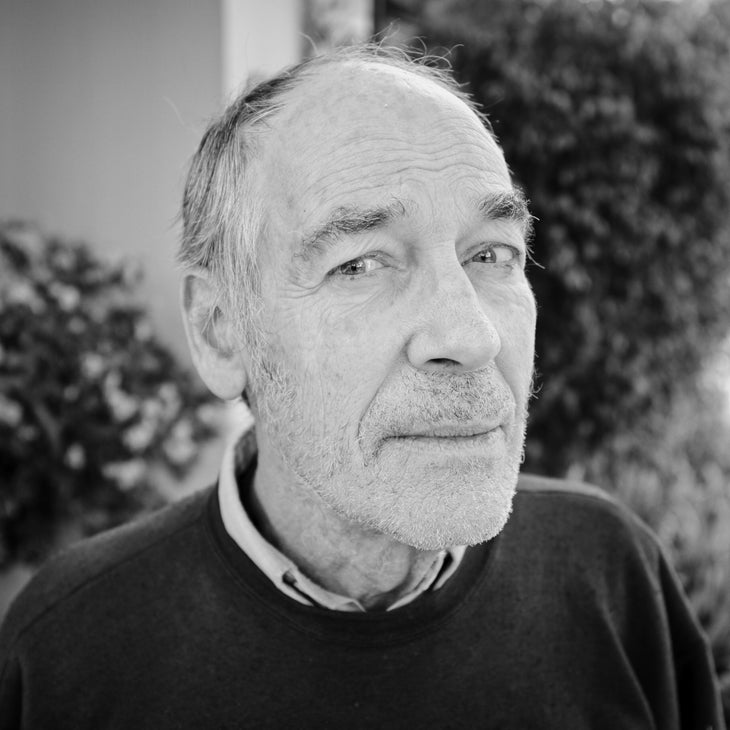

Dick Shockley, 75, February 19

Richard “Dick” Shockley was a scientist, poet, jokester, and one of the original Stonemasters. In the early 1970s, while doing a post-doc at Caltech, Dick was a fixture at Southern California hangs like Stoney Point, Tahquitz, and Suicide Rock, building friendships with Mari Gingery, Mike Lechlinsky, Rick Accomazzo, John Bachar, and Dean Fidelman. Later, while living in San Diego and studying the physics of underwater sound transmission as a civilian employee of the Navy’s Space and Naval Warfare Systems Command (SPAWAR), he frequented Mount Woodson and the Santee Boulders, while making sure to get up to Tuolumne in the summer.

“He was a regular at Tahquitz and Suicide [in the 70s],” remembers Lechlinsky, “always burning the candle at both ends, working during the week, climbing on the weekends. He did some early ascents of El Cap, back when people didn’t even have harnesses. He climbed The Salathe with Rick Accomazzo in May 1978.* He climbed Mt. Watkins with Maria Cranor.”

*Dick’s account of that experience, ‘Cruising Up the Salathe,’ appeared in Ascent in 1980 and describes, among other things, how he and Accomazzo witnessed one of the deadliest accidents in El Cap history, when an anchor failure sent three Minnesota climbers to their deaths.

“He climbed impeccably well,” says Dean Fidelman. “He wasn’t fluid, but he wasn’t jerky. He was very precise, especially on slab, and he soloed a bit, like most of us. But he was also something of a role model for me. When I met him in 1971 or 1972, I was this 16-year-old kid, and he was an adult, like ten years older than me. He had short hair and a job, but he was really hip. I mean, he smoked pot, and he drank, and he was a climber, and as an adult, he gave me some validation for being who I was.

“Shockley was so smart, so intelligent, but his childhood was pretty messed up,” says Fidelman. “I think he felt like an outcast his entire life, especially in his younger life, and when he met all of us, when he fell in with the Stonemaster scene, he started to experience belonging a bit more fully. And I think he understood that.”

Dick’s father, William Shockley, was a renowned scientist and rock climber who was awarded the 1956 Nobel Prize in Physics for his role in inventing the solid-state transistor and did multiple first ascents in the Shawangunks. Later, in Palo Alto, California, he did research on silicon semiconductor devices, and he’s still remembered as “the man who brought the silicon to Silicon Valley.”

But Dick’s father is also remembered for bigotry and racism. In the 1970s and 1980s, William Shockley (who had no formal training as a geneticist) undermined his scientific renown by advocating for intelligence-based eugenics programs, believing that higher reproduction rates among supposedly less intelligent demographic groups (groups which William Shockley explicitly defined along racial lines) would pollute the global gene pool and ultimately ruin civilization.

“Dick was not like that,” says Mari Gingery. “He didn’t have a good relationship with his dad. But it shadowed his whole life.”

As a parent, the older Shockley was an absent, brow-beating father, who separated from Dick’s mother (she raised Dick and his siblings, William and Alison, on her own) and was later quoted saying that his three children “represent a very significant regression” from his own intellectual heights. “My first wife [Dick’s mother] had not as high an academic-achievement standing as I had.”

“His father was very nasty and very harsh,” says Jackson Judge, one of Dick’s closest friends. “He used to torment Dick with math problems that he couldn’t solve, and Dick worked on these problems for years afterward. Even when he was totally estranged from his father, refusing to speak to him, Dick was still trying to figure them out, chasing that validation.” Yet even while Dick loathed his father, he in many ways followed his father’s footsteps, becoming not just a physicist (he published numerous peer-reviewed papers) and a climber (he once chucked a naked free solo lap on one of his father’s most classic routes, Shockley’s Ceiling [5.6] at the Gunks), but someone who pinned other people’s value on their intelligence. “He used to give riddles to people at the boulders,” Judge remembers, “and he valued the people who answered the riddles correctly. He valued ruthless intelligence.”

But he also valued humor. Among his friends, he became famous for his inventive one-liners, often known as Shockleyisms, like “no mistake or big pancake,” “make haste or tomato paste,” and “keep your head or hospital bed,” which he’d “fire off in the middle of other people’s leads,” remembers Gingery. He was similarly famous for a stunt that, when imitated by others, was simply called “pulling a Shockley”: “He would be cruising an easy route with big holds in an exposed or unprotected location,” says Mari Gingery, “and then he’d fake a fall, cutting his feet loose and scaring the bejesus out of onlookers. It was a real heart stopper. So of course his antics were copied by other climbing jokesters of the era.”

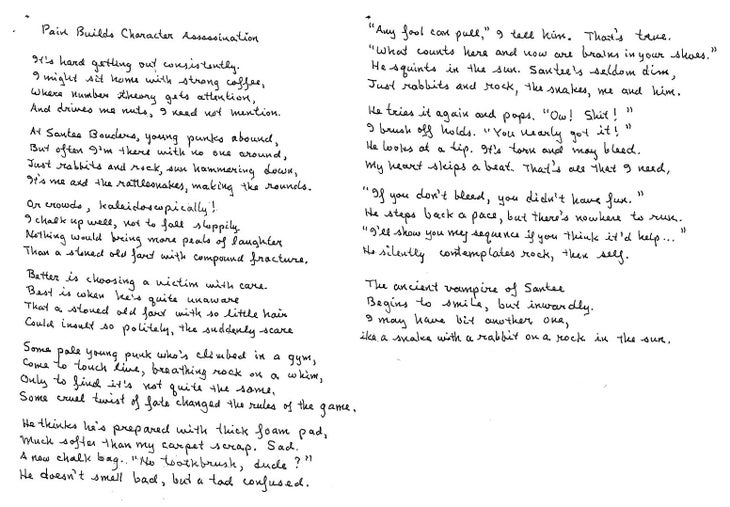

Off the wall, he was yet another big personality in a crew of them. “He could do some amazing athletic tricks,” Gingery says. “He could hold his foot in one hand and jump the other leg through it, which is incredibly difficult. And he played speed chess like crazy. He’d play anyone. He and Charles Cole [who later founded Five Ten] had matches. He and Bachar had matches. Shockley would sometimes play two boards—and two different people—at the same time. He also wrote poetry about climbing and science and philosophy, most of it hilarious, some of it incredibly long, and he had these poems committed to memory, so you’d be on a phone call with him, or out playing hacky sack, and suddenly he’d start reciting this ten minute poem. He was very smart and his memory was incredible.”*

*When he died, Dick left several hundred pages of poetry with Jackson Judge and his wife.

“He was always trying to teach ‘blind man physics’,” adds Lechlinsky, “trying to explain physics in ways that other people could understand.”

“He had deep conversations with Chongo about physics,” says Gingery. “He said Chongo’s physics didn’t hold up to the standards of science. But Dick gave him time to express his thoughts. He was that kind of guy. He was open to anything.”

One of the great tragedies of Dick’s life involved his somewhat-spontaneous marriage to a Japanese woman, with whom he had a child. According to friends, they hooked up once, at Idylwild, at the base of Suicide Rock, and she ended up pregnant, so they got married. But thanks to some combination of her culture shock and his personality, she ran away with their three-year-old daughter to Japan, calling him from the airport and telling him they were gone. She then raised their daughter to understand that her father was an American scientist who had abandoned them.

“After that his life got a little darker,” says Fidelman. “It really hurt him.”

Years later, when his daughter was in college, she found a way to contact her father, and they emailed back and forth. “It was very hopeful, very rosy, on both sides,” says Judge. “Eventually he bought her a plane ticket to come meet him and stay with him, but it did not go well. It was a combination of expectations and, from what I gathered between the lines, the fact that she wanted someone to care about her, whereas he wanted someone to know and appreciate what he’d accomplished as a scientist. So they just couldn’t understand each other. She left on bad terms and they never spoke again.”

Judge added that, if she reads this, she should reach out.

Even after his retirement in the late 2000s, Dick continued to work on emeritus status with SPAWAR (which has since rebranded as NAVWAR), haunting his desk and “bothering people,” according to Judge. But he was also at the Santee Boulders nearly every day, meeting newer boulderers, getting to know them, and eventually taking them out on bigger routes. “He took me to Tahquitz for my first multi-pitch climb,” says Judge. “We climbed Fingertrip, a four-pitch 5.7, and the next day at Suicide Rock we did Mickey Mantle (5.8) and Spatula (5.10a) and Ten Karot Gold (5.10a R two pitches).”

Judge was 21 years old at the time. Shockley was 67. “We used his old Wild Country Friends, the original versions, with the original slings,” says Judge. “He took me on my first runout slab. He caught my first lead fall. He had a really cavalier attitude toward the whole endeavor. I think he got a lot from the rush of trusting someone he shouldn’t, and he came alive with a smile when it was scary up there for me. He was behind my first real days outside, and I had so much fun out there with him. And for a few years after that, and especially after he was diagnosed with cancer, he pretty much became my best friend. I realized that I was talking to him three or four times a week, and there was no one else beside my family like that.

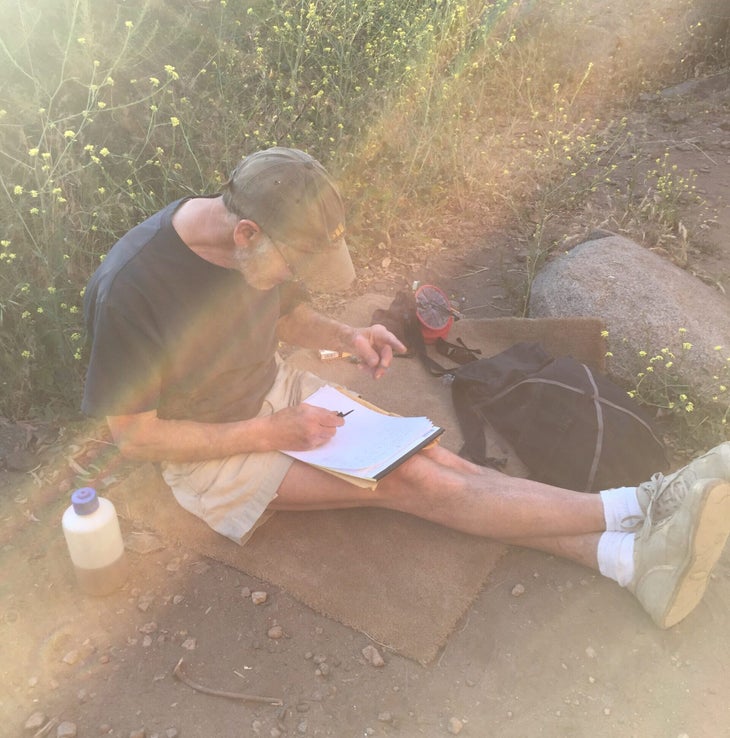

“I used to work right down the street from the Santee Boulders, so I used to try to go every afternoon. Dick would sit there on a bouldering carpet, because he was pretty anti crash pad—he had poems about it—and he would do these math problems, problems with number theory that he’d been working on for years. He’d just be out there with a pencil, paper, and cigarette, crunching numbers. Sometimes I’d barely climb. I’d sit down and we’d talk about math and poetry, neither of which are even really my things, but he’d talk about them in such interesting ways. He was always trying to teach me about physics. I have hundreds of pages of handwritten letters where he tried to explain Einstein’s Theory of Special Relativity to me. I wanted to get old climbing stories, he wanted to talk about Einstein.”

Dick continued to climb hard and tricky boulder problems, “particularly low-angle dime-edge stuff,” well into his late sixties, says Judge. But about five years before his cancer diagnosis he took a bad fall at the Santee Boulders (he’d kicked away a crash pad to show some younger climbers how to do a tricky highball he’d done hundreds of times) and got a compound fracture on his heel.

“He never really climbed again,” says Judge. “Until then he’d been jogging to work every day, so it really impacted his life. But he still went to the boulders and worked on his problems and heckled people.”

When Dick was diagnosed with bile duct cancer, he didn’t want to fight it, didn’t want to treat it. “It was a horrible time,” says Judge, who had by then relocated to LA and was communicating with Dick mostly by phone and letter. “He really just didn’t want to suffer, so he was trying to get into this California assisted suicide program, but it didn’t work out. He had one surgery for the cancer, and when that didn’t work he said he was just going to ride it out.”

Dick’s brother and sister had passed before him, so in his final months, Dick’s family and support network consisted largely of climbing friends, old and new. Mike Lechlinsky talked to him nearly every day during the final weeks of his life, as did Judge and another young climbing friend, Daniel, with whom he’d also bonded about math at the Santee Boulders.

“Dick didn’t have any family left but he was more willing than most people to have and build deep friendships,” says Judge. “He would talk your ear off; it was almost a problem sometimes; but he also asked deep questions, and he was genuinely interested in how you were thinking. He was a very willing friend.”

—Steven Potter

You can read the full tribute to Climbers We Lost in 2023 here.