Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

In the days before climbing gyms were widely accessible, the end of rock climbing season loomed dark. Climbers had limited options once the spring and fall seasons waned; you could head out to suffer in subpar conditions or stash the rope and dangle from hangboards until send temps returned.

Modern accessibility to climbing gyms has totally eliminated the “climbing season” by providing the space to continue trying hard regardless of the weather. Year-round climbing is fantastic for rapid skill development, and allows continuous training at a high intensity, but it also eliminates seasonal variation in training patterns and ensures there’s never an “off season.” Unfortunately, unlimited access to continuous training often comes at a price. Eventually, progress begins to plateau, your list of sore body parts keeps growing, and climbing becomes more monotonous than fun. Having a sustainable relationship with climbing requires intentionality in balancing climbing specific training with cross training and recovery. If you’ve been trying hard for a while, but feeling a bit stagnant, taking a season off of climbing might be just the solution for unlocking your next big send.

The problem: Climbing at the same intensity year round stunts your progress and increases risk of injury

Many climbers get hooked on the sport because initial progress happens so quickly: You spend a few days flailing up V0s, and soon you’re projecting V2s. However, initial progress slows down as the body adapts to the stimulus, and requires a stronger stimulus to continue improving. (5) Many climbers attempt to increase the stimulus by increasing training frequency and intensity—with positive results, initially—but that can lead to fatigue and overuse injury if training variation and recovery periods aren’t sufficient. (4) Overuse injuries are the most common climbing related injury and athletes who have more experience, climb more frequently and climb at a higher level are at an increased risk due to increased stress on the body. (1, 10, 11) In other words: climbing hard is hard on the body and once you’ve been climbing regularly for a while, your body needs variation in training frequency, intensity, and activity to continue progressing.

The solution: Seasonal variation in training type and intensity

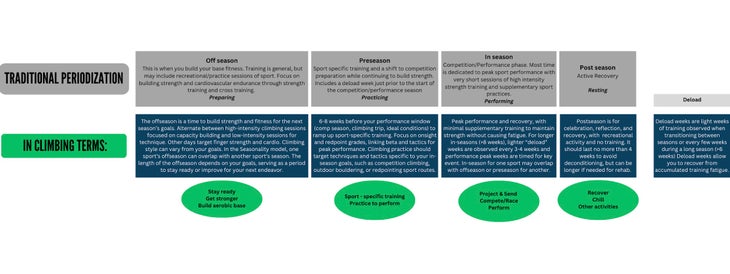

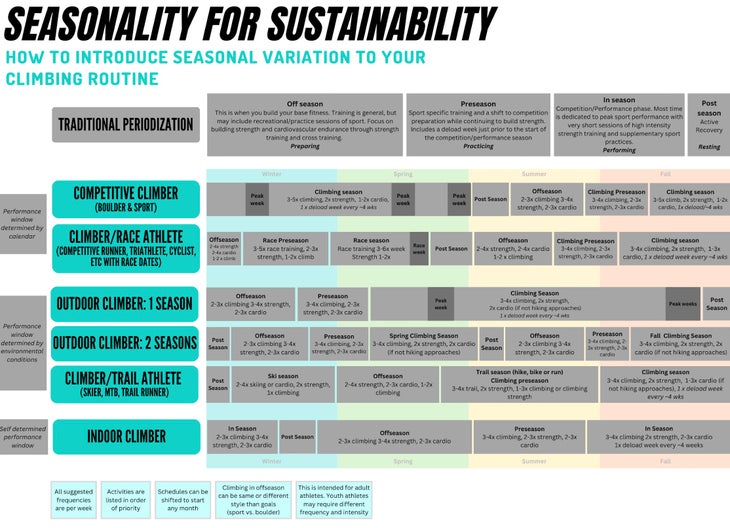

Many sports follow a training structure called periodization to build variation into a training program. Periodization is the intentional sequencing of different training phases or seasons, each designed to stimulate specific adaptations, and the program culminates in a period of peak performance (think “competition season”). Each phase alternates periods of training overload with periods of recovery to promote gains and reduce injury risks.

Periodized training works well for athletes with consistent schedules, clear goals, and a predictable timeframe for peak performance, such as a competition season. However, the structure can feel too rigid for climbers who have variation in their schedules, goals, or performance windows—outdoor climbers, multi-sport athletes, and athletes with busy schedules, for example. For this I propose a more organic training structure: Seasonality. Seasonality is structured variation in activity and intensity influenced by personal goals, life circumstances, and weather conditions. Rather than attempting to train for everything at the same time or struggling to stick to a training plan that doesn’t suit your schedule, thinking in seasons can provide perspective on the choice to modify your climbing routine or step away to focus on “off season” pursuits that serve as a building block for the next “climbing season.”

Reintroducing seasonality to a sport that is now always in season is a simple way to find the balance needed to maximize performance and longevity in the sport. This chart provides a breakdown of the focus and goals of each season.

It can feel counterintuitive to decrease climbing frequency in the “Off Season” when your goal is to improve your climbing performance. Each season provides training benefits that build on each other to improve performance. Knowing that there is another season around the corner is reassuring when it feels scary to change your routine for something you’ve dedicated so much time to. The length of a season can vary, but is a period of time that has meaning to you and your pursuits: A semester, the winter months, the youth sport climbing season, the 16 weeks leading up to a marathon, etc.

Recommendations for training

Building Seasonal Variation

To incorporate seasonal variation into your training, start by identifying your peak performance window—your “In Season.” This is the period you will be performing at your absolute best, whether that’s for a climbing trip, competition series, or ideal send temps. Once you’ve pinpointed that window, work backwards.

The six weeks or so leading up to your In Season is your “Preseason”—a phase focused on ramping up sport-specific training and sharpening your skills. Everything before that is your “Off Season,” the time to build your physical and mental base through general conditioning, strength work, or other activities. This structure—Off Season, Preseason, In Season—can be customized to fit your goals, lifestyle, and other activities. Here are a few possible options:

Respect the Off Season

The “Off Season” is often misunderstood by climbers. Many treat it like the “Post Season,” spending months doing minimal activity at low intensity. In reality, the Off Season is the time to prioritize consistent cross training to build a strong foundation for improved in-season performance. While different cross training activities vary in how they transfer to climbing, the key is choosing something you enjoy or find meaningful. Although cross training alone may not directly improve climbing ability, climbing performance depends heavily on motor and perceptual skills (9), which can be developed through many activities. Strength, endurance, problem-solving, and movement skills are all highly transferable to climbing.

- Aerobic activities (running, biking, hiking, skiing, rowing, swimming) improve cardiovascular fitness which aids rapid recovery between attempts and is linked to sport climbing ability, which has similar aerobic demands to cycling. (2,7) Cardiovascular fitness also improves stamina for long days—like tough approaches or multi-round comps.

- Anaerobic activities (strength training, martial arts, kickboxing, HIIT) build muscle and explosive power, which support climbing performance and injury prevention. Heavy load training and plyometrics support bone density and tendon health. Strength training and sports that have high demand on the upper body (ie. boxing) may have similar demands to climbing, (7) making them more transferable.

- Mobility/proprioception (yoga, Pilates, dance) improves body awareness, balance, and mobility, helping access demanding positions and enhancing movement on the wall.

- Creative activities (art, building, music) support climbing’s cognitive and creative demands, such as recalling, or solving, intricate sequences.

Cross training during the Off and Preseasons trains your body to tolerate harder climbing In Season. Find something that brings you joy and try it out for a season.

Climbing less is okay

It can be scary to climb less or step away to prioritize other activities during the Off Season. When you’ve worked hard to get to the level that you’re at, you may be anxious about losing strength and skin or “forgetting” how to climb. Trust the process—taking time during the Post Season or Off Season to recover and prioritize cross training will set you up for greater success in future seasons.

Generally, 3-4 weeks of relative rest in the Post Season is considered the ideal amount of time to recover while avoiding excessive detraining. (5) The “relative” part of “relative rest” is important; continue moving recreationally and in daily activities, but at lower intensity than during training periods. Aim to meet general exercise guidelines: two sessions of strength training for all major muscle groups, and 150-300 minutes of aerobic exercise (75-150 min if the exercise is high intensity) every week.

As another comfort to rest-adverse climbers, a recent study found that participants who trained, took 10 weeks off, and resumed training saw the same strength gains—and even greater long-term strength gains—compared to those who trained continuously. (6)

Key indicators your climbing will benefit from seasonal variation

Generally, climbers who have been climbing consistently for a year or more will benefit from seasonal variation. Reflecting on your training history can provide valuable insight for when variation in climbing routine or a deload period might help. Signs that it could be time for training or season variation include:

- Feeling stuck on projects or in strength training despite consistent effort

- Not having taken more than a few days off from climbing in months (or even years)

- Doing the same type of climbing or training program for an extended period

- Recently achieving a big goal or wrapping up a competition season

In these cases, varying climbing intensity throughout the season and integrating periods of cross training with appropriate recovery will be highly beneficial to performance and longevity in the sport.

Pay attention to your physical and mental health

Lingering injuries, chronic fatigue, frequent illness, menstrual irregularity, a loss of motivation, or climbing out of compulsion rather than enjoyment are serious signs that a break is needed. If any of these sound familiar, don’t brush them off. Take a few weeks of deloading to recover from your current fatigue, then reassess your approach, and build more intentional seasonal variation into your routine moving forward.

Special Considerations

The youth climber: Adolescents are most susceptible to climbing injuries like growth plate fractures during puberty, and especially during growth spurts. (4) Preteen and teenage climbers typically have more time and fewer life distractions that allow them to spend many hours at the gym each week, and many youth teams train year round for the 10 month competition cycle. Frequent, long sessions and climbing into fatigue put youth climbers at serious risk for overtraining and overuse injuries. (1) Ideally, serious youth climbers will practice under the guidance of a well-informed coach or parent. The climbing competition schedule provides some framework that naturally promotes seasonal variation in training, but team programming and individual athlete needs vary widely.

Youth climbers should be encouraged to notice changes in their performance and energy levels or lingering aches and pains. Climbing intensity and duration should be limited by parents and coaches when signs of injury or fatigue occur and every year should include time off from climbing. Avoiding sport specialization by participating in a variety of sports is beneficial to developing athleticism and gross motor skills (8) and reduces the risk of overuse injury and burn out. (4) Ideally, athletes will participate in a variety of sports around the year and delay specialization in climbing until high school or 14 -15 years old. (3)

The climbing professional: If climbing is part of your job (route setting, guiding, arborist, athlete, etc.), or your work is physically demanding, your livelihood depends on adequate load management and recovery. It is especially important for climbing professionals to address aches and pains quickly with a health professional. Climbing for work may also limit you from dedicating additional energy to training for your personal climbing goals. Cross training and resistance training are important for maintaining strength and endurance.

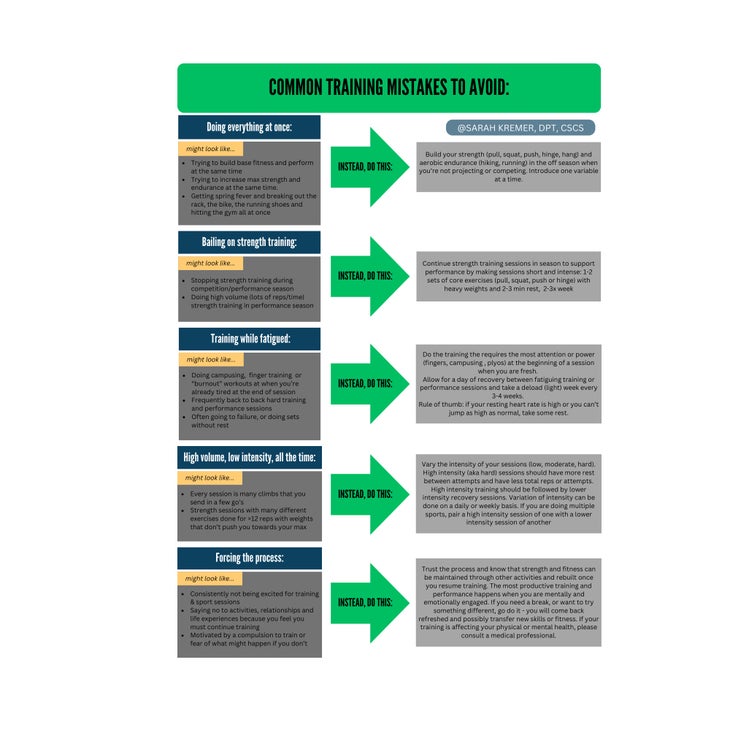

The self-coached climber: One aspect that makes the sport of climbing unique is the number of “self-coached” athletes who participate at a high level. It’s easy to make training mistakes when you don’t have a structured program or the guidance of a coach, so it is especially important to be mindful of the amount of time you dedicate to recovery and cross training. As you plan your seasons of training and performance, consider these common training errors:

See a Doctor of Physical Therapy

Please seek the guidance of a physical therapist or medical professional if you are dealing with an overuse injury, lingering pain, or symptoms of overtraining. In most cases, you can see a Doctor of Physical Therapy directly without a referral.

About the author

Sarah Kremer is a Doctor of Physical Therapy, Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist, and coach based on the New Hampshire Seacoast. She fell in love with climbing on the UNH Climbing Team and has spent many seasons bouldering and sport climbing around the country. After years as a dedicated climber, coach and routesetter, Sarah has found balance in letting the sports follow the season. Depending on the time of year, she can be found running, climbing, biking, skiing, paddling, hiking or watercoloring somewhere in New England.

About the contributors

Dr. Jared Vagy “The Climbing Doctor,” is a doctor of physical therapy and an experienced climber, has devoted his career and studies to climbing-related injury prevention, orthopedics, and movement science. He authored the Amazon best-selling book Climb Injury-Free, and is a frequent contributor to Climbing Magazine. He is also a professor at the University of Southern California, an internationally recognized lecturer, and a board-certified orthopedic clinical specialist.

To learn more about Dr. Vagy you can visit theclimbingdoctor.com or visit him on Instagram @theclimbingdoctor or YouTube youtube.com/c/TheClimbingDoctor

Kevin Cowell is a physical therapist, clinical instructor, and rock climber based out of Broomfield, CO. Kevin owns and operates The Climb Clinic (located at G1 Climbing + Fitness) where he specializes in rehab and strength training for climbers and mountain athletes. He found his passion for climbing in Colorado while attending Regis University for his Doctorate of Physical Therapy and has since become a Certified Strength & Conditioning Coach (CSCS), Board-Certified Orthopaedic Clinical Specialist (OCS), and a Fellow of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Manual Physical Therapy (FAAOMPT).

You can contact Kevin via email at kevin@theclimbclinic.com or by visiting www.theclimbclinic.com. Also, be sure to follow Kevin at @theclimbclinic on Instagram for free rehab and strength training resources.

Julien Descheneaux is a master of physical therapy who dedicates himself exclusively to rock climbing injuries, having treated over 1,200 climbers. He’s been covering Quebec competitions as a certified Sport First Responder since 2014. He is also the author of the online class “Climbing injuries at the upper quadrant” for the Quebec PT Board (OPPQ) and gives regular clinics and conferences on the subject. He founded PhysioHR in 2016, the first PT clinic inside a rock climbing gym in Canada and is currently the resident PT at Bloc Shop Chabanel.

You can contact Julien via email at julienlephysio@gmail.com or by visiting https://www.physioescalade.com/.

Todd Bushman is a doctor of physical therapy, clinical instructor, Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist (CSCS), and climber of mountain, rock, ice, and plastic. Todd is a dedicated climbing specialist based out of Bozeman, MT where he practices full time. He is actively pursuing advanced training to become a Certified Orthopedic Manual Therapist (COMT) through the North American Institute of Orthopedic Manual Therapy. Todd is also available for remote consultation regarding climbing injuries, movement analysis, and strength training.

You can contact Todd via email at todd.climbingcoach@gmail.com or visit him @try.hard.pt on Instagram.

Carly Post is a physical therapist in Los Angeles, California. She is passionate about climbing and enjoys helping people move better and optimize their ability to participate in their lives to their fullest potential. She can be reached at carlypos@usc.edu and on Instagram at @carlypost

References

- Barrile AM, Feng SY, Nesiama JA, Huang C. Injury Rates, Patterns, Mechanisms, and Risk Factors Among Competitive Youth Climbers in the United States. Wilderness & Environmental Medicine. 2022;33(1):25-32. doi:10.1016/j.wem.2021.09.005

- Callender NA, Hayes TN, Tiller NB. Cardiorespiratory demands of competitive rock climbing. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2021;46(2):161-168. doi:10.1139/apnm-2020-0566

- climbing-ltad.pdf. Accessed December 3, 2024. https://www.ualberta.ca/en/sport-system/media-library/ltad/climbing-ltad.pdf

- DiFiori JP, Benjamin HJ, Brenner JS, et al. Overuse injuries and burnout in youth sports: a position statement from the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(4):287-288. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2013-093299

- Haff G, Triplett NT, National Strength & Conditioning Association, eds. Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning. Fourth edition. Human Kinetics; 2016.

- Halonen EJ, Gabriel I, Kelahaara MM, Ahtiainen JP, Hulmi JJ. Does Taking a Break Matter—Adaptations in Muscle Strength and Size Between Continuous and Periodic Resistance Training. Scandinavian Med Sci Sports. 2024;34(10):e14739. doi:10.1111/sms.14739

- Limonta E, Brighenti A, Rampichini S, Cè E, Schena F, Esposito F. Cardiovascular and metabolic responses during indoor climbing and laboratory cycling exercise in advanced and élite climbers. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2018;118(2):371-379. doi:10.1007/s00421-017-3779-6

- Myer GD, Jayanthi N, DiFiori JP, et al. Sports Specialization, Part II. Sports Health. 2016;8(1):65-73. doi:10.1177/1941738115614811

- Orth D, Davids K, Seifert L. Coordination in Climbing: Effect of Skill, Practice and Constraints Manipulation. Sports Med. 2016;46(2):255-268. doi:10.1007/s40279-015-0417-5

- Pieber K, Angelmaier L, Csapo R, Herceg M. Acute injuries and overuse syndromes in sport climbing and bouldering in Austria: a descriptive epidemiological study. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2012;124(11-12):357-362. doi:10.1007/s00508-012-0174-5

- Woollings KY, McKay CD, Emery CA. Risk factors for injury in sport climbing and bouldering: a systematic review of the literature. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(17):1094-1099. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2014-094372

- Woollings KY, McKay CD, Kang J, Meeuwisse WH, Emery CA. Incidence, mechanism and risk factors for injury in youth rock climbers. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(1):44-50. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2014-094067